Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering

On-line version ISSN 2309-8775

Print version ISSN 1021-2019

J. S. Afr. Inst. Civ. Eng. vol.60 n.4 Midrand Dec. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8775/2018/v60n4a3

TECHNICAL PAPER

The relationship between project performance of emerging contractors in government infrastructure projects and their experience and technical qualifications

F T Muzondo; R T McCutcheon

ABSTRACT

Various studies have been conducted to investigate the reasons for the comparative failure of small contractors. Many of these studies have found the reasons for failure to be primarily related to factors that are beyond the control of the contractor or business management. Little attention has been paid to technical factors. This study sought to investigate the correlation between the performance of emerging contractors in government infrastructure projects to their technical qualifications and experience. An archive research methodology was adopted where contractor performance information was collected on 30 CE and GB projects conducted in Mpumalanga Province. The project data was then used alongside contractor qualification and experience data to investigate their relationship. When evaluating the qualification level, it was found that contractors with higher qualifications show better performance. It was also found that contractors with more technical qualifications perform better than those without. This study also concluded that contractors with more years of experience in the construction industry show better project performance. It is recommended that a much broader investigation must be carried out to examine to what extent these conclusions are applicable throughout South Africa. If so, there are important implications for the modification of existing procurement policy and procurement practice.

Keywords: Emerging contractors, technical competence, experience, project performance, policy

INTRODUCTION

Economic development can be measured by the physical development of infrastructure such as bridges, roads and buildings, and job creation (Alzahrani & Emsley 2013), which are mainly offered by the civil engineering and general building construction sectors. Emerging contractors, or "small, medium and micro enterprises" (SMMEs), are essential for job creation and poverty alleviation in African countries (Tushabomwe-Kazooba 2006; Okpara & Wynn 2007; Okpara & Kabongo 2009).

Therefore, the development of emerging contractors contributes to the development of South Africa. Given that the primary client of these contractors is the government (CIDB 2011a), there is a need to investigate their project performance in government infrastructure projects.

It is evident that there are a number of performance measures, and it may be that not all can be used to measure performance in a particular project. As such, it is conceivable that each project would have measures appropriate to its goals. Determining project goals and the indicators to be used to measure project performance is vital to assessing and quantifying project performance. This then forms a basis for determining the factors that affect project performance. Many studies have been conducted to determine the factors that affect contractor performance in developing countries (Sweis et al 2014). A study done by Faridi and El-Sayegh (2006) in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) shows that shortage of skilled labour, poor supervision and site management, inadequate leadership and equipment failure have contributed to delays in construction projects. According to Hanson et al (2003) contractor project performance in South Africa is affected by poor workmanship and contractor incompetence, while Gharakhani et al (2013) found that reputation affects client satisfaction and, therefore, perceived contractor performance.

This research was conducted to explore the relationship between technical qualifications and experience of contractors within the construction industry, specifically in the South African public sector and contractor project performance. The investigation was conducted in Mpumalanga Province with 30 public sector projects carried out by CE and GB contractors from CIDB grades 1 to 7. This research, therefore, argues that in projects, performance is directly related to the technical competence of the contractors and their level of experience in the construction industry. It is expected that, in order for an emerging contractor to develop on a business level, there is a need to perform at the project level (Mohlala 2015). Completion of a project in the specified time is considered to be a major criterion for the measurement of project success (Rwelamila & Hall 1995), which measurement was used in this research to assess project performance of emerging contractors.

LITERATURE REVIEW

A literature survey was conducted with the aim of finding out what work had been done in the area of emerging contractor performance in public sector projects, with attention drawn to the South African context. The literature was analysed in order to answer the first primary research question, which is: What are the factors that affect emerging contractor performance in government infrastructure projects? The secondary objective was to establish the limitations of previous work done in the study area in order to establish a methodology for the empirical study.

Success rate of emerging contractors

Small businesses, or SMMEs such as emerging contractor companies, contribute significantly to economic growth and job creation in South Africa (Van Eeden et al 2003). The SMME sector contributes approximately 67% of employment opportunities in South Africa (DTI 2004). According to Pretorius (2009), 50-90% of South African small businesses fail, 32% of which fail in the first seven years of operation (Nemaenzhe 2010). Small business failure can result in financial losses (Shepherd et al 2009), loss of resources (Peacock 2000) and job losses (Argenti 1976; Van Witteloostujin 1998; Temtime & Pansiri 2004). The high failure rate of SMMEs in South Africa is of great concern.

For economic growth purposes in South Africa, emerging contractor businesses should perform on a project and business level. Key performance indicators need to be identified and defined in order to evaluate emerging contractor performance. The outcome will then be used to develop recommendations for improving contractor project and business performance in order to aid sustainable development.

Definition of "emerging contractor"

There is no general definition of an emerging contractor (Storey 1994; Eyiah 2001). In the South African context, an "emerging contractor" can be defined as a "person or enterprise which is owned, managed and controlled by previously disadvantaged persons and which is overcoming business impediments arising from the legacy of apartheid" (CIDB 2011b). These enterprises are also termed "small construction enterprises" and "small-scale contractors". Emerging contractors are generally characterised by limited capital resources, plant and equipment, and managerial support, all of which affect their ability to acquire skilled labour and employ professionals (Eyiah 2001).

