Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Phronimon

versão On-line ISSN 2413-3086

versão impressa ISSN 1561-4018

Phronimon vol.23 no.1 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/2413-3086/11479

ARTICLE

'Conversational Decoloniality': Re-Imagining Viable Guidelines for African Decolonial Agenda

Akinpelu A. Oyekunle

University of South Africa Eoyekuaa@unisa.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1697-7233

ABSTRACT

This article identifies the agenda of decoloniality as a call to seek solutions to Africa's problems from within herself (Africa). This call has its hold in colonial and post-independent attempts by African Nationalists, writers, freedom fighters and philosophers to defend Africa's cultural heritages, even against its underestimation by scholars of other climes of the world. It further argues that, though justice done to this quest would afford Africa to regain her existential humanism in a global setting, the defence of African cultural heritages has not yielded much-desired efforts due largely to methodological error. This article observed that African scholars often, in the attempt to free their intellectual outputs from European ethnocentric postulations, overbears the indigenous idea in the decolonial projects. This error is noted to be a consequence of the tendency to deify African worldviews and thought processes. Employing the conversational method of philosophising Chimakonam (2015, 2017a, 2017b, and 2018), this article attempts to interrogate the agenda for decolonisation and re-Africanisation. It argues for the idea of conversational decolonisation. This article concludes that a conversational decolonised process would, among other things, be appropriate for a scholarly response to colonial denigrations and underestimations of African cultures and traditions. It would also be a framework for achieving African self-definition in the modern world without compromising African identity.

Keywords: Africa, coloniality mentality, decolonial agenda, conversational thinking, conversational decoloniality.

Introduction

The decolonial agenda is taken here as a practical, theoretical, and ideological effort in the quest for a solution to existential challenges of the colonised from their indigenous thought processes. The decolonial agenda has its hold in colonial, post-independent, and contemporary attempts by African Nationalists, writers, freedom fighters and philosophers to push for "epistemic emancipation" (Lenkabula 2021) of Africa, even in the consideration of the inevitable Global South-North relationships. The quest for decolonisation thus becomes essential and significant to the growth and sustainability of development in the independent contemporary states. This is because decolonisation is the intellectual framework for raising questions and reconstructing the stance of self-determination, economic liberation, epistemic justice, spirituality, selfhood, de-patriachisation, development, and the entire existential reality of the colonised, dominated, dismembered, destroyed, exploited, and dehumanised people-"the wretched of the earth" (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2020, 17-23).

Recognising various decolonial attempts, like (Cesaire 2000; Fanon 1968; Nkrumah 1965; Wiredu 1995; Kaya and Seleti 2014; Ngugi Wa Thiong'o 1986; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018; 2021; Amin, 2009; Ramose 2020; Rodney 2012) etc., this article argues for 'Conversational Decoloniality' (CD) through the appropriation of the conversational themes (Chimakonam 2018). CD is the idea of a decolonial project formed or carried out through the intellectual guidelines of Conversational Thinking (CT). CD will be argued for as a viable framework for African decolonial theory that is void of the most common errors of decoloniality. Many African scholars often, in the attempt to free their intellectual outputs from European ethnocentric postulations, commit two errors, among others, viz: concentration of the decolonial process on deconstructing Western episteme and deifying indigenous idea as sacrosanct in the project of decolonising African intellectual conceptual schemes. While the former inhibits the reconstructions of African indigenous knowledge systems for contemporary relevance, the later, undermines the decolonisation or re-Africanisation process. In other words, these two identified methodological errors inhibit the objective deconstruction of Eurocentric ideologies and forestalls systematic reconstruction of indigenous systems of knowledge. The aim of this article is to show the viability of CD as a dialectics of re-Africanisation that would best be an effective process in the pursuit of freedom and development for Africa without distorting AIKS.

To reach this conclusion, this article, divided into seven sections, commenced with an exploration of the African experience to encapsulate some of the African colonial, postcolonial, and contemporary realities. The next section: 'Colonial Mentality,' further invigorates the rationale for the decolonial agenda unveiled in the first section as it enunciates the corollary of the Western-centric system of intellectual subjugation of the colonised. This section raises the importance of arming the decolonial agenda with veritable tools that are structured on systematic thought process that align with the indigenous intellectual heritage of the colonised. In the subsequent section: 'Agenda of Decoloniality,' this article interrogates the decolonial agenda. Raising some criticism about some of the process of engagement in the quest for the decolonial agenda that has been terminated at the deconstruction of Western hegemonic ideas. The section enunciates the importance of reconstructionism in the decolonial process. Such premature termination of a process is a methodological error that is inhibiting the attainment of Africa's existential humanism in a global setting. At this point, this article will address the following crucial questions: why must the reconstructive orientation be of a critical nature? What viable guideline would be appropriate for a decolonial engagement based on a reconstructive critical stance? The article provides solutions in the successive sections titled 'Conversational Thinking' (CT) and 3R-UC themes of CT. The proposed solution describes CT as a real tool for rationalising concepts required to address existential concerns in Africa through the examination of CT's five themes. Thus, this article unveils CD-a decolonial agenda forms or engenders through the guidelines of CT-as a scholarly framework for achieving the decolonial goal.

