Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Image & Text

versión On-line ISSN 2617-3255

versión impresa ISSN 1021-1497

IT no.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a12

ARTICLES

Material worlds: Domestic objects and the question of auto/biography in contemporary art

Clara Zarza

School of Architecture and Design, IE University, Madrid, Spain. czarza@faculty.ie.edu (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4905-5067)

ABSTRACT

At the turn of the twenty-first century, due to the expansion of postcolonial consciousness, artists identified as "non-western" gained a new visibility in the Euro-American art world that was far from unproblematic. Installations and multimedia practices revolving around domestic space and daily objects were internationally celebrated as a novel source for reflections on the notion of home. Based on the assumption that artists' lived experiences of migration, separation, or loss made their use of the domestic inherently transgressive, these disparate works were framed as autobiographical or self-representational. With this, the institutional landscape seemed to undergo a total transformation in reevaluating the use of personal materials in art practices. Dismissed as confessional or narcissistic when articulated as a key critical strategy by feminist Euro-American artists just a decade earlier, it was precisely this personal and domestic quality that seemed to be seen as valuable and relevant in the context of an art world with newfound pretensions of inclusion and globalisation. Focusing on Ishiuchi Miyako's work Mother's 2000-2005: Traces of the Future as a case study, I argue that the reasons behind this notable shift were twofold: first, the shift in artistic language, from the political explicitness of earlier feminist artworks to the use of material subtlety and conceptual ambivalence, allowed for these works to travel well from national to international exhibitions; at the same time, the use of personal and domestic objects seemed to justify their framing through biographical narratives that, in turn, served to comfortably categorise them, while also offering grounds for viewer engagement.

Keywords: Home, Feminist Art, Global Art World, Possessions, Autobiography, Ishiuchi Miyako.

Introduction

In Euro-American cultures, the notion of 'home' elicits a variety of material and psychological associations: physical spaces (a house, a city, a country), material worlds (objects of daily use and memorabilia), a body (individual, maternal, romantic), a language, a person, or a group, and even a set of habits and rituals. Often, these associations are grounded in the underlying assumption that 'home' is that which ensures our identity, our understanding of who we are, a sense of self, comfort, and security.1 During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with the economic and industrial development that led to the rise of modern cities in Europe and North America, the factory and the office came to be perceived as dehumanising and oppressive spaces of productivity and normativity. In turn, the notion of home was necessarily reconceptualised. Established in opposition to the workspace, the modern home was articulated as a place for respite, reconstitution, and individualisation - an idyllic, heavenlike space, and a repository of all virtues. The home, along with its décor, furniture, and objects, was designed and chosen to provide rest and health for the body, moral enhancement for the mind, and an opportunity for self-expression. However, while this duality served working- and middle-class men, it in turn entailed immense pressure on other members of the household - middle-class women and servants - who had to sustain the illusion without an alternative space for respite.2 This tension, and the artificiality of this idyllic construction, did not remain unnoticed. Radical artistic practices throughout the twentieth century challenged the home's unequivocal heavenly and maternal connotations. With a precedent in French Surrealism's unsettling objets trouvés, the Women's Art Movements of the 1970s were relentless in undermining domestic idealisations of nourishment, safety, stability, and privacy, recasting the home as a site of oppression, standardisation and invisibility.3 Often using everyday domestic objects (kitchen tools or toiletries), these practices brought in illicit materials that had previously not been seen in the aseptic space of the art gallery. The public space of the museum or gallery was thereby polluted by a conflict that had been swept under the rug of the private.4 However, the way these practices were received and presented by the institutional art world was depoliticising and often dismissive. They were read either as confessional, and thus lacking authorial agency or artistic mediation, or else as self-obsessed and narcissistic, seen through the lens of the pathological and therefore as missing intellectual depth and complexity.

Paradoxically, only a decade later, artists working with notions of home experienced a drastic increase in visibility through the main channels of the Euro-American art world, particularly when identified as "non-western".5 Installations and multimedia practices revolving around domestic space and materiality, and using personal possessions and everyday objects, received a great deal of attention and were celebrated internationally. In their critical and curatorial framings, based on the assumption that such practices reflected the artists' lived experiences of migration, separation, or loss, these works' reliance on the domestic was presented as inherently transgressive and aligned with the art world's search for inclusiveness and internationalisation. Works by disparate artists such as Mona Hatoum, Emily Jacir, Zineb Sedira, Shirin Neshat, Ishiuchi Miyako, and Do Ho Sun, were often exhibited as part of a newfound postcolonial consciousness, while also being framed as having autobiographical or self-representational qualities. With this, the institutional landscape seemed to undergo a total transformation in its revaluation of the use of personal materials in art practices that is worth exploring.

In sum, even though dismissed as confessional or narcissistic when articulated as a key critical strategy by the Woman's Art Movement, it was precisely their apparent connection to the personal that seemed to make these works valuable and relevant to the institutional Euro-American art world. It is this notable shift that I wish to address in the following pages. Why were the very same domestic objects -toiletries, textiles and kitchen utensils - seen to acquire artistic weight and creative complexity at this moment? Why was the reliance on the personal no longer perceived as superficial and self-indulgent, but as bearing conceptual richness instead? In other words, why was the use of everyday objects first seen as lazy or compulsive but later as sophisticated? I would like to argue that the response to these questions is twofold and lies both in the visual and material choices made in the moment of production, as well as in the curatorial and critical frameworks that conditioned their international reception.

Focusing on Ishiuchi Miyako's work Mother's 2000-2005: Traces of the Future as a case study, I will analyse the photographic series' visual language and will expose the shift from the political explicitness of earlier feminist artworks to the use of material subtlety and conceptual ambivalence. I will argue that this shift in artistic language is not uncommon and has allowed works to travel well from national to international contexts. At the same time, I will analyse the content and references of Ishiuchi's work, exposing how the use of personal and domestic objects, while seemingly justifying the use of the biographical, is limiting. I will argue that while identifying Mother's as autobiographical or self-representational allows for a comfortable categorisation that offers grounds for viewer engagement, the biographical method also impedes other complex reflections offered by the work. My analysis will thus link back to exposing the tension between conformist visibility and marginal resistance that was already present in earlier feminist and postcolonial practices. At the same time, it will also explicitly address the issues behind biographical methods in art history and criticism, the internal structures of the art world, and the artist-institution relationship.

