Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Fundamina

On-line version ISSN 2411-7870

Print version ISSN 1021-545X

Fundamina (Pretoria) vol.24 n.1 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2411-7870/2018/v24n1a7

ARTICLE

The phrase, "Should a claimant raise a claim, he will pay ..." In the division of an inheritance from Old Babylonia Tell Harmal*

Susandra van Wyk

Practicing attorney, notary and conveyancer of the High Court of South Africa; Post-doctoral Fellow at North-West University

ABSTRACT

I investigate the raison d'être of an irregular clause in two inheritance divisions from Old Babylonia Tell Harmal. The free rendering of the clause reads that if a family member to the division transgresses with a claim, a certain monetary reward -measured in units of silver - needs to be paid. Is the payment clause a precautionary measure ensuring adherence to the execution of the division's terms; similar to the payment clause in sales and adoptions? Or does the clause serve another function? I show that the choices of the involved family members within their family relationship, as deduced from the recorded ipsissima verba of each division, dictate the unique raison d'être of the payment clause in the division. I argue that within the framework of maintaining family relationships, the payment clause serves as a possible future division in securing compensation, compliance and protection for the involved family members' interests.

Keywords: Old Babylonia Tell Harmal; redemption; sanction; penalty; ancient inheritance; Old Babylonian contract; Mesopotamia

1 Introduction

The free rendering of the so-called payment1 clause reads that if any family member to the division of an inheritance2 transgresses with a claim, an agreed monetary reward - measured in units of silver - needs to be paid. The payment clause appears in two inheritance divisions excavated from the site of OB Tell Harmal.3 Maria de Jong Ellis transcribed, translated and indexed the two division texts as Text B [IM 52599] and Text D [IM 52624] from her study of four OB Tell Harmal divisions and one dispute settlement regarding an initial division. In the other two divisions4the family members exclude the payment clause. In the dispute settlement there was no payment involved notwithstanding a dispute raised by the one brother.5In OB the latter entails a reappraisal and redistribution of the initial inheritance awards or else the witnesses to the division would suffice to testify and affirm to the initial inheritance awards. Also, I find no payment clause in my study of forty six divisions from the OB city-states of Nippur, Sippar and Larsa.6It seems that the payment clause is at least an irregular practice in the divisions from OB Tell Harmal, Nippur, Sippar and Larsa.

The following questions arise in the free rendering of the payment clause and in context with the terms of each division. Is the payment clause a precautionary measure ensuring adherence to the execution of the division's terms similar to the payment clause in sales and adoptions? Or does the clause serve another function?

In OB sales7 and a family agreement such as an OB adoption,8 the payment clause usually contains at least two denominators. The one denominator is the description of the transgression; and the other, an agreed fixed payment ranging from the confiscation of the transgressor's property, or payment, or abandonment, or even death. In general, the clause may constitute as a straightforward deterrent and/or sanction and/or penalty and/or a redemption right to serve as compensation, and/or compliance and/or protection for the family members' interest.9 The OB adoption, that artificially creates family relationships,10 contains a certain formula in the payment clause. Such formula includes a statement along the lines that if the adoptee renounces his adopter - stating that "you are not my father/mother" - then the adoptee shall forfeit properties such as a "house, field, orchard, female and male slaves, possessions, and as much as there is". The raison d'être for the clause depends on the type of adoption and the context of the text.11 Such an adoption clause may constitute as a straightforward deterrent and/or sanction and/or penalty to at least ensure compliance with the reciprocal obligations in protecting the family members' interest. In the instance of transgression it serves as a compensation.12The OB sales do not include a generalised and/or unlimited "payment" usually present in the OB adoptions.13 Rather in OB sales the contractual parties agree to a specific amount possibly for the sake of compensation and fairness to prevent an excessive one-sided penalty.14 Some OB sales - due to special circumstances - include a redemption clause.15 Redemption literally means "getting back something which has been lost".16

When the parties cannot agree to a market-related price by means of the supply-demand bargaining process the sale is forced with the right of redemption.17 The forced sale entails that the seller cannot withdraw from the sale and negotiations, because of an agreed fixed price - the redemption right - based on a specific law custom/decreed or circumstances.18

I will show that the choices of the involved family members within their family relationship, as deduced from the recorded ipsissima verba of each division, dictate the raison d'être of the payment clause in the division. I propose that unlike the payment clause in OB adoptions and sales, the clause in the two Tell Harmal divisions does not function as a deterrent, sanction, penalty and/or as a redemption right. I argue that the clause serves as a possible future division, which means that a family member may in the future bring in money, or in other words buy an asset, to acquire a part of the inheritance portion initially awarded to another family member in the original (initial) division.

First, I will explain how the management of the shared inheritance may end with the conclusion of a division. Thereafter I will discuss the division's requisites and terms that dictate the raison d'être of the payment clause. To facilitate my discussion and for ease of reference, Tables 1 and 2 in the Addendum reflect Ellis' transcription and translation of both texts. Finally, I will explain the clause's function as a possible future division within the framework of maintaining family relationships.

2 What is an inheritance division?

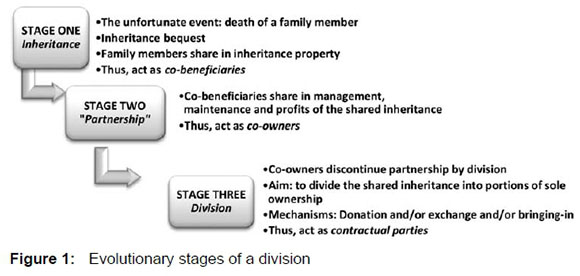

The division19 is a complex agreement which entails lengthy discussions and negotiations between family members.20 Before the family members finally agree on the terms, certain stages in an evolutionary sequence take place.21 The schematic outline in Figure 1 below supports my explanation of the stages.

The first stage starts with the death of a family member. The inheritance devolves to the deceased's beneficiaries. The second stage commences when the family members share in the management and enjoyment of use, as well as in the profits of the shared inheritance property, acting in their capacity as co-owners in a kind of partnership. At a later stage, the family members may decide to divide certain or all the shared inheritance property into portions of sole ownership (stage three). The process is based on creating obligations in maintaining family relationships rather than creating ownership's entitlements of exclusion, financial gain and competition to control. During the decision-stage of dividing the inheritance the family members enter into discussions, considering various factors and deciding on the application of certain legal practices. The scribe then records the terms on a tablet; however, the recording is an abbreviated version of the oral division.22

3 Requisites and legal practices23

A family in the Old Babylonian period commences with a distinction of the core family in anthropological terms, namely a married man and woman and their children who lived together as a core unit (in the first instance).24 The core unit is part of an extended family consisting of several core unit families who shared a common ancestor (second and third instance). The extended family members connect and bind themselves, and each other, by contract and fulfilment of obligations, in maintaining the family relationships.25

The inheritance division was an agreement amongst family members in dividing the estate of a deceased family member. In the OB period, the inheritance division was one type of division among other divisions, such as the guasi-adoption division, dissolution of a partnership and division of the estate assets of a living estate owner. The different divisions shared a common element, namely the dissolution of co-ownership by dividing the shared asset/s into portions of sole ownership. However, the types of divisions differed in the requisites needed to achieve the aim of dissolving co-ownership.26

The division of an inheritance deriving from the estate of a deceased family member has certain requisites that qualified the agreement as such, namely: (1) the family members involved; (2) the deceased owner of the estate or testator; (3) the estate assets or inheritance; (4) mutual consent, expressed with specific terms; and (5) the raison d'être with the option of three mechanisms in dividing the inheritance.27

The legal practices which the family members as contractual parties expressly or tacitly decided to exclude or include in the division depended on the family members' personal circumstances, architectural and agricultural factors.28 Overall the values of certainty and economic sustainability underpin the family members' decisions in the dividing up of the inheritance awards and the foreseen consequences of the division's terms.

