Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a27

ARTICLES

A Combustible Object: The Suppression and Recovery of Ernest Cole's photobook House of Bondage

Sean O'Toole

Independent writer, editor and curator based in Cape Town, South Africa. seanwotoole@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Ernest Cole's (1940-1990) much-admired photobook House of Bondage (1967) is considered a landmark event in South African photography. Composed of 183 photos organised into 14 chapters, House of Bondage punctured the tropes of primitivism, pictorialism and ethnography that had for long rendered black subjects as imaginative props for white photographers. It presents a dispassionate visual account of the miseries and insults of black urban life in 1960s South Africa. First published in New York in late 1967 and London in early 1968, it was banned from distribution in South Africa for 22 years. Drawing on primary research for a 2022 exhibition about the South African photobook, this paper looks at the historical context of book censorship, emphasising the under-researched chronology of events between House of Bondage's initial publication in October 1967 and banning in May 1968. It also discusses House of Bondage's post-apartheid recovery. An important leitmotif throughout is the subject of risk. What risk did Cole face in making his photobook? And, how did this risk further manifest after his book's publication?

Keywords: Ernest Cole, photobook, apartheid, censorship, documentary, risk.

Book censorship, and the underlying culture of political repression it gestures to, is largely a relic of South Africa's apartheid past.1 The country is now firmly part of a transnational book trade negotiating ontological and organisational change in the age of the Internet. Importers, booksellers and librarians are no longer compelled to refer to directories like Jacobsen's Index of Objectionable Literature, an alphabetical inventory of banned books established in 1956 by a commercial publisher that collated weekly prohibitions appearing in the Government Gazette.2 The culture of apartheid book censorship materialised in this always up-to-date directory of newly proscribed books materialised a Gutenbergian, or pre-Internet, conception of information flows, when printed books represented the apex of knowledge and its mobile distribution. It was this epistemic order that made books a key site of state worry and bureaucratic intervention. Undesirable publications, as was the expression of the time, needed to be controlled. Responding to newly promulgated censorships laws of 1963, Nadine Gordimer (1988:50), an author familiar with censorship, characterised the system as 'stringent, sin-mongering and all-devouring'. The censor's net, while porous, was not dissimilar to a drift net: it operated like a curtain of death. Vast subspecies of books were netted, including smutty novels, pamphlets on agrarian political organisation, homosexual literature and, germane to this study, photobooks.

Several notable South African photographers had their photobooks banned by the apartheid state, among them Omar Badsha (1945 -), Ernest Cole (1940-1990), Sam Haskins (1926-2009), Peter Magubane (1932 -) and Eli Weinberg (1908-1981). What, though, makes a photobook subversive? A working definition of the offending article, a 'photobook', is helpful in locating the remit of this question, as well as clarifying the focus of my essay. Concisely defined, a photobook is a printed and bound book principally composed of photographs that are ordered in sequence and sometimes graphically juxtaposed for effect.3 It may feature supplementary captions and/or longer pieces of explanatory text, but the image-text relationship is clearly weighted in favour of pictorial narrative. Photobooks are visual statements; cognition inheres in the photographic image, its singular presence as well as its operation as a deliberate assembly. Photographs shown in multiple, especially when there is defined narrative and/or theme, can be powerful tools of education, persuasion, propaganda and even agitation. As photo historian Darren Newbury (2013:226) notes: 'Apartheid was both constructed and opposed in visual terms.' Understood in this sense, the photobook, particularly when used as a vehicle of protest and tool of activism, presented the apartheid state with a burdensome object. But when exactly did such a troublesome book acquire the status of fissile matter in the eyes of the state, enough to motivate its prohibition from circulation?

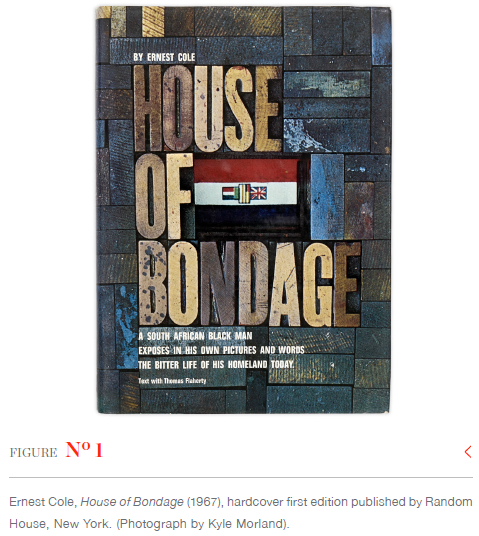

I propose to answer this question by looking at a single photobook: Pretoria-born photographer Ernest Cole's House of Bondage, first published in 1967 in New York (Figure 1). House of Bondage is a seminal book. Its publication, in the same year as Sam Haskins's graphically inventive but ultimately stereotypical African Image, punctured the tropes of primitivism, pictorialism and ethnography that had for long rendered black subjects as imaginative props for white photographers.4 House of Bondage was cosmopolitan and angry. It did not contain photos of smiling children and women in tribal dress. Its message of concerned urban witness still resonates. The book is one of only a handful of photobooks from or about South Africa included in Martin Parr and Gerry Badger's three-part survey, The Photobook: A History (2004-14). The authors describe Cole's book as 'a work of genuine quality ... as much sociological document as essay and polemic' (2006:107). Darren Newbury writes of House of Bondage that it is 'one of the most significant landmarks in South African photography' and 'a classic of the documentary genre' (Newbury 2009:207).

House of Bondage is also a book that straddles two temporalities. It presents a dispassionate visual account of black urban life in 1960s South Africa. Its banning - meaning prohibition from importation into South Africa - and belated retrieval in the period after 1994, more so after 2001, means it is also a book about the recent past. My essay negotiates these two time periods. First I am interested in the unexamined chronology of events between the initial publication of House of Bondage in October 1967 and its banning in South Africa seven months later. Contrary to the statements of Newbury (2009:205) and Sally Stein (2011:75), the book was not 'immediately banned'. It took months to arrive at this bureaucratic outcome, in which time Cole's book was actively promoted and reviewed internationally. My focus then shifts from the late 1960s to the near present. Here I am interested in the slow recovery of House of Bondage following its qualified unbanning in 1990. I am particularly, though not exclusively, interested in the period 1994 to 2001, when Cole's photographs were decoupled from the context of his book and exhibited in South African galleries and museums. This process, which liberated Cole's photographs from a book he had ambiguous agency in fully calling his own, finally placed his photos in full view of especially black South African viewers. Their response is instructive.

These are the specifics of my essay, but I am also motivated to write about Cole and his remarkable book out of a more generalised interest in art and risk. Book publishing is a commercial enterprise, but it is not reducible to this. It is also a creative act. What is the risk, other than financial, of making a photobook? Cole used tactics of deception, subterfuge and creative hustle to enable his project. What risks did he face in making his photographs of petty crime and police brutality in Johannesburg, and later in New York when organising them into a book? How did the reception and interpretation of his book amplify the risks he took in photographing scenes of black urban life? Did he foresee banishment and a death in exile? Risk, as will become clearer, is an elastic concept, something that exceeds the obstacles and difficulties that attend a vocation fundamentally about, in Cole's case, showing the experience of black oppression and misery. When does risk, in such a context, become heroic or politically subversive, and to whom? The answer to these questions is, in part, bound up in an understanding of the practice of censorship.

