Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Image & Text

versión On-line ISSN 2617-3255

versión impresa ISSN 1021-1497

IT no.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a23

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Breaking the 'Law of the Father': Linda Rademan's transgressive engagements with Afrikaner patriarchy in the home

Karen von Veh

Professor Emeritus, Visual Art Department, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. karenv@uj.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6125-3771)

ABSTRACT

Artist, Linda Rademan, was born in the mid-1950s in an Afrikaans home where 'the law of the father' pertained in all matters. She has professed ambivalence about her upbringing, which was circumscribed by an Afrikaner Nationalist ideology, underpinned by patriarchal dominance, and strictly conformed to the narrow Calvinistic precepts of the Dutch Reformed Church. In her work, memories of childhood and family dynamics are employed to expose the stranglehold of religious expectations, the permeation of male privilege, and the suppression of women's voices in Afrikaner culture.

In this paper, I analyse selected works in which Rademan has intervened in photographic memorabilia by embroidering and sewing or 'suturing' areas of her work. The use of sewing and embroidery has been employed as a feminist strategy since the early 1970s, and I argue that its use here not only aims to overturn the patriarchal hierarchy of artmaking but is an attempt to visually mend (suture) the psychologically damaging aspects of Rademan's childhood upbringing. In this way, her approach becomes a therapeutic means to engage with the painful process of self-integration, as well as a vehicle to redress the exclusion of women's voices in her family and culture by presenting an alternative image of Afrikaans womanhood.

Keywords: Linda Rademan, Afrikaner Patriarchy, Feminism, Sewing/Embroidery as Art.

Introduction

South African artist, Linda Rademan (1954), was born in South Africa to a conservative Afrikaans-speaking family and grew up during the era when the Nationalist government was in power. Her work is directly informed by her own experiences within what she identifies as 'a narrow-minded, Afrikaner, Dutch Reformed community in the 1950s and 60s' (Rademan 2017:2). Rademan's works that are discussed here are taken from her solo exhibition titled Threads of Ambivalence (2018) which consists of several installations and a combination of different materials and processes, all combined to a greater or lesser degree with sewing and embroidery. The title speaks of her personal ambivalence towards her patriarchal heritage. She states:

I was raised in the Afrikaner nationalist ideology, which encompassed patriarchy as a social order and the strict Calvinist doctrine within the Dutch Reformed Church as overarching parameters of daily life. Conservative values such as the pivotal importance of the nuclear family and the significance of being white were revered. As a child it was difficult for me to question the supremacy of Christian nationalism, since one of its patriarchal principles was precisely not to dispute authority, an expectation which permeated all aspects of life-at home, at school, in church and on all social fronts (Rademan 2017:2).

The entrenched patriarchy inscribed in the laws of the land and most obviously demonstrated through the hated apartheid laws (instituted in 1948) was underpinned by the Christian Nationalist policies of the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC). Charles Bloomberg (1990:1) suggests the DRC essentially provided a theological defence of Afrikaner Nationalism and ratified Afrikaner hegemony in politics.1 This view was not, however, uncritically accepted by all Afrikaners. While the symbiotic influence of church and state is acknowledged in Afrikaner history, the reader should remember that the extreme antipathy to the DRC expressed in this paper is a personal position, identified and presented by the artist.

The Nationalist policy of apartheid, while not the subject of this paper, does cast a light on the apparent need of Nationalist adherents to control and prescribe the behaviour and opportunities of 'the other'; whether that 'other' was a person of another race or of another gender. The laws of the land, underpinned by the DRC, reinforced Biblically prescribed expectations of chastity, subservience, and obedience for women and resulted in several generations of 'silenced' women who were only understood publicly as adjuncts to the men in their lives, and whose stories were not included in historiographical records of mainstream Afrikaner history (Blignaut 2013:600).2 The framing of Rademan's experiences is also informed by the fact that she grew up in a period before the feminist movement had any real effect on South African women's lives.3

The term 'Law of the Father' is associated with Jacques Lacan's psychoanalytic analysis of the three stages a child goes through before entry into patriarchal culture (Murray 2016:1). To explain it simply-this begins with the 'imaginary order', a pre-linguistic stage experienced by babies who identify with the mother and do not have any self-perception. The 'mirror stage' is when the child, at about six to eight months, gains a sense of selfhood by identifying itself (in a mirror), thus beginning the journey of separating from the mother (Murray 2016:1). The final 'symbolic stage' is where the child acquires language and recognises the 'Law of the Father' which can be identified by social rules and expected forms of behaviour imposed externally. At this point, the child understands that it must conform to shared social laws that govern society. 'This law, the big Other, as Lacan calls it, is of ultimate importance because it ensures positionality in society to continue undisturbed' (Silkiluwasha 2015:129). This law is, however, inherently patriarchal, according to Lacan, who maintains it is symbolised by the phallus. Thus women, who lack a phallus, make a negative entry into the symbolic order (Murray 2016:1) and are, by default, inherently disadvantaged.4

I aim to show here how Rademan's work attempts to overcome the values imposed by this 'symbolic order' to create an alternative form of selfhood and come to terms with her ambivalence and alienation. Her method is to use photographic and found or recollected traces from her childhood and intervene using needle and thread, to make works that engage transgressively with the identities imposed by patriarchy. Her work is underpinned by a feminist approach that seeks to redress a history of overlooking or ignoring female experiences, within the dominance of a value system defined by hegemonic masculinity.5 Sewing and embroidery are methods that have been employed as a feminist strategy since the early 1970s to acknowledge the value of crafted 'women's work', to remove it from the marginalisation of domesticity and overturn the prominence of traditionally 'significant materials' such as bronze, marble, or oil paints.

I argue that the use of sewing and embroidery in Rademan's work not only aims to overturn the patriarchal hierarchy of artmaking but also attempts to visually mend (suture) the psychologically damaging aspects of her childhood upbringing. Rademan (2017:55) notes that the threads evoke her ambivalence: 'The sutures may be seen as emphasising the site of difference or its opposite, the site of reconciliation.' In addition, loose threads left hanging in some of the works might indicate 'fraying', or perhaps disintegration. Alternatively, they might signify a work 'in process', evoking a state of incompletion or evolution. Both interpretations expose the disintegration of self that women experience under patriarchy and signal that their reconstruction is ongoing.