The recorded division's details and purpose were limited to the scribe's idiosyncratic style of recording29 the terms onto a clay tablet.30 The legal practices31which occur in the two texts are sub-categorised as follows:

-

As regular practices that are the formalities, implementation and enforcement of the division: the no claim, oath, and witnesses' clauses

-

As irregular practices that are

- symbolic expressions: the heart is satisfied32 and equal shares33 clauses; and

- additional conditions and terms: the firstborn share,34sui generis usufruct35and payment clauses

Next, these requirements listed above for a division will be applied to Ellis' Text B [IM 52599] and Text D [IM 52624].

4 Both texts' requisites for qualifying as a division36

4 1 Family members involved

In both texts, identification of the type of relationship between the deceased owner/ testator and involved family members is possible by means of an analysis of the structure, context and terminology of the texts, as well as clues from other texts and taking cognisance of the application of an array of OB legal practices deduced from the texts.

References in both texts which show that an inheritance portion from a family estate is awarded to a family member are the Akkadian term zi-it-ti37 in lines 6 and 11 of Text 1 and the Sumerian term ha-la38 in Text 2, lines 7 and 11.

In Text 1, lines 12 and 13, the persons receiving the awards are Ipiq-Amurru and Ana-Šamaš-balati; however, their family status has led to some controversy. I agree with Ellis39 that the grammatical structure of the terms indicate that this is an inheritance division and that the involved parties are the sons or at least the grandchildren of the deceased parent. In addition, line 16 reflects the no claim clause stating that brother against brother (a-hu-um a-na a-hi-im) will not raise a claim (i-ra-ga-mu) suggesting an agreement between brothers.

Ellis40 surmises that in Text 2 there are "no patronymic given" but refers41 to other texts mentioning Igmil-Sin and Warhum-magir as the sons of a "well-known" Damqanum. Ellis42 concedes that it is "probable" that Nanna-mansum is the third brother, or at least a nephew.

I propose that Text 2 is a division between family members, and that the three male family members are brothers. This is suggested by the context of lines 3-4 which state that "his brothers will share equally" (read together with lines 16-18) in the no claim clause which state that brother against brother (a-hu-um a-na a-hi-im) will not raise a claim (i-ra-ga-mu). The family members' names in the text are Nanna-mansum in lines 2 and 7, the brothers Igmil-Sin in line 13 and Warhum-magir in line 11, as well as Zibbatum, a naditu priestess of Šamaš,43in lines 1 and 3. As later discussed Nanna-mansum in line 2 receives a double share in the "property of Zimbatum" consisting of orchards and a house. Ellis44 opines that it is Zibbatum's estate that is divided and that she is either the deceased aunt or sister of the involved family members (the three brothers). In the next section I will argue that Zibbatum is still alive and not the estate owner. She is the priestess-sister who is receiving lifelong maintenance support.45

4 2 Deceased owner / testator: Family member / parent

I surmise that both texts omit the deceased owner's name and gender and glean my interpretations from the structure, context and terminology of the texts and the OB practices applicable in and/or deduced from the texts.

In Text 1, line 12 refers to "his sons" and the no-claim clause in lines 15-17 states that brother will not lodge a claim against brother (a-hu-um and a-hi-im). This implies that the deceased owner is possibly the deceased parent.

However, in Text 2, the framing of the deceased owner's identity, status and position is contentious. Ellis'46 concedes that it is the estate of Zibbatum, a naditu priestess of Šamaš, that is divided and presumes that the deceased Zibbatum is either the deceased aunt or sister of the beneficiaries/contractual parties. Ellis47 mainly based this on her rendering of line 1, reading: "In the matter of the property of Zibbatum, the naditu of Šamaš, of orchards and house Nanna-mansum will take his double share, and his brothers will share equally." I disagree with Ellis. In most OB divisions the written record starts with a description of the inheritance property, following with the name and usually the family status of the recipient.48 At first glance it may therefore appear that Ellis49 is correct assuming that the estate of Zibbatum, the naditu, is divided. However, a recording is only an adaptation and abridged version of an oral division.50 The details are mostly obscured, and we cannot base our interpretations only on the rendering of the text.51 The naditu's position, status and her property ownership in OB society has a direct relevance on the understanding of the first line's meaning.52 One of the functions/roles of the naditu-institution is the continuation of the patronage.53 In OB it was an accepted practice that a naditu of the god Šamaš receives her inheritance from her father. Usually this is a sui generis usufruct over a certain portion of the family property. The property stays within the patrilineal group, the bare-dominium owner. At the death of the father, the portion of the family property devolves to the next line in the patrilineal group. However, the property is subject to a sui generis usufruct, as a lifetime of support in favour of the naditu.54 Hence in Text 2, Zibbatum holds the sui generis usufruct over the orchards and house as a lifetime of support. In addition the deceased owner is the deceased patron of the family, either the uncle or - more likely - the father of the family members involved in the division.

Thus, from the context of the texts, I deduce that both texts reflect a division between family members of their parental and/or great-parental estate (ie inheritance).

4 3 Estate assets / inheritance: Fully or partially divided

Both texts give an abbreviated description of the estate assets (inheritance) which is in contrast to the detailed description of estate assets found, for instance, in the divisions from the city-state of OB Nippur55 and in some OB Larsa texts.56 The elaborate list of witnesses in the Tell Harmal texts may compensate for the abbreviated description of assets since the witnesses assisted in retaining knowledge about the identification of assets and terms of the division. In case of a later dispute they might have to testify to the details of the division.57

Text 1 consists of movable and immovable property. The recording regarding the movable assets includes a description of various kinds of wooden objects; however, concerning the immovable property, the scribe only describes a field. Table 1 (infra) shows the outline of the type of portions awarded to each family member and the mechanisms used, with the differences emphasised in small caps.

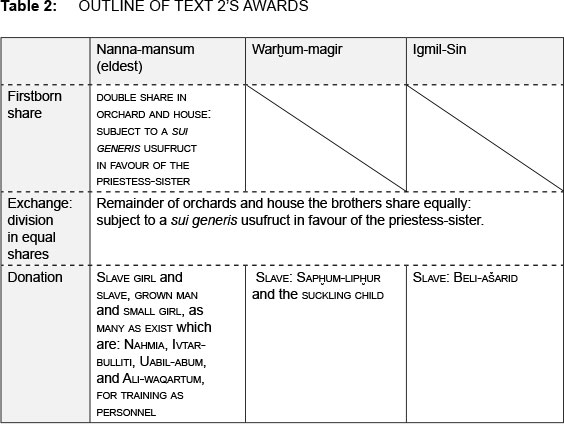

Text 2 consists of an unidentified orchard and house; however, the scribe records the slaves by their names and, in the case of some slaves, the scribe includes their gender and a description of their social status, such as small girl or suckling child. Table 2 (infra) gives an outline of the mechanisms used and the type of portions awarded to each family member, with the differences emphasised in small caps.

4 4 Mutual consent

In both texts, the expression i-zu-zu / i-zu-uz-zu / zi-i-zu-ú may be interpreted as "they mutually agree to the terms of the division".59 In Text 1, line 13 contains the term i-zu-zu - and in context it may be interpreted as "they agree to the division". In both texts the mutual consent clause is strengthened by the statement that their hearts are satisfied, that is, they reached consensus regarding the terms of the division with the added assurance that each family member agrees not to claim in the future.

4 5 Raison d'être

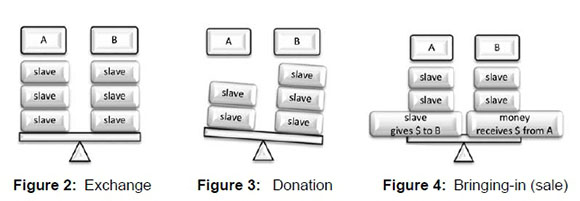

The aim of the division, within the framework of family relationships, is to divide the shared inheritance into portions of sole ownership using three mechanisms, namely a donation and/or exchange and/or bringing-in (sale), as illustrated in Figures 2, 3 and 4 (infra).60

Although, in both texts, the family members to the division used two of the three mechanisms, namely an exchange and a donation, there is a variation in the description of the type of mechanism used.

