Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Southern African Journal of Critical Care (Online)

On-line version ISSN 2078-676X

Print version ISSN 1562-8264

South. Afr. j. crit. care (Online) vol.30 n.1 Pretoria Aug. 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJCC.162

ARTICLE

The needs of patient family members in the intensive care unit in Kigali, Rwanda

P MunyiginyaI; P BrysiewiczII

IRN; Faculty of Nursing Sciences, Kigali Health Institute, Rwanda

IIPhD; School of Nursing and Public Health, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The admission of a relative to an intensive care unit (ICU) is a stressful experience for family members. There has been limited research addressing this issue in Kigali, Rwanda.

OBJECTIVE: To explore the needs of patient family members admitted into an ICU in Kigali, Rwanda.

METHODS: This study used a quantitative exploratory design focused on exploring the needs of patient family members in ICU at one hospital in Kigali, Rwanda. Family members (N=40) were recruited using the convenience sampling strategy. The Critical Care Family Needs Inventory was used to collect relevant data.

RESULTS: The participants identified various needs to be met for the family during the patient's admission in ICU. The most important was the need for assurance, followed by the need for comfort, information, proximity and lastly support. Three additional needs specific to this sample group were also identified, related to resource constraints present in the hospital where the study was carried out.

CONCLUSION: These results offer insight for nurses and other healthcare professionals as to what the important needs are that must be considered for the patient family members in ICUs within a resource-constrained environment.

The admission of a loved one into an intensive care unit (ICU) and the technology used therein, coupled with high morbidity and mortality rates in an ICU setting, lead family members to experience feelings of stress, anxiety, uncertainty and surrealism. These feelings are compounded by the fact that most families lack experience with such events. Traditionally, family members have been excluded from the ICU, but current perspectives in ICU management encourage a shift from patient-focused nursing care to holistic care. This approach to nursing includes identifying and meeting the needs of family members in order to reduce anxiety and prevent stress in patients and their family.[1]

For the Rwandan, as in many cultures, illness is a family affair, and it is believed that enquiring about another's health and expressing sympathy for the sick are important aspects of social interaction. People make an effort to visit the sick to show support and to wish them better health. It is usually appreciated if prepared food or drink is brought with when visiting sick friends.[2] Any barrier to these practices may create disequilibrium within the family members of a critically ill patient.

The current situation in Rwanda is that rules and regulations on family visitation are very restrictive and family members are often not included as part of the healthcare team. As most nurses in ICUs are not specifically trained in supporting patients' families, they often do not communicate with the family members in ways that they can easily understand.[3]

Nurses, as well as other health professionals, need to learn the perceived needs of family members in order to meet them. Thus, Molter[4] developed a list of 45 need statements of family members whose relatives had been admitted into an ICU. Leske[5] later added an open-ended question to this tool and developed the Critical Care Family Needs Inventory (CCFNI).[6] The purpose of this tool is to rank and evaluate family members' perceived needs. Family member needs may vary according to diverse factors such as demographics, culture, past experience and the environment[6] and it is with this in mind that an attempt to explore the needs of patient family members in a specific ICU in Rwanda was carried out.

Objective

The objective of this study was to explore the needs of Rwandan patient family members admitted into an ICU. The following research questions guided the study:

• What are the needs of patient family members admitted to ICU?

• What is the level of importance of these needs according to the family members?

Methods

This study used a quantitative exploratory design explore the needs of patient family members admitted to an ICU. The study site was a teaching hospital in Kigali Province, Rwanda. The ICU of this hospital is a medical-surgical unit with eight beds, receiving both adult and paediatric patients. There are only three other ICUs in Rwanda. The ICU is equipped with ventilators and continuous monitoring devices to manage patients from Kigali or other hospitals in the country, who present with life-threatening conditions. The study population included all patient family members (adult and paediatric patients) admitted into this ICU during the period of data collection (July to August, 2011). Convenience sampling was used to access the most readily available persons as participants in the study. During the study period, the average rate of patient admission into ICU was 23 patients per month and, in consultation with a statistician, a sample size of 40 family members was recruited to participate in the study.

One family member per patient was included in the study, chosen on the basis of being a blood relative or a significant other who regularly visited the patient in the ICU. The family member had to be at least 18 years of age, be able to read Kinyarwanda or English and have a family member who had been admitted to the ICU for at least 24 hours.

