Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Southern African Journal of Critical Care (Online)

On-line version ISSN 2078-676X

Print version ISSN 1562-8264

South. Afr. j. crit. care (Online) vol.36 n.2 Pretoria Nov. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJCC.2020.v36i2.431

ARTICLE

Physiotherapists' perceptions of collaborations with inter-professional team members in an ICU setting

M N NtingaI; H van AswegenII

IMSc; OrcID 0000-0002-9725-9312; Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIPhD; OrcID 0000-0003-1926-4690 ; Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. In the intensive care unit (ICU) environment, inter-professional team collaborations have direct impact on patient care outcomes.

Current evidence shows that providing physiotherapy to ICU patients shortens their length of stay and reduces their incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia and severity of critical illness neuropathy. Physiotherapists' perceptions of their interactions with nurses and doctors as inter-professional team members in the ICU is important.

OBJECTIVES. To identify barriers and enablers of physiotherapists' interactions with inter-professional team members in adult ICU settings, identify solutions to the barriers and determine if perceptions of interactions with ICU team members differ between junior and senior physiotherapists.

METHODS. A qualitative study was done using semi-structured group discussions. Participants were recruited using convenience sampling. Participants were junior and senior physiotherapists from four private and four public sector hospitals in urban Johannesburg, South Africa. Interviews were audio recorded. Recordings were transcribed and direct content analysis of data was done to create categories, subcategories and themes.

RESULTS. Twenty-two junior and 17 senior ICU physiotherapists participated in the study. Barriers raised by physiotherapists regarding communication with inter-professional team members in the ICU were non-ICU trained staff working in ICU, personality types, lack of professional etiquette, and frequent rotation of ICU staff. Enablers of communication with inter-professional team members were presence of team members in ICU during the day, good time management, teamwork approach to care and sharing of knowledge. Differing paradigms of teamwork among health professionals was highlighted as a cause of tension in the ICU inter-professional collaborations.

CONCLUSION. Physiotherapists are important members of the inter-professional ICU team. Exploring their interactions with other team members identified solutions that may improve collaboration between inter-professional team members to facilitate improved patient outcomes. Inter-professional education should inform ICU policies to create an environment that fosters teamwork. Finding creative ways to adequately staff the ICU without losing quality or driving up costs of care are matters that should take priority among policy makers.

Keywords: critical care; physiotherapy; communication; inter-professional teams; perceptions; patient care.

The intensive care unit (ICU) is an ideal environment for interprofessional collaborations to take place, because of the high turnover of critically ill patients, new technological advances and being a specialised area of healthcare.[1] Inter-professional team collaboration allows enhanced patient safety, better use of resources by avoiding duplication of treatment and improved standards of patient care as the time and skills of the professionals are efficiently utilised.[2 Nurses spend the most time with ICU patients during their 12-hour shifts and are the major communicators in the inter-professional ICU team. They are responsible for relaying messages between different team members and facilitating communication between patients and their family members.[3] Physiotherapists are integral members of the inter-professional team that care for critically ill patients. Moderate-to-high quality evidence exists to show that physiotherapy-driven interventions such as early mobilisation of ICU patients, application of exercise therapy, respiratory therapy techniques, and their involvement with patient weaning and extubation from mechanical ventilation (MV) is associated with reduced rates of ventilator-acquired pneumonia, duration of MV, length of stay (LOS) in the hospital, improved respiratory and peripheral muscle strength, patient participation in activities of daily living and functional activities, and improved exercise capacity at hospital discharge[4,5,6] Teamwork between ICU staff is essential to ensure that patients reap the benefits of out-of-bed mobilisation, inter-professional team-driven weaning protocols to enhance their liberation from MV and other rehabilitation interventions[6,7-]

Limiting hierarchical structures in patient care is important to empower the respective inter-professional team members to use their clinical reasoning skills and have the confidence to carry out their autonomy in patient care.[8] The TEAM study showed that acquiring skills in team building and continuing professional development (CPD) improved teamwork dynamics in the ICU.[9] The presence of nursing leaders in an ICU setting who address matters of staff motivation, education, skills building, team building and play a role in facilitating interactive supervision, improved inter-professional teamwork dynamics.[10,11]

