Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology

versão On-line ISSN 1445-7377

versão impressa ISSN 2079-7222

Indo-Pac. j. phenomenol. (Online) vol.14 no.2 Grahamstown Out. 2014

Becoming a Xhosa healer: Nomzi's story

Beauty N. Booi; David J. A. Edwards

ABSTRACT

This paper presents the story of an isiXhosa traditional healer (igqirha), Nomzi Hlathi (pseudonym), as told to the first author. Nomzi was asked about how she came to be an igqirha and the narrative focuses on those aspects of her life story that she understood as relevant to that developmental process. The material was obtained from a series of semi-structured interviews with Nomzi, with some collateral from her cousin, and synthesised into a chronological narrative presented in Nomzi's own words. The aim of the study was to examine her account of her unfolding experience within three hermeneutic frames. The first is the isiXhosa traditional account of what it is to become an igqirha, a process initiated by intwaso, an illness understood to be a call from the ancestors, and guided by messages from the ancestors in dreams and other symbolic communications. The second is the perspective of Western Clinical Psychology on the cognitive, emotional and behavioural disturbances that characterise intwaso. The third is the perspective of transpersonal psychology on the nature and development of shamanic healing gifts, as understood from observations of such practices in traditional societies across the world. As the narrative of Nomzi's story is quite long, this paper presents her narrative as well as the methodology which gave rise to it. The interpretative review of the material from each of the three perspectives is presented in a second paper.

Transpersonal psychology (Walsh & Vaughan, 1993) is based on the view that spiritual development and transformation can be understood as human processes that are separate from, although interpenetrating with, other developmental processes, such as those of cognitive development as initially described by, for example, Piaget and Vygotsky (Goswami, 2014), relational development as described in attachment theory, or the development of personality as individuals cope with challenges, distress and trauma within the developmental process, as described by many theories of personality (Blatt & Levy, 2003; Pearlman & Courtois, 2005; Sroufe, 2005). What sets spiritual development apart is that it refers to the development of, attunement to and engagement with realities that lie outside the space-time co-ordinates defined by the science of physics at the end of the nineteenth century (before the emergence of relativity theory and quantum mechanics) (Singer, 1990). In the early twentieth century, pre-twentieth century physics, often called Newtonian physics because of Newton's pioneering role in setting out its fundamental laws, would be disclosed as a narrow band within a broader, more mysterious reality in which time and space were interconnected, where the apparently rigid boundaries set by time and space did not apply, and where 95% of the universe would be hypothesised to be dark matter or dark energy, in principle unknowable to science ("Dark Energy, Dark Matter", 2014).

Because the parameters of Newtonian physics fit large domains of human lived experience, there are still many who, over a century later, are closed to the investigation of experiences that seem to transcend Newtonian space and time. However, research in the phenomenological tradition, and the experiential practices of the humanistic psychotherapies, have disclosed the widespread nature and availability of lived experience that does not fit the Newtonian mould (Valle, 1989). Indeed, much of the critique by phenomenological writers of scientific positivism has been centred on just how many important dimensions of human experience cannot be captured within the Newtonian framework's narrow confines of logic, reason and formal experimentation.

Many cultures and traditions describe processes of development that suggest an engagement with dimensions and aspects of reality that transcend space and time. The path of shamanic initiation is one kind of process that is widely described, with commonalities that are found across cultures and regions (Doore, 1988; Krippner, 2000; Walsh, 1990). Although the term "shaman" is from Siberia and refers to traditional healers there, it has been appropriated to refer to a wide range of healers from traditional cultures where it is understood that a shaman/healer must undergo a profound and often disorienting process of personal transformation. Within transpersonal psychology, this is called "spiritual emergence" (Grof & Grof, 1989). It is not like going to medical school and learning information and techniques, although information and techniques are involved. But individuals must be changed in the way they experience the world and others, and in the process learn to attune to realities that transcend space and time.

This process of transformation may come from a spontaneously occurring process which is understood as a calling by some unseen presence. Among traditional healers in Southern Africa, this call is understood to come from deceased ancestors who may have been healers themselves. Among the Xhosa, the process is called intwaso (which literally means "spiritual emergence") or ukuthwasa (as a verb meaning "to emerge as a healer"). Intwaso usually presents itself in the form of a mysterious illness, physical or psychological, that does not respond to treatment. This is accompanied by dreams in which ancestors appear or are represented symbolically. There may also be waking visions, understood, from a transpersonal perspective, as experiences in altered states of consciousness, but as hallucinations from the perspective of positivist science. The impact of intwaso is often severely disabling unless the process is channelled into a transformation process by a guide (Buhrmann, 1986; Hirst, 2005).

In some cultures, the transformation process may be sought and activated by psycho-spiritual technologies in which altered states of consciousness are deliberately induced, for example by meditation practices, trance dancing, rituals and the use of psychedelic substances. Such substances are not readily available in Southern Africa, however, although psychedelics such as iboga play this role in central Africa (Stafford, 1992). Whether or not psychedelics are used, the transformation process can be stormy and disorienting, and may call for periods of seclusion in a context where individuals can work with their dreams and with ritual practices to move the process forward under the guidance of individuals who have been through the process themselves and reached integration and resolution. The process can have a benign outcome, where initiates, having successfully navigated the stormy waters of transformation, graduate to a stable state where they can, as Buhrmann puts it, live effectively in two worlds, the world of ordinary practical life, and the spiritual world. The graduate is a shaman, and, among the Xhosa, the term used is igqirha (traditional doctor or healer) (Buhrmann, 1986).