In this article, I discuss works from Threads of Ambivalence under two headings. The first, Problematic patriarchy, considers how selected works critique the prescriptive nature of a patriarchy that is underpinned by narrowly interpreted religious dogma, as experienced by Rademan during her childhood. The second group of works is discussed under Suturing new identities. This section concentrates on the importance of sewing as a Feminist strategy in Rademan's work. By using a feminist methodology that is associated with suturing and mending, as much as it is with pain and piercing, her working method expresses the ambivalence she feels towards her heritage and becomes a therapeutic means to engage with the sometimes-painful process of self-integration. In addition, it is a vehicle to address the exclusion of women's voices in her family and her culture, by presenting an alternative image of Afrikaans womanhood that attempts to redress years of silenced women in her family history, and thereby becomes a means to 'break the law of the father'.

Problematic patriarchy

Rademan acknowledges the strength and determination of her pioneering forebears but rejects the Calvinist patriarchal influence on her life and the way this has appeared to stifle and proscribe the lives of so many women in her family. Her rejection of authoritarianism manifesting in inflexible control created many conflicts in her childhood and youth, resulting in 'a perceived sense of otherness' that left her alienated and dislocated from her family heritage (Rademan 2017:2) and from her father in particular, as demonstrated in the work titled His master's voice (see Figure 1).

This is an enlarged colour photocopy of a two Rand note from approximately 1973, with an embroidered portrait of her father inserted in place of Jan van Riebeeck's face. Rademan (2017:71) explains that she deliberately chose the lowest denominational note available, as it corresponds with the low emotional value she ascribes to 'the patriarchal "voice of reason"'. It is interesting to note that she chose to work with an old denomination note. The Rand replaced the Pound in 1961 to mark the independence of South Africa and Jan van Riebeeck remained on the currency until 1996 (South African Reserve Bank). The figurehead of van Riebeeck is integrally colonial-he served as Commander and Administrator of the Cape Colony for the Dutch East India Company in the 17th century and subsequently became governor over the Cape Colony. With the contemporary post-colonial narrative, van Riebeeck has been associated with the Rhodes Must Fall movement, where anger at the colonial past has been demonstrated in public interventions into statues of contested figures, including van Riebeeck's.6 By using an old note from her childhood and not the contemporary currency that is marked with either the Big Five animals or Nelson Mandela, Rademan identifies her father (and his patriarchal views) as obsolete.

Her father's signature replaces that of the Governor of the Reserve Bank, and 'Reserve' is subtly altered to 'Reserved Bank'. This refers to the withholding of money as a form of control in Rademan's family. There was an expectation at the time that women would be wives and mothers while the men worked to support their families financially. In Rademan's family, the management of money was firmly in the hands of men and accordingly, they became the decision-makers in the home. Under these circumstances, financial insecurity resulted in the dependence of the women in her family and entrenched patriarchal authority.7 In Rademan's experience, the use of money (or the withdrawal of it) to attempt to exert power is illustrated by her father's interference in her choice of future career. Rademan's parents were divorced, yet her father still attempted to enforce his preference that she should study 'medicine at the University of Potchefstroom after matric' (Rademan 2017:71). He was so assured of his right to make important decisions on her behalf that he refused to contemplate her own wish to study art and withdrew any financial support for her education when she stood her ground.8 His bullying tactics severed their relationship for most of the rest of his life.

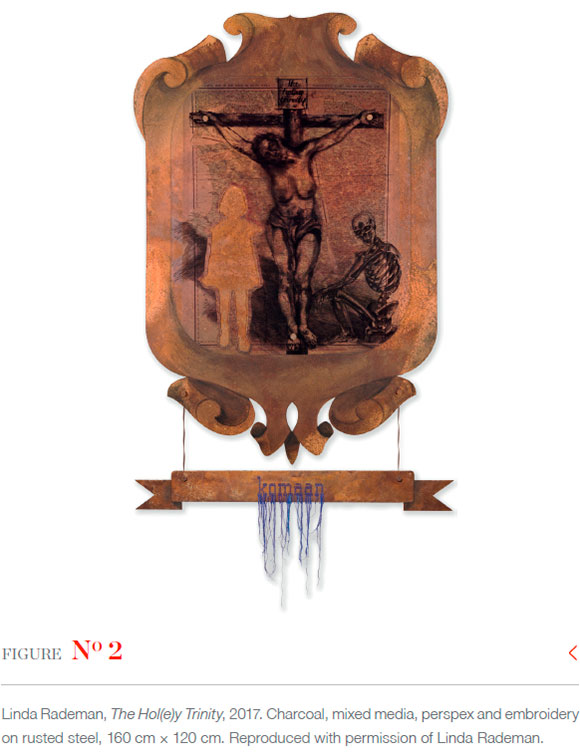

Rademan turns from the control exerted by her earthly father to a work that could be read as a direct attack on the institutionalised patriarchy of the DRC. She appropriates religious iconography in a mixed-media installation that parodies the sacred imagery generally associated with a Christian altarpiece, in a work ironically titled The Hol(e)y Trinity (see Figure 2).

The background is made of rusted steel, laser cut into the shape of an armorial shield symbolising the patriarchal nation-state. Overlaid on this substrate is a hand-drawn representation of an alternative (female) holy trinity, which has been printed onto perspex so the disintegration of the coat of arms is visible underneath. Below the shield, a rusted metal scroll has been suspended with the embroidered motto, Komaan, apparently unravelling to signify its lack of integrity in contemporary South Africa. Loosely translated 'Komaan' is an injunction to 'Come on!' or 'Get ahead!'. It was the motto embroidered on Rademan's high-school badge and thus serves, in Rademan's (2017:71) words, 'as an obligatory component of a nationalistic fixation in encouraging the invented union of the volk.' The background shield is also a symbol of nationalist impulses as it falls into a category of fetish objects, identified by Anne McClintock (1993:70-71) as the emblems by which nationalism is visually constructed. These motifs including 'flags, uniforms, airplane logos, maps, anthems, national flowers, national cuisines, and architecture' (Mc Clintock 1993:71), were ubiquitous elements of master symbols that supported the notion of Afrikaner ascendancy and created an 'imagined' identity of shared culture. Perhaps it also represents what McClintock (1993:67) identifies as '[w]hite, middle-class men [who] were seen to embody the forward-thrusting agency of national "progress"'. Rademan (2017:70) further alludes to nationalist fetish objects 'by drawing the original trinity image onto a torn topographical map of the Union of South Africa, from 1938, which symbolises heritage, identity, and the importance of land as an indicator of power in Afrikaner culture.'

