Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a26

ARTICLES

Flowers, sex, labour and loss: Transcript of the keynote conversation between Willem Boshoff and Olu Oguibe at the Art, Access and Agency - Art Sites of Enabling Conference

Johan ThomI; Willem BoshoffII; Olu OguibeIII

ISchool of the Arts, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. johan.thom@up.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8488-5031)

IIArtist, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. boshoff.willem@gmail.com (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8292-2353)

IIIArtist, United States of America

Transcript of the keynote conversation between Willem Boshoff and Olu Oguibe at the Art, Access and Agency - Art Sites of Enabling Conference hosted by the University of Pretoria's School of the Arts and the University of Pretoria's Transformation Directorate from 7-9 October 2021. The conversation is introduced and moderated by Johan Thom.

Transcribed by Natasha Kudita

List of Acronyms:

JT= Johan Thom

WB= Willem Boshoff

OO= Olu Oguibe

JT: The artworks Garden of Words (1981 - present) by Willem Boshoff and Sex Work is Honest Work (2021) by Olu Oguibe form the basis of this discussion regarding social advocacy in contemporary art and the many material and conceptual forms it may take. Interestingly, both series of works somehow take the garden as a starting point. From here the artists proceed to map out divergent artistic terrains of social engagement and contemporary art practice.

The Garden of Words series is a mammoth, long-term undertaking underpinned by the sheer force of Willem Boshoff's artistic labours and his ongoing interest in the power and forms of language. Throughout this series Boshoff delves into the archives of language, creation myths, plant life (and its rapid extinction), memory, and graveyards. For example, since 1981 Boshoff has identified over fifteen thousand plant species in different locations all over the world, collecting their names and memorialising them in - and as part of - a series of enigmatic sculptural forms and installations. Now in its fourth incarnation, the Garden of Words series is an ongoing act of 'seeding', a promise of germination at the heart of human existence on earth - this despite our seeming all-consuming penchant for destruction and self-aggrandisement.

