Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Orthopaedic Journal

On-line version ISSN 2309-8309

Print version ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.9 n.4 Centurion Jan. 2010

CLINICAL ARTICLE

Subcapital femoral neck fracture in patients with HIV and osteonecrosis of the femoral head

M TompkinsI; NC MkandawireII; J HarrisonIII

IMD, Alpert Brown Medical School/Rhode Island Hospital, Department of Orthopaedics

IIMBBS, Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital and Beit Cure International Hospital; Head: Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, University of Malawi

IIIFRCS, Medical Director, Beit Cure International Hospital; Senior Lecturer: College of Medicine, University of Malawi

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Osteonecrosis of the femoral head generally presents with collapse of the femoral head. A small subset of patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head, however, have been described in various case reports as presenting with subcapital femoral neck fracture instead.

METHODS: The three cases presented were gathered retrospectively from the National Joint Registry in Malawi.

RESULTS: We present three case reports of patients with HIV who suffered atraumatic subcapital femoral neck fractures in the setting of osteonecrosis of the femoral head.

DISCUSSION: Patients with subcapital femoral neck fractures and osteonecrosis of the femoral head in the setting of HIV represent a unique population with diagnostic and management dilemmas that require careful consideration.

Introduction

Radiographic findings in osteonecrosis of the femoral head demonstrate lucency and subchondral sclerosis early in the disease. As the disease progresses, these findings typically evolve into subchondral collapse, flattening of the femoral head and narrowing of the joint. There are case reports, however, that document subcapital femoral neck fractures as the main radiographic manifestation of osteonecrosis rather than subchondral collapse.1-7

The main causes of osteonecrosis and secondarily subcapital femoral neck fracture detailed in these previous case reports are steroid therapy and excessive alcohol consumption.1,4,6,7 Only one report describes a case of subcapital femoral neck fracture secondary to osteonecrosis in a patient with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).3 We present three case reports of patients with HIV who suffered atraumatic subcapital femoral neck fractures in the setting of osteonecrosis of the femoral head.

Methods

The three cases presented here were gathered retrospectively from the National Joint Registry in Malawi. Local ethics committee approval was obtained to review the data from the Registry and all patients gave informed consent to be part of the registry. Part of the informed consent included making the patients aware that data from their case may be used in publication. There was no external funding source for this study.

Over a ten-year period at our institution, 26 patients (44 hips) presented with osteonecrosis of the femoral head, as diagnosed on plain radiographs. Twelve of these patients with radiographic evidence of osteonecrosis were seropositive for HIV, and of these, three presented with subcapital femoral neck fractures rather than subchondral collapse of the femoral head. The changes on plain radiographs used to diagnose osteonecrosis of the femoral head included stage II and III changes such as wedge-shaped sclerosis, isolated areas of osteopaenia, and crescent sign. No other corroborating evidence of osteonecrosis, such as an MRI or pathologic analysis, was possible because of the available facilities and expense of the tests. None of the patients in this report had global osteopaenia on plain radiographs, and based on their age and other co-morbidities, there was no reason to suspect that they might have underlying osteopaenia or cervical insufficiency. All three patients were eventually treated with total hip arthroplasty, and therefore became part of the Registry.