The use of everyday objects as artistic material

In the twentieth century the use of new media and formats allowed artists to explore everyday objects in an unprecedented way, and the subject of home and domesticity took on increasing centrality. Surrealism's examination of Sigmund Freud's concept of the uncanny and the unsettling qualities of familiar spaces and objects was recurrent in film, photography, and ready-mades. Everyday domestic objects were rendered strange and menacing through an emphasis on materiality, sensoriality, and what Janine Mileaf has called 'tactile vision' (Mileaf 2010:22).6 Man Ray's Cadeau (1921), Méret Oppenheim's Le Dejeuner en fourrure or Ma gouvernante (1936), and Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid's film Meshes of the afternoon (1943), are but a few iconic examples. These artists looked at mundane materials of everyday life and domesticity in a new light and revealed the underlying tensions that bourgeois societies had worked so hard to mask.

While surrealist practices were transgressive, their reflections were easily seen as dealing with broader social consciousness rather than playing with the personal as such. Instead, feminist artists and theorists, through their interrogation of the boundaries between private and public, reclaimed the 'personal' as an acceptable subject matter for art, and recognised in everyday domestic objects a fertile ground for critical discourses around identity, normativity and agency. Key examples can be found in Jo Spence's The family album (1979), Mary Kelly's Post-partum document (1973-79), and Betye Saar's Record for Hattie (1974), to name just a few. Particularly relevant in its founding use of domestic, trivial, and taboo everyday objects is the group installation Womanhouse (1972), produced during the first year of the Feminist Art Program (FAP) at the California Institute of the Arts (California State University, Fresno). As Miriam Schapiro remembers, in 1972 there were:

...interesting unwritten laws about what is considered appropriate subject matter for art-making. The content of our first class project Womanhouse reversed these laws. What formerly was considered trivial was heightened to the level of serious art-making: dolls, pillows, cosmetics, sanitary napkins, silk stockings, underwear, children's toys, washbasins, toasters, frying pans, refrigerator door handles, shower caps, quilts, and stained bedspreads. (Schapiro 1972:269)

Such explorations of personal materials sought to critique the traditional opposition between public and private, which relegated women to the domestic sphere and precluded their identification as 'public' figures or artists. Nonetheless, unlike surrealist object-based pieces, Womanhouse, like many of the works of the Women's Art Movement, was denied a broader consciousness.

Despite the Women's Art Movement's extensive theorisation on the political and social importance of exposing personal material, their work was regularly disparaged as self-indulgent and narcissistic. As Carol Hanisch explains in her legendary paper 'The personal is political' (1969), consciousness-raising groups across the United States were not intended as therapeutical, but rather as a key site for the critical collectivisation of the private sphere, and art played a significant role in making such matters visible. Important exhibitions such as In her own image (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1974), Self-portrait show (The Woman's Building, 1975), Lives: artists who deal with people's lives (including their own) as the subject and/or the medium of their work (traveling exhibition, 1976), and Feministo: portrait of the artist as a housewife (traveling installation, 1975-1977), showed the works of artists engaging with personal material. However, dominant criticism in magazines such as Artforum or Artnews dismissed these practices as little more than acts of self-obsession and narcissism. An example of such criticism is offered by Tom Wolfe's description of the 1970s as the 'Me decade' (1976) and Peter Frank's parallel Artnews article entitled 'Auto-art: Self-indulgent? And how!' where he dismisses these practices as 'consonant with the self-involved, confessional, even narcissistic - but rarely contented - spirit of the age' (Frank 1976:43). Even authors close to the Woman's Art Movement, like Lucy Lippard, expressed suspicions; in conversation with Suzanne Lacy, Lippard recalled feeling that the idea of the personal as political soon became a hall pass: 'Now everything that I do is political so, all my art will automatically be political, so I never have to do anything politically' (Lacy & Lippard 2010:153).

However, the idea that the personal should be seen as having political importance was not unnuanced; many feminist authors also reflected upon the limits of such practices, both in terms of agency and identity representation. In 1980, during the conference 'Questions on Women's Art' at the ICA in London, Martha Rosler asked, 'Well, is the Personal political?' as a reminder about the importance of bringing 'the consciousness of a larger collective struggle to bear on questions of personal life' (in Robinson 2001:95-96). Similarly, Jo Spence, in her article 'Beyond the family album' (1980) and her book Putting myself in the picture: a political, personal, and photographic autobiography (1986), reflected on her work and its broader implications. The limits of these collective exercises in terms of race and class were also exposed by theorists such as bell hooks, who, in Feminist theory: from margin to center (1984), criticised the narrowness of a white middle-class feminist view and paved the way for postcolonial revisions within the movement. Nevertheless, even as these practices became increasingly visible and nuanced, the criticism was relentless - criticism that ultimately reduced the work to uncontrolled acts of self-exposure.

Counter-criticism of this reductionist reading, and the foregrounding of work by women and non-normative subjects as perpetually linked to the confessional and the testimonial, became a fundamental part of feminist and postcolonial revisionist studies during the last decades of the twentieth century. However, such efforts have not prevented earlier feminist practices from being read as merely autobiographical, regardless of whether the autobiographical is viewed negatively or positively. Such a reading is still at play, for instance, in the celebration of more recent works' supposed ability to offer access to the artist's self, especially in the case of artists regarded as non-normative in terms of identity or lived experience. Literary studies on self-representation, such as Domna Stanton's The female autograph (1984) or Irene Gammel's Confessional politics (1999), have shown how women's autobiographical texts are generally assumed to be incapable of reaching a higher plane, instead seen exclusively in terms of documentation or confession, and 'dismissed as "raw," "narcissistic," and "unformed"' (Gammel 1999:4). Similarly, in relation to artistic practices, Amelia Jones has pointed out how feminism's turn to the personal in the 1960s and 1970s was discredited as trivial, self-absorbed, or even narcissistic, and thus overlooked by mainstream criticism dominated by magazines such as October and Artforum (Jones 1999:29). In their book Interfaces (2002), Julia Watson and Sidonie Smith continue to analyse later practices and reinforce this conclusion: that the understanding of women's work as a transparent reflection of personal experiences has led to the consideration of the work of many women artists as a narcissistic practice devoid of artistic mediation. Although important revisions by Amelia Jones and Jo Anna Isaak have further argued that narcissism was a strategy adopted by feminist artists to transgress not only the dominant models of female subjectivity, but also notions of individuality, the interpretative focus on the personal and the biographical remains unnuanced and unproblematised both in the critical dismissal in the literature of the seventies and eighties, and in the institutional celebration just a decade later.