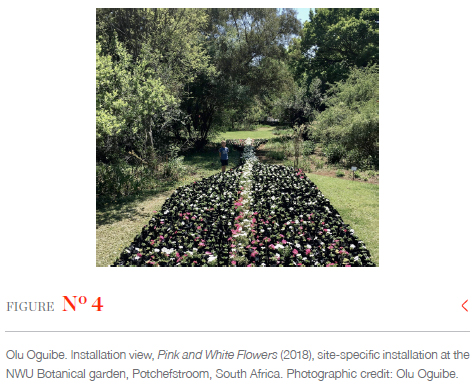

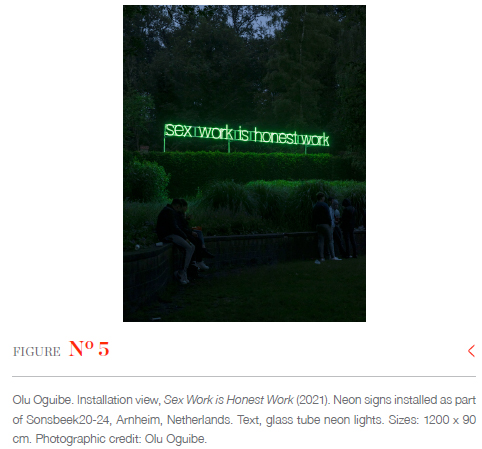

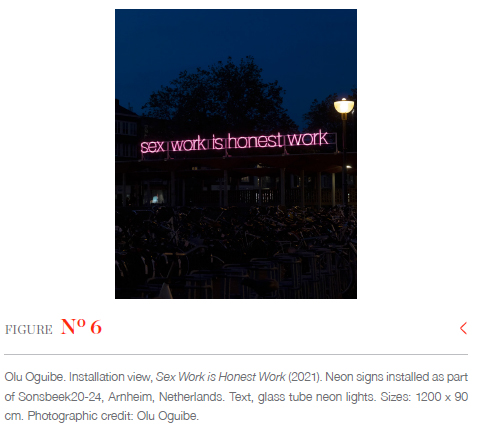

In 2018 Olu Oguibe installed the artwork, Pink and White Flowers, in the botanical garden in Potchefstroom - a transient monument-of-sorts consisting of approximately three-and-a-half thousand live flowering plants that visitors were invited to take home and care for. The work commemorated the life of a young woman named Nokuphila Kumalo. Kumalo was a sex worker who tragically died in Cape Town in 2013, allegedly at the hands of South African artist Zwelethu Mthethwa. From here, we see how Oguibe's lifelong interests in labour and social justice converge and transform into an ongoing multifaceted art project titled Sex Work is Honest Work. This project confronts the near-global bias against the salient recognition of sex work as honest work by way of several discrete but interrelated manifestations including: A public installation in Arnhem, Netherlands, as part of Sonsbeek20-24 International Art Festival; a two-day conference jointly organised between Sonsbeek Art Festival, The Dutch Art Institute, and Oguibe in August of that year; a standalone neon sculpture for the contemporary art gallery space, and, most recently, a multi-panel text-based work on paper and resin sculpture. Each of these manifestations remains true to the central message of the work, but they embody it in very different ways.

Art is, of course, always simultaneously useless and deeply meaningful, allowing us to reflect on our failures and successes as more than mere cold instruments of purpose and reason. In other words, central to contemporary artistic practice is the recognition of viewers as being thinking, feeling, humans and individuals. Accordingly, we may be transformed if we deeply engage the uncertain space at the heart of contemporary art's complex, even beautiful workings as a form of social practice, labour, and ultimately, of love.

Willem and Olu, would you each be kind enough to introduce the series of artworks under discussion to the audience by briefly referring to the process of their making, their different formal manifestations and conceptual underpinnings, for example?

WB: In 1977 I already wrote my first dictionary. I felt it was necessary for me to make more than just superficial sense of the etymology, of the beauty and the mystery of words by simply writing ordinary dictionaries and so on. I turned these dictionaries into artworks. Since then I have written (or 'made') more than fifteen dictionaries, including the Garden of Words.

Today there are thirty thousand plants on the international red data list, which means they are critically endangered. After your talk, I thought curiously that plants have a 'red list district' - with apology to Olu Oguibe's reference to 'sex work', which can take place in a red light district. I decided to find out for myself, how one would feel if these plants were to become extinct. I started studying them closely, learning their names and making careful notes of each plant I encountered in botanical gardens around the world. When I had studied five thousand plants and recorded each species by name, I decided to make a memorial garden for them - something to remember them by, should they disappear forever.

I wanted to produce a kind of conceptual garden, one in which there are no plants, only names. When one visits a memorial garden for soldiers that had fought and died, there are no real graves, only token or substitute graves. Actually, no one might even know where these soldiers are or what really happened to them. They are all gone. When plants become extinct, we will have nothing left of them except their names.

If you know somebody well and they die, then you really experience a sense of loss and sadness. Similarly, I have come to know these plants personally! So in Garden of Words I you see the plant names 'packaged' as if they are contained in the pages of a book. The artwork became a large kind of book, chapter after chapter laid out on the ground. The layout is that of a hot-house with seeds identified, but not planted. They cannot be planted for they are forever gone.

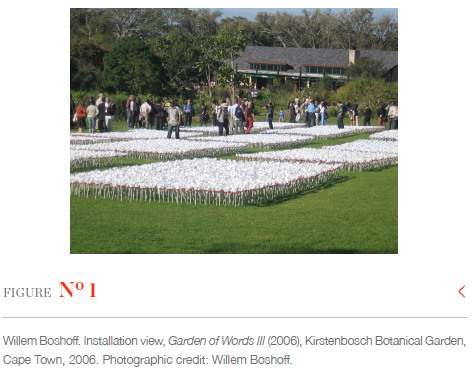

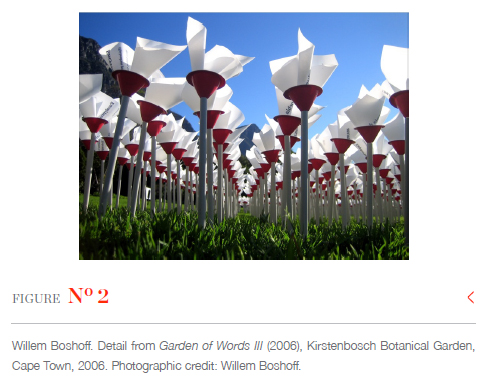

Garden of Words II, is a similar work. By then I had attempted to study ten thousand plants. Here the plant names are once more presented as flower beds that resemble doors. Flexible plant labels are inserted in holes. Their flimsy, transparent names move in the wind. The 'plants' seem to have a kind of ethereal, near spiritual life because when they move, they look like real plants that have leaves similar to blades of grass (Figure 1). The image is from Gallery Silkeborg to the north of Denmark. When the huge forest just outside the gallery window moves in the wind, so too will the 'grassy fields' of the artwork.

