Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Fundamina

On-line version ISSN 2411-7870

Print version ISSN 1021-545X

Fundamina (Pretoria) vol.24 n.1 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2411-7870/2018/v24n1a6

ARTICLE

Judge John Holland and the Vice-Admiralty Court of the Cape of Good Hope, 1797-1803: Some introductory and biographical notes (Part2)*

JP van Niekerk

Professor, Department of Mercantile Law, School of Law, University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

A British Vice-Admiralty Court operated at the Cape of Good Hope from 1797 until 1803. It determined both Prize causes and (a few) Instance causes. This Court, headed by a single judge, should be distinguished from the ad hoc Piracy Court -comprised of seven members of which the Admiralty judge was one, and which sat twice during this period - and also from the occasional naval courts martial which were called at the Cape. The Vice-Admiralty Court's Judge, John Holland, and its main officials and practitioners were sent out from Britain.

Keywords: Vice-Admiralty Court; Cape of Good Hope; First British Occupation of the Cape; jurisdiction; Piracy Court; naval courts martial; Judge John Holland; other officials, practitioners and support staff of the Vice-Admiralty Court

4 The personnel of the Cape Vice-Admiralty Court

The Vice-Admiralty Court at the Cape was staffed by a single judge, who, assisted by a registrar and his deputy, as well as a marshal, was in charge of its proceedings. Prosecutions were brought by the King's proctor, and practitioners (advocates and proctors138) appeared before it. It is to these and other officials that the spotlight will now turn.139

4 1 Judge John Holland

With the creation of a Vice-Admiralty Court at the Cape of Good Hope in January 1797, John Holland was appointed by Letters Patent, under the Great Seal of the High Court of Admiralty, to be its first and sole judge.140

Little is known of his early life. There is mention of a John Holland, probably our man, born in 1757 (other sources have 1758), "of Old Bailey", who was a lawyer in London in the 1770s and 1780s141 and it is known that his father and one of his brothers - he was the third son - were architects.142 In any event, John Holland arrived at the Cape on board the Belvedere more than a year later, on 3 February 1798, accompanied by his wife Catherine, née Eden.143 His arrival, according to Lady Anne Barnard, had been "anxiously expected for some time past" as he was "to Judge on prizes in their nature doubtful". Holland, she continued, "seemed surprized that anyone should [have] looked for him with anxiety as he had supposed he should be quite an idle man, the more he has to do the better".144

Holland's salary as Admiralty judge was fixed at £600 per annum.145 In addition, he was entitled to supplement his salary by what was called the "fees of office", a share in all fines levied and penalties imposed by his Court, an entitlement comparable at the time to that of the fiscal of the Court of Justice. However, the basic salary too had to be paid out of the penalties, fines and forfeitures generated in the colony by the seizure of enemy property and contraband, as had been envisaged in the Order-inCouncil establishing his Court. Although London clearly thought that there would be sufficient funds from that source,146 Holland soon complained about his salary. That gave rise to slightly acrimonious correspondence between himself and the Governor and to repercussions between the latter and London.

On 22 February 1798, Governor Macartney wrote to Secretary of State Henry Dundas in London147 to inform him that the funds generated locally would fall far short of providing Holland with his approved salary and would necessitate the deficiency being paid out by the Treasury, as envisaged in his appointment, something that would subject the Judge "to very great inconvenience, uncertainty, and delay". Macartney suggested, though, that, unless it be decided to pay it fully from the Treasury, it would be simpler to pay his whole salary out of the general local revenue (rather than supplementing it by way of a percentage of the "penalties and seizures"), especially as he did not envisage "that so many seizures are likely to occur in future as ... would produce the £600 intended as a provision for the Judge of the Court of Vice Admiralty's salary".

In March 1798, no doubt in response to the salary issue, Governor Macartney, in formally re-establishing the post office, also appointed "John Holland Esquire ... to superintend the duties thereof as Postmaster-General".148 His office was in the Castle, where two clerks assisted him. The position brought him an annual revenue of around £400,149 the entitlement to which ran from the beginning of 1797, because, as Macartney explained to London, at that time "his appointment of Judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court commenced and he was ready to have proceeded to his destination, but was only prevented by a disappointment in the ship on board of which he had hoped to take his passage".150

In October 1798, the matter of Holland's salary came up again. Macartney wrote to him,151 enquiring whether there was any surplus of fees generated by the Court (and which had to be accounted for and paid over to the Receiver General). Holland replied152 that "no Fees to the Judge have yet been received for business done by virtue of that Commission [the one by which he was appointed], but they shall regularly be accounted for as they are". He continued by pointing out that in his view there was "a solid distinction on the question of Fees" between those received for business done in the Instance Court, in respect of which there was a restriction in the standing Commission appointing him as Judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court on his entitlement so that a surplus should be paid over, and those received for business done in the Prize Court, by virtue of a separate Prize Commission of appointment in which there was no such restriction and hence no need for any accounting. In fact, he had obtained "a professional opinion" on the matter from no less eminent an Admiralty lawyer than Sir William Scott.153 Based on that opinion, Holland continued, "I have considered the Fees received in Prize Causes as applicable to my own use". He concluded by observing "that an increase of Salary, even tho' it were inferior to the Emolument arising from Fees, would be far more agreeable ... than a continuance of the receipt of them, as it excludes the possibility of a sinister motive being imputable to an Officer in my situation acting in the discharge of his Public duty". Macartney then informed Dundas of this correspondence.154

Although instructions in 1797 had stopped the practice of adding to the fixed salaries of colonial officials with fees or other similar additional supplements,155 that did not apply to Holland as Judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court, "who has received permission to take the usual fees as part of the salary of that Office".156 Further developments in 1802 caused Holland to be restricted to his fixed salary and to lose the traditional additions to his salary in the form of fees of his office derived from receiving a portion of all fees levied and fines imposed by his Court.157

Apart from the issue of his salary, Holland also took up the quill to write to Henry Dundas about other matters coming to his attention as Judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court.

In January 1799 he raised observations "made in a leisure hour and solely with a view to public good" on the issue of the protection of the trade interests of the East India Company and the apparent lack of authority of the Vice-Admiralty Court under applicable legislation to act against infringements of its monopoly by British citizens operating under the guise of neutral ships.158

A short while later, in April of the same year, he wrote about what he termed a "difference of sentiment" between himself and the Governor on the matter of the Angélique which had been brought before his Court as a prize for adjudication, but where the government had "opposed the execution of the decrees of the Vice Admiralty Court", requiring the landing and sale of her cargo pending litigation to prevent its perishment.159

As to details of Holland's residence at the Cape, one is largely and fortuitously reliant on Lady Anne Barnard.160 She and her husband, Colonial Secretary Andrew Barnard, frequently dined with Mr Hollande (as she tends to refer to him) and his wife.161 She described him as "a man who was pleasant, almost handsome, though somewhat of the old Beau, rather clever but of a spirit too encroaching for influence",162 and as an "upright judge", kindly,163 but in "bad health"164 and frequently argumentative because of asthma.165 I can also attest that Judge Holland had a particularly bad and illegible handwriting.166

Lady Anne's favourable opinion of Judge Holland was despite evidence of a fairly uneasy relationship between Holland and her husband's boss, the Governor, as well as other senior officials.167 A little more than a year after his arrival she wrote168 that she was beginning "to like him better than almost any man in the Cape, he is frank, says what he feels, without management or without fear of its being repeated & never shall it be repeated ... he really does not appear to me to be a bit wrong in any of the disputes or rather misunderstandings between him & Genl Dundas or Mr Ross". But whatever the relationship between Holland and the other British officials, he, and other members of his Court, were nevertheless clearly loyal to the Crown and the British cause.169

Although Lady Anne Barnard thought that Holland sought to influence her husband - she at one time feared that her husband was on occasion somewhat swayed by Holland, "who is not a temperate adviser"170 - she realised that there was no danger of that "as he saw it too".171

But while Lady Anne Barnard was quite well disposed towards the Judge, she was less taken by his wife, describing her, at least initially, as less agreeable and companionable than her husband,172 with manners that left much to be desired.173Although she later somewhat revised her opinion,174 this was not to last, mainly because of Mrs Holland's rather public infatuation with Major Peter Abercrombie,175which caused the Judge some embarrassment176 and raised the suspicion of his having been made a cuckold of. This is supported, if not quite proved, by another incident involving the Hollands' French cook.177

At one stage, the Hollands resided outside of town, some ten minutes' walk from the centre. They were no doubt quite disappointed that there was not room for them in the Castle, as there was for the Barnards.178 In November 1800, Holland advertised the property, proposing to exchange it "on equitable terms" for a house in Cape Town or to sell it by private contract.179 An arrangement was then made with one Carel Bester, by which the latter bought Holland's property and in exchange for which Holland bought Bester's property in town.180 This house was situated at 47 Breede Street on the corner with Hout Street, between the properties of messrs Hermans and Hofmeyer,181 and close to the Barnards.182 Ironically, it seems, the house Holland bought may have been one he had lived in before.183

