Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a11

ARTICLES

Exercising agency through embodied research and the making of screendances

Kristina JohnstoneI; Tarryn-Tanille PrinslooII; Marth MunroIII

ISchool of the Arts, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. kristina.johnstone@up.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5312-0781)

IISchool of the Arts, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. tarryntanille@gmail.com (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0333-6285)

IIISchool of the Arts, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. marth.munro@up.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9065-8591)

ABSTRACT

This article reflects on a series of embodied research processes to argue that screendance-making as 'embodied practice' offers a site to exercise agency. Drawing from the notion of affordances and prosthesis, the article suggests that in screendance, the mover and the camera enter into a relationship where agency is shared. Screendance offers opportunities to experience agency not as subject-centred, but rather in a field of relation - a co-compositional mode (Manning 2016:123). Drawing from Lawrence Halprin's (1969) RSVP (Resources, Scores, Valuaction, Performance) score cycles and Ben Spatz's (2020) conceptualisation of research journeys as cyclical and reversible, the article documents a series of online and in-person movement and vocal explorations and tracks how these embodied research instances create possibilities to reflect on, and experience agency in, moments of co-creation. This article suggests that embodied practice and art-making are agentic and epistemic, which may disrupt hegemonic knowledge structures and open a window towards what Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2014:188) calls an 'alternative ecology of knowledges'.

Keywords: Screendance, embodied research, agency, co-creation.

This article reflects on our shared experiences as embodied researchers, educators and co-creators1 facilitating embodied explorations and learning processes within the area of screendance as an interdisciplinary and inherently fluid and ambiguous art form. As a team of co-creators, our embodied research through the medium of screendance is ongoing. Our engagement with and through this particular form spans several iterations, some of which took place online and some in person. Working with an embodied and artistic research approach, we2 view each iteration as a relatively stable point that allows us to reflect, offers cumulative insight, and transforms our practice. This article draws from four iterations of our joint screendance-making project. We acknowledge that although these iterations unfolded chronologically, they inevitably become entangled in our discussion.

