Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Image & Text

versión On-line ISSN 2617-3255

versión impresa ISSN 1021-1497

IT no.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a13

ARTICLES

Home is where the art is? Reflections on changing notions of home and contemporary art practices in the wake of the pandemic

Jacqueline Millner

La Trobe University, Melbourne and Bendigo, Australia. j.millner@latrobe.edu.au (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3052-2312)

ABSTRACT

How has the pandemic changed ideas of home, and how have artists responded to these changes? This article considers the implications of Covid-19's impact on notions of home for contemporary art practices, with a focus on the experience of woman-identifying artists, given the gendered politics of home. Many artists have been forced to rethink how they work in response to the pandemic's effects on freedom of movement, financial security, and exhibition opportunities. In the broader community, 'working from home' has resurged with added legitimacy. To the more optimistic social analysts, Covid-19 has offered an opportunity for a major reset of work practices, but evidence suggests that the pandemic has doubled down on the unpaid care burden of women. For some woman-identifying artists, such developments have become the tipping point for exiting the industry; others have rendered their work almost entirely digital; for yet others it has provided the official imprimatur for long-developed sustaining strategies. I analyse how notions of home have been explored in contemporary art, reflect on how Covid-19 has challenged conventional experiences of home, and discuss examples of artistic practice that have adapted to these changes to examine what 'working from home' might entail in the wake of Covid-19.

Keywords: Feminist art; contemporary art; notions of home; Covid-19 and art; domestic labour; art and social change.

Introduction

One of the conventional markers of being a professional artist is having a dedicated studio - a place that declares the clear delineation between work and home life. For many women practitioners, this public declaration of professionalism has been all the more important - and at the same time all the more difficult - given the gendered assumptions and lived realities around domestic labour. Mierle Laderman Ukeles' 1969 Maintenance Manifesto still rings so discomfortingly true.

Over the last three years, many artists have been forced to rethink their practices in response to the effects of Covid-19 on freedom of movement, financial security, and exhibition opportunities. This had led to the resurgence, and legitimation, of 'working from home'. In this article, I consider the implications of this for the working conditions and creative processes of contemporary artists, with a focus on Australian woman-identifying artists. For some, it appears to have become the tipping point for exiting the industry, for others, it has rendered their work almost entirely digital, and for others it has provided the official imprimatur for long-developed sustaining strategies. I also analyse the impact of the official legitimation of 'working from home' on ideas of home, with the experience of artists as a case study. To the more optimistic social analysts, Covid-19 has offered an opportunity for a major reset of work practices, but evidence suggests that the pandemic has doubled down on the unpaid care burden of women (UN Women 2020). How has the pandemic changed ideas of home, and how have artists represented these changes?

I begin by considering how notions of home have been explored in contemporary art, before reflecting on how Covid-19 has challenged conventional experiences of home, and how some of these challenges coincide with earlier artistic explorations. I then discuss some examples of artistic practice that have adapted to these changes to examine different modes of 'working from home' in the current moment.

Notions of home and contemporary art

'Home starts by bringing some space under control', proposed eminent anthropologist Mary Douglas (1991:287). Home - whether we think of it as a dwelling, a homeland, or a network of relationships - is a fundamental human need that is constitutive of us as subjects. To feel 'at home' in the world means to sense that what we do has some effect and what we say carries some weight (Jackson, 1995), that is, to have some form of agency. By contrast, to be suspended in the agonising limbo of not knowing if or when we will ever have a home is to be rendered largely powerless.

No matter how close or far in time, our childhood overdetermines notions of home (Huston 1999). For philosopher Gaston Bachelard (1969, cited by Jackson 1995:86), our childhood home is our 'first universe'. Whether or not in reality a place of refuge, it 'shelters our daydreaming, cradles our thoughts and memories' (Bachelard 1969, cited by Jackson 1995:86). Bachelard also suggests that that childhood home 'provides us with a sense of stability', although we know that this is not always the case. More convincing is his proposition that those early experiences are 'physically inscribed in us' (Bachelard 1969, cited by Jackson 1995:86) and persist throughout our lives, creating both felt memories and ideals of what home is and should be.

In certain postcolonial writing, home is conceived as a clearly defined space where the subject feels secure and free of desire, while migration is represented as exceptional encounters with strange people and places associated with perpetual feelings of homelessness and loss of identity (Ahmed 1999, cited by Mallett 2004:78). Yet, home is defined by the very movement away from it: when one ventures into the world, the movement itself occurs in relation to home. Movement and dislocation are intrinsic to home; home always involves encounters between those who stay, those who arrive and those who leave (Ahmed 1999:340). Our capacity to make ourselves at home, however, depends in large part on whether we control the circumstances of our passage.