The African Experience

The African colonial and post-independent realities were without many distinctions, as these realities differ only on the degree of praxis and not in form. The forms and systems of colonial political, economic, spiritual, and epistemological structures changes only in practice across the various colonies but persists in the degree of colonial control. As a matter of fact, the various independent African empires existing before the incursion of colonialism were no more than an administrative entity fashioned out as testament to the conquering quest of the various colonial powers. Before colonialism, Europe's contact with Africa was basically an economic affair (Ipadeola 2017, 146-47). However, as noted by (Falola 2002; Falola and Sanchez 2014; Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2018; and Ramose 2002), the need to sustain the development of capitalism especially through access to raw materials and an available ready market for finished goods necessitates the partitioning of the existing independent empires into colonies; and consequently, the political garb of colonial administration. This view however, does not overlook the epistemological foundation for colonialism which stands on the faulty, illogical reasoning that engenders the Eurocentric epistemic process1 (Oyekunle 2021, 170). The objective of the article here is to explore how the African colonial experience dovetails into the colonial mentality ravaging Africa till the contemporary time, and thus making the decolonial agenda imperative.

The African realities before and post-independence are entrenched on the conceptualisation of Africa as a place synonymous with poverty, slavery, lack of reason and in need of deliverance. A 2022 report, produced from an intensive research by the Royal African Society and Justice to History Centre in the United Kingdom for the AllParty Parliamentary Group, a group of Members of Both House of Commons and House of the Lords of the British Parliament notes that, Africa even in the contemporary time is understood, discussed and taught in the pedagogical system of Britain "only in terms of poverty and slavery and its relationship with the West, and very rarely in a positive way or in its own right" (Onwurah and Boateng 2022, 4). The implication of such line of reasoning, which holds credence to the Eurocentric epistemic process, is that even in the year 2022, Africa, and by extension non-Western world still possess the imagery of colonies that are not just primitive, esoteric, and exotic; but also, are in perpetual need of Western's support.

In the colonies, the colonisers' way of life was institutionalised as an inescapable life. It was possible to get the life, culture and lifestyles of the coloniser as a desideratum for the colonised because of the programme of systematic demystification of the colonised indigenous culture and life in its entirety. The colonisers brought and established a Western-centric educational process and authenticated the same as the only means of knowledge acquisition; as if knowledge creation, dissemination and appropriation were alien to the colonised. Furthermore, locals who pulled through this form of studies were made to receive an exalted position in the public and enjoy undue privileges in the society. This marks the start of a paradigm shift in the social order of the colonised's ecosystem.

As such, a development of a "new normal" was instituted into the colonies where power and success are associated with the supposedly ideal way of life of the colonial Master. Consequently, acquiring the Western knowledge forms becomes the measurement of intelligibility, smartness, political prowess, and an enviable status. This development created a wedge of gap in the social class of the colonised. While much of the effect of the class gap on the post-independent and contemporary African state will be discussed later in this article, it is worth noting that the situation created the foundation for class struggle and could be traced to being one of the major causes of the series of sociopolitical crises, civil war, and inter-ethnic/racial conflict ravaging Africa today. As noted by Abosede Ipadeola (2017, 148-49), a peculiar feature of the colonialist' policy is raising a particular nationality, from the colonised, to the status of a favoured group in terms of education, religion, and political positions. Hence, a greater populace of the colonised abhors the indigenous lifestyles and develops the mentality of taking or living the reality of the seeming utopia created by the colonialists as the telos of existence.

Colonial Mentality

A notable effect of the African experiences pre-and post-independence as enunciated in the preceding section of this article is the entrenchment of the Colonial Mentality (CM) among the colonised populace. CM is the systemic institutionalised feeling of inferiority within the indigenous people that are subjected to colonialism. Such institutionalised feeling is expressed with the notions that (i) colonial culture is intrinsically better, i.e., religion, education, clothing, social engagement and, (ii) narrative of development taken as essentially ideal i.e., politics, economics, security, etc. We shall investigate some instances of the notions of colonial mentality and the effects they have on contemporary African states, vis-à-vis how CM makes the agenda of decoloniality an imperative.

The notions of the superiority of the colonisers' culture are wired into the mentality of the colonised. At the inception of colonialism, the West came with two main tools of conquest or occupying the colonies: conquest by invasion and conquest by infiltration. The conquest by invasion through the brutal deployment of massive military strength, gadgets and forces, no doubt gave the colonialist upper hand in achieving its objective in the colonies. However, the sustainability of the colonial powers and continual control of the colonised is achieved through the deployment of the policy of conquest by infiltration. A host of scholars like (Chimakonam and Ogbonnaya, 2021; Ipadeola 2017, 146-49; Mpofu 2013, 98-113; Omanga 2020, 1-2; Rodney 2012, 148-51; and Zegeye and Vambe 2011, 46-49) to mention but a few, have highlighted the fact that colonialism was largely successful in the colonies by subtle and systematic destruction of indigenous epistemologies. As such, a system of mind colonisation was instituted by dismembering IKS through deconstructive criticism of the African mode of knowing as informal as well as the branding of the African religion system as fetish and barbaric (Oyekunle 2021). Capturing this system, Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni, in an interview with D. Omanga, noted that a system of conquest by infiltration is:

"A very complex power structure that transforms a people's way of life ... the invention of asymmetrical and colonial intersubjective relations between coloniser (citizen) and colonised (subject); and it economically institutes dispossession and transfer of economic resources from those who are indigenous to those who are conquering and foreign. It claims to be a civilising project, as it hides its sinister motives" (2020, 2-3).