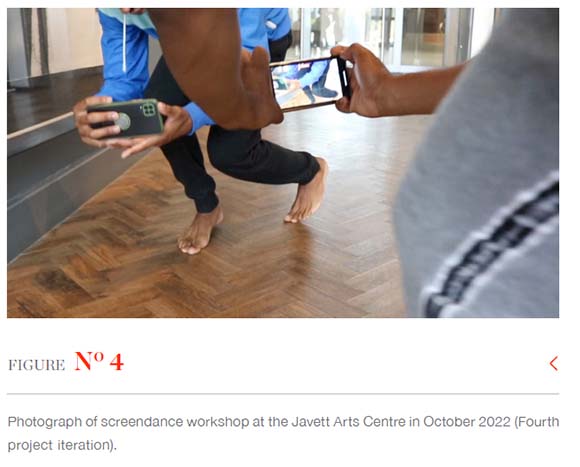

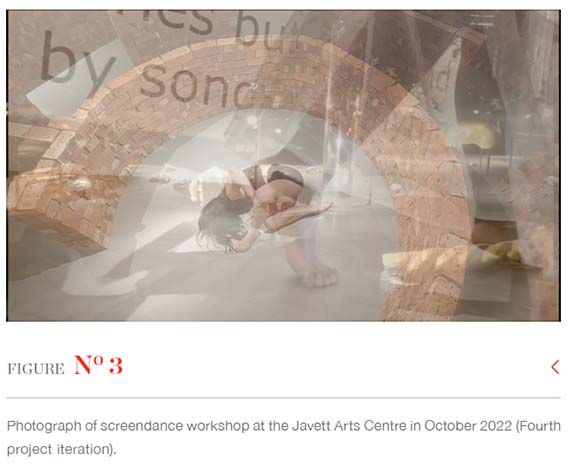

The first iteration involved working with students at the University of Pretoria's School of the Arts: Drama. The process brought together third-year undergraduate students studying Physical Theatre and Digital Media in a collaborative project that culminated in creating screendances filmed in and around the Javett Arts Centre - an art gallery associated with the University of Pretoria. This first instance of collaborative practice occurred in 2020, which saw teaching and learning taking place primarily online due to the Covid-19 pandemic. As a result, much of the project required us to search for ways to facilitate embodied practice in virtual spaces, and we saw students conducting most of their embodied research and being witnessed by others online in front of a laptop camera. Towards the end of 2020, students were able to return to the university campus for limited amounts of time. Forming pairs of one Digital Media and one Physical Theatre student, each partnership was invited to conceptualise and develop a screendance work as a final assessment outcome. The Javett Arts Centre was a central site for these explorations. The findings of this first iteration were shared in an online workshop and presentation at the Arts, Access, and Agency Conference hosted by the University of Pretoria in October 2021.3 The online workshop and presentation, which formed our second project iteration, also offered a series of movement, voice, and camera explorations that combined our practices as artists and facilitators to articulate the embodied research process that we felt emerged through our work with students. The third iteration saw us working with a new group of third-year undergraduate Physical Theatre and Digital Media students and returning to the Javett Arts Centre at the end of 2021, this time entirely in-person. The fourth and currently last iteration also took place at the Javett Arts Centre over two days and involved participants from both inside and outside the University at various levels of professional artistic practice who responded to an open call for participation.

Surfacing from these various project iterations is the proposition that embodied approaches to collaborative screendance-making offer a place to 'exercise' agency. Agentic possibilities emerge through the processes of practising, creating, and recreating through art-making as a relational practice. This aligns with a commitment to transformative and decolonial teaching and creative practices. Our intent is not to prosthetically attach the language of decolonisation and decoloniality to our practices but to recognise in the art-making and embodied process possibilities for methodologies, epistemologies, and pedagogies that offer counter-narratives to normative and colonially-informed research paradigms. The deeply layered and relational process described here resonates with Lesley Le Grange's understanding of a decolonised curriculum4 as 'a spiral of ongoing cycles of inquiry' (Le Grange 2021:10). These cycles of inquiry operate on multiple levels. Firstly, we, as researchers, undergo a spiralling process of inquiry through each re-iteration of this project. Secondly, the process we offer participants invites a layered and cyclical embodied and artistic research practice, which we articulate using Lawrence Halprin's (1969) RSVP (Resources, Scores, Valuaction, Performance) Cycle and Ben Spatz's (2020) conceptualisation of research journeys as cyclical and reversible.

In this cyclical process, subjectivity emerges not as individual, but relational and 'ecological' (Le Grange 2016:9). Thus, by positioning art-making, in this case, collaborative screendance-making, as agentic and epistemic, we suggest that hegemonic knowledge structures may be disrupted, and a window opened towards what Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2014:188) calls 'an alternative ecology of knowledges'. To advance this argument, the article revisits, reiterates, and remakes the embodied explorations that informed our screendance-making project as a way to both document our practice and trace how these instances of embodied research create opportunities to reflect on and experience agency and moments of co-creation. Following a contextualisation of key concepts, the article draws from the cumulative research insights that emerged from the four project iterations and offers a reflexive account of some of the explorations developed with students/participants.

Contextualising screendance

Before unpacking our practice of screendance-making, the following section offers a brief overview of our understanding and use of the term 'screendance'. Inherently multidisciplinary in nature, screendance is an ambiguous and fluid artistic genre that is most suited to an environment in which art forms proliferate across different media, platforms, and contexts (Kappenberg 2015:26). Consequently, the definition of the term depends strongly on the work's positionality, function, and kinetic intent. Since language (either written or spoken) plays a crucial part in critical discourse as it communicates knowledge about particular areas of research, terms such as 'dance for the camera', 'video dance', 'cine-dance', and 'screendance', to name a few, recognise certain combinations of performance and modes of production, while advocating a non-hierarchical approach that refrains from favouring one discipline over another (Aldridge 2013:17; Rosenberg 2012:15).

Following Cara Hagan (2022:9-10), screendance can be considered a hypernym for a site-, camera- and edit-specific artform. As such, screendance is often informed and driven by the inherent elements of a site, a characteristic that we strongly encourage makers to continuously consider as part of their creative process, which we detail later in this article through the concept of affordances. In addition, Elliott Caplan (in McPherson 2006:24) suggests that the rectangle, whether a screen, a canvas, or a stage, is a valuable starting point for any work due to the infinite ways one can fill that rectangle. The camera and the screen then become sites of composition/choreography informed by the action of looking (Hagan 2022:9-10). Eiko Otake (2002:84) further argues that 'if what is in the frame can suggest what is outside of the frame and relate to it, viewers can sense that what they see is a part of a larger world'. This idea links to Douglas Rosenberg's (2012:69) notion of 'camera-looking', which can be described as the camera that is actively framing and supporting the performance, while entirely excluding other information. Through this act of looking, there is an acknowledgement of everything included in the frame, while everything that is deliberately cut off or excluded by the frame becomes implied. In John Berger's Ways of Seeing (1972:8) he argues that the activity of vision frames what and how one sees, making 'looking' an act of choice.5 A close-up, however, minimises that choice as the camera lens specifically frames and dictates what the viewer should see, while the camera's telescopic and microscopic qualities enable an extended vision along with an assisted way of seeing. Therefore, while an individual's vision is always active, continuously looking at how things relate to one another and the self (Berger 1972:8), the camera alters reality by proposing innovative and diverse perceptions of objects and movement (Pendlebury 2014:13).