After I had studied fifteen thousand plants, I created Garden of Words III. Here the plant names appear like red poppy flowers. Of course, there are numerous memorial gardens for fallen soldiers, featuring poppies in Europe. 'Poppy day' is when members of the public put poppies on their jackets to commemorate the fallen. For Garden of Words III I have fifteen thousand poppies holding handkerchiefs with the name of a flower and a brief history on each. The handkerchiefs also move in the wind and more importantly, they come to our aid when we cry.

I am now working on the last Garden of Words (Garden of Words IV). It will contain all thirty thousand plant names. I've built a structure with a roof in my yard and am furiously compiling more plant names!

OO: The background to the work that I will discuss should be familiar to many people in South Africa. On the early morning of April 13, 2013, a young woman named Nokuphila Kumalo was kicked and stomped to death on a street pavement in Cape Town by a man who was later identified as a world-renowned South African artist. Miss Kumalo was only 23 years old. She also happened to be a sex worker and her murderer is believed to have been a client. Her mother had no surviving photographs of her; in fact, the image that was used for Nokuphila in the media is a painting made from a police file photograph of her body in the morgue.

The one thing, though, that the mother did remember and remark on to the press among other things, was that her daughter loved pink and white flowers. I thought this was quite notable, and in 2018, Johan and the Nirox Foundation invited me to do a residency in South Africa. The residency part of the work that I did was to produce an installation to commemorate the short life of Miss Kumalo. This installation named Pink and White Flowers was eventually shown in the botanical garden at the University of the North West in Potchefstroom as part of Aardklop, a National Festival of the Arts, 2018.

With this installation, this public memorial-of-sorts, and using those motifs of the pink and white flowers, I wanted to also bring up a number of pertinent subjects including sex work, as well as sexual and gender-related violence.

For the installation we placed several thousand flowering plants in the botanical garden to be taken home by viewers. Viewers could nurse and raise them and thus, take a part of the memorial with them. For me it was an important way of extending the project and its central concerns from the public to the private space, and of introducing a different form of public art to people (especially with something perishable like plants).

In 2019, I was invited to participate in Sonsbeek which is the international sculpture festival in Arnhem, Netherlands. I proposed to the organisers that I would like to make a much larger version of Pink and White Flowers, this time with pink and white tulips, tulips being more or less the national flower of the Netherlands. I wanted to cultivate a large field of pink and white tulips as a springboard to look more deeply at issues surrounding sex work. With Sonsbeek this could be a more expanded project, extended over the period of several months, with thousands of visitors coming to see the installation.

Globally, sex workers face an ongoing struggle against the powerful confluence of morality, legality and capital around sex work. For example, there's the historical denial of sex work as labour, and also the long-held patriarchal idea of women in sex work as recreational facilities or so-called 'comfort women' for workers, rather than workers themselves.

I thought there might be a productive conversation around the more commonplace view of sex workers as comfort for migrant labourers or soldiers, and the growing interest in the complexities of sex work as migrant or indentured labour in itself. Think, also, of the conflict between sex work, gentrification, and notions of urban renewal, where sex workers are either pushed to a particular district where they are more easily policed or they are sort of 'disinfected' from the main bloodstream of the city or pushed to the edge. When gentrification arrives in any neighborhood, that neighborhood is 'cleansed' or 'sanitised' of sex work, which is then sequestered and quarantined on the outskirts.

Of course, there's also a lot of current debate around sex work and human trafficking. You may notice that the debate has a certain political utility in that human trafficking is used as an excuse to further police sex workers or erode and undermine their civil liberties. The argument usually made by politicians especially on the right against legitimising sex work is that they are trying to fight human trafficking, or that they are trying to protect juveniles from being recruited into sex work, or protecting Africans and other vulnerable immigrants from being trafficked as sex slaves. So, they use this very real problem as an excuse to then expand policing willing and professional sex workers performing legitimate labour. With the project I also wanted to highlight again the prevalence of violence towards sex workers, and include the often unspoken subject of male and queer sex work.