Home has profound political, economic, and psychological dimensions, bringing together 'memory and longing, the affective and the physical, the spatial and the temporal, the local and the global' (Rapport & Dawson 1998:8). It is central to the concerns of a globalised world marked by massive displacements of people, structural inequality, and ever-escalating consumption despite shrinking resources and ecological crisis. Home also remains integral to notions of self and personal agency. Little wonder that contemporary artists have been drawn to home as a theme, one through which the relationships between the private and the public, the individual and the collective, and artmaking and social change can be reimagined.

While the assumption that home is a stable site of belonging is easily challenged, in the feminist imaginary, 'home' is also a rich seam of alternative political visions where new social practices can be trialled and embodied. As theorist and activist bell hooks puts it, motivated in part by the desire to affirm the political agency of those who may feel marginalised in public spaces, '[H]ome is no longer just one place. It is locations. Home is that place which enables and promotes varied and ever-changing perspectives, a place where one discovers new ways of seeing reality, frontiers of difference' (hooks 1991, cited in Massey 1994:171). Home foregrounds that political action does not stop once we exit the streets, take down the barricades and recycle the protest signs, but continues in our daily routines, as German artist and theorist Hito Steyerl observed in respect of 2011's Occupy Movement:

At the end of the day, people might have to leave the site of occupation in order to go home to do the thing formerly called labor: wipe off the tear gas, go pick up their kids from childcare, and otherwise get on with their lives. Because these lives happen in the vast and unpredictable territory of occupation, and this is also where lives are being occupied.! am suggesting that we occupy this space (Steyerl 2011).

Such a perspective necessarily troubles any easy distinction between artmaking, activism, and home.

In The Unmaking of Home in Contemporary Art, Canadian art theorist Claudette Lauzon argues that contemporary art is a vital source of ideas and practices about home and belonging in an increasingly unwelcoming world (Lauzon 2017). Drawing on the theories of Judith Butler (amongst others) and the work of artists such as Doris Salcedo and Gordon Matta-Clark, Lauzon considers the continuing paradox of home: both a tenacious 'site of belonging and a locus of memory' and a 'fragile space whose anticipated capacity to shelter its human inhabitants is radically compromised' (Lauzon 2017:7). Lauzon suggests that the paradox is resolving in favour of the latter, as the myth of home as a safe haven, able to screen out 'more brutal realities both within the home and just beyond its borders', is 'simply no longer sustainable' (Lauzon 2017:9). Nonetheless, the dissolution of the myth allows for the emergence of those artistic gestures that 'reveal the universality of human vulnerability and the limits of empathy', where home is more than an archive for memories of belonging and attachment, and not only 'a reenactment of the instability of structures for habitation' (Lauzon 2017:7), but a metaphor for the fragility of human bodies in relation, and a 'site' to consolidate the power of recognising our shared need of nurturing.

At the same time, Lauzon is careful to make the distinction between vulnerability-in-common as a transformative phenomenon and what she casts as the idealisation of precariousness as an aesthetic category of contingency and risk, which privilege the cosmopolitan, globetrotting artist who is 'at home anywhere' (Lauzon 2017:10). Lauzon cites American sociologist Doreen Massey who reminds us that mobility is allocated and enforced according to complex vectors of power relations:

different social groups have distinct relationships to this anyway differentiated mobility: some people are more in charge of it than others; some initiate flows and movement, others don't; some are more on the receiving end than others; some are effectively imprisoned by it (Massey 1994:149).

As Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman (cited by Beilharz 2001:307) observed many decades earlier of differential mobility, '[S]ome inhabit the globe, others are chained to place'. It is potentially generative to reconsider this differential in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and the distinctive power dynamics that emanated from being 'chained to place' under stay-at-home orders. Amidst Covid-19, enforced mobility carried with it substantial risk - one example might be essential workers who could literally not afford to stay at home - while being 'chained to place' was available more readily to the professional classes, already buffered by wealth and privilege. For a time, being confined to home indeed became a marker of what society values, nurtures and protects.

