Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology

On-line version ISSN 1445-7377

Print version ISSN 2079-7222

Indo-Pac. j. phenomenol. (Online) vol.22 n.1 Grahamstown 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20797222.2022.2105166

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Therapeutic tool or a hindrance? A phenomenological investigation into the experiences of countertransference in the treatment of sexually abused children

Tshepo Tlali

Department of Psychology, University of Johannesburg, South Africa Correspondence: drtshepotlali@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Since its inception in the 1900s, the concept of countertransference has been mired in controversy. Psychoanalytic literature is divided on its utility, significance and its clinical value in psychotherapy. While some psychotherapists have advocated for the importance of therapists' expertise in the comprehension and processing of countertransference dynamics in the treatment of sexually abused children, others see no value in competency in countertransference in trauma treatment of sexually abused children. The purpose of this article is to explore whether countertransference is a useful therapeutic tool, or a hindrance in the treatment of sexually abused children. A qualitative paradigm, particularly interpretative phenomenology, was employed in this research to make meaning of the therapists' experiences. The analysis of the results revealed the following five main themes that were supported by 18 superordinate themes. These themes reveal that therapists treating sexually abused children experience a myriad of feelings, including a) feeling emotionally overwhelmed, b) anger toward perpetrators and the need to protect and rescue their patients, c) the importance of social support and self-healing, d) feelings of empathy and identification with the client, and e) erotic countertransference. These findings reveal two contradictory findings. Firstly, they tell of variable utilisation of countertransference among participants and, secondly, they highlight a lack of application of countertransference in the treatment of sexually abused children. The implications of the current study are that there is a need to both highlight the importance of countertransference as a therapeutic tool and to incorporate it in the treatment of sexually abused children.

Keywords: lived experiences; psychotherapy; qualitative paradigm; therapeutic relationship; trauma therapists

Introduction

The experiences of treating sexual abused children have been studied extensively and from a different theoretical perspective and using different research methods (Neubauer et al., 2019; Nissen-Lie et al., 2022). Sexual abuse of children and adolescents is a stark reality worldwide and the picture seems to be getting bleaker daily. Murray et al. (2014) describe child sexual abuse as encompassing many types of sexually abusive acts toward children, including sexual assault, rape, exposure to pornography, incest and the commercial sexual exploitation of children. Most psychotherapists who treat sexually abused children (irrespective of their theoretical orientation) tend to agree that treating them is likely to evoke varied experiences of traumatic and evocative emotions (Pistorius et al., 2008; Wheeler & McElvaney, 2018; Cao, 2019).

The utility of countertransference with psychotherapy

As psychoanalysis moves into its second century, a central theoretical task has become the construction of increasingly nuanced understandings of the analytic process. It is no longer presumed to be uniform and straightforward and has the concept of countertransference. The concept of countertransference

has been predominantly associated with psychodynamic psychotherapies and has been used in qualitative research to loosely account for the emotions and feelings that are stirred in a psychotherapist by the patient (Gemignani, 2011; Holmes, 2014). The past half a century or so there has been substantial interest in the psychotherapeutic research that sought to investigate important aspects of the application of psychodynamic ideas that include the awareness of the psychotherapists' emotional and behavioural responses to their patients (Williams & Irving, 1995; Dalenberg, 2018; Neubauer et al. 2019; Hennissen et al., 2020). While there are divergent views on the usefulness and application of the notion of countertransference in qualitative research, most of the research and emerging literature suggest its existence in divergent clinical-theoretical theories and schools of thought and that it has utility with all psychological disorders (Tlali, 2016; Luyten, 2017). The majority of qualitative research and psychotherapy literature on the descriptions of countertransference have generally focused on the usefulness of countertransference as an invaluable therapeutic tool (Stefana, 2017; Loewenthal, 2018). This is more so to contemporary relational and intersubjective psychotherapists who construe of countertransference in line with Klein's (1946) notion of projective identification, where "feelings may be put into the analyst by the patient" (Holmes, 2014, p. 168). On the hand, some psychotherapy researchers and psychotherapists contest the notion of countertransference (and/or projective identification) as a means that seeks to describe how unwanted, unacceptable feelings and thoughts gets to "put onto and into others" (Spillius & O'Shaughnessy, 2012, p. 3). One of the scathing views of the importance of countertransference comes from Loewenthal (2018, p. 365), who questions the merit of the use of countertransference in psychotherapy treatment. She asks us to consider what's happened to "countertransference" and whether it has therapeutic merit or is more a way therapists provide something potentially harmfully on the cheap (with no need for what was previously considered a proper training therapy) whilst actually deluding themselves they are the centre of their consulting room world.

The concern raised by Loewenthal (2018) resonates with the many countertransference enactments by psychotherapists with vulnerable patients that are littered in the psychoanalytic literature (Stuthridge, 2015). For example, Stern (2010) cited examples of mutual enactments in which the psychotherapist's behaviour could be related to both the patient's repeating patterns and the psychotherapist's unique personal history or script. For those psychotherapists who are trained and competent in one or more psychodynamic modality of psychotherapy treatment, the concept of countertransference is seen more as a facilitative and healing tool (Holmes, 2014). On the other hand, for psychotherapists who employ other therapeutic modalities, the concept of countertransference does not have meaning and relevance in psychotherapy treatment (Kiesler, 2001; Stuthridge, 2015). While I acknowledge the contentious nature of the manifestation and application of the concept of countertransference in qualitative research, the current article seeks to investigate the therapists' experiences of countertransference in the treatment of sexually abused children.

Rationale

Over the past few decades, psychological treatment of sexually abused children has taken centre stage in psychology literature (Benatar, 2000; Wickham & West, 2002; Possick et al., 2015; Wheeler & McElvaney, 2018; Wekerle et al., 2019). Psychotherapists treating sexually abused children are more likely to experience vicarious trauma, compassion fatigue and burnout and feelings of inadequacy (Cao, 2019; Reddi, 2020). Other researchers and therapists have reported troubling countertransference enactments with sexually abused children (Mann, 1997; Stuthridge, 2015; Little, 2018). While I acknowledge that the notion of countertransference is historically associated with psychoanalytic psychotherapies, I believe that the experiences of feeling with the patient or emotionally been touched and/or reacting to a traumatic narrative of the patient are universal experiences that cannot be limited to psychoanalytic or psychodynamic therapies only. The current study adopts a psychodynamic view in exploring the issues of therapeutic utility of countertransference in the treatment of sexually abused children and assumes sexually abused children bring variable and complicated transference issues to therapy (Walters, 2009; Dalenberg, 2018). It further conceives of sexually abused children as a special population of patients who present with unique and sometimes intractable defence mechanisms and projection and transference reactions (Kluft, 2011). Many trauma researchers have documented the difficulties involved in this type of psychotherapy treatment and many psychoanalysts have identified transference and countertransference matrices and the importance of therapeutic relationships as fulcrums upon which the success of this type of therapy hinges (Wilson & Lindy, 1994; Courtois, 2010; Maroda, 2010; Gelso, 2011). As has been alluded above, most researchers in this area agree that the treatment of sexually abused children remains a challenge to many therapists as it evokes, at times, very troubling countertransference reactions on the part of the therapist. The aim of this study was thus to investigate countertransference reactions among psychotherapists who are treating sexually abused children, with a view to add to the existing body of knowledge in the treatment of sexually abused children.

