Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a18

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Joanna Rajkowskas Rhizopolis (2021): A rhizomatic refugium for caring commons

Basia Sliwinska

Researcher, Instituto de História da Arte (History of Art Institute), Universidad Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal. bsliwinska@fcsh.unl.pt (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4428-567X)

ABSTRACT

Thinking with Joanna Rajkowska's project Rhizopolis (2021), conceived as an underground habitat for species that survived a series of cataclysms, this essay reimagines the home as a collective space for communities of care, generative of accountability, co-dependencies, and co-responsibilities. The installation created from tree stumps and their roots is a futuristic scenography for a non-existent science fiction film. It invites reflection on if and how interspecies symbiotic bonds can be fostered to account for co-nutrition, co-growth and co-existence for all bodies-human, non-human and other-than-human. Within the overarching framework of ethics of care and feminist new materialist discourse foregrounding co-existence and making entanglements, the essay engages with Rhizopolis to interrogate an alternative domestic space. Does Rajkowska offer us a model for a communal transspecies refugium guided by love, care, and respect? The artist's hypothetical scenario has transformative potential, imagining a home hospitable to all bodies post Anthropocene.

Keywords: contemporary art, home, ethics of care, refugia, environmental justice, new materialism.

Introduction

'WATCH PIECE I: Watch a hundred-year-old tree breathe. Thank the tree in your mind for showing us how to grow and stay,' wrote Yoko Ono on 9th December 2012 on Instagram, as part of her 100 Acorns interactive digitally shared project (@100acorns 2012).1 The post was accompanied by a delicate dot drawing of tree roots, as though floating in space while reaching further down. This simple gesture was intended to invite a deep and attentive reflection.

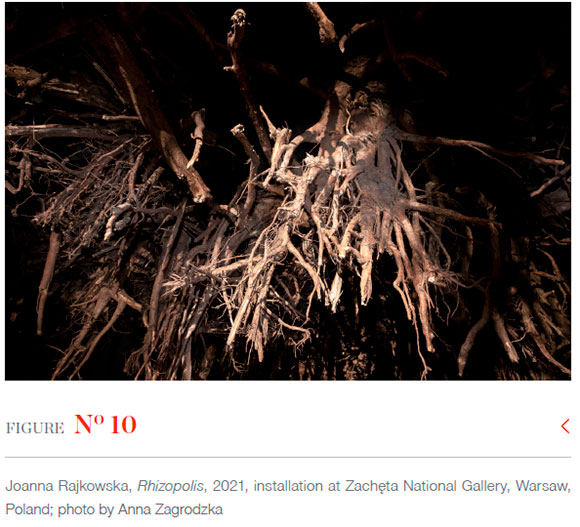

Like Ono, Joanna Rajkowska, a Polish artist working across diverse media and materialities, imagines a future habitat on earth, but unlike Ono, Rajkowska does not provide conceptual instructions for reflection. Instead, she invites us to immerse ourselves in an environment created from tree stumps and their roots, a futuristic scenography for a non-existent science fiction film. Rhizopolis (2021), a set design she built for display at Zacheta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw, Poland, was conceived as an underground shelter for surviving species of a series of envisioned cataclysms.2 Life on the earth's surface is no longer possible through which we co-imagine a potential future and an alternative habitat generating caring co-dependencies within our planetary multispecies community.

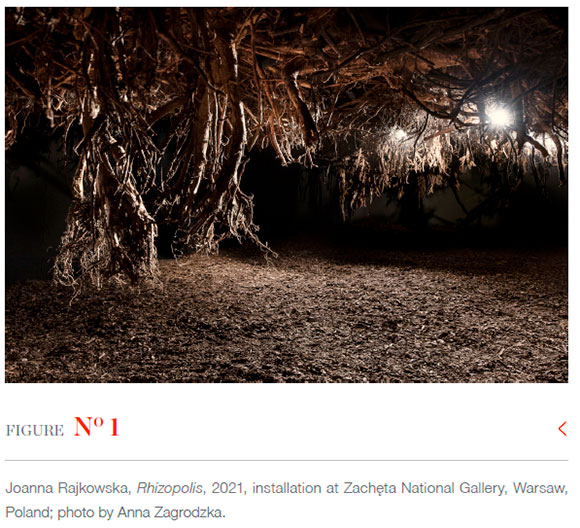

This text is an invitation to imagine with me, alongside Rhizopolis (see Figure 1).3We enter a dark, quiet space hugging the body. It feels moist, and the pungent aroma of a forest affects us: the air is humid and smells a little of damp earth, resin, and decaying wood as we wander beneath 250 hovering tree stumps; organs of trees invisible to human persons. The bark softens with each step. Above, multiple roots are acting as a safety net holding the soil. Despite the disturbing weight of trees hanging above our heads, entering this tender, immersive multisensorial space that caresses the body is comforting. It feels like a 'home', or a refugium, which Chambers Dictionary (2023) defines as isolated areas with stable climatic and other environmental conditions that are a haven for flora and fauna, sustaining and allowing the expansion of biodiversity. Rajkowska's subterranean Rhizopolis imagines a refugium for all bodies (human and other-than-human, meaning plants, animal species and other forms of life) unable to inhabit earth's surface. It is a hypothetical model for another habitat emerging from the traumas of capitalist growth's effects on the earth's ecology.

Described by the artist as 'a city of roots, located in the rhizosphere' (Rajkowska 2021), the title of the work references the zone of a root system, the rhizosphere. The term, devised by Lorenz Hitner in 1904 (derived from the Greek 'rhizo' meaning root), described the unseen area around the root inhabited by a unique population of microorganisms. Later, it was refined to differentiate three zones based on proximity to the root and the chemical, biological and physical properties occurring along and around the roots (McNear 2013).

With Rhizopolis, the artist imagines a radical event marking the end of the Anthropocene, the geological epoch characterised by significant violent and destructive actions by humans that have endangered the earth's ecosystems and biodiversity. Humans are refugees, uprooted and dispossessed, seeking shelter and sanctuary underground and dependent for their own species' survival on the tree roots providing nutrition and water. Donna Haraway's (2016) approach to think with, encouraging kinships and alliances towards transformative connections, and creating new patterns of feeling and action, is generative of new interpretative possibilities when applied to analysing artworks. This text is an attempt at thinking with the artist and writing with the Rhizopolis project to experience co-imagining, and articulate thinking with care to consider Rhizopolis as a post-Anthropocene, alternative domestic space hospitable and habitable to and for all bodies.

