Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Image & Text

versión On-line ISSN 2617-3255

versión impresa ISSN 1021-1497

IT no.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a19

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Inside The Red Mansion: Füsun Onur's world of objects, care relations, and art

Nergis AbiyevaI; Ceren ÖzpinarII

IPh.D. Candidate in Art History, Istanbul Technical University, Istandbul, Turkey. abiyevakizil23@itu.edu.tr

IISchool of Humanities, University of Brighton, Brighton, United Kingdom. C.Ozpinar@brighton.ac.uk (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5981-3474)

ABSTRACT

The Red Mansion, or Hayri Onur Yalisi, acquired by the artist's family in the 1930s, has been home to the Turkish sculptor and installation artist Füsun Onur and her sister ilhan for almost her entire life. It has a significant place in the artist's career as it houses not only her life, studio, and archive, but also the affectionately preserved mementoes of her mother. In this article, we explore the role of the Red Mansion and its concentrated materiality in Füsun's art and her relations with objects, her family, and her sister ilhan. We examine four of her artworks, which we argue are based on collaborative creativity and mutual care: Dollhouse (1970s), Counterpoint with Flowers (1982), The Dream of Abandoned Furniture (1985), and Once Upon a Time (2022). The interdisciplinary theoretical framework of our analysis draws upon care studies, family sociology, object-oriented ontology, and psychoanalysis. We propose that the Red Mansion and the objects therein are deeply connected to the artist's unique understanding of home and family, which defines her work, evoking a caring world that values humans and nonhumans alike.

Keywords: Füsun Onur, objects, home, sisterhood, care.

Introduction

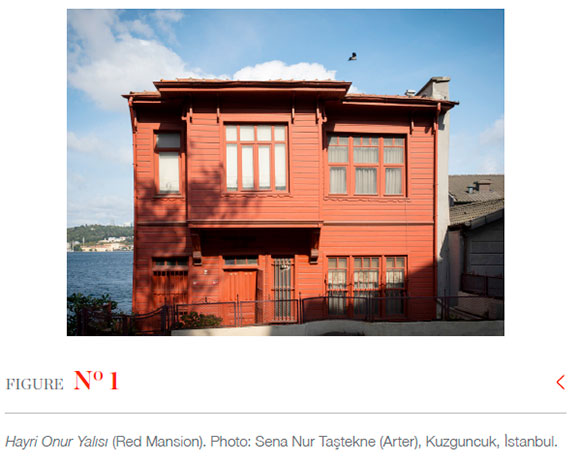

The Red Mansion, acquired by the family of the Turkish sculptor and installation artist Füsun Onur (b. 1937, hereafter Füsun) in the 1930s, has been her home for almost her entire life. It has become her exclusive home with her sister ilhan Onur (1929-2022, hereafter ilhan) and their cats in the last few decades. It holds a significant place in Füsun's life and career. The house was originally named after the artist's father, Hayri Onur, and is known as Hayri Onur Yalisi in Turkish. However, because of the striking appearance of its red ochre paint, it has become more widely known as the 'Red Mansion' and is also called this by the artist and her family. A particular type of nineteenth-century Ottoman waterside residence, the Red Mansion is situated in Kuzguncuk, one of the oldest neighbourhoods on the Asian side of the Strait of Istanbul, which has many houses of similar construction and style, defining the historic character of this area (see Figure 1). Over the decades, the neighbourhood has maintained its self-contained, quiet character and natural beauty, perhaps because it is cut off by the Strait on the north side and the green downs on the south. It was home to several artists and writers over the years (Dursun 2019). Due to its splendour, the Red Mansion has recently attracted many visitors to the area, bringing renewed attention to Füsun's oeuvre, as well as fostering interest in the Onur sisters' lives. This unique house contains not only the artist's studio and archive, but also numerous memorabilia, resembling a collection of curiosities, which Füsun and ilhan inherited from their parents, and expanded. In 2021, the sisters announced that they had bequeathed the Red Mansion to the Vehbi Koç Foundation (established by the Koç family that owns Turkey's largest conglomerate of companies), who undertook to turn it into a house-museum and a place for artist residencies (Altunok 2021).

However, despite this popularity, far too little scholarly attention was paid to Füsun's artistic practice until the 1990s. While some research has been conducted on her use of unconventional materials as a way of understanding her subjectivity (Atagök 1997; Antmen 2013; Yilmaz 2009), so far, only one study has attempted to explore the meaning of objects in her work (Çiçek 2021). No previous study has investigated the caring relationships the artist developed in her home and life as a definitive element in her work. To explore the intertwined relationships between Füsun's artistic practice and human and nonhuman worlds, in this article, we investigate the role of the Red Mansion and its concentrated materiality, and Füsun's relationship with objects, her family and, especially, her sister ilhan in her art, which we argue was based on collaborative creativity and mutual care. We explore four of her artworks across her enduring career: Dollhouse (1970s), Counterpoint with Flowers (1982), The Dream of Abandoned Furniture (1985), and Once Upon a Time (2022). An interdisciplinary theoretical framework guides our analysis, drawing on care studies, family sociology, object-oriented ontology, and psychoanalysis. Considering Füsun's artistic views, expressed in her interviews, essays, and correspondence, together with visual and contextual analysis, we argue that the artist's relationship with the Red Mansion has been definitive in her work. Her sibling affection and the sisters' egalitarian and caring approach to the nonhumans of the house demonstrate their non-normative relational capabilities, built on a worldview that activates the energies inherent in all entities and beings.

Care relationships in the family

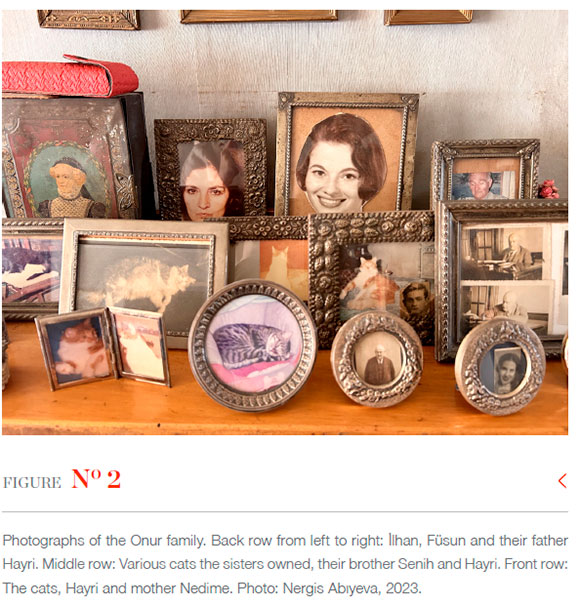

Füsun is the youngest of three siblings born in the red three-storey wooden house, situated a little way from Kuzguncuk's centre. Füsun and her older sister ilhan spent most of their lives there together. The Red Mansion once used to be a summer house for the Onur family and when Füsun was a child, they lived in Kadiköy, a bustling market area with working- and middle-class residents, and only spent the summer season in Kuzguncuk. After Füsun's father passed away in 1951, the family rented out the Red Mansion to resolve their financial problems (see Figure 2). After 1967, however, the sisters decided to settle in the house permanently, allocating the ground floor to the artist as a studio.1