Healthcare facilities that employ highly qualified healthcare professionals report improved patient outcomes and positive patient feedback of their hospital stay.[12] In neonatal ICU care, communication failures among inter-professional team members as opposed to individual errors accounted for up to 72% of causes of perinatal death and injury.[13] Patients in ICU are critically ill and require differing levels of care and expertise in their management. There is a high turnover of nursing staff working in ICU as many feel that they are unable to cope with patient demands or that they are inadequately trained for effective management of critically ill patients.[14] It was highlighted that when a written common goal-orientated tool sheet was used during ICU ward rounds to document and illustrate information of patient treatment goals and patient response to treatment, cohesion and collaboration among health professionals in ICU was greatly improved.[15]

Exploration of dynamics within the inter-professional ICU team is important to identify enablers and barriers that may impact interaction of physiotherapists with the team. Interventions to address barriers can be developed and tested to enhance relations between inter-professional ICU team members to optimise patient care.[14-16] There are currently no reports available in South Africa that explore collaboration, interactions and communication between physiotherapists and other interprofessional ICU team members. This study was conducted to establish physiotherapists' perceptions of interactions with the inter-professional team members in private- and public-sector adult ICU settings.

Methods Study Design

A qualitative study design was carried out using semi-structured group discussions which were facilitated by stimulus questions. Discussions were audio-recorded.

Participants

The study population consisted of junior and senior physiotherapists who worked in adult ICU settings in Johannesburg. Junior physiotherapists who had been working in an adult ICU setting for 1 - 5 years were approached for possible participation. Senior physiotherapists who had daily working experience in an adult ICU for 5 years or longer were approached for participation.

A convenience sampling method was used to recruit participants for this study. Interviews were held with physiotherapists from 4 public sector and 4 private sector hospitals.

Procedure

Permission to conduct this study was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics (Medical) committee (ref. no. M140345). Physiotherapy private practice owners (whose practices serve adult ICUs in private hospitals) and heads of department of public sector hospitals (with adult ICUs) in Johannesburg were contacted and provided with information about the study purpose and aims. Junior and senior physiotherapists who agreed to participate were provided with dates and times that were convenient for their 1-hour semi-structured group discussion session. Group discussion sessions were held at a venue convenient for the participants. The participants were split into 13 groups. Senior and junior participants were interviewed separately. Each semi-structured group discussion session commenced with a brief introduction and explanation of the procedure, rules and what was expected from the participants. This was accompanied by distribution of the study information sheet, consent forms, and demographic and clinical information sheets which were completed by participants prior to initiation of the interview and discussions.

Thirteen semi-structured group discussion sessions were conducted in July and August 2014. Information was obtained by posing stimulus questions to each group. Handwritten notes were made during each group discussion session while the discussions were being recorded (Olympus VN-5500PC digital voice recorder; Olympus, USA). The recordings added to the credibility, applicability and transferability of the data collected. No participants declined audio recording. Data saturation occurred when all participants completed their group discussion sessions and no new information was forthcoming.

The recorded discussions were transcribed verbatim into written transcripts for data analysis. Data cleaning was done by listening to the tape recordings while reading the transcribed notes. After transcription, cross-referencing between recorded and written notes for each semi-structured group discussion session was done to ensure accuracy of data obtained. The transcribed notes were sent to some of the participants for verification of its correctness. A directed content analysis approach was used to present the information obtained. This was done using an inductive approach because it was concerned with the generation of new theory emerging from the qualitative data, e.g. themes and codes which were generated by the stimulus questions. Trustworthiness of information obtained was ensured through adherence to strategies such as credibility (including member checking), transferability, dependability and confirmability.

Quantitative data obtained were summarised using descriptive statistics. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 24 (IBM Corp., USA) Continuous variables (age and years worked in ICU) were summarised as mean, minimum and maximum, and standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between junior and senior physiotherapists for age and years worked in ICU were made using an independent f-test. Categorical variables (e.g. gender, healthcare sector, etc.) were summarised as numbers and percentages.

Results

A total number of 39 physiotherapists participated in the semi-structured group discussions. The characteristics and working environment of the participants are summarised in Table 1. The mean (standard deviation (SD)) age of the total participants was 30.7 (8.73) years. The majority of participants were female (92.3%; n=36). Participants worked in more than one ICU at a time when the semi-structured group discussions sessions were held. There was an expected significant difference in age and ICU working experience between junior and senior participants. Most of the junior participants worked in the public healthcare sector. There was an equal distribution of senior participants in public and private sectors. Some participants had other qualifications that included a diploma in HIV medicine (n=1), diploma in animal sciences (n=1) and diploma in equestrian anatomy (n=1).

