Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a25

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Cleansing shame: Airing South Africa's 'Dirty Laundry'

Dineke Orton

PhD candidate with the SARChI Chair in South African Art and Visual Culture, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. dineke@vanderwalt.za.net

ABSTRACT

The experience of rape is intensely shaming, particularly because of the humiliation that stems from being violated by another person and the loss of control endured because of it. Survivors often feel stained or contaminated in the aftermath of rape and fear the disclosure of this seemingly 'negative information' about themselves. In this study, I examine the exhibition, SA's Dirty Laundry (2016), by Jenny Nijenhuis and Nondimiso Msimanga that was installed in the streets of Johannesburg's Maboneng precinct. Used panties donated by rape survivors were installed on a washing line to act as placeholders for individual self-narratives. In this way, the presence of survivors was staged without explicitly referring to them. By unpacking associations linked to panties, I illustrate how these small pieces of clothing could reference the shaming survivors often face. So-called 'dirty laundry' is referenced as a conceptual tactic through the curatorial display mechanisms: panties are displayed on a washing line-a common domestic device used when cleaning. Apart from this interplay, I emphasise the value of collaboration in this project and the advantages of braving vulnerability.

Keywords: Artivism, exhibition, rape, SA's Dirty Laundry, sexual violence, shame.

Introduction

The notion of a home often conjures associations of family and a sense of safety. It is, however, also a space that sometimes witnesses considerable violence. Indeed, domestic violence and, specifically, domestic rape are widespread in South Africa.

Many survivors express feeling 'dirty' and experiencing acute shame after being violated (Gilbert 1998:11). Shame is often characterised by 'devastating and paralysing feelings of self-condemnation, disgust, anger, and inferiority' with a pronounced desire to withdraw and disappear (Keltner & Harker 1998:78). Feeling and fearing being shamed and stigmatised lead many survivors to engage in practices of hiding their perceived 'damaged self' or 'spoiled identity'-as ways of escaping observation and judgement (Engel 2015:83; Gilbert 1998:22; Stearns 2017:4). Apart from feeling ashamed, survivors of sexual violence often feel pressured into silence about their traumatic experiences, fearing scrutiny and not being believed.

However, besides feeling pressured to remain silent, this form of violence is extremely difficult to narrate due to the nature of rape, which is a sexually specific assault in which one individual silences and asserts their will over another, appropriating the other's body and autonomy. Subsequently, individuals who might seek to disclose what happened are often severely damaged and shattered by the violence inflicted upon them, which frequently constrains their agency as narrators of their own stories. This begs the question of how it might be possible to speak about the unspeakable in a manner that could permit survivors to be heard and believed.

With such after-effects and traumatic outcomes in mind, I explore the exhibition, SA's Dirty Laundry (2016), which made use of items that are reminiscent of the domestic space to draw attention to the reverberations of rape. Through their use of a familiar household item, the washing line, that calls to mind domestic cleaning practices, the curators brought attention to and reflected on the consequences that such breaches in domestic safety have on survivors. Thus, in this article, I aim to explore the correlation between notions of shame experienced by survivors and metaphors of cleansing as a curatorial strategy.

Important sources on this exhibition include a scholarly article written by the organisers, Jenny Nijenhuis and Nondimiso Msimanga, entitled 'SA's Dirty Laundry and The things we do for love: Love and artivism as process-protest' (2017), as well as numerous online reviews by amongst others Floyd Matlala (2016), Claire Landsbaum (2016), Peter Lykke Lind (2016), Marisa Crous (2016), Dieketseng Maleke (2016), and Ufrieda Ho (2016). Existing scholarship tends to focus on discussing the issues around rape itself within the South African context, rather than addressing the curatorial techniques employed in order to provide a platform to visually interrogate rape narratives. Other than Winnie Li's (2018) study on art activism and sexual assault, which outlines the complexities around an art festival on the subject, and Nijenhuis and Msimanga's own paper, which centres on their approach to love and intimate activism, little of substance has been published on the role of curatorial practices in exhibitions related to sexual violence.1 This paper intends to address this gap by relying primarily on an interview I conducted with Nijenhuis, one of the project's curators.