Füsun and ilhan's parents cared deeply for their two daughters. As Füsun recalls, their mother 'liked to dress [them], and [their] father liked to feed [them]' (Onur cited in Baykal 2007:9). Throughout their formative years, the siblings were encouraged to foster their creativity, particularly by their father Hayri (?- 1951), who was often away for work as a shipbroker (Savas 2008). The children were allowed to let their imaginations run wild and draw freely on the walls, using the art materials regularly provided by their father, who had a great interest in art (IKSV 2022).2However, the influence of their mother Nedime (?-?) on their upbringing and the formation of their aesthetic awareness is also irrefutable. She encouraged their interest in art and crafts and revelled in collecting objects herself (Brehm 2007: 18-19). As Füsun has noted,

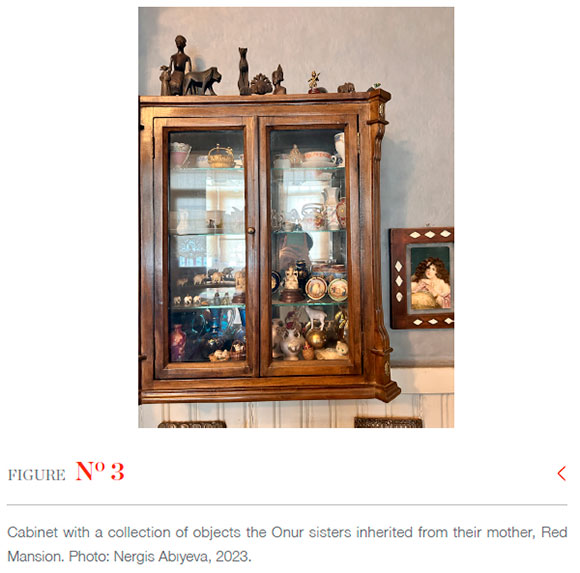

My mother ... always kept the small things she liked, in fact, she waited to possess them. She [would wait] for the [shop] window to change to get a tiny [figurine] ..., she [would ask] my father to keep a close watch on the shop. She would cut out the picture of a rose she liked in the newspaper, keep the wrapping paper of [the gifts she was given] and collect colour postcards. Years later she destroyed a part of what she had collected because she thought people would make fun of her. And she started giving us the ones we liked from what remained (Onur cited in Baykal 2007:5). (see Figure 3)

The sisters affectionately preserved memories of their parents, especially their mother, by maintaining an extensive collection of objects, garments, and photographs. The Red Mansion contains countless drawers, cabinets and cupboards, packed with keepsakes, figurines ('tiny ballerinas, horse carriages, women with umbrellas'), tin boxes, and the sisters' early childhood clothes that their mother had kept (Baykal 2007:9). They also kept family heirlooms, including '[old] furniture, glass cabinets, [framed family photographs], mirrors, porcelain plates, embroidered tulle curtains, needlework covers' (Baykal 2007:2). In interviews, they pointed out that they never became weary 'of what [their] mother and father had purchased; [and] didn't want to replace those objects with new ones' (Onur cited in Öztat 2014).

Virginia Held (2006:31) defines care as an 'activity that includes "everything that we do to maintain, continue, and repair our 'world' so that we can live in it as well as possible," and care for objects and for the environment as well as other persons'.

The sisters have cared equally for the objects and their companion cats who have lived with them over the years (whose framed photographs can be seen on display in the house next to family pictures): they never adopted a cat, but cats unerringly adopted them and made the Red Mansion their home. They have also established personal caring relationships with what are often seen as 'inanimate objects', which we discuss further below. The relational capacities they have developed unsettle patriarchal norms and social conventions across human and nonhuman worlds.

Füsun and ilhan's caring relationship, learned from their parents, cultivates sensitivity to each other's needs and 'the needed "engrossment" with the other' (Held 2006:32). Importantly, they established a non-authoritarian sistering relationship, as they 'retained notions of attachment and loyalty associated with non-contractual family relations' (Mauthner 2005:636). Sister relationships are often described as hierarchical in that they operate similarly to the relationship between a parent and a child, where 'the older sibling teaches, dominates, and leads, while the younger sibling learns, submits, and follows' (Borairi et al. 2023:110). However, Füsun and ilhan's sisterhood is far removed from such hierarchical sibling relationships whose structure is often prescribed by the patriarchal nuclear family's power dynamics. Predominantly based on a maternal genealogy, their interaction can be described as 'peer-like' due to their intimate relationship with their mother.

