Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering

On-line version ISSN 2309-8775

Print version ISSN 1021-2019

J. S. Afr. Inst. Civ. Eng. vol.56 n.2 Midrand Aug. 2014

TECHNICAL PAPER

The diversification strategies of large South African contractors into southern Africa

J Olivier; D Root

Correspondence

ABSTRACT

This article presents the results of a study into the current diversification strategies of large South African contractors and the reasons for choosing southern Africa as a diversification strategy. It investigated the major risks involved in doing business in southern Africa, which of the southern African countries are more favourable to diversify into and the impact of diversification on performance. It also attempted to identify the major competitors in southern Africa and the source of their competitive advantage.

The study consists of a literature review and utilised the data from the annual reports for the period 2007 to 2011 of nine selected large South African contractors, as well as relevant publicised news articles. All the data used in this study is already in the public domain.

The research found that the countries of southern Africa present significant opportunities for South African construction companies. Southern Africa forms a definite part of the diversification strategies of large South African contractors; they are, however, mostly moderately diversified, and the 'big' players are highly diversified both operationally and geographically. The extent of diversification has an impact on performance, as undiversified is clearly associated with underperformance, and moderately diversified within a specialised field with outperformance. The research was inconclusive on the identities of the major competitors in southern Africa and the source of their competitive advantage. It was, however, found through the literature study that Chinese contractors are the major competitive force in southern Africa and in the rest of Africa, and their governmental support systems on policy and financial backing are the source of their competitive advantage.

Keywords: diversification, South African construction industry southern Africa, strategy, large South African contractors

INTRODUCTION

Background

South African companies are increasingly operating and expanding into the rest of Africa. Ewing (2008) reported that South African companies have invested more than $8.5 billion into the sub-Saharan region, with firms such as SAB Miller, MTN, Vodacom, Shoprite and Standard Bank leading the way. Ewing (2008) also argued that South Africans possess an uncanny understanding and know-how of the risky African market, which gives them the edge over foreign competitors. South Africa Info (2011) lists the top 25 South African-based companies who are all rapidly expanding their global profile and are competing with the best global multi-nationals. These include mining houses such as Impala Platinum and Anglo American, and one of the largest local construction groups, Murray & Roberts (M&R). During the apartheid era, South African companies were confined to their home base by economic and trade sanctions imposed by the international community, and the South African economy was dominated by a few large companies that, due to their inability to expand abroad, were forced to invest in one another (The Economist 2006). Following the 1994 democratic elections and the lifting of economic sanctions with the end of the apartheid era, many South African corporations moved into the rest of Africa and beyond with great enthusiasm as markets opened up after many years of isolation (The Economist 2006).

The first wave of South African investment into other African countries in the post-apartheid years in the 1990s suffered due to market and cultural ignorance, but the second wave from 2000 onwards has seen South African companies profiting from those early mistakes and steadily expanding into the rest of Africa with great success (Rundell 2010). Companies like SAB Miller, Standard Bank and MTN have made the expansion into Africa during this second wave central to their growth strategy, and Standard Bank, for example, currently operates in 18 African countries. This continent-wide presence allows it to participate in project finance, mining deals and trade finance facilities (Rundell 2010). First Rand recently announced plans to refocus on Africa and has entered into a cooperation pact agreement with the China Construction Bank in order to establish a retail banking presence in Nigeria and Angola (Rundell 2010).

This drive into Africa has allowed companies to diversify their income streams and generate income in foreign currency (Grobbelaar 2004). Several African countries have enjoyed high average growth rates, e.g. Mozambique (7.22%), Uganda (7.16%) and Nigeria (7.56%), over recent years, while Equatorial Guinea has grown, on average, by 18.1% and Sierra Leone by 9.0% from 2000 onwards (Grobbelaar 2004). It is significant to note that South African companies have not been averse to expanding into sectors traditionally dominated by companies from the United States, Japan and Europe. Examples of such sectors are construction, industry, telecommunications, tourism, agriculture and financial services, in addition to the extraction industries, such as mining and oil, that are normally targeted (Grobbelaar 2004).

