Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering

versão On-line ISSN 2309-8775

versão impressa ISSN 1021-2019

J. S. Afr. Inst. Civ. Eng. vol.53 no.1 Midrand Abr. 2011

TECHNICAL PAPER

Reducing crime in South Africa by enforcing traffic laws a 'broken windscreen' approach

P C Bezuidenhout

ABSTRACT

The situation on our country's roads has gradually deteriorated to the point where traffic laws are being broken at various levels on a daily basis with few or no consequences for the offenders. Something needs to be done to turn the current situation around and prevent further deterioration. A 'broken windscreen' approach is introduced as a possible solution, with the emphasis on traffic enforcement, and it may also contribute to the combating of crime in South Africa.

The 'broken windows' theory and its implementation in New York City is briefly discussed to explain the concept. The difference between the broken windows and zero tolerance approaches is discussed from a local perspective, and the broken windows theory is then linked to the traffic situation in South Africa. The Safe Streets 1997 Program, which was based on the broken windows theory and implemented in Albuquerque, achieved a varying degree of success, and is discussed in this article. A critical link is then highlighted between traffic offences and more serious crime from the Safe Streets 1997 Program and also research conducted by the London Department of Transport (Knox & Silcock 2003). A broken windscreen approach is recommended in the light of the examples and data discussed.

Keywords: broken windows, traffic law enforcement, Safe Streets 1997 reducing crime, broken windscreen

INTRODUCTION

The situation on the roads across South Africa has deteriorated rapidly. Offences such as running red lights, not using indicators, passing on blind corners and rises, using the emergency lane or shoulder as an additional lane and stopping in no-stopping zones have become everyday occurrences. South Africa is in dire need of radical action to prevent the situation from further deteriorating.

New York achieved success in reducing its rampaging crime rate during the 1990s by adopting the much-publicised 'broken windows' theory (Wikipedia 2009). Success was also achieved in the Safe Streets 1997 Program implemented in Albuquerque, New Mexico (Albuquerque Police Department 1997).

A study conducted by the London Department of Transport (Knox & Silcock 2003) was able to link traffic violations and more serious crime. The basic fact is that criminals also have to make use of transport to reach their destinations. It should thus be possible to contribute significantly to reducing crime in South Africa simply by properly enforcing traffic laws and adopting a 'broken windscreen' approach.

BROKEN WINDOWS AND NEW YORK CITY

During the 1990s to the early 2000s, New York City experienced a dramatic drop in crime. This has widely been accredited to then Mayor Rudy Giuliani and the New York City Police Department Commissioner Bill Bratton. What they did was to implement an aggressive enforcement strategy based on James Q Wilson's and George L Kelling's broken windows approach (Wikipedia 2009).

The article Broken Windows first appeared in the March 1982 edition of The Atlantic Monthly magazine - the title was derived from the following explanation: "Consider a building with a few broken windows. If the windows are not repaired, the tendency is for vandals to break a few more windows. Eventually, they may even break into the building, and if it's unoccupied, perhaps become squatters or light fires inside. Or consider a sidewalk. Some litter accumulates. Soon, more litter accumulates. Eventually, people even start leaving bags of trash from take-out restaurants there or breaking into cars." (Wikipedia, 2009) In 1996 the book, Fixing broken windows: Restoring order and reducing crime in our communities by George L Kelling and Catherine Coles was published to support the theory (Free online research papers 2009). The situation in the US described in their book reads like a reflection of the current situation in South Africa.

The broken windows theory made two major claims, firstly that petty crime and low-level anti-social behaviour will be deterred, and secondly that major crime as a result will be prevented (Wikipedia 2009). Social experiments have been conducted in the Netherlands that lend support to the theory (Kaplan 2008).

Simply put, the broken windows theory claims that if something is not stopped while it is small it will continue to grow until it gets out of control (Free online research papers 2009). The theory is further described as a combination of several aspects:

Firstly, the community is directly responsible for the crime rate in their area. The citizens should try to prevent crime in their individual neighbourhoods, and by doing this they in fact help to protect the society.

Secondly, police officers need to be proactive in their crime-preventing strategies. Police patrols and visible community policing are needed.

Thirdly, broken windows is also used as a metaphor to show how people can play their part in combating crime.

It is concluded that, in order to effectively protect society from fear and disorder, the police, communities and the criminal justice system need to work together (Free online research papers 2009).