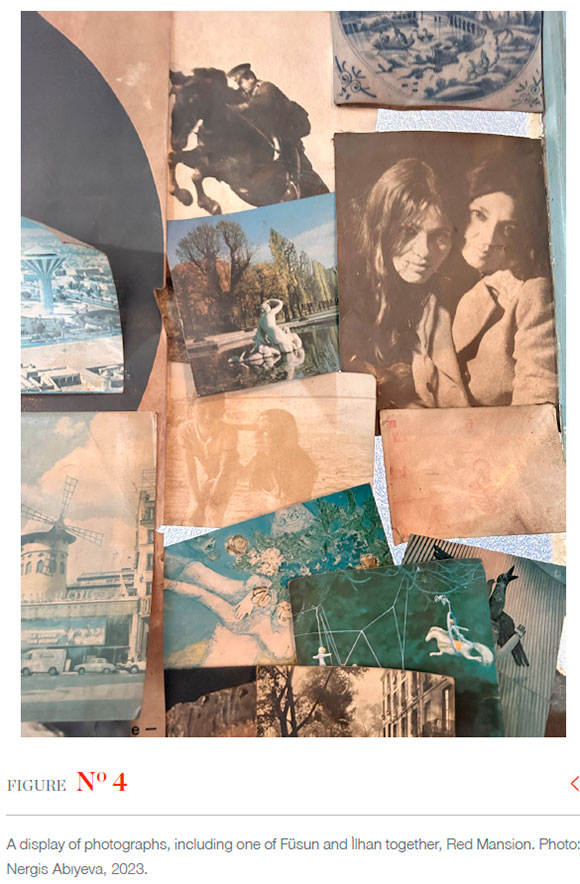

Drawing on feminist ethics, Maria Puig de la Bellacasa (2017:69) describes care as a recognition of interdependency, an essential value to existence and a condition of relationships in human and nonhuman worlds: 'not only [do] relations involve care, care is relational per se'. Similarly, Melanie Mauthner (2005:634) argues that 'sistering evolves according to internal dynamics such as shifting caring and power relations-varying degrees of control and autonomy between sisters'. Illustrating this caring relationality and interdependency, the Onur sisters have 'compromised and made sacrifices together' (Onur cited in Baykal 2007:9). For example, neither married nor had long-term romantic partners. Single by choice, marriage or children did not become the focus of their lives or overshadow their sistering ties (Hallett 2022). Moreover, ilhan put her sister first in her life and career: 'when [Füsun] decided to be an artist, [she] preferred to support her' (Abiyeva 2016) (see Figure 4). In addition to contributing to her artistic labour, ilhan took on unwaged domestic labour, enabling Füsun to dedicate all her time to her artistic practice (Sönmez 2022). ilhan's presence in Füsun's life and career was so essential that the artist has confessed, 'If ilhan was not involved, there would not even be the photographs [of my works]. There would be nothing' (Onur cited in Öztat 2014). As part of their collaborations, ilhan also became Füsun's archivist, documenting her art and exhibitions. Reciprocally, apart from a few years Füsun spent in the US to study for her master's degree at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), she always stood by ilhan's side. They shared their lives for the best part of seventy years (until ilhan passed away in April 2022) in a caring relationship far from the hierarchical constraints of age, gender, and power.

Collective creativity and care

In her early career as a sculpture student at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul (1956-1960) and as an MA student at MICA in Baltimore (1962-67), Füsun predominantly used clay and plaster for casting. From the early 1970s, however, she abandoned forms and materials that were familiar to her (Özayten 2013:66), and began using wood, glass, plexiglass, and styrofoam instead. She consistently worked with various materials, including ordinary ones from everyday life. Füsun 'strip[ped] them from their [function] and use[d] them as [her] notes' (Onur cited in Baykal 2014:132). Any object, including miniature figurines and furniture, could enter her sculpture space and become a part of the work. Some of these materials were those that, in her own words, she had 'seen used at home' (Onur cited in Önal-Sagiroglu 1991). Others were 'unfamiliar' materials that existed outside the Red Mansion, or those she had never seen before but felt an instant connection with. The artist's contact with these materials has often assumed an almost occult character: when she encountered them 'they [suddenly] seemed familiar [to her]. It was like a moment of epiphany' (Onur cited Önal-Sagiroglu 1991).

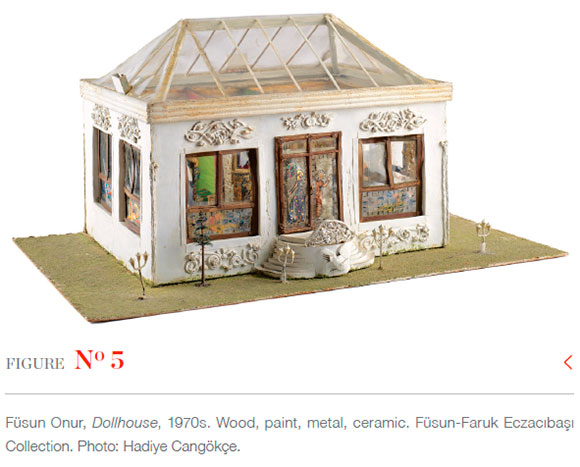

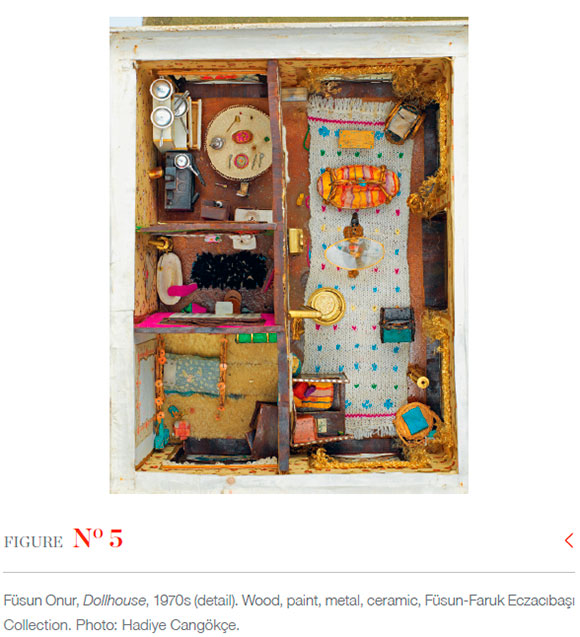

In the 1970s, the Onur sisters' caring relationship culminated in the Dollhouse, a three-dimensional work shaped like a miniature house (see Figure 5). Although the Dollhouse was exhibited in Füsun's 2014 retrospective at Arter Gallery in Istanbul, she did not produce it as an artwork per se. The work stemmed from the sisters' shared activity during a period of recreation when Füsun was preparing for a new artwork. She was playing with some miniature objects when her sister suggested putting them in a box: ilhan made a box, and Füsun placed the pieces inside (Öztat 2014). Recollecting the event slightly differently in another interview, Füsun explained that since they had always enjoyed miniature things, the sisters settled on creating a model house together. Friends and acquaintances who had seen them working on the house brought some of the fixtures, but, by and large, it was ilhan who helped Füsun make the house and the objects (Özpinar 2016). Indeed, Füsun has acknowledged several times that her sister always supported her during the production and installation of her artworks, both emotionally and sometimes as a co-maker. Resonating with Held's (2006:32) understanding of care, which 'can and should be play and creative activity', the sisters' collaborative process is a testament to their mutually caring and learning relationship, rooted in shared artistic interests and playfulness.