The CIDB does not classify them according to their financial capabilities (Mohlala 2015). As such, "emerging" is not necessarily a reflection of financial capability.

This study, therefore, defines "emerging contractors" as:

Small to medium contracting enterprises that are owned by individuals previously disadvantaged by the apartheid system of the pre-1994 South Africa and are registered with the CIDB.

Definition of "project performance"

Performance measurement is a systematic process of assessing and quantifying past behaviours and activities (Neely 1998). Project performance measurement is essential in order to determine whether or not project goals have been met for both the client and the contractor. A study conducted by Cheung et al (2004) found that there are seven main key performance indicators, which include time, cost, quality, client satisfaction, client changes, business performance, and health and safety. According to the CIDB, project performance can be measured against the management of time, cost, quality, health and safety, site and sub-contractors (CIDB 2013).

Thus, project performance can be defined as the actions taken through the life cycle of a project to meet predetermined goals. These goals may be one of the seven key performance indicators identified by the CIDB (2013), those proposed by Cheung et al (2004), or a combination thereof.

Factors related to project performance

According to Van Wyk (2003), Mbande (2010) and Milford (2010), one of the challenges facing the South African construction industry is the lack of institutional capacity within the public sector or government organisations. Operational skills which include project management and business skills such as planning and financial accounting are crucial for the success of a business (Thwala & Mvubu 2005). Mofokeng (2012) also found that small and medium construction companies lack business and managerial experience. Previous literature (Fredland & Morris 1976; Yusoff 1995; Jo & Lee 1996; Lin 1998; Jaafar & Abdul-Aziz 2005) has shown that managerial expertise and experience are vital for the success of an enterprise and have a significantly positive relationship to the performance of the enterprise. According to Croswell and McCutcheon (2001), some of the difficulties facing emerging contractors include lack of entrepreneurial, managerial, technical and administrative expertise.

Much of the literature related to contractor performance and the challenges facing the South African construction industry in general focus on the business and financial functions, with some also citing clients (government organisations) as a challenge. However, not much emphasis is placed on the technical aspect. Even though it is mentioned in the study conducted by Croswell and McCutcheon (2001), not many studies in South Africa have conducted an in-depth investigation on the importance of the technical aspect. It has, however, been explored on an international level, as presented in the sections below.

Emerging contractor competencies

Sweis et al (2014) conducted a study on contractor performance at an international level in order to determine the most critical contractor performance factors in public infrastructure projects according to the perspectives of contractors, clients and engineers. It was found that the most common factors affecting contractor performance are related to the contractors' ability to perform the work, that is, contractor competence. It should be noted that, due to the uniqueness of projects, it is difficult to generalise these factors. These findings do, however, form a basis for the need to assess contractor performance in the South African public sector.

Competence can be defined as the ability or potential to perform a particular task or job effectively (Rozewski & Malachowski 2009) or the capacity to perform a given activity (Guillaume et al 2014) to achieve a predetermined goal to a particular standard (Peters & Zelewski 2007). This involves the application of knowledge and skills and is likely to vary from one organisation or contractor to the next (Guillaume et al 2014). It is clear that competence should involve not only the ability to perform a given task, but the application of the necessary skills and knowledge which are acquired before the given task. This is an indication that there may be a need to assess the level of emerging contractor competence before the awarding of every contract, as it may affect the performance during the construction phase of the project.

According to Hanson et al (2003), contractor performance in South Africa is affected by poor workmanship and contractor incompetence. This affects the contractor's track record or reputation and, therefore, the eligibility for future contracts. Gharakhani et al (2013) found that reputation affects client or customer satisfaction. Relevant skills and expertise are vital for emerging contractors' performance through the life cycle of a project, and from one project to the next. The acquisition of competence is thus an on-going process, especially in project-based enterprises (i.e. emerging contractor businesses), since each project is inherently unique. Thus, emphasis should also be put on continuous learning from one project to the next in order to improve emerging contractor competence in government infrastructure projects.

Technical qualifications and experience

A study by Sweis et al (2014) found that clients and engineers attribute contractors' poor performance to lack of technical professionals within their organisations. According to a study conducted in Germany, a combination of vocational training and formal qualifications is a great strength of the German construction labour force (Richter 1998). It was also found that Germany has a high number of technically qualified construction workers even up to Master's level. According to Richter (1998), this is the support system and essential factor for entrepreneurship and self-employment in the German construction industry. The lack of technically qualified contractors was found to be the primary cause of low productivity in the United Kingdom (UK) construction industry (Prais & Steedman 1986; Clarke & Wall 1996). Croswell and McCutcheon (2001) also identified the lack of technical expertise as a contributory factor to the poor performance of emerging contractors.

These studies highlight the importance of technical qualifications and experience in the construction industry. Most literature in the area of emerging contractor performance concentrate on financial and project management competencies. However, this section suggests that technical qualifications and experience contribute to performance. In addition, to ensure sustainability, institutions and construction companies should pass on their skills, knowledge and experience through training of incoming members into the industry (Richter 1998). This can be achieved by collaboration between the government (public sector) and the private sector. Richter (1998) also highlights the importance of training, and its relationship with competence and experience in the construction industry.