Visibility and the problematic global art world

In the 1990s, the use of personal material and the exploration of autobiographical modes in visual art became part of a broader phenomenon of cultural interest in self-representation and self-exposure. The sorts of texts defined by historian Jacques Presser as 'ego documents' became an important source for historians and journalists.7In terms of cultural history, The decade came to be known for the 'memoir boom' that saw a surge in commercially successful autobiographical texts by diverse voices.8 This phenomenon was paralleled in entertainment culture, with the rise of tabloid talk shows, for example. At the same time, the rapid economic growth and expansion of the art world in the 1990s was accompanied by an assimilation of postcolonial consciousness, leading to a search for inclusiveness and globalisation. However, as many studies have discussed, this search for new voices proved highly problematic in relation to critical discourses about identity, normativity, and agency. The reality of inclusion is questionable; as Charlotte Bydler points out in her book The Global Art World, Inc., much of the production that reaches international circuits from countries of the former colonies is produced in Paris or London by expatriates (Bydler 2004:31). Even when this is not the case, the pervasive mechanisms of exoticisation, as Graham Huggan reminds us, often turn these works into a 'literalised consumer item' (Huggan 2001:59), despite their best efforts to resist this tendency. The issue is broader, as Angela Dimitrakaki puts it, in the global art world, social- and politically-oriented art is 'inscribed not as a practice conducive to social justice but as a valuable curiosity' (Dimitrakaki 2016:4). The problem of how artworks become embedded in the art world and art history was already addressed by Dimitrakaki in an earlier study, 'Researching culture/s and the omitted footnote' (Dimitrakaki 2004), in which she highlights that it is not only that the critical and curatorial structures that accommodate art beyond the Euro-American framework are inadequate, but, moreover, that their inadequacies and conflicts are intentionally omitted in the pursuit of narrative coherence. Apparently innocuous labels, such as 'contemporary art', are deeply charged with structures and connotations, which produces conflicts and misinterpretations in intercultural research that often go unaddressed. Both the framework through which artworks are viewed and interpreted, and the language used in artistic practice, should be considered a means of visibility and, at the same time, a potential threat to the very concepts that the artist intends to make visible. Misinterpretation and the inevitable depoliticisation that takes place in the process of cultural translation and decontextualisation are also Chin-Tao Wu's primary concern when reflecting on grand international exhibitions, although, in this case, focused on the position of the viewer (Wu 2007). What all of these studies evidence is that, in the 1990s, the opening up of the narrow circle of the art world was far from idyllic.

The impact of the cultural premises imposed by institutional and conceptual frameworks on artworks identified as "non-western" has been widely discussed. Less evident is the artists' role, their awareness of these depoliticising structures, and their willingness to accommodate or even embrace them to gain visibility. In his article, 'For they know what they do know,' Iranian artist Barbad Golshiri criticises high-prized Iranian artists in the international market like Shirin Neshat, Shadi Ghadirian, Ghazel, and Shirin Ali-Abadi, for their willingness to submit to 'the agents of ethnic marketing' and fulfil potential clients' 'desire for predictability' to promote their work (Golshiri 2009:15). From a more nuanced standpoint, María Lumbreras points out the strategies for adaptation and visibility that the political, yet internationally renowned artist Mona Hatoum has had to undertake throughout her career to retain visibility (Lumbreras 2011). Lumbreras borrows Homi Bhabha's concept of 'colonial mimicry' to illustrate Hatoum's adaptation strategy. Lumbreras argues that, although Hatoum's minimalist visual language retains a subtle resistance by challenging expectations and playing with contradiction, the danger of depoliticisation remains.

The risk of depoliticisation in strategies of adaptation or mimicry is further evidenced if we understand a fundamental paradox of the 1990s: while the internationalisation of the Euro-American art world seemed to integrate the feminist and postcolonial critiques of the previous decade, the art world's agenda for inclusiveness coexisted with the celebration of the depoliticisation of artistic practices. As feminist art historians such as Rosemary Betterton and Amelia Jones have argued, even though many of the practices of the 1990s and early 2000s drew strongly on the feminist practices of the 1960s and 1970s for their source material, this is often misrepresented by artists and critics insofar as what was celebrated was precisely a careless or apolitical attitude (Betterton 2000; Jones 2008). Nineties art and artistic attitudes seemed to be marked by a willful detachment - a moderation of, if not total disengagement from, the political agendas of the previous decades. Betterton, as well as Julian Stallabrass (1999), focused on the case of Britain to point out the incongruity of how the so-called Young British Artists were identified as transgressive while at the same time accommodating market imperatives, unproblematically integrating mainstream media strategies, and realigning with the sphere of cultural consumption. This is what Betterton called 'the uneasy marriage between avant-garde shock and commodity consumption' (Betterton 2000:14).

In turn, an assessment of the failures of visibility is addressed in Gender, artwork and the global imperative (2016) in which Angela Dimitrakaki openly examines the internal articulations of the relationship between artist, curator and institution, in order to reveal the servitudes and concessions exacted from artists. The tension between conformist visibility and marginal resistance is not new; indeed, most feminist revisionist historiography has been concerned with this very issue. However, few texts address the internal structures of the art world and the way artists navigate these issues at the conscious level. It is at this intersection between historiography and the explicit formulation of the artist-institution relationship and choices, where I wish to situate my argument.