Thus, in Text 1 an exchange and donation between the brothers take place, deduced from the context of the text. The two brothers divide some wooden objects and a house of forty eight square metres61 between them. The scribe, however, omitted the equal shares clause (mit-haris). The wooden objects were not precisely divided. Thus, it seems that a donation took place (see Table 1 supra). While, in another term in Text 1, a field is equally divided, as may be seen from the inclusion of the term mit-haris62

The donation and exchange are also mechanisms used in Text 2. In line 1, from the context of the text, I deduce that the one brother received a firstborn share63concerning an orchard and house which is subject to a maintenance claim (sui generis usufruct) in favour of the priestess-sister. Then the remainder of the orchard and house is divided between the three brothers with the inclusion of the mit-haris-term, stating that the division is made into equal shares. However, further on in Text 2, the brothers award interchangeably a donation and exchange, as deduced from the context of the text, without mentioning the equal shares clause (mit-haris).

See Table 2 supra showing the equal (exchange) and unequal (donation) division of the awarded property among the brothers, reflecting as possibly the eldest Nanna-mansum who received the larger part of the assets, then the brother Warhum-magir, and lastly Igmil-Sin, who receives the least assets of the three brothers.

5 General legal practices

5 1 Formalities, implementation and enforcement of the division

The three general legal practices enforce and strengthen compliance with the division's terms. The no-claim and oath clauses reflect the viva voce commitments by the involved family members to adhere to the terms. In addition the witnesses' clause identified the witnesses who will confirm the terms in the instances of a transgression/ dispute by any of the involved family members. Thus, the three practices serve as precautionary measures to prevent transgressions.

5 1 1 No-claim clause

The no-claim clause as a regular64 term in OB divisions and other legal texts65 occurs in both texts (Text 1, lines 15-16, and Text 2, lines 16-18) reading: "They will not return brother against brother they will not raise (or shout) a claim against the other."

5 1 2 Oath clause

Text 1,66 line 19, translates as "to swear an oath to Tispak and Ibal-pi-El". In Text 2, line 21, the oath clause translates as "they swear by the names of Tispak and Dadusa the King". Religion serves a vital role in the assurance for compliance. Although the oath clause is a general clause, it is not always included in the recorded agreements.67

5 1 3 Witnesses clause

The witnesses68 appear in the presence of the contractual parties since in both texts, the Sumerian variant, igi, is inscribed before the names of the witnesses.

According to PSD, igi means "face, in front of, translated as "before".69 Thus, the witnesses witness the proceedings, after which they may testify and their function is consequently much wider than that of attestation.70 For instance, in a settlement from OB Tell Harmal a dispute is resolved around the division of a field of unknown measurement. The solution necessitated the acquired "knowledge" of another brother, Ilsu-ibbisu, of the contested division and "anyone else" at the gate of Belgaser. The previous division is probably concluded at the gate and the witnesses of that division had to testify as to how the field was equally divided previously.71

Both texts contain long lists of witnesses. There are eleven witnesses in Text 1 and fourteen in Text 2.72 In Text 1, lines 21-29, among the witnesses present are included two scribes (dub-sar) and a seal engraver (bur-gul). It is curious that two scribes were present, but they may have been professionals who participated in the recording of the division, together with the aforementioned seal engraver who engraved the seals. Other witnesses whose professions are mentioned, are an instructor, stone-cutter (ugula73 zadim74) and a mature soldier (aga-us75 gal76-kud). Thus, Text 1 includes an elaborate list of witnesses, of whom some held professions and the scribe deemed it necessary to include their professional status as part of their identification as witnesses. In Text 2, lines 25-36, the witnesses' family status is mentioned. However, the witnesses' family status from lines 21 to 24 is not mentioned: the only reference is to the sakkanakku of Zaralulu and the elders of his city, as well as the sakkanakku of Atasum and the elders of his city, who were high officials of the city.77

6 Irregular legal practices

6 1 Symbolic expressions

Charpin78 remarks that the OB law contract involved "symbolic gestures engaging those who performed them and by the utterance of solemn words, all in the presence of witnesses who would remember the matter".79 In both texts, the symbolic expressions of legal practices occur, namely the heart is satisfied and equal terms clauses, although these expressions are irregular legal practices.

6 1 1 Heart is satisfied-clause

The heart is satisfied-clause80 ( li-ba-su-nu-û tà-ab) indicates that the family members are satisfied with the agreement. This constitutes an example of legal symbolism and expression, which Westbrook considers to be one of the general terms in cuneiform documents.81 Westbrook, in his discussion of the term, refers to LH paragraph 178 wherein an unmarried priestess concluded a division with her brothers and furthermore agreed to a maintenance award (sui generis usufruct). The priestess-sister receives "grain, oil and wool" for the value of her inheritance. However, the brothers shall satisfy her heart and if they fail to satisfy her heart, she may give the property to a farmer and take the full income.82 Westbrook concluded that, in this text, the onus rests on the brothers to deliver the rations "proportionate to the inheritance share". Therefore, the burden of proof of satisfaction did not lie with the priestess-sister.83

In both texts discussed here, from the context, we can deduce that each brother has the burden of proof to show that his "heart" is satisfied with the terms and conditions of the division.84

6 1 2 Equal shares-clause

The legal practice - mithāriš85- shows that the involved family members in both texts agree to divide the shared inheritance into equally divided assets86 and in a reading together with the i-zu-zu (they divided), it indicates that the family members agreed to an equal distribution or division.87

6 2 Additional terms: Practical procedure of a division

The family members agreed to implement certain practical procedures and/or traditions which assisted them in the winding-up of the division.

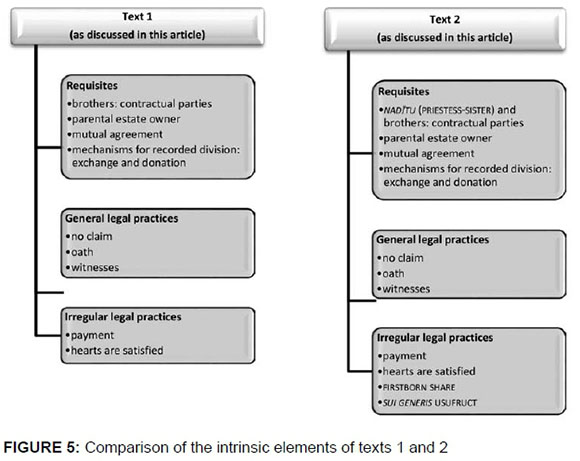

In both texts, the family members applied the payment clause. However, only in Text 2 did the family members agree to the inclusion of the firstborn share and sui generis usufruct clauses.

6 2 1 Firstborn share-clause

The firstborn share88 or privileged portion, or right of preference, denotes the situation where a family member, usually the eldest brother, receives an extra portion or percentage of the estate assets, before the division of the deceased paternal estate (inheritance) takes place.89 In Text 2, line 2, as an interpretation of the text, a certain Nanna-mansum took "his double share" as a firstborn share.

6 2 2 Sui generis usufruct (maintenance)-clause

In Text 2, lines 1-2, the family members agree to burden the orchard and the house with a sui generis usufruct (income proceeds), provided that the brothers will become the ultimate owners after a lifetime responsibility of managing the burdened property and maintaining their priestess-sister.

The sui generis usufruct90 is a practice whereby family members in a division agreed that certain members are burdened with the responsibility and obligation to support their priestess-sister.91 As mentioned before, the sui generis usufruct, interpreting from the context of the text, is confirmed in various sources, for instance in LH 178, 180, 181 and LL 22; OB letters;92 OB court case;93 and divisions.94

6 2 3 Payment clause

In Text 1, the free rendering of the translation reads "should a claimant raise a claim, he shall pay two minas of silver", and in Text 2 "should a claimant raise a claim, he shall pay four minas of silver".95 Silver is the medium of payment. However, the following question arises: Why are the amounts different? It is not a fixed price based on a specific law custom/decreed or circumstances. Thus, what was the basis and reason for such a calculation and/or payment? Are the variable amounts relevant in answering the posing question? What is the raison d' être of the payment clause in the two divisions? Are there any aspects present such as compensation and/or compliance and/or protection for the involved parties, similar to that of the payment clause found in sales and adoptions? And if so, does it dictate a similar or different raison d' être? In the following section I address these questions in my overall explanation of clause's raison d'être in the Tell Harmal divisions.