Aims of the Study

The aim of this research was to write a case study of the developmental trajectory of the intwaso process in a Xhosa igqirha that would allow for an in-depth examination of the experiences of the call and transformation process in one individual identified as having gone through it. The intention was that the study would be phenomenological and hermeneutic. It would be phenomenological in that it would draw out as far as possible important features of various experiences that were part of the process, and it would be hermeneutic in that the bare narrative of the participant's experiences would be examined through a series of interpretative lenses: the perspective of the Xhosa tradition, the literature on shamanism within the broader framework of transpersonal psychology, and the perspective of western medicine (and psychiatry and clinical psychology in particular). This is elaborated at the end of the Method section.

Method

A psychological case study is essentially a reconstruction and interpretation of one or more major episodes in a person's life. It is selective in that it addresses itself to particular issues and themes, and ignores others. Thus some facts about the person and the situation are relevant to those issues and so constitute evidence, whereas others are not. However, a case study is not only about the individual whose case is being examined. It is about the category of experience which the case represents: in this case, the processes involved in intwaso and the development towards becoming a healer (Bromley, 1986).

A narrative account of an individual's experiences as they unfold over time allows for an examination of how the processes evolve and for theoretical reflection on the nature of that development. Depending on the nature and quality of the case material, the enquiry may be primarily exploratory and descriptive or it may engage critically with existing theory or even provide tests of specific propositions within existing theory (Edwards, 1998). Since there is already a rich literature on Xhosa cosmology and intwaso, it was expected that the case material would allow for specific questions about the process to be examined.

The Research Participant

Nomzi (pseudonym) was a 67-year-old Xhosa-speaking Mfengu woman, a member of the OoRhadebe clan, living in Queenstown in the Eastern Cape. She was a teacher by profession and had never married. She appeared to meet the criteria for this kind of research as summarized by Stones (1988, p. 150). She had undergone the process of intwaso, and was currently practising as an igqirha. She was verbally fluent and able to communicate her feelings, thoughts and perceptions in relation to the researched phenomenon (although there were limitations here that will be discussed later). She had the same home language as the interviewer (the first author) and expressed her willingness to be open to the researcher. Furthermore, Sandile, a 68-year-old male cousin, who lived in the same town and knew Nomzi well, was willing to provide a collateral account of some of the significant events in her life, which would provide a way of checking on the trustworthiness of her own accounts, a procedure recommended by Robson (2002) and Yin (2003).

Both Nomzi and Sandile were approached individually by the first author at their respective homes, and invited to participate as required. They were both informed of the interviewer's qualifications, and given a clear and transparent account of the nature of the study, as well as of the ways in which privacy and confidentiality would be ensured. In line with an ethical protocol approved by Rhodes University, both participants signed a form in which they gave consent and agreed that the interviews could be recorded.

Data Collection and Transcription

As recommended by Marshall and Rossman (1989), the interviews with Nomzi were more like conversations than formal, structured interviews. The interviewer took time to establish rapport and ensure that Nomzi felt at ease. Each interview was based on an interview guide, which is a series of topics or broad questions used as prompts. These ensured that the interview remained focused on issues of relevance and concern and covered specific issues and topics. This guide was developed and expanded after each interview (Barker, Pistrang, & Elliott, 2002; Taylor & Bogdan, 1998). A series of four interviews was conducted with Nomzi. By then it was judged that sufficient information had been gathered about significant experiences related to the intwaso process, that points of interest had been followed up, and that aspects that were not clear had been clarified. A single interview of about an hour was conducted with Sandile. This focused on getting collateral accounts of some of the events in Nomzi's narrative at which he had been present.

All the interviews were recorded. The recordings were transcribed verbatim. This included making notes on hesitations, pauses and irregularities of speech. Pseudonyms were used for the participants, and some places and people's names were changed in the transcript in order to protect the identity of individuals. To verify the accuracy of the transcripts, a person with an Honours Degree in Psychology from Rhodes University checked a random selection of the transcripts against the recordings.

Data Reduction

Data reduction is "the process whereby a large and cumbersome body of data is organised into a manageable form both for the researcher to work with and for presentation" (Edwards, 1998, p. 61). This involved selectively summarizing and organizing the interview material into a chronological narrative. Material was selected that was directly relevant to several central themes: a chronology of major events in Nomzi's life, illnesses and behavioural disturbances, dreams and visions, training as a healer, and working as a healer. The narrative presented below as "Nomzi's story" was written in the first person from Nomzi's point of view and was largely non-interpretative. As a validity check, the completed narrative was shown to Nomzi who was asked to comment on whether it was an accurate reflection of her experience (Richardson, 1996). She was happy with the way it had been written.

Data Interpretation

"In hermeneutic work," argues Edwards (1998, p. 52), "researchers appropriate a body of theory, not as if it were absolute truth but with the recognition that it is historically and culturally constructed". He adds that "the success of a hermeneutic case study depends on whether the writer can successfully make a case for the relevance of the hermeneutic frames that have been appropriated".

