Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology

versión On-line ISSN 1445-7377

versión impresa ISSN 2079-7222

Indo-Pac. j. phenomenol. (Online) vol.13 spe Grahamstown sep. 2013

With the lifeworld as ground. A research approach for empirical research in education - the Gothenburg tradition

Jan Bengtsson

ABSTRACT

This article is intended as a brief introduction to the lifeworld approach to empirical research in education. One decisive feature of this approach is the inclusion of an explicit discussion of its ontological assumptions in the research design. This does not yet belong to the routines of empirical research in education. Some methodological consequences of taking the lifeworld ontology as a ground for empirical research are discussed as well as the importance of creativity in the choice of method for particular projects. In this way, the lifeworld approach has its own particular perspective in phenomenological, empirical research in education. The article concludes with a description of an empirical study based on the lifeworld approach in order to illuminate the possibilities for empirical research in education as well as the significance of this approach for education.

Introduction

The existence of phenomenology as a movement has been acknowledge since Herbert Spiegelberg's (1960) publication of his extensive study of phenomeno-logical philosophy. This study was enlarged in cooperation with Karl Schuhmann in 1982 (Spiegelberg & Schuhmann, 1982). This movement can be divided into at least five different directions (Bengtsson, 1991). The first three are strongly connected to Husserl's original development of phenomenology. Phenomenology's origins go back to the Austrian school, founded by Franz Brentano. It is within this school that Husserl found a platform for his phenomenology. This first direction could be characterized as a pre-phenomenological period. The second direction starts with Husserl's break with the Austrian school and his criticism of psychologism (Husserl, 1980a). During this period, Husserl developed his first understanding of phenomenology as descriptive phenomenology. However, by 1907 (Husserl, 1950) Husserl was already on his way to a new phenomenological direction, which he would term transcendental phenomenology, introduced as pure phenomenology (Husserl, 1976). The other two directions are phenomenology of existence and phenomenological hermeneutics. Both of these directions originated in Heidegger's (1927) early philosophy and have been continued by other leading phenomenologists such as Sartre, de Beauvoir and Merleau-Ponty in the phenomenology of existence, and by Gadamer and Ricœur, in phenomenological hermeneutics.

From this simple description of the phenomenological movement it is possible to conclude that phenomenology is not one single thing and therefore does not exist in a singular definite form. It is thus important to always be explicit about what direction within the phenomenological movement is used in any phenomenological investigation. It is equally important to realize that the phenomenological movement involves different directions because these directions are not identical. These ifferences sometimes include contrasting knowledge claims and in these cases the directions are not always compatible. Notions and methods can therefore not be mixed freely between the phenomenological directions.

The research approach introduced in this Special Edition is based on lifeworld phenomenology (Bengtsson, 1984; 1986; 1988a). This approach uses resources from lifeworld phenomenology. Books and articles about phenomenology frequently assert that Husserl introduced both the word and the notion of the lifeworld in his late work, which was published posthumously in the book Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie [The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology] (Husserl, 1954). This assertion is, however, incorrect (Bengtsson, 1984). Husserl's use of the word lifeworld can at least be traced back to the years 1916-17 when he wrote a manuscript entitled Lebenswelt - Wissenschaft -Philosophie: Naives hinleben in der Welt -Symbolisches festlegen durch Urteile der Welt -Begründung [Lifeworld - science - philosophy: naïve living in the world - symbolic fixation through judgments about the world - founding]. This manuscript predates the publication of his article Die Krisis der europäschen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie [The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology] in 1936 (Husserl, 1936) by 20 years. In fact, Husserl's notion of the lifeworld was introduced even earlier than this date, but he referred to it using other terms, such as "the world of the natural attitude" (Husserl, 1976, p. 56).

The above discussion serves to illustrate two points about the lifeworld. Firstly, the notion of the lifeworld was introduced in Husserl's transcendental phenomenology, but was not part of pure phenomenology. The lifeworld thus belongs to mundane phenomenology. It is pre-transcendental and not transcendental; it precedes and is presupposed by transcendental phenomenology in its efforts to demonstrate the pure constitution of the lifeworld. However, if the transcendental argument is conclusive, transcendental phenomenology cannot presuppose the lifeworld completely. Transcendental phenomenology has to go beyond the lifeworld in order to be pure and cannot accept that the lifeworld is also presupposed in the reflection and explication of the lifeworld. However, the lifeworld phenomenology used in the lifeworld approach contained in this Special Edition is consequent in affirming the presupposition of the lifeworld on all levels. There is no way to escape the lifeworld. Thus, lifeworld phenomenology is differentiated from the knowledge claims of transcendental phenomenology.

Secondly, the notion of the lifeworld is not identical with the term 'lifeworld'. As already noted, Husserl used several terms to describe the concept of the lifeworld. This is also true of other scholars in the phenomenological movement. Heidegger (1927) used the term 'being-in-the-world' (in-der-Welt-sein), Merleau-Ponty (1945) 'being-to-the-world' (être-au-monde), and Schutz (1962) 'world of daily life'. Each of these scholars added their particular accent to the understanding of the lifeworld. Among other things, Heidegger stressed the practical and historical dimension of the lifeworld, Merleau-Ponty its embodiness and Schutz its social dimensions. Together, these scholars provide a differentiated understanding of the lifeworld containing a large number of partial theories and concepts. This constitutes the core of the resources of the lifeworld approach.

The understanding outlined above highlights the double function of the lifeworld. This is expressed in the title of this article: "with the lifeworld as ground". On the one hand, the lifeworld is a factual ground that cannot be overcome through philosophical reflection or scientific research (the philosopher and the researcher are always already in the world), and on the other hand, the lifeworld is a theoretical ground for empirical research (the theoretical resources for research).

The theories and concepts of lifeworld phenomenology are, however, not directly available for use in empirical research. With the exception of Schutz none of the lifeworld phenomenologists mentioned above were interested in using lifeworld phenomenology in empirical research or in showing how an empirical research approach could be based on their theories. Their projects were strictly philosophical and they used the theory of the lifeworld to answer philosophical questions. This also applies to Merleau-Ponty, despite the fact that he introduced empirical results from psychology and medicine into his discussions. Schutz (1932, 1962) tried to make the notion of the lifeworld useful to the social sciences. However, he avoided taking a stance regarding transcendental phenomenology's claim of reducing the lifeworld to pure consciousness (Bengtsson, 2002) and he combined lifeworld phenomenology with a methodology based on neo-Kantian hermeneutics based on Max Weber. The inconsistency between lifeworld phenomenology and phenomenological hermeneutics, on the one hand, and neo-Kantian hermeneutics, on the other hand, will be discussed later in this paper.

The empirical research approach discussed in this Special Edition aims to make the transition from philosophical to empirical research explicit. It also aims to offer a research approach that is consequently and coherently based on lifeworld phenomenology.

Philosophy of science of the lifeworld approach

I believe that the ground of empirical research can be formulated in the following manner. All empirical research tries to establish knowledge about some delimited part of reality. In doing this, assumptions are made, often unconsciously, about this reality. Assumptions are also made about how it is possible to acquire knowledge about this reality. Theories about those kinds of assumptions belong to two different branches of philosophy, namely ontology and epistemology respectively.