The mother, the absent daughter and the skeleton replace Father, Son, and Holy Ghost in this unholy Trinity. The mother is appropriately crucified on the symbolic framework of patriarchal expectations. The daughter is merely a cut-out silhouette literally expressing Rademans feelings of lack, in the hierarchy of her family. In Biblical terms, the purpose of the Holy Ghost/Holy Spirit is to bestow wisdom, for example, Exodus. 31:3 (NIV Bible) states 'and I have filled him with the Spirit of God, with wisdom, with understanding, with knowledge and with all kinds of skills'. Rademan has replaced the Holy Ghost with a HoI(e)y skeleton, a desiccated, dead, useless pile of bones, in an attempt to expose the long-term impotence that must ensue in a strictly patriarchal dissemination of knowledge and power. There is also an allusion to the derogatory idiom of a 'skeleton in the closet'. This term refers to covering up discreditable or embarrassing events, such as the many recently publicised cases of systemic child molestation occurring behind the locked doors of religious 'sanctuaries' and perpetrated by ecclesiastical personnel who were put into positions of authority.9

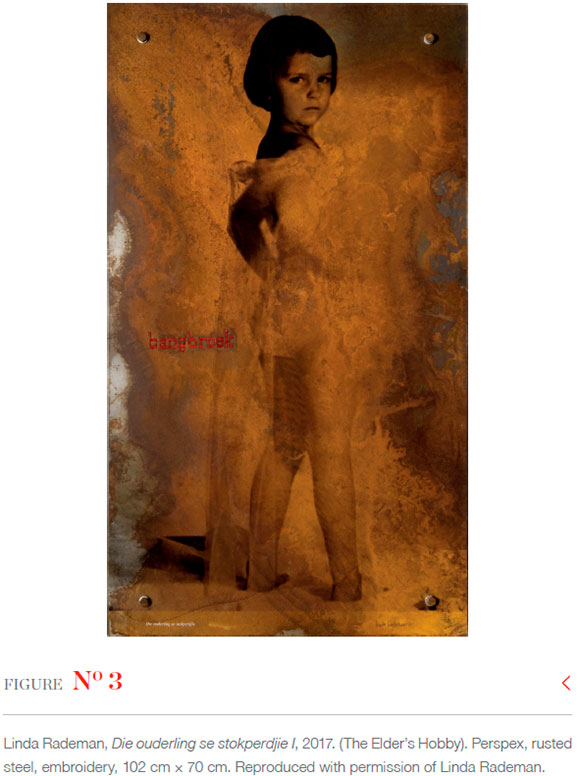

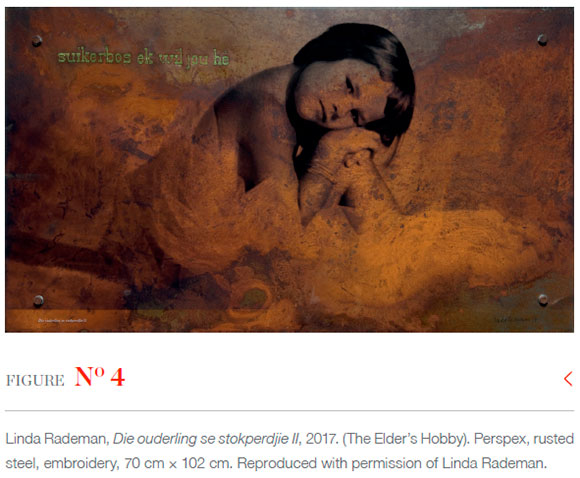

The last point is alluded to in the two images titled in Afrikaans: Die ouderling se stokperdjie I (meaning the Elder's hobby) (see Figure 3) and Die ouderling se stokperdjie II (see Figure 4). These consist of two individually enlarged photographs of Rademan as a five-year-old, printed on perspex sheets placed over rusted metal. Rademan (2017:57) retrieved these images from the family photo album, but explains that pictures were taken by an elder of the local DRC who photographed her on a weekday afternoon, alone in his garage, without her mother's consent.10 In the first, she is wearing only a pair of lace panties (provided by the photographer), and in the second, is wearing nothing but a transparent drape of netting.

The embroidered Afrikaans word "hangbroek" (meaning scaredy pants) has been layered onto the first image-sewn into the rusty metal below the perspex. The suggestive motif "suikerbos ek wil jou hê" (Sugarbush I want you) from a popular Afrikaans song is embroidered on the other. In these images Rademan (2017:57) uses the transparent perspex, as in the previous work, 'deliberately and metaphorically, to "expose the rot" beneath (in this case, the paedophilic intentions behind the adult male gaze)'.

Laura Mulvey (1984:362) supports the argument that women in a patriarchal culture are 'bound by a symbolic order' and within this framework, they exist as a bearer of meaning rather than maker of meaning. In the case of these images, the five year old Rademan carries (bears) the fantasies and obsessions of the church elder without any agency of her own. She is, in Mulvey's words, the object of desire of 'the male gaze' (Mulvey 1984:366). Lacan's negative identification of women as 'lacking' within this symbolic order plays out in Mulvey's analysis. In Rademan's case, the Elder's power is bestowed and supported by his position in the church and, in this instance, he also carries the power of the subject who is looking at and controlling the objectified child, thereby revealing his self-serving abuse of the Calvinist patriarchal system of authority. While this records a personal event in Rademan's childhood, these images also permeate cultural and historical contexts to reveal how the patriarchal construction of women as objects functions. Rademan (2017:59) explains that 'Even if [she] had been capable, at the time, of understanding his questionable motives, [she] would not have been able to deny the elder's authoritative male request to pose.' She also records how the control exerted by the DRC affected her mother's reaction to the photographs when they were presented to her. She was disturbed enough to forbid Rademan from returning for further photographic sessions, but was so programmed by the patriarchal expectations of womanly behaviour prescribed by her church that: 'she did not consider it "her place" as an "insignificant" female member of the congregation to lay a complaint against the elder' (Rademan 2017:60). In other words, she was 'silenced' by her fear of the authority of church and culture.