The sisters created a dollhouse with four rooms-a large living room, a kitchen, a bedroom, and a bathroom-and included miniature furniture, including armchairs and a sofa, a single bed, appliances, cookware, and a tub. At first glance, the miniature house suggests several symbolic and literal references to the Red Mansion. As previous studies have suggested, the Red Mansion and its materiality, with an aura imbued with their mother's memories, might have added a distinctive quality to the Dollhouse as it has in many of Füsun's works (Yilmaz 2009; Antmen 2022). Yilmaz (2009:218-9) writes that the artist has integrated the home's collection of objects into her work, re-enacting the Red Mansion in various forms. Indeed, in the Dollhouse, the exceptionally large armchair she made to allow for room for her books on the side (visible in the bottom centre in Figure 6) evokes the antique chair with ebony and mother-of-pearl inlay in the Red Mansion. Amongst the most striking furnishings that the artist devised-the large knitted rug, the retro conversation sofa in a red and yellow striped fabric, and the antique stove in the living room-it is the latter's vintage style that most resembles the real-life equivalent in the Red Mansion (the blue and white ceramic stove in the studio). The collectable miniature kitchen cupboards and various life-size trinkets, which the Onur sisters display in various places in the Red Mansion, also appear in the model house: the similarities hint at the sentimental value it has for the sisters. Indeed, the two female silhouettes on the stained-glass French door of the Dollhouse suggest a match with the sisters themselves.

On closer inspection, however, it is noticeable that the Dollhouse only creates an impression of the sisters' self-sufficient lives, as it is not only downsized in scale, but also offers a single-occupant version of the actual house. Moreover, the model house's interior design is simpler and comparatively free of the collection of objects the sisters have maintained (Yilmaz 2009:218-9). Its exterior also features decorative plasterwork, small decorative garden lights, a pine tree in the small front garden, and a tiny terrace in front of the French windows, which are all elements absent from the Red Mansion. While ilhan tended to describe the Dollhouse as a simple box with objects in it (Onur cited in Öztat 2014), Füsun's recollection of the making process suggests a potential line of analysis that considers the more intuitively conceived aspects of the work. Parallels can perhaps be drawn between the work, not only with the objects the Onur sisters inherited from their mother, but also the artist Joseph Cornell's 'obsessive collecting', which famously led him to create boxes that assembled objects and ephemera.3 Joanna Roche (2001:11) has called Cornell's boxes a 'psychic space', and explored his friendship and correspondence with the artist Carolee Schneemann, who is also known to have experimented with boxes in the 1960s. Roche has elucidated Schneemann's 'symbolic doubling' of this medium as 'vaginal space'. Packed with shards, dead birds, lights and painted-over photographs, Schneemann's boxes indicate a deep investigation into the psyche and the body. Cornell and Schneemann both considered the box as a space to create 'inherent controlled expression' (Roche 2001:11). Although little is known of their psycho-sexual pasts, the Onur sisters' miniature house may equally be seen as an expression of repressed desires and emotions. Their caring relationship, engrossed in each other, and previously their mother, may indicate suppressed thoughts: one could argue that the Dollhouse alludes to sisterly affections while restraining the concentrated materiality of the Red Mansion and, by extension, their mother's emotional pull.

More than human worlds

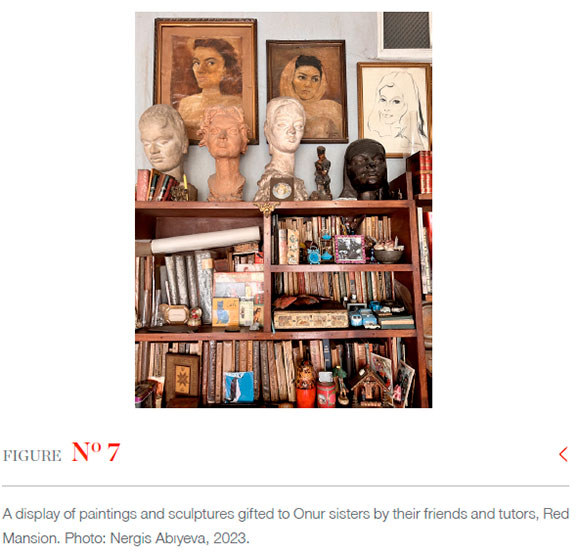

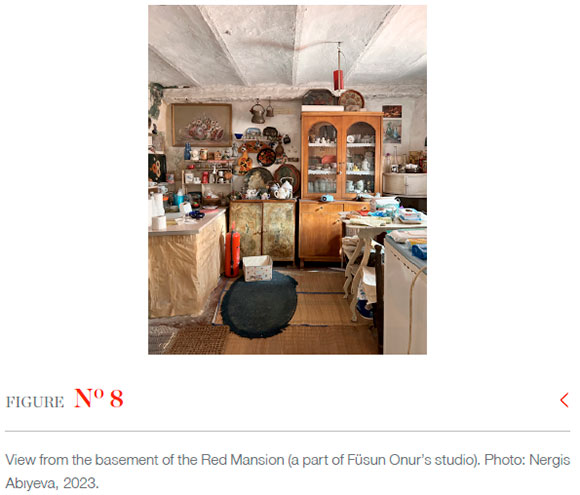

Growing up amongst objects, the Onur sisters have long been fascinated by them. In addition to keeping Füsun's early creations, such as drawings and busts, they retained prints, sculptures and paintings gifted to them by their friends, colleagues and tutors, which collectively produced a jumbled display on the walls and surfaces of the house (see Figure 7). Füsun's studio also houses a myriad of objects, including dolls, miniature furniture, their brother Senih's (1933-2019) childhood paintings, and an old television (see Figure 8). However, the wardrobes and cabinets that contain objects the sisters inherited from their mother, and more they have accumulated over the years, evoke the most ritualistic and intimate energy that connects them to their mother. Of these objects, her mother's postcard collection perhaps elicits the most affectionate memories. Füsun regards it 'as an early treasure trove of images whose playfully elegant ornamentation inspired her own work' (Brehm 2007:18-19).

