Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Journal of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering

versión On-line ISSN 2309-8775

versión impresa ISSN 1021-2019

J. S. Afr. Inst. Civ. Eng. vol.62 no.1 Midrand mar. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8775/2020/v62n1a5

TECHNICAL PAPER

Factors that keep engineers committed to their organisations: A study of south African knowledge workers

C L Blersch; B C Shrand; L Ronnie

ABSTRACT

Organisational commitment has been consistently linked with positive workplace outcomes such as increased job satisfaction and reduced intention to quit, important considerations for retaining critical skills such as those possessed by knowledge workers. This research explored factors that influenced knowledge worker organisational commitment in the South African consulting engineering environment. A quantitative cross-sectional study was conducted through an online survey at one office of a multinational professional services company employing mainly engineers, eliciting 104 responses. The questionnaire comprised established instruments to reliably measure a selection of organisational commitment antecedents. Commitment, both to the organisation, as well as to the employee's occupation, was measured using a validated "unidimensional target-free" conceptualisation of the commitment construct that is arguably less confounded than previous measures. Organisational commitment was found to be positively correlated with perceived organisational support, satisfaction with pay, autonomy and occupational commitment. The strongest correlation was found with occupational commitment, which was found to be stronger than organisational commitment. These findings contribute to the understanding of how South African knowledge workers' organisational commitment can be influenced. In turn, managers of engineers may gain useful insights in terms of how to encourage engineers' willingness to stay at the organisation.

Keywords: organisational commitment, engineers, knowledge workers, retention

INTRODUCTION

Engineers and other technically skilled people working in the engineering environment can be classified as knowledge workers. Knowledge workers are defined as individuals who possess prior knowledge, education and skills, and draw on their experience in an organisation to develop their knowledge and skills further (Jayasingam & Yong 2013). Knowledge workers are unique, because their knowledge is embedded in the individual rather than the organisation. Retention of knowledge workers is, therefore, critical for preventing loss of information in any organisation that relies on intellectual capital for success (Giauque et al 2010; Jayasingam et al 2016).

Retaining knowledge workers is of particular importance to the engineering environment in South Africa, given the current shortage of engineers. At a national level, South Africa has a ratio of GDP to number of engineers of $16.4 million/ engineer, 20 percent higher than other countries such as Australia, USA, Ireland and Canada who are signatories to the Engineers Mobility Forum (Watermeyer & Pillay 2012). As these authors explained, maintaining a healthy quota of engineers is important for ensuring delivery of infrastructure to support socio-economic growth and sustainable development. However, in the past 15 years, there have been times where close to 100 percent of the firms surveyed by Consulting Engineers South Africa (CESA) had been experiencing difficulties in recruiting engineers (CESA 2016).

Actual employee turnover is closely linked to turnover intention (Chen 2005), defined as "a conscious and deliberate willingness to leave the organisation" (Egan et al 2004:286). Individual turnover intention has been found to be reduced when employees develop organisational commitment. Klein et al (2012) defined commitment as a "volitional psychological bond reflecting dedication to or responsibility for a particular target" (p 138). When the commitment bond forms between an individual and an organisation, it binds the individual to the organisation, reducing the likelihood of the person leaving (Meyer & Herscovitch 2001). In addition to reducing turnover intention, organisational commitment encourages other desirable work outcomes, such as increased job satisfaction, reduced absenteeism and in-role performance (Klein et al 2012; Jayasingam & Yong 2013; Jayasingam et al 2016; Meyer 2009; Meyer & Herscovitch 2001). It is thus in management's best interest to nurture employees' commitment to the organisation.

There are a variety of factors that have been found to motivate and retain knowledge workers and influence their levels of organisational commitment. These factors include the freedom to act autonomously (Jayasingam et al 2016), challenging and fulfilling work (Horwitz et al 2003), coworker and supervisor support (Benson & Brown 2007), perceived organisational support (Giauque et al 2010) and, to an extent, satisfaction with pay (Jayasingam & Yong 2013). Furthermore, there is a strong relationship between knowledge workers' commitment to their occupation (or profession) and their organisation (Horwitz et al 2003). Knowledge workers thus possess qualities and characteristics that require tailored approaches in order to encourage organisational commitment and its associated positive outcomes (Horwitz et al 2003). There is a paucity of studies that have sought to understand the factors that specifically influence the organisational commitment of South African consulting engineers. This study addresses this gap and explores antecedents of organisational commitment in the South African consulting engineering environment, both at an overall level, and by comparing differences among selected demographic groups.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Organisational commitment

Defining commitment

Organisational commitment research has been ongoing since the early 1960s. As Klein et al (2009) explained, the evolution of organisational commitment's definition has resulted in a broad array of conceptualisations in which commitment has been defined as an attitude, a bond, a force, investment or exchange, identification, congruence, motivation, and continuance. However, for the past two decades, the most prominent and well-used conceptualisation has been the Three Component Model (TCM), developed by Meyer and Allen (1991), which comprises three overlapping components: continuance commitment, normative commitment, and affective commitment.

Firstly, continuance commitment refers to a need to stay within an organisation as a result of the perceived costs of leaving and the benefits of remaining. Secondly, normative commitment refers to an individual's perceived obligation to remain within the organisation where the person feels he/she ought to stay out of a sense of duty. Thirdly, affective commitment refers to an emotional bond with the organisation where the person feels that he/she wants to stay out of his/her own volition. Across studies, affective commitment was found to have the strongest and most consistent link with desirable outcomes (Becker et al 2009). Consequently, some authors have reverted to considering affective commitment only, believing that it represents the most reliable and strongly validated dimension of organisational commitment (Solinger et al 2008).

Recently, Klein et al (2012) provided an alternative way to measure feelings associated with affective commitment that addressed these authors' concerns regarding TCM. Firstly, they argued that the three components all relate to different phenomena, bonds or attachments that cannot be grouped together as components of commitment, and secondly that the concept of commitment applies to all workplace bonds, not only to the organisation. They argued that attempts to conceptualise commitment as a multi-dimensional construct have led to a "lack of definitional clarity" (p 131) and confusion.