In screendance practice, we suggest that the camera becomes a seeing prosthesis, expanding the possibilities of the body. The camera operator and mover engage with each other within the frame, extending the range of vision (Rosenberg 2012:9,69). The camera is a prosthetic as the device becomes part of and extends the invisible volume of space around the body, also known as the mover's peripersonal space. According to Sandra Blakeslee and Matthew Blakeslee (2008:3), 'the maps that encode your physical body are connected directly, immediately, personally to a map of every point in that space and also map out your potential to perform actions in that space'. Blakeslee and Blakeslee (2008:3) add that one's sense of self 'does not end where your flesh ends, but suffuses and blends with the world, including other beings'. This view meets Erin Manning's (2007:131) conceptualisation of the senses as a prosthetic to the biological body. She describes sensing as knowing 'differently, in excess of my current appreciation of "my" body', making the boundaries of the body fluid (Manning 2007:131). This resonates with a posthuman view of the body, which Katherine Hayles (1999) explains positions the body as 'the original prosthesis we all learn to manipulate so that extending or replacing the body with other prostheses becomes a continuation of a process that began before we were born' (Hayles, 1999 in Manning 2007:120). Rethinking the senses and extending the body's sensory array through a moving camera alters the body prosthetically, offering alternative and new agentic possibilities.

Dominant views of the senses often consider the eyes as the predominant organ used for seeing. Throughout our embodied research process, however, we deliberately worked towards finding different ways of looking and seeing with the body - different ways of 'knowing' (Manning 2007:131) - that not only involve the eyes. Following this embodied approach to 'sensory seeing', Claire Loussouarn (2021:72) interrogates ways in which one can work somatically with the screen, calling for a re-evaluation of the relationship to the screen as a movement practice in its own right. Loussouarn (2021:72) considers the Zoom screen as 'a place of "moving selfies" in dialogue where we can engage critically with the screen by practising seeing with the whole body'.

Drawing from the above concepts, we distinguish screendance from films, documentaries, and archival recordings of choreography, movement, or dance. In our understanding of screendance, the camera becomes a prosthesis which then attributes agency by becoming an active participant, extending the body's possibilities and accentuating a kinetic experience that is further enhanced and reconsidered during the editing phase, which is not temporally confined to post-production, but is embedded in the embodied-making continuum. As a result, screendance produces and interrogates innovative relationships between the body as both subject and object, the prosthetic camera as both witness and agent and the embedded editing process, which ultimately results in a work that can only be experienced on screen (Aggiss 2008:[sp]; Hagan 2022:9-10).

An embodied approach to screendance-making

We characterise our practice of screendance-making as an embodied approach, positioning each creative exploration facilitated with students/participants as an instance of embodied research that opens up lines of inquiry towards the co-making of an artistic work. Central to this understanding is Spatz's concept of 'embodiment as first affordance' (Spatz 2020). The notion of affordance is borrowed from James J. Gibson (1979) and describes the relationship between environment and animal. 'Affordances of the environment', writes Gibson, 'are what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either good or ill' (Gibson 1979:119). He adds that 'the possibilities of the environment and the way of life of the animal go together inseparably' (Gibson 1979:135). Transposing this concept to embodiment, Spatz (2020:71) argues that in the area of practice, embodiment is the first affordance, or 'the primary site of engagement'. Additionally, Spatz (2020:75) argues that embodiment is a 'zone of ontological engagement in which the dynamic interplays ... between perception and action, resistance and accommodation, and problem-solving and problem-finding - occur in the absence of any clear distinction between agent and substrate'.

Approaching the making of screendances as embodied practice, both from the perspective of the dancer/mover and prosthetic camera/camera person, implies a dissolution of agent and substrate as body and embodiment are positioned as the primary site of creation and knowledge exchange. This view is supported by Thomas Csordas (1990), who refers to the collapse between subject and object as crucial for understanding embodiment as a methodological approach. Spatz, who further delineates practice into embodied technique as a relatively stable, repeatable, and transmissible unit of analysis, explains that rather than assuming 'that technique operates upon or with an area of materiality that is distinct from it', it is not possible to 'separate the substrate from the technique, because we only come to know the substrate through the technique' (Spatz 2015:65). In screendance-making, the embodied process paves the way toward artistic questioning and re-questioning, cementing the onto-epistemic nature of the practice. Embodiment in this practice affords the body (and the body's prosthetically expanded peripersonal space) motion as well as the perceptual possibilities of looking, seeing, listening, hearing, sounding, tactility, proprioception, and kinesthesia, contributing to, and perhaps shaping, the agentic bodymind in action.