How Covid-19 changed ideas of home

Since stay-at-home orders were the first line of the defense against the virus used by officials worldwide, how has Covid-19 affected ideas and experiences of home? In much of the literature - primarily from a sociological perspective as well as journalistic thought pieces - the emphasis, at least in the first phase of the pandemic, was on home as shelter, as a space of care, nurturing and family, a place of 'snugness'1 and comfort to which we retreated to ride out the cataclysm.2With a little hindsight, Australian anthropologist Genevieve Bell observes that stay-at-home orders profoundly impacted key modes of perception and experience, namely senses of temporality, embodiment, intermediation, mobility, relationships, and identity, changing thereby understandings of 'home' which is implicated in each of these. To begin with, the distinction between what is real and what is virtual became less clear. Then, the transitions between different daily phenomena to which most are generally oblivious, and the power relations inherent to them, became visible, 'including the functioning of the service economies, models of ownership versus the sharing or gig economy, and myriad supply chains' (Bell 2021:82). As Jenkins and Smith (2021:22) posit, '[R]unning through many aspects of response to the pandemic is a profound tension between increased visibility of the essential contribution made by care work and its ongoing invisibility - continuing to 'count for nothing' - in political and economic common sense'. At the same time, socio-political boundaries - such as those between and within nations, between metropoles and regional areas, and between domestic and public spheres - became far less mutable. Trust, connection, engagement, and care all manifested themselves in unexpected ways, as did their absence. Bell (2021:82) concludes that 'who we are, and how we make sense of ourselves for ourselves and for others, and how we are, in turn, made sense of, were transformed during the COVID-19 stay-at-home period'. As home played host to the panoply of life for months at a stretch for much of the world's population, it became a place that has 'seen everything' (Shukla & Nath 2021:sp) - experiences, expectations and significations of home became more fluid and unanchored.

Extended confinement demands the subject negotiate new socio-spatial relations, with themselves, any co-inhabitants, and the space itself. Undertaking these negotiations in the domestic sphere - that space many associate with letting down their guard - entails a particularly intimate remapping of the body and the emotions. Mexican architecture theorist Carlos Cobreros and his co-authors (2021:sp) posit that, during Covid-19 lockdowns, this process allowed for a transition from initial feelings of bewilderment and anxiety to positive affect emanating from the 'creativity that allows the space to be adapted to new demands, to reappropriate it, and to regain security and serenity'. This (previously unapparent) power to transform what appears fixed, can work to counter the negative affect of fear, as can an enhanced concern for 'the other', with both resulting in 'a more socially conscious approach with attention to common spaces' (Cobreros et al 2021:sp).

This power to creatively reshape domestic spaces resonates strongly with the burst of homespun creativity recorded by many sources around the world, in particular in the first lockdowns. Social media witnessed an exponential increase in the posting of craft and baking projects, for example, as confined populations improvised purposeful adaptation, while spontaneous music-making across domestic bubbles and in tribute to essential workers demonstrated the connective capacity of aesthetics.3 Early in lockdown, artists in various fields too began experimenting with virtual means to maintain their practice. One widespread example was the coordination of audiovisual collaborations through individual contributions made at home then brought together on editing suites and disseminated online in lieu of a performance. This approach was taken up by professional performers of various kinds, including those artists working with communities such as choirs and orchestras, to maintain connection, purpose, and continuing skills development. The virtual studio and exhibition were another manifestation, developed by some visual artists to continue to share their work with peers, the broader arts community, and even prospective markets (Eastwood 2020-21).

However, such examples of constructive reorientations of home to enhance community, 'resilience' and maintain professional activities, are effectively counterbalanced by arguments that propose that Covid-19 foregrounded the limits of public spaces and poor domestic design instead. As South and North American architecture scholars Marco Aresta and Nikos Salingaros argue, Covid-19 demonstrated how domestic architecture had over decades increasingly failed to serve the essential needs of embodied, affective human habitation:

Domestic architecture ceased to take into account important concerns such as the intimacy of each family member; it stopped feeling that space nurtures moments of encounter and leisurely activities, but also of work; it stopped thinking of the need for a space of bereavement and death; it stopped considering space for religious and/or spiritual rites; it stopped thinking of space as a place for healing (Aresta & Salingaros 2021:2).

They conclude that 'for most people at this time of Covid-19, housing is not an expansive space of individual and family comfort, but rather of imprisonment and an agent for obstructing our emotions and thoughts' (Aresta & Salingaros 2021:6). This sense of home as riven with negative affect, as a container for 'unfulfilled desire and broken promises' is poignantly echoed by Indian philosophers Richa Shukla and Dalorina Nath as they 'wonder if home could still be just a place where our heart is, now that our hearts are wounded and bloodied, tired and exhausted, lost and broken', now that 'the promises that the deceased made of coming back' could not be kept. In the wake of Covid-19, they propose that the idea of home has become 'strange' (Shukla & Nath 2021 :sp).