In 2016, I published a chapter in the book Home/land: women, citizenship, photographies (Zarza 2016), in which I focused on artist Emily Jacir's work and argued that her process-based piece Where we come from/(im)mobility challenged both exoticisation and conventional modes of self-representation by blurring the artist's self and authorial voice in the representation of other peoples' notions of 'home' and 'homeland'. This strategy of displacement, and the documentary techniques chosen by the artist as her visual language, enabled her to play with expectations and reveal the conventions and constructiveness implicit in these concepts. While my emphasis in this article was on Jacir's artistic strategies and the work's capacity to resist exoticisation, here I focus on the changes in visual language and in curatorial and critical narratives that led to the unprecedented new visibility of object-based works produced by artists from diverse nationalities beyond the Euro-American context. In order to do this, I would like to take a moment to look at Ishiuchi Miyako's work Mother's 2000-2005: Traces of the Future, a large-scale photographic and video installation featuring everyday objects, toiletries, clothing, and body fragments, chosen by curator Michiko Kasahara to represent the Japanese Pavilion at the fifty-first Venice Biennale called The Experience of Art (2005). It is a relevant case study in that it departs from the post-colonial migrant subject, more often problematised in recent literature, and looks instead at work by an artist from a country with a robust economy beyond the Euro-American context (Japan), which, moreover, was exhibited at a space that represents the epitome of the great international contemporary art exhibition.