But the Hollands' sojourn at the Cape was not to last. With the approaching return of the Cape to the Dutch and the resulting closure of the Vice-Admiralty Court, Judge Holland and his wife departed from the colony in September 1802. As we will see, most of his colleagues, with a few notable exceptions,184 left the Cape around the same time. The house he had acquired was probably sold, as were the slaves he, like so many other Cape Town residents, possessed.185

The Hollands returned to England, but a little time later John Holland was appointed and took up the position of Chief Justice186 of the Vice-Admiralty Court in Jamaica.187 The Vice-Admiralty Court there, sitting either in Kingston or in Spanish Town, was the oldest such court in the British colonies, having been established in 1662.188 Like colonial Admiralty courts elsewhere, it heard both ordinary, Instance causes and, in time of war, Prize causes.189

The Hollands arrived on Jamaica in late 1803.190 As with the Cape, the main source of information about their stay on the island is the journal of a diarist, this time Lady Maria Nugent, the wife of the Governor, George Nugent.191

On 29 November 1803 she wrote that she had received several high-ranking visitors, "[a]mongst them was Mr Holland, just arrived as judge of the Admiralty". With him was his wife, formerly a Miss Eden, and, Lady Maria hoped, she would "be an acquisition to our society". The Hollands stayed for dinner and Lady Maria wrote that she and her husband "both like Mr Holland's manner much".192

As at the Cape, Holland proved a rather sociable dinner companion. A few days later, on 3 December, Lady Maria wrote that at a large dinner party "Mr Holland drank so many bumpers of claret, that he got into high spirits, and gave up, in the Court of Admiralty, every point of which he had been so tenacious in the morning".193

Sadly, Holland's tenure was cut short a few weeks later. On 12 January 1804, Lady Maria diarised the news of Holland's sudden death, "which shocked us very much".194 He was buried in the St Andrew's Parish Church on the island, where the inscription on the commemorative white marble mural reads:

SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF

JOHN HOLLAND, ESQR.,

JUDGE OF

THE VICE-ADMIRALTY COURT IN JAMAICA.

HE DIED ON THE 12th OF JANUARY 1804,

IN THE 47th YEAR OF HIS AGE.195

Holland's quickly appointed successor196 became one of the most illustrious of all colonial Vice-Admiralty judges: he was Henry John Hinchliffe, Judge of the Jamaican Vice-Admiralty Court from 1804 to 1812 and again from 1814 to 1818. He is today remembered, in appropriate circles, as the author of Some Rules of Practice for the Vice-Admiralty Court of Jamaica Established [the rules] January, 5 1805, which was published in London in 1813.197

Mrs Catherine Holland,198 unsurprisingly true to the picture Lady Anne Barnard had painted of her, married one George Simpson in London in March 1805, a little more than a year after her husband's death.199

4 2 Registrar John Harrison

Second in importance after Judge Holland at the Cape Vice-Admiralty Court, but of whom almost nothing certain is unfortunately known,200 was John Harrison, who was appointed the Court's registrar (often also called its register) in January 1797.

The registrar, like the Court's marshal, was appointed by Letters Patent, under the Seal of the Admiralty, or by the Governor when there was no Admiralty appointment. The registrar was authorised to act by deputy, sharing the profits, or to act in person. As the keeper, in its registry, of the records of and created by the Court, the registrar attended the Court's sittings and was often present in the judge's chambers, drew up and signed Court documents, controlled the moneys received or expended by the Court, and taxed costs.

According to one genealogical source,201 John Harrison was born on 20 November 1757 in Stantonbury in England, and married Irene Pearce on 11 September 1787, a marriage which produced no children. Before being appointed as registrar of the Cape Vice-Admiralty Court, he apparently served in the Commission of Peace for the Liberty and Borough of St Albans, was then also an alderman from 1788, and twice the mayor of that borough in 1789 and again in 1796,202 and, possibly, sometime one of the Commissioners for the Victualling of the Navy.203 Whether Harrison ever came to the Cape and, if so, when he left, is not clear204 and the date of his death is likewise uncertain.205

One possible explanation for the dearth of information on Harrison's activities at the Cape is that, as he was entitled to do, he performed his duties through a deputy, and that he never actually came to the Cape. If so - and the appointment of a deputy registrar gives credence to this possibility - he was certainly not the last of the Court's registrars to exercise his office in this manner.206

4 3 Deputy registrar Rouviere

BG Rouviere207 was the Vice-Admiralty Court's deputy registrar and is also listed as its actuary208 and later also as its examiner, although Rouviere and Judge Holland disagreed on what exactly his rights and duties in the latter capacity entailed.209

He was appointed as deputy registrar and actuary of the Vice-Admiralty Court in November 1800 in the place of Thomas Wittenoom.210 There are many notices in the Cape Town Gazette during the period from 1800 to 1802, placed by "BG Rouviere, actuary", acting on behalf of the Court's registry and on the order of its judge, giving notice of when the "regular" Court of Vice-Admiralty or, less frequently, the "special" Court of Vice-Admiralty would be held.211 There are also notices in his name involving the expenses of the Vice-Admiralty office, or calling for persons willing to supply the Court with government bills upon England to submit tenders to the registry as to the terms on which they were willing to do so.212

Rouviere was also appointed as registrar of the Piracy Court in March 1801 when the initially appointed one, George Rex, had to beg off because of his clashing duties as marshal of the Vice-Admiralty Court.213 In that capacity, Rouviere had some difficulty in getting the government to meet the Court's expenses.214

Lady Anne Barnard was sufficiently shocked to diarise that "Mr Rouverie", as she called him, had arrived at the Barnards uninvited during dinner on 1 May 1800, but the relationship was not, as a result, permanently strained, for on 19 October she invited him and others, including the Hollands, to spend a few days with them.215

What exactly Rouviere did when the Cape Vice-Admiralty Court was closed in 1803, is not known, but he - and Wittenoom - surfaced in Malta as proctors practising before the local Vice-Admiralty Court there from around 1810216 and possibly earlier.217 On the island, Rouviere had a reputation as a prodigious imbiber of alcohol.218

The Maltese Vice-Admiralty Court was established in June 1803,219 and is famous for its connection to the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge220 and most infamous for the attacks of corruption, bribery and outrageous fees - detrimental to the interests of naval captors - levelled against it in, and outside, the British Parliament by the controversial naval officer, Thomas Cochrane, in 1810 and 1811.221

Only faint and inconclusive traces have been uncovered of what could be Rouviere's earlier222 and later223 life in England.

4 4 Marshall George Rex

George Rex was marshal of the Cape Vice-Admiralty Court from 1797 to 1802.224

4 5 King's proctor, deputy registrar and practitioner Thomas Wittenoom

One of the more interesting Admiralty lawyers at the Cape during the First British Occupation was Thomas Wittenoom.225 He was born in London in 1759, the son of Cornelius Wittenoom - a vinegar maker of St Leonard, Shoreditch, himself the son of a Dutch immigrant - and his wife Elizabeth.226 Thomas qualified himself as a civil lawyer, and practised as a proctor in the Ecclesiastical and Admiralty courts in Doctors' Commons in London.227 For some time, Wittenoom practised in partnership with Philip (de) Crespigny and his son228 until a dispute between them ended in litigation and the termination of the partnership in 1792.229

Thomas Wittenoom arrived at the Cape in February 1798, on the same ship as Judge Holland230 and, as a proctor entitled to practise in the Vice-Admiralty Court, he was at first appointed as the registrar and actuary of the Court. In that capacity he dispensed - was compelled to dispense - with the services of proctor Pontardent after he, because of his involvement in the Jessup affair,231 had been banished from the colony.

There are several archival items giving further information on Wittenoom's tenure and duties as registrar,232 and on correspondence to and from him in his official capacity.233 In November 1800, he was succeeded in that position by BG Rouviere, but continued to act in the Court not only as a proctor, but also as the King's Proctor.234In the latter capacity, he also took charge of the prosecution in the Piracy Court in June 1798 in the Princess Charlotte matter,235 while in the proceedings in that Court in March 1801 in the Chesterfield matter, he acted for the defence.236 In December 1800, he further applied on behalf of the firm of Walker & Robertson for a letter of marque for their ship, the Lady Yonge, signing the application as "Advocate & Proctor for the Petitioners".237 In 1801, Wittenoom received permission to practise as a notary.238

After Wittenoom left the Cape, probably sometime in 1803, he is listed as a proctor having an office in Doctors' Commons in London,239 and he and his former colleague, Rouviere, are then mentioned as proctors practising in the Vice-Admiralty Court on the island of Malta from at least 1810.240

Where and when Wittenoom died, is still unknown.241 His will, dated January1814,242 provided that if he died in London, he wished to be buried in the parish church of St Leonard's in Shoreditch, in the family vault there, but an otherwise pleasant afternoon spent searching in the church, proved fruitless.

Thomas Wittenoom and his wife, Elizabeth Waters, had several children. The eldest son was John Wanstead Burdett Wittenoom, later to be appointed as the first clergyman in Western Australia243 and the first in a long line of influential Australian Wittenooms.244 Another son was Charles Dirck Wittenoom, an artist and journalist.245There was also a daughter, Elizabeth (or Eliza), who had accompanied the eldest son, John, to Australia.246 The death of Thomas's widow in Australia on 27 June 1846 was announced as that of "Elizabeth, relict of Thomas Wittenoom, esq. Senior Proctor of the Vice-Admiralty Court of the Cape of Good Hope and Malta".