Cycling through embodied practice

A useful process that supports the perceptual possibilities of creating a screendance work without being product or goal-orientated is the RSVP Cycle proposed by Lawrence Halprin (1969; Williams 2021).6 Halprin's interdisciplinary model has four elements, or 'cycles', and provides a valuable framework through which to, retrospectively, make sense of the embodied screendance-making approach described here. The model consists of Resources (R), Scores (S), Valuaction (V), and Performance (P) that can be applied in any combination using any of these elements as a point of departure.

The elements in the cycle aim to make creative processes visible and describe the procedures that are inherent in creative practice. The cycle simultaneously contains and expands the creative process. Within the context of this article and our facilitation of screendance explorations, it could be suggested that Resources include all the human and physical materials as well as the theoretical and conceptual underpinnings around the notion of screendance, embodied practice, and affordance. In the case of the online explorations, the screen provided a further resource, while the Javett Arts Centre, which provided the site of in-person activities, would further serve as a crucial resource to explore the inherent site-specificity of the art form, inviting participants to respond to the various sites available in and around the Javett as affordances.

The Scores element describes the process that leads to performance-making, a sort of data-gathering, notation, and score-keeping element during which makers source their sites, as well as the vocal, instrumental, and environmental sounds that form the sound score or, as we refer to it, the soundscape. The editing process7can also be considered as a way of scoring since editing requires the compilation of specific shots into a sequence during which space is reconsidered and reconfigured from a two-dimensional flat screen to an implied three-dimensional experience.

The Valuaction phase provides opportunities for critical reflection and analysis of the momentarily stable results, which along with decision-making and selection, contribute to the overall production. Here, the editing phase becomes pertinent once more as makers were not only required to make creative choices during the playful editing process but also reflect on their post-production product, questioning whether this would be the final 'performance' or whether there would be a return to one of the previous cycles. We facilitated the Valuaction cycle in collective viewings and group conversations, encouraging certain re-edits, reconsiderations, and shifts. Eventually, the Resources, Scores, and Valuaction phases culminated in the Performances, which in this context are the screendances. Should we alter the order of this cyclical process and use Performance as a point of departure, this could result in a process where movers respond to sites through improvised performance to generate Resources or Scores.

A cyclical and reversible creative process

The cyclical and reversible journey proposed by Halprin's RSVP Cycle meets Spatz' conceptualisation of (embodied) research, which Spatz (2020:7) describes as moving in two directions: first in the direction of opening, which is characterised by 'entering, unfolding, delving into, uncovering, expanding, drawing near', and then in the direction of 'closure', which is a movement of 'folding up, getting out of, gaining distance'. This understanding of research lends creative and embodied practice to an ever-expanding field as the practitioner-researcher continually crosses through the boundaries of known and unknown as they cycle through creative processes. According to Spatz (2020:15), this cyclical crossing of boundaries is essential for 'getting at things in different ways' and undoing entrenched colonially-informed, epistemological hierarchies. Using the RSVP Cycle and approaching screendance-making as an embodied, cyclical and reversible research journey, we invited our screendance participants into a radically open creative process that resists predetermined stories or preconceived notions of aesthetic or 'art'. We perceive these radically open creative processes as crucial for facilitating a transformative and decolonial practice.

Recognising that decoloniality is not a singular movement or concept, we draw from the broad understanding that a decolonial praxis seeks to destabilise coloniality's hegemonic discourses in search of epistemological alterity (Grosfoguel 2011:n.p.). Santos (2014:201), who advocates for epistemic justice through the concept of an 'ecology of knowledges', explains that knowledge is not a representation of reality, but rather an intervention in reality. With this in mind, an embodied approach to screendance-making offers an open and unfolding process that does not aim to represent or reflect a pre-existing idea, story, or concept, but rather seeks to attend to emergent logics, aesthetics, and suggestions of stories through a deeply embodied and perceptual practice. These emergent stories are held together with 'slender threads' of logic, a notion borrowed from Achille Mbembe (2017), whose unpacking of a ghostly paradigm in black novelistic writing troubles conventional understandings of cause and effect. Mbembe (2017:148) explains that in a ghostly paradigm,

(e)verything functions according to a principle of incompletion. As a result, there is no ordered continuity between the present, the past, and the future. And there is no genealogy - only an unfurling of temporal series that are practically disjointed, linked by a multiplicity of slender threads.

