Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Southern African Journal of Critical Care (Online)

On-line version ISSN 2078-676X

Print version ISSN 1562-8264

South. Afr. j. crit. care (Online) vol.36 n.2 Pretoria Nov. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJCC.2020.v36i2.435

ARTICLE

Exploring moral distress among critical care nurses at a private hospital in Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa

W EmmamallyI; O ChiyangwaII

IB Nursing, M Nursing, PhD; OrcID 0000-0002-3378-6105; Discipline of Nursing, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIB Nursing, BSc (Hons); OrcID 0000-0002-0970-8502; Discipline of Nursing, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Moral distress resulting from frequent and intense exposures to morally challenging encounters with critically ill patients, their families and other healthcare professionals negatively impacts on the personal and professional wellbeing of critical care nurses.

OBJECTIVE. To determine the frequency, intensity and overall severity of moral distress among critical care nurses working in the critical care environment of a private hospital in the eThekwini district of KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa.

METHODS. A descriptive survey was conducted using a 21-item moral distress scale revised questionnaire. We assessed the influence of sociodemographic variables of the respondents on the moral distress composite scores.

RESULTS. The moral distress composite scores of the 74 critical care nurses who completed the questionnaires ranged from 0 - 303 out of a possible 336. The mean (standard deviation (SD)) composite moral distress score was 112.12 (73.21). Analysis of the relationship between sociodemographic variables and the moral distress composite scores revealed that female respondents experienced higher distress scores than males (p=0.013). There was an inverse relationship between composite scores and an increase in age (p=0.009) and years of service (p=0.022).

CONCLUSION. The mean composite score of the critical care nurses was suggestive of moderate levels of moral distress. Counselling services and empowerment skills training are advocated to support critical care nurses to manage moral distress.

Keywords: moral distress; critical care nurse; critical care unit.

Nurses working in critical care units (CCUs) are repeatedly exposed to unique ethical dilemmas that include lack of end of life conversations, concerns regarding optimal pain management of patients, and conflicting concerns with physicians regarding patients' treatments, which require decisions that often conflict with their personal and professional values.[1,2] Prolonged exposure to ethical dilemmas in an unsupportive practice environment places critical care nurses (CCNs) at high risk of moral distress. According to Corrado and Molinaro,[3] moral distress refers to feelings of guilt, powerlessness and anger experienced by healthcare professionals in situations where they are unable to practice according to their professional and personal values. Personal or intrinsic manifestations of moral distress include insomnia, tiredness, anguish and anxiety, and extrinsic or professional manifestations such as absenteeism, job dissatisfaction, burnout or a decision to resign.[2,4] In an attempt to counteract the negative consequences of moral distress on the quality of healthcare provided to critically ill patients, there has been an increase in studies aimed at identifying factors that increase moral distress in CCNs[5,6] as well as surveys of moral distress in CCNs. [7,8] In South Africa (SA), there has been a concentration of studies on moral distress in healthcare professionals working in CCUs of the state-funded healthcare sector,[9-11] with fewer studies conducted in CCUs of the private healthcare sector.[12] This may be due to common assumptions that the private healthcare sector is associated with fewer ethical challenges and stressors than the state-funded healthcare sector. However, the Econex report[13] did much to dispel misconceptions regarding patient numbers and allocation of resources between the state-funded and private healthcare sectors, reporting that patient numbers in the private sector are increasing drastically as patients seek quality healthcare perceived to be provided by the private sector. CCNs working in the private healthcare sectors now face pressures to increase quality of care without increasing expenditure,'131 a pressure that has been known to compromise quality of care and cause moral distress in CCNs.[1] The report indicated a similar need for robust research on moral distress among healthcare professionals in the private sector.

Method

A quantitative descriptive survey was conducted in four CCUs of a private hospital in KwaZulu-Natal Province, SA. Purposive sampling identified 74 respondents from the target population of CCNs. The inclusion criteria for respondents were: (i) nurses registered with South African Nursing Council (SANC) as a professional nurse with a four-year diploma and/or degree in nursing; (ii) a nurse with a two-year certificate, enrolled with SANC; and (iii) nurses working in the CCU for a period >12 months. A specialisation in critical care nursing was not a criterion. A questionnaire comprising two parts was used to collect data from respondents. Section A, developed by the researchers, focused on sociodemographic variables of respondents, namely age, gender, marital status, work experience in CCU, and qualifications in nursing. Section B, the moral distress scale-revised (MDS-R) questionnaire, consisted of 21-items of clinical situations believed to be morally distressing to healthcare professionals. Respondents were asked to rate each item in terms of how frequently they had come across the situation in their work and how disturbing (intensity) they found the situation.[14] The frequency of the item (situation) rates from 0 (never) to 4 (very frequently) and the intensity of moral distress rates from 0 (none) to 4 (great extent). Items that were encountered frequently and were more distressing have higher scores.[8,14] The composite score for moral distress (overall severity of moral distress) is obtained by adding the composite scores of each item and ranges from 0 - 336. Total composite scores for the scale may be broken down into three categories, with low levels of moral distress ranging from 0 - 84, moderate levels of moral distress ranging from 85 - 168, and high levels of moral distress ranging from 169 - 336.[8-Permission to use the questionnaire was obtained from the developer.