4 6 The practitioners

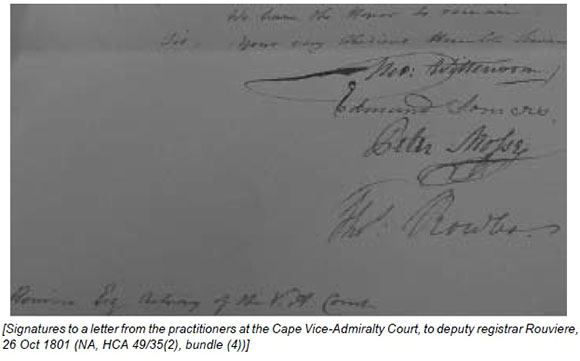

There were never many practitioners at the Cape Vice-Admiralty Court. In October 1801, for instance, there were only four - Wittenoom, Mosse, Rowles and Somers - when they collectively sent a letter to the deputy registrar, Rouviere, objecting to the possibility that the fees in Instance causes would no longer be permitted to be charged at the same rate as those in Prize causes.247

Peter Mosse was an Irishman who had been a Protestant clergyman and then became a Catholic priest, but was too fond of horse-racing and other expensive pleasures and in consequence had to quit his home country. He came to the Cape where he made a livelihood by keeping a coffee-house and a billiard table in town. Later he was appointed as a clerk in the Colonial Secretary's office, and from there he rose to the practice of law, appearing as counsel in the Vice-Admiralty Court.248 He is listed as an advocate in the Vice-Admiralty Court from 1800,249 but may have been practicing before then.250

After he commenced practising in the Vice-Admiralty Court, Mosse continued acting as prize agent for the captors of prizes as he had done before;251 occasionally he acted as an examiner (of witnesses on behalf) of the Court.252 He also defended the accused before the Piracy Court in the Princess Charlotte matter in 1798.253

He was apparently on good terms with Judge Holland to whom he sold a slave in 1798.254

However, Mosse, who retained his fondness for horse racing and gambling,255became involved in the Jessup affair, which Lady Anne Barnard256 referred to as "another Strange Higgleday Piggleday business going on" and which her husband257called "another strange piece of Business". The upshot of the affair was that the inspector of customs, Henry James Jessup, who had opposed an order from Governor Yonge,258 and who further did not endear himself to the Governor by sarcastically commenting on the latter's accompanying proclamation,259 was simply suspended until the Crown's pleasure was known and ultimately did not leave the colony until 1803.260 Mosse - as well as proctor Pontardent261 - though, was banished from the Cape in April 1800, because the legal opinion he had given Jessup on the legality of Yonge's order and proclamation was considered improper and inflammatory.

Although Yonge was right and Jessup, and by association Mosse, wrong,262 there was a feeling that for all his faults263 Mosse's punishment was somewhat harsh; he had, after all, merely - in a professional capacity - drawn a legal opinion and should not have been censured because it turned out to be wrong.264

But Yonge clearly thought differently of Mosse. In explaining the affair to Henry Dundas, he wrote that he had been informed that Mosse was "a Man of Genius many ways" and that he had been practising in the Vice Admiralty Court "where", Yonge continued, "I am sorry to say there is a very great want of able Counsel".265After Mosse had fired off several petitions concerning his banishment,266 he obtained permission early in 1801 to remain in the colony267 and seems only to have left two years later.268

Another advocate and examiner in the Vice-Admiralty Court, at least in 1801, was one Edward Somers, of whom nothing more is known.269

Better known was Thomas Rowles, likewise an advocate and examiner practising in the Vice-Admiralty Court.270

Born in Westminster, London, in 1777, he first arrived at the Cape in 1800 and was granted final permission to remain in the colony in November 1801. Although slated to take charge of the prosecution before the Piracy Court in March 1801 in the Chesterfield matter, the registrar, George Rex, informed the Court that Rowles had declared his intention to resign his appointment by reason of another professional engagement and Edward Somers was then appointed as counsel for the prosecution in his place.271

Rowles left the Cape in 1803, but he returned in 1807 as the "King's Proctor, and Agent for the Receiver General Comptroller, and Solicitor of all the Rights and Perquisites of Admiralty at the Cape of Good Hope",272 so becoming one of very few legal practitioners active in the Vice-Admiralty Court in both periods of British rule. He was in 1807 also appointed as secretary to the Court of Appeals for both Criminal and Civil Cases, a position he would hold until his death in 1826.273

On 29 December 1811, aged thirty-three, Rowles married the seventeen-year old Elisabeth Christina, the youngest daughter of the late Arend de Waal, a Company official. Three weeks later, on 19 January 1812, he became related to the Admiralty Judge at the time, George Kekewich, a widower likewise then aged thirty-three, when the latter married one of Elizabeth's older sisters, Catharina Cornelia;274 the two lawyers were witnesses at each other's weddings. On occasion Rowles would also act as Judge in the Vice-Admiralty Court in the absence of his brother-in-law, while both were active in the Court of Appeals.275

Another practitioner who, like Rowles, was active in judicial circles at the Cape during both periods of British rule, was David Pontardent.276

A descendant of a French Protestant family that had settled in London, Pontardent arrived at the Cape in 1797. He practiced as a proctor in the Vice-Admiralty Court and occasionally acted as its examiner until he, together with Mosse,277 got into trouble with Governor Yonge for his part in the Jessup affair278 and was banished from the settlement. In April 1800 Pontardent was also dismissed from his appointment as an examiner of the Vice-Admiralty Court on the instructions of Judge Holland.279Although Pontardent protested against his banishment,280 generally considered to have been even more severe in his case than in that of Mosse,281 that was to no avail.

Governor Yonge clearly did not regard him highly. In explaining the Jessup affair to Henry Dundas, Yonge wrote that he knew little of Mosse's accomplice, Pontardent, whom he did not name, apart from the fact that having "practiced as a lawyer in England", "he too practiced here as a lawyer in the Admiralty Court" and that those who know him "do not speak favourably of him".282

In April 1802, Pontardent, then in London,283 sought, on the basis of the injury he had suffered at the hands of Governor Yonge, an appointment as British consul at the Cape, now that the settlement was about to be restored to the Dutch,284 but his request seems to have been disregarded.285

Pontardent eventually arrived back in the colony in September 1806, without his wife and children.286 He resumed his practice as a proctor in the Vice-Admiralty Court287 and pursued his interests in matters botanical,288 until his intestate death in May 1825 at the age of fifty-nine.289290

4 7 The support staff

Several persons were appointed as administrative personnel in the Vice-Admiralty Court. They are no less interesting than the officials and the practitioners whom they served.

Aegidius Benedictus (AB) Ziervogel291 was the Court's sworn translator and interpreter and also at times the messenger at the Court of Justice.292

Born in Uppsala, Sweden, on 21 August 1762, the son of a well-known professor at the university there,293 he left Sweden in 1786, moved to Amsterdam to learn commerce, and emigrated to the Cape of Good Hope in August 1789. There he was joined by his elder brother, Carel Ewald, and later by his cousin, Carel Samuel Fredrikzoon Ziervogel.294

In May 1800, he married a local widow, Beatrix Auret.295 He had close personal ties with the Vice-Admiralty Court's marshal, George Rex.296 Ziervogel died in June 1818, having only in the year before gotten around to requesting citizenship of the colony.297 One of his descendants, his grandson, was the well-known Cape Judge, EB Watermeyer.298

When Scotsman William Menzies arrived at the Cape in 1827 to take up his appointment as senior puisne judge on the bench of the newly created Supreme Court, he was not the first of that name to be involved with the administration of justice at the Cape.

In February 1798, the twenty-six-year old William Menzies299 arrived here on the Belvedere, a fellow passenger of Judge Holland and proctor Wittenoom. After a brief stint in the customs office, he was appointed a clerk in the Vice-Admiralty Court's registry at an annual salary of £150.300

In April 1801, Menzies resigned from his duties at the Court and requested permission to be admitted to practise as a notary public.301 His request was turned down on the grounds of his short period of local residence.302 Further petitions followed in May and again in November 1801. Nevertheless, Menzies appears to have been active as a representative (the recipient of notarial powers of attorney) in several matters, including one involving prize agent William Proctor Smith.303Although Menzies signed an oath of submission to the Batavian government in November 1803, he gave notice in June 1805 of his intention to leave the colony.

William Menzies may have been the uncle of Judge William Menzies.304

Other clerks in the Vice-Admiralty Court during the First British Occupation were Thomas Spencer in 1797;305 William Henry Sturgis, who arrived from England in 1796 and may have been appointed in Menzies' place in 1801;306 and Joseph Ranken.307 Finally, there was the Irishman Edward Halaran, the court's messenger and crier at least from 1800 until its closure in 1803.308 Although persons are sometimes mentioned as the "vendu master of the Vice-Admiralty Court", it would appear that there was no such position; one of the several official auctioneers at the Cape merely also acted for the Court in its sales as and when required.309

5 The closure of the Vice-Admiralty Court

By the Treaty of Amiens of 27 Mar 1802,310 concluded between England and the French and Batavian republics, article VI restored the Cape of Good Hope to the Dutch as it was before the war.311 It was further agreed that "[t]he ships of every description belonging to the other Contracting Parties shall have the right to put in there, and to purchase such supplies as they may stand in need of as heretofore, without paying any other duties than those to which the Ships of the Batavian Republic are subjected".