Panties, panties, panties: Airing dirty laundry

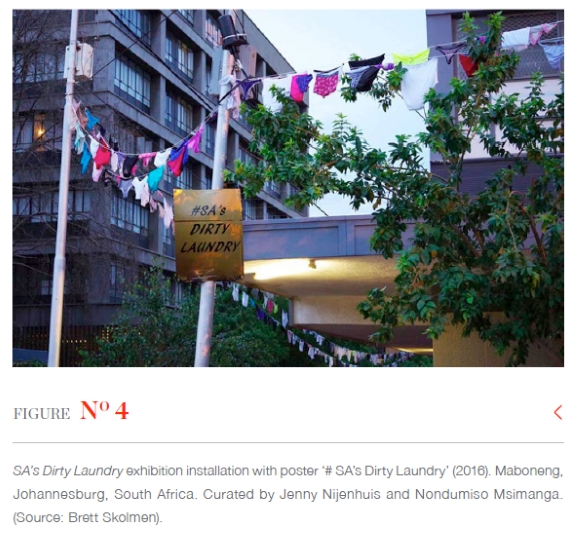

Towards the end of 2016, thousands of used panties lined the sky in Johannesburg's Maboneng precinct, as a 1.2-kilometre-long washing line was installed between Fox, Albrecht, and Kruger streets (see Figure 1). The washing line contained 3600 items of underwear strung together. At first glance, these strings of small, colourful clothing could, to the inattentive mind, resemble bunting flags and evoke a sense of celebration. Only on closer inspection would the viewer notice the peculiarity of the suspended items on a washing line, exposed for all to see.

SA's Dirty Laundry was organised by artists Nijenhuis and Msimanga and formed part of the 16 days of activism for no violence against women and children campaign.2Considered by the artists as an artivist project, its purpose was to increase consciousness of the horrific prevalence of rape in South Africa. As an organising method, they used statistics to add weight to their narrative. SA's Dirty Laundry requested sexual violence survivors to participate by donating panties as a way of sharing their stories symbolically. These items were used to create the open-air installation in the streets of Maboneng (Msimanga & Nijenhuis 2017:54). While the project also included street performances and a gallery exhibition entitled The things we do for love, it was the street installation that attracted my attention owing to its public venue and the usage of underwear as the main visual element. The installation was showcased for ten days.3

Conceptually drawing on the washing line trope also implies the use of clothing pegs. However, instead of pegs, 4000 safety pins were used to fasten the underwear to the washing line securely. I believe there is meaning embedded in the use of these pins. A safety pin has a sharp end that bends backward, but it also includes a clasp. The clasp performs two purposes: it forms a closed loop to fasten the pin to the underwear and washing line securely, but it also covers the end of the pin to protect the user from the sharp point. Thus, it metaphorically provides security and protection. The installation line and its components symbolically created what Valerie Kaur calls 'safe containers'4 where people can process emotions. Kaur explains the notion of safe containers as emotional spaces that are safe enough to express one's bodily impulses without shame or harming oneself or others.5 She believes that only when one gives difficult emotions and memories expression outside one's body, can one be in a relationship with it. Safe containers are useful for processing pain and practising 'tending the wound,' and such tending is not only moral but strategic, as it is 'the labour of remaking the world' (Kaur 2020:569).

Since the washing line was positioned outside the boundaries of a physical space, it could reach a wider audience, including accidental passers-by. In this way, the installation was remarkably accessible. Commenting on the importance of free access to creative work based on sexual violence, Winnie Li (2018:53) argues that opportunities that both allow broad audiences to engage with the topic and incorporate survivors' participation 'becomes the shared performance and witnessing of a narrative of sexual violence, enabling both the listener and the storyteller to benefit'.

The role of statistics

An open call-under the working title 'Panties plea'-initially invited survivors to donate their used underwear. The invitation appealed to survivors to 'consensually part with your panties'. The concept of consent, to give permission and agree to something, is crucial in discussions around rape and also when relying on the participation from survivors, and thus played an important role in this call to action. Between May and November 2016, the organisers gathered donations from various collection points in Johannesburg. During these collections, many self-narratives were spontaneously shared with the curators. Posters with 20 different messages were installed on street poles near the washing line as additional visual cues and to position the installation conceptually. The tag lines on these posters included 'Real men don't rape', '#1 in 3600', 'Rape is always a crime', and 'I never said "yes"' (see Figure 2).

