Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a14

ARTICLES

Being (not) at home: Exiled women artists in postwar New York

Virginia Marano

University of Zurich & MASI, Museo d'arte della Svizzera italiana, Switzerland. virginia.marano@uzh.ch (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7348-9877)

ABSTRACT

In postwar art, the question of exile is the question of home. House defines a space as a locative concept. Home represents a place with a symbolic value of belonging and refers to objects, people, and ideas. Home does not designate a fixed state but rather a relational and transformative site in which individual and collective acts of remembering are embedded. In this article, the author explores the aesthetics of exile in the artistic production of exiled women artists in postwar New York, most notably Ruth Vollmer, Louise Nevelson, and Eva Hesse, who have often been excluded from the discourse around 1960s sculptural practice. The author casts the mode of construction and the viewing experience of their artworks through the notions of home and body. This contribution focuses on the intricate interrelations between women, domesticity, and artmaking associated with the aesthetics of exile and displacement, which significantly challenges any stable and absolute conception of home and place. By drawing on the works of feminist scholars and theorists, such as Sarah Ahmed, Julia Bryan-Wilson, and Iris Marion Young - in their argument that the idea of home and the practices of homemaking support relational identities-the author sheds light on how women artists in exile investigate notions of home, borders (both physical and psychological), diasporic longing, habitation, and uprootedness in a constant state of exchange.

Keywords: Exile, women's art, home, domesticity, diaspora, migration.

(Re)thinking exile in the feminine

In postwar art, to pose the question of exile is to pose the question of home. In light of this, I situate the notion of home within the context of the experience of exile to proceed 'differently' toward the processes of displacement inscribed within a history of feminist artmaking. In order to support this hypothesis, I embrace a more multi-layered analysis and reflect upon the interactions with materiality, fraught with psychic dimensions of trauma, to crystallise the experience of exile within the structural and phenomenological conditions of the artwork itself. The field of diaspora studies is very broad (Clifford 1994, Cohen 2008, Safran 1991, Yossi 2005, and Zvi 2003) Nevertheless, there is today a lack of scholarship about the diasporic dimension in the histories of modernism. Methodologically speaking, I focus on the expansive sculptural practice as a creative process of migration and connect the concerns of individual identities-woman and exiled-to a more collective consideration of the cultural significations of their intellectual and social networking.1

The title of this paper invokes the spatial trope of home to explore the corporeal locus of memory and knowledge. It is a rich space that cannot be fixed or abstracted but demands specificity. I commence by examining the artistic practice of Ruth Vollmer2 (1903-1982), a Jewish3 woman born in Munich who immigrated to the United States in 1935. I will then extend my investigation to encompass the artworks of two other Jewish middle-class women artists in exile: Louise Nevelson4 (18991988), who fled from the anti-Semitic violence of the Russian pogrom in Kyiv in 1905, and Eva Hesse5 (1936-1970), who escaped Nazi persecution in 1939. They were all frequent guests in the Vollmers' informal salons.6

Anchored in various cultural scenes, their practices embodied their physical and emotional struggle generated by the experience of exile. These experiences illuminated the transitory and untethered ways of being in the world, thereby interrogating and redefining traditional concepts of 'home'. In the mid- to late-1960s, they were all part of the same artistic community shaped in New York at the end of the 1950s by the gallerist Betty Parsons. In 1946, Parsons opened her eponymous gallery in New York. After the closure of Peggy Guggenheim's "Art of This Century Gallery" in 1947, Parsons inherited Guggenheim's roster of artists, championing a diverse art programme that showcased mainly women artists.

By choosing Vollmer, Nevelson, and Hesse, I do not aim to construct my hypotheses by analysing specific case studies. On the contrary, I investigate their art practices by abstracting their biographies and projecting them toward making a broader collective context that transcends questions of fixed artistic and personal identities. They had been previously assimilated into the early feminist movement but were not yet connected to the question of exile in their work. Most importantly, what brings them together is their collective making of a language to describe how exile is experienced in relation to home and belonging and how processes of 'migrating', 'homing', 'uprooting', and 'regrounding' are enacted materially, bodily, and symbolically about one another (Ahmed, Castañeda, Fortier & Sheller 2013). Theirs is a shared artistic vocabulary that allowed them, as women artists in exile, to dance between an incredible array of processes and materials. Their exploration of the body and home articulated their dislocated identity position. Focusing on the aesthetics of exile and femininity, I reconfigure the layers of complex, if not outright conflictual, meanings accreted by such material histories through 'the forming of communities that create multiple identifications through collective acts of remembering in the absence of a shared knowledge or a familiar terrain' (Ahmed 1999:331). While retracing the diverse temporalities played out across the borders that cross Vollmer's, Nevelson's, and Hesse's art practices, their experiences of exile, trauma, and displacement became sites of creative transformation toward the creation of art in exile. Such entangled experiences of postwar displacement and exilic memory shaped an aesthetic sensibility that explored new connections between materials and real life. These women artists in exile lived in New York City, seen as a site of radical experimentation, and engaged with the city in new and diverse ways while incorporating objects from the surrounding urban environment. Oscillating between the personal and political, they explored notions of mortality, vulnerability, and resistance. Such corporeal knowledge is at the heart of the recreation of their diasporic community.

The text is structured into two main parts: 'Exilic consciousness and the creation of diasporic home' and 'Living in the sculptural: Diasporic encounters at home in the works of Vollmer, Nevelson, and Hesse'. It begins with an introduction, '(Re) thinking exile in the feminine', and concludes with 'Retracing the roots of postwar art'. The first part unravels the complexity of home and exile as theoretical contexts. The second part delves into the many physical and imaginary homes interpreted and inhabited by sculptors Vollmer, Nevelson, and Hesse within the historical and political milieu of postwar New York. The initial exploration of the concept of home and exile is then followed by an in-depth analysis of Vollmer's House (1957), the Mrs. NS Palace (1964-1977) and the Dream House series (1972-1973) by Nevelson, and a selection of Hesse's later artworks (1968-1969). The conclusion re-traces the roots of postwar art, configuring home as a changing and complex reality in which exiled bodies can actively perform new representations with/in the world.