Klein et al (2012) posited that different forms of extrinsic motivation are linked to a discontinuous continuum of bonds or "distinct psychological phenomena" (p 133), each with their own circumstances and outcomes. The authors defined commitment as being a unidimensional construct, a specific type of psychological bond that has a distinct meaning and similar antecedents and consequences in all contexts. Commitment bonds were defined as embracing and "volitional psychological bonds reflecting dedication to or responsibility for a particular target" (p 138). The authors further posited that commitment is the result of a conscious decision and is therefore more internally than externally regulated.

In accordance with their definition of commitment as a unidimensional construct, Klein et al (2014) developed the Klein et al Unidimensional Target-free Model (KUTM) scale. It comprises four items which, the authors asserted, could be used to measure commitment to any target (such as an organisation, occupation or person). Their testing and validation of the scale concluded that KUTM was distinct from previous commitment measures and offered methodological advantages.

Comparing KUTM to TCM, Klein et al (2014) found that the commitment bond was positively and significantly correlated with affective and, to a lesser extent, normative commitment. Given its strong correlation to affective commitment and its applicability to different targets, this study has adopted the KUTM approach to measuring engineering consultants' commitment to their organisation, as well as to their occupation. At the time of conducting this research, no studies related to the application of KUTM in the consulting engineering environment had been conducted, making this a novel approach.

Outcomes of organisational commitment

The importance of understanding and evaluating organisational commitment is rooted in the correlations established between organisational commitment and a variety of positive outcomes. Employees who are committed to an organisation are likely to align with the goals and values of the organisation and, thus, exert additional effort on the organisation's behalf, leading to better job performance (Baugh & Roberts 1994; Meyer et al 2002). Klein et al (2012) further noted a relationship between commitment and action, explaining that commitment often has a positive correlation with in-role performance.

In addition to job performance, positive outcomes correlated with organisational commitment included reduced absenteeism (Meyer 2009), increased altruism and conscientiousness (Meyer et al 2002), increased promotion of the organisation to outsiders (Bagraim 2004), higher levels of job satisfaction (Baugh & Roberts 1994), improved employee well-being (Meyer 2009) and reduced stress and work-family conflict (Meyer et al 2002). Klein et al (2012) further noted the importance of the correlation between commitment and motivation. Commitment leads to an allocation of effort towards supporting and participating in the organisation and an increased likelihood of allocating personal resources, such as time, to the organisation. Committed employees are more likely to be engaged and thus willing to "expend personal energies" (Klein et al 2012, p 144) on the organisation's behalf.

Importantly, organisational commitment has consistently been found to be significantly negatively correlated with employee turnover intention that, in turn, is closely linked to actual turnover (Allen & Meyer 1990; Chen 2005; Jayasingam et al 2016; Klein et al 2012). A study examining this link found this true in the case of South African knowledge workers (Bagraim 2004).

Factors influencing organisational commitment

Overview of commitment antecedents

Klein et al (2012) tested a variety of commitment antecedents when assessing the validity of their new commitment construct. The authors defined five categories of commitment antecedents, including individual characteristics (values and personality), target characteristics (nature and closeness), interpersonal factors (societal influences, social exchange, leader-manager exchange, supervisor supportiveness, perceived organisational support, psychological contract), organisational factors (cultures, climate and HR), and societal factors (cultural and economic). All of these factors impact on employee perceptions and may lead to the formation of a commitment bond. However, for the purpose of this study, only a subset of affective commitment antecedents that are known to be relevant to knowledge workers, and thus engineers, will be discussed. Given the paucity of literature on this topic specific to engineers, the authors drew on knowledge worker-related literature, as engineers exemplify knowledge workers.

Autonomy

Autonomy (or the freedom to act, do things differently and plan one's work) was the most commonly mentioned antecedent of organisational commitment in knowledge workers in general, and engineers in particular (Benson & Brown 2007; Jayasingam et al 2016; Malhotra et al 2007; Nazir et al 2016). Autonomy has also been frequently linked with motivation and retention in knowledge workers. A possible explanation for the importance of autonomy is that knowledge workers possess a strong internal locus of control and a desire to feel in control of their own destiny. As a result, they appreciate high degrees of autonomy and discretion in the work environment (Jayasingam & Yong 2013).

Rewards and satisfaction with pay

There are conflicting views on the importance of pay as it relates to knowledge workers' organisational commitment. Benson and Brown (2007) and Giauque et al (2010) found no correlation between satisfaction with pay and affective commitment, and in another study, Malhotra et al (2007) found no correlation between satisfaction with pay or benefits and organisational commitment. The explanation for these findings is that knowledge workers care more about personal growth and are looking for more than just financial compensation (Jayasingam & Yong 2013).

However, Jayasingam and Yong (2013) found that satisfaction with pay had a positive effect on affective commitment and that this was more pronounced in what they call "low knowledge workers". In "high knowledge workers" it was found to be a pre-requisite for affective commitment, but not a motivator above a moderate level. Kinnear and Sutherland (2000) also found that financial reward and recognition had a significant impact on commitment and Tam et al (2002) found a correlation between satisfaction with pay and overall job satisfaction, however, not with discretionary work effort. According to Horwitz et al (2003), offering competitive pay packages was one of the most effective strategies in retaining knowledge workers, and dissatisfaction with pay was often the reason for knowledge worker turnover.

Co-worker and supervisor support

Both co-worker and supervisor support have been found to be primary determinants of both organisational commitment and intention to quit in knowledge workers (Jayasingam et al 2016; Nazir et al 2016). In their comparative study, Benson and Brown (2007) found that co-worker and supervisor support had a greater influence on commitment for knowledge workers than for routine workers. Co-worker and supervisor support relate to the interaction between employees and the organisation.

An environment which is friendly and supportive strengthens the psychological commitment bond between the knowledge worker and the organisation (Benson & Brown 2007). At a more interpersonal level, friendships with co-workers and supervisors in an interactive work environment can serve as a social incentive to remain committed through a felt obligation or desire to protect one's reputation (Dachner & Miguel 2015). This can increase positive attitudes which, in turn, builds commitment.