Similarly, by allowing narrative cause and effect to remain open in the embodied making process, room is created for not-predetermined meanings and stories to 'unfurl', to use Mbembe's expression, surfacing an artistic and choreographic logic, or 'aesthetic', of its own. Importantly, we also observe that an embodied-making process is not only an aesthetic or artistic intervention, but also, referring back to Santos (2014:201), an ethico-political one. Approaching screendance-making as a cyclical and reversible process not only offers a refiguring of narrative possibilities and artistic boundaries and choices, but also provides opportunities to exercise agency. Within this ethico-political process, agency is not static/fixed nor distinct but relational and thus inevitably distributed. Such a process engages with epistemological and ontological concerns, as it questions ways of knowing and doing, as well as ways of being in the world, which we align with decolonial praxis. These concerns extend to our artistic and pedagogical approaches and, specifically, how these approaches interact with conceptions of agency and co-creation.

Artistic co-creation and reconfiguring agency

The explorations detailed later in this article suggest a cyclical embodied research process that tracks the relationship between the material and the practitioner/ embodied researcher(s). This process shapes and navigates agency at every moment of the practice. This supports Karen Barad's new materialist perspective that a focus on practices/doings/actions, in contrast to social constructivist accounts of the world, 'bring to the forefront important questions of ontology, materiality and agency' (Barad 2003:802-803). Positioning screendance-making as embodied research emphasises the process as, what Spatz (2020:4) calls, 'an active journey' and an 'essential process of knowing together'. Such a journey cannot unfold along a linear path - recalling Mbembe's earlier-mentioned evocation of narrative as a disjointed temporal series - and has a relational ontology. Barad describes this through the concept of intra-action. Distinct from 'interaction', she explains that intra-action sees entities not as ontologically separate or distinct, but rather considers that the ontological status of entities depends on their relation (Barad 2003; Tikka 2018).8 Intra-actions are 'performative and emergent events' (Tikka, 2018:n.p.) that blur any clear subject and object distinction, undoing conventional modes of causality. Working from this relational ontology, Barad (2011:134) replaces the classical Cartesian cut with an 'agential cut', which throws the question of agency to a matter of ontological indeterminacy. Agential cuts, as Barad further explains, 'enact a local resolution within the phenomenon of the inherent ontological indeterminacy', which is better understood as a momentary stabilisation within an unfolding and continually emerging event. We propose that each instance of artistic co-creation, or each moving image fleetingly captured, offers a momentary stabilisation in the relational, embodied practice of screendance-making.

An alternative view of subjectivity emerges from this embodied and perceptual approach to creative practice. Following Manning (2016:140), a 'subject' in this practice is not an individual, volitional, and intentional human agent. Rather, Manning, whose thinking is informed by autistic (neurodiverse) perception, proposes that 'subjectivity is in the making, in the field. Subjectivity is not felt as predetermining' (Manning 2016:140). She draws from Alfred North Whitehead's process philosophy to read the subject not as an activator of the event but as emergent from within the act itself. This argument aligns with our monist description of people as multimodal bodyminded beings (or selves) manifesting in action. Screendance-making as a cyclical, reversible, and embodied research process unfolds in 'a field of relation', which according to Manning (2016:117), 'is always actively co-composing with the actual in its emergence'. She further explains that tuning into what is emerging, in this case into the creative and embodied research process, is 'to see the potential of worlds in the making' and 'involves becoming more attuned to event-time, the nonlinear lived duration of experience in the making' (Manning 2016:15). Attuning to agentic possibilities is furthermore linked to the workings of the senses. It is exercised through a perceptual practice. Mbembe (2017:120) explains that the emergence of subjectivity 'is experienced by attending to the senses (seeing, hearing, touching, feeling, tasting)', which may be expanded to include the additional senses of pain, temperature, kinesthesia, and proprioception. As argued earlier, Manning (2007:24) further conceptualises the senses as 'prosthetic devices, always more and less than single and singular bodies'. She writes (2007:xiii) that 'the senses prosthetically alter the dimensions of the body' and thus 'foreground a processual body', a body of becoming, emergent, and unfolding.