7 Provision for a possible future division

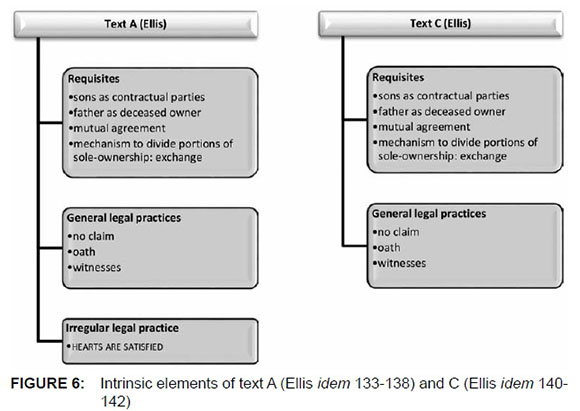

Both texts qualify as inheritance divisions wherein the scribe noted general formalities and the legal practices as synoptically illustrated in an overview in Figure 5 (infra) with the differences between the texts emphasised in small caps.

The only two mechanisms used in Texts 1 and 2 are the donation and exchange and thus the family members exclude the application of the third mechanism, namely the bringing-in or sale.96

Two values, within the framework of family relationships, may have underpinned the family members' decision as to which mechanism they decided to apply: (1) certainty, and (2) economic sustainability.

The first value, certainty, entails the continuation of the division to ensure that the advantaged family member retains sole ownership of the awarded portion of inheritance and that the family members comply with the terms of the division. As previously discussed the family members implicitly confirm this value by the inclusion of the no-claim clause, stating that they will not transgress with a claim against one another. In addition, two other general practices, the oath and witnesses' clauses reinforce compliance with the terms.

Concerning economic sustainability when deciding on the application of mechanism/s, it did not necessarily imply the achievement of an equal awarding of portions. However, the family members had to - at least - enforce a practical and reasonable dividing-up of the shared inheritance. Subsequently, when a family member (usually a brother) receives his awarded portion, he and his immediate family (wife and children) acted as a core family unit (within the greater family group) regarding that awarded portion.97 Consequently, it was essential that each award demanded reasonable economic sensibility to secure the future economic survival for each core family unit. This required that the awarded portion should hold equal economic value or at least the opportunity for the family members to have an equal opportunity for a sustainable income from the proceeds or use of the awarded portion.

The same principles apply in two other Tell Harmal divisions, translated, discussed and indexed by Ellis as Text A98 and Text C99. See, in Figure 7 infra, the abridged intrinsic elements of Texts A and C and the differences stressed in small caps.100 In these texts the family members implicitly fulfil the value of certainty by the inclusion of a no claim clause, stating that they will not in the future transgress with a claim. It seems that the family members satisfied themselves with the sustainability of the awarded assets by using the exchange mechanism. However, they exclude the payment clause.

Thus, while in Texts 1 and 2 (the focus of this article), the inclusion of the claim clause deters a family member to transgress in the future to any of the terms, a problem may arise regarding the sustainability of some awarded portions divided by means of a donation.101 One gets the better side of the deal - the higher value - and the other had to contend with awarded portions of a lesser value. This situation unjustly weakens the economic advantages of the latter's core family unit and adds to the ever-existing risk of hardship in agricultural and/or economic unforeseen and future unfortunate events.

However, in the event of a dispute over a division the end-result was not the payment for compensation. The settlement was either a reappraisal and redistribution of the initial inheritance awards or else the witnesses to the division would suffice to testify and affirm the initial inheritance awards.102 Still, the complexity of the division and choices in a reappraisal and redistribution of the initial division could add fuel to the ensuing dispute.103 This is in contradiction to family members' commitment to maintain their family relationships. The prevailing sensibility to avoid a family dispute is illustrated in an OB proverb stating as follows: "[I]f there be strife in the abode of relations, there is eating of uncleanness in the place of purity."104 I propose that this holds the key why the family members agreed to a specific momentary award in the payment clause. The family members may have foreseen possible risk of hardship and/or disputes and therefor the payment clause served as a pre-arrangement for a possible future division.105 This means that a family member may in the future bring-in money, or - in other words - buy an asset, to acquire a part of the portion initially awarded to another family member in the original (initial) division.106

Thus, it seems that the payment clause relieves the disadvantaged younger brother from the option of bringing-in money in the first instance of the original (initial) division, because of possible financial hardship. Then, at a later stage when he is financially capable, the clause affords the disadvantaged younger brother the opportunity to bring-in or buy a portion of the previously awarded inheritance from his advantaged brother. It is a fair situation for all the involved family members since prior to the original division they have already agreed to a specific amount of silver. Unfortunately, we cannot assess from the text how the family members calculated the compensation price (claim): whether it was based on sentimental and/ or economic value.

Thus, the clause's raison d'être is not to serve as deterrent and/or sanction and/ or penalty, and/or a redemption right. All the family members are protected: the one is served by preventing unjust compliance due to hardship, but the other is by prearranged agreement compensated for alienating a portion of his previously awarded inheritance.

8 Conclusion

I investigate the raison d'être of a payment clause as it appears in the two divisions (Texts 1 and 2) from OB Tell Harmal.107 I have shown that Texts 1 and 2 contain all the requisites for an agreement to qualify as a division wherein family members agree in accordance with Tell Harmal's legal practices to initially divide the shared inheritance from the deceased parent's estate into portions of sole ownership by means of a donation and exchange.

I submit that with the changing of co-ownership into portions of sole ownership, when a family member receives a lesser property, he may at a later stage be in a disadvantaged economic position. This situation unjustly weakens the economic advantages of his core family unit and adds to the ever-existing risk of hardship in agricultural and/or economic unforeseen and future unfortunate events.

Thus, by agreement in the original (initial) division, the family members in both texts may foresee the possible repudiation or variation of the initial division because of hardship. This is where the payment clause comes into play; offering the family members the opportunity in concluding a possible future division to afford the disadvantaged family member the option of altering the division since he will then be financially able to pay the compensation.

This compensation is pre-arranged by the calculation of a bringing-in or buying of inheritance shares to finally equalise the original division. Thus, the family members in the original division agree to a pre-arranged amount in silver, constituting the bringing-in/selling price.

Also, the compensation is fair for all family members concerned, for the brother who wants to alter the terms of the original division is forced to do so by means of a built-in payment. Consequently, in the interest of certainty, the payment clause defines the bringing-in of an asset and for adherence to economic sustainability allows for the possibility of an additional division to prevent hardship from an unsustainable awarded inheritance portion. Whilst, the no-claim, oath and witnesses' clauses serve as precautionary measures to prevent a family member from transgressing and at a later stage contesting the terms of the division.