Exilic consciousness and the creation of dias-poric home

Home as female corpus and gendered interiors represents the questions of feminised domestic labor and the redefinition of a woman's role in the homeplace as a site of 'radical resistance towards the margins' (hooks 1990). By elucidating its symbolism, I situate the domestic space not only in the debate that erupted around the redefinition of housework by the women's art movement but in a much broader context linked to the sculptural strategies of displacement and the blurring of structural boundaries between interior/exterior space. I consider the diasporic space through an affective dimension and rethink home as a skin where bodies take form.7 Looking at the corporeality and women's embodied experiences of exile brings new perspectives to the understanding of female embodiment. As the Swiss artist Heidi Bucher affirmed with her performances in the late 1970s, the fragments of home can be liberated from the patriarchal past. Bucher smeared latex over the walls of her parents' house in Winterthur-Wülflingen and then peeled its skin off. Home, in this case, emerges as a site of re-interpretive preservation of personal and collective history.8 In Sarah Ahmed's (1999:30) words,

[T]he movements of selves between places that come to be inhabited as home involve the discontinuities of personal biographies and wrinkles in the skin. The experience of leaving home in migration is hence always about the failure of memory to fully make sense of the place one comes to inhabit. This failure is experienced in the discomfort of inhabiting a migrant body, a body which feels out of place, which feels uncomfortable in this place. The process of returning home is likewise about the failures of memory, of not being inhabited in the same way by that which appears as familiar.

Diasporic homemaking affects places of origin in multiple, often unexpected ways. While a house can be a place of safety, providing a protective skin shielding the private person from the public, it is, in addition, a place that silently bears witness to the occurrences within: it absorbs traces left by its inhabitants, physically storing the past as a place for memories.9 The unhomely aesthetics of contemporary art would reimagine the psychological condition wrapped inside the sociopolitical meaning of the Freudian 'uncanny'. Homi K. Bhabha (1992) further expands Freud's discussion from personal to political and posits the 'unhomely' in what he terms the 'house of fiction.' He elaborates that the site and the phenomena 'capture something of the estranging sense of the relocation of the home and the world in an unhallowed place [...]'-it is a 'shock of recognition of the world-in-the-home, the home in-the-world' (Bhabha 1992:141). Bhabha's essay, whose title is indebted to Rabindranath Tagore's (1916) novel translated as The home and the world, argues that 'in that displacement the border between home and world becomes confused; and, uncannily, the private and the public become part of each other, forcing upon us a vision that is as divided as it is disorienting' (Bhabha 1992:141).

Drawing upon the philosopher Vilém Flusser's (1984-1985) conception of the exilic experience as a transcultural form of creativity and the leading theorist of Latin American studies and language rights Marie Louise Pratt's (1991) borrowed concept of 'contact zone,' I consider exile as an alternative ground for creative acts.10 This creative force represents the potential dimension of cultural encounters between the local and the global, the old and the new home, as a site of creation for the diasporic subject.

This positive reading of exile, perceived as a 'breeding ground for creative activity, for the new' (Flusser 1984-1985:9), had been criticised by the art historian Sabine Eckmann (2013). She claimed that Flusser

conceived exile/emigration/migration without differentiation as both a creative striving and a suffering, but without using the term "isolation." He observed, "If he is not to perish, the expellee must be creative." Flusser (probably without really having read Said) adopted the latter's positive assessment of exile, the aspect of originality, and developed it further. Whereas Said's essay is simultaneously dominated by his negative assessment of exile as the experience of not belonging and of loss, Flusser saw these as positive qualities (Flusser 2013:9).

For Eckmann (2013:9), 'if not all exiles adopted a hybrid identity in one form or another, there are hardly any examples of a truly hybrid aesthetic'. She describes the different aesthetic adaptations of the exile experience due to the heterogeneous processes of artistic transfer between Europe and the United States in the 1930s and 1940s. While I disagree with Eckmann's line of interpretation, I suggest that precisely in the 'creative dialogue' between European and American art, Vollmer, Nevelson, and Hesse were able to create new articulations of exile through the experimentation with new materials and working methods. The specifically female perspective, the declaration of one's own body as a medium, inevitably exposes norms and social conditions and also becomes a form of self-empowerment. Drawing upon feminist theory and diaspora studies, it is urgent to lay out the case for a feminist intervention in exile studies through/with art. The home as the material and the symbolic and the body as a site of embodied practices determine the work of these women making art.11 Following the art historian Marsha Meskimmon, I affirm that the affective objects and spaces of women's art need to be conceived in conjunction with their historical location and material presence in the world (Meskimmon 2011). In discussing displaced women artists, a nuanced understanding of the historical contexts and the psychological mechanisms at play in the experience of exile is needed. In focusing on the boundaries between space and place, as a diaspora practice, these questions arise: What makes a home? What kinds of material and symbolic aspects define the aesthetics of exile? How can the relation between the individual consciousness of the artist and the sense of community belonging redefine artmaking as something personal and historical?

To address these issues, I ask for a shift from the traditional biographical account to the intersection of personal and global histories that can help to navigate difficult questions of identity. For example, Vollmer, Nevelson, and Hesse investigated the in-between of entangled personal memories and public history, connecting the concerns of individual identity to a collective project of communal care and self-expanding exchanges. As the feminist and political theorist, Iris Marion Young argues for the critical significance of homemaking in the articulation of histories and identities,

home carries a core positive meaning as the material anchor for a sense of agency and a shifting, fluid identity. This concept of home does not oppose the personal and the political but instead describes conditions that make the political possible (Young [1997] 2002:149).

They were interested in the notions of transformation and becoming, exploring interconnections between materiality, intimacies, and corporeal distances.

I re-enter and re-interpret the space of exile as an intimate place that allowed Vollmer, Nevelson, and Hesse to build a place of resistance toward forming a constellation of female solidarity. In line with Anne Wagner's (1994) recognition of 'another' Hesse, let me emphasise that such an orientation toward the body as a creative and political site in art foregrounds plurality and relationality as transformative structures of subjectivity.12 Following World War II, women artists embraced a hands-on approach, creating a work that responded to the specific properties of each material and showed the traces of its making. The body, which functioned as an artistic medium of resistance, carried a symbolic meaning and became a site to map the psychological anxiety brought about by political and technological developments. The female body is thereby doubled, mirrored, and fragmented. The space, specifically the domestic one, becomes one with the body's fragments in the shape of protruding nipples or test pieces that remind one of bodily organs contained in a glass pastry case (Fig. 1). The significant tropes associated with Vollmer's, Nevelson's, and Hesse's art-repetition, un-resilience, transparency, attraction/repulsion, embodied connection, transformation, and ambivalence-function as a mirror for personal and historical memories.