Countertransference

The concept of countertransference has a long history in psychoanalytic psychotherapy (Heiman, 1950; Racker, 1957; 1968). While reference to countertransference appeared very early in psychoanalytic literature, many writers took active interest in it only in the last 70 years or so (Racker, 1968; Slakter, 1987; Maroda, 2004). Other than unsubstantiated statements to the effect that therapists could have transference reactions to their patients' transference reactions, very little attention was given to its existence (Gelso & Hayes, 2007). Initially, countertransference was largely seen as an impediment to the process of psychotherapy (Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983), and thus therapists were encouraged to get self-analysis to rid themselves of their unresolved personal issues (Orbach, 2014). While a little hesitant at first about his discovery of countertransference as an important tool to unlocking the patient's unconscious, Freud urged therapists to study themselves and their own reactions toward their patients to understand the inner working of their patients. He wrote that

just as the patient must relate all that self-observation can detect, and must restrain all the logical and affective objections which would urge him to select, so the physician must also put himself in a position to use all that is told him for the purposes of interpretation and recognition of what is hidden in the unconscious, without substituting a censorship of his own selection which the patient forgoes (Freud, 1912, p. 110).

During the same period, Freud made the following statement that was directly related to countertransference (Freud, 1910; cited in Tower, 1956, p. 224):

We have begun to consider the countertransference which arises in the physician as a result of the patient's influence on his unconscious feelings and have nearly come to the point of requiring the physician to recognise and overcome this countertransference in himself.

From this statement, it is apparent that Freud viewed countertransference as the result of the patient's influence on the therapist's unconscious feelings (Reich, 1960), and again as an impediment to the treatment process (Freud, 1910). Seeing that Freud initially viewed the concept of countertransference as a hindrance to the analysis, he thus advocated for the overcoming of any intrusion into the analytic process (Cooper, 2010). According to Gelso and Hayes (2007), these pronouncements by Freud had a profound effect on the concept of countertransference and moved the entire field of psychoanalysis in a different direction.

This conceptualisation of countertransference, which has also come to be known as negative, subjective countertransference (Wilson & Lindy, 1994; Shubs, 2008), and tends to place the origin of countertransference reactions firmly in the person of the therapist. However, in contemporary psychotherapy this conceptualisation of countertransference has significantly changed to emphasise both the subjective contribution of the therapist and the joint co-construction of the therapist and the patient (Aron, 2007; Gelso, 2011).

Countertransference, in the contemporary conceptualisation, is conceived as a normal facet of object relations in intimate relationships (Tubert-Oklander, 2013), which cannot be avoided and should not be overcome (Eagle, 2011). Rather, the therapists' reactions to the patient's experiences and disclosures are regarded as fertile ground for advancing therapeutic understanding and action (Aron, 2007; Cooper, 2014). This means that the therapist's thoughts, feelings and fantasies provide an insight into the inner world of the patient and the true nature of the problem. In contemporary psychotherapy, the concept of countertransference entails the full emotional and physical presence of the person of the therapist. According to Carnochan (2001), the therapists' presence (both emotionally and physically) allows the therapeutic relationship to be transformative. Central to a therapists' presence and participation is the effectiveness with which therapists are able to manage and utilise their countertransference feelings and reactions (Carnochan, 2001). Thus, in contemporary psychotherapy, one of the essential therapeutic skills is the competence of therapists in working with countertransference (that is, the capacity to be emotionally present with the patient in the therapeutic situation). Carnochan (2001, p. 27) argues that this requires contemporary therapists "to move beyond seeing countertransference merely as a source of information and to begin to use it as a source of therapeutic action". In this regard, therapists are urged to employ conscious and effective use of therapeutic self-disclosure (Orbach, 2014) and metacommunication (Safran & Muran, 2000) to share their feelings, experiences and thoughts with their patients in the therapeutic setting. For the therapist, countertransference self-disclosure is not merely a random act of "affective impulsivity" (Carnochan, 2001, p. 28), and is not about "intentionally concealing or revealing" (Orbach, 2014, p. 22). Instead, a therapist's self-disclosure is about the authenticity of being with the patient in the therapeutic context. In the therapeutic context, therapists are always ready to engage authentically with their patients.

Experiences of therapists in the treatment of sexually abused children

Possick et al. (2015) and Wheeler and McElvaney (2018) assert that most therapists find it challenging to treat sexually abused children as this type of therapy tends to evoke a lot of trying emotions. While it is widely acknowledged that treating severely sexually abused children may lead psychotherapists to experience issues associated with burnout and vicarious traumatisation (Brockhouse et al., 2011; Jirek, 2015), the key factors in comprehending the psychotherapists' experiences of countertransference reactions in treating sexually abused children lie in understanding the different manifestations and enactments of countertransference reactions (Tlali, 2016). Wilson and Lindy (1994) and Shubs (2008) have identified two types of countertransference reactions, namely the objective and the subjective. To this end, Wilson and Lindy (1994, pp. 15-16) see objective countertransference as "expectable affective and cognitive reactions experienced by the therapist in response to the personality, behaviour, and traumatic story of the patient". Similarly, Kiesler (2001) argues that the psychotherapist's objective countertransference reactions occur when a therapist's reaction to their patient does not deviate significantly from the baseline reactions to the patient's life story. For example, most therapists treating sexually abused children generally experience intense feelings of anxiety, fear, shame, anger and grief (Robinson-Keilig, 2014). Owing to the fact that some of the abovementioned reactions would be regarded as normal to most psychotherapists treating sexually abused children, these reactions would be regarded as non-pathological (Shubs, 2008), and thus they are deemed not to interfere with the psychotherapist's ability to be empathetic, compassionate and appropriate to the therapeutic task (Wilson & Lindy, 1994).

On the other hand, Wilson and Lindy (1994, p. 16) define subjective countertransference reactions as "the personal reactions of the therapist that originate from the therapist's personal conflicts, idiosyncrasies, or unresolved issues". Thus, they argue that, in the therapeutic situation, these subjective countertransference responses occur because the patient's transference issues reactivate conflicts and unresolved personal concerns in the therapist's life.

What further complicates treating sexually abused children is the fact that in most cases the abuse happened in the context of a trusting relationship between the child and an adult (Sheinberg & Fraenkel, 2001). Similarly, psychotherapy with sexually abused children occurs in the context of what should be, at least in theory, a trusting therapeutic relationship with the person of the therapist. To this end, Inji (2001), Saakvitne (2002) and Alvarez (2010) have argued that sexually abused children bring fear, profound mistrust, anger, as well as yearning, intense loneliness and fragile hope to the therapeutic relationship. This emphasises the importance of a sound, trusting relationship between the therapist and sexually abused children in psychotherapy (Horvath, 2018).

In addition to the challenges already mentioned, psychotherapy with sexually abused children abounds with transference and countertransference issues and reactions (Alvarez, 2010; Possick et al., 2015). Due to the nature of the relational trauma associated with child sexual abuse, most sexually abused children are more prone to transference behaviour (i.e. projecting their own unconscious behaviours, enacting feelings and thoughts) onto the person of the therapist in the therapeutic relationship (Courtois & Ford, 2009; Alvarez, 2010). Inevitably, the patient's projections form a very important aspect of the treatment; it is both the challenge and the responsibility of the therapist to assist the client to recognise and to deal with their transference behaviour (Alvarez, 2010; Stuthridge, 2015). However, Tlali (2016) cautioned us about the difficulties of using countertransference feelings and reactions with children, as they may not be able to engage meaningfully in this process. Given their fragile sense of self, poor boundaries and often-inappropriate sexual tendencies, sexually abused children are more likely to sexualise the therapeutic relationship (Tlali, 2016). These sexualised transference behaviours on the part of sexually abused children may lead to what Mann (1997), Benatar (2000) and Atlas (2015) have termed erotic countertransference on the part of the therapist. According to Jorgenson (1995), 87 per cent of therapists report being sexually attracted to one or more of their patients, and more than half feel guilty about the attraction. Consequently, this type of countertransference reaction in the therapeutic relationship mainly come about in two ways. Firstly, a sexual countertransference reaction is a response to the therapist's fascination with the patient's forbidden and unresolved issues (Little, 2018), and secondly, sexual countertransference reactions could be as a result of powerful transference behaviour on the part of the patient (Wickham & West, 2002; Possick et al., 2015). Ultimately, the enactment of erotic countertransference is more likely to cause untold damage to patients.

