Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a21

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The art of labour: Representations of childbirth by Reshada Crouse and Christine Dixie

Brenda Schmahmann

Professor and SARChI Chair in South African Art and Visual Culture, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. brendas@uj.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8382-2645)

ABSTRACT

Since the mid-1980s, there have been numerous instances of South African women artists representing pregnancy or making works reflecting on motherhood. A representation of the birth process itself is, however, unusual. In this article, the focus is placed on two women artists who have used this atypical subject matter. Reshada Crouse represented the birth of her first child in Danielle and Me and Danielle in 1975, returning to the theme many years later in Homo Sapien - Spiritual Animal (2021). Christine Dixie represented childbirth in a large body of art entitled Parturient Prospects, which she started in 2005 while pregnant with her second child and completed after the birth in 2006. She, too, returned to the theme later, using the matrices of her Birthing Tray works from the Parturient Prospects project to make The Harbingers in 2016 and adding varnish, colour, and cotton stitches to one of the sets of prints making up the Birthing Tray series in 2022. It is suggested that, for both artists, the theme enabled feminist responses to practices of childbirth as well as other formative moments in their lives. It is also suggested that both artists respond to discourses from the West, but in different ways. While Crouse positions her art as offering a parallel but female point of view to male 'masters' whose works have had an impact on her, Dixie suggests a commonality between early modern discourses about childbirth and those to do with the colonisation of Africa.

Keywords: Reshada Crouse, Christine Dixie, representations of childbirth, birthing tray, representations of caesarean.

Introduction

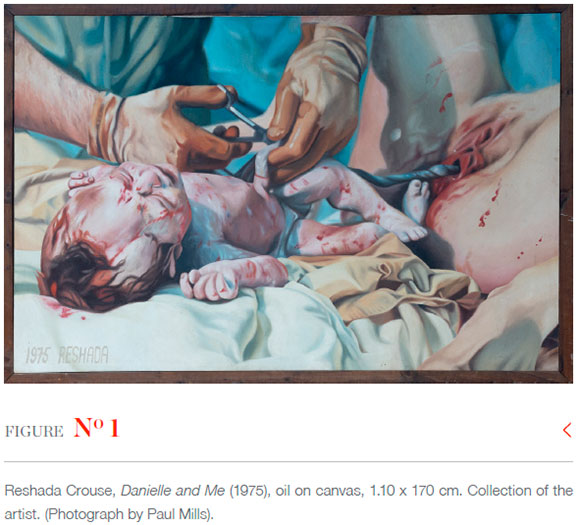

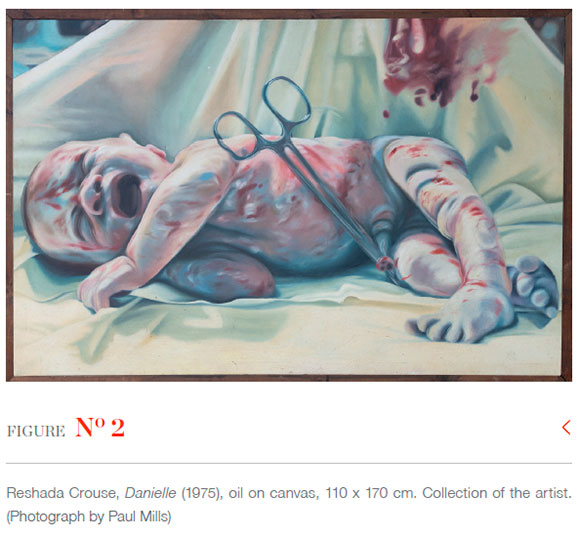

In 1975, towards the end of her fourth year of fine art studies at the University of Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal) in South Africa, Reshada Crouse (b. 1953)1 painted Danielle and Me (Figure 1) and Danielle (Figure 2), each based on a photograph of the birth of her daughter. Blunt in their representation of the bloodiness of birth and the vulnerability and cries of a newborn baby, they are the antithesis of popular representations of maternity which, influenced by a Christian tradition of Madonna and Child imagery, typically prefer a serene mother and content youngster. More than a metre high and nearly two metres wide, the scale of each painting means that the drama of birth-and the experience of the mother, who is also the artist- is writ large.

In the mid-1970s, when Crouse made these works, feminism had no notable impact on South African art. Also, given the slow pace in which journals arrived and lack of ready access to popular media and newspapers from other countries, her knowledge of precedents in the United States and United Kingdom for her representations of childbirth would have been vague at best.2 Even when she exhibited Danielle and Me and Danielle in her first solo exhibition in 1982, South African feminist art was only nascent: Penny Siopis had just begun her subversive paintings creating analogies between sweetmeats and the female body, Kim Siebert had recently started making collages which were ironical reworkings of imagery from women's magazines and Sue Williamson had just commenced her A Few South Africans-portraits of female anti-apartheid activists.3 I reveal that, even though they were made in something of a feminist vacuum, Crouse's two paintings were clearly shaped by a consciousness of a politics of gender. Indeed, they seem to have predicted the orientation towards engaging with feminist concerns that would emerge more decisively in South Africa in the 1980s.

