Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Southern African Journal of Critical Care (Online)

On-line version ISSN 2078-676X

Print version ISSN 1562-8264

South. Afr. j. crit. care (Online) vol.39 n.3 Pretoria Nov. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJCC.2023.v39i3.1092

RESEARCH

Patient perceptions of ICU physiotherapy: 'Your body needs to go somewhere to be recharged ... '

F KarachiI; M B van NesII; R GosselinkIII; S HanekomIV

IPhD; Physiotherapy Department, Faculty of Community and Health Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa

IIMSc; Physiotherapy Department, Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Tygerberg, South Africa

IIIPhD; Respiratory Rehabilitation, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, KU Leuven, Belgium; and Department of Physiotherapy, Stellenbosch University, Tygerberg, South Africa

IVPhD; Physiotherapy Department, Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Tygerberg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Patient satisfaction is an essential concept to consider for the improvement of quality care in healthcare centres and hospitals and has been linked to increased patient compliance with treatment plans, better patient safety and improved clinical outcomes.

OBJECTIVE. As part of a before-and-after clinical trial aimed to investigate the implementation of an evidence-based and -validated physiotherapy protocol within a surgical intensive care unit (ICU), we decided to include the patient perception of physiotherapy received in the intervention unit.

METHOD. A nested, exploratory, descriptive, qualitative study design was adopted. Purposively selected adult patients discharged from ICU during the implementation phase of the trial were interviewed.

RESULTS. Eighteen patients (10 male) with a median age of 44 years and median ICU length of stay (LOS) of six days were included. Three themes and nine categories emerged: (i) linking therapy to clinical outcome (patient expectations and understanding; physiotherapy activities and the implication of mobilisation; physiotherapy benefits and progression); (ii) the importance of developing a trusting relationship (physiotherapy value; safety; continuity of care); and (iii) communication (satisfaction; interactions and patient perception and experience of physiotherapy).

CONCLUSION. While confirming barriers to early mobility, patients perceived participation in mobility activities as a marked jolt in their journey to recovery following a critical incident. Effective communication and preservation of trust between physiotherapist and patient are essential for understanding expectations and can facilitate improved outcomes. Clinicians can use the information when managing critically ill patients. Including patient-reported outcomes to measure physiotherapy interventions used in the ICU is feasible and can inform the development of such outcomes.

Keywords: Patient satisfaction, perception, intensive care, ICU, physiotherapy, South Africa.

Patient satisfaction is an essential concept to consider for the improvement of quality care[1,2] in healthcare centres and hospitals[2,3] and has been linked to increased patient compliance with treatment plans, better patient safety and improved clinical outcomes.[4,5] Furthermore, patient preferences, opinions and perceptions are fundamental to evidence-based practice (EBP).[6,7] Providing individualised patient care is based on integrating current best knowledge with patient preferences.[6,7] There is much that can be learnt from knowing what patients expect, find helpful during their recovery and consider valuable.[8] Dinglas et al.[9] argued for the importance of moving beyond isolated therapeutic effectiveness studies focusing on survival, to focusing on optimising patient-centred clinical service provided in the ICU.[9]

The intensive care unit (ICU) environment has been described as a stressful and overwhelming setting for patients[10] and their families. According to Cutler et al.,[10]a critical illness and consequent admission into an ICU is a substantial event in a patient's life.[10] Despite patient satisfaction becoming increasingly important for both patients[11] and healthcare institutions,[3] it is rarely measured within the critical care setting. While most researchers have engaged with patients after hospital discharge,[12-14] changes in clinical practice including daily interruption of sedation and prioritising early mobilisation,[15-18] may afford hospitalised patients with a clearer recall regarding their ICU experience.

Physiotherapists form an integral part of the multidisciplinary team involved in the management of ICU patients.[19] Physiotherapy care in the ICU has been linked to early independence at hospital discharge,[20] improved functional outcome and reduction in ICU and hospital length of stay,[21] as well as a decrease in the incidence of ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW), and an increased number of ventilator-free days.[22,23] The variety of outcomes which have been reported for physiotherapy intervention in ICU are in part related to the variation in physiotherapy practice.[24] It has been argued that it is the obligation of the physiotherapy profession not only to find methods to measure the value of the physiotherapy service in the ICU environment, but also to describe the quality of this service.[25] Stiller and Wiles[13] argued for the inclusion of patient satisfaction and perception of physiotherapy care received in ICU as a way to improve the quality of care received.[13] The importance of exploring patient perception and satisfaction regarding the care received in understanding and improving the quality of care received, is also recognised by other stakeholders in the ICU. [26,27]