Project delays

Project delays or timely completion of projects can be used as another indicator of emerging contractors' project performance. It should be noted that not all delays are a reflection of a contractor's competence, project management skills and performance. It is important to investigate the different causes of construction delays in order to determine the causes. The causes of project delays that are attributed to the contractor's actions or lack thereof can then be used to determine the solutions that can be used to limit such delays and, as a result, improve contractor performance. Project delays that are attributed to government organisations (the client) and the built environment professionals (engineers, consultants and the client's agents) should also be noted.

Faridi and El-Sayegh (2006) found that the most prevalent causes of project delays, as ranked by consultants and contractors in the UAE, are inadequate early planning of projects, preparation and approval of drawings, poor supervision and site management, and shortage of manpower. The lowest ranking causes from the same study were found to be shortage or delays in delivery of materials, poor leadership of the construction manager or project manager, incomplete drawings, specifications or documents and productivity of manpower. Similar studies were done by Assaf et al (1995), and Mezher and Tawil (1998) in Saudi Arabia and Lebanon, respectively. According to Mezher and Tawil (1998), the most common causes of project delays include poor leadership of construction or project management, and preparation and approval of drawings. Assaf et al (1995) concluded that project delays in the construction industry are closely related to availability and productivity of manpower, which are linked to skills and competencies of contractors. Skills and competencies in the construction industry place contractors in a better position for getting work and, as a result, experience. This supports the proposition that successful contractor performance in South Africa is linked to skills, competencies and experience; a factor that has been given much attention in the construction industry.

Project delays can lead to cost overruns (Sambasivan & Yau 2007), low productivity, contract termination (Arditi & Pattanakitchamroon 2006) and hinder business development for the contractor (Benson 2006). According to Arditi et al (1985) and Lo et al (2006), project delays can lead to slow economic growth since, according to Adnan et al (2012), the construction industry plays a major role in infrastructure development and, therefore, the growth of the economy.

It can be argued from the above studies that have been conducted around the subject of emerging contractor performance that very little work has been done to find out whether there is a correlation between contractors' project performance, contractor experience and technical qualifications. This investigation is aimed at finding the relationship between emerging contractors' project performance in public sector projects, and their qualifications and experience in Mpumalanga Province.

Methodology

A literature review was performed in order to clearly state and substantiate the problem, which is that there is generally low performance of emerging contractors in the public sector (Zulu & Chileshe 2010). The literature review was used to determine the causes of low performance or failure of emerging contractors in government infrastructure projects. The body of knowledge helped to define "emerging contractor" and "performance" and this helped to determine the gaps in literature, the types of questions not addressed by literature and the type of empirical data that was collected in order to address the unanswered questions.

An archival research methodology was utilised to collect the empirical data used for this research, where contractor performance information based on 30 CE and GB projects conducted in Mpumalanga Province between 2011 and 2013 was collected. One of the advantages of this research method is that it allows for collection of data that spans over a long period of time, and allows for a broader view of trends. This study also acknowledges the disadvantages of using archival data, one major one being that the researcher has no control over how the data was archived, and as such, data may be incomplete and may fail to address certain issues. This implies that the findings in this study cannot be regarded as generalisable to all contractors in South Africa, thus recommending that further study be done on a larger scale involving projects in the whole country.

A positivist philosophy was used for this research, and focused on the factors of failure and success of emerging contractors in government infrastructure projects in the South African construction industry. The study was based on facts from the body of knowledge and from the empirical data that was collected. The research statements propose that project performance is related to technical qualifications and experience prior to a particular project.

A qualitative approach was used for the collection of data in order to study the indicators of performance and factors affecting performance of emerging contractors in government infrastructure projects. "Qualitative data sources include observation and participant observation (fieldwork), interviews and questionnaires, documents and texts, and the researcher's impressions and reactions" (Myers & Avison 1997).

Data collection

The data was collected in two parts and was project-based. Part 1 of the empirical data was collected from the database of one of the government organisations (in Mpumalanga Province) that run projects which require the appointment of CE and GB registered contractors. This data included tender and project documents, and contractor contact details. The data collected in Part 1 was also used to quantitatively represent and analyse the performance indicators.

The contact information gathered from Part 1 was used to contact the contractors to gather Part 2 of the data, which included Curriculum Vitae (CVs) and company profiles. This was then used to confirm what was proposed in the research statements (i.e. determine whether or not there is a relationship between project performance and experience and technical qualification).

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

Description of data

Data on thirty projects that were conducted between 2011 and 2014 was collected, representing a total of 25 contractors. An email was sent to these 25 contractors requesting their company profiles and the CVs of the core staff of the company (mainly the owner). Contact details, CIDB grades, payment and completion certificates, and project start and completion dates were collected for all 30 projects. Therefore, 100% of Part 1 of data collection was collected. A total of 64% of the 25 contractors responded to the request to submit their CVs and company profiles for Part 2.

Project performance

The four most commonly used project performance indicators are time, cost, quality and client satisfaction (Harrison & Lock 2004; Turner 1999; Cheung et al 2004). The four indicators were evaluated in relation to the government institution under study in order to determine which would be the most suitable indicator for this study. Mohlala (2015) found that:

■ The government institution under study does not impose penalties that result in financial losses for the contractor and the contractors generally to complete their work within the tendered amount. Therefore, there are rarely any cost overruns, and as such, cost could not be used as a measure of project performance.