Censorship and Risk

Book censorship and the attendant culture of resistance it inspired, particularly in the period of National Party rule (1948-94) in South Africa, has been the subject of exhaustive academic study.5 I do not propose to revisit this history, which is both fascinating and depressing. It is, however, important to understand the historical context of this system and its operating logic. A brief sketch will suffice. The regulation of access to information, in particular through printed books, periodicals and pamphlets, predates the rule of the ideologically conservative National Party. The first governmental Board of Censors was established through the Entertainments (Censorship) Act of 1931, with the task of policing films and other forms of pictorial representation; books were brought into its purview in 1934 (McDonald 2009:21). This administrative system of state review ensnared many books, more so after 1948. The volume of books seized in the period 1955 to 1971, notably from public and commercial libraries, presented an issue of storage, resulting in thousands of books and other forms of reading material being burned at municipal incinerators and furnaces (Dick 2005:10).

The regime of book burnings is expressive of tightening state controls. In 1954, prompted by the publication of articles on prostitution in two Afrikaans magazines, the government of Prime Minister D.F. Malan established a state commission to investigate the handling of 'undesirable publications'. Sociologist Geoffrey Cronjé, an influential white nationalist intellectual and foundational theorist of apartheid, was tasked with leading the commission (Coetzee 1991:2). The terms of Cronjé's findings, contained in his Report of the Commission of Enquiry in Regard to Undesirable Publications, formed the basis of the Publications and Entertainments Act of 1963. The legislation 'broke new ground' (McDonald 2009:32) by making the publication, printing or distribution of undesirable materials produced both locally and abroad a statutory offence, punishable by severe fines and prison sentences. Cole was aware of this. 'I knew that if an informer would learn what I was doing I would be reported and end up in jail,' the photographer wrote of his activities gathering material for House of Bondage (Cole 1968:69).

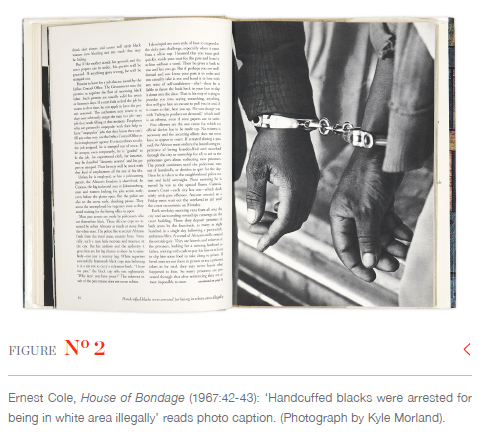

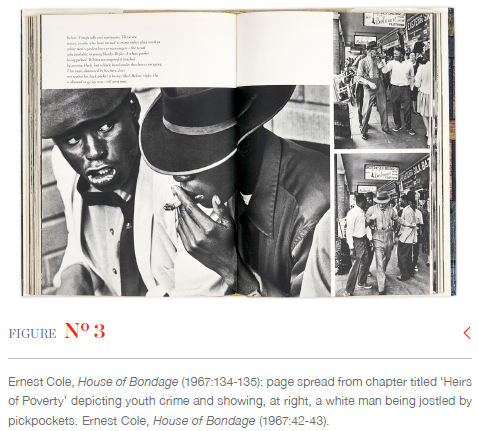

Notwithstanding the vicious crack of the whip signalled by the 1963 legislation, its operation was neither Orwellian nor Stalinist: the state did not require pre-publication approval, but rather relied on after-the-fact adjudication. This is important to register. The nearest historical model for what pertained in South Africa, writes literary historian Peter McDonald, was pre-revolutionary Russia, not the Soviet Union. 'Like the system established by the nineteenth century tsars, apartheid censorship operated under a semblance of legality, not through a series of secret strictures and directives: it was essentially prohibitive, rather than prescriptive, and most importantly, it functioned post-publication' (McDonald 2009:12). The system was essentially transactional, which didn't exempt Cole from other laws and dogmas regarding black South Africans in urban areas. Cole was seen, harassed and threatened while documenting the 'flows of power, survival and criminal resistance,' notes photographer Allan Sekula (1986:64). 'He was questioned repeatedly by police, who assumed he was carrying stolen camera equipment.' The police stopped Cole while photographing passbook arrests (Figure 2) on numerous occasions; sensing opportunity, they attempted to co-opt him as an informant (Cole 1967:172). He was also arrested for photographing a mugging by black men of a white man and pressed to reveal their identity; the event forms part of a larger sequence on street crime in his book (Figure 3).

As mentioned earlier, the apparatus of post-publication review ensnared many photobooks by South African photographers, although they were not the sole targets of state censure. Sex, sensuality and eroticism troubled the censor as much as liberation politics. American photographer Will McBride's sex education book Show Me! (1975), which included photos of young children discovering their sexuality, was banned. But the censorship system was riven by 'vagaries of taste' and 'crude arbitrariness' (McDonald 2009:12), as is apparent in the free pass given André Brink's execrable photobook Portret van die Vrou as 'n Meisie (1973). A book of two parts, it is dominated by Brink's calculated6 attempt to visualise the sexuality of early-teen girls in a quasi-mystical resister that aspires to the adjective Nabakovian.

Brink's book shares a marked affinity with British photographer David Hamilton's photobook Dreams of a Young Girl (1971), which includes an essay by French writer and filmmaker Alain Robbe-Grillet, a canonical writer for Brink.7 Hamilton's books of naked adolescents portrayed in soft focus were for a time banned in South Africa. This leads me to a larger point. There is no authoritative history of the photobook in South Africa, nor is there a comprehensive review of which photobooks were banned by apartheid authorities in the second half of the twentieth century.

These two areas of enquiry - the first essentially quantitative, the latter qualitative - are divisible. However, in 2020, when I embarked on a research project to investigate the archive of South African photobooks produced in the period 1945 to 2022 for an exhibition at A4 Arts Foundation,8 I was struck by both the apartheid state's willingness to use the photobook as a propaganda tool and, conversely, its active intervention against photobooks regarded as subversive propaganda. Along with House of Bondage, other notable books banned for this reason were Omar Badsha's Letter to Farzanah (1979), Peter Magubane's eponymous Magubane's South Africa, which was published in New York in 1978, and Eli Weinberg's Portrait of a People (1981), published by the London-based International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa (IDAF). Apartheid censorship was relational and vindictive.

Fatima Meer's Institute of Black Research published Badsha's debut photobook. Meer, an anti-apartheid activist, academic and author of the photobook Portrait of Indian South Africans (1969), was at the time a banned person. Weinberg, a trade unionist and member of the banned Communist Party of South Africa, was constantly harassed and detained before he went into exile in 1976. Magubane was plainly disliked by the apartheid state. He was arrested in 1957 and 1969, banned in 1970, detained for extensive periods in 1971 and 1972, and arrested again in 1976 while covering the Soweto uprising.