As part of a before-and-after clinical trial aimed to investigate the implementation of an evidence-based and -validated physiotherapy protocol within a surgical ICU, we decided to include the patient perception of the physiotherapy received in the intervention unit. The physiotherapy protocol consisted of five algorithms.[28,29] These were developed to aid physiotherapists in making 'evidence-based clinical decisions'[29] involving both rehabilitation strategies (including early physiotherapy mobilisation) and respiratory management when treating ICU patients.[30,31] The use of evidence-based treatments and protocols may contribute to improving ICU care quality because they would be 'consistent with current professional knowledge'[29] for which patient perception may provide valuable information. The aim of this article is therefore to describe patient perceptions and satisfaction regarding the physiotherapy services and care received during their stay in a surgical ICU.

Method

Study design

A nested exploratory, descriptive, qualitative study design using an interpretive research paradigm and phenomenological approach was used.[32]

Setting

The study was held in a level 1,[33] 14-bed surgical ICU at a tertiary institution in the Western Cape province of South Africa. The physiotherapy responsibility for this unit is rotated every three months, and one physiotherapist is responsible for the unit at a time. The unit physiotherapist is not exclusively allocated because they also cover ward duties. After-hours service is provided by all therapists on a rotational basis. In addition, two Western Cape universities make use of this unit as an academic platform for clinical rotations of final-year physiotherapy students.

Participants

All adult patients discharged from the experimental surgical ICU during the implementation phase of the before-and-after clinical trial were eligible for inclusion in the study. Maximum variation purposeful sampling was used. The following criteria were used to purposefully select participants: age, home language, education level, employment status, severity of illness level (APACHE II), admission diagnosis (elective/emergency surgery or trauma), ICU length of stay and mechanical ventilation. Patients were excluded from the study if they were: (i) <18 years old; (ii) unable to communicate in English, Xhosa or Afrikaans; (iii) unco-operative; (iv) had no memory of the ICU or physiotherapy; or (v) presented with a reduced level of consciousness[19] determined and aided by the use of the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and reduced co-operation and cognitive impairments as assessed by the adequacy score (SQ5).[15,19,34] The primary investigator (PI) visited the ICU daily to compile lists of patients discharged from the unit, followed them up in the wards and assessed them within 3 - 5 days of ICU discharge for inclusion into the study. Patients available for inclusion provided informed written consent, after which an interview date and time was arranged with the patient within a 3 - 5-day period of ICU discharge.

Data collection instrument

A discussion schedule including semi-structured questions was developed by the PI (MvN) based on data from a scoping review[35] on how patient perception and satisfaction with critical care was measured. The questions in the discussion schedule explored the patients' experiences and perceptions of the physiotherapy care received in the ICU. In addition, patients' understanding of the role of physiotherapy and their understanding of the satisfaction with physiotherapy care were also explored. The discussion schedule was piloted prior to use to ensure saliency.

Data collection

The PI (MvN) conducted individual semi-structured interviews of varying length (25 - 60 minutes) using the discussion schedule. Interview length depended largely on the quality of the interview and the patient's ability to participate. The PI (MvN) was an independent physiotherapist not affiliated to the physiotherapy department of the selected institution nor involved in any of the patient treatments nor related to any patient, thus limiting bias. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim by independent professionals. A Xhosa translator was present for four of the interviews. Throughout the data collection process, the PI (MvN) in conjunction with two of the co-authors confirmed and summarised the data obtained during interviews to verify the PI's understanding. The PI (MvN) kept a field journal during the data collection process for reflection, documentation of research decisions and bias identification.