The Care Collective, in The Care Manifesto (2020:45), proposes four core features to create caring communities-'mutual support, public space, shared resources and local democracy.' These are deployed in this article to consider how Rhizopolis is thought with and through to imagine a potential communal space guided by feminist care fostering attentive relationships. Rhizopolis may be seen as an attempt at a caring habitat. Rajkowska acknowledges diverse vulnerabilities and dependencies, inviting reflection to be accountable and co-responsible. MarTa Puig de la Bellacasa (2017:5) frames care as 'a collective work of maintenance, with ethical and affective implications' and 'a vital politics in interdependent worlds'. This article contributes to the ongoing questioning of the notion of home from a feminist new materialist and care ethics perspective, and specifically through Rajkowska's Rhizopolis. The artist's project engages the anthropogenic story of destruction in the name of human progress to explore substitutes for co-habitation for all bodies and all matter and their relating. The artist's imaginary underground habitat is founded in co-emergence, co-constitution and co-recognition, and feminist ethics prioritising inquiry, genuine curiosity, nourishing and becoming with others. The interactions with the agency of trees that Rajkowska facilitates are attempts to explore communal reciprocity, fostering cooperative and compassionate communities of resistance to nature/culture separations through communication across differences. This enables bodies to emerge together with/in respect and in recognition of their companion species.

Mutual support: Frictions of the rhizosphere

The Care Collective (2020:45) argues mutual support is key for caring communities. Encouraging visitors to wander underneath the tree stumps, Rajkowska's project forces the visitors to become attentive. Wandering in almost complete darkness is not easy. Physical contact with the stumps encourages careful and caring encounters; one has to be mindful of the uneven flooring, and the hanging roots sometimes force one to bow. The generated affects are Rajkowska's intimate activist gesture in response to the disastrous effects of logging on biodiversity. While selective, responsible logging can contribute positively to nutrient cycling, decomposition, and soil carbon stocks, the artist directly references the state-sanctioned deforestation in Poland, threatening biodiversity collapse. Excessive felling disrupts essential ecological processes (Shiva 1988:6,7), and yet large-scale logging was approved by the Polish ruling party, Prawo i Sprawiedliwosc (PiS; Law and Justice), in 2016 in Biatowieza Forest, which is one of the European largest surviving primaeval forests. PiS political agenda enabled a significant destruction of an indigenous ecosystem, a home to unique flora and fauna. Later, in 2017, the Polish Nature Conservation Act was revised. The then Environment Minister Jan Szyszko introduced a change allowing trees to be cut down on private property, excluding commercial operations and nature monuments, without any obligation to report. This liberalisation of the law, known as Lex Szyszko, resulted in unexpected massive urban felling.4 The atrocious activities of the Polish right-wing government led to a massacre of trees.

Rhizopolis portraying the remnants of post-apocalypse seems no longer fictitious. No trees were cut down for the installation created from excavated stumps. For over a year, Rajkowska and Urszula Zajaczkowska, a botanist and author of books including Patyki, badyle (Sticks, stems, 2019), visited logging fields in predominantly pine forests. Stumps of coniferous trees turned out to be monumental; too long and heavy for the installation envisaged for Zacheta. Hence, roots of younger trees were used, sourced from a dump nearby Warsaw for roots cleared from construction sites (see Figure 2). Rajkowska salvaged stumps from being chipped and burnt down in furnaces to create a space of co-nutrition and co-habitat.

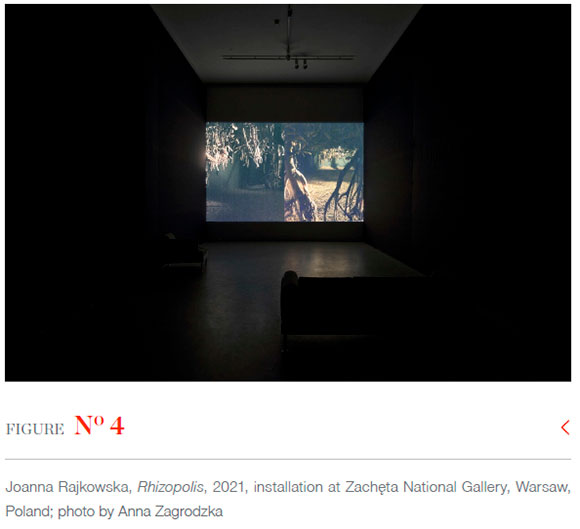

Visiting logging sites and observing large swathes of forests being destroyed, Rajkowska watched the lethal impact of humankind's intervention into the biosphere. She noticed tree stumps for the first time when she was visiting a health centre in Podbielsko (see Figure 3). Their extraordinary sculptural forms reminded her of human persons revealing their intimate side; the roots are usually invisible. This period of travelling across Poland and encountering stumps is documented via numerous sketches. Rajkowska (2023) told me she explored ways in which to intertwine the inseparable human and non-human stories into one sensing organism, a shelter for survival for all bodies. Observing vast piles of dead trees, she envisaged the underground as a refugium of last resort. Attending to intimacy and materiality of the roots and their affects, Rajkowska's Rhizopolis offers us a first-hand experience of the possible effects and affects of climate change and anthropogenic activity upon the Planet. It generates a new modality of seeing, encouraging a view from underneath the ground, and stimulates a new sensibility fostering care, attentive to the frictions happening, and the affective interactions that emerge. Rhizopolis manifests olfactory, haptic, visual, and sensorial affects generative of important relationships. The smell and texture of the roots motivate performative intimate encounters. Images of those entering Rhizopolis are captured by two cameras installed among the roots and projected in an adjacent room, side by side and with a delay, which enables visitors to observe themselves wandering underneath the roots, getting lost, moving slowly through the darkness, slightly intoxicated with the woody smells (see Figure 4).