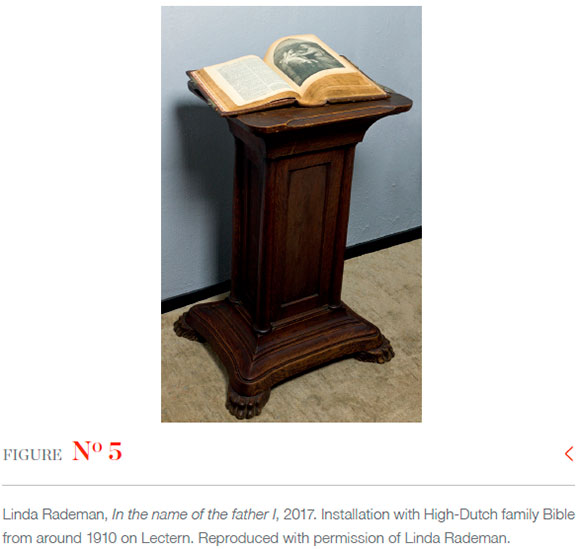

Rademan's diptych, In the name of the father I and In the name of the father II (See Figures 5, 6 and 7), further engages with what she perceived as the influence of the DRC on the silencing of Afrikaans women. Saul Dubow (1992:210) is of the opinion that '[d]eeply encoded patterns of paternalism and prejudice are an essential part of the Afrikaner nationalist tradition'.11 The permeation of paternalism is reinforced by Calvinist doctrine suggesting that all males, including husbands, fathers, the Elders and the clergy, represent God on earth (Vestergaard 2001:20). To undermine this status of men with authority in her life, Rademan has used a lower-case "f" for father in the title, inferring their lack of godliness.

The first part of the diptych consists of a leather-bound, high-Dutch family Bible from around 1910 displayed on a wooden lectern. The Bible is a book written by men, and to demonstrate this bias it is opened to a page that reveals one of the many scriptural passages which stipulate 'suitable' womanly behaviour. Among other things, suitable behaviour would include submission, deference, and silence. An example of this expectation can be found in 1 Tim. 2:11-13 (NIV Bible) which states: 'A woman should learn in quietness and full submission. I do not permit a woman to teach or to assume authority over a man; she must be quiet. For Adam was formed first, then Eve.' This power relation is addressed and countered in the second part of the diptych, which consists of a christening dress made of tea bags sewn together and covered in embroidered verses from the Scriptures. Each verse has been chosen by Rademan because it undermines the identity and role of women as equals and attempts to control and silence them by exhorting submission and obedience (Rademan 2017:65).

The ideas expressed in these scriptures were strongly advocated by a conservative Dutch statesman, historian, theologian, and philosopher, called Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920). Extrapolating from Biblical texts, Kuyper stated that the 'natural woman' was politically ignorant since 'her strength naturally lay in her lower body while the man, by nature and God's grace, possessed sharpness of mind' (Landman 2005:sp). Kuyper further noted that 'it was unnatural for women to vote since it was ordained in the Bible that the head of the family should vote on behalf of the whole family' (Landman 2005:sp). Kuyper's views, while historic in context, have some relevance because they were accepted at the time by the DRC. Kuyper's ideology was not necessarily fully embraced by DRC congregations, nor did they persist into the mid-twentieth century, yet there are vestiges of such patriarchal sentiments that inform certain conservative church dogmas relating to women. The ramifications of this historic depoliticisation and silencing of women are identified by theologian, Christina Landman (2005:sp), who explains:

For most of the twentieth century, Afrikaner women remained captured in the stereotype of the good wife, who was too pious to be political. When Afrikaner men, quoting Kuyper's idea of "soewereiniteit in eie kring", gave birth to the system of apartheid (1948-1994), Afrikaner women remained silent. Local Calvinism, moulded on the ideas of Abraham Kuyper, was as sexist as it was racist. For almost fifty years it allowed only the voices (and writings) of white men to be heard and read.

In the name of the father II hangs on the wall adjacent to the open Bible as a subtle image of defiance. It is a subversive response to the introduction of women into the 'symbolic order' through the ritual of christening as a religious and cultural rite of passage. It is a Christian ceremony that marks the child's acceptance within the father's belief system, or 'The Law of the Father', by formally bestowing on the infant their given names and acknowledging their father's surname. This rite dovetails with Lacan's final stage of childhood identification, where the child submits to the shared laws that govern the father's society, thus ensuring stability and continuity. The negative aspects of a girl child's entry into this stage are illustrated in the biblical verses that Rademan has painstakingly embroidered on the christening dress. The verses express 'Laws' of expected womanly behaviour within a system where she is expected to honour, submit to, and be subservient to men. The christening dress is, however, now displayed in an archival cabinet, suggesting it is an outdated relic of past beliefs and no longer relevant-something to be looked at as a curiosity, referring as it does to the outdated notion of women's silence and submission.12

The teabags used to make the Christening dress, in conjunction with the act of machine sewing them together and then hand decorating them with embroidery, renders the medium as message. The dress has been created in the medium of domestic labour (clothing for the family made by sewing and needlework). Such activities were considered part of a woman's duty in the home. Yet the conceptual shift in making it an artwork, adds to the ironic messages embroidered onto the dress and turns them into symbols of women's defiance. The choice of tea bags for the dress is similarly subversive. They convey notions of home comfort and allude to the subservience of women/wives who are expected to nurture, support, and feed their families. However, now the tea bags are used satirically, divested of their function and ironically carrying biblical injunctions identifying expected womanly behaviour-now presented as the topic of critique. As with all the sewn works the finely embroidered texts appear to be unravelling in places as if their meaning for the child who should wear the dress is slowly eroding.

Suturing new identities

Rademan's use of sewing, as mentioned in the introduction, also plays a major role in the reconstruction of her identity, helping to mend or 'suture' the cultural memories that cause her such distress. This is demonstrated in the work above where tea bags are stitched together, and where the embroidered verses on the dress might be identified as the scars of the patriarchal past, created here by the needle. Yet these are scars that add new value and meaning to a mere piece of clothing. Sewing on an artwork immediately alerts the viewer to the historic devaluation of anything resembling 'women's work' or craft, such as sewing, ceramics, or weaving. According to Roszika Parker (1984:5) the division between 'art' and 'craft' arose during the Renaissance when women were increasingly sewing or embroidering at home without pay, rather than professionally in workshops. Parker (1984:5) also notes: 'The development of an ideology of femininity coincided historically with the emergence of a clearly defined separation of art and craft.' Femininity is thus closely bound up with the notion of amateur work, in specific ('non art') media, carried out in the domestic sphere and, accordingly, 'craft' has been relegated to a lower status than 'art' in the patriarchally instituted hierarchy of art making. As Parker (1984:5) points out: 'The art/craft hierarchy suggests that art made with thread and art made with paint are intrinsically unequal: that the former is artistically less significant. However, the fundamental differences between the two are in terms of where they are made and who makes them.