The researcher approached potential participants in the waiting room of the ICU to explain the study. After they agreed to participate, they were escorted to a private, quiet room to complete the questionnaire.

The self-administered data collection tool used was the CCFNI,[4,5] which consisted of two parts: (i) addressing demographic data; and (ii) dealing with 45 needs of family members of critically ill patients admitted into an ICU.[4,5] Participants were requested to rank their needs according to their level of importance on a four-point Likert-type scale as: not important (1), slightly important (2), important (3) and very important (4). An additional open-ended question was added to allow participants to add any other perceived needs not listed on the CCFNI. The internal psychometric properties of the CCFNI had been evaluated previously, including internal consistency (α=0.92), reliability and construct validity, and warranted the continued use of the tool in this research.[4,5] To ensure the reliability and validity of this tool in the study population, a pilot study was carried out 1 week before the final study. The pilot study demonstrated that the statements of the questionnaire were correctly understood by participants, culturally relevant and appropriate.

After seeking permission from the author of the CCFNI, the tool was translated from English to Kinyarwanda by a language expert and then retranslated into English to ensure the accuracy of the translation.[4,5] Ethical approval was obtained from the Kigali Health Institute research committee and the hospital research committee. The objective of the research was explained to participants, and informed consent was obtained from each participant. Principles of anonymity and confidentiality were observed. The researcher was available to respond to any questions and assist with the questionnaire if needed, as well as to monitor any possible emotional distress in the family members.

Data were entered and analysed using SPSS version 16.0. Statistical analysis was performed using descriptive analysis techniques.

Results

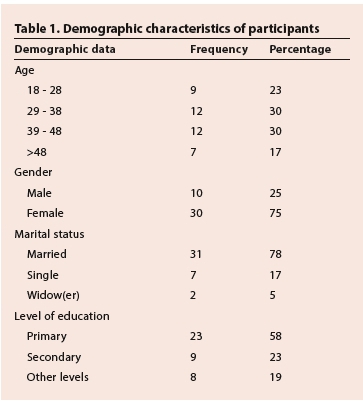

Forty participants were initially approached and all consented to participate in the study. Their demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Demographic data

The majority of participants were female, representing 75% (n=30) of the sample. Among the participants 78% (n=31) were married, and level of education varied from primary education (57%, n=23) to secondary level (23%, n=9) (Table 1).

Overall needs of participants

The second part of the tool was divided into five subscales (assurance, comfort, information, proximity and support), which dealt with the 45 needs of family members. Participants were asked to use a four-point Likert-type scale with the following ratings: not important (1); slightly important (2); important (3); and very important (4).

Within these, the highest mean score for the subscales was the need for assurance (3.17), followed by the need for comfort (3.11), information (3.08), proximity (3.00), and lastly, support (2.64).

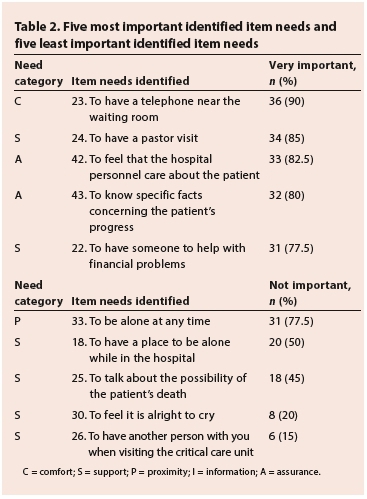

Table 2 presents the five needs identified as most important, as well as the five needs participants considered as not being important.

Need of assurance

In this study, 70% (n=28) of the participants expressed that the need to have questions answered honestly was very important to them. The findings revealed that 68% (n=27) of the participants rated the need to feel that there was hope as being very important, with none reporting this need as not important or slightly important. Results also showed that 80% (n=32) perceived the need to know specific facts concerning the patient's progress as very important.

Need for comfort

Of the participants, 90% (n=36) ranked the need to have a telephone near the waiting room as very important and 78% (n=31) indicated that it was very important to have the waiting room near to the ICU. Another very important need mentioned by 48% (n=19) of participants was having comfortable furniture in the waiting room.