As it turned out, before we could start the project, the COVID-19 pandemic arrived. Also, I was informed just shortly before I thought we'd be able to set out to start planting the tulips, that due to climate change, experts had advised that it would be very difficult to predict how the plants might turn out or whether or not they would be ready for the period of the festival. Usually, Sonsbeek happens in the summer and tulips usually bloom in the spring. With these challenges and variables in mind, we ended up shelving the tulip field idea and, instead, made two text-based neon public sculptures with the words, 'Sex work is honest work'.

For the town center we used pink neon in the sculpture. For the second sculpture which was installed in the city park, we used green neon which has the least adverse effect on the especially nocturnal wildlife in the park. I wanted to make three of these sculptures and place them in different parts of the city rather than in the park because, at the end of the day, although some sex work does happen in public parks, as does sex itself, sex work is pretty much an urban trade. Eventually, though, we were only able to produce two sculptures.

As a way to further extend the project, I also proposed that we organise a conference or discussion forum on the subject of sex work. In late August 2021, we held a two-day global conference where scholars, people from the sex work and intimate labour industries, advocates, and the general public were able to participate live, and those who couldn't due to the pandemic took part remotely. As noted earlier, the project is ongoing.

Finally we also made a smaller version of the neon sculpture for indoor gallery display. This particular version of it was shown at the Milan Art Fair just a short while ago. The whole idea was to not limit the work to the space in Arnhem, but rather continue to propagate, if you like, this conversation in as many different spaces as possible.

JT: In contemporary art the flower is a well known symbol of love, eroticism and loss. Within both these decidedly conceptual series of artworks the power and vitality of the flower as symbol and its possible meanings is reaffirmed and extended in different ways.

Willem, on the most obvious level Garden of Words III refers as I ask the following question (but I do suspect it holds true in different ways for much of your work): What happens or becomes possible when we think of words as flowers and vice versa?

WB: For me, nothing can surpass the marvellous experience I have with live flowers, plants and life we experience in the grand garden we call nature. I can't help but wanting to learn and understand more. Words help. We share our experiences with each other, and the better we can express these in language, whether in text as casual conversation, on in carefully delivered treatises, prose, poetry or art, the more clearly we might be able to bring a point home. My Gardens of Words are for me, in the first place, gardens of my mind. I know that thousands of plants will go extinct, perhaps within our lifetime. I rejoice in being able to memorise the names of so many, holding on to the experience desperately. But then, I get equally perturbed when these slip from my memory - to become extinct from the garden of my consciousness. What happens to our words when we die? It seems as if we take them with us into oblivion.

JT: Olu, Sex Work is Honest Work develops by way of Pink and White Flowers (2018), a memorial for Nokhupila Khumalo. This memorial is tacitly embodied and performatively enacted by way of the gift of flowers to the viewer. What remains of the flower as we see these ideas develop into Sex Work is Honest Work? How do we see the ideas behind its initial employ and function metamorphose, shift in focus, and transform into a larger project?

OO: I began working with flowers a long time ago, making memorials, because the connection that I made between grief and flowers is the element of beauty and how it's often deployed to assuage or counteract trauma. In other words, when we experience grief or almost unspeakable trauma, people are somehow driven to seek relief through some form of aesthetic intervention or beauty. Which is why, if there is a fatal accident on a roadside, for instance, people leave flowers at the site. We saw what happened when Diana the princess died, how people would leave bouquets of flowers and so on as a way to deal with their grief. Flowers are beautiful, and I think that offering something beautiful as a farewell or in response to a sad and traumatic event is very natural. It's like singing, which we also do when someone is going through grief; people sing to more or less soothe their spirit and help bring succour. So, flowers are employed in that sense in the work that we did at the university botanical garden, first because this young woman liked a particular kind of flower, and this is what her mother remembers in the absence of any photographic image of her. In effect, those flowers become like a representation or surrogate embodiment of her even more than the painting that was done to represent her in the media. Her mother did not respond to the painting; instead, she spoke about how the daughter liked pink and white flowers.