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN BROKEN WINDOWS AND ZERO TOLERANCE

Kockott (2005) explained the difference between a zero tolerance approach and the broken windows theory. The two are closely related, but the zero tolerance approach relies on much harsher implementation than the broken windows approach and has been widely criticised. Zero tolerance only provides a short-term solution without tackling the roots of the problems.

Senior British police official, Charles Pollard, believed that a short-term fix of order maintenance policing did not offer a long-term solution to complex social problems such as poverty and social exclusion and that it may in fact even make them worse (Dixon 2000).

Zero tolerance in South Africa

Dixon (2000) argued that zero tolerance is a popular slogan for politicians talking tough. He stated that the experience in Cape Town suggested that, under South African conditions, the rhetoric of zero tolerance was more powerful than the reality.

A small number of senior police and crime prevention officials were interviewed by Dixon (2000) in the Western Cape. The respondents, both inside and outside the South African Police Service (SAPS), had been personally involved in policing initiatives that at one time or another involved zero tolerance.

Dixon (2000) stated that two themes ran like golden threads through all of the interviews - first, the impossibility of sustaining a 'high impact' style of policing, and second, the need to be sensitive to South Africa's immense cultural diversity.

The respondents did, however, pay tribute to the impact Wilson, Kelling and Bratton (Wikipedia 2009) had on police thinking, but the senior police officials were anxious to distance themselves from the crude simplicities of zero tolerance.

A SAPS officer involved in dealing with 'urban terrorism' in the Western Cape described how attempts to use a zero tolerance approach to the problem had to be curtailed in the face of popular concerns about police 'harassment' of the leadership of People Against Gangsterism and Drugs (PAGAD). The media started giving publicity to the complaints of PAGAD that they were being harassed by the police, and the situation was compared to a form of apartheid against the Muslim community, which quickly led to the police reviewing their strategy (Dixon 2000).

A senior municipal law enforcement officer summed up the feeling among both the SAPS and local government officials who were interviewed by Dixon (2000) when he cautioned that, before anything like zero tolerance policing could even be attempted in South Africa, great care should be taken to make sure that such a strategy is sustainable, credible and broadly accepted by the public. The officer stated that more than half the success of such a programme would depend on the community and their acceptance of the policing principles.

WHY 'BROKEN WINDOWS' IS RELEVANT TO TRAFFIC IN SOUTH AFRICA

Gary Ronald, the public affairs head of the Automobile Association (AA) of South Africa, stated that South African roads were fast gaining a reputation as the most dangerous in the world. According to Ronald, a combination of factors is primarily to blame, including poor law enforcement, a blatant disregard for the law by drivers and the shockingly inept legal systems in place for prosecuting offenders (Sapa 2010).

Let us assume that the problem started with a few minibus-taxis bending the traffic rules slightly. There were no consequences for their actions, and slowly but surely they started pushing the limits of their offences, which finally escalated into a total disregard of the law by a large number of taxi drivers. Motorists noticed that taxi drivers could get away with offences and started following their example. This is in line with the broken windows theory and could explain the situations encountered on our roads today.

In an article in the online news site News24 by Simon Carter (Carter 2009), the situation in the Johannesburg CBD is described as an absolute nightmare with regard to the actions of taxis. The author was even threatened with a firearm by a taxi driver.

Dr Johan Burger described the situation on our roads as follows (Burger 2008): "Indeed, it is shocking to observe the amount of lawlessness on our roads. Minibus-taxi drivers are perhaps the best example of a group of road users who believe that the law does not apply to them. They move about according to their own rules. Even worse is the fact that otherwise law-abiding road users often follow this bad example."

The fact that many motorists also disobeyed the rules of the road was confirmed by the various comments posted by News24 readers on the article by Simon Carter (2009), that taxis were not solely to blame for the chaos on the roads.

The theory is that, because taxis were not convicted for their offences, motorists also started to bend the rules more and more. This is backed up by the turnstile theory as described in the article Road Rage I: Aggressive driving (Thin slice of life 2008): "The turnstile theory argues that people who see turnstile hoppers get away without paying train fares are more likely also to hop turnstiles. This in turn creates more petty criminals who may then escalate to more violent crimes over time. So, by policing turnstiles and punishing hoppers quickly, violent crimes of the future could be prevented."