Organisational support

Perceived organisational support relates to the extent to which an individual believes that he/she is valued, cared for and supported by the organisation and can include aspects such as autonomy, active listening and encouraging work-life balance (Giauque et al 2010). It differs from supervisor support in that it relates to a perception about the organisation as an entity rather than about a specific person.

In their meta-analysis, Meyer et al (2002) found that work experiences correlated strongly with affective commitment, with perceived organisational support having the strongest correlation. As the authors explained, to obtain affectively committed employees, an organisation needs to demonstrate its own commitment by providing a supportive environment. Similar correlations were found by Giauque et al (2010) in a study specific to knowledge workers, suggesting that providing organisational support to engineers might encourage their commitment.

Occupational commitment

Using Klein et al 's (2012) conceptualisation of commitment, occupational commitment refers to the volitional psychological bond between a person and his/her occupation (e.g. engineering). Various authors have hypothesised about the incompatibility of organisational and occupational commitment which results from the conflict between occupational self-control (autonomy) and organisational bureaucracy and controls, and between loyalty to an organisation and loyalty to clients (Vandenberg & Scarpello 1994). However, in general the literature suggests a positive relationship between the two variables. In a meta-analysis, Lee et al (2000) found that occupational commitment correlated with an array of positive organisational or job-specific outcomes. Individuals who possess a strong psychological bond with their occupation are more likely to be satisfied within their organisation, and exert discretionary work effort. Lee et al (2000) further compared organisational and occupational commitment, and found a strong correlation, particularly amongst individuals working within their field of expertise. In one of the few longitudinal studies, Vandenberg and Scarpello (1994) were able to test causality between the constructs and found that occupational commitment leads to organisational commitment.

Professionals such as engineers tend to identify more strongly with their occupation than their organisation (Ashforth et al 2013; Horwitz et al 2003; Tam et al 2002), and various authors have found that the relationship between the two forms of commitment is strongest amongst this grouping (Lee et al 2000; Wallace 1993).

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Approach

A cross-sectional quantitative approach was followed. The nature of the study was exploratory. A convenience sampling approach was taken, with the research conducted at Consulticon1, a multinational consulting engineering and technical advisory company of approximately 6 000 people. The South African office of the company, employing about 500 people, was sampled. Knowledge workers were defined as technical employees including engineering technicians, engineering technologists, engineers and scientists.

Data collection

Data was collected using an online web-based survey. A pilot study was sent to six employees, comprising a draft questionnaire and covering mail. The aim of the pilot study was to assess the survey length, ensure that the wording was easy to understand and unambiguous, and to test the functionality and usability of the survey platform. The revised questionnaire was distributed via email. This was a pragmatic choice as it saved time in distributing and collecting data, allowed participants flexibility to complete the survey, eliminated potential interviewer bias and ensured anonymity. Personnel who were deemed outside of the scope of what was defined as knowledge workers were filtered out of the analysis after data collection, on the bases of level of education, occupation and job designation.

Sample demographics

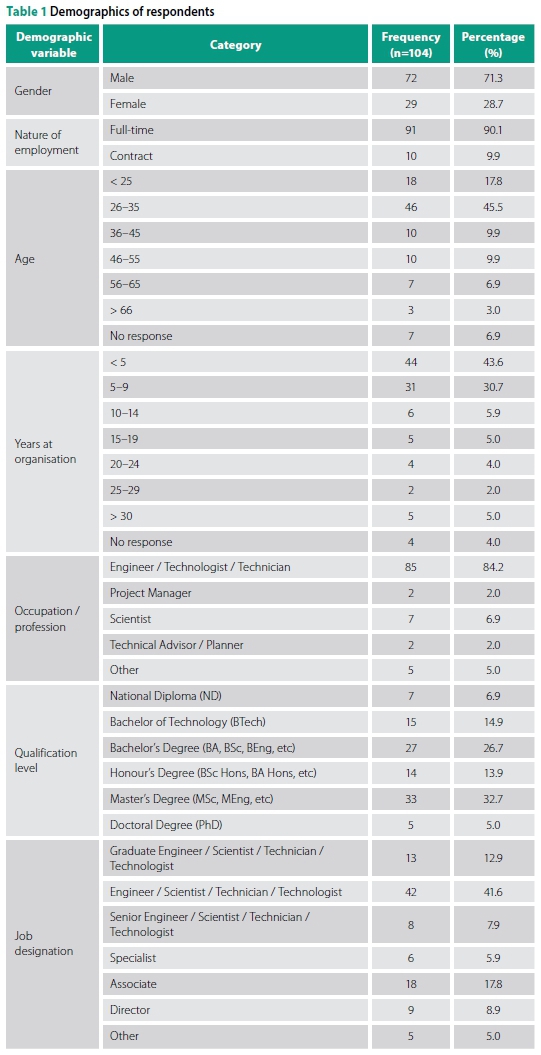

A total of 101 usable responses were received, resulting in an 18 percent response rate. Work pressures, as well as possible survey fatigue, may have accounted for the low response rate.

As shown in Table 1, 29 percent of the responses were female and 71 percent were male, representing the gender split in the organisation. Ninety percent of the respondents were full-time employees with ten percent employed on a contract basis. Respondents' ages ranged from 22 to 75 years, with an average age of 35 years and median of 29 years. The age distribution was clearly negatively skewed, with 63 percent of respondents falling into the 'young professional' bracket, under the age of 35 years. However, this was representative of the organisation's age profile. As expected, the number of years that respondents had been employed by the organisation followed a similar trend to age.

As Table 1 shows, the majority of respondents (84 percent) were in the engineering profession. The remaining 16 percent included scientists, technical advisors or planners and project managers. Of the engineering professionals, 8 percent of respondents were engineering technicians, 16 percent were engineering technologists and 75 percent were engineers. All respondents had some form of post-matriculation qualification.

