Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SA Orthopaedic Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2309-8309

versão impressa ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.9 no.1 Centurion Jan. 2010

CLINICAL ARTICLE

Mortality in elderly patients with intertrochanteric fractures: three years' experience

RS Ngobeni

MBBCH(Medunsa), FCS(SA)Ortho, MMed(Orth Surg)UP. Consultant Kalafong / Steve Biko Academic Hospital, Orthopaedic Department, University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

AIM: To review the mortality rate of patients admitted with intertrochanteric fractures within a period of three years. Intertrochanteric fractures are common in elderly patients and result in a high morbidity and mortality rate. This article retrospectively reviewed 57 patients (65 years of age and older) admitted with intertrochanteric fractures. Descriptive statistics using the frequency / proportion method was used to interpret the results. The mortality rate in hospital was 14%, in the first year 32%, in the second year 39% and insignificant in the third year.

Introduction

Intertrochanteric fractures are common fractures in patients with osteoporosis and the morbidity and mortality rate is high. In-hospital mortality of 6.3% and 30.8% in one year have been reported,1 with men's mortality rate double that of women's.1-8 Colles fractures were found to carry a higher risk of hip fractures in males compared to spine fractures in females.9 One in 15 elderly patients admitted with hip fractures will die in hospital; out of those who survive, a third will die within the first year.1 Determinants of mortality were primarily old age, males, previous fragility fractures, and comorbidities.1,10 Three or more comorbidities are the strongest risk factors for mortality with chest infections and heart failure leading.3,11,12 There is prolonged risk of mortality in younger patients around 45 years with same pattern of fracture.13

There is substantial relative increase in mortality in patients without comorbidity both soon after the fracture and in the long term.14 In the United States, mortality rates are higher in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patients compared to the general population; however, it was found that comparing patients who were cared for at VHA to those in the Medicare Advantage Program (MAP), patients cared for at VHA had a lower mortality rate.15 The FRAMO index (fracture and mortality index) was developed and validated by Albertsson and colleagues in Sweden for Swedish women to predict fracture and mortality. Their conclusion was that the risk for fracture and mortality is increased compared to the general population in the presence of the following factors: age >80 years, weight >60 kg, previous fragility fracture, and the need to use arms to rise from sitting position.16 Poor mental state was found to increase the chances of mortality and institutionalisation.2,17 The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification of 3 or 4 has a significant excess mortality following hip fractures that persists up to 2 years after injury although this was not applicable to elderly patients over 85 years of age.18

Delaying surgery by four days or less did not have an effect on mortality rate, but a delay of more than four days increased the mortality rate.8,12,19

Patients who were previously admitted in hospital for other conditions had higher mortality rates compared to those without any previous admissions.20 Blood transfusion was not found to contribute to mortality or infection in patients with hip fractures. The old adage of prevention is better than cure holds in reducing the mortality of patients with hip fractures - prevent them from getting the fracture.21 Identifying the risk for hip fractures is therefore of utmost importance, for example, men with Colles fractures and females with spine fractures are at high risk.

A retrospective study done in Italy by Franzo and colleagues found that the in-hospital mortality rate was 5.4%; at 6 months it was 20%; and at one year it was up to 25.3%, with age, male gender, and comorbid disease being the most significant contributing factors.19

Materials and methods

Between January 2006 and May 2008 we treated 57 patients with intertrochanteric fractures. We could not follow up three patients (5.2%) due to lost patient records.

Our hospital is a secondary institution affiliated to a tertiary hospital. Our population group consists of patients referred from primary hospitals. All patients admitted with intertrochanteric fractures were included in the study. Interviews were done and a special form that was designed for this purpose had to be completed (see Table I below).

All the data was filled in accurately and followed up with documentation of any changes after admission and discharge (Table II). Short-term follow-up was done telephonically by the author to ascertain how the patients were doing; the date of the call and the patients' reportbacks were also documented. Descriptive statistics using the frequency/proportion method was used to analyse the results.

All patients were assessed medically and optimised pre-operatively according to their premorbid condition. Their treatment was, however, not delayed because of workup. Dehydration was a common problem among these patients and rehydration was done carefully so as not to over-hydrate them. The majority of patients were admitted to high care in order to optimise them pre-operatively. A physician and an anaesthetic consultant were involved pre-operatively for all patients in order to avoid late cancellations and to make sure that patients were able to have anaesthesia and survive surgery. The majority of patients were admitted postoperatively for high care overnight observation. Chronic medication was continued peri-operatively and altered by physicians if deemed necessary. Patients were discharged when their physical condition was stable.