Case series

Case 1

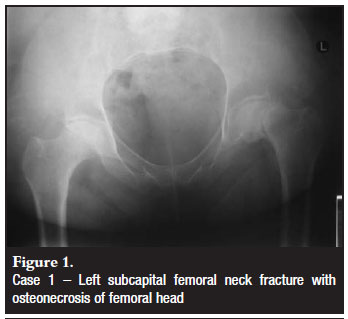

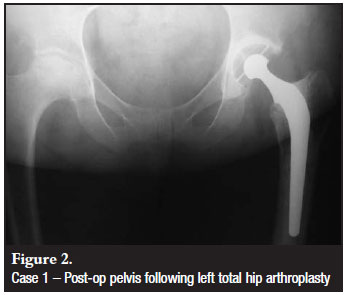

The patient is a 48-year-old HIV-positive female who presented with four months of left hip pain. She was initially treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) for osteonecrosis of the left femoral head without significant collapse. Six months later she returned with worsening left hip pain and denied any trauma to the hip. Radiographs at that time demonstrated a left subcapital femoral neck fracture, as well as osteonecrosis of the right femoral head (Figure 1). She underwent left total hip arthroplasty with a Charnley total hip three weeks later (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with HIV six years prior to the diagnosis of left femoral head osteonecrosis. She was in stage III HIV at the time of her diagnosis with a CD4 count of 94, and was started on antiretroviral therapy. Her CD4 count at the time of total hip arthroplasty was 347. Her risk factors for femoral head osteonecrosis, in addition to HIV and antiretroviral therapy, included diabetes and previous steroid therapy for asthma. She did not have any history of trauma, excessive alcohol consumption, sickle cell disease, coagulation abnormalities, irradiation, smoking, pancreatitis, deep sea diving, or drug abuse. Laboratory exams for cholesterol and triglycerides were within normal limits.

Case 2

The patient is a 54-year-old HIV-positive male who presented with nine months of right hip pain. He was initially treated with NSAIDs for osteonecrosis of the right femoral head (Figure 3). He had worsening right hip pain six months later, but denied any trauma to the hip. Radiographs at that time demonstrated a right subcapital femoral neck fracture (Figure 4). He underwent right total hip arthroplasty with a Charnley total hip shortly after his femoral neck fracture.

At the time of diagnosis of right femoral head osteonecrosis, the patient was tested for HIV and found to be positive. He was stage III HIV at the time of diagnosis, and had a CD4 count of 300. He was then started on antiretroviral therapy, and his CD4 count at the time of total hip arthroplasty was 1 410. The patient did not have any additional risk factors for femoral head osteonecrosis including trauma, excessive alcohol consumption, steroid therapy, diabetes, sickle cell disease, coagulation abnormalities, irradiation, smoking, pancreatitis, deep sea diving, or drug abuse. Laboratory exams for cholesterol and triglycerides were within normal limits.

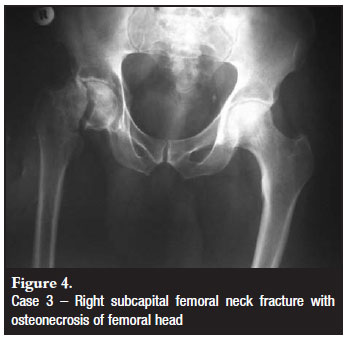

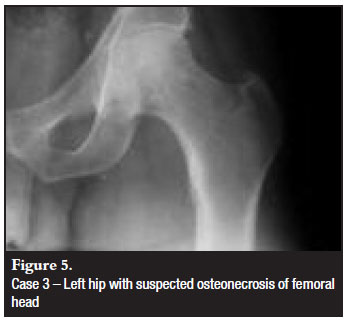

Case 3

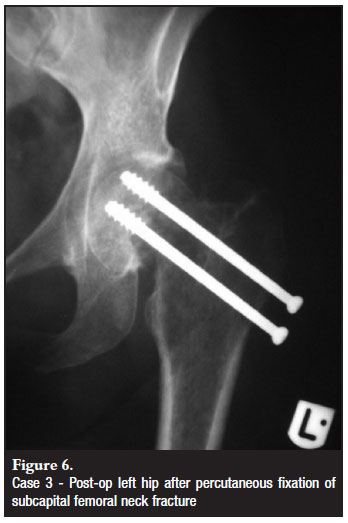

The patient is a 43-year-old HIV-positive female who presented with left hip pain. She was initially treated with NSAIDs for hip pain of unknown origin, but possible osteonecrosis of the femoral head (Figure 5). Four months later, she returned with significant discomfort in the left hip but no history of trauma. She was diagnosed with a left femoral neck fracture and likely osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Despite the suspected osteonecrosis, she underwent percutaneous pinning of the left femoral head because of her young age (Figure 6). She was made weight bearing as tolerated and returned to full ambulatory status. However, she continued to have pain in the hip and serial radiographs demonstrated progressive collapse of the head (Figure 7). Three years after her initial surgery, she underwent total hip arthroplasty.

The patient was diagnosed with HIV one year prior to diagnosis of the left femoral neck fracture. She was in stage III HIV at the time of her diagnosis with a CD4 count of 307, and was started on antiretroviral therapy. Her CD4 count at the time of total hip arthroplasty was 453. She had no additional risk factors for femoral head osteonecrosis including trauma, excessive alcohol consumption, steroid therapy, diabetes, sickle cell disease, coagulation abnormalities, irradiation, smoking, pancreatitis, deep sea diving, or drug abuse. Laboratory exams for cholesterol and triglycerides were within normal limits.

