Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology

On-line version ISSN 1445-7377

Print version ISSN 2079-7222

Indo-Pac. j. phenomenol. (Online) vol.19 n.1 Grahamstown Aug. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20797222.2019.1641920

Nietzsche: Bipolar Disorder and Creativity

Eva Cybulska

Retired Consultant Psychiatrist, National Health Service, United Kingdom, E-mail address: corsack@btinternet.com

ABSTRACT

This essay, the last in a series, focuses on the relationship between Nietzsche's mental illness and his philosophical art. It is predicated upon my original diagnosis of his mental condition as bipolar affective disorder, which began in early adulthood and continued throughout his creative life. The kaleidoscopic mood shifts allowed him to see things from different perspectives and may have imbued his writings with passion rarely encountered in philosophical texts. At times hovering on the verge of psychosis, Nietzsche was able to gain access to unconscious images and the music of language, usually inhibited by the conscious mind. He reached many of his linguistic, psychological and philosophical insights by willing suspension of the rational. None of these, however, could have been communicated had he not tamed the subterranean psychic forces with his impressive discipline and hard work.

One must still have chaos within to give birth to a dancing star.

(Nietzsche, 1883-85/1999, p. 19)

General Considerations

All our consciousness is a more or less fantastic commentary on an unknown, perhaps unknow-able, but felt text. (Nietzsche, 1881/1982, p. 76)

Creativity can be defined as aptitude to bring into being something original, valuable and of lasting significance. It is a complex multidimensional construct with both cognitive and affective components, many of which appear to reflect a shared genetic vulnerability with bipolar disorder (Greenwood, 2016). The creative act is not creation ex nihilo, but it is more like unveiling, rearranging and synthesising already known facts, ideas and skills. The etymology of the verb cogitare (to think) goes back to the reduced form co- of the Latin prefix com (together) and agitare (to shake). Shifting moods can become that "shaking agent". The familiar can be seen in a new light, and this forms the essence of a creative act. How many people had seen an apple falling to the ground before this common occurrence inspired Newton to formulate a theory of gravity? Paradoxically, sometimes the more original a discovery, the more obvious it may seem afterwards.

A genius - that creative spirit - is a rebel and a provocateur who deconstructs the established truths, setting himself at odds with his contemporaries. As Nietzsche would have put it, s/he is often "untimely" and "born posthumously", with an influence that increases with the passage of time. Arguably, few philosophers have left a deeper imprint on Western culture than has Nietzsche - not just in the realm of philosophy, but also in psychology, literature, music and the arts in general. Thinkers as diverse as Heidegger, Freud, Jung, Camus and Wittgenstein; poets and writers including Rilke, Strindberg, Yeats, Hesse, Mann and O'Neill; composers such as Scriabin, Mahler and Richard Strauss; and painters - Munch, de Chirico, Dali - and many others fell under his spell. Wildly diverse groups such as anarchists, Nazis, and Zionists have claimed Nietzsche as their patron-philosopher.

One might argue that few of Nietzsche's ideas were completely new and that it is his art of expression - rich in paradox, ambiguity, vividness of imagery and beguiling beauty - that in fact makes such an indelible impression on the reader. Unlike most philosophers, Nietzsche speaks through emotion, in the manner of poets and musicians. At the heart of what he tries to communicate is deep pain and suffering, and anyone who is familiar with these feelings is likely to become "hooked" on him. He often spoke of his writings as "fish-hooks" and, in a manner of Jesus, he thought of himself as a "fisher of men"

The link between madness and creative genius has long been recognised. Plato emphasised the role of "divine madness" (theia mania) as a source of inspiration (see his Phaedrus, 370 BC/1997, p. 370), and Karl Popper, a philosopher of science, conceded that every discovery contains an "irrational element" (Popper, 1959/2005, p. 8). Henri Poincaré, a prominent nineteenth century French mathematician, stressed that "it is by logic that one proves, but it is by intuition that one invents" (cited by Gray, 2013, p. 12). Manic depression (now renamed "bipolar affective disorder") has been shown to be particularly linked to literary creativity (Andreasen, 1987; Jamison, 1993; Ludwig, 1995). Nancy Andreasen (1987), in her pioneering study of 30 writers, matched with a control group, found that 80% of writers met the diagnostic criteria for mood disorder, and as many as 50% met the criteria for bipolar disorder. By comparison, the lifetime prevalence of a severe form of bipolar disorder in the general population is 1% (6% when considered as a spectrum). Up to 50% of those experienced psychotic symptoms at some time, mostly during manic episodes. Of course, bipolar disorder is not a guarantee for creativity, since only 8% of those affected could be considered highly creative (Greenwood, 2016). Other factors, such as acquisition of knowledge and skill, ambition, determination, discipline and hard work - all of which Nietzsche demonstrated in abundance - are of great importance. As Jamison (1993) observed, many geniuses, including Byron, Tennyson, Melville, William and Henry James, Schumann, Coleridge, Wolf, Hemingway and Plath suffered from bipolar disorder.

The Impact of Moods

Oscillating feeling states can be beneficial in diverse ways, and upswings of mood appear to spur bursts of creativity. Elated mood can ignite thought, create a temporary chaos and open the gate to the irrational by removing customary inhibitions and censorship, thus widening the associative field (see Carson, 2014). In this Dionysian tumult, novel associations by sound or image can be forged. The former may lead to assonances, alliterations, onomatopoeias, rhyme and rhythm, whist the latter can initiate similes, metaphors, allusions, metonymies and connotations. Paradox, oxymoron, irony and hyperbole may also be released by elated mood (Kane, 2004). High energy, which often accompanies elevated mood, can enhance the speed of cognition and expediency of work. By his own account, Nietzsche completed the first three books (chapters) of his Zarathustra in three separate 10-day bursts of creativity. Also, such moods often have an admixture of dysphoria and irritability, and this may lead to bald, even vicious, attacks on ideas or persons. Depressive moods, on the other hand - with slow cognition- are conducive to rumination. Mixed affective states, marked by rapidly fluctuating mood and energy levels, can spark some startling juxtapositions in thought. Alternating moods change the perspective and induce divergent thinking, which lies at the heart of creativity.

Psychoticism, Disinhibition and Creativity

Andreasen aptly commented that during "the creative process the brain begins by disorganising" (Andreasen, 2005, pp. 77-78). For Nietzsche, creation and destruction were two sides of the same coin: "we can destroy only as creators" (Nietzsche, 1882/1974, p. 122). The Kantian categorical framework breaks down in psychosis, if only temporarily, and a regression to the pre-categorical mode of thinking is necessary to forge novel associations. Linking remote elements into new combinations is at the heart of the creative process (Mednick, 1962), with a "cognitive flux" as its essential precondition.