Beyond foregrounding the home as a (generally ill-equipped) site of loss and mourning, Covid-19 also heightened how 'home activates the binary of in and exclusion' (Fellner 2020:92). In a catalogue essay for the exhibition Unhomed that opened in Sweden in 2020 just before the pandemic struck,4 Swedish scholar Shahram Khosravi (2020:21) reminds us that 'From oikos in the ancient Greece to the current idea of homeland (nation-state), homes have primarily been sites of exclusion, not inclusion'. He continues, '[T]he home has been a space for domestic violence and subjugation of women, adolescents, and workers. The notion of the home nourishes sexism and racism' (Khosravi 2020:21). The pandemic created new borders between home and outside, but also deepened the divide between those with resources - health, wealth, digital access - and those without. As Austrian cultural theorist Astrid Fellner argues, citing sociologists Rebecca Marangoly George and Ewa Macura-Nnamdi, home operates as 'a way of establishing difference' between those who live within its boundaries and those who dwell outside. Sharing a space of dwelling produces likeness, and likeness in turn generates and depends on 'inclusion, belonging, membership and acceptance' (Macura-Nnamdi 2014:287). Fellner continues:

And this is why the current homing tendencies reinforce social divides and contribute to a rise in tensions between those who are economically and racially privileged and those groups of people, the disenfranchised and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color), who are excluded. And it is the latter group which have been affected disproportionately hard by the deadly virus (Fellner 2020:92).

It is now well-established that Covid-19 led to a surge in domestic violence across the world (UN Women 2021). Early in the pandemic, US writer Sophie Lewis (2020:sp) had already acutely asked of 'home': 'how can a zone defined by the power asymmetries of housework (reproductive labor being so gendered), of renting and mortgage debt, land and deed ownership, of patriarchal parenting and (often) the institution of marriage, benefit health?'. As Fellner (2020:92) asserts, for many people, 'going home means going back to the prison of heteronormative patriarchy'. Lewis (2020:sp) calls quarantine 'an abuser's dream - a situation that hands near-infinite power to those with the upper hand over a home', where isolation and widespread health and economic stresses combine to devastating effect. While stay-at-home orders were officially deployed to keep people safe, Lewis (2020:sp) argues they have only made more apparent the problems of the privileged position of the heteronormative nuclear family in the nation-state: 'the mystification of the couple-form, the romanticisation of kindship, and the sanitization of the fundamentally unsafe space that is private property'. This 'common sense', 'facilitates ongoing structural gender inequality and strain on individual women' and 'undermines capacities for social resilience, the importance of which this emergency reveals' (Jenkins & Smith 2021:24).

Unsurprisingly, for many feminist critics, Covid-19's exacerbation of these underlying gendered inequities renders this 'an acutely important time to provision, evacuate and generally empower survivors of - and refugees from - the nuclear household', and no time to 'forget about family abolition' (Lewis 2020:sp). Such perspectives might resonate with earlier and longstanding suspicions about the exclusionary and exploitative dynamics at play in notions of home, especially their affiliation with ideas of roots, territory, and national identity, and the attendant (and often less convincing) romancing of 'homelessness' as a countermove. Writing in the context of Sweden's ever-narrowing refugee intake, Khosravi sums up this position:

Homelessness means not recognizing anywhere as home. Only in that condition is humanity not territorialized and can the plagues inherent in the nation-state system vanish and the 'botanical' way of thinking about human beings, in terms or roots and belonging, and the uncritical link between individuals and territory, fade away. Homelessness designates de-territoriality, discontinuity, inconsistency, and interruption, all in contrast to the botanical image of national identity, and thereby can offer unconditional hospitality (Khosravi 2020:21).

Khosravi (2020) concludes by paraphrasing socialist giant Rosa Luxemburg: we should move, or risk not noticing our chains. This brings us back to how Covid-19 flipped the script on Bauman's proposition about differential mobility in certain ways.

Artists' responses

In light of these complex notions of home - both those addressed over years by contemporary artists and those unsettled or revealed by the pandemic and shelter-in-place orders - how did certain artists forced to work from home respond? This last section considers three examples of Australian woman-identifying artists - Rebecca Mayo, Zsuzsi Soboslay, and the artist collective Artist Parents (Nina Ross, Lizzy Sampson and Jessie Scott) - in part as their practices have already engaged deeply with the gendered nature of the still mostly unacknowledged and unremunerated affective labour essential to the functioning of the arts (Sholette 2010). In addition, these artists have also all recognised and/or experienced the contradictions of 'home' under Covid-19, where what appeared at first to be a welcome affirmation of the home as sanctuary from harm (with an expected recognition of care labour) soon became far more fraught, as the delineation of professional activity, productivity, and value undermined their sense of artistic identity, let alone their mental health. However, they all developed adaptations that re-valued the creative possibilities of home.5

Like many artists working as educators and researchers within tertiary institutions while also parenting school-aged children, with Covid-19's onslaught Canberra-based printmaker and academic Rebecca Mayo had to negotiate the sudden merging of all modes of her life in the one site of 'home' with all its problematic assumptions in play. Her professional context was riven with uncertainty and brutal job cuts, which militated against easy collegial solidarity to help face the shared adversity of the pandemic. Such conditions tested Mayo's long commitment to practising according to care ethics: not only a key focus of her artistic work, but a personal code to honour and nurture interconnectedness and relationality. Mayo has reflected on her experience (Mayo 2022) using the framework proposed (using deliberately provocative language) by Australian social scientists Fiona Jenkins and Julie Smith:

we suggest that the abrupt change in the setting for economic production brought by the mandatory move to working from home can be theorised in an illuminating way by analogy with the requisitioning of assets permitted to the state in times of emergency (Jenkins & Smith 2021:24-25).