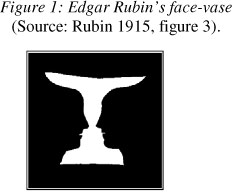

Ontological and epistemological assumptions constitute the philosophical ground of empirical research in the sense that they are presupposed in all empirical research. The ground, however, does not need to be understood in an absolute sense. In the following section I will limit the discussion to ontological assumptions, not because epistemological assumptions are less important, but because the space of an article is not enough to discuss both assumptions. I have chosen to focus on ontological assumptions because they are less noticed (Bengtsson, 1988b, 1991). Ontological assumptions could be described as the medium through which research is conducted. From a different perspective they could be described as the invisible that makes the visible appear. I think, however, that the gestalt figure of the face-vase, introduced by the Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin (1915), adds a new dimension to understanding the relationship between philosophical assumptions and empirical research.

Within this figure, or figures, there is interdependence between figure and background. If the vase is figure, it is so only because the surrounding background is seen in a particular way. However, this can change radically. The figure suddenly switches and the vase becomes the background and the earlier background appears as two faces looking towards each other. Thus, if the background is changed a new figure appears. If this principle is applied to empirical research, it could be said that the empirical reality that is open for study depends on the ontological assumptions that are made. When the assumptions are changed a different reality appears.

In other words, empirical research is not free of philosophical assumptions. These assumptions are different in different research traditions, but they are always presupposed. In some traditions, such as philosophical positivism, they are even denied, but this is, of course, also a theory, although of a particular kind. In other traditions, the assumptions are not denied, but they are also not made explicit. Instead, they function implicitly in the research. Such a tradition could be called naïve positivism. Some assumptions are always presupposed in empirical research and these assumptions need to be made as explicit as possible; otherwise it is not possible for the researcher to take a position regarding these assumptions. The assumptions should also be made explicit to other researchers in order to facilitate examination and discussion about them. If the presuppositions of research are not open to examination, the research's contribution to scientific knowledge could be brought into question. In order to avoid this questioning the methods used in a particular study are always presented in empirical research reports. The ontological presuppositions for the choice of method should also be explicated in order to determine the research's contribution. However, these ontological presuppositions might not always be completely and finally explicated. Later in this article I will return to a discussion of the methodological consequences of ontology.

Ontological options

Against this background the question arises of what ontological options are available. Ontology has existed for as long as philosophy, which has existed for at least 2500 years. It is, of course, impossible to provide even an outline of this history. The task therefore has to be limited in a way that is relevant to its purpose. I have decided on the following strategy. To start with, the task can be limited to the history of Western philosophy and further limited to its history since the Renaissance. It is during this period that empirical research originated and corresponding ontological theories were introduced. Contemporary empirical research is still to a large extent based on theories from this founding period (Bengtsson, 2013). The task can further be limited to some of the classical theories developed since the Renaissance in order to compare some of their essential assumptions and consequences for educational research with the lifeworld ontology.

One of the most influential ontological theories was the dualism of Descartes (Descartes, 1975).1 According to this ontology, everything that exists can be understood with the help of two different kinds of qualities: material and mental. There is no relationship between these two kinds of qualities. They coexist but are incompatible with each other. This has been the crucial problem of dualism since its beginning. I will illustrate the problem through the use of an example. In the morning, when I am slicing fruit, I suddenly cut my finger. The finger has a wound, it bleeds and it hurts. Dualism can offer a way of analysing this example. The wound in my finger is physical and so is the blood. The wound and the blood are of the same kind and stand in a causal relationship to each other. The wound in the skin is the cause of the blood streaming out of the finger. The pain, however, is of a totally different kind and has nothing to do with material qualities. Dualism is therefore able to understand material as well as mental qualities, but they are divided in two separate realms that never meet. It thus remains a mystery what the pain has to do with the wound and the blood and vice-versa.

Historically, two forms of monism have played the role of ontological theories competing with dualism. According to these theories, a single quality is enough to understand all that exists. These two forms of monism are usually referred to as materialism and idealism. Idealism argues that the only quality that is needed in order to understand reality is mental qualities of different kinds such as mental states, cognitions or ideas. Materialism turns this ontology upside down, so to speak, and argues that all that exists are material qualities of different kinds and in different constellations. Both forms of monism overcome one of the basic problems of dualism, in that they are able to explain the relationship between material and mental qualities. This problem simply disappears in monism. If only one kind of quality exists, there cannot be any problem in understanding the relationship between different kinds of qualities. However, a new question arises: Is it really possible to understand everything that exists with only one kind of quality? According to both forms of monism, everything can be reduced to only one kind of quality. Materialism reduces mental qualities to material qualities, arguing that all mental qualities can be understood as material qualities. Idealism uses the same strategy, but argues for the inverse reduction, namely that all material qualities can be reduced to different kinds of mental qualities.

Materialism was the ontological foundation of psychology and educational research when they were established as scientific disciplines in the later part of the 19th century. Wilhelm Wundt is often considered to be the father of this scientific endeavour (Wundt, 1873). He started the first psychological laboratory, as it was called, in 1879 in Leipzig, Germany. This was soon followed by psychological laboratories all over Europe and the USA. The inspiration for this psychology was the natural sciences (as can be seen in the choice of name and its technical use). In the psychological laboratories experiments were conducted in order to measure mental activities by way of physiological changes in the physical body. Wilhelm Wundt was also educated in medicine. This knowledge was transferred to educational research, which was understood as the application of psychological knowledge to educational problems (Bengtsson, 2006b).

A second major direction in psychology and educational research based on a materialistic ontology is behaviourism. Watson provided behaviourism with its first influential formulation at the beginning of the 20th century (Watson, 1919), and scholars like Skinner refined the research direction (Skinner, 1971). This form of materialism differs considerably from the former physiological approach. In behaviourism, patterns of behaviour are studied in the form of the organism's reaction to causal stimuli in the physical environment. While the physiological approach focused on inner processes in the organism, behaviourism observed outer physical behaviour.

There are also different forms of idealism in the history of psychology and educational research. Piaget's individual constructivism is an example of an approach that is clearly idealistic in its research approach. This is a neo-Kantian approach that assumes that children construct their reality cognitively. It is therefore the task of empirical research to find out what cognitions children need in order to understand reality. Consequently, during numerous equilibrative thought experiments of learning, Piaget exposed children to dilemmas that are supposed to be handled by purely logical means and integrated into a final equilibration of a logical and total system (see for instance Piaget, 1937; 1946; critical discussions by Merleau-Ponty, 2001; Hundeide, 1977).

Different forms of social constructivism also have idealistic tendencies. Although the social and communicative aspects of the constructions are always stressed, the constitutive role of the human body is mostly neglected (Lave & Wegner, 1991; Wertsch, 1991, 1998). There is sometimes a very strong focus on linguistic meaning, arguing that no meaning exists outside texts, narratives or language in general. Language in its different forms is supposed to constitute a self-sufficient, although not stable, meaning system (Potter & Wetherell, 1987).

The possibility of monism replacing dualism depends on its power to convince researchers of the reduction of reality to one of two different kinds of qualities. Methodological consequences of the two forms of monism seem to be that materialism prefers methods like experiment and observation, while idealism prefers methods like interviews and intellectual tasks. This methodological choice came to the fore in the 1980s when qualitative approaches were introduced in educational research. The credo of the qualitative movement at that time was often expressed in the rhetorical question, "If you want to know something about other people, why don't you ask them?" (Kvale, 1996, p. 1). This question was addressed to educational researchers who used behaviouristic methods such as observation and it presupposed that these methods could and should be replaced by interviews.

Lifeworld ontology

Lifeworld ontology represents a different understanding of reality. If it were not for phenomen-ology's continuing criticism of all kinds of -isms since its very beginning2, the lifeworld ontology could have continued the tradition of constructing names with the suffix -ism and used the name pluralism. In this context, pluralism means that reality is conceived of as complex, consisting of a large number of different qualities that cannot be reduced to each other. In this sense it is, of course, harmless to use the word pluralism as a synonym for the lifeworld ontology, because it means reduction to complexity, which is the opposition of traditional reductionism.