In the case of the largest South African construction companies, information obtained from their corporate websites confirms that southern Africa is part of their medium- to long-term strategy. The Aveng Group (Aveng 2011) states that they are focused on selected infrastructure, energy and mining opportunities in Africa, with a global footprint of over 25 countries. Part of M&R's 2009-2014 strategy (Murray & Roberts 2011) states that:

"Africa has become the new frontier for sourcing natural resources and the economic benefit will support the development of new public and commercial infrastructure" Similarly Basil Read (Basil Read 2011) has established a wide range of operations further into Africa, and Group Five (Group Five 2011) has also played a major role in the development of southern Africa's infrastructure.

A few years ago the construction sector reported strong earnings growth and held large, growing order books with investors' "high" expectations reflected in premium share ratings (McNulty 2010). The sector's shares are currently trading well below earlier highs and order book growth has slowed, with the large construction groups such as Aveng and M&R reporting lower earnings (McNulty 2010).

Munshi (2010) wrote that post World Cup 2010 has seen the South African construction sector needing to reposition itself with an eye to the north for sustained higher margins. The Global Construction Report 2020 (Global Construction Perspectives and Oxford Economics 2009) expects that construction in the developing world will more than double to generate sales of US$7 trillion by 2020.

The demand for construction services in sub-Saharan Africa

The current state of infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa is poor, which prohibits optimal economic growth and reduces business productivity by as much as 40% (AICD 2010). Prinsloo (2010) reported that this situation presents huge business opportunities in light of the backlog in infrastructure investment that requires an estimated US$93 billion a year. Almost half of this amount is needed to address the continent's power supply problem (AICD 2010). Real GDP growth rate projections for the countries of sub-Saharan Africa, which confirm the positive potential of the region, are shown in Table 1.

The construction sector of sub-Saharan Africa (excluding South Africa) is highly fragmented and underdeveloped, with limited potential to evolve into a functional and successful industry (Ebohon & Rwelamila 2001). The lack of co-ordination in the industry, skill shortages, sole-trader type entrepreneurship with little knowledge of the industry, the transient nature of most construction firms, inadequate technical training, inappropriate procurement systems and the general lack of management skills resulted in a dualistic structure in the sub-Saharan construction sector (Ebohon & Rwelamila 2001).

The activity of foreign international contractors, including American, European, Japanese, Korean and Chinese, in Africa increased at an average annual rate of 15.4% between 2000 and 2006 (Chen & Orr 2009). European contractors enjoyed a 41.5% share of the total African construction market in 2006, while Chinese construction firms in Africa grew by 46.2% between 2000 and 2006, and in 2005 had 32% of their total international revenue coming from Africa (Chen & Orr 2009). China has had longstanding policies of providing foreign aid to Africa and intergovernmental relations focusing on infrastructure development, resulting in the African construction market being the territory of Chinese contractors (Chen & Orr 2009). Foreign competition in the emerging African market is thus on the increase and foreign contractors are increasingly seeking opportunities in Africa.

The South African construction industry

Unlike other southern African countries, South Africa has a well-established construction industry with the ability to deliver a full range of projects, including the largest and most complex ones (Ofori et al 1996). South African contractors have developed corporate competitiveness honed by long periods of isolation during the apartheid era and adverse economic conditions (Ofori et al 1996). Many foreign contractors have been unsuccessful in South Africa due to stiff competition from local construction firms (Vance 1993). Ofori et al (1996) further state that South African construction companies undertake projects in the southern African region although the volume of this work is not high, and that they have the capability to undertake many of the projects awarded to foreign contractors from much further away (mainly Europe and East Asia). They are also of the opinion that the South African construction industry has to further develop the managerial skills required for competing overseas in order to exploit the opportunities that could emerge as the sub-Saharan African countries pull themselves out of long periods of economic decline (Ofori et al 1996).

The impact of globalisation on South African contractors

The primary forces of globalisation are represented by political reform, technological advances, the worldwide trend towards privatisation and an increasing recognition of economic interdependence (Hutton 1988; Kennedy 1991). The global economy thus presents favourable business environments for the construction industry through agreements such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and allows domestic construction companies to compete internationally (Gunham & Arditi 2005; Han & Diekmann 2001). South African construction companies have to plan strategically in order to continue on their growth path and to provide sustainable value to shareholders, and geographical expansion is one way in which South African contractors can overcome the volatility of the domestic market, spread their risk through diversification into new markets and take advantage of the opportunities offered by the global economy. The extent of geographical diversification of large South African contractors into the southern African region and the reasons they would choose this mode of diversification are not well understood, and research on the matter is not readily available.