Lastly, considering job designation, in line with the age distribution, 55 percent of respondents fell into the junior job designation categories, which included administrative staff, new graduates and those who were still in training towards professional registration. The 41 percent of senior respondents included registered professionals, specialists and those with management titles (for example, associates and directors).

Measures

Organisational commitment was measured using KUTM (Klein et al 2014), comprising the four items below. A five-point Likert scale was used ranging from "Not at all" to "Extremely".

1. How committed are you to your organisation2?

2. To what extent do you care about your organisation?

3. How dedicated are you to your organisation?

4. To what extent have you chosen to be committed to your organisation?

For all the independent variables, a five-point Likert scale was used ranging from "Strongly Disagree" to "Strongly Agree". Measures selected were as described below.

■ Occupational commitment (OC) was measured using the four scale items of the KUTM (Klein et al 2012) with the term "organisation" replaced by "occupation".

■ Autonomy (AUT) was measured using the three items of the Job Diagnostic Survey developed by Hackman and Oldham (1975), which relate specifically to job autonomy. For example:

My job gives me opportunity for freedom in how I do my work.

■ Satisfaction with pay (SP) was measured using the 18-item Pay Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ) developed by Heneman and Schwab (1985), which taps into four dimensions of pay related to level, benefits, raises and structure or administration. The four items related to the "benefits" dimension were removed to better align with Consulticon's pay scales, and a few repetitive items were removed. Example items for each dimension of pay included:

I am satisfied with my current salary. [Level]

I am satisfied with how my raises are determined. [Raises]

I am satisfied with my organisation's pay structure. [Structure / Administration]

■ Supervisor support (SS) was measured using the nine-item scale used by Malhotra et al (2007) and Nazir et al (2016), including items that refer to participation in decision-making. This included scale items such as:

I am satisfied with the way my supervisor helps me achieve my goals.

■ Co-worker support (CS) was measured using the four-item scale used by Malhotra et al (2007), which comprised items like:

My co-workers are helpful to me in getting my job done.

■ Perceived organisational support (OS) was measured using the shortened form (eight items) of the original 36-item instrument developed by Eisenberger et al (1997). Example items included:

My organisation really cares about my well-being.

In terms of the control variables, respondents were asked to provide their gender, age, tenure, occupation, highest level of qualification, job classification level (using terminology relevant to Consulticon), and employment status (full-time or contract). The control variables were in line with those found in most previous organisational commitment studies. Ethnicity was not used as a control variable, as it was a concern that this would partly jeopardise anonymity by creating easy identifiers in conjunction with the other control variables.

Data analysis methods

Skewness and kurtosis were calculated for each set of data to test for normality using the statistical analysis functions in Microsoft Excel 2016. The Jarque-Bera test was then applied to calculate a test statistic which, for normally distributed data, has a Chi-square distribution with two degrees of freedom (Zaiontz 2016). Secondly, the D'Agostino-Pearson test was applied, which again uses both skewness and kurtosis. In addition to the individual tests for skew-ness and kurtosis above, the combined D'Agostino-Pearson test was also performed (Zaiontz 2016). For both cases, the Chi-square function in Microsoft Excel 2016 was used. Lastly, a graphical analysis was undertaken using quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots.

Pearson's sample correlation coefficients were calculated, and significance of the correlations were evaluated using Student's t-test for a correlation (Wegner 2016). The use of Student's t-distribution for testing for inference assumes that the bivariate data is normally distributed. In addition, Kendall's Tau correlation coefficients were calculated using the version adapted for data which contains many duplicates or ties (Zaiontz 2016). Kendall's Tau can be used for hypothesis testing even when both sets of data are not normally distributed. Based on the tests for normality, organisational commitment, satisfaction with pay and turnover intention were normally distributed, whilst the other factors were not. Given that four of the seven parameters were not normally distributed, Kendall's Tau was selected as the most appropriate method for calculation of correlations.

Considering the demographic control variables including age, gender, occupation, tenure, job position and nature of employment (full-time or contract), the t-test and F-test were applied.

The data was split into two sets using the control variables, generally according to the median value. The t-test was then used to compare the means of the data sets and determine whether there were any significant differences across the control variables. Differences in correlations across the control variables were also examined, using the Fisher Transformation of the Pearson's correlation coefficients, and the test statistic z (Zaiontz 2016). The test statistic is normally distributed when the correlations are equal.

For all tests mentioned above, a significance value (a) of 0.05 was used. Although frequently critiqued, P-values have been used as the "gold standard" for measuring statistical validity since the 1920s (Nuzzo 2014). A P-value of 0.05 means that correlations were deemed to be statistically significant when the tests showed that the chance of an error was less than 5% (Bryman & Bell 2015).

Research ethics

The research required participants to disclose sensitive information and therefore questionnaires were anonymous. Participants were asked to disclose only

basic demographic information. All results were aggregated and answers were thus confidential. Both the organisation and the individual participants gave written consent for taking part in the research.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for organisational commitment and the six commitment antecedents that were tested. Possible scores range from 1 to 5. The mean commitment score of 4.08 suggests fairly high organisational commitment levels, further evidenced by the negative skewness. Considering the antecedents, the lowest scores found were for satisfaction with pay and perceived organisational support. Occupational commitment and co-worker support showed the highest scores. For all antecedents, the distributions were negatively skewed, suggesting more positive than negative feelings from respondents related to each of the antecedents.

Correlations

Bivariate correlations were tested using the methods previously outlined, including Pearson's r, Fisher Transformation r', and Kendall's Tau. Although the calculated correlation coefficients using the different methods varied, the results in terms of the significance of these correlations showed little variation across the methods.

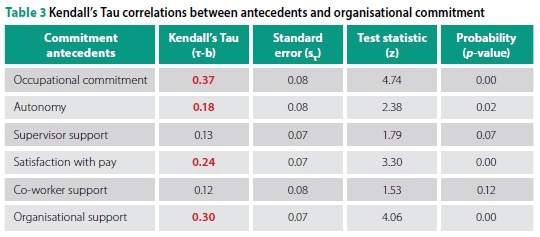

The calculated correlation coefficients using Kendall's Tau (x-b), the standard error (sx), test statistic (z) and probability (p-value) are presented in Table 3. Based on a significance level a of 0.05 (which reflects statistically significant correlations as previously explained), the significant correlations are highlighted in bold.