Need for information

A majority (73%, n=29) of the family members perceived the need to know exactly what was being done for the patient as being a very important need and 62% (n=25) ranked the need of knowing how the patient was being treated medically as very important. The need to know why things were being done for the patient was ranked as very important by 60% (n=24) and 35% (n=14) felt that it was important to know the type of staff members who were taking care of the patient. Results showed that 50% (n=20) of the participants perceived the need to know the expected outcome as being important, while 48% (n=19) indicated that this was a very important need.

Need for proximity

Results showed that 53% (n=21) of the participants perceived that it was very important to have flexible visiting hours and 35% (n=14) that it was important that they could visit at any time. Of the participants, 70% (n=28) indicated it was important that they should be contacted at home if there were any changes in the patient's condition.

Need for support

Most participants (95%, n=38) indicated that it was important to have the ICU environment explained if it was a family member's first experience in ICU and 55% (n=22) suggested that it was important to have visits starting on time. Of the participants, 78% (n=31) indicated it was important to have someone to help with financial problems and 85% (n=34) indicated the need for having a pastor available.

Responses to the open-ended question

Results from the open-ended questions showed that four participants wanted the hospital to have more resources for the patient, for example medication, so that the family members did not have to go outside the hospital to search for the prescribed medication. More space in the ICU to accommodate family members during visits was another need identified, as was a dedicated space near the ICU where family members could eat while waiting for news of their loved one.

Discussion

Rwanda is a small land-locked country with an estimated population of approximately 11 million. The Rwandan population is young, with 42.5% of the total population under the age of 15 years. Population growth is estimated at a rate of 2.6% annually. Although much has been done in all sectors to improve the quality of life after the genocide of 1994, over 60% of the population live in poverty.[7]

Results from this study showed that many of the participants were young, married females who were not very well educated. This can be attributed to the fact that in Rwanda, females are traditionally viewed as the primary caregivers in the family and the literacy rate in the country is still low. Some participants had to travel a long distance from their homes to reach the ICU where their relative had been admitted because there are still very few ICUs in the country.

The subscale for assurance was ranked the highest in this current study; assurance for family members enables them to cope with the crisis situation they encounter when a loved one is in a critical condition. Within the top five item needs identified by participants were the need to be assured that the hospital personnel care about the patient and the need to know specific facts concerning the patient's progress. This echoes results from other researchers[4,8,9] who revealed that family members may ask a lot of questions to get to know the nurse and the unit in order to be assured that their relatives are receiving the best possible care.

Participants ranked the subscale need of comfort in second place, which was similar to a study done in Jordan.[9] In the current study, the needs that were identified cannot be regarded as comfort as such, but rather as those that allow families the means to sustain themselves during the period of their relative's stay in ICU. Being in an uncomfortable place for any length of time can cause considerable strain. A comfortable waiting room and various other things that are done to make the wait easier for families all convey a message of concern for their wellbeing.[10]

The need for information was ranked as the third most important subscale by participants, similar to many previous studies.[4,9]. Researchers have reported that the value of compassion and effective communication are two important aspects for family adjustment regardless of patient outcome.[11] Educating families about a loved one's illness, treatment and physical status helps to prepare them for what they will encounter when they visit the patient.[11]

Family members expressed the need to be close to their relatives on a regular basis, even to the extent of being allowed to visit them at any time. Participants identified that visiting hours should be flexible, staff should be able to make allowances for special conditions, and that it was important that they should be called at home if there were any changes in the patient's condition. In the Rwandan context, as in other cultures, illness is a family affair and social interaction obliges family members to visit sick relatives to express sympathy and to wish them better health.[13]

The additional family needs not mentioned in CCFNI but expressed by participants in this study can be related to the resource constraints present in the hospital where the study was carried out. In the researcher's experience, when a family member has accompanied their loved one to the ICU, they feel unable to return home and leave him or her alone in the ICU. Consequently the family member often sits outside the ICU unit on benches. This is also because family members are usually required by ICU personnel to sign consent forms and perform other activities such as pay hospital bills, and buy food and medications, especially when these are in short supply.