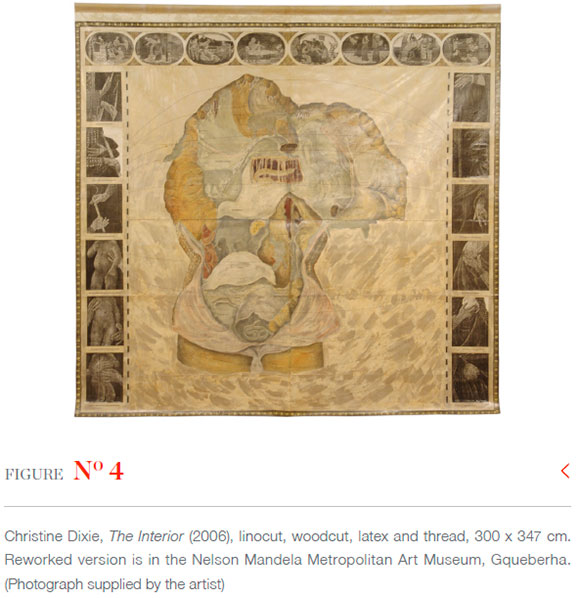

Since the mid-1980s, there have been numerous instances of South African women artists working in feminist frameworks representing pregnancy or making works reflecting on motherhood. However, a representation of the birth process itself is unusual, and I have encountered only one other South African feminist practitioner who has used this subject matter. Christine Dixie (b. 1966), who, like Crouse, undertook fine art studies to a master's level, is based in Makhanda (formerly Grahamstown) and has been a staff member in the Fine Art Department at Rhodes University since 2002.4 Often working in mixed media but best known as a printmaker, Dixie represented childbirth in works she started in 2005 while pregnant with her second child, Rosalie, and completed after her birth on March 11, 2006. Making up a large body of art entitled Parturient Prospects, this work began with a large piece called The Interior (Figure 4), followed by the Birthing Tray series (Figure 6).5