According to the broken windows theory it should thus be possible to improve the situation on our roads by clamping down on minor offences. This claim was successfully put to the test in Albuquerque, New Mexico (Albuquerque Police Department 1997).

ALBUQUERQUE POLICE DEPARTMENT'S SAFE STREETS PROGRAM

The reasoning and development behind the Safe Streets 1997 Program

The Safe Streets Program report by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, which appears on the US Department of Transport's website (Albuquerque Police Department 1997), states that throughout 1996, the news media in Albuquerque seemed to be filled with reports of robberies, burglaries and murders. A dramatic increase in crime during 1996 was accompanied by a 13% jump in crashes along with a noticeable increase in aggressive driving. According to some observers the changes coincided with a shift in the public's attitude away from civility and respect for fellow citizens and the law.

The public in Albuquerque, however, demanded action after a spate of road rage incidents which ended in fatalities, of which one was a high school athlete. The task of doing something about the situation was assigned to Officer Jay Gilhooly, the Albuquerque Police Department's coordinator of traffic safety programmes. After extensive research by Gilhooly, the City Planning Department was approached to plot the dozen or so reported incidents of road rage on a map. The dots representing the incidents at first had no apparent pattern and were scattered across the map.

All the high-crash intersections in the city were plotted next, the reasoning being that the relatively rare incidence of road rage might be related to the more frequent incidence of accidents. Albuquerque contained 33 of New Mexico's top 50 intersections in terms of number of crashes. The plots on the map indicated that 27 of these 33 intersections were concentrated in four different clusters, each located in a different area of the city. Officer Gilhooly immediately recognised the clusters as high-crime areas from his patrolling experience. His hypothesis was then confirmed by adding crime data to the map of the high-crash intersections - the two sets of dots were found to coincide and formed four colourful blobs on the map of the city. The co-occurrence of crashes and crimes was seen as a golden opportunity to do something about both problems.

Officer Gilhooly then approached Lieutenant Rob DeBuck, who had a similar mandate to do something about the crime situation. Lieutenant DeBuck had been studying the broken windows approach as described in the 1982 article. Gilhooly, DeBuck, and APD traffic lieutenant, Paul Heatley, found merit in the broken windows theory. They applied the following reasoning: "If untended property eventually becomes fair game, untended behaviour eventually leads to a breakdown of community control."

The officers theorised that roads are to the residents of cities what the subways were to New Yorkers. Thus if the New York Transit Authority could restore order to their subways by dedicated maintenance and law enforcement, perhaps civility could be restored to the streets by focusing on a specially formulated traffic enforcement effort.

The officers approached the New Mexico State Highway and Transportation Department and found that the Traffic Safety Bureau was willing to assist and was creative as well. The Bureau's Chief Planner and the Police Traffic Services Program Manager were both committed to 'Look beyond the Ticket', a concept that links traffic enforcement to the overall mission of a law enforcement agency. A special enforcement programme was created from the partnership between the traditional and non-traditional partners and was called Safe Streets 1997.

One of the main strategies of Safe Streets 1997 was to saturate each of the four highcrime/high-crash areas identified by Officer Gilhooly one at a time with law enforcement officers.

The Police Department's crime deterrence grant was, however, ended after five months, which resulted in the withdrawal of officers from the saturation patrols. Improving traffic safety was the primary objective throughout the Program and the ending of the crime deterrence grant allowed the officers to focus more on the reduction of aggressive driving and fatal collisions. Traffic safety was emphasised throughout the second half of Safe Streets 1997.

The effects of the Safe Streets 1997 Program on crime

A 9,5% decrease in crimes against persons was experienced in the four special enforcement areas together during the first six months of the Program when compared to the same period a year earlier. However, the incidence of these crimes began to increase above the previous year's rate at roughly the time when traffic enforcement shifted from the neighbourhoods to the arterials. The incidence of crimes against persons, however, remained at 2% below the previous year's rates during the second half of the Program, despite the shift in the traffic enforcement effort away from the high-crime neighbourhoods. The overall number of crimes against persons reported in 1997 was 5% below the 1996 figures in the four special enforcement areas. Included in the overall decline in crimes was a 29% decline in homicide, a 17% decline in kidnapping, and a 10% decline in assault.

The number of property crimes reported in the four special law enforcement areas followed a pattern that was very similar to that of crimes against persons. The overall number of property crimes in 1997 was 3% below the 1996 figures in the four special enforcement areas. The overall decline included a 36% decline in arson, a 10% decline in fraud and a 9% decline in both robbery and burglary.

