Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SA Orthopaedic Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2309-8309

versão impressa ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.9 no.2 Centurion Jan. 2010

CLINICAL ARTICLE

MMTM AllyI; CC VisserII

IMBChB, FCP, Rheumatologist, Department of Internal Medicine, Head: Division of Rheumatology, University of Pretoria and Steve Biko Academic Hospital

IIMBChB, Rheumatologist, Department of Orthopaedics, Pain Clinic, Steve Biko Academic Hospital

ABSTRACT

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic symmetrical inflammatory arthropathy with potentially debilitating consequences in the early phases of the disease functional limitation is reversible; however, persistent inflammation results in irreversible structural changes and systemic effects accounting for considerable morbidity and premature mortality. This review, second of a two-part series, explores a paradigm shift in management of emphasising the pitfalls and benefit of early aggressive pharmacological therapies including the timely use of highly efficacious pharmacological innovations.

Side effects, including peri-operative implications of pharmacological therapy, are discussed. These therapies are cost effective if used early and judiciously, giving hope to many patients with RA.

Part II. Review of the management and surgical considerations of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis

Pharmacological management

Currently we have no cure for rheumatoid arthritis. Management consists of a combination of pain management and limitation of disease progression through the use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

A factor often contributing to a delay in starting DMARD therapy is the excellent symptomatic response to NSAIDs in early disease, especially if used in combination with corticosteroids. However, DMARDs have the greatest benefits in improving outcome and slowing radiographic progression especially when introduced early.1,2

Pain management

Standard analgesics, NSAIDs or cyclo-oxygenase 2 blockers (COXIBs) should be used at the lowest possible dose to maintain patient comfort as they are associated with significant side effects. It is important to re-emphasise that these drugs only give symptomatic relief and do not alter disease progression.

Preventative strategies should be taken when NSAIDs are used in patients with risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding, including:

• age > 65 years

• previous history of peptic ulcer disease

• concomitant steroids or anti-coagulation therapy

• the presence of comorbid conditions.

These strategies could include the co-prescription of misoprostol or proton pump inhibitors, or the use of COXIBs.3,4

Particular caution needs to be exercised in patients at risk for, or with existing renal impairment. Recently, reports of the cardiovascular risks of both the COXIBs and standard NSAIDs have been published, raising concerns about the long-term use of these drugs.5,6

Combining NSAIDs significantly increases drug toxicity with very little additional benefit in efficacy. For this reason this practice should be avoided.

Corticosteroids

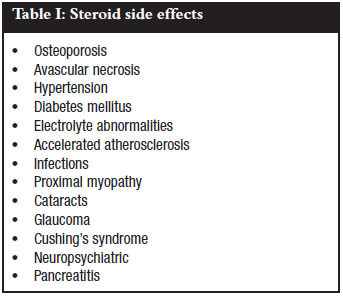

Steroids are very effective at alleviating symptoms rapidly, but cannot be used at high doses for long periods of time because of their side effects (Table I).7 They play an important role as bridging therapy to control symptoms while waiting for disease control with the DMARDs, which have delayed therapeutic effects of 6 to 12 weeks. Monotherapy with steroids has no significant effect on disease progression but a low dose of 5 mg prednisone daily is a good adjunctive therapy to DMARDs.

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

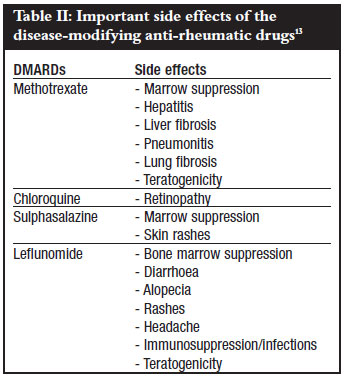

All patients with RA must be started on a DMARD as soon as possible. The best outcomes are obtained if treatment is started within four months of symptom duration, with more favourable outcomes following DMARD combination therapies.2,8 A delay in instituting DMARD therapy is associated with a poorer prognosis. All DMARDs are associated with side effects and require regular monitoring (Table II).

