Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SA Orthopaedic Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2309-8309

versión impresa ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.10 no.2 Centurion ene. 2011

ETHICS ARTICLE

Ethics of billing - determining one's value

Robert Dunn

Prof. Consultant Spine and Orthopaedic Surgeon. Associate Professor, University of Cape Town. Head: Orthopaedic Spinal Services, Groote Schuur Hospital. Spine Deformity Service, Red Cross Children's Hospital. Private Practice: Constantiaberg Medi-Clinic Hospital

ABSTRACT

Costs of medicine and fees in private practice are topical as ever with pressure from all sides to make care affordable to all. Many see specialists as cost drivers and excessively remunerated, yet many specialists are unhappy with their earnings. Unless surgeons earn adequately, their service will reduce.

The conflicts of financial reimbursement and professionalism are discussed along with the history of billing in medicine.

Using the state salaries as a basis, equivalent private practice turnovers are calculated demonstrating the vast difference between perceived earnings based on turnover and the real earnings of the surgeon.

An individualised tariff calculation is recommended along with appropriate billing practice.

This paper is based on an ethics lectured delivered at the 2010 South African Spine Society meeting in Cape Town.

Key words: ethics, billing, salaries, reimbursement, surgeon

Medicine is a profession on which physicians rely for their livelihood and patients for their lives. If physicians do not charge for services, they cannot survive. If patients cannot afford those services, they cannot survive. No wonder many physicians have long agreed that fees are 'one of the most difficult problems ... between patient and physician.'1

Globally medical costs have increased faster than inflation and the ability of many patients'ability to pay.The rapid rise in medical costs is multifactorial. There is the increased sophistication of medicine especially with the equipment and prostheses used. Patients demand the 'best', as they see it, despite the costs. Minimum risk is demanded, increasing the costs of monitoring equipment. Intervention at all costs is expected. This is evident in the oncology field where a vast amount of money is spent to prolong life for a few months with questionable benefit to society or the individual.

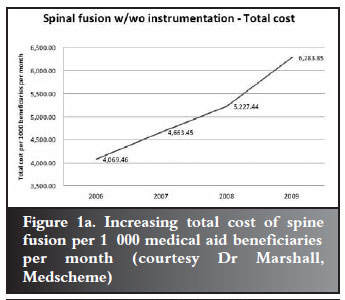

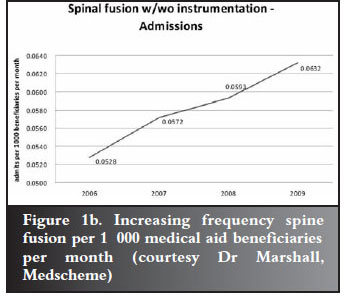

However, denying care in these circumstances is difficult for many reasons. Government promises the electorate access to care and so they expect it. In the private sector people feel they have purchased the care by belonging to medical aids and paying what they often think are exorbitant monthly premiums. Both sectors experience entitlement which drives utilisation of services. This may be further exacerbated by specialists concentrated in urban areas. Figures 1a and 1b demonstrate this increasing cost and volume for spinal fusions per beneficiaries.

The funders are faced with rapidly increasing spend due to this rising cost and volume. They cannot pass this onto the consumer as their ability to pay is limited. Private medical administrators make their money from the medical aids and thus cannot risk losing members by adjusting premiums markedly upwards despite actuarial requirements.

Their ability to manoeuvre is limited. The hospital groups are few and strong. They have the administrative muscle to negotiate with funders. Funders also realise that if their members are not accepted by a big hospital group, the medical aid product will not sell.

It appears that currently the funder's response has been to attempt to avoid increased payments to professionals - you and me. Of course this is counter-productive as, if a surgeon attempts to work at these heavily discounted rates (National Reference Price List - NRPL), then he must increase his volume to make the living he desires. As the surgeon's fee is only a small component of total intervention cost, this simply drives the costs further.

This problem is ongoing and not specific to South Africa. Two strategies have developed in this milieu. One is the surgeon who feels he cannot charge more than the NRPL rate. This is often based on the fact that he feels his patient population cannot afford more. This may be morally based, but often the surgeon feels threatened that he will lose work, especially if his area is heavily traded by NRPL-based surgeons.

The other strategy has been the surgeon who simply says, 'I am worth more', and bills at a higher rate. He may have a lower volume practice, but the turnover may in fact be more.

There has been a response to this above-NRPL billing by government and funders. Many refuse to pay the higher rate and attempt to penalise the surgeon by paying the patient directly, or excluding the surgeon from a referral group with the implementation of the designated service provider system. Government has attempted to cap these fees playing into the hands of some funders who threaten the doctor with overcharging and unprofessional conduct.