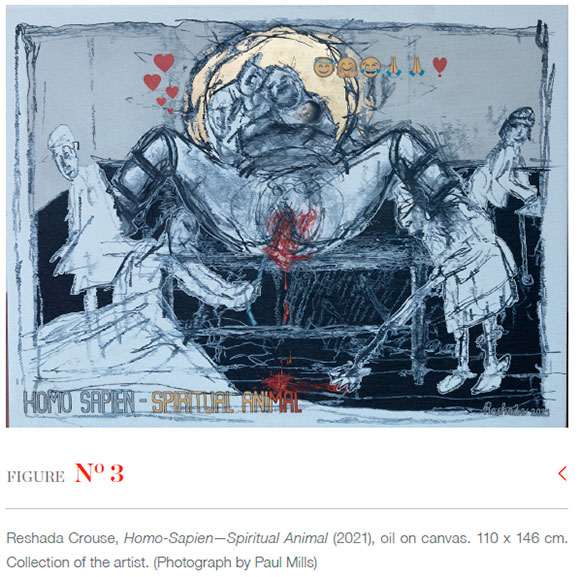

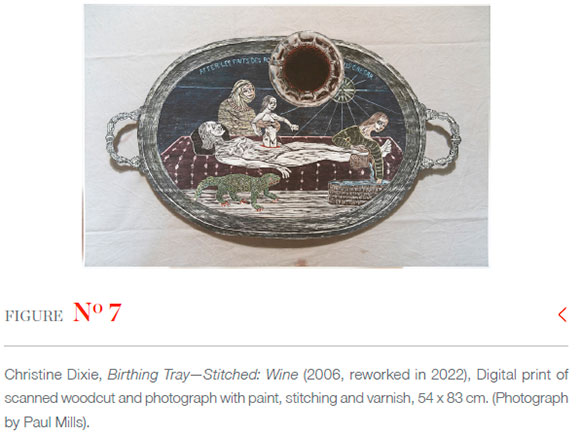

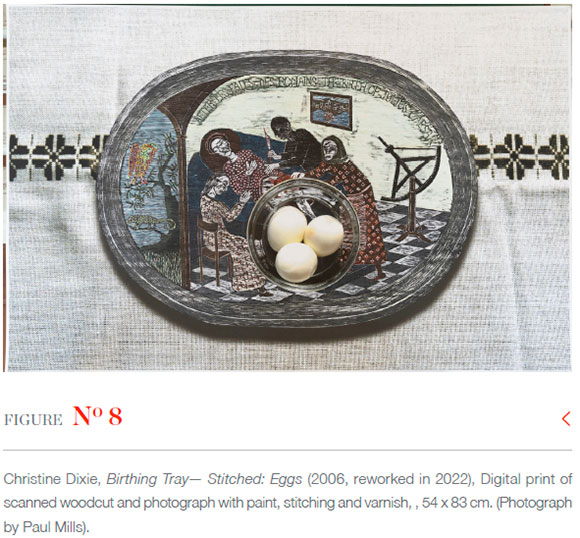

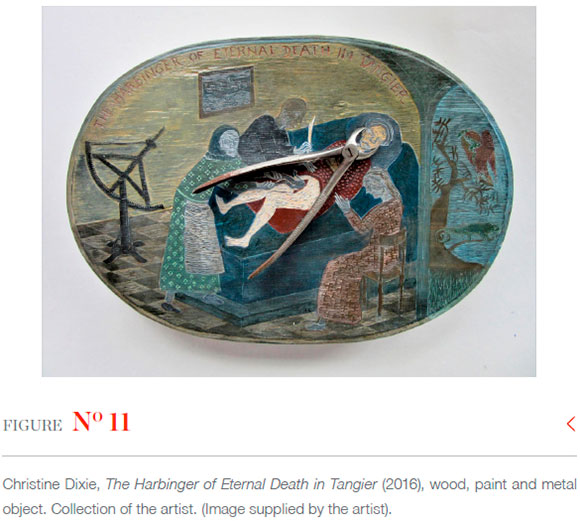

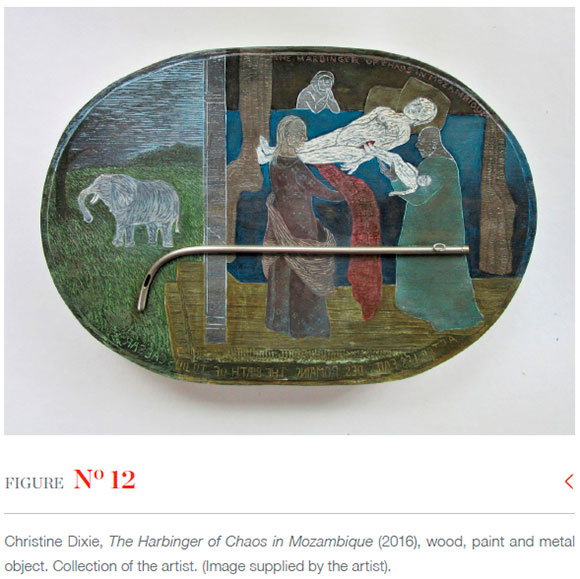

Both artists have also returned to the topic. In 2021, Crouse drew on recollections of witnessing a friend giving birth as the basis for a painting called Homo Sapien - Spiritual Animal (Figure 3) that deploys loose, expressive marks and departs from the mimetic focus that typically shapes her practice.6 Dixie likewise returned to the theme in late 2015 and 2016, reworking The Interior and reconfiguring the matrices for the woodcut prints in the Birthing Tray works as sculpted reliefs, which she named The Harbingers (Figures 10-12). Then, in 2022, she added colour, varnish, and some stitches to one print in each of the works making up the Birthing Tray series, entitling the prints constituting this version Birthing Tray - Stitched (Figures 7-9).

In this article, I reveal that, for both artists, representations of childbirth enabled feminist responses to their own experiences of giving birth and other formative moments in their lives. It is notable too that both artists respond to discourses or images from the West, but in very different ways: while Crouse positions her art as offering a parallel but female point of view to male 'masters' whose works have had an impact on her, as I indicate, Dixie suggests a commonality between early modern discourses about childbirth and those to do with the colonisation of Africa.7

Childbirth in Reshada Crouse's work

Crouse completed Danielle and Me and Danielle a mere three weeks after her daughter's delivery: the birth had, in fact, been induced to enable Crouse to make paintings of it in time for her final Bachelor of Fine Art submission.

Despite this planning, the pregnancy itself was unexpected. In an apartheid context where oppression on the grounds of race was coupled with gender prejudice,8moral censure of women's sexuality was pervasive and unmarried motherhood was considered shameful by many white middle-class South Africans. Fortunately, Crouse did not experience disapproval from her own family, her partner or her circle of friends and associates.9 Although caring for a child would be challenging for an artist wanting to embark on graduate studies, she welcomed motherhood and had no wish to give up her child for adoption or try to find a way to terminate the pregnancy.10 Indeed, she viewed Danielle's arrival as enriching her life significantly, also acknowledging that, felicitously, her daughter provided her 'with powerful and unusual subject matter' (Crouse 2021).

Crouse asked a friend, Sue, to take photographs of the birth-records that would allow the artist to reflect on her own experience. A quasi-precedent for this is a work called Childbirth (1939), which Alice Neel based on memory. Portraying a roommate in the hospital where the artist gave birth, Neel invokes a sense of the body in postpartum shock-a representation likely informed by her own experience of childbirth as much as by her perception of its impact on somebody else.11 As in Neel's Childbirth, the artist in Danielle and Me works from the perspective of both an outsider and insider, and from what is seen as well as what is felt. While the photograph necessarily distances the event, the perspective about childbirth that is presented is simultaneously that of its protagonist.

Danielle and Me represents labour-not only Crouse's own birthing of a child but also the male obstetrician cutting the umbilical cord. As with her rendition of self, the interpretation of him is metonymic: the viewer sees only the steel forceps wielded by his hands in latex gloves and a glimpse of his arm. Reiterating a tradition of representing 'the artist's studio', where the maker is almost invariably male and the model an undressed female, it simultaneously subverts this idea because of a third form of labour that is in evidence in the work-that of the process of making the painting itself. While the broad shadows and hues in the work suggest how the event was recorded by the analogue photograph that served as its source, visible flecks of paint on the canvas serve as indices of the artist's hand, attesting to her agency and vision as the work's maker.

During the 1970s, art departments at South African universities focused almost exclusively on a western art tradition, consequently shaping students' frames of reference. While this orientation influenced Crouse, she was nevertheless increasingly aware that the artists celebrated in the art history she was being taught were male-and began to think about how she, as a young female artist, might respond to this tradition. This consciousness played out in Danielle and Me and Danielle. Albeit through publications rather than seeing works themselves, Crouse was aware of Photorealism, a movement that had emerged in America in the late 1960s and became well known by the mid-1970s. Most practitioners of Photorealism were male, and Crouse says she envisaged her paintings as a feminine response to the movement: 'I saw myself as a South African female Photorealist working from photographs with this difference - choice of subject matter, one representing a female world and consciousness' (Crouse 2022/04/13). However, her focus was also historical. Crouse made the paintings less than a year after a visit to Europe during her university vacation of December 1974 - February 1975. During this trip, she had visited the Prado in Madrid and been mesmerised by Goya's Saturn Devouring His Children-a representation of the myth in which Saturn, attempting to forestall a prophecy that he will be displaced by one of his sons, consumes them soon after birth. Struck by Goya's loose brushwork, which invokes a sense of movement and dynamism, Crouse (2021:6-9) also reflected on how the work's violent narrative might be tied to fears about a loss of power on the part of its maker. In Danielle, Crouse was consciously emulating Goya's brushstrokes to show the bloodied body of the newborn child, but she was deliberately also inverting this masculinist prototype: rather than being focused on the horrific destruction of the child by the father, Danielle is an affirmation of the mother's painful ordeal to bring life to a youngster.12