PROBLEM STATEMENT, AIM AND OBJECTIVES

The countries of southern Africa, based on their emerging status and the currently unmet requirement for the provision of basic infrastructure, present huge opportunities for construction. The African construction market is currently dominated by foreign international contractors, particularly from China, Europe and North America, and it is possible that this is also true for the southern African region. Arguably, large South African contractors are strategically positioned to expand into this market, but will only be able to gain access to these opportunities if they have a clear geographical diversification strategy for this region, as well as a good understanding of the major risks involved. The problem to be investigated, which is therefore the aim of this research, is the current diversification strategies of large South African contractors, the reasons they would choose southern Africa as a diversification strategy, the major risks involved, which countries of southern Africa are more favourable and what the impact of diversification is on their performance.

The principal objectives are:

a. To determine the current diversification strategies of large South African contractors.

b. To determine the extent to which South African contractors diversify into southern Africa and why they would choose this strategy.

c. To determine the major risks involved in doing business in southern Africa.

d. To determine which countries of southern Africa are more favourable to diversify into.

e. To determine the impact of diversification on performance.

f. To determine who the main competitors are in the southern African region and what the source of their competitive advantage is.

METHODOLOGY

Literature review

A literature study was conducted on the notion of diversification of firms in the construction industry, with particular emphasis on international diversification. This was followed by a review of South African firms in general entering and doing business in the rest of Africa, as well as the specific opportunities for and risks faced by South African contractors operating in the southern African construction market. The southern African countries were rated from most to least favourable, and least to most risky, based on previous research data and current statistical data. The southern African countries of Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe were analysed in terms of a general overview, economic and political situation, construction opportunities and potential, construction-related risks and the state of the indigenous construction industry. The final section is an analysis of other major international construction competitors in the southern African region.

Research methodology

The methodology used was a desk-based study that included the data from publically available information from a selection of large South African construction companies. The primary data comprised the annual reports for the period 2007 to 2011 of the selected companies, as well as information from their internet websites, press releases and publicised articles.

The data was collected by using the internet via the corporate websites of the selected companies and internet search engines such as Google. An analytical template was constructed to organise the data in a clear, concise and systematic way. The template was divided into nine sections: background information, vision and mission statements, operating portfolio, geographical footprint, diversification matrix, financial performance, observations on strategy, observations on opportunities and risks, and articles and press releases.

The data was analysed using a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods, providing a triangulated approach. A series of charts and tables were constructed using the quantitative data from the analytical template in two major sections:

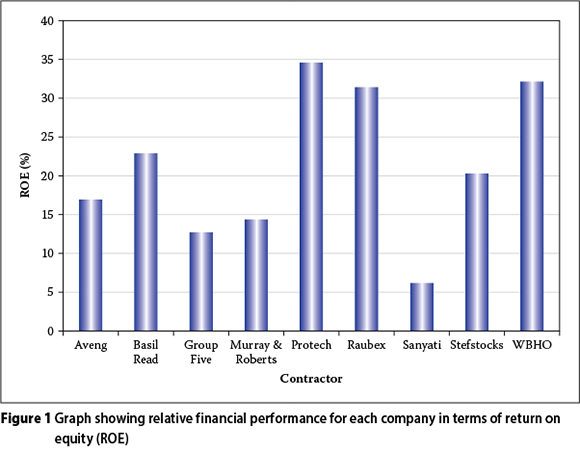

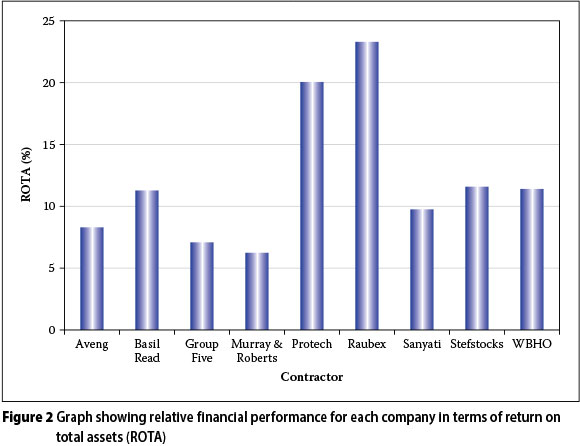

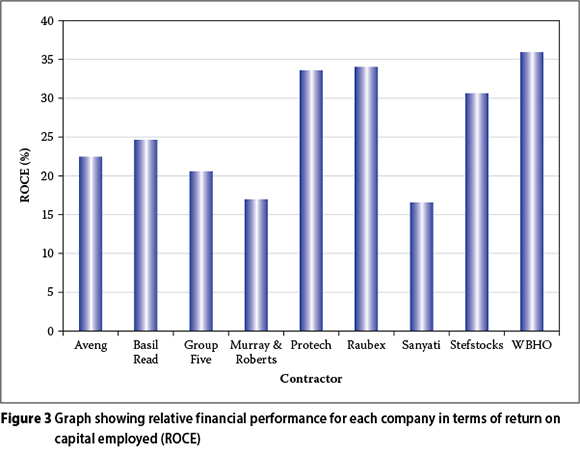

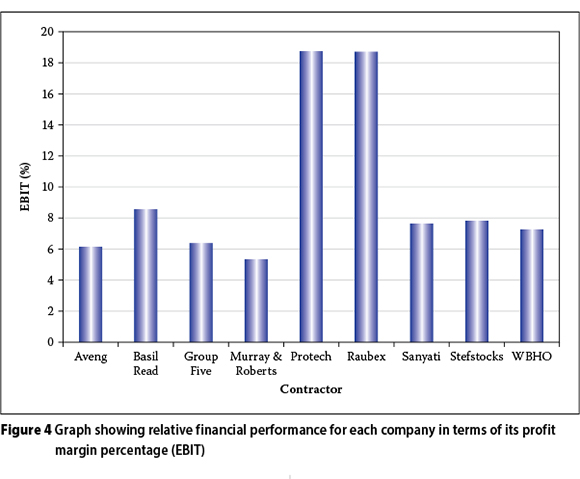

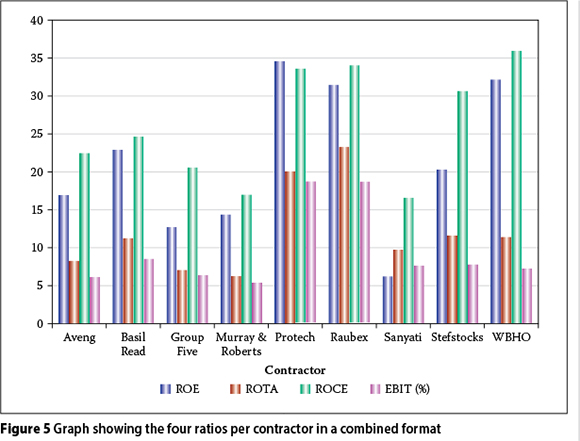

a. Financial performance: The average values over the five-year study period from 2007-2011 were calculated for each of the four ratios - return on equity (ROE), return on total assets (ROTA), return on capital employed (ROCE) and profit margin. This was done for all nine the companies studied, and a graph was built showing the average value for each company for each ratio, as well as a combined graph showing all four ratios for each of the nine companies.

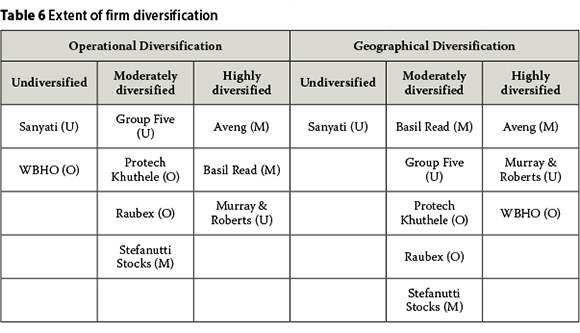

b. Diversification matrix: Two tables were drawn up, one showing the extent of operational diversification and the other showing the extent of geographical diversification for the nine companies studied. The first table was split into three columns - undiversified/single product, moderately diversified and highly diversified. The companies were then mapped into the three columns according to the results from the diversification matrix. The mapping exercise was done over the five-year study period for each company to indicate the movement (if any) from one category to another. Each company's rating in terms of financial performance was also entered alongside its position in the table.