Data capturing and analysis

Quantitative data collected regarding patient characteristics were captured and analysed in Excel using descriptive statistics and presented as frequencies. Interpretive phenomenological analysis was completed by the PI after the transcripts were cleared and checked against the audiotapes for accuracy. All non-English quotes were translated into English. Data were analysed inductively by the PI (MvN) in collaboration with two of the co-authors (FK & SH) according to interpretive content analysis principles using a systematic process to summarise and categorise the data and then generate the subcategories, categories and themes.[36]

Quality criteria

Trustworthiness in this study was achieved by dense description of the methods used, checking the audiotaped data with those of the originally transcribed interviews and availability of the latter for audit, peer review of the transcripts and peer examination of the findings. Multiple steps were employed to ensure credibility of the data collected and the study process. In the first week of interviews, an observer was present in addition to the audiotape recorder. This facilitated feedback from the observer regarding the interview technique and quality, allowing further reflection and development for the interviews that followed, as well as growing confidence in the quality of the data collected. Furthermore, trustworthiness was ensured through a dense description of the analysis process and member checking, whereby all patients were contacted telephonically and invited to participate in the member-checking contact session to ensure truth-value (credibility) of the data collected. Fourteen patients (78%) were willing to participate in member checking, of which six were completed telephonically. The audiotaped interviews, the transcriptions and available observer notes as well as the PI's field journal assisted with reflection on the study process and facilitated the recognition of bias.

Ethical considerations

The project was registered with the institutional review board (Ethics Approval Number S15/04/094). Institutional approval to conduct the research was also given. All aspects pertaining to ethical conduct during the study were adhered to. Participation was voluntary and withdrawal was without consequence. Written informed consent was obtained before data collection and anonymity and confidentiality were maintained through the use of alphabetical coding. All data were stored on a password-protected computer to ensure the PI had exclusive access.

Results

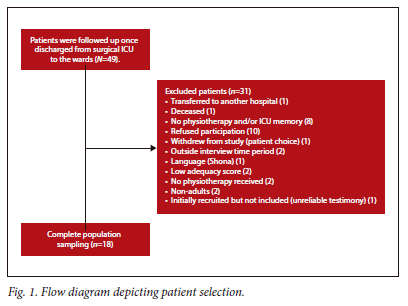

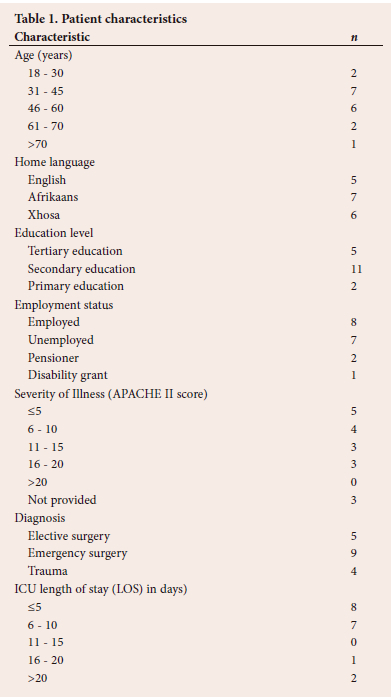

Forty-nine patients were screened for eligibility (Fig. 1). Eighteen patients were included in the study, of whom 10 were male (Table 1). The median age of the patients was 44 years, with the majority being between 30 and 60 years of age. The median ICU LOS was six days, and nine (50%) and four (22%) patients were admitted for emergency surgery and trauma, respectively (Table 1). Neither ventilator days nor frequency of mobilisation were documented.

Patients were followed up once discharged from surgical ICU to the wards (N=49).

Themes

Nine categories emerged from the data, which were summarised into three themes, namely linking therapy to clinical outcome, communication and personal relationship, and are supported by verbatim quotes from the transcribed data. The verbatim quotes are labelled using a unique participant code and are numbered consecutively, starting from one across the categories per theme.

Theme 1. Linking therapy to clinical outcome Category 1: Expectations and understanding

There was widespread diversity in patients' expectations and understanding of physiotherapy in the ICU. Physiotherapy was reportedly understood to be more for musculoskeletal injuries, gait re-education, returning to previous functional levels, and not necessarily for treatment of the lungs (Table 2, quotes 1, 2). Patients who had not experienced physiotherapy prior to their ICU admission did not know what to expect in the session, and thus their first experience of physiotherapy was described as strange and even shocking. Expectations of physiotherapy treatment was further influenced by the patient's condition and expectations of the ICU environment (Table 2, quote 3) as well as the patient's understanding and communication. Both communication and understanding acted as bridging factors to link the patient's expectations with the comprehension of physiotherapy (Table 2, quote 4). One patient, a healthcare worker, reported physiotherapy was for everybody, regardless of having different injuries in the ICU and that what they saw the physiotherapist do in the ICU would definitely affect how they did their work, being a healthcare worker (Table 2, quote 5).