Living in the sculptural: Diasporic encounters at home in the work of Vollmer, Nevelson, and Hesse

Vollmer, Nevelson, and Hesse recreated a diasporic community in the United States of America in the early 1960s. They left their homeplaces in the early twentieth century and mid-1930s, and their different itineraries brought them to New York City. Rooted in multiple cultural scenes, their practices embodied their physical and emotional struggle generated by the experience of exile and the transitory and untethered ways of being in the world that throw into question the idea of 'home.' In the mid- to late-1960s, they were all part of the same artistic community that had been shaped in New York at the end of the 1950s by the gallerist Betty Parsons, who, after the closure of Peggy Guggenheim's "Art of This Century Gallery" in 1947, inherited her roster of artists, championing a diverse art program that showcased mainly women artists.

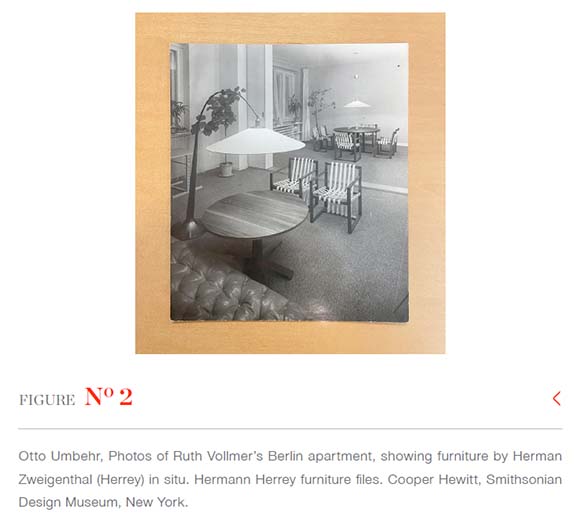

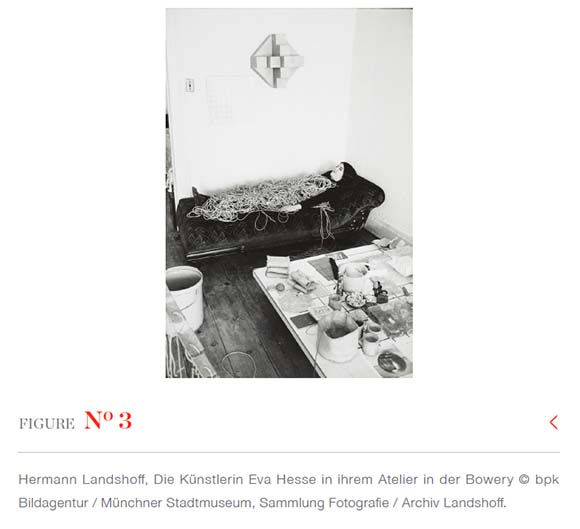

Vollmer fled Germany in 1935 and moved to New York City, settling in an apartment on 25 Central Park West with her husband Hermann Vollmer. Their new home was adorned with artworks and objects from Berlin, such as some Bauhaus-inspired furniture designed by Hermann (Zweigenthal) Herrey (Fig. 2). By the 1940s, their apartment became a meeting place for German Jewish refugees. In the 1960s, they built a circle of friends, including artists, curators, art critics, and collectors from New York. Among them were Hesse, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Smithson. In this context, Hermann Landschoff, a famous photographer and brother of Ruth Vollmer, made a few portraits of Hesse and Vollmer (Fig. 3). One of these photographs of Hesse was taken in her studio. It can be read as a testimony to the diverse and interpersonal network that enabled Vollmer to transform the isolation of exile into a cross-cultural and intergenerational exchange. Thanks to the work of critical scholars such as Anna Lovatt, it is now possible to investigate the role played by exiled women artists in the 1960s. Lovatt's essay An underground economy explores Vollmer's art collection and her modes of socialisation in the circle of exiled artists in postwar New York (Lovatt 2020).

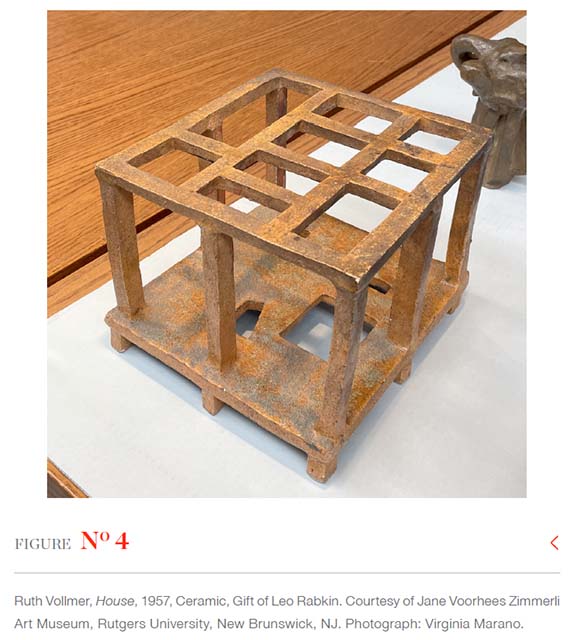

In an interview with the curator and art critic Susan Larsen (1975), Vollmer said that after seeing the vulnerable and open structure of The Palace at 4 a.m. (1932) of Alberto Giacometti, in which the fragility is retained, she built the geometrical construction titled House (1957; Fig. 4). This is one of her earliest surviving sculptures that represents her geopolitical displacement. Vollmer visited Giacometti in Paris in the early 1950s. She shared the same artistic investigation of the marginal with the Swiss sculptor, defining alternative ways of seeing and experiencing space. House moves the scenario from the familiar operation of inhabiting a home to an uncanny, even inhospitable, domestic environment.