Hans Eysenck (1995) drew attention to a link between psychoticism and genius. But how can the psychotic apperception of the world be conducive to creativity? Several researchers have purported that, in psychosis, there is a failure in the filtering mechanism between the conscious and the unconscious (Carson, 2014; Carter, 2015; Frith, 1979). I propose that the term "enlarged consciousness" designate such a condition, and posit a regression to earlier stages of cognition (Freud's "primary process thinking") as its mechanism. In this state of enlarged consciousness, antithetical thoughts and images are set to be allowed in, and this can lead to oxymoronic expressions and contradictions (see below the examples of these in Nietzsche's writings). Eric Kandel, a Nobel Prize neuroscientist, stressed that psychosis does not generate creativity, but rather liberates powers of imagination, which would usually remain locked in by the inhibitions of social and educational convention (Kandel, 2018, pp. 146-147). It goes without saying that a creative individual must already have a wide associative pool at his or her disposal, and that no "dancing star" can be born from chaos alone.

Malinowski (1923/2013), who pioneered an ethno-graphic field study of undeveloped languages, noted the similarity in the way children and "savages" use words. Primarily, words arise from the physiology of emotional states; they do not tell us about the state, but are the state. "The word is regarded as a real entity, containing its meaning as a Soul-box contains the spiritual part of a person …", he wrote (ibid., p. 308). A word has power of its own and can bring things about rather than merely describe reality or express thoughts.1 By regressing to that stage of language, poets re-capture the word's original magical power. Unsurprisingly, MacLeish (1985) stressed in his "Ars Poetica" that "a poem should not mean /But be" (ll. 23 - 24). Nietzsche often emphasised that he wrote "physiologically"; to adapt Yeats's imagery, he was the dancer that also was the dance.

Arthur Koestler suggested that the ability to suspend and then reinstate rational thought is an essential feature of creative genius. He considered association by sound affinity - punning - one of the notorious "games of the underground", which manifest themselves in dreams, in the punning mania of children, and in mental disorders. The capacity to regress to these "games", without losing contact with the surface, is a vital part of poetic and other forms of creativity (Koestler, 1964, p. 314). Kris, an art critic and a psychoanalyst, held that creative individuals have the capacity to switch between the rational (Freud's "secondary process-thinking") and the irrational (Freud's "primary process thinking") almost at will. He dubbed it a "regression in the service of the ego" (Kris (1936/1952, p. 177). By contrast, cognitive inhibition acts as a filtering and pruning mechanism of material not relevant to the task at hand (MacLeod, 2007), which forms a vital part of the executive function of the mind.

Revelation

It is often by way of revelation that a creative genius arrives at novel association. Sass, inspired by German psychiatry, called it a "truth taking stare" in which reality is unveiled as never before and the world looks eerie, weirdly beautiful and tantalisingly significant (Sass, 1992, p. 44). The concept of unveiling the truth as aletheia was central to Heidegger's phenomenology of meta-physics (Heidegger, 1926/1962, p. 57). Heidegger adopted this term from ancient Greek mythology, and it has been variously translated as "disclosure", "unconcealedness" or "unforgetting" (given its etymological association with the river Lethe in Hades, drinking from which leads to complete forgetfulness). When a familiar, yet repressed, experience erupts through the threshold of consciousness in a historically unfamiliar situation, it feels both familiar and new; as such, it feels uncanny (see Freud's "The Uncanny", 1919/1985). Aletheia is closely related to apophenia, a tendency to perceive connections and meaning between unrelated things.

A revelation of a scientist and a revelation of a psychotic can look disturbingly similar. John Nash, a genius mathematician and a Nobel Prize winner who suffered a major psychotic breakdown, was asked how he could possibly believe that he was being recruited by aliens. He replied: "Because the ideas I had about supranatural beings came to me the same way that my mathematical ideas did. So, I took them seriously" (Nasar, 1998, p. 11). Perhaps, revelation could be viewed as a regression to an earlier stage of cognitive oneness, when knowing and feeling are not yet differentiated. It must be stressed that nobody in the grip of either raving mania or deep depression can be creative, as these conditions render the mind incapable of coherently formulating creative work. Rothenberg (1990) thus vehemently opposed any positive influence of mood disorder on creativity. But this need not be "all or nothing", and an inverted U-shaped relationship between hypomania and creativity, where only moderate levels enhance it, has been proposed (Carter, 2015). As Paracelsus famously said: "the dose makes the poison".

The Nietzsche Case

Perhaps everything great has been merely mad to begin with … . (Nietzsche, 1886/1990, p. 172)

Rejecting a century-old diagnosis of syphilis, I diagnosed Nietzsche's mental illness as "bipolar affective disorder, consisting of brief manic episodes with some psychotic features alternating with longer depressive phases studded with somatic symptoms" (Cybulska, 2000); this diagnosis was later endorsed, almost verbatim, by Professor Julian Young (2010, p. 560). Nietzsche's trajectory towards madness may have begun much earlier than is often believed. In his early essay "On Moods", he wrote: "Right through the middle of my heart. Storm and rain! Thunder and lightning! Right through the middle!" (Nietzsche, 1864/2012). At the age of 26, shortly after completing his first book, The Birth of Tragedy, he confessed to a friend: "In addition to many depressed and half-moods, I have also had a few elated ones and have given some sign of this in the small work I mentioned", and "the words 'pride' and 'craziness' are too weak to describe my intellectual 'insomnia'" (Nietzsche to Erwin Rohde, March 29, 1871; in Middleton, 1996, p. 79). This book became a kind of personal and professional manifesto, which contained the seeds of many of Nietzsche's later ideas. Its provocative style heralded excesses of his mature writing, which in crescendo fashion reached the apogee in his last books of 1888. A year before his total mental breakdown, Nietzsche wrote: "I'm working energetically, but full of melancholy, and not yet liberated from the violent mood shifts that the last few years have induced in me" (Nietzsche to Köselitz, December 20, 1887; cited by Krell, 1997, p. 143).

