Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology

On-line version ISSN 1445-7377

Print version ISSN 2079-7222

Indo-Pac. j. phenomenol. (Online) vol.20 n.1 Grahamstown Aug. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20797222.2020.1850489

Facing challenges and drawing strength from adversity: Lived experiences of Tibetan refugee youth in exile in India

Kiran Dolly Sapam; Parisha Jijina

Dept of Psychology, Faculty of Education & Psychology, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara, India

ABSTRACT

The current study is a qualitative investigation aimed at exploring the lived experiences of Tibetan youth who had escaped to India as unaccompanied minors and since then have been living as refugees in India without their parents. The study attempts to explore the challenges, struggles and coping of this unique population of youth refugees growing up in exile in India without the support of parents. Ten Tibetan refugee youth now studying at university level were interviewed in depth. Interpretative phenomenological analysis was used to analyse their narratives. Major findings included the unique sociocultural, political and emotional challenges they faced related to acclimatisation, status of their own political identity, difficulties pertaining to retaining their Tibetan culture in a host country, and loneliness. Their adaptation in the host country was perceived to be facilitated by their unique Buddhist spiritual and cultural beliefs, strong faith in the Dalai Lama, community bonding and peer support and the use of social media to communicate with family in Tibet. The Tibetan refugee youth derived a sense of growth from their adversities related to appreciating the value of family, personal growth in the form of self-reliance, and finding meaning in life by feeling part of a larger purpose related to the Tibetan cause. Implications for practice: The study highlights the unique psychosocial issues of Tibetan refugee youth in exile in India. Culturally sensitive psychosocial support and an understanding of traditional spiritual and religious coping mechanisms may be integrated into health services for the Tibetan refugees who lack family support and may not be familiar with the Western constructs of mental health.

Keywords: challenges of Tibetan refugees; coping of Tibetan refugees; interpretative phenomenological analysis; Tibetan refugee

Introduction

The Tibetan saga of displacement began more than seventy years ago when Tibet was occupied by China and the Tibetan spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, escaped to India. Through the invasion of Tibet in 1950, the People's Republic of China gained control of Tibet. Amidst tense co-existence with the Chinese authorities and fearing a danger to his life, the Dalai Lama escaped to India in March 1959. The then Prime Minister of India, Mr Jawaharlal Nehru, assisted by providing refugee settlements in several states of India (Norbu, 2001). The Tibetans have since established a government in exile in India known as the Central Tibetan Administration.

Every year, 2 000 to 2 500 Tibetans attempt to escape to settlements in India and Nepal due to political, religious and cultural oppression, and for education (Sachs et al., 2008). The journey from Tibet to India can take several days to months as it involves crossing high mountainous pathways. En route, many experience frostbite, hypothermia, snow blindness and also risk prosecution at the hands of border patrols. A growing number of unaccompanied Tibetan minors are migrating to India. The United Nations (2005) defines an unaccompanied minor as a person who is under the age of eighteen, and who is separated from both parents and is not being cared for by an adult who by law or custom has responsibility to do so. Bernstorff and von Welck (2004) reported that 90 per cent of Tibetan refugee children and adolescents were unaccompanied by their parents. Some of the main reasons reported for Tibetan children to leave their homeland are to secure modern education in exile and to keep alive the Tibetan culture and language which are at risk of extinction in their own homeland (Yankey & Biswas, 2012).

Being a refugee in an alien country is one of the toughest experiences a child can endure, and enduring this without one's parents is even tougher. During the migration process, unaccompanied minors are subject to a range of extreme hardships such as strenuous living conditions, high levels of uncertainty and insecurity, and the threat of detention (Derluyn & Broekaert, 2005). A study of unaccompanied refugee children in the Netherlands showed that they had experienced significantly more traumatic events such as sexual exploitation and violence than minors accompanied by their parents (Bean et al., 2007). On arrival in their host country, unaccompanied minors are at a greater risk of developing psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, externalising and behavioural problems (Bean et al., 2007; Derluyn et al., 2009; Vervliet et al., 2014). The presence of social support networks after arrival in a host country was a major predictor for positive mental health as reported in a study on unaccompanied refugee minors from Syria and Afghanistan (Sierau et al., 2018). The education and care that unaccompanied minors receive during the first years after resettlement, and their own drive to create a positive future, have also been reported as key predictors in their mental health and adjustment (Eide & Hjern, 2013).

In a study on Tibetan refugee children in India, Servan-Schreiber et al. (1998) reported that out of 61 randomly selected children, 11.5% of the children met the diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and for major depressive disorder. Similarly, in a study of 76 Tibetan students in a refugee camp in India, Terheggen et al. (2001) found that 35% of the respondents met the criteria for emotional distress, 25% had high scores on anxiety, with another 42% meeting the criteria for depression. Dolma et al. (2006) also reported that many Tibetan refugees making their journey across the border suffer serious physical injuries resulting from the difficult passage across the Himalayas and threatening encounters with patrol authorities. Among the Tibetan refugees in exile in India, Hussain and Bhushan (2009) reported three clusters of traumatic experiences, in terms of survival trauma (such as scarcity of food, medical facilities, unemployment), ethnic trauma (loss of unique culture and identity, destruction of a place of worship) and deprivation uncertainty (such as feelings of deprivation, uncertainties of future).