Although it had been considered destroyed for a long time due to its fragile material, I discovered that Leo Rabkin donated House to the Zimmerli Art Museum in New Brunswick, New Jersey. It is painted blue on the back, and the inscription reads 'Ruth Vollmer. When she had a studio at the Bldg - now Alice Tully Hall Lincoln Center Bldg.' Her studio was located on Broadway at 65th Street-an unremarkable neighbourhood that later became Lincoln Centre. Vollmer's geometrical House reveals the feeling of being imprisoned between inside and outside. The fragility of its structure is also reflected in the clay material. Emptiness here represents a refugee or a prison. The geometrical object becomes the site for transformation. It can communicate emotions of either confinement or freedom. The empty and dismembered forms open multiple habitation possibilities. This geometrical object captures a transition between Vollmer's early surrealist practice and her 1960s engagement with geometrical abstraction.

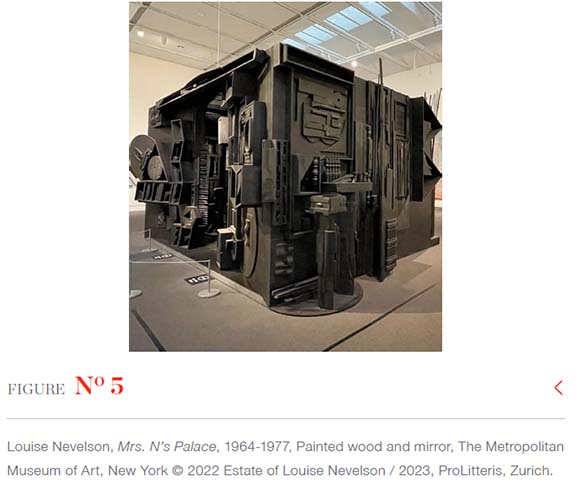

Like Vollmer with House, Nevelson dared to conjugate the personal and the historical, the symbolic and the body, through sculptural objects, in this case, found and discarded objects. Nevelson's Mrs. N's Palace (1964-1977; Fig. 5) is composed of more than one hundred interconnected fragments and represents New York, the city she described as 'her mirror,' and 'her home.' The door in Mrs. N's Palace opens to an intimate space that gives new life to the urban detritus. As in a collage, she experimented with materials using found objects, primarily bits of wood that, as a material, would powerfully contract and expand as it adjusts to different climates. Her familiarity with wood is most likely related to her family background, her father having been a woodcutter before opening a junkyard in Rockland, Maine. His work as a lumberjack impacted Nevelson's prominent use of cast-off pieces of wood.

Louise Nevelson, Mrs. N's Palace, 1964-1977, Painted wood and mirror, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York © 2022 Estate of Louise Nevelson / 2023, ProLitteris, Zurich.

In her collage works, she would combine raw pieces of wood and fragments of veneer, cardboard, sandpaper, tape, metallic foil, bits of printed paper, and newspaper, as well as scraps of paper she used as backing when she spray-painted the individual pieces of her sculpture. Nevelson considered herself a performer, devoted to the ritualistic action of collecting, containing, and protecting fragmented wood objects, such as dismantled furniture and house ornaments. Her experimentations with abstract forms and three-dimensional works brought her later to her most known monumental sculptures. The collages grasp the durational traces of the creative act. She left many elements raw and unpainted to make visible the many gates to what she called the 'fourth dimension.'

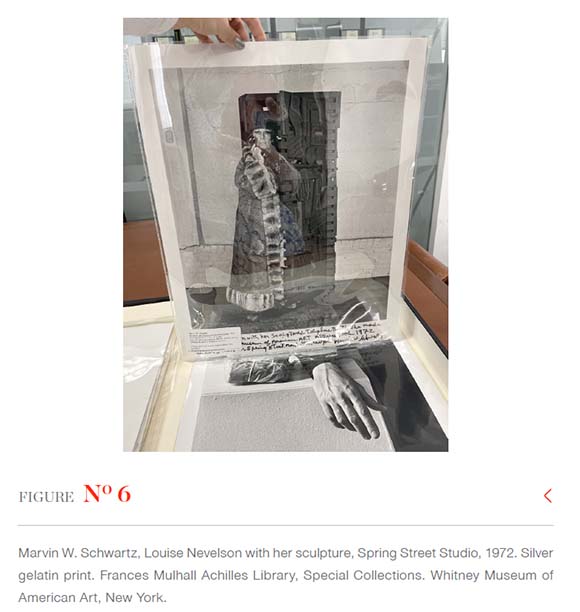

Art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson brilliantly investigates the role of Nevelson's collages within the exhibition Louise Nevelson: Persistence at Procuratie Vecchie in Piazza San Marco, Venice (23.4.2022-11.09.2022), organised as a collateral event of the 59th Biennale di Venezia The Milk of Dreams to celebrate the 60th anniversary of Nevelson's installation. In 1962, a group of Nevelson's painted wood sculptures in monochrome black, white, and gold was exhibited as an immersive installation in the American Pavilion of the 31st Biennale di Venezia, curated by Dorothy C. Miller. In the 2022 Venice exhibition curated by Wilson, the rooms show Nevelson's transformative practice, from the first small pieces of wood assembled in the free space through a modular system of accumulation to the intimately scaled Moon Spikes series and the large-scale Sky Cathedral sculptures that she would continue throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Despite her success with the larger constructions, the Dream House series, produced between 1972 and 1973, was not considered one of her most successful works (Fig. 6). Inspired by the miniature stage castle in the three-act play Tiny Alice written by Edward Albee, she began with a real doll house and eventually realised larger constructions.13 In a conversation with Louis Botto in April 1972, Nevelson was asked whether she imagined different types of people living in each of her houses. Nevelson answered:

No. I don't imagine people living in these houses, even though I think of that tall one as an apartment house. I don't mean them to be lived in. But, if an architect wanted to use this concept for an actual apartment house-that would be marvelous. Do you ever get halfway through one of them and tear it apart? No. Because I think that my way of working and the materials I use lend themselves to completion. There's very little waste in my work or in my life. When I am doing something, I aim to see it through. Even when I'm away from these houses, I think about them all the time. You see, I know the world through my work (Botto 1972:8).

Marvin W. Schwartz, Louise Nevelson with her sculpture, Spring Street Studio, 1972. Silver gelatin print. Frances Mulhall Achilles Library, Special Collections. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

As Bryan-Wilson (2017) reflects on Nevelson's politics, imagining her houses as 'complex sites of sexual secrecy and queer disclosure,' she relates the Dream House to the women's art movement of that time. Nevelson's constructions coincided with the Womanhouse's project of the California Institute of Art's Feminist Art Program under the pedagogical guidance of Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro. One of the artists, Sandy Orgel, talks about a female body segmented by shelves in a closet, surrounded by towels and sheets. Her installation offers

a vision of domesticity in which a white female body is caught between confinement and freedom, as opposed to Nevelson's evacuation of literal figures from home. Instead of presenting a sculptural representation of a body, the Dream Houses insist on activation of the viewer's body (whatever color she may be) as she is invited to peer into the openings in their walls (Bryan-Wilson 2017: 119).