To requisition is to demand something by official order: it is an extreme measure that overrides ordinary rules and expectations. Under Covid-19 stay-at-home orders, Jenkins and Smith argue, 'dwelling infrastructure could be requisitioned as the essential economic infrastructure for ongoing functioning of the "hibernating" Covid-19 economy' (Jenkins & Smith 202: 25). However, whereas operators of the means of production outside the home were compensated for their forced adaptations, employers and officials for the most part neither compensated for the imposition nor acknowledged the unpaid care work that rendered the home capable of absorbing (if unevenly and with difficulty) such expectations. In her reflections on maintaining her creative practice while she and her collaborating colleagues were confined to home, Mayo focuses on a curatorial project planned before the pandemic designed to explore 'Care in Action' through the site-responsive, textile-based practices of several artists scattered in regional and metropolitan areas brought together at her institutional gallery. When Covid-19 rendered the original project impossible, rather than cancel or attempt to recreate former conditions - and hence necessarily be within a model of 'lack' - Mayo attempted, through the insights of the 'requisition' analogy, to 'enact a resistance to the assumption of individual responsibility and agency' (Mayo 2022).

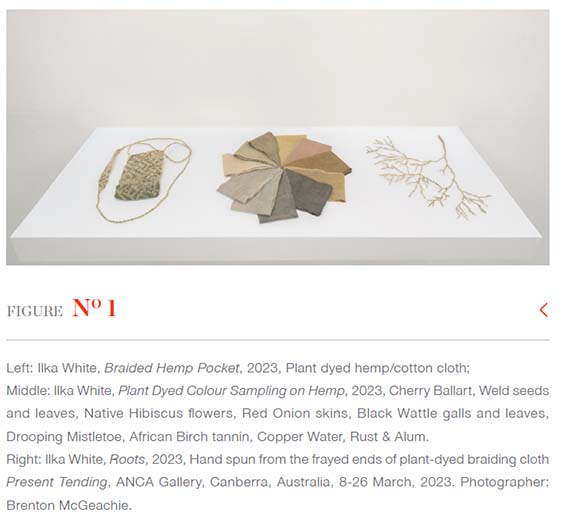

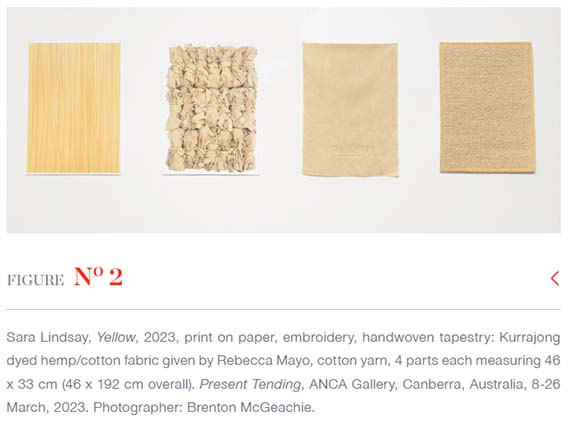

The artists in what became Present Tending6 (Figs 1-3) were not asked to simply replicate at home what they would have done in the (supported) gallery environment, but to 'find ways of using...within existing work plans or commitments' a swatch of cloth that Mayo had dyed and mailed to them. As such, the project became something quite distinct from its initial conception as an exploration of shared materiality and space: now, it sought to 'trace and record connections and tensions between paid and unpaid labour and contribute to the recognition of unaccounted for care-work as labour' (Mayo 2022). The specific material Mayo provided, natural fibres dyed with locally sourced plant colour, helped connect the artists, and their subsequent audiences, to place, labour and care. Sara Lindsay, for example, over-dyed the cloth with pigments derived from her own garden, an extension of her daily gardening rituals that helped sustain her. Ema Shin shared part of the cloth with her children to create a 'playmat for peace of mind', integrating activities of family care, while another part was used to finesse Shin's mending technique, Sashiko embroidery, a traditional Japanese craft used for repairing worn garments. For each artist, interacting with the cloth and the curatorial premise offered opportunities to creatively enmesh their artwork into their everyday. As Mayo summarised,

By focussing on the home, and how working from home complicated our relations to work and care-work, I developed an alternative approach to the exhibition in which the artists may participate without making 'more' work. In doing so I hope to shed light on the complexities of working from home (Mayo 2022:173).