■ The engineers from the government institution conduct quality checks throughout the life cycle of each project. It is, therefore, assumed that all projects that were completed attained the quality standards and client satisfaction measures. This then ruled out lack of quality and client dissatisfaction.

■ The beneficiaries of the government infrastructure projects sign a completion certificate at the end of every project as an indication of satisfaction and agreement of all work done by the contractor. Thus, the presence of a completion certificate usually indicates client and beneficiary satisfaction.

■ Timely completion of projects is commonly regarded as the major indicator of project success (Rwelamila & Hall 1995).

Although cost and quality are considered to be two of the most important components of project management, for the reasons given above they were not used in the study as measures of project performance. However, it was possible to investigate the "time factor" in greater detail.

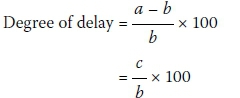

Mohlala (2015) developed the following approach for a deeper consideration of "time". In order to assess project performance, that is the timely completion of projects, which is the performance indicator used in this research, the degree of delay was calculated. This provides a uniform measure for performance and allows for comparison of the different contractors and projects with different construction periods. The degree of delay (DoD) is calculated as a percentage over the specified construction period as follows (Mohlala 2015):

Where

a = actual construction period

b = specified construction period

c = time overrun

For example, the DoD for a three-month project that took six months to complete is:

that is, the project went over the specified construction period by 100% (three months in this case)

To further explain this factor, projects that have a DoD of zero (0%) are projects that have been completed on time (within the specified construction period).

For projects that were incomplete or had been abandoned at the time of data collection, the delay period and degree of delay are represented by the symbol °°.

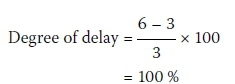

Figure 1 shows that only 10% of the projects had a DoD of less than 50%. Figure 1 also shows that 30% of the projects had a DoD that falls between 51% and 100%.

Thus, 60% of the contractors exceeded the specified construction period by over double the time.

The latter, together with the fact that 27% of the projects have a DoD of over 200% and that 16% of the projects did not even reach a commissioning or close-out stage (DoD is °°), shows that project performance in government infrastructure projects is a cause for concern.

This research is aimed at exploring and demonstrating the relationship between project performance and the contractors' technical qualifications and experience. Therefore, the projects that have a DoD range of 0-50% need to be studied at great length and compared to the projects with a higher DoD.

Contractor educational profile

The highest qualifications within the organisation were extracted from the CVs that had been gathered from the respondents (i.e. the highest qualifications of the core staff).

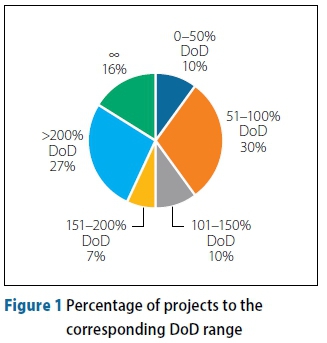

Figure 2 shows the proportions of the qualification bands as the percentage of the respondents.

A total of 34% of the contractors have National Certificate qualifications from institutions such as FET colleges. It was found that some of the respondents had university degrees; those who went to university either attained diplomas, honour's degrees or honour's equivalent. This means that none of the respondents attained qualifications between diploma level and honour's level. Honour's equivalent degrees are four-year degrees, such as engineering, whereby one can continue from that degree level to a master's degree.

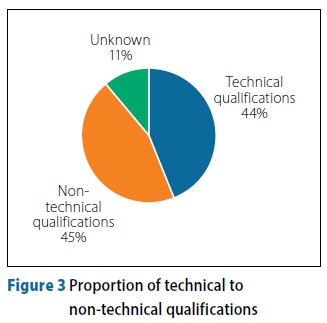

Figure 3 shows the proportion of respondents who have qualifications that are in the technical or construction fields to those with non-technical qualifications.

The qualifications shown on the CVs received from the respondents were divided into two types - technical and non-technical qualifications. The technical qualifications that were found were in the civil and agricultural engineering, quantity surveying, instrumentation and construction fields.

Relationship between qualifications and project performance

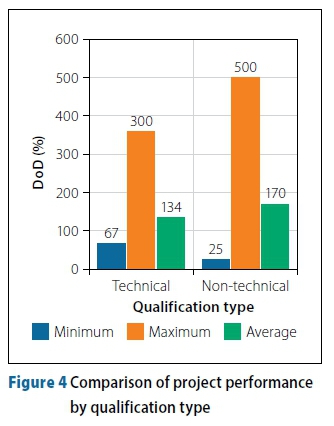

Further investigation was carried out to determine the relationship between the types and levels of qualification, and project performance. For analysis, the minimum, maximum and average DoDs for the different types of qualifications and qualification bands were compared.

Qualification type and project performance

The results show that projects with the highest DoD and uncompleted projects were undertaken by contractors with non-technical qualifications. This supports the initial proposition that the possession of technical qualifications will result in better project performance when compared to contractors with non-technical qualifications.

Figure 4 shows that project performance improves with the possession of technical qualifications within the organisation.

The study found that the lowest DoD in the results was from a project undertaken by a contractor with a non-technical qualification. However, this may be an indication that project success requires a number of factors or prerequisites, which this study recommends for further investigation. The maximum and average DoD from contractors with technical qualifications are both lower than those of contractors with nontechnical qualifications. This implies that, from the sample considered, on average or in general, contractors with technical qualifications perform better, in terms of time, than contractors without technical qualification.