Nietzsche's discourse is rooted in associative thinking, and his associations, being in the realm of sound and imagery, are within the modus operandi of the non-dominant hemisphere. Not surprisingly, thus, his oeuvre abounds in logical contradictions - to the extent, as commented by Jaspers, that "Self-contradiction is the fundamental ingredient in Nietzsche's thought. For nearly every single one of his judgements, one can also find the opposite" (Jaspers, 1936/1997, p. 10). The form and the content of Nietzsche's writings are inextricably intertwined. His mythopoetic art of philosophising draws the reader to join his Dionysian dance of creation and destruction. And, in the Dionysian worldview, the boundaries are unstable and continually shifting in a kaleidoscopic manner.

A philosopher who has traversed many kinds of health, and keeps traversing them, has passed through an equal number of philosophies; he simply cannot keep from transposing his states every time into the most spiritual form and distance: this art of transfiguration is philosophy. We philosophers … have to give birth to our thoughts out of our pain and, like mothers, endow them with all we have of blood, heart, fire, pleasure, passion, agony, conscience, fate, and catastrophe. (Nietzsche, 1882/1974, pp. 35-36)

As Higgins (1987, p. XI) aptly observed, philosophical scholarship underplays emotional response to the texts it interprets. By and large, the scholars reject the pivotal role of emotions and treat Nietzsche's entire oeuvre as if it were conjured up by some disembodied, unfeeling spirit. And yet, he criticised philosophers for turning insights into "concept mummies", so that nothing real would escape their grasp alive (Nietzsche, 1888/1976b, p. 479). Any attempt to interpret Nietzsche's writings in the context of his personality, his life and his mental illness risks being branded "reductionistic", notwith-standing the fact that excluding such interpretations is precisely what is reductionistic. And yet, Nietzsche repeatedly stressed that at all times he thought with his whole body and his whole life and did not know what purely intellectual problems were. In Nietzsche studies, there are some notable exceptions to the "concept mummies" scholarship, such as Pasley (1978), Higgins (1987), Krell (1997), Marsden (2002), and, above all, Pierre Klossowski (1969/1997).

Imagery, Dreams and the Unconscious

The mightiest capacity of metaphor which has hitherto existed is poor and child's play compared with this return of language to the nature of imagery. (Nietzsche, 1888/1986, pp. 106-107)

The unconscious often speaks in images, the stuff that dreams are made of. Nietzsche's poetic writings count among the most imagistic in German literature, and this is particularly striking in his Zarathustra. As his private letters abound in imagery too, it is indicative of his way of thinking rather than of a rhetorical embellishment (Higgins, 1987, p. 13). According to Kristeva (1984. p. 124), poetry is a return to the repressed semiotic in language through the use of rhythms and tones. It is as if the semantic values of the discourse regressed to phonemic and eidetic qualities; it is as if words had a life of their own. In these instances, words form an autonomous message with its own sound and visual quality; the signifiers become the signified. Thus Spoke Zarathustra, written at a time of personal crisis, is rich in vivid imagery, and Luke (1978) observed that the same image can express several ideas, while the same idea may suggest a number of images. Such malleability is typical of "primary process thinking". Nietzsche regarded Zarathustra as his greatest gift to humanity, but he was also aware that it was "an unintelligible book", because it was based on experiences that he shared with nobody (Nietzsche to F. Overbeck, August 5, 1886; in Middleton, 1996, p. 254). One is reminded of Kant's observation (1798/1978, p. 117) that "the only general characteristic of insanity is the loss of a sense for ideas that are common to all (sensus communis), and its replacement with a sense for ideas peculiar to ourselves (sensus privatus)". Zarathustra opens with a chilling image of a "rope-dancer" in the market square who, pursued by the buffoon, plunges to his death:

Just as he had reached the middle of his course the little door opened again and a brightly dressed fellow like a buffoon sprang out and followed the former with rapid steps. "Forward, lame foot!" cried his fearsome voice, "forward sluggard, intruder, pallid face! Lest I tickle you with my heels! What are you doing here between towers? You belong in the tower, you should be locked up, you are blocking the way of a better man than you!" And with each word he came nearer and nearer to him: but when he was only a single pace behind him, there occurred the dreadful thing that silenced every mouth and fixed every eye: - he uttered a cry like a devil and sprung over the man standing in his path. But the latter, when he saw his rival thus triumph, lost his head and the rope; he threw away his pole and fell, faster even than it, like a vortex of legs and arms. The market square and the people were like a sea in a storm: they flew apart in disorder, especially where the body would come crashing down. (Nietzsche, 1883-85/1969, pp. 47-48)

This awesome, gripping passage sends shivers down the reader's spine. It ends with a prophetic exclamation from Zarathustra: "your soul will be dead before your body: therefore, fear nothing anymore!" (ibid.). The fragment reads like an oracular, ambiguous warning. But warning of what, and to whom? To the reader? To humanity? Or was the author confessing deep dread and a premonition of his own fate? Was not Nietzsche's own soul dead before his body? Herein lies the essence of Nietzsche's art: the compelling vividness of the eerie imagery is expressed with the spectral lucidity of language, all shrouded in the tantalising ambiguity of the meaning. It invites almost infinite interpretations.

Nietzsche was strongly attracted to imagery of height, of rise and fall, of ascent and descent. Perceptively, Luke (1978, p. 105) relates this to the hypomanic states that played an important role in his thought and imagery. One might say that Nietzsche had an "Icarus complex" which propelled him to rise to celestial heights of creativity and dance perilously on a narrow rope above the abyss of madness, only ultimately to fall to his death, "crashing down". The sound-image of the horrifying, deranged cry of the rope-dancer reappears in the chapter "The Convalescent":

One morning, not long after his return to the cave, Zarathustra sprang up from his bed like a madman, cried with a terrible voice, and behaved as if someone else were lying on the bed and would not rise from it; and Zarathustra's voice rang out in such a way that his animals came to him in terror … . (Nietzsche, 1883-85/1969, p. 232)

The themes of death, shrieks, horror and madness run through these passages. In his boyhood, Nietzsche had visited Jena on a school trip and had been perturbed by a scream coming from the tower of a mental asylum. He recorded: "Then a shrill scream pierced our ears. It came from a lunatic asylum nearby. Our hands locked more tightly. It was as though an evil had touched us with frightful, flitting wings" ("On my August Vacation", 1859, J 1. 143., cited by Krell, 1997, p. 62). Had he once heard such a shriek coming out of his father's mouth in an epileptic fit, shortly before his death? If so, he may have linked this with madness. Ironically, it was in the Jena asylum, with its towers, where Nietzsche was detained in the year 1889. Munch's famous "The Scream" (painted in 1893) is perhaps the most arresting visual representation of the inner terror and loneliness of insanity. Like Nietzsche, Munch struggled with fear of madness for much of his life, and his sister was incarcerated in a mental asylum.