Physiotherapists as members of the interprofessional ICU team

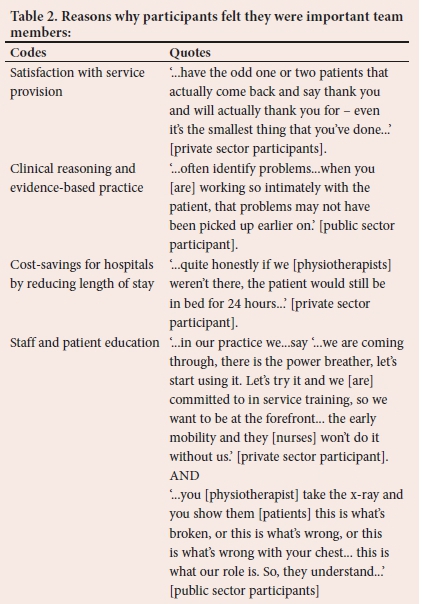

All participants viewed themselves as an important part of the ICU inter-professional team. They felt that they provided an essential service to patients in ICU. The reasons why participants felt they were important team members are summarised in Table 2. This perception was substantiated by the level of satisfaction that nurses and patients expressed towards physiotherapy involvement with patient care.

Physiotherapists' perceptions of interactions with inter-professional team members in ICU

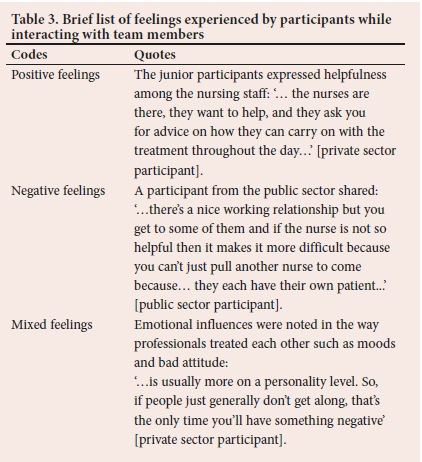

The inter-professional team members most reported on were nurses and doctors. Participants shared their feelings about their perceptions of interactions with inter-professional team members and several participants expressed that their attitudes depended on the professional they were interacting with (Table 3).

Factors that influence communication with inter-professional team members in ICU

Participants shared that several factors influenced their communication with other inter-professional ICU team members (Table 4).

Factors that affect patient care in ICU

A factor that enabled quality patient care in ICU was identified as having open lines of communication within the inter-professional team, and barriers were medical hierarchy and not having regular access to other healthcare professionals (Table 5).

Solutions to identified barriers:

Participants suggested several solutions to the perceived barriers encountered with inter-professional team members working in ICU (Table 6).

The differences in responses between junior and senior participants showed that hierarchy and the lack of familiarity with team members, lack of knowledge of ICU equipment and ICU policies weighed heavily on the junior participants while the senior participants valued avoiding errors by mitigating fatigue, reducing high staff turnover, and opening lines of communication between team members.

Discussion

Information obtained through the semi-structured group interviews revealed that physiotherapists felt valued as part of the inter-professional team that works in ICU. They raised several enablers and barriers that they experience in relation to communication among the interprofessional team members, which have an impact on the quality of patient care provided in this setting. Important barriers highlighted included lack of orientation programmes for new staff joining the ICU team and overworked healthcare professionals who are responsible for many patients, which may result in misdiagnosis and management errors. Some participants shared ideas to resolve identified barriers to enable better working relations among team members and to optimise patients' responses to care and their clinical outcomes.

There is evidence that young female healthcare professionals employed in ICU are chronically fatigued, frustrated and emotionally disengaged compared with other healthcare professionals due to high workload, poor sense of community, poor remuneration and little control over their work structure.[11,18] Job satisfaction studies reported that when nursing leaders are present in the ICU and address matters of staff motivation, remuneration, education, skills/team building and play a role in facilitating interactive supervision, it improved the interprofessional teamwork dynamic.[19] The frequent rotation of staff in and out of ICU cannot be curbed owing to remuneration deficits in the SA work sector and a rising demand for ICU beds. The implementation of strict ICU orientation policies and mentorship programmes for junior staff by pairing them with experienced and qualified critical care health professionals who will mentor, advise, guide and support them throughout their rotation in the ICU, could improve work dynamics among the inter-professional team members. Moreover, staff should be required to attend CPD courses specific to their professional role in an ICU setting. This would ensure a high standard of continuity of patient care in the ICUs.