As such, the system of colonialism is designed to infiltrate the "mental universe" (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2020, 118) of the colonised and distort their rational capability via different means, like "epistemicide"- the killing of indigenous knowledge and theft of history. (Santos 2014, 238), and "linguicides"- the killing of indigenous people's languages (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2018, 3). Reiterating the dual techniques of conquest, Chimakonam and Ogbonnaya (2021, 1-14) were of the view that the conquering of the colonies was successful through the creation and weaponisation of borders with which the colonised people were and are still being marginalised. I align with them that the marginalisation that creates a 'north-south divide' is a function of the weaponisation of the physical and intellectual borders; and also, that the intellectual border is more deadly to the colonised people than the physical border. This is as much as this author sees the former in the light of the conquest by infiltration and the latter, conquest by invasion. Making this comparison becomes imperative here, as will be further shown in this article, because the conquest by infiltration is deployed to the root of existential realities of the colonised through epistemic distortion and dismemberment. Thus, it allows for the coloniser to penetrate into the fabrics of the indigenous culture of the colonised and control their thoughts, habit, lifestyle and being.

Being armed with colonial military power and provision of Western medicinal remedies, missionaries were able to persuade Africans to convert from their ancestral indigenous religious practices to the Western religion. Many of these missionaries established educational institutions where curricula designed along the line of Western-centric ideals and practices were taught. The graduates from these educational settings automatically have a "place" of power and affluence in the colonial administrative settings. Furtherance of the subtle invasion of colonialism, lands were appropriated for the building of institutions, many of which were named after the Colonialists power brokers. For instance, the first university in Nigeria, University College, Ibadan was a satellite campus of the University of London, while the churches were also fashioned after the Western method and practices. Thus, a new socio-cultural order was instituted in the colonies that serves as the foundation upon which the colonial mentality of distrust and disdain for indigenous values, principles and ways of life was established. At the heart of the conquest by infiltration is the "epistemic and ideological trickery" (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2020, 1) that characterises the Eurocentric epistemic process. In this Western-centric system, education and religion became a potent means of inventing the ideological modernised world where all non-Western nations are expected to live in the shadow of Euromodernity.2 To this end, the Western-centric system remoulds the colonised into rationalising colonisation as an essential scheme in ideating development, progress, salvation, etc.

The sundry effect of the colonial mentality is the creation of a people that are perpetually averse to the indigenous' culture and practices, norms and values, ideas and concept, and general ways of life. CM engenders the development of a society made of persons that are detached from the socio-cultural roots of their indigenous existential reality. CM makes the sustenance of a system of power asymmetric in relation to that it is designed to rob the colonised of their originality and thus make them a sub-human reality. Consequently, the colonised loses everything African to the extent that even the learned amongst the people lives, thinks, and acts within the Western thought systems (Chimakonam 2012, 16). In the political realities of the pre/post-independence and contemporary African states re-enacts the colonial situations of masters and slave relationship. Such relationship plays out when African leaders assume their previous power, attitude and policy of the colonial master that is characterised by authoritarianism, impunity, decree order, exploitations, and suppression of minority ethnic groups.

The Agenda of Decoloniality

The African experience and the ensuing effect of its colonial mentality, necessitates the need to get free from the clutches of colonialism. Thus, the Agenda of Decoloniality could be seen as an intellectual practical response to the pseudo-ideology of European colonialism. Decoloniality thus represents a conscious and direct attempt at having a deconstructive ideological response to Eurocentrism. It describes the family of thoughts that identify colonialism/coloniality as the cause, basis, and foundation of the major problem haunting the modern world. The decolonial agenda is thus to unmask the irrationality of the Europeanisation and Americanisation of the world masked in the cloak of universalism, globalisation, science and development (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2020, 26). As practical, theoretical and ideological efforts to solve existential challenges of the colonised from their indigenous thought processes, the colonial agenda is a systematic and conscious engagements aimed at starting a new thinking and action-plans that re-humanises the world (Maldonado-Torres 2012). To achieve such coveted indigenous solutions that would be appropriate, lasting and deal with the existential challenges, Bunyan Bryant (2011, 17-18) suggested the development of "sustainable knowledge" as that which will be required for birthing rational innovations for the emancipation of the colonised people. By sustainable knowledge, he means knowledge that has the potency to move the society collectively beyond the need to self-actualisation, beyond materialism, cultural domination, human exploitation and the over-exploitation of our resources. Decoloniality thus becomes the intellectual framework for the resurgence and reconstruction of the political, epistemological and systemic movement for the liberation of the colonised people and is an essential scheme for dismantling the epistemic margin of coloniality (Chimakonam and Ogbonnaya 2021, 1). Thus, the decolonial agenda is to speak life and functionality into the decolonisation movements by calling into questions the constitutive negative elements of hegemonic Euromodernity; and most importantly by reconstructing, rebuilding and reinventing the indigenous epistemologies even in the face of the ravaging "intellectual hegemonic thought and social theories" (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2020, 28).