Equally imagistic are Nietzsche's cardinal ideas. His famous "God is dead" brings to mind a painting by Holbein, "The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb", in the Basel Kunstmuseum, which Nietzsche may have seen. It is more of an image than an idea (as is discussed in more detail in Cybulska, 2016). Nietzsche's notion of the Übermensch, which he never explained, is yet another image-thought:

Behold, I teach you the Superman: he is this lightening, he is this madness! […]

Behold, I am a prophet of the lightening and a heavy drop from the cloud: but this lightening is called Superman. (Nietzsche, 1883-85/1969, pp. 43-43)

Deeply buried trauma can be reached only through primary process thinking. Could it be that "God is dead", a line delivered by a madman, the Übermensch, as well as the Eternal Return were phantasms (to use Klossowski's term) that emerged from the twilight of psychosis? They vanish as suddenly as they appear and both seem discontinuous with Nietzsche's previous and subsequent writings (see Cybulska, 2008).

The Power of Music

Nietzsche shared with his one-time idol, Schopenhauer, a belief that music was a direct objectification of the Will (corresponding with Freud's id): "for this reason the effect of music is so very much more powerful and penetrating than is that of the other arts, for these others speak only of the shadow, but music of the essence" (Schopenhauer, 1818/1969, p. 257). In Wagner, he found a fellow worshipper and practitioner of Schopenhauer's philosophy. Not only was The Birth of Tragedy inspired by these two idols, but one might say that Nietzsche's entire oeuvre bore their stamp. He used words where Wagner would have used musical notes, and became the only other philosopher after Schopenhauer who had such profound effect on literature and the arts.

Following a lead from Schiller, Nietzsche believed that, prior to the act of writing, a poet "does not have within him an ordered causality of ideas, but rather a musical mood" (Nietzsche 1872/1993, p. 29). He argued that every style was good which communicated the inner state, with the multiplicity of inner states necessitating many styles. "To communicate a state, an inner tension of pathos through signs, including the tempo of these signs, is the meaning of every style", he wrote in Ecce Homo (Nietzsche, 1888/1986, p. 74). Nietzsche's most poetic composition was Thus Spoke Zarathustra, and he confessed that the whole of it "might be reckoned as music" (ibid., p. 99). What is striking about this book is its rhythm. A poem known as "Zarathustra's Roundelay", forming part of "Night-Wanderer's Song", reads:

O Man! Attend!

What does deep midnight's voice contend?

'I slept my sleep -

'And now awake at dreaming's end:

'The world is deep,

Deeper than day can comprehend.

'Deep is its woe,

'Joy - deeper than heart's agony:

'Woe says: Fade! Go!

'But all joy wants eternity,

'Wants deep, deep eternity!'

(Nietzsche, 1883-85/1969, p. 333)

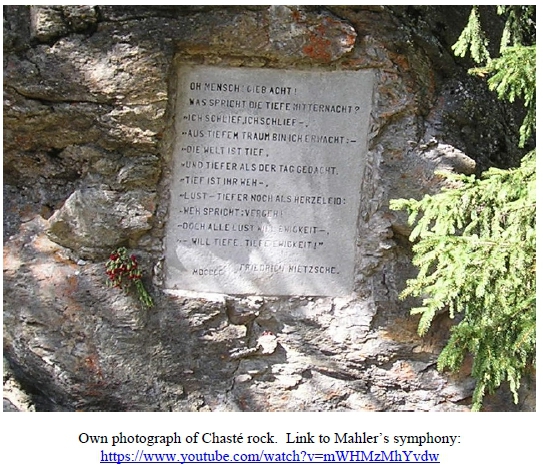

And sung it was. Gustav Mahler, who read Nietzsche avidly, took up the challenge and incorporated the poem in the fourth movement of his Third Symphony (follow the link below). Nietzsche's friends also commemorated his lone walks on Chasté Peninsula in the Swiss Alps and arranged for the text to be engraved in rock (see photograph below).

Wort-spiel (play on words) end puns form the hallmark of Nietzsche's style. One must have "ears for unheard-of-things" (Nietzsche, 1883-85/1969, p. 52) to hear the music in words. His works contain a number of clang-associations, including the imaginative (and, possibly, autobiographical) observation that, in a state of weeping (weinen), complaints (Klagen) are nothing but accusations (Anklagen):

'Is all weeping not a complaining? And all complaining not an accusing?' (Ist alles Weinen nicht ein Klagen? Und alles Klagen nicht ein Anklagen?) […] Thus you speak to yourself, and because of that, O my soul, you will rather smile than pour forth your sorrow … . (Nietzsche, 1883-85/1969, p. 240)

Through sound association Nietzsche arrived at this profound psychological insight, which was later seized by Freud in his essay "Mourning and Melancholia" of 1917, where he persuasively claimed that complaints of depressed patients were "plaints" in the old sense of the word (for more discussion see Cybulska, 2015b).

Clanging refers to a mode of speech characterized by association of words based upon sound rather than concepts. It is particularly frequent in manic psychotic states. Gustav Aschaffenburg found that manic persons generated "clang-associations" almost 10-50 times more than did those who were non-manic (see Kraepelin, 1913/1921, p. 32). The above passage by Nietzsche is a good example of combining associations by sound with etymological reading. His passion for alliterative amplifications gave birth to some very evocative, mood-setting phrases such as "the loneliest loneliness"(die einsamste Einsamkeit) or "the abysmal abyss" (die abgrundlische Abgrund).

Nietzsche's use of leitmotifs deserves attention, as these signal the emergence of emotionally charged ideas in his writings. For example, the word ungeheure (horrific, monstrous) heralds Nietzsche's most awesome ideas, such as that of "Eternal Return", "God is dead" and the Übermensch, and it appears for the first time in relation to his father's death (Cybulska, 2013, 2015a, 2016). As the leitmotifs also appear in his private letters and unpublished writings, they were more likely to have been a part of his "musical" way of thinking rather than a deliberate rhetorical device influenced by Wagner.

The irresistible appeal that Wagner's music had for Nietzsche may possibly have been due to its protracted dissonances, as these reflected a coexistence of jarring emotional states in his own soul. Particularly in mixed-affective states (Nietzsche's "half-moods"?) elation can coexist with pain and despair, and death can be felt to be very close. Wagner's Tristan and Isolde, with its powerful "Tristan chord", was Nietzsche's most beloved musical composition. Not surprisingly, he chose the ancient god Dionysus as his patron, a god of wine and frenzy, a god of grief and tears, of life and death. Perhaps, a god of dissonance par excellence? Dionysus made his first appearance in The Birth of Tragedy and the last in Nietzsche's "mad" letters of January 1889.