While local institutions continued as before, British institutions closed down and ceased operations. British subjects had the option of staying on, but most returned home. Thus, although officials charged with, for example, the administration of justice, were required to continue the functions of their offices, this naturally did not apply to the Vice-Admiralty Court which was not a local, but rather a British court. The Court ceased its operations and its officers and practitioners, with a few exceptions, left the Cape.

Those who left and who, like Judge Holland, received their salaries from the civil list, were paid in advance to 30 June 1803.312

In anticipation of the end of British rule, Judge Holland wrote to London about the effect that would have on the Vice-Admiralty Court.313 He thought it would be necessary to make some provision, whether by an article in a treaty or in some other form, "for the termination of Causes pending in the Vice Admiralty Court of this Colony ... that will not in all Probability be finally determined upon previous to the Surrender of the Cape", as well as for cases then on appeal. The Court would cease to have jurisdiction unless special provision was made. The same applied to securities taken by the Court for various purposes, including for letters of marque. Finally, he assumed it would meet with governmental approval "that the Records of the Court should be transmitted to the registry of the High Court of Admiralty" and, unless instructed otherwise, he would make arrangements for that "previous to quitting the Colony".

Although nothing seems to have been arranged as regards pending cases, the matter was eventually resolved.

In The Picimento,314a Portuguese vessel was captured by a privateer in 1801 and brought for adjudication before the Cape Vice-Admiralty Court. The Court pronounced a sentence of restitution with costs and damages. The captor appealed against the sentence, but failed to prosecute the appeal in time. The Lords Commissioners of Appeal in Prize Cases then declared the appeal deserted and remitted the cause. However, before the Vice-Admiralty Court's sentence could be carried into final execution, the Cape was given up in terms of the Treaty of Amiens, the Court abolished, "and the records of the Court of Vice-Admiralty were removed, and deposited in the Registry of the High Court of Admiralty" in London. On an application that the High Court of Admiralty carry the Vice-Admiralty Court's decree into execution, the question arose whether the High Court of Admiralty had jurisdiction to interfere in a cause already determined in another court and to carry into effect the judgement of that other court.

After the Lords Commissioners had refused to give a ruling in the matter - they only had appellate jurisdiction and as they had dismissed the appeal, they could not become involved de novo - the High Court of Admiralty held that it did have a general jurisdiction sufficient to aid the process of the Cape Vice-Admiralty Court in order to prevent a total failure of justice.

As mentioned, the records of the Cape Vice-Admiralty Court were sent to London where they still reside,315 leaving only an odd assortment of documents of the first Vice-Admiralty Court in the Cape Archives.316

After the Batavian interlude, during which a Commercial Court ("Kamer van Commercie") settled commercial, including maritime, disputes,317 the British returned in January 1806 and soon re-instituted their Vice-Admiralty Court.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albertson, L "Mutiny on the Princess Charlotte, 1798" (19 Jul 2002) available at http://archiver.rootsweb.anchestry.com (accessed 4 Aug 2014) [ Links ]

Albertson, L "Princess Charlotte and confusion at the Cape" (19 Jul 2002) available at http://archiver.rootsweb.anchestry.com (accessed 4 Aug 2014) [ Links ]

Anon (1963) "The order book of captain Augustus Brine, RN, 1797-1815" Quarterly Bulletin of the SA Library 17: 75-86 and Quarterly Bulletin of the SA Library 18: 17-26 [ Links ]

Arkin, Marcus (1960) "John Company at the Cape. A History of the Agency under Pringle (17941815) Based on a Study of the 'Cape of Good Hope Factory Records'" Archives Year Book for South African History 2: 178-344 [ Links ]

Arnould (2013) Law of Marine Insurance and Average 18 ed by Jonathan Gilman, Robert Merkin, Claire Blanchard & Mark Templeman (London) [ Links ]

Barnard, Lady Anne (Letters) (1973) The Letters of Lady Anne Barnard to Henry Dundas from the Cape and Elsewhere 1793-1803 Together with Her Journal of a Tour into the Interior and Certain Other Letters ed by AM Lewin Robinson (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Barnard, Lady Anne (Journals) (1974) The Cape Journals of Lady Anne Barnard 1797-1798 ed by AM Lewin Robinson with Margaret Lenta & Dorothy Driver [1RS Second Series no 24] (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Barnard, Lady Anne (Diaries) (1799) The Cape Diaries of Lady Anne Barnard 1799-1800 vol 1 ed by Margaret Lenta & Basil le Cordeur [1RS Second Series no 29] (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Barnard, Lady Anne (Diaries) (1800) The Cape Diaries of Lady Anne Barnard 1799-1800 vol 2 ed by Margaret Lenta & Basil le Cordeur [1RS Second Series no 30] (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Blayney, Frederick (1817) A Practical Treatise of Life Annuities;... (London) [ Links ]

Böeseken, AJ (1986) Uit die Raad van Justitie 1652-1672 (Pretoria) [ Links ]

Botha, C Graham (1962a) "Cape records of the South Sea pirates" in General History and Social Life of the Cape of Good Hope [vol 1 Collected Works] (Cape Town): 42-52 [ Links ]

Botha, C Graham (1962b) "Some monumental inscriptions Cape of Good Hope" in General History and Social Life of the Cape of Good Hope [vol 1 Collected Works] (Cape Town): 70-73 [ Links ]

Botha, C Graham (1962c) "Administration of the Cape of Good Hope, 1652-1834" in General History and Social Life of the Cape of Good Hope [vol 1 Collected Works] (Cape Town): 231-244 [ Links ]

Botha, C Graham (1962d) "The Honourable Willam Menzies 1795-1850" in History of Law, Medicine and Place Names in the Cape of Good Hope [vol 2 Collected Works] (Cape Town): 1-21 [ Links ]

Botha, C Graham (1962e) "The public archives of South Africa 1652-1910" in Cape Archives and Records [vol 3 Collected Works] (Cape Town): 113-222 [ Links ]

Botha, C Graham (1962f) "Extracts from register of deaths at the Cape of Good Hope, 18161826" in Cape Archives and Records [vol 3: Collected Works] (Cape Town): 290-301 [ Links ]

Boucher, Maurice & Nigel Penn (eds) (1992) Britain at the Cape 1795 to 1803 (Houghton) [ Links ]

Bourguignon, Henry J (1987) Sir William Scott, Lord Stowell. Judge of the High Court of Admiralty, 1798-1828 (Cambridge) [ Links ]

Brenton, Edward Pelham (1837) The Naval History of Great Britain from 1783 to 1836 2 vols (London) [ Links ]

Bridges, George Wilson (1828) The Annals of Jamaica vol 1 (London) [ Links ]

Brooks, Michael Franklin (1802) Trial of the Master and Supercargo of the Merchant Ship Chesterfield Charged... with Treasonable Correspondence with the Enemies of Great Britain ... (London) [ Links ]

Butterfield, Agnes M (1938) "Notes on the records of the Supreme Court, the Chancery, and the Vice-Admiralty courts of Jamaica" Historical Research 16: 88-99 [ Links ]

Cameron, Catherine WM (1979) Frederick Francis Burdett Wittenoom, Pastoral Pioneer & Explorer 1855-1939: A Biographical Sketch (Perth) [ Links ]

Cordingly, David (2008) Cochrane the Dauntless. The Life and Adventures of Admiral Thomas Cochrane, 1775-1860 (London) [ Links ]

Cranfield, RE (1963) The Wittenoom Family in Western Australia: A Brief Account of the Lives of Members of the Wittenoom Family who left England in 1829 (place of publication not mentioned) [ Links ]

Crump, Helen J (1931) Colonial Admiralty Jurisdiction in the Seventeenth Century [No 5 Royal Empire Social Imperial Studies] (London) [ Links ]

Davey, Arthur (1988) "Naval headquarters, Table Bay, 1795-1803" CABO. Historical Society of Cape Town 4(3): 14-16 [ Links ]

De Kock, MH (1924) Selected Subjects in the Economic History of South Africa (Cape Town) [ Links ]

De Villiers, Charl Jean (1967) Die Britse Vloot aan die Kaap, 1795-1803 (MA, University of Cape Town) [ Links ]

De Villiers, Charl Jean (1969) "Die Britse Vloot aan die Kaap, 1795-1803" Archives Yearbook for SA History 32(1): 1-145 [ Links ]

De Vos, Wouter (1992) Regsgeskiedenis, met 'n Kort Algemene Inleiding tot die Regstudie (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Dictionary of South African Biography (1968-1987) 5 vols (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Dugan, James (1966) The Great Mutiny (London) [ Links ]

Dunlap, Andrew (1836) A Treatise on the Practice of Courts of Admiralty in Civil Causes of Maritime Jurisdiction ... (Philadelphia) [ Links ]

