Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

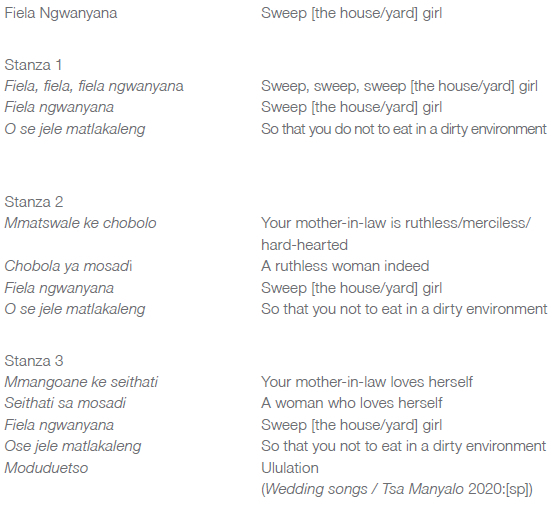

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a22

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

"Sweep the yard girl": Brooms, wifely duties and the subversive art of Usha Seejarim

Shonisani Netshia

Department of Visual Art, Faculty of Art, Design & Architecture, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. shonin@uj.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8016-0589)

ABSTRACT

Jumping over the broom in African and African-American contexts symbolises the bride's commitment to clean the house and yard of the new home she is joining-to perform service through labour. In South Africa, a popular cultural song, Fiela Ngwanyana (sweep [the yard] girl), is often sung at traditional wedding ceremonies to usher the makoti (bride) into the groom's family and is laden with meanings. Through singing, dancing, and sweeping the path clean for their new makoti, the groom's family subtly inform her of the politics of household labour to come. I focus on a specific stanza in the song and make connections between the broom, the makoti and mamazala (mother-in-law)'s relationships, and the themes of femininity and domesticity.

I argue how brooms are used as symbolic tools of othering and suppression within the marital home. I discuss how the broom - a docile, mundane, handmade object-transcends its original, functional use and becomes highly charged with meaning as a signifier of femininity, domesticity, and subservience. In order to unpack the broom's nuanced meanings, I refer to a selection of Usha Seejarim's works, in which she features brooms and transforms them into objects of transgression and reclaiming power.

Keywords: makoti (bride), mamazala (mother-in-law), Fiela Ngwanyana, traditional African wedding, domesticity.

Introduction

In this article, I explore the cultural similarities around the world1 with regard to the use and meaning of the broom. I argue that most brooms are gendered. Brooms are regarded as feminine because they have been consistently linked to women's work in most communities, particularly in a South African domestic context (Kearney 2021:545). I examine how the broom establishes a symbolic bond between a makoti (bride)2 and her mamazala (mother-in-law) through marriage and how it becomes a tool of suppression/oppression towards makotis within the South African context.

I choose to explore the relationship between makotis and their mamazalas3 as this relationship seems to have the highest risk of developing tension and discord (Gumede 2009:13; Jackson & Berg-Cross 1988:293; Krige 1936). I am a Venda makoti, and in TshiVenda, a makoti is called mazwale. My positionality allows me to provide contextual, 'insider' information on the role of makotis in South Africa as I have both experienced and observed what I discuss in this article.4 I explore the idea of home as a shifting notion and regard the traditional African wedding5as an event that escorts the 'Girl-Woman-Bride' (Mupotsa 2015a:73) into a new domestic realm with its own set of politics regarding household labour. At the traditional African wedding ceremony, the broom features as a wedding gift-a prop in the rites of passage and rituals performed-and becomes integral to the makoti's role as a wife, mother, and daughter-in-law.

I explore how the broom-a docile, mundane, handmade object found in the home- transcends its original use and becomes highly charged with meaning as a signifier of femininity, domesticity, and subservience, particularly in the relationship between the makoti and mamazala within a South African context. I use Pat Kirkham's (1996:2) theorisation of gendered objects as 'highly, though differentially, affective and amongst the strongest bearers of meaning in our society' as a springboard for my discussion of the relationship between the makoti and her mamazala. Kirkham (1996:2) states that 'relationships between objects and gender are formed and take place in ways that are so accepted as "normal" as to become "invisible"'. I explore the normalcy between women and brooms and how 'the perceived common interrelation of gender and object' is fundamental for understanding 'the cultural framework which holds together our sense of social identity' (Kirkham 1996:2). I discuss a selection of Usha Seejarim's artworks and include information I gleaned from an interview I conducted with her to formulate my association of the broom within the article's major argument.

The broom: Its description and uses as a gendered object

The Cambridge Dictionary (2022:[sp]) defines a broom as:

A brush with a long handle made of a wooden stick and long parts for sweeping made of twigs ... which is often connected with witches (meaning people, especially women, believed to have magical powers) in stories.

The broom, a cleaning tool and seemingly mundane object becomes gendered, particularly within the context of the domestic space of the home. According to Rakesh Goswami (2017:[sp]), who writes for the Hindustan Times, 'brooms have gender: those used for sweeping outdoors are masculine and called "buhara"; the ones used indoors are feminine and called "buhari" in the Indian context'. In a museum in Jodhpur, India, more than two hundred types of brooms that were used in different parts of Rajasthan have been preserved (Goswami 2017:[sp]), consequently turning the spotlight on this humblest of objects. Goswami's classification of brooms by gender is a provocative concept.