In order to make the assertion of the complexity of reality credible, it is necessary to show this by way of some simple, but hopefully convincing, examples. In our everyday life, tools of different kinds surround us. Heidegger (1972) calls them Zeuge and they can be exemplified by items such as pen, paper, books, tables, clothes, shoes, glasses, and cell phones. Tools all have a particular quality in common that cannot be reduced to either physical or mental qualities. This quality could perhaps be referred to as 'utility quality' and it is experienced as the possibility of use. The cell phone, for instance, is made of several material qualities, mainly plastic and metal, but it also has a utility quality that cannot be reduced to material qualities. Despite this, the quality is an experienced quality of this material thing; to be precise it is experienced as the possibility of calling people with the cell phone. If we could not experience this quality, the item could not be used as a cell phone and then we would question whether it was actually a cell phone. It should also be obvs not a mentalious that the utility quality i quality; it is a quality of this particular material thing, not something that we can find in inner life. The utility quality of the cell phone should also not be confused with the technical function of the cell phone. We do not need any technical knowledge about the cell phone, we do not need to understand what makes it work, in order to experience it as a cell phone and know how to use it as a cell phone.

In preschools, children might find things like swings, seesaws, balls and other objects to play with. Such things are not neutral for the children. They have a very particular quality, which could best be described by words such as requiredness or appeal (Langeveld, 1984). The ball is there to be kicked, the swing requires swinging on, and the seesaw includes a social dimension in its appeal by requiring two children to use it together. This kind of requiredness can also be found in the exteriority as well as in the interiority of buildings and in places (Bengtsson, 2011). Libraries demand silence, churches a respect for the sacred, and a bump on the road not only requires us to slow down but also has built-in consequences if not obeyed.

All tools and toys (actually, all things of all kinds) only exist together with other things. In the lifeworld there are, strictly speaking, no single things. Every object that we experience or handle is surrounded by other objects, and every object refers in its turn to further objects outside the present surroundings. However, all objects in the present surrounding and in the lifeworld are not of equal significance. Depending on the person's activities, certain objects are singled out and they include references to appresented or co-experienced other objects inside and outside the present surrounding.3 However, the person's field of activity does not only consist of different things, but also includes references to other persons with whom he or she interacts, has interacted or will interact. In this way, things, persons and activities constitute a regional world that is not limited to what is present, but includes other things, persons and activities that are possible to experience, interact with and perform within this world. Each regional world also constitutes its own particular history. The lifeworld is everything that is possible to experience and do for a particular individual, and the lifeworld consists of different regional worlds in which the individual lives, for instance the family, the working place and recreational activities with friends (Bengtsson, 1999, 2006a, 2010).

A second major characteristic of lifeworld ontology is the intertwinement or the interdependence of life and world (Bengtsson, 1988a). This point rejects dualistic ontology. The concept of the lifeworld is very peculiar and could perhaps be explained as a kind of in-betweenness. In other words, the lifeworld is neither an objective world in itself, nor a subjective world, but something in between. Ambiguity is a necessary feature of intertwinement. World and life are interdependent in the sense that life is always worldly and the world is always what it is for a living being. Thus, the world is open and uncompleted to the same extent as life. Life and world have identity, but it is not permanent or objective or universal. In this way, life and world are always already a unity that can be separated only afterwards (Heidegger, 1927; Husserl, 1954; Merleau-Ponty, 1945). It is therefore mistake to present a choice between life and world, despite the fact that we have learnt to do this in the Western history of ontology.

We have to learn to see reality more in terms of both-and instead of either-or. This applies not only to life and world, but also dualities such as body and mind, object and subject, outer and inner, physical and mental, sensuous and cognitive, reason and emotion, self and other, and individual and society. I will use an example from the previous discussion of the dualistic understanding of the relationship between body and mind to illustrate this point. In lifeworld ontology, body and mind are mutually dependent on each other. The mind is embodied and the body is animated. I call the unity of body and mind 'lived body' to separate it from the physical body as well as from the inner experienced body and to indicate an originally combined and integrated position. The lived body is both physical and mental, object and subject, integrated in 'my own body (le corps propre), to use Merleau-Ponty's (1945) expression.

In relation to the previous example of slicing fruit, lifeworld ontology will permit a different analysis of the relation between the wound, the blood and the pain. When I cut my finger, this is not the same as slicing fruit. The cut in my finger hurts. The same is also true the other way around, the pain is not a disembodied mental state, but perfectly integrated with my body in the sense that I know exactly where the pain is; it is in my wounded index finger, not in the foot, not in the head, and not in the middle finger. Body and mind are integrated in the lived body.

The implications of the lived body can easily be extended. According to this ontological theory, the lived body is present in whatever we do and experience. We cannot leave it behind us, as we can with a bicycle, and pick it up later. It is always with us. Instead of saying that I have a body, it could be said that I am my body. Thus, the lived body is the subject of everything that we do and experience. In this way, the lived body is our access to the world. If something happens to our body, the world changes correspondingly. When we have a headache, the world is not accessible in the same way as it usually is, and if we lose our sight or an arm, the world changes in several respects. It is also possible to integrate physical things with the lived body. One common example is the blind man's stick (Merleau-Ponty, 1945). The stick is a thing among other things in the world, but when the blind person has learned to use the stick, it is no longer experienced as a thing but becomes an extension of the lived body through which the world is experienced. In a similar way, other things such as bicycles and cars can be integrated with the lived body and extend experiences and actions of the lived body.

It should also be noted that the central notion of phenomenon has an intertwined character. The word 'phenomenon' has Greek origins and means 'that which appears'. Phenomenology uses the word in the same way and in no other way. A characteristic of a phenomenon in this sense is its intertwinement between object and subject. One of the conditions for something to appear is that there must be someone for whom it appears. In the history of Western ontology and epistemology, a second reality, more real than the world of phenomena and a condition for the latter, has often been assumed. Kant's 'thing in itself' is one famous example (Kant, 1976). However, this raises questions as to how we can ever know anything about this second reality. It also brings into question our reasons for assuming its existence. The only reality we know anything about is the world in which we live and which appears to us in one way or another, that is, the lifeworld. Husserl (1954) wrote about the assumption of a reality behind the reality that appears to us as a doubling of reality. Heidegger (1973) objected to Kant's ideas and held that "[t]he 'scandal of philosophy' is not that this proof has yet to be given [that is, a proof of the existence of things in themselves behind our experiences], but that such proofs are expected and attempted again and again" (p. 249).

Regional ontology

Although ontological assumptions are presupposed in all empirical research, this does not imply that empirical research has to develop a general ontology as this falls within the realm of philosophy. Empirical research does not need a general ontological theory that includes everything that exists. Instead, it is enough to have an ontology delimited to a particular part of reality, in our case to educational reality. However, it is necessary to have such a theory and this theory needs to be made explicit within empirical research. Within the lifeworld approach, this delimited kind of ontology is referred to as regional ontology (Bengtsson, 1988b, 1991, 2005). It is important to note that this notion of regional ontology should not be confused with Husserl's (1952) idea of regional ontology, although it is inspired by this idea. Husserl divides everything that exists into three regions or realms of existence, that is, material nature, animal nature and spiritual (geistige) worlds. This is an understanding of reality in the sense of a general ontology.