Non-ICU-trained staff working in the ICU was raised as a barrier to inter-professional teamwork. Electronic ICU (e-ICUs/TELE-ICUs) has been suggested as a solution for addressing the lack of ICU-trained healthcare professionals in developed countries. These e-ICUs are a form of telemedicine, where healthcare professionals can access the ICUs remotely, provide expert care and advise to ICU practitioners while accessing patient information offsite and providing mentoring to less experienced or qualified healthcare professionals.[20] Currently, this is not an option to ICU healthcare professionals in SA where virtual ICU centres would take away the physical presence of skilled staff, intensivists and resources from the severely ill patient's bedside.[21] These e-ICUs exist in the USA and help curb the shortage of skilled professionals by providing live skill support to ICU personnel in remote areas.

Findings from interviews conducted with junior participants revealed issues related to conflicts due to staff hierarchy and being heard and valued in the ICU. Traditional hierarchy of staff in an ICU setting was a common challenge for junior participants. Research has shown that when professionals high up in the hierarchy such as physicians engage in active listening and encourage other professionals to share their ideas, inter-professional communication among team members improved dramatically.[22] The use of communication checklists and tools is recommended because these tools reduce errors and omissions of critical and relevant patient-related information during patient handover.[23-

Both junior and senior participants agreed that there are differing views of what is 'teamwork' among the different healthcare professions. Evidence shows that teamwork can be enhanced between inter-professional team members by using inter-professional education training programmes where undergraduate students are trained through simulation of patient cases to collaboratively assess, treat and problem solve.[24

One of the limitations of the present study was that it was conducted in an urban setting. The perception of physiotherapists working in ICUs in low-population, semi-urban areas may be different from those working in overloaded and demanding environments. There is a possibility that researchers may have allowed their prior experiences working as physiotherapists in the ICU to influence the interviewing process to focus on aspects that personally resonated with them. Olson[24] felt that it could be difficult for the interviewer to step back and be objective. The study focused on the physiotherapists' perceptions of inter-professional team members which are based on events that may have occurred months before the interviews took place and may have been distorted. Direct observation of inter-professional team members interacting with physiotherapists would corroborate the findings of this study. Future studies could explore other members of the inter-professional ICU team's perceptions of interactions with physiotherapists. This could assist in the identification of key factors that influence the inter-professional team interactions in ICU, and solutions to barriers to inter-professional team collaboration can be developed.

Conclusion

Physiotherapists are key role players in ICU early mobilisation and prevention of physical fitness decline post critical illness, and exploring their interactions with other team members has identified solutions that may improve collaboration among inter-professional team members. Being able to communicate with an ICU patient is equally as important as being able to communicate with other professionals in the ICU setting. CPD was identified as a possible solution to improve relational barriers and facilitate communication, professionalism, friendliness and respect among inter-professional team members in the ICU.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. The authors would like to thank all the participants for availing themselves to participate in this study.

Author contributions. MNN and HvA conceptualised the study, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. Both authors approved the manuscript for publication.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Yeole UL, Chand AR, Nandi BB, Gawali PP, Adkitte RG. Physiotherapy practices in intensive care units across Maharashtra. Indian J Crit Care Med 2015;19(11):669-673. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-5229.16934 [ Links ]

2. Stollings JL, Devlin JW, Pun BT, et al. Implementing the ABCDEF bundle: Top 8 questions asked during the ICU liberation ABCDEF bundle improvement collaborative. Crit Care Nurse 2019;39(1):36-45. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2019981 [ Links ]

3. Costa DK, White MR, Ginier E, et al. Identifying barriers to delivering the awakening and breathing coordination, delirium, and early exercise/mobility bundle to minimise adverse outcomes for mechanically ventilated patients. Chest 2017;152(2):304-311.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.054 [ Links ]

4. Stiller K. Physiotherapy in intensive care. Chest 2013;144(3):825-847. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-2930 [ Links ]

5. Lord RK, Mayhew CR, Korupolu R, et al. ICU early physical rehabilitation programs. Crit Care Med 2013;41(3):717-724. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0b013e3182711de2 [ Links ]

6. Plani N, Becker P, van Aswegen H. The use of a weaning and extubation protocol to facilitate effective weaning and extubation from mechanical ventilation in patients suffering from traumatic injuries: A non-randomised experimental trial comparing a prospective to retrospective cohort. Physio Theory Prac 2012;29(3):211-221. [ Links ]