Du Plessis, Willemien, and Nic Olivier (2014) "'n Samevloei van twee regstelsels: Siviele prosesreg in die Kaapse howe: 1806-1828" in Marita Carnelley, Shannon Hoctor & André Mukheibir (eds) De Jure Gentium et Civili. Festschrift in Honour of Eltjo Schrage (e-publication, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth): 9-44 [ Links ]

Edwards, AB (1972) "A conflict of jurisdiction" Codicillus 12(1): 42-43 [ Links ]

Espinasse, Isaac (1824) A Treatise on the Law of Actions on Statutes, .... (London) [ Links ]

Eybers, GW (1918) Select Constitutional Documents Illustrating South African History 17951910 (London) [ Links ]

Fairbridge, Dorothea (1924) Lady Anne Barnard at the Cape of Good Hope 1797-1802 (Oxford) [ Links ]

Featherstone, David (2009) "Counter-insurgency, subalternity and spatial relations: Interrogating court-martial narratives of the Nore mutiny of 1797" SA Historical J 61: 766-787 [ Links ]

Feldbaek, Ole (1973) "Dutch Batavia trade via Copenhagen 1795-1807. A study of colonial trade and neutrality" Scandinavian Economic History Review 21: 43-75 [ Links ]

Freund, William M (1989) "The Cape under the transitional governments, 1795-1814" in Richard Elphick & Hermann Giliomee (eds) The Shaping of South African Society, 1652-1840 (Cape Town): 324-357 [ Links ]

F St L S (1935) "Mr Justice EB Watermeyer" SALJ 52: 135-142 [ Links ]

Gerber, Jill Louise (1998) The East India Company and Southern Africa: A Guide to the Archives of the East India Company and the Board of Control, 1600-1858 Appendix: vol 2 (D Phil thesis, University College, London) [ Links ]

Gibb, Arthur Ernst (1890) The Corporation Records of St Albans ... (St Albans) [ Links ]

Goldblatt, Robert (1984) Postmarks of the Cape of Good Hope: The Postal History and Markings of the Cape of Good Hope and Griqualand West, 1792-1910 (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Giliomee, Hermann (1975) Die Kaap tydens die Eerste Britse Bewind 1795-1803 (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Gregory, Desmond (1996) Malta, Britain, and the European Powers, 1793-1815 (Cranbury, NJ) [ Links ]

Griffiths, RJH (2002) "Navigator ... and inventor, discoverer, merchant, privateer .... The career of an eighteenth century seaman under White Ensign and Red and the tale of the discovery of two sets of 'Mortlock Islands'" Mariner's Mirror 88: 196-201, updated version available at http://www.mortlock.info/encyclopaedia/slands (accessed 1 Jun 2010) [ Links ]

Hall, John E (1809) The Practice and Jurisdiction of the Courts of Admiralty... (Baltimore) [ Links ]

Hassam, John T (1880) Notes and Queries Concerning the Hassam and Hilton Families (Boston) [ Links ]

Heese, HF (1994) Reg en Onreg: Kaapse Regspraak in die Agtiende Eeuw (Bellville) [ Links ]

Horwitz, D (1997) Disreputable Fellows: Prisoners and Graffiti from the Castle, Cape Town (honours dissertation in Archaeology, University of Cape Town) [ Links ]

Hough, Barry, and Howard Davis (2008) "Coleridge as public secretary in Malta: The surviving archives" The Coleridge Bulletin (NS) 31: 90-101 [ Links ]

Hunt, William (1796) A Collection of Cases on the Annuity Act relative to the Enrolment of Memorials (London) [ Links ]

Immelman, RFM (1955) Men of Good Hope. The Romantic Story of the Cape Town Chamber of Commerce 1804-1954 (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Jurgens, AA (1943) The Handstruck Letter Stamps of the Cape of Good Hope from 1792 to 1853 and the Postmarks from 1853 to 1910 (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Kaapse Plakkaatboek 6 vols (1944-1961) ed by MK Jeffrey (vols 1-3) and SJ Naude (vols 4-6) (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Kahn, Ellison (1976) "Sir Walter Scott and Menzies" SALJ 93: 94-95 [ Links ]

Knight, Roger (2008) "Politics and trust in victualling the Navy, 1793-1815" Mariner's Mirror 94: 133-149 [ Links ]

Laidler, PW (1939) The Growth and Government of Cape Town (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Lawrence-Archer, JH (1875) Monumental Inscriptions of the British West Indies ... (London) [ Links ]

Leach, MacEdward (1960) "Notes on American shipping based on records of the Court of Vice-Admiralty of Jamaica, 1776-1812" American Neptune 20: 44-48 [ Links ]

Leibbrandt, HCV (1905) Precis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope: Requesten (Memorials) 1715-1806 vol 1: A-E (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Linder, Adolphe (1997) Swiss at the Cape of Good Hope 1652-1971 (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Lloyd, Christopher (1947, 1998 ed) Lord Cochrance. Seaman, Radical, Liberator. A Life of Thomas, Lord Cochrane, 10th Earl of Dundonald (New York) [ Links ]

MacSymon, RM (1990) Fairbridge Ardene & Lawton. A History of a Cape Law Firm (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Marshall, Samuel (1808) A Treatise on the Law of Insurance .... 2 ed (London) [ Links ]

Moree, Perry (1998) Met Vriend die God Geleide'. Het Nederlands-Aziatisch postvervoer ten tijde van die Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (Zutphen) [ Links ]

Namier, Lewis, and John Brooke (1964) The History of Parliament: The House of Commons, 1754-1790 vol 1: Members A-J (London) [ Links ]

Nathan, Manfred (1934) "The old Cape bench and bar" SA Law Times 3: 165-166 [ Links ]

O'Brien [née Wittenoom], Jacqueline, and Pamela Statham-Drew (2009) On We Go: The Wittenoom Way: The Legacy of a Colonial Chaplain (Perth) [ Links ]

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004, various subsequent online eds) available at http://www.oxforddnb.com [ Links ]

Pama, C (1992) British Families in South Africa. Their Surnames and Origins (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Percival, Capt Robert (1804) An Account of the Cape of Good Hope ... (London) [ Links ]

Philip, Peter (1981) British Residents at the Cape 1795-1819. Biographical Records of 4800 Pioneers (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Roos, J de V (1897) "The plakaat books of the Cape" Cape LJ 14: 1-23 [ Links ]

Rosenthal, Eric (1954) "Mutiny at Simonstown" in Eric Rosenthal Cutlass and Yardarm (Cape Town): 67-75 [ Links ]

Sainty, JC (1975) Office Holders in Modern Britain. IV: Admiralty Officials 1660-1870 (London) [ Links ]

Schuhmacher, W Wilfried (1977) "Some Danish Indiamen at the Cape of Good Hope" Mariner's Mirror 63: 231-232 [ Links ]

Seth, Suman (2014) "Materialism, slavery, and The History of Jamaica" Isis. A J of the History of the Science Society 105: 764-772 [ Links ]

Smith, Herbert A (1927) "The legislative competence of the dominions" SALJ 44: 545-553 [ Links ]

SP (1933) "Long family of Jamaica" Notes & Queries 165: 339-340 [ Links ]

Spilhaus, M Whiting (1966) South Africa in the Making 1652-1806 (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Stokes, Anthony (1783) A View of the Constitution of the British Colonies in North America and the West Indies ... (London) [ Links ]

Storrar, Patricia (1974) George Rex: Death of a Legend (Johannesburg) [ Links ]

Stroud Dorothy (1966) Henry Holland: His Life and Architecture (London) [ Links ]

Styles, Michael H (2003) Captain Hogan. Sailor, Merchant, Diplomat on Six Continents (Fairfax Station, VA) [ Links ]

Taylor, Stephen (2016) Defiance. The Life and Choices of Lady Anne Barnard (London) [ Links ]

Theal, George McCall (1880) Catalogue of Documents Sept 1795-Feb 1803 in the Collection of the Colonial Archives, Cape Town (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Theal, George McCall (1895) Documents Copied by Theal (London) [ Links ]

Theal, George McCall Records of the Cape Colony (RCC) (1897-1905) 34 vols (London) [ Links ]

Ulrich, Nicole (2011) Counter Power and Colonial Rule in the Eighteenth-Century Cape of Good Hope: Belongings and Protest of the Labouring Poor (PhD thesis, University of the Witwatersrand) [ Links ]

Ulrich, Nicole (2013) "International radicalism, local solidarities: The 1797 British naval mutinies in Southern African waters" International Review of Social History 58: 61-85 [ Links ]