The first noteworthy photobook (for the purposes of this study) referred to apartheid censors was Five Girls (1962) by Kroonstad-born Sam Haskins. The South African photobook was a sedate and parochial vehicle for delivering photographs before Haskins, an accomplished commercial photographer with a refined graphic sensibility, published Five Girls in London and New York. The book comprises diligently lit and inventively choreographed nude portraits of five white women photographed by Haskins in his Johannesburg studio. Five Girls plainly presents 'intimate description[s] of women's bodies', which was one of the 18 possible offending values constituting an indecent, obscene or objectionable publication listed in form D.I. 160 used by censors in the early 1960s.9 Five Girls was nonetheless approved for single importation, and again in 1967 following a similar review. However, in 1969, a year after Haskins emigrated in London to further his career, Five Girls was banned. It is unclear why. His book appeared in the alphabetical listing of Jacobsen's Index shortly after an English-language edition of Mao Zedong's Five Documents on Literature and Art, which was published in the same year as Cole's House of Bondage.

Cole's development as a photographer

Ernest Levi Tsoloane Kole was born in Eersterust, a segregated settlement on the eastern outskirts of Pretoria, in 1940. His beginnings as a photographer were as a teenager. He apprenticed with a Chinese photographer and placed his earliest photographs in Zonk magazine. In 1958 he joined Drum, an influential monthly magazine aimed at metropolitan black readers, where he initially worked as a darkroom assistant under photographer Jürgen Schadeberg. In 1960 Cole went freelance. He contributed photos to a variety of South African newsweeklies, including Bantu World, Drum, Rand Daily Mail, Sunday Express and Zonk (Powell 2010:24-29). His more political work was published internationally, notably in the New York Times. Darren Newbury has extensively detailed the assignments and press contacts that informed Cole's pre-exile photography, and how they provided the architecture for his book. Newbury (2009:180) states that the articles American journalist Joseph Lelyveld published in the New York Times 'contributed substantially to the construction of the text for House of Bondage,' as well as 'served as vehicles for Cole's photography'. My essay builds on Newbury and critic Ivor Powell's vital research on this period in Cole's biography.

Frustrated by the travel restrictions imposed on black citizens, Cole in 1965 had himself reclassified as 'Coloured', enabling him to move freely and also receive a passport. Cole left his homeland in 1966 on the pretence of visiting Lourdes, a major Catholic pilgrimage site in France. In this regard Powell (2010:39) writes that, 'Cole effectively had to engage in systematic deception to go undercover...In order to be the self he perceived himself to be, he became or presented himself as being what he was not.' Cole initially travelled to London, arriving on 11 May 1966. He placed work with the Sunday Times Magazine. He also spent some time in Paris and Copenhagen. He arrived in New York on 10 September 1966.

House of Bondage was prepared and produced in New York. The new book's title was not original. The phrase 'house of bondage' appears frequently in the Christian bible. Its meaning was transposed to speak to the antebellum and reconstruction periods before and after the American Civil War (1861-1865). Cole's book shares its title with teacher and social activist Octavia V. Rogers Albert's well-regarded The House of Bondage, a compilation of personal narratives of former slaves published in 1890. The resonant meaning of this phrase had not fallen out of memory by the time it was appropriated for Cole's book, and indeed retained its piquancy and utility long after - as is clear from the insurgent language of James Baldwin's well-known 1980 essay 'Notes on the House of Bondage'.10

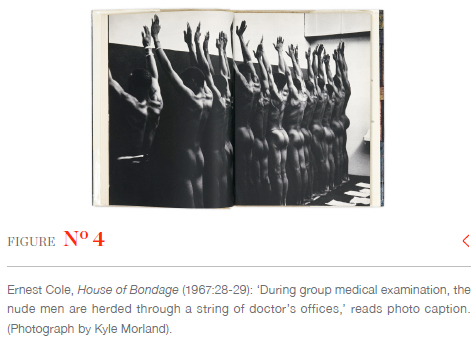

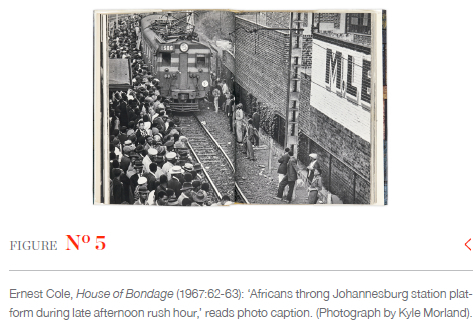

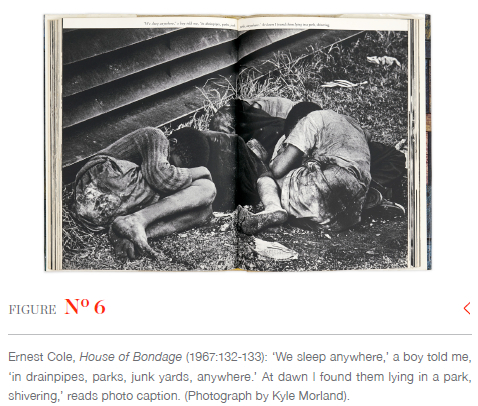

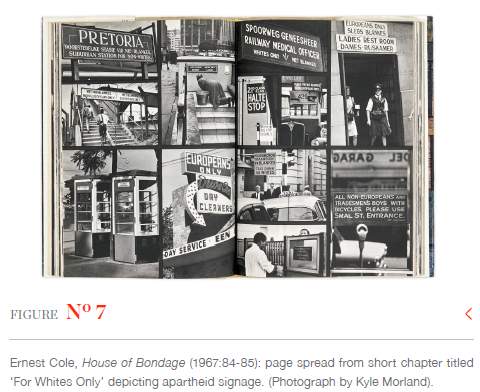

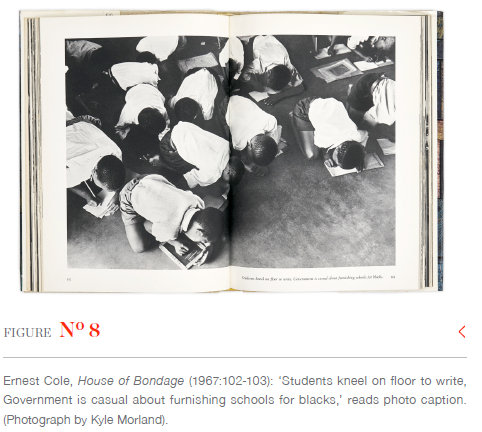

In its original hardcover American edition, House of Bondage comprises 183 photos organised into 14 chapters, each introduced by a brief explanatory text. 'Today I think the split between black and white in South Africa is irreconcilable,' reads the opening sentence of the first chapter, headlined 'The Quality of Repression' (Cole 1967:20). It is presented without photos and offers the clearest sense of Cole's intentions, emotions and broad sense of his project as a record of the consequences of white settler colonialism. The following chapter, entitled 'The Mines', portrays 'pensive tribesmen' (Cole 1967:24) decked out in threadbare contemporary fashion being assimilated into the country's mining system. A full-bleed image of 13 young mine recruits, all of them naked, hands raised in the air and pressed close to a black wall, ready for a medical inspection, has become one of Cole's defining images from House of Bondage (Figure 4). In broad overview, Cole's photographs visualise the hopelessness and misery confronting black South Africans living in the urban centres of Johannesburg and Pretoria. His photos show crowded train commutes (Figure 5), brutal work circumstances, predatory credit systems, atomised family relations, impoverished schools, youth delinquency (Figure 6), police harassment and bullying municipal signage (Figure 7). The dominant rhetorical mode is documentary witnessing witnessing, but is informed by the methods of photojournalism.11 Collectively, Cole's photos operate to visualise what he, in the first chapter, describes as the 'extraordinary experience to live as though life were a punishment for being black' (Cole 1967:20).