Obtainable herein is the fact that the decolonial agenda can be categorised into two focus areas; viz: deconstructionism and reconstructionism. These two themes serve as the motivating factors behind the decolonial agenda in dealing with the severe consequences of coloniality-systemic, epistemic, and ideological destruction of non-Western/Northern epistemologies. It should, however, be noted here that the 'deconstructing theme' seems to be the focus of most attempts towards decolonisation, with many not giving much consideration to the reconstructing view. For instance, Ndlovu Gatsheni framing the cliché of the decolonial agenda noted that:

"At one level, decoloniality calls on intellectuals from imperialist countries to undertake 'a de-imperialisation movement by re-examining their own imperialist histories and the harmful impacts those histories have had on the world. ' At another, it urges critical intellectual from the Global South to once again deepen and widen decolonisation movements, especially in the domains of culture, the psyche and knowledge production" (2020, 28).

It is worth noting that Gatsheni's synopsis of the various attempts at achieving the decolonial goal also shows that the focus has been on the deconstructing insight. While the notion of deconstruction is quite essential to the viability of the decolonial goal, without the reconstructing view, any success achieved will be short-lived. Except knowledge-making processes, ideating development, innovations, emancipatory movements, and social-economic process are recreated to not only have indigenous identities but designed for contextual application to the ailing locale and sustainable knowledge that will continue to be a mirage. Indeed, the re-Africanisation process that is engendered by the decolonial agenda requires a systematic reconstruction of African values, knowledge system and ethos for contemporary relevance. Such a reconstructive approach must be systematic to reflect and sync with the conceptual framework and logical principles undergirding African intellectual heritage. This appears a reliable way to the fulcrum of decolonial goal-achieving sustainable knowledge in Africa.

In other words, quest for epistemic emancipation must not stop at the valley of deconstructive orientations. Rather, to sustain the series of results emanating from the orientation of deconstructive ideological, response to Eurocentrism must engender a critical engagement with the indigenous knowledge forms that such deconstructive orientations reveal. One of the reasons this article takes the reconstructive orientation to be germane to the decolonial goal is that it helps to ensure epistemic freedom and development without compromising African identity. The identity that has been eroded with colonial denigration and underestimation of Africa cultural disposition and replaced with a colonial mentality, as shown above; would not only be resuscitated via the reconstructive orientation. Also, African epistemic identities would be refined to meet the contemporaneous existential challenges of wrestling knowledge and power from the "epistemic core of colonialism" (Smith 2021, xii). The reconstructive thrust for decoloniality becomes imperative considering the admonitions of the Maori anthropologist, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, regarding the need for decolonial research to "simultaneously work with colonial and Indigenous concepts of knowledge, decentering one while centering the other" (2021, xii). As well as that of Molefi Asante (2009, 2015) that intellectual thought processes in African must both be divested from the enslaving thoughts of the asymmetric power brokers and be truly indigenous thoughts schemed above the throes of colonial domination.

One of the observed clogs in the wheel of achieving the reconstructive feats is the fact that African scholars often, in the attempt to free their intellectual outputs from European ethnocentric postulations, overbears the indigenous idea in the project of decolonising African intellectual conceptual schemes. In other words, the decolonial attempts often get smeared by the weight of ethnocentrism as decolonial practitioners are often out to showcase the indigenous values and practices with little or no critical queries of such views. Indigenous world views, of which African cultural views are a genus of, are often presented as sacrosanct and unquestionable. This has proven to be counter productive and diminishes the decolonial agenda because deifying African ideas will exclude the process, or the need for critical reflection and rational engagement from the creation of sustainable knowledge systems. Also, treating indigenous thought processes as sacrosanct will diminish or placed a limit on the social and intellectual development of thoughts that would be designed above the throes of colonial domination. In addition, a deified indigenous thought process differs not in valuation or qualification than the Eurocentric epistemic process that the decolonial agenda sets out to deconstruct. In other words, the exercises of decoloniality that neither reconstruct indigenous thought for contemporary relevance nor divest its reconstruction orientations from the deification path; only re-invent the ethnocentric tendencies that engender colonialism. The question then is, why does the reconstructive orientation have to be of a critical form? Also, what viable guideline would be apt for a decolonial engagement that is formed out of critical reconstruction of indigenous thought processes? In the next session of this article, I provide answers to the questions.

Conversational Thinking

One important point to note from the questions raised above is that the quest is not about method, rather is on the need for viable guidelines. This paper uses 'viable guideline' rather than 'method' in enunciating the most apt way/process for decoloniality-critical reconstruction of indigenous ideas. The usage of 'viable guideline' shares the reservations of decolonial scholars about 'method,' especially that of Linda T. Smith (2021). She questions the appropriateness of the method in the decolonial process because existing methodologies are precipitations of institutionalised /systemic platform of inferiority entrenched in the epistemic process of the colonised people. Thus, this is not a call for methodological change, but a quest for a guideline in the process of decolonisation. While I do not aim to join the methodology debate in African philosophy, the aim here is to show an appropriate or probable philosophical guideline for the colonial agenda through philosophic exploration. Thus, with the need to have a systematic solution through innovative thinking in African philosophy, I present thematic guidelines that will serve as veritable tools in guiding the decolonial agenda. Taking this line of thought is due to the earlier noted significance of the reconstructive stance in the development of viable thoughts and eventual emancipations of the colonised people. It must be noted that the reconstructive path ensures that the decolonial agenda does not end in the foyers of talking or debating the deconstruction of colonial structures and knowledge economy. Rather, the reconstructive path engenders doing the talk through the production and innovative renewal of indigenous thoughts to meet the quest for solving perennial challenges through African intellectual thoughts. A good number of literature have discussed the conversational method of philosophy, and lots of efforts have been geared towards the development, examination, revision, and reconstruction of this philosophic thought process. I attempt not an examination of the conversational philosophic process here, but rather I explore the thinking channels of the conversational philosophic style as a guideline for the decolonial agenda.