Content validity was established through alignment of the questionnaire with the objectives of the study and the moral distress theory.[15] Cronbach's alpha for the MDS-R through piloting of the questionnaire revealed high internal consistency at alpha=0.89, consistent with the questionnaire's established value. Two specialist critical care nurses confirmed the face validity of the questionnaire.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of KwaZulu-Natal human ethics committee (ref. no. HSS/1587/018H). Data were collected between November and December 2018. Data collection occurred in a private room at the hospital, where respondents completed the questionnaire and handed it in sealed envelopes to the researcher who waited outside the room. Respondents were briefed on the purpose of the study and provided with an information sheet that detailed their voluntary involvement in the study, and the processes taken to assure their anonymity during and after the study. Written informed consent was obtained prior to data collection.

Data were analysed using SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp., USA). Composite scores were computed to determine the overall severity of moral distress of respondents. Mean composite scores were calculated for frequency and intensity of each item. Statistical analyses included an independent sample t-test to assess the influences of sociodemographic variables (gender, age, experience and qualifications of respondents) on the moral distress composite scores. Significance was set al p<0.05.

Results

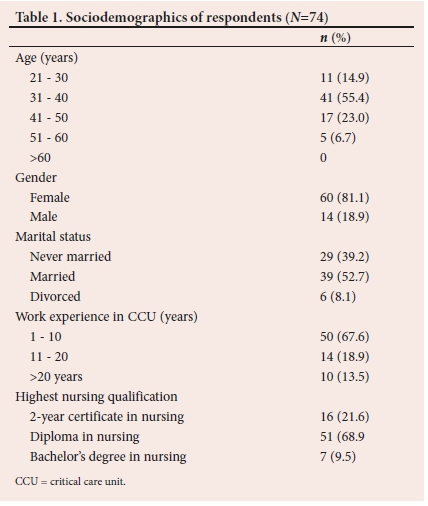

A total of 74 CCNs completed the questionnaire (100% response rate). More than half of the respondents fell within the age range of 31 - 40 years (55.4%; n=41). The majority of the respondents (81.1%; n=60) were female and 18.9% (n=14) were male. Thirty-nine (52.7%) respondents were married. More than half of the respondents had 1 - 10 years' work experience in CCUs (67.6%; n=50). Most of the respondents (68.9%; n=51) had a diploma in nursing (Table 1).

The composite moral distress scores (MDS-R) of the respondents ranged from 0 - 303 out of a possible 336. The mean (standard deviation (SD)) composite MDS-R score was 112.12 (73.21), indicating moderate levels of moral distress.

The mean frequency scores ranged from 1.03 - 2.51 out of a possible 4 (Table 2). The highest-scored item was, 'continue to participate in care for a hopelessly ill person who is being sustained on a ventilator, when no one will make a decision to withdraw support.' The mean level intensity (degree of disturbance) scores ranged from 1.47 - 2.57 out of a possible 4 (Table 2). The highest-scored item was, 'continue to participate in care for a hopelessly ill person who is being sustained on a ventilator, when no one will make a decision to withdraw support.'

There was no significant relationship between the sociodemographic variables and MDS-R composite scores with the marital status and qualifications of respondents. However, significant associations were noted between MDS-R composite scores and gender of respondents (p=0.013), age (p=0.009) and years of experience in CCU (p=0.022). There was an inverse relationships between composite scores and an increase in age and years of service.

Discussion

The mean composite MDS-R score of 112.12 found in this study was suggestive of moderate levels of moral distress. These results were comparable with a national study by Langley et al.[9] which reported that CCNs experience considerable distress. However, our mean composite score was higher than the composite scores (70 - 92) reported in the international literature for CCNs.[7,16,17] Most studies conclude that moral distress in healthcare professionals can escalate to burnout, increased medico-legal errors and increased turnover, all of which impact negatively on the quality of healthcare provided to patients and their significant others.[5,18] In contrast, a study by Henrich et al.[19] revealed that the presence of moral distress positively impacted healthcare workers by increasing their vigilance and compassion for critically ill patients. Bearing in mind the negative consequences of moral distress on healthcare professionals working in CCUs, hospital managements may institute strategies such as counselling and debriefing sessions to assist CCNs cope with moral distress.[20]