Cole worked with a team of associates on his book. They included Life magazine editor Thomas Flaherty, who ghost wrote the chapter texts. These texts provide sociological insight into South Africa in an awkward first-person register. The pronoun 'I' nominally inserts Cole's voice into the texts framing an appreciation of his photographs. Cole in fact approached exiled journalist and poet Keorapetse Kgositsile to write the introduction. 'He wanted a South African to write the text, someone who knew clearly what informed the photographs,' confirms Kgositsile (Knape 2010:232). Instead Lelyveld, who had been expelled from South Africa, wrote an introduction from his new posting in India. These and other compromises contributed to the photographer's sense that 'he had lost control of his material' (Stein 2011:75). To be sure, Cole is often an anonymous cipher in the book's texts but the opening of his final chapter retains its force, especially given the state's response to the publication of Cole's book: 'Banishment is the cruellest and most effective weapon that the South African Government has yet devised to punish its foes and to intimidate potential opposition' (Cole 1967:176). I will return to this subject, which animates my sedimented enquiry into risk.

At no point in Lelyveld's introduction does he address any particular image appearing in Cole's book. His preferred discursive mode is sociological overview, which he leavens with journalistic reportage. 'It is a universal phenomenon of oppression that the oppressed see their circumstances more clearly than the oppressors,' writes Lelyveld (1967:10). After a lengthy rehearsal of his experiences and insights reporting in South Africa, Lelyveld turns to Cole. He discusses their meeting, Cole's frustrations moving in a highly regulated city, the elaborate subterfuge of getting himself racially reclassified, and his decision to work on a photobook. Cole, Lelyveld declares, understood the risks involved: 'Ernest realised from the beginning that he would have to leave the country before the book could be published. It seemed a big enough risk to have isolated pictures of his appearing in various foreign magazines and newspapers. Publication of a book would finish him in South Africa' (Cole 1967:19).

The publication of House of Bondage duly achieved this. Cole's book was deemed undesirable by a proclamation appearing in the Government Gazette of 10 May 1968. Censorship is a noun that refers to an active verb, to censor, which infers a process of discovery, examination and agreement to suppress. What provoked the censors to ban House of Bondage? In the absence of a definitive material statement in the archive, it is useful to consider the combustible time in which his book appeared and the media coverage it attracted. As will be become clearer in the next section, I am essentially aiming to establish cause and effect. It is necessarily speculative as there is in no summary statement answering what precisely made House of Bondage an undesirable publication, its author's efforts deserving of the punishment of banning.

Alienated and Isolated

In August 1966, the Brazilian government, in conjunction with the United Nations, hosted a two-week seminar in Brasilia to discuss South Africa's state policy of apartheid. South Africa's white-minority government did not to attend the event, but artist Selby Mvusi and journalist Lewis Nkosi did. In a detailed report on the seminar, Nkosi quotes (1966:185) another South African exile and seminar attendee, journalist Colin Legum:

Power and privilege always go together, and it is fairly pointless to appeal to a privileged society to abandon its power knowing that in doing so it will condemn itself to the loss of its privileges...The greater the privileges of the society, the greater the incentive to rally to its defence.

A few days after this milestone event in the international struggle against apartheid, a parliamentary orderly, Dimitri Tsafendas, fatally stabbed Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd in Cape Town.

Vewoerd's death was galvanising for white nationalists, who became more repressive, vindictive and certain of their mission. It also unleashed an exaggerated pageantry of mourning and remembrance. Long before roads, tunnels, dams and municipalities were named after Verwoerd, Voortrekker Press, publisher of Die Transvaler, a hardline daily formerly edited by Verwoerd, issued a visual biography devoted to the murdered leader. Compiled H.F. Hefer and C. Basson, it utilised standard rhetorical devices of mid-century photobooks - dynamic layouts, irregular image sizing, juxtaposition and bleeding of photographs off the edge of the page, all constitutive elements of House of Bondage - to make its point. That point? 'Verwoerd will go down in history as one of the country's greatest men,' opens the anonymous obituary notice, which an endnote tells was first broadcast on state radio following Verwoerd's death (Hefer & Basson 1966:6).

House of Bondage appeared in a febrile context of internal agitation and growing international censure. Published by Random House in the United States in 1967 and in the United Kingdom by Penguin in 1968, House of Bondage received considerable press. The Book Review section of the New York Times (8 October 1967) devoted two full pages to showcasing seven photos from Cole's new book. The spread included his photo of prospective mineworkers submitting themselves naked to a medical examination, a close up of the manacled hands of two black men arrested for illegally being in a white area, and a top-down view onto a group of schoolboys kneeling on a furniture-bereft cement floor writing into notebooks and onto small chalkboards (Figure 8). The photos include explanatory captions. A summary overview quotes from Lelyveld's introduction to House of Bondage, offering that Cole's book is a portrait 'of the black man trapped in someone else's dream, able only to wait for the dreamer to wake or be wakened'.

On 3 December 1967 Cole's book was listed in the New York Times' influential end-of-year Christmas list of books. Book promotion is not criticism, even if the line is sometimes hard to clearly draw. House of Bondage did however receive promising reviews. Two South African intellectuals living in exile contributed to the growing critical reception. Daniel Pule Kunene, a Free State-born writer, literary scholar and translator living in the United States, published a review in the Los Angeles Times (December 1967).12 Dan Jacobson, a Johannesburg-born author living in London, authored a review for The Guardian (28 March 1968):

Anyone who looks into the book will at once be aware of the photographer's lack of sentimentality, his tenderness, his anger, his wit...He [Cole] has photographed his people everywhere - in the streets, in the mines, in the homes of their white employers, in their own homes. Deprivation and discrimination are shown to us for what they are.

Like Gordimer, Kunene and Jacobson took principled stands against censorship throughout their careers. Jacobson went on to edit the London-based magazine Index on Censorship, which advocated for free expression. In 1981, Kunene (1981:235) likened book bans to the imprisonment of ideas: 'This time, however, it is ideas which are arrested and kept in solitary confinement in the hope that they will somehow wither and die before they contaminate the rest of society'. Here Kunene also characterises bans as 'a mark of authenticity on the part of the writer, a sign of confrontation with the power structure'. Cole was aware that his book would stage a confrontation with the power structure of the apartheid state. It is clear from an essay in his name accompanying a feature of his photos in Ebony magazine (February 1968).

Founded in 1945, Ebony was an influential monthly magazine aimed at African-American readers. It had distinguished itself for its diverse editorial content, strong use of visuals and, in the 1960s, coverage of the civil rights movement. It allocated five and a half pages to Cole's book. As with the text in House of Bondage, Cole's essay reads as overly directed and edited, but is nonetheless insightful and also, at moments, revealing of Cole's charged emotions. It begins procedurally:

Yes, South Africa is my country. But it is also my hell. For the first 26 years of my life, I was one of the 13 ½ million black people who live (or should I say 'exist'?) under a system that takes away their rights as human beings and uses them as 'things' to do the menial labour for some 3 ½ million whites who control the government, the economy, the army and the police of the fifth richest nation in the world (Cole 1968:68).