Discussion

Many theories have been advanced to describe the pathophysiology of avascular necrosis of the femoral head but so far no clear mechanism has been delineated. Regardless of the mechanism, the necrosis results in weakening of the bone in the femoral head. Usually this manifests as collapse within the necrotic area. Histopathologic studies have demonstrated, however, that the bone may also give way at the junction between necrotic bone and bone undergoing repair, usually at the base of the femoral head.8,9This results in subcapital femoral neck fracture, such as we have seen in our patients presented here.

The risk factors of femoral head osteonecrosis include trauma, excessive alcohol consumption, steroid therapy, diabetes, sickle cell disease, coagulation abnormalities, irradiation, smoking, pancreatitis, deep sea diving, drug abuse and hyperlipidaemia. Many patients who present with femoral head osteonecrosis have more than one risk factor, and the cause may actually be multifactorial. Previous reports on subcapital femoral neck fracture in the setting of femoral head osteonecrosis, however, have only described steroid therapy or excessive alcohol consumption as risk factors.1,4,6,7 The exception to this is one case report detailing a patient with HIV who developed a subcapital femoral neck fracture in the setting of femoral head osteonecrosis.3 In the cases we have presented, one patient did have other risk factors, but the final two patients had only HIV or HIV and antiretroviral therapy as possible causes. Our three additional cases demonstrate that patients with HIV and osteonecrosis of the femoral head must also be considered at risk for subcapital femoral neck fracture.

There is significant debate in the literature regarding the cause of osteonecrosis in HIV patients - whether it is secondary to the disease, treatment, or a combination of both.10-13 Some authors postulate that HIV can lead to a coagulopathy, often with antiphospholipid antibodies, which then leads to osteonecrosis.14-17 Authors also suggest an association between antiretroviral therapy, especially protease inhibitors, and osteonecrosis.10-13,18 Antiretroviral therapy can lead to hyperlipidaemia, which in turn causes fatty infiltration of the bone marrow. Fatty infiltration of the femoral head can lead to obstruction of local blood flow and osteonecrosis.

Subcapital femoral neck fracture in an osteonecrotic femoral head presents a unique treatment challenge. In a traumatic femoral neck fracture, the bone proximal to the fracture is generally not necrotic and, in a younger individual, is often amenable to some type of internal fixation maintaining the femoral head. In the case of osteonecrosis, the necrotic bone proximal to the fracture will not provide adequate implant purchase and has poor healing potential, and therefore will have a poor outcome with any type of internal fixation, as was demonstrated by the third case. Many patients with osteonecrosis are young enough, for ideally, their femoral head to be retained. Unfortunately, because of the pathology, it is generally a mistake to attempt internal fixation for a subcapital femoral neck fracture in this setting. The alternatives to internal fixation, namely hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty, should be considered in the setting of osteonecrosis.

The prevalence of femoral head osteonecrosis in HIV patients has been reported to be nearly as high as 5%.19 A high index of suspicion for femoral head osteonecrosis should therefore be maintained in HIV patients with symptoms such as groin pain or pain with ambulation. Ideally, this would be diagnosed with MRI or bone scan. Unfortunately, in many institutions with limited resources these exams are not available, so the treating physician must rely on plain radiographs and physical exam alone. Similarly, HIV, with or without the use of antiretroviral medication, should be in the differential for patients presenting with osteonecrosis of the femoral head.

Even if the patient does have other known risk factors, the treating physician should consider ordering an HIV test, such as occurred in Case 2. This is particularly important in areas of high HIV prevalence. Both of these scenarios are relevant to the treating physician, be it the primary care physician or emergency physician first seeing the patient, or the orthopaedic or general surgeon operating on the patient. Diagnosing femoral head osteonecrosis in patients with HIV becomes particularly important in terms of operative treatment when the patient presents with subcapital femoral neck fracture. These patients are likely to have a poor outcome with internal fixation of the femoral head, and the surgeon should instead consider a hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty. Where hemiarthroplasty or total hip replacement is unavailable due to cost or lack of facilities, an excision arthroplasty (Girdlestone procedure) should be considered.