Etymology as Path to Genealogy of Morality

With his ear for unheard-of-things, Nietzsche was parti-cularly sensitive to the etymology of words, and that led him to many philosophical and psychological insights. I suggest that it was not Nietzsche's academic interest in etymologies, but his sensitivity to the sounds of words that led him to uncover their original meaning. The origin of the word "etymology" is telling in itself: it derives from ἔτυμον ("truth") and λόγος ("word"). One might say that etymology is a truth-telling of the meaning of words. In The Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche (1887/1994a) retraced the etymology of moral concepts such as guilt, conscience, law and justice to human custom and challenged the centuries old view that moral values had a divine origin. For instance, the etymology of the German word Sittlichkeit (morality) derived from Sitte (custom), and this led him to define morality as merely an "obedience to customs". Hence someone who breaks away from custom and tradition is considered immoral, even evil. Those who overthrow the existing law of custom are initially labelled as bad or criminals, and it is only when the custom changes that history treats them as "good". Nietzsche also traced the origin of schlecht (bad) to schlicht (plain, common). What we now consider good or noble stems from the prerogatives of the ruling class of the nobles, and what is considered bad once denoted the actions of common folk. A free spirit that rises above (über) the herd custom becomes the Übermensch, the creator of values. Follow-ing the etymological trajectory, Nietzsche asserted that "guilt" derived from "debt":

Have these genealogists of morality up to now ever remotely dreamt that, for example, the main moral concept "Schuld" (guilt) descends from the very material concept of "Schulden" ("debts")? Or that punishment, as retribution, evolved quite independently of any assumption about freedom or lack of the freedom of the will? (Nietzsche, 1887/1994a, p. 43)

In German, die Schuld means both guilt and debt, and hence, at the heart of morality, lies a concept of "being in debt" to the creditor, such as God (see Cybulska, 2016). Nietzsche (1887/1994a, pp. 54-55) also stressed that "punishment is revenge" (Strafe ist Rache). Rache (revenge) has the same root as Recht (law), and ultimately derives from rechen (to count). Perhaps, law is about reckoning, about counting even, and about taking revenge? Not surprisingly, this brilliant philologist turned the whole system of morality on its head! Ultimately, Nietzsche's "genealogy of morality" was none other than the genealogy of words.

Antithetical Thought and the Tension of Opposites

Freud (1900/1985, p. 430) pointed out that dream-thoughts (as encountered in dreams and in psychosis) behave like ancient languages, in which only one word was used to denote two contrary meanings. The intended meaning is discerned from the context. Antithetical words can be found in ancient Greek, and in Antigone by Sophocles (which Nietzsche, as a classical scholar, studied in the original) the Chorus proclaims in the ode on man: "Wonders (ta deina) are many and none more wondrous (deinoteron) than man" (Sophocles, 441 BC/ 1906, l. 334,). The translation becomes problematic when we realise that deinos means both "wonderful" and "terrible".

Nietzsche intuitively uncovered the antithetical meaning of besser (better) and böser (worse), arriving at one of his most paradoxical statements: Der Mensch muss besser und böser werden ("one must become better and worse") (Nietzsche, 1883-85/1999, p. 359). Also, the subtitle of his Zarathustra is suitably antithetical: "A Book for Everyone and No One". His other antinomic/ oxymoronic ideas include: "pleasure is a kind of pain" (Nietzsche, 1885/1968, p. 271), "great despisers are also the great venerators" (Nietzsche, 1883-85/1969, p. 44), truth is "a lie according to fixed convention" (Nietzsche, 1896/1976d, p. 47). The Apollonian and the Dionysian became the most famous of his antinomic constructs. The battle of opposites, fuelled by lifelong mood fluctu-ations, became a turbulent undercurrent in Nietzsche's philosophy and in his life. The constant tension and energy of the conflict were a source of inspiration and creativity for him; the strife led to "new and more powerful births" (Nietzsche, 1872/1993, p. 14).

The Revelation of Eternal Return: An Illumination, a Metaphor or a Delusion?

The eternal return of the same (die ewige Wiederkunft des Gleichen) has long puzzled scholars of Nietzsche. Several books have been written on this subject (e.g. by Stambauch, Klossowski, Löweth), but the title of Klossowski's treatise, Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle, seems to capture the mood of the doctrine. The pertinent question arises: was it a metaphor, a scientific idea, as Nietzsche claimed, or a delusion?

Jaspers observed that Nietzsche's unique way of philosophising hinged on its revelatory characteristics and that his poems were a form of communication between himself and his "own dark and mysterious depth" (Jaspers, 1936/1997, p. 410). In a moment of psychotic elation, during the summer of 1881, the idea of Eternal Return suddenly assailed Nietzsche's consciousness and became central to his thought. In the moment of elated mood (Stimmung), a gate to the unconscious was blown open and the earlier, pre-categorical form of cognition prevailed. Feeling and knowing fused in Nietzsche's mind, giving rise to that mystical sense of "primal Oneness" of which he spoke in The Birth of Tragedy (1872/1986, p. 17). The revelation of that moment transfigured a deep sorrow into a life-redeeming formula. The intersection of pain and elation became fixed in Nietzsche's mind, and he would crave the return of that moment - the more pain, the more overcoming, the more of the victorious elation (Cybulska, 1913).

The beguiling passage introducing the revelation of the vicious cycle of eternal return reads:

- What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: "This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything unutterably small or great in your life will have to return to you, all in the same succession and sequence - even this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and even this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned upside down again and again, and you with it, speck of dust!" (Nietzsche, 1882/1974, p. 273).

Nietzsche later recalled how the idea struck him like lightning in a moment of "ecstasy whose horrific (ungeheure) tension discharged itself in a flood of tears" (Nietzsche, 1888/1986, p. 103). The silhouette of that moment hovered around him for the rest of his life. Nietzsche used the liturgical word ewige (eternal), and the word Wiederkunft (return) which has religious connotations (Wiederkunft Christi means "second coming of Christ"). The Ewige Wiederkunft appears 36 times in Nietzsche's private notes and published writings between August 1881 and the end of 1888. Since 1884, he also used Ewige Wiederkehr (eternal recurrence), but only eight times (see www.nietzschesource.org). Interestingly, it is the word "recurrence" that Poincaré employed in his 1890 "recurrence theorem". This great mathematician proposed that certain isolated mechanical systems would, after a sufficiently long but finite time, return to the initial state. Albeit, there was no mention of a "spider" or "moonlight" returning in his theory! Tellingly, he used the mathematical term "infinite" and not the liturgical word "eternal", as Nietzsche did.