CT is the system of thought that informs the doctrine or theory of the conversational philosophy. In other words, it is the reasoning technique that grounds the conversational movement, and indeed the method and philosophy of conversationalism (Attoe 2022, 83). The conversational philosophy is an emerging philosophic style credited to the Conversational School of Philosophy (CSP) with its root at the University of Calabar, Nigeria. The proponents of CT, chief of which are Ada Agada (2017), Aribiah David Attoe (2022), Clement V. Nweke (2016 and 2018), and Jonathan Chimakonam (2015; 2017a, 2017b and 2018), aims to advance an African philosophical thought that is enduring in addressing contemporary issues, yet engages element of traditional ideas with critical lenses. While conversing will mean to engage in a sort of informal talks between some persons, the term conversation is conceptualised as "a formal semi dialectic relationship of opposed variables involving the reshuffling of theses and antitheses by skipping the syntheses each time at a level higher than the preceding one" (Chimakonam 2018, 145). This describes a process of intellectual encounters between proponents of opposing philosophy or thoughts with the aim of improving, critiquing, correcting, and reshuffling, innovating upon their ideas and philosophies. The focus of such engagement is not about an idea or its proponents triumphing over the other, but rather it is the case of the hegemonic outlook of the Eurocentric epistemic process. Rather, conversationalism seeks to sustain 'the conversation' through identification of lacunae in one's idea as well as that of the others, creating new thoughts by filling up the lacunae and unveiling new concepts; thus an intellectual mutually complementary state is arrived at (Attoe 2022, 84).

Obtainable from the complementary intellectual engagement of conversationalism is the intellectual viability of its reasoning process, as it necessitates the reconstruction of indigenous thought processes to meeting the contemporary relevance of such ideas. To further buttress this point, Chimakonam notes:

"In a philosophical conversation of this kind, actors do not merely seek to deconstruct, they are also obligated to reconstruct except where such is impossible and clearly shown to be so" (2018, 144).

Hence, as a semi-dialectic relational process, the supposed end of the dialectic forms is obviated here. The reason is to ensure that the continuity of conversation with the aim of improving envisioned solutions and thought processes. This essential feature of CT makes it a veritable tool as a guideline for birthing ideas meant for the struggle against the perennial subjugation of the colonised knowledge forms, even in the contemporary time. As such, CT ensures the continuous creation of system of thoughts, redesigning and birthing of new concepts and the opening up new vistas for intellectual engagement between the multifarious knowledge forms of the colonised, as well as challenging, to revealing the illogicality of the Eurocentric epistemic process (Chimakonam 2018, 149).

3R-UC of Conversational Thinking

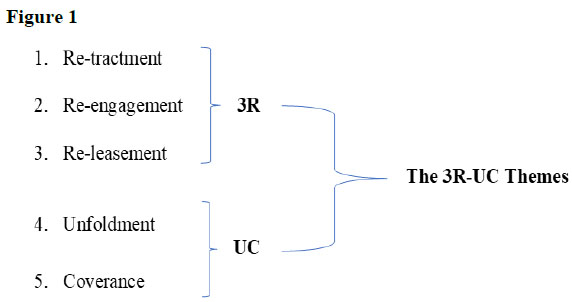

The 3R-UC themes that encapsulate the conversational philosophic styles is a proposal of Jonathan Chimakonam in his (2018, 151-154) work on the Demise of Philosophical Universalism and the Rise of Conversational Thinking in Contemporary African Philosophy. These themes designate the rational orientations that surpass identification or categorisation of thought, but also reflect the intellectual heritage of African indigenous thought that undergirds the internal system and background logic of conversationalism. Indeed, to achieve the decolonial goal, the intellectual thought processes of the colonised people must be brought to life and appropriated for dealing with lived challenges of the contemporary time, on the basis of a homegrown method and suitable background logic (Chimakonam and Ogbonnaya 2021, xi). In the light of this thought, Chimakonam, while advancing the five conversational themes, asserts that the themes have the capacity to enhance studies on any form of intellectual engagement requiring the application of CT. Thus, he posits that the proposed conversational themes will "invigorate studies in the future direction of African philosophy through the mode of conversational thinking" (2018:151). The themes are: Re-tracement, Re-engagement, Re-leasement, Unfoldment, and Coverance. I have chosen to represent these themes with a caption: 3R-UC. I used a text cum pictorial form to present the caption below:

The 3R-UC themes of CT, depicts the acronym for the proposed themes by Chimakonam. He is of the opinion that the 3R-UC themes are a veritable tool for an action-oriented mode of inquiry needed for intellectual emancipatory capacity for system building in African thought processes (Chimakonam 2018, 154).

