Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Southern African Journal of Critical Care (Online)

On-line version ISSN 2078-676X

Print version ISSN 1562-8264

South. Afr. j. crit. care (Online) vol.39 n.2 Pretoria Jul. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJCC.2023.v39i2.511

RESEARCH

Moral distress among critical care nurses when excecuting do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders in a public critical care unit in Gauteng

S NtsekeI; I CoetzeeII; T HeynsIII

IBCur (I et A), MCur, Dip ICU; Gauteng College of Nursing, Ga-Rankuwa Campus, Pretoria, South Africa

IIBCur (I et A), MCur, PhD, PGCHE, Dip ICU; Department of Nursing Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa

IIIBSoc S, BSoc S (Hons) Critical Care, Dip Trauma, MCur, PhD; Department of Nursing Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: A critical care unit admits on a daily basis patients who are critically ill or injured. The condition of these patients' may deteriorate to a point where the medical practitioner may prescribe or decide on a 'do not resuscitate' (DNR) order which must be executed by a professional nurse, leading to moral distress which may manifest as poor teamwork, depression or absenteeism

OBJECTIVE: To explore and describe factors contributing to moral distress of critical care nurses executing DNR orders

DESIGN: The explorative descriptive qualitative design was selected to answer the research questions posed

METHODS: Critical care nurses of a selected public hospital in Gauteng Province were selected via purposive sampling to participate in the study, and data were collected through semi-structured interviews

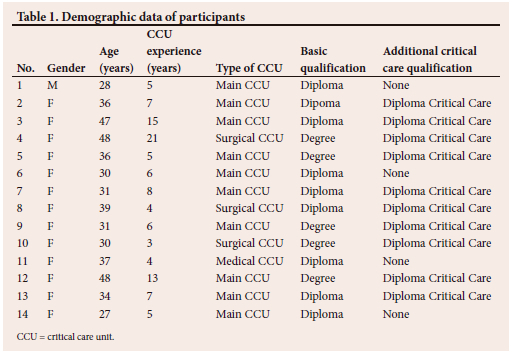

PARTICPANTS: A shift leader assisted with selection of participants who met the eligibility criteria. The mean age of the participants was 36 years; most of them had more than five years' critical care nursing experience. Twelve critical care nurses were interviewed when data saturation was reached. Thereafter two more interviews were conducted to confirm data saturation. A total of 14 interviews were conducted

RESULTS: Tesch's eight-step method was utilised for data analysis. The findings were classified under three main themes: moral distress, communication of DNR orders and unavailability of psychological support for nurses

CONCLUSION: The findings revealed that execution of DNR orders is a contributory factor for moral distress in critical care nurses. National guidelines and/or legal frameworks are required to regulate processes pertaining to the execution of DNR orders. The study further demonstrated the need for unit-based ethical platforms and debriefing sessions for critical care nurses

Contribution of the study

The main contribution of this study was to explore and describe the factors contributing to Moral distress when executing a DNR order. This study raised awareness amongst healthcare providers on the factors contributing to moral distress amongst critical care nurses. This study highlighted the importance of developing national guidelines and legal frameworks pertaining to execution of DNR orders. This study alluded to the value of initiating debriefing sessions for critical care nurses involved in the execution of DNR orders.

A critical care unit admits on a daily basis patients who are critically ill or injured. The condition of some of these patients may deteriorate to a point where the medical practitioner prescribes or decides on a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order, which must be executed by the critical care nurse. The DNR order may be against the critical care nurse's cultural, religious and moral beliefs, as has been confirmed by Vincent,[1] where moral distress was identified as an important issue, particularly in the critical care unit where important decisions regarding patients' outcomes are made and must be executed. Vanderspank-Wright et al.,[2] considered the process of treatment withdrawal as a major source of conflict for professional teams as there might be some delays in executing the order while considering the patient's and family's interest v. the DNR prescription.