Qualification level and project performance

The results show that the lowest qualification level (matric) has the poorest project performance and the highest qualification level shows better project performance. The results also show that the DoD decreases as qualification level increases, which shows that project performance improves with the acquisition of higher qualifications (as demonstrated in Figure 5).

Apart from technical qualifications, the level of qualifications is also essential for project performance. The possession of technical qualifications in the construction industry can be used as a measure or evidence of contractor competence.

It is worth noting that none of the respondents have any project management qualifications. This may be another reason for the poor performance of the contractors in all the projects they undertake.

Contractors' experience profile

Literature claimed that experience provides competence in the construction industry, even without formal qualifications. The type of experience and the years of experience are important measures of competence. It is assumed that CIDB grading is a measure of experience, since registration and progression from one grade to another requires evidence of previous work done (CIDB 2011a). This research, therefore, compares the project performance of contractors by CIDB grades as well. This also supplements the data where contractors' CVs are not available, since the CIDB grading of all contractors were collected from the CIDB website.

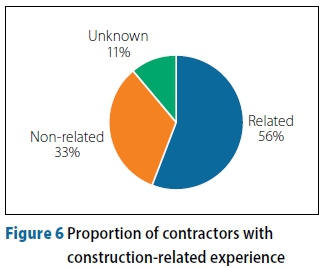

Figure 6 shows the proportion of contractors with staff who have experience in construction-related fields to those who do not.

The construction-related positions that were held by the core staff of the company before establishment or joining of the respective contractor companies were considered. The construction-related fields were civil engineering, agricultural engineering, site management and site supervision. Other contractors and their core staff worked in other fields that are not related to the construction industry, which were found to be teaching, sales, administration, customer services, and public relations.

Relationship between experience and project performance

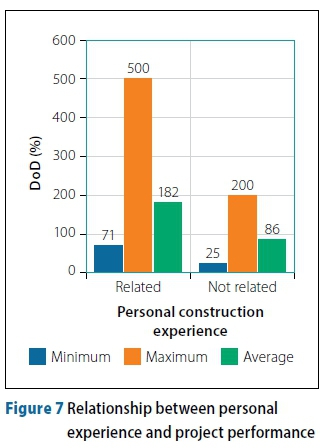

Personal experience and project performance

It was expected that contractors with a staff complement who have personal experience in the construction industry will generally show better project performance. The results, however, do not reflect that.

Figure 7 demonstrates the relationship between personal experience and project performance. Further analysis was done to determine the reasons why the results contradicted the initial expectation. This was done by comparing the experience of the contractors' staff complement to the contractors' qualifications per project.

The maximum DoD observed from the contractors with staff who have construction-related experience is greater than 500% with some incomplete projects. These contractors were also found to have no technical qualifications. This may be the reason for the poor performance and may mean that technical qualifications are more critical to project performance than personal experience. This assumption is, however, tentative and requires further investigation of other factors that affect project performance, which were outside the scope of this research.

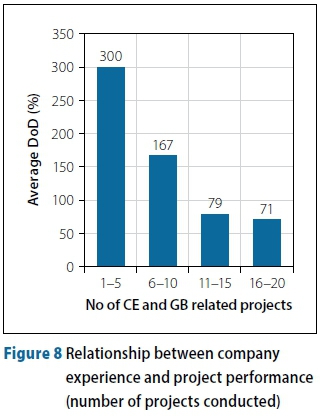

Company experience and project performance

Business experience is necessary to build competence; it also builds client confidence in the ability of the business to achieve pre-set goals. This research explored the relationship between emerging contractors' business experience and project performance. Projects undertaken by the respondents were evaluated to determine the types of projects each business has undertaken in the civil engineering and general building-related fields.

Figure 8 shows the relationship between contractors' company experience in CE and GB projects, in terms of number of projects conducted, to project performance.

The results show that companies which have undertaken more projects have lower DoDs and, therefore, better project performance. This supports the initial proposition that the experience of the construction company as a business or organisation in construction-related fields prior to a particular project will result in better performance in that project. Further analysis was carried out, and it was found that the contractor with the highest number of CE and GB-related projects (19 projects) has the lowest DoD and has a staff complement with technical qualifications. This further demonstrates the importance of the combination of qualifications and business experience.

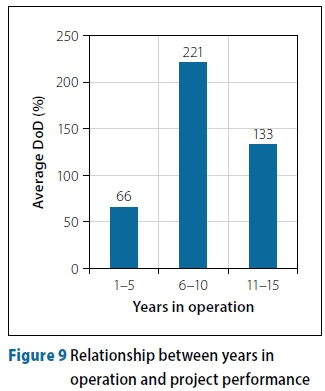

Years in operation and project performance

The number of years that the contractor has been in operation in the industry may also be used as a measure of experience. The relationship between the number of years in the industry and project performance was investigated in order to determine whether or not the same results that are represented in Figure 8 would be observed. However, a different result was found, as represented in Figure 9.