To mitigate the variety of personal and professional indiscretions on the part of the therapist, self-care and professional care have been mooted as possible solutions (Rasmussen, 2011; Jirek, 2015). In the same breath, Skovholt and Trotter-Mathison (2016) and Tlali (2016) have argued for the importance of developing sound and supportive personal, social and professional support as well as maintaining a professional connection, especially when treating sexually abused children because of the emotional and psychological impact that treating this stratum of patient has on the person of the therapist. These professional connections can be in the form of ongoing professional education, support groups, supervision and personal psychotherapy (Rasmussen, 2011). These support structures allow the therapists a space in which to talk about the difficulties they encounter in their work, without having to feel any sense of shame about these feelings (Tlali, 2016) and with knowledge that they will receive guidance on how to tackle some of the difficult terrain in the work (Skovholt & Trotter-Mathison, 2016).

Moreover, psychotherapists' experiences in treating sexually abused children tended to focus on the therapists' experiences of empathy and identification with the experiences of the children. Although this experience of empathy and identification is a common feature in any trauma psychotherapy, Saakvitne (2002) and Tlali (2016) have argued that these emotional reactions are more pervasive in therapists with histories of childhood sexual abuse. On the other hand, studies focusing on therapists treating sexually abused children have reported post-traumatic growth, including positive subjective feelings of being good therapists when they feel that they have been able to assist sexually abused children with their trauma (Malchiodi, 2016). The experience of post-traumatic growth, in this context, refers to the feeling of fulfilment that comes from providing the necessary support, which might in turn lead to the healing of traumatised survivors. This article will report on how therapists deal with countertransference during psychotherapy with sexually abused children in their practices.

Method

The aim of this study was to investigate the subjective experiences of therapists' countertransference in the treatment of sexually abused children. Consistent with the aims of this study, the current study was located in a broader phenomenological approach to the investigation of such experiences (Smith et al., 2013; Howitt & Cramer, 2017). According to Teherani et al. (2015), phenomenology is as an approach to research that seeks to describe the essence of a phenomenon by exploring it from the perspective of those who have experienced it. Usually, the goal of phenomenology is to describe the meaning of this experience of what was experienced and how it was experienced (Tuffour, 2017). Neubauer et al. (2019) argue that there are different kinds of phenomenology and that each is rooted in different ways of conceiving of the what and how of human experience. This means that each approach of phenomenology is rooted in a different school of philosophy, namely transcendental (descriptive) phenomenology (Barua & Das, 2014; Neubauer et al., 2019) and hermeneutic (interpretative) phenomenology (Gadamer, 1960; Hooker, 2015). Given the emphasis of the current study, hermeneutic (interpretative) phenomenology, as proposed by Heidegger (Tuffour, 2017) and Gadamer (1960; Grondin, 2002) will be used to make sense of the participants' experiences of treating sexually abused children. Hermeneutic phenomenology emphasises that lived experience is an interpretative process that is situated in an individual's lifeworld. Furthermore, interpretative phenomenology construes the observer and/or the participant as part of the world and not bias-free (Qutoshi, 2018). In this way, an interpretative phenomenologist reflects on essential themes of the participant's experience with the phenomenon while simultaneously reflecting on their own experiences.

Sampling procedures and participants

For sampling purposes, I employed criterion-based selection methods (Nieuwenhuis, 2015). A selection process preceded this sampling method. According to Gibson and Hugh-Jones (2012), both selection processes and sampling are important in a qualitative study of this nature where the researcher seeks to understand the lived experiences of a particular population. In this instance, the selection process involved identifying the population to be studied, while the sampling involved selecting a smaller subset from the original population.

The study was conducted in the metropolitan municipality of Buffalo City, South Africa. According to the municipal website, the city is situated on the east coast of South Africa in the Eastern Cape province. It includes the city of East London and towns like Bhisho and King William's Town, as well as large townships like Mdantsane and Zwelitsha. According to Statistics South Africa, the total population of Buffalo City in 2016 was 834 997, with 85 per cent being black Africans, followed by whites at 7 per cent, 6.7 per cent being coloureds and 0.90 per cent Indian/Asian (StatsSA, 2016). Participants of the study were registered psychologists, working in private practice and were treating sexually abused children. The specific inclusion criteria for the study were as follows:

-

Participants who had at least two years' post-registration working experience as a counselling or clinical psychologist;

-

Participants who were in private practice and treating sexually abused children among other the patient population. However, these therapists were not required specifically to be trauma therapists;

-

Participants who were in personal therapy or in clinical supervision; and

-

Participants who met the abovementioned criteria and were willing to participate in the study.

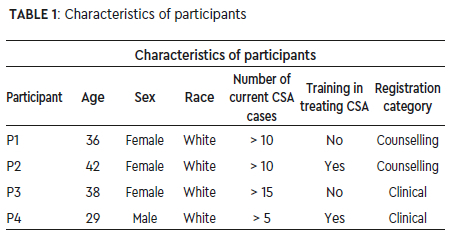

The two-year post-registration experience requirement for inclusion in the study was to ensure that the participants have a sufficient child sexual abuse caseload. I e-mailed an introductory letter (which introduced the purpose of the study and invited interested psychologists to participate in the study) to all psychologists listed in the directory of practising psychologists in East London. According to the directory, there were 35 registered psychologists in 2016. Thus, this formed the core population of the study from which the sample was drawn. Of the 35 practising psychologists in the Buffalo City municipal area, only four participants who met the inclusion criteria were willing to participate in the study. Prior to the commencement of the study, prospective participants were informed of the nature of study, which involved describing and sharing their countertransference experiences in treating sexually abused children. All four participants who took part in the study declared that they were not trained trauma therapists. The participants also disclosed that they were not specialists in psychodynamic psychotherapy (which emphasises the importance of countertransference in psychotherapy treatment). Of the four participants, two reported having a childhood history of sexual abuse (i.e. Participants 2 and 4). The relatively limited sample size directly reflects the small pool of possible psychotherapists working therapeutically with sexually abused children in the Buffalo City municipal area. The four participants were between 29 and 42 years old and had between three and ten years' working experience in the field of counselling and psychotherapy. Table 1 lists the characteristics of each of the participants dealing with child sexual abuse (CSA).

Data collection

I made use of unstructured, individual interviews to collect the data required for this study. All interviews were audio recorded with the permission of the participants and were transcribed verbatim. I started the interview by asking the participants to describe their experiences of providing counselling or psychotherapy to sexually abused children, which facilitated a full exploration of the participants' personal experiences. Specific attention was paid to how the participants described their countertransference experiences of treating sexually abused children and the interview continued as an interactive process (Howitt & Cramer, 2017). Where necessary, I asked the participants to elaborate and reflect on specific instances of countertransference enactments. In total, each interview took between 40 and 50 minutes and all these individual interviews were conducted at the participants' practices. I, as a counselling psychologist with over 15 years' experience in counselling and psychotherapy, carried out all the interviews.

Data analysis

The current study employed interpretive procedures to explore the lived experiences and meanings that participants attach to their experiences of treating sexually abused children. Morrissette's (1999) model of data analysis was employed to analyse the data collected. This method was preferred due to its pragmatic and systematic approach to phenomenological data analysis. The data analysis method comprises the following steps outlined by Morrissette (1999):

Step one: Reading the interview as a text

This step involves reading each interview transcript several times, while noting significant statements and words related to the subject under investigation.