When Covid-19 hit, Canberra-based educator, therapist, and social practice and performance artist Zsuzsi Soboslay had already for many years been researching how current outcomes-based arts ecologies fail to recognise and support the essential behind-the-scenes labour needed to sustain an artistic practice. Like Mayo, Soboslay framed her analysis of such structural inequalities through care ethics: what she observed was a lack of care and non-valuing of this essential work emanating from a narrow neoliberal emphasis on 'measurable' 'value-adding'. Soboslay advocated for a values revolution informed by care ethics that would expand the focus beyond the public-facing 'end product' of artmaking. While the pandemic and lockdowns brought familiar stresses to Soboslay, it also led to a commission that allowed her to test and enact some of her longstanding insights: as the art world's modus operandi was completely upturned, it suddenly became impossible to publicly exhibit or perform those 'end products' in the usual way. From 2020 to 2021, Soboslay developed workshops for artists in all fields whose practice had been disrupted by COVID, adapting an ongoing project, ReStorying, to explore how we might effectively support and sustain the thousand steps, minor gestures and hours of practice that Karen Barad insists are the 'very buildingblocks of mattering'. ReStorying is,

an open-ended exploration of alternative rhythms, subliminal awarenesses, and speculative processes, to reconfigure where we have been, where we are, and where we are going...It sets out to enhance reciprocal relations that support and engender creativity. There is no intention to provide solutions; rather, the invitation is to sit in an in-between space and encourage a letting-go and reordering. It offers a chance to reconfigure habits, by working with the non-dominant hand (figuratively and metaphorically).. .and giving us a break from outcomes (Soboslay 2023:205).

The workshop modules in ReStorying are all online which participants join from their own homes, although Soboslay was careful to create a very different experience to the now notorious Zoom tutorials that locked-down educational institutions offered as substitutes for face-to-face learning. Putting into place long-held principles, she set out to explore 'how else can we gesture, sketch, paint, make sound, or move', sidestepping 'the punishing expectations of "advancement" especially at the expense of one's own resources and stamina' by designing and coordinating modules that 'sustain a playful, cross-disciplinary disruptiveness' (Soboslay 2023:205). Many participants reconfigured their own professional prisms: 'dramaturgs start painting murals; playwrights turn to writing songs; painters revision their life narratives', demonstrating that vital to nurturing creativity is support for open-ended artistic processes. As Soboslay reflects,

[T]he project offered an alternative space to what have become "normal" operations across arts industries that usually validate by outcomes and value the "grand gesture" above the many thousand, unremunerated, steps that comprise our artmaking 'along the way' (Soboslay 2023:198).

In so doing, ReStorying re-values home as a creative space in an analogous manner to Mayo's Care in Action adaptation. In these examples, at home, those nurturing activities deemed incidental to artistic practice are acknowledged, affirmed and facilitated, offering a very different mode of practice to the conventionally understood 'home studio'.

Melbourne-based artists Nina Ross, Lizzy Sampson and Jessie Scott came together some years ago as the loose collective Artist Parents to support each other in the face of the hostility they encountered in the Australian art world upon becoming mothers. It was a hostility manifest in many ways, not just in the lack of proper amenity but also in the negative discourse from colleagues as well as gatekeepers and powerbrokers such as curators and gallerists. This included assumptions that having a child was a signal that one was no longer serious about pursuing a career as an artist, and the accompanying disdain for the proposition that one is able to be artistically productive and innovative 'working from home'. The collective gathered evidence of this discrimination not just from personal experience, but also from surveys and interviews conducted in the Melbourne art world (Ross, Sampson & Scott 2022). Having spent several years both cleaving open the sites of essential affective labour and rebutting damaging stereotypes by producing artwork in and through the solidarity of parenthood, the artists discovered the pandemic took them back to square one. Forced from art practice to full time carer roles, bearing the brunt of 'the requisition' of the home, Artist Parents found 'the drive, ambition and determination to make an arts practice work disappeared into thin air due to practical constraints, pandemic fatigue, stress and anxiety' (Ross, Sampson & Scott 2022:75).7 However, they gradually improvised a means of nurturing home-bound creativity which, like Mayo's and Soboslay's approaches, sought to affirm in-between moments and incidental spaces as essential creative work, rather than essential to creative work. With Artist Parents, this took the form of relayed voice messages on a group thread to maintain their sharing of experiences of art, parenting, and the effect of the pandemic on both, and to cultivate 'acceptance about not producing art for anyone but ourselves'. Inherent in this mode of 'light-touch' contact is the profound mutual respect of each member of the collective that serves to not hierarchise one's temporality over another's, and whose emphasis is on open and extended 'listening'. As they elaborate,