The completed case narrative was subjected to a series of hermeneutic readings using the reading guide method. It was considered appropriate that the first reading should be from the perspective of the Xhosa tradition with its specific cosmology, including beliefs about how the ancestors call the initiate to the intwaso process, given that this was the framework within which Nomzi herself understood her story. This reading was initially written by the first author. However, Manton Hirst, an anthropologist with a specialized knowledge of Xhosa traditional healing (Hirst, 1997, 2005), who had himself been through the intwaso process under the guidance of a Xhosa igqirha, subsequently read the case study and contributed additional interpretative insights. The second reading focused on the kind of diagnosis and interpretations that are likely to be made when such individuals come to the attention of the health care system. In particular, it used the framework of clinical psychology, including the concepts and categories of diagnosis used in psychological assessment based on attachment theory, developmental psychology and theories of psychotherapy. This approach has recently been summarized by Edwards and Young (2013). The third reading was located within the framework of transpersonal psychology and the broader literature on shamanism and spiritual emergence referred to in the introduction to this paper. These three readings each serve to provide what Brooke (1991) has called "hermeneutic keys" that can open the door to a deeper understanding of Nomzi's experience.

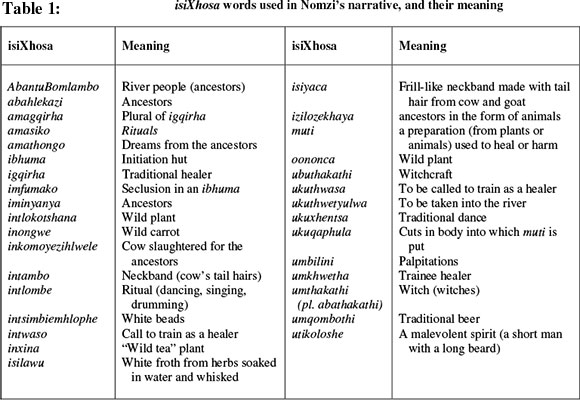

The original narrative is quite long, although it has been abbreviated somewhat for the purposes of this paper. The interpretative phase of the research is therefore presented in a separate paper (Edwards, Hirst, & Booi, 2014). Several Xhosa words are included in the narrative and, for the reader's convenience, their meaning and significance has been summarized in Table 1 below.

Nomzi's story

Childhood and Adolescence

I, Nomzi Hlathi, an igqirha, was born in 1937 in District Six in Cape Town, the third of six children, four boys and two girls. In 1949 we children were taken to Queenstown, where we grew up in our maternal grandmother's home, while our parents remained in Cape Town where they worked. In July 1951, when I was 14 and in Standard 6 (Grade 8), we were taken to court in King William's Town to attend our parents' divorce case. My mother was given custody of the children. Later that year, our father abducted me and my two brothers from our grandmother's house to Cape Town, where he was living with his new wife. There, I became very ill, and my whole body was full of pain as if something had beaten me. I was taken to different doctors, but none could detect what was wrong with me. My father and aunt took me to Barbi, a Muslim healer, who gave me a brown paper to hold and he lit a white candle. Words appeared on the brown paper, which I could not read. Barbi spoke to my father in English, but I could not understand what he was saying. After we went home, my mother fetched me, but she had no place of her own, as she was staying in her employer's house, so I was taken to my father's brother. On my first night there, I had incontinence of urine, and my father's brother suggested that we be taken back to our maternal home in Queenstown.

In Queenstown, I was taken to Dr Sher, a homeopath, who asked me to sit on the floor on the skin of a white goat. I became incontinent of urine for the second time. In the waiting room, the doctor spoke to my grandmother, who never gave me feedback about what the doctor had said. At home I did not want to sleep on the bed or with other children because they laughed at me [presumably because of the bedwetting]. So I slept on a sack on the floor. That night I dreamt of a striped cat, gnawing and scratching me gently. I was woken up by my grandmother and was asked why I was laughing during my sleep, and I explained my dream to her. I lost a lot of weight because I had a very poor appetite. I used to take only two spoons of food and would feel full. One day I had a waking vision of someone coming to our home who was umkathi with harmful muti, and described the person to my Grandmother. The next day that person came into the house and I hid in the bedroom. When my grandmother called me to make tea for the visitor, I suddenly lost energy and began to cry. When she left the house, I regained my energy and I was able to stand up. My grandmother beat me, thinking that I was defiant. When she woke up the following morning, her arms and hands were swollen and painful. She reported that she had dreamt of my grandfather warning her not to beat me again, as my behaviour had not been deliberate.

One morning I woke up having dreamed of two old men wearing khaki clothes. One of them told me to go to Whittlesea, where my father's family were, and to ask them to make an intambo for me. He described the type that was to be made. I began to lose more and more weight. My grandmother took me to Whittlesea. My father arrived from Cape Town, reporting that my grandfather spoke to him through a dream, telling him that I was sick and that he should go home and perform a ritual for me. Relatives were invited to the intambo ceremony, and my father's brother interceded with the ancestors on my behalf. My father removed hairs from the cow's tail, and my aunt made me the intambo which was put round my neck at the cattle byre. There I sat down and fell asleep on the cow dung. I dreamt of two old men wearing grey blankets seated inside the cattle kraal. They introduced themselves as my great-grandfathers, and said that they were Green and Ndaleni. They told me that there is a lot of work for me to do out there. I was woken up by rain drops. I had missed the slaughtering of a goat which was part of the ceremony and people were already eating. After this, I regained my energy and felt much better physically.