The first of the five themes, which serves as one of the 3Rs, is 'Re-tracement.' This is a clarion call for African scholars to desist from a wrong approach to rational engagement that seeks the deification of indigenous ideas. Such practice, as noted by Oyekunle (2021, 183-186) is one of the "Methodic Crisis" in the conceptualisation of African knowledge forms. Taking the wrong approach to rational engagement is a consequence of being "plagued by a fixation on precolonial originary" (Chimakonam 2018, 152). As such, the decolonial project is being smeared by a destructive struggle, where African scholars, in the attempt to free their intellectual outputs from European ethnocentric postulations, overbears the indigenous idea in the project of decolonising African intellectual conceptual schemes. Thus, the themes of re-tracement not only challenge this destructive struggle but replace it with creative struggle. Espousing the benefit of the re-tracement theme, Chimakonam argues that it motivates scholars to shift their concern to a postcolonial imaginary, thus instilling the style and modes for creating systems, new concepts and opening new vistas for thought. As a veritable guideline for decoloniality, the re-tracement theme will enhance a creative mode of inquiry in the decolonial process.

While the re-tracement theme deals with the process of creating concept and system, the second themes of the 3R, 'Re-engagement,' addresses an essential issue in the decolonial agenda-engaging otherness. He noted that

" [T] his theme prescribes a shift from the isolated voice of the first-to-say-it or only the-self-can-say-it, to that of a critical encounter with the 'other' whether in the mode of a fellow African philosopher or different philosophical traditions or a non-philosopher" (Chimakonam 2018, 152).

The re-engagement theme deconstructs the idea of "intellectual anachronism" (Chimakonam 2015, 31) that pervades the African intellectual inquiry. Such intellectual anachronism is characterised by African scholars theorising with a sense of self-imposed isolation, where it is assumed that the rest of the world, or some other scholars within Africa, are not worth talking to. As an advantage to the decolonial agenda, the re-engagement theme enhances what Aribiah David Attoe called "the up-down movement of thought" (2022, 87-88), where ideas are made open to complementary engagement between interlocutors to achieve the opening up new vista of knowledge, improvement of held opinion, and the reconsideration of opinions. This theme also ensures that a reconstruction of existing ideas happens, not just on an uncritical level, but with a complementary engagement with the self, but also other scholars within one's intellectual place and space. As such, the thought processes that will engender decolonial process will be made to go through the crucible of critical fire to birth ideas and concept that are rational, logical, systematic and viable.

The 'Re-leasement' theme drives home to the rubrics of decoloniality, as it deals with the intellectual emancipation of reason of the colonised thought process. As noted earlier in this article, the conquest by infiltration through rational and intellectual imprisonment of the colonised facilitates and sustains colonial mentality, especially by the asymmetric power control of the world's knowledge forms and economy. Thus, the re-leasement theme that argues for the contextualisation of reason for true intellectual liberation deconstructs entrapment of African reasoning process in the shadow of Eurocentric meta-philosophy, hegemony and universalism (Chimakonam 2018, 153). Thus, the re-leasement theme, unveil the platform of intercultural conversation as a contextual manifestation of thoughts and concept is recognised, giving voice to the colonised. Concluding on the third theme of the 3Rs, Chimakonam argues:

"[r]eason has many voices and not one voice, and many visions and not one vision;... in all of these particulars, none is worthy of absolutisation, but in conversation they each would come to occupy a modest place to the advantage of all" (Chimakonam 2018, 153).

The re-leasement theme thus fits into the decolonial agenda of establishing voice for the voiceless, creating an identity for the invisibles, and making names for the nameless.

The last two of the CT themes: 'Unfoldment' and 'Coverance' are a consequence of the 3Rs. While unfoldment enhances the regular creation and supplies of new concepts, thought and ideas through critical engagement and intellectual interactions among interlocutors in the intellectual place and place; Coverance helps to achieve more milestones in the reconstructive stance of CT as it ensures recovery of African intellectual standpoint from the hegemony of Western-centric thought process (Chimakonam 2018, 153-154). As a viable and systematic guideline for the decolonial process, the Coverance theme enhances the coverage of more grounds, especially through its reconstructive stance that allows for the development of new concepts and ideas. In the same vein, the unfoldment theme ensures the sustenance of life of ideas and concept in the African space through the constant supply of new thoughts, critical deconstruction of existing ones, and reconstruction of realigned thoughts.

The benefits obtainable from CT, especially through the explored themes, make it a veritable mode of intellectual engagement for the decolonial agenda. Hence, this paper is of the view that conversational decoloniality (CD)-that is, a conjoin of the CT with the decolonial goal could serve as veritable guidelines for a viable mode of system thoughts for the decolonial agenda. By the dictate of CD's intellectual viability, the polarisation and segmentations of the world into the self and the other that characterises the Eurocentric epistemic process is questioned and deconstructed. CD also recreates a system of critical and meaningful engagement between the varying segments of humanity with complementary stance, thus obviating any form of segregation, hegemonic tendency or ethnocentrism. In addition, appropriating the conversational themes as guidelines for the decolonial agenda makes the systematic reconstitution of the colonised's dismembered knowledge systems possible. As such, the indigenous context of existential reality that has been adjudged nonexistence, illogical and non-essential; intuitively alive and employed to lived engagements. Consequently, the hegemonic lens of an Eurocentric conception of reality, which engenders the dual forms of conquest of colonised as well as the colonial mentality, is eliminated. Additionally, CD possesses the ability to allow for a recreation of the dismembered or destroyed thoughts processes of the colonised for intracultural and intercultural intellectual interactions with the rest of the world. Indeed, with CD, the ensued homegrown solutions that the decolonial agenda aimed at for the colonised can transcend from "a specific place to the global space" (Attoe 2022, 85). It is in this vein that I am of the strong opinion that the decolonial studies can have "perspectival contribution[s]" (Chimakonam and Ogbonnaya 2021, x) to the formation, advancement and dissemination of sustainable knowledge forms, especially as it relates to the exploration of indigenous conceptual schemes in the quest for sustainable solution to the perennial problems of the colonised.