DNR orders are a common occurrence in the care of critically ill patients. According to Velarde-García et al.,[3] ~50% of deaths occurring in critical care units are preceded by DNR orders. The definition of a DNR was adopted from a study by Chen et al.,[4] namely that a DNR order implies that resuscitation will not be initiated in the event of cardiopulmonary arrest. The authors in the abovementioned study noted that a DNR order is occasionally extended to prevent implementation of life-sustaining measures before the occurrence of cardiopulmonary arrest. The African perspective on the definition of DNR was adopted from a study by Nankudwa and Brysiewics,[5] where DNR was defined as withholding cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the case of cardiac arrest. The implication acquired from the latter definition is that there is no exclusion of utilisation of life-sustaining measures before the occurrence of cardiac arrest. The authors further raised a concern that DNR orders were delayed to a stage where patient or family participation in the process was almost impossible. An additional finding from a study by Hassan and Ali[6] was that DNR orders are not properly communicated and documented.

Viljoen[7] studied the legal and ethical outcomes of DNR and do-not-attempt-resuscitation (DNAR) orders in South Africa. According to the preceding study, there are no laws nor policies regulating these processes in South Africa, which leaves healthcare providers with uncertainties regarding dealing with end-of-life situations. The condition provided by the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) was also noted, which expects physicians to be considerate when making diagnoses and prescribing treatment; however, upholding the patient's best interest is always emphasised. The South African Nursing Council imposes a duty on nurses to demonstrate high respect for human life according to the nurses' pledge of service, thus adding to the moral distress of this cadre of healthcare providers.

Voget[8] studied the South African perspective on moral distress and observed that generally nurses' training is focused towards saving lives; therefore, when a contrary situation such as a DNR is encountered, emotional distress may be experienced.The author further noted that any work-related emotional turmoil experienced by nurses was either referred to as burnout or compassion fatigue. The resulting concern was that such erroneous labelling of moral distress may result in management not recognising the professional, social and personal impact of moral distress on nurses, thus resulting in implementation of measures to control the phenomenon being misdirected.

Moral distress affects a nurse's performance in the workplace negatively; this was confirmed by Allen[9] who not only discussed moral distress in phases, but also emphasised the impact of the second phase of the phenomenon. Ignoring the occurrences of moral distress associated with end-of-life care promotes extensive moral residue. The outcomes of moral residue on nurses, especially after exposure to several morally distressful situations, may lead to psychological complications, including anxiety, depression, poor patient care and increased turnover. Voget[8] further identified desensitisation of nurses as an undesirable outcome of moral distress.

Methods

Design

The explorative descriptive qualitative approach was selected for this study, as explained by Hunter[10] as an approach that will enable achievement of the research aim. The study aims to explore and describe the factors contributing to the moral distress experienced by critical care nurses on execution of DNR orders. Semi-structured interviews utilised with exploratory-descriptive qualitative (EDQ) research enabled the researcher to explore the perceptions of participants and to probe for clarification of issues.

Setting

The study was conducted at one of the biggest academic hospitals in Gauteng Province, South Africa, with patient referrals from within the Gauteng, North-West and Limpopo provinces for various specialities. The hospital has a 22-bed adult multidisciplinary critical care unit with 81 professional nurses, and three high-care units for medical, surgical and neurological cases with 20 professional nurses allocated to each unit.

Participants

Purposive sampling was applied for the selection of participants in the current study, based on the description by Brink et al.[11] as a non-probability sampling technique which is dependent on the researcher's judgement. The eligibility criteria for the study were critical care nurses with a minimum of one year's experience in a critical care unit, and they should have nursed critically ill/injured patients subject to a DNR order. These eligibility criteria would according to Polit and Beck[12] enable selection of participants who are capable of providing the researcher with rich data. Critical care shift leaders assisted with the selection of suitable participants who met the eligibility criteria. Twelve critical care nurses were interviewed when data saturation was reached, and two more interviews were conducted to confirm data saturation. Demographic data of participants are presented in Table 1; their mean age was 36 years and most of the participants had more than five years of critical care nursing experience.