Another reference to a work by a male artist might be drawn, albeit one that was probably not made consciously. Courbet's Origin of the World (1866), which shows a woman from much the same angle as Danielle and Me, was made for the private pleasure of Ottoman diplomat, Khalil Bey. Owned by psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan in 1975, when Crouse made her first paintings of childbirth, it was only later reproduced in art historical literature.13 Although Crouse may not, in fact, have known of it, Danielle and Me could be viewed as a critical inversion of Courbet's work-one that does not objectify because the woman is not just its subject matter but also its speaking subject.

Crouse's work also contrasts with Courbet's by emphasising the inchoateness of the body. Along with blood shed by the mother, Crouse's two works show the vernix caseosa14 on the child she has birthed. Bodily abjection has a long history of deployment in feminist art practice as an act of resistance, including in South Africa. Julia Kristeva, whose Power of horror: An essay on abjection was first published in French in 1980 and translated into English in 1982, defined abjection as that which 'disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite' (Kristeva 1982:4). Kristeva's concept was indebted to the anthropologist Mary Douglas who, in Purity and danger (first published in 1966), indicates how matter issuing from the margins of the body is linked to challenges to social structures: 'The mistake is to treat bodily margins in isolation from all other margins. There is no reason to assume any primacy for the individual's attitude to his own body and emotional experience, any more than for his cultural experience' (Douglas 2002:150). Although I do not want to imply that Crouse had any conscious familiarity with these theories, what Kristeva termed 'abjection'-and the link Douglas and Kristeva both made between such abjection and defiance of other kinds of 'borders, positions, rules'-helps explain why her paintings are unsettling. In revealing the inchoateness of the female body, they are, by implication, also challenging structures that control and manage women in social life.

While Crouse had experienced birth, she had only witnessed the birth of Danielle through photographs taken by her friend, Sue. The first time she found herself in the same position as Sue was in about 2000 or 2001 when she was asked to photograph another friend giving birth. Finding herself in the role of witness and photographer brought about new feelings of disturbance. She was horrified by not only the violence of birth but also how this is compounded in a medical setting and through medical intervention: 'There was this poor woman with her legs spreadeagled in a most ungainly position, a familiar one in the hospital giving "natural birth", her vagina all torn and bloodied, blood dripping onto the floor, stainless steel instruments and needles used to cut and stitch by automated robotic health-care workers' (Crouse 2021:297). Nevertheless, once the newly birthed child was handed to the mother, it was as if something happened that transcended this brute physicality. Crouse noticed that 'her husband leaned into her as they gazed in wonder at the miracle of the new human being they had created, which now lay breathing peacefully in her arms. The three had a metaphysical halo around them. They looked serene and spiritual, in total contrast to the butchered bloody vagina and the scene in the foreground' (Crouse 2021: 297).

These recollections constituted the basis for Homo Sapien - Spiritual Animal (2021), which Crouse made two decades later and four-and-a-half decades after she had painted the birth of her own daughter. Working this time in terms of a small rough preparatory drawing, which she enlarged, the sketchy style of the work invokes a sense of something recalled in imprecise detail. Not only through the positioning of the depicted female body but also the use of a palette primarily in blacks and greys, the redness of the blood shed during birth is given prominence, suggesting bodily wounding and abjection. However, by superimposing a gold halo over the couple, the artist invokes the idea of the mother, child, and father constituted as a religious-and specifically Christian-ideal. Through its inclusion of hearts, emojis of faces, and hands in prayer, the painting suggests how this idea is reiterated and reinforced through snapshots of idealised family units posted on social media.

Homo Sapien - Spiritual Animal forms part of a group of works begun in 2010, in which Crouse represents disturbing memories or dreams. A key focus in these works is on how discourses and ideas which construct the female body as a life-giving force exist simultaneously with, and are often complicated by, misogynist hatred or revulsion. The series has involved, for example, a painting in which she has interpreted her recollection of a strip club where a young pole dancer sat on a table, legs splayed, while a group of young men stared at her genitals not with desire but rather, the artist indicates, with 'a frozen look of mild horror on their faces' (Crouse 2021:283). Another work, which dates to 2016, represents rape-a grim reality in South Africa, which is reputed to have one of the highest rates of sexual violence of any country in the world.15 This concern would also seem to inform Homo Sapien - Spiritual Animal, where the bloodied vagina may not necessarily invoke only the violence of birth, but could also perhaps be read as alluding to sexual abuse. While the sketchily rendered figures wielding equipment and tying off the placenta are, in fact, performing medical roles, it is easy to mistake them for individuals enacting torture on the woman constrained and made vulnerable through stirrups. If Crouse's earlier two paintings of childbirth had represented medical intervention in such a way that they invited contemplative thought about the kinds of labour at play in representations, here, medical processes are shown in a considerably more sinister light-one that involves an unsettling slippage between assistance and violation.

Childbirth in Christine Dixie's works

In Reshada Crouse's representations of childbirth, I have indicated, an emphasis on the inchoateness of the body and, consequently, disruptions of 'borders, positions, rules'. Christine Dixie's works also disturb categories, but in her case, they do so by combining references to different kinds of discourses. This is true of The Interior (Figure 4), a three-metre-high work in rice paper covered in latex that Dixie made in 2005 when she was pregnant with her second child, Rosalie. This is also true of the Birthing Tray series, which was developed from The Interior.