The results show that the number of years in the industry do not necessarily result in better project performance. Further investigation was done to find out why this is. It was found that the lowest DoD was achieved by the contractor with a staff complement with technical qualifications. This may be the reason for the above results. This contractor also had the second highest number of CE and GB-related projects, 15 in total. It may, therefore, be said that the number of projects conducted is more important, or adds more value, than the number of years in operation. The number of projects undertaken and implemented develops more competence than the number of years the business has been in the construction industry. However, it would also be expected that the longer the company is in operation, the more projects they would be conducting. Since the average DoD of contractors with one to five years' experience was predominately lowered by one Grade 7 contractor, a larger data sample would allow for a more reliable conclusion to be drawn.

CIDB grade and project performance

An investigation was carried out to test the assumption that the CIDB grading is a reflection of company experience and, therefore, the higher the grading the better the project performance. The highest CIDB grading was selected for contractors registered under both GB and CE categories. The results do not reflect a clear relationship. It was found, however, that the projects that were conducted by contractors who fall under CIDB Grade 1 generally had high DoDs and had projects that were incomplete. For the lowest DoD, 25% was achieved by a CIDB Grade 7 contractor. The result may be due to the use of an average and may only be reflecting the fact that there are more Grade 1 contractors than the higher grades. The number of respondents in each grade may also be too small to draw a conclusion on this.

Figure 10 highlights the relationship between the CIDB grading and contractor project performance.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Conclusion

From the studies that have been conducted around the subject of emerging contractor performance, it may be argued that very little research work has been carried out to determine the correlation between contractor performance, and contractor experience and qualifications, especially in the South African context. This investigation was aimed at finding the relationship between emerging contractor project performance in public sector projects and their qualifications and experience.

Project information was collected along with the respective contractors' experience and the qualifications of the key personnel of the respective emerging contractor organisations. A comparison was then made between contractors with shorter delays to those with significantly longer delays. It was concluded that contractors with relevant construction experience and technical qualifications experience shorter to no delays in projects - therefore, better project performance.

Contractors with no experience and qualifications show poor performance when measured against the time factor. It was also found that, where technical qualifications are lacking, higher education in any other field is an advantage to project performance. The number of construction-related projects undertaken and implemented by the contractor is a better measure of experience, promotes competence and, therefore, aids better project performance.

There is a definite need to develop contractor development programmes that will focus on improving emerging contractors' project performance. Such programmes should focus on developing the technical qualifications and skills of contractors and provide construction experience. It is further recommended that contractors who have participated in such programmes should be given preference in the tendering and procurement processes.

Lastly, the technical capacity and competence of contractors, along with their experience, should be evaluated during the selection process and, as such, contractors should be appointed on the basis of their technical ability to "do the job". The authors acknowledge that the research was solely based on the project information that was collected and, as such, conclusions should not be generalised across all contractors in South Africa without further study on a larger scale and, in addition, an investigation of other factors that determine project success which were outside the delineation of this study. In addition, due to the sample size and the fact that the data was collected from a single government department, the data should also not be considered as a general representation of contractors in the Mpumalanga Province.

Recommendations

Tendering and procurement process

This research found that all 30 projects under investigation had been delayed, showing poor project time performance. This may be evidence that the time that is specified for completion of the work by the client's engineers or consultants during the design and tendering stage is insufficient. It is, therefore, recommended that government organisations revise the specified construction period during the tendering stage or revise the criteria used to set the period.

Policy

Procurement policy should be amended such that the appointment process favours contractors with technical qualifications and experience in the construction industry. It may be beneficial that highly technical projects be reserved for experienced contractors. Contractors with no experience should also be encouraged to enter into joint-ventures with experienced contractors for highly technical projects in order to develop their skills. However, this is no substitute for the need for contractors to develop their technical skills.

The qualifications that need to be focused on are those of the core staff of the business. Experience may be that of the staff in the business or the overall business experience. This also means that the number of projects undertaken and implemented by the company should weigh heavier when appointing contractors than the number of years their business has been in the construction industry.

Collaboration

Government organisations that participate in public procurement and the use of emerging contractors along with private sector clients and practitioners should collaborate in developing standards and codes of practice for the construction industry. This collaboration may also require the involvement of statutory bodies such as the CIDB, the Engineering Council of South Africa (ECSA), and the South African Council for Project and Construction Management Professions (SACPCMP).

Project performance of emerging contractors should be recorded in order to evaluate compliance with best practice guidelines and standards. This information should then be shared across the board to ensure that all parties have an idea of the potential project performance of prospective contractors prior to appointment. This can also be used as part of the selection process during procurement in the public sector. A platform such as the CIDB may be used for such information. It should also be noted that the CIDB has recommended a similar approach in its 2012/2013 Annual Report (CIDB 2013).

Contracting companies

Emerging contractor companies that are already established should take advantage of the interventions of the CIDB and other training institutes in order to develop their technical knowledge. Contractors who wish to enter into the industry should seek to acquire higher education or tertiary qualifications, ideally in technical fields.

Recommendations for further study

■ Further study in this area is required on a bigger sample and on a broader scale (focusing on the whole of South Africa) in order for the results to be more generalisable.

■ A training programme needs to be developed for emerging contractors in the public sector. The programme needs to deal with the issues addressed in this paper and develop competencies that will ensure the success of emerging contractors.

■ The field of construction development in South Africa needs to be investigated in order to formulate "new" contractor development programmes aimed at improving the competencies, and therefore, the performance, of contractors on a more technical level.