In my interview with Nijenhuis (2022), she explained how they wanted to find a way to represent the shocking statistics of rape to audiences visually. Drawing from her experience in marketing for more than 15 years, she opted for a simple and clear message. Taking into account that many rapes are not reported, the organisers settled on the estimate of 3600 rape cases per day as indicated by a 2013 study conducted by The South African Medical Research Council (MRC) (Clouder 2013:207; Msimanga & Nijenhuis 2017:57-58).6 Statistics provide a firm basis of truth in support of a message, a sense of weight. A high statistic indicates that it is not merely a personal opinion, but that proof of such events exists. Accordingly, the use of statistics has a degree of detachment to it. They do not reflect how someone feels but are presented as facts. The exhibition, then, is a way to confront viewers with the reality of the statistics.

The statistics on which the installation was based were, however, criticised as Africa Fact Check argued that 3600 rape cases per day were much higher than generally accepted (Wilkinson 2016) (see Figure 3). It is important to consider that various problems exist about the accuracy of rape statistics in South Africa. Rape statistics are, for instance, reported as part of a lump sum under the broader category of 'sexual offences'.7 Police only provide figures for the total number of sexual offences- of which rape forms part-making it difficult to know to what degree the statistics reflect actual rape cases (Vetten 2014:2). Furthermore, because of shame, fear for safety, ostracising and victim blaming, many people do not report the crime, thereby severely undermining the accuracy of statistics-making it seem much lower than it actually is (Mashishi 2020).

Relying on 3600 panties, however controversial, to narrate the enormity of the problem of rape enabled the organisers to stir up a level of shock. Statistics can be overwhelming, and shock value can jolt people into awareness. One of the benefits of shock is its capacity to draw attention, often brought forth by something surprising or unforeseen. Because of these features, it can be understood as a forceful weapon given its potential to unsettle and challenge people with disturbing realisations, or in this instance, statistics (Thompson 1972:58). Seeing the number, moving around underneath the installation and viewing it from various angles affords it tangibility and objecthood. In a manner of speaking, the fact becomes three-dimensional. The shaming survivors so often face becomes visible. The curatorial tactic of hanging these 'dirty underwear' on a washing line metaphorically works to help 'cleanse' them by exposing the unjust shaming of survivors and by bringing them to audiences for this wrongfulness to be acknowledged. The range of panties becomes the installation's affective force, prompting viewers' response. Akin to verbalising a thought, this curatorial act thus brought the statistic into visual existence.

I believe such thought-inducing shocks may be imperative to confront viewers with new perspectives. It is as if the installation forced viewers to really see the outrageous number of panties forcibly removed to rape people each day. Confronted with a shocking statistic, I believe viewers were prompted to evaluate their assumptions and contemplate whether the enormity of the problem of rape is more severe than they might have thought.

The washing line

Combining a variety of 3600 panties on a washing line also created patterns, repetitions, and a sense of the multiple, which can be visually appealing and striking (see Figure 4). Camille Benda (2022:15), for instance, suggests that clothing is a forceful nonverbal tool, the mass use of which can create a compelling repeated image that can lodge in the minds of observers. As a symbolic repository of survivors' self-narratives, the series of panties through the streets of Maboneng became a visual device that both accentuated the shocking statistics of rape and created a visual impact to attract attention. On this level, I argue that using statistics played an important role in creating a sense of community.

The washing line presented an important platform for survivors to 'voice' their self-narratives, albeit symbolically. As Susan Brison (2002:51) argues, the telling and listening, or the visualisation and witnessing of self-narratives of rape, are all-important in enabling survivors to heal from the trauma caused by their assault. The different types of underwear displayed resembled the various preferences of the previous owners, weaving each personality into the narrative tapestry of the installation. The variation in the underwear thus denoted the range of stories that were told, keeping some of the singularity of each rape narrative. Consisting of the contributions of participating survivors, the strings of panties did not recount a single survivor's vision or experience. It instead collated the narratives of 3600 contributors, thereby circumventing the representation of persisting tropes. In this way, the participants had collaborative authorship of the project, infusing the exhibition with inclusivity and a sense of community. This approach relates to Megan Johnston's (2014:24) concept of 'slow curating', which emphasises the need for greater audience engagement in its association with socially engaged curating. It is thus relevant that slow curating places great importance on the utilisation of relational and collaborative processes in its objective to reach diverse communities. According to Johnston (2014:29) 'the main aim of slow curating is to open up space for dialogue and discourse'. Since collaborators and their input and participation become vital, the notion of slowing down and taking time becomes imperative-a strategy that the curators of SA's Dirty Laundry seemingly followed.