We went back to Queenstown the following morning, and on waking next day I had a vision of a baboon covered with a blanket, seated behind the curtain of some tenants' room (the tenants had already left for work). I reported this to the adults. Neighbours were called to check, and a small baboon was discovered. Afterwards, the tenants were sent away from that room because baboons are used by abathakathi who ride them in the night. One night I dreamt of something heavy on my feet. It was a large brown and gold cat. I was not frightened, but I was told by a voice that this was one of the izilozekhaya.

When I played with other children in the street, I would either make them angry or become angry when provoked, and end up assaulting them. There was one girl whose face I cut with my nails, and she bled as if she was cut by a blade. I did not know how that happened as I was very angry. One day, another girl asked me to play with her. I saw her walking with utikoloshe and asked her why. My grandmother overheard me. She told her I was "sick" and asked her to go home. Later, she beat me, but when she awoke the next morning her hand was swollen, and she could not use it. I was not allowed to play with others anymore. When I was sent to the shops, I had to go straight there and come back. In one of the shops, I saw a big frog on top of the counter and I ran back home. Other children gave me the nickname of Nomtobhoyi (a strange or odd person).

Wherever I wanted to go, I had to get permission from the ancestors. They would talk into my ears and ask me not to go if they disapproved of the journey. I used to drink water from where cows were drinking and become full and satisfied. I saw people in the fields digging out inongwe, intlokotshana and oononca to eat, and I did the same. In dreams, the ancestors told me to dig out roots that I had to grind and soak in cold water and drink. The mixture tasted very good, and I drank it daily as prescribed. I also used it for washing my body. When my grandmother asked someone what that muti was, she was told it was isilawu. I also used to dream of the river, and myself inside that water.

One day I was seated in the house, facing towards the door, when I smelt a goat and had a vision of a white goat at the door, with big breasts hanging down. It was bleating and was looking at me. I told my grandmother, but she could not see the goat. This was believed to be an indication that a goat had to be slaughtered for me. The intambo that I wore was lost and I dreamt that a larger isiyaca necklace was supposed to be made for me. A goat was slaughtered, and isiyaca was made from usinga, a tough string-like muscle from a slaughtered goat, white goat's hair, hair from a cow's tail and white beads sewn onto it. After this, I was able to play with other children. When I had a vision, I would not say anything about it until I arrived home and told my grandmother.

I used to move between my paternal and maternal homesteads, but, in the paternal home, I did not sleep in the house but outside. When I felt like going, I did not report to anyone but just left. I dreamt of my ancestors telling me to go to Whittlesea and sit inside the cattle byre. I went there, arrived in the afternoon, and I entered the kraal without my relatives seeing me. I spent the whole night among the sheep; it was warm and comfortable there. I was only seen by boys who came to take the sheep out in the morning. My paternal family met and discussed my vagabonding. One of my uncles told me to stay put in my maternal home. He explained that I could not sleep inside the house when I was there because my father was staying in Cape Town and did not have a house of his own here, but only his parents' home in Whittlesea. After that, I stayed in my maternal home and continued taking my medicinal roots.

The ancestors used to talk to me through dreams, and they sent me to people who needed help. For example, there was an old woman who needed someone to help her with household chores, and I used to go and help her. One night I was told in my dream to go and dig out a plant called inxina and plant it in my garden, which I did. One day, when I was at home, I saw a dog urinating on the tree I planted, and I threw a stone at it, and my hand began to shake. That night, I dreamt of many dogs that came and surrounded me. I was so frightened that night, but I was told not to hit dogs anymore, as they are izilozekhaya.

Pupils at school gave me the nickname of "Joseph the Dreamer", as I was always dreaming. In September 1954 [aged 17], when I was preparing for my form III examinations, I saw a question paper in my dream, and I told my friends about it. In November, the questions were just as I had dreamed them and I wrote my examinations and passed my Junior Certificate.

Early Adulthood and First Training by an Igqirha

In 1955, I started a teacher's course, in Transkei. I repeatedly dreamt of the same old man whom I did not know. He called me by name. He also called me "Grandchild" and asked me to respond to his call. He said I should avoid four of my dormitory mates and not give my school books to them. In a dream the following night, two of these four appeared standing next to my bed and attacking me. I fought back, and was woken up by other students telling me that I was hitting out and boxing in the air. The people that I alleged to be fighting me were sleeping in their beds. After this, the matron removed me from the dormitory to sleep in her house for three weeks. She also requested my mother to come to school as I was behaving strangely. When I described the old man to my mother, she told me that it was my paternal grandfather. The matron released me to go home and we left on a Friday by bus. My mother took me to a traditional healer at Qumbu. We stayed in the house of a man who used to be a tenant at home in Cape Town. There were many dogs, but they never even barked at me. I was given pork to eat, but I refused to eat it, as it was one of the foods I did not like. That night I slept outside with the dogs. I plugged my ears with cotton wool and slept with them, but when I woke up, the plugs were removed from my ears. I was not afraid of those dogs, and one which was regarded as very aggressive used to lick me. During the day, I played with them, and when I was given food to eat, I took it and ate it with the dogs. People commented about my behaviour and they were wondering what type of a teacher I was going to be.