The case of Ishiuchi's Mother's

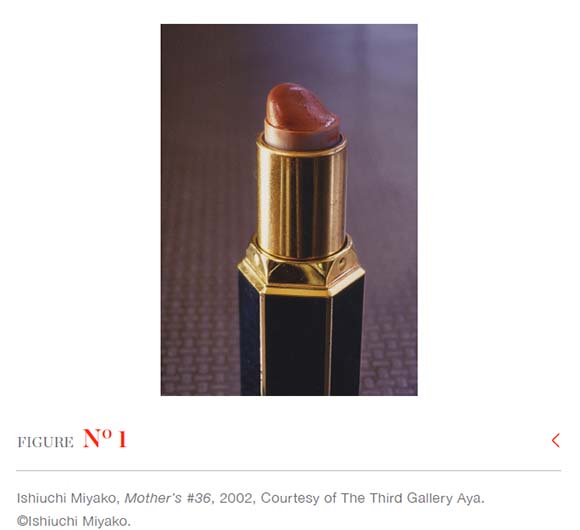

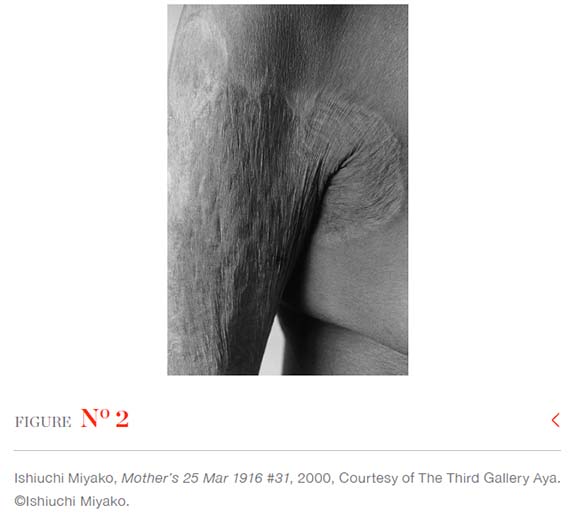

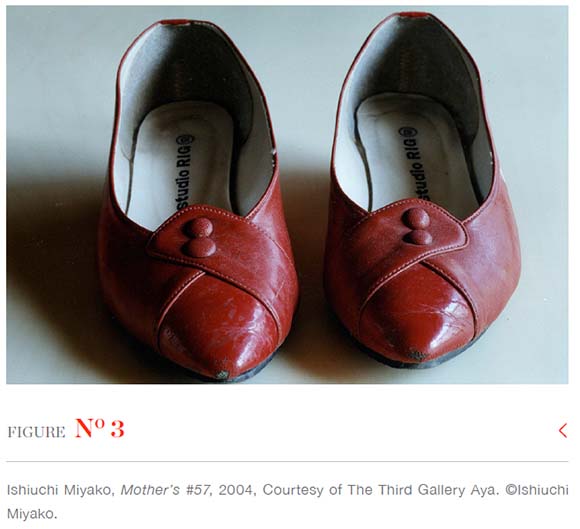

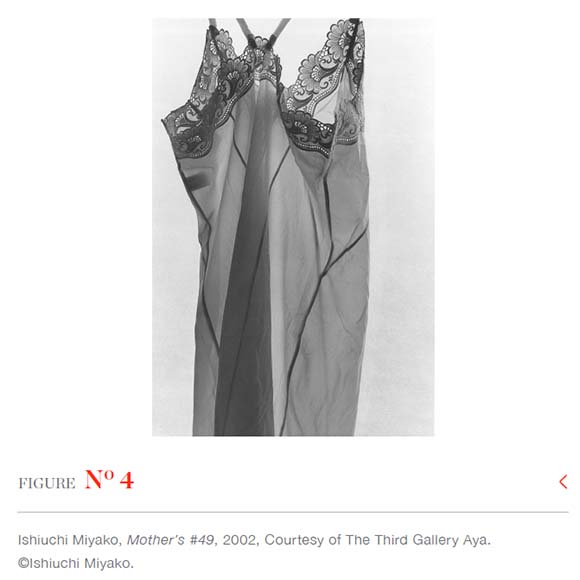

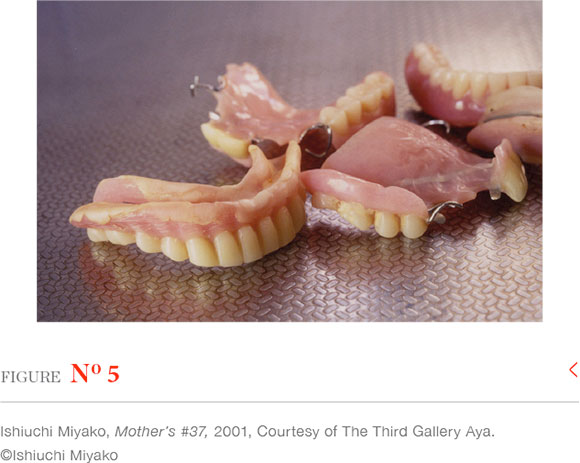

Mother's (Figures 1-5) combines large, close-up black and white silver gelatin prints and colour C-types characterised by their masterful execution. The quality of the images and the use of frontal and symmetrical compositions link them with traditional monumental representations. These sophisticated photographs are not digitally altered, as Ishiuchi uses a 35-mm camera without a tripod (O'Brian 2012:4), and yet the artist's intervention is made clear through the careful attention to composition and display. Ishiuchi chose and photographed her mother's possessions along with glimpses of her mother's ageing skin. Due to their outsize scale and stark isolation, these fragments lose part of their connection to the body and become, like the other objects, elements that may be read as a referent rather than a representation. From the very start, the process of choosing, placing, and photographing her mother's objects was presented through a biographical narrative as a record of a mother and daughter's relationship. In the press release for the fifty-first Venice Biennale, curator and commissioner Michiko Kasahara sets the precedent, explaining the artist's creative process as one in which 'Ishiuchi has carefully selected a variety of "things" left by her mother as a way of quietly observing their relationship, which she reports as discordant, while contemplating a "sadness beyond imagination"' (Kasahara 2005:2). In turn, Ishiuchi points to the discomforts and advantages provided by a moving biographical reading, remarking that:

Commissioner Kasahara wrote about me and my mother in the Biennale literature. At first, I thought a mother-daughter conflict was such a cliché and didn't like to talk about it much. But many people came to see my show in Venice because they had read about that. (Itoi 2006:sp)

Kasahara not only writes about the mother's life, but also adds details about the mother-daughter relationship at the time of her death, inserting the work into a narrative in which the installation appears to guarantee access to the artist's private world. Such a narrative is a successfully emotive promotion of the work in that it appears to guarantee access to offering an intimate yet recognisable experience. In response to this, the artist expresses a key ambivalence here: she feels the narrative stultifies and narrows the work into a stereotype but simultaneously offers the opportunity for greater visibility.

In the case of Ishiuchi, while the process of achieving visibility was unquestionably successful, this biographical association seems to have stuck, even though her subsequent work has emphasised the material rather than the personal. Following the Venice Biennale, Ishiuchi received several important commissions to photograph everyday objects (the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum invited her to photograph everyday objects that had belonged to victims of the atomic bomb, and the Museo Frida Kahlo commissioned her to photograph Kahlo's possessions), and her work was shown at significant institutions such as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the J. Paul Getty Museum. The two series, Hiroshima (2008) and Frida (2013), both reproduced the photographic style and composition used in Mother's: the isolated, at times translucent, and almost suspended quality of the objects photographed allows us to pay close attention to their material properties and aesthetic qualities. However, Mother's continues to be exhibited with a biographical framing. In 2018, when five photographs from the Mother's series entered the MET's collection (Alfred Stieglitz Society Gift), associate curator Mia Fineman expanded on the biographical strategy and included a version of Kasahara's quote:

Ishiuchi's mother was diagnosed with liver cancer and died within a few months. An only child, her father already gone, the artist was left with her deceased mother's belongings. In an attempt to cope with what she described as 'a grief surpassing imagination,' Ishiuchi began to photograph her mother's possessions: her lipsticks and lingerie, her shoes and slippers, her dentures, her hairbrush still tangled with strands of her hair. (Fineman 2019:sp)

Curator Mia Fineman's biographical text for MetCollects not only has a more sentimental tone but also includes inaccuracies: as Ishiuchi herself has pointed out in reviewing the present article, she is not an only child. Regardless of the artistic trajectory developed by Ishiuchi since the Venice Biennale, the artist herself, her lived experiences and her emotions are once more put in the spotlight.

It is true that, broadly speaking, possessions are often understood as connected to our sense of self and our memories; in this sense, drawing on the artist's lived experiences in order to further analyse and understand works like Mother's seems reasonable. In his study of the meanings of possessions and consumer culture, Russell W. Belk theorises possessions as 'extensions of self' and argues that '[i]t seems an inescapable fact of modern life that we learn, define, and remind ourselves of whom we are by our possessions' (Belk 1988:160). Although his use of the notion of 'self' is ambiguous, with problematic oppositions between an extended and non-extended self, what I find of great value in Belk's analysis is the fact that our relationship with certain objects - our reaction and interaction - is often conditioned by our perception of these as part of the subject. However, I believe that if we turn our attention to recent studies on material culture, we can add nuance to this point through a better understanding of the social role of possessions and, in turn, of the qualities put into play by Ishiuchi's photographic series.

In his book Stuff (2010), anthropologist and material culture theorist Daniel Miller challenges our understanding of material possessions as 'symbolic representations' (Miller 2010:48). Miller argues that everyday objects are not merely at our service, helping us perform tasks or representing us, but rather key cues in shaping our perception, expectations, and interactions with the world. Instead of passive and secondary, the material world is revealed as having great power over us and our experiences. Miller describes this power as 'humble,' in that it draws strength from the very fact that everyday objects and the material settings we inhabit, generally go unnoticed and are 'taken for granted' (Miller 2010:50). Looking back at Ishiuchi's work in this light, the mundane objects featured in Mother's, Hiroshima, and Frida, unearthed, decontextualised, and enlarged by the photographs, are stripped of their humility, pulled out of their concealing familiarity, and set at the centre of observation and analysis. This gesture could be seen to have further significance if we consider cultural specificities such as the aesthetic considerations and attention given to natural material properties (texture, irregularity, patina, and decay) in Japanese artistic and craft traditions, as well as the value and respect for objects in animistic traditions such as Shintoism, or their implications as sites of remembrance through, for example, the influence of Confucianism.9 Thus, though common understandings of possessions as representing or tracing back to the self doubtlessly offer grounds for biographical associations, such a perspective misses important aspects and associations for Ishiuchi's work.