As Nijenhuis (2022) mentioned in our interview, the whole project was very sensitive. For instance, the unforeseen and abundant sharing of self-narratives at collection points was especially difficult.8 In her study, Li describes the personal and psychological cost of undertaking activist and creative labour to address sexual violence as compassion fatigue or empathy fatigue. She also affirms the need for self-care to mitigate burnout. Substantiating this notion of self-care, Nijenhuis (2022) recalled having to take a break during the organising months of the exhibition. In order to cope and subsist, Nijenhuis benefitted from the following mantra: 'I forgive myself; I forgive everyone; I am free'.

Even with these self-care tactics in place, she did not always feel brave enough to do it alone; therefore, she invited Msimanga to join her in navigating the project. Nijenhuis and Msimanga considered each donor a collaborator and part of the project. I also believe that the donors felt that sense of belonging-of partaking in the project-since many of them showed up as volunteers to help install the artwork. Nijenhuis also mentioned the vested involvement she noted in participants. She believes that the promise of anonymity influenced the size of the response. This, for me, signals a curatorial approach that creates connections and a sense of community. When participating and adding one's narrative to build and showcase the statistics, feelings of being connected to others often begin to form. Nijenhuis (2022) described the people who contributed to the installation as 'a cushion of voices' surrounding her own. They provided support and mitigated feelings of isolation and loneliness. Perhaps they even provided a sort of therapy for a shared trauma. The organisers also invited advocacy organisations to the adjacent gallery space-available for anyone needing to talk.9

Besides the promise of anonymity, I believe something else played a part in creating a sense of community. Both Msimanga and Nijenhuis were bravely honest to the media about being survivors of sexual violence themselves (Msimanga 2016:29). To describe the value and significance of this disclosure, I look to Brené Brown's understanding of vulnerability and what it inspires in others. For Brown (2012:98), braving vulnerability and shame, as Nijenhuis and Msimanga did in admitting a past trauma and initiating this challenging project, often inspires others to bravely acknowledge their vulnerabilities too. The Oxford Dictionary describes vulnerability as 'able to be attacked or harmed'. According to this interpretation, this is a dangerous position to be in, as one is unprotected and exposed (Waite & Hawker 2009:1038). In a talk entitled How to be fearless (2021),10 author Jessica Hagy explained that a person needs vulnerability to be completely honest, to show who they are and what they have been through. More than that, humans require vulnerability to connect with and relate to others and feel less alone. Continuing, Hagy explained that knowing others feel the same way is an effective normalising experience, whereas fear isolates, shames, segregates, and weakens a person. While vulnerability often feels like weakness, Brown (2012:65) maintains that admitting and showing one's vulnerability is almost always perceived by others as being courageous.11 In Hagy's (2021) opinion, others might be induced to share their vulnerabilities due to the sense of ease they experience when someone shares a vulnerable, honest story about themselves. As such, braving fear and vulnerability creates what Hagy (2021) regards as 'togetherness'. Acknowledging vulnerability gives way to connections to others-togetherness-and even a sense of community, providing a bulwark against isolation, fear, and shaming.

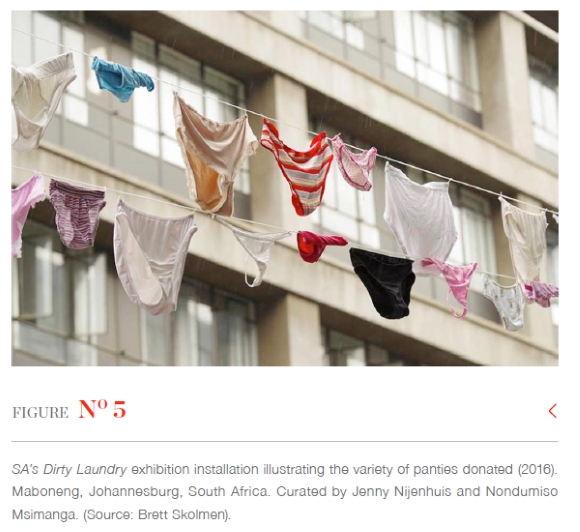

Hanging on the line, together and side by side, these panties were in a dialogic relationship with each other while also intertwining to form a chain of self-narratives of rape (see Figure 5). Each panty installed on the washing line added its own private narrative and collectively gave way to an almost unbearable metanarrative of rape in South Africa. Inspecting the lines, viewers were almost sure to spot a pair resembling what they would wear. In such cases, the familiar panty could assist viewers in the realisation that rape does not only affect other people. You could also be forced to part with your panties unwillingly.