Ethical considerations

It was suggested by Brink et al.[11] to comply with measures to ensure protection of human subjects in research, and to include ethical approval of the study by an appropriate review board. In the present study, ethical consideration was ensured by obtaining approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the University of Pretoria and of the Gauteng Department of Health. Permission was also sought from the ethics committee of the hospital concerned as well as from managers of the respective units where the study was conducted. According to Polit and Beck,[12] compliance with the Nuremberg Code and the Declaration of Helsinki was also thus ensured for protection of participants. For compliance with the self-determination of human subjects, informed consent was obtained after explanation of the procedure and informing participants about their right to withdraw from the study whenever they wished. The researcher's personal laptop with a password known only to her was utilised for storing transcripts and data to ensure confidentiality. To ensure anonymity and that data could not be traced back, numbers were used to identify each participant.[12]

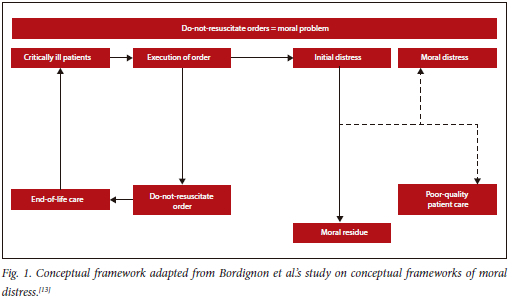

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted during July - August 2021. The interviews ranged from 30 to 45 minutes, were conducted in English and audio-taped with the consent of the participants, and transcribed verbatim by the researcher. Participants were asked one open question, i.e. 'What was your experience when nursing a patient with a do-not-resuscitate order?' The probes were dependent on partipant responses and the conceptual framework below (Fig. 1).

Data analysis

The researcher used Tesch's eight-step method for data analysis as follows:[14]

Read through all data carefully to make sense of the whole. Read through the transcripts again to better comprehend the underlying meanings. Write down thoughts and main themes in the margins. Make a list of main topics from the data. Group similar topics together to form themes. Abbreviate the themes as codes next to the appropriate segments of the text. Find the most descriptive words for the themes and turn them into categories. Reduce the total list of categories and group them into related topics in collaboration with the co-coders.

Rigour

In this study, the researcher applied the strategies of credibility, dependability, transferability and confirmability to ensure trustworthiness.[15] Credibility and dependability were ensured by prolonged engagement with participants and allowing the latter to review the researcher's interpretation of the data. Confirmability refers to objectivity, and avoidance of researcher bias and manipulation of data. The researcher remained objective throughout and utilised reflexivity to ensure confirmability. In addition, the purposive selection of participants with sufficient knowledge of the phenomenon (DNR) under study, as well as encouraging them to be open and unconfined, promotes the provision of thick descriptions, thus ensuring transferability.

Results

The researcher initially interviewed the 12 professional nurses who agreed to participate in the study. Thereafter, two more participants were added to confirm data saturation. The identified themes and categories were reduced to three related topics, according to Tesch's eight-step method which was described under Data Analysis.[14] The three main themes that emerged were: (i) moral distress related to executing a DNR order; (ii) communication of the DNR order; and (iii) unavailability of psychological support for critical care nurses.

Moral distress related to excecuting a DNR order

All 14 participants had nursed patients with DNR orders while their predominant value was to preserve life as far as possible. The experience of participating in executing DNR orders was described as depressing and causing moral distress.

You feel so stressed that you feel like you can do something, but nothing can be done... (Participant 4)

... moral distress, it's like you leave your patient in danger, you know, you feel guilty as if something can be done because no one wants to die... (Participant 3) ... the stress actually began the moment when the doctor says do not escalate the treatment and a DNR is signed, it goes against my beliefs, my values ... (Participant 9)

Communication of the DNR order

Participants referred to the DNR order as conflicting as far as execution was concerned, as there were no guiding policies or standard operating procedures. There was also uncertainty related to communication of the order. Participants stated that the DNR order was occasionally made verbally or that the written order was not always clear.