But what did Nietzsche himself consider the Eternal Return to be? He believed that it was the most scientific of all ideas and intended to study sciences to prove it - despite his total lack of mathematical aptitude. It was his friend Lou Salomé who persuaded him not to pursue the project. As a metaphor, Eternal Return has appeal, and Freud utilised it in his concept of "repetition compulsion" (Cybulska, 2015b). Most Nietzsche scholars treat it as a metaphor. But, had it been a metaphor, then Nietzsche certainly never gave any indication thereof, and his plan to prove it "scientifically" would speak against such an interpretation.

This leaves us with the possibility of a delusion, an attempt at explaining the un-explainable, to understand the un-understandable. Nietzsche professed that "My endeavour [was] to oppose decay and increasing weak-ness of personality. I sought a new 'centre' ... . To the paralysing sense of general disintegration and incom-pleteness I opposed the eternal return" (Nietzsche, 1883-88/1968, p. 224). Bertram perceptively commented that the Eternal Return was "a pseudo-revelation" and "a monomaniacal and a sublimely irrational and unfruitful private delusion" (Bertram, 1918/2009, p. 306). Perhaps, Nietzsche desperately wanted to endow his very private and disturbing experience with universal meaning and a sense of respectability?

Aggressive Dysphoria versus Sublime Elation

In mixed-affective states, exuberance is replaced by irritable-labile mood and social disinhibition. It can be an explosive mixture: "I am not a man, I am dynamite", Nietzsche announced in his autobiography, Ecce Homo (Nietzsche, 1888/1986, p. 126). Hypomanic irritability was probably responsible for the increasingly insulting and aggressive tenor of his voice in his last productive year of 1888:

Christianity is a metaphysics of the hangman. (Nietzsche, 1888/1976a, p. 500)

God degenerated into the contradiction of life, instead of being its eternal transfiguration and Yes! (Nietzsche, 1888/1976b, p. 585)

In Ecce Homo, Nietzsche's most disinhibited, grandiose and abusive book, hypomanic mood shows itself in the chapter titles - such as "Why I am so wise", "Why I am so clever", and "Why I am a destiny". Possibly driven by irritability, he hurled insults at Ibsen (with whom he had much in common) by calling him a "typical old maid", and also at Wagner (whom he loved) by labelling him a "Cagliostro of music".

The hyperbole of many passages in Nietzsche's oeuvre may have been fuelled by his hypomanic moods. His use of exclamation marks is prolific. In German (and perhaps in continental Europe) the use of exclamation marks is more frequent than in English, but, even by German standards, Nietzsche's use is very high. Also, Nietzsche was exuberant in his use of "over (über)-words": over-fullness, over-goodness, over-time, over-kind, over-wealth, over-drink, going-over. Sometimes he juxtaposed them with under (unter)-words, such as untergehen (to go under).

But he also spoke softly: "Thus, I spoke, and I spoke more and more softly: for I was afraid of my thoughts and thoughts behind the thoughts" (Nietzsche, 1883-85/ 1969, p. 179). The Night Song is probably the most beautiful and gripping of his pianissimo writing:

It is night: now do all leaping fountains speak louder. And my soul too is a leaping fountain.

It is night: only now do all songs of lovers awaken. And my soul too is the song of a lover.

Something unquenched, unquenchable, is in me that wants to speak out. A craving for love is in me, that itself speaks the language of love.

[…]

Withdrawing my hand when another hand already reaches out to it; hesitating, like the waterfall that hesitates even in its plunge - thus do I hunger after wickedness.

[…]

It is night: now do all leaping fountains speak louder. And my soul too is a leaping fountain ...

(Nietzsche, 1883-85/1969, pp.129-130)

Closing Remarks

Ultimately the growth of consciousness becomes a danger; and anyone who lives among the most conscious Europeans even knows that it is a disease. (Nietzsche, 1882/1974, p. 300)

It is impossible to assess to what degree mental illness influenced Nietzsche's creativity. One would have to conduct an experiment with two Nietzsches, one with and one without mental illness, but that would be an impossible absurdity. Most likely, he would have been a brilliant writer in either case, but his shifting moods and proximity to psychosis liberated the power of his imagination and facilitated an expression thereof. Of all Nietzsche's ideas, that of the Eternal Return is the most disturbing, since - in my view - it marks crossing the Rubicon between Reason and Unreason. Poincaré's "recurrence theorem" evolved in the mind of a mathe-matical genius; limited in its scope, it was subject to verification by scientific means. The rational mind must be prepared to relegate the idea to a waste basket of thought, as Poincaré himself stressed. There is, however, no evidence that Nietzsche ever had any doubt regarding this idea, or ever revised or attempted to "falsify" it (to appropriate Karl Popper's method). Perhaps he did not do so because it expressed an inner truth which for him was beyond doubt. Ultimately, it is Nietzsche's claim that his Eternal Return was the most scientific of all ideas that relegates it to the realm of Unreason. Like Klossowski, I believe that deep down Nietzsche knew it, and that is why he shuddered whenever he spoke of the doctrine to his friends. His lifelong fear of madness stared him in the face (for a detailed discussion, see Cybulska, 2013). It must be emphasised that Nietzsche's unique creativity can never be proven to have been "caused" by his bipolar disorder; it was merely released and amplified by it.

Nietzsche's writings, and particularly his Zarathustra, became a memoir of nekyia, a commentary on his own journey into the underworld of the soul. He identified himself with the subterranean, wandering hero, Odysseus: "I too have been in the Underworld, like Odysseus, and I shall yet return there often" (Nietzsche, 1879/1976a, p. 67). In his chapter in Nietzsche: Imagery and Thought (Pasley, 1978), Bridgwater penned this poignant line: "Nietzsche is the only explorer who sets his prow towards the ocean and steers his course by the light of the stars only" (Bridgwater, 1978, p. 241). Nietzsche was indeed a fearless seafarer into night! But to venture into the night of the Unconscious with no compass of reason is an act of bravado, with potentially catastrophic conse-quences. The world of psychosis knows none of the boundaries or limitations of the sober, rational mind, and the seductive voices of the sirens of madness proved too powerful to resist for this lonely poetic genius.