Seeing is believing: Displaying unmentionables

The use of worn underwear or one's 'unmentionables'12 as a symbolic reference to rape narratives mark it as both an object and signifier inscribed with history. In considering the difference between hearing or reading about rape statistics and seeing it in visual and tangible form, as with SAs Dirty Laundry, I propose that it can be understood as similar to the divide between telling and showing. Or, in the words of Mitchell (1994:5), 'between "hearsay" and "eyewitness" testimony'. There is a space between an image or an installation and what it represents, just as there are gaps between verbal or written explanations of a given image and the image itself. For instance, David MacDougall (1998:257) argues that 'images and written texts not only tell us things differently - they tell us different things'. Using panties for the installation, the artists could draw on these items' associative power to reference feelings of objectification, shame, and symbolic resistance.

Nijenhuis (2022) recounted how the use of panties to demonstrate the shockingly high number of rapes (see Figure 6) was a natural choice because, as she said, 'it is the last thing removed from your body'. I would add that the panty also marks the location of violence. It is the one piece of clothing that bears witness to the violent act of sexually violating a body. It is not just the last thing taken off; it is also the last thing that stands between a possible victim and her rapist-a final layer of protection.

The notion of underwear providing protection also plays out within the realm of hygiene, which many authors have remarked on (see Barbier & Boucher 2004:17; Keyser 2018:4; Willett & Cunnington 1992:32). Positioned between the body and outerwear, underwear protects the body from clothes made of uncomfortable materials and simultaneously shield one's clothes from bodily secretions. Thus, it hides the messy reality of the body's functions as society seems repulsed by the traces the body leaves behind. As the cautionary saying goes, 'one should never wash one's dirty laundry in public'. In this installation, the title 'dirty laundry' conjures a similar sense of disapproval and shame to someone metaphorically 'airing' or 'washing' their dirty laundry where others can see. Society tends to be averse to conversations about uncomfortable and private matters in the public realm. SA's Dirty Laundry, however, subverts this idea of privacy and shamelessly exhibits second-hand panties. Hanging what is called 'dirty laundry' on a washing line- usually reserved for clean garments-brings a peculiar dialogue between metaphorical cleansing and what is considered 'dirty'. I argue that the focus on these materials and objects is, on the one hand, meant to reference the 'dirtiness' of feeling humiliated and ashamed-signalling a desire for cleansing. Additionally, the use of cleaning items as the structure for the artwork also suggests the healing notions of cleansing embedded in the material itself.

Another ritualistic function performed by lingerie is that of shielding the body's sexual zones from the gaze of others. As Ted Polhemus (1988:114) puts it, underwear prevents 'erotic seepage' in public encounters. Lingerie is in intimate contact with a body, being close to a person's skin and private form (Barbier & Boucher 2004:17). As a consequence, underwear is rarely revealed, as it is associated with nudity and the act of undressing-an erotically charged gesture (Willett & Cunnington 1992:33). In The psychology of clothes (1930), J.C. Flügel (1930:194) invokes this idea:

[g]arments which, through their lack of ornamentation are clearly not intended to be seen (such as women's corsets and suspenders, the coarser forms of underwear) when accidentally viewed produce an embarrassing sense of intrusion upon privacy that often verges on the indecent. It is like looking 'behind the scenes' and thus exposing an illusion.

Vestiges of this idea still exist today. Flügel's description also highlights the inherent tension present in underwear. While it conceals, it also reveals, and heightens awareness of the body's erogenous zones. By covering the genitals, one inevitably draws attention to the sexual parts of the body. In this way, lingerie is associated with both intimacy and cleanliness. Therefore, the use of panties as the main visual tool clearly returns us to the individual body. The fabric of underwear, however, is generally kept from view. Even the term underwear reveals its function-to be underneath and therefore hidden from sight, as an item of clothing that is shameful and requires privacy. Comparable to the way that discussions around rape are silenced, panties are covered and concealed by layers of clothing. Its purpose is to hide while also being kept out of sight.