Despite half a century-long exile, the Tibetan community has adapted well, has managed to preserve their cultural identity and has a functioning administration in exile in India. Studies have shown that among the Tibetan refugees, cultural beliefs related to Buddhism play a significant role in coping and mediating psychological distress (Sachs et al., 2008; Hussain & Bhushan, 2011). Introduced in the seventh century, Tibetan Buddhism is strongly rooted in a system of lamas and monasteries. The lamas are their spiritual leaders and significant among them is the Dalai Lama, who is the 14th of this name. The Buddhist philosophy and culture followed by the Tibetans allow for a range of helpful coping resources. The core Buddhist philosophy that suffering comes from one's mind, rather than as a consequence of external events and the belief in compassion, may moderate the experience of psychological distress (Hooberman et al., 2010). In this regard, Tibetans have been reported to have comparatively low psychological distress even after multiple traumatic experiences and have been cited as models of successful coping with refugee life (Mahmoudi, 1992). Lewis (2013) found that members of the Tibetan community in exile discouraged each other from dwelling on difficulties and sharing distressing experiences, but rather encouraged one another to move forward even in the light of personal histories of violence.

Voulgaridou et al. (2006) have highlighted that even when refugee families leave their country of origin, their culture and support system, they do not leave their abilities to overcome emerging adversities. Experiencing trauma may even facilitate psychological growth among certain individuals and have a transformational role which is known as post-traumatic growth (PTG). Tedeschi and Calhoun (2004) refer to PTG as a positive psychological change experienced as a result of enduring psychological struggle with major life crises or traumatic events. Post-traumatic growth tends to be reported in five main areas: perception of new possibilities; enhanced relating to others; discovery of personal strengths; spiritual changes; and an enhanced appreciation of life (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). In a study on twelve Tibetan refugees who had faced adverse life experiences, Hussain and Bhushan (2013) reported post-traumatic growth in the areas of the realisation of personal strengths, the experience of more intimate and meaningful relationships and positive changes in outlook toward the world.

Aim

The current study is a qualitative investigation aimed at exploring the lived experiences of Tibetan youth who have escaped to India as unaccompanied minors and since then have grown up and are living as refugees in exile in India without their parents. The study aims to explore in depth the unique challenges, struggles, and coping of this unique population of youth refugees growing up in exile in India without the support of parents.

Materials and methods

Methodology

A qualitative research methodology was adopted to extract the rich, lived experiences and complexities of the struggles and challenges faced by this unique population of refugees. For the purpose of the present study, interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) was adopted to explore the lived experiences of the participants and the meaning that they themselves attached to their experiences.

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) follows the phenomenological approach wherein the focus is on the embodied and experiential meanings and the rich description of a phenomenon as it is lived by an individual (Finlay, 2009). An important theoretical process included in IPA is hermeneutics (theory of interpretation). Smith and Osborn (2003) describe IPA as a phenomenological approach that attempts to explore personal experience and is concerned with an individual's subjective perception or interpretation of an event. Additionally, IPA recognises the researcher's role in the interpretation of the participant's subjective account. According to IPA, access to the participant's subjective world is possible through the process of the researcher's interpretive activity. Thus, in a broad sense, IPA entails two stages of an interpretation process or double hermeneutic, one where the participant interprets their inner world and in the other where the researcher interprets how the participants made sense of their experiences.

IPA is also referred to as an idiographic case approach. The idiographic nature of IPA allows for more focus on the individual, and a detailed account of the unique experiences and meaning making of a small group of individuals rather than attempting to create generalisations (Smith et al., 1999). Within the above context, IPA was chosen as the appropriate methodological approach suiting the aims of the current research.

Participants

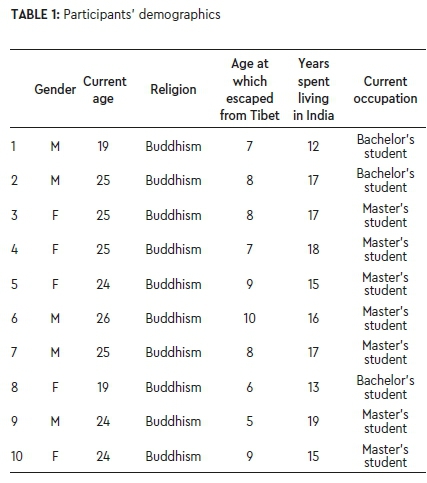

A total of eleven Tibetan refugees studying at a university in Gujarat were initially contacted. Selection of the participants for study had been done through purposive sampling with the aid of the Tibetan student body in the state of Gujarat. The eleven participants were informed about the objectives of the study. One participant did not wish to take part in the study and hence the interviews were conducted with ten Tibetan youth who gave their consent (five males and five females). The mean age of the participants was 23 years (SD 2.46).