Rajkowska's intricately, patiently and attentively constructed Rhizopolis is a space of experimentation and intimate encounters, encouraging its audience and potential future inhabitants to immerse themselves in a post-apocalyptic environment to question alternative scenarios for habitable futures. Two interwoven registers are embedded within Rhizopolis: the first is a scenography for a non-existent film, which provides a conceptual basis for the latter, the art installation, a physical space absorbing its visitors. This suggests Rajkowska is interested in exploring boundaries and discursively constructed dichotomous pre-constituted separations, in particular between nature and culture, which Rhizopolis resists. Vandana Shiva and Kartikey Shiva (2020:26) write,

The denial of self-organisation, intelligence, creativity, freedom, potential, autopoietic evolution and nonseparability in nature and society is the basis of the domination, exploitation and colonisation, enslavement and extraction, of nature and diverse cultures, of women and indigenous people, of farmers and workers through brute power and violence. The result is an ecological crisis.

Further, Shiva and Shiva (2020:131) suggest that 'the planetary freedom movement' will grow from the bottom up, interconnected and self-organised. The separation between nature and culture is a gendering apparatus foregrounding the latter, associated with the male, as superior. The female, intimately connected to nature, is positioned as inferior, together with other vulnerable, exploited and colonised bodies Shiva and Shiva write about. Rajkowska imagines a space governed by mutual horizontal dependency and support. The environment she constructed offers a shelter. Rhizopolis is a refugium, a survival, a rescue, a saviour. It concerns the loss of belonging and a complete and utter resignification and reorganisation of domesticity. The divisions between the public and the private spheres (associated with domesticity and femininity) are collapsed-there is no human-orchestrated superiority. Rhizopolis encourages us to think of home and community. Mohanty (2003:85) reminds us that the 'pursuit of safe places and ever-narrower conceptions of community relies on unexamined notions of home, family, and nation.' This generates a different understanding of a community. While Mohanty unsettles diverse 'homes' within feminism from the position of personal histories complicating sexual, racial, and ethnic identities, Rajkowska approaches the notion of home from a feminist new materialist perspective, working across materialities and their affects.

Rhizopolis interrogates the relations between all bodies beyond heteropatriarchal hierarchical accounts of human superiority. The figure of the tree, or more specifically, its root, is given agency. From the project's early stages, the artist invited Zajaczkowska, researching anatomy, bio- and aerodynamics and movement of plants, to consult. Her unique sensibility to and knowledge of trees were essential to the project. Zajaczkowska advised on the location of logging sites, helped search for the stumps, and shared her knowledge of the lives of trees. In Rhizopolis the roots of trees create a habitable space, negotiating dependencies, controlling the habitat, its temperature and humidity, and offering nutrition, water, and food. Each of the roots used for the installation has a distinct smell, and creates its own microenvironment with individual humidity, which the visitors can sense. Over the course of the exhibition, those diverse environments are subject to changes. The roots rot, the bark softens, and the air is filled with mould. The project engages with across-bodily affiliations to question our interactions with/in space(s) and our responsibilities and response-abilities towards other bodies, including plants.

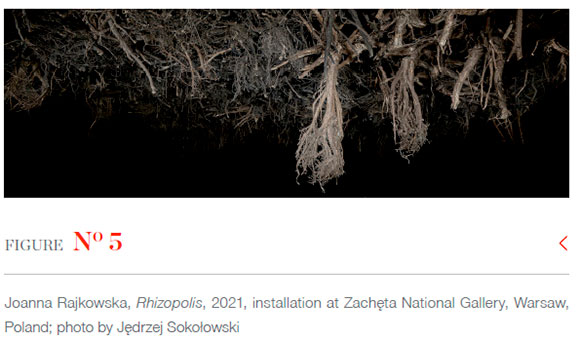

Robert Yerachmiel Sniderman (2021), writing alongside Rhizopolis, says, 'Rhizopolis the exhibition is an echo or a source of Rhizopolis the city.' He explains that Rhizopolis, the exhibition, 'brings tree roots, from annihilated forests surrounding the city of Warsaw (and so surrounding Rhizopolis), to the people of Rhizopolis', a city that is in the future. Rhizopolis is a proxy for the space of and around Warsaw and the not-so-distant any city on earth after an imagined by the artist cataclysm. Sniderman (2021) writes that it is 'a sunless refuge for exiles from anthropogenic catastrophe. [...] Rhizopolis is a city in your imagination. Rhizopolis is a potentiality in your imagination.' Imagination is important here. Rajkowska's installation is a testing and experimental underground. Its building required physical, hard labour, structural engineering, and intricate calculations of surface pressure. Special equipment was needed to lift the stumps suspended on steel cables attached to an aluminium free-standing scaffolding erected in the gallery space. To make the stumps lighter, they were aired, washed, and dried in temperatures up to 70 degrees Celsius. Before the installation, Rajkowska created a series of technical drawings, attempting to visually systematise the roots. Covering the walls with a black fabric gave an illusion of darkness. The stumps were strategically illuminated by point sources of light carefully located to negotiate their sculptural forms, softness and plumosity (see Figure 5).

Sniderman's reading of Rajkowska's vision of a future could be extended and thought alongside Anna L. Tsing's notion of friction, describing meaningful conflict enabling unexpected alliances to emerge out of destruction. Friction is a way of thinking with. It refers to encounters across differences, encouraging thinking across global interactions and informing what we know as culture. Tsing (2005:4) argues, '[C]ultures are continually co-produced in the interactions I call "friction": the awkward, unequal, unstable, and creative qualities of interconnection across difference.' The metaphor of friction enables new arrangements of culture and power out of unequal encounters generated from 'modern' global connections. Friction is a figure of resistance and creative potential. The interdependencies associated with friction can be observed in Rhizopolis. Tsing's things that rub against each other remind me of bodies of humans, plants, and other matter, interacting in the installation space to form new alliances and undo formations of power founded in nature/culture binary. Friction foregrounding difference arises from what Tsing describes as assemblages, referring to an ecological term alluding to 'all the plants, soils and other things that just happen to be in a particular place' (Tsing, quoted in Eastham 2021). These assemblages are physically created by Rajkowska, who employs roots to force us to consider relationships that are not predetermined but are formed and become, and the effects that rubbing things up against each other have to foster new sensibilities grounded in caring relationships.