This has led to adversarial relationships between surgeons and the Department of Health as well as some funders. The SAOA (along with other groups) is currently in a legal battle with the Department of Health over its continued refusal to base reimbursement on real costs as opposed to a historical system with submedical inflationary increases. The courts recently vindicated this stance by dismissing the current NRPL tariff calculation.

This leads to many problems. Many surgeons feel under-remunerated. This may lead to questionable billing practices such as excessive coding where surgeons feel they are unable to charge above NRPL. There is temptation to look for another income stream which leads to issues of perverse incentives. Patients suffer by being left with big shortfalls on their accounts. Surgeons may even leave the profession or consider emigration to less hostile financial environments.

How do we as surgeons deal with the situation?

It is extremely difficult as we are faced with conflicting aspects. Medicine combines both elements of altruism and self-interest, with obligations to others (patients) and yourself (and family). There is a pull between professionalism and commercialism.2-4

Hall et al1 summarises the history of payment for services where centuries ago, English physicians could not legally bill for their services or sue to collect fees. Following the supposed Roman practice, patients paid 'honoraria' that were supposed to be given voluntarily.

Thomas Percival's influential 'Medical Ethics' delicately called medical payments 'pecuniary acknowledgements' and were received as a point of honour. This honorarium rule applied only to physicians and not to surgeons (as they sometimes also treated animals!). The laws of the time regarded surgery as a public calling and emphasised the profession's differences from business, in that courts could limit surgeons' fees to 'reasonable amounts'. This may well sound familiar!

The honorarium and 'public calling' principles reflected the special constraints on professionals even in commercial settings.

However this ethos did not survive the trip to the American colonies. American law freed physicians to pursue the 'making money' side, but they appeared to honour the 'making health' by departing from commercial practice in a crucial way. Doctors frequently charged according to what they thought the patient could afford.

In 1931 a physician's median fee for treating diabetes was $402 but ranged from $232 to $1052. For a major operation surgeons often charged one month of the patient's salary.

Sliding fees were the norm so they became a legal rule. Patients generally did not contract in advance; rather the patient's obligation to pay was implicit and 'reasonableness' was the standard should a disagreement reach a court.

When competition was fierce and medical services dubiously helpful, many had to drop their fees. Collectively doctors fought these market forces by promulgating recommended fee schedules. With medical education reform bottlenecking the supply of physicians combined with expanding treatments, there was increasing leeway in setting prices. There was an increasing tendency to charge 'what traffic will bear' - therefore the tendency to scale up rather than down.

Sliding fees allowed rich to subsidise poor, but charity care became increasingly institutionalised by free clinics, etc. Thus by the mid-twentieth century sliding fees tended to rise above standard. Eventually changing economic conditions weakened the sliding scale and health insurance sounded its death knell.

Insurance drove standardisation of fees. It not only prevented surcharges but also limited discounts, e.g. Medicare co-payments may not be waived as they are there as a disincentive to avoid over-utilisation. In the USA this had led to the perverse situation where insurance groups negotiate low rates and the uninsured are charged up to 2.5 times more.5

So what is the right price?

From a commercial perspective, costs incurred need to be covered and a profit generated. We can calculate our costs but what are we worth? What should we earn?

We are bright, study for many years, sacrifice and work hard. Some doctors feel they deserve the world! Many others work hard but do not earn well.

There are many difficulties when determining our worth. We do have a duty to humanity but need to earn a living. In the past only the wealthy were educated and thus in a position to study further and become physicians. Now with widespread schooling, doctors come from a far more diverse background. Many of us need to earn our living, and do not start with huge family fortunes. Costs of living are higher and our expectations are equally high. We often compare ourselves to other professions but it is difficult to compare cost structures without all the information.

As a start we can use state salaries as a base. After a period of negotiation (occupation-specific dispensation), government has come up with what it is prepared to pay doctors. Although many would not accept this as a realistic marker of a doctor's value, it provides something to work with.

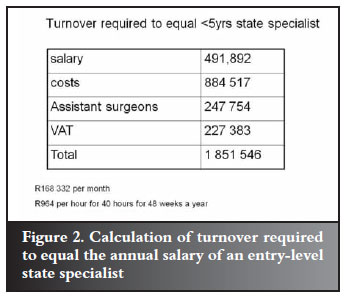

In 2010, government decided that a medical specialist with less than 5 years' experience should earn R491 892 per annum cost to company, i.e. inclusive of employee benefits such as medical aid, pension etc. This is for a 40-hour week, no overtime, with 22 working days leave a year.