The nature and uses of grass brooms

'A grass broom is made of grass pulled out by the roots, twined and bent over before being bound to form the grip of broom,' and they continue to be made by women 'during the season when the grass is available' (Annals of the South African Museum 2022:[sp]). Charlie Shackleton, Sheona Shackleton and Bruce Campbell (2007:[sp]) describe how, in rural areas, such as in the Eastern Cape and Limpopo, grass hand-broom makers are predominantly middle-aged women from disadvantaged backgrounds with little formal education who are often their households' sole income earners. The skill to make brooms is traditionally learnt from mothers and grandmothers. Shackleton, Shackleton and Campbell (2007:[sp]) further state that broom producers in the Bushbuckridge district in the north of South Africa similarly represent the poorest households-widows and so-called "granny-headed" families whose engagement in the trade offers them a vital safety net. In other areas, such as Gauteng, brooms are sold informally at taxi ranks, outside train stations, Kwa Mai Mai traditional markets, shopping centres, spaza shops, and by omkhozi6 who walk from door to door selling brooms in townships.

According to Michelle Cocks and Anthony Dold (2004:37), the broom is symbolic of traditional Xhosa culture and connotes respect for the ancestral faith in the newlyweds' home, regardless of their religious affiliation, economic status, and geographical location. These brooms are used for sweeping the house and yard daily and are replaced when needed. In their study on the cultural importance of non-timber forest products, Cocks, López and Dold (2011:107) explore the opportunities that products, such as brooms, 'pose for bio-cultural diversity in dynamic societies' and theorise that, in South Africa, economic status (the value of housing) is significant, showing that people from lower economic groups are more likely to purchase a grass broom for cleaning purposes. Older people tend to buy brooms for cultural purposes rather than for cleaning (Cocks & Dold 2004, cited in Cocks et al. 2011).

Jumping over the broom and expectations of the bride

In the context of wedding ceremonies, Tyler Parry (2020), author of Jumping the broom: The surprising muiticuiturai origins of a Black wedding ritual, traces the tradition to the eighteenth century, when it was primarily practised by Europe's marginalised populations, such as the Romanichal Travellers and people who lived in rural Wales and Ireland. Parry (2020) adds that Europeans who had 'jumped over brooms' at their weddings brought the ritual to the United States, where it was soon adopted by another marginalised population: the enslaved people in the American South.

Dianne Stewart (2021:[sp]) states that 'while broomsticks were used in some West African ceremonies', she had attended several weddings in which Black couples 'jumped the broom', considering it a dignified African tradition that preserved rituals practised by their forefathers. She adds that while this ceremony is still celebrated today, 'the broomstick may have served to remind enslaved couples that their marriages were perpetually vulnerable to dissolution at the impulse of their owners' (Stewart 2021:[sp]). Enslaved persons had no marital rights, and married couples could be severed from their spouses at a whim, since their owners had every right to gift, loan, hire out, or sell them without warning. More than 'thirty per cent' of enslaved people had their first marriages dissolved due to the domestic slave trade after the Revolutionary War (Hunter 2017:26). Some enslaved couples adapted their wedding vows to accommodate their precarious condition, vowing to remain married until 'death or distance' parted them (Foster cited in Stewart 2021:[sp]).

Jumping over the broom in African and African-American contexts also symbolises the wife's commitment to clean the yard of her new family's home-to perform a certain kind of service through hard labour. In West Africa, this ritual is linked to the warding off of evil spirits (LaBarrie 2022 [sp]). Jumping the broom may also be associated with the expectations expressed in traditional wedding songs. In South Africa, traditional cultural practices are still significantly high, and that is why one may find that in urban areas, the popular Sesotho/Setswana song, Fiela Ngwanyana, translated as 'sweep [the house/yard] girl', is still sung at traditional wedding ceremonies to usher the makoti into the groom's family.

I argue that this song is laden with subtle domestic connotations and oppressive meanings. Traditional wedding songs, such as Fiela Ngwanyana and Umakoti Ungowethu (The bride is ours), inform the bride about the expectations of the groom's family and the duties she is bound to perform for them.

Zandile Manqele (2000:1) posits that within the Zulu culture,

... the groom's family looks at the young bride as a person who is responsible for doing all the chores in her new husband's home. While many new Zulu brides are welcomed as daughters to their husband's homes, it is not impossible that the young Zulu bride could be treated like a "Cinderella" with quasi-slave status.

Manqele elaborates that the role of song as a significant element associated with marriage rituals is not limited to the Zulu society. Such songs constitute a form of oral communication embedded with messages that convey specific values and attitudes towards brides (Manqele 2000:2).

Fiela Ngwanyana also highlights the often-complicated dynamic of the makoti and mamazala relationship that is ubiquitous within the in-law relationships among modern Black South African families. Tebogo Nganase and Wilna Bason (2019:230) state that 'when a son gets married, one of the most critical and ambivalent relationships created is known as the mother-daughter relationship' because this relationship is vital for managing the family dynamics and introduces anxiety surrounding the fear of contamination from newcomers into the family structure. Furthermore, Carolyn Prentice (2008:74) suggests that:

... what may be problematic is not that in-laws themselves are problematic, but that families live within their own routines and expect the newcomer to adjust to the family's routines not recognizing that the assimilation of a newcomer is a two-way process.

During the ceremony, the older females, i.e. sisters-in-law, aunts and gogos8 from the groom's family sing and ululate with short grass brooms or imitsanyelo (brooms in IsiZulu) (see Figure 1), dancing and sweeping the path clean for their new makoti, subtly informing her of their expectations of her regarding household labour, and prompting alarm bells about married life's dilemmas (Levine 2005:42). I argue that all the warnings are immaterial because in most cases, once the lobola9 negotiations have taken place, the marriage is recognised as a marriage according to customary law (Shope 2006:64). Laura Levine (2005:107) posits that 'music is equally central to the African wedding', referring to the wedding as 'another rite of passage that changes a person's status'. This view is particularly true for the bride. Levine (2005:42) adds that 'there is an abundance of songs which carry symbolic significance performed at weddings,' which communicate emotive messages to the bride, making 'reference to the bride's domestic role and responsibilities in her new home' (2005:107). Interestingly, the makoti's very own aunties and gogos sing along, knowing full well what lies ahead because they, too, have had to endure the very 'abuse' they usher her into.