All the participants were born in Tibet and had escaped to India as unaccompanied minors at the mean age of around seven years, hoping for a better life, for the purpose of attaining a good education and for the freedom to practise their religion. Owing to the precarious geopolitical situation in Tibet, all the participants reported that they have not been able to meet their parents even once since they had escaped. The only contact with their parents was over the phone and the few social media apps which are permitted in Tibet. The homogenous composition of the participant group is shown in Table 1.

Setting and data collection

The interview with each participant was conducted individually and face to face by the first author. The interviews were conducted in informal settings to allow for an easier and relaxed flow of thoughts and feelings. For the female participants, the interviews took place at their hostel room or rented accommodation. For the male participants, an outdoor and quiet place within the university premises was chosen, keeping in mind the cultural gender norms in India. With prior permission, all the interviews were audio recorded. Before each interview, time was spent in building trust and rapport. Each interview lasted for around 40-120 minutes (which does not include the time spent forming a good rapport) and the average duration of the interview was 60 minutes. All the interviews were conducted in English as the participants were well-versed in it and concluded in one meeting.

Instruments

A semi-structured interview schedule was constructed by the authors for the data collection. In accordance with the recommendations of IPA, the questions were non-directive and open-ended to allow participants to fully explore and share their experiences. The questions were framed to be free of technical jargon, leading content or assumptions. The semi-structured interview schedule also allowed for opportunities to follow the participant's interest or concerns which were not included in the schedule. The researcher relied on clarifying the meaning derived by the participants of a topic described with prompts such as 'What did that mean for you?', 'How did you experience that?', or 'What was that like for you?'.

The interview questions focused on understanding the participants' life history, challenging life experiences living as a refugee in India without the support of their parents, their adaptation process, the changes they experienced after leaving Tibet and the meanings they assigned to these changes. Examples of a few of the questions which were used to explore the aforementioned areas include: 'Could you tell me something about your experience of escaping Tibet?'; 'Tell me about your experience of living here in India?'. After the interview schedule was prepared, it was sent for expert validation and to check the sensitivity of the questions to a senior monk and academician in New Delhi who is a source of guidance and support for the Tibetan youth and is well-versed with their struggles. His feedback was then incorporated into the interview schedule.

Data analysis

The interview data were transcribed verbatim and the data was analysed using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) with the guidelines provided by Smith and Osborn (2003). The transcripts of the interviews were reread many times to become familiar with the data. The left margin was utilised to annotate the significant aspects of what the participant said, and the first author made initial analytical notes and comments for the entire transcript. The other margin was then utilised to write down emerging themes. The emerging themes elevated the participant's response to a slightly higher level of abstraction and at times included psychological terminology. The first author derived the themes; however, discussions with the second author served as a means to ensure that the interpretations accurately reflected and were grounded in the responses of the participant.

As analysis continued, attempts were made to make meaning and find connections out of the themes that emerged in a more theoretically relevant sense. As the clustering of themes emerged, it was checked in the transcript to ensure that the connections were relevant to the raw data - the actual responses of the participant. Thereafter, superordinate themes and their subthemes were identified by exploring the connections and clusters of the emergent themes. During this process, certain themes which were not very rich and in coherence with the transcript were dropped. In this manner, a list of themes was prepared for each of the ten participants. Once all the transcripts were analysed by the interpretative process, a consolidated list of master themes was produced for the group (10 participants) by combining and reorganising themes of all the participants cases. The master list of themes was not selected solely on the basis of their frequency within the data. Additional factors, such as the richness of the theme and how the theme helped in highlighting significant aspects of the participants response were considered. Finally, a narrative account of the participant's experiences along with the authors' interpretation interspersed with verbatim extracts from the transcripts was written up.

Findings

Narrative accounts of the participants showed that they faced many challenges from a young age. A few of the significant factors perceived as aiding their adaptation in the host country were elaborated by the participants. Many participants perceived growth in themselves and derived a higher meaning from their adversities. The main themes derived from the study have been illustrated in Figure 1.

Perceived challenges and struggles

The initial part of the interview focused on the experiences of the participants as refugees in India. Responses echoed the way that the geoclimatic environment in the host country was drastically different from their home country, making it difficult to adjust initially. Tibet is at a higher altitude than India and consists of some of the highest mountains in the world including the Himalayas. It has a very cool climate, which is in stark contrast with the humid weather of India. Despite leaving their homeland at an early age, many of them were able to give vivid recollections of their adjustment difficulties. One participant recollected:

The air in Tibet is very clean. The sun is also not very harsh. But here in India, we found it very hard to adjust especially when we first came. The pollution level is also very high. Many die after reaching India from Tibet due to the exhaustion and extreme heat.

Along with the climate, the issue of the drastic change in diet was reported as distressing. The transition from eating a simple boiled Tibetan diet to the spicy Indian food had resulted in ulcers in a few of the participants. A participant mentioned being malnourished from refusal to eat Indian food upon arrival and with a lowered immunity, he got infected with tuberculosis.