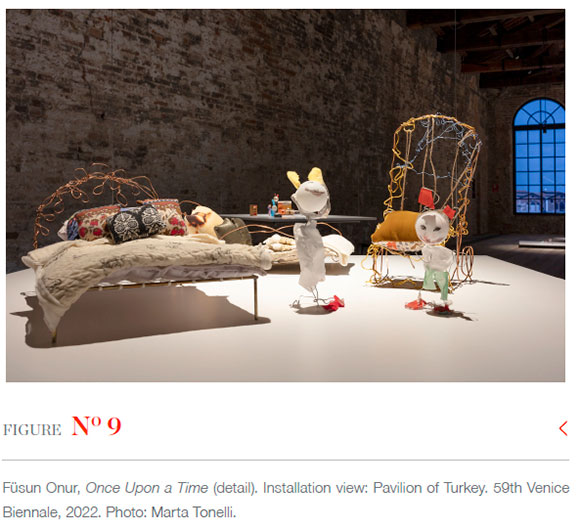

Cornell believed that objects spoke and related to each other in unprecedented ways (Roche 2001:11). In the same vein, the caring relationship Füsun and ilhan cultivated together in the Red Mansion extended to the nonhumans of the house. Instead of seeing them simply as 'objects' and 'animals', the Onur sisters seem to have envisioned a 'dynamic world of active agency in which everything participates' (Van Dooren cited in Puig de la Bellacasa 2017:74). They possibly considered not only their companion cats but also the Red Mansion's 'inhabitants that are not animals' as kins and allies. The last work that Füsun produced before ilhan passed away, which was for the Turkish Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022, is an example that illuminates this distinctive world vision. Entitled Once Upon a Time, the immense installation included twenty-one platforms showcasing multiple compositions of small figurines created from wire, ping-pong balls, paper, and fabric (see Figure 9). Illustrating an original post-human tale written by Füsun herself, the work features two protagonists: a mouse called Cingöz, who is concerned about the climate crisis, and a cat called Zorba, who is named after the Onur sisters' last cat whom they considered one of their life companions (Abiyeva 2022). Consisting of elaborately crafted miniature elements, Once Upon a Time is reminiscent of the Dollhouse. Conceived along similar lines of an art-making process that is akin to a fun pastime shared between the sisters, this work also embodies collective creativity and caring relationships that involve more than human worlds. Spotlighting a cat and a mouse in this work, Füsun draws attention to how the climate issue impacts humans and nonhumans. In her world, things, animals, and humans connect through anti-hierarchical and anti-patriarchal forms of autonomous encounter and care. Maria Puig de la Bellacasa (2017:69) sees an 'inevitable interdependency essential to the existence of reliant and vulnerable beings' in these kinds of kinships and alliances. Established with more than human worlds, they 'become transformative connections-merging inherited and constructed relations' (Puig de la Bellacasa 2017:73)

The thing-power of the objects

Füsun has stated that, despite their magical qualities, she never used items from her household because of their emotional attachment (Önal-Sağiroğlu 1991). She has instead sought out materials inspired by the Red Mansion. As previously mentioned, Füsun has approached materials non-conventionally and worked with a wide variety of them since the 1970s. Sometimes, she avoided certain materials, such as wood, because the artisans who assisted her questioned her designs. At other times, she collected objects from friends or visited local thrift shops to find what she had drawn in her sketchbook. Often, she preferred working with her hands. Consequently, she developed an extensive catalogue of materials and a caring relationship with them. Her interest in objects clearly stemmed from the material culture Füsun had seen nurtured by her parents in the Red Mansion. However, the dissertation she wrote as a master's student at MICA in 1967, entitled 'The art object as a possible self in a possible world, publicly put forth on its own account as possibility of being', could also be key to understanding the subtleties of this relationship. In her dissertation, with references to the writings of Walter Kaufmann, Georg W. F. Hegel, and Jean-Paul Sartre, Füsun has argued that 'it is the consciousness that gives an art object its spiritual truth' (Onur 1967:170). This view first led the artist to consider the relationship between the different sculptures or installation pieces. Gradually, she began creating forms that do not represent anything that exists, achieving autonomous objects.

In her book Vibrant Matter, Jane Bennett (2009:7) elaborates on the notion of 'thing-power', which she defines as the potential of objects. Challenging the very idea of separating things in life into 'living lives and inanimate matter', Bennett (2009:18) draws attention to inert things, writing that they could 'have a life of their own, that deep within is an inexplicable vitality or energy, a moment of independence from and resistance to us and other bodies. A kind of thing-power.' This concept offers a fresh view of objects' existence in the human world. Suggesting a 'liveliness intrinsic' to the object, Bennett (2009:4) notes that thing-power provokes affects in humans, although they do not bestow this quality to nonhumans. What Füsun calls 'consciousness' has compelled her to see objects (and animals) as kins and allies with an active agency, comparable to Bennett's 'thing-power'. Things command their own existence, which rejects the idea that the artist or anyone else has power over them, as they disclose themselves as 'vivid entities''(Bennett 2009:5). But objects 'never really act alone. ... [Their] agency always depends on the collaboration, cooperation, or interactive interference of many bodies and forces' (Bennett 2009:21).

Abstract energy

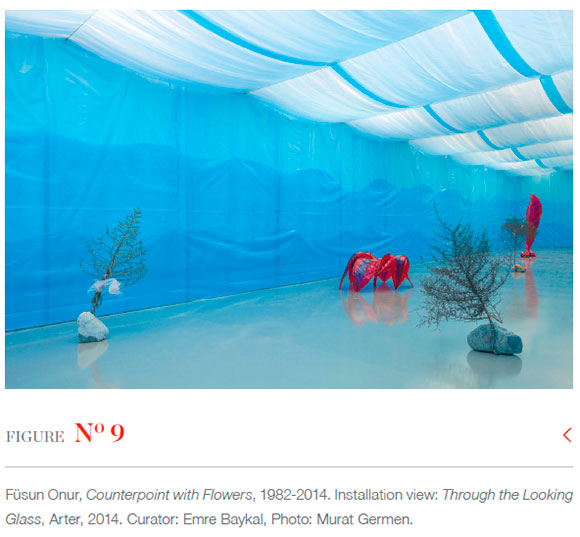

Counterpoint with Flowers (1982) is a work that manifests the entanglements of humans and nonhuman others. The installation consists of three small dried trees, each tied to a small rock, some partially covered with tulle, together with two giant, synthetic red flowers, in an orchestrated composition in a room of the Taksim Art Gallery in Istanbul (see Figure 10). Blue translucent fabric covers the walls and the ceiling, suggesting the swelling blue waters of the Strait of Istanbul, bringing its soothing presence to the gallery. In this respect, the work can be read as an evocation of the Red Mansion's rooms that were filled with reflections of light and the sea. By covering these huge areas with blue fabric, the artist made them an integral part of the work-not only as an empty space but also as a 'vivid entity', an object in its own right. As the art critic Canan Çoker (née Beykal) (1982:24) has suggested,

The viewer assumes to have entered the exhibition space but in reality, they enter the space of the artist without knowing and directly begin living with her. The only thing left to do here is to enjoy the taste of the traditional seeing, watching the strange flowers in the deep blue... Knowingly or unknowingly... the viewer enters the artwork instead of the exhibition space. Therefore, in this exhibition [the artist] brings us to the question of 'real space' - time.