Cocks and Dold (2004:35) state that one of the three most common cultural uses of grass brooms reported in the Nelson Mandela metropole (I contend these practices are similar amongst most South African Black households), is as a traditional wedding gift to a makoti. Cocks et al (2011: 117) explain that a collection of approximately ten grass hand brooms are handed over to a daughter by her mother a few weeks after the 'white wedding' ceremony.10 They add that the traditional ceremonial presentation of the brooms called 'ukutyiswa amasi (literally to present a gift of sour milk)' is crucial and performed to formally welcome a new bride into the family (Cocks & Dold 2004:37; Hunter 1936, cited in Cocks et al 2011:117). This ceremonial presentation clearly highlights the mother's awareness of the 'hard work' called ukukotiza11 that lies ahead for her daughter (Manqele 2000:8).

David Semenya (2014:3) elucidates that when a bride is accompanied to her new husband's home, she is presented with utensils that she will use in her husband's home. These utensils are 'a traditional broom, blankets, a basin, a dish, and spoons' (I attended a traditional ceremony in Venda that welcomed the bride into the groom's home, during which the bride was given pots). These utensils help the bride transition into her in-laws' home because she might not know where to find these items to accomplish the tasks expected of her, including rising in the early morning hours to sweep the house and yard. Semenya (2014:3) posits that should the makoti not have her own broom, 'the in-laws may even intentionally hide their broom'. If she cannot find the broom, she may not wake anyone to find out where it is kept-such a practice is a lesson she must learn as she adjusts to married life.

Certain tasks the new makoti is expected to perform are subtly embedded in the song, Fieia Nywanyana, that prescribes her behaviour-such as respect/kuhionipha,12which is associated with custom (Manqele 2000:16). Sanelisiwe Nkonyane (2020:13) explains that 'for a woman to be of value within Swazi society, she has to be taught forms of respectable behaviour referred to as kuhlonipha'. However, Nkonyane (2020:13) argues that 'kuhlonipha perpetuates gender inequality'. This practice becomes immediately visible during traditional wedding ceremonies, in which most of the marriage conventions focus predominantly on the role of the bride. According to Manqele (2000:27), 'a bride is expected to do away with some of the practices she used to do before marriage' such as clubbing and going to parties. A young bride must also forsake her unmarried friends because they are often viewed as a bad influence. In order to maintain a respectful status, a bride must clean the house, cook for her in-laws, 'bear children and also bring them up in an orderly way' (2000:27). Prior to the traditional African wedding ceremony, the elderly women in the makoti's family offer her counsel or ukuyala13 and convince her to bekezela, which means to persevere. The phrase used is kuyabekezelwa emshadweni, loosely translated as 'to have a persevering spirit in marriage'. The makoti's mother and aunts act as living examples and, having been oppressed for years, will become, despite their declarations to the opposite, tyrants towards their own daughters-in-law. This practice is a vicious cycle.

Recently I have observed that there has been an increase of young makotis who are fully aware of their human rights, educated and employed but ignorant of what lies ahead of them. They, as I was, are shocked when expected to perform domestic chores such as cooking outside on an open fire with large drie foot pots14 during family gatherings and rising very early in the morning to sweep both the interior of the house and the entire yard, using the grass broom that was waved in the air in the traditional African wedding celebration during the singing of Fiela Ngwanyana, rather than a modern one that she has been accustomed to using in her own home. Unknowingly and perhaps out of the joy of finally being accepted into her husband's family, she joined in the singing of Fiela Ngwanyana, thus committing herself to lifelong subjection. I suggest that when this situation happens, common sense becomes overwhelmed by the liminality of the traditional African wedding ceremony as ritual, wherein, as Danai Mupotsa (2015b:187) proposes, 'the girl and the bride as related in becoming-bride, are the site of intense sociocultural [and traditional] investment and anxiety'. Mupotsa (2015b:187) explains 'that traditional marriage rites are problematic for women and undermine their status within marriage'. This practice often produces a complex dilemma for contemporary African women who, through marriage, are caught in a balancing act between their notions of the modern and the traditional worlds.

After providing the context of brooms, a brief history and tradition of 'jumping over the broom' and an introduction to Fiela Ngwanyana, I now explore the idea of home as a shifting notion (Kokoli & Sliwinska 2018) and regard the traditional wedding as an event that escorts the 'Girl-Woman-Bride', referring to the transformations of the bride (Mupotsa 2015a:73) into a new domestic realm, with its set of politics around household labour. The traditional wedding ceremony presents the imagined dream of a perfect marriage and the domestic fantasy of family life (Kokoli & Sliwinska, 2018). It is noticeable that the traditional African wedding ceremony is often void of any reference to the global white wedding or jumping over the broom. Instead, becoming a bride in a South African context, as Chrys Ingraham (in Mupotsa 2015a) suggests, is not simply a range of lessons in femininity but rather powerful lessons about gender that reinforce the notion that in the Black South African context, what counts as beautiful and marriageable material is actually hard labour. The traditional African wedding ceremony can be seen as a practice related to the broader social or public sphere concerned with the respectable image of the Black family that stresses the bride's responsibility to build her home-referencing Christian ideology-that instructs and encourages a woman to be 'wise' and to build her home unlike the 'foolish' woman who is said to tear it down 'with her own hands' (Proverbs 14:1).