On the Wednesday, my mother brought a woman called Mambhele who wore a white traditional dress with black binding on the seams. Seeing me among the dogs, she commented that I belonged to abahlekazi. That night, I shared the same room, a rondavel, with her. She did not talk much and she was smoking a pipe and spitting on the floor. I dreamt of my grandfather again, saying that I should listen to all that was going to be said to me and follow instructions. In the morning, I went to my mother and told her the dream. She told me to tell it to Mambhele, which I did. I was surprised when she told me that she also saw the same old man at night, wearing khaki clothes. She gave me herbs to add to the water and wash with. She mixed Vaseline with other herbs and told me to apply it to my body, and she told me that the mixture would last until the September holidays. My mother arranged for my next visit to Mambhele in the December holidays, so I went back to Qumbu. Mambhele washed me with herbs and did gastric lavage. She gave me ointment to take back to school and told me that she was not going to do ukuqaphula (which involves making cuts in the body and applying muti to them).

In 1956, back at the college, I was promoted to course II despite having missed most of the lectures and assignments due to my "sickness". I was allocated to a first year dormitory and separated from the teacher trainees. Every morning, the matron asked me about my dreams. She wrote them down and gave me sweets to eat. I only realized later on that she was using them for gambling on horses or for umtshayina, a form of betting conducted by some Chinese people.

At the end of the year I went back to Queenstown. The ancestors communicated with me through visions and intuitions about evil things that were going to happen, telling me that I would have severe palpitations, sweating and loss of energy. For example, one day when I was preparing to go out with friends, a human figure appeared and ordered me not to go there, as something evil was planned against me. I felt dizzy and light-headed, as if I was being swept away by the river. I once went to a place by car despite my ancestors' warning me not to go there. An accident happened and the car was damaged, but I came out uninjured.

I had intuitions when people carried charms with them either to protect themselves or to harm others. In 1959, I saw a bright light between the breasts of a certain lady. There was a small bottle of muti that looked like an ampoule of the kind used by amagqirha. I asked her why she had that between her breasts, but she denied that there was something. She was embarrassed and did not allow me to come closer. Sometimes when I touched someone's handbag that had harmful muti inside, my hands would shake until I put it down. One day a woman visited at home. When I looked at her, I experienced umbilini and my body felt weak. I tried to run to the bedroom to hide, but it was locked, and so I had to face her with all the bad feelings I had. She stood still like a zombie, and a white rat fell down from between her legs. She became embarrassed and bent down.

The rat ran back and hid under her dress. Another example is of an old woman I used to tell my grandmother about. I also had bad feelings when I saw her. I felt that she was using harmful muti and that she was a witch. One day in church, as we were singing, she tried to run away to the door, but it was too late, because a lizard fell down from her skirt and she was embarrassed in front of the people.

When someone evil came to visit me, I had a weird feeling before she or he arrived. When that person knocked at the door, I could not answer it. I felt cold and shivered, would become angry and aggressive, and my voice would not come out. The ancestors would close the door as if it was locked and the person would end up going away. I would hear the voice telling me that the visitor is evil, and that I should avoid her or him. One day I returned from a funeral with my friends. When we arrived home, I removed my pantyhose in order to feel comfortable. After my friends had left, a voice told me that one of them took my dirty pantyhose to bewitch them. I sent a child to go and get them, but she denied that she took them. The ancestors brought them back and they were there lying on the floor. A voice told me to soak them with methylated spirits and burn them.

The ancestors warned me through a dream not to lend my clothes to people, but I lent my jersey to a friend. When she brought it back, a voice told me to burn it. One of my relatives asked me to give it to her and not to burn it, and I did that. She took it and washed it, and immediately she got blisters on her hands. So we ended up burning the jersey. The voice of the ancestors told me to apply pork fat on her blisters; we bought it and she applied it and the blisters were healed.

My grandmother was surprised that my intuitions were correct. She also asked me to stay at home and not to visit other people's houses because when I had a vision of something bad in the neighbourhood, I did not keep quiet but told them what I was seeing, and this caused tension and embarrassment to them.

In 1961, at the age of 24, I went to Cape Town to see my father. On my way, the ancestor's voice asked me why I ran away from home, and told me that I was going to experience problems on the way. I lost my suitcase at the Cape Town railway station, and was helped by a man who paid for my bus fare and took me to my father. My father went to look for my suitcase the next day and found it in the cloak room. A goat was slaughtered for me, umqombothi was brewed, and people ate and drank. Intsimbiemhlophe was made for me to wear around the neck, but it broke. I was told in a dream that a cow should be slaughtered next time. After the ceremony, I became homesick, and stole money from my father to buy a train ticket to Queenstown. A year later, at Whittlesea, my paternal family performed the inkomoyezihlwele ritual and slaughtered a cow for me as I had dreamt.