Nevelson cohabitated with her sculptures, as shown by a photo taken by Marvin W. Schwartz in 1972, in which the artist is portrayed in the Dream House holding a black telephone receiver. Maria Nevelson, the artist's granddaughter, told me in a conversation that she sees in this photo a possible link with the TV show Get Smart! (Fig. 7). In the first scene of the first episode of the 1965 sitcom, viewers were introduced to secret agent Maxwell Smart's covert show telephone, which would become one of the signature running gags of the popular US television series. Nevelson brings the phone into the house to engage in a conversation between imaginary worlds and connect gaps between spaces and times. The presence of the house also underlines Nevelson's sense of playfulness as if she were not only innovatively political but also authentically fun.

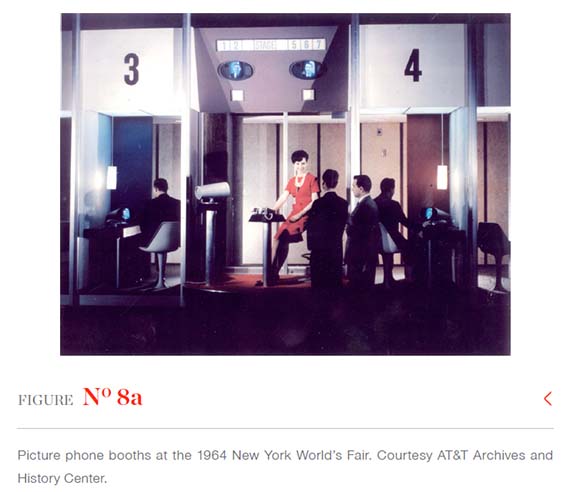

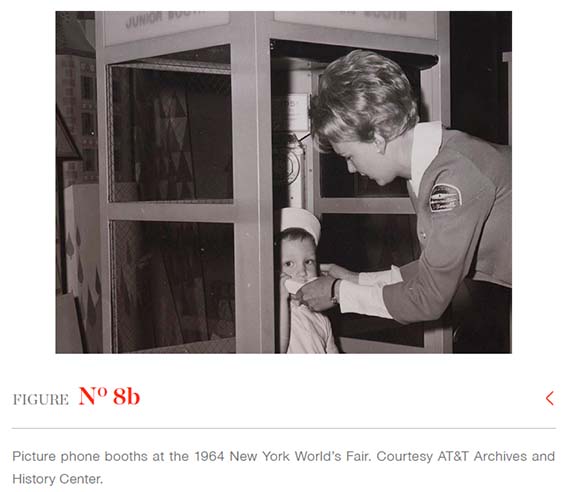

It is interesting to point out that in 1964, the picture phone service was introduced at the Bell Pavilion, part of the revolutionary New York World's Fair of that year (Fig. 8 and Fig. 8b). This representation imagined the idea of being able to talk to and view someone while they were elsewhere. The phone as a symbolic object complicates an us-here and them-there-looking opposition. In Nevelson's case, this could be an us-here in exile versus a them-there looking for a home. The relationship between the sculptural object and the beholder, and so between the environment and the viewer's experience, brings a new analysis framework.

The openings in the Dream House series raise questions about the stability of the home as a locus of fragile privacy-constantly invited to be tested, if not violated, by the viewer. What is more, the serial nature of these sculptures places them on a continuum between repeatable (coded 'feminine') chores like sorting, fixing, mending, and full-scale (coded 'masculine') construction projects, moving Nevelson's work beyond any easily gendered division of labor (Bryan-Wilson 2017:118).

Here, however, I disagree with Bryan-Wilson's queer reading of Nevelson's art practice and 'resistance to represent gender as a binary system' (2017:121). As the artist herself affirmed:

I have always felt feminine...very feminine, so feminine that I wouldn't wear slacks. I didn't like the thought, so I never did wear them. I have retained this stubborn edge. Men don't work this way, they become too affixed, too involved with the craft or technique. They wouldn't putter, so to speak, as I do with these things. The dips and cracks and detail fascinate me. My work is delicate; it may look strong but it is delicate. True strength is delicate. My whole life is in it, and my whole life is feminine, and I work from an entirely different point of view. My work is the creation of a feminine mind-there is no doubt. What I wear every day and how I comb my hair all has something to do with it. The way you live a life. And in my particular case, there was never a time that I ever wanted to be anything else. I was interested in being myself. And that is feminine. I am not very modest, I always say I built an empire (Nevelson 1972).

Drawing on Young's thinking, I want to read Nevelson's affirmation of home as the materialisation of a female identity that 'does not fix identity but anchors it in physical being that makes a continuity between past and present' (Young [1997] 2002:140). I critically turn to Martin Heidegger's reflections on building, dwelling, and thinking to reconfigure Nevelson's engagement with space and time. For him, dwelling and building are defined through a circular relation. Heidegger thinks of building as a future-oriented activity as opposed to the past-oriented work of preservation. In doing so, he embodies two aspects of building: cultivating and constructing. Notwithstanding his claims that these moments are equally significant, he privileged the creative activity of constructing, arguing that 'building in the sense of preserving and nurturing is not making anything' (Heidegger [1951] 1971:149). This privileging is, in line with Young, male-biased as women are excluded from the professions associated with building. On the contrary, this aspect of preservation played a significant role in Nevelson's artmaking. That is her practice of protecting, preserving, and caring for objects.

Even though Nevelson embraced the home as a protective site, in which she prefigures political solidarity, she shows some ambiguities similar to the destructive narrative of Martha Rosler's domestic objects. In Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful (c. 1967-1972), Rosler reveals the collective experience of war, making literal the description of the conflict as the 'living-room war.' In House Beautiful: Giacometti (c. 1967-1972), the Jewish New Yorker artist juxtaposes the bronze silhouettes of Giacometti with violent news photographs of the Vietnam War. The artist combines preexisting mass-media images from documentary (Life) and lifestyle (House Beautiful) magazines, rupturing the image of domestic comfort and interpreting home as a place of ambiguity.