Step two: First-order thematic extractions

The researcher identifies and collects significant statements and sub-themes. Once the key statements of the interview have been identified, they are paraphrased and assigned a theme name. Next, the researcher places these emergent sub-themes in tabular form. These emergent themes are referred to as first-order thematic abstractions (Morrissette, 1999).

Step three: Second-order thematic cluster

n this step, the researcher creates a second-order cluster of themes by rearranging the initial themes created in step two.

Step four: Individual participant synthesis

According to Morrissette (1999), the focus of step four is on describing, synthesising and summarising each individual participant's experiences of the phenomena under investigation.

Step Five: Overall synthesis of participants' experiences

The researcher reflects on the various themes which have emerged from the synthesis of each participant. According to Morrissette (1999), this step allows the researcher an opportunity to understand the specific individual and the shared experiences of the participants.

Step six: Between participant analysis

The final step of Morrisette's data analysis entails a rich description and comparison of the participants' countertransference experiences in the psychotherapy process.

Ethical considerations

The University of Johannesburg Ethics Committee for Research on Human Subjects granted ethical clearance for this study. Participants were informed that their participation in the study was voluntary and that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without offering reasons for doing so (West, 2002). Permission to record the interviews was sought from the participants. Identifying information, such as names, places, dates, etc., were altered to ensure confidentiality and anonymity (Crocket, 2014). All the participants signed the informed consent form. Given the nature of the current study, which might elicit strong emotions in the participant, I decided that debriefing or supervision could potentially assist those participants who are negatively affected by participating in the study to deal with the emotional fall-out. Participants were asked to share any of their countertransference experiences of treating sexually abused children.

Results and interpretation

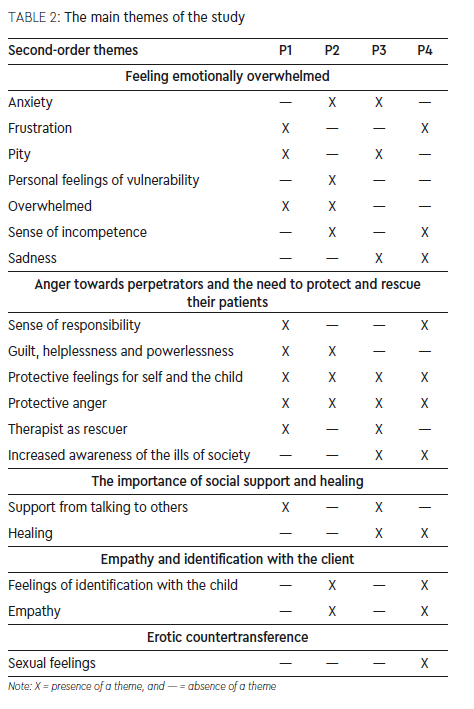

Participants were able to reflect on their emotional experiences by sharing their lived experiences of treating sexually abused children during the interview process, and subsequent emerging themes are illustrated by referring to the verbatim accounts from their original interview transcripts. Evidently, all participants appear to have experienced variable countertransference reactions in response to the transference material and behaviours of their patients. In total, 18 sub-themes emerged from the study and were categorised into five main themes. These 18 sub-themes and the five main themes are presented in Table 2. The five main themes are: a) feeling emotionally overwhelmed; b) anger toward the perpetrators and the need to protect and rescue their patients; c) the importance of social support and healing; d) empathy and identification with the client; and e) erotic countertransference.

Table 2 presents an analysis of all the participants' various sub-themes and the five main themes.

The five main themes generated from the original interview transcripts are discussed below.

Theme 1: Feeling emotionally overwhelmed

Participants in this study reported that they felt overwhelmed by the child's narrative of sexual abuse. As indicated in the literature (Possick et al., 2015; Wheeler & McElvaney, 2018), in the treatment of sexually abused children, most trauma psychotherapists experience a myriad of emotions and are often overwhelmed by the feelings evoked in them as well as the material presented by their patients. These emotions range from anxiety, sadness, frustration, a sense of pity and feeling overwhelmed, incompetent and vulnerable. Similarly, participants in this study described that they felt overwhelmed and emotionally overburdened while treating sexually abused children. These experiences are discernible in the following excerpts from the participants' interview transcripts:

...overwhelming, as I did not feel I could help her...I think it is definitely more challenging and draining...you are flooded by lots of graphic details. It is incredibly draining (Participant 1).

So, I was overwhelmed by my own feelings...the whole therapy was too overwhelming for me. There were moments where I felt dazed with a lump in my throat...I wanted to cry (Participant 2).

I hadn't expected how working with a sexually abused child would affect me. Initially, it was such an incredibly painful experience. I felt vulnerable, sad, powerless and hopeless. She was such a small child for what she had endured...traumatised in that way (Participant 4).

While the experience of feeling emotional burdened by the patients' material is not unique to psychotherapy with sexually abused children, it appears that the experience of being overwhelmed by their patients' material emanated from a variety of factors. These included listening to the details of the abuse, the therapists' inability to control the emotional pain evoked in them while listening to their patients and their inability to help their patients (Robinson-Keilig, 2014). Thus, most psychotherapists felt inadequate and confused about the feelings aroused in them, as they felt uncomfortable and were unsure of the impact that this may have on the therapy. This finding corroborates previous studies that found that trauma therapy often pushes the therapist past the limit of their training, thus creating shame, guilt, confusion and insecurity (VanDeusen & Way, 2006; Wheeler & McElvaney, 2018).

Theme 2: Anger toward perpetrators and the need to protect and rescue their patients

In listening to the details of childhood sexual abuse and exploitation of their patients, the psychotherapists reported experiencing feelings of anger and rage toward the perpetrators and society for failing to protect young children. Thus, most participants felt that they needed to protect and rescue their patients from re-experiencing the same trauma. Adopting the role of a rescuer is closely associated with parental countertransference, which manifests in the psychotherapist's wish to undo the harm and wound of sexual abuse (Maroda, 2010; Trepper & Barrett, 2013). Furthermore, the most conspicuous feelings among all the participants was that of anger towards the perpetrators of the abuse. This anger relates mainly to the fact that most therapists fail to comprehend how these perpetrators can inflict such pain on a child (Inji, 2001; Nissen-Lie et al., 2022).

In the same vein, the feelings of anger were further directed toward family members and legal guardians who, indirectly or unknowingly, had allowed the abuse to take place. For example, one of the participants was angry with the patient's parents for moving to Johannesburg and leaving the child in the care of a neighbour, who then sexually exploited the child. In another instance, a participant felt anger towards the mother of the sexually abused child for not believing that the abuse had taken place. These experiences correlate with the literature that asserts that there are various feelings that are provoked in the psychotherapist concerning child sexual abuse, including feelings of horror, outrage and disgust towards the perpetrators as well as feelings of rage towards the parents and members of society who allowed such behaviour to occur (Wilson & Lindy, 1994; Saakvitne, 2002). The following excerpts from the participants' interview transcripts resonate with the emotions listed above:

And the intensity of my own feelings of confusion, confusion as in wanting to help her and at the very same time, wanting to protect her from this and wanting to speak with her at the same time...I remember being gutted by feelings of anger and helplessness at the same time (Participant 1).

The anger obviously was directed at the boys who did this thing...There were times when I did not comprehend why someone would do that to a child. Therefore, my anger was how they could leave an eight-year-old girl all by herself..So that is where my anger comes from.I wanted to rescue her.The relationship that started developing was almost like a father-daughter relationship.I was inclined to want to rescue her. I wanted to fix these things. I wanted to make it right..to take her pain away. (Participant 4).