Van Blommestein, Joan (1998) "Lady Anne Barnard's visit to Simon's Bay 24-9-1797 and the RN Mutiny" Bulletin of the Simon's Town Historical Society 20: 53-54 [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, Petrus Johannes (1984) Regsinstellings en die Reg aan die Kaap van 1806-1834 (LLD thesis, University of Western Cape) [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, JP (1994) "Marine insurance claims in the Admiralty Court: An historical conspectus" SA Merc LJ 6: 26-62 [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, JP (2005) "The First British Occupation of the Cape of Good Hope and two prize cases on joint capture in the High Court of Admiralty" Fundamina. A Journal of Legal History 11: 155-182 [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, JP (2010) "George Rex of Knysna: A civil lawyer from England and first marshal of the Vice-Admiralty Court of the Cape of Good Hope, 1797-1802" Fundamina. A J of Legal History 16(2): 486-513 [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, JP (2015a) "Denis O'Bryen: (Nominally) second marshal of the Vice-Admiralty Court of the Cape of Good Hope, 1807-1832" Fundamina. A J of Legal History 21(1): 142184 [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, JP (2015b) "Of naval courts martial and prize claims: Some legal consequences of commodore Johnstone's secret mission to the Cape of Good Hope and the 'battle' of Saldanha Bay, 1781 (Part 1)" Fundamina. A J of Legal History 21(2): 392-456 [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, JP (2016) "Of naval courts martial and prize claims: Some legal consequences of commodore Johnstone's secret mission to the Cape of Good Hope and the 'battle' of Saldanha Bay, 1781 (Part 2)" Fundamina. A J of Legal History 22(1): 118-154 [ Links ]

Van Zyl, DH (1983) Geskiedenis van die Romeins-Hollandse Reg (Durban) [ Links ]

Visagie, GG (1969) Regspleging en Reg aan die Kaap van 1652 tot 1806, met 'n Bespreking van die Historiese Agtergrond (Cape Town) [ Links ]

Walker, Eric A (1957) A History of South Africa 3 ed (London) [ Links ]

Wells, Roger (1983) Insurrection. The British Experience 1795-1803 (Gloucester) [ Links ]

Wilkinson, Clive (2005) "The non-climatic research potential of ships' logbooks and journals" Climatic Change 73: 155-167 [ Links ]

Wright, Philip (1966) Monumental Inscriptions of Jamaica (London) [ Links ]

Wright, Philip (ed) (2004) Lady Nugent's Journal ofHer Residence in Jamaica from 1801 to 1805 4 ed (Jamaica) [ Links ]

Yonge, CD (1863) The History of the British Navy.... 2 vols (London) [ Links ]

Case law

Angelique, The (1801) 3 C Rob (App) 7, 165 ER 497

Argun, MT v Master and Crew of the MT Argun 2004 (1) SA 1 (SCA)

Atalanta, The (1808) 6 C Rob 440, 165 ER 991

Boehm & Others v Bell (1799) 8 TR 154, 101 ER 1318

Carr & Josling vMontefiore (1864) 5 B & S 408, 122 ER 883

Crespigny v Wittenoom & Another (1792) 4 TR 790, 100 ER 1304

Doe, on demise of Johnstone v Phillips (1808) 1 Taunt 356, 127 ER 871

Hood v Burlton (1792) 2 Ves Jun 29, 30 ER 507

Hope, The (23 April 1803, HL), referred to in The Atalanta (1808) 6 C Rob 440, 165 ER 991 at 456-457, 997-998

Hutton v Lewis, Clerk & Others (1794) 5 TR 639, 101 ER 356

Picimento, The (1803) 4 C Rob 360, 165 ER 640

Reward, The (1818) 2 Dods 265, 165 ER 1482

Robertson v French (1803) 4 Esp 246, 170 ER 707 (KB)

Robertson & Thomson v French (1803) 4 East 130, 102 ER 779

Umbragio Obicini v Bligh (1832) 8 Bing 335, 131 ER 423

Yeaton v Fry 5 Cranch 335, 9 US 335 (US Dist Col, 1809)

* Continued from (2017) 23(2) Fundamina 176-210.

138 In some Vice-Admiralty courts, including, it seems, the one at the Cape, advocates (the Admiralty equivalent of barristers) were also allowed to act as proctors (the Admiralty equivalent of solicitors). Admitted advocates of such courts were also on occasion appointed as surrogates to perform the ordinary or common (but no other) acts of the judge in his absence, eg, administering oaths, decreeing monitions, or taking bail.

139 For lists of those who served on or were involved with the Court, see the African Court Calendar for 1801 and for 1802.

140 See Philip 1981: 185.

141 He was admitted to Lincoln's Inn in 1773, and his name appears in the Law List for 1787 as counsel of King's Bench Walk, Inner Temple: see Ed Pope History, sv "Holland John", available at http://www.edpopehistory.co.uk (accessed 17 Aug 2015).

142 Barnard Diaries vol 1: 318 (4 Nov 1799) refers to Judge Holland being "the son of one architect & certainly the brother of one". The brother was the architect Henry Holland (1745-1806), eldest son of Henry Holland (1712-1785), who was a prosperous Georgian builder who executed much of the architectural work of the celebrated landscape gardener Lancelot (Capability) Brown. Henry jr was at first in partnership with Brown (until the latter's death in 1783), and had married the latter's elder daughter in 1773. Their collaboration resulted in several well-known buildings. He subsequently established himself independently and received several royal commissions (including Carlton House in Pall Mall, Brighton and York House in Whitehall, the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, and the Covent Garden Theatre). Brother Henry was also a collector of antiques, especially of Italian origin, and it is said in a biographical note on him that "Holland's brother John, who also spent much time in Rome, acquired further antique fragments for him": see David Watkin "Holland, Henry" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004, online ed Sep 2013, accessed 19 Aug 2015); Stroud 1966, who states at 19 that Henry's brother, John, was borne in 1757, at 29 n 2 (incorrectly) that he became "an Admiralty High Court Judge", and at 147 that John acquired some antique pieces for Henry.

143 He had married her in Nov 1790 at St George's Church, Hanover Sq: see Ed Pope History, sv "Holland John" available at http://www.edpopehistory.co.uk (accessed 17 Aug 2015).

144 Barnard Letters: 99 (letter 3 Feb 1798 to secretary of war, Henry Dundas in London).

145 By comparison, at the time the President of the Court of Justice (Olaff de Wet) received the equivalent of Rds5 000 (£1 000) p/a, and its other members between Rds1 000 (£200) and Rds500 (£100): see, further, n 154 infra. The salaries of officials sent out from England were in pounds rather than in rixdollars: Freund 1989: 345.

146 See Theal RCC vol 2: 290 (letter Henry Dundas to Governor Macartney, 28 Jun 1797, referred to in a letter by Macartney to Holland, 13 Oct 1798, in which it was stated that "in the event of any surplus of fees" in the Vice-Admiralty Court, the Judge had to account for it to the local "fee fund").

147 See Theal RCC vol 2: 240-242.

148 See the Proclamation on the Re-establishment of the Post-Office, 6 Mar 1798 (in Kaapse Plakkaatboek vol 5: 128-129). The establishment of an official postal service - for overseas mail only - at the Cape was provided for in Sep 1789 with a "post comptoir" (open from 09:00 to 10:00 daily) in the Leerdam bastion in the Castle (where it remained until 1809). The envisaged service only came into operation in Dec 1791 when Adriaan Vincent Bergh was appointed the first postmaster. Shortly after the First British Occupation, the post office resumed its service, with Bergh initially remaining in his post at a salary of £400 per annum, until the formal reorganisation in 1798. See, further, "The rise of the General Post Office in Cape Town 1792-1910" available at http://www.sahistory.org.za (accessed 3 Feb 2017); Jurgens 1943: 11-13; Goldblatt 1984: 21-27; Moree 1998: 140-141, 246.

149 See Giliomee 1975: 99; Boucher & Penn 1992: 167 n 77.

150 See Boucher & Penn 1992: 200, reproducing a private letter by Macartney to Dundas, 3 Mar 1797.

151 Theal RCC vol 2: 290 (letter Macartney to Holland, 13 Oct 1798).

152 Idem 291-293 (letter Holland to Macartney, 14 Oct 1798).

153 Scott's opinion, dated 1 Nov 1797 (attached to Holland's letter to Macartney), was that if there was no limitation on the entitlement to fees in Holland's "Prize Commission", he was not restrained from taking fees as he was by the limitation occurring in his "standing Commission as Judge of the Admiralty", which had to be understood as referring to "the Ordinary business" of his office as Judge and not "the Extraordinary business" as Judge in the (Vice-Admiralty Court sitting as) Prize Court, a business "extraordinary both in its nature and its magnitude" and one that is "usually provided for by an increase in salary or by a receipt of fees". However, Scott suggested that Holland should clarify the matter with the Lords of the Admiralty, which Holland did on 16 Mar 1798. William Scott (1745-1836), the brother of John Scott, Lord Eldon (Lord Chancellor 18011806 and 1807-1827), was King's Advocate 1788-1789, Judge of the Admiralty Court 1798-1828, knighted in 1788, and created Lord Stowell in 1821. On Scott, see Bourguignon 1987.

154 See Theal RCC vol 2: 293-295 (letter 15 Oct 1798, attaching Holland's letter and Scott's opinion; the letter also contains a list of the principal officers of government in the colony with their salaries: Holland received £400 as Postmaster General and £600 (Rds3 000) as Judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court; the salary of Olaff Wet, President of the Court of Justice, was Rds5 000 (£1 000) and members of that Court received Rds1 000 (£200) each; the latter salaries were increased by Rds500 in Dec 1798 for those members appointed to superintend the issue of new paper money at the Cape. See, also, Theal RCC vol 2: 309-311 (letter War Office to Macartney, 15 Dec 1798).