Statistically significant correlations were found with four of the antecedents, including occupational commitment, autonomy, satisfaction with pay and organisational support. Of the antecedents, the strongest correlation was with occupational commitment and the weakest was with co-worker support. Organisational commitment was also found to be significantly negatively correlated with turnover intention.

Control variables

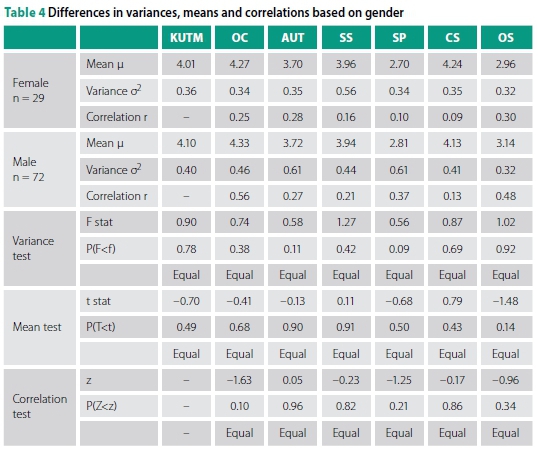

Variances, means and correlations were compared across the control variances to assess whether there were any significant differences. As Table 4 (page 47) shows, no significant differences were found in variances, means or correlations by gender.

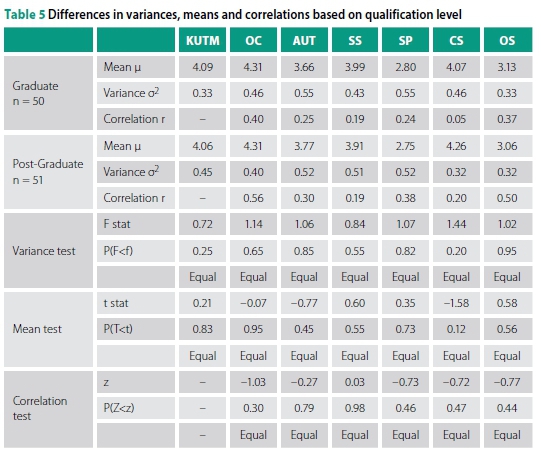

Table 5 shows that, as with gender, no significant differences were found in variances, means or correlations by qualification level.

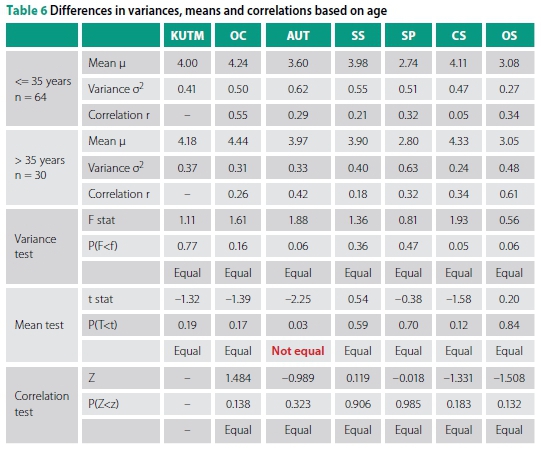

As shown in Table 6, a significant difference in variance and mean was found for autonomy. Older respondents, on average, felt they had more autonomy and there was greater variability in the autonomy levels experienced by younger respondents.

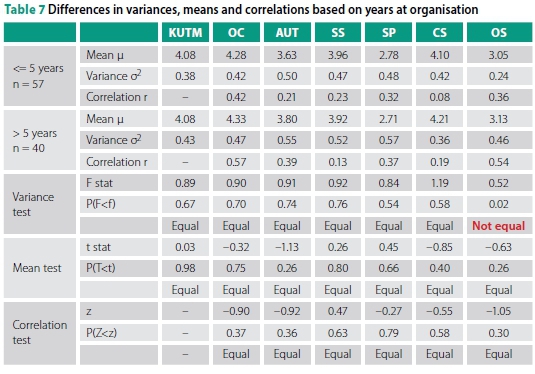

Respondents who have been employed by the organisation for five years or less were compared with those who have been employed for more than five years, as Table 7 shows. A significant difference in variance was found for organisational support, with those employed for longer showing greater variability in the extent to which they felt supported by the organisation. This suggests that feelings of support from the organisation diverge as a person progresses in their career.

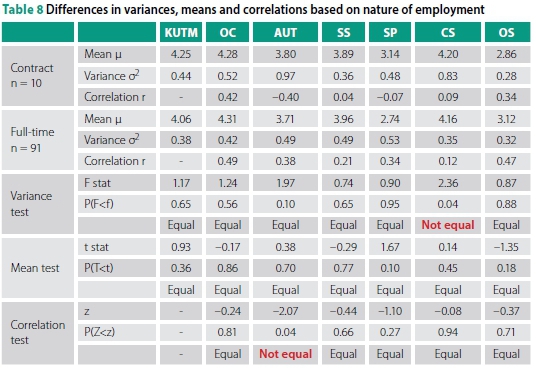

When comparing contract and fulltime employees, as shown in Table 8, no significant differences were found in mean for any of the parameters. However, a significant difference in the variance for co-worker support was noted, with contract employees experiencing more variability in co-worker support, possibly due to their wider range of tenure or different amounts of time spent at the office engaging with co-workers. A significant difference was also found in the correlation between autonomy and organisational commitment. There was a stronger link between autonomy and commitment for full-time employees.