In the confluent dialogue of feminism and domesticity, Nevelson pursues an aesthetic method for which objects can reactivate memories and communicate intimate histories compelled by our bond with the thing that represents our surrounding space and time. In an untitled work from 1985, Nevelson affixed a broom and a blue dustpan to a black background, leaving them as recognisable tools of the feminised labour of housework but also estranging them from their functionality in a continuous process of destruction and transfiguration. Bryan-Wilson argues for a connection with the ideas of Italian art critic Carla Lonzi within the context of a particular resonance of Nevelson's work during the emergence of Arte Povera in the 1960s. Lonzi (1962) remarked upon Nevelson's 'destruction and transfiguration process,' in which she observed a 'proliferating presence of a totally female ambiguity'.

The same ambiguity characterises Hesse's sculptures. She articulates an ambiguous feminine gaze and posits the feminine body as a site of creative energies. Following Vivian Sobchack (cited by Meskimmon 2003:20), I would argue too 'that corporeality and embodiment are also crucial concepts for exile since the body (a body) is the first "home" of the subject and the productive locus of both history and knowledge'. Hesse privileged a dimension of emergence in her work, where objects, images, and meanings are reintegrated into the corporeal. In line with these feminist insights, a critical reconsideration of the works' feminine body and material aspects provides a new account of the role of displacement in the artistic practices of exiled women artists in the historical and political context of postwar New York.

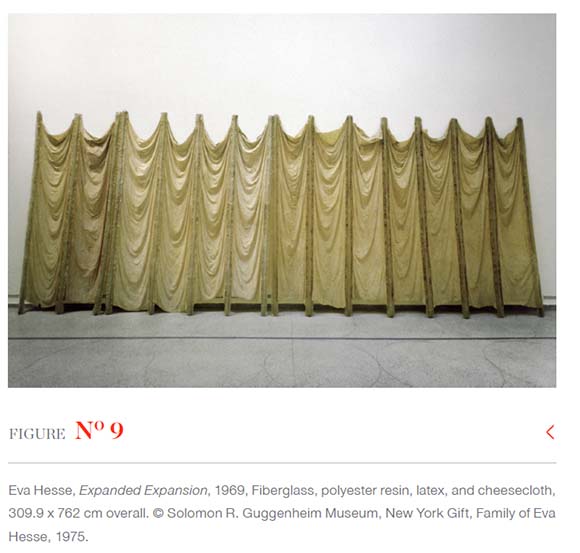

The use of wax and fibreglass (to which Hesse was drawn as a material that absorbs light and does not last) results in a product that resembles skin and leads to a new kind of sensorial experience. In Expanded Expansion14 (Fig. 9), soft drapes of rubberised cheesecloth are juxtaposed with fibreglass fabric stiffened with polyester resin. Doug Johns, her assistant, painted liquid rubber directly onto the cheesecloth lying on the floor. On its surfaces, the sign of the different applications is evident. Sheets of plastic that lay underneath the cheesecloth crinkled and distorted during the piece's fabrication, imparting a creased texture to the final structure. Once dry, the latex panels were sandwiched between rigid vertical poles. Hesse thought of the work as transformative - it can be placed on the floor or the wall. She expanded the space. Such expansion can be described as the intimate process of making.

This work is about touching. It is not about what the body is but what the body does. An intersensory interaction with the material allowed Hesse to incorporate physical marks that functioned as residual and gestural traces of existence in the works. The works encouraged viewers to physically respond to art objects and focus on their embodied experience. Hesse's works resemble skins and organs without engaging with figurative associations. What is evident is that she was able to push the boundaries of sculpture, dealing with the tension between two- and three-dimensional spaces.

Retracing the roots of postwar art

What brings Vollmer, Nevelson, and Hesse into dialogue is their shared experience of forced migration and complementary artistic journey toward experimenting with new materials. These women artists in exile lived in New York City, seen as a site of radical experimentation, and engaged with the city in new and diverse ways while incorporating objects from the surrounding urban environment, as visible in the use and reuse of nails in the collages of Nevelson. Their artworks interweave the traumatic experience of losing a home with an articulation of visual and material forms, from the fibreglass wires of Hesse's installations to Vollmer's house object made of clay, that expands our relationship to artmaking as a form of historical agency. The process art of these three artists refigured the legacies of the standard-bearers of the Minimalism and post-Minimalism movements, refusing identification with the Conceptualist anonymous seriality. They deconstructed the modernist-masculinist pursuit of uniformity and repetition by emphasising tactile properties.

Exile does not designate a fixed state but rather a constant negotiation. Such logic led Vollmer, Nevelson, and Hesse to renegotiate an interactive and fruitful dialogue between the collective and the individual. I use the notion of collectivity, referring to Jasbir K. Puar's value of 'conviviality,' as a feature of assembling that '[...] does not lead to a politics of the universal or inclusive common, nor an ethics of individuatedness, rather the futurity enabled through the open materiality of bodies as a Place to Meet' (Puar 2009:168). At home, the place of encounter par excellence, these women artists in exile proposed alternative practices of meaning-making that are less about the result and more about the processes.

Vollmer, Nevelson, and Hesse shared the same experience of displacement and a similar engagement with the space and the body as a way to project and reinterpret personal and historical traumas. Such experiences of exile and collective memory shaped their engagement with New York City, incorporating objects from the surrounding urban environment. The geometrical house of Vollmer, whose walls resemble an imaginary lost and re-found place, together with the fragments of wood that Nevelson collected, should be understood not as isolated objects but as a result of the generative dialogue within an artistic community dealing with the trauma of war and the need to rebuild a space of resistance, made of relational care webs. These postwar models provide a vital space for forging, knowing, imagining, and inhabiting a social space of solidarity. They created new spaces of knowledge and creativity that eventually grew into self-expanding constellations of female resistance. The entanglement of their female postwar mutual relationships tried to incorporate the frame by negating the margin as a limit and tending to occupy the infinite interstitial spaces between their reticular configurations. I stress this position and say that the ideal of productivity can be resisted through new knowledge systems and alternative care exchanges such as documenting and archiving. Vollmer, Nevelson, and Hesse engaged with a performative care practice oriented toward a discursive, relational, and spatial strategy that aimed to interrupt dominance relations as a matter of urgent sociological, political, and ethical concern. They performed what Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha (2018) calls 'care webs' to create transformative interconnections among displaced women in search of a shared space of effect and solidarity. Home became a moment of evolving and growing collectiveness that revealed the intricate conditions and limits of geographical and mental boundaries.