My modest knowledge of Japanese culture and traditions precludes any further understanding in this direction, as would be the case for the average international visitor at a major exhibition. The limitations and concerns of intercultural curatorial practices have been sharply exposed by the aforementioned art historians Angela Dimitrakaki and Chin-Tao Wu.10 However, what I wish to highlight here is that, beyond mere sentimentalism, it is in the face of such difficulties that biographical references are strongest at heightening visibility. Using biographical narratives is a powerful curatorial and critical tool to bridge distances when addressing broad, disparate, and international audiences. Audience engagement is one of the key concerns of contemporary museum theory and practice, especially in the context of a major international exhibition like the Venice Biennale, with almost one hundred competing exhibitions, from those of the Giardini della Biennale to other venues spread out across Venice. The complexities of family relationships, loss, grief and the process of drawing near to someone through their belongings speak to a broad audience, as one of the artist's comments suggests when she states that 'by exhibiting my Mother's series in Venice [...] she stopped being my private mother and became everyone's mother' (O'Brian 2012:4). Such engagement, as Ishiuchi hints at in her comments, is valuable both to artists and curators. Nonetheless, the fundamental problem with such biographical readings lies in their scientific weakness and their lack of nuance when the work is seen as proof or a confirmation of what we already think we know about the artist's private self and lived experiences. The biographic narrative then precedes the autobiographical qualities of the work and, as such, becomes problematic.

An important body of work has focused on a revision of art historical methods. Griselda Pollock questioned traditional models of art history relying on 'the metaphor of reading' that considers artworks as a 'transparent screen through which you have only to look to see the artist as a psychologically coherent subject originating the meanings the work so perfectly reflects' (Pollock 1999:98). Mieke Bal points in this direction when, in her discussion of Louise Bourgeois's Cells, she speaks of 'memory traps' (2002:165-66). Bal argues that the objects and fragments used by Bourgeois 'are traps because the memories that inhabit the work cannot really be "read" as narratives. They are personal, while the works, made public, are no longer uniquely bound to one person's history' (Bal 2002:165-66). Bal goes on to expose the underlying assumption that the work '"betrays" the subject's self because it hides something (a memory) that may be revealed if "expertly read"' (Bal 2002:165-66). Such beliefs seems particularly present in the case of artists perceived as non-normative due to their gender, place of origin, or lived experiences. Biographical readings work as a stabilising force, comfortably labelling or situating discordant practices.

Taken together, the visibility, the grounds for engagement, and the narrative stability offered by the use of the biographical all explain the newfound success of this interpretative tendency amid the art world's international expansion. The question, however, remains: what is there in the work that lends itself to such readings, and how is this language different from that adopted by feminist practices in the 1970s and 1980s? While the previous pages have shown how the presentation or representation of everyday domestic objects and possessions in the work of many artists at the turn of the twenty-first century aroused an immediate link with the biographical, there has been a shift in visual language in later practices. Ishiuchi's visual language is detached and, at times, clinical. Fragmentary views of the mother's ageing skin, and objects that support the body through its decline, such as dentures, are presented alongside textiles arranged to create beautiful translucent effects. Hung over windows, and covered with tracing paper, they appear in the photographs as if ready for X-raying or dissection. Similarly, other objects appear against metallic and green rubber surfaces that are reminiscent of medical and forensic tables, designed for detached scrutiny. These associations with frames in which the body is scrutinised and dissected may evoke a distance, but also offer aesthetic respite to the viewer upon confronting him or her with the passage of time, decay, loss, and death. In this sense, it deviates from early feminist practices, often playing upon a directness and confrontation only softened through humour and irony.

Let us return to the aforementioned early feminist collaborative piece Womenhouse (1972), where the material qualities and properties of everyday domestic objects are arguably equally central but, unlike Ishiuchi's photographs, characterised by rawness and directness. A messy bed, a mannequin trapped in the linen closet, or dirty menstruation supplies forced the viewer of Womenhouse to confront discomforting aspects of women's everyday domestic experiences. On the other hand, and similarly to Lumbreras's observation of the positive reception that followed Mona Hatoum's alignment with a minimalist aesthetic (Lumbreras 2011), the visual language and composition of Ishiuchi's photographs, in its clean and aseptic beauty, is more digestible.

The use of domestic objects and possessions, together with the ambivalence and subtle contradictions between visual language and content, lend this piece to personalist and biographical interpretations. As I have argued, this is both the reason for and the tool through which the work accesses a high degree of visibility. While at the turn of the twenty-first century, audiences may find special appeal in autobiographical narratives, critical and curatorial discourses addressing a broad and disparate international audience find in the biographical a tool to bridge cultural distances and build engagement that may not have been necessary or even desirable in the institutional reception of earlier Euro-American feminist art practices. Paradoxically, this very process of visibilisation precludes further understanding and interpretation of the work: in its categorisation as self-representation, especially in the case of artists identified as "non-western", dissident, and discomforting aspects or broader cultural specificities are resolved as linked to the individual. Thus, the mechanisms of visibility necessary for political or critical reflections on notions of home and domestic life have also become devices of depoliticisation.

Notes

1 . For an interesting critical revision of the research on the conception and understanding of the notion of 'home' in Euro-American cultures from a multidisciplinary perspective, see Mallett (2004).

2 . For a brilliant analysis of the evolution in the understanding of the home as a space of tension in its potential as a site of normativization and oppression see Adrian Forty's Objects of desire (1986), from the perspective of design history, and Pier Vittorio Aureli and Maria Shéhérazade Giudic's 'Familiar Horror: Toward a Critique of Domestic Space' (2016), from the perspective of architecture. Furthermore, for a critical exploration of domesticity, the middle-class family, and its place in the development of capitalist society see Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall's Family fortunes (1987).

3 . The Women's Art Movements of the 1970s, as referred to here, took place within the framework of the Women's Liberation Movements in Western Europe and North America in the 1960s and 1970s, with the United States as an initial force. Visibilising the power structures that relegated women to the sphere of the private and the oppression that took place in the domestic sphere was central to these movements. At the same time the shared experiences tackled and represented by these movements where limited - Whitney Chadwick recalls how during the 1970s it was primarily white, middle-class women who organised awareness groups to share their personal experiences (Chadwick 2002). As the Black Women's Manifesto already pointed out in 1970, 'it is idle dreaming to think of black women simply caring for their homes and children like the middle-class white model' (1970-75:20) and thus, race and class connotations will be a key subject of debate and revision in subsequent stages of the movements.

4 . Here Hannah Arendt's definition of the depoliticising role of the private and the public in modern societies is key (Arendt 1998).