In stanza 2 of Fiela Ngwanyana, the song delivers an unsettling message to the makoti, that I argue is overlooked and normalised. It exposes the injustices that most makotis endure at their mother-in-law's hands. 'Mmatswale ke chobolo, Chobolo ya mosadi', (Your mother-in-law is ruthless/merciless/hard-hearted, A ruthless woman indeed), which is a covert message informing the makoti of her mother-in-law's demanding nature, and confirming she must perform her household duties enthusiastically in order to be deemed worthy to be part of the family and constantly prove she is indeed the 'right' wife for her mother-in-law's son. The makoti is instructed to obey, submit to, and do everything possible to please her husband. She is expected to wash his clothes (and those of visitors), cook and serve her husband, and not question his demands or whereabouts for her marriage to survive, just as her mother and mother-in-law have done. A new makoti is not expected to voice her opinions but to continue the tradition of 'sweeping the family secrets under the rug' to gain favour with all her husband's family members. What lies ahead for her contradicts her notions about the white wedding, which, in most cases, takes place the day, week, or month after the traditional African wedding ceremony. It also contradicts the ideas she has always held about marriage. Mupotsa (2015b) theorises that the 'fairytale' genre of the white wedding is intended for little girls who are told that this transformation is a future aspiration. Catherine Driscoll (in Mupotsa 2015a:73) states that 'girls are central to the construction of the wedding ritual since the figure of the bride is predominantly constructed and immature and/or incomplete construction in which the bride functions as a mode of feminine development'.

My interest in how brooms become symbolic tools of 'othering' and suppression within the marital home is fuelled by the subversive domesticities that become prevalent in marriage. This perspective is based on the dichotomy between the mother-in-law and makoti and the emotional and physical abuse that a makoti may suffer at the hands of her mother-in-law. By 'physical abuse,' I am referring to the physical pain and long-term adverse effects on one's body of having to bend over and sweep large areas using a grass broom. Another example of this type of abuse is the makoti repeatedly having to clean the floor on her knees for an extended period, which may lead to musculoskeletal disorders (MDS), instead of allowing her to use a mop. This abuse increases if the makoti has sisters-in-law who expect her to complete most of the household chores alone, as instructed or supported by their mother-similar to practices described in the fairy tale Cinderella. The makoti assumes the role of a 'quasi-slave' as suggested by Manqele (2000:1).

A selection of Usha Seejarim's artworks that feature brooms

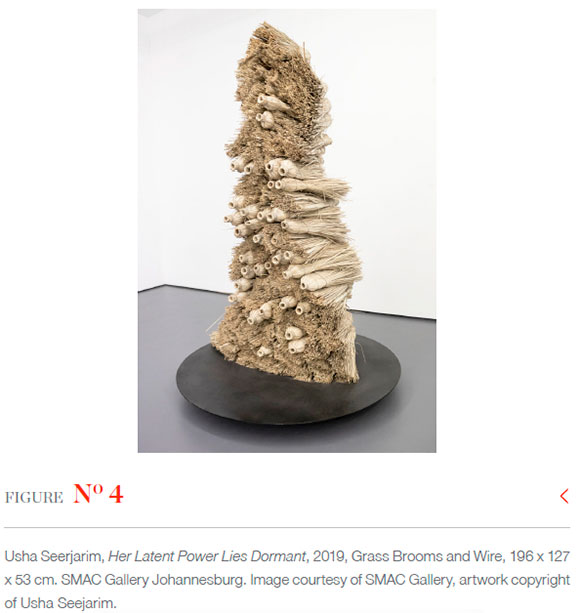

In exploring how the broom can transcend its original function and become a signifier of femininity, domesticity, and subservience, I set up a dialogue engaging the artworks of contemporary South African artist Usha Seejarim, in which she transforms grass brooms into objects of transgression and power. In her works, domesticity and femininity are explored within the broader sphere of defiance, wherein the broom becomes a tool of resistance, 'forcing us to interrogate our gendered relationship with domestic labour' (Moloi 2019:[sp]).

Transgressing Power (2019) comprises three evolving bodies of work by Seejarim in which utility takes on fascinating and nuanced qualities. In these works, Seejarim transforms domestic, mundane, and 'seemingly impartial and unemotional' broom heads, broomsticks, pegs, and irons into what Alexandra Dodd (2019:2) describes as 'a mysterious material language of wit, force, sensuousness and defiance'. Seejarim gives these household objects a voice. She disrupts the normative materiality of these domestic objects by transforming them into compelling sculptures with defiant and loud voices, thus disturbing the viewer's relationship with them.

She states that her preoccupation with the everyday comes from her 'search for the value of what lies behind and beyond that which is ordinary' (Seejarim 2023). I suggest that her narrative expression of domestic experience legitimises the process of storytelling through her artistic interventions that then record and visually manifest a host of laudable untold experiences (Moloi 2019).

Alison Kearney (2021:540) suggests that Seejarim's artworks 'question interpretations of the everyday and challenge gendered and racialized identity constructions in contemporary South Africa'. Kearney (2021:541) speculates that the 'everyday' is elusive-it is characterised by repetition, boredom, and mundanity and yet, because everyone experiences it differently, its exact nature is difficult to define. This is made more difficult in the context of a makoti who now has full access to the most intimate spaces of her in-laws' home. From being an outsider before the wedding, she is now privy to all areas of the house and is responsible for cleaning it every day as 'a dutiful, subservient and obedient wife' (Malan 1997:275). In Clean Sweep (2013) (see Figure 2), Seejarim cut up the bristles of brooms and, using tweezers and glue, created a drawing of herself crouching down and sweeping the floor using a short grass broom. She explains that she is attracted to laborious processes (Seejarim 2023). My interpretation of Clean Sweep is that it accurately represents how a makoti would sweep using a short grass broom to clean large areas.