Since her early works, Füsun has not conceived her pieces as detached from the physical space in which they are placed. Referring to sculpture as 'spatial fantasy' and describing the relationship between objects as 'abstract energy' (Onur 1986:956; Dastarli 2014), she has always alluded to sensations that exist beyond the conventional sculpture experience. Working with 'the auras of spaces and the essence of objects, [she intended] to figure out how these might relate to communications between people as well as individual sensibilities' (Haydaroğlu 2013). In Counterpoint with Flowers, by redefining the room as a distinct entity-a space in and of itself, a space to be experienced from within-Füsun has activated the agency within this massive object, which envelops and interacts with the objects and the visitors (humans and nonhumans). Writing about this work in 1982, Füsun noted that the reason she called it Counterpoint with Flowers was the prominent role relational capabilities played here: 'Visual forms present themselves as if simultaneously graspable at a glance, only to be followed by the diachrony which lies within the inner relations of the work' (Onur 1982; 2017:175). The ahistorical and non-representational display of the objects, including the natural and the artificial and the relationships between them, shows the intention of the artist to empower visitors to experience a transformative encounter through their own subjective responses.

Discussing her works in 2001, Füsun has similarly referred to the energies in her work, but also denoted time in music. As she writes,

I am trying to adjust the time and space. I divide sculptures by modules because in painting and sculpture you cannot adjust the time, but in music, you can. You spend two minutes looking at a painting or a sculpture, but in music, you have to adjust that time whether you want it or not. I am making this adjustment because I love music and envy it. Music can activate the hidden energy within us. So I go and find the rhythm for it. I envy music, take its materials and elements and work with them (Onur 2001).

What Füsun refers to here as energy can be explained as the penetrating, surrounding power that she believes music possesses, a quality that she wishes her own works to achieve. The role of music and time is evident in many of them: in Counterpoint with Flowers, for example, the title borrows a western musical term. 'Counterpoint' is defined as a characteristic element that 'combines different melodic lines' and creates a time-based interplay between different units of a composition (Jackson 2020). As an invisible layer added to Füsun's piece, time is thus applied as a tool- it is spread between the elements to create a relationship among them. Activating a previously hidden, sensorial agency that stems from the abstract energy and thing-power of the objects, it connects, splits, and ties all the elements.

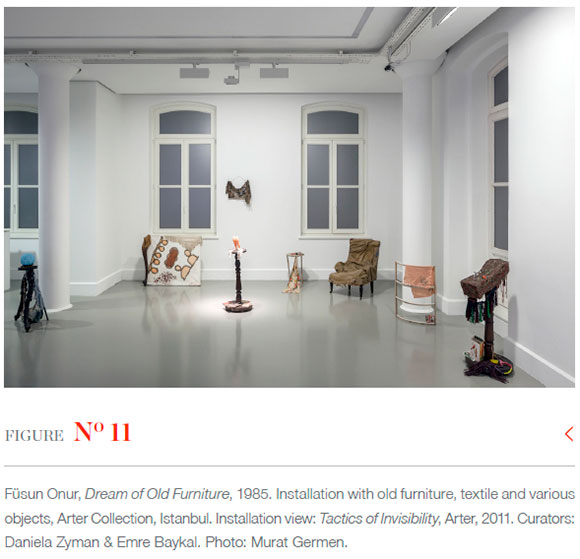

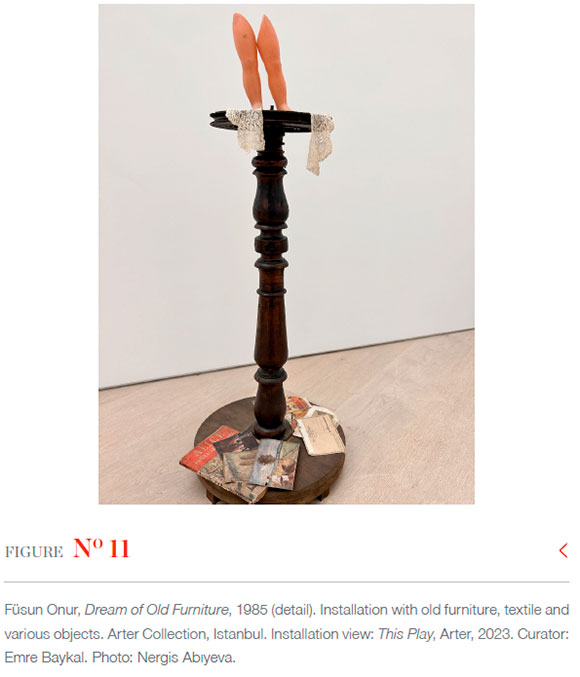

The objects displayed in Füsun's 1985 installation, The Dream of Abandoned Furniture, also embody her caring and empowering approach to human and nonhuman relationships (see Figure 11). Individual and household items are covered with fabrics and pieces of embroidery, and doll parts are added to create compositions reminiscent of dollhouses. Consisting of pieces of furniture that seem to have merged-an armchair and a tablecloth, doll parts, lace and a stool, children's books, toys, table legs, and photos-the artist created objects outside one's experience. Removed from everyday use, these objects become imaginative entities through an exchange of parts, mirroring a vivid realm of imagery. At the foot of a pedestal table, the artist placed the children's book Alice in Wonderland, one of the great literary examples where reality and fantasy meet, as the young woman protagonist journeys to a more than human world. Vintage postcards and photographs that accompany the pieces of furniture are evocative of Füsun's mother's postcard collection. A child's bunny rabbit scissors, miniature animal figurines such as a zebra and a duck, a model train, and beads are attached to the pieces of furniture. Bennett (2009:20) has argued that thing-power calls to mind 'a childhood sense of the world filled with all sorts of animate beings, some human, some not, some organic, some not. ... an efficacy of objects in excess of the human meanings, designs, purposes they express or serve. ... a good starting point for thinking beyond ... the dominant organizational principle of adult experience.' This work seems to be recreating experiences outside adulthood that connect to a world that 'acknowledges nonhuman others [that] are endowed with meaning, power and agency of their own' (van Dooren cited in Puig de la Bellacasa 2017:74).

Füsun's title choice is also significant. While her recent museum retrospectives have referred to this work as The Dream of Old Furniture, the original title was The Dream of Abandoned Furniture, which we think conveys the installation's meaning more fully. In line with Bennett's (2009:16) view of human-made things 'exceeding their status as objects', these unprecedented, born-again pieces appear to have joined forces in their recently abandoned existence (see Figure 12). Rather than being inconsequential, ordinary objects, they refuse to be discarded or abandoned as they are born anew. The poetic title conjures up the endless possibilities of dreams and shows Füsun's treatment of every object to unlock its potential, its 'energies'. It is unclear from the title whether the dream belongs to the artist or the furniture re-affirms the objects' capability of claiming agency in the world of caring that Füsun and ilhan created in the Red Mansion.