In 1965 [aged 28], I worked as a teacher in Alice. I despised the other teachers, isolated myself, was very irritable and rude and did not want anything to do with them. Although I had intwaso, I had not yet been trained to divine and heal people. I still needed to undergo ukuthwasa training. One Friday night I was told in a dream to go to an igqirha who was going to be my trainer. I saw her house (three rondavels) at the Melani Administrative Area in Alice. Next day, I walked to the place and found the three rondavels as I saw them in my dream. A woman called Mamjwarha was cooking outside on an open fire. She took me on as an umkhwetha and gave me herbal preparations to wash with and to drink. She told me that I was chosen by the ancestors but there was still a lot to be done on me and I was not supposed to have started working yet. She gave me the same isilawu to drink as I used to prepare for myself at home. Mamjwarha taught me how to divine and find out what was wrong with people and treat them. She also taught me to strengthen homes, as a preventative measure against evil spirits. I visited her on alternate weekends and would return home on Sunday so I could go to work the following day.

One morning, going to Mamjwarha's house, I was nearly swept away by the Thyume river which I had to cross over by stepping stones. I was nearly ukuthwetyulwa. The water formed a cone-like shape where I was going to go in. I cried and asked my ancestors to bear with me, as my mother had no money to pay for all the necessary procedures. I requested them not to take me into the river, but to allow me to train outside. When I arrived at Mamjwarha's place, she laughed at me and told me that she did not expect to see me as she was told by the ancestors that they were going to take me into the river. She said that it was going to make things easier for her. After that incident I developed a phobia of water. I was afraid of the sound of water, and even the sight of water in the washing basin. That afternoon, I accompanied Mamjwarha's daughters to fetch water from the river. When I was still standing on a steep slope, water came to me, trying to sweep me away again, but I held tight onto the tree branch, and escaped. I went back to the house to sleep. I then dreamt the house was being swept away by the water, and I cried in my sleep, waking other people up. After that, I became more hydrophobic. When crossing the bridge, I felt as if the water was covering me, and I experienced tightness of the chest. I then decided to resign from my teaching post in Alice.

In 1969, I worked at Ilinge, quite far from Qumbu, so I did not go to Mamjwarha regularly. I would only contact her when a ritual was to be performed. I used to take my pupils to the mountains to learn about wild plants. Then I would get a chance to dig out medicinal roots for myself. One day at the school where I was teaching, a garden spade was missing. We called all the boys who were working in the garden the previous day. They all denied that they took the spade. A voice told me the name of the boy who stole it, and I had a vision of the spade behind the door at his place. I just called the boy by name, and asked him to bring the spade back. Two other boys accompanied him home to fetch it and found it behind the door.

Graduation and Practice as an Igqirha

Finally, in 1998 [aged 61], I became an igqirha. I had difficulty in walking, something the ancestors had warned me of in a dream as they said I was ignoring their call. An imfukamo ritual was performed in which I was secluded Saturday to Sunday morning in an ibhuma built from reeds and leaves next to the river, as I was supposed to have trained in the river. The ancestor's voice talked to me and instructed me not to go out of the ibhuma that night. In the evening, two crabs came inside, moved along the walls, and then left. These, I was told, are also izilozekhaya. On Sunday morning, Sandile, Mamjwarha, and other amaqrhira came to fetch me. Sandile brought umqombothi in a new billy can, intsimbiemhlophe, brandy, gin, "Horseshoe" tobacco, matches and "XXX" mints.

Mamjwarha gave instructions on what was to be done and when. All the above items were put in the river so they floated on the water. One of the Abantu-Bomlambo appeared from the water, took them and disappeared into the river with them. We gave the praise greeting, "Camagu". Swallows were flying over our heads in large numbers, like a swarm of bees. These are also regarded as izilozekhaya. Then the ibhuma was destroyed and we left for the house. I was transported by car, as I was unable to walk. When we arrived home, a white goat was slaughtered, because I dreamt that a white goat without a spot was to be slaughtered by Sandile, my cousin. He was not supposed to wear black trousers when he did that, as this would bring darkness and bad luck to me. Food was cooked and people ate. People first drank umqombothi and afterwards brandy and gin. Then there was the intlombe graduation ceremony at which I became a healer, with beating of drums, singing and dancing to celebrate. After the ceremony, I was able to walk normally again.

One night I dreamt of Intsimbiemhlophe that I was supposed to buy and wear. It was bigger than the normal one, and I was told to get it from Diagonal Street in Gauteng as it was not available in the Eastern Cape. I went there but I found that it was out of stock. The ordinary intsimbi broke when I wore it, and it felt very heavy on me. I then dreamt of an animal skin to wear as the beads were not available. I described it to the herbalist, who identified it. I do not know the name of that animal, but I am still wearing that skin on my wrists. When I get headaches, I burn a piece from the skin and inhale the smoke.

When divining, I just look at the patients' eyes, then my left hand itches, and when I look at the hand something will be written that can only be read by myself and not anyone else. Then I tell the patient what his or her problem is, and where it emanates from. When a ritual has to be performed by a patient, I am able to tell him or her. I healed people who were sick, but I specialized in helping women who had difficult or delayed labour due to witchcraft.