The participants shared another challenging struggle related to racism. The Tibetans as such have facial features that are not Indian. And most of the participants reported being teased or made fun of their facial features. Indian citizens belonging to the north-eastern states such as Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh have also reported being teased about their features when they go to other parts of India.

The participants escaped Tibet around the mean age of seven, an age at which a child is not emotionally nor cognitively equipped to deal with the challenges of being displaced in an alien country without the love and support of parents. The participants had foster parents and caretakers who looked after them while they were in school, but all the participants reported feelings of deprivation and loneliness as they were without their families in a foreign land. One participant explains very clearly in a few words the pain and feelings of deprivation:

The centres took full care of all our basic needs. But the children with parents regularly had new clothes and toys and they also went home every vacation. But children like me whose parents were in Tibet, stayed in the school the whole year round…

Another participant echoes the same sentiment:

I had no money, no proper clothes to put on (in the initial period of just settling down in India). But there are other kids who had. When I looked at them, I felt very deprived. Because we were not mentally mature. Even though new clothes don't really matter, but we were teenagers so that mattered then. So, that is how I encountered my childhood…

The refugee children also felt isolated as they could not call their parents very often because international telephone calls were very expensive a decade ago. Many participants mentioned that the Tibetan centres started having a dedicated telephone line for calling Tibet after international telephone calls got cheaper and more accessible.

The participants mentioned that as they are refugees in exile in India, the lack of full citizenship in India also causes difficulties in daily life such as when trying to rent rooms, or setting up a small business. The processes and paperwork become much longer and more tedious. One participant narrated a story about when he was nearly thrown out of the train because the train conductor did not recognise the identity card that the Tibetans were given. His college identity card saved him from trouble. Apart from this, there is a constant fear of whether the new ruling political party in the country will be supportive of the Tibetan cause in their new policies. Further, one participant mentions how international relations affect the Tibetan cause:

The support we receive from the Indian government is so much. But, if you look at the policies of some of the political parties, it may seem quite distant. To maintain a good relationship with the neighbouring country, they may have to compromise our issue…

Concerning a question inquiring about the struggle they are facing at the moment, there was a common response. The struggle was whether to go for further studies, and the issue of funding. Financial struggles are prevalent as most of their families in Tibet are simple farmers. Most of the Tibetan students currently studying in India are beneficiaries of scholarships from the Dalai Lama trust funds and sponsors around the world. Although the Tibetans get sponsorships for their education, the participants mentioned that they still face difficulty in procuring admission to professional courses such as medicine and engineering. There is a pressure to get a job quickly as they have to stand on their own feet, so continuing higher education is not an easy task. One participant mentions:

I did not have the luxury of exploring what I want to do after high school because I've to quickly start planning for the next step that is to get a job. It is easier for people who have a family to lean back on.

In the present, all the participants mentioned worries related to their home country Tibet. Faith and devotion are the striking features of Tibetan culture. Almost every aspect of life is shaped by Buddhist worldviews and beliefs. A major concern for the participants was about their Tibetan culture getting diluted and dissolved in the host country, and of losing their traditions. As one participant elaborated:

There is a constant fear of losing our culture and tradition. For the youngsters due to influence from the other youngsters and the pop culture, this tradition of wearing traditional dress on special days is no longer strictly followed.

There is also the concern reported over the loss of usage and fluency in the Tibetan language among the refugees. Some excerpts from the interview reflect this succinctly:

There is the use of cocktail language - Tibetan, English, and Hindi, in casual conversations among young Tibetans. They feel more comfortable conversing in Hindi. As other people look at you weirdly if you speak pure Tibetan in front of them…

All the participants mentioned the deep-rooted worry of losing the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama has stepped down as the Tibetan political leader, but the Tibetan people still consider him important for all their political developments. There is also the concern and anxiety regarding the appointment of a new religious authority. As seen in the words of one participant,

the issue I always worry about is the Dalai Lama. He is 80 years old. Who is going to lead the people? He is the sole person on this Earth who can unite all Tibetans.

Worries and anxieties about sustaining the Tibetan cause were also highlighted and can be felt in the words of one of the young participants:

If we don't sustain our struggle, after 40 or 50 years, we won't be able to sustain our identity. His Holiness, the Dalai Lama is synonymous with Tibet. So, once he is gone, the Tibetan issue will be in a very difficult situation.

Another issue that the participants reported was the struggle to keep motivating oneself to continue the fight for the identity and independence of Tibet. Resentment was noted for those who have become citizens of their host country. One respondent mentions:

I have to make conscious efforts to keep the struggle alive and not get too comfortable living in a host country. I can see many who have given up the struggle and taken up citizenship of their host countries. But if many keep doing so, there will be no Tibet left one day…

To summarise, the Tibetan youth have faced a range of struggles living in exile in India, ranging from acclimatising to the food and climate, to educational and financial struggles, challenges related to sustaining the Tibetan struggle and retaining their identity in a host country. The next section focuses on the adaptation and coping process during the struggles and challenges.