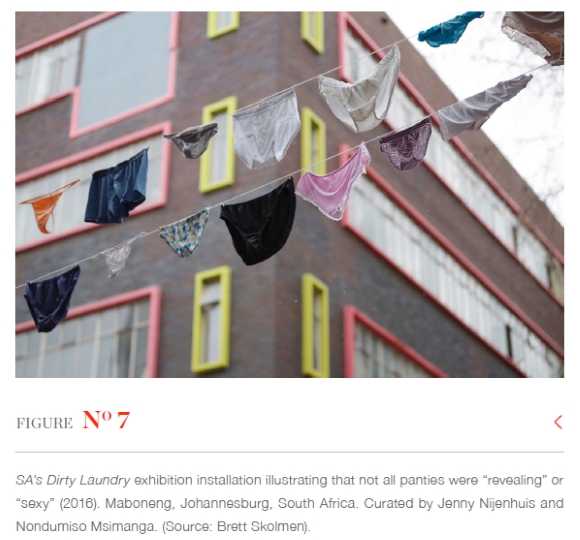

According to Chantal Thomas (2004:9), many men believe that women wear certain underwear to seduce them. Such a myth, coupled with the misguided notion that women are responsible for men's sexual behaviour, would then assume the underwear on the washing line to be particularly 'revealing' or 'sexy'. SA's Dirty Laundry, however, responded in the visual language of heterogeneity-representing the many preferences of individual survivors (see Figure 7)-a feature that renders the project particularly resilient.

What the organisers did not foresee, however, was resistance to the donation of used panties. Concerns and fears around trust emerged from possible participants. A private tertiary education institution offered to collect underwear for the project. Management, however, told the organisers that their donation request was met by 'a massive cultural response to the campaign'. As they reported, many of the black female students did not want to donate their used underwear, feeling it should be burnt and destroyed instead. Such resistance is not difficult to understand if one considers that underwear has become almost constantly attached to one's body. Humans are very rarely without these often hidden pieces of clothing. Being naked, or nearly naked, is a vulnerable state to be in. Thus, handing over one's used panties, or one's 'second skin', is akin to handing over a part of your nakedness for someone else to expose to the world. Allowing someone to display your used underwear is like putting one's vulnerability on view.

Considering the provenance of the various panties, their pasts are invariably linked to the person who wore them and resolved to gift them to the project to secure a place for them on the washing line. Each panty's past, in which ordinary people used them, migrates through time into the space of viewing. Even though it is removed from its original function, the panty may still be considered something that should remain hidden. Because the panty is forged into a substitute for rape survivors, it can also echo the shaming survivors often face; its purpose changed through the consensual participation of its previous owner. In being deployed to narrate the high statistics of rape in South Africa, these garments were transformed from their status as second-hand items to installation objects, thus acquiring an extra layer of meaning.

Rather than constituting physical representations of bodies, presence was evoked through the absence of the real, thus not allowing survivors to be forgotten. Each panty, an indexical fragment of the real, pointed to a reality beyond itself, attesting to an extant self-narrative. There was a deliberate omission of the representation of physical bodies. Grønstad and Gustafsson (2012:xvii) argue that such an absence of the body could be understood as 'a kind of phantom pain, evoking what has been done and what has been lost'. The panties thus acted as stand-ins for the physical bodies of survivors, signifiers tasked with narrating the occurrence of rape.

Conclusion

I believe that installing the exhibition outside the confines of an art gallery and in the streets of the city of Johannesburg, positioned the supposedly shameful and private narrative of rape in the public domain and in the midst of everyday life. Since the washing line was not situated within an enclosed space, the city landscape could more easily absorb it. Consequently, the exhibition's spatial arrangements reflected the need for rape narratives to be witnessed and for the censored dialogue of rape to be made public. As an artivist project, the use of statistics played a relevant role, the more so as the visual translation and display of the statistics rendered the exhibition especially striking, while at the same time drawing on the power of shock to help raise awareness. The conceptualising of a safe container- the washing line-was another important feature. By allowing survivors to symbolically 'voice' their self-narratives on the line, they were able to 'tend the wound' and not sit in silence.

Furthermore, the notion of participation and collaborative authorship did more than facilitate inclusivity. In the words of Nijenhuis, it acted as 'a cushion of voices'. In other words, it is easier to be brave when you are not doing it alone. There is power in the multiple, as opposed to the singular voice. Participation is not merely a strategy but is, at times, necessary for embarking on such a project. Presence is evoked rather than represented in SA's Dirty Laundry by exhibiting the one item that everyone wore when raped, namely underwear. Through this method, the panty was fashioned into a potent nonverbal tool or symbol, standing in resistance to sexual violence. Through the implied practices of washing, the curators brought the unmentionable to the forefront to expose 'dirty secrets' in an attempt to bring attention to and do away with the damaging consequences of misplaced shaming of survivors. The so-called 'dirty laundry' of sexual violence was 'tended to'. Underwear was 'washed' and 'aired' on the washing line in Johannesburg, allowing anyone to witness what has been done and how survivors are standing together to resist this atrocity.