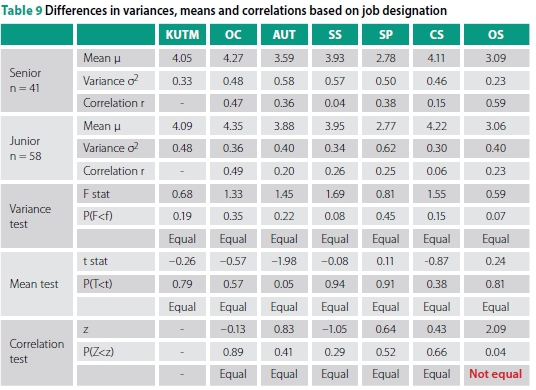

Lastly, as seen in Table 9, no significant differences were found between variances or means for junior and senior employees by job designation. However, a significant difference was found for correlation of organisational support and organisational commitment. Senior employees showed a stronger link between organisational support and organisational commitment.

Reasons for the aforementioned differences are provided in the analysis and discussion of the results which follow.

ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

Autonomy

Autonomy was significantly correlated with organisational commitment, which supports the findings of previous authors (Benson & Brown 2007; Jayasingam et al 2016; Malhotra et al 2007; Nazir et al 2016). Despite being one of the more frequently quoted antecedents of commitment in knowledge workers in the literature, it ranked fourth in terms of the strength of correlation, suggesting that there are more significant factors at play. This could be related to the fact that mean and median scores for autonomy were lower than some of the other measures.

Considering the demographic control variables, the mean score for autonomy was lower for the younger engineers or engineering employees. This makes sense, given that levels of autonomy tend to increase with age as a person receives more responsibility and requires less supervision in undertaking their work. One might have expected a similar pattern with job designation and tenure. However, it was interesting that no significant differences in levels of autonomy were noted for either job designation or tenure. Looking more closely at job designation, the mean score for autonomy for senior employees was 3.88 compared to 3.59 for junior employees with a p-value of 0.05 so very close to signalling a significant difference. This would have been expected. However, given that age and tenure were found to be significantly positively correlated in this study (0.78; p = 0.000), it was surprising that there was no difference in autonomy based on tenure.

Lastly, the correlation between autonomy and organisational commitment was significantly higher for full-time employees than contract employees. This may be because the contract employees included everyone from interns to retirees, and thus autonomy levels were more varied and thus less relatable to organisational commitment levels. The small size of the contract employee sample could offer an alternate explanation.

Satisfaction with pay

Satisfaction with pay was found to be significantly positively correlated with organisational commitment. This supports the findings of Jayasingam and Yong (2013) and Kinnear and Sutherland (2000) who both found that satisfaction with pay, financial reward and recognition positively influenced organisational commitment.

Differences between mean satisfaction with pay scores would have been expected between the age groups, years of experience, job designation and qualification levels. It was expected that the more senior, qualified and experienced groups would be more satisfied with their pay than the junior groups. However, the variances and means were consistent across all control variables. Interestingly, correlations between satisfaction with pay and organisational commitment were also consistent across all control variables, suggesting that the relationship between satisfaction with pay and commitment does not change with age or seniority.

Co-worker support and supervisor support

Both supervisor support and co-worker support were not significantly correlated with organisational commitment. This finding contradicts both Benson and Brown's (2007) assertion that a friendly and supportive environment strengthens the psychological commitment bond between an employee and the organisation, and Dachner and Miguel's (2015) assertion that friendships with co-workers and supervisors can act as a social incentive to remain committed.

The mean scores for co-worker support and supervisor support were the second and third highest of the antecedents, and both were significantly negatively skewed according to the tests for normality. This suggests that, in general, respondents felt strongly supported by their co-workers and supervisors. However, this did not correlate with the respondents' volitional psychological bond, dedication and responsibility for the organisation (Klein et al 2012).

Mean scores and correlations were consistent for both co-worker support and supervisor support across all control variables. It makes sense that an individual's feeling of being supported by his/ her co-workers and/or supervisor would not change significantly with age, seniority, qualification level or gender. However, it might have been expected that tenure would affect the mean scores, as individuals who have been at the organisation for longer would have had more time to form supportive relationships with their co-workers and supervisors. Surprisingly, this was not the case.

ORGANISATIONAL SUPPORT

Perceived organisational support was significantly correlated with organisational commitment, ranking second. This supports the findings of Meyer et al (2002), who also noted the importance of perceived organisational support over other work experiences, as well as Giauque et al (2010) who found similar correlations. Perceived organisational support relates directly to how a person feels about an organisation, and the scale included questions related to the extent to which the person feels like the organisation cares for and values them. It therefore seems logical that it would correlate strongly with a person's commitment to the organisation. As Meyer et al (2002) explained, to obtain committed employees an organisation needs to demonstrate its own commitment.

Organisational support showed some variability across the control variables, with higher correlation with organisational commitment for older employees, even though the means for both parameters were almost the same for the two age groups. The correlation between organisational support and organisational commitment was also higher for senior employees, again despite very similar means for both parameters between the two groups. Both differences suggest that seniority may influence the extent to which organisational support correlates with organisational commitment in knowledge workers, despite not influencing the actual levels of either.

OCCUPATIONAL COMMITMENT

Occupational commitment exhibited the strongest correlation of the antecedents with organisational commitment. Since KUTM was used to measure occupational commitment and the two sets of questions were fairly close together in the questionnaire, it seemed possible the answers given by respondents to KUTM items for organisational commitment were mirrored in their answers to KUTM measures for occupational commitment. To test this possibility, correlations were calculated between the questions of the two scales. In general, the strongest correlations were found between the corresponding questions in the two scales; however, there were significant correlations between all questions. In addition, none of these individual correlations were higher than the overall correlation between the average or final scores of each. This suggests that the similarity of the scales was not the main reason for the difference.

The correlation of occupational commitment with both commitment measures supports the findings of Lee et al (2000), Tam et al (2002), Vandenberg and Scarpello (1994), and Wallace (1993) who found correlations of various strengths between the two. As Lee et al (2000) explained, individuals who possess a strong psychological bond with their occupation are more likely to be satisfied within their organisation.

Literature also suggests that knowledge workers tend to exhibit stronger occupational than organisational commitment (Horwitz et al 2003; Tam et al 2002).