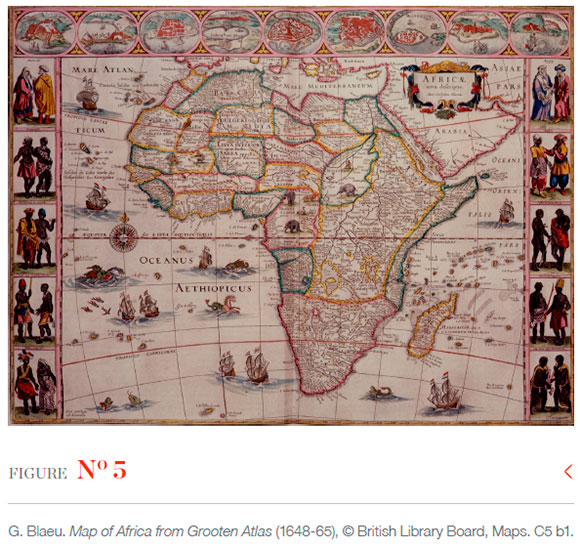

The Interior is based on a seventeenth-century map of Africa by G. Blaeu (Figure 5). Furthering the interests of the Dutch East India Company, which established an outpost at the Cape of Good Hope on the southern tip of Africa, this kind of map provided what Jerry Brotton (1997:186) terms 'a studiedly transparent image of an increasingly known world'. However, The Interior simultaneously refers to another form of scientific work during the Renaissance in the West-namely, research on women's reproductive capacities. The source in this case was De Dissectione partium corporis humani, a manual of anatomy that a Renaissance medical doctor, Charles Estienne, published in 1545.16 Through these simultaneous references to cartography and illustrations of female anatomy, Dixie refers to how journeys of expedition and discovery have historically been conceptualised as acts of male penetration into a female interior. While hitherto allusive, such discourses suggest the mysteries of Africa and women might both ultimately reveal themselves to the intrepid male explorer.

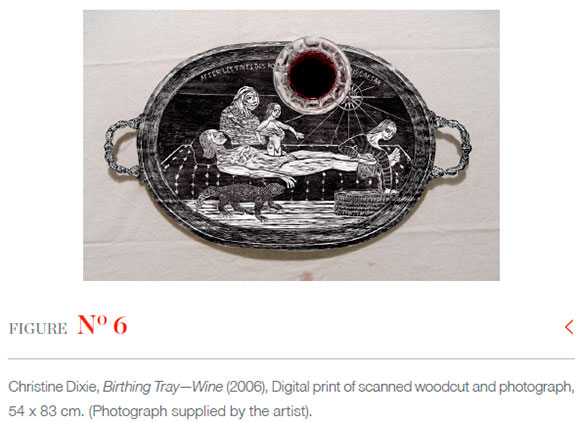

On the top row of The Interior is a series of woodcut prints that Dixie printed and collaged onto the work's surface prior to the birth of Rosalie. In the period following the birth, Dixie translated these into eight of the nine works making up her Birthing Tray series (Figure 6). However, the images were, in this instance, produced through digital photography. Each birth scene from The Interior is represented as a birth tray that supports a bowl, jug, or cup containing a foodstuff or beverage and is placed on a cloth surface.17 In the Birthing Tray - Stitched versions from 2022 (Figures 7-9), each foodstuff has been coated with varnish, and colour has been added by hand to selected details. Another feature is the strategic addition of red cotton stitches to emphasise the occasional detail.

Birth trays were popular in Italy during the Renaissance. Jacqueline Musacchio (1997; 1999), whose work Dixie read, suggests that they were used not only to serve food and drink to the new mother when she was in confinement, but also had magical properties. When acquired prior to labour, as they usually were, they seem to have been considered a potential way of ensuring that an expectant mother who spent time focusing on their representations of holy births and cherubic babies might enjoy a happy outcome of labour.18 Dixie, however, unsettles this possible historical function. The scenes in five of the works are based on images of birth by caesarean-a procedure which would generally be undertaken only when a mother undergoing childbirth had died or was on the brink of death: while there was not an expectation of the child necessarily thriving, ensuring he or she lived long enough to undergo baptism was thought crucial to the salvation of the youngster's soul. In a Renaissance context, where females were evidently seen as fundamentally passive and thus wholly susceptible to influence by any representation they happened to encounter, a pregnant woman would likely have been forbidden from exposing herself to images of caesarean birth.

Gender politics surrounding birth in Renaissance Europe affected not only birthing mothers but also those assisting them. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski (1990), whose study Dixie consulted and used as a source for several images, reveals how historical imagery of caesarean procedures was informed by an increasing marginalisation of midwives within medicine.19 During the medieval period, midwives were accorded the responsibility of deciding when a caesarean might be necessary, and they performed the procedure themselves. However, shifts in regulation during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries prohibited midwives from taking on this role: the professionalisation of surgery and medicine developed in tandem with the production of laws and writs that ensured that only men took responsibility for such procedures- even if their knowledge was no more advanced than that of midwives. As Blumenfeld-Kosinski observes, such shifts play out in representations of the birth of Julius Caesar, which were popular in illuminated manuscripts, such as illustrations of the Faits de Romains that circulated in French-speaking Europe from the late thirteenth century until the fifteenth century.