Coping and adaptation to refugee life

A common theme that came up in the analysis of the narratives was how His Holiness, the Dalai Lama played a major role in maintaining their emotional and social well-being in the face of their struggles. Many participants commented that the Dalai Lama is their anchor and moral compass in their daily life. This is very evident in the following excerpt:

Whenever I start doubting myself and am about to stray away from my path his image immediately brings me to reality and saves me. I have a picture of him in my room. Just seeing his image pushes me to work harder and helps me sustain my morality.

The Dalai Lama and the values that he propagates have inspired the Tibetan refugees in exile. This can be seen from the comments of one of the participants:

His Holiness's speech inspires me on how to value human life, how to be a good human being, how precious life is, how to better oneself, and the importance of modern education.

Another recurring theme that emerged in the analysis of the narratives was how Buddhist practices and beliefs played a major role in maintaining their resilience. The senior monk who validated the interview schedule revealed that the youth may not know in depth about Buddhist philosophy, but they are so heavily influenced from childhood about compassion, it becomes almost second nature in their habits. Many participants mentioned how Buddhism teaches them to think more about others rather than focusing on oneself. A participant narrates such an experience:

Love and compassion in Buddhism, His Holiness's speech inspires me. Thinking that others are suffering more than me helps in taking away the focus from the self to others.

There was a recurring theme of deflecting personal pain by focusing on the sufferings of others. This is very visible in the following excerpts:

I was very lucky compared to many other refugees. I got away without much sickness during the escape to India. Many got frostbite and died along the way. Thinking that others are suffering more than me, takes away the focus from the self to others…

Another mentions a similar common experience:

Knowing that my friends are in a similar situation has given me emotional support and I can adjust. From the mutual understanding that we are alone, on our own we are made to become self-reliant. Even though we would like to meet our parents, we cannot. There is no need to focus on the issue of not being able to go back. Rather, we start thinking that we must do something for the nation (Tibet).

Buddhism teaches followers to always keep the needs of other people in high regard and to be compassionate towards others. The value of humility and compassion is highlighted below by a participant:

When you read eight verses for transforming minds, these can help you a lot. The first verse itself says you should think like you can benefit others a lot. You should always consider others, regard others as in a higher position than yourself. You should always be at a lower position (humility).

Also, the Buddhist philosophy of karma was a recurring theme in the responses. The law of karma allowed them to accept their situations and also act in a way to allow for better karma in their next life or in this life itself.

The Dalai Lama also strongly recommends that the Tibetan youth focus on education, and this was reflected in the responses of the participants. Focusing on education gave them a purpose for the larger good. Education is not just seen as a personal achievement, but rather as a tool which will enable them to help the community and a homeland that is still aspiring to be free. The narratives of the interviews highlighted the importance of how an educated person will have a more authoritative voice in the struggle for Tibetan freedom.

Strongly cohesive community and peer support was reported as a significant factor in enabling the participants to cope in India. The participants mentioned that when they first came to India, they were consoled and supported by the other young children who had come before them:

Initially, I cried a lot. I would not talk to anyone. But the senior students kept telling us everything will be alright. And when new students came, we offered the same love and care and consoled them. It became like a chain.

The Tibetan community is highly collectivistic and cohesive in nature. There is a strong close-knit network of the Tibetan community in exile in India. The Tibetan youth in India have student unions that arrange for regular cultural and community events. The unions are also a source of regular get-togethers to discuss issues and new political developments.

The participants were separated from their parents almost 16 years ago. At that time international calls made from India were not very cheap. However, with the advent of social media, communication has become much easier and the Tibetan refugees are making optimum use of it to communicate with their parents. One participant mentioned how technology helps her when she gets severe homesickness:

I use google maps to look at my house back in Tibet. Although it is not clearly visible, it gives me a sense of being closer to home.

In summary, a range of coping resources were utilised by the Tibetan refugee youth, ranging from strong faith in the Dalai Lama, Buddhist practices and beliefs related to karma and compassion, community bonding and support, and the use of technology to connect with parents back home. The next theme focuses on the participants' meaning-making and perceived psychological growth from their adversities.

Meaning-making and perceived growth

The co-occurrence of distress and psychological growth was commonly reported by the participants and is consistent with studies on post-traumatic growth (Joseph & Linley, 2008; Hussain & Bhushan, 2013). Many of the participants reflected that because of the distance between them and their families back in Tibet, they deeply valued relationships and did not take them for granted. As one participant reflected:

Because of the distance, we value our parents more. We know what love is. I have seen others who take their family for granted.

Another recurring theme was that the Tibetan youth reported an enhanced sense of self-reliance and independence as they had to survive in a foreign land without the support and nurturance that a family typically provides. The participants also reported including the male participants who have become adept in domestic chores such as cooking and cleaning from a young age, which they might not have been if they stayed in Tibet. As one participant explains:

There was no one to cheer you up when you achieved something and also there was no one to bring you down when you made a mistake. This made me self-reliant. There is no one to save you, unlike those that have parents living with them. Decisions are all made by self. No dependence on anyone.