Exploring the results, the mean occupational commitment score of 4.31 was higher than the mean organisational commitment scores from both measures (4.08 and 3.49). Using the one-tailed t-test, it was found that this difference was significant. The results therefore support the findings in literature that occupational commitment levels in knowledge workers may be higher than organisational commitment levels.

As explained by Baugh and Roberts (1994), there is often a conflict between an engineer's commitment to his/her occupation - which requires a level of autonomy in applying his/her specialist knowledge - and the bureaucratic systems of an organisation which can result in lower organisational commitment. The difference in the results between the levels of commitment to the occupation and organisation seem to support Baugh and Roberts' (1994) assertions. However, the significant correlation between the two appears to contradict their findings.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Implications of findings

Organisational commitment has been consistently associated with a wide array of positive work outcomes, including improved motivation, job satisfaction, employee wellbeing and performance. Affective commitment has also been consistently linked with lower turnover intention. Knowledge workers have been shown to possess unique qualities which require tailored approaches in order to encourage organisational commitment and thus benefit from these positive work outcomes. This is important both for consulting engineering companies, whose businesses are built around knowledge workers, and for South Africa as a whole, being reliant on engineers for infrastructure development.

Organisational commitment was found to be significantly positively correlated with perceived organisational support, satisfaction with pay and autonomy. This suggests that organisations can encourage commitment in engineers by creating an environment in which employees feel valued, cared for and supported by the organisation. This could include aspects such as active listening and encouraging work-life balance (Giauque et al 2010) or simply creating a supportive environment in which employees feel that help is available when it is needed. The importance of autonomy and freedom to plan and execute work has once again been emphasised through this study. Furthermore, ensuring that knowledge workers are well compensated and that fair pay is administered appears to be important in the consulting engineering environment, despite the contradictory evidence in previous literature (Benson & Brown 2007).

Considering the particularly strong correlation between occupational and organisational commitment, it may be worthwhile to consider incorporating interview questions aimed at establishing a candidate's level of occupational commitment when recruiting potential employees, as more occupationally committed employees tend to be more organisationally committed. Organisations might also consider ways to promote occupational commitment. Some possibilities include efforts to encourage postgraduate studies (which seemed to have an influence on the strength of the correlation), support towards professional registration, offering opportunities to work on challenging and interesting projects, and good technical mentorship.

Limitations and recommendations for further research

The study was cross-sectional and therefore no inferences could be made regarding causation between the constructs. In prior work on the topic, very few longitudinal studies have been undertaken. Thus, a longitudinal study would be a good area for future research, with the aim of establishing the causative relationships between organisational commitment and its antecedents.

The research was only performed at one firm, meaning that the sampling technique was non-random. A wider sample, using random sampling techniques, could possibly be more representative of the population and might allow for more meaningful inferences to be made. As the sampled organisation was a large multinational consulting engineering firm, future research could consider firms of different sizes as this might affect the parameters studied. In addition, only a selection of commitment antecedents was tested; however, there are several others that could be important for knowledge workers.

The use of self-reported measures in this study might have resulted in common method bias; however, self-reported measures are widely used for measuring employees' perceptions since they are likely to be more accurate. Finally, a mixed methods study incorporating qualitative research may be of value in terms of better understanding what feelings and emotions underpin the quantitative results.

Conclusion

This research explored factors that influence knowledge worker organisational commitment in the South African consulting engineering environment, makes a novel theoretical contribution using the KUTM scale, and adds to a growing body of literature on the topic. Fair and competitive pay, freedom and autonomy, supportive work environments, and occupational commitment were found to be important influencing factors. These insights can guide managers towards encouraging engineers' organisational commitment, and in turn, ensure their willingness to stay at the organisation. This knowledge could therefore contribute to the retention of engineers, critical for both maintaining a thriving engineering profession and for supporting South Africa's development needs.

REFERENCES

Allen, N J & Meyer, J P 1990. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organisation. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1): 1-18. [ Links ]

Ashforth, B E, Joshi, M, Anand, V & O'Leary-Kelly, A M 2013. Extending the expanded model of organizational identification to occupations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(2013): 2426-2448. [ Links ]

Bagraim, J J 2004. The improbable commitment: Organizational commitment amongst South African knowledge workers. PhD Thesis, Coventry: University of Warwick, UK. Available at: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/1204. [ Links ]

Baugh, S G & Roberts, R M 1994. Professional and organisational commitment among engineers: Conflicting or complementing? IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 41(2): 108-114. [ Links ]

Becker, T E, Klein, H J & Meyer, J P (Eds) 2009. Commitment in Organizations: Accumulated Wisdom and New Directions. New York: Routledge, pp 419-447. [ Links ]

Benson, J & Brown, M 2007. Knowledge workers: What keeps them committed; what turns them away. Work, Employment and Society, 21(1): 121-141. [ Links ]

Bryman, A & Bell, E 2015. Business Research Methods, 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

CESA (Consulting Engineers South Africa) 2016. Bi-Annual economic and capacity survey: July-December 2015. Available at: http://www.cesa.co.za/sites/default/files/CESA_BECS_Report_Dec15.pdf(accessed on 23 August 2016. [ Links ]

Chen, X P 2005. Organisational Citizenship Behaviour: A Predictor of Employee Voluntary Turnover. New York: Nova Science. [ Links ]

Dachner, A M & Miguel, R 2015. Job crafting: An unexplored benefit of friendships in project teams. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 80(2): 13-21. [ Links ]

Egan, T M, Yang, B & Bartlett, K 2004. The effects of organisational learning culture and job satisfaction on motivation to transfer learning and turnover intention. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 15(3): 279-301. [ Links ]

Eisenberger, R, Cummings, J, Armeli, S & Lynch, P 1997. Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(5): 812-820. [ Links ]

Giauque, D, Resenterra, F & Siggen, M 2010. The relationship between HRM practices and organisational commitment of knowledge works: Facts obtained from Swiss SMEs. Human Resource Development International, 13(2): 185-205. [ Links ]

Hackman, J R & Oldham, G R 1975. Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2): 159-170. [ Links ]

Heneman, H G & Schwab, D P 1985. Pay satisfaction: Its multidimensional nature and measurement. International Journal of Psychology, 20: 129-141. [ Links ]