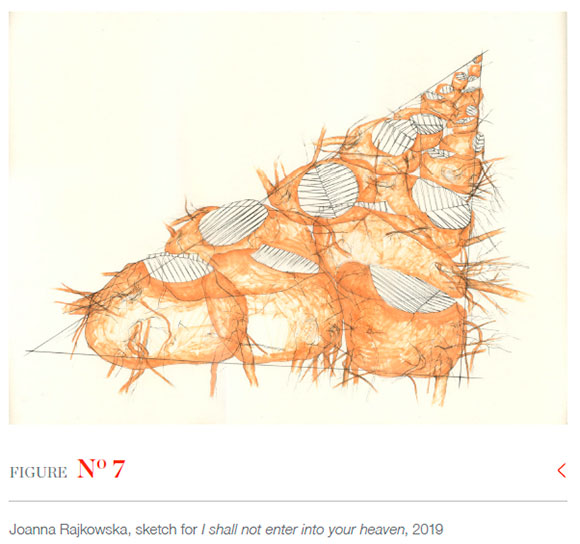

Public space: Uprootings and violations

Before conceiving Rhizopolis the artist worked on another public project, I shall not enter into your heaven (2017), a wall created in Lublin from 22 tree roots, collected from logging fields, stacked in six joined columns (see Figure 6). The installation reflected the painful and traumatic experience of visiting the logging sites in Poland (see Figure 7). Initially, Rajkowska thought about a stack of stumps to counter a modernist monument, specifically Constantin Brâncusi's wooden columns (Endless Column, version 1, created in 1918). Finally, she decided upon a barricade installed in a densely built-up area near Teatr Powszechny in Lublin. With time, she learnt to recognise individual trees, and know their shapes and smells (Rajkowska 2023). They were no longer objects to build from but persons, each with a distinct energy, to build with.

Rajkowska's wall, which could be approached as a materialised act of care and a counter-monument or an act of mourning, raises issues concerned with the uprooting of bodies, in this case, of trees, which are critical to human survival. We cannot live without the trees; they supply oxygen and help clean the air. The root system of trees is responsible for their communication and sharing of nutrients. It facilitates learning and memory connecting one tree's life to its companions in the forest, including other trees, plants, microorganisms, and animals. The root system embodies the idea of thinking with, being a connecting tissue generative of mutually beneficial symbiotic relationships. Yet, it is annihilated. Rajkowska (2017) writes, '[M]any women [...] have reported that this [the logging] felt as if a violent physical act had been committed against them, as if someone had cut off their legs.'

Resisting the continuance of the nature/culture dichotomy, the artist reimagines the oppressive woman-nature connection as a politically purposeful strategy and a feminist artistic practice. A figure of the witch as a threat to patriarchal and capitalist order comes to mind. On one hand, the witch figure reveals connections between witch-hunting and contemporary practices of land enclosure and privatisation (also marked by excessive logging) realigning social priorities, as Silvia Federici (2018) argued. On the other hand, it exposes the state's control over women's bodies, and in particular, their sexual and reproductive self-determination. European witch-hunts were engineered to implement and consolidate capitalist social, domestic and labour conditions, monetary economy, and state control of women's bodies. They aimed to disintegrate communal subsistence-oriented economies driven by noncapitalist use of natural resources. Sniderman (2021) writes, 'the violent stigmatization and eradication of women who refuse capitalist notions of wealth, of security, and of the future', continues. Federici (2018:59) cites an example of post-war Mozambique, where older women practised subsistence farming in rural areas and refused to sell the land or trees they had inherited. Shiva (1988:58) writes about indigenous practices maximising processes of forest renewal, knowledge of which is passed between generations. She (1988:204) emphasises that women's work with nature provides alternatives to western patriarchal traditions not only of land management but also healthcare.

The complex connections between economy, nature, and culture are addressed by Rajkowska, who, through the materialisation of care and acknowledging the agency of trees and their roots, constructs a sense of solidarity across time and space to emphasise the transhistorical optic and collapse the distinctions between the private and the public; hence rethinking what spaces are accessible and to whom. Sniderman (2021) makes connections between the perpetuity of violence against women's bodies and the destruction of trees in Poland, arguing that this is witnessed by I shall not enter into your heaven and Rhizopolis. Moreover, Rajkowska resists patriarchal power and control over vulnerable bodies (of trees or women), specifically through the figure of a rhizome, a root structure expanding in unexpected and manifold directions, with no centre, and often operating in spatial margins. A rhizome, in botany, has roots and shoots, enabling plants to grow down in and up through the ground. Metaphorically, this spatial concept fosters interconnectedness with no origin or boundaries. Tsing's notion of friction enables rhizomatic thinking to form new arrangements governed by the politics of the rhizosphere, guided by symbiotic cross-species relationships (Tsing & Elkin 2018). While Tsing discusses ways in which we can bring ourselves into the worlds of other species to experience their social life, Rajkowska offers us an opportunity to experience the rhizosphere: to touch it, smell it, and see it in her imaginary shelter for bodies displaced and uprooted, literally, as in the case of trees, and metaphorically, as in the case of uprooted rights of women over their bodily autonomy.

There are many commonalities between the marginalisation and victimisation of women's and plant bodies and their peripheral positionings, also in terms of access to the broadly understood public sphere. I shall not enter into your heaven continued through salvaging and photographing of the dead tree roots, predominantly around Warsaw. Rajkowska worked on the project during the 2016 mass protests in Poland against another lethal proposal by PiS and The Ordo luris Institute, an extreme anti-choice Catholic fundamentalist network supported by the Roman Catholic Church, to further restrict the already ultra-conservative 1993 abortion law. In October 2020, Poland's Constitutional Tribunal ruled abortions due to severe foetal abnormalities unconstitutional. The violence against women's bodies and rights has direct connotations with violence against vegetal life. Sniderman (2021) argues that 'Rhizopolis and Rhizopolis [Warsaw] have come to exist amidst the ongoing mass uprising of women throughout Poland demanding political revolution, bodily autonomy, and a future for the planet.' Rajkowska's imagined underground habitat, prioritising the agency of trees and their roots, re-positions the notion of community away from the anthropogenic authoritative hierarchy towards a co-species communion of mutual care. Shiva and Shiva (2020:130) write that the politics of seeds, and protection of the sources of life lies in the hands of women. Rajkowska takes this seriously, advocating for change towards environmental justice. Rhizopolis, the installation, and more importantly, the recording, is a witness that pays attention to the vulnerabilities and precarities that make our (by this I mean all bodies) lives no longer liveable and our Planet (our home) inhabitable. With Rhizopolis, Rajkowska offers us a visceral act of care for and about the commons, the collective, and the community, sharing and acting together and attentively to everyday practices and social relations.