Category 2: Physiotherapy activities and implications of mobilisation

Patients described multiple activities completed during physiotherapy in the ICU. Activities included chest physiotherapy, breathing exercises, limb movement and activity as well as mobilisation. Most patients also described using a 'PEP bottle' and breathing exercises that some felt assisted their breathing and rib pain (Table 2, quotes 6 - 8). Those patients who mobilised did so in bed, relocated to the chair or progressed into standing or walking in the ICU, largely with the assistance of physiotherapists. Patients described mobilisation as a difficult component of the care, mainly because of pain, tiredness and dizziness (Table 2, quotes 9, 10). However, patients found mobilisation to be a positive experience and the beginning of their recovery (Table 2, quotes 11 - 14). The effects of medication affected patients' memories and their postoperative state of mind and thus their co-operation with physiotherapy (Table 2, quotes 15, 16). Specifically, during mobilisation, preparation of the area and the physiotherapists carrying lines and drips were facilitators of physiotherapy (Table 2, quotes 17, 18).

Category 3: Benefits and progression

The general experience among patients was that participation in physiotherapy was beneficial, which they verified through physical improvements and progression in their abilities. Among the improvements were 'feeling stronger and better', particularly regarding mobilisation, and returning to 'normal', as well as improved coughing ability and decreased pain. Patients reported that physiotherapists 'built them up' and encouraged them. One patient described a mind shift that occurred once she had mobilised out of the bed. She described it as being able to see what she was capable of and what the physiotherapist had been explaining to her (Table 2, quotes 19 - 21).

Theme 2. Development of a relationship

Category 4: Physiotherapy value

Patients experienced value in physiotherapy while in the ICU, reporting the same goal of returning them home (Table 3, quote 1). Physiotherapy was described as a precious and much-needed service, without which patients felt they might not have survived or recovered as quickly (Table 3, quotes 2, 3). Patients perceived physiotherapy in the ICU as worthwhile, making them 'feel better and stronger'. It was a service that patients felt should 'never' be removed from the hospital, as physiotherapists have a role to play in helping patients (Table 3, quotes 4, 5).

Category 5: Safety

Falling was a repeated concern and patients specifically reported not falling owing to assistance and support received by physiotherapists, thus feeling safe during sessions. Providing calm and comfortable circumstances is essential for making patients feel safe during physiotherapy (Table 3, quotes 6 - 8). An overall sense of safety during physiotherapy was perceived. The physiotherapists' professionalism, reassurance and communication including aiding patients in knowing what to expect during physiotherapy, made patients feel comfortable and safe, thus building a trusting relationship with the physiotherapists (Table 3, quotes 6 - 8). One patient described the importance of ensuring a feeling of safety, explaining that fear and pain were directly linked. He further said that pain would be less exaggerated or reduced, to a certain extent, if fear were managed and so in turn link reassurance and communication and build a trusting relationship between physiotherapist and patient, creating a sense of safety during the session (Table 3, quote 9).

Category 6: Continuity of care

Through continuity of care, a relationship and a manner of communication is developed between physiotherapist and patient. Patients felt that having the same physiotherapist throughout their care helped them to identify the physiotherapist and build a relationship with them. Some felt uncomfortable or upset at having different physiotherapists daily, as continuity of care ensures that the physiotherapist has knowledge of how far the patient has progressed and can manage continued care appropriately (Table 3, quotes 10, 11).

Theme 3. Communication

Communication was noted to be central to the way in which patients understood and interpreted their experience and, ultimately, it influenced their interactions with physiotherapists and satisfaction with the service (Fig. 2).

Category 7: Satisfaction

While patients had different definitions for satisfaction, most equated it to completed and well-handled work, physiotherapy without pain, and goal-orientated service (Table 4, quotes 1, 2). Patients also commented that satisfaction is influenced by the manner with which they were treated and their happiness with the treatment outcomes. Patients reported that the understanding and listening skills of the physiotherapists, as well as their professionalism and attitude towards both the patients and their work, were reasons for satisfaction (Table 4, quotes 3 - 5). The following seven characteristics displayed by physiotherapists added to patients' perception of satisfaction with the service: (i) preparation for the session; (ii) goal setting; (iii) reaching goals; (iv) patience; (v) time spent with patients; (vi) the demonstration of competence; and (vii) attitude and approach to patients. Patients described trust, reassurance, physical assistance, support during sessions, and the building of relationships as being assisting in their satisfaction level (Table 4, quotes 1 - 5). On the other hand, authoritative or poor attitude, poor presentation and untidiness, the possibility of falling during mobilisation, no assistance and no support during activities, and failure to meet established goals were all aspects described by patients as factors that could decrease satisfaction (Table 4, quotes 6, 7). The aforementioned affected their willingness to participate in therapy sessions.