The essay rehearses many ideas and biographical details appearing in Lelyveld's introduction to House of Bondage. However, some sentences read as if directly spoken by Cole. 'The whole system, based on white supremacy, taught me to hate, to steal and to lie. Looking back on it now, it seems that I almost had to be in a trance to exist within the system' (Cole 1968:69).

Cole uses his Ebony essay to address omissions and inaccuracies in Lelyveld's introduction to House of Bondage. He acknowledges the key influence of Schadeberg, describing him as a pioneer of 35mm photographic film. For Cole (1968:69) it was the gift of Henri Cartier Bresson's photobook The Decisive Moment (1952) - not the photographer's People of Moscow (1955), as stated by Lelyveld - that 'shaped my purpose in life'. Cole (1968:69) continues: 'I knew then what I must do. I would do a book of photographs to show the world what the white South African had done to the black'. Such an enterprise would surely not go unpunished?

After all, viciousness was a hallmark of the apartheid state's operation. Cole knew this from the scope of his final chapter of House of Bondage, which deals with the rural banishment of black political leaders.

Earlier on in this essay I asked what risks may accompany the making a photobook? Cole used the platform provided by Ebony to explicitly deliberate on the risks he took in gathering materials for his book when he writes: 'I knew that I could be killed merely for gathering the material for such a book and I knew that when I finished, I would have to leave my country in order to have the book published' (Cole 1968:69). Implicit here is Cole's understanding that he could not publish his book in South Africa. But Cole also knows that the publication of House of Bondage abroad could conceivably render him homeless, although not in the way of Basotho leader Paulus Mopeli, who Cole photographed in banishment in Frenchdale in the Northern Cape. Cole (1968:69) is contemplating a different banishment when he writes: 'once that book was published, I could never go home again so long as the whites, Boers or Englishmen, Nationalists or Progressives, remain in power.' The terms of Cole's statement here are clear: his is a Napoleonic exile. 'Exile is a dream of a glorious return,' writes Salman Rushdie (1988:205). 'Exile is a vision of revolution: Elba, not St Helena.' New York, though, would be Cole's St Helena, a place of punitive exile and ultimately death. Risk, though, is not a singular concept, at least not with Cole: it is cumulative, always metastasising.

Consequences

The risk in exposing a state 'unwilling to voluntarily surrender its privileges' (Nkosi 1966:185) produced two stark outcomes for Cole: censorship and banishment. In his Pulitzer Prize-winning book Move Your Shadow, Lelyveld (1985:16) writes that House of Bondage 'had more impact than such books normally have when its was published in America and Europe'. He does not elaborate what he means by 'impact'. One cannot downplay the important press Cole's book received. But, in saying this, it is also unclear what role all the press for House of Bondage played, firstly, in bringing the photobook to the attention of the apartheid state's numerous functionaries involved in information peddling and reputation management abroad, and, secondly, if this press directly prompted a review of House of Bondage by state censors. The government-appointed censorship board's deliberations were always held in secret. A 2022 search I undertook at the National Archive in Cape Town, which holds the extant papers of the censorship board, yielded a meagre yield in the form of a reader's report concluding the book 'is not undesirable' (Du Toit 1990:2).13 Some moderate speculation may thus be in order.

Book markets are regional. Apartheid censors tended to punish books flowing down the pipeline from London, which has historically catered to the commercial territory of South Africa. The original Government Gazette notice does not make clear which edition - the American or English, which resembled each other physically - was banned. Given the mood of the time, it would likely have meant both, even if legally it probably referred to the latter English edition from 1968. This reasoning is suggested by the 1990 motivation to unban the 1968 Penguin edition of Cole's book. But this piece of context does not answer why the book was banned, merely which version was legally proscribed.

Perhaps a growing awareness of trans-Atlantic media interest in Cole's work formed the basis of clippings compiled in state dossiers? This was, after all, an analogue era predating even the fax. International news would certainly have taken some time to filter back to Pretoria - life was governed by different protocols and temporalities before the Internet. A prickly report on House of Bondage by JB. du Toit (1991), a reader for the Publications Control Board, more directly hints at what offence the book might have presented in 1960s South Africa. The report, which was a necessary step in reclassifying the status of Cole's book, is prefaced by a summary introduction to Cole and description of his book's content. 'From the introduction through all the descriptions, and the accompanying photos, there is a thread of sharp criticism with sometimes also sarcastic and disparaging comments about apartheid and the whites in South Africa,' states Du Toit (1990:1).14

What remains striking about this report, and indeed much of the early writing around House of Bondage, is the lack of any defined engagement with single examples of his photos, as would be the case with literary analysis. Words are prioritised, mostly Lelyveld's words; Cole's photographs are largely read in overview, as a collective statement, with captions detailing context. This has started to change. An important part of this retrieval of the singular involves acknowledging Cole's engaged, risk-inviting point of view. In a 2010 biographical essay on Cole, Ivor Powell - obliquely skirting Allan Sekula's influential appreciation of Cole's book and proposal that 'not all realisms necessarily play into the hands of the police' (1986:64) - discusses how Cole differed from New York photographer Weegee. Powell writes that one is always aware of Weegee, well known for his crime and paparazzi photos made with a flash, as the photographer and player. 'The resulting images record Weegee being there as compellingly as what is happening on the other side of the lens. Cole operates at the other end of the scale. He photographs like a spy or secret agent' (Powell 2010:41).

I wrote earlier that photobooks are visual statements, and that cognition inheres in the photographic image. It is inherent but also latent. A photograph's latency requires words to induce its inherent attributes, which is why there is such a strong inclination to pull at the words surrounding Cole's photographs, to yoke them in service of animating what is instantaneous, cumulative, without words - his photographs. Quite possibly the shock of being spied on, so methodically, so clandestinely, without trace of ego, of being seen, clearly, without guile, is what offended censors? But this perhaps goes beyond moderate speculation and interpretation.

Censorship is consequential. The maker of a banned book is unavoidably marked by the state, made distinguishable. 'Martyrdom, heroism and honour for the banned become the medals for their meritorious service,' wrote Kunene. 'Many even feel left out if they are not touched by it' (Kunene 1981:235). This is a somewhat romantic conception of censorship. Cole's request in May 1968 to renew his South African passport was declined, leaving Cole stateless. If risk operates in a continuum, this was another expression of its dynamic outcome. The Swedish government extended him residential status in 1969 (Knape 2010:234-236), inaugurating a restless period of travel between Stockholm and New York. The Ford Foundation was a major patron until 1971, funding a study of two black American families from contrasting rural and urban backgrounds. The project was posthumously published in 2023 under the title The True America. Cole's career began to dwindle around 1974. He fell into penury and stopped making photographs. 'Cole has disappeared from the world of professional photojournalism,' wrote Sekula a decade later (1986:64).