My own understanding of regional ontology can now be further specified. It is not enough to delimit regional ontology to educational reality in general. It also has to be limited to the particular reality that is in focus in particular projects of educational research. In other words, regional ontology must be limited to that part of reality that the research question has singled out in its formulation. This view corresponds with the starting point in the section above concerning the philosophy of science of the lifeworld approach. It suggests that all empirical research is trying to establish knowledge about some delimited part of reality. The intention of these delimitations is to adapt ontology to empirical research. Ontology is, therefore, not approached for its own sake. Instead, it should be understood as an instrument for doing empirical research and is not developed further than is necessary for this purpose. It is on this point that I diverge from Husserl's idea of a regional ontology (as well as from Heidegger's and Merleau-Ponty's ontologies). Husserl was never interested in elaborating ontology for the sake of doing empirical research. His interest was purely philosophical. My notion of regional ontology is in this respect closer to Schutz's (1932, 1962) intentions with his development of a theory of the social world as the foundation of the social sciences. However, Schutz (1932, 1962) did not use the term regional ontology. If Schutz's (1932, 1962) theory could be called a regional ontology, it is a regional ontology of the discipline of the social sciences rather than a regional ontology in the proper sense of the term.

The question of what the regional ontology of the lifeworld approach is still remains to be answered. This question has to be answered in several steps. Firstly, the lifeworld ontology offers a general perspective on how to perceive and encounter the reality of an empirical study. Through lifeworld ontology, reality appears in a particular way.

Secondly, the lifeworld ontology offers a number of concepts and theories about the lifeworld. These concepts and theories together constitute the theoretical resources of the lifeworld approach. They are not all relevant in all empirical studies. A selection has to be made in accordance with the research question. This point seems to not have been observed in Peter Ashworth's (2003) empirical research approach based on the lifeworld. In a Special Issue about this approach in the Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, he lists seven universal categories. He himself calls them "fragments" to indicate that they "together do not yet constitute a full account of the essence of the lifeworld" (Ashworth, 2003, p. 147), but insists that they should nevertheless enable "the detailed description of a given lifeworld" (Ashworth, 2003, p. 147). The used categories are selfhood, sociality, embodiment, temporality, spatiality, project and discourse. I question whether the same categories could be used in different studies irrespective of the research question. To my understanding of phenomenology, it also sounds strange use a limited number of categories to understand the lifeworld, regardless of whether there are more than seven categories. To me, this seems to be a variation of Kant's formalism. Husserl stated that phenomenology was a task for generations of phenomenologists. Van Deurzen (1997) has extended the number of categories to 4 x 19 categories in order to describe human existence, and I am not convinced that this is exhaustive. It gives the impression of being a taxonomy, which is inconsistent with the lifeworld approach. The lifeworld approach is an explorative approach whereas taxonomies normally have a deductive purpose.

Thirdly, the concepts and theories about the lifeworld have to be adapted to the particular research question. Their purpose is to enable the researcher to identify and understand phenomena in a lifeworld sensitive way. The more general they are, the less useful they are in explorative research. Intentionality, for example, can be a useful concept in many studies, but it is not exactly the same in allocating marks as in discussing marks, in social relations between teachers and students, in teachers' working pleasure, in preschool children's outdoor activities in nature or in teachers' use of self-knowledge in their professional life. When we want to research new worlds, we need to know in order to find, but we also need to find in order to know. We need a pre-understanding of the other world, but this is never the same as already understanding it in advance. Research has to live with this ambiguity.

Some methodological consequences

Lifeworld ontology has very definite consequences for methodology. I will discuss some of these consequences for methods of collection such as observation and interview as well as methods of interpretation of the collected material.

Lifeworld ontology gives us the opportunity to observe and understand reality in a particular way. We are therefore able to access the study of different educational settings. The world is full of things and qualities that are neither objective nor subjective (such as tools and their utility qualities) and these things and qualities constitute regional worlds of people using them in particular ways. Thus, education takes place in a world of things, activities and interactions. The participating persons need to have a practical understanding of these things, activities and interactions. If we want to understand educational situations, we have to understand them in their lived and worldly context as this is where they have their meaning.

However, the individuals are not only social and worldly agents. They are also embodied subjects. Against this background it is possible to use observations in a new sense. For instance, if we observe other people in action, the content of the observation is not limited to material qualities. The people we see have lived bodies that consist of neither purely physical behaviour nor purely interior mental life. Mental life is expressed in the body, and bodily movements are mental. Body and mind constitute an undivided unity in which the body is subject and the mind is embodied. In this way, the behaviour of a person allows us to understand something about his/her life; the behaviour has a particular meaning that is available to us. This meaning, however, is not hidden behind the behaviour in the subjective intentions of the agent as is believed by the neo-Kantian tradition of hermeneutics.4 Instead, the meaning is experienced in the bodily movements of the other person and, together with the meanings of a specific surrounding of particular things and other people, it constitutes a particular world of meaning. For example, the teacher can see that a child might be in need of some help with his/her arithmetic, that another child is uninterested in his/her work today, and that a third child seeks contact with another child. As an observer, the researcher can see what the teacher sees and does, as well as what the children see and do. This does not mean that other people are easy to read. However, the possibility of observing the meaningful behaviour of another person can be used as a starting point for new and extended observations that form part of an interpretation process that takes into consideration previous and present as well as following events. Observations are not limited to meaningful behaviour. Speech activities might also be included. This is the lived language that people spontaneously use in their practice in distinction to the language they use when they reflect upon their practice in an interview. Observations in this sense have been used in several empirical studies in the lifeworld approach (Ferm, 2004; Friberg, 2001; Greve, 2007; Johansson, 1999, 2007; Løkken, 2000, 2004).

The agents might sometimes not even be able themselves to tell about such things as their intentions, feelings, thoughts and perceptions of their actions (Dahlberg, 2006). If the teacher is understood as an embodied subject and the actions take place within a regional world of professional practice, the mind of the teacher is integrated with the body in the sense that the mind has settled in the body as a way of thinking, seeing, feeling and being as a professional in a habitualized world of practice (Bengtsson, 1993). Research experience shows that there is often a difference between what teachers say they do and what they actually do in the classroom (Claesson, 2004). This does not mean that teachers are lying. They simply do not have the necessary distance from their own practice to be able to describe what they are doing. Instead, they are more likely to describe an ideal of their work.

These comments should not be taken to mean that interviews should be excluded from the lifeworld approach. However, just as observing people's physical behaviour only tells us some things about them in the same way interviewing people only tells us certain things about them. The advantage of interviews is that they allow people to talk about situations that are passed, situations that ethically delicate for participation such as sexuality or violence and situations that are hard to observe, such as working pleasure. When interviews are used within the lifeworld approach it is important to understand that the interviewer should help the interviewee to introduce a distance from his/her own lifeworld and conduct the interview in a corresponding manner. In this way the interviewees are helped to reflect upon and talk about different aspects of their lives. The persons should be stimulated and helped to see their lives and experiences in their worldly and embodied existence and not as decontextualized experiences or cognitions. In order to avoid general answers about the interviewees' lives, it can be useful to ask for examples. Different strategies have been used in interviews of people in the lifeworld approach. These include in-depth interviews and narrations, which are sometimes complemented by drawings, writings, models (Alerby, 1998; Andrén, 2012; Hörnqvist, 1999; Houmann, 2010; Kostenius, 2008; Nielsen, 2005; Öhlén, 2000; Öhrling, 2000; Orlenius, 1999; Vinterek, 2001).

Interviews and observations are not seen as opposing factors in the lifeworld approach as they were in the early days of qualitative research. Instead, these methods may be used separately, depending on the research question, but they can also be combined in different ways in order to complement each other. If different methods are used, however, it is necessary that they have the same theoretical ground. Methods are never free from theoretical assumptions. If different methods with different theoretical assumptions are used in the same research project, the results from the different methods can come into conflict with each other and will not contribute to the understanding of the phenomenon. With the lifeworld as a ground, several studies have used mixed methods (Berndtsson, 2001; Carlsson, 2011; Claesson, 1999, 2004; Grundén, 2005; Hautaniemi, 2004; Hertting, 2007; Hugo, 2007).