The item identified as the most morally distressing in both frequency and intensity was the provision of overly aggressive or futile treatment to critically ill patients, which is in line with previous findings in the literature.[21,22] These findings highlight how technological advancements and new treatments aimed at prolonging life may have increased the moral distress faced by CCNs. Similarly, nurses in other studies stated that providing futile care caused them to experience negative feelings such as powerlessness and distress.[4,23] According to Berhie et al.,[24]increased attention must be given to teaching CNNs positive adaptive mechanisms to reduce the negative effects of futile care. There is a need for CCNs to participate actively in ongoing discussions on patients' treatment plans and to advocate for treatment that impacts positively on the quality of patients' lives. Other items with high ratings of moral distress frequency and intensity were CNNs doubting their own or their colleagues' competence in caring for patients. Such situations if unresolved may lead to either a loss of self-confidence or deterioration of teamwork, which can jeopardise patient safety.[25] Items of feeling obligated to honour the family's requests even if the CCN believed this was not in the best interest of the patient also received high ratings of moral distress frequency and intensity. This is most likely related to the narratives of powerlessness that dominate in the field of nursing. According to Morley,[26] nurses must strive for ethical competence so that they can confidently enact their role as patient advocates.

The finding of higher levels of moral distress among female respondents compared with their male colleagues has been identified in other studies[7,27] and may be attributed to an assertion that females tend to report higher levels of symptoms of stress.[26] This assertion has significant implications for the healthcare sector, firstly because nursing is a female-dominated profession, and secondly because nurses make up the greater percentage of the nursing workforce. Therefore, effort must be invested in identifying the sources of moral distress in CCUs and in developing empowering strategies to effectively address moral distress in the workplace.

The inverse relationships between the composite scores of moral distress in the respondents and an increase in age and years of service found in the current study can be attributed to the fact that experienced and senior CCNs develop coping mechanisms and the autonomy not to participate in actions that make them uncomfortable.[28] This finding bodes well for CCUs in this study as senior personnel can be invited to mentor their younger colleagues in utilising strategies that have enabled them to attain moral competence.

A noted limitation of this study was its confinement to one private hospital, thereby limiting generalisation of findings to CCUs in other private or state-funded hospitals. Further studies exploring moral distress in CCNs in both private and state-funded hospitals are advocated, including comparative studies of moral distress in CCNs between hospitals. Additionally, we recommend that future studies not only determine the frequency and intensity of morally distressing situations among CCNs but also go further to identify how moral distress has impacted on CCNs personally and professionally. Data attained from these studies will inform the development of strategies to promote a morally healthier working environment for CCNs.

Conclusion

CNNs experienced moderate levels of moral distress in this study. It is suggested that training sessions on strategies for self-empowerment as well as reflective counselling and debriefing be offered to CNNs. The resources and support may enable CCNs to acknowledge and manage their moral distress. Providing overly aggressive or futile treatment was scored by respondents as the most morally distressing item in both frequency and intensity. We suggest that it is essential to engage CCNs in platforms regarding decisions on patient care so that they may give their input and verbalise their dissatisfaction with decisions on providing aggressive or futile treatments.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. None.

Author contributions. Equal contributions.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Henrich NJ, Dodek PM, Alden L, Keenan SP, Reynolds S, Rodney P. Causes of moral distress in the intensive care unit: A qualitative study. J Critical Care 2017;35:57-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.04.033 [ Links ]

2. Qalawa ASA, Hassan HE. Implications of nurse's moral distress experience in clinical practice and their health status in obstetrics and critical care settings. Clin Pract 2017;6(2):15-25. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.cp.20170602.01 [ Links ]

3. Corrado AM, Molinaro ML. Moral distress in health care professionals. Univ Western Ontario Med J 2017;86(2):32-34. https://doi.org/10.5206/uwomj.v86i2.2006 [ Links ]

4. Weinzimmer S, Miller S, Zimmerman J, Hooker J, Isidro S, Bruce CR. Critical care nurses' moral distress in end-of-life decision making. J Nurs Edu Prac 2014;4(6):6-12. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v4n6p6 [ Links ]

5. Allen R, Butler E. Addressing moral distress in critical care nurses: A pilot study. I J Crit Care Emerg Med 2016;2(1):1-6. https://doi.org/10.23937/2474-3674/1510015 [ Links ]

6. Epstein EG, Delgado S. Understanding and addressing moral distress. Online J Issues Nurs 2010;15(3):1-17. https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol15No03Man01 [ Links ]

7. Colville GA, Dawson D, Rabinthiran S, Chaudry-Daley Z, Perkins-Porras L. A survey of moral distress in staff working in intensive care in the UK. J Intensive Care Society 2019; 20(3):196-203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1751143718787753 [ Links ]