From the above interview excerpts, what stands out is how these therapists were angered and moved to feel and want to act in certain ways. This, therefore, begs the question if the psychotherapists' countertransference reactions of anger at the perpetrators, parents and society were transformed to facilitate therapeutic healing or it created a therapeutic impasse. While the patient's projections and projective identification could be useful therapeutically, the child's and therapist's emotions could be lost to the therapeutic process if psychotherapists resort to defensive blocking of traumatogenic projections (Loewenthal, 2018). Instead of using their patients' therapeutically, participants in this study seemed to have allowed their own countertransference feelings to stir up judgmental and humanistic positions about the circumstances surrounding the sexually abused patients (Wilson & Lindy, 1994; Shubs, 2008). For psychotherapists to discern when the therapeutic dyad undergoes intense change requires a certain ability to contain and hold and, most importantly, to process the patient's pain to advance therapeutic healing.

Closely linked to the experience of anger towards the perpetrators and the need to rescue the sexually abused children (negative and subjective countertransference) is the feeling of increased awareness of the ills of society or a sense of disillusionment with the world (Shubs, 2008). Some participants expressed their anger and inability to understand why people would intentionally harm innocent children, as can be seen in the excerpts below:

So, that first session was mind-blowing, it was difficult...I was left with lots of conflicting feelings inside me. I was so angry at her parents and felt disillusioned about the kind of life we are living in (Participant 2).

Even though I didn't know the perpetrator, I was filled with hatred.very tangible hatred and disgust at the person who violated this child sitting in front of me that day. I realised that it was not about me but the client, and my duty was to help her . I don't know if did help her though. (Participant 4).

The participants in this study were quite judgmental of the perpetrators and other members of their patients' families. This finding not only highlights their issues of parental countertransference, but also raises ethical dilemmas and issues of objectivity in trauma psychotherapy, especially in trauma psychotherapy with children (West, 2002; Neubauer et al., 2008). More specifically, it also raises the issue of psychotherapists being preoccupied with their own moral values at the expense of feeling with (being emotionally present with) their patients and providing a healing space for their patients (Tlali, 2016). The question that arises is whether these moralistic and judgmental reactions on the part of the psychotherapists facilitated or hindered the therapeutic process. This seems to be an ethical stance unconsciously adopted by therapists when treating sexually abused children. However, the therapists' explicit dilemma or inability to beneficially use their countertransference reaction as a facilitative weapon (Carnochan, 2001) in the therapeutic process can be regarded as part of the difficulties involved in communicating and using countertransference therapeutically and in way that aids the therapeutic relationship with children (Tlali, 2016; Horvath, 2018).

Theme 3: The importance of social support and self-healing

Working in isolation and a lack of professional and personal care are associated not only with vicarious traumatisation, but also with poor professional boundaries, fatigue and burnout (Jirek, 2015; Reddi, 2020). To mitigate and prevent the long-lasting effects of vicarious trauma experiences on the person of the therapist, literature on treating sexually abused and traumatised children advocate for therapists to nurture good personal and professional practices (Skovholt & Trotter-Mathison, 2016; Tlali, 2016). These self-care practices can include developing sound and supportive personal, social and professional support as well as maintaining a professional connection because these allow therapists to reflect on useful measures that support them in their daily interactions with child sexual abuse. These useful measures include internal resources, personal defences and external sources of support (Rasmussen, 2011). From the participant narratives, it became evident that they found it extremely helpful to speak to someone or to be in personal psychotherapy when treating sexually abused children. The participants in this study further added that they felt that by talking to others (either a supervisor or another therapist) they felt supported and guided and were able to reflect on their emotions in the here-and-now and how they were able to do things differently.

The feeling of wanting to rescue her and that is obviously a thing I can take to supervision. I often thought about this young girl when I am not at work, and it bothered me. As result, I became a little bit reserved and refrained from adopting the rescuer role (Participant 3).

...I think it is quite important to be in therapy when you are treating traumatised patients...especially survivors of interpersonal violence (Participant 2).

...It's also important..to discuss it with a colleague... so you get your own debriefing...that you don't veer off from the therapeutic process...you don't get your own stuff involved. You need to distance yourself from all these things we hear in our sessions.to be away and get a perspective of issues (Participant 1).

Another significant finding of this study is the experience of self-healing on the part of the psychotherapists treating sexually abused children. This is evident in the following excerpt:

...and because I didn't feel emotionally nurtured by my mother.I'm nurturing myself when I'm nurturing little girls. Moreover, little children who come in, it is re-nurturing the child in me, the inner child (Participant 4).

Here, participants felt that in helping sexually abused children they were able to work on their own unresolved experiences of childhood trauma. This finding was particularly pertinent to the two participants who had disclosed their own history of childhood sexual abuse. The experience of self-healing provides an insightful perspective on issues of countertransference reactions in the treatment of sexually abused children, now recognised in the trauma literature as vicarious post-traumatic growth (Malchiodi et al., 2008; Ulloa et al., 2016). This finding confirms the experiences of psychotherapists who treat sexually abused children in that, while other therapists find treating sexually abused children overwhelming and traumatic (Jirek, 2015; Possick et al., 2015; Wheeler & McElvaney, 2018), other studies have emphasised the positive experiences in the treatment of sexually abused children (Ulloa et al., 2016). The significance of the latter contention is associated with therapists' ability to use their countertransference in a way that is facilitative of the treatment process (Carnochan, 2001).

Theme 4: Feelings of empathy identification with the client

Empathic engagement with the patient's projections offers important therapeutic material and, in turn, the management of therapist's emotions is a significant treatment variable (Tlali, 2016). Of the four participants, two had revealed that they had been sexually abused as children and, as a result, both felt empathy towards the patients. These participants reported that treating these patients not only helped them to confront their own past traumas, but it also made them determined to help their patients. In identifying with the experiences of their patients, it appears that the participants were catapulted into revisiting their vulnerabilities. Ironically, it seems that as much as these participants were able to empathise with their patients, they were equally vicariously traumatised by treating these patients. At the risk of empathic exhaustion, participants disengaged from their work to focus of their own unresolved trauma experiences using these feelings of resonance as a therapeutic vehicle to facilitate healing in their patients. Overwhelming feelings elicited by the realities of child sexual abuse eroded the participants' ability to work effectively to such an extent that it seemed easier to rationalise the injustice of abuse:

...Because I have a history of childhood sexual abuse... it evoked lot of pain in me. My own vulnerability. My own sense of what sex is and how it manifests itself in my life, and I think those kind of feelings were, were just too much for me. I placed myself in her shoes and it felt horrible (Participant 4).

..I wanted to say, don't go any further, I understand what you're going through. Almost like I wanted to stand up, go to her and hug her or tell her things would be fine...But I couldn't do it...I think those kind of feelings were more in the therapeutic space to an extent it made me realise how much I have not dealt with my own issues (Participant 2).

By treating his patient, one of the participants (Participant 4) realised just how little he had worked through his own childhood sexual abuse trauma. The other participant (Participant 2) acknowledged that her own personal history of childhood sexual abuse motivated her to help her patient deal with the effects of sexual abuse trauma so that she (the patient) does not suffer from the devastating effects of childhood sexual abuse in her adult life. This is indicative of overidentification or a merger with the patient and points to poor processing of the patient's transference behaviour. Consequently, it seems to be consistent with the impediment (subjective) understanding of countertransference, described by Wilson and Lindy (1994) and Shubs (2008).

.I think the process of therapy itself was also compromised because I was too concerned about my own feelings, my own pain that she evoked in me. My own sexual feelings that she evoked in me. My own anger or feelings of justice or injustice that other people have inflicted on her (Participant 2).