This paper has already touched upon hermeneutics several times. It seems necessary to comment on the relationship between lifeworld phenomenology and hermeneutics. In this way the discussion of methods is continued by way of a discussion of interpretation. Classical phenomenology (such as that form of phenomenology represented by the Hegelian tradition as an example) and classical hermeneutics (represented by scholars from the days of Schleiermacher through to neo-Kantians such as Dilthey and Weber) are certainly two different traditions. However, in the new phenomenology started by Husserl around 1900, possibilities for integration of the two traditions were revealed. Heidegger was the first phenomenologist to introduce hermeneutics in phenomenology (Heidegger, 1927). In so doing he renewed both Husserl's phenomenology and hermeneutics. Gadamer (1960) and Ricoeur (1965, 1969) continued this direction in different ways. The ground for the integration of phenomenology and hermeneutics can be found in lifeworld phenomenology (Bengtsson, 1988b). Phenomenology and hermeneutics are thus not parallel traditions that never meet in the lifeworld approach.

In the lifeworld approach, interpretation and understanding are not limited to texts, but also include tools and actions. The neo-Kantian tradition also includes the interpretation of actions, but in contrast to lifeworld hermeneutics, this approach looked for the meaning of texts and the actions behind them in the intentions or life of authors or agents. Lifeworld hermeneutics tries to understand texts and actions by the meaning that is expressed in the text and action respectively. This idea goes back to Husserl's criticism of psychologism in logics and mathematics in the first volume of Logische Untersuchungen [Logical investigations] (Husserl, 1980a). Schutz (1932) continued the neo-Kantian tradition in his hermeneutics of social actions instead of developing the new possibilities in phenomenology (cf., Bengtsson, 1998, 2002).

Interpretation in empirical research can also not be limited to the interpretation of transcribed interviews or observations. Seen from the perspective of lifeworld hermeneutics, interpretation already starts in the interview and observation, and the object of interpretation is not the transcriptions, but the interviews and the observations.

In the lifeworld approach, empirical research in education implies that the both the people who are studied and the researchers are inseparably embedded in their different lifeworlds. Bridges must therefore be built between the lifeworld of the researcher and the lifeworld of the participants of the study. The primary means for building bridges involves creating encounters with other lifeworlds (Bengtsson, 1999). Two main methods have been discussed for this purpose, observation and interview, and it has been mentioned that these methods can be combined. The use of both methods implies the existence of the hermeneutic circle from the beginning of the research. We always already understand and interpret through our being in the world. It is not possible to escape the hermeneutic circle, but the encounters offer the possibility of exposing and confronting our prejudgements (Vor-urteile - to use Gadamer's (1960) word) and letting the other lifeworlds speak in their otherness. Encounters enable the researcher to make discoveries and to change pre-judgements.

Choice of method

So far only methodological questions relating to the lifeworld approach have been discussed. However, methodology is concerned with general principles or guidelines on how to conduct research. It can therefore not be equated with the choice of method in particular empirical projects that seek to answer specific research questions. This is of particular importance for the lifeworld approach, where creativity is demanded in the choice of method (Bengtsson, 1999). In other words, the lifeworld approach is not equivalent to a particular method. The choice of method should instead be made based on a combination of the research question and the ontological understanding (in this case lifeworld ontology) of the particular reality that the project intends to study.

To deepen the understanding of the principle of creativity of method it could be described in the context of a phenomenological dilemma. The phenomenological movement started with a demand that phenomenology should "go back to the things themselves" (Husserl, 1980b, p. 6) as they appear and do full justice to these things. This demand, however, can easily come into conflict with a demand for method in scientific research. The prescriptive rules of scientific methods only provide the type of knowledge that the methods permit. However, in that case, research seems to do more justice to its methods than to the things themselves. Consequently, it seems that the researcher has to choose between following the things or some particular method. This choice is not as simple as it might seem. This is because the phenomenological demand of doing justice to the things seems itself to be a methodological principle. The dilemma is therefore actually a paradox.

The conflict between following the things or a particular method only exists if the method must be applied in all research, or in other words if this implies that a general methodology exists that should be used indiscriminately in all educational research. This demand is in conflict with the demand of following the things. However, it is also possible to develop methods from the combination of the particular research question and the ontological understanding of the things to be studied. If research is done in this way then there is no conflict between method and things.

The paradox thus only exists if the demand for going back to the things is understood as a developed method. However, it is certainly not a developed method. Instead, it is generally formulated and contains no prescriptions regarding the procedure for concrete research questions. I would propose that within empirical research it should be understood as a kind of general principle for choice of method. In that case, it should be read as a requirement to let the choice of method be decided by its ability to do justice to the regional lifeworld to be studied. An example can be found in Eva Johansson's thesis described below.

The lifeworld approach therefore cannot present a rigid procedure that can be used in all empirical lifeworld research and that can be used for judging research results. This also applies to methods of gathering and analysing empirical material. It is not possible to trust one correct method in the lifeworld approach and the researcher must therefore carefully work out and argue for a chosen method or methods in a project. Consequently, the lifeworld approach stimulates creativity of methods.

The illusory conflict between the demand of going back to the things themselves and the demand of scientific method has sometimes led to a neglect of method in phenomenological empirical research. This is, for instance, the case with the Utrecht school that represents an anthropological-phenomenological approach to educational research. The research in this approach has often been more or less impressionistic and lacks discussion regarding the way in which the results were determined. In Van Manen's (1990) version of phenomenology, phenomenological research has been compared to the art of poetry and "a primal telling" (p. 13) that gives voice to the world. This phenomenological direction therefore provides as little description and discussion of method as does poetry. However, the opposite tendency is also represented in the phenomenological tradition, and relates to the demand for strict scientific principles of method. Examples are Moustaka's (1994) and Giorgi's (1997; Giorgi & Giorgi, 2008) more or less detailed procedures for conducting phenomenological empirical research. All three of these procedures demand the application of the phenomenological epoché, the particular method that Husserl introduced in his transcendental phenomenology for philosophical purposes (Husserl, 1976), and a general procedure for analysis of all studies (Giorgi, 2010). Peter Ashworth continues this methodology, but has added a number of categories of the lifeworld to enable descriptions (described above) (Ashworth, 2003; Ashworth, Freewood, & Mac-donald, 2003). The lifeworld approach offers an alternative to these two options of doing empirical phenomenological research.

Reporting results

A lot of contemporary research in different directions of qualitative research uses the word 'findings' for its results. However, this is a very misleading term. This becomes clear as some examples of its use are discussed. For example: "We found mushrooms just outside our house" or "we found a parking-place outside the railway-station". If the word is used in this manner to describe research results it provides the impression of an effortless finding of the results or simply coming across these results. However, all parts of research are hard work and this includes arriving at and reporting results.

At least three ways of reporting results have been used in the lifeworld approach. Firstly, reporting separately for each individual within a project (Berndtsson, 2001; Claesson, 1999; 2004; Nielsen, 2005); secondly, reporting thematically across the individuals (Alerby, 1998; Carlsson, 2011; Ferm, 2004; Friberg, 2001; Greve, 2007; Grundén, 2005; Hautaniemi, 2004; Hertting, 2007; Hörnqvist, 1999; Houmann, 2010; Hugo, 2007; Johansson, 1999, 2007; Kostenius, 2008; Løkken, 2000; Öhrling, 2000; Orlenius, 1999; Vinterek, 2001); and thirdly, reporting first individually and then, based on these results, thematically (Andrén, 2012; Öhlén, 2000).