In 2016, Seejarim was invited to produce a forty-second video, Sweep (2016), which was projected on the ABSA building at a time that coincided with the Joburg Art Fair. Seejarim (2023) acknowledges that 'household chores are about physical labour which is equivalent to the labour required for stop frame animation'. Sweep is a hand-drawn animation of her sweeping and Seejarim (2023) elaborates that the narrative is simple; she wanted a horizontal landscape where she entered and exited the frame sweeping leaves. She extracted still shots from the video and redrew each frame. The timing of the video's presentation was interesting because, coincidentally, it was screened during an ongoing municipal strike of two weeks, and thus, the city streets were filthy, so her video was her way of 'cleaning the city' (Seejarim 2023).

In the sculpture, Triangle (2012), Seejarim assembled used plastic brooms with handles that have their own history, 'complete with dust, lint, and frayed bristles,' which, as Kearney (2021:545) highlights, in a South African context, invoke the relationship between employers and their domestic helpers, since it is the latter who are most likely to use the brooms.

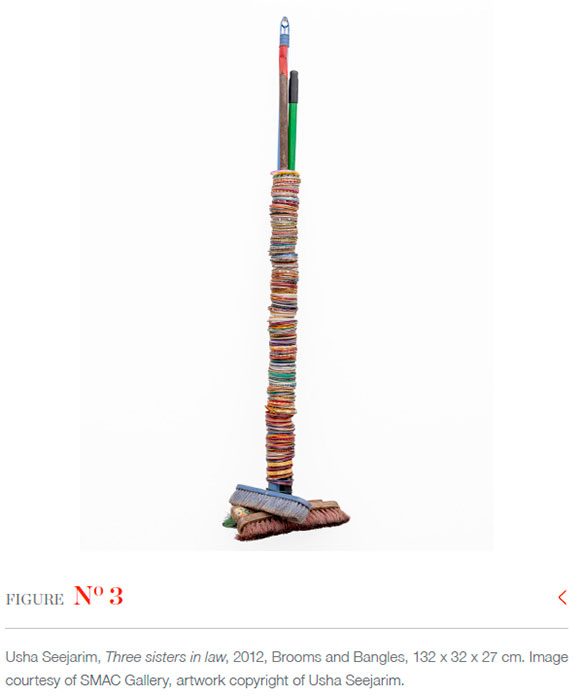

Brenda Schmahmann's (2021) writing on Seejarim's series, Venus at Home (2012), and how it alludes to the domestic sphere as a potential site for oppression and conflict, is important to my argument in this article. According to Schmahmann, in Three Sisters in Law (2012) (see Figure 3), the sticks/handles of three conjoined brooms are surrounded by some bangles the artist had begun collecting before the Venus at Home initiative. In an interview with Schmahmann (2012:78), Seejarim explained that:

... a Hindu woman receives a set of red glass bangles when she marries, and these items are considered symbolic of the marriage. But rather than being allowed to wear them, the idea is that the recipient will break them when she is widowed.

The bangles in Three Sisters in Law do not merely link the three women whom the brooms are intended to represent, but are used to symbolically tie them together through a forced, suffocating, and constricted connection fuelled by rivalry (Schmahmann 2012; Seejarim 2023). Seejarim (2023) elaborates that the bangles are different-some are red plastic bangles that can be found in Fordsburg, 'they may be just plain red, or have beads or gold trimmings'. In Three Sisters in Law, Seejarim did not use these red bangles, but used decorative bangles donated by people in her community. Seejarim (2023) states that at the time, she was working with brooms, mops, and irons for her body of work, Venus at Home, and 'against the wall were some brooms, and next to them was the box of bangles, and she grouped three brooms together and started throwing bangles in with help from her four-year-old daughter' (Seejarim 2023). Once they were finished, she stood back and said, 'This is a work' (Seejarim 2023). Seejarim (cited by Schmahmann 2012:78) explains that this work is not a reflection of her own reality because she never lived with her mother-in-law and has a good relationship with her sisters-in-law, but that she was rather referencing 'a conservative family structure where parents, their sons, and daughters-in-laws all live together and where there is often family politics'. Seejarim (in Schmahmann 2012:78) further emphasises:

This relationship is one in which three women, three sisters-in-laws, are sisters by marriage, not by blood. They are in this relationship and it is a constricting one and it is a domestic one. It is [centred] around this domesticity of keeping house, of keeping family, of keeping your husband happy, of keeping your father-in-law and your mother-in-law happy.

The notions of constraint and constriction underpinning Three Sisters in Law are starkly similar to what the Black makoti experiences with her in-laws. She and her other sisters-in-law are constantly reminded that 'blood is thicker than water'.

In my interview with Seejarim (2023), she indicated she was unfamiliar with the song Fiela Ngwanyana. I explained that I believed that this song has negative undertones that suggest that brooms are used to subject brides to abuse. While initially surprised, she agreed that the representation in Three Sisters in Law, as well as the experiences of some Indian brides, are similar to the practices that some Black South African brides encounter in marriage (Seejarim 2023). She explained that her knowledge of Indian brides' experiences comes from observing her mother's and aunts' lives. Seejarim's mother was widowed at a very young age, and she lived with her in-laws because she had no other option. Seejarim was four when her father died, and as a child, she saw how her mother was treated, 'not just by her parents-in-law, not just her mamazala, but even by her sisters-in-law, and [her] uncles - her brothers-in-law' (Seejarim 2023). We both agreed that there must be some wives/widows who are happy, but there are many who are not.