Rediscovery

Cole died in exile in New York on 19 February 1990, shortly after National Party leader FW. De Klerk initiated a political détente in South Africa by unbanning various political parties and announcing the release of political prisoners. Two months later, the Du Toit report on House of Bondage was sent to the Publications Control Board with the motivation that it be reclassified. 'To some extent, several of the representations (photos depicting apartheid) or statements about discriminatory laws are based on conditions that have changed and a dispensation that does not exist, or is in the process of changing,' writes Du Toit (1990:2).15 The unbanning was conditional. It was stipulated that copies of House of Bondage be confined to university libraries only. This order meant that House of Bondage, which had been shielded from public view in South African for 22 years, remained largely unseen in the country it was about.

Much in the way that unread books have no power, unseen images convey no facts and possess no aura. But book censorship, a monolithic idea, has to contend with the multiplicity of its target. Copies of House of Bondage did find their way into apartheid South Africa. Omar Badsha told me how he first encountered Cole's book at David Goldblatt's home in Johannesburg in the mid-1980s, while overseeing an exhibition project for the Second Carnegie Inquiry into Poverty and Development in Southern Africa.16 The exhibition, held in Cape Town, included an accompanying photobook. Writing in the preface to South Africa: The Cordoned Heart (1986) Badsha (1986:xvi) states of Cole's book, 'its influence on young photographers who had had access to it has been immense'.

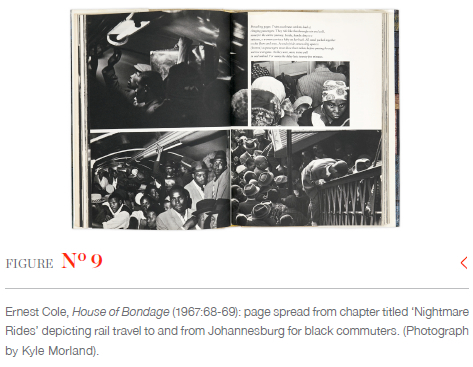

The influence of Cole's photobook endures. In 2021, photographer Lindokuhle Sobekwa (2021:64) wrote of his discovery of Cole while studying photography as a 17-year-old schoolboy in Thokoza, a township near Johannesburg. He became obsessed with House of Bondage, its imagery, not the words that explain them. In his essay Sobekwa singles out an image showing the interior of an overcrowded commuter train that takes up half of page 68 and is crowded by three other images of congestion (Figure 9). Sobekwa (2021:64) states: 'Cole's ability to tell a whole story in a single image (or, in the case of that photograph, so many stories in one image) was incredible, as was the sensitivity and deep concern he had for the people he photographed'. I had not personally paused at length on this photo of mostly men, some wearing fedoras, until reading Sobekwa, but I can appreciate his fascination. What is the appropriate synonym for this mute assembly of expressionless commuters? Not mob, not horde, not rabble, the right word seems somehow elusive. 'The emotion and exhaustion that shows in each and every face in that picture tells you everything you need to know about the conditions that black people endured under apartheid,' writes Sobekwa (2021:64).

This pictorial analysis, fleeting but pointed, speaks to a process of study and recognition that has been a hallmark of Cole's retrieval in the post-apartheid years, especially among black South Africans. An important and symbolic event in the recovery and rediscovery of Cole's House of Bondage dates to the winter months immediately after the first democratic vote in 1994. The exhibition From Margins to Mainstream: Lost South African Photographers marked the first known instance of Cole's photos being exhibited in South Africa. Curated by Gordon Metz, an activist and former IDAF member, the exhibition brought together six early practitioners of social documentary photograph. In addition to Cole, these photographers were Willie de Klerk, Bob Gosani, Ranjith Kally, Leon Levson and Eli Weinberg.

From Margins to Mainstream debuted at the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown before travelling to Johannesburg's Newtown Galleries. In 1995 the exhibition travelled to London, for Africa '95, a Britain-wide festival of African arts.17 The exhibition served both a memorial and corporate purpose. In 1990, IDAF donated a substantial amount of visual material to the newly constituted Mayibuye Centre at the University of the Western Cape. The 1994-96 exhibition of lost photographers helped 'locate the Mayibuye Centre and its visual archive, [which] cohered around Levson and Weinberg, at the heart of resistance social documentary photography in South Africa' (Minkley & Rassool 2005:186). Cole was not a central focus of From Margins to Mainstream; rather, and in a manner not dissimilar the unspecific reading of the photos in his book, his work was located within a continuum of social documentary photography that predated the explicitly activist and resistance photography of the 1980s.

A similar sense of co-operative meaning and collective recovery marks Cole's appearance in the permanent exhibitions of the Apartheid Museum in South Africa. Cole's photographs form part of an extensive archive of photographic material used to inform and animate the histories told within this private museum attached to a casino on the south-western edge of Johannesburg's historic CBD. The museum was not uncontroversial when it opened in 2001. For starters, it was built in fulfilment of a tourism-stimulation clause attached to the granting of casino licenses by the Gambling Board. It was also revealed that the casino's founders, twin brothers Abe and Solly Krok, manufactured toxic skin lightening agents through their company Twins Products during the apartheid years (Thomas 2012:259). All of this was grist to the mill for news commentators.

Writer and actor John Matshikiza, son of the renowned Drum journalist and composer Todd Matshikiza, detailed much of the foregoing in a 2001 column in the Mail & Guardian. Matshikiza begins his commentary with a question about the timeliness of opening a museum devoted to apartheid. Matshikiza asks (2001:19): 'Are we really ready to announce the end of apartheid? Are we confident enough to encapsulate it as a piece of dead history and turn it into a museum piece, as distant as the mummified remains of Egypt, Greece and Rome?' Writing in a populist voice, not an academic register, as a polemical journalist not a scholar, Matshikiza uses his column to detail the experience of entering the museum, designed by Mashabane Rose Associates. He marvels at the diligently reproduced bureaucratic signage that in House of Bondage is the subject of a brief chapter titled 'For Whites Only'. The unfolding narrative inside the museum perplexes him. Using his pulpit to grouse, Matshikiza (2001:19) wonders if the museum 'is about apartheid or about the history of Johannesburg, the white founders, the black resisters, and Nelson Mandela's long walk to freedom'.

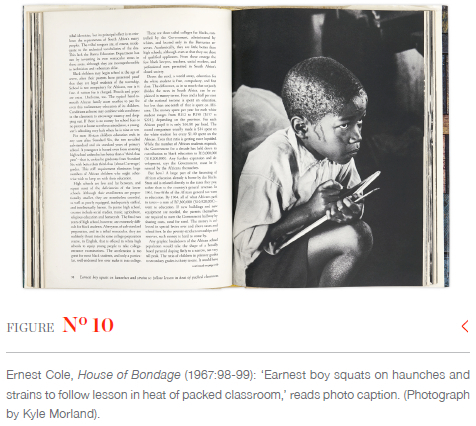

Matshikiza's jovial and practiced cynicism abates in the permanent exhibition. It includes key photographs by Cole, among them the much-publicised photos of a medical inspection and handcuffed hands, both mentioned previously, as well as a three-quarter portrait of a young schoolboy, sweat beads streaking down his face, engrossed by a lesson in an overcrowded classroom (Figure 10). In Matshikiza's (2001:19) opinion, the central issue of the museum is pulled into sharp focus by Cole's photography: 'Each of Cole's startling black-and-white images carries the power of a carefully judged painting telling the whole truth, in all its bitterness, but invested with a certain spiritual beauty. Here, at last, we come to grips with what apartheid really meant - the numbing, humdrum horror of a black person's daily existence'.