Most participants also reported that they have an increased appreciation of their religion and culture as there is freedom to explore and practise their religion in India. Many participants also responded that if they were at their current age in Tibet, they would be living the simple life of getting married, procreating and herding animals. Attaining college and university-level higher education in India has opened up new possibilities and better growth opportunities for themselves and for contributing to their country. The participants mentioned that they derived meaning from their struggles as they felt part of a larger cause:

When we (Tibetan refugees) do something, it is for myself, my family, my society, country, and my generation. More responsibility, and our life is on a bigger scale…

Among the participants there was a unanimous desire to contribute to a larger purpose as their upbringing in exile had given them an increased awareness of their privileged education as compared with those left behind in their homeland.

To summarise, the Tibetan refugee youth derived a sense of growth from their adversities related to understanding the value of family and relationships, finding personal growth in the form of self-reliance, appreciation of their culture and religion, and finding meaning in life by feeling part of a larger purpose.

Discussion

The present study aimed to explore the lived experiences of Tibetan refugees who as young children had escaped to India unaccompanied by their parents. These children at around the mean age of seven had to face a different environment, a new culture and language, and starkly different food and climate. Compounding the struggles of refugee life was the added strain of enduring it alone without their parents. Studies about unaccompanied refugee minors from across the globe report that they are a highly vulnerable group who are at higher risk to experience multiple traumatic experiences and develop PTSD, anxiety and depression (Eide & Hjern, 2013; Jensen et al., 2014). The participants reported feeling isolated, deprived and lonely. Walsh (2007) reported that refugees feel a sense of homelessness owing to experiencing a profound loss of their social network and cultural roots.

With time, the culture of the host country tends to get absorbed, almost inevitably. Here, many Tibetans are at a crossroads. As many of the participants reported, they escaped to India to learn more about their own culture and religion. However, ironically, they report that they fear losing their cultural identity with the increased freedom in India and media influence. Hussain and Bhushan (2011) report that second and third generation Tibetan refugees, especially those who were born in India and have no recollection of Tibet, have assimilated elements of the host culture into their lives to a great extent, even though they may not have completely forgotten their own culture. The participants were worried that some of the younger Tibetans are losing fluency in the Tibetan language and adherence to their indigenous customs. There was resentment and displeasure when one of them tries to get citizenship in their host country. The rationale being that if Tibetan refugees become citizens of the host country, the morale for the Tibetan cause will go down and there will be few Tibetans left if Tibet gains independence.

Studies in the literature support that after settling down in the host country, refugee children may experience an identity crisis because of the dual cultural membership. Refugee children and adolescents may feel torn between the culture of their homeland, the culture of the host country, as well as the refugee culture (Phinney, 1990). They may also get stigmatised as a result of their ethnicity in the new place (Yankey & Biswas, 2012). The participants in the study did report that at times they faced racial teasing in India and were taunted about their facial features.

Despite all the challenging aspects of their refugee life, the participants have coped and adapted quite well. Religion, spirituality, community bonding, and use of social media for communication have emerged as significant themes in their coping strategies. Voulgaridou et al. (2006) suggest that the motivation which originates from a person's active religious beliefs can positively influence the individual's coping in adverse situations. Religious and spiritual belief systems can help individuals interpret life events, thereby giving them meaning and clarity, and may help in the psychological integration of the traumatic experience (Koenig, 2006). Fazel and Young (1988) found that Tibetan refugees displayed greater life satisfaction despite limited economic resources and this was interpreted as finding self-contentment and the pleasure of living in the presence of their highest lama, the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama's speeches and teachings guide the Tibetan refugees in their life choices. The Dalai Lama is believed by the Tibetans to be a manifestation of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. Bodhisattvas are believed to be enlightened beings who have chosen to take rebirth to serve humanity. All the participants reported the Dalai Lama as the prime protective and cohesive factor for the Tibetan refugees throughout the world. Many of the participants reported having his picture and finding solace in it.

Many studies (Watkins & Cheung, 1995; Ruwanpura et al., 2006; Hussain & Bhushan, 2011) have reported the utilisation by Tibetan refugees of Buddhist religious and spiritual tenets as coping mechanisms. Buddhist values have also been reported to be helpful for healing for Cambodian refugees (Bryant-Davis & Wong, 2013). Buddhist philosophy provides a worldview that life is full of suffering and provides systematic techniques and practices to overcome them. So, for a practitioner of Buddhism, suffering is a given and hence cognitively there may be reduced aversion, avoidance and suppression of distress. Many of the narratives of the participants also highlighted that the cultivation of compassion played a huge role in helping them cope. In the cultivation of compassion, participants mentioned that they lose the focus on themselves by thinking of how they are not alone in their suffering and how many more are suffering on a higher level. This shift in perspective may reduce the ruminative self-processing of one's circumstances and mediate the distress experienced.