Conclusion

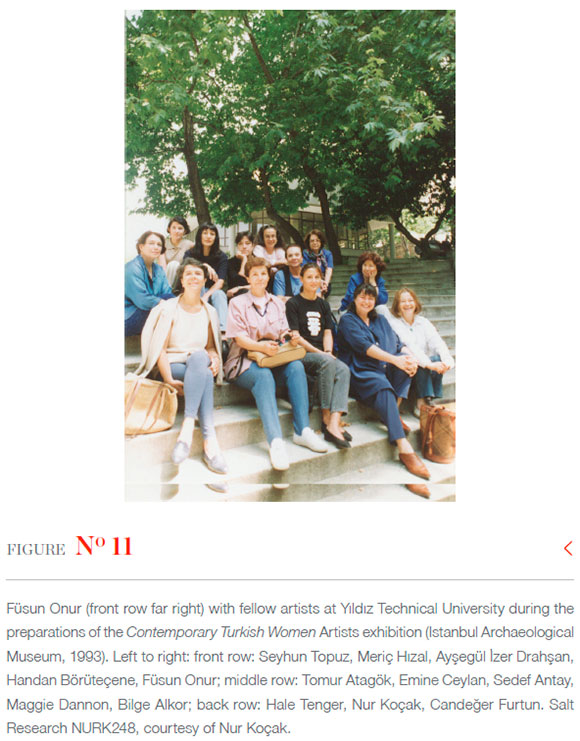

Over the years, the Red Mansion and its human and nonhuman entanglements remained the creative centre of Füsun's world. Especially from the 1970s through to the 1990s, there were periods packed with exhibitions, new work and a busy social calendar for Füsun. From her first solo exhibition in 1970 at Taksim Art Gallery in Istanbul to her participation in the First International Istanbul Biennial in 1987, the artist has been a regular contributor to the local artistic field, as well as a rising star in the international arena. Additionally, in the 1990s, Füsun became a part of a group of artist-women who engaged with contemporary conceptual aesthetics (see Figure 13). However, despite these engagements, Füsun's interviews and correspondence confirm that she maintained a level of voluntary social isolation.

A 1978 letter sent to her friend and fellow sculptor Cengiz Çekil (1945-2015), written at her mother's hospital bed, demonstrates how lonely Füsun felt even at the busiest times. Responding to Cengiz's observation that a robust artistic circle did not yet exist in Izmir-a metropolitan city on the West coast of Turkey, where he lived and worked at the time-Füsun wrote in protest: 'I hardly see anyone [any artists] in Istanbul. I was expecting to see you here in the summer' (Onur 1978). Even later, although she and ilhan had close friends and neighbours such as Sevim Burak, a famous novelist who lived a few roads down from the Red Mansion, the artist preferred to lead what some might call a solitary life. The artist's own words from much later, in 2007, highlight her attitude toward immersing in time on her own: 'I have not left my house in Kuzguncuk much for years. I am nurturing my loneliness. Crowds disrupt my concentration. I have been creating my works while listening to my inner music' (Onur cited in Atmaca 2007).

We believe Füsun and ilhan's caring relationship, inherited from their parents, has cultivated a sensitivity that responds to the needs of others. In addition to fostering peer-like interactions in their interpersonal context, the sisters have cared for nonhumans (objects and animals) in the Red Mansion over the decades. Their close relationship with each other led to collaborative processes shaped by mutual learning and creativity. Sharing labour and authorship, whether domestic or creative, they amalgamated their mode of living with creative work. Dollhouse and Once Upon a Time embody these entangled relationships: while both manifest real-life connections with the Red Mansion and their (extended) family and underline the sisters' concern and care for nonhuman relations, Dollhouse insinuates repressed emotional energies at the same time.

Füsun Onur (front row far right) with fellow artists at Yildiz Technical University during the preparations of the Contemporary Turkish Women Artists exhibition (Istanbul Archaeological Museum, 1993). Left to right: front row: Seyhun Topuz, Meriç Hizal, Aysegül izer Drahsan, Handan Börüteçene, Füsun Onur; middle row: Tomur Atagök, Emine Ceylan, Sedef Antay, Maggie Dannon, Bilge Alkor; back row: Hale Tenger, Nur Koçak, Candeğer Furtun. Salt Research NURK248, courtesy of Nur Koçak.

Pursuing an 'ongoing process of world making ... in which all the various actors literally and physically are the world' (van Dooren cited in Puig de la Bellacasa 2017:74), Füsun's practice has gradually placed nonhuman others centre stage. Over time, her art has increasingly aligned with the sisters' inclusive and non-authoritarian approach to persons, objects, and animals. We argued that their relational capabilities have unsettled normative personal attachments and society's expectations across human and nonhuman worlds. Counterpoint with Flowers and The Dream of Abandoned Furniture were two installations that demonstrated the alignment of these care relationships and the reflections of this particular worldview. Describing an object-driven consciousness in her master's dissertation, Füsun had perhaps laid claim to a new materialist thinking ahead of her time. We suggested that Jane Bennett's thing-power, which characterises nonhumans as actors that participate in the world and produce affects, is a notion that elucidates the spatial and temporal energy of the objects and materials with which the artist has worked. Füsun's oeuvre induces sensorial connections replicating the relational world she has envisioned that embraces and cares for all.

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this article to the memory of ilhan Onur (1929-2022). We extend our sincere gratitude to the artist Füsun Onur for her generosity and time, to the special issue's editor Brenda Schmahmann for her kind support, and to the blind reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

Notes

1 They continued renting out the third floor to friends and acquaintances in the summer.

2 Füsun has noted that her father was not a very successful student in art classes and, as such, wished that his children would be able to paint.

3 Thanks to the audience members at the Hitting Home: Representations of the Domestic Milieu in Feminist Art conference (University of Johannesburg, 2022) for drawing our attention to this visual similarity.