Notes

1 In recent years, similar exhibitions have been displayed around the world such as the protest staged by the NGO Rio de Paz (Peaceful Rio) on Copacabana beach in Brazil, also in 2016. Large photographs of women's faces with red hand prints over their mouths were positioned in between 420 scattered pieces of underwear, some red and some white (Bearak 2016).

2 16 days of activism for no violence against women and children is a worldwide campaign to oppose violence against women and children. Its aim is to raise awareness of the negative impact of violence and abuse and to rid society of abuse permanently. It is held from 25 November to 10 December every year.

3 In concordance with the 16 days of activism for no violence against women and children campaign, the exhibition was held from 25 November to 4 December 2016.

4 Kaur's notion of 'safe containers' is derived from Wilfred R. Bion's Learning from experience (1962) in which he explains containment theory in psychoanalysis.

5 According to Kaur (2020:248) 'safe containers take many forms: shaking, weeping, venting, writing, art, music, dance, drama, meditation, trauma therapies, rituals, and ceremonies of all kinds.'

6 In 2010 over 56000 rapes were recorded at an average of 154 per day. And these are just the few women who report attacks to the police. With the low conviction rate for perpetrators and the high emotional toll, many survivors stay silent (Clouder 2013:207).

7 The Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act, 2007 (Act No. 32 of 2007, also referred to as the Sexual Offences Act), is an act of the Parliament of South Africa that reformed and codified the law relating to sex offences and collated 59 sexual offences under one category.

8 One of the donated panties was handed over in a brown paper bag and included a handwritten testimony. Honouring this act of trust, the panty along with its story was installed in the bag on the washing line.

9 The activations and advocacy groups present: People Opposing Women Abuse (POWA).

10 In the talk How to be Fearless (10 August 2021), Hagy is in conversation with Eric Zimmer from the podcast The One You Feed.

11 See Brown's (2012:73-84) explanation of vulnerability as courage as well as the importance of acknowledging vulnerabilities.

12 In the 19th and early 20th centuries underwear, in some instances, could not be referred to directly in polite conversation. To circumvent this difficulty the word 'unmentionables' was often euphemistically employed in its place.

References

Barbier, M & Boucher, S (eds). 2004. The story of lingerie. New York, NY: Parkstone Press. [ Links ]

Bearak, M. 2016. Women's underwear strewn on beach in Rio to protest Brazil's rape culture. The Washington Post, 8 June. [O]: Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/06/08/what-420-pairs-of-underwear-on-copacabana-beach-says-about-violence-against-women/ Accessed: 25 May 2023. [ Links ]

Benda, C. 2022. Dressing the resistance: The visual language of protest through history. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press. [ Links ]

Brison, S. 2002. Aftermath: Violence and the remaking of a self. Oxford: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Brown, B. 2012. Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. New York, NY: Gotham Books. [ Links ]

Clouder, C. 2013. Social and emotional education - An international analysis. Santander: Fundacion Botin. [ Links ]

Crous, M. 2016. 3600 panties project aims to expose SA's gargantuan rape problem. News24, 1 December. [O]. Available: https://www.news24.com/w24/archive/wellness/mind/3600-panties-show-prevalence-of-rape-in-sa-but-true-gravity-left-unexposed-20161201. Accessed: 20 February 2023. [ Links ]

Engel, B. 2015. It wasn't your fault: Freeing yourself from the shame of childhood abuse with the power of self-compassion. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications. [ Links ]

Flügel, JC. 1930. The psychology of clothes. London: Hogarth Press. [ Links ]

Gilbert, P. 1998. What is shame? Some core issues and controversies, in Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology, and culture, edited by P. Gilbert & B. Andrews. Oxford: Oxford University Press:3-38. [ Links ]

Gilbert, P & Andrews, C (eds). 1998. Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology, and culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Grønstad, A & Gustafsson, H. 2012. Ethics and images of pain. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hagy, J. 2021. How to be fearless.10 August. [O]. Available: https://www.oneyoufeed.net/how-to-be-fearless/ Accessed: 17 March 2021. [ Links ]