Community bonding and support is also an important theme that emerged in the analysis. All participants reported that their peers and the refugee community are sources of support and hope. Studies have reported that social support is a buffer against stressful life events (Charuvastra & Cloitre, 2008). Hussain and Bhushan (2011) also reported community support and shared collectivistic activities such as celebrating Tibetan festivals as a coping mechanism of Tibetan refugees in Dharamshala. For the Tibetan refugees who cannot physically meet their parents, communication on phone and social media is vital, and technology has facilitated it in recent years. The participants mentioned that earlier telephone calls to Tibet were very expensive, but with social media, they could now easily communicate with their parents and family back home.

In the whole process of coping with the struggle of being displaced from their home country and settling into a new host country, perceived self-growth was found in the narratives of the participants. Narrative accounts of the participants of this study extend support to the post-traumatic growth model (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004) which highlights the phenomenon of positive psychological changes experienced as a result of the struggle with highly challenging life circumstances. The narratives suggested that the Tibetan refugees derived a sense of growth from their adversities. At a young age, when one is still under the protective umbrella of one's parents, they left their family and came to a new place that had very little resemblance to their home country. This has moulded them into resilient and hardier individuals. All of them report being very independent, which would not have been the case had they still been living with their family in Tibet. They value relationships more and have an increased understanding of their religion and culture due to the freedom to practise their religion in India. They also perceived that their life had a larger purpose towards the Tibetan cause and derived meaning from it. Hussain and Bhushan (2013) also reported post-traumatic growth in Tibetan refugees in the areas of positive changes in outlook toward the world and people, the realisation of personal strengths, and the experience of more intimate and meaningful relationships. Tibetan cultural and religious factors may have provided necessary resources for coping and a spur for perceived psychological growth in the Tibetan refugees.

This study has significant implications. It highlights and brings into awareness the unique psychosocial issues of the Tibetan refugee youth in exile in India. Culturally sensitive psychosocial support and an understanding of traditional spiritual and religious coping mechanisms may be integrated into health services for the Tibetan refugees who lack family support and may not be familiar with the Western constructs of mental health. The positive meaning-making and self-growth expressed may be further explored and assimilated in a positive direction for further therapeutic work.

The present study has certain limitations. It has only taken into consideration college-educated Tibetan refugees who came to India as unaccompanied minors. Further studies could explore how the migratory experience is perceived by other Tibetan youth refugees who have similar backgrounds but with fewer educational opportunities. Further studies could explore in more detail the various risk and protective factors of the Tibetan refugees living in exile in India.

In summary

The Tibetan refugee youth separated from their parents have faced a range of struggles living in exile in India, ranging from acclimatising to the food and climate, to educational and financial struggles, challenges related to sustaining the Tibetan struggle and retaining their identity in a host country. A range of coping resources were utilised by them, ranging from strong faith in the Dalai Lama, Buddhist practices and beliefs related to karma and compassion, community support and the use of social media to connect with parents back home. The Tibetan refugees derived a sense of growth from their adversities, related to understanding the value of family and relationships, finding personal growth in the form of self-reliance, appreciation of their culture and religion, and finding meaning in life by feeling a part of a larger purpose.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Ven. Geshe Dorji Damdul, Director Tibet House, New Delhi for his inputs, insights and encouragement for this study.

ORCID: Parisha Jijina - https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7049-9383

References

Bean, T. M., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E., & Spinhoven, P. (2007). Course and predictors of mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors in the Netherlands: One-year follow-up. Social Science & Medicine, 64(6), 1204-1215. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.010 [ Links ]

Bernstorff, D., & von Welck, H. (2004). An interview with Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama. In Bernstorff, D. & von Welck, H. (Eds), Exile as challenge: The Tibetan diaspora. (pp. 107-123). New Delhi: Orient Longman. https://books.google.bi/books?id=eR6qa-BQ8p0C [ Links ]

Bryant-Davis, T., & Wong, E. C. (2013). Faith to move mountains: Religious coping, spirituality, and interpersonal trauma recovery. American Psychologist, 68(8), 675-684. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034380 [ Links ]

Charuvastra, A., & Cloitre, M. (2008). Social bonds and posttraumatic stress disorder. Annual Review of Psychology, 59(1), 301-328. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085650 [ Links ]

Derluyn, I., & Broekaert, E. (2005). On the way to a better future: Belgium as transit country for trafficking and smuggling of unaccompanied minors. International Migration, 43(4), 31-56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2005.00332.x [ Links ]

Derluyn, I., Mels, C., & Broekaert, E. (2009). Mental health problems in separated refugee adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44(3), 291-297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.016 [ Links ]

Dolma, S., Singh, S., Lohfeld, L., Orbinski, J. J., & Mills, E. J. (2006). Dangerous Journey: Documenting the experience of Tibetan Refugees. American Journal of Public Health, 96(11), 2061-2064. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.067777 [ Links ]

Eide, K., & Hjern, A. (2013). Unaccompanied refugee children - vulnerability and agency. Acta Paediatrica, 102(7), 666-668. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12258 [ Links ]

Fazel, M. K., & Young, D. M. (1988). Life quality of Tibetans and Hindus: A function of religion. Journal of the Scientific Study of Religion, 27(2), 229-242. https://doi.org/10.2307/1386717 [ Links ]