The effects of the Safe Streets 1997 Program on traffic

Prior to Safe Streets 1997, traffic collisions in Albuquerque had increased by 51% during the preceding five years. An increase of 13% in all collisions was recorded from 1995 to 1996. This increase was accompanied by an increase in aggressive driving and the road rage incidents that led to the special enforcement effort.

Total crashes declined from 1996 to 1997 as follows:

9% decline in property damage only crashes

18% decline in injury crashes (compared to 3% in the rest of New Mexico)

20% decline in driving under the influence of alcohol crashes

34% decline in fatal crashes The sum of all crashes declined in Albuquerque by 12% during Safe Streets 1997. During the same period, total crashes increased by 4% in the state's other urban areas.

Fewer serious crashes were experienced in Albuquerque during each month of Safe Streets 1997, in comparison to the same month one year earlier. There were 13% fewer serious crashes during the first half of the Program and 24% fewer serious crashes during the second half. A saving to society of more than US$34 million was estimated to have been made by preventing crashes.

Other outcomes and effects of Safe Streets 1997

The incidence of crime declined in response to the saturation patrols in the four identified areas as reported previously, and many arrests were made as a consequence of the special law enforcement effort and the increased emphasis on traffic safety and traffic enforcement throughout the Albuquerque Police Department.

The number of arrests made in 1997 increased by 14% over the previous year.

It became increasingly difficult during the Safe Streets Program to find traffic violations. Locations that easily generated ten traffic citations at the beginning of the Program were producing only one or two citations towards the end of the Program.

Crowding at the Albuquerque municipal court became a serious problem because of the large numbers of people attempting to pay their traffic fines.

The Chief received a call from the court administrator to inform him that the volume of citations was helping the court financially, and that he endorsed the special enforcement effort, and gave assurance that if needed, the court would increase the number of days needed for the traffic court to accommodate the increase in citations.

The citations issued generated more than US$4 million in revenue for the state's education fund.

There were fewer calls for the local ambulance service since the beginning of the Safe Streets Program.

The public responded positively to Safe Streets 1997. To the surprise of many officers, residents came out of their homes and cheered as they made enforcement stops in the neighbourhoods. Passing motorists blew their hooters in the business districts and made gestures showing their support of the enforcement effort. Furthermore, officers were invited to appear on local television to discuss Safe Streets 1997, newspapers published favourable articles, and citizens wrote letters to the editor expressing sincere appreciation for the Program.

Conclusions drawn from the Safe Streets 1997 Program

The Safe Streets Program demonstrated what can be accomplished by a community when they participate in identifying and solving social problems.

There were substantial improvements in civility on the streets of Albuquerque with a definite reduction in road rage incidents.

The results of the Albuquerque Police Department's Safe Streets 1997 Program strongly suggest that a special traffic enforcement programme can:

Deter criminal activity

Improve traffic safety

Contribute substantial economic savings to society.

CRIME IN SOUTH AFRICA

South Africa held its fourth national elections in 2009, and nearly all the political parties standing in the elections had combating of crime as one of the main priorities of their election manifestos. This stood to reason as the crime rate in South Africa had escalated to detrimental levels and citizens were demanding that action be taken. The crime statistics for the period of 2007/2008 include the following (SA Good News 2008):

There were 18 487 cases of murder.

Attempted murder decreased to 18 795 .

Common robbery decreased to 64 985.

Common assault decreased to 198 049.

Robbery with aggravating circumstances decreased to 118 312.

Just under 14 500 cases of residential robbery were recorded.

Businesses robberies increased to 9 862.

Carjacking and truck hijackings increased by 4,4% and 39,6% respectively.

Drug-related crimes increased by 3,3%.

Driving under the influence increased by 25,4%.

Although the figures for most of the crime categories indicated a decline compared to the previous year, the question should be asked whether this was due to current crime prevention programmes that were proving to be effective, or whether fewer crimes were being reported to the police due to a lack of confidence in the system. Whatever the answer may be, it is indisputable that the level of crime is still unacceptably high.

Dr Johan Burger (Burger 2008) stated that the incidence of crime and disorder suggested a creeping decay, which was all the more worrying because the distinction between lawlessness and anarchy is uncomfortably vague. He said the irony was that South Africans were often very intolerant and even critical when the police performed law enforcement activities regarding what is thought of as minor crimes or disorders.