In conclusion, the value of certainty is fulfilled by the compliance of the terms of the contract and the value of reasonable economic sustainability by the initial awarding of inheritance shares. These values are underpinned especially in the payment clause that serves the function of a possible future division in the compensation, compliance and protection of the family members' interests in maintaining their family relationships.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bottéro, Jean (1992) Mesopotamian Writing, Reasoning and the Gods (Chicago) [ Links ]

Charpin, Dominique (2010a) Reading and Writing in Babylon (London) [ Links ]

Charpin, Dominique (2010b) Writing, Law and Kingship in OB Mesopotamia (Chicago) [ Links ]

Charpin, Dominique (2013) Hammurabi of Babylon (New York) [ Links ]

Claassens, Susandra J (2012) "Family Deceased Estate Division Agreement from OB Larsa, Nippur and Sippar" vols 1 and 2 (D Litt et Phil dissertation, University of South Africa) [ Links ]

Claassens-van Wyk, Susandra J (2013) "OB Nippur solutions between beneficiaries in a deceased estate division agreement" J for Semitics 22(1): 56-89 [ Links ]

Ellis, Maria de Jong (1973) "OB economic texts and letters from Tell Harmal" J of Cuneiform Studies 24(3): 43-69 [ Links ]

Ellis, Maria de Jong (1974) "The division of property at Tell Harmal" J of Cuneiform Studies 26(3): 133-153 [ Links ]

Ellis, Maria de Jong (1975) "An OB adoption contract from Tell Harmal" J of Cuneiform Studies 27(3): 130-151 [ Links ]

Goetz, Charles J & Scott, Robert E (1977) "Liquidated damages, penalties and the just compensation principle: Some notes on an enforcement model and a theory of efficient breach" Columbia Law Review 77(4): 554-594 [ Links ]

Goetze, Albrecht (1958) "Fifty OB letters from Harmal" Sumer 14: 3-78 [ Links ]

Greengus, Samuel (1969) "The Old Babylonian marriage contract" J of the American Oriental Society 89: 505-532 [ Links ]

Greengus, Samuel (2001) "New evidence on the OB calendar and real estate documents from Sippar" J of the American Oriental Society 121(2): 257-267 [ Links ]

Harris, Rikva (1955) "The archive of the Sin temple in Khafajah (Tutub)" J of Cuneiform Studies 9(2): 31-58 [ Links ]

Harris, Rikva (1975) Ancient Sippar: A Demographic Study of an Old-Babylonian City, 18941595 BC (Istanbul) [ Links ]

Hibbits, Bernard J (1992) "'Coming to our senses': Communication and legal expression in performance cultures" Emory LJ 41(4): 873-960 [ Links ]

Jursa, Michael (2010) Aspects of the Economic History of Babylonia in the First Millennium BC: Economic Geography, Economic Mentalities, Agriculture, the Use of Money and the Problem of Economic Growth (Münster) [ Links ]

Langdon, S (1912) "Babylonian proverbs" The American J of Semitic Languages and Literatures 28(4): 217-243 [ Links ]

Leemans, WF (1986) "The family in the economic life of the Old Babylonian period" Oikumene 5: 15-22 [ Links ]

Magnetti, Donald L (1979) "'Oath functions' and the 'Oath process' in the civil and criminal law of the ANE" Brooklyn J of International Law 5(1): 1-28 [ Links ]

Malul, Meir (1988) Studies in Mesopotamian Legal Symbolism (Neukirchen-Vluyn) [ Links ]

O'Sullivan, Dominic, Elliott, Steven & Zakrzewski, Rafal (2008) The Law of Rescission (New York) [ Links ]

Obermark, PR (1992) Adoption in the Old Babylonian Period (published doctoral thesis, Hebrew Union College, University Microfilms International) [ Links ]

Oppenheim, AL (ed) (1961) The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (CAD) Z vol 21 (Chicago) [ Links ]

Postgate, J Nicholas (1992) Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History (London) [ Links ]

Potts, Daniel T (1997) Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations (Ithaca, NY) [ Links ]

Powell, Marvin A (1989-1990) "Masse und Gewichte" (Measures and Weights article in English), Reallexikon der Assyriologie 8: 457-517 [ Links ]

Powell, Marvin A (1996) "Money in Mesopotamia" J of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 39(3): 224-242 [ Links ]

Reiner, Erica (ed) (1992) The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (CAD) S vol 17 Part 2 (Chicago) [ Links ]

Renger, Johannes (1994) "On economic structures in Ancient Mesopotamia" Orientalia 63: 157208 [ Links ]

Simmons, Stephen D (1959) "Early OB tablets from Harmal and elsewhere" J of Cuneiform Studies 13(3): 71-93 [ Links ]

Simmons, Stephen D (1960) "Early OB tablets from Harmal and elsewhere (continued)" J of Cuneiform Studies 14(4): 117-125 [ Links ]

Sjöberg, ÂAke W (1984) Sumerian Dictionary vol 2B (Philadelphia) [ Links ]

Stone, Elizabeth C (1982) "The social role of the Nadltu women in Old Babylonian Nippur" J of Economic and Social History of the Orient 25(1): 50-70 [ Links ]

Stone, Elizabeth C & Owen, David I (1991) Adoption in Old Babylonian Nippur and the Archive of Mannum-mesu-lisssur, Mesopotamian Civilizations Series 3 (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns) [ Links ]

Suurmeijer, Guido (2010) " 'He took him as his son.' Adoption in old Babylonian Sippar" Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 104: 9-40 [ Links ]

Tinney, Steve J (ed) (1984) "The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary", University of Pennsylvania, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (online http://psd.museum.upenn.edu/epsd/nepsd-frame.html [cited 24 Feb 2014]) [ Links ]

Van Wyk, Susandra J (2013a) "Old Babylonian family division agreement from a deceased estate - analysis of its practical and theoretical mechanisms" Fundamina 19(1): 146-171 [ Links ]

Van Wyk, Susandra J (2013b) "Content analysis: A new approach in the study of the Old Babylonian family division agreement in a deceased estate" Fundamina 19(2): 413-440 [ Links ]

Van Wyk, Susandra J (2013 c) "A new translation of an Old Babylonian Sippar division agreement between brothers and a sister regarding their communally-shared inheritance" J for Semitics 22(2): 302-342 [ Links ]

Van Wyk, Susandra J (2014a) "Contractual maintenance support of a priestess-sister in three Old Babylonian Sippar division agreements" J for Semitics 23(1): 195-236 [ Links ]

Van Wyk, Susandra J (2014b) "Lost in translation: Present-day terms in the maintenance text of the nadiätu from OB Nippur" J for Semitics 23(2): 443-483 [ Links ]

Van Wyk, Susandra J (2015) "Prostitute, nun, or 'man-woman': Revisiting the position of the Old Babylonian nadiätu priestesses" J of Northwest Semitic Languages 41: 95-122 [ Links ]

Van Wyk, Susandra J (2018) "Inheritance feuds in the Ur-Pabilsag archive from Old Babilonian Nippur" (in press) [ Links ]

Veenhof, Klaas R (2003) "Before Hammu-räpi of Babylon: Law and laws in Early Mesopotamia" in Ferdinand Joseph Maria Feldbrugge, The Law's Beginnings (Leiden): 137-161 [ Links ]

Veldhuis, Nic (1997) "Elementary Education at Nippur: The Lists of Trees and Wooden Objects" (Doctoral dissertation, University of Groningen) [ Links ]

Von Soden, Wolfram (1965-1981) Akkadisches Handwörterbuch vols 1-3 (Wiesbaden) [ Links ]

Werr, Lamia al Gailani (1978) "A note on the seal impression IM 52599 from Tell Harmal" J of Cuneiform Studies 30(1): 62-64 [ Links ]

Westbrook, Raymond (1991a) "The phrase 'his heart is satisfied' in Ancient Near Eastern legal sources" J of the American Oriental Society 111: 219-224 [ Links ]

Westbrook, Raymond (1991b) Property and Family in Biblical Law (Sheffield) [ Links ]

Westbrook, Raymond (ed) (2003) A History of Ancient Near Eastern Law vol 1 (Leiden) [ Links ]

* This article is a revised and updated version of a draft paper presented at the annual meeting of the South African Society for Near Eastern Studies held at the University of Johannesburg (South Africa) on 1 September 2014. Sumerian terms are in bold font, Akkadian and Latin terms are italicised. The following abbreviations are used: OB = Old Babylonia/Babylonian; ANE = Ancient Near East/Eastern; LH = Law/Collection of Hammurabi; LL = Laws/ Law Collection of Lipit Istar. Abbreviations for dictionaries cited in this article are as follows: AHw = Akkadisches Handwörterbuch; CAD = The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago; CDA = A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian; PSD = The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary.

1 The "payment clause" is a coined term. Some scholars named the clause a "sanction" or "penalty clause", "restitution", "talion", or "compensation". It is recorded in different types of legal transactions. See, further, discussions under the heading Additional term: 6.2 (iii) Payment clause.