The need for support was ranked as the least important subscale by participants, which is comparable to the findings of a study conducted in Thailand.[14] This may be due to the fact that family members consider the patient's health problems as most significant and this lessens their own needs. An interesting finding in the current study was that despite the overall low subscale mean score for support, two individual items within this subscale were among the top five most important item needs identified by family members, namely to have a pastor visit and to have someone help with financial problems; this is reflective of the current situation in Rwanda, where the healthcare system typically requires payment prior to service. As many of the population are poor, this can induce anxiety for family members needing to allocate resources for the care of their loved one. The majority of Rwandans are Christian[7] and pastors, therefore, represent spiritual support and are seen as very important figures during times of high anxiety or uncertainty.

Study limitations

Due to the characteristics of convenience sampling, caution should be taken when generalising the findings of this study. This study was carried out in one hospital in Kigali, Rwanda, using a small sample, thus cannot be classified as representative of the population. Differences between the needs of family members of adult and paediatric patients in ICU were not considered in this study.

Conclusion

Family members who participated in this research ranked the need for assurance in first position, followed by the need for comfort. The need for support was ranked last.

For nursing practice in ICU in Rwanda, it is important for the nurses to be aware of the needs of family members. They need to recognise fully that their needs ultimately require a shift in how healthcare settings organise patient care.

Recommendations

It is suggested that a duplication of this study in other ICUs in Rwanda be completed to investigate the perceived needs of family members in different settings as well as in different groups, and that needs met and unmet are explored. The needs of family members should be incorporated into the curriculum of nurses at all levels of nursing education in Rwanda, particularly registered nurses, as it is they who work in the ICUs. In-service training could also be valuable and beneficial to both nurses and family members to highlight these needs.

References

1. Maxwell KE, Stuenkel D, Saylor C. Needs of family members of critically ill patients: A comparison of nurse and family member perceptions. Heart Lung 2007;36(5):367-376. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2007.02.005] [ Links ]

2. Yang SA. A mixed methods study on needs of Korean families in intensive care unit. Aust J Adv Nurs 2008;25(4):79-86. [ Links ]

3. Chang MK, Harden JT. Meeting the challenge of the new millennium: Caring for culturally diverse patients. Urol Nurs 2002;22(6):372-377. [ Links ]

4. Molter NC. Needs of relatives of critically ill patients: A descriptive study. Heart Lung 1979;8(2):332-339. [ Links ]

5. Leske JS. Internal Psychometric properties of Critical Care Family Needs Inventory. Heart Lung 1991;20(3):236-244. [ Links ]

6. Leske JS. Needs of relatives of critically ill patients: A follow-up. Heart Lung 1986;15(2):189-193. [ Links ]

7. Institut National de la Statistique du Rwanda (INSR) et ORC Macro. Enquête Démographique et de Santé Rwanda, 2010. Calverton, USA: INSR et ORC Macro, 2010. [ Links ]

8. Fry S, Warren AN. Perceived needs of critical care family members: A phenomenological discourse. Crit Care Nurs 2007;30(2):181-188. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.CNQ.0000264261.28618.29] [ Links ]

9. Omari FH. Perceived and unmet needs of adult Jordanian patient family members in ICUs. J Nurs Scholarsh 2009;41(1):28-34. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01248.x] [ Links ]

10. FitzpatrickE, Hinkle J, Oskrochi RG. Identifying the perception of needs of family members visiting and nurses working in the intensive care unit. J Neurosci Nurs 2009;41(2):85-91. [ Links ]

11. Wyckoff MM, Houghton D, Lepage CT. Critical Care: Concepts, Role and Practice for the Acute Care Nurse Practitioner. New York, USA: Springer Publish Company, 2009. [ Links ]

12. Leske JS. Family responses to critical care of the older adult. In Marquis D, Foreman KM, Terry TF. Critical Care Nursing of Older Adults: Best Practices. 3rd ed. New York: Springer Publishing Company, 2010:117-150. [ Links ]

13. Ndabavunye I. De la pertinence durite de passage dans la reconstruction du lien social au Rwanda. Thérapie Familiale 2005;26:103-123. [ Links ]

14. Reynold J, Prakinkit S. Needs offamily members of critically ill patients in cardiac care unit: A comparison of nurses and family perceptions in Thailand. Journal of Health Education 2008;31(110):54-66. [ Links ]

Correspondence: P Brysiewicz (brysiewiczp@ukzn.ac.za)