The second table indicates the extent of geographical diversification. The table was again split into the three categories - undiversified (local South African market only), moderately diversified (mostly South African, limited cross-border operations) and highly diversified (internationally active). The companies were then mapped into the three columns according to the results from the diversification matrix. The mapping exercise was done over the five-year study period for each company to indicate the movement (if any) from one category to another. Each company's rating in terms of financial performance was also entered alongside its position in the table. The balance of the sections of the analytical template was used to construct a critical discussion for each individual company studied, as per the outline below:

a. Background information and overview of the company.

b. Their historical operational model, to give an idea of their modes of diversification. Here the interest will be to map their level of horizontal and vertical diversification.

c. Their current geographical footprint and how it changed over the study period, and which countries are preferred.

d. Future strategies relating to diversification in general, as well as their geographical expansion strategies. A specific focus area was their interests and intentions in the countries of southern Africa.

e. What they see as opportunities and threats, as well as the risks they are facing with specific reference to southern African countries.

f. Other general information relating to their diversification strategies with specific reference to publicised media.

RESULTS OF THE DATA ANALYSIS

Company selection

The construction companies studied were selected based on the following criteria:

a. Contractors currently active and registered as grade 9CE of the Construction Industry Development Board of South Africa (CIDB 2012).

b. Traditionally South African, excluding international contractors not originating in South Africa and whose head office is not in South Africa.

c. Specialist contractors were excluded.

d. Listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) with a current annual turnover exceeding R1 billion.

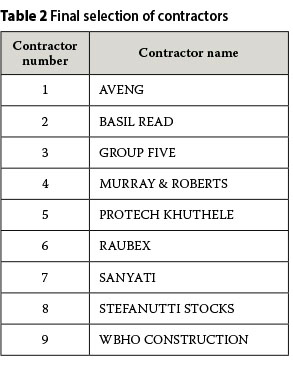

The final nine companies are shown in Table 2.

Financial performance of the selected group of contractors

The graphs in Figures 1-5 show the relative performance for each company in terms of the four ratios.

Table 3 shows the ranking and final rating per contractor. The final classification is based on the criterion that the top three companies in terms of financial performance are classified as 'outperformers (O)', the middle three as 'moderate performers (M)' and the bottom three as 'underperformers (U)'.

Diversification matrix

Table 4 shows the extent of operational diversification of the nine companies and Table 5 shows the extent of geographical diversification for the nine companies. The companies are mapped into three columns for both tables over the study period, and the movements are shown where a company has moved from one category to another. The final results of the extent of firm diversification are summarised Table 6.

Company analysis

The large South African contractors are mainly moderately diversified, with Aveng, M&R and Basil Read highly diversified. Sanyati and WBHO are the only contractors that are currently pure construction companies and fall into the undiversified or specialised classification. It must be noted that WBHO has moved between moderately and undiversified during the study period, and Sanyati has been undiversified during the whole study period. Raubex and PK are the only companies that are specialised in terms of construction - Raubex in road construction and PK in bulk earthworks. The rest of the companies are horizontally well spread across the construction value chain, i.e. civil engineering, building, roads and earthworks, etc. Aveng and M&R are by far the largest of the contractors and are the only ones that are fully diversified horizontally, vertically upstream and downstream, and relatedly in the mining sector. They can be classified as the construction conglomerates of South Africa. The balance of the companies are somewhere in-between, with no clear and definite trend visible from their operational diversification strategies. None of the companies are unrelatedly diversified, and all the companies that have diversification as part of their strategy are diversifying into construction-related businesses, such as engineering, construction materials supply and mining.

In terms of geographical diversification, Aveng, M&R and WBHO are highly diversified. They all have a large geographical footprint and they have a stable Australian-based construction business. They have been operating in southern Africa for a long period of time and their future target markets are the rest of Africa beyond southern Africa, Australasia and the Pacific, the Middle East and Asia. They each have a clear geographical expansion strategy and the aim to be a global player. The rest of the contractors are moderately diversified geographically, except for Sanyati that currently only operates in the South African domestic market. All of them have a clear focus on either expanding their current southern African footprint or entering the southern African market, except Sanyati. They also focus on the rest of Africa beyond southern Africa, albeit very selectively. Stefanutti Stocks and Group Five are operating in the Middle East and plan to extend their Middle Eastern footprint, and Basil Read has recently started expanding into Australia through their TWP engineering business. Group Five also has operations in Eastern Europe through their concessions business. The main strategy for these contractors is southern Africa, the rest of Africa and the Middle East.

Table 7 indicates the extent to which large South African contractors are diversified into the countries of southern Africa. The 'tick mark' indicates that the specific contractor is actively operating in that country unless otherwise noted.