Conceptualising the senses as prosthetics, as devices that provide entry into and interact with our environment, allows us to think of sensory and perceptual practices as extending beyond our biological body, becoming posthuman, as suggested by Hayles (1999 in Manning, 2007) and argued earlier. In the embodied screendance-making process, we explore how the senses take us into new configurations with the environment through affordances and how the camera and the screen become extensions, or 'prostheses', in our ability to engage with the outer world. This echoes David Ekdahl, who argues that there is an increasing awareness in research surrounding the body and digital technology that accounts of embodiment need to consider how 'our living and experiencing bodies quite literally extend into virtual space and give shape to our cognition' (Ekdahl 2021:3). In this light, Ekdahl argues for a reconsideration of the digital space 'as a field of bodily affordances' (Ekdahl 2021:3).

We propose that an embodied screendance-making process tracks an ever-shifting and shaping relationship between the practitioner/embodied research(er) and the material that emerges through a prosthetic sensory engagement with the environment. Agency becomes distributed as the practitioner is not positioned as a singular, human, volitional agent who decides what to see or capture, or how to move, sound, vocalise, or act upon the environment, but rather as a co-creating subject emerging through relational intra-action.

Embodied explorations: Lines of inquiry

The next section details some of the embodied research processes and explorations that feed into our use of screendance as a decolonial framework for creative practice and art-making. As mentioned in the introduction, the explorations are sourced from four iterations of a shared screendance-making practice.

The first iteration, in 2020, unfolded with a group of third-year undergraduate Digital Media and Physical Theatre students. The Covid-19 pandemic heavily impacted the teaching and learning situation in 2020, and as a result, we guided students in embodied explorations that first took place online and then moved to an in-person space at the Javett Arts Centre on the University of Pretoria campus. Moving from their private spaces and laptop screens, students were invited to transpose material they created online by exploring the affordances of the gallery site (both the architecture and the artworks contained therein) to create short screendance works.

The process resembled Halprin's RSVP Cycle, with students being encouraged to move fluidly back and forth between resource gathering, scoring, and reflection towards a relatively stable moment of performance. Reflecting on this first collaborative effort as embodied researchers, educators, and co-creators, we began to clarify and articulate some embodied explorations that we felt could productively invite our students into experiences of co-creation, both in a solo format with a device, or in small groups with several movers and moving devices. We noticed in this first iteration that the students gravitated towards using recorded music to accompany their works and resolved to pay closer attention to how we might also invite the body's breath, voice, and sounds in relationship with the environment as organic extensions of movement.

The second iteration developed as an online workshop and presentation as part of the Arts, Access, and Agency Conference at the University of Pretoria in October 2021 and provided the impetus for the writing of this paper. For the conference, we drew from insights gained from our reflective conversations following the first iteration to offer conference participants a series of explorations involving the moving and sounding/voicing body accompanied by cellphone and laptop cameras as witnesses and co-agents in the creative process.

We worked with a new group of third-year undergraduate Digital Media and Physical Theatre students for the third iteration at the end of 2021. We returned to the Javett Arts Centre, and students once more articulated a cyclical embodied research process as we invited them to work with motion, affordance, voice, sound, and a prosthetic camera mediating, extending, and co-creating their perceptual practice resulting in collaborative screendance works. In this iteration, our focus widened, and our lines of inquiries included bodyvoice9 as an extension, or rather an integral part, of the embodied practice and research process.

For the fourth and currently last iteration, a call for participation was distributed via our various artist and educator networks to take part in a two-day screendance workshop at the Javett Arts Centre. Eight participants from various artistic disciplines and with varying levels of experience signed up to participate. The participants worked in pairs to collaborate on a screendance as a performance outcome.10

In what follows, we describe a series of embodied explorations that emerged from the four project iterations, the different contexts of facilitation (teaching and learning, conference presentation, and professional workshop), and different modes of engagement (online and in-person). While the four explorations described below describe a trajectory we might follow in a workshop, they do not necessarily follow a particular chronology and cannot be ascribed to particular project iterations. Rather, they synthesise our cumulative experiences and insights gained from this shared project. These samples of embodied practice are offered as 'lines of inquiry' demonstrating the entanglement of practice and theory in embodied research. They serve as prompts to be taken up, expanded, or altered by other practitioners, suggesting the transferability of these embodied techniques. To articulate our lines of inquiry, we use a phenomenotechnical mode of writing, which sits between first- and third-person methodologies.11 This phenomenotechnical mode emphasises 'the epistemic dimension of embodied practice' (Spatz 2020:98) and enlivens the notion that the body, which includes voice, is simultaneously object and subject, both agent and substrate, continuously shifting and shaping, becoming a complex multimodal bodyminded self, manifesting in action, behaviour, and relationship with the environment.