Category 8: Interactions

Patients felt the communication to be good, commenting that interactions between patient and physiotherapist were encouraging and motivational (Table 4, quotes 9, 10). Communication was generally friendly and filled with jokes and laughing, enabling the development of a relationship, a friendship, and thus influencing how patients felt in their sessions (Table 4, quote 11). But communication was not always easy; one patient in particular experienced difficulties due to being intubated and ventilated. Another had difficulties with breathing and was thus distracted, which led to a lack of understanding when the physiotherapist spoke to her (Table 4, quotes 12, 13). Explanations and repeated instructions helped patients to understand what was expected of them. Instructions and communication delivered in a language and tone that the patients could understand further facilitated co-operation (Table 4, quotes 14 - 16). In contrast, when communication was not clear, it resulted in miscommunication that caused loss of trust and refusal of further treatment (Table 4, quotes 17, 18). The importance of non-verbal communication was evident from patients' observations of the interaction between multidisciplinary team (MDT) members. The presence of teamwork between disciplines and among physiotherapists themselves helped to confirm the presence of knowledge and communication (Table 4, quote 19).

Category 9: Patient perception and experience of physiotherapy

Patients perceived physiotherapy in the ICU favourably. They used words such as 'good', 'wonderful', 'excellent' and 'happy' when describing their experience and perception of physiotherapy in the ICU. However, some patients found the experience difficult as communication was not always easy. Their understanding, their expectations and their previous experiences influenced patients' perceptions of physiotherapy (Table 4, quotes 20, 21).

Discussion

Patients offered valuable insight into the factors that influenced their experiences of physiotherapy in the ICU environment. The importance of communication, the development of a trusting relationship and the connections with outcomes emerged as the three themes within which patients experienced the physiotherapy care they received.

While early mobility of critically-ill patients is reported as feasible and safe, the data in this article are the first in which patients verbalised their perception of the pivotal role that early mobility played on their road to recovery. The importance for patients to link an intervention to an outcome that is important to them, has been described within the post-discharge environment.[9] Listening to our patients could facilitate patient-centered care within the critical care context. It is interesting to note that patients identified the same patient-related mobilisation barriers previously documented, namely pain; drips, lines and catheters; and medication. However, their perception of how these barriers can be overcome provides additional information for clinicians working in this environment. The importance of communication, and the development of a trusting relationship, are central to managing barriers.

In the critical care environment, effective communication plays a crucial role in ensuring patient safety and the co-ordination of care among healthcare providers.[37] Our data focussed on physiotherapy care and highlight that communication integrates and influences multiple aspects of physiotherapy care (Fig. 2). Communication affected how the patients understood the care they received and how they felt during mobilisation. Among other aspects, communication also empowered patients through education and shared knowledge, and influenced satisfaction. Communication is a component of care that can easily be overlooked and/or rushed in a busy environment such as the ICU and where most patients have previously been sedated. As is evident in this study, communication has a substantial impact on the patient's perception and, ultimately, their participation. Ashworth[38] reported that communication and information are vital for human beings to feel comfortable, especially people in a strange environment. Effective communication in the ICU, an arguably strange environment, will comfort patients and influence their overall perception of care. Several studies conducted in the critical care setting have reported positively on communication as a component of care with regard to informed consent,[39-41] verbal information,[41] explanations prior to treatment and the use of alternative methods of communication[42] While healthcare practitioners often use non-verbal communication to observe patients' pain levels and ability to participate, our data highlight that patients also observe their environment and the people who interact with them.[43] Patients' ability to notice non-verbal communication within the environment was surprising and novel. The interaction of multidisciplinary team members and of physiotherapists with other patients were two examples of non-verbal cues mentioned by patients, as influencing their perceptions of care and willingness to comply with treatment. Clinicians should be mindful of the impact that communication has on the patients' co-operation with treatment and building the physiotherapist-patient relationship, so increasing trust and patient satisfaction with care. The third theme that emerged from our data was the patient's perception that trust and the individual relationship with a therapist affected their participation in physiotherapy sessions and their health outcome from the ICU. The importance of a trusting relationship in patients' perception of the quality of the care they have received has been well documented. [44] Whether the relationship can improve health outcomes, as patients perceived in our study, is less clear.[45,46] The difficulty for healthcare practitioners working in the critical care environment of developing trusting relationships has been acknowledged.[47] Our data highlight the importance for physiotherapists to gain the trust of their patients in ICU to facilitate patient participation in early mobility activities. Whether that will improve patient outcomes needs investigation.