Autobiographical in that the birth of Rosalie was scheduled to be via caesarean section, as had been the case with her son Daniel in 2003, Dixie's focus in these examples also drew attention to gender dynamics that have historically informed this procedure. In fact, Dixie has used images of the birth of Julius Caesar reproduced by Blumenfeld-Kosinski as the starting point for these representations of caesarean births. One of the five works in the series-Birthing Tray - Wine (Figure 6)-is derived from a representation of the Faits de Romains from the mid-fourteenth century, when midwives still took charge of caesarean sections. It shows a single midwife lifting the child from an incision in the mother's abdomen, while a female helper prepares a bath for the youngster's baptism. The sense in the image is of purposeful competence on the part of a midwife in negotiating a difficult situation. The remaining four, which are based on images from the fifteenth century, all include images of male surgeons with midwives and female attendants now in a marginal role. Birthing Tray - Eggs and its subsequent iteration as Birthing Tray - Stitched: Eggs (Figure 8), derived from a fifteenth-century illumination of the Faits de Romains, shows a male surgeon wielding a knife, a midwife in an attending role pulling out the child (just visible beneath the glass bowl), and a figure on a chair in the foreground who seems to be praying for the survival of the child. Birthing Tray-Wishbone and its subsequent iteration as Birthing Tray - Stitched: Wishbone (Figure 9), also based on an image from the Faits de Romains in the fifteenth century, shows a male surgeon, who is represented as a dark ominous presence, pulling the child from the open abdomen of the woman into the receiving cloth held out by a midwife, while another figure, leaning on the far side of the bed, is in prayer.

Dixie's images are, however, not literal transcriptions of their sources. Rather, as with The Interior, they are infused with allusions to discourses about discovery and exploration that underscore-and complicate-their meanings. In Birthing Tray -Wine and Birthing Tray - Stitched: Wine, an iguana is shown in the foreground as if part of the birth scene. Birthing Tray - Stitched: Eggs includes a large lizard and bird of prey on the left, just outside the birth chamber, while inside-on the right- is a sextant. In Birthing Tray -Stitched: Wishbone, an elephant is shown outside the room. The animals depicted refer to those included in bestiaries, illuminated texts that were popular in the medieval and early Renaissance periods in Europe-a relationship that is emphasised in the Birthing Tray - Stitched prints through the addition of jewel-like colours reminiscent of those used by illuminators. Bestiaries seem to have been the iconographic origin for illustrations of animals that became part of the visual rhetoric of cartographers such as Blaeu (Figure 5). While often fantastical and informed by myth and imagination rather than observed reality, animals depicted in bestiaries simultaneously spoke of a mysterious world in the process of being revealed and recorded during exploratory travel. In picking up on this discourse but associating it with scenes of caesarean birth, Dixie creates an analogy between the exploration of new mysterious lands by Westerners and the 'scientific' excursion into women's wombs on the part of male surgeons. While both sorts of discovery are undertaken in the name of science, they also both entail violence and the privileging of a masculinist western force and authority over the foreign/other/feminine.

The foodstuffs on the trays tend to invoke a sense of violence. In the case of Birthing Tray - Wine, the deep red of the wine, which is seen from above, reiterates the wound in the mother's belly, suggesting a pool of blood. The additions to the print in 2022 enhance this connection. In Birthing Tray - Stitched: Wine, the varnish over the motif of the wine in a glass not only highlights this detail, but also imbues it with a sense of viscosity that is suggestive of bodily matter. In addition to enhancing the analogy between wine and blood through the use of red in both, adding stitches to the incision in the mother's belly invokes the sense of a violation of the body through a pricking and stitching into the format itself. The crystal goblet in which wine is placed seems like it could readily shatter, like the dead mother's womb. In Birthing Tray - Stitched: Eggs, the white eggs in a glass bowl seem like ova potentially vulnerable to the sharp knife wielded by the surgeon and the sharp point of the sextant. As with the motif of wine in Birthing Tray - Stitched: Wine, the varnishing of the eggs in the bowl in Birthing Tray -Stitched: Eggs creates a sense of bodily inchoateness through its viscosity, while the addition of red stitches to the knife, suggestive of blood, enhances an evocation of its capacity for violence. In Birthing Tray - Stitched: Wishbone, the wishbone-emphasised through the addition of varnish-is pincer-like, suggesting its potential for violence, while also reiterating the legs of the deceased mother as well as the shape of the arms of the figure in prayer at the far side of the bed.

Dixie exhibited The Interior on several occasions, and it became clear to her that the fragile laminated sheets constituting the work were falling apart. In late 2015, she had an impetus to mend the work. She had recently separated from her husband and was moving house. She explains: 'I was very distressed that this big piece of work had been falling to pieces. And I guess it was almost like a psychological thing of trying to mend something that was broken, which at the time was very apposite for my life' (Dixie 2022). Paralleling her own attempt to look forward rather than try to recapture a sense of her life as it had been, she decided to not simply mend but also change the work. Heading off to the ichthyology department at Rhodes University, she managed to secure bottled fish in formaldehyde, which she ran through a printing press and then attached to either side of the work. Dixie also found the original woodblocks she had used for the prints on the top row of The Interior and the Birthing Tray series, and decided to make these into new works of art. She likewise envisaged this process as a form of mending and healing: 'It was making something new so that I could let it go. These objects were now not just sitting in the basement of the house rotting but would have another life' (Dixie 2022). The result was The Harbingers (Figures 10-12).