155 See Theal RCC vol 2: 35 (letter War Office to Macartney, 7 Jan 1797, informing that fees and perquisites received by public offices in the colony should not belong to the person(s) employed in those offices, but should be appropriated to the payment of the salaries of such appointees). Thus, fixed salaries could no longer be supplemented with fees: see Freund 1989: 345, pointing out that in 1797 Britain raised official salaries and created some where none had existed before, and also, in an attempt to curb corruption, suppressed certain perquisites which formerly had been the principal income of officials.

156 See Theal RCC vol 2: 433-434 (letter War Office to Governor Yonge, 30 May 1799) concerning the appropriation of fees and perquisites, and inclosing instructions issued to his predecessor which had to be strictly adhered to (ie no supplementation of salaries by fees) "except in the single instance of the Judge of the Vice Admiralty Court". See, further, Giliomee 1975: 99 n 57, who points out that after 1797 the only exceptions were the fiscal and the Admiralty judge, who also received a portion of fines levied in his Court.

157 In 1802 Holland was placed on the civil pay list and was paid directly by the paymaster: De Villiers 1967: 175; Giliomee 1975: 99.

158 See Theal RCC vol 2: 347-348 (letter Holland to Henry Dundas, 29 Jan 1799) and again n 50 in Part 1. He explained that a considerable portion, if not most, of all neutral ships (especially Danish ones) sailing to or from the East Indies that had entered, or had been captured and brought to, the Cape, had been commanded by Englishmen or Irishmen who had become naturalised Danes. As neutrals, they visited and traded from different settlements, including British ones and ones belonging to friendly nations. It was generally known that the greatest part of such ships and cargoes were, in fact, owned by British subjects residing in Britain or India and were merely coloured neutral. Their fraudulent trade (in monopoly goods) impacted on the Company's revenue. The problem was that, "[a]s the law stands at present (unless any act or regulation has taken place since I left England)", if a ship disguised as neutral was captured during a war on suspicion of having enemy property on board and was then brought into the Cape, but later appeared upon investigation to be the property of a British or Indian resident, and even though perhaps commandeered by a British subject or actually proved to be trading to or from India in violation of s 129 of the East India Co Act, 1792 (33 Geo III c 52), "yet the Vice Admiralty Court here would be bound to release such ship and cargo, having no power under the above Act to confiscate any property or to take any cognizance whatever of offences committed against it" (as it would if it were an enemy ship or a neutral ship carrying contraband). Holland therefore later raised the possibility "to invest the Vice Admiralty Court here with the same powers possessed by those in the East Indies and America" so as to enable it to deal with "the illicit encroachments on the Company's Trade". See, also, Theal RCC vol 2: 427-428 (letter Holland to Henry Dundas, 20 May 1799, in which Holland stated that his earlier sentiments had been fully justified by the case of the Eliza, an American vessel that had put briefly into the Cape for refreshments on an apparent voyage from Madras to New York; despite the absence of evidence in the colony, Holland himself had little doubt that the whole or greater part of her cargo, if not the ship herself, belonged to British subjects).

159 Theal RCC vol 2: 408-409 (letter Holland to Henry Dundas, 5 April 1799). See, again, at n 60f in Part 1.

160 On Lady Anne, see the wonderful recent biography by Stephen Taylor Defiance. The Life and Choices of Lady Anne Barnard (London, 2016).

161 There are several entries in her Diaries referring to dinner at the Hollands or to their coming over for dinner at the Barnards. The dinners were enhanced by local wines. She recounts (Barnard Diaries vol 1: 102-103, Sun 13 Apr 1799) that they went to Little Constantia - the owner of Constantia next door not being at home - which had some equally good (at least the white) wine, and that there the Barnards and the Hollands bought Ά aum (1 aum = 145l) of wine! Later that day, when the Hollands and others dined with the Barnards, the food was, to her sorrow, ill prepared by the servants without Lady Anne's earlier supervision, for, as she wrote, "a bad dinner is not an unimportant matter to Mr Holland".

162 Barnard Journals: 287.

163 Barnard Diaries vol 2: 105 (Apr 1800) tells what she calls "a homely little" tale: Holland had as Judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court condemned slaves to be prize property on the evidence of a "Black boy", who, on second examination of his evidence, prevaricated so much that Holland dismissed him, saying "your former evidence I see contains all you have to say, so you may go".

164 Barnard Letters: 176 (letter Sep 1798), writing that "we all like Mr Holland very much - I believe he is reckond by impartial people (which of course the partys seldom are) an upright judge - he has bad health, but I think he is a good humoured, agreeable man".

165 Barnard Diaries vol 1: 14 (9 Jan 1799), writing that when the Hollands came over for dinner, she observed that Mrs Holland has "of late been disposed to be rather more agreeable and companionable, he is always so, if his Health permit"; Barnard Diaries vol 1: 253 (25 Aug 7199), writing that when they dined at the Hollands with a number of other guests, the cold weather and heavy rains "agree ill with Mr Hollands asthma, he gasps and lives by aether". During the dinner, Holland "could not have resisted combatting [one of the guest's arguments] with legal ability, but he was not up to it"; Barnard Diaries vol 1: 315 (29 Oct 1799), describing dinner at the Pringles with the Hollands, where he had "a droll miff" with another (lady) guest "on the subject of cold pudding": there had been a very good plumb pudding at dinner and someone said it would be very good cold; Holland was "wheezing with the asthma & not much thinking what he was saying", as a result of which the lady guest left weeping; Barnard Diaries vol 1: 318 (4 Nov 1799), referring to Holland being agitated to such an extent by another guest's deceitful words as to "cut off six months enjoyment to his wheezing tenure of life"; Barnard Diaries vol 2: 240-241 (28 Sep 1800), describing dinner with the Hollands, "he asthmatic". Stroud 1966: 29 n 2 states that John Holland and his wife "lived mostly abroad because of his health" and at 147 that John "spent a great deal of time in Italy on account of his health" where he had many royal and artistic acquaintances.

166 Especially in his Court's correspondence in CA, BO 35; however, notary Rouviere's (see at n 207 infra) hand was, if at all possible, even worse (see, eg, CA, BO 35, 175-188).

167 See, eg, the entries for 1 Mar and 10 Mar 1799 (Barnard Diaries vol 1: 57, 69), both cases where the Hollands had come over for dinner and where there was evidence of altercations between the Judge and Gen Francis Dundas and of his uneasy relationship with the latter.

168 Barnard Diaries vol 1: 81-82 (22 Mar 1799).

169 See Theal RCC vol 2: 333-334 (letter from various British colonial officials at the Cape to Gen Dundas, 5 Jan 1799, expressing their support for the war effort "at home" and offering their services to defend "this valuable Colony" against "a host of Foreign and domestic Enemies"; apart from John Holland, it was signed by other members of the Court, namely Thomas Wittenoon(m), George Rex, Peter Mosse, William Menzies and William Sturgis, all of whom we will encounter shortly).

170 Barnard Diaries vol 1: 204 (27 Jul 1799).

171 Barnard Journals: 287.

172 See Barnard Diaries vol 1: 13 (9 Jan 1799), describing Mrs Holland as of late disposed to be rather more agreeable and companionable; idem: 30 (27-30 Jan 1799), stating that she has hopes for Mrs Holland as she was beginning to act rational.

173 Barnard Diaries vol 2: 209-210 (Aug 1800), referring to a dinner party at which the tiresome comte Franchecoeur sang - "like a cow lowing to be sure, & so affectedly that it was ridiculous enough" - and messrs Holland and Blake began laughing "illbredly", so that "the evening did not pass pleasantly"; Barnard Diaries vol 2: 257 (Oct 1800), describing an attendance at a sale of dresses of all kinds, including of the kind in which Marie Antoinette had been beheaded - "robe a La victime"; Mrs Holland purchased one as she "loves a bit of any thing new, the Cape was quite convenient she said for being guillotined, it rose up so High - in order to fall down so low! But as she did not intend to have the ax around her head she had trimd it with point lace which she had taken from a cap, some boxes of wc were also sold, vastly cheap".

174 Barnard Diaries vol 1: 94-95 (1, 2 Apr 1799), stating that Mrs Holland has improved "certainly on closer acquaintance, the fine lady going off and the reasonable little woman I hope by degrees coming in its place". But then, later (Barnard Diaries vol 2: 240-241 (28 Sep 1800), she described her as being "an old miss and will be one all her life".