The craft/art debate in Afrikaner culture has been discussed by Lise Van der Watt (1996:54), who explains that historic patriarchal constructs of ideal Afrikaner womanhood prescribed domestic endeavours, such as needlework in the home, or participating in nurturing aspects of welfare, as suitable tasks for Afrikaner women. This identification of activities reflects the patriarchal argument that embellishing the home is a suitable womanly pursuit, although the results are never acknowledged as having any significant artistic value. Van der Watt (1996:54) goes on to suggest that by praising such accomplishments and elevating the Afrikaner woman's role as wife, homemaker, and mother, men had found 'a cunning way of suppressing her without being too obvious about it'.13 Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock (1981:69) suggest that craft includes a consideration of the function and purpose of the crafted object and is identified and valued as a language of material, provenance, and making. The makers are of secondary importance, particularly if they are women, which corresponds with Parker's (1984:4,5) statement, 'When women embroider, it is seen not as art, but entirely as the expression of femininity. And crucially, it is categorised as craft.'

The combination of sewing and embroidery evidenced in The Name of the Father II lies at the heart of Rademan's subversive intent in resisting the structures of patriarchy. In this aspect, her work follows a feminist strategy that questions patriarchal hierarchies of artmaking. 'First generation' feminist artists addressed this inequality by choosing to create works aimed at the art markets but made in traditional craft media.14 Janis Jefferies (1995:168) points out the problematic nature of further polarising art and craft in this way when she says:

'Outside' culture, 'outside' language, 'outside' meaning, this construction of the personal as political took 'nature' for a feminine subculture. There could be no covert or tacit women's cultural traditions that could escape an essentialist ideology.

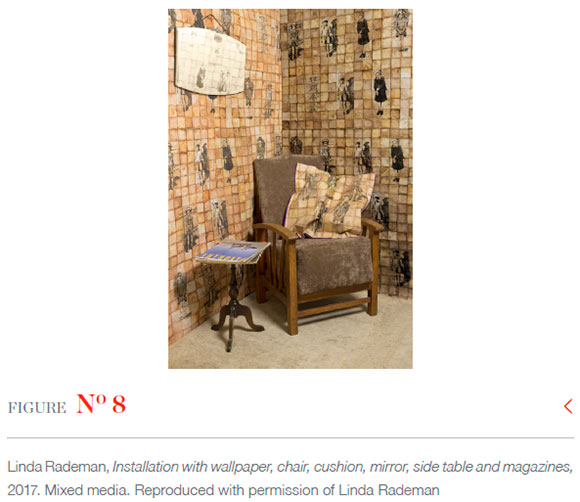

Rademan's introduction of the craft theme, on the other hand, is not trying to 'reclaim' these methods or accord them status within their traditionally instituted categories, but rather reveals the artificiality of such categorisation, as seen in figure 7, and in her Room installation (see Figure 8).

Tea bags are used, as in The Name of the Father II, as emblems of self-sacrifice, this time in an installation set up to look like the corner of a lounge from the 1960s. The used teabags are the substrate for multiple individual dry point images of Rademan as a child, dressed for church in her best clothes and sourced from family photographs. The repetition of this demure girl reinforces an 'implied imposition of piety' (Rademan 2017:60) that belies the natural exuberance of a child or Rademan's inherent rebellion. She explains that the rigour of church rules and what she interpreted as the judgemental vigilance of the DRC were ever-present in her family situation during her youth. She was obliged to attend church services with her family which, she states, 'was never an enlightening experience' as the gender bias of DRC dogma presented more restrictions than opportunities and left her feeling marginalised and inadequate (Rademan 2017:23). She describes the sermons as a constant litany of 'reprisal and atonement ...delivered to the submissive congregation [always by a male minister] from a much-higher-than-eye-level pulpit'15(Rademan 2017:23). The sense of being 'talked down to' led to low self-esteem, and the constant berating for sinful deeds (which was probably aimed at terrifying the congregation into good behaviour) created a sense of constant anxiety in the young girl and exacerbated her gender-based feelings of inferiority.

This manner of 'hellfire and brimstone' teaching is reminiscent of historic modes of rhetoric as found in 'the pessimistic, guilt-ridden piety of the "Nadere Reformasie"' (Landman 2005:sp). Landman (2005:sp) explains that the writings of these Dutch Pietists were introduced to South Africa during the latter part of the 18th century. Diaries and poems of Afrikaans women at this time displayed the effects of such teaching including:

... an obsession with hell, Satan and personal sin, fantasies of God's physical presence and care, the experience of regular divine visions, the habitual reference to the self in humiliating language, the use of biblical verses as deus ex machina, and a strong suspicion of the threat of many personal enemies, including Satan and the heathen (Landman 1994:12).

It appears that the feelings of humiliation and fear of sin experienced by Rademan were inspired by a similar antiquated approach to religious exhortation. The church, rather than a place of refuge, generated such anxiety in the young girl that in later life she rejected the religion of her forebears. The problematic nature of such a punitive form of religious teaching is alluded to in the process of making the etchings for this work. Rademan 'drew onto used x-ray plates, rather than traditional zinc plates to underline the metaphorical significance of their ability to expose problem areas' (Rademan 2017:61). While this connection refers to Rademan's own 'problematic' experience, she has noted that she sees the submission of women to the authority of the church in contemporary times as an ongoing problem (Rademan 2017:61).

The wallpaper is titled Wallflowers, denoting the expected behaviour of little Afrikaner girls (and women) in her community. They are seen but not heard, idealised and well-behaved voiceless background figures like wallpaper motifs. The cushion, titled Part of the Furniture, continues the repetition of these motifs. As a cushion, it is a practical household object, and the room setting deliberately identifies both cushion and wallpaper as domestic embellishments. They both also engage in the discourse around the difference between art and craft, between 'women's work' and artmaking. What distinguishes these two aspects of the room installation is that they are, in fact, also part of an art installation. As such they demonstrate value in aesthetic and artistic terms and have conceptual significance that goes beyond their 'usefulness', thereby transcending their lowly decorative/domestic status.