Shared resources: Communal refugia

Mutual support is necessary for caring communities, according to The Care Collective (2020:45). Rajkowska's project reimagines what the commons may be if approached through concerns related to inclusive habitable spaces, and responding to Federici's call (2019:110) to 'reorganize and socialize domestic work, and thereby the home and the neighbourhood, through collective housekeeping.' And further, '[I]f the house is the oikos on which the economy is built, then it is women, historically the houseworkers and house prisoners, who must take the initiative to reclaim the house as a center of collective life' (Federici 2019:112). Rajkowska proposes to include all bodies into the entanglements of collective life and extend the sharing towards across species co-dependencies and co-responsibilities. She appropriates the underground forest as a domestic space, breaking the isolation of the private and the public. We are invited to co-imagine with her what this home could become, what relations could be established and how the social fabric can be reconstituted or co-constituted anew to create relations and spaces built on solidarity and communal sharing. Rhizopolis reconstructs home as commons, responding to the pressing need to survive in a world that is becoming increasingly unliveable.

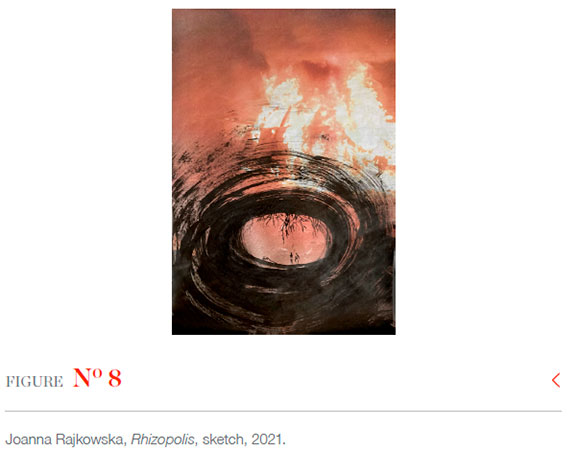

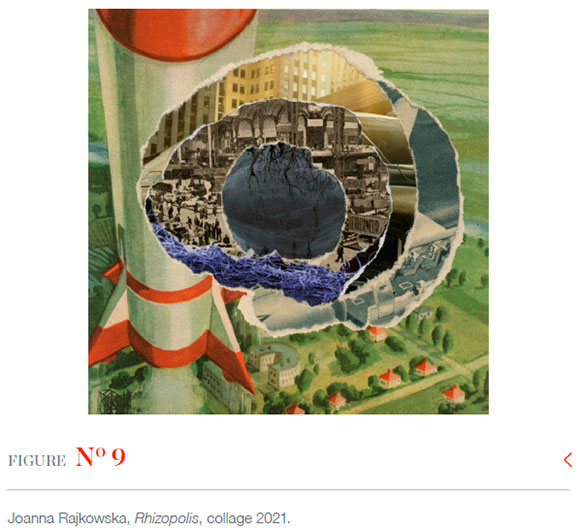

Federici (2019:77) explores the challenges of constructing the new commons, and the potential of communal relations to transform subjectivities and reorganise the world as a source of knowledges. And, while Federici writes about living the commons, Rajkowska practices it, imagining a dwelling, not on, as Federici proposes, but underneath as home, against capitalist narratives encouraging occupying, possessing, or extracting spaces. Rhizopolis imagines an alternative to the state, the market, and neoliberal subordination of life and knowledge to anthropocentric values and the patriarchal economy. The process of working on Rhizopolis revealed the potential of the project (Rajkowska 2023). The meanings that the installation generates are negotiated in the series of sketches and collages made in 2020, after the installation in Zacheta (see Figure 8). The collages are made from newspapers found between the walls of Rajkowska's studio in Warsaw and probably used as an insulation material. The language of the articles, predominantly from 1953-1954, focuses on humankind, progress, and the need to fight the dark forces of nature. Combative, militant language communicates faith in an ideal anthropocentric world. Rajkowska assembles these messages into an intricate web of meanings, unravelling the modernist vision of progress orchestrated by humankind. At the centre of one of the collages (see Figure 9) is Rhizopolis-her proposal for an alternative intertwined organisation of life.

The imagined space no longer seems speculative and distant in the context of the pandemic and the brutal attack of Russia on Ukraine.5 Rhizopolis generates a scenario for survival in the face of a collapse of a world. Rajkowska says Rhizopolis is a stage, an installation and a complex network of connections in the biosphere offering survival. The artist explains that, although difficult to visualise, it is her proposal for a 'radical dependence', in which nature is no longer dominated by humans and transpires to be a kind and generous refugium sustaining its predators, us (in Zajaczkowska & Rajkowska 2021). In ecological literature, refugia are articulated in the context of climate crisis as areas relatively buffered from climate change.

For humans, those protective pockets of life are constructed in diverse architectural shapes, as shelters, often distancing human bodies from other forms of life. These artificial sanctuaries are precarious, and their anthropocentric positionings repeat models of exploitation, uncaring structures and systems sustaining them. They occur to sustain power structures and control over the living. What if another set of relations could be established within those habitats? Haraway and Tsing explore refugia enabling survival but also having a regenerative potential. Haraway (2015:160) writes, '[R]ight now, the earth is full of refugees, human and not, without refuge.' She cites Tsing's observation on places of refuge existing in the initial phase of the Anthropocene 'to sustain reworlding in rich cultural and biological diversity.' The Anthropocene is destructive, leading to discontinuities. Haraway proposes cultivating ways of life that reconstitute refugia against the destructive impact of human activity on the Planet. This should be achieved by communal joining of forces she calls 'making kins' and would lead to a re-composition of existing biological, cultural, political and technological frameworks towards 'multispecies ecojustice' (Haraway 2015:161). Haraway's call to 'make-with-become-with, compose-with-the earth-bound', is activated by Rajkowska in the way she makes and thinks with the trees. This extends into my thinking and writing with her and Rhizopolis, encouraging others to practise with it.