After I became an igqirha, I noticed some changes in my life. People avoided being with me. They avoided eye contact. Others stopped greeting me. Others laughed at me for becoming a healer. I decided to stay at home. I lost my friends because I told them when they were having harmful muti. I still had intuitions like before; when an evil person was coming to my house I could still feel it, and would ask my children to close my bedroom door and tell the person that I was asleep. My ancestors were, and are, still talking to me through amathongo and visions, telling me when people are practising witchcraft or when to perform certain rituals. People started to be jealous of me. They would ask for things like sugar, tea, bread and money from me. My ancestors told me through a dream that they were bewitching these items, so I stopped giving them. When I come into contact with a bad witch, I still get palpitations and anxiety.

In 2001, we were going to attend a sports meeting at school. My ancestors warned me in a dream not to go there, but I did not listen, because I was a sports coordinator and was supposed to attend the meeting. When I arrived, I fell down and fractured my leg, and sprained an ankle. I was admitted to hospital, but I am still unable to walk even now. I cannot cure myself; all traditional healers cannot cure themselves. They are cured by other healers. Since I came back from hospital, my ancestors asked me to stop working with people, until I recuperate. I am waiting for them to tell me when to resume my work again. Witchcraft is here to stay. It was here before we were born and it will continue to exist on earth.

Concluding Comments

Nomzi's narrative is largely based on her own account. Her cousin Sandile did confirm several aspects of it. As mentioned, he had been present at the final initiation ceremony which led to her graduating as an iqqirha. He also mentioned that she had intuitions and used to dream a lot, and was the one who mentioned the incident of a garden spade (which Nomzi later confirmed). The narrative has several features which render it quite problematic from a phenomenological perspective. Firstly, it is very descriptive. Nomzi's account is prereflective, and presented in a manner that assumes that the listener will understand the significance of what she is saying. For those unfamiliar with traditional Xhosa life, customs and beliefs, much of what she describes will seem opaque and mysterious. Events are described in a manner that is quite bare. This is not "thick description". There is little or no information about her feelings about the various incidents. Indeed, a phenomenologically oriented researcher might question whether such an account can be considered phenomenological at all. Secondly, the story stops abruptly in 1969 when she was 32, and only resumes in 1998 when she was 61. During these three decades, she had three children, although she never married. This suggests that the story had been constructed, albeit unwittingly, by Nomzi and presented as a fait accompli, already framed by Nomzi as a healer's story, the story of her life given meaning through her journey to become an igqirha.

It is nevertheless her account of her experiences and is full of rich information about her life. But this richness can only be accessed through interpretative frames of reference. As suggested above in the section on methodology, we propose that each of three discourses can serve to deepen our access to Nomzi's experience and the complex and troubled story of her life. These three discourses are those of: (1) the Xhosa tradition itself, with its understanding of how the abahlekazi call the initiate to the intwaso process and how the process unfolds, (2) clinical psychological assessment, and (3) transpersonal psychology and its understanding of shamanism and shamanic initiation. This will be the focus of the next paper (Edwards, Hirst, & Booi, 2014). Two years after this research was first written up as a thesis (Booi, 2004), Nomzi died at the age of 69. So, in the next paper, the reader is invited to reflect back on a life story that has been lived in a cultural context and world that is already receding into history, and to see how a hermeneutic approach can help read between the lines of Nomzi's intriguing narrative.

Referencing Format

Booi, B. N., & Edwards, D. J. A. (2014). Becoming a Xhosa healer: Nomzi's story. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 14(2), 12 pp. doi: 10.2989/IPJP.2014.14.2.3.1242

Acknowledgements

1. The authors would like to thank "Nomzi Hlathi" for her willingness to share her story in such detail, as well as "Sandile" for willingly providing collateral information.

2. This research was supported by grants to the second author from the Research Committee at Rhodes University and the National Research Foundation.

References

Barker, C., Pistrang, N., & Elliott, R. (2002). Research methods in clinical psychology: An introduction for students and practitioners. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Blatt, S. J., & Levy, K. N. (2003). Attachment theory, psychoanalysis, personality development, and psycho-pathology. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 23(1), 102-150. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07351692309349028 [ Links ]

Booi, B. N. (2004). Three perspectives on ukuthwasa: The view from traditional beliefs, Western psychiatry and transpersonal psychology (Unpublished master's thesis). Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa. Available at http://eprints.ru.ac.za_175_1_booi-ma [ Links ]

Bromley, D. B. (1986). The case study method in psychology and related disciplines. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Brooke, R. (1991). Hermeneutic keys to the therapeutic moment: A Jungian phenomenological perspective. In R. van Vuuren (Ed.), Dialogue beyond polemics (pp. 83-94). Pretoria, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

Buhrmann, M. V. (1986). Living in two worlds: Communication between a white healer and her black counterparts. Wilmette, IL: Chiron. [ Links ]

Dark energy, dark matter. (April 30, 2013). Retrieved January 03, 2014, from http://science.nasa.gov/astrophysics/focus-areas/what-is-dark-energy/ [ Links ]

Doore, G. (Ed.). (1988). Shaman's path: Healing, personal growth and empowerment. Boston, MA: Shambhala. [ Links ]