Nietzsche wrote whilst walking on a tight rope spanned above the abyss of the sea of the Unconscious, and this has earned him a very special place not only in the realm of ideas, but also in the realm of the human passions. This brilliant philologist turned himself into an even more brilliant speleologist of the soul. In his writings, he - like an alchemist - transfigured his pain, his anguish, and his despair into thought, into poetry, and into philosophy. Ultimately, it was in the abysmal abyss of psychosis that he perished, because the odyssey into the soul's recesses of both the unknown and the unknowable, into the unbearable loneliness of being, is not without peril. The mental catastrophe may have been the price Nietzsche paid for his Colombian adventure. Also, quite possibly, the creativity kept the madness at bay so that his "crashing down" was delayed for years.

Nietzsche often evoked an image of a star, no doubt identifying himself with this celestial body. Studying his Arbeitskurve, I have observed that he usually wrote no more than two books per year, often just one. In his last productive year of 1888, however, he "emitted" at least five books, shorter but of high energy. In physics, such high emission of energy is held to occur when the nucleus of the atom is unstable and "the centre cannot hold".

Cosmologists maintain that the dying stars shine the brightest, and perhaps Nietzsche was no exception.

Acknowledgements

I thank an anonymous reviewer and K. Rushton for their critical comments and suggestions regarding an earlier version of this paper. I remain deeply indebted to the Editor-in-Chief of the IPJP, Professor C. R. Stones, and the Journal's Language and Copy Editor whose professionalism, diligence and friendliness has made these 12 years of collaboration not only a very enriching but also a joyous experience.

References

Andreasen, N. C. (1987). Creativity and mental illness: Prevalence rates in writers and their first-degree relatives. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(10), 1288-1292. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.10.1288 [ Links ]

Andreasen, N. C. (2005). The creative brain: The science of genius. New York, NY: Penguin Group. [ Links ]

Bertram, E. (2009). Nietzsche: Attempt at a mythology (R. E. Norton, Trans.). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. (Original work published 1918) [ Links ]

Bridgwater, P. (1978). English writers and Nietzsche. In M. Pasley (Ed.), Nietzsche: Imagery and thought: A collection of essays (pp. 220-258). London, UK: Methuen. [ Links ]

Carter, C. M. (2015). The relationship between cognitive inhibition, mental illness, and creativity. Theses and Dissertations. 263. Available at http://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/263 [ Links ]

Carson, S. H. (2014). Cognitive disinhibition, creativity and psychopathology. In D. K. Simonton (Ed.), The Wiley Handbook of Genius (pp. 198-221). Wiley Online Library: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi: 10.1002/9781118367377 [ Links ]

Cybulska, E. M. (2000). The madness of Nietzsche: A misdiagnosis of the millennium? Hospital Medicine, 61(8), 571-575. doi: 10.12968/hosp.2000.61.8.1403 [ Links ]

Cybulska, E. M. (2008). Were Nietzsche's cardinal ideas delusions? Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 8(1), 1-13, doi: 10.1080/20797222.2008.11433959 [ Links ]

Cybulska, E. M. (2009). Oedipus: A thinker at the crossroads. Philosophy Now, 75 (September/October), 18-21 [ Links ]

Cybulska, E. M. (2013). Nietzsche's eternal return: Unriddling the vision. A psychodynamic approach. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 13(1), 1-13. doi: 10.2989/IPJP.2013.13.1.2.1168 [ Links ]

Cybulska, E. M. (2015a). Nietzsche's Übermensch: A glance behind the mask of hardness. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 15(1), 1-13. doi: 10.1080/20797222.2015.1049895. [ Links ]

Cybulska, E. M. (2015b). Freud's burden of debt to Nietzsche and Schopenhauer. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 15(2), 1-15. doi: 10.1080/20797222.2015.1101836 [ Links ]

Cybulska, E. M. (2016). Nietzsche contra God: A battle within. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 16(1 & 2), 1-12. doi: 10.1080/20797222.2016.1245464 [ Links ]

Eysenck, H. J. (1995). Genius: The natural history of creativity. Cambridge, UK.: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Freud, S. (1985). The interpretation of dreams. In A. Richards (Ed.) & J. Strachey (Trans.), Pelican Freud library (Vol. 4). Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. (Original work published 1900) [ Links ]

Freud, S. (1985). The "uncanny". In A. Dickson (Ed.) & J. Strachey (Trans.), Pelican Freud library (Vol.14, pp. 335-376). Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. (Original work published 1919) [ Links ]

Frith, C. D. (1979). Consciousness, information processing and schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 134(3), 225-235. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.3.225 [ Links ]

Gray, J. (2013). Henri Poincaré: A scientific biography. Princeton, NJ & Oxford, UK: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Greenwood, T. A. (2016) Positive traits in the bipolar spectrum: The space between madness and genius [Book review]. Molecular Neuropsychiatry, 2(4),198-212. doi: 10.1159/000452416 [ Links ]

Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and time. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers. (Original work published 1926) [ Links ]

Higgins, K. M. (1987). Nietzsche's Zarathustra. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. [ Links ]

Jamison, K. R. (1993). Touched with fire: Manic-depressive illness and the artistic temperament. New York, NY: Free Press. [ Links ]

Jaspers, K. (1997). Nietzsche: An introduction to the understanding of his philosophical activity (C. F. Wallraff & F. J. Schmitz, Trans.). Baltimore, MD & London, UK: Johns Hopkins University Press. (Original work published 1936) [ Links ]

Kane, J. (2004). Poetry as right-hemispheric language. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 11(5-6), 21-59. [ Links ]

Kant, I. (1978). Anthropology from a pragmatic point of view (H. H. Rudnick, Ed. & V. L. Dowdell, Trans.). Carbondale and Edwardsville, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1798) [ Links ]

Kandel, E. R. (2018). The disordered mind: What unusual brains tell us about ourselves. London UK: Robinson. [ Links ]

Klossowski, P. (1997). Nietzsche and the vicious circle (D. W. Smith, Trans.). London, UK: Athlone Press. (Original work published 1969) [ Links ]

Koestler, A. (1964). The act of creation: A study of the conscious and unconscious in science and art. New York, NY: Dell Publishing Co. [ Links ]

Kraepelin E. (1921). Manic-depressive insanity and paranoia (G. M. Robertson, Ed. & R. M. Barclay, Trans.). Edinburgh, UK: Livingstone. (Original work published 1913) [ Links ]