Our data confirm the feasibility of engaging with patients around the care they received while critically ill. The potential increase in availability of patient perceptions regarding care in the ICU could assist in evaluating and ensuring ICU care quality. Physiotherapists could use

patient satisfaction and perceptions not only to understand the patient's ICU experience, but also to identify potential areas for improvement. Patients are the consumers of care, and their opinions regarding this should be of concern to healthcare providers.[48] Furthermore, patients are the primary elements in the assessment of service quality.[49,50] With such measures, clinicians and healthcare providers can be empowered to provide and monitor patient-centred care with outcomes tailored to what patients desire. The development of patient-reported outcomes could facilitate patient-centred care in the critical care environment.

Study limitations

The data included in this article must be read with caution as they emanate from one centre and one surgical unit and therefore cannot be generalised. However, the credibility of the data is confirmed by the patient selection, the unit structure and the process of data collection. The maximum variation sampling technique we used to select participants resulted in a diverse sample of patients with varying personal and contextual experiences, and enabled a large pooling of differing perceptions and opinions regarding physiotherapy in the ICU. Multiple physiotherapists provided physiotherapy services over the period of data collection, which also included final-year physiotherapy students from two universities. The data therefore reflect physiotherapy services provided by multiple persons and not a single encounter. Finally, data were collected until data saturation, with no new concepts emerging.

Conclusion

Satisfaction with physiotherapy in the ICU is multifactorial. Patients perceived clear communication, the building of a trusting relationship and the focus on outcome as the components which influenced their perception of the physiotherapy service they received in the ICU. While confirming barriers to early mobility, patients perceived participation in mobility activities as a 'jolt' in their journey to recovery following a critical incident. Physiotherapists can now use this information when delivering their service. Moving forward, it is feasible and important to include patient-reported outcomes to measure physiotherapy interventions in the ICU. These data can be used to inform the development of such outcomes.

Declaration. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors. The data that support the findings of our study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because of restrictions; for example, their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgements. The authors gratefully acknowledge all participants in the study.

Author contributions. The authors declare that they all contributed significantly to the preparation of this manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Funding. The authors would like to acknowledge the Medical Research Council (MRC) Self-Initiated Research (SIR) grant 2014 and Harry Crossley (2014) funding organisations for funding the project.

Conflicts of interest. The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Hojat M, Louis DZ, Maxwell K, Markham FW, Wender RC, Gonnella JS. A brief instrument to measure patients' overall satisfaction with primary care physicians. Fam Med 2011;43(6):412-417. [ Links ]

2. Hush JM, Cameron K, Mackey M. Patient satisfaction with musculoskeletal physical therapy care: A systematic review. Phys Ther 2011;91(1):25-36. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20100061 [ Links ]

3. Sun BC, Adams J, Orav EJ, Rucker DW, Brennan TA, Burstin HR. Determinants of patient satisfaction and willingness to return with emergency care. Ann Emerg Med 2000;35(5):426-434. [ Links ]

4. Prakash B. Patient satisfaction. J Cutan Aesthet Surg 2010;3(3):151-155. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2077.74491 [ Links ]

5. Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev 2014;71(5):522-554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558714541480 [ Links ]

6. Brownson RC, Baker EA, Leet TL, Gillespie KN. Evidence-based Public Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [ Links ]

7. Akobeng AK. Evidence in practice. Arch Dis Child 2005;90(8):849-852. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2004.058248 [ Links ]

8. Holland C, Cason CL, Prater LR. Patients' recollections of critical care. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 1997;16(3):132-141. https://doi..org/10.1097/00003465-199705000-00003 [ Links ]

9. Dinglas VD, Faraone LN, Needham DM. Understanding patient-important outcomes after critical illness: A synthesis of recent qualitative, empirical, and consensus-related studies. Curr Opin Crit Care 2018;24(5):401-409. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCC.0000000000000533 [ Links ]

10. So HM, Chan DS. Perception of stressors by patients and nurses of critical care units in Hong Kong. Int J Nurs Stud 2004;41(1):77-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7489(03)00082-8 [ Links ]