Horwitz, F M, Heng, C T & Quazi, H A 2003. Finders, keepers? Attracting, motivating and retaining knowledge workers. Human Resource Management Journal, 13(4): 23-44. [ Links ]

Jayasingam, S, Govindasamy, M & Singh, S K G 2016. Instilling affective commitment: Insights on what makes knowledge workers want to stay. Management Research Review, 39(3): 266-288. [ Links ]

Jayasingam, S & Yong, JR 2013. Affective commitment among knowledge workers: The role of pay satisfaction and organization career management. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(30): 3903-3920. [ Links ]

Kinnear, L & Sutherland, M 2000. Determinants of organisational commitment amongst knowledge workers. South African Journal of Business Management, 31(3): 106-112. [ Links ]

Klein, H J, Molloy, J C & Brinsfield, C T 2012. Reconceptualising workplace commitment to redress a stretched construct: Revisiting assumptions and removing confounds. Academy of Management Review, 37(1): 130-151. [ Links ]

Klein, H J, Molloy, J C & Cooper, J T 2009. Conceptual foundations: Construct definitions and theoretical representations of workplace commitments. In Klein, H J, Becker, T E & Meyer, J P (Eds). Commitment in Organizations: Accumulated Wisdom and New Directions. New York: Routledge, pp 3-36. [ Links ]

Klein, H J, Cooper, J T, Molloy, J C & Swanson, J A 2014. The assessment of commitment: Advantages of a unidimensional target-free approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(2): 222-238. [ Links ]

Lee, K, Carswell, J J & Allen, N J 2000. A meta-analytic review of occupational commitment: Relations with person- and work-related variables. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5): 799-811. [ Links ]

Malhotra, N, Budhwar, P & Prowse, P 2007. Linking reward to commitment: An empirical investigation of four UK call centres. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(12): 2095-2127. [ Links ]

Meyer, J P 2009. Commitment in a changing world of work. In Klein, H J, Becker, T E & Meyer, J P (Eds). Commitment in Organizations: Accumulated Wisdom and New Directions. New York: Routledge, pp 3-36. [ Links ]

Meyer, J P & Allen, N J 1991. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1): 61-89. [ Links ]

Meyer, J P & Herscovitch, L 2001. Commitment in the workplace. Toward a general model. Human Resource Management Review, 11(2001): 299-326. [ Links ]

Meyer, J P, Stanley, D J, Herscovitch, L & Topolnytsky, L 2002. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1): 20-52. [ Links ]

Nazir, S, Shafi, A, Qun, W, Nazir, N & Tran, Q D 2016. Influence of organisational rewards on organisational commitment and turnover intentions. Employee Relations, 38(4): 596-619. [ Links ]

Nuzzo, R 2014. Statistical errors: P values, the 'gold standard' of statistical validity, are not as reliable as many scientists assume. Nature, 506(7487): 150. [ Links ]

Solinger, O N, Van Olffen, W & Roe, R A 2008. Beyond the Three-Component Model of Organizational Commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1): 70-83. [ Links ]

Tam, Y M, Korczynski, M & Frenkel, S J 2002. Organisational and occupational commitment: Knowledge workers in large corporations. Journal of Management Studies, 39(6): 775-801. [ Links ]

Vandenberg, J & Scarpello, V 1994. A longitudinal assessment of the determinant relationship between employee commitments to the occupation and the organisation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(6): 535-547. [ Links ]

Wallace, J E 1993. Professional and organizational commitment: Compatible or incompatible? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 42(1993): 333-349. [ Links ]

Watermeyer, R & Pillay, M 2012. Strategies to address the skills shortage in the delivery and maintenance of infrastructure in South Africa: A civil engineering perspective. Civil Engineering, 5(2012): 46-56. [ Links ]

Wegner, T 2016. Applied Business Statistics: Methods and Excel-based Applications, 4th ed. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

Zaiontz, C 2016. Real statistics using Excel. Available at: http://www.real-statistics.com. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

CATHERINE BLERSCH

Investment Analyst

Granate Asset Management

T: +27 72 603 7285

E: catherine.blersch@gmail.com

BEVERLY SHRAND

Senior Lecturer

UCT Graduate School of Business

T: +27 82 876 9430

E: beverly.shrand@gsb.uct.ac.za

LINDA RONNIE

Associate Professor

UCT School of Management Studies

T: +27 21 650 2256

E: linda.ronnie@uct.ac.za

CATHERINE BLERSCH Pr Eng has a Master's degree in engineering, as well as an MBA. She worked for eight years at Aurecon as a professional engineer and associate, responsible for planning, design and implementation of wastewater treatment works projects across southern Africa. She then spenttwo years running her own consultancy, Splice Consulting, which aimed to bring together key role players in the public and private sector to develop creative solutions to some of the major challenges in the engineering industry. In 2020 she changed direction again, and is now an Investment Analyst at Granate Asset Management.

DR BEVERLY SHRAND is a senior lecturer at the University of Cape Town's Graduate School of Business (GSB). She held several management positions in the private sector before embarking on her MBA as a mature student. Thereafter she gradually transitioned into academia where her work focuses primarilyon systems thinking and organisational psychology. Beverly is currently the academic director of a new international Master's programme being launched at the GSB, in addition to convening and teaching on various executive education management development programmes across all levels of management and spanning a broad spectrum of industry.

PROF LINDA RONNIE (PhD) is Associate Professor in Organisational Behaviour and People Management. Her research and teaching focus on a wide range of people management topics, including organisational culture, recruitment and selection, motivation and teamwork, and managing change. She has consulted to both private and public sectors on improving employee-employer relationships. A committed and enthusiastic management educator for over 20 years, she holds the prestigious UCT Distinguished Teacher's Award, is the award-winning co-author of the Best 2015 AABS/Emerald Case Study, and Best Paper Award from the 2019 Actuarial Society of South Africa Convention.

1 Pseudonym used to protect company confidentiality.

2 Actual name changed back to the generic form at the company's request.