LINKING TRAFFIC OFFENCES AND CRIMINAL ACTIVITY

The London Department of Transport conducted a study into unlicensed driving and produced an interesting report (Knox & Silcock 2003).

The primary concern of the study was to investigate the extent of unlicensed driving and the link between unlicensed driving and crashes. The Department was, however, aware of ongoing interest in the link between traffic offences and other criminal activity in general. The thinking was that it could be possible that unlicensed driving may extend beyond being just a road traffic violation and could be an indicator of wider criminality. If this was indeed found to be the case then there could be wider benefits to investing in resources for possible countermeasures and enforcement.

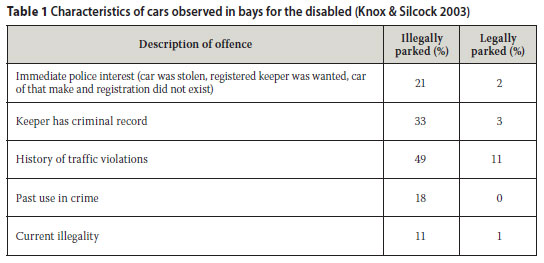

A conference paper was presented at a Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport Safety. The paper (Pease 2000, as cited in Knox & Silcock 2003) set out to establish whether indirect targeting of prolific offenders was a promising crime reduction tactic, and whether prolific offenders also violated traffic laws. A study was described during the presentation where traffic wardens recorded the details of cars parked illegally in parking bays for the disabled, as well as the details of the nearest legally parked car. Information about the vehicles and registered keepers (registered owners) was then obtained. The results of the study are shown in Table 1.

From the information it was concluded that for the illegally parked cars there was a much higher probability of their being associated with other criminal activity and traffic violations. This effect was found to be even more marked in situations where legal parking was scarce.

The report also mentioned previous research that investigated criminal records and traffic offences of unlicensed drivers which made similar findings.

It was concluded from the report that people who commit traffic offences often fell into one of the following categories:

They had a history of other traffic violations.

They had a criminal record.

They may be associated with activities that would warrant arrest.

ADOPTING A BROKEN WINDSCREEN APPROACH IN SOUTH AFRICA

The crime situation in South Africa has deteriorated to such an extent that an approach such as zero tolerance may even deserve consideration. An approach more in line with the broken windows theory would, however, be more feasible due to the less aggressive nature of the approach as described by Kockott (2005). Shaw (1998) indicated that international experience of crime prevention suggested a need for programmes to be developed through the process of experimentation.

As indicated by the implementation of the Safe Streets 1997 Program in Albuquerque, and also by the data of the London Department of Transport showing an apparent link between traffic violations and criminal offences, the possibility of using traffic law enforcement as a measure of fighting crime becomes a more attractive prospect.

Shaw (1998) stated that traffic law enforcement was in itself a crime prevention function if carried out effectively. He stated that effective traffic policing had important implications for crime prevention, as traffic police officers tend to have a more visible presence in cities and towns and therefore effectively indirectly perform a crime prevention function. The effective regulation of traffic would ensure well-managed and regulated cities and towns, resulting in environments less conducive to crime.

To make the broken windows theory more relevant to traffic situations the term 'broken windscreen' is adopted here. The term applies to the original theory by James Q Wilson and George L Kelling (Wikipedia 2009) in the sense that if a vehicle's windscreen is chipped, the chip or crack needs to be repaired at an early stage to prevent it from spreading to the point where the entire windscreen will have to be replaced. Thus fixing a small, minor crack will lead to the prevention of major cracks in the windscreen.

The initial step towards implementing a broken windscreen approach would consist of getting the various role players together to draw up a plan of action. As was done during the Safe Streets Program in Albuquerque, the main problem areas should be identified for clamping down on traffic offences. Offences should include such actions as running red lights, stopping in no-stopping zones, jumping traffic queues, jaywalking and offences other than only speeding violations which is the current norm.

As stated by Dixon (2000), it can be understood that it would be difficult to maintain such campaigns due to a lack of resources. This is, however, where interdepartmental planning between the SAPS, the Metro Police and traffic officers would come into play to allocate the available resources in an intelligent way to obtain the best results.