Building on the premise theorised by Schmahmann's in her writing and her interview with the artist that focused on Transgressing Power, Seejarim utilises the grass brooms used in traditional African wedding ceremonies, which I believe are employed as tools of oppression towards the makoti. Nkgopoleng Moloi (2019:[sp]) describes such oppression as 'domestic labour as punishment'. Moloi (2019:[sp]) explains that the title, 'Transgressing Power, can be read through multiple layers'. One of these 'layers' is that Seejarim's practice itself is transgressing, as it pushes the boundaries of the materials into places where they might not otherwise go, allowing viewers to engage with the materiality of the brooms and pegs, and so, potentially 'interrogate gendered relationships linked with domestic objects' (Moloi 2019:[sp]).

Brooms and witchcraft

I cannot overlook the association of brooms with witchcraft and ceremonial magic. Francisco Goya loathed superstition and often depicted images with witches. As part of eighty aquatint etchings in his Los Caprichos (The Caprices) series (17971798, published in 1799), Goya included an image, Capricho Plate No. 68: Linda Maestra! (Pretty Teacher!) (Philadelphia Museum of Art 2022:[sp]) in which he illustrated a scene of a wrinkled, old witch recruiting a young woman into her rituals. In the top right-hand corner of the print is an owl that appears to be escorting the naked woman (Philadelphia Museum of Art 2022:[sp]). In some Black South African contexts, the owl and broom are also synonymous with witchcraft. Goya describes the body of his Los Caprichos prints as depicting 'the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society, and from the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance or self-interest have made usual' (Philadelphia Museum of Art 2022:[sp]).

Dodd (2019:3) states that Seejarim's 'broom heads, broomsticks and the totemic presence of a mysterious straw figure conjure the idea of the witch'. According to Dodd (2019:3), the words 'witch' and 'whore' are typically used to control and humiliate women into 'socially accepted behaviour'. She adds that women tend to be called witches when they transgress power, while those who contravene accepted sexual practices are often called whores (2019:3). Similarly, a makoti who transgresses the power of her mother-in-law and refuses to submit to the oppressive 'laws' of her new family by waking up late, speaking out, not living with or visiting her in-laws, is easily referred to as a witch. She is quickly labelled as the one who has poisoned or bewitched their son15 into doing everything she says, including not sending through monthly instalments of 'black tax',16 a phenomenon which Niq Mhlongo (2019:[sp]) explains is 'a secret torment for some and a proud responsibility for others'.

The link between the broom and witch further permeates through the titles of Seejarim's work, such as Her Latent Power Lies Dormant (2019) (see Figure 4) and She Sleeps Naked (2018) (see Figure 5), which impress upon the viewer ideas around danger, force, flight, and burning. Seejarim references a line from the poem entitled The Witch (2011) by American poet Elizabeth Willis in her work, She Sleeps Naked (Dodd 2019:3). It is an installation of ten brooms of different sizes hanging in an upright angle against white walls. This installation invokes the levitation witches are supposed to achieve experience when flying off.

In relation to the second stanza of Fiela Ngwanyana, I suggest that the broom can be interpreted as representing the mother-in-law as an 'oppressor' and/or a 'witch' who does not accept her son's wife and uses the broom to silence and abuse the makoti. Perhaps it also symbolises a mother-in-law's power to warn her daughter-in-law not to attempt witchcraft or contaminate the homestead.

Conclusion

In this article, I have attempted to show how, in the South African context of the traditional African wedding ceremony and into the marriage, the broom has and can be used as a tool to oppress the makoti. I compared the discussion of Usha Seejarim's artworks, which challenge stereotypical constructions of femininity, to the embedded oppressive themes in Fieia Ngwanyana and the cultural similarities around the world with regard to the broom's use and meaning. Intriguingly, while a makoti is treated as a princess-becoming-queen or Cinderella on her traditional African wedding day, this adulation ends almost instantly when she takes up her new role as a quasi-slave to her in-laws, as Cinderella did to her step-mother and step-sisters. The irony in the makoti's tale is that there may not be a 'happily ever after' unless she can respectfully address the issues with her husband or mamazaia.

Notes

1 By referencing different cultural groups whose practices display similarities, I advocate that African culture is not monolithic.

2 Makoti refers to a bride in Sesotho, Setswana, Xhosa, and Zulu cultures in South Africa. I use the terms makoti and bride interchangeably throughout this article.

3 I acknowledge that I should be referring to a bride as umakoti (singular) and abomakoti/omakoti (plural) or Umamazaia (singular)/Abomamezaia/abomamazaia/omamezaia (plural) with respect to the Nguni language and culture. However in this article I use the terms makotis and mamazaias in their hybrid forms and not as a sign of disrespect.

4 I am aware that my position as a Venda makoti is unique to me and the experiences of other makotis may not be the same as mine. Therefore, I do not by any means attempt to speak on behalf of all makotis nor totalise the experience of makotis.

5 By traditional African wedding I refer to the ceremony which includes traditional practices which in present day South Africa can be varied because of multi ethnic groupings (Lewis 2018:93). The traditional wedding ceremony can take place before or after the 'white wedding', after the ioboia which symbolises the joining of two families. The traditional wedding is often marked by the exchange of gifts such as blankets and grass mats, as well as the slaughtering of a cow to inform the ancestors (amdiozi) of the new makoti joining the family (Gumede 2009:79).