Conclusion

I have interrogated the decolonial agenda and concluded that a conversational decolonised method would, among other things be appropriate for a scholarly response to the colonial denigrations and underestimations of African cultures and traditions. CD has been shown as a viable framework for achieving African self-definition in the modern world without compromising the African identity. This is the primus aim of African decoloniality-proffering solutions to existential challenges of Africa from the African thought process in a manner that is pragmatic, rational, sustainable, and exportable to other climes.

References

Agada, A. 2017. "Philosophical Sagacity as Conversational Philosophy and It's Significance for the Question of Method in African Philosophy." Filosofia Theoretica 6 (1): 69-89. https://doi.org/10.4314/ft.v6iL4 [ Links ]

Amin, S. 2009. Eurocentrism: Modernity, Religion, and Democracy: A Critique of Eurocentrism and Culturalism, edited Moore, R., and J. Membrez. New York: Monthly Review Press. [ Links ]

Asante, M. K. 2009. " Africology and the Puzzle of Nomenclature." Journal of Black Studies 40 (1): 12-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934709335132 [ Links ]

Asante, M. K. 2015. African Pyramids of Knowledge: Kemet Afrocentricity and Africology. Brooklyn New York: Universal Write Publication LLC. [ Links ]

Attoe, A. D. 2022. "Examining the Method and Praxis of Conversationalism." In Essays on Contemporary Issues in African Philosophy, edited by Chimakonam, J. O., E. Etieyibo, and I. Odimegwu, 79-90. Switzerland AG: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70436-06 [ Links ]

Bryant, B. 2011. Environmental Crisis or Crisis of Epistemology? Working for Sustainable Knowledge and Environmental Justice. edited by Bryant B. New York: Morgan James Publishing. [ Links ]

Cesaire, A. 2000. Discourse on Colonialism. edited by T. and J. Pinkham. New York: Monthly Review Press. [ Links ]

Chimakonam, J. O. 2012. Introducing African Science: Systematic and Philosophical Approach. Bloomington: Author House. [ Links ]

Chimakonam, J. O. 2015. "Conversational Philosophy as a New School of Thought in African Philosophy: A Conversation with Bruce Janz on the Concept of >Philosophical Space." Confluence: Online Journal Of World Philosophies 3: 9-40. [ Links ]

Chimakonam, J. O. 2017. "Conversationalism as an Emerging Method of Thinking in and beyond African Philosophy.". Acta Academica 49 (2): 11-33. https://doi.org/10.18820/24150479/aa49i2.1 [ Links ]

Chimakonam, J. O. 2017. "What Is Conversational Philosophy? A Prescription of a New Theory and Method of Philosophising, in and Beyond African Philosophy." Phronimon 18 (1): 115-30. https://doi.org/10.25159/2413-3086/2874 [ Links ]

Chimakonam, J. O. 2018. "The 'Demise' of Philosophical Universalism and the Rise of Conversational Thinking in Contemporary African Philosophy." In Method, Substance, and the Future of African Philosophy, edited by Edwin. E., 135-59. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70226-18 [ Links ]

Chimakonam, J. O., and L. U. Ogbonnaya. 2021. African Metaphysics, Epistemology, and a New Logic: A Decolonial Approach to Philosophy. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72445-0 [ Links ]

Emeagwali, G. 2014. 'Intersections between Africa's Indigenous Knowledge Systems and History'. In African Indigenous Knowledge and the Disciplines, edited by Gloria Emeagwali, and George J. Sefa Dei 1-17. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-770-4_1 [ Links ]

Falola, T., and D. Sanchez. 2014. African Culture and Global Politics: Language, Philosophies, and Expressive Culture in Africa and the Diaspora. 1st edition. Edited by Falola, T., and D. Sanchez. New York: Routledge-Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315883533 [ Links ]

Falola, T. 2002. Key Events in African History: A Reference Guide. Greenwood Press Connecticut: Greenwood Press. [ Links ]

Fanon, F. 1968. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press. [ Links ]

Guyo, D. 2011. The Quest of Re-Grounding African Philosophy Between Two Camps. Saarbrucken, Germany: VDM Verlag Dr Muller and Co Kg. [ Links ]

Ipadeola, A. P. 2017. 'The Imperative of Epistemic Decolonisation in Contemporary Africa'. In Themes, Issues and Problems in African Philosophy, edited by Ukpokolo, I. E. 145-61. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40796-8_10 [ Links ]

Jimoh, A. K. 2018. "Reconstructing a Fractured Indigenous Knowledge System 65 (1/2018)" Synthesis Philosophica 65 (1): 5-22. https://doi.org/10.21464/sp33101 [ Links ]