These two participants reported that the experiences of treating sexually abused children prodded them to relive their own unresolved childhood sexual abuse (a retraumatisation) in the present therapeutic moment. As a result, this type of emotional resonance and the experience of retraumatisation propelled the participants to take some actions about their unresolved childhood trauma. One of the participants felt that it was her duty to assist her patient to overcome the effects of childhood sexual abuse. These findings are in keeping with most of the literature on therapists who share similar childhood histories of trauma with their patients (Saakvitne, 2002; Tlali, 2016).

Theme 5: Erotic countertransference

Erotic and/or sexual countertransference is a grave issue in treating sexually abused children. The literature states that these reactions occur because of either the therapist's fascination with the forbidden (Little, 2018), or the patient's transference behaviour (Alvarez, 2010). One male participant of the study (Participant 4, the only male participant in the study and one who had reported a childhood history of sexual abuse) experienced very disturbing erotic countertransference towards his patient. This participant reported that his sexual arousal in the therapeutic space was influenced by the way the patient sat (with her legs apart exposing her underclothes), and the fact that they were talking about the actual act of sexual abuse. He further reported that he felt uncomfortable, guilty, anxious and vulnerable upon experiencing some sexual feelings in the therapeutic space with a child patient. This participant also reported feeling powerless against these feelings, and he was worried that he may do something inappropriate with the patient.

It evokes sort of sexual feelings in me...sexual feelings which I could not place properly...Did I have sexual feelings for her or did I have sexual feelings because she was talking about sex? And my mind started running wild...So it was difficult for me to look anywhere, except look at her face (Participant 4).

From the excerpt above, it is evident that this type of countertransference reaction had a negative impact on the therapist's ability to focus on the issues at hand. Instead, he became preoccupied with containing his feelings and behavioural reactions rather than being emotionally available for his patient. Because of this negative countertransference reaction, the participant felt that he was not able to work with this patient and, consequently, he felt guilty and inadequate (Saakvitne, 2002). In this instance, the participant's erotic countertransference behaviour seems to have been triggered by the actual event (the way the patient sat) and characteristics that elicit the therapist's personal conflict (subjective countertransference - participant's unresolved childhood sexual trauma) (Wilson & Lindy, 1994; Alvarez, 2010). This finding corroborates Gelso (2011) and Loewenthal (2018) who asserted that most researchers tend to overlook the therapists' subjective experiences in the therapeutic relationship as a potential trigger for countertransference behaviour. Instead, they have a propensity for arguing that therapists' countertransference can largely be blamed on patient material or behaviour (Spillius & O'Shaughnessy, 2012). It is apparent that numerous factors present in the therapeutic relationships between therapists and their patients may trigger countertransference reactions in the person of the therapist.

Discussion

The present study sought to understand the utility and experiences of countertransference reactions of therapists who are treating sexually abused children. The present study has highlighted two important findings. Firstly, the study underlined variable utility and significance (or a lack thereof) of the psychotherapists' countertransference reactions and their impact both on the therapeutic process and the outcomes in the treatment of sexually abused children (Kiesler, 2001; Loewenthal, 2018). Secondly, the study has also emphasised the relatively ignored and taken-for-granted transference and countertransference experiences of therapists who treat child victims of interpersonal violence (Trepper & Barrett, 2013; Possick et al., 2015), as most therapists do not use the psychodynamic modality and/or lens when treating sexually abused children (Tlali, 2016). Thus, this calls into question whether or not transference and countertransference issues are pivotal in the treatment of sexually abused children or not. In other words, does all trauma treatment modalities include the processing of trauma therapeutic material and competence of these transference-countertransference grounds on the part of the psychotherapist?

Significantly, a clear demonstration of an inability to therapeutically use countertransference in the treatment of sexually abused children is evident in that one of the most frequent of the countertransference reactions experienced by the participants in this study was that of anger towards the perpetrators of the abuse. Anger towards family members and caregivers seen as indirectly responsible for allowing the abuse to take place was also commonplace. The experience of anger on the part of the therapist seems to be an unconscious defence against the overwhelming sense of powerlessness they felt in the therapeutic moment with the abused child. Wilson and Lindy (1994) and Shubs (2008) noted this form of countertransference reaction. The other most common countertransference reaction experienced by the participants was an overwhelming need to protect the abused child. Most participants of the study felt as though they needed to protect the child from having to re-experience the trauma that they had suffered. As a direct consequence of treating sexually abused children, some of the participants expressed that they at times felt powerless, helpless, sad and confused. These reactions are similar to the notion of parental countertransference suggested by Pearlman and Saakvitne (1995) as a type of behaviour that motivates therapists to abandon their therapist role in exchange for reacting as parents.

On the other hand, findings of the present study confirm previous research on the experience of post-traumatic growth, which was evident in the manner some participants were able to derive a sense of satisfaction at being able to empathise and use the empathy to expedite healing in their patients. These positive countertransference experiences have been characterised as post-traumatic growth in the literature (Ulloa et al., 2016). An example of a positive impact was seen in those instances where therapists' countertransference reactions enhanced their ability to empathise and identify with the plight of the patient. In this way, it can provide a holding and cathartic therapeutic space for sexually abused children. This was markedly the case for participants 2 and 4, who have both reported a history of child sexual abuse in their personal lives (Tlali, 2016).

As much as participants felt that they been able to demonstrate that while therapists with childhood histories of sexual abuse were more likely to experience post-traumatic growth in treating sexually abused children, it was equally evident that these therapists were more susceptible to the experience of retraumatisation and possible boundary violations (Saakvitne, 2002; Tlali, 2016). The therapists' experience of reliving their own unresolved feelings related to their own childhood sexual trauma (therapist's own unresolved issues) made them aware of the need to seek psychological help to deal with their own issues. Working with sexually abused children increased some of the therapists' awareness of the ills of society, resulting in a sense of disillusionment with the world.

The experience of erotic countertransference is not concerning. It is, in fact, the inability to process the erotic countertransference that is worrying and that can lead to poor therapeutic outcomes. This was true for the only male therapist with a childhood history of abuse. Evidently, this erotic countertransference reaction had a negative impact on the therapeutic process and resulted in the therapist feeling overwhelmed and guilty. This demonstrates the significance of erotic countertransference in the treatment of sexually abused children as this could easily slip into countertransference enactment (Kiesler, 2001). As indicated by studies by Saakvitne (2002) and Tlali (2016), countertransference enactments abound in therapeutic relationships where both the therapists and patients share a similar history of childhood trauma.

Conclusion

The results of this study raise both troubling and fascinating issues relating to the utility and experiences of countertransference in relation to the treatment of sexually abused children. This study highlights the complexities and controversies inherent in the understanding, manifestation and application of countertransference. Since its appearance in the psychoanalytic literature in the early 20th century (Freud, 1912) countertransference has been mired in controversy, with some classical proponents of this countertransference calling for its avoidance in psychotherapy, while contemporary proponents advocate for its therapeutic use (Kiesler, 2001). While the therapeutic utility of countertransference in the treatment of sexually abused children has become abundantly apparent in recent years, it has become evident that not all psychotherapists work from a psychodynamic perspective in the treatment of sexually abused children.

Several considerations for therapists treating sexually abused children are suggested. Firstly, therapists need to be aware of the unavoidability of transference and countertransference issues in any psychotherapeutic intervention with sexually abused children. Thus, therapists need to have some conceptual understanding of transference and countertransference dynamics to be able to discern their enactments in the therapeutic encounter. This conceptual understanding will also enable therapists to utilise countertransference reactions in a manner that is facilitative rather than obstructive to the therapeutic process. In the South African context, with its high rates of child sexual abuse, there is a clear need to train therapists in different trauma treatment models to create capacity (a psychology workforce) of specialist trauma therapists. Lastly, there is also a need for regular and mandatory group and individual supervision for therapists registered as trauma therapists.