6 Omkhozi female hawkers sell brooms, mops, amabontshisi or izindumba (a variety of beans), mielies or corn, and umorogo o womisiwe (dried spinach) in townships like Naledi Ext. 2 where I grew up in Soweto. When they walk past, they alert the neighbourhood that they are in the vicinity by shouting Mkhozi! Umbiial' (Mielie cob/corn). Often my mother would hear the Umkhozi's call and she would send me to run outside to purchase what she needed. Nowadays, omkhozi are no longer as visible as they used to be. Instead, young men with trolleys use a horn to alert the neighbourhood of the fresh produce they are selling. Some men sell only brooms and mops. Umkhozi in Nguni languages also means "in-law".

7 The song Umakoti Ungowethu is also sung at traditional wedding ceremonies by the bridegroom's family as a song to welcome the bride into the family. Loosely translated Umakoti Ungowethu means the bride belongs to the groom's family. Umakoti ungowethu (the bride is ours), Siyavuma (we agree), Ungowethu ngempela (she is truly ours), Uzosiwashel'asiphekele (she will do washing and cook for us), Sithi helele helele siyavuma (yes, we cherish we cherish with pride). It has gone through various modifications depending on what the groom's family and guests wish to add, such as Asimufuni emapartini (we don't want to see her at parties) and Angawahambi amahotela (She must not go to hotels) (Manqele 2000:12). Like Fiela Ngwanyana, it has negative underlying messages. I have focused on Fiela Ngwanyana as it relates closest to my exploration of the broom.

8 Gogos are the grandmothers and elderly females in the family.

9 Lobola is the bride price usually associated with Nguni languages. In the past, lobola used to be paid in the form of cattle, whereas these days money is accepted. According to Semenya (2014:1-2), lobola is an African custom that serves as proof that the marriage is recognised officially and is accepted by both the immediate families of the bride and groom, as well as the wider community. Semenya (2014:1) adds that nowadays lobola is closely associated with education. An educated woman's lobola is likely to be valued higher, in contrast to an uneducated woman (2014:2).

10 Natasha Erlank (2014:33) explains that 'when black South Africans converted to Christianity, a process beginning in the early nineteenth century ... they adopted many of the rites associated with Christianity, including the Christian wedding'. She adds that the 'the church ceremony commonly involved a white gown for women.' Hence it is called the 'white wedding'. (See Comaroff & Comaroff 1997; Schapera 1940).

11 Ukukotiza is defined as the household duties a bride is expected to perform in her in-laws' home.

12 Kuhlonipha means 'to respect'. A makoti is expected to respect her husband and all members of his family, take care of her in-laws 'offering emotional, physical and financial support' and not display any sign of disrespect (Manqele 2000:15; Nganase & Bason 2019:233).

13 In SeSotho, ukuyala is called 'go laya' (Semenya 2014:6).

14 Also known as three-legged cast iron pots, which are used mainly for outdoor cooking on an open fire.

15 The mamazala uses the term 'udlisiwe,' meaning her son's food was poisoned by the makoti in order to control him.

16 According to Tonya Russell (2023:[O]), Black tax is a South African term, which refers to 'the financial burden borne by Black people who have achieved a level of success and who provide support to less financially secure family members'.

References

Annals of the South African Museum = Annale van die Suid-Afrikaanse Museum. Natural History. 2022 [O]. Available: https://www.alamy.com/annals-of-the-south-african-museum-=-annale-van-die-suid-afrikaanse-museum-natural-history. (Accessed 18 October 2022). [ Links ]

Cambridge Dictionary. 2022 [O]. Broom. Available: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/broom. (Accessed 27 October 2022). [ Links ]

Cocks, ML & Dold, AP. 2004. A new broom sweeps clean: the economic and cultural value of grass brooms in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods 14(1):33-42. DOI: 10.1080/14728028.2004.9752477 [ Links ]

Cocks, ML, López, C & Dold, T. 2011. Cultural importance of non-timber forest products: Opportunities they pose for bio-cultural diversity in dynamic societies, in Non-timber forest products in the global context, edited by S Shackleton, C Shackleton & P Shanley. Berlin: Springer:107-128. [ Links ]

Cocks, ML & Moller, V. 2002. Use of indigenous and indigenised medicines to enhance personal well-being: A South African case study. Social Science and Medicine 54(3):387-97. [ Links ]

Comaroff, JL & Comaroff, J. 1997. Of revelation and revolution: The dialectics of modernity on a South African frontier. Chicago,IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Dodd. A. 2019. Usha Seejarim: Transgressing Power. [O]. Available: https://www.smacgallery.com/exhibitions-archive-3/transgressing-power. Accessed: 24 August 2023. [ Links ]

Erlank, N. 2014. The white wedding: Affect and economy in South Africa in the early twentieth century. African Studies Review 57(2):29-50. [ Links ]

Goswami, R. 2017. At Rajasthan museum, brooms have gender. Hindustan Times. [O]. Available: https://www.hindustantimes.com/jaipur/at-rajasthan-museum-brooms-have-gender/story-Dw4CWKk6V2T76Go9aVibiL.html. (Accessed 2 November 2022). [ Links ]

Gumede, A.M. 2009. Izigiyo as performed by Zulu women in the KwaQwabe community in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. MA Dissertation, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal. [ Links ]