Refugia as 'a Becoming Autonomous Zone', and a space of experimental action and learning, was conceptualised by subRosa (2002), a cyberfeminist art collective. While subRosa addresses predominantly the intersections between digital culture, technology, biopolitics, and reproductive health, their proposal for refugia as adaptable commons, and 'a space for convivial tinkering' may be read alongside Rajkowska's project encouraging what subRosa (2002) describes as 'wildlings' and 'unseemly sproutings', 'a commonwealth in which common law rules.' The manifesto intertwines diverse bodies, specifically making kins between female and vegetal bodies. I imagine such inter-species refugium as Rhizopolis, a tactical action providing us with an asylum towards healing. The rhizomatic structure encourages negotiating interdependencies and interconnections to critique unsustainable neoliberal and late capitalist structures, making lives unliveable. It is Rajkowska's call for collectivity and an alternative multispecies home.

Rajkowska's work practices the commons. Her projects intersect with one another, offering the audience alternative scenarios for a future that is founded upon vibrant diversities. Rhizopolis in particular, but also other projects such as Oxygenator (2007), Trafostation (2016), I shall not enter into your heaven (2017), or Solstice (2018) could be thought along Shiva and Shiva's (2020:14,15) proposal for oneness, 'the very source of our existence, our interconnectedness with the universe, with all beings (including human beings), and with our local communities.' They acknowledge rich diversities to argue that 'our freedom, as humans and as members of the earth community, is not separable from the freedom of the earth' (Shiva & Shiva 2022:14,15). Rajkowska is attentive to varied ecosystems and communities that became separated through the modernist project. She attempts to encourage attentiveness and caring. Learning from the plants, embodied experiences, senses, and the soil, she gives agency to all bodies and matter, specifically to trees, their roots, and women. This is to circumvent modernist and extractive capitalist practices, such as those concerned with the production of botanical knowledge (see Figure 10). Shiva and Shiva (2020:15) write that '[T]rees create the conditions for our freedom', providing us with oxygen. The mycorrhizal fungi in the soil nourish other bodies and derive nourishment from them. Rhizopolis negotiates those dependencies in a post-apocalyptic scenario, in which the bodies of trees and the soil their roots hug, are our only chance for survival.

Local democracy: Habitats of care. With love.

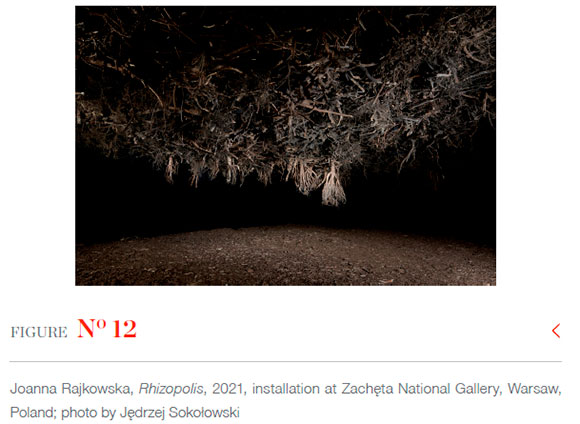

Shiva and Shiva (2020:15) write about interconnectedness in the context of care, 'for our seeds, our soil, our air, and our water'. According to them, '[W]e are living in the age of the sixth extinction; this is the moment where we need to rejuvenate biodiversity on our farms and in our fields, in our kitchens and on our plates.' Their attentiveness to the immediate environment aligns with The Care Collective (2020) proposition that local democracy is critical for caring communities. This also resonates with Rajkowska's approach in Rhizopolis, who researched local forests to frame the project in the local ecology destroyed by state-sanctioned logging. She calls for our attention. The environment she built, connecting what can be encountered on the surface of the earth with what is often neglected underground, enables visitors to immerse themselves, touch the delicate root hairs and inhale the smell of the soil and the rotten leaves. The proximity of the matter offers intimacy needed to look closely and notice. An intricately constructed woven-like structure, a web of rhizomes, hovers, discreetly illuminated to give just enough light to caress the skins of cascading woody roots and reveal to us their delicate texture (see Figure 11). Shiva and Shiva (202:22) suggest,

From the trees we learn unconditional love and unconditional giving. From the dry leaves that fall we learn about the cycle of life, the law of return, as leaves become humus and soil, protecting the earth, recycling nutrition and water, recharging springs, wells and streams.

Rajkowska's installation makes me think of bell hooks' (2001:5) proposal that love is a combination of various ingredients, 'care, affection, recognition, respect, commitment, and trust, as well as honest and open communication.' hooks' conception of love suggests a radical alternative economy fostering accountability, solidarity, co-dependencies and co-responsibilities driven by feminist ethics of care. Such positioning of love disrupting neoliberal and late-capitalist discourse, and prioritising the individual beyond the collective, may prove useful when revisiting the concept of home and its potential to become a refugium inhabited by communities of care. Thinking with Rhizopolis, I begin wondering how we can reimagine the home as a collective space with/in which 'we' encompasses all bodies? How could it foster interspecies symbiotic bonds accounting for co-nutrition, co-growth and co-existence for all? Does Rajkowska's Rhizopolis offer us a model for a communal refugium guided by love in hooks' understanding?

At the very beginning of a conversation with Zajaczkowska (2021), Rajkowska asks, '[W]hat happens when a forest dies?', adding that watching the violence perpetrated against the trees hurt her. Zajaczkowska responds (in Zajaczkowska & Rajkowska 2021),

A tree is not just wood on a trunk, but a definite, complex being, an organism with a life history much longer than ours. [...] Its body, despite being woody, hides living cells - very delicate pith cells. When you break off a branch, that is what you are breaking.