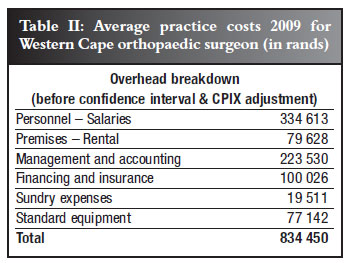

In an attempt to calculate what is required to earn the equivalent in private practice, costs need to be taken into account. Healthman6 performed a survey of private practitioners to assess the real costs encountered in practice. Based on 2009 figures they identified the average cost per annum for surgical disciplines was R801 271 with the breakdown shown in Table I. The practice cost for an average Western Cape orthopaedic surgeon was R834 450. As this is a 2009 figure, 6% inflation has been added to correct to 2010, i.e. R884 517.

But generally surgeons use assistant surgeons. For the sake of this example, I have assumed an assistant is used 90% of the time and added the 20% fee, thus R274 754. Of course, SARS wants its slice, so 14% VAT of R227 383 is added on top.

To correct for the month's leave, this turnover needs to be generated in 11 months. Thus R964 per hour needs to be generated every hour for 40 hours a week to equal the state salary of a young specialist (Figure 2). At a NRPL consultation rate of around R230, irrespective of duration, this cannot be maintained. It is even difficult to maintain with surgery at NRPL rates. A lumbar discectomy is worth about R3 700 in turnover but from start to finish with admin, ward rounds and follow-up, consumes at least 4 hours (even though 'skin to skin' is 60-90 minutes).

Even if this turnover generation is maintained, it is only R40 991 per month gross, never mind after tax and pension. This is not exactly what most surgeons had in mind when making all those sacrifices along the way. It also does not include the state pension contribution or sick leave benefits.

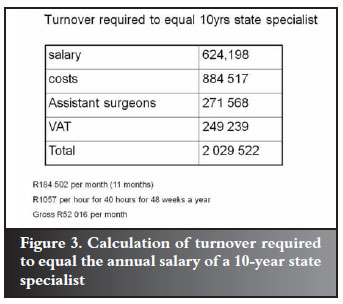

Figure 3 shows the calculation to equal a state-employed senior specialist salary where R1 057 per hour, every hour for 40 hours is required in private practice. The total turnover required is close to the average specialist earnings of R2.3 million published in a recent Financial Mail article on salaries. They derive this by dividing the total paid by medical aid to specialists by the number of specialists and give the impression that this is earnings. Of course there is a big difference in earnings and turnover as these examples illustrate.7,8

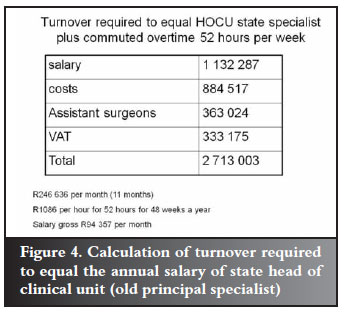

In the Healthman survey, the average duration of practice was 11 years 8 months. This would equate to the old principal specialist or now termed 'Head of clinical unit'. Based on the 2010 salary, a private practitioner would need to generate R1 244 per hour to equal this on a 40-hour week basis. However, few doctors work 40 hours and HOCU are paid a 52 week by means of an allowance. To equal this, a private practitioner would need to generate R1 086 every hour for 52 hours to equal this (Figure 4).

Healthman made a submission based on their practice cost survey and an annual salary (cost to company) of R858 600. In addition they added an amount of R161 365 as a return on investment. In addition to the surgeon being the 'labourer', he was also the owner of the business and should expect a return on this. Healthman then calculated a unit value for billing, coming to R27.25 for surgical disciplines to achieve this turnover (in excess of three times the recent NRPL rate).

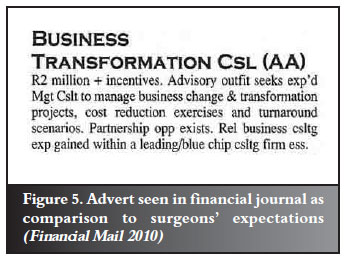

Many would argue that well-established sub-specialists should earn well in excess of this especially when compared to non-medical professionals in the financial field where annual salaries (not turnover) of R2 million are seen advertised (Figure 5). To achieve this (using the previously used calculation methodology), an hourly generation of R1 554 every hour for 52 hours a week is required.

Although as doctors we are taught not to discuss money, this is the reality. To earn what we think we are worth, these are the turnovers required. We need to be tempered by our professionalism and be compassionate to our patients, but if our practice is not financially viable, private medicine will not survive. We need to be far more transparent as regards our finances. The HPCSA is insisting on this and expects us to discuss fees with our patients pre-operatively. This is only reasonable. By including our patients in this financial discussion, our worth is highlighted. If we choose to discount, we can do so expecting gratitude and early payment.

If we can justify our costs, there can be no argument. We need not be ashamed that we cost money and even seem expensive to some, as long as we are delivering the service we promise.