2 The "inheritance division from a deceased estate" is hereinafter referred as the "division/s" or "inheritance division". Different names are assigned to this type of agreement. For example, in Mesopotamian sources, the names are: partition agreement, partition, allotment, redistribution, division, undivided inheritance and family division agreement. Cf Claassens 2012(1): 1-2.

3 Tell Harmal represents the ancient city Shaduppum and is today part of the expanding city of Baghdad, in Iraq. Excavations were conducted at Tell Harmal from the late 1940s and onwards. Numerous types of clay tablets were excavated, including geographical and mathematical lists, as well as the known Laws ofEsnunna, published and discussed by Goetze from Ellis 1974: 133-153. De Ellis 1973: 43-69 published some texts from the Museum's general registrar, and compiled a catalogue as shown at 43-44. Other contributions pertaining to the Tell Harmal excavations include: Simmons 1959: 71-93; 1960: 117-125; Goetze 1958: 3-78; Ellis 1975: 130-151; and Harris 1955: 31-58.

4 Ellis idem indexed the two division texts as Text A [IM 51190] and Text C [IM 63305].

5 Ellis ibid indexed it as text E [IM 52590].

6 See my unpublished doctoral thesis in Claassens 2012(1) and 2012(2).

7 In the OB there is a vast array of legal transactions such as sale, lease, hire, loan, partnership, marriage, adoption, division of inheritance, etc. Usually the transaction contains at least a description of the transaction, witnesses list, a date formula, and sometimes seal impressions of the contractual parties and witnesses (Westbrook 2003: 362). Cf discussions by Westbrook 2003: 399-401 regarding the OB contract.

8 Cf ANE scholars' focus on the social and economic aspects of the OB adoption: Stone & Owen's 1991 study of the OB Nippur adoptions; Suurmeijer's 2010: 9-49 study of the OB Sippar adoptions; as well as Obermark's 1992 general study of the OB adoption.

9 Cf^estbrook 1991b: 90, 93-100; Stone & Owen 1991; Suurmeijer's 2010: 9-49; Obermark 1992; Greengus 1969: 515-518.

10 Suurmeijer 2010: 9.

11 Cf Suurmeijer 2010: 9-49; Westbrook 1991b: 90, 93-100; Greengus 1969: 515-518; and Obermark 1991.

12 Cf Greengus 1969: 515-518.

13 Westbrook 2003: 399.

14 Cf discussions by Westbrook ibid regarding this type of payment clause.

15 Westbrook 1991b: 90 refers to redemption as an "artificial transaction". Although a common phenomenon in ANE it is not general practice in OB (idem: 90).

16 Westbrook idem: 60.

17 Westbrook idem: 117.

18 Westbrook idem: 93-100 reflects on some possibilities how the price was fixed. Usually in an OB sales transaction a buyer wants to redeem his family estate (Westbrook idem: 90) and as the potential heir, buy back his own inheritance which was once lost by the family (idem: 60-61).

19 Cf discussions by Westbrook 2003: 395-397.

20 See, too, Claassens 2012(1): 59-62.

21 I discuss the practical application of the division in Van Wyk 2013a: 152-54 and Claassens 2012(1): 117-120.

22 Van Wyk 2013a: 152-154.

23 The length of this article does not permit a thorough discussion of the methodology. This section is only informative regarding the approach in the study of the two division texts. See, also, my discussion of the analysis-method in Van Wyk 2013b: 423-427 based on Claassens 2012(1): 107150 wherein I made a content analysis of the forty-six division texts from OB Nippur, Larsa, and Sippar and then compare the texts typologically.

24 Leemans 1986: 15.

25 Idem 15-16.

26 I discuss the reasons for a distinction between the legal notions in Claassens 2012(1): 120-121. I also elaborate on this distinction in Van Wyk 2013a: 54-59 and explain what an OB inheritance division entails and give motivations for the distinction from other seemingly similar types of divisions.

27 Claassens 2012(1): 52-62, 216-225 and Van Wyk 2013b: 423-427.

28 Claassens 2012(1): 52-62, 127, 382-385. See Claassens-van Wyk 2013: 56-89 where I outline the different factors which the family members to a Nippur division must take into account, especially the practical hardship with the application of the eldest son's greater share (firstborn share), which in Text 2 the family members include in their division. See, also, Claassens-van Wyk 2013: 67-71, 77-78 concerning the various factors the family members may consider.

29 Cf Veldhuis 1997. Claassens-van Wyk 2013: 61-62 proposes the following outcomes of training: (1) an understanding of and insight into difficult terms; (2) the ability of the scribe to record in "clear, specific and focused details" and to "sequence logically, by chronology, the event and terms of the agreements"; (3) an "understanding of the whole design of the agreement details, terms and conditions before the recording" to capture the quintessential details; and (4) the ability of "cohesion" which means "put related terms together". See, further, Van Wyk 2013a: 160-169.

30 Bottéro 1992: 19, 21 explains our limitations in understanding the content of cuneiform tablets; restricted by discovery, preservation and translation. See, also, Claassens 2012(1): 27-29, 83-89, 102-104. Westbrook 2003: 22 mentions that the cuneiform tablets are "snapshots scattered at random in time and place".

31 See Claassens 2012(1): 361-370 regarding the categories of legal practices found in city-states such as OB Larsa, Nippur, and Sippar; for instance, (1) the practical procedure for managing a division by means of a division by lots is used in OB Nippur and Larsa, and (2) a symbolic expression such as "completely divided" is used in OB Larsa and Sippar; the expression "from straw to gold" and the trustee clause occurred in OB Sippar, while the expression of equal shares is used in the division texts of OB Larsa and Sippar. See, also, Claassens idem 346-347 for an abridged comparison table of the legal practices.

32 The symbolic expression heart is satisfied demonstrates that the family members are content with the terms (Claassens 2012(1): 346). See discussions under the heading of Irregular legal practices: subheading: heart is satisfied clause, infra.

33 The equal shares clause reflects the family members' agreement in equalising the values of the divided portions of the inheritance or a part thereof. See further discussions under the heading of Irregular legal practices: subheading: equal shares clause, infra.

34 The firstborn share referred to a certain percentage of/or asset awarded to the eldest son. See discussions under the heading of Irregular legal practices; subheading: firstborn share, infra.

35 A sui generis usufruct clause reflects the brothers' lifelong commitment to maintain their priestess sister. Van Wyk 2014b: 443-483 concedes that it is not a usufruct in the strict sense. The maintenance provision "shows a unique character" against the background of social institutions' land ownership. Within the framework of a time-limited interest the ultimate owner of the nadïtu's property is the patrilineal lineage, with the father and then the sons as the representative owners (Van Wyk idem: 474). Thus, I coined the maintenance-construct as a sui generis usufruct. Cf Claassens 2012(1): 384-385; Van Wyk 2014a: 195-236, esp 206. See, also, discussions under the heading of Irregular legal practices: sub-heading: sui generis usufruct, infra.

36 Claassens 2012(1): 216-225, 423-427.

37 In AHw 1533-1534 the terms zittu(m), and zīzātu(m) are "Anteil" or "Teil", and in AHw 15171519 the term zâzu(m) is translated as "Teilen", "Verteilen" or "Anteil nehmen". This term derives from zīsu (zēzu), an adjective which means undivided (held in shared ownership), also ziztu or zâzu which translates as: divided the shares, in CAD Z, 149, 446 regarding zâzu(m).

38 See PSD online http://psd.museum.upenn.edu/epsd/nepsd-frame.html [cited 24 Feb 2014] the inheritance portion (share) clause: hala. Ibid: the root word, hal, means divide.

39 Ellis 1974: 133-153.

40 Idem 144.

41 Idem 144 n 18.

42 Idem 145.

43 In northern Mesopotamia the cloistered nadiätu of Šamaš living in the gagûm of Sippar; while in southern Mesopotamia the cloistered nadiätu of Ninurta from Nippur lived in the "place of the nadiätu" (Harris 1975: 315, 325 n 36, 317-318). The cloistered nadiätu groups were unmarried priestesses, forbidden to have children. The nadiätu were from the "upper strata of society", coming from the powerful, rich and even royal families. It was a position of prestige and also provided the opportunity for the family to advance their position in society, both socially and economically. Cf Harris 1975: 307, 315-317; Stone 1982: 62; and Van Wyk 2015: 95-122.