One way it extends to sex work and the neon sculptures is that sex work is very much related to flowers. In mythology, for instance, Flora, the ancient Roman goddess of flowers, was also the protector of sex workers. Many Renaissance writers believed that Flora was, in fact, originally a sex worker in ancient Rome who was eventually deified and apotheosised as a goddess. Floralia was the Roman flower festival held annually in Flora's honour, and it's very much reminiscent of the flower festivals that are still held in different parts of the Netherlands and other parts of the world today. Just as interestingly, the floral wreaths that were worn in ancient Rome during the festival in honour of Flora are precursors to the wreaths that are worn today during the labour celebrations on May Day. So, there are longstanding, even ancient, connections between flowers, sex work and labour.

One other reason I thought about tulips when translating the project is that the tulip itself as a plant is a migrant from central Asia to Europe via the Muslim courts of Turkey. Introduced directly from there, the Dutch in particular came to regard it as the most beautiful, most highly valued cultivar of plants, and it still contributes immensely to the Dutch economy to this day. Mind you, this is an immigrant plant from a Muslim culture. Just think about the fraught relationship at present between Europe and its migrant Muslim communities.

In the early seventeenth century, the Dutch built a speculative commodities and futures market around tulips. At its height, a mere bulb could fetch the equivalent of a princely manor and estate. When the tulip futures trade collapsed in 1637, it literally wiped out the Dutch economy, and so many speculators took their own lives as many were financially ruined. Interestingly enough, in the media of the period, Dutch cartoonists depicted Flora, the goddess of flowers, as a sex worker paraded through the streets while people threw rotten fruits at her. In other words, they cursed and castigated the goddess of flowers just like a prostitute. Traders who participated in the market speculation were described as 'prostituting' themselves.

So, in my research, these connections between flowers, sex work, and even capitalist speculation kept coming back. It was easy to go from the commemorative flowers piece for Ms Kumalo to the Arnhem sculptures about sex work as honest labour.

JT: This thought brings me quite naturally to my next question which has to do with labour. Willem, obviously The Garden of Words is underpinned by the seemingly impossible labour of memorising and visiting all of these near extinct plants in different parts of the world. But regardless of our human attempts to remember each of them, we are also doomed to forget (whether through neglect, the destruction of our archives or the simple fact that we cannot remember everything - there simply is too much information). Willem, I wonder if I can ask you to please comment further on this aspect of The Garden of Words series?

WB: The most important thing for me to remember when I'm doing this, is that it happens in my head. Memory is a very important aspect of this project and my work as a whole. Somehow the flower, its name and whatever information one can gather about it, has to find a home in my mind. In a very real sense I am a conceptual gardener whose garden exists in my head! I also think that if I spend so much time on something it becomes a love affair. These things have enamoured themselves to you and perhaps even the other way around too. So it is with The Gardens of Words. Regardless, I constantly have to remember and refresh the memory of each plant, otherwise they die and become extinct, forgotten.

Forgetfulness or forgetting is a form of extinction whether through disease such as Alzheimer's or just old age. It is a natural form of extinction within yourself, of myself to myself. Living plants do not go as easily extinct in the manner that they become extinct inside my head. Accordingly I have kept tons of notes about each plant and I refer back to them often.

In memorial gardens, for example, there are often simple descriptive labels containing names and dates. These labels may lie on the floor, sown like seeds. But of course there is nothing more there, only labels - and so it is in some way really futile. One cannot bring real things that have died back to life - whether it is fallen soldiers or extinct plants. My labels speak to the wind, like blades of grass. They just gently move and nothing else happens. Once something is extinct it is truly lost forever.

In the history of evolution, in the history of the world, it is calculated that of all the things that have ever lived - animals, plants, all living forms - nearly 99 percent are now extinct. I think we are currently truly at the end of something. That is the philosophical reality of this whole project.

JT: Agreed. That said, Willem I do think that these things are deeply meaningful to you, to the people who see your work or even those who visit other memorials. While we are here, exist one earth, life has to have meaning. We must remember things that matter to us, or at the very least try to do so - regardless of what obstacles we may encounter along the way. This for me is the beauty of The Garden of Words and much of what we term 'art'.

I also think about the question of artistic conviction and of honesty. To be honest with ourselves about our central role in the mass extinction of life that is currently underway, for example. And, along with this, to have the conviction to actually do something about it. Such self-reflexive honesty and conviction stands central to fostering healthier, more meaningful relationships with our world and our surroundings, plant, human, animal - indeed everything that co-habits this world with us. On this very topic, I think Olu's choice of title for his project is truly ingenious inasmuch as he couples the question of honesty with sex work. This obviously grates many people for all the wrong reasons.