Notes

1 . Vollmer and Hesse belong to a Jewish German diaspora that not only stems from issues of identity displacement but is also deeply connected to a religious sphere. Due to wordcount limitations and the article's primary focus, an exhaustive exploration of the religious identities of the three artists is unfeasible in this context. My intention is to traverse beyond the scope of identity issues, delving into the aesthetics of exile, the exilic consciousness in postwar New York, and the building of a diasporic community in postwar New York (Levin 2005 & 2010).

2 . For insights into Ruth Vollmer's practice and experience of exile, see Lovatt (2010 & 2020).

3 . Several dated and updated monographs exist (Ofrat 1998 & Barak 2020) on individual aspects of Jewish art, yet none explore the aesthetics of exile in the works of postwar New York's exiled Jewish women artists. In her critical approach to Samantha Baskind's encyclopedic perspective (Baskind 2007) Lisa E. Bloom's Jewish Identities in American Feminist Art: Ghosts of Ethnicity (2006) delves into the unacknowledged questions of Jewish identity in the sphere of American feminist art. She introduces the term ghosts of ethnicity to describe the invisible but significant intersections between these two cultural phenomena. However, Bloom's work, highlighting artists such as Judy Chicago and Eleanor Antin, omits others like Audrey Flack and Vera Klement, and ignores the influential feminist art galleries of the era, such as Benice Steinbaum in New York or Artemisia in Chicago (Kantorovitz Carter Southard 2007).

4 . For a comprehensive understanding of Louise Nevelson's displacement experience, refer to Stanislawski (2007). On the social and political implications of Nevelson's art, see Bryan-Wilson (2023). As a queer feminist scholar, Bryan-Wilson situates Nevelson's assemblages in a broader context, connecting them with a vast range of marginalised worldmaking and emphasising the artist's oft-stated allegiance to blackness.

5 . One of the scholars/artists who explored Jewishness and trauma in the work of Eva Hesse is Vanessa Corby (2010). The artworks of Hesse have been examined through both a feminist lens and the lens of female embodiment. Key scholars in these areas include Lucy Lippard (1976), Cindy Nemser (1970), and Anne Middleton Wagner (1994). Additional insight has also been provided by Fer (1994) and Sussman (2002). I am indebted to Elisabeth Sussman for her mentorship and support throughout my research path.

6 . In light of this architectonic and metaphorical space of relation, like that of the salon, described and also criticised by Hannah Arendt (1974), Vollmer recreated her own diasporic space within the community of Jewish women refugees in postwar New York City. The 'power of private conversation' embodied in her apartment empowered Hesse's and Vollmer's creative roles in the artistic world. In an effort to relocate their body-space, they recollected memories and tied them together toward a new identity-a collective one. See Bilski and Braun (2005).

7 . In thinking of the skin as a site of memory where bodies take form, see the engaging collection of essays edited by Sarah Ahmed and Jackie Stacey (2001).

8 . Allison Weir (2008) draws on Iris Marion Young's essay "House and home: Feminist variations on a theme," and argues for a positive reading of home as a locus of values that connect past and future, through reinterpretive preservation and transformative identification.

9 . For an intimate reflection on space, see Gaston Bachelard's book entitled The poetics of space, first published in 1958.

10 . I am indebted to Helene Roth's (2021) approach to displacement and migration in the context of the exilic experience of European emigrant photographers displaced in New York. Among them is Hermann Landshoff, brother of Ruth Vollmer.

11 . The expression 'women making art' refers to Marsha Meskimmon's pivotal book Women making art: History, subjectivity, aesthetics (2003).

12 . Anne Wagner breaks down the myth created around Hesse's life and work. She chooses to focus on the context of the artist's life rather than specific, personal events. She argues that Anna Chave's feminist-oriented analysis forgets to hint at the existence of universal woman experience and that Lucy Lippard focuses too much on psychological aspects. See Wagner, "Another Hesse," and Chave, "[Response to 'Another Hesse']," October 71 (1995): 146-148.

13 . Tiny Alice is a three-act play written by Edward Albee that premiered on Broadway at the Billy Rose Theatre in 1964. Another precedent of Nevelson's series is Mattel's Barbie Dream House, which was first available for purchase in 1962. See note no. 4 in Bryan-Wilson (2017:114).

14 . The work Expanded Expansion was exhibited in the context of the exhibition Eva Hesse: Expanded Expansion, organised at the Guggenheim Museum, July 8-October 16, 2022. It was curated by Deputy Director, Lena Stringari, and Chief Conservator, Andrew W. Mellon, with the collaboration of Director, Richard Armstrong, and Objects Conservator, Esther Chao. I use the term self-expanding constellations, as I read their self-expanding sculptural entanglements as alternative practices of meaning-making that represent the forming of a new diasporic community.

References

Ahmed, S. 1999. Home and away: Narratives of migration and estrangement. International Journal of Cultural Studies 2(3):329-347. [ Links ]

Ahmed, S & Stacey, J (eds). 2001. Thinking through the skin. London and New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ahmed, S, Castañeda, C, Fortier, AM & Sheller, M (eds.) 2013. Introduction, in Uprootings/ Regroundings: Questions of home and migration. London: Bloomsbury Academic:1-20. [ Links ]

Arendt, H. 1974. Rahel Varnhagen: The life of a Jewish woman, translated by R. and C. Winston. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. [ Links ]

Bachelard, G. 1994 [1958]. The poetics of space, translated by M. Jolas. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. [ Links ]

Barak, AN. 2020. The national, the diasporic, and the canonical: The place of diasporic imagery in the canon of Israeli national art. Arts 9(2):1-17. [ Links ]

Baskind, S. 2007. Encyclopedia of Jewish American artists, artists of the American mosaic. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. [ Links ]

Bhabha, B. 1992. The world and the home. Social Text 31(32):141-53. https://doi.org/10.2307/466222. [ Links ]

Bilski, ED. & Braun, E. 2005. Jewish women and their salons: The power of conversation. New York, NY: Jewish Museum under the auspices of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. [ Links ]