REFERENCES

Adnan, H, Hashim, N, Yusuwan, N M & Ahmad, N 2012. Ethical issues in the construction industry: Contractor's perspective. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 32: 719-727. [ Links ]

Alzahrani, J I & Emsley, M W 2013. The impact of contractors' attributes on construction project success: A post construction evaluation. International Journal of Project Management, 31(2): 313-322. [ Links ]

Arditi, D, Akan, G T & Gurdamar, S 1985. Reasons for delays in public projects in Turkey. Construction Management and Economics, 3(2): 171-181. [ Links ]

Arditi, D & Pattanakitchamroon, T 2006. Selecting a delay analysis method in resolving construction claims. International Journal of Project Management, 24(2): 145-55. [ Links ]

Argenti, J 1976. Corporate planning and corporate collapse. Long Range Planning, 9(6): 12-17. [ Links ]

Assaf, S A, Al-Khalil, M & Al-Hazmi, M 1995. Causes of delay in large building construction projects. Journal of Management in Engineering, 11(2): 45-50. [ Links ]

Benson, R W 2006. Key issues for the construction industry and the economy. MidMarket Advantage, 16-18. [ Links ]

Cheung, S O, Suen, H C H & Cheung, K K W 2004. PPMS: A Web-based construction project performance monitoring system. Automation in Construction, 13(3): 361-376. [ Links ]

Clarke, L & Wall, C 1996. Skills in the Construction Process: A Comparative Study of Vocational Training and Quality in Social House building. Bristol, UK: Policy Press, University of Bristol. [ Links ]

CIDB (Construction Industry Development Board) 2011a. Guidelines for Contractor Registration. Available at: http://www.cidb.org.za/documents/kc/cidb_publications/brochures/brochure_contractor_registration_guidelines.pdf [accessed on 15 October 2014]. [ Links ]

CIDB (Construction Industry Development Board) 2011b. Framework: National Contractor Development Programme. Pretoria: CIDB. [ Links ]

CIDB (Construction Industry Development Board) 2013. Annual Report 2012/2013. Pretoria: CIDB. [ Links ]

Croswell, J & McCutcheon, R 2001. Small contractor development and employment - A brief survey of sub-Saharan experience in relation to civil construction. Urban Forum, 12(3): 365-379. [ Links ]

DTI (Department of Trade and Industry) 2004. Annual Review of Small Business in South Africa 2003. Pretoria: Department of Trade and Industry, Enterprise Development Unit. [ Links ]

Eyiah, A K 2001. An integrated approach to financing small contractors in developing countries: A conceptual model. Construction Management and Economics, 19(5): 511-518. [ Links ]

Faridi, A & El-Sayegh, S 2006. Significant factors causing delay in the UAE construction industry. Construction Management and Economics, 24(11): 1167-1176. [ Links ]

Fredland, E J & Morris, C E 1976. A cross-section analysis of small business failure. American Journal of Small Business, 1(1): 7-18. [ Links ]

Gharakhani, D, Sinaki, M T, Dobakhshari, M A & Rahmati, H 2013. The relationship of customer orientation, customer satisfaction, customer loyalty and innovation in small and medium enterprises. Life Science Journal, 10(6s): 684-689. [ Links ]

Guillaume, R, Houe, R & Grabot, B 2014. Robust competence assessment for job assignment. European Journal of Operational Research, 238(2): 630-644. [ Links ]

Hanson, D, Mbachu, J & Nkando, R 2003. Causes of client dissatisfaction in the South African Building industry and ways of improvement: The contractors' perspectives. Pretoria: CIDB. [ Links ]

Harrison, F L & Lock, D 2004. Advanced project management: A structured approach. Aldershot, UK: Gower Publishing. [ Links ]

Jaafar, M & Abdul-Aziz, A R 2005. Resource-based view and critical success factors: A study on small and medium sized contracting enterprises (SMCEs) in Malaysia. International Journal of Construction Management, 5(2): 61-77. [ Links ]

Jo, H & Lee, J 1996. The relationship between an entrepreneur's background and performance in a new venture. Technovation, 16(4): 161-211. [ Links ]

Lin, C Y Y 1998. Success factors of small-and medium-sized enterprises in Taiwan: An analysis of cases. Journal of Small Business Management, 36(4): 43-56. [ Links ]

Lo, T Y, Fung, I W H & Tung, K C F 2006. Construction delays in Hong Kong civil engineering projects. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 132(6): 636-49. [ Links ]

Mbande, C 2010. Overcoming construction constraints through infrastructure delivery. Proceedings, 5th Built Environment Conference, Association of Schools of Construction of Southern Africa, 18-20 July, Durban, Vol 18, p 20. [ Links ]

Mezher, T M & Tawil, W 1998. Causes of delays in the construction industry in Lebanon. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 5(3): 252-260. [ Links ]

Milford, R 2010. Public capacity payment and procurement issues should be a challenge to the operations of contractors in South Africa. Proceedings, 5th Built Environment Conference, Association of Schools of Construction of Southern Africa, 18-20 July, Durban. [ Links ]

Mofokeng, T G 2012. Assessment of the causes of failure among small and medium sized construction companies in the Free State Province. PhD Thesis, Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Mohlala, F T 2015. The relationship between project performance of emerging contractors in government infrastructure projects and their experience and technical qualifications: An analysis of 30projects conducted in the Mpumalanga Province over the 2011-2013 period. MSc Research Report, Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Myers, M D & Avison, D 1997. Qualitative research in information systems. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 21: 241-242. [ Links ]