Zajaczkowska disagrees with arguments that plants don't feel anything. She explains that they feel differently, and the death of a forest is the death of its trees and its micro-world, including its many inhabitants. Zajaczkowska suggests we first need to notice them to coexist with other organisms (Zajaczkowska & Rajkowska 2021). We should get to know and encounter the plants, birds, mammals, rivers and clouds, rains and winds. We need to pay attention to what is visible to us, and what remains hidden underground, as in the case of plants. As Tronto (1993) argues, we must care for and about, to generate matter-based reciprocity and not transactional exchanges, regarding those who co-habit the earth with us. Rajkowska's Rhizopolis posits attentiveness to the needs of co-habitants and support to one another as a lesson in caring. Zajaczkowska explains that roots are 'a wild spreading of plants', literally rooting the plant but also acting as its tentacular sensors; their tips have hydrated cells, root hairs, sensing the environment. The roots enter into relations with other organisms and carry water to feed the plant; they create their immediate surroundings, a microworld with its own life-rich ecosystem-soil. Zajaczkowska emphasises this 'is where the most vibrant life on our planet can be found [... ] there can be a million beings in one gram of soil' (Zajaczkowska & Rajkowska 2021). A better understanding of the biogeochemical processes happening in soil and the rhizosphere is critical for maintaining the health of the earth (McNear 2013). Yet, roots are invisible to us, and most often disrespected. Rhizopolis is an opportunity for an intimate encounter with roots, upon which we walk every day and which, in many cases already dictate our survival being burned in a power plant to heat our radiators.

Even though it may be fictitious, the subterranean world of roots imagined by Rajkowska offers an immersive environment in which we can envision being dependent and interconnected. Most of the stumps used for the installation are of broadleaf trees, but one corner of the room is constructed from stumps of coniferous trees emanating a strong smell. All the stumps are distinct, producing their own microclimates, experienced by the visitors. This was embodied in a performance, Dark Solstice (2021) by Andrew Dixon.6 Covered with bark spread over his body, Dixon used his voice to recreate the life of a forest. He carefully selected a spot to immerse himself in Rhizopolis, distilling the energy of stumps present in the room into a range of humming, vibrating, and gently pulsating sounds.

In the era of ecological catastrophes, Tsing offers us an anthropological alternative to imagining our relationship with nature, disregarding human/ nature dichotomous divisions (in Eastham 2021). She argues that inhabited environments are full of entanglements, dependencies and alliances. The 'more-than-human-Anthropocene', and the connections across fictions of the self, nation, and species are tested via the research platform Feral Atlas (2021) she co-funded with Jennifer Deger, Alder Keleman Saxena and Feifei Zhou.7 It features field reports recognising 'feral' ecologies, initiated by human-built infrastructures and spread beyond human control'. Similarly, Rajkowska tests an imaginary scenario for an alternative habitat. Rhizopolis documents and generates symbiotic relations and other encounters between all bodies, navigating affects that the visitors embody and experience.

Sniderman (2021) calls the regenerative sustenance of Rhizopolis 'a new homeland; breathing, feeding, changing, speaking, transferring the sun'. However, he says, 'Rhizopolis is not a homeland. It might be home, but it is not a homeland', and further,

Its very name disperses its conditions of nourishment, inhabitation, solidarity, and above all of refuge and of mystery. If there is one Rhizopolis, there are many. [...] Standing in Rhizopolis, you might feel the presence of an entire transspecies political system.

Rhizopolis departs from the local, but what it reveals is applicable in a broader context, beyond the nation-state. The project attests to practices of deforestation, depletion of natural resources, and degeneration of ecology while negotiating how these practices impact on habitats. The scenario it imagines embraces the framework of feminist new materialist discourse foregrounding co-existence and making entanglements. It can be thought along Haraway's notion of 'significant otherness', imploding the artificial patriarchy-driven boundaries between nature and culture (Haraway 2003:6). Rajkowska forces us to pay attention to trees and their roots as companions to live with and think with. The multisensorial environment of Rhizopolis facilitates affects out of the encounter. While she talks about empathy and sensitivity in the context of Rhizopolis (in Zajaczkowska & Rajkowska 2021), thinking with them, I propose to focus on care, foregrounding attentiveness, noticing, and maintenance.

Rajkowska's ethics of care comes through her commitment to bear witness, and while care and witnessing are not necessarily interrelated, Rhizopolis brings them together. With Rhizopolis the artist is 'thinking care', to use Puig de la Bellacasa's (2012:197) words. Puig de la Bellacasa (2012:197) frames 'thinking care' as 'an ethical obligation and a practical labour'. Care is at the core of 'transformative feminist politics and alternative forms of organizing', she argues. Rajkowska explores ways of approaching our Planet with care-recognising violent acts destroying its biodiversity, such as felling trees, witnessing and noticing them to share their stories, and unlearning to open herself to other ways of seeing and sensing the world. The time she dedicates to her projects, giving agency to objects she works with, in the case of Rhizopolis achieved through careful placement of roots, meticulous attention to processes, and a rigorous collaborative research ethos, are framed by care.

Rhizopolis is painstakingly constructed with tenderness and kindness to trees, stumps and roots (see Figure 12). Nothing is coincidental. Rajkowska cares for and about the trees. Puig de la Bellacasa (2012:198) emphasises that caring involves 'material engagement in labours to sustain interdependent worlds, labours that are often associated with exploitation and domination'. According to Puig de la Bellacasa (2012:199), ' [A] feminist inspired vision of caring cannot be grounded in the longing for a smooth harmonious world, but in vital ethico-affective everyday practical doings that engage with the inescapable troubles of interdependent existences.' Rajkowska understands that caring depends on relationality. Her practice articulates with-thinking, learning, knowing with resisting individuation.

Conclusion

The central figure of the root in Rhizopolis is an opening to consider the notion of the commons for all species and all bodies to challenge and un-do anthropocentric positionings. Rajkowska is very practical in her approach. Giving agency to matter and enabling an immersive and intimate encounter with the roots of the trees (sometimes forcing visitors to lean or bow down under the hanging roots), she compels the audience to notice interdependent existences. Rhizopolis is her commitment to feminist ethics and the politics of care, fostering, and making kins through everyday affective encounters. Her attempt at creating an alternative habitable space interrogates what bodies matter, and which spaces are equally hospitable and habitable in a world still driven by binaries and universalisms such as the nature-culture distinctions. Rajkowska proposes a refugium founded upon mutual care and multisensorial paying attention to other species. Visitors' interactions with the smells, the humidity, the darkness, and the materiality of the roots, are based on their willingness to observe and pay attention. Rhizopolis tests what might be possible if we engage in a feminist inquiry, which, according to Haraway (2003: 7) questions, 'how worldly actors might somehow be accountable to and love each other less violently.' bell hooks, when listing the ingredients of love, also talks about engaging in healing to reconcile the worlds that have been at war. hooks (2001:76) argues that when we choose loving practice, we begin to move against domination and oppression.