From Table 7 it is evident that Aveng, M&R and Stefanutti Stocks are active in all the countries of southern Africa, while Basil Read, Group Five and WBHO are active in the majority of the southern African countries. Sanyati is not active in any of the southern African countries, and Protech and Raubex are active in selected countries only. The countries most operated in are Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Angola is the least favoured country.

Aveng and M&R, the two largest companies, are fully diversified into southern Africa, and have been for the full study period as well as for a substantial period before. This region is part of their established operating environment and they are currently looking beyond the southern African region for further geographical expansion. Basil Read, Stefanutti Stocks, Group Five and WBHO are still growing companies, and they see the southern African region as holding major opportunities for construction and mining, and an avenue for growth. Raubex and Protech are very selective in the region and they choose their target countries carefully. They also see opportunities in the road construction and mining infrastructure earthworks sectors. Sanyati has not started to operate in the region and is currently fully South African based.

All the contractors agreed that the African continent offers major opportunities for construction in the areas of infrastructure development, specifically transport, water, power and energy, as well as in the mining environment, with the demand for mineral resources growing tremendously in countries such as China, India, Russia and Brazil. These present strong pull forces for South African contractors to diversify and to expand their geographical footprint into southern Africa and the rest of Africa. They also indicated that the domestic South African construction market is currently in a recessionary phase of negative growth, resulting in increased competition, lower margins with a negative medium-term outlook. This is an indication of strong push forces for construction companies to expand into the southern African market.

The data analysis revealed the following major risks faced by South African contractors doing business in southern African countries:

a. Political risks, especially in unstable countries such as Zimbabwe.

b. Currency exchange rate fluctuations.

c. Bribery and corruption - This was mentioned by Basil Read in an article by Venter (2011a), as the company lost out on a tender for a project in Tanzania when they were not prepared to pay a bribe; the project was subsequently awarded to a Chinese contractor.

d. Late entry into Africa - M&R mentioned this as a risk, as large European and Asian contractors accessed Africa in its early development stages; this would possibly also include the southern African region.

Referring to Table 6 it is evident that the majority of the selected companies fall into the moderately diversified group, both operationally and geographically. The financial performance of this group ranges from outperformer to underperformer. Aveng and M&R feature in the highly diversified group for both operational and geographical diversification, and their performance is moderate and underperformer respectively. Sanyati is an underperformer and features for both operational and geographical diversification in the undiversified group. The undiversified (operationally and geographically) strategy is thus not a good business model for solid financial performance. The largest companies in terms of size, Aveng and M&R, are both highly diversified (operationally and geographically). Raubex and Protech are both outperformers and are both in the moderately diversified group for both operational and geographical diversification. Both these companies specialise in road construction and bulk earthworks respectively.

There is thus no clear and definitive answer as to what the recipe for success is, although the indications are that undiversified, both operationally and geographically, is associated with underperformance, and moderately diversified within a specialised field such as road construction is associated with outperformance. In order to be 'big' you have to be highly diversified, with specific reference to Aveng and M&R.

The main competitors in southern Africa and the source of their competitive advantage are not mentioned and thus no definite conclusion can be made from the data used. M&R mentioned that the European and Asian contractors accessed Africa during its early development period, and they (M&R) see that as a lost opportunity. It is assumed that the Asian contractors referred to would be the Chinese, as they are widely active in Africa.

CONCLUSIONS

From the literature study it was concluded that:

a. A comprehensive theory base exists around diversification in construction, and construction companies all over the world are practising a variety of diversification strategies, of which international expansion is used as a strategy to combat the cyclical nature of the construction industry and to maintain a competitive advantage over its rivals.

b. Many South African companies are expanding into the rest of Africa and the biggest risk of doing business in African countries is political instability. South African companies are, however, taking a high-risk, high-reward approach.

c. South Africa is by far the southern African region's largest and most developed economy, and the South African construction industry is mature, internationally competitive, has a very good track record and has a large pool of construction-related resources.

d. The countries of southern Africa are characterised as under-developed, having a huge backlog in the provision of basic infrastructure, under-developed indigenous construction industries, a scarcity of primary construction materials and construction spending that is mostly aid-and government-reliant.

e. Huge opportunities for construction exist in southern African countries in the form of infrastructure development, such as transport, water supply, sanitation and housing, as well as in the resource extraction industries, such as oil and mining.

f. Strong 'pull forces' exist for South African contractors in the form of construction-related opportunities to choose southern Africa as a geographical diversification strategy. The 'push forces' for geographical diversification into southern Africa are also strong, due to the facts that the South African construction industry is in a current downturn and the South African construction industry is well developed and internationally competitive.

g. Botswana, Namibia and Angola are rated number 1, 2 and 3 respectively as the most favourable countries to diversify into, and Zimbabwe is rated as the least favourable.

h. Chinese contractors are the major competitive force in southern Africa and they have a distinct competitive advantage over other construction players as a result of support from the Chinese government in the form of policy and financial backing.