Metro Police departments began to be instated in South Africa from 2000. The main functions of the Metro Police are traffic law enforcement, municipal by-law enforcement and crime prevention as stated in the SA Crime Quarterly (Newham 2006). The Metro Police could thus play a vital role in the implementation of the programme as it falls squarely within their mandate.

Technology could also be used to help overcome the manpower shortages. This could be achieved by installing either video or still cameras at strategic locations. The community could also be approached to help in this regard and work on a commission basis by videotaping traffic offences.

At the beginning of 2007, First National Bank (FNB) had a progressive R20 million anti-crime initiative lined up with the purpose of encouraging then president Thabo Mbeki to make crime his number one priority. The campaign was, however, cut short before implementation by FNB management after a meeting with government representatives and other stakeholders (Hogg 2007). More recently, President Jacob Zuma was offered R1 billion by a top businessman to help combat crime (The Herald 2009).

This indicates a willingness of private enterprises to get involved and help in the combating of crime. Ever since the FNB campaign was withdrawn, no other corporate campaign of similar magnitude or with a similar goal in mind has publicly come to the fore. In the current global economic crisis it is understandable that such issues may not receive the highest priority at this time. The recession will, however, subside in due course but the problem of crime will still be here and perhaps escalate to an even greater extent as a result of the poor economic climate.

Critical to the success of the programme would be advertising it to the public, explaining what is planned, and most importantly, why it will be done. The various types of media available can be used for this purpose and should form the backbone of the operation as communities would have to support the programme whole-heartedly to make it a success.

The programme should first be implemented on a trial basis in only one metropolitan area for a fixed period of time, followed by an extensive analysis of the results. Should the programme prove effective it could then gradually be adopted and implemented on a larger scale, until it is eventually implemented nationally.

The following possible positive outcomes could be expected if a broken windscreen approach were adopted in South Africa:

A reduction in accidents and road deaths which would contribute to a massive saving. For the period 2007/2008 the cost of fatal crashes in South Africa totalled R13,27 billion (RTMC 2008:8). The RTMC (2008) indicated that over the 12-month period from 1 April 2007 to 31 March 2008:

The number of fatal crashes in South Africa was 11 577.

The number of fatalities was 14 627.

The income from traffic fines would be high during the initial phases of the programme until the point is reached where offences start to decline.

Arrive Alive (2009) stated that the number of reported incidents of road rage in South Africa has been on the increase and that road rage has become a major threat to safe driving. Implementing a broken windscreen approach could result in a reduction in road rage due to motorists adhering to the traffic laws, which would in turn contribute to less stress for drivers.

A reduction in crime, however small, is more than likely to occur.

Pride and confidence would be regained by the law enforcers as they would be working towards a common goal, which is to make South Africa a better place to live.

Communities would gradually begin to take part in the initiatives and a sense of pride and patriotism could be born out of the idea that everyone can contribute towards making the country a better place to live.

The positive image of the country will ultimately lead to economic growth. The following obstacles are, however, likely to be encountered:

At first the public may be reluctant to participate in the programme. The bad habits that have been adopted by drivers would be punished and at first this would most likely not be supported by the regular offenders.

The already full courts would be overburdened and additional courts may be required, as was the case in Albuquerque.

Lack of staff, resources and finance may pose a problem.

If the programme is not correctly implemented and is implemented more in a zero tolerance fashion than a broken windows approach, police harassment and undeserved victimisation may occur.

Corruption and bribery are a cause for concern.

Collaboration between all law enforcement authorities would be required and this may prove challenging at first.

All these obstacles can, however, be overcome with proper planning and the desire to achieve success. The crux of the idea is to clamp down on traffic offences by means of collaboration between all law enforcement authorities and the community in an attempt to end the anarchy on our roads, and in the process contribute towards solving other major problems in South Africa, including crime.

CONCLUSION

The fact that crime and traffic violations can be successfully linked provides justification for the enforcement of traffic laws. In order to successfully turn the tide and achieve long-term success, a programme such as broken windscreen should be strongly considered.

It should be noted that the implementation of the broken windscreen approach, as mentioned above, is by no means an ultimate blueprint. This approach merely serves as a theory of what could be implemented along with some guidelines of how to implement it and the possible outcomes.

It is essential that the programme should be properly developed by all the law enforcement agencies involved before it is implemented to prevent it from ending in failure due to miscommunication and lack of teamwork. It will be of the utmost importance for communities to actively engage in the programme, as its success will depend on their cooperation and acceptance of the programme.