For The Harbingers, Dixie made the nine original woodcut matrices used for the Birthing Tray works into relief sculptures. The original versions of the Birthing Tray series included colour only through objects introduced through the digital photographing of foodstuffs or a cloth or runner underneath the tray, and the woodcut prints were in black and white. In The Harbingers, however, Dixie added hues reminiscent of those used in medieval or Renaissance illuminated manuscripts to the objects themselves. Varnishing over the textual reference to the source on the front of each object so that it is only faintly visible,20 this reference is instead incised on its side. The front of the relief now includes a new incised allusion to the lands mentioned in the corresponding roundel of the original Blaeu map. Excluding the foodstuffs placed on the print and photographed for the Birthing Tray series, each work has a medical instrument attached to its surface instead. These have autobiographical resonance. While Dixie's ex-husband is not a medical doctor, his father and grandfather were in the medical profession, and he had inherited these objects.

There is something apt about the matrices for works focused on maternity being deployed to themselves give birth, as it were, to a new series. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary (2018), the word 'matrix' has fourteenth-century roots and is derived from matris or matrice, which was Old French for 'uterus' or 'womb'. Therefore, on a formal or structural level, the works stress the idea of birthing and the womb. This idea of rebirthing may also be apt for an artist who was herself, as it were, in the process of being 'reborn' into a new condition or state of being.

The title of the series is also resonant. Dixie observes that the word 'harbinger' comes from the Old Saxon 'herbenger', which alluded to shelter or lodging for an army while at the same time evoking 'the concept of harbouring a person or an emotion' (Christine Dixie 2020/07/08). Evocative in terms of a representation of birth, where a child is literally 'harboured', the word 'harbinger' was also suggestive of how the works served as a locus for Dixie's own emotions as she transitioned from being married to divorced and from one home to another.

However, the word 'harbinger' also invokes a sense of foreboding, which is reinforced through the titles of the individual works. The matrix used for Birthing Tray - Wine and, in 2022, Birthing Tray - Stitched: Wine has become The Harbinger of Carnage in Mina (Figure 10). Birthing Tray - Eggs (and subsequently Birthing Tray - Stitched: Eggs) is reinvented as The Harbinger of Death in Tangier (Figure 11). Birthing Tray - Wishbone (subsequently Birthing Tray - Stitched: Wishbone) has become The Harbinger of Chaos in Mozambique (Figure 12). Dixie saw her introduction of words such as 'carnage', 'death' and 'chaos' as alluding to the role cartographic maps such as that of Blaeu took in enabling colonisation. As she explains, they refer 'to the destruction that came in the wake of the "civilizing" mission that cartographic maps like these heralded' (Dixie 2022). While Dixie has long worked with difficulties around the colonisation of Africa, and this iconography, in turn, informed the original iteration of The Interior and the Birthing Trays, its increased emphasis in The Harbingers seems to have been prompted by decolonisation drives at universities in 2015-a connection the artist made in a discussion with me about the origins of the series (Dixie 2020b). The 'Rhodes Must Fall' movement, which arose in March 2015 and developed subsequently into 'Fees Must Fall', had particular influence and impact at Rhodes University, an institution that carried the name of Cecil John Rhodes and had historically been intricately connected to British imperialist thought. In such a context, the idea of an imminent reckoning-implicit in the idea of a 'harbinger'-was resonant.21

Adding instruments to the works enhances associations of the caesarean and medical exploration with incursions into foreign lands. In The Harbinger of Carnage in Mina, for example, a surgical tool implied to have been involved in extracting the child from the mother's womb is simultaneously reminiscent of a protractor used for navigational calculations. In The Harbinger of Eternal Death in Tangier, the round arch of the pincers of the forceps pinch and restrain the mother's head, while seeming like the open beak of the bird of prey depicted on the far right and simultaneously echoing the curve of the navigational sextant seen on the left. Furthermore, in The Harbinger of Chaos in Mozambique, the curve of the medical instrument reiterates not only the arm of the midwife holding a receiving blanket and the arm of the surgeon pulling the child from the gaping wound in his dead mother's abdomen but also the shape of the elephant trunk.

There are further ways in which these instruments suggest an impetus towards violent suppression and forcible submission at play in both discourses of exploration and those pertaining to caesarean birth. Steely and sharp, they read as weapons and instruments of torture: discoloured through age, their presentation seems in some ways evidentiary. However, while these read as disturbing indices of what has already happened, the word 'harbinger' in their titles suggests something ominous in the future. If the making of The Harbingers stemmed from a reparative impetus, given the changes in Dixie's personal life, the titles of the works paradoxically invoke the idea of an imminent reckoning-a reading suggested by Dixie's institutional context and the decolonial drives that had recently been foregrounded.

Conclusion

While Reshada Crouse and Christine Dixie do not know each other personally and have only superficial knowledge of each other's work, there are some commonalities in their deployment of childbirth as a topic. Both artists were first prompted to use this subject matter when about to give birth but later returned to the theme when they were past their childbearing years. Moreover, both, in different ways, invoked references to the gendering underpinning medical practices associated with birth. While there are also distinct differences in their responses to discourses and images from the West, both have represented childbirth in such a way that they have enabled critical reflection on not only gendered power dynamics at play in the delivery of a baby but also, though metaphor and association, other currents in their lives and social environments.

Acknowledgements

I thank Reshada Crouse and Christine Dixie for engaging with me about their works, and Paul Mills for taking photographs for me. My research was made possible by generous funding from the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa. Please note, however, that any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed here are my own, and the NRF accepts no liability in this regard.

Notes

1 Crouse's undergraduate training was followed by graduate studies at the University of Cape Town and Saint Martin's School in London. She makes her living from painting portraits but also produces paintings on topics and themes of her own choice.

2 Precedents include Monica Sjoo's God Giving Birth (1968) and some performances at Womanhouse, a space established by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro for their Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts (January 30 - February 28, 1972).