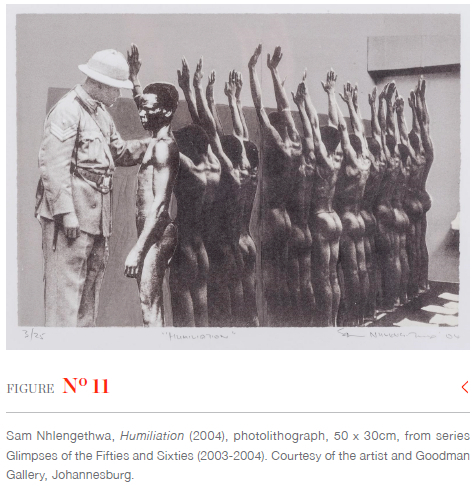

The Apartheid Museum remains a persuasive tool for introducing new audiences to Cole. A prominent South African bookseller I interviewed18 told me that House of Bondage is her store's most requested photobook - principally by American tourists willing to volunteer the high prices commanded for an original American edition (the launch price in 1967 was $10). But Cole's book has decisively returned home. Its contents are now the subject of local deliberation, occasionally even intervention. In 2004, for his exhibition Glimpses of the Fifties and Sixties, artist Sam Nhlengethwa produced a series of collages combining personal family photographs with cut-ups of lithographic copies of photographs by Drum's seminal cohort of Cole, Magubane and Schadeberg. House of Bondage is extensively quoted in Nhlengethwa's collages. One particular collage, Humiliation (2004), reproduces Cole's photo of naked mine recruits, hands aloft, but also somehow makes it starker, more violent. Nhlengethwa achieves this by overlaying an element from another Cole photo from House of Bondage, an image of a uniformed black policeman doing a passbook inspection. This element from a larger image on pages 44-45 is overlaid onto a corner of the composition (Figure 11).

Nhlengethwa's unsanctioned use of Cole's images in his collages ties into a history appropriation in the visual arts throughout the twentieth century. More pointedly, it rehearses a strategy adopted by artist Gavin Jantjes in A South African Colouring Book (1974-75), an influential portfolio of eleven screenprints produced in Hamburg, Germany. A fusion of various trends in art at the time, including agit-prop graphics, Pop Art and the open-source attitude of the emergent Pictures Generation in the United States, the series visually introduces aspects of apartheid South Africa 'as if one were explaining something to a child' (Young 2017:14). Four works in the portfolio substantially feature Cole's work, which Jantjes re-photographed from a copy of House of Bondage while in London (Jantjes 2018).19 Nhlengethwa's collages from his Glimpses of the Fifties and Sixties exhibition are linked to this history, and also expand on it. Works like Humiliation evidence a more interventionist attitude to Cole's photographs than is the case with Jantjes. By suturing together various images, Nhlengethwa points to the relational and unifying operation of Cole's scenes, how his figuring of the visible instances of oppression also reveals its superstructure, which endures.

Both Matshikiza and Sobekwa, thinking through and in alliance with Cole's photographs, two decades apart, arrive at this same point: the superstructure endures. Matshikiza is eloquent about the largely unreformed nature of South Africa - 34 years after the publication of House of Bondage and nearly a decade after the first democratic election - when he writes:

The apartheid notices have come down, but black life is not much different from the images that strike at you out of Cole's'. Life is better for the men on the mines, but the monstrous complex of Baragwanath, and the monstrous sprawl of Soweto that surrounds it, are still the same social and medical nightmare. Hopeless poverty and hopeless disease still walk hand-in-hand. Black maids and nannies still sit in hopeless contemplation in the same servants' quarters up in the sky, or out back, near the drains and the dog kennels. On Sundays they still pray for pie in the sky (Matshikiza 2001:19).

Unlike Matshikiza, who was born into middle-class family with urbane struggle credentials, Sobekwa had a difficult upbringing in a single-parent home. His mother was a jobbing domestic worker who attempted to stave off 'hopeless contemplation' in a backyard that Matshikiza writes about (Figure 12). Sobekwa occasionally visited his mother at work in Daleside, between Alberton and Vereeniging. It has enabled him to recognise in Cole's photos what remains a fact of life for many black South Africans. 'As a "born free" who grew up after the end of apartheid, I can still connect and relate to his work and experience,' writes Sobekwa. 'We were both black children growing up in the townships. Conditions may have since changed - but not enough' (Sobekwa 2021:64). To put it in simpler terms, the past endures. There is a tenacious fixity in the circumstances of the majority of black South Africans. In this sense, Ernest Cole's House of Bondage, which for decades was treated as a combustible object, remains an instructional document, as much about the present as it is visibly about the past.

Notes

1 A statement by Nadine Gordimer from a 1980s essay informs my logic here: 'We shall not be rid of censorship until we are rid of apartheid. Censorship is the arm of mind control and as necessary to maintain a racist regime as that other arm of internal repression, the secret police' (Gordimer 1988:210).

2 There is little substantive scholarship around this subscription-based commercial publication, which was updated with loose-leafed inserts and is still extant (now known as Jacobsen's Prohibited and Restricted Goods Index); the best elaboration of its workings remains Gordimer (1975:121-124) and Duke (1988:8). See also Attwell (2015:56) who discusses J.M. Coetzee's in-depth reading of Jacobsen's Index in 1972 and its relatedness to an abandoned novel entitled 'The Burning of Books'. Rosa Lyster (2018:123) correctly notes, 'A grasp of the censors' conception of the literary, and why they made the decisions they did, cannot be gleaned simply from looking at the list of banned titles in Jacobsen's Index'.

3 'A photobook is a book - with or without text - where the work's primary message is carried by photographs,' offer Parr and Badger (2004:6); see also Campany (2014:3): 'The term "photobook" is recent. It hardly appears in writings and discussions before the twenty-first century'.

4 See Enwezor and Zaya (1996:22-26) and Bank (2001:43-44) for general statement on ethnographic and 'racial type' photography; Newbury (2009:15-70) for an overview of pre-1950s images of 'native life'; Stevenson and Graham-Stewart (2001:23), Hight and Sampson (2002:4) and Garb (2013: 32-34) on the uses of European pictorial conventions.

5 I have extensively consulted Dick (2005), Dick (2009), Gordimer (1988:49-56, 209-217) and McDonald (2009), but see also Kunene (1981) and Lyster (2018).

6 Brink submitted slides from his book to Penthouse magazine in the hope of securing a large payday. His South African publishers, Buren, also unsuccessfully solicited international publishers at the Frankfurt Book Fair (De Kock 2019).

7 See Brink (1998:207-230).

8 . Photo book! Photo-book! Photobook!, A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town, February 11 - May 21, 2022: This browsable exhibition was a continuation of a primary research project initiated in 2020 and displayed a large archive of photobooks in chronological order from 1945 and 2022. The focus was geographic, South Africa, but not nationalistic: books published internationally were presented alongside books produced in South Africa; citizenship was not a criterion for participation.

9 Case number 29850/8, 9 October 1963: a postal official instigated the review Five Girls after a postal intercept of a single import of the book by a private individual.