The work of reporting the results starts with interpreting what people have said or/and done. It is appropriate at this juncture to introduce critical distance in the work, both in relation to the researcher and to the people included in the study. This can be done by means of self-reflection and collegial discussion (Bengtsson, 1993). I also believe that Ricour's (1965) hermeneutics of suspicion as well as Dahlberg, Dahlberg and Nyström's (2008) notion of bridling can be of use in this context. When an understanding of the said or/and observed has been reached, the work of reporting the results continues by means of the systematic organization of answers to the research question. Strict procedures are not a guarantee of relevant results.

The language used in reporting results is always the language of the researcher, irrespective of whether the study is based on interviews or observations of activities, including speech. In the lifeworld approach language is not limited to ordinary language, but also includes the use of phenomenological language. It seems unprofessional to not use the wealth of this language to provide more precise and profound descriptions of the results. Phenomenological language cannot, however, be used in a general way, but instead has to be used descriptively. The word 'horizon' could be an example. It has been used in a general way to describe the perception of space (Husserl, 1972; Merleau-Ponty, 1945), the experience of time (Husserl, 1972; Merleau-Ponty, 1945) and understanding (Gadamer, 1960). However, it has also been used descriptively in order to refer to displaced horizons in describing the changed world of everyday life for people who have lost their sight (Berndtsson, 2001).

The results of the lifeworld approach cannot be generalized for the simple reason that the principle of induction is not (and cannot be) used. This principle cannot be used because the number of participants involved in these explorative studies is insufficient for generalization. For the same reason, participants are not selected randomly but instead are selected according to a strategy. This strategy relates to the question of what type of participant can bring something new to the exploration of the field. The principle of induction is not used because it is questionable in general. Although it is not necessary to agree with Popper's own theory, he certainly formulated strong criticism against induction (Popper, 1959). It is also not possible to make claims of essences based on the results of the lifeworld approach. An essence, in the strict sense of the word, has to describe the necessary and sufficient qualities of an object. In other words, an essence must describe how it has to be at all times, in all cultures and for all people. It is not possible for empirical research to fulfil this task. Empirical research can identify empirical themes, but these should not be confused with essence. The strength of the results of the lifeworld approach is that they are able to show the significance of the results in relation to other empirical and theoretical research within the field of the research question and its use for practice.

Example

In order to demonstrate what the lifeworld approach can offer for empirical research in education, I now outline an example from research in the Gothenburg tradition, a doctoral thesis by Eva Johansson (Johansson, 1999).

Johansson's thesis is a study of small children's moral values and norms in their interaction in preschool. The children's interaction with the preschool teachers was not included in the project. The study was based on the daily interaction among 19 children, ten boys and nine girls, aged one to three years. The interaction was followed for seven months and video recorded. The research questions were based on the lifeworld assumption that interaction between people is meaningful and accessible for the parties involved. One important part of people's interaction is its moral dimension, which is experienced and expressed through people's embodied interactions with each other. A research question could therefore focus on the values and norms that small children experience and express. According to Piaget (1932), small children cannot be asked this question because morality is linked to the Kantian idea of self-responsibility. Consequently, people can be moral only when they know themselves and take responsibility for their own actions, and small children have not reached this stage. Piaget (1932) therefore describes small children as simply amoral.

In lifeworld ontology, meaning and value in interaction do not primarily refer to people's inner subjective intentions, but instead refer to the meaning and value that they experience and express through their lived bodies. For this reason, the study was based on observations of the children's embodied interaction. There were two reasons why interviews were not considered an appropriate research method. First, the moral values and norms were not supposed to be found within the children, but instead in the embodied interaction between them. Second, the children were too young to have functional language. Thought experiments were also excluded as a research method for two reasons. Firstly, because morality was not conceptualised as an intellectual task or ability. Secondly, because the children were too young to solve intellectual dilemmas. It was also important for the lifeworld approach that the children's moral interaction be studied in its lived environment. This is because the meaning and value of experiences and expressions never occur alone; instead they occur together with the meanings and values of specific things and other people that constitute a particular regional world of meaning. It was, therefore, not an alternative to use thought experiments or interviews outside the lived world of interaction where the meanings and values are created and sustained.

Johansson's (1999) thesis thus used observation, documented by video records, to build bridges between the researcher's world and the children's world. In this manner, the meaning of the experiences and the expressions of the interaction were available to the observing researcher, but they were available from within the world of an observing adult researcher. This does not mean that the children's morality was not understood in its otherness. The values and norms of the children were certainly observed, but it was neither necessary nor possible to completely take the children's perspective. Taking another person's perspective would imply experiencing in the same way as the other person, and this is not possible without reducing his/her otherness. The researcher, therefore, has to begin with what is observed from his/her perspective and then try to confront this with the encountered world of the children. Johansson's (1999) study is based on very rich empirical material, with observations of many interactional situations over an extended period of time. By recording all these situations, she could confront her initial understandings of them by looking at them several times and in this sense developing an ongoing hermeneutical dialogue with the situations. In this way, her results could be reported in an explicit, argued way.

In the results of her study, Johansson (1999) showed that morality is an important part of the children's life at the preschool. The children defended and valued their own rights and cared for others' well-being. They defended their rights to things, as well as to sharing worlds with peers. Their concern for other children's well-being was expressed in efforts to comfort and protect them from harmful situations. Johansson's (1999) results clearly show that even very small children experience and express moral values and norms. By doing so, she showed that the results of Piaget's research were wrong. This is indeed a strong contribution to this field of knowledge.

Conclusion

In this article, I have tried to show some distinctive characteristics of the lifeworld approach and its consequences for empirical research in education. First, I have argued for the necessity of being explicit about the direction within the phenomenological movement from which a phenomenological study is conducted. The lifeworld approach is based on lifeworld phenomenology. Second, I have tried to show that a transition from philosophical to empirical research is needed. Third, as a way of achieving the transition, I have suggested the inclusion of an explicit discussion of the ontological and epistemological assumptions in the research design. Fourth, I have compared three traditional ontologies with the lifeworld ontology in order to highlight some significant differences in the understanding of reality. Fifth, I have argued for the necessity of delimiting ontology to the regional ontology of the particular reality that is in focus in particular projects of educational research. In other words, I have argued that ontology should be focused on that part of reality that the research question has singled out in its formulation. The intention of this delimitation is to adapt ontology to empirical research. Sixth, I have discussed some methodological consequences of the traditional ontological theories and the lifeworld ontology in order to make some of the particularities of the lifeworld approach visible. Seventh, I have shown the importance of creativity in the choice of method for empirical research. This principle offers an alternative to the demand for strict, scientific procedures for all research and to the neglect of methods in research. Instead, the choice of method should be made based on a combination of the research question and the ontological understanding of the particular reality that the project intends to study. Eighth, I have discussed ways of reporting results in the lifeworld approach. Finally, I have shown what the lifeworld approach can offer for empirical research in education by presenting the design and results of one empirical study based on the lifeworld approach.

In the lifeworld approach, the integration of philosophy and empirical research is not only an ideal. It is also an explicitly developed approach that is realized in ongoing research. The research approach is consequently and coherently based on lifeworld phenomenology. This gives the lifeworld approach its own particular perspective in phenomenological, empirical research in education.

Acknowledgement

This text refers back to lectures I have been giving to students and colleagues since the 1980s. The text has profited greatly from these lectures. My thanks to all of you. A special thanks goes to Professor Ronald Paul for his kindness in correcting my English.