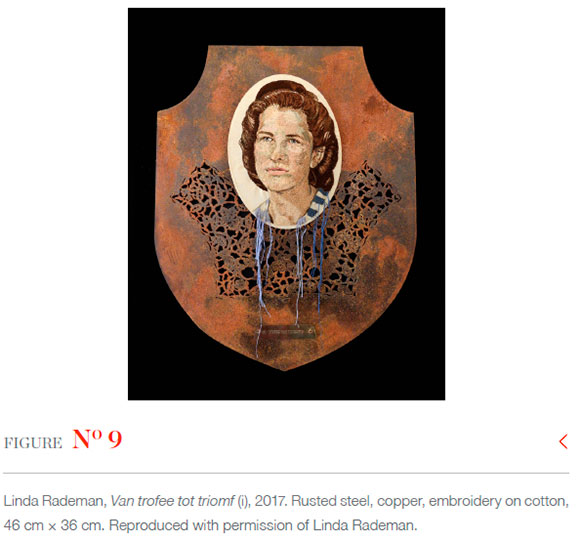

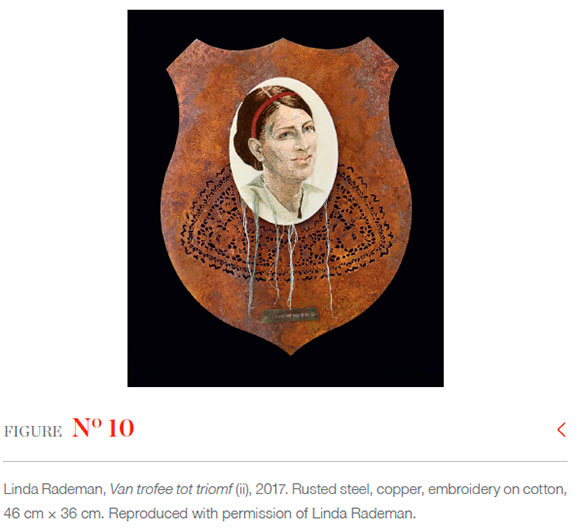

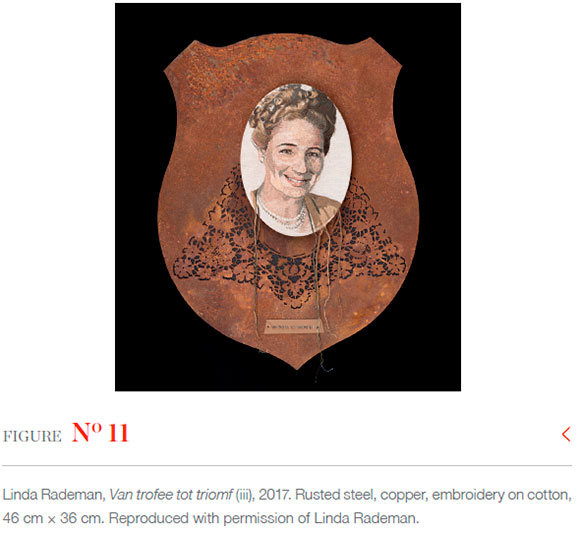

Continuing the art vs. craft theme, Rademan created four portraits representing her female family members to acknowledge their influence in her life and recognise lives lived in submission and enforced silence. With reference to Roszika Parker's (1984: 5) quote above, about categorising embroidery as only a craft that fundamentally expresses femininity, these portraits are embroidered as art, rather than painted in oils, in what Rademan (2017:74) calls 'an emphatic rejection' of the trivialisation of needlework as just a craft. It is important in this instance to note that portraits are not usually embroidered objects, nor are they 'useful' objects. These works do not subtly blur the categories but are exquisitely wrought portraits that defiantly embrace 'fine art' formats in 'non-art' materials as artworks in their own right.

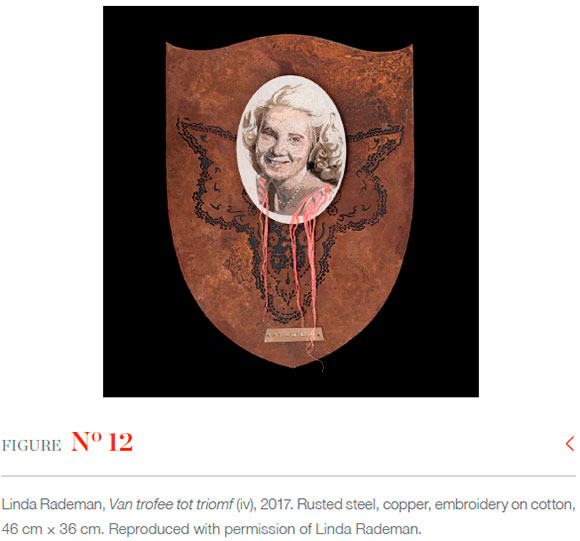

Titled Van trofee tot triomf (From trophy to triumph) (see Figures 9-12), each portrait is individually displayed on plaques of rusted metal shaped like shields, in a parody of hunting trophies. Hunting has evolved from a necessary activity related to provision, into a popular (mainly masculine) recreational pastime in South Africa, where killing helpless animals becomes a sport. Instead of food, the animals now exist as trophies, placed on walls to signal the hunter's status, wealth, and prestige. They signify his ability to absorb the considerable expenses associated with the hunting industry and to demonstrate his skill as a marksman. In these works, on the lower part of each plaque, the title of the series is punched into a bronze label. The labels parody name tags for dogs, proclaiming possession and implying control.

Rademan has replaced the severed animal heads with portraits of ordinary Afrikaner women (not remembered for any heroic deeds) chosen from her family photo album. Each portrait is executed on an oval-shaped background signifying an indication of their worth. Historically, oval formats were often used for portraits made to honour national male war heroes or civic dignitaries (Du Toit 2001:81). This format would even appear in newspaper portraits of men being valorised or acknowledged for some achievement. The irony of these women being honoured, yet simultaneously presented as trophies and as possessions, speaks to the ambivalence Rademan feels about her own history and heritage.