Sometimes the DNR order is verbalised but not written . this causes stress because if I do it and someone asks where was it written ... and if I don't do it, the doctor will shout at us ... (Participant 6) . it is not clear that when we do not resuscitate, what exactly do we do, must we switch off the machine or must we wean off the ventilation and what? (Participant 2)

The doctors sometimes ignored the DNR order; for example, one participant said: . the doctor complain that the blood pressure is 80/50. The doctor said give bolus. So you become so confused but in the morning he said, do not resuss, so now he says I must give a bolus ... (Participant 3)

Unavailability of psychological support for nurses

Participants described their experience as emotionally draining and stressful. Their experience was that after the patient with a DNR order dies, the nurse needs to continue as if nothing had happened.

. immediately after the patient died following the DNR order, I had to prepare for another admission, even if I was crying for the patient who passed on . I had to smile for the new relative ... (Participant 10)

. we are given opportunity to maybe talk to a counsellor, but it doesn't happen. Since the unit is always very busy, you suffer in silence. (Participant 6) . you feel depressed and having conflict in yourself to do things that is against your culture and beliefs ... (Participant 5)

Discussion

The study aimed to explore and describe the factors contributing to moral distress experienced by critical care nurses on execution of DNR orders.

Participants in the current study, as in that by Voget,[8] were not familiar with the term 'moral distress' but had an understanding of values and ethical considerations of the profession. The DNR order was perceived by participants as restricting what is known to be right, what has been pledged; or is against oaths taken. Cuba[15] clarified the two phases of moral distress as the initial phase experienced, for example, while nursing a patient with a DNR, and the second phase - termed moral residue - which occurs after the patient has died.

Participants in the present study further equated complying with a DNR order as being uncaring to critically ill patients even though it was clear that nothing more could be done. Campbell et al[16] studied the ethical reasoning associated with DNR orders and found that DNR orders exposed healthcare providers to some form of ethical dilemma, especially when considering the attitude of caring.

In the current study, participants pointed to the caring function of a nurse throughout the lives of their patients. In the work by Campbell et al.,[16] it was easier for participants to adhere to some values, such as explaining that they would continue providing care for the patient; and to avoid mentioning what they would not do, which implied complying with the DNR order. The authors also acknowledge their participants' view: that ethical reasoning may be situation based, where they considered the dentological perspective based on the premise of not doing harm; and the utilitarian perspective based on upholding patient autonomy. The authors further advocate replacing DNR orders with the term 'allow for natural death to occur', which was considered to be less stressful for nurses. Another important observation of Campbell et al[16] was that the existence of rules regulating DNR orders might not always be the solution, because healthcare providers need ethical competence for effective implementation of the rules.

Participants of the current study also raised instances where resuscitation of patients with poor quality of life was morally distressing owing to prolonging the patient's suffering, and that it interferes with the equitable allocation and utilisation of hospital resources. Akdeniz et al.[18] analysed the ethical considerations of end-of-life care and maintained that the goals of care during this period assist in the relief of suffering for the patient and family in all possible ways. The authors emphasise the importance of protection of the rights and dignity of the patient. The authors further recommend collective communication by healthcare providers, the family and the patient as measures that could decrease the exacerbations of ethical dilemmas.

The results of the current study demonstrated that a DNR order does not restrict the implementation of resuscitative measures, and that the different means by which the order is communicated may affect its execution. Participants also raised a concern about verbalised DNR orders, as reported by Nankudwa and Hassan.[5,6] Participants also considered verbal DNR orders as contributing to moral distress which not only interferes with quality patient care but also with communication with relatives. This was confirmed by Vu[19] after conducting an ethical systematic review on DNR orders where the conclusion was that the orders lack clarity, and as yet no proper documentation guidelines exist globally, despite many years of implementation of such orders. The authors noted that this lack of documented guidelines for DNR orders contributes to workplace ethical challenges and moral distress among nurses.