Results

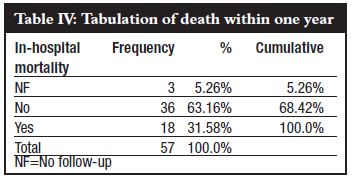

In-hospital mortality was 14%, patient mortality rate within 1 year was 32%.There was a big difference in mortality once patients were discharged, increasing from 14% to 32%. Mortality within 2 years was 39%, which showed a small difference between the first and second year. The third year was almost insignificant (Tables III and IV).

Discussion

The majority of patients admitted with intertrochanteric fractures were females, namely 73%. Of these 52% were white and 21% were black. White and black males constituted 15% and 10% of the total, respectively. Hence, there were more females than males and more whites than blacks. Overall, white females were in the majority (Graph 1). Robbins et al22 has proven that the risk for mortality is highest in the first 6 months with males carrying death risk approximated to those without hip fractures.14,22

Our facts conclusively show that females are still in the majority, namely 73%. Whether patients came from old age homes or from home did not make any difference to mortality or morbidity (Graph 2). There was no difference in mortality whether the patient was operated in < 24 hrs or >72 hrs, as long as patients were operated within a week (Graph 3).

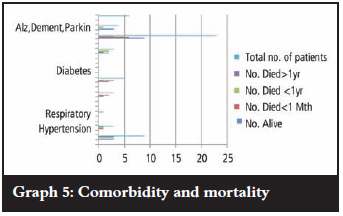

Comorbid diseases do contribute to mortality ratios but our study did not include this facet. A total of 31.58% of the patients died within 1 year and 50% of them had at least one comorbid disease (Graphs 4 and 5).

In-hospital mortality was 14% which differed from previous reports, for example Edward Hannan and colleagues reported only 1.6% and A Franzo and colleagues reported 5.4%.19,23 Our mortality rate of 31.58% in 1 year corresponds closely with the previous 25.8% reported by Franzo et al, and P Johnston and colleagues who reported 28.2%.19,24 Mortality in the second year was 39%, a small difference between first and second year; the third year difference was insignificant.

Recommendations

Further studies on the effects of comorbid diseases on mortality in elderly patients with intertrochanteric fractures needs to be done.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr S Motsitsi who provided his expert opinion and supervised the study; Dr Samuel Manda who helped with the statistical analysis; Mrs Kedibone Manchidi for her help with information and technology. We acknowledge Prof RP Gräbe for the final arrangement of the article and correction of grammar.

References

1. Jiang HX, Manjumdar S, Dick DA, Moreau M, Raso J, Otto DD, Johnston DWC. Development and initial validation of a risk score for predicting in-hospital and 1-year mortality in patients with hip fractures. J Bone Miner Res 2005 Mar;20(3):494-500. [ Links ]

2. Cree M, Soskolne CL, Belseck E, Hornig J, McElhaney JE, Brant R, Suarez-Almazor M. Mortality and institutionalization following hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000 Mar;48(3):283-8. [ Links ]

3. Trombetti A, Herrmann F, Hoffmeyer P, Schurch MA, Bonjour JP, Rizzoli R. Survival and potential years of life lost after hip fracture in men and age-matched women. Osteoporos Int 2002 Sep;13(9):731-7. [ Links ]

4. Wehren LE, Hawkes WG, Orwig DL, Hebel JR, Zimmerman SI, Magaziner J. Gender differences in mortality after hip fracture: The role of infection. J Bone Miner Res 2003 Dec;18(12):2231-7. [ Links ]

5. Fransen M, Woodward M, Norton R, Robinson E, Butler M, Campbell J. Excess mortality or institutionalization after hip fracture: Men are at greater risk than women. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002 Apr;50(4):685-90. [ Links ]

6. Pande I, Scott DL, O'Neill TW, Pritchard C, Woolf AD, Davis MJ. Quality of life, morbidity, and mortality after low trauma hip fracture in men. Ann Rheum Dis 2006 Jan;65(1):87-92Epub 2005 Aug 3. [ Links ]