Referencing Format

Bengtsson, J. (2013). With the lifeworld as ground. A research approach for empirical research in education: The Gothenburg tradition. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 13 (Special Edition, September: Lifeworld Approach for Empirical Research in Education - the Gothenburg Tradition), 18 pp. doi: 10.2989/IPJP.2013.13. 2.4.1178

References

Alerby, E. (1998). Att fånga en tanke. En fenomenologisk studie av barns och ungdomars tänkande kring miljö [To catch a thought. A phenomenological study of the thinking of children and young people about the environment]. Unpublished dissertation, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden.

Andrén, U. (2012). Self-awareness and self-knowledge in professions. Unpublished dissertation, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Gothenburg, Sweden. [ Links ]

Ashworth, P. (2003). An approach to phenomenological psychology: The contingencies of the lifeworld. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology 34(2), 257-278. [ Links ]

Ashworth, P., Freewood, M., & Macdonald, R. (2003). The student lifeworld and the meanings of plagiarism. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology 34(2), 145-156. [ Links ]

Bengtsson, J. (1984). Husserls erfarenhetsbegrepp och kunskapsideal. Den teoretiska erfarenhetens begränsningar och den praktiska erfarenhetens primat [Husserl's concept of experience and ideal of knowledge. The limits of theoretical experience and the primacy of practical experience]. Gothenburg, Sweden: Report from the Department of Education, University of Gothenburg.

Bengtsson, J. (1986). Konkret fenomenologi [Concrete phenomenology]. Gothenburg, Sweden: Philosophical communications, Green series no. 21, Department of Philosophy, University of Gothenburg.

Bengtsson, J. (1988a). Sammanflätningar. Husserls och Merleau-Pontys fenomenologi [Intertwinings. Husserl and Merleau-Ponty's phenomenology]. Gothenburg, Sweden: Daidalos. [ Links ]

Bengtsson, J. (1988b). Fenomenologi: Vardagsforskning, existensfilosofi, hermeneutik [Phenomenological directions in sociology: Everyday research, philosophy of existence, hermeneutics]. In P. Månson (Ed.), Moderna samhallsteorier. Traditioner, riktningar, teoretiker (pp. 60-94). Stockholm, Sweden: Prisma. [ Links ]

Bengtsson, J. (1991). Den fenomenologiska rörelsen i Sverige. Mottagande och inflytande 1900-1968 [The phenomenological movement in Sweden. Reception and influence 1900-1968]. Gothenburg, Sweden: Daidalos. [ Links ]

Bengtsson, J. (1993). Theory and practice. Two fundamental categories in the philosophy of teacher education. Educational Review, 45(3), 205-211. [ Links ]

Bengtsson, J. (1998). Fenomenologiska utflykter. Människa och vetenskap ur ett livsvärldsperspektiv [Phenomenological excursions. Human beings and scientific research from a lifeworld perspective]. Gothenburg, Sweden: Daidalos.

Bengtsson, J. (1999). Med livsvärlden som grund. Bidrag till utvecklandet av en livsvärldsfenomenologisk ansats i pedagogisk forskning [With the lifeworld as ground. Contributions to the development of a phenomenological lifeworld approach in empirical educational research], Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

Bengtsson, J. (2002). Livets spontanitet och tolkning. Alfred Schütz' fenomenologiska samhällsteori [Spontaneity and interpretation. Alfred Schutz' phenomenological theory of society]. In A. Schütz (Ed), Den sociala världens fenomenologi (pp. 7-24). Gothenburg, Sweden: Daidalos. [ Links ]

Bengtsson, J. (2005). Med livsvärlden som grund. Bidrag till utvecklandet av en livsvärldsfenomenologisk ansats i pedagogisk forskning [With the lifeworld as ground. Contributions to the development of a phenomenological lifeworld approach in empirical educational research] (2nd rev ed.). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

Bengtsson, J. (2006a). Undervisning, profession, lärande [Teaching, profession, learning]. In S. Lindblad & A. Edvardsson (Eds.), Mot bättre vetande. Presentationer av forskning vid Institutionen för pedagogik och didaktik 2006 (pp. 108-114). Gothenburg, Sweden: University of Gothenburg, Department of Education, IPD-rapport 2006:06. [ Links ]

Bengtsson, J. (2006b). The many identities of pedagogics as a challenge. Towards an ontology of pedagogical research as pedagogical practice. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 38(2), 115-128. [ Links ]

Bengtsson, J. (2010). Teorier om yrkesutövning och deras praktiska konsekvenser för lärare [Theories about professional skill and their practical consequences for teachers]. In M. Hugo & M. Segolsson (Eds.), Lärande och bildning i en globaliserad tid (pp. 83-98). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur. [ Links ]

Bengtsson, J. (2011). Educational significations in school buildings. In J. Bengtsson (Ed.), Educational dimensions of school buildings (pp. 11-33). Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang International Publisher. [ Links ]

Bengtsson, J. (2013). Experience and education: Introduction to the special issue. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 32, 1-5. [ Links ]

Berndtsson, I. (2001). Förskjutna horisonter. Livsförändring och lärande i samband med synnedsättning [Shifting horizons. Life changes and learning in relation to visual impairment or blindness]. Unpublished dissertation, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Carlsson, N. (2011). I kamp med skriftspråket. Vuxenstuderande med läs- och skrivsvårigheter i ett livsvårldesperspektiv [Struggling with written language. Adult students with reading and writing difficulties in a lifeworld perspective]. Unpublished dissertation, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Gothenburg, Sweden. [ Links ]

Claesson, S. (1999). "Hur tanker du då?" Empiriska studier om relationen mellan forskning om elevuppfattningar och lärares undervisning [How did you figure that out? Empirical studies concerning research on pupils' conceptions in relation to teaching]. Unpublished dissertation, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Gothenburg, Sweden. [ Links ]

Claesson, S. (2004). LääarararLes levda kunskap [Teachers' lived knowledge]. Unpublished dissertation, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Dahlberg, K. (2006). The individual in the world - the world in the individual. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 6, 1-9. [ Links ]

Dahlberg, K., Dahlberg, H., & Nyström, M. (2008). Reflective lifeworld research (2nd rev ed). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur. [ Links ]

Descartes, R. (1975). A discourse on method / Meditations on the first philosophy / Principles of philosophy. (J. Veitch, Trans) London, UK: Everyman's Library. (Original work published between 1637 and 1644). [ Links ]

Ferm, C. (2004). Öppenhet och medvetenhet. En fenomenologisk studie av musikdidaktisk interaction [Openness and awareness. A phenomenological study of music didactical interaction]. Unpublished dissertation, Luleá University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden.

Friberg, F. (2001). Pedagogiska möten mellan patienter och sjuksköterskor på en medicinsk vårdavdelning. Mot en vårddidaktik på livsvärldsgrund [Pedagogical encounters between patients and nurses in a medical ward. Towards a caring didactics from a lifeworld approach]. Unpublished dissertation, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Gothenburg, Sweden. [ Links ]

Gadamer, H-G. (1960). Wahrheit und methode [Truth and method]. London, United Kingdom: Sheed & Ward.

Giorgi, A. (1997). The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 28(2), 235-260. [ Links ]

Giorgi, A. (2010). Phenomenology and the practice of science. Existential Analysis, 21(1), 3-22. [ Links ]

Giorgi, A., & Giorgi, B. (2008). Phenomenology. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology. A practical guide to research methods (2nd ed.) (pp. 26-52). London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Greve, A. (2007). Vennskap mellom sma barn i barnehagen [Friendship among small children in pre-school]. Unpublished dissertation, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway. [ Links ]

Grundén, I. (2005). Att återerövra kroppen. En studie av livet efter en ryggmärgsskada [Reclaiming the body. A study of life after a spinal cord injury]. Unpublished dissertation, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Hautaniemi, B. (2004). Känslornas betydelse i funktionshindrade barns livsvärld [The meaning of feelings in the lifeworld of disabled children]. Unpublished dissertation, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden.