10 Baldwin (1980:441) writes: 'It is terror that informs the American political and social scene - the terror of leaving the house of bondage. It isn't a terror of seeing black people leave the house of bondage, for white people think that they know that this cannot really happen ... No, white people had a much better time in the house of bondage than we did, and God bless their souls, they're going to miss it - all that adulation, adoration, ease, with nothing to do but fornicate, kill Indians, breed slaves and make money'.

11 For a discussion on the difference between 'photojournalism' and 'documentary' photography in South Africa, see Wyman (2012:10-12). Newbury (2013:231) writes that 'South African photography has commonly been interpreted within a paradigm of truth and lies, revelation and concealment'; this process is evident in the widespread use of the words 'witness' and 'expose' in relation to Cole's photography in popular journalism and museum overviews, without fixed or clear definition.

12 This newspaper had months earlier touted House of Bondage as 'an explosive picture-and-text book' in an advance preview (Los Angeles Times, 30 April 1967).

13 The report (P90/03/59) refers to the 1968 Penguin edition published in London.

14 The original reads: 'Vanaf die inleiding deur al die beskrywings, en die foto's met kommetaar daarby, loop daar 'n draad van skerp kritiek met soms ook sarkastiese en neerhalende opmerkings oor apartheid en die blankes in Suid-Afrika.'

15 The original reads: 'Tot 'n hoë mate is verskeie van die voorstellings (foto's wat apartheid uitbeeld) of stellings oor diskriminerende wette, gebaseer op toestande wat verander het en 'n bedeling wat nie meer bestaan nie, of besig is om te verander.'

16 Interview with Omar Badsha, Cape Town, 5 February 2021.

17 It also travelled to the Midlands Art Centre in Birmingham in 1995, and a year later to the Centre for African Studies at the University of Cape Town.

18 Interview with Henrietta Dax, owner Clarke's Bookstore, Cape Town, 7 October 2020.

19 In 1978 a replica of the original portfolio, which was limited to 20 editions, was produced by the International University Exchange Fund and distributed by the UN Special Commission on Apartheid. This mass-produced portfolio was banned from importation into South Africa (Jantjes 2018).

References

Attwell, D. 2015. J.M. Coetzee and the Life of Writing: Face-to-Face with Time. New York: Viking. [ Links ]

Badsha, O. 1986. South Africa: The Cordoned Heart. Cape Town: The Gallery Press. [ Links ]

Baldwin, J. 1980. Notes on the House of Bondage. The Nation 231, 1 November: 440-441. [ Links ]

Bank, A. 2001. Anthropology and Portrait Photography: Gustav Fritsch's 'Natives of South Africa', 1863-1872. Kronos 27(1):43-75. [ Links ]

Brink, A. 1998. The Novel: Language and Narrative from Cervantes to Calvino. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press. [ Links ]

Campany, D. 2014. What's In a Name? The PhotoBook Review 7. [ Links ]

Coetzee, JM. 1991. The Mind of Apartheid: Geoffrey Cronjé (1907-). Social Dynamics 17(1):1-35 [ Links ]

Cole. E. 1967. House of Bondage. New York: Random House. [ Links ]

Cole, E. 1968. My Country, My Hell! Ebony, February:68-73. [ Links ]

De Kock, L. 2019. The Love Song of André Brink. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers. [ Links ]

Dick, AL. 2005. Book Burning: How South African Librarians Conspired, 1955-1971. Cape Librarian May/June: 10-14. [ Links ]

Duke, B. 1988. Was Chairman Mao a Gay Freethinker. The Freethinker January 108(1). [ Links ]

Du Toit, JB. 1990. House of Bondage: Reader's report for Publications Control Board, reference number P90/03/59 10 April:1-2. [ Links ]

Enwezor, O & Zaya, O. 1996. Colonial Imaginary, Tropes of Disruption: History, Culture, and Representation in the Works of African Photographers, in In/sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present, edited by C Bell, O Enwezor, D Tilkin & O Zaya. New York: Guggenheim:17-47. [ Links ]

Gordimer, N. 1988. The Essential Gesture: Writing, Politics and Places. Johannesburg/Cape Town: Taurus/David Philip. [ Links ]

Gordimer, N. 1999. A Morning in the Library: 1975, in Living in Hope and History. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [ Links ]

Hight, EM & Sampson, GD (eds). 2002. Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)ing Race and Place. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jacobson, D. 1968. Inhuman Bondage. The Guardian 28 March. [ Links ]

Jantjes, G. 2018. Catalogue Note to A South African Colouring Book. Sotheby's. [Online] Available from: https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2018/modern-contemporary-african-art-l18802/lot.79.html Accessed 4 November 2023. [ Links ]

Knape, G. 2010. Notes on the Life of Ernest Cole (1940-1990). Ernest Cole. Göteborg: Hasselblad Foundation. [ Links ]

Kunene, D. 1981. Ideas Under Arrest: Censorship in South Africa. Research in African Literatures 12(4), reprinted Ufahamu, Fall 38(1):219-238. [ Links ]

Kunene, D. 1967. Trapped in Someone Else's Dream, New York Times, 8 October. [ Links ]

Lelyveld, J. 1985. Move Your Shadow: South Africa, Black and White. New York: Times Books. [ Links ]

Lyster, RF. 2018. A History of Apartheid Censorship through the Archive, PhD thesis, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Matshikiza, J. 2001. History in the making. Mail & Guardian 30 November - 6 December. [ Links ]

McDonald, PD. 2009. The Literature Police: Apartheid Censorship and its Cultural Consequences. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Minkley, G & Rassool, C. 2005. Photography with a difference: Leon Levson's camera studies and photographic exhibitions of native life in South Africa, 1947-50. Kronos 31(1):184-213. [ Links ]

Newbury, D. 2009. Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa. Pretoria: Unisa Press. [ Links ]

Newbury, D. 2013. Sizwe Bansi and the Strong Room of Dreams. The Rise and Fall of Apartheid. New York: International Center of Photography. [ Links ]

Nkosi, L. 1966. Encounter with Brazil. The New African November:183-185. [ Links ]

Parr, M & Badger, G. 2004. The Photobook: A History volume I. London: Phaidon. [ Links ]

Parr, M & Badger, G. 2006. The Photobook: A History volume II. London: Phaidon. [ Links ]

Powell, I. 2010. A Slight Small Youngster with an Enormous Rosary: Ernest Cole's Documentation of Apartheid. Ernest Cole. Göteborg: Hasselblad Foundation. [ Links ]

Rushdie, S. 1988. The Satanic Verses. London: Vintage Books. [ Links ]

Sekula, A. 1986. The Body and the Archive. October, Winter 39:3-64. [ Links ]

Sobekwa, L. 2021. Images Burnt into My Mind. Tate Etc. 51 Spring:62-69. [ Links ]

Stein, S. 2011. South Africa's Apartheid-era Photography. Aperture, Fall:74-76. [ Links ]

Thomas, LM. 2012. Skin Lighteners, Black Consumers and Jewish Entrepreneurs in South Africa. History Workshop Journal Spring 73:259-283. [ Links ]

Young, A. K. 2018. Visualizing Apartheid Abroad: Gavin Jantjes's Screenprints of the 1970s. Art Journal Fall-Winter 76(3/4):10-31. [ Links ]