11. Cutler LR, Hayter M, Ryan T. A critical review and synthesis of qualitative research on patient experiences of critical illness. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2013;29(3):147-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2012.12.001 [ Links ]

12. Boev C. The relationship between nurses' perception of work environment and patient satisfaction in adult critical care. J Nurs Scholarsh 2012;44(4):368-375. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01466.x [ Links ]

13. Stiller K, Wiles L. Patient satisfaction with the physiotherapy service in an intensive care unit. S Afr J Physiother 2008;64(1),43-46. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajp.v64i1.100 [ Links ]

14. Johannessen G, Eikeland A, Stubberud DG, Fagerstöm L. A descriptive study of patient satisfaction and the structural factors of Norwegian intensive care nursing. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2011;27(5):281-289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2011.07.004 [ Links ]

15. Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009;373(9678):1874-1882. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9 [ Links ]

16. Gosselink R, Needham D, Hermans G. ICU-based rehabilitation and its appropriate metrics. Curr Opin Crit Care 2012;18(5):533-539. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCC.0b013e328357f022 [ Links ]

17. Stiller K. Physiotherapy in intensive care: An updated systematic review. Chest 2013;144(3):825-847. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-2930 [ Links ]

18. Dafoe S, Stiller K, Chapman M. Staff perceptions of the barriers to mobilizing ICU patients. Internet J Allied Health Sci Pract 2015;13(2). https://doi.org/10.46743/1540-580X/2015.1526 [ Links ]

19. Gosselink R, Clerckx B, Robbeets C, Vanhullebusch T, Vanpee G, Segers J. Physiotherapy in the intensive care unit. Netherlands J Crit Care 2011;15(2):66-75. [ Links ]

20. Watanabe S, Hirasawa J, Naito Y, et al. Association between the early mobilisation of mechanically ventilated patients and independence in activities of daily living at hospital discharge. Sci Rep 2023;13(1):4265. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31459-1 [ Links ]

21. Wang YT, Lang JK, Haines KJ, Skinner EH, Haines TP. Physical rehabilitation in the ICU: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2022;50(3):375-388. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005285 [ Links ]

22. Ambrosino N, Janah N, Vagheggini G. Physiotherapy in critically ill patients. Rev Port Pneumol 2011;17(6):283-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rppneu.2011.06.004 [ Links ]

23. Zhang L, Hu W, Cai Z, et al. Early mobilisation of critically ill patients in the intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019;14(10):e0223185. https://doi.org/10.1371/ ournal.pone.0223185 [ Links ]

24. Hanekom, S. Physiotherapy in the intensive care unit. South Afr J Crit Care (Online) 2016;32(1), 3-4. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAJCC.2016.v32i1.293 [ Links ]

25. Hanekom SD, Faure M, Coetzee A. Outcomes research in the ICU: An aid in defining the role of physiotherapy. Physiother Theory Pract 2007;23(3):125-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593980701209204 [ Links ]

26. Latour JM, Kentish-Barnes N, Jacques T, Wysocki M, Azoulay E, Metaxa V. Improving the intensive care experience from the perspectives of different stakeholders. Crit Care 2022;26(1):218. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-04094-x [ Links ]

27. Del Baño-Aledo ME, Medina-Mirapeix F, Escolar-Reina P, Montilla-Herrador J, Collins SM. Relevant patient perceptions and experiences for evaluating quality of interaction with physiotherapists during outpatient rehabilitation: A qualitative study. Physiother 2014;100(1):73-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2013.05.001 [ Links ]

28. Hanekom S, Louw QA, Coetzee AR. The implementation and evaluation of a best practice physiotherapy protocol in a surgical ICU 'unpublished dissertation1. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University; 2010. [ Links ]

29. Hanekom SD, Louw Q, Coetzee A. The way in which a physiotherapy service is structured can improve patient outcome from a surgical intensive care: A controlled clinical trial. Crit Care 2012;16(6):R230. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11894 [ Links ]

30. Hanekom S, Gosselink R, Dean E, et al. The development of a clinical management algorithm for early physical activity and mobilisation of critically ill patients: Synthesis of evidence and expert opinion and its translation into practice. Clin Rehabil 2011;25(9):771-787. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215510397677 [ Links ]