Olu, why is sex work honest work?

OO: Thank you. That is a very important question. I do have to admit that there is a specific cultural context to the use of the term, 'honest work' in my title. In America the term is used a great deal by a certain class of workers to describe work that involves exertion, that is, manual work, as opposed to white collar work. As you may be aware, in America the working class often regards as lazy, people in other walks of life which involve manually less exerting work. The band Dire Straits did a famous song about that sentiment called Money for Nothing. So, the term is something of an Americanism. In a way, it also reminds me of something I have recently discussed publicly in relation to my father who passed away over the summer. When I was a kid, my father had a sign in his studio that said: 'There is dignity in labour'. That was his motto.

Sex work and intimate labour are exchanges of time and skill for pay. Many people forget that there is skill involved in sex work, and bodily exertion, also. In this sense, it is honest labour. Unlike public officials and white collar workers, sex workers are not busy accepting bribes or embezzling public funds. They do not cheat people at the gas pump or the grocery till. They work for their pay. In exchange for money, they make an effort and take serious risks to offer something valuable to people. Accordingly, they deserve to be treated with dignity rather than the usual hypocritical, patronising contempt. As societies, we are the clients of sex work and intimate labour even as we criminalise people who provide that service and treat them with contempt.

What the title of the work does is provoke people to ask more complex questions about something they may take for granted. You know, when they read the text, it makes them pause and go 'Huh? Really?' Whether or not they agree, it is part of the conversation that I want to generate with the work.

JT: The question of agency in relation to artistic practice is a very difficult but useful way of addressing what an artwork 'does' and where one thinks it belongs in relation to society. Willem, how do you define agency in relation to your practice? For example, how does your work fit into the art world, who do you make the work for, what do you think the function is of art and so on?

WB: Well, it certainly is a dilemma to make works of art that you often have no hope of selling! That said, it makes art a very personal experience for me, one in which I become deeply involved with the work and the various components that go into its making, such as individual plants.

In my art I often find that I have to figure out how to present something that I have lived to the audience. My lived experience becomes an integral part of the artwork as it were. But how does one do this? Botanical gardens, for example, are wonderful spaces. They have labels underneath every plant one encounters and one will be able to write down what the name is. You can take photographs of the specimens to later refresh your memory too. But when you go out into the forest or the wild there are no labels, and you must do your own research. You may often not know what kind of plants you have found and then you must familiarise yourself with them over time until you can find their names. This can take very long but I found that through the process these plants become something like friends to you.

Of course, no one has asked me to do this! I have decided to do so because I find myself immersed in this experience.

The first Garden of Words is older than forty years now. The last one is now going to be made and then I will stop. But today I feel good about the experience of making the work. I feel fantastic when I now walk down the street in London or in an American city and immediately recognise the plants I encounter along the way. Like I said, they have become my friends and I am genuinely happy to see them. When I see an oak tree I wonder to myself why this one might look like another? Then I think, I'd better go and check my books and I see. My goodness, there are four, five, six and seven that look like this and there are around six hundred species of oak trees! It is an unbelievable journey and experience for me.

At the beginning of The Garden of Words I thought that I would memorise every plant that forms part of the series. But it is impossible! There are more than four hundred thousand plant species and I battle to document only the thirty thousand of my work.

Why am I doing this? I just feel that I should. I think I am filled with awe and a sense of purpose - things you really cannot make money out of. So, I want to share this feeling, this experience with others through my work. I think much of life is like that, you make breakfast for the family and nobody is going to pay you for it, you have to feed and clothe your children and nobody is going to pay you for that. It's a thing that you do and it rewards you with joy and a feeling of belonging.

JT: I think that question of pleasure and beauty animates much of our work as artists, whether we acknowledge it or not. There is real beauty for me in the way in which your numerous encounters with plants are translated into art objects. These artworks become repositories of felt experiences and lived knowledge too. This is not simply a visual aesthetic, it's an aesthetic that moves well beyond the straightforward question of whether the work is visually appealing. I think that in order for the work to become 'beautiful', viewers have to actively engage it, spend time with the artwork and think about it very carefully. Only then do they understand its relative beauty.