7. Hickmann CE, Castanares-Zapatero D, Bialais E, et al. Teamwork enables high level of early mobilisation in critically ill patients. Ann Intens Care 2016;6(1).80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-016-0184-y [ Links ]

8. Paganini MC, Bousso RS. Nurses' autonomy in end-of-life situations in intensive care units. Nursing Ethics 2014;22(7):803-814. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014547970 [ Links ]

9. The TEAM study Investigators. Early mobilisation and recovery in mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU: A bi-national, multi-centre, prospective cohort study. Critical Care 2015;19(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-0765-4 [ Links ]

10. O'Neill CS, Yaqoob M, Faraj S, O'Neill CL. Nurses' care practices at the end of life in intensive care units in Bahrain. Nurs Ethics 2016;22;24(8):950-961. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733016629771 [ Links ]

11. McAndrew NS, Leske JS. A balancing act. Clin Nurs Res 2014;25;24(4):357-374. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773814533791 [ Links ]

12. Thomas P, Paratz J, Lipman J. Seated and semi-recumbent positioning of the ventilated intensive care patient - effect on gas exchange, respiratory mechanics and hemodynamics. Heart Lung 2014;43(2):105-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.11.011 [ Links ]

13. Coscia A, Bertino E, Tonetto P, et al. Communicative strategies in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Matern Fetal Neon Med 2010;23(3):11-23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-017-0308-8 [ Links ]

14. Ersson A, Beckman A, Jarl J, Borell J. Effects of a multifaceted intervention QI program to improve ICU performance BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:838. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3648-y [ Links ]

15. Centofanti JE, Duan EH, Hoad NC, et al. Use of a daily goals checklist for morning ICU rounds: A mixed-methods study. J Crit Care Med 2014;42:1797-1803 https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000331 [ Links ]

16. Gupte P, Swaminathan N. Nurse's perceptions of physiotherapists in critical care team: Report of a qualitative study. Indian J Crit Care Med 2016;20:141-145. https://doi.org/10.4103%2F0972-5229.178176 [ Links ]

17. Moss M, Nordon-Craft A, Malone D, et al. A randomised trial of an intensive physical therapy program for patients with acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;193(10):1101-1110. https://doi.org/10.1164%2Frccm.201505-1039oc [ Links ]

18. Shoorideh FA, Ashktorab T, Yaghmaei F, Alavi Majd H. Relationship between ICU nurses' moral distress with burnout and anticipated turnover. Nurs Ethics 2015;22(1):64-76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014534874 [ Links ]

19. Fiabane E, Giorgi I, Sguazzin C, et al. Work engagement and occupational stress in nurses and other healthcare workers: The role of organisational and personal factors. J Clin Nurs 2013;22(17-18):2614-2624. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12084. [ Links ]

20. Assimacopoulos, A, Alam, R, Arbo, M, et al. A brief retrospective review of medical records comparing outcomes for in-patients treated via telehealth versus in-person protocols: Is telehealth equally effective as in-person visits for treating neutropenic fever, bacterial pneumonia, and infected bacterial wounds. Telemed J E-Health 2008;14:762-768. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2007.0128. [ Links ]

21. Nesher L, Jotkowitz A, Ethical issues in the development of tele-ICUs. J Med Ethics 2010;11(37):655-657. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2010.040311 [ Links ]

22. Laerkner E, Egerod I, Hansen HP. Nurses' experiences of caring for critically ill, non-sedated, mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: A qualitative study. Intens Crit Care Nurs 2015;31:196-204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2015.01.005 [ Links ]

23. De Meester K, Verspuy M, Monsieurs KG, et al. SBAR improves nurse-physician communication and reduces unexpected death: A pre and post intervention study. Resusc 2013;84(9):1192-1196. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.resuscitation.2013.03.016 [ Links ]

24. Olson R, Bialocerkowski A. Interprofessional education in allied health: A systematic review. Med Edu 2014:48:236-246 https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12290 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

M NNtinga

nomusa.ntinga@uct.ac.za

Accepted 26 August 2020

Contribution of the study. Physiotherapists are essential and strategically placed in the ICU to reduce length of stay, and prevent patient physical function decline post ICU admission. This work explored physiotherapists' perceptions of collaboration within inter-professional teams in the ICU and identified barriers that impede communication in inter-professional teams and suggested solutions. This research will contribute in improving collaboration between inter-professional teams in the ICU setting.