175 Barnard Diaries vol 1: 210-211 (1 Aug 1799), describing how, at her ball, the company flirted, danced, ate, drank and, she was sorry to say, "one foolish woman wept - how can Mrs H[olland] become so very silly about a creature so contemptible as Major A[bercrombie]! one who asks but to show forth his power over this foolish old girl"; Barnard Diaries vol 1: 282 (26 Sep 1799), telling of an incident at a shop where Mrs Hogan had walked with Mrs Holland and her friend, the elder Mrs Losper (Laubscher?). When it was mentioned that Maj Abercrombie had arrived, Mrs Holland said nothing, but darted downstairs and pelted home as fast as she could, leaving Mrs Hogan without word of apology; Barnard Diaries vol 1: 283 (28 Sep 1799), describing that she visited "the poor foolish Holland who we found sitting in her chair in the attitude of thinking & expecting ... Major Ab, who followed us in; and very (exaggeratedly so) slight bow she made to him showed many things all very silly". Abercrombie later married the younger Laubscher daughter, Kaatje (Catharine Cornelia), but Mrs Holland's infatuation continued: Barnard Diaries vol 1: 311 (Oct 1799), writing that she saw a surprising thing: "a deluge of tears from the large blew eyes of Mrs Holland, Major Abercrombie by her side & his wife at the far end of the table ... how foolish it is in that little woman not to close the connection now, married as he is from choice to another"; Barnard Diaries vol 1: 315 (29 Oct 1799), describing dinner at the Pringles with the Hollands, and also with Maj Abercrombie, without his wife, and everyone being aware that Mrs Holland was "not cured"; Barnard Diaries vol 2: 47 (9 Feb 1800), describing how, on visiting, they found Mrs Holland in tears, Maj Abercrombie alone with her and Mr Holland sitting over a bottle with a gentleman in the Hall; she and the Major seemed so much disconcerted and so melancholy that the visit was cut short; on leaving, the Judge followed Lady Anne out, looked at his wife and with an appealing smile to Lady Anne shook his head in a way that she could see an uncle or father would do, but in a manner that did not seem to belong to a husband: how could he smile at tears so oddly bestowed, Lady Anne could not understand at all. Major Peter Abercrombie served at the Cape 1796-1802 and married Catherine Cornelia Laubscher in Nov 1799; she left with him when he went with his regiment to India, but returned as a widow in 1808: see Philip 1981:1.

176 Barnard Diaries vol 1: 234 (13 Aug 1799), describing how, after Holland had made "some common place jest of soldiers being careless of their wives", Gen John Henry Fraser (commanding officer of the troops at the Cape in the absence of Gen Dundas, Aug-Dec 1799: Philip 1981: 133) took it personally and replied that he thought soldiers took very good care not only of their own wives, but also of the wives of civilians, and then applied it "in flat & brutal terms to Mrs Holland and Major Abercrombie"; Lady Anne remarked that she thought "Mr H was hurt" by these remarks.

177 To her letter to Earl Macartney, dated 15 Feb 1800 (see Fairbridge 1924: 168-169), Lady Anne added "a bit of good jest" as an addendum. It concerned the Hollands' good French cook, a prisoner of war from the Battery, who was returned there. The reason, the Judge later explained, was because the cook was mad. But Mrs Holland later told Lady Anne that the poor man was certainly not so very mad, but mighty odd and tiresome. She explained that he had asked to be paid off and to be returned to prison because, so he told her, he loved her; he later sent her a letter, declaring his affection. "The poor cook's secret could no longer be concealed", Lady Anne continued, "but what is very provoking, everyone thinks him madder than Mrs Holland". Back in prison, the cook would go to no other employment the Judge would find him, calling loudly for death to end his sorrows and imploring the Judge's pardon on his knees for the presumption of his sentiments. But then Lady Anne concluded: "N. B.- Tho I tell this gayly, don't conceive the slightest ridicule or reflection on Mrs Holland by it." See, also, Barnard Diaries vol 2: 33-34 (Feb 1800), writing that her husband did not believe that any man would be so mad as to fall in love "with this poor pretty little woman unless he had been a little invited" and that Mrs Holland had certainly sighed when Lady Anne referred to "poor Cookie".

178 See Fairbridge 1924: 225 (letter Lady Anne Barnard to Earl Macartney, 18 Oct 1800).

179 See Cape Town Gazette of 10 Nov and 13 Dec 1800, describing the house as "situate in the neighbourhood" of Cape Town, previously belonging to Mr Casper Loos and now the property of, and occupied by, Holland. It was advertised for sale by public auction, together with "several slaves, wagons, carts and sundry garden and husbandry utensils".

180 See CA, NCD 1/35/823 for the notarial protocol, dated 7 May 1801, by which Holland sold to "Pester" (sic: Bester) for Rds50 000 the property which had formerly belonged to, and which he had bought from, Johan Caper Loos, and by which Pester sold him his house in town for Rds80 000.

181 For the notarial protocol, dated 24 Jun 1801, pertaining to the obligation on Holland's part to pay the outstanding amount of some Rds30 000 to Bester, to be paid over period of a year, see CA, NCD 1/28/790 (1801), in Dutch together with a translation into English. See, also, Cape Town Gazette of 23 and 30 May 1801, advertising a sale in the garden of the house formerly belonging to Carel Bester and now to Holland. This exchange of properties caused Holland to send off a memorial, dated 3 Jul 1801, to Governor Dundas concerning the apportionment of transfer duties, which was allowed, duty being payable on the difference between the values of the two properties: see CA, BO 121/34/1 (1801).

182 Barnard Diaries vol 2: 49 (10 Feb 1800), describing how, after dinner, the Barnards "walked up to see Mr Hollands house wc is behind this - I did not much like it [it had "a very circumscribed view, sadly enclosed"] but as he has paid about 30,000 for it & has still much to do to render it convenient I did not say so". She expressed a similar sentiment when she visited it on 10 Mar 1800, after some improvements had been made: see Barnard Diaries vol 2: 69: "I did not like it so well as I did before it was fitted up with its bare clean walls, the paper was ugly and the roof painted so dark as to lose the chearful look it had before."

183 See Fairbridge 1924: 279-280 (letter Lady Anne Barnard to Earl Macartney, 27 May 1801, recounting that Holland had sold his country house and came to live in town again, "in the same house he was in before, which by a variety of manoeuvres now costs him 80 000 dollars").

184 These being Rex, who retired and went farming at Knysna, Rowles and Pontardent, who left but later returned to the Cape, and Ziervogel, who, being a local recruit, remained. More about them shortly.

185 See, eg, CA, NCD 1/39/358 (1798) for a notarial protocol concerning the transfer by Adv Peter Mosse (see at n 248 infra) of the slave "Spasie van de Caab" to Holland in Dec 1798; CA, NCD 1/15/1400 and 1404 (1801) for a notarial protocol dated 21 Jan 1801, by which Holland gave a special power of attorney to Jan Bernhard Hoffman regarding a dispute in the Court of Justice with Jean Charles de la Harpe over the sale of a slave.

186 Chief justice rather than merely judge, presumably because there were other Admiralty judges in other locations on the island.

187 See The New Jamaica Almanack and Register ...for... 1801 (Kingston, 1801) at 109. An amount of £473 8s 1d was budgeted for Holland (as also for the chief justices of the Vice-Admiralty courts at the Bahamas and Barbados) from the consolidated fund for the year ending Jan 1804 with a future annual charge of £2 000 p/a, probably his salary: see House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Accounts Respecting the Public Expenditure of Great Britain, for the Year Ended 5 January, 1804 (HCPP 1803-1804 (vol 23)) at 11; in idem Accounts Respecting the Public Income of Great Britain, for the Year Ended 5 January, 1804, at 87 there is mention of "Henry [sic] Holland, Esq, Chief Justice of the Admiralty Court in the Island of Jamaica, per Act 43 Geo III". The following year, during which he died, the amount was £328 1s 9d, maybe the part of his salary due on his death: see Parliamentary Debates vol 5: 15 May to 12 Jul 1805, "Account of the Charges upon the Consolidated Fund, in the year ending 5th Jan 1805" at ccxxxi.

188 See Crump 1931: 91-105; see, also, Leach 1960; Butterfield 1938: 97, distinguishing between the records of the Vice-Admiralty Court and those of "the special courts of oyer and terminer for the jurisdiction of the admiralty of the island of Jamaica, which tried ... felonies committed on the high seas, piracies, and murder". As Chief Justice of the Vice-Admiralty Court, Holland was also a member of the Court of Admiralty Sessions, the name for the Piracy Court there.

189 And like Vice-Admiralty courts elsewhere, the Jamaican one was relatively quiet outside of war. One of Holland's better-known predecessors, Edward Long (1734-1813), although reviled today (see Seth 2014), but nevertheless remembered as an historian and the author of The History of Jamaica (published in 3 vols in London in 1774), wrote (in vol 1 at 78) that "in time of peace, it is a court of no profit, and of very little business". On Long, see also Bridges 1828, vol 1: 26; SP 1933.

190 His immediate predecessor in 1801 was George Cuthbert: see The New Jamaica Almanack and Register ... for ... 1801 (Kingston, 1801): 109. The well-known naval historian, William James, was a proctor in Holland's Vice-Admiralty Court in 1803: see AB Sainsbury "Duckworth, Sir John Thomas" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004, online ed Jan 2009, accessed 19 Aug 2015).

191 On Lady Nugent (1770/1-1834), see Rosemary Cargill Raza "Nugent [née Skinner], Maria" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004, online ed 2009, accessed 19 Aug 2015). Her diary was published in 1966, and reprinted in 2004: see Wright 2004. George Nugent (1757-1849) was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica in 1801, where he remained until 1806. Lady Nugent returned to England in 1805 for the sake of their children's health.

192 Wright 2004: 184.

193 Ibid.

194 Idem at 192. She had learned, from Adam Dolmage, the Court's Deputy Registrar, that Holland had "just fired a Gun at some Cattle which had broken into his garden when a blood Vessel burst & he died"; idem at 192 n 1.

195 See Lawrence-Archer 1875: 234; Wright 1966: 57.