Articulation of the order poses a challenge in the South African context, especially because of uncertainties associated with absence of legal and regulatory mechanisms.[7] In the current study, participants confirmed that when such orders were written by physicians, the orders were not uniform, and they differed. Dzeng et al[20] looked into articulation of DNR orders in the USA, where advanced care directives have been approved. The current authors noted that physicians faced with making such decisions still find it difficult to articulate the order, despite having approval of the patient and relatives' contribution in the decision-making process.[19] The authors further noted other factors including institutional cultural norms, prioritisation of patient autonomy and consideration of the principle of beneficence as having an impact on physicians' conceptualisation of a DNR order.[20] The authors confirmed that unclear DNR orders often result in futile care being provided and hospitals incurring increased costs without any mortality improvement. The authors recommend that intervention measures that are developed must be targeted at mitigating institutional cultures and ethical value systems of physicians and nurses as they influence the attitudes, beliefs and norms guiding communication practices.[20]

Participants in the current study were further concerned about the absence of communication guidelines between physicians and nurses regarding DNR orders as this leads to confusion regarding continuing management of the patient, as found in a survey conducted on practices at end of life in a certain group of hospitals in Egypt.[21] The outcomes of the survey revealed that physicians feared litigation especially as there was no legal provision regarding DNR. The authors further noted that these physicians supported life-sustaining measures including feeding and hydration as being morally right during end-of-life care. In the current study, participants were concerned about the lack of clarity regarding actual performance of a DNR order and felt that DNR orders produced a reluctance to go the extra mile in providing care for critically ill patients, as in Azab et al.[21] where it was explained that a DNR order impacts negatively on nursing care for patients due to widening of the meaning of the concept beyond withholding of cardiopulmonary resuscitation on the occurrence of cardiac arrest.

Participants in the current study described their experiences of managing patients with DNR orders as emotionally draining and morally stressful. Kelly et al.[22] studied end-of-life care in the critical care unit and made recommendations which include assessing the impact of the situation on the nurse, and determining the need for immediate debriefing by the manager or referral for professional help. Jensen et al.[23] observed that end-of-life care situations that are not properly managed may lead to burnout and moral distress. The authors further recommended occasional end-of-life discussions by nurses as measures that may assist the development of best practices in the critical care unit.

Participants in the current study also raised concerns about the lack of debriefing, and suggested reporting DNR cases to nursing management. Turale et al.[24] considered the ethical challenges brought about by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic to nursing care at end of life. The authors' recommendations were that nurses endeavour to strike a balance between their professional duty and ethical competence because the pressure of work is high and opportunities for ethical meetings are scarce or non-existent. The authors, however, noted that nurses need to be involved in policy development and require strong leaders and direction as they continue to save lives, prevent suffering and care for communities.

Limitations

The study was limited to one hospital in Gauteng Province, which might affect the generalisability of findings. The researcher also focused on critical care nurses with more than one year's experience, whereas end-of-life care and DNR orders might have had a bigger impact on newly qualified critical care nurses.

Conclusion

Clearly defined guidelines and standard operating procedures pertaining to DNR processes should be developed collaboratively. Open communication and clarifying the exact meaning of a DNR order and the actual executing of the order need to be clearly understood by all parties involved. The study further demonstrated the need for unit-based ethical discussion platforms and debriefing sessions for supporting critical care nurses involved in executing DNR orders.

Declaration. Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the University of Pretoria and the Gauteng Department of Health. Permission was also sought from the ethics committee of the hospital concerned and from managers of the respective units where the study was conducted. Informed consent was obtained from participants and they were also made aware of their right to withdraw from the study whenever they felt uncomfortable.

Acknowledgements. The authors thank the critical care nurses who participated in this study, and Ms I Cooper for her editing work.

Author contributions. All three authors contributed to all components of the planning, compilation and review of the manuscript. Data collection and analysis was done by the researcher (SN) and co-coded by the research supervisors.

Funding. None received.

Conflicts of interest. The authors declare that there was no competing interest.