Judging by the responses to articles in the press, and on various news sites and blogs, the best time to approach the community with such a programme is right now. South Africa requires unique solutions to its problems. We urgently need to start thinking in a proactive rather than a reactive way to start building our society.

In the words of Margaret Mead (quoted in Bloom 2009): "Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has."

REFERENCES

Albuquerque Police Department 1997. Safe Streets Program, US Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, DOT HS 809 278, www.nhtsa.dot.gov [ Links ]

Arrive Alive 2009. Road rage in South Africa. www.arrivealive.co.za [ Links ]

Bloom, J 2009. Fix the small things. www.citizen.co.za/index/article.aspx?pDesc=91060,1,22 [ Links ]

Burger, J 2008. Broken Windows and our lawless society. Institute for Security Studies, www.iss.co.za/index.php?link_id=24&slink_id=5624&link_type=12&slink_type=12&tmpl_id=3 [ Links ]

Carter, S 2009. The taxi circus. www.news24.com/News24/MyNews24/Letters/0,,2-2127-2129_ 2515048,00.htm [ Links ]

Dixon, B 2000. Zero tolerance: The hard edge of community policing. Institute of Criminology, University of Cape Town, African Security Review, 9(3), www.issafrica.org/Pubs/ASR/9No3/Zerotoler.html [ Links ]

Free online research papers 2009. Broken windows theory. www.freeonlineresearchpapers.com [ Links ]

Hogg, A 2007. Inside the 'pulled' FNB ad campaign, 5 February, www.moneyweb.co.za/mw/view/mw/en/page86?oid=66573&sn=Detail [ Links ]

Kaplan, K 2008. Study bolsters 'broken windows' theory of policing, Los Angeles Times, 23 November, www.policeone.com/drug-interdiction-narcotics/articles/1759042-Study-bolsters-broken-windowstheory-of-policing [ Links ]

Knox, D & Silcock, B R 2003. Research into unlicensed driving -Literature review. London Department of Transport, UK, Road Safety Research Report No 38. [ Links ]

Kockott, S R 2005. The development of a time-overspace management model for road traffic management. Magister Technologiae dissertation, Pretoria: Tshwane University of Technology, pp 26-29. [ Links ]

Newham, G 2006. Getting into the city beat -Challenges facing our metro police. SA Crime Quarterly, 15, www.issafrica.org [ Links ]

RTMC (Road Traffic Management Corporation) 2008. Road traffic report March 2008. www.arrivealive.co.za/documents/March_2008_-_Road_Traffic_Report_-_ March_2008.pdf [ Links ]

SA Good News 2008. Violent crime rates down, but still high. www.sagoodnews.co.za [ Links ]

Sapa 2010. SA roads 'most dangerous'. news.iafrica.com/sa/2304220.htm [ Links ]

Shaw, M 1998. The role of local government in crime prevention in South Africa. Occasional Paper No 33, Cape Town: Institute for Security Studies. [ Links ]

The Herald 2009. R1 bn boost for cops snubbed by Mbeki is offered to Zuma. 1 June, www.theherald.co.za/article.aspx?id=428623 [ Links ]

Thin slice of life 2008. Road rage. I: Aggressive driving. 2 January, www.thinsliceoflife.com/2008/01/roadrage-i-aggressive-driving.html [ Links ]

Wikipedia 2009. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fixing_Broken_Windowsanden.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudy_Giuliani [ Links ]

Contact details:

Contact details:

PO Box 34043 Newton Park Port Elizabeth

South Africa 6055

T: +27 (0)41 365 6467 F: +27 (0)41 365 6476

E: conrad@msba.co.za

| CONRAD BEZUIDENHOUT completed his National Diploma (Civil Engineering) at the then Port Elizabeth Technikon in 2004. He was employed at the local municipality, as a technician, for three years and completed his BTech (Transportation) at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) in 2007. In 2007 Bezuidenhout joined Madan Singh Bester and Associates in Port Elizabeth and continued his studies on a part-time basis towards his MTech (Transportation) at the NMMU. The studies were completed in 2010 under the guidance of Mr A Nagel (NMMU) and Ms K D Hogan (Wintec, New Zealand). Bezuidenhout is currently registered as a Candidate Technologist with ECSA and is a member of the Golden Key International Honour Society, and a graduate member of IMESA (Institute of Municipal Engineering of Southern Africa). | |