With Olu's Pink and White Flowers, visitors to the site could take a flowering plant home. But this means they had a real responsibility to take care of them, too. The artwork for me existed in that moment of caring. Olu, in relation to your artistic practice now, how do you think about such questions of agency?

OO: As I often say, the purpose of all revolution is beauty. Throughout my career, my work has been preoccupied with advocacy, social justice, trauma both personal and social, and commemoration as what one might call a technology of healing. I started out in advocacy and activism as a young teenage student leader and then, an active participant in the continental pro-democracy movement. Afterwards, I focussed more closely on cultural activism through writing, curating, scholarship and theory. To this end, I was trained at the Nsukka School which was very much centred around people who had just come out of the Biafra War. For us, caring was very important, survival was very important, trauma was a very fresh experience, and, reflecting on what's happening around one was very important. Every one of the artists reflected or embodied that care in their work. So, you could say that there is a historical context to the same preoccupations in my work.

To return to my earlier statement, the purpose of all activism, revolution, and social justice advocacy is so that as many people as possible are in a position to have a pleasant life on planet Earth. We all need the protection, space, and room to enjoy all that is beautiful in our experience of life on earth. So, beauty is very important and directly relates to the effectiveness of the work that I make. I may say to myself "I've made public artwork about refugees, but how does that actually impact the day to day life of a refugee? How does it make a difference in the world or in their life?' When caught in that kind of self-doubt, I have to remember what the purpose of my work is.

Willem's work is very personal, and yet, someone might leave a space where they've encountered Willem's work and pay more attention to extinction because they've been impacted by the work. They might go home and say 'Oh my God! How am I contributing to this? What can I do about it?' To Willem that might be mere icing on the cake, but it's still the case that his work has a major impact on people. Similarly, people might see my work about flight and refugees, or the projects on sex work, and be deeply moved by it. That way they might end up caring about the issue and making a difference.

I also feel that art can have a different kind of material impact on people's lives. There are many examples. I think of Picasso, for instance, and how many people do not know that he was both a communist and a vigorous peace activist. He was a card-carrying member of the communist party for the last thirty to forty years of his life, and he designed posters and made iconic images that were used in the global peace movement. He gave his money, time and skill to advocate social justice in addition to making art. Someone like Banksy is also able to generate wealth which he then puts into people's daily lives by building infrastructures like housing, and spaces that provide social services. Many other artists do this, also, that is, using the proceeds from their art to support charitable work in different spheres.

There's a lot of focus now on social justice in the arts and it can only be for the better. In the past it was something that only a few artists made central to their practice. This often led the general public to forget or fail to recognise that no social movement succeeds without the active involvement of artists. Artists make the posters, we do the murals, we provide the visual and aesthetic means through which social movements communicate. So, artists have always been socially involved in some way without necessarily being at the forefront or making claims for it.

JT: I just want to make a final comment. As a younger artist I clearly remember looking at the works of both of you and how they impacted my life. Olu, I first encountered the essays that formed a part of the The Culture Game (2004) during my master's studies. I spoke to a friend of mine (the photographer Abrie Fourie) about these writings and then he told me that you are an established artist too. So I went and looked at all your work and suddenly developed a more in-depth understanding of your entire project as being one with many dimensions (including art, art criticism, curation, academic scholarship, poetry and social engagement). With Willem, I knew about his work from childhood through my mother's studies in fine art. I think I first saw his works in 1981 already! The point is this, the encounter with the artworks of you both changed my life. Now whether it is through the encounter with individual artworks, writing, the expanded ways of artistic engagement that Olu was talking about earlier, this alone should tell us that we ought never underestimate the power of art. We as artists tend to forget such intimate, individual impact because yes, I think we do typically crave huge outcomes too. Today I know firsthand how many individuals (students, artists and members of the public) have been deeply touched by both your respective artistic practices and the broader social concerns that underpin them. In fact, exactly because of your concerted efforts I would argue that such social engagement as is readily apparent in your respective artistic practices have now become a key component in contemporary artistic practice in South Africa, Africa and even globally.

Willem and Olu, it has been an absolute privilege to have spoken to you both as part of this keynote conversation. From Pretoria, South Africa, thank you and goodnight to everyone in attendance.