7. Endo Y, Aharonoff GB, Zuckerman JD, Egol KA, Koval KJ. Gender differences in patients with hip fracture: A greater risk of mortality and morbidity in men. J of Orthop Surg 2005 Jan;19 (1):29-35. [ Links ]

8. Majumdar SR, Beaupre LA, Johnson WC, Dick DA, Cinats JG, Jiang HX. Lack of association between mortality and timing of surgical fixation in elderly patients with hip fracture. Med Care 2006 Jun;44(6):552-9. [ Links ]

9. Haentjens P, Johnell O, Kanis JA, Bouillon R, Cooper C, Lamraski G, Vanderschueren D, Kaufman J-M, Boonen S. Evidence from data searches and life-table analyses for gender-related differences in absolute risk fracture after Colles or spine fractures. Bone Miner Res. 2004 Dec;19(12):1933-44. [ Links ]

10. Bass E, Campbell RR, Werner DC, Nelson A, Bulat T. Inpatient mortality of hip fracture in patients in the Veterans Health Administration. Rehab Nurs 2004 NovDec;29(6):215-20. [ Links ]

11. Roche JJ, Wenn RT, Sahota O, Moran CG. Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people. BMJ 2005 Dec 10;331(7529):Epub 2005 Nov 18. [ Links ]

12. Moran CG, Wenn RT, Sikand M, Taylor A. Early mortality after hip fracture: Is delay before surgery important. Bone Joint Surg Am 2005 Mar;87(3):483-9. [ Links ]

13. Shortt N, Robinson M. Mortality after low-energy fractures in patients aged at least 45 years old. J Orthop Trauma 2005 Jul;19(16):396-400. [ Links ]

14. Farahmand BY, Michaelsson K, Ahlbom A, Ljunghall S, Baron JA. Survival after hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 2005 Dec16(12):1583-90Epub 2005 Oct 11. [ Links ]

15. Selim AJ, Kaziz LE, Rogers W, Qian S, Rothendler JA, Lee A, Ren XS, Haffer SC, Mardon R, Spiro DMA, Selim BJ, Fincke BG. Risk-adjusted mortality as an indicator of outcomes. Med Care 2006 Apr;44(4):359-65. [ Links ]

16. Albertsson DM, Mellstrom D, Petersson C, Eggertsen R. Validation of a 4-item score predicting hip fracture and mortality risk among elderly women. Ann Fam Med 2007 JanFeb;5(1):48-56. [ Links ]

17. Muraki S, Yamamoto S, Ishibashi H, Nakamura K. Factors associated with mortality following hip fracture in Japan. J Bone Miner Metab 2006;24(2):100-4. [ Links ]

18. Richmond J, Aharonnoff GB, Zuckerman JD, Koval KJ. Mortality risk after hip fracture. J Orthop Trauma 2003 Jan;17(1):53-6. [ Links ]

19. Franz A, Francescutti C, Simon G. Risk factors correlated with post-operative mortality for hip fracture surgery in the elderly. Euro J Epidermiol 2005;20(12):985-91. [ Links ]

20. Barrett JA, baron JA, Beach ML. Mortality and pulmonary embolism after fracture in the elderly. Osteoporos Int 2003 Nov;14(11):889-94.Epub 2003 Aug 26. [ Links ]

21. Empana J-P, Molina P, Breart G. Effect of fracture on mortality in elderly women. Am Geriatr Soc 2004 May;52(5):685-90. [ Links ]

22. Robbins JA, Biggs ML, Cauley J. Adjusted mortality after hip fracture: From cardiovascular health study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006 Dec;54(12):1885-91. [ Links ]

23. Hannan EL, Magaziner J, Wang JJ, Eastwood EA, Silberzweig SB. Mortality and locomotion 6 months after hospitalization for hip fracture. JAMA 2001 Jun 6;285(21):2736-42. [ Links ]

24. Johnson P, Wynn-Jones H, Chakravarty D, Boyle A, Parker MJ. Is perioperative blood transfusion a risk factor for mortality or infection after hip fracture? Orthop Trauma 2006 Nov-Dec;20(10):675-9. [ Links ]

Reprint requests:

Reprint requests:

Dr R S Ngobeni

PO Box 374 0050 Wapadrand

Tel: (012) 354-5032 Fax: (012) 354-2821

Email: Shadi.Ngobeni@up.ac.za

The content of this article is the sole work of the author. No benefits of any form have been derived from any commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.