Heidegger, M. (1927). Sein und Zeit [Being and time]. Tübingen, Germany: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Heidegger, M. (1973). Being and time. (Translator unknown). Oxford, United Kingdom: Basil Blackwell. [ Links ]

Hertting, K. (2007). Den sköra föreningen mellan tävling och medmänsklighet. Om ledarskap och lärprocesser i barnfotbollen [The fragile unity between competition and humanity: On leadership and learning processes in children's football]. Unpublished dissertation, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden. [ Links ]

Houmann, A. (2010). Musiklärares handlingsutrymme. Möjligheter och begränsningar [Music teachers' scope of action. Possibilities and limitations]. Malmö, Sweden: Publications from the Malmö Academy of Music. [ Links ]

Hörnqvist, M-L. (1999). Upplevd kompetens. En fenomenologisk studie av ungdomars upplevelser av sin egen kompetens i skolarbetet [Experienced competence. A phenomenological study of young people's experience of their own competence in schoolwork]. Unpublished dissertation, Luleá University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden. [ Links ]

Hugo, M. (2007). Liv och lärande i gymnasieskolan. En studie om elevers erfarenheter i en liten grupp på gymnasieskolans individuella program [Life and learning. The way towards knowledge and competence for seven under achievers at upper secondary school]. Jönköping, Sweden: Jönköping University Press. [ Links ]

Hundeide, K. (1977). Piaget i kritisk lys [Piaget in a critical light]. Oslo, Norway: Cappelen. [ Links ]

Husserl, E. (1916-1917). Lebenswelt - Wissenschaft - Philosophie: Naives hinleben in der Welt - Symbolisches festlegen durch Urteile der Welt - Begründung [Lifeworld - science - philosophy: Naïve living in the world -symbolic fixation through judgments about the world - founding]. (Manuscript B I 21 III). Louvain, Belgium: The Husserl Archives. [ Links ]

Husserl, E. (1936). Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie [The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology], Philosophia, 1, 77-176. [ Links ]

Husserl, E. (1950). Die Idée der Phänomenologie [The idea of phenomenology]. (Husserliana 2). The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff.

Husserl, E. (1952). Ideen zu einer reinen Phänomenologie und phänomenologischen Philosophie. Zweites Buch. Phänomenologische Untersuchungen zur Konstitution (Ideas pertaining to a pure phenomenology and to a phenomenological philosophy. Second Book. Dordrecht: Kluwer 1989). The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff. [ Links ]

Husserl, E. (1954). Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phanomenologie [The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology]. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. [ Links ]

Husserl, E. (1972). Erfahrung und Urteil [Experience and judgement]. Hamburg, Germany: Felix Meiner Verlag.

Husserl, E. (1976). Ideen zu einer reinen Phänomenologie und phänomenologischen Philosophie. Erstes Buch [Ideas pertaining to a pure phenomenology and to a phenomenological philosophy. First Book]. (Husserliana 3). The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff. [ Links ]

Husserl, E. (1980a). Logische Untersuchungen. Erster Teil: Prolegomena zur reinen Logik [Logical investigations]. (Volume 1). London, United Kingdom: Routledge. [ Links ]

Husserl, E. (1980b). Logische Untersuchungen. Zweiter Teil: Untersuchungen zur Phänomenologie und Theorie der Erkenntnis [Logical investigations]. (Vol 2). London, United Kingdom: Routledge. [ Links ]

Johansson, E. (1999). Etik i små barns värld. Om värden och normer bland de yngsta barnen i förskolan [Ethics in small children's world. Values and norms among the youngest children in preschool]. Unpublished dissertation, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Gothenburg, Sweden. [ Links ]

Johansson, E. (2007). Etiska överenskommelser i förskolebarns världar [Ethical agreements in the worlds of preschool children]. Unpublished dissertation, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Gothenburg, Sweden. [ Links ]

Kant, I. (1976). Kritik der reinen Vernunft [Critique of pure reason]. London, United Kingdom. (Original work published 1721). [ Links ]

Kostenius, C. (2008). Giving voice and space to children in health promotion. Unpublished dissertation, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden. [ Links ]

Kvale, S. (1996). InterViews. An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Langeveld, M. (1984). How does the child experience the world of things? Phenomenology + Pedagogy, 2/3, 215-223. [ Links ]

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning. Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Løkken, G. (2000). Toddler peer culture. The social style of one and two year old body-subjects in everyday interaction. Unpublished dissertation, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway. [ Links ]

Løkken, G. (2004). Toddlerkultur. Om ett- og toåringers sosiale omgang i barnehagen [Toddler culture. Social relationships among one and two years old children in pre-school]. Oslo, Norway: Cappelen. [ Links ]

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945). Phénoménologie de la perception [Phenomenology of perception]. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. [ Links ]

Merleau-Ponty, M. (2001). Psychologie et pédagogie de l'enfant [Psychology and child education]. Lagrasse, France: Verdier. [ Links ]

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Nielsen, C. (2005). Mellan fakticitet och projekt. Las- och skrivsvårigheter och strävan att övervinna dem [Between facticity and project. Reading and writing difficulties and the striving to overcome them]. Unpublished dissertation, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Gothenburg, Sweden. [ Links ]

Öhlén, J. (2000). Att vara i en fristad. Berättelser om lindrat lidande inom palliativ vård [Being in a lived retreat. Narratives of alleviated suffering within palliative care]. Unpublished dissertation, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. [ Links ]

Öhrling, K. (2000). Being in the space for teaching-and-learning. The meaning of perceptorship in nurse education. Unpublished dissertation, Luleå University of Technology, Luleá, Sweden. [ Links ]

Orlenius, K. (1999). Förståelsens paradox. Yrkeserfarenhetens betydelse nar förskollärare blir grundskollärare [The paradox of understanding. The meaning and value of professional experience when pre-school teachers become compulsory school teachers]. Unpublished dissertation, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Gothenburg, Sweden. [ Links ]

Piaget, J. (1932). Le jugement moral chez l'enfant [The moral judgment of the child]. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. [ Links ]

Piaget, J. (1937). La construction du reel chez l'enfant [The construction of reality in the child]. New York, NY: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Piaget, J. (1946). La psychologie de l'intelligence [The psychology of intelligence]. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. [ Links ]

Popper, K. (1959). The logic of scientific discovery. London, United Kingdom: Hutchinson. [ Links ]

Potter, J., & Whetherell, M. (1987). Discourse and social psychology. London, United Kingdom: Sage. [ Links ]

Ricœur, P. (1965). De l'interprétation. Essai sur Sigmund Freud [Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation]. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Ricœur, P. (1969). Le conflit des interprétations. Essais d'herméneutique [The conflict of interpretations: Essays in hermeneutics]. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. [ Links ]

Rubin, E. (1915). Synsoplevede Figurer. Studier i psykologisk Analyse [Visually experienced figures. Studies in psychological analysis]. Copenhagen, Denmark: Gyldendalske Boghandel nordisk Forlag. [ Links ]

Schutz, A. (1932). Der sinnhafte Aufbau der sozialen Welt [The phenomenology of the social world]. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. [ Links ]

Schutz, A. (1962). Collected papers (Volume I). The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1971). Beyond freedom and dignity. London, United Kingdom: Jonathan Cape. [ Links ]

Spiegelberg, H. (1960). The phenomenological movement. A historical introduction. The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff. [ Links ]