Kaya, H. O., and Y. N. Seleti. 2014. African Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation: An African Young Scientists Initiative. edited by Hassan O. Kaya, and Yonah N. Seleti. Wandsbek: People's Publishers. [ Links ]

Lenkabula, P. 2021. "Reclaiming Africa's Intellectual Futures: Inauguration and Investiture Speech as Principal and Vice Chancellor." University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Maldonado-Torres, N. 2012. "Decoloniality at Large: Towards a Trans-Americas and Global Transmodern Paradigm (Introduction to Second Special Issue of "Thinking through the Decolonial Turn"). Transmodernity (Spring): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.5070/T413012876 [ Links ]

Mpofu, W. J. 2013. "African Nationalism in the Age of Coloniality: Triumphs, Tragedies and Futures." In Nationalism and National Projects in Southern Africa: New Critical Reflections, edited by Ndlovu-Gatsheni. S. J., and F. Ndlovu: 96-116. Pretoria: African Institute of South Africa. [ Links ].

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. 2018. Epistemic Freedom in Africa: Deprovincialization and Decolonisation. United Kingdom: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429492204 [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. 2020. Decolonisation, Development and Knowledge in Africa: Turning over a New Leaf. United Kingdom: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003030423 [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. 2021. "The Primacy of Knowledge in the Making of Shifting Modern Global Imaginaries." International Politics Reviews 9: 110-15. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41312-021-00089-y [ Links ]

Nkrumah, K. 1965. Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism. New York: International Publishers. [ Links ]

Nweke, C. V. 2016. "Mesembe Edet's Conversation with Innocent Onyewuenyi: An Exposition of the Significance of the Method and Canons of Conversational Philosophy." Filosofia Theoretica: Journal of African Philosophy Culture and Religion 5 (2): 54-72. https://doi.org/10.4314/ft.v5i2.4 [ Links ]

Nweke, V. C. A. 2018. "Global Warming as an Ontological Boomerang Effect: Towards a Philosophical Rescue from the African Place." In African Philosophy and Environmental Conservation, edited by Chimakonam, J. O., 149-60. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315099491-12 [ Links ]

Omanga, D. 2020. "Decolonisation, Decoloniality, and the Future of African Studies: A Conversation with Dr Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni." Accessed April 8, 2022. https://items.ssrc.org/from-our-programs/decolonisation-decoloniality-and-the-future-of-african-studies-a-conversation-with-dr-sabelo-ndlovu-gatsheni/. [ Links ]

Onwurah C., and Boateng P. 2022. "All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) Africa Education Inquiry Report." United Kingdom: Royal African Society. [ Links ]

Oyekunle, A. A. 2021. An Exploration of an Indigenous African Epistemic Order: In Search of a Contemporary African Environmental Philosophy. University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Ramose, M. 2002. "The Struggle for Reason in Africa". In Philosophy from Africa: A text with Readings, edited by Coetzee, P. H., and A. Roux., 1-8. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429344596-4 [ Links ]

Ramose, M. 2020. "On Finding the Cinerarium for Uncremated Ubuntu: On the Street Wisdom of Philosophy." In Knowledge Born in the Struggle: Constructing the Epistemologies of the Global South, edited by de Sousa Santos, B., 58-77. New York: Routledge-Taylor and Francis. [ Links ].

Rodney, W. 2012. How Europe Underdeveloped. Cape Town: Pambazuka Press. [ Links ]

Santos, B. D. S. 2007. "Beyond Abyssal Thinking: From Global Lines to Ecologies of Knowledges." Review xxx (1): 45-89. [ Links ]

Santos, B. D. S. 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. Boulder. CO: Paradigm Publishers. [ Links ]

Smith, L. T. 2021. Decolonising Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 3rd edn. Leiden: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. [ Links ]

Thiong'o, N. 1986. Decolonisation of the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. Kenya: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Tibebu, T. 2011. Hegel and the Third World: The Making of Eurocentrism in World History. New York: Syracuse University Press. [ Links ]

Wiredu, K. 1995. "The Need for Conceptual Decolonisation in African Philosophy." In Conceptual Decolonisation in African Philosophy: Four Essays by Kwasi Wiredu, edited by Ibadan, O. O., 22-32. Ibadan: Hope Publication. [ Links ]

Zegeye, A., and M. Vambe. 2011. Close to the Source: Essays on Contemporary African Culture, Politics and Academy. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203807071 [ Links ]

1 The Eurocentric epistemic process is used to capture the Western-centric conception of rationality as an exclusive prerogative of the Western world. Thus, non-Western conceptual schemes, ontological realities and humanities were objectified as illogical, inappropriate and non-existence. Several scholars have denounced this line of thoughts and revealed the illogicality inherent in the Eurocentric epistemic process, among which are: (Falola 2002), (Ramose 2002), (Guyo 2011), (Santos 2007), (Santos 2014) (Emeagwali 2014), (Jimoh 2018), (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2018), (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2021), and (Oyekunle 2021).

2 Euromodernity is the cultural expression of the Eurocentric system wherein the inferiorisation of others and the superiorisation of Europeans is the ideological core. See Tibebu 2011, xvi-xx1; Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2018, 89; and Oyekunle 2021, 168-172.