31. Hanekom S, Louw QA, Coetzee AR. Implementation of a protocol facilitates evidence-based physiotherapy practice in intensive care units. Physiother 2013;99(2):139-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2012.05.005 [ Links ]

32. Hunt JM. The cardiac surgical patient's expectations and experiences of nursing care in the intensive care unit. Aust Crit Care 1999;12(2):47-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1036-7314(99)70535-7 [ Links ]

33. Hanekom S, Coetzee A, Faure M. Outcome evaluation of a South African ICU - a baseline study. South Afr J Crit 2006;22(1):14-20. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAJCC3 [ Links ]

34. De Jonghe B, Sharshar T, Lefaucheur JP, et al. Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit: A prospective multicenter study. JAMA 2002;288(22):2859-2867. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.22.2859 [ Links ]

35. van Nes M, Karachi F, Hanekom S. Patient perceptions of ICU care: A scoping review. South Afr J Crit Care 2014;31(3):24-28. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAJCC.237 [ Links ]

36. Maree K, editor. First steps in research. 9th ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers; 2011. [ Links ]

37. Ten Hoorn S, Elbers PW, Girbes AR, Tuinman PR. Communicating with conscious and mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: A systematic review. Crit Care 2016;20(1):333. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1483-2 [ Links ]

38. Ashworth P. The needs of the critically ill patient. Intensive Care Nurs 1987;3(4):182-190. https://doi.org/10.1016/0266-612X(87)90077-0 [ Links ]

39. Novaes MA, Knobel E, Karam CH, Andreoli PB, Laselva C. A simple intervention to improve satisfaction in patients and relatives. Intensive Care Med 2001;27(5):937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001340100910 [ Links ]

40. Clark PA. Intensive care patients' evaluations of the informed consent process. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2007;26(5):207-226. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.DCC.0000286826.57603.6a [ Links ]

41. Modra LJ, Hart GK, Hilton A, Moore S. Informed consent in the intensive care unit: The experiences and expectations of patients and their families. Crit Care Resusc 2014;16(4):262-268. [ Links ]

42. Hafsteindóttir TB. Patient's experiences of communication during the respirator treatment period. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 1996;12(5):261-271. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0964-3397(96)80693-8 [ Links ]

43. Al-Yahyai ANS, Arulappan J, Matua GA, et al. Communicating to non-speaking critically ill patients: Augmentative and alternative communication technique as an essential strategy. SAGE Open Nurs 2021;7:23779608211015234. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608211015234 [ Links ]

44. Brennan N, Barnes R, Calnan M, Corrigan O, Dieppe P, Entwistle V. Trust in the health-care provider-patient relationship: A systematic mapping review of the evidence base. Int J Qual Health Care 2013;25(6):682-688. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzt063 [ Links ]

45. Hall AM, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, Latimer J, Ferreira ML. The influence of the therapist-patient relationship on treatment outcome in physical rehabilitation: A systematic review. Phys Ther 2010;90(8):1099-1110. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20090245 [ Links ]

46. Birkhäuer J, Gaab J, Kossowsky J, et al. Trust in the health care professional and health outcome: A meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017;12(2):e0170988.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170988 [ Links ]

47. Lemmers AL, van der Voort PHJ. Trust in intensive care patients, family, and healthcare professionals: The development of a conceptual framework followed by a case study. Healthcare (Basel) 2021;9(2):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9020208 [ Links ]

48. Ariba AJ, Thanni LO, Adebayo EO. Patients' perception of quality of emergency care in a Nigerian teaching hospital: The influence of patient-provider interactions. Niger Postgrad Med J 2007;14(4):296-301. [ Links ]

49. Goldwag R, Berg A, Yuval D, Benbassat J. Predictors of patient dissatisfaction with emergency care. Isr Med Assoc J 2002;4(8):603-606. [ Links ]

50. Romero-García M, de la Cueva-Ariza L, Jover-Sancho C, et al. La percepción del paciente crítico sobre los cuidados enfermeros: Una aproximación al concepto de satisfacción [Perception of the critical patient on nursing cares: An approach to the concept of satisfaction]. Enferm Intensiva 2013;24(2):51-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfi.2012.09.003 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

F Karachi

fkarachi@uwc.ac.za

Accepted 15 October 2023

Contribution of the study

The study highlights the feasibility and importance of the use of patient-reported outcomes to measure physiotherapy interventions and informs the development of patient reported outcomes and the importance of patient centred physiotherapy care in the ICU setting.