On the plaque, where the animal's neck and shoulders would have been attached, Rademan has incorporated four historic lace-collar designs, which were laser cut into the metal. The first one (see Figure 9) is reproduced from a collar designed and made by Emily Hobhouse at the lace-making school she established after the Anglo-Boer War. It is now archived in the National Women's Memorial and War Museum in Bloemfontein, thereby gaining some recognition for its fine workmanship. It is, however, admired as a beautiful piece of material culture without achieving the status of fine art, due to its 'useful purpose'. The other three are exquisite but nameless, unsigned collars dating from around 1914, now housed in the Richmond Museum in the Karoo (Rademan 2017:76). The women in the portraits are also not identified, but the collars link these family members with their Afrikaner heritage and evoke the thread of anonymous, unacknowledged pioneering women who preceded them. By visualising these women from her own family history Rademan pays tribute to them and includes them in her attempts to redress women's exclusion from the rigid master narrative of Afrikaner history (Rademan 2017:77).

As with previous works Rademan's embroidery is both exquisitely and painstakingly executed, yet threads are left hanging to signify that this, too, is not finished. These are all works in progress from a historical and psychological point of view. Their history is also Rademan's history and her acknowledgment of them is her way of giving a voice to these previously silenced forebears as well as to herself as a liberated woman.

Conclusion

While all the works discussed here express a definitive rejection of Afrikaner patriarchy and Calvinist dogma, played out in dishevelled threads and transgressive iconography, they also include the 'suturing' of a fractured past, constructing alternative 'voices' for the silenced women in Rademan's history and 'mending' her childhood memories. The physical process of sewing by hand is slow and repetitive. It becomes a form of meditation enabling Rademan to express her ambivalent self as social subject, able to acknowledge the 'weight' of her roots, but discard their ongoing effect on her as past realities are unravelled and reconfigured; thus breaking with the constructs imposed by 'the Law of the Father'.

Notes

1 A certain stream of Christian nationalist history promoted the notion that God made the Afrikaners his chosen people by guiding them through enormous suffering at the hands of the British, and by entrusting victory to them in their battles against the black heathen (Moodie 1975:10). Whether this is true or not, it is an undeniable fact that privileged whites wittingly or unwittingly exercised their domination over people of other races during the apartheid era.

2 When speaking of 'silenced' women I am referring to FA van Jaarsveld's assertion (in Blignaut 2013:598) that Afrikaner nationalist history is tainted by the 'abject neglect of women' and women's voices are therefore never heard. While Charl Blignaut (2013:598) does not fully agree with van Jaarsveld's statement, he does point out that in authoritative accounts of nationalist histories Afrikaner women are viewed in two different ways. Firstly they are identified along symbolic lines (as volksmoeder for example) that merely support the ideals of Afrikaner nationalism, or they simply do not appear at all. Liese van der Watt (2005:94) explains that the volksmoeder symbol, 'combined domesticity with service and loyalty to the family and the Afrikaner volk,' thus indicating the subsidiary role of women even when they were being praised.

3 For information on patriarchal resistance to the Feminist movement in South Africa and other factors delaying the acceptance of equality and autonomy for women, see Brenda Schmahmann's 2015 article: "Shades of discrimination: The emergence of feminist art in Apartheid South Africa."

4 Lacan's identification of the patriarchal basis of the social order and the implications thereof have been critiqued and adapted by feminist psychoanalysts such as Julia Kristeva and Helene Cixous, for example, but during Rademan's childhood such revisions, and indeed the rise of feminism, had not yet disrupted the hegemony of Afrikaner patriarchy.

5 Hegemonic masculinity is a style of masculine identity that has been associated with wealth and power, where men are able to 'legitimate and reproduce the social relationships that generate their dominance' (Carrigan, Connell & Lee 2002:112).

6 See for example the article in the Cape Argus (Lalkhen, Roomanay & Ritchie 2020): 'City's statues: If Rhodes must fall, van Riebeeck must also fall.'

7 Historic laws created a precedent for such behaviour. Marijke du Toit (2003:168) points out that male dominance was wielded over financial and property issues between the years 1904 and 1924. Husbands were given power under Roman-Dutch matrimonial law, which gave them 'guardianship' over their wives, allowing them free reign to deal with assets from joint estates as they pleased (Du Toit 2003:168). In addition the DRC prescribed that only male offspring should inherit from their parents.

8 Rademan (2017: 71) gratefully acknowledges that she was fortunate enough to obtain a bursary for her chosen studies as 'an opportunity enabled from an advantaged position by Afrikaner nationalism'. She goes on to note that her brother managed to avoid any engagement with the family's patriarchal power play by declining a tertiary education altogether.

9 See for example: https://www.ministrymagazine.org/archive/1991/01/sexual-molestation-of-children-by-church-workers or https://home.crin.org/issues/sexual-violence/child-sexual-abuse-catholic-church There are many more reports available via google or published in newspapers or in news reports indicating the prevalence of this problem.

10 Rademan (2017:60) explains that when the Elder gave the photos to her mother she was forbidden to attend any more 'modelling sessions' but still does not understand why her mother kept the photos.

11 Patriarchy was, in fact, the norm for both Afrikaner and British cultures during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, so was therefore inherent in the development of Afrikaner nationalism.

12 Rademan (2017:67) has stated: 'this work represents another "thread of ambivalence" in my life. The christening dress is the vehicle for expressing my dissatisfaction about the silence of women, and about the naming ritual that bestows the patriarchal family name. Ironically, I have chosen to keep and still carry my patriarchal surname; I have never adopted a husband's surname through marriage.'

13 Van der Watt (2005:94-108) further affirms that in Afrikaner visual history 'craft' is trivialised in relation to 'art' using the production of the Voortrekker Monument tapestries as an example of this bias in action. Despite the idea of a tapestry frieze first being proposed and conceived by a woman, Nellie Kruger, in 1952, the initial design work for the 15 commemorative tapestries was carried out by WH Coetzer-a male South African artist. Coetzer's designs were then executed in tapestry by nine women who worked for eight years to complete them, with the cost of the work subsidised by Afrikaner women from all over South Africa who collected R26 000 towards the project (Van der Watt 2005:96-99). Despite the work being initiated, paid for, and made by women, when they were finished the women had to ask permission to embroider their names onto the panels they had produced. Nellie Kruger (1988:29) explains that 'the Board of Control [of the Voortrekker Monument] consented provided that their signatures "would not be prominent".' Van der Watt (2005:107) points out, however, that ironically the 'artist' Coetzer's initials or, in the case of the middle panel his full name, appeared conspicuously on each tapestry. Such lack of acknowledgment for the skill and participation of the women who worked on these tapestries arises from the historic understanding of a value difference between craft and art.