5 . The term "non-western" while highly problematic and contested in the context of recent cultural studies and postcolonial theory, is used here under quotation marks precisely to highlight the Eurocentric and homogenising perspectives and attitudes underlying the Euro-American artworld. For a good overview on the issues raised by this concept in the context of Euro-American attempts at cosmopolitanism, see Rao (2017).

6 . In her book Please touch, Mileaf speaks of 'tactile vision' in relation to Dada and surrealist objects as a way to address the role that bodily desire plays in aesthetic perception.

7 . For a revisionist study of Presser's proposal, see Dekker (2002:13-37).

8 . See Rak (2013).

9 . My understanding of the cultural associations present in certain aspects of Ishiuchi's work owes to my conversations with Aitana Merino, a specialist in Japanese calligraphy and contemporary Japanese art.

10 . For a further reflection on the implications of the cultural and historical specificity of the conceptual and terminological framework of art history, see Chin-Tao (2007) and Dimitrakaki (2004).

References

Appadurai, A (ed). 1986. The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Arendt, H. 1998. The human condition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Arnold, M & Meskimmon, M (eds). 2016. Home/land: Women, citizenship, photographies. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [ Links ]

Aureli, P. V., & Giudici, M. S. 2016. Familiar horror: toward a critique of domestic space. Log, 38(38), 105-129. [ Links ]

Bal, M. 2002. Autotopography: Louise Bourgeois as builder. Biography 25(1):180-202. [ Links ]

Barthes, R. 1982 [1980]. Camera lucida: Reflections on photography. Translated by R Howard. New York, NY: Hill & Wang. [ Links ]

Beal, F. 1970. Double jeopardy: To be black and female, in Woman's Manifesto, edited by E Holmes Norton, M Williams, F Beal & L La Rue Black. New York, NY: Third World Women's Alliance: 19-34. [ Links ]

Belk, R. 1988. Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research 15(2):139-68. [ Links ]

Bennett, J. 2005. Empathic vision: Affect, trauma, and contemporary art. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Betterton, R. 1996. An intimate distance: Women, artists and the body. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Betterton, R. 2000. Undutiful daughters: Avant-gardism and gendered consumption in recent British art. Visual Culture in Britain 1(1):13-30. [ Links ]

Buchler, J (ed). 2011. Philosophical writings of Peirce. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. [ Links ]

Bydler, C. 2004. The global art world, Inc.: On the globalization of contemporary art. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. [ Links ]

Chadwick, W. 2002. Reflecting on history as histories, in Art, Women, California: 1950 2000: Parallels and intersections, edited by DB Fuller & D Salvioni. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press:19-42. [ Links ]

Chin-Tao, W. 2007. Worlds apart: Problems of interpreting globalised art. Third Text 21(6):719-731. [ Links ]

Davidoff, L & Hall, C. 1987. Family fortunes: Men and women of the English middle class, 1780-1850. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Dekker, R. 2002. Jacques Presser's heritage: Egodocuments in the study of history. Memoria y Civilización 5:13-37. [ Links ]

Dimitrakaki, A. 2004. Researching culture/s and the omitted footnote: questions on the practice of feminist art history, in Over here: International perspectives on art and culture, edited by J Fisher & G Mosquera. New York, NY & Cambridge, MA: The New Museum of Contemporary Art & MIT Press:88-101. [ Links ]

Dimitrakaki, A. 2016. Gender, artwork and the global imperative: A materialist feminist critique. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Dykstra, J. 2000. Book review: Vestiges: Masao Yamamoto, Miyako Ishiuchi, Yukio Oyama. Art on Paper 5(1):82-83. [ Links ]

Eisler, C. 1987. 'Every artist paints himself': Art history as biography and autobiography. Social Research 54(1):73-99. [ Links ]

Fineman, M. 2019. Miyako Ishiuchi. MetCollects. [O]. Available: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/online-features/metcollects/ishiuchi-miyako Accessed 4 March 2023. [ Links ]

Fisher, J & Mosquera, G (eds). 2004. Over here: International perspectives on art and culture. Cambridge, MA & New York, NY: The New Museum of Contemporary Art & MIT Press. [ Links ]

Forty, A. 1986. Objects of desire: Design and society since 1750. London: Thames & Hudson. [ Links ]

Fuller, DB & Salvioni, D (eds). 2002. Art, Women, California: 1950-2000: Parallels and intersections. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Gammel, I (ed). 1999. Confessional politics: Women's sexual self-representations in life writing and popular media. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. [ Links ]

Gibbons, J. 2007. Contemporary art and memory: Images of recollection and remembrance. London & New York: IB Tauris. [ Links ]

Gilmore, L. 1994. Autobiographics: A feminist theory of women's self-representation. Ithaca, NY & London: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Golshiri, B. 2009. For they know what they do know. E-flux Journal 8(Sept.):1-17. [ Links ]

Gudmundsdóttir, G. 2003. Borderlines: Autobiography and fiction in postmodern life writing. Amsterdam: Rodopi. [ Links ]

Gupta, S & Padmanabhan, S (eds). 2017. Politics and cosmopolitanism in a global age. 1st ed. London: Taylor & Francis (Ethics, Human Rights and Global Political Thought). Available: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781315661841 Accessed 7 July 2023. [ Links ]

Hall, S. 1996. Who needs identity? in Questions of cultural identity, edited by S Hall & P du Gay. London: SAGE:1-17. [ Links ]

Hall, S & du Gay, P (eds). 1996. Questions of cultural identity. London: SAGE. [ Links ]

Hanisch, C. 1970. The personal is political, in Notes from the second year: Women's liberation, edited by F Shulamith & A Koedt. Major writings of the radical feminists. New York, NY: Radical Feminism:76-78. [ Links ]

Hernández Sánchez, D (ed). 2002. Estéticas del arte contemporáneo. Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. [ Links ]

Hirsch, M. 1989. The mother/daughter plot: Narrative, psychoanalysis, feminism. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Hoaglund, L. 2013. Behind 'Things left behind': Ishiuchi Miyako. Impressions 34(3):84-95. [ Links ]