Krell, D. F., & Bates, D. L. (1997). The good European: Nietzsche's work sites in word and image. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Kris, E. (1952). The psychology of caricature. In Psychoanalytic explorations in art (pp. 173-188). New York, NY: International Universities Press. (Original work published 1936) [ Links ]

Kristeva, J. (1984). Revolution in poetic language (M. Waller, Trans.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Ludwig, A. M. (1995). The price of greatness: Resolving the creativity and madness controversy. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Luke, F. D. (1978). Nietzsche and the imagery of height. In M. Pasley (Ed.), Nietzsche: Imagery and thought: A collection of essays (pp. 104-122). London, UK: Methuen. [ Links ]

MacLeish, A. (1985). Ars Poetica. In Collected Poems 1917-1952. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [ Links ]

MacLeod, C. M. (2007). The concept of inhibition in cognition. In D. S. Gorfein & C. M. MacLeod (Eds.), Inhibition in cognition (pp. 2-23). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Malinowski, B. (2013). The problem of meaning in primitive languages. In C. K. Ogden & I. A. Richards (Eds.), The meaning of meaning: A study of the influence of language upon thought and of the science of symbolism (2nd ed. rev., pp. 296-336). Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publishing. (Original work published 1923) [ Links ]

Marsden, J. (2002). After Nietzsche: Notes towards a philosophy of ecstasy. New York, NY: Palgrave-Macmillan. [ Links ]

Mednick, S. (1962). The associative basis of the creative process. Psychological Review, 69(3), 220-232. doi: 10.1037/ h0048850 [ Links ]

Middleton, C. (Ed. & Trans.). (1996). Selected letters of Friedrich Nietzsche (2nd ed.). Indianapolis, IN and Cambridge, MA: Hackett Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Nasar, S. (1998). A beautiful mind: The life of John Nash. London, UK: Faber and Faber. [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (1968). The will to power (W. Kaufmann & R. J. Hollingdale, Trans.). New York, NY: Vintage Books. (Original work written 1883-1888 and published posthumously 1901) [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (1969a). Thus spoke Zarathustra (R. J. Hollingdale, Trans.). London, UK: Penguin Books. (Original work published in four parts 1883-1885) [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (1974). The gay science (W. Kaufmann, Trans.). New York, NY: Vintage Books. (Original work published 1882, and 2nd ed. with preface and Book V 1887) [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (1976a). Mixed opinions and maxims. In W. Kaufmann (Ed. & Trans.), The portable Nietzsche (pp. 64-67). New York: Penguin Books. (Original work published 1879) [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (1976b). Twilight of the idols. In W. Kaufmann (Ed. & Trans.), The portable Nietzsche (pp. 463-563). New York, NY: Penguin Books. (Original work published 1889) [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (1976c). The antichrist. In W. Kaufmann (Ed. & Trans.), The portable Nietzsche (pp. 565-656). New York, NY: Penguin Books. (Original work written 1888 and published 1895) [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (1976d). On truth and lie in an extra-moral sense. In W. Kaufmann (Ed. & Trans.), The portable Nietzsche (pp. 42-47). New York, NY: Penguin Books. (Original work written 1873 and published 1896) [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (1982). Daybreak: Thoughts on the prejudices of morality (R. J. Hollingdale, Trans.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1881) [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (1986). Ecce homo: How one becomes what one is (R. J. Hollingdale, Trans.). Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. (Original work written 1888 and published posthumously 1908) [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (1990). Beyond good and evil (R. J. Hollingdale, Trans.). London, UK: Penguin Books. (Original work published 1886) [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (1993). The birth of tragedy out of the spirit of music (S. Whiteside, Trans.). London, UK: Penguin Books. (Original work published 1872) [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (1994). On the genealogy of morality: A polemic (K. Ansell-Pearson, Ed.; C. Diethe, Trans.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1887) [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (1999). Also sprach Zarathustra. Kritische Studienausgabe, Band 4 (G. Colli & M. Montinari, Eds.). Berlin, Germany: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag de Gruyter. (Original work published 1883-1885) [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. (2012). On moods. In The Nietzsche Channel (Trans.), Nietzsche's writings as a student: Essays and autobiographical works written from 1858-1868 (pp. 109-114). Ebook: The Nietzsche Channel (http://www.thenietzschechannel.com). (Original work written 1864) [ Links ]

Nietzsche Source. http://www.nietzschesource.org/ [ Links ]

Pasley, M. (Ed.). (1978). Nietzsche: Imagery and thought: A collection of essays. London, UK: Methuen. [ Links ]

Plato, (1997). Phaedrus (A. Nehamas & P. Woodruff, Trans.). In J. M. Cooper & D. S. Hutchinson (Eds.), Plato: Complete works (pp. 506-556). Indianapolis, IN/Cambridge, UK: Hackett Publishing Company. (Original work written ca 370 BC) [ Links ]

Popper, K. (2005). The logic of scientific discovery (2nd ed.). London, UK & New York, NY: Routledge Classics. (Original work published 1959) [ Links ]

Rothenberg, A. (1990). Creativity & madness: New findings and old stereotypes. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Sass, L. A. (1992). Madness and modernism: In the light of modern art, literature, and thought. New York, NY: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Schopenhauer, A. (1969). The world as will and representation (Vol. 1) (E. F. J. Payne, Trans.). New York, NY: Dover Publications. (Original work published 1818) [ Links ]

Sophocles, (1906). Antigone. In The plays and fragments: Part III (R. C. Jebb, Trans.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. (Original work written ca 441 BC) [ Links ]

Young, J. (2010). Friedrich Nietzsche: A philosophical biography. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

About the Author

Eva Maria Cybulska is a retired consultant psychiatrist living in London. She obtained a medical degree (with distinction) in the early 1970s from Gdansk Medical School (Poland) and did all her psychiatric postgraduate training in London afterwards.

Most of her life, she has been fascinated by literature, music and philosophy, and later by psychiatry, with all its drama. After taking an early retirement some 15 years ago, she has been able to devote her life more fully to these passions and has published extensively on related topics. Please visit her blog:emcybulska.blogspot.com/

1 In Oedipus Tyrannus by Sophocles, which was well known to Nietzsche, Oedipus consults the Delphic oracle about the plague that overwhelmed Thebes. In order to combat the plague, he pleads with Apollo to indicate what he should do or say. For a discussion regarding the tension between magical and rational thinking in ancient Greece, see my article Oedipus: A thinker at the crossroad (Cybulska, 2009).