Exploration 1: Tactile

The first exploration describes a movement activity that aims to draw attention to the body in relation to the environment through the concept of affordances. The sense guiding this activity is tactility or touch, which can be explored between one human mover and objects/textures in the surrounding space, such as a wall or chair, or between two or more human movers. The notion of 'seeing with the whole body' is introduced.

1.Work in pairs. One person begins to move towards sensation, finding stretch and opening in the body: Your eyes are open. The other person uses the touch of the hands to trace their partner's movement: Your eyes are closed. Both partners: resist the desire to lead or to be led. Stay in this tactile connection for a while. Explore through space. Find a pause. Switch roles.

2.Repeat the first exploration. This time, mover, close your eyes. The person using hands-on touch: keep your eyes open. Explore through space. Resist the desire to lead or to be led. Come to a pause and switch roles. Compare these different states of experience.

3.Transpose the task to the environment. Move with a wall, chair, or other object in your immediate environment. Explore affordances through touch. Begin by attending to your own sensations. Bridge to the outer and begin to shape with the environment. Move in order to shape and be shaped.

Exploration 2: Visual disorientation

This activity explores camera-looking with the eyes. Embodiment is foregrounded as 'first affordance' (Spatz 2020) as the whole body in motion is implicated in notions of looking and seeing. The distinction between seeing and moving becomes blurry, setting the stage for a distributed agency in the telling of an emergent story. The choreography/composition does not follow a predetermined logic, but asks: How can I see differently? How can I know differently?

1.Work in pairs. Make a documentary of your partner with your eyes. Both partners perform the task at the same time.

2.Move in order to see, move in order to see differently and unusually. Change perspective, distance, and aperture. Zoom in, zoom out, change your angle. Let your camera pan across. Create jump cuts. Vary your speed.

3.Superimpose objects and images.

4.Move in and out of focus.

Exploration 3: Vocalising and sounding

This next exploration engages with the affordances of the sounding body in motion. Vocalisation and languaging manifest the subliminal shaped by procedural, episodic, and semantic memories that inform the self. Vocalisation and languaging voices the self in relation to the environment.

1.Close your eyes, take a moment to recall how you used your breath during your engagement with your partner. As you relive that experience, did the rhythm of your breath change? Is it changing now? Did you perhaps breathe higher or lower in your body, was your breath audible at times? Are you experiencing these changes now? Within our complex, multimodal bodyminded selves, breath is providing life, breath is also directly related to how we are affected, to our emotions, our feelings. Breath also stimulates our capacity to think.

2.We are now shifting to languaging, honouring the developmental trajectory from vocalisations to language acquisition. You are invited to use your heart language, first language, or mother tongue.

3.Write down the first noun that you are thinking of. The first colour that you are thinking of. The first adjective that you are thinking of. These three words will be unique to each one of us as our choices are elicited from our life-worlds, our subjective selves.

4.What are the vowels/consonants (the phonemes) present in your three words? Explore vocalising them separately. Some of them will enhance feeling, intent. Allow your vocalisations and the concomitant affect to inform your movement.

5.Vocalising these vowels and consonants may provide melody or rhythm. What do these melodies and/or rhythms afford you? Are they changing your relationship with your partner and with the environment?

6.What sounds emerge from your current relationship with your partner and the environment? How are these sounds, the melodies and rhythms of your vocalisations shaping your bodyminded self in relation to your partner and with, through, and in the environment?

Exploration 4: Device as prosthesis

Seeing and hearing are subjective, multi-sensory, three-dimensional, and relational. Following Loussouarn's (2021:79) practice of seeing with the whole body, this exploration makes use of a cellphone camera as an extension of the body i.e., a prosthesis for seeing, without any assumption of how it should be held and a sense of seeing what the camera is filming without looking at the screen.

1.Recall the patterns from both the first and second explorations with your moving partner or wall or other object or surface, and sound. Language may begin to emerge.

2.Use a cellphone camera or cellphone camera and selfie stick, and allow it to become an extension of your body.

3.Start to move and engage in a moving/shifting relationship with the device. As you are engaging in this relationship with the device, you might become aware that you are simultaneously recording and witnessing yourself move.

4.Spend some time with this exploration shifting between an awareness of the device and moving despite the device.

5.Stop the recording, return to other players in the (zoom) room, and take a moment to witness your emerging score and the scores of others through the (zoom) screen.