Hunter, TW. 2017. Bound in wedlock: Slave and free Black marriage in the nineteenth century. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Jackson, J & Berg-Cross, L. 1988. Extending the extended family: The mother-in-law and Daughter-in-law relationship of Black women. Family Relations 37(3):293-297. [ Links ]

Kearney. A. 2021. Beyond the everyday. Third Text 35(5):540-553. [ Links ]

Kirkham, P. 1996. The gendered object. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Kokoli, A. 2016. The feminist uncanny in theory and practice. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Kokoli, A & Sliwinska, B. 2018. Home Strike. An exhibition guest-curated by Alexandra Kokoli and Basia Sliwinska, with CANAN, Paula Chambers, Malgorzata Markiewicz and Su Richardson, l'etrangere, 8 March-21 April 2018. [ Links ]

Kovacs, T & Nonoa, KG (eds). 2018. Post-dramatic theater as transcultural theater: a transdisciplinary approach. (Vol. 51). Tubingen: Fool Francke Attempto Verlag. [ Links ]

Krige, E. 1936. Changing conditions in marital relations and parental duties among urbanized natives. Africa 9(1):1-23. [ Links ]

LaBarrie. A. 2022. Broom: A wedding planner helps explain the origins and modern-day practices of this tradition. [O]. Available: https://www.brides.com/jumping-the-broom-5071336 Accessed: 24 August 2023. [ Links ]

Levine, L. 2005. The Drum Cafe's traditional South African music. Johannesburg: Jacanda Media. [ Links ]

Lewis, J. 2018. Warping: (re)conceptualising contemporary wedding rituals as an immersive theatre experience in South Africa, in Post-dramatic theater as transcultural theater: a transdisciplinary approach. (Vol. 51), edited by T Kovacs & KG Nonoa. Tubingen: Fool Francke Attempto Verlag:93-116. [ Links ]

Manqele, Z. 2000. Zulu marriage values and attitudes revealed in song: an oral-style analysis of Umakoti Ungowethu as performed in the Mnambithi region at KwaHlathi. MA Dissertation, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal. Durban. [ Links ]

Mhlongo, N. 2019. Black Tax: Burden or Ubuntu? Johannesburg & Cape Town: Jonathan Ball Publishers. [ Links ]

Moloi. N. 2019. Banal and Celestial: Usha Seejarim's 'Transgressing Power'. Exhibition review. [O]. Available: https://artthrob.co.za/2019/06/26/banal-and-celestial-usha-seejarims-transgressing-power/ (Accessed 10 March 2022). [ Links ]

Mupotsa, DS. 2015a. Becoming Girl-Woman-Bride. Girlhood Studies 8(3):73-87. [ Links ]

Mupotsa, DS. 2015b. The promise of happiness: desire, attachment and freedom in post/ apartheid South Africa. Critical Arts 29(2):183-198. [ Links ]

Nkonyane, S. 2020. Interrogating the notion of ownership of the female body: embodiment and self-representation in my artistic practice and selected works by Nandipha Mntambo. MA Dissertation, University of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Nganase, TR & Bason, WJ. 2019. Makoti and Mamazala: dynamics of the relationship between mothers- and daughters-in-law within a South African context. South African Journal of Psychology, 49(2):229-240. [ Links ]

Parry, TD. 2020. Jumping the broom: The surprising multicultural origins of a Black wedding ritual. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. [ Links ]

Philadelphia Museum of Art. 2022. Pretty Teacher! (Linda Maestra!). [O]. Available: https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/214962. Accessed 15 October 2022. [ Links ]

Proverbs 14:1. Holy Bible. New International Version. [O]. Available: https://www.biblica.com/bible/. (Accessed 3 November 2022). [ Links ]

Prentice, MC. 2008. The assimilation of in-laws: The impact of newcomers on the communication routines of families. Journal of Applied Communication Research 36(1):74-97. [ Links ]

Russell. T. 2023. Black Tax. [O]. Available: https://www.investopedia.com/the-black-tax-5324177#. (Accessed 4 February 2023). [ Links ]

Shackleton, S, Shackleton, C & Shanley, P (eds). 2011. Non-timber forest products in the global context. Berlin: Springer [ Links ]

Schmahmann, B (ed). 2021. Iconic Works of Art by Feminists and Gender Activists: Mistress-Pieces. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Schmahmann, B. 2021. Household matters: Usha Seejarim's Venus at Home (2012) and the politics of women's work, in Iconic Works of Art by Feminists and Gender Activists: Mistress-Pieces, edited by B Schmahmann. New York, NY: Routledge:68-83. [ Links ]

Seejarim, U, artist, 2023. Interview by author. [Transcript]. 20 January 2023. Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Semenya, DK. 2014. The practical guidelines on the impact of mahadi [bride price] on the young Basotho couples prior to marriage. Theological Studies 70(3). DOI: 10.4102/hts.v70i3.1362 [ Links ]

Shackleton, S & Campbell, BM. 2007. The traditional broom trade in Bushbuckridge, South Africa: helping poor women cope with adversity. Economic Botany 61(3):256-268. [ Links ]

Shope, JH. 2006. 'Lobola is here to stay': rural black women and the contradictory meanings of lobola in post-apartheid South Africa. Agenda 20(68):64-72. [ Links ]

Stewart, DM. 2021. The wedding tradition of jumping the broom didn't actually derive from Africa. [O]. Available: https://www.oprahdaily.com/life/relationships-love/a35992704/jumping-the-broom-wedding-tradition-history-origins/. Accessed 15 October 2022. [ Links ]

Wedding songs / Tsa Manyalo. 2020. [O]. Available: https://www.setswana.co.za/music/wedding_songs.html. (Accessed 15 October 2022). [ Links ]