The following conclusions were made from the research:

a. In terms of business diversification the majority of the large South African contractors are moderately to highly diversified. The two largest contractors are Aveng and M&R and they are fully diversified across the horizontal and vertical value chains. Sanyati and WBHO are pure construction companies and are undiversified. The diversification strategies are mainly construction-related, i.e. materials supply, engineering, etc, as well as related diversification in mining. The majority of the companies cover the full horizontal value chain in construction, such as civil engineering, building, roads and earthworks. None of the companies are unrelatedly diversified.

b. In terms of geographical diversification, eight out of the nine companies have an international footprint, with Aveng and M&R having the largest international footprint. Sanyati is the only company that only operates in the South African domestic market. All the companies, except Aveng and M&R, have southern Africa as part of their geographical focus. Aveng and M&R are focusing beyond southern Africa, as they regard southern Africa as part of their normal business area.

c. All the companies (except Sanyati) are operating in selected countries of southern Africa with Aveng, M&R and Stefanutti Stocks covering all the southern African countries. The most favourable countries for the large South African contractors are Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe, and the least favourable countries are Angola and Malawi.

d. The African continent offers major opportunities for construction in the areas of infrastructure development, such as transport, water, energy and power, as well as in the mining environment, with an increased demand for mineral resources from countries like China, Brazil, India and Russia.

e. The major risks for construction companies in southern Africa are:

i. Political uncertainty ii. Currency exchange rate fluctuations iii. Bribery and corruption iv. Competition from Asian and European contractors.

f. Undiversified, both operationally and geographically, is associated with underperformance, while moderately diversified within a specialised field, such as road construction, is associated with outperformance. The really 'big' players, Aveng and M&R, are highly diversified, both operationally and geographically.

g. It was mentioned that European and Asian contractors accessed Africa during its early development period. Who the main competitors in southern Africa are and their associated competitive advantage are inconclusive.

This research study has presented evidence that the countries of southern Africa present significant opportunities for large South African contractors, and that these countries indeed form part of the strategy of the large South African contractors. However, these contractors are mostly moderately diversified, although the 'big' players, Aveng and M&R, are highly diversified. The extent of diversification impacts on contractor performance as follows: undiversified is associated with underperformance, moderately diversified within a specialised field is associated with outperformance, and size is associated with highly diversified. The main competitors in southern Africa and the source of their competitive advantage are inconclusive from the research, although the literature study suggests that Chinese contractors are the main competitors in the region and that the source of their competitive advantage is the Chinese governmental support in the form of policy and financial backing.

REFERENCES

AICD (Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostics) (2010). Africa's Infrastructure: A Time for Transformation. A co-publication of the Agence de Frangaise de Dévelopment and the World Bank. Available at: http://www.infrastructureafrica.org/aicd [Accessed on 30 January 2011]. [ Links ]

Aveng Group 2011. Available at: http://www.aveng.co.za [Accessed on 16 December 2011]. [ Links ]

Basil Read 2011. Available at: http://www.basilread.co.za [Accessed on 16 December 2011]. [ Links ]

Chen, C & Orr, R J 2009. Chinese contractors in Africa: Home government support, coordination mechanisms, and market entry strategies. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 135(11): 1201-1210. [ Links ]

CIDB (Construction Industry Development Board) 2012. Available at: https://registers.cidb.org.za/reports/ContractorListing.asp [Accessed on 5 January 2012]. [ Links ]

Ebohon, O J & Rwelamila, P D M 2001. Sustainable construction in sub-Saharan Africa: Relevance, rhetoric and the reality. Agenda 21 for Sustainable Construction in Developing Countries. Africa Position Paper. Available at: http://www.sustainablesettlement.co.za/docs/a21_ebohon.pdf [Accessed on 2 April 2011]. [ Links ]

Ewing, J 2008. South African companies unlock sub-Saharan Africa. Bloomberg Business Week, Emerging Market Report. [ Links ]