Limitations

While the current study added to the theoretical knowledge concerning countertransference reactions in the treatment of sexually abuse children, it also has its limitations. The limitations relate to the limited number of participants, using only white participants and therapists who neither utilise psychodynamic modality as their preferred therapeutic intervention nor regard themselves as trauma therapists.

Directions for future research

Notwithstanding the emergence and dominance of the multiplicity of trauma treatment interventions in the few decades, psychoanalytic-oriented therapeutic interventions remain central to the treatment of sexually traumatised children. Their potency and relevance lie in their ability to work with a variety of unsymbolised, unconscious intrapsychic and relational dynamics that pattern the sexually traumatised child's transference

behaviour. Having considered the limitations of this study, I would recommend that future research should be conducted on the needs of therapists and ways to offer professional support to therapists of sexually abused children. Future research should be conducted with relatively larger and more diverse samples of trauma psychotherapists who also have insight and knowledge of the centrality of not only understanding, but also have the expertise to constructively use the psychodynamic notions of transference-countertransference in trauma therapy. Future research should be conducted to seek ways in which clinical supervision and personal therapy can become a supportive structure and resource for trauma therapists.

References

Alvarez, A. (2010). Types of sexual transference and countertransference in psychotherapeutic work with children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 36(3), 211-224. https://doi.org/10.1080/0075417X.2010.523815 [ Links ]

Aron, L. (2007). The tree knowledge: Good and evil. In M. Suchet, A. Harries & L. Aron (eds), Relational Psychoanalysis: Vol. 3. (pp. 5-32). Mahwah: The Analytic Press. [ Links ]

Atlas, G. (2015). Touch me, know me: The enigma of erotic longing. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 32, 123-139. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037182 [ Links ]

Barua, A., & Das, M. (2014). Phenomenology, psychotherapy, and the quest for intersubjectiveness. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 14,109-119. [ Links ]

Benatar, M. (2000). A qualitative study of the effect of a history of childhood sexual abuse on therapists who treat survivors of sexual abuse. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 1(3), 9-28. https://doi.org/10.1300/J229v01n03_02 [ Links ]

Brockhouse, R., Msetfi, R. M., Cohen, K., & Joseph, S. (2011). Vicarious exposure to trauma and growth in the therapist: The moderating effects of sense of coherence, organizational support and empathy. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(6), 735-742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20704 [ Links ]

Carnochan, P. G. M. (2001). Looking for ground: Countertransference and the problem of value in psychoanalysis. The Analytic Press. [ Links ]

Cooper, S. H. (2010). A disturbance in the field: Essays in transference-countertransference engagement. Routledge. [ Links ]

Cooper, S. H. (2014). The things we carry: Finding/creating the object and the analyst's self-reflective participation. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 24, 621-636. https://doi.org/10.1080/10481885.2014.970963 [ Links ]

Courtois, C. A. (2010). Healing the incest wound: Adult survivors in therapy (2nd edn). W. W. Morton and Company. [ Links ]

Courtois, C., & Ford, J. (2009). Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence based guide. Guilford. [ Links ]

Crocket, K. (2014). Ethics and practices of re-presentation: Witnessing self and other. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 14(2), 154-161.https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2013.779733 [ Links ]

Eagle, M. N. (2011). From classical to contemporary psychoanalysis: A critique and integration. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203868553 [ Links ]

Freud, S. (1910). The future prospects of psychoanalysis. In J. Strachey (ed. & trans.), The Standard Edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, (Vol. 11, pp. 139-151). Hogarth Press. [ Links ]

Freud, S. (1912). Recommendations to physicians practicing psychoanalysis. In J. Strachey (ed. & trans.), The Standard Edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 12, pp. 109-120). Hogarth Press. [ Links ]

Gadamer, H. G. (1960). Truth and method. Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Gelso, C. J. (2011). The real relationship in psychotherapy: The hidden foundation of change. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12349-000 [ Links ]

Gelso, C., & Hayes, J. (2007). Countertransference and the therapist's inner experience. Lawrence Erlbaum & Associates. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203936979 [ Links ]

Gemignani, M. (2011). Between researcher and researched: an introduction to countertransference in qualitative inquiry, Qualitative Inquiry, 17(8), 701-708. [ Links ]

Gibson, S., & Hugh-Jones, S. (2012). Analysing your data. In C. Sullivan, S. Gibson, & S. Riley, (eds), Doing your qualitative psychology project (pp. 127-153). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473914209.n7 [ Links ]

Greenberg, J., & Mitchell, S. A. (1983). Object relations in psychoanalytic theory. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjk2xv6 [ Links ]

Grondin, J. (2002). Gadamer's basic understanding of understanding. In R. J. Dostal (ed.), The Cambridge companion to Gadamer (pp. 36-51). Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Heiman, P. (1950). On countertransference. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 31, 81-84. [ Links ]

Hennissen, V., Meganck, R., Van Nieuwenhove, K., Krivzov, J., Dulsster, D., & Desmet, M. (2020). Countertransference processes in psychodynamic therapy with dependent (Anaclitic) Depressed patients: A qualitative study using supervision data. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 48(2), 170-200. https://www.researchgate.net.publication/342765391 [ Links ]

Holmes, J. (2014). Countertransference in qualitative research: A critical appraisal. Qualitative Research, 14(2), 166-183. https://doi.org/10:1177/1468794112468473 [ Links ]

Hooker, C. (2015). Understanding empathy: why phenomenology and hermeneutics can help medical education and practice. Medical Health Care Philosophy 15(18), 541-552. [ Links ]

Horvath, A. O. (2018). Research on the alliance: Knowledge in search of a theory. Psychotherapy Research, 28(4), 499-516. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1373204 [ Links ]

Howitt, D., & Cramer, D. (2017). Research Methods in Psychology (5th edn). Pearson. [ Links ]

Inji, R. (2001). Countertransference, enactment, and sexual abuse. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 27(3), 285-301. https://doi.org/10.1080/00754170110087568 [ Links ]

Jirek, S. L. (2015). Soul pain: the hidden toll of working with survivors of physical and sexual violence, Sage Open, 5(3), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015597905 [ Links ]

Jorgenson, L. (1995). Countertransference and special concerns of subsequent treating therapists of patients sexually exploited by previous therapist. Psychiatric Annals, 25(9), 525. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-19950901-04 [ Links ]

Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms, In M. Klein, P. Heimann, S. Isaacs, & J. Riviere (eds), Developments in Psycho-Analysis Hogarth Press. [ Links ]

Kluft, R. P. (2011). Ramifications of incest. Psychiatric Times, 27(12), 12 January. www.psychiatrictimes.com/sexual-offenses/ramifications-incest [ Links ]

Little, R. (2018). The management of erotic/sexual countertransference reactions: An exploration of the difficulties and opportunities involved. Transactional Analysis Journal, 48(3), 224-241. https://doi.org/10.1080/03621537.2018.1471290 [ Links ]

Loewenthal, D. (2018) Countertransference, phenomenology and research: Was Freud right? European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 20(4), 365-372, https://doi.org/10.1080/13642537.2018.1534676 [ Links ]

Luyten, P. (2017). Personality, psychopathology, and health through the lens interpersonal relatedness and self-definition. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 65(3), 473-489. https://doi:.org/10.1177/003065117712518 [ Links ]

Malchiodi, C. (2016). Expressive arts therapies and posttraumatic growth expressive arts are changing the story of recovery. Psychology Today, 27 September. https://www.psychologytoday.com/za/blog/arts-and-health/201609/expressive-arts-therapies-and-posttraumatic-growth [ Links ]

Malchiodi, C., Steele, W., & Kuban, C. (2008). Resilience and posttraumatic growth in traumatized children. In C. Malchiodi (ed.), Creative interventions with traumatized children (pp. 285 - 301). Guilford. [ Links ]