14 Examples that spring to mind are the works of Judy Chicago, such as her Dinner Party (1979) which combines sewing and ceramics. Not only were the materials and methods related to craft but, by creating the work as a group project, Chicago was recreating the notion of the traditional craft collectives where women would historically work together, sewing and quilting. By doing this she hoped to point out that these 'female traditional craft' categories are an historical fact. By creating work following these 'devalued' practices, Chicago hoped to glorify the inherent potential of women's creativity. Miriam Schapiro, also working in the 1970s, collaged printed dress materials on to canvas. These 'femmages', as she termed them, also carry references to quilt making. Miriam Schapiro's work has been criticised by later feminists in that she was following the formal rules of traditional art making (ie. the balancing of line, tone, colour, and shape etc.). Her art often tended to be abstract-almost a reworking of the modernist principles within which she worked at the outset of her career. She was accused of merely substituting cloth for more traditional art-making materials, and was therefore not considered truly subversive. Judy Chicago was also problematic for later feminists as she was seen to embrace biological determinism through her glorification of the biology of women. She has also been accused of reinforcing patriarchal stereotyping through her perpetuation of categories of artmaking that were traditionally confined to production by women for use in the home. Vaginal imagery only served to further marginalise craft production rather than entrench it as a mainstream art practice.

15 Female ministers, deacons or Elders were not permitted during this time. Yolanda Dreyer was the first woman to be ordained in the Nederduitsch Hervormde Kerk van Afrika, and only in 1981 (Landman 2003:3).

References

Adams, R & Savran D (eds). 2002. The masculinity studies reader. Boston, MA & & Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Arnold, M & Schmahmann, B (eds). 2005. Between union and liberation: women artists in South Africa 1910-1994. Aldershot: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Blignaut, C. 2013. Untold history with a historiography: a review of scholarship on Afrikaner women in South African history. South African Historical Journal 65(4):596-617 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02582473.2013.770061 [ Links ]

Bloomberg, C. 1990. Christian Nationalism and the rise of the Afrikaner Broederbond in South Africa 1918-48. London: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Broude, N & Garrard, MD (eds). 1982. Feminism and art history: questioning the litany. New York, NY: Harper Collins. [ Links ]

Carrigan,T, Connell, R & Lee, J. 2002. Toward a new sociology of masculinity, in The masculinity studies reader, edited by R Adams & D Savran. Boston, MA & Oxford: Blackwell:99-118. [ Links ]

Deepwell, K (ed). 1995. New feminist art criticism: Critical strategies. Manchester & New York, NY: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Dubow, S. 1992. Afrikaner Nationalism, apartheid and the conceptualization of 'race'. Journal of African History 33(2):209-237. [ Links ]

Du Toit, M. 2003. The domesticity of Afrikaner Nationalism: volksmoeders and the ACVV, 1904-1929. Journal of Southern African Studies 29(1):155-176. [ Links ]

Du Toit, M. 2001. Blank verbeeld, or The incredible whiteness of being: amateur photography and Afrikaner Nationalist historical narrative. Kronos, Journal of Cape History 27(1):77-113. [ Links ]

Jefferies, J. 1995. Text and textiles: weaving across the borderlines, in New feminist art criticism: Critical strategies, edited by K Deepwell. Manchester & New York, NY: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Kruger, N. 1988. Die geskiedenis van die Voortrekkermuurtapisserie: Geskryf op versoek van die beheerraad van die Voortrekkermonument. Pretoria: ATKV. [ Links ]

Lalkhen, Y, Roomanay, S & Ritchie, D. 2020. City's statues: If Rhodes must fall, van Riebeeck must also fall. Cape Argus. 24 June 2020. [O]. Available: https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/cape-argus/20200624/281509343447209. Accessed on 26 June 2023. [ Links ]

Landman, C. 2005. 'Leefstyl-Bybel vir vroue': Afrikaans-speaking women amidst a paradigm shift. Studia Historia Ecclesiasticae 31(1):147-162. [ Links ]

Landman, C. (ed). 2003. Die leefstyl-Bybel vir vroue. Wellington: Lux Verbi. [ Links ]

Landman, C. 1994. The piety of Afrikaans women. Pretoria: Unisa Press. [ Links ]

McClintock, A. 1993. Family feuds: gender, Nationalism and the family. Feminist Review 44:61-80. [ Links ]

Mulvey, L. 1984. Visual pleasure and narrative cinema, in Art after modernism, edited by B Wallis. New York: [Sn]:361-373. (Reprinted from Screen, 16(3)6-18). [ Links ]

Murray, M. (2016). Law of the Father., in The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies, edited by A. Wong, M. Wickramasinghe, R. Hoogland & NA Naples. [O]. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118663219.wbegss446 [ Links ]

NIV Bible / New International Version. [O]. Available: https://www.bible.com/versions/111-niv-new-international-version. Accessed on 20 October 2022. [ Links ]

Parker, R. 1984. The subversive stitch: embroidery and the making of the feminine. London: The Women's Press. [ Links ]

Parker, R & Pollock, G. 1981. Old mistresses: women, art and ideology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Rademan, L. 2017. Threads of Ambivalence: Redressing selected aspects of Afrikaner female identities through art-making. Unpublished M-Tech Dissertation. University of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Schmahmann, B. 2015. Shades of discrimination: The emergence of feminist art in Apartheid South Africa. Woman's Art Journal 36(1) (Spring/Summer 2015):27-36. [ Links ]

Silkiluwasha, M. 2015. Diasporic post-colonial African children's books and the logic of abjection. Marang Journal of Language and Literature 26:123-142. [ Links ]

South African Reserve Bank. [Sa]. History of Banknotes and Coin. [O] Available: https://www.resbank.co.za/en/home/what-we-do/banknotes-and-coin/history-of-banknotes-and-coin Accessed on 26 June 2023. [ Links ]

Van der Watt, L. 2005. Art, gender ideology and Afrikaner Nationalism - a case study, in Between union and liberation: women artists in South Africa 1910-1994, edited by M Arnold & B Schmahmann. Aldershot: Ashgate:94-110. [ Links ]

Van der Watt, L. 1996. Art, gender, ideology and Afrikaner Nationalism: a history of the Voortrekker Monument tapestries. MA dissertation, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Vestergaard, M. 2001. Who's got the map? The negotiation of Afrikaner identities in post-apartheid South Africa. Daedalus 130(1):19-44. [ Links ]