Methotrexate

The DMARD of choice is methotrexate given as a weekly dose, together with folic acid to decrease haematological and gastrointestinal side effects. Methotrexate is a drug that provides excellent cost-benefit and toxicity-efficacy ratios. About 50-60% of patients will have good disease control either with methotrexate monotherapy or in combination with sulphasalazine and/or chloroquine. Monitoring is required for haematologic, hepatic and pulmonary side effects. The drug should be avoided if evidence exists of viral hepatitis, HIV infection or chronic lung disease.

Methotrexate has been shown to decrease the cardiovascular mortality in patients with RA.9

Alternatives to methotrexate

If methotrexate is not tolerated or is contraindicated, sulphasalazine or chloroquine are alternative options. If response is inadequate these drugs can be used in combination with methotrexate. Chloroquine requires minimal monitoring apart from yearly ophthalmologic evaluation to detect retinal toxicity.

If the above therapies fail, leflunomide could be tried. This drug blocks pyrimidine synthesis, which is required by the rapidly dividing inflammatory cells. It is also associated with hepatic and pulmonary side effects, necessitating two-monthly blood counts and liver function testing. The drug has a long half-life and enterohepatic circulation leads to detectable drug levels for up to two years after stopping treatment.10

Both methotrexate and leflunomide are teratogenic and due precaution has to be taken when they are used in both males and fertile females. Specific guidelines need to be followed even after stopping these drugs if a pregnancy is planned.11,12

Biological DMARDs

Anti-TNF-α drugs

Approximately 10-20% of patients will have a minimal or inadequate response to the above regimens. A new class of DMARDs known as the 'biological agents' is available but is reserved for this group of refractory patients. These drugs are often used in combination with methotrexate to produce dramatic and sustained improvement in disease activity.14

Infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab are the antiTNF-α drugs available in South Africa, with golimumab awaiting registration. Their most important side effect is the predisposition to infections, especially to tuberculosis (TB). Not only are these patients more susceptible to disseminated TB, but the clinical picture and histology may be atypical, making diagnosis difficult.

Other biological agents

For patients not responding to TNF-α blockers, newer drugs have become available such as rituximab which depletes B-cells. Awaiting registration is a T-cell co-stimulation blocker, abatacept, and an IL6 inhibitor, tocilizumab.

The advent of biological disease modifiers has ushered in a period of intense excitement in the management of patients with RA. These drugs enable not only tight disease control but also remission. However it is important to note that these are very sophisticated and expensive therapies that require restricted use by rheumatologists only.

Rehabilitation modalities

Patient education is an important aspect in disease management and should focus on the disease process, drugs and their actions, side effects of treatments and facilitating acceptance of losses caused by suffering from a chronic disease. Occupational therapy and physiotherapy interventions are invaluable in maintaining optimal functionality in patients with debilitating disease.

Considerations in patients requiring surgery

As the drugs used in RA treatment all modulate the immune response, it is always a concern that they may prevent adequate wound healing and predispose to postsurgical infection.15,16 This is especially of concern in patients with:

• previous poor wound healing or same-site infection

• comorbid disease such as poorly controlled diabetes

• low total protein

• anticipated difficult surgery

Data on surgical complications in patients on DMARDs are conflicting.17

Some guidelines are suggested:

• Methotrexate: Studies vary but it seems to be associated with no significant increase in infection or delayed wound healing.

• Chloroquine and sulphasalazine: No postoperative complications of note.

• Leflunomide: Associated with increased incidence of postoperative wound healing problems. It may need to be stopped and cholestyramine washout has to be considered as it has a long half-life.

• TNF-α inhibitors: It is advisable to stop before surgery as it is associated with a significant risk of serious infection. It is recommended that these drugs be discontinued two half-lives before surgery:

Due caution has to be taken in all RA patients who are undergoing surgery as cervical spine subluxation may be present.