References

Abiyeva, N. 2016. Personal interview with Füsun Onur, Kuzguncuk, Istanbul. [ Links ]

Abiyeva, N. 2022. Zeitgeist of our time: Füsun Onur for the Turkish Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale. Global Art Daily, 5 September. Available: https://e-issues.globalartdaily.com/Zeitgeist-of-our-Time-Fusun-Onur-for-the-Turkish-Pavilion-at-the-59th. Accessed 10 June 2023. [ Links ]

Altunok, Ö. 2021. Bir Harikalar Diyari. Argonotlar, 25 November. Available: https://argonotlar.com/bir-harikalar-diyari. Accessed 21 March 2023. [ Links ]

Antmen, A. 2013. Kimlikli bedenler: sanat kimlik, cinsiyet. Istanbul: Sel Publishing. [ Links ]

Antmen, A. 2022. Enchanting realms, in Füsun Onur: Once upon a time..., edited by B Örer and N. Saçmazer (eds). Istanbul: IKSV; Milan: Mousse:26-43. [ Links ]

Atagök, T. 1997. A view of contemporary women artists in Turkey. n.paradoxa 2:20-25. [ Links ]

Atmaca, E. 2007. Sessiz Bir Müzigi Dinlemek. Radikal, 21 September. [ Links ]

Baykal, E. 2007. An afternoon with Füsun and ilhan Onur, in Füsun Onur: For careful eyes, edited by M Haydaroglu (ed). Istanbul: Yapi Kredi Publications:1-11. [ Links ]

Baykal, E. 2014. Füsun Onur: Through the looking glass. Istanbul: Arter. [ Links ]

Bennett, J. 2009. Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Borairi, P, Rodrigues, S. & Perlman J. 2023. Do siblings influence one another? Unpacking processes that occur during sibling conflict. Child Development, 94 (1):110-225. [ Links ]

Brehm, M. 2007. Füsun Onur: For careful eyes. Istanbul: Yapi Kredi Publications. [ Links ]

Çiçek, M. 2021. Opus II - Fantasia ve sanatin insansizlaştirilmasi. Art Unlimited, 4 October. Available: https://www.unlimitedrag.com/post/opus-ii-fantasia-ve-sanat%C4%B1n-insans%C4%B1zla%C5%9Ft%C4%B1r%C4%B1lmas%C4%B1. Accessed 21 March 2023. [ Links ]

Çoker, Ç. 1982. Füsun Onur ve Çevresel Sanati. Sanat Çevresi, 42:24-25. [ Links ]

Dastarli, E. Füsun Onur'la Buluçmak: Bir Sergi ve Sanatçisiyla Hemhâl Olmak. Artful Living. Available: https://www.artfulliving.com.tr/sanat/fusun-onur-la-bulusmak-bir-sergi-ve-sanatcisiyla-hemhl-olmak-i-191. Accessed 21 March 2023. [ Links ]

Dursun, N. 2019. The aesthetic of everyday life in the city of the context social environment: Kuzguncuk Neighborhood through the eyes of inhabitant artists. Urban Academy Journal, 12(2):270-287. [ Links ]

Hallett, F. 2022. Mice that roar: An everyday tale of determination. The New European, May 19. Available: https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/mice-that-roar/ Accessed 21 March 2023. [ Links ]

Haydaroglu, M. (ed). 2007. Füsun Onur: For careful eyes. Istanbul: Yapi Kredi Publications. [ Links ]

Haydaroglu, M. 2013. Füsun Onur. Artforum. Available: https://www.artforum.com/print/reviews/201301/fuesun-onur-38267. Accessed 30 May 2023. [ Links ]

Held, V. 2006. The ethics of care: Personal, political, and global. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

IKSV (Istanbul Kültür Sanat Vakfi). 2022. Füsun Onur'un inceliklerle dolu sanatina içeriden bir bakis. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z1i3DZs0ef8&ab_channel=%C4%B0stanbulK%C3%BClt%C3%BCrSanatVakf%C4%B1. Accessed 21 March 2023. [ Links ]

Jackson, R. J. 2020. Counterpoint. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available: https://www.britannica.com/art/counterpoint-music. Accessed 31 May 2023. [ Links ]

Mauthner, M. 2005. Distant lives, still voices: Sistering in family sociology. Sociology, 39(4):623-642. [ Links ]

Onur, F. 1967. The art object as a possible self in a possible world, publicly put forth on its own account as possibility of being. MA dissertation, Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). [ Links ]

Onur, F. 1978. Letter sent from Füsun Onur to Cengiz Çekil, 1 November 1978. SALT Research, Cengiz Çekil Archive CEKDIV432. Available: https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/50159. Accessed 21 March 2023. [ Links ]

Onur, F. 1982. Çiçekli Kontrpuan için. Istanbul: Taksim Art Gallery. [ Links ]

Onur, F. 1986. Modern Heykelin Turkiye'de Korunmasi. Hürriyet Gösteri, 66(May):95-6. [ Links ]

Onur, F. 2001. Unpublished recording of the interview with Füsun Onur, 5 December 2000, at Maçka Art Gallery. Private archive of Maçka Sanat Galerisi. [ Links ]

Onur, F. 2017. On Counterpoint with Flowers. PRÖTOCOLLUM 2016/17, 3:174-177. [ Links ]

Önal-Sagiroglu, S. 1991. Füsun Onur. Unpublished video recording. Private archive of Senay Önal-Sagiroglu. [ Links ]

Örer, B & Sasmazer, N. (eds). 2022. Füsun Onur: Once upon a time.... Istanbul: IKSV; Milan: Mousse. [ Links ]

Özayten, N. 2013. Mutevazi Bir Miras. Istanbul: SALT/Garanti Kültür AC. Available: https://saltonline.org/media/files/mtevaz-bir-miras-batda-obje-sanat.pdf. Accessed 21 March 2023. [ Links ]

Özpinar, C. 2016. Personal interview with Füsun Onur, Kuzguncuk, Istanbul. [ Links ]

Öztat, Ö. 2014. Conversation: Füsun Onur with iz Öztat. M-est, 24 July. Available: https://m-est.org/2014/07/24/conversation-fusun-onur-with-iz-oztat/. Accessed 21 March 2023. [ Links ]

Puig de la Bellacasa, M. 2017. Matters of care: Speculative ethics in more than human worlds. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Roche, J. 2001. Performing memory in "Moon in a Tree": Carolee Schneemann recollects Joseph Cornell. Art Journal, 60(4):6-15. [ Links ]

Savaç, M. 2008. Kuzguncuk'ta Dünya Limani. Habervesaire, 3 May. Available: https://www.habervesaire.com/kuzguncuk-ta-dunya-limani/. Accessed 21 March 2023. [ Links ]

Sönmez, N. 2022. YEL, TOZ, PORTRELER: ilhan Onur. Art Unlimited. Available: https://www.unlimitedrag.com/post/yel-toz-portreler-ilhan-onur. Accessed 21 March 2023. [ Links ]

Yilmaz, AN. 2008. Türk Heykelinde Bir Öncü Sanatçi: Füsun Onur. Gazi Sanat Tasarim, 1(2):203-221. [ Links ]