Neely, A 1998. Measuring Business Performance. London: Economist Books. [ Links ]

Nemaenzhe, P P 2010. Retrospective analysis of failure causes in South African small businesses. PhD Thesis, Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Okpara, J O & Kabongo, J D 2009. An empirical evaluation of barriers hindering the growth of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in a developing economy. African Journal of Business and Economic Research, 4(1): 7-21. [ Links ]

Okpara, J O & Wynn, P 2007. Determinants of small business growth constraints in a sub-Saharan African economy. S.A.M. Advanced Management Journal, 72(2): 24-35. [ Links ]

Peacock, R 2000. Failure and assistance of small firms. Small Enterprise Series, 1: 1-56. [ Links ]

Peters, L M & Zelewski, S 2007. Assignment of employees to workplaces under consideration of employee competences and preferences. Management Research News, 30(2): 84-99. [ Links ]

Prais, S J & Steedman, H 1986. Vocational training in France and Britain: The building trades. National Institute Economic Review, 116(1): 45-55. [ Links ]

Pretorius, M 2009. Defining business decline, failure and turnaround: A content analysis. South African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 2(1): 1-16. [ Links ]

Richter, A 1998. Qualifications in the German construction industry: Stocks, flows and comparisons with the British construction sector. Construction Management and Economics, 16(5): 581-592. [ Links ]

Rozewski, P & Malachowski, B 2009. Competence management in knowledge-based organisation: Case study based on higher education organisation. Knowledge Science Engineering and Management, 5914: 358-369. [ Links ]

Rwelamila, P D & Hall, K A 1995. Total systems intervention: An integrated approach to time, cost and quality management. Construction Management and Economics, 13(3): 235-41. [ Links ]

Sambasivan, M & Yau, W S 2007. Causes and effects of delays in Malaysian construction industry. International Journal of Project Management, 25(5): 517-526. [ Links ]

Shepherd, D A, Wiklund, J & Haynie, J M 2009. Moving forward: Balancing the financial and emotional costs of business failure. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(2): 134-148. [ Links ]

Storey, D J 1994. Understanding the Small Business Sector. London: Routledge [ Links ]

Sweis, R J, Bisharat, S M, Bisharat, L & Sweis, G 2014. Factors affecting contractor performance on public construction projects. Life Science Journal, 11(4s): 28-39. [ Links ]

Temtime, Z T & Pansiri, J 2004. Small business critical success/failure factors in developing economies: SME evidence from Botswana. American Journal of Applied Sciences, 1(1): 18-25. [ Links ]

Thwala, W D & Mvubu, M 2005. Current challenges and problems facing small and medium size contractors in Swaziland. African Journal of Business Management, 2(5): 93-98. [ Links ]

Turner, J R 1999. Handbook of Project-Based Management. London: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Tushabomwe-Kazooba, C 2006. Causes of small business failure in Uganda: A case study from Bushenyi and Mbarara towns. African Studies Quarterly, 8(4): 1-13. [ Links ]

Van Eeden, S, Viviers, S & Venter, D 2003. A comparative study of selected problems encountered by small businesses in the Nelson Mandela, Cape Town and Egoli metropoles. Management Dynamics, 12(3): 13-23. [ Links ]

Van Witteloostujin, A 1998. Bridging behavioural and economic theories of decline: Organizational inertia, strategic competition, and chronic failure. Management Science, 44(4): 501-519. [ Links ]

Van Wyk, L 2003. A review of the South African construction industry. Part 1: Economic, regulatory and public sector capacity influences on the construction industry. Pretoria: CSIR, Boutek. [ Links ]

Yusuf, A 1995. Critical success factors for small business: Perceptions of South Pacific entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 33(2): 68-73. [ Links ]

Zulu, S & Chileshe, N 2010. Service quality of building maintenance contractors in Zambia: A pilot study. International Journal of Construction Management, 10(3): 63-81. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

F T Muzondo

4/66 Mandurah Terrace

Mandurah

Western Australia 6210

T: +61 401 341 879

E: fatemohlala@yahoo.com

R T McCutcheon

PO Box 43

Wits 2050

South Africa

T: +27 83 629 4783

E: roberttmccutcheon@gmail.com

FATE T MUZONDO holds a BSc in Agricultural Engineering and an MSc in Civil Engineering. She has worked as an engineer and project manager bringing infrastructure to subsistence farmers in Mpumalanga Province of South Africa. She currently works in the regulatory environment at one of Australia's largest banks. Her areas of interest are in the development of South African emerging contractors. She is a member of the Australian Institute of Engineers and the South African Institute of Agricultural Engineers, and is currently completing her PhD at the University of the Witwatersrand.

PROF ROBERT McCUTCHEON Pr Eng, Professor Emeritus and Honorary Professor in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand, is Employment Creation and Development Specialist at Malani Padayachee & Associates (Pty) Ltd, Consulting Civil and Structural Engineers, Randburg. In addition he is Research Associate in the Centre of Full Employment and Equity at the University of Newcastle, Australia. His work focuses on skills development, employment creation and programme management in the field of public works, with special reference to labour-intensive construction and small contractor development. He is currently engaged in research, consulting and implementation in this field in various countries.