Global Construction Perspectives and Oxford Economics (2009). Global Construction 2020: A Global Forecast for the Construction Industry over the Next Decade to 2020. Global Construction Perspectives and Oxford Economics Ltd. [ Links ]

Grobbelaar, N 2004. South African business marching north: Is there a case for regulation? Traders African Business Journal, May-August. [ Links ]

Group Five 2011. Available at: http://www.groupfive.co.za [Accessed on 17 December 2011]. [ Links ]

Gühan, S & Arditi, D 2005. Factors affecting international construction. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 131(3): 273-282. [ Links ]

Han, S H & Diekmann, J E 2001. Approaches for making risk-based go/no-go decisions for international projects. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 127(4): 300-308. [ Links ]

Hutton, J 1988. The World of the International Manager. Oxford: Phillip Allan. [ Links ]

IMF (International Monetary Fund) 2012. World Economic Outlook: Growth Resuming, Dangers Remain, April 2012. Washington DC: International Monetary Fund. Available at: http://www.imfbookstore.org [ Links ]

Kennedy, C R 1991. Managing the International Business Environment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

McNulty, A 2010. Things fall apart. Financial Mail, 1 July. [ Links ]

Munshi, R 2010. All the world's their stage. Financial Mail, 1 July. [ Links ]

Murray & Roberts 2011. Available at: http://www.murrob.com [Accessed on 19 December 2011]. [ Links ]

Ofori, G, Hindle, R & Hugo, F 1996. Improving the construction industry of South Africa. Habitat International, 20(2): 203-220. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, L 2010. Africa's infrastructure deficit creates economic opportunity. Engineering News, 19 October. [ Links ]

Rundell, S 2010. Massive profits follow S Africa's northern 'invasion'. African Business, 365 (June): 40-44. [ Links ]

South Africa Info 2011. Available at: http://www.southafrica.info [Accessed on 2 November 2010]. [ Links ]

The Economist 2006. South African business. Going global. 13 July. [ Links ]

Vance, W G 1993. Changing role of construction companies in infrastructure projects. The Civil Engineering Contractor, June, pp 5-7. [ Links ]

Venter, I 2011. Failure to pay bribes cost Basil Read R1.1 bn in work. Engineering News, 25 March. Available at: http://www.engineeringnews.co.za [Accessed on 27 March 2011]. [ Links ]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Langford, D A & Male, S 2001. Strategic Management in Construction, 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science. [ Links ]

South African Reserve Bank 2011. South African Reserve Bank: Annual Economic Report 2011. Pretoria: South African Reserve Bank. [ Links ]

The Africa Competitiveness Report 2009. World Economic Forum, the World Bank and the African Development Bank. [ Links ]

SAFCEC (South African Federation of Civil Engineering Contractors) 2010. State of the Civil Industry: 1st Quarter 2010. Available at: http://www.safcec.org.za [Accessed on 22 January 2011]. [ Links ]

SAFCEC (South African Federation of Civil Engineering Contractors) 2012. State of the Civil Industry: 1st Quarter 2012. Available at: http://www.safcec.org.za [Accessed on 15 June 2012]. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

J Olivier

WBHO - Civils Division

53 Andries Street

Wynberg

Sandton

South Africa

T: +27 11 321 7200

E: Johan_Olivier@wbho.co.za

D Root

University of the Witwatersrand

School of Construction Economics and Management

1 Jan Smuts Avenue

Braamfontein

South Africa

T: +27 11 717 7669

E: David.Root@wits.ac.za

JOHAN OLIVIER Pr Eng, Pr CM, MSAICE is currently working as a contracts manager at WBHO Construction. He obtained a B Eng Civil Engineering degree at the University of Stellenbosch in 1995, a B Eng Honours in Structural Engineering at the University of Pretoria in 2000, and an MSc in International Construction Management at the University of Bath in the UK in 2012. He has 18 years' experience in the civil engineering construction industry.

PROF DAVE ROOT is Head of the School of Construction Economics and Management at the University of the Witwatersrand. He originally trained as a Building Surveyor in the UK before entering academia. David obtained an Honours degree in Building Surveying from the University of Salford, and MSc and PhD degrees in Construction Management from the University of Bath. He is a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Building (CIOB) and the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS), and is registered with the South African Council for the Project and Construction Management Professions (SACPCMP) as a Construction Project Manager in South Africa.