Finlay, L. (2009). Ambiguous encounters: A relational approach to phenomenological research. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 9(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/20797222.2009.11433983 [ Links ]

Hooberman, J., Rosenfeld, B., Rasmussen, A., & Keller, A. (2010). Resilience in Trauma-Exposed Refugees: The Moderating Effect of Coping Style on Resilience variable. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(4), 557-563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01060.x [ Links ]

Hussain, D., & Bhushan, B. (2009). The development and validation of Refugee Trauma Experience Inventory. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 1(2), 107-117. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016120 [ Links ]

Hussain D., & Bhushan, B. (2011). Cultural factors promoting coping among Tibetan refugees: a qualitative investigation. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 14(6), 575-587. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2010.497131 [ Links ]

Hussain, D., & Bhushan, B. (2013). Posttraumatic growth experiences among Tibetan refugees: A qualitative investigation. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 10(2), 204-216. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2011.616623 [ Links ]

Jensen, T. K., Skårdalsmo, E. M. B., & Fjermestad, K. W. (2014). Development of mental health problems-a follow-up study of unaccompanied refugee minors. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 8(1), 29-39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-8-29 [ Links ]

Joseph, S., & Linley, P. A. (Eds). (2008). Trauma, recovery, and growth: Positive psychological perspectives on posttraumatic stress. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118269718 [ Links ]

Koenig, H. G. (2006). In the wake of disaster: Religious responses to terrorism and catastrophe. Philadelphia: Templeton Foundation Press. [ Links ]

Lewis, S. E. (2013). Trauma and the making of flexible minds. Ethos, 41(3), 313-336. https://doi.org/10.1111/etho.12024 [ Links ]

Mahmoudi, K. M. (1992). Refugee cross-cultural adjustment: Tibetans in India. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 16(1), 17-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(92)90003-D [ Links ]

Norbu, D. (2001). China's Tibet policy. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203826959 [ Links ]

Phinney, J. S. (1990). Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: review of research. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 499-514. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499 [ Links ]

Ruwanpura, E., Mercer, S., Ager, A., & Duveen, G. (2006). Cultural and Spiritual Constructions of Mental Distress and Associated Coping Mechanisms of Tibetans in Exile: Implications for western interventions. Journal of Refugee Studies, 19(2), 187-202. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fej018 [ Links ]

Sachs, E., Rosenfeld, B., Lhewa, D., Rasmussen, A., & Keller, A. (2008). Entering exile: Trauma, mental health, and coping among Tibetan refugees arriving in Dharamshala, India. Journal of Trauma Stress, 21(2), 199-208. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20324 [ Links ]

Servan-Schreiber, D., Lin, B. L., & Birmaher, B. (1998). Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder in Tibetan refugee children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 37(8), 874-879. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199808000-00018 [ Links ]

Sierau, S., Schneider, E., Nesterko, Y., & Glaesmer, H. (2018). Alone, but protected? Effects of social support on mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(6), 769-780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1246-5 [ Links ]

Smith, J. A., Jarman, M. and Osborn, M. (1999). Doing interpretative phenomenological analysis. In Murray, M. and Chamberlain, K. (Eds), Qualitative Health Psychology: Theories and Methods. (pp. 218-240). London: Sage. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446217870.n14 [ Links ]

Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2003). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In Smith, J. A. (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods. (pp. 51-80). London: Sage. [ Links ] [Adobe Digital Editions version] http://med-fom-familymed-research.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2012/03/IPA_Smith_Osborne21632.pdf

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455-471. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490090305 [ Links ]

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01 [ Links ]

Terheggen, M. A., Stroebe, M. S., & Kleber, R. J. (2001). Western conceptualizations and eastern experience: A cross-cultural study of traumatic stress reactions among Tibetan refugees in India. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14(2), 391-403. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1011177204593 [ Links ]

United Nations. (2005). Conventions on the Rights of the Child. http://undocs.org/en/CRC/GC/2005/6 [ Links ]

Vervliet, M., Meyer Demott, M. A., Jakobsen, M., Broekaert, E., Heir, T., & Derluyn, I. (2014). The mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors on arrival in the host country. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 55(1), 33-37. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12094 [ Links ]

Voulgaridou, M., Papadopoulos, R., & Tomaras, V. (2006). Working with refugee families in Greece: Systemic considerations. Journal of Family Therapy, 28(2), 200-220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2006.00346.x. [ Links ]

Walsh, F. (2007). Traumatic loss and major disasters: Strengthening family and community resilience. Family Process, 46(2), 207-227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00205.x [ Links ]

Watkins, D., & Cheung, S. (1995). Culture, gender, and response bias: An analysis of responses to the self-description questionnaire. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 26(5), 490-504. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022022195265003 [ Links ]

Yankey, T., & Biswas, U. N. (2012). Life skills training as an effective intervention strategy to reduce stress among Tibetan refugee adolescents. Journal of Refugee Studies, 25(4), 514-536. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fer056 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Parisha Jijina

parisha.jijina@gmail.com