Ho, U. 2016. Coming clean: Knickers with a twist. Times Live, 15 November. [O]. Available: https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2016-11-15-coming-clean-knickers-with-a-twist/ Accessed 6 May 2019. [ Links ]

Johnston, M. 2014. Slow curating: Re-thinking and extending socially engaged art in the context of Northern Ireland. ONCURATING 24:23-33. [ Links ]

Kaur, V. 2020. See no stranger: A memoir and manifesto of revolutionary love. New York, NY: One World. [ Links ]

Keltner, D & Harker, LA. 1998. The forms and functions of the nonverbal signal of shame, in Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology, and culture, edited by P Gilbert & B Andrews. Oxford: Oxford University Press:78-98. [ Links ]

Keyser, AJ. 2018. Underneath it all: A history of women's underwear. Minneapolis, MN: Twenty-First Century Books. [ Links ]

Landsbaum, C. 2016. Artists hung 3,000 pairs of underwear in the street to raise awareness about rape. The Cut, 2 December. [O]. Available: https://www.thecut.com/2016/12/artists-hung-3-000-pair-of-underwear-in-the-street-to-raise-awareness-about-rape.html Accessed: 15 May 2019. [ Links ]

Li, WM. 2018. Art, activism and addressing sexual assault in the UK: A case study, in ArtWORK: Art, labour and activism, edited by P Serafini, J Holtaway & A Cussu. London: Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd:45-64. [ Links ]

Lykke Lind, P. 2016. Dirty laundry: Washing line art highlights South Africa's rape epidemic. The Guardian, 2 December. [O]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/02/dirty-laundry-washing-line-art-highlights-south-africas-epidemic Accessed: 15 May 2019. [ Links ]

MacDougall, D. 1998. Transcultural cinema: Edited and with an introduction by Lucien Taylor. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Maleke, D. 2016. 16 days of activism: Artists air out SA's dirty laundry. Huffington Post, 20 December. [O]. Available: https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/16-days-of-activism-artists-air-out-sas-dirty-laundry_uk_5c7e8d49e4b078abc6c0899e Accessed: 6 May 2019. [ Links ]

Mashishi, N. 2020. Are 40% of South African women raped in their lifetime and only 8.6% of perpetrators jailed? Africa Check, 23 March. [O]. Available: https://africacheck.org/fact-checks/reports/are-40-south-african-women-raped-their-lifetime-and-only-86-perpetrators-jailed. Accessed: 15 June 2023. [ Links ]

Matlala, F. 2016. Art installation airing out dirty laundry, literally... The Young Independents, 9 December. [O]. Available: https://www.tyi.co.za/your-life/news/art-installation-airing-out-dirty-laundry-literally Accessed: 5 May 2019. [ Links ]

Mitchell, WJT. 1994. Picture theory: Essays on verbal and visual representation. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Msimanga, N & Nijenhuis, J. 2017. SA's Dirty Laundry and The things we do for love: Love and artivism as process-protest. Agenda 31(3-4):50-59. [ Links ]

Msimanga, N. 2016. Airing South Africa's dirty laundry. Mail and Guardian, 14-20 October:29. [ Links ]

Nijenhuis, J. 2022. Artist, Plettenberg Bay. Interview by author. [Transcript]. 17 August 2021. Zoom. [ Links ]

Polhemus, T. 1988. Bodystyles. London: Lennard Publishing. [ Links ]

Serafini, P, Holtaway, J & Cussu, A (eds). 2018. ArtWORK: Art, labour and activism. London: Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd. [ Links ]

Stearns, PN. 2017. Shame: A brief history. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press. [ Links ]

Thomas, C. 2004. Preface, in The story of lingerie, edited by M. Barbier & S. Boucher. New York, NY Parkstone Press:7-10. [ Links ]

Thompson, P. 1972. The grotesque. London: Methuen & Co Ltd. [ Links ]

Vetten, L. 2014. Rape and other forms of sexual violence in South Africa. Institute for Security Studies 72:1 -7. [ Links ]

Waite, M & Hawker, S. 2009. Oxford paperback dictionary and thesaurus. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Willett, C & Cunnington, P. 1992. The history of underclothes. New York, NY: Dover Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Wilkinson, K. 2016. 3,600 panties for 3,600 rapes per day in SA? Everything that's wrong with this stat. Africa Check, 24 November. [O]. Available: https://africacheck.org/fact-checks/reports/3600-panties-3600-rapes-day-sa-everything-thats-wrong-stat Accessed: 5 November 2019. [ Links ]