Conclusion

Although RA is a chronic inflammatory disorder associated with significantly increased morbidity and mortality, the outlook of this disease has changed dramatically over the last decade. With recent exciting developments in the diagnosis and treatment strategies, patients with RA now have the realistic goal of sustained remission, especially if an early and aggressive approach is taken - therefore a message of hope can now be conveyed to all patients and medical caregivers.

References

1. Breedveld FC, Kalden JR. Appropriate and effective management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:627-33. [ Links ]

2. Smolen JS, Sokka T, Pincus T, Breedveld FC. A proposed treatment algorithm for rheumatoid arthritis: aggressive therapy, Methotrexate and quantitative measures. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2003;21:Suppl 209. [ Links ]

3. Peura DA. Prevention of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug associated gastrointestinal symptoms and ulcer complications. Am J Med 2004;117(5A):63S-71S. [ Links ]

4. Naesdal J, Brown K. NSAID-associated adverse effects and acid control aids to prevent them. A review of current treatment options. Drug Safety 2006;29(2):119-32. [ Links ]

5. White WB. Cardiovascular effects of the cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Hypertension 2007;49:408-18. [ Links ]

6. Sánchez-Borges M, Capriles-Hullet A, Caballero-Fonseca F. Adverse reactions to selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors (Coxibs). American Journal of Therapeutics 2004;11:494-500. [ Links ]

7. Townsend HB, Saag KG. Glucocorticoid use in rheumatoid arthritis: Benefits, mechanisms, and risks. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2004;22 (Suppl 35):S77-S82. [ Links ]

8. Commentary. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: enhancing efficacy by combination. The Lancet 2004;363:670. [ Links ]

9. Beiss AB, Carsons SE, Anwar K, et al. Atheroprotective effects of methotrexate on reverse cholesterol transport proteins and foam cell transformation in human thp-1 monocyte/macrophages. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2008;58(12):3675-83. [ Links ]

10. Jakez-Ocampo J, Richaud-Patin Y, Simón JA, Llorente L. Weekly dose of Ieflunomide for the treatment of refractory rheumatoid artritis: an open pilot comparative study. Joint Bone Spine 2002;69:307-11. [ Links ]

11. Brent RL. Teratogen update: Reproductive risks of leflunomide (AravaTM); A pyrimidine synthesis inhibitor: counseling women taking leflunomide before or during pregnancy and men taking leflunomide who are contemplating fathering a child. Teratology 2001;63:106-12. [ Links ]

12. Lockshin MD. Treating rheumatic diseases in pregnancy: dos and don'ts. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:iii58-iii60. [ Links ]

13. Nurmohamed MT, Dijkmans BAC. Efficacy, tolerability and cost effectiveness of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs 2005;65(5):661-94. [ Links ]

14. Weaver AL. The impact of new biologicals in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol 2004;43 (Suppl 3):iii17-iii23. [ Links ]

15. Bibbo C. Wound healing complications and infection following surgery for rheumatoid arthritis. Foot Ankle Clin N Am 2007;12:509-24. [ Links ]

16. Rosandich PA, Kelly JT III, Conn DL. Perioperative management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biologic response modifiers. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004;16:192-8. [ Links ]

17. Editorial. Elective Orthopedic Surgery and Perioperative DMARD Management: Many Questions, Fewer Answers, and Some Opinions. The Journal of Rheumatol 2007, p653. [ Links ]

Reprint requests:

Reprint requests:

Prof MMTM Ally

University of Pretoria & Pretoria Academic Hospital Faculty of Health Sciences School of Medicine Department of Internal Medicine Head: Division of Rheumatology

PO Box 667 Pretoria, South Africa 0001

Tel: 27 (0)12 354-2112 Fax: 27 (0)12 354-4168

Email: tar@up.ac.za

No benefits of any form have been received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. The content of this article is the sole work of the authors.