Mann, D. (1997). Psychotherapy: An erotic relationship of transference and countertransference passions. Routledge. [ Links ]

Maroda, K. J. (2004). The power of countertransference: Innovation in analytic technique. Psychology Press. [ Links ]

Maroda, K. J. (2010). Psychodynamic technique: Working with emotions in the therapeutic relationship. Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Morrissette, P. (1999). Phenomenological data analysis: A proposed model for counsellors. Guidance and Counselling, 15(1), 2-7. [ Links ]

Murray, L. K. & Nguyen, A., & Cohen, J. A. (2014). Child sexual abuse. Child, Adolescent, Clinical Psychiatry in America, 23(2), 321-337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2014.01.003 [ Links ]

Neubauer, B. E., Witkop, C. T., & Varpio, L. (2019). How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspective Medicine Education, 8, 90-97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2 [ Links ]

Nieuwenhuis, J. (2015). Qualitative research designs and data gathering techniques. In K. Maree (ed.), The First Steps in Research (pp. 70-97). Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Nissen-Lie, H. A., Dahl, H. J., & H0glend, P. A. (2022). Patient factors predict therapists' emotional countertransference differently depending on whether therapists use transference work in psychodynamic therapy, Psychotherapy Research, 32(1), 3-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1762947 [ Links ]

Orbach, S. (2014). Democratizing psychoanalysis. In D. Loewenthal, & A. Samuels (eds), Relational psychotherapy, psychoanalysis and counselling: Appraisals and reappraisals (pp. 12-26). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315774152-2 [ Links ]

Pearlman, L. A., & Saakvitne, K. W. (1995). Trauma and therapist: Countertransference and vicarious traumatization in psychotherapy with incest survivors. W. W. Norton & Company. [ Links ]

Pistorius, K. D., Feinauer, L. L., Harper, J. M., Stahmann, R. F., & Miller, R. B. (2008). Working with sexually abused children. American Journal of Family Therapy, 36, 1-15. https://doi.org/10:1080/019261807011291204 [ Links ]

Possick, C., Waisbrod, N. & Buchbinder, E. (2015). The dialectic of chaos and control in the experience of therapists who work sexually abused children. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 24, 816-836. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2015.1067667 [ Links ]

Qutoshi, S. B. (2018). Phenomenology: A philosophy and method of inquiry. Journal of Education and Educational Development, 5(1), 215-222. https://doi.org/10.22555/joeed.v5i1.2154 [ Links ]

Racker, H. (1957). The meanings and uses of countertransference. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 26(3), 303-357. https://doi.org/10.1080/21674086.1957.11926061 [ Links ]

Racker, H. (1968). Transference and countertransference. The Hogarth Press. [ Links ]

Rasmussen, B. (2011). The effects of trauma treatment on the therapist, In S. Ringel, & J. R. Brandell (eds), Trauma: Contemporary directions in theory practice and research (pp. 48-67). Sage. [ Links ]

Reddi, D. (2020). Exploring the experiences of South African psychologists' use of self-care practices: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Unpublished MA thesis, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Reich, A. (1960). Further remarks on countertransference. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 41, 380-395. [ Links ]

Robinson-Keilig, R. A. (2014). Secondary traumatic stress and disruptions to interpersonal functioning among mental health therapists. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(8), 1477-1496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513507135 [ Links ]

Saakvitne, K. W. (2002). Shared trauma: Therapist's increased vulnerability. Psychoanalytic Dialogue: The International Journal of Relational Perspectives, 12(3), 443-449. https://doi.org/10.1080/10481881209348678 [ Links ]

Safran, J., & Muran, J. (2000). Negotiating the therapeutic alliance. Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Sheinberg, M., & Fraenkel, P. (2001). The rational trauma of incest: A family- based approach to treatment. The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Shubs, C. (2008). Treatment issues arising in working with victims of violent crime and other traumatic incidents of adulthood. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 25(1), 142-155. https://doi.org/10.1037/0736-9735.25.1.142 [ Links ]

Skovholt, T. M., & Trotter-Mathison, M. (2016). The resilient practitioner: Burnout and compassion fatigue prevention and self-care strategies for the helping professions (3rd edn). Routledge. [ Links ]

Slakter, E. (1987). Countertransference. Jason Aronson. [ Links ]

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2013). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method, and research. Sage. [ Links ]

Spillius E., & O'Shaughnessy, E. (2012). Projective Identification: the fate of a concept. Routledge. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa (StatsSA). (2016). Community Survey 2016, Statistical release P0301 / http://cs2016.statssa.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/NT-30-06-2016-RELEASE-for-CS-2016-_Statistical-releas_1-July-2016.pdf [ Links ]

Stefana, A. (2017). History of countertransference. From Freud to the British object relations school. Routledge. [ Links ]

Stern, D. B. (2010). Partners in thought: Working with unformulated experience, dissociation and enactment. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203880388 [ Links ]

Stuthridge, J. (2015). All the world's a stage. Transactional Analysis Journal, 45(2), 104-116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0362153715581174 [ Links ]

Teherani, A., Martimianakis, T., Stenfors-Hayes, T., Wadhwa, A., & Varpio, L. (2015). Choosing a qualitative research approach. Journal of Graduate Medicine Education, 7, 669-670. [ Links ]

Tlali, T. (2016). Countertransference reactions of incest survivor therapists in psychotherapy with adult incest survivor patients: An interpretive phenomenological analysis. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Trepper, T. S., & Barrett, M. J. (2013). Treating incest survivors: A multiple systems perspective. Routledge. [ Links ]

Tubert-Oklander, J. (2013). Theory of psychoanalytical practice: A relational process approach. Karnac. [ Links ]

Tuffour, I. (2017). A critical overview of interpretative phenomenological analysis: a contemporary qualitative research approach. Journal of Healthcare and Communication, 2(4), 1-5. [ Links ]

Ulloa, E., Guzman, M. L., Salazar, M., & Cala, C. (2016). Posttraumatic growth and sexual violence: A literature review. Journal of Aggression and Maltreatment Trauma, 25, 286-304. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2015.1079286 [ Links ]

VanDeusen, K. M., & Way, I. (2006). Vicarious trauma: an exploratory study of the impact of providing sexual abuse treatment on clinicians' trust and intimacy. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 15(1), 69-85. https://doi.org/10.1300/J070v15n01_04 [ Links ]

Walters, D. A. (2009) Transference and countertransference as existential themes in the psychoanalytic theory of W. R. Bion. Psychodynamic Practice, 15(2), 161-172. https://doi.org/10.1080/14753630902811367 [ Links ]

Wekerle, C., Wolfe, D. A., Cohen, J. A., Bromberg, D. S., & Murray, L. (2019). Childhood Maltreatment (2nd edn). Hogrefe Publishers https://doi.org/10.1027/00418-000 [ Links ]

West, W. (2002). Some ethical dilemmas in counselling and counselling research. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 30(3), 261-268, https://doi.org/10.1080/0306988021000002308 [ Links ]

Wheeler, A. J. & McElvaney, R. (2018). The positive impact on therapists of working with child victims of sexual abuse in Ireland: A thematic analysis. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 31(4), 513-527. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2017.1336077 [ Links ]

Wickham, R. E., & West, J. (2002). The therapist's experience of working with abused children In R. E. Wickham & J. West (eds), Therapeutic work with sexually abused children (pp. 40-50). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446220474.n4 [ Links ]

Williams, D. I., & Irving, J. A. (1995). Theory in counselling: using content knowledge. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 8(4), 279-289. [ Links ]

Wilson, J. P., & Lindy, J. D. (1994). Empathic strain and countertransference. In J. P. Wilson & J. D. Lindy, (eds), Countertransference in the treatment of PTSD (pp. 5-30). Guildford Press. [ Links ]