Holmes Norton, E, Williams M, Beal, F & La Rue Black, L (eds). 1970. Woman's Manifesto. New York, NY: Third World Women's Alliance [ Links ]

Huggan, G. 2001. The postcolonial exotic: Marketing the margins. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ishiuchi, M. 2002. Mother's. Tokyo: Sokyu-sha. [ Links ]

Ishiuchi, M, Michiko, K & Biennale di Venezia. 2005. Ishiuchi Miyako: 'Mother's 2000-2005: traces of the future'. Tokyo: Japan Foundation. [ Links ]

Ishiuchi, M & Mitsuda, Y. 2015. Ishiuchi Miyako. Aperture 220(220):122-135. [ Links ]

Ishiuchi, M & O'Brian, J. 2012. On ひろしま hiroshima: Photographer Ishiuchi Miyako and John O'Brian in conversation. The Asia-Pacific Journal 10(7):sp. [ Links ]

Itoi, K. 2005. Photography: A mother's close up; at the Venice Biennale, Miyako Ishiuchi represents Japan with her memorable pictures of modern life. Newsweek (61):61-61. [ Links ]

Jones, A. 1994. Dis/playing the phallus: Male artists perform their masculinities. Art History 17(4):546-584. [ Links ]

Jones, A. 2006. Self/image: Technology, representation and the contemporary subject. London & New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jones, A. 2008. 1970/2007: The return of feminist art. X-Tra 10(4): sp. Available: https://www.x-traonline.org/article/19702007-the-return-of-feminist-art/ Accessed 15 January 2023. [ Links ]

Kasahara, M. 2005. Japan Pavilion at the 51st International Art Exhibition, the Venice Biennale in 2005. [Press release]. [O]. Available: https://www.jpf.go.Jp/e/project/culture/exhibit/international/venezia-biennale/art/51/ Accessed 20 February 2016. [ Links ]

Kauffman, L. 2000. Malas y perversos: Fantasías en la cultura y el arte contemporáneos. Valencia: Cátedra. [ Links ]

Lejeune, P. 1989 [1971]. On autobiography, edited by P Eakin, translated by K Leary. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Lacy, S (ed). 2010. Leaving art: Writing on performance, politics, and publics, 1974-2007. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Lacy, S & Lippard, L. 2010. Political performance art, in Leaving art: Writings on performance, politics, and publics, 1974-2007, edited by S Lacy. Durham, NC: Duke University Press:151-159. [ Links ]

Lumbreras, M. 2011. Éxito, (hiper)visibilidad, ambivalencia: Las instalaciones de Mona Hatoum. Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. [ Links ]

Mallett S. 2004. Understanding home: A critical review of the literature. The Sociological Review 52(1):62-89. [ Links ]

Martínez Oliva, J. 2005. El desaliento del guerrero: Representaciones de la masculinidad en el arte de las décadas de los 80 y 90. Murcia: Cendeac. [ Links ]

Massumi, B. 2002. Parables for the virtual: Movement, affect, sensation. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Meskimmon, M. 1996. The art of reflection: Women artists' self-portraiture in the twentieth century. London: Scarlet Press. [ Links ]

Mileaf, J. 2010. Please touch: Dada and surrealist objects after the readymade. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press & University Press of New England. [ Links ]

Miller, D. 2010. Stuff. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Nochlin, L & Reilly, M. 2007. Global feminisms: New directions in contemporary art, edited by the Brooklyn Museum. London & New York, NY: Merrell. [ Links ]

Pedersen, C. 2005. The indefinitive self: Subject as process in visual art. Queensland: University of Technology. [ Links ]

Peirce, C. 2011. Logic as semiotic: the theory of signs, in Philosophical writings of Peirce, edited by J Buchler. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. [ Links ]

Pollock, G. 1987. Vision and difference: Feminism, femininity and histories of art. London: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Pollock, G. 1999. Differencing the canon: Feminist desire and the writing of art's histories. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Rak, J. 2013. Boom! Manufacturing memoir for the popular market. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. [ Links ]

Rao, R. 2017. The elusiveness of "non-western cosmopolitanism", in Politics and cosmopolitanism in a global age, edited by S. Gupta and S. Padmanabhan. 1st ed. London: Taylor & Francis (Ethics, Human Rights and Global Political Thought). Available: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e79781315661841 Accessed 7 July 2023. [ Links ]

Raquejo, T. 2002. Sobre lo monstruoso: un paseo por el amor y la muerte, in Estéticas del arte contemporáneo, edited by D Hernández Sánchez. Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca:51-87. [ Links ]

Roberts, J. 1998. The art of interruption: Realism, photography, and the everyday. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Robinson, H (ed). 2001 [1980]. Feminism-art-theory: An anthology, 1968-2000. London: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Rosler, M. 2001 [1980]. Well, is the personal political?, in Feminism-art-theory: An anthology, 1968-2000, edited by H Robinson. London: Blackwell:95-96. [ Links ]

Schapiro, M. 1972. The education of woman artists: Project Womanhouse. Art Journal 31(3):268-270. [ Links ]

Shulamith, F & Koedt, A (eds). 1970. Notes from the second year: Women's liberation. Major writings of the radical feminists. New York, NY: Radical Feminism. [ Links ]

Smith, S & Watson, J. 1993. Subjectivity, identity, and the body: Women's autobiographical practices in the twentieth century. Bloomington & Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Smith, S & Watson, J. 2002. Interfaces: Women, autobiography, image, performance. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

Smolik, N. 2008. Miyako Ishiuchi. Artforum International 47(1):481-81. [ Links ]

Stallabrass, J. 1999. High art lite: British art in the 1990s. London & New York, NY: Verso. [ Links ]

Stanton, DC. 1987. The female autograph: Theory and practice of autobiography from the tenth to the twentieth century. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Strosnider, L. 2009. Palpable visions. Afterimage 36(4):35-36. [ Links ]

Van Alphen, E. 2008. Affective operations of art and literature. RES 53/54:20-30. [ Links ]

Zarza, Clara. 2016. There is no place like home: Explorations of a dislocated self and its home in Emily Jacir's piece 'Where we come from/(im)mobility,' in Home/land: Women, citizenship, photographies, edited by M Arnold & M Meskimmon. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press:227-236. [ Links ]