44 Idem 144-145.

45 In the article I explain the inclusion of the maintenance term for the naditu (priestess) with references from LH, the inheritance settlements and divisions. I argue that by implication a kinship relationship is present in cases of a priestess-sister's maintenance, coined as a sui generis usufruct. See also my discussion under the subheading "sui generis usufruct" infra and n 34 supra.

46 Ellis 1974: 144-145.

47 Ibid.

48 Cf Van Wyk 2013b: 421 illustrating a prototype of an inheritance division.

49 Idem 144.

50 Van Wyk 2013a: 152-154.

51 Idem 160-163.

52 See Stone 1982: 56.

53 Van Wyk 2015: 95-122.

54 Cf Sippar divisions in Van Wyk 2013c: 302-342; Claassens 2012(1): 384-385; Van Wyk 2014a: 195-236, and esp 206; Van Wyk 2015: 95-122.

55 Veldhuis 1997: 83 refers to the Nippur scribal schools which follow the tradition of an "overdose of highbrow Sumerian". Claassens-van Wyk 2013: 62 shows that in the Nippur scribal tradition recording was done "neatly" in descriptive detail concerning the family members' names, status, birth order, comprehensive description of the assets, special legal terms, etc.

56 Claassens 2012(1): 233-235, 273-275, 287, 372 and 403-405. See, also, Claassens-van Wyk 2013: 80 regarding the "strict disciplined Nippur scribal school tradition".

57 Cf Westbrook 2003: 373-374. Text E [IM 52590] from OB Tell Harmal was a settlement of a dispute concerning an initial division's awards. The witnesses' testimonials were accepted as proof of the division's awards (Ellis 1974: 133-153).

58 /3sar is 24 square metres. Cf 1 sar = 36 square metres: cf Potts 1997: 80.

59 In CAD Z, 449 the Akkadian variants for the Akkadian term zitti is given as zittu(m)/zizätu(m)/ zinätu, which means share: denoting a division of the portion of the estate, division of other assets, the division, or a total division. See, also, CAD Z, 139, 146, 147 discussions of the Akkadian term zittu (under headings 1 and 4) and my discussion of the term in Claassens 2012(1): 158-159.

60 Van Wyk 2013a: 152-154.

61 Each portion of the house is twenty four square metres, ie 2/3 sar awarded to each of the two brothers. One sar is thirty six square metres. Cf Potts 1997: 80.

62 Ellis 1974: 139 opines that the text has an anomaly due to its word structure in line 12 - "their sons" and "his field" - which makes it difficult to establish whose estate it is and what the capacity of the contractual parties is. Either the division is a dissolution of partnership or a division of an inheritance. Ellis discusses the possible meaning of the line, mentioning that the sentence structure is "awkward". Ellis ibid is of the opinion that the verb is not in the present, and that the syntactic emphasis of ma-la ib-[ba-aš-šu-ú] refers to "their sons" rather than "his field" and thus concludes that the field is communally held until the third generation. Consequently, the family members who contract to a present division wish to ensure that the divided property remains in the family and include in the contract that each of their sons, however many there are, will inherit the divided paternal estate - probably at the time of death of each contractual party - who are all brothers.

63 Ellis idem: 139 translated the term as a "double share".

64 The no-claim clause occurred in ninety per cent of ten chosen texts from OB Larsa, as shown in Table 24 of Claassens 2012(2): 431. In OB Nippur the no-claim clause was present in fifty per cent of the ten chosen texts, as reflected in Table 25 (at 433) in the same source.

65 Claassens 2012(1): 182-184, 364-365, 380 and 402.

66 See Claassens idem: 184-186; 2012(2): 431-438 regarding those oath clauses found in the divisions from OB Larsa, Nippur and Sippar.

67 Magnetti 1979: 8, 22, 28; Westbrook 2003: 373-374.

68 See Claassens 2012(1): 184-186; Claassens 2012(2): 431-438 regarding those witnesses' clauses found in the divisions from OB Larsa, Nippur and Sippar.

69 See PSD online http://psd.museum.upenn.edu/epsd/nepsd-frame.html (cited 24 Feb 2014).

70 Veenhof2003: 147. The witnesses are thus actively involved in the application of the performance of legal traditions in the division communally shared assets into sole ownership. See, also, Claassens 2012(1): 87 n 94. Cf Westbrook 2003: 374.

71 Ellis 1974: 148-149 translates and briefly discusses the settlement (shown as "Text E") as follows: "They asked Ilsu-ibbisu, his brother, and anyone (?) (else) in the gate of Belgaser for his knowledge, and as before the field is divided equally. They will not go back. Ipqusa, son of Igmil-Sin, will not proceed against Ilsu-nasir for the field which is his share. And Ilsu-nasir will not proceed against Ipqusa for the field which is his share. Oath: Tispak and Ibal-pi-el. Should a claimant sue, he will pay five minas of silver. (Witnesses, mostly destroyed.) [sic]".

72 See the discussion by Ellis idem: 145 regarding Text 2's witnesses.

73 The term translates as an instructor, overseer and foreman. PSD online http://psd.museum.upenn.edu/epsd/nepsd-frame.html (cited 24 Feb 2014).

74 Ibid zadim/za-dim2 is translated as a stone-cutter or bow-maker.

75 Ibid.

76 Ibid: the term translates as (to be) big, great; (to be) retired, former; (to be) mature (of male animals).

77 CAD S, Part 1, 175 the sakkanakka is a governor or high official and in Sumerian the equivalent was a gir-nita. Ellis 1974: 145 surmises that the house and orchard property mentioned in Text 2 must have been in the towns Zaralulu and Atasum and that is the reason why the officials of those towns, the sakkanakka, acted as witnesses.

78 Charpin 2010b: 42.

79 Cf Malul 1988; see, too, Hibbits 1992: 873-960.

80 Cf Claassens 2012(2): 435-438, Table 26, which is a comparison of twenty-six chosen divisions from OB Sippar and shows that thirty seven per cent of the chosen OB Sippar texts contain the heart is satisfied-clause.

81 This expression occurs, among others, in a sale, a named settlement of litigation (including a division of inheritance to form part of this group), and a receipt of a bride price (Westbrook 1991a: 219-224 esp at 219).

82 Westbrook idem 244.

83 Westbrook ibid considers the expression prima facie as "utterly superfluous". He continues by explaining his remark that the expression "is unnecessary both as a receipt (since it frequently follows an express statement that the receiver has been paid) and as a quitclaim (since it frequently precedes an express statement that no claims may be made)".

84 See discussions by Westbrook idem 219-224.

85 The equal shares-clause is mainly found in texts from OB Larsa, and in one text from OB Sippar. My comparative study of ten chosen OB Larsa division texts showed that sixty per cent of the texts contain the equal shares-clause; see Table 26 in Claassens 2012(2): 435-438.

86 Claassens-van Wyk 2013: 67-75 considers the equal shares-clause together with the casting of lots as a practice to assist in the precise division of the communally shared inheritance.

87 The term mithäris is defined in CAD M Part 2, 132, under heading 1, as "each one of two or more persons, objects etcetera, enumerated to the same extent or degree". Concerning mi-it-hä-ri-is izuzzu, in LH 165 the context of the text reads ina makkür bit abim mi-it-hä-ri-is izuzzu that may be translated as "they (the brothers) take equal shares of the possessions of the paternal estate".

88 See, also, Table 26 in Claassens 2012(2): 435-438 in the chosen study of 10 OB Nippur divisions, in seventy per cent of the texts the firstborn share was awarded to the eldest son; however, no firstborn share was found in the OB Sippar texts and in only one of the ten chosen OB Larsa texts.

89 Claassens idem: 176-179, 186-192: the use of the terms glsbansur and/or zaggulá and/or síb-ta read together with mu-nam-ses-gal-sè. Claassens-van Wyk 2013: 67-75 considers it as a practice to assist in the precise division of the communally shared inheritance.