Botto, L. 1972. Work in progress/Louise Nevelson. Interview with Louis Botto. Intellectual Digest 2:6-10. [ Links ]

Bryan-Wilson, J. 2017. Keeping house with Louise Nevelson. Oxford Art Journal 40(1):109-31. [ Links ]

Bryan-Wilson, J. 2023. Louise Nevelson's sculpture. Drag, color, join, face. New Haven,CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Carville, J & Lien, S (eds). 2021. Contact Zones. Leuven: Leuven University Press. [ Links ]

Clifford, J. 1994. Diasporas. Cultural Anthropology 9(3):302-338. [ Links ]

Cohen, R. 2008. Global Diasporas: An Introduction. London: UCL Press. [ Links ]

Corby, V. 2010. Eva Hesse: Longing, belonging and displacement. London: Bloomsbury Collections. [ Links ]

Csikszentmihalyi, MC. & Halton, E. 1981. The meaning of things: Domestic symbols and the self. London: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Dogromaci, B (ed). 2013. Migration und künstlerische produktion: aktuelle perspektiven. Bielefeld: Transkript Verlag. [ Links ]

Eckmann, S. 2013. Exil und modernismus: Theoretische und methodische überlegungen zum künstlerischen exil der 1930er- und 1940er-jahre, in Migration und künstlerische produktion: aktuelle perspektiven, edited by B Dogramaci. Bielefeld: Transkript Verlag:23-42. [ Links ]

Fer, B. 1994. Bordering on blank: Eva Hesse and minimalism. Art History 17(3):424-449. [ Links ]

Flusser, V. 1984-1985. Exil und kreativität in spuren. Zeitschrift für Kunst und Gesellschaft 7(9):5-6. [ Links ]

Gitelman, Z. 2003. The Emergence of Modern Jewish Politics: Bundism and Zionism in Eastern Europe. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [ Links ]

Glimcher, AB (ed). 1972. Louise Nevelson. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers. [ Links ]

hooks, b (ed). 1990. Homeplace. A site of resistance, in Yearning: Race, gender, and cultural politics. Boston, MA: South End Press:41-51. [ Links ]

Kaplan, C. 2006. Deterritorializations: The rewriting of home and exile. Western Feminist Discourse. Cultural Critique 6:187-98. https://doi.org/10.2307/1354261. [ Links ]

Heidegger. M. 1971 [1951]. Building, dwelling, thinking, in Poetry, language, thought, translated by Albert Hofstadter. New York, NY: Harper and Row:143-159. [ Links ]

Kantorovitz Carter Southard, E. 2007. Book review of Lisa E. Bloom, "Jewish Identities in American Feminist Art: Ghosts of Ethnicity". Women in Judaism: A Multidisciplinary e-Journal 5(1). [ Links ]

Larsen, SC. 1975. The American Abstract artists group: A history and evaluation of its impact upon American art. Doctoral Dissertation, Northwestern University. [ Links ]

Levin, G. 2005. Beyond the pale: Jewish identity, radical politics and feminist art in the United States. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 4(2):205-232. [ Links ]

Levin, G. 2010. Jewish American artists: Whom does that include? Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 9(3):421-30. [ Links ]

Lippard, L. 1976. Eva Hesse. New York, NY: Da Capo Press. [ Links ]

Lonzi. C. 1962. Sculture di Nevelson, dipinti di Twombly. Torino: Notizie. [ Links ]

Lovatt, A. 2010. On Ruth Vollmer and minimalism's ,arginalia. Art History 33(1):150-169. [ Links ]

Lovatt. A. 2020. An underground economy: The collection of Ruth Vollmer (1903-1982). Journal of the History of Collections 32(3):573-583. [ Links ]

Marion Young, I (ed). 2005 [1997]. House and home: Feminist variations on a theme, in On female body experience. "Throwing like a girl" and other essays. New York, NY: Oxford University Press: 123-154. [ Links ]

Meskimmon, M. 2003. Women making art. History, subjectivity, aesthetics. Abington & New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Meskimmon, M. 2011. Contemporary art and the cosmopolitan imagination. Abington & New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Naficy, H (ed). 1999. Home, exile, homeland: Film, media and the politics of place. London & New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Nemser, C. 1970. An interview with Eva Hesse. Artforum May:59-63. [ Links ]

Nevelson, L. 1972. Prologue: A total life, in Louise Nevelson, edited by AB Glimcher. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers:19-24. [ Links ]

Ofrat, G. 1998. One hundred years of art in Israel. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. [ Links ]

Piepzna-Samarasinha, LL. 2018. Care work. Dreaming disability justice. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press. [ Links ]

Pratt, MP. 1991. Arts of the contact zone. Profession: Journal of the Modern Language Association 91:33-40. [ Links ]

Puar, JK. 2009. Prognosis time: Towards a geopolitics of affect, debility and capacity. Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 19(2):161-172. [ Links ]

Rapaport, BK (ed). 2007. The sculpture of Louise Nevelson: Constructing a legend. London: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Roth, H. 2021. "First pictures": New York through the lens of emigrated European photographers in the 1930s and 1940s, in Contact Zones, edited by J. Carville and S. Lien. Leuven: Leuven University Press:111-132. [ Links ]

Safran, W. 1991. Diasporas in modern societies: Myths of homeland and return. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 1(1):83-99. [ Links ]

Shain, Y. 2005. The Frontier of Loyalty: Political Exiles in the Age of the Nation-State. New Heaven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Sobchack, V. 1999. 'Is any body home?' Embodied imagination and visible evictions, in Home, exile, homeland: Film, media and the politics of place, edited by H. Naficy. London & New York, NY: Routledge:123-154. [ Links ]

Stanislawski, M. 2007. Louise Nevelson's self-fashioning: The author of her own life, in The sculpture of Louise Nevelson: Constructing a legend, edited by BK Rapaport. London: Yale University Press: 27-38. [ Links ]

Sussman, E. 2002. Eva Hesse. Exhibition catalogue. San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Tagore, T. 2005 [1916]. The home and the world. New Delhi: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Wagner, AM. 1994. Another Hesse. October 69:48-84. [ Links ]

Weir, A. 2008. Home and identity: In memory of Iris Marion Young. Hypathia 23(3):4-21. [ Links ]

The Whole Pop Catalog. 1992. Published by The Berkeley Pop Culture Project. London: Plexus Publishing. [ Links ]