As a group we must avoid funders dictating our income as their interests may not be aligned with ours. Patients need to be made financially responsible for the care rather than the illusion that the third party will pay. This will encourage them to 'buy' up rather than down in terms of medical cover. Inexpensive GAP cover (insurance for professional fee shortfall) is available and patients must be encouraged to be adequately insured.

The HPCSA publishes ethical and professional rules which are available on their website.9 They state that the practice as a health care professional is based on a relationship of mutual trust between patients and health care practitioners. The term 'profession' means 'a dedication, promise or commitment publicly made'. They emphasise that to be a good health care practitioner requires a life-long commitment to sound professional and ethical practices and an overriding dedication to the interests of one's fellow human beings and society.

In the HPCSA booklet on fees and commission the financial relationships are discussed, especially in connection to perverse incentives. In 7(3) is states that 'a practitioner shall not offer or accept any payment, benefit or material consideration (monetary or otherwise) which is calculated to induce him or her to act or not to act in a particular way not scientifically, professionally or medically indicated or to under-service, over-service or over-charge patients'. Over-charging is not defined in financial terms however.

The SAOA also publishes its standpoint on principles of medical ethics and professionalism.10 Its comment on remuneration is limited to that it should be commensurate with services delivered and that surgeons should deliver high quality, cost-effective care without discrimination. It does not indicate a level of fee that is ethically acceptable.

Thus it becomes clear that there is not one standard fair fee. Each surgeon is to be encouraged to actively determine his cost structure as a basis of fee calculation. To this he should add his expected remuneration for service adjusted by risk, experience and skill. By determining the expected number of cases to be processed, a surgeon-specific unit value can be calculated.

This may range from the NRPL basis of around R8 up and even beyond the Healthman calculation of R27 or so. There are many factors that will influence this, some surgeon-specific, including but not limited to experience, skill level and case mix, and some geographic due to cost of living. This is evident in a recent spine surgery survey where initial consultation rates ranged from R352 to R900 and a single level spine decompression from R3 330 to R17 604.11

Fees should be transparent and the patients included in the discussion. Discounts should be individualised, based on the case and patient circumstances. A consistent billing protocol should be employed to avoid accusations of account manipulation and overcharging, especially when it comes to prescribed minimum conditions.

Rather than capitulation to whatever the third party funder will pay, surgeons should employ balanced billing where the full account is rendered to the medical aid on behalf of the patient. The shortfall following payment by the medical aid is then due by the patient. This is legal and palatable to patients if they understand this beforehand.

Code use should be defensible in terms of procedures performed and consistent in use. Multiple coding (in excess of reasonable surgical execution) should be avoided as a means of increasing the account with a low unit value. This places the surgeon at risk and perpetuates an under-insured patient population. There are many funders with plans that reimburse at acceptable unit values, conceding that we are worth much more than the recently rejected NRPL value. By applying these principles we can not only avoid disciplinary action by HPCSA and other bodies, but also encourage our patients to select better plans. This will ensure our future financial viability and thus continuing patient care.

As stated right at the beginning, medical billing remains a difficult and often uncomfortable area to address. Possibly some wise words from an anonymous physician in 1882 may help:

'When in doubt what to charge, look around you [to what others charge], then upwards [to God], then make out your bill at such figures as will show clean hands and a clear conscience.'5

References

1. Hall MA, Schneider CE. The professional ethics of billing and collections. JAMA 2008;300(15):1806-808. [ Links ]

2. Kassirer JP. Commercialism and Medicine: An Overview. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 2007;16:377-86. DOI: 10.1017/S0963180107070478 [ Links ]

3. Rodwin MA. Medical commerce, physician entrepreneurialism, and conflicts of interest. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 2007;16:387-97. DOI: 10.1017/ S096318010707048X [ Links ]

4. Chee YC. No, no to the commercialisation of medicine. Singapore Med J 1999;40(12):1. [ Links ]

5. Hall MA, Schneider CE. Learning from the legal history of billing for medical fees. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23(8):1257-60. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-008-0605-1 [ Links ]

6. Venter C. Healthman Private Practice review 2008 distributed to members of SAOA May 2008 by email. [ Links ]

7. Paton C. Remuneration cold comfort. 2010 (Dec 17) 28-31. [ Links ]

8. Paton C. Earnings of a doctor - healthy pay packet. Financial Mail 2010 (Dec 17) 24. [ Links ]

9. HPCSA ethical rules & regulations. http://www.hpcsa.co.za/conduct_rules.php [ Links ]

10. Principles of Medical Ethics and Professionalism in Orthopaedic Surgery. www.saoa.org.za. [ Links ]

11. Dunn R. SASS billing/coding survey. Presented at SA Spine Society meeting May 2010, Lord Charles Cape Town. [ Links ]

Reprint requests:

Reprint requests:

Tel: 021 404-5387 Fax: 021 404-5389

email: info@spinesurgery.co.za