90 Van Wyk 2014a: 223-227. In Claassens 2012(1): 378-379 only in some OB Sippar texts and in none of the chosen texts from OB Nippur is a sui generis usufruct construction found in the divisions. Cf also Van Wyk 2014b: 443-483.

91 Although in the texts we may interpret that the naditu of Šamaš holds a greater economic freedom than her Nippur counterpart, all the groups of nadiätu, especially the cloistered nadiätu, in many instances depend on their male family members for support: "There was a thin line between her dependency and presumed independency" (Van Wyk 2015: 117).

92 In Postgate 1992: 98 the priestess states her wish to appeal to judges because her brothers do not maintain her. Another example is a court case noted in King Hammurabi's letter to his successor, King Samsuilina, in Charpin 2013: 156-57. This decision contributes to LH 180-181 and illustrates the social norms and obligations of the family members to maintain their priestess-sister in such a way that she can financially afford to enter the cloister.

93 Greengus 2001: 257-267 mentioned a court case from OB Sippar, MHET 2, 4, 459. The court decided that the bare-dominium owners should forfeit their ownership because they forsook their duty to support the priestess family member.

94 Van Wyk: 2013a: 302-342 discusses three divisions reflecting a sui generis usufruct of a priestess-sister. CfVan Wyk 2014a: 223-227; Claassens 2012(1): 378-379; Van Wyk 2014b: 443-483.

95 Mina is a unit of weight. The Akkadian variant is manû and translates as mina, which is circa 480 grams. See Powell 1996: 224-242; 1989-1990: 457-517. There is an ongoing debate regarding the value and usage of the different commodities in ANE through time and place. Cf Renger 1994: 157-208; Jursa 2010: 96.

96 Normally the bringing-in or sale or buying of an asset can include something of monetary value such as silver, or a physical asset such as a slave or part of a house. The receiver of the awarded portion uses his or her personal asset/s, money or goods to purchase such portion to equalise the division of the shares; denoted by the búr-clause. In Sjöberg 1984: 91, 193-194 búr as a verb under the heading E, no 4 denotes "to pay in exchange; to compensate". In the OB period, it occurs in "OB exchange and partition texts" (idem 193). See discussions by Claassens-van Wyk 2013: 72-73 where the contractual parties utilised the búr-clause in their attempt to "equalise" the division of the awarded inheritance-shares in "exact portions".

97 As previously discussed, an extended family is defined as a group of nuclear families with a common ancestor connecting all the descendants (second and third instances). Within the group the family members bind themselves and each other by contract or obligations. Cf Leemans 1986: 15-16.

98 Ellis 1974: 133-153 translates the text as follows: "Apil-kubi, Erib-Sin, Sin-ippasram, Šamaš-bel-ili, Irra-imitti and Silli-Adad, the sons of Adad-rabi, have divided the property of their paternal estate. /3sar house property ... and 5 (or 6) gur barley are the share of Apil-kubi; [/3s]ar house property and [ ...] are the share of Erib-Sin; /3sar house property and 5 sheep the share of Sin-ippasram; /3sar house property and 5 sheep the share of Šamaš-bel-ili; /3sar house property and 5 sheep the share of Irra-imitti; /3sar house property and 5 sheep the share of Silli-Adad. They are divided; their hearts are satisfied. One will not raise a claim against another; a claimant who claims (will transgress) the oath by Tispak and Ibal-pi-el [sic]".

99 Text C of Ellis 1974 refers: Ellis idem: 140-142 translates and briefly discusses Text C's discrepancies and differences of this division. It is an elementary recording; we can only ascertain that the estate belonged to the deceased father, who is named, and whose "total available estate" assets are divided between his sons. A long oath clause follows the elementary recording. The translation at idem 141 is: "The sons of Puzur-nunu have divided the total available estate, and are mutually satisfied. He will not return. One will not raise claims against another. They mutually swore oaths by the gods Belgaser, Ahu'a and Amurru (witnesses) [sic]".

100 Ellis idem: 148 divided the four texts into two main groups. Texts C and D (Text 2 of the article) were regarded as "the completion of the legal act of division". However, the scribe did not record the agreement's specific terms in detail. The second group A and B (Text 1 of the article) were "deeds of a sort" wherein the scribe listed in detail the awarded shares observation. In addition, there is a distinct difference in the manner of the details of the recording of the terms of the divisions. Text A is a descriptive recording outlining the more exact portions of the inheritance, while Text C is only a protocol, a statement that the estate is divided. This is also the case with Texts 1 and 2 wherein Text 1 is a more descriptive recording. However, in Texts 1 and 2 the scribe found it necessary to capture the legal practices and to mention which divided inheritance shares are subject to an equal shares clause.

101 This is unlike Ellis' texts A and C where the family members use only an exchange as a division mechanism. See Table 1 and 2 supra showing an outline of Text 1 and 2's awarded portions.

102 The latter is the case in text E [IM 52590] of Ellis 1974: 133-153.

103 In my article, provisionally titled "Inheritance feuds in the Ur-Pabilsag Archive from OB Nippur" the family members in dispute settlements opt for the reappraisal and redistribution of their originally awarded inheritances.

104 See Langdon 1912: 231. He interprets this as "strife in a family is compared to defiling a holy place with filth and calumny".

105 I assess this pre-arrangement as applicable to the OB Tell Harmal divisions containing the option of a payment clause. For some reflection (at best) and in drawing inferences from our contemporary concept of fairness and deviations from a contract, in today's common wealth law systems - eg England, Wales and Australia - certain justified grounds for breach of contract are prima facie similar to the OB Tell Harmal payment clause. These grounds are "rescission", the "just compensation principle to liquidated damage agreed terms", and the "theory of alternative contracts". Rescission means that the contractual parties agree to undo the transaction: the contract is reversed or overturned as if the initial contract had never existed. (See O'Sullivan, Elliott & Zakrzewski 2008.) The "theory of alternative contracts" means that the agreement does not reflect specific damages, but rather an alternative contract in cases of deviation from the agreement's terms. See Goetz & Scott 1977: 576-578. However, in the Tell Harmal payment clause of Texts 1 and 2, provision is made for a possible future deviation or alteration from the initial contract because there is a certain amount included which I construed as a future selling price. Thus, the compensation principle to liquidated damage is prima facie more similar to the Tell Harmal payment clause. The principle is developed by contemporary courts because of "confusion between legal and moral ideas". Prima facie, there is a conflict between the contractual parties' duty to comply with the obligations of the contract and a prediction that, in the case of deviation, the breached party may by agreement been forced to overcompensate the injured party by means of an "unjust" payment. This constitutes "unjust" excessive recovery by the injured party. In such an instance, a party can also feel compelled to fulfil the obligations in an illusion of hope for compliance and to the party's excessive disadvantage for fear of the payment of an excessive payment (idem 558 n 20).

106 Cf Claassens 2012(1): 126-128, 175.

107 Ellis 1974: 133-153.

108 Transliteration and translation by Ellis 1974: 136-137 as Text B. My translation is in parentheses. See Ellis idem: 150 the plate of the transcription: [IM 52599=B].

109 See Werr 1978: 62-64 regarding the text impression ofthe cylinder seal's envelope. The impression contains an enthroned god who holds a ring and rod and rests his feet on a serpent or dragon. A goddess appears in front of the god and leads a worshipper, possibly a king, by the hand. In the sky is a sun disc in crescent and a star. The manner of excecution of the seal is according to Werr "alien to the Diyala region" because normally the face of the deity is in a profile position and the crown is in full view. Although Werr considers the tablet's origin from the Upper Euphrates in the vicinity of Mari, he agrees with Ellis ibid that Tispak-Gamil is the owner of the tablets and from the Diyala region.

110 Transliteration and translation by Ellis idem: 142-143 as Text D. My translation is in parentheses. See Ellis idem: 152 - the plate of the tablet [ IM 52624: D].

ADDENDUM TEXTS