This time delayed conversation allowed us to connect across individual, differentiating schedules, which encompassed: parenting a newborn and a toddler; home-schooling new preps; working an arts admin job from home; studying a PhD; grieving for a dead partner; remotely supporting a frail grandparent; and a general increase in cooking, cleaning, and other housework duties. So much caring had disproportionately fallen in our laps in 2020, and absent the option of self-care, we instinctively reached out to care for each other (Ross, Sampson & Scott 2022:75).

Conclusion

Covid-19's widespread and sustained confinement orders intensified, rendered 'strange' and transformed experiences of home. The temporary 'requisition' of home by the state as a site for productive activity laid bare the affective labour essential to social and economic functions in such a way that feminist critics might have hoped for a fundamental reset that genuinely acknowledged the contribution of this still highly gendered work. While this has not come to pass, the dramatic effects of Covid-19 on home both demanded and provided opportunities to explore different modes of 'working from home' that challenged existing assumptions, including that it entailed duplicating conventional work practices in another locale. For certain woman-identifying contemporary artists, for example, who had long wrangled with the stigma of 'the home studio' and were all too aware of home as a conflicted site for their feminist practices, the Covid-19 crisis was a catalyst for adaptations that affirmed care-ethics informed ways of working. In particular, these approaches tended to 'in-between' moments and incidental spaces, valorising these as essential creative work rather than essential to creative work. In such practices 'home' becomes an experiment in creativity as care rather than a site of 'productivity', potentially contributing to a longer-term transformation of understandings of home.

Notes

1 . The not quite translatable Danish 'hygge', which evokes feelings of warmth and enjoyment with people and places we feel close to.

2 . For example, Anon (2021a), Anon (2021b), and Durnová and Mohammadi (2021). This, despite longstanding critique in the multidisciplinary literature that suggests 'that the characterization of home as haven is an expression of an idealized, romanticized even nostalgic notion of home at odds with the reality of peoples' lived experience of home' (Mallett 1994:72).

3 . Later psychological studies, for instance, have confirmed this, with participants recording increases in their creativity during lockdown (Alizée Lopez-Persem et al 2022).

4 4.Unhomed (Uppsala Art Museum Uppsala, 01/02/2020 - 10/05/2020) 'showcases artists whose artistic practices are in continuous interchange with the intricate narratives of cultural heritage, history writing and liberty of speech. The exhibition title comes from Shilpa Gupta's work Words come from Ears 2017 - 2018, a subversive work that allows reflection on the processes of arrival and departure' (uppsalasmuseer.se).

5 . With its focus on Australian practice, this article does not consider examples of artwork that specifically addressed the growth in incidence of domestic violence under the pandemic as these were rare at the time of writing and the focus here is on the creative reimaginings of home and art under lockdown. However, a British artist who powerfully engages with this is Anna Dumitriu in her commissioned work Shielding: https://annadumitriu.co.uk/portfolio/art-data-health-commission/.

6 . Present Tending by Rebecca Mayo, Kylie Banyard, Sara Lindsay, Ema Shin, Ilka White and Katie West at ANCA Gallery 8-26 March 2023. The six artists in Present Tending share interests in textiles, plant colour, ethics of care, stories and places. Katie West (Yindjibarndi) is based in Noongar Ballardong country, Ilka White and Kylie Banyard (Anglo-Celtic) live on Dja Dja Wurrung Country, Ema Shin (Korean, raised in Japan) and Sara Lindsay (Anglo-Celtic) live in Naarm (Melbourne), and Rebecca Mayo (Anglo-Celtic) lives in Ngunnawal/Ngambri Country.

7 . Artists around the world found innovative means to support each other during lockdowns and their frequently ravaging consequences. What happened in Johannesburg, in part inspired by the networks of artist-run support that sprung up amid the AIDS pandemic, is a powerful example well-documented in by Auslander, Allara and Berman (2021).