Summary

Patients with subcapital femoral neck fractures in the setting of HIV and osteonecrosis of the femoral head represent a unique population with diagnostic and management dilemmas that require careful consideration. A high index of suspicion for femoral head osteonecrosis should be maintained in HIV patients with symptoms such as groin pain or pain with ambulation. Similarly, HIV, with or without the use of antiretroviral medication, should be in the differential for patients presenting with osteonecrosis of the femoral head.

References

1. Usui M, Inoue H, Yukihiro S, Abe N. Femoral neck fracture following avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Acta Med Okayama. 1996;50:111-7. [ Links ]

2. Debeyre J, Kenesi C, Boucker C. 3 cases of spontaneous cervico-capital fractures, complications of primary necrosis of the femur head. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1969;36:23-6. [ Links ]

3. Folefack DA, Arendt V, Schuman L. Fatigue fracture of the femoral neck in an HIV-positive female patient on antiretroviral therapy. Acta Orthop Belg. 2002;68:537-41. [ Links ]

4. Kim YM, Kim HJ. Pathological fracture of the femoral neck as the first manifestation of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Orthop Sci. 2000;5:605-9. [ Links ]

5. Lee JS, Suh KT. A pathological fracture of the femoral neck associated with osteonecrosis of the femoral head and a stress fracture of the contralateral femoral neck. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:807-10. [ Links ]

6. Loddenkemper K, Perka C, Burmester GR, Buttgereit F. Coincidence of asymptomatic avascular necrosis and fracture of the femoral neck: a rare combination of glucocorticoid induced side effects. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:665-6. [ Links ]

7. Min BW, Koo KH, Song HR, Cho SH, Kim SY, Kim YM, et al. Subcapital fractures associated with extensive osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;390:227-31. [ Links ]

8. Glimcher MJ, Kenzora JE. The biology of osteonecrosis of the human femoral head and its clinical implications. III. Discussion of the etiology and genesis of the pathological sequelae; commments on treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;140:273-312. [ Links ]

9. Kim YM, Lee SH, Lee FY, Koo KH, Cho KH. Morphologic and biomechanical study of avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Orthopedics. 1991;14:1111-6. [ Links ]

10. Brown P, Crane L. Avascular necrosis of bone in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: report of 6 cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1221-6. [ Links ]

11. Lima GA, Verdeal JC, Farias ML. Osteonecrosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): report of two cases and review of the literature. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2005;49:996-9. [ Links ]

12. Matos MA, Alencar RW, Matos SS. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head in HIV infected patients. Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11:31-4. [ Links ]

13. Yombi JC, Vandercam B, Wilmes D, Dubuc JE, Vincent A, Docquier PL. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head in patients with type 1 human immunodeficiency virus infection: clinical analysis and review. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:815-23. [ Links ]

14. Belmonte MA, Garcia-Portales R, Domenech I, Fernandez-Nebro A, Camps MT, De Ramon E. Avascular necrosis of bone in human immunodeficiency virus infection and antiphospholipid antibodies. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:1425-8. [ Links ]

15. Glueck CJ, Freiberg R, Tracy T, Stroop D, Wang P. Thrombophilia and hypofibrinolysis: pathophysiologies of osteonecrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;334:43-56. [ Links ]

16. Rademaker J, Dobro JS, Solomon G. Osteonecrosis and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:601-4. [ Links ]

17. Ries MD, Barcohana B, Davidson A, Jergesen HE, Paiement GD. Association between human immunodeficiency virus and osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:135-9. [ Links ]

18. Sighinolfi L, Carradori S, Ghinelli F. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head: a side effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in HIV patients? Infection. 2000;28:254-5. [ Links ]

19. Miller KD, Masur H, Jones EC, Joe GO, Rick ME, Kelly GG, et al. High prevalence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head in HIV-infected adults. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:17-25. [ Links ]

Reprint requests:

Reprint requests:

Dr M Tompkins

Alpert Brown Medical School/Rhode Island Hospital Department of Orthopaedics

593 Eddy Street Providence, RI 02903

Tel: 401-444-3581/Fax: 401-444-3609

mtompkins@lifespan.org

Local ethics committee approval was obtained to review the data from the Registry and all patients gave informed consent to be part of the registry. Part of the informed consent included making the patients aware that data from their case may be used in publication. There was no external funding source for this study.