Rajkowska offers us a vision with a transformative potential. Rhizopolis makes me imagine interdependencies in-between bodies and matter, nourishing the agency of all beings, and fostering interspecies relations where 'we', 'ours' and 'us' accounts for the co-nutrition, co-growth and co-existence for all. Rhizopolis is spellbinding. Rajkowska invites us to co-imagine a transspecies communal refugium welcoming all bodies in their mutual co-dependency and co-responsibility. With love. With care.

I would like to acknowledge that this work is funded by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the project [UIDP/00417/2020]

Notes

1 Announced on Yoko Ono's website Imagine Peace (2022), 100 Acorns was written for a website event in 1996, and repeated November through February 2012-2013 across Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest, and Facebook. The project was released in 2013 as a printed book Acorns.

2 The project was initially proposed for the Venice Biennale Polish Pavilion in 2019. After the exhibition at Zacheta, it was displayed at the City Gallery BWA in Bydgoszcz (2022).

3 I am grateful to the artist for her care, attention and time she shared talking to me about the project. I also thank her for generously providing the images to accompany this text.

4 Since then, as a result of public debates, the regulations have been tightened.

5 On 24 February 2022, three days after Donetsk and Luhansk were recognised by Russia as sovereign states, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, escalating the ongoing since 2014 Russo-Ukrainian War. The invasion has been widely condemned internationally by governments and intergovernmental organisations, resulting in multiple sanctions imposed on Russia.

6 The recording of the performance can be watched here: http://www.rajkowska.com/en/mroczne-przesilenie/ .

7 See https://feralatlas.org.

References

@100acorns. 2012. [O]. Available https://www.instagram.com/p/TAmFfFi26p/. Accessed 2 February 2023. [ Links ]

Chambers Dictionary. 2023. [O]. Available: https://chambers.co.uk/search/?query=refugium&title=21st. Accessed 2 February 2023. [ Links ]

Deepwell, K (ed). 2004. Feminist art manifestos. An anthology. London: KT Press. [ Links ]

Eastham, B. 2021 Anna L. Tsing on creating 'wonder in the midst of dread', interview with Anna L. Tsing, Art Review. [O]. Available: https://artreview.com/anna-l-tsing-on-creating-wonder-in-the-midst-of-dread/?fbclid=IwAR1PuGWTJJst4nIJD6MMuOxk-4PzkWDj8zzrX5gGk3i1CAV8pR5fbqb2BqE. Accessed 26 September 2022. [ Links ]

Federici, S. 2018. Witches, witch-hunting, and women. Oakland, CA: PM Press. [ Links ]

Federici, S. 2019. Re-enchanting the world. Feminism and the Politics of the commons. Oakland, CA: PM Press. [ Links ]

Haraway, D. 2003. The companion species manifesto: Dogs, people and significant otherness. Chicago, IL: Prickly Paradigm Press. [ Links ]

Haraway, D. 2015. Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making kin. Environmental Humanities, 6(1),159-165. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615934. [ Links ]

Haraway, D. 2016 Staying with the trouble. Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC, London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Haraway, D, Ishikawa, N, Gilbert, SF, Olwig, K, Tsing, AL & Bubandt, N. 2016. Anthropologists are talking - about the Anthropocene. Ethnos, 81:3:535-564. [ Links ]

hooks, b. 2001. All about love. New York, NY: Harper Collins. [ Links ]

Imagine Peace. 2022. Follow 100 Acorns. [O]. Available: https://www.imaginepeace.com/projects/100acorns. Accessed 2 February 2023. [ Links ]

McNear Jr., DH. 2013. The Rhizosphere - Roots, soil and everything in between. Nature Education Knowledge, 4(3). [O]. Available: https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/the-rhizosphere-roots-soil-and-67500617/. Accessed 2 February 2023. [ Links ]

Mohanty, ChT. 2003. Feminism without borders. Decolonizing theory, practicing solidarity. Durham, NC, London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Puig de la Bellacasa, M. 2012. Nothing comes without its world: Thinking with care. The Sociological Review, 60:2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.0207. [ Links ]

Puig de la Bellacasa, M. 2017. Matters of care. Speculative ethics in more than human worlds. Minneapolis, MN, London: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Rajkowska, J. 2017. I shall not enter into your heaven. [O]. Available: http://www.rajkowska.com/en/i-shall-not-enter-into-your-heaven/ Accessed 4 October .2022. [ Links ]

Rajkowska, J. 2021. Rhizopolis. [O]. Available: http://www.rajkowska.com/en/rhizopolis/. Accessed 4 October 2022. [ Links ]

Rajkowska, J. 2023. Personal communication. Zoom meeting on 14th March 2023. [ Links ]

Shiva, V. 1988. Staying alive: Women, ecology, and survival in India. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Shiva, V & Shiva, K. 2020. Oneness vs. the 1%: Shattering illusions, seeding freedom. London: Chelsea Green Publishing. [ Links ]

Sniderman, RY. 2021. Unitary gnawing: Seven considerations for the constituents of Rhizopolis. [O]. Available: http://www.rajkowska.com/en/unitary-gnawing-seven-considerations-for-the-constituents-of-rhizopolis/ Accessed 4 October 2022. [ Links ]

subRosa. 2004. Réfugia: Manifesto for becoming autonomous zones, in Feminist art manifestos. An anthology, edited by K Deepwell. London: KT Press. [ Links ]

The Care Collective. 2020. The Care Manifesto. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Tronto, J. 1993. Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. London, New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Tsing, AL. 2005. Friction. An ethnography of global connection. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Tsing, AL & Elkin, RS. 2018. The politics of the Rhizosphere. Interview with AL Tsing. [O]. Available: https://www.harvarddesignmagazine.org/issues/45/the-politics-of-the-rhizosphere. Accessed 25 May 2023. [ Links ]

Zajaczkowska, U & Rajkowska, J. 2021. Urszula Zajqczkowska in conversation with Joanna Rajkowska. [O]. Available: https://zacheta.art.pl/en/mediateka-i-publikacje/z-urszula-zajaczkowska-rozmawia-joanna-rajkowska. Accessed 4 October 2022. [ Links ]