References

Ahmed, S. 1999, Home and away: Narratives of migration and estrangement. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 2(3):329-347. [ Links ]

Anon. 2021a. How has a pandemic year changed your idea of 'home'? The New York Times, 3 March 2021. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/03/travel/how-has-a-pandemic-year-changed-your-idea-of-home.html Accessed 23 November 2022. [ Links ]

Anon. 2021b. They're stuck at home, so they're making home a sanctuary. The New York Times, 17 May 2021. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/04/business/coronavirus-home-upgrades.html Accessed 23 November 2022. [ Links ]

Aresta, M & Salingaros, NA. 2021 .The importance of domestic space in the times of COVID-19. Challenges, 12(27): Available:https://doi.org/10.3390/challe12020027. Accessed NO DATE [ Links ]

Auslander, M, Aliara, P & Berman, K. 2021 "Where shall we place our hope?": Covid-19 and the imperiled national body in South Africa's "Lockdown Collection". African Arts, 54(2):78-89. [ Links ]

Bachelard, G. 1969. The poetics of space. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. [ Links ]

Bell, G. 2021. Pandemic passages: An anthropological account of life and liminality during COVID-9. Anthropology in Action, 28(1):79-84. [ Links ]

Cobreros, C, Maya, M, Bionid, S, Sanchez, X & Ontiveros-Ortiz, E. 2021. Resignify the domestic space in times of confinement from the application of ethnographic tools and personal centred design. International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, 9-10 September, 2021, University College, Herning, Denmark, 2021. [ Links ]

Douglas, M. 1991. The idea of home: A kind of space. Social Research, 58(1):287-307. [ Links ]

Durnová, A & Mohammadi, E. 2021. Intimacy, home, and emotions in the era of the pandemic. Sociology Compass, 4 April. Available: https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/soc4.12852 Accessed NO DATE [ Links ]

Eastwood, D. 2020-21. Art Monthly Australasia, 326:54-59. [ Links ]

Fellner, A. 2020, What's home gotta do with it? Reflections on homing, bordering, and social distancing in COVID-19 times, in Bordering in pandemic times: Insights into the COVID-19 pandemic: borders in perspective, edited by C. Wille and R. Kanesu. UniGR-CBS Thematic Issue 4/2020 [ Links ]

Huston, N. 1999. Nord Perdu. Paris: Lemeac Editeur. [ Links ]

Jackson, M. (ed.). 1995. At home in the world. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Jenkins, F. & Smith, J. 2021. Work-from-home during COVID-19: Accounting for the care economy to build back better. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 32(1):22-38. [ Links ]

Khosravi, S. 2020. Unhomed catalogue essay, Uppsala Konstmuseum, Uppsala. [ Links ]

Lauzon, C. 2017. The unmaking of home in contemporary art. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

Lewis, S. 2020. The virus and the home: What does the pandemic tell us about the nuclear family and the private household? Bullybloggers, March 20. Available: https://bullybloggers.wordpress.com Accessed 10 January 2023. [ Links ]

Lopez-Persem, A, Bieth, T, Guiet, S, Ovando-Tellez, M & Volle, E. 2022. Through thick and thin: changes in creativity during the first lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13:821550. [ Links ]

Mallett, S. 2004. Understanding home: A critical review of the literature. The Sociological Review, 62-89 [ Links ]

Marangoly George, R. 1999. The Politics of home. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Massey, D. 1994. Space, place and gender. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Mayo, R. 2022. Alleviating anxiety: Care in action during the pandemic, in Care ethics and art, edited by J. Millner & G. Coombs. London: Routledge:173-184. [ Links ]

Millner, J & Coombs, G. 2022. Care ethics and art. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Perry, L & Krasny, E. 2023. Curating with care. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Rapport, N & Dawson, A. 1998. Migrants of identity: Perceptions of home in a world of movement. Oxford: Berg. [ Links ]

Richa, S & Nath, D. 2021. Pandemic and the eternal wait: has COVID changed our idea of home?. The Quint. Available: https://www.thequint.com/voices/blogs/home-and-waiting-during-covid-pandemic Accessed NO DATE [ Links ]

Ross, N, Sampson, L. & Scott, J. 2022. Soiling the white cube: artist parent experiences, in Care ethics and art, edited by J. Millner & G. Coombs. Londen: Routledge:67-80. [ Links ]

Sholette, G. 2010. Dark matter: Art and politics in the age of enterprise culture. London: Pluto Press. [ Links ]

Soboslay, Z. 2023. Cultivating care ethics and the minor gesture in curatorial and research practices, in Curating with care, edited by L. Perry & E. Krasny. London: Routledge:197-208 [ Links ]

Steyerl, H. 2011. Art as occupation: claims for an autonomy of life. e-flux, 12(3): n.p. [ Links ]

UN Women. 2020. Whose time to care: unpaid care and domestic work during COVID-19. Available: https://data.unwomen.org/publications/whose-time-care-unpaid-care-and-domestic-work-during-covid-19 Accessed 15 February 2023. [ Links ]

UN Women. 2021. Measuring the shadow pandemic: violence against women during COVID-19. Available: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/feature-story/2021/11/covid-19-and-violence-against-women-what-the-data-tells-us Accessed 15 February 2023. [ Links ]