Edwards, D. J. A. (1998). Types of case study work: A conceptual framework for case-based research. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 38(3), 36-70. [ Links ]

Edwards, D. J. A., Hirst, M., & Booi, B. N. (2014). Interpretative reflections on Nomzi's story. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 14(2), 13pp. doi: 10.2989/IPJP.2014.14.2.4.1243 [ Links ]

Edwards, D. J. A., & Young, C. (2013). Assessment in routine clinical and counselling settings. In S. Laher & K. Cockroft (Eds.), Psychological assessment in South Africa: Research and applications (pp. 320-335). Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Goswami, U. (Ed.). (2014). The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of childhood cognitive development (2nd ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Grof, S., & Grof, C. (Eds.). (1989). Spiritual emergency: When personal transformation becomes a crisis. Los Angeles, CA: J. P. Tarcher. [ Links ]

Hirst, M. (1997). A river of metaphors: Interpreting the Xhosa diviner's myth. In P. McAllister (Ed.), Culture and the commonplace: Anthropological essays in honour of David Hammond-Tooke (pp. 217-250). Johannesburg, South Africa: Witwatersrand University Press. [ Links ]

Hirst, M. (2005). Dreams and medicines: The perspective of Xhosa diviners and novices in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 5(2), 1-22. [ Links ]

Krippner, S. (2000). The epistemology and technologies of shamanic states of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7(11-12), 93-118. [ Links ]

Kruger, D. (1988). An introduction to phenomenological psychology (2nd ed.). Cape Town, South Africa: Juta. [ Links ]

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (1989). Designing qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Pearlman, L. A., & Courtois, C. A. (2005). Clinical applications of the attachment framework: Relational treatment of complex trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 449-459. [ Links ]

Richardson, J. T. E. (Ed.). (1996). Handbook of qualitative research methods for psychology and the social sciences. Leicester, UK: British Psychological Society. [ Links ]

Robson, C. (2002). Real world research: A resource for social scientists and practitioner-researchers (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Singer, J. (1990). Seeing through the visible world: Jung, gnosis and chaos. San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Sroufe, L. A. (2005). Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment and Human Development, 7(4), 349-367. doi:10.1080/14616730500365928 [ Links ]

Stafford, P. (1992). Psychedelics encyclopedia: Third expanded edition. Berkeley, CA: Ronin. [ Links ]

Stones, C. R. (1988). Research: Toward a phenomenological praxis. In D. Kruger, An introduction to phenomenological psychology (2nd ed.) (pp. 141-156). Cape Town, South Africa: Juta. [ Links ]

Taylor, S. J., & Bogdan, R. (1998). Introduction to qualitative research methods: A guidebook and resource. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Valle, R. S. (1989). The emergence of transpersonal psychology. In R. S. Valle & S. Halling (Eds.), Existential-phenomenological perspectives in psychology: Exploring the breadth of human experience (pp. 257-268). New York, NY: Plenum. [ Links ]

Walsh, R. (1990). The spirit of shamanism. Los Angeles, CA: J. P. Tarcher. [ Links ]

Walsh, R., & Vaughan, F. (Eds.). (1993). Paths beyond ego: The transpersonal vision. Los Angeles, CA: J. P. Tarcher/ Perigee. [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

About the Authors

Beauty Booi is a Clinical Psychologist at Komani Hospital in Queenstown, South Africa, where her work with in-patients and out-patients includes psychotherapy for a range of problems, a trauma counselling service for women who have been raped, and assessments for disability grants and forensic cases. She also conducts a private practice.

Trained initially as a professional nurse, Beauty Booi qualified as a psychiatric nurse before completing a Psychology Honours degree through the University of South Africa (UNISA) and later her Master's degree in Clinical Psychology at Rhodes University in Grahamstown in 2005. The focus of her Master's thesis (Booi, 2004) reflects her longstanding interest in Xhosa traditional healing. E-mail address: booi_b@telkomsa.net

David Edwards has been a Clinical Psychologist and practising therapist for over thirty years. He is a founding fellow of the Academy of Cognitive Therapy, having trained in the mid-1980s at Beck's Centre for Cognitive Therapy in Philadelphia, where he attended seminars with Jeffrey Young, the developer of schema therapy. In addition to an enduring interest in psychotherapy integration and experiential training in a variety of humanistic and transpersonal approaches, he is certified as a schema therapist and schema therapy trainer with the International Society of Schema Therapy (ISST). Until his recent retirement as a Professor of Psychology at Rhodes University, he provided professional training and supervision in cognitive therapy for two decades.

Over a long career, Professor Edwards has published some 70 academic articles and book chapters, several of which focus on the use of imagery methods in psychotherapy. He has had a longstanding interest in transpersonal psychology and the shamanistic perspective on psychotherapy, and has done experiential training in this area with Stanislav Grof. Professor Edwards is first author of Conscious and Unconscious, in the series "Core Concepts in Psychotherapy" (McGraw Hill), a book that includes chapters on cognitive therapy and transpersonal psychology. His research for this book gave rise to two papers published in this journal in 2003 and 2005.

For more information about him and the training he offers, visit www.schematherapysouthafrica.co.za. E-mail address: d.edwards@ru.ac.za