8. Gonzales J. Exploring the presence of moral distress in critical care nurses. Master's thesis. Providence: Rhode Island College, 2016. https://doi.org/10.28971/532016GJ79 [ Links ]

9. Langley G, Kisorio L, Schmollgruber S. Moral distress experienced by intensive care nurses. Southern Afr J Crit Care 2015;31(2):36-41. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAJCC.2015.v31i2.235 [ Links ]

10. Naidoo V. Experiences of critical care nurses of death and dying in an intensive care unit: A phenomenological study. Master's thesis. Durban: Durban University of Technology, 2011. http://ir.dut.ac.za/handle/10321/730 [ Links ]

11. Voget U. Professional nurses' lived experiences of moral distress at a district hospital. Master's thesis. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University ,2017. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f113/0cc4afae472040fcc7b667f80ac0520b933b.pdf [ Links ]

12. Ragavadu R. The impact of moral distress on the provision of nursing care among critical care nurses in the eThekwini district. Master's thesis. Durban: Durban University of Technology, 2016. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a932/1755d5abf040bc87b9849d86027e21293f93.pdf [ Links ]

13. Econex. The South African private healthcare sector: Role and contribution to the economy; 2013:1-65. https://econex.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/econex_researchnote_32.pdf [ Links ]

14. Hamric AB, Borchers CT, Epstein EG. Development and testing of an instrument to measure moral distress in healthcare professionals. AJOB Primary Research 2012;3(2):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507716.2011.652337 [ Links ]

15. Corley MC. Nurse moral distress: A proposed theory and research agenda. Nurs Ethics 2002;9(6):636-650. https://doi.org/10.1191/0969733002ne557oa [ Links ]

16. Karanikola MNK, Albarran JW, Drigo E, et al. Moral distress, autonomy and nurse-physician collaboration among intensive care unit nurses in Italy. J Nurs Manag 2014;22(4):472-484. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12046 [ Links ]

17. Dodek PM, Wong H, Norena M, et al. Moral distress in intensive care unit professionals is associated with profession, age, and years of experience. J Crit Care 2016;31(1):178-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.10.011 [ Links ]

18. Mealer M, Moss M. Moral distress in ICU nurses. Intensive Care Med 2016;42(10):1615-1617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4441-1 [ Links ]

19. Henrich, NJ, Dodek PM, Gladstone E, et al. Consequences of moral distress in the intensive care unit: A qualitative study. Am Assoc Crit Care Nurses 2017;26(4):e48-e57. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2017786 [ Links ]

20. Hamric AB, Epstein EG. A health system-wide moral distress consultation service: Development and evaluation. HEC Forum 2017;29(2):127-143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-016-9315-y [ Links ]

21. Burston AS, Tuckett AG. Moral distress in nursing: Contributing factors, outcomes and interventions. Nurs Ethics 2013;20(3):312-324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733012462049 [ Links ]

22. Wiegand DL, Funk M. Consequences of clinical situations that cause critical care nurses to experience moral distress. Nurs Ethics 2012;19(4):479-487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733011429342 [ Links ]

23. Obolensky L, Clark T, Matthew G, Mercer M. A patient and relative centred evaluation of treatment escalation plans: A replacement for the do-not-resuscitate process. J Medical Ethics 2010;36(9):518-520. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2009.033977 [ Links ]

24. Berhie AY, Tezera ZB, Azagew AW. Moral distress and its associated factors among nurses in Northwest Amhara Regional State Referral Hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2020; 2020(13): 161-167. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S234446 [ Links ]

25. Karakachian A, Colbert A. Moral distress: A case study. Nursing 2017;47(10):13-15. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000525602.20742.4b [ Links ]

26. Morley G. What is 'moral distress' in nursing? How can and should we respond to it? J Clin Nurs 2018;27(19-20):3443-3445. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14332 [ Links ]

27. Disch J. Rethinking mentoring. Crit Care Med 2018; 46(3):437-441. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002914 [ Links ]

28. O'Connell CB. Gender and the experience of moral distress in critical care nurses. Nurs Ethics 2015;2(1):32-42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733013513216 [ Links ]

29. Borhani F, Abbaszadeh, Nakhaee N, Roshanzadeh M. The relationship between moral distress, professional stress, and intent to stay in the nursing profession. J Med Ethics Hist Med 2014;7(4):1-8. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

W Emmamally

Emmamally@ukzn.ac.za

Accepted 20 July 2020

Contribution of the study. Findings of the study can be used to identify sources of the distress, potential interventions, as well as the risks and benefits of taking action to assist critical care nurses to overcome moral distress.