References

1. Vincent H. Relationships of moral distress among interprofessional ICU teams (2018). UT SON Dissertations (Open Access). 25. [ Links ]

2. Vanderspank-Wright B, Efstathiou N, Vandyk AD. Critical care nurses' experiences of withdrawal of treatment: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Int J Nurs Stud 2018;77:15-26. [ Links ]

3. Velarde-García JF, Luengo-González R, González-Hervías R, et al. Limitation of therapeutic effort experienced by intensive care nurses. Nurs Ethics 2018;25(7):867-879. [ Links ]

4. Chen Y-S, Chen Y, Chu T-S, Lin KH, Wu CC. Further deliberating the relationship between do-not-resuscitate and the increased risk of death. Sci Rep 2016;6:23182. [ Links ]

5. Nankudwa E, Brysiewics P. Lived experiences of Rwandan ICU nurses caring for patients with do-not-resuscitate order. South Afr J Crit Care 2017;33(1):19-21. [ Links ]

6. Hassan CP, Ali AM. Do-not-resuscitate orders: Islamic viewpoint. Int J Human Health Sci 2018;2(1):8-12. [ Links ]

7. Viljoen C. Pre-hospital care and do not attempt to resuscitate orders: The legal and ethical consequences 'doctoral dissertation, University of the Free State1. 2017. [ Links ]

8. Voget U. Professional nurses' lived experiences of moral distress at a district hospital 'doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch University1. 2017. [ Links ]

9. Allen R. Addressing moral distress in critical care nurses: A pilot study. Int J Crit Care Emerg Med 2016;2(2):2474-3674. [ Links ]

10. Hunter D, McCallum J, Howes D. Defining exploratory-descriptive qualitative (EDQ) research and considering its application to healthcare. J Nurs Health Care 2019;4(1). [ Links ]

11. Brink H, Van der Walt C, Van Rensburg G. Fundamentals of Research Methodology for Healthcare Professionals. 4th ed. Cape Town: Juta; 2018. [ Links ]

12. Polit FD, Beck TC. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. 10th ed. Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia; 2021. [ Links ]

13. Bordignon SS, Lunardi VL, Barlem ELD, Dalmolin GdL, da Silveira RS, Ramos FRS, Barlem JGT. Moral distress in undergraduate nursing students. Nursing Ethics 2019;26(7-8):2325-2339. [ Links ]

14. Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2014. [ Links ]

15. Guba EG. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Ed Com Technol J1981;29:75-91. [ Links ]

16. Campbell S M, Ulrich C, Grady C. A broader understanding of moral distress. In: Ulrich CM, Cady C, editors. Moral distress in the health professions. New York: Springer, 2018; 59-77. [ Links ]

17. Pettersson M, Hedström M, Höglund AT. The ethics of DNR decisions in oncology and hematology care: A qualitative study. BMC Med Ethics 2020;21(1):1-9. [ Links ]

18. Akdeniz M, Yardimci B, Kavukcu E. Ethical considerations at the end-of-life care. SAGE Open Med 2021;9:20503121211000918. [ Links ]

19. Vu B. Ethical considerations of DNR orders from nursing perspective/DNR-päätöksen eettiset näkökohdat hoitotyön näkökulmasta. 2019. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-201903153191 (accessed 15 August 2022). [ Links ]

20. Dzeng E, Curtis JR. Understanding ethical climate, moral distress, and burnout: A novel tool and a conceptual framework. BMJ Quality Safety 2018;27(10):766-770. [ Links ]

21. Azab S, Abdul-Rahman SA, Esmat IM. Survey of end-of-life care in intensive care units in Ain Shams University Hospitals, Cairo, Egypt. HEC Forum 2020:1-15. [ Links ]

22. Kelly PA, Baker KA, Hodges KM, Vuong EY, Lee JC, Lockwood SW. Nurses' perspectives on caring for patients with do-not-resuscitate orders. Am J Nurs 2021;121(1):26-36. [ Links ]

23. Jensen HI, Halvorsen K, Jerpseth H, Fridh I, Lind R. Practice recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurse 2020;40(3):14-22. [ Links ]

24. Turale S, Meechamnan C, Kunaviktikul W. Challenging times: Ethics, nursing and the COVID-19 pandemic. Int Nurs Review 2020;67(2):164-167. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

S Ntseke

Sarah.Ntseke2@gauteng.gov.za

Accepted 28 May 2023