3 For more on these early manifestations of feminist art, see Schmahmann (2015).

4 Dixie studied for a Bachelor of Fine Art at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, before undertaking Master of Fine Art studies at the University of Cape Town, graduating in 1993. Prior to moving to Makhanda, she lived in Nieu Bethesda in the Eastern Cape.

5 Parturient Prospects included further works, among them the Parturition series. These are discussed in Schmahmann (2007).

6 In 2014, Crouse painted a very pregnant Danielle alongside her new-born son. But this work did not focus on the birth process itself.

7 Crouse's early images of childbirth, although mentioned briefly in reviews, have not been the topic of any developed scholarly engagement, and her Homo Sapien - Spiritual Animal has not been explored at all. While I have previously written about Dixie's images of childbirth from 2005-6 (Schmahmann 2007), this is the first exploration of their subsequent reworking in The Harbingers and Birthing Tray - Stitched.

8 Carrim (2006:121) observes that while black women had no political rights and were completely marginalised within the economy, white women too experienced prejudice. The latter 'did not have access to all jobs that men had access to, were not paid the same salaries as men, could not own property without the consent of men and were treated legally as "minors", dependent on the income, authority and consent of a "white" male presence.'

9 My understanding of these circumstances was gleaned through e-mail discussions as well as by reading Crouse (2021).

10 Legal abortion was difficult to obtain in an apartheid South Africa. Commenting on the 1975 Abortion and Sterilisation Act, Cathy Albertyn explains: 'Abortion was only available in the absence of choice, either in the sex that preceded pregnancy (rape or incest) or in the health consequences of that pregnancy (serious enough to threaten the life of the mother). Those women were seen as "morally blameless". ... [Women] who "chose" to fall pregnant by having sex outside of marriage, were not eligible for abortions and should 'live with the consequences' (Albertyn 2015:432).

11 See Allara (1994) for a reproduction and discussion of the work

12 The birth was in fact particularly agonising because, having been induced, contractions were shortened into a concentrated period, and Crouse did not receive an epidural injection.

13 It was included in Courbet Reconsidered (1988) at the Brooklyn Museum. It was more accessible and photographs of it readily available when it became part of the Musée d'Orsay collection in 1995.

14 'A white cheesy substance that covers and protects the skin of the fetus and is still all over the skin of a baby at birth. Vernix caseosa is composed of sebum (the oil of the skin) and cells that have sloughed off the fetus' skin' (Marks 2021).

15 Exact statistics are difficult to get, because of underreporting. In the year 2015-16, when this work was made, there were 41 503 reported cases in total-that is 77 cases for every 100 000 people.

16 See Schmahmann (2007:29) for a reproduction.

17 One of the works, Birthing Tray - Mussels, represents a plain wooden tray.

18 See Musacchio (1997) and Musacchio (1999).

19 See Chapter 3.

20 Each was incised in reverse because it was previously the matrix for a print.

21 Indeed, immediately after these works, Dixie began another series focused on the idea of 'harbouring' which was called Harbouring Fanon.

References

Albertyn, C. 2015. Claiming and defending abortion rights in South Africa. Revista Direito 11(2): 429-454. [ Links ]

Allara, P. 1994. 'Mater' of fact: Alice Neel's pregnant nudes. American Art 8(2):6-31. [ Links ]

Blumenfeld-Kosinski, R. 1990. Not of woman born: Representations of caesarean birth in Medieval and Renaissance culture. New York: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Brotton, J. 1997. Trading territories: Mapping the early modern world. London: Reaktion Books. [ Links ]

Carrim, N. 2006. Human rights and the construction of identities in South African education. PhD thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Crouse, R. 2021. Art is the devil - the story of an unfashionable painter. Transcript of autobiography that the artist plans to publish. [ Links ]

Crouse, R. (reshada.crouse@gmail.com). 2022. Comments on Danielle and Danielle and Me. Email to B Schmahmann (brendas@uj.ac.za). Accessed 2022/04/13. [ Links ]

Dixie, C. (c.dixie@ru.ac.za). 2020a. Background information on The Harbingers. Email to B Schmahmann (brendas@uj.ac.za). Accessed 2020/07/08. [ Links ]

Dixie, C, artist. 2020b. Interview by author. [Transcript]. 30 July. Online. [ Links ]

Dixie, C, artist. 2022. Interview by author. [Transcript]. 21 February. Online. [ Links ]

Johnson, G & Matthews Grieco, SF (eds). 1997. Picturing women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Kristeva, J. 1982. Powers of horror: An essay on abjection. New York, NY: Columbia Press. [ Links ]

Marks, JW. 2021. Medical definition of vernix caseosa. [O]. Available. https://www.medicinenet.com/vernix_caseosa/definition.htm Accessed 17 January 2023. [ Links ]

Musacchio, J. 1997. Imaginative conceptions in Renaissance Italy, in Picturing women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, edited by G Johnson and SF Matthews Grieco. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press:42-60. [ Links ]

Musacchio, J. 1999. The art and ritual of childbirth in Renaissance Italy. New Haven, CT & London: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Online Etymology Dictionary. 2018. [O]. Available https://www.etymonline.com/word/matrix. Accessed 17 January 2023. [ Links ]

Schmahmann, B. 2007. Figuring maternity: Christine Dixie's Parturient Prospects. De Arte 75:25-41. [ Links ]

Schmahmann, B. 2015. Shades of discrimination: The emergence of feminist art in apartheid South Africa. Woman's Art Journal 36(1):27-35. [ Links ]