Conclusion

The explorations described above offer what we refer to as a relatively stable moment in our joint collaborative practices and perhaps even approximate how the creative process might unfold were we to begin a new cycle at this very moment of writing. In the online facilitation of some of these explorations, we found that the mover and camera-person fall together, as the witness becomes the zoom screen with many movers witnessing and being witnessed through the screen simultaneously. This shifts in an in-person context, where the mover and camera/ camera operator begin to engage each other as partners with a third participant, the environment with all its affordances. What these explorations share, however, is the unfolding of a co-creational relationship as perception invites agency to become distributed among all players, both animate and inanimate.

Following the hard lockdowns of the Covid-19 pandemic, we, as co-creators and research partners, are increasingly aware of how the rectangle of screens affords us new ways of seeing, framing, and perceiving not just others, but ourselves. As time and space are reconfigured on a screen through the relational play between mover and camera/camera-person, witnessing emerges as a key principle guiding the practice. The acts of moving, sounding, seeing and looking, hearing and listening distribute agency among the mover(s) and the prosthetic device, here a camera, who become witnesses in the art-making process. Following the notion of the ever-cycling and reversible RSVP process, witnessing also continues into the editing phase, which may lead to reflection (Valuaction) or invite a new moment of resource gathering or scoring.

Our embodied research, which unfolded across the different project iterations, enacts in Spatz's (2020:7) terms, both a movement of 'opening up' and a movement of 'closure', as each instance of revisiting, researching, and reiterating leads to new insights. Previous experiences inevitably informed each iteration, and as such, our research continues to transform, articulating an RSVP Cycle of its own.

This article describes an embodied approach to screendance-making that invites practitioners into a cyclical and reversible embodied research process and creative practice. At the same time, we acknowledge that we, too, as practitioners and researchers, are undergoing a continual revisiting, researching, and reiteration of our collaborative practices. Drawing from Manning (2007:131), we have suggested that sensing opens a pathway towards knowing differently. By drawing attention to how screendance-making, offers a sensory and perceptual practice that exercises agentic possibilities among its players, we recognise the transformational and decolonial potential of artistic exploration.

Notes

1 . All three of us teach (either part-time or full-time) at the Drama Department of the School of the Arts at the University of Pretoria.The activities and explorations described in this article relate primarily to the shifts we made within this teaching space through a process of reflecting and conversing as a team of embodied researchers, educators and co-creators who are continuously grappling with our pedagogies.

2 . We are using the pronoun "we" throughout this article for specific reasons. Firstly, we work as a collective. Secondly, and in line with a decolonial ethos of inclusivity, sharing, acknowledgement of different contributions to a shared project and the dissolution of hierarchy, we claim that collective. Finally, by foregrounding the "we" (as a first-person plural pronoun), we compel ourselves to claim agency and responsibility in the research and creative process.

3 . Art, Access, and Agency - Art Sites of Enabling was an online conference-event presented from 7 to 9 October 2021 by the School of the Arts, Faculty of Humanities, University of Pretoria in collaboration with the Transformation Directorate, University of Pretoria, South Africa. The theme of the conference was to question "how the practices and forms associated with contemporary art and its institutions [might] enable and produce alternate, shared and even wholly new forms of agency, access and participation" (e-flux Education 2021).

4 . Le Grange (2016; 2021) adopts Pinar's (1975) concept of currere to describe an autobiographical method for curriculum decolonisation.

5 . From our perception, this choice manifests due to the monist bodyminded self navigating their (sense of their) peripersonal space for functional, expressive, and aesthetic reasons.

6 . As an urban pioneer, Halprin's formulated "The RSVP Cycles" to stimulate a participatory environmental experience. However, his success depended on collaboration, and particularly the artistic symbiosis and co-construction that existed between him and his wife, the postmodern dancer and choreographer Anna Halprin (Hirsch, 2011:127).

7 . We deliberately avoid referring to an "editing suite" since we often find students sitting on the grass, on a staircase or on the stoep (Afrikaans for 'porch' and used colloquially), whilst editing on their phones or with their laptop devices on their laps.

8 . Working in the field of quantum physics and the use of measuring apparatuses, Barad (2012:646) shows how, through intra-actions, 'meaning and matter do not preexist, but rather are co-constituted via measurement intra-actions'.

9 . We prefer the term 'bodyvoice' as voice is in, through and of the body, intimately shaped by the body.

10 . For the fourth iteration, we were also joined by another co-facilitator, creator and colleague, Calvin Ratladi, whose practice is grounded in the fields of theatre-making and writing, to further enrich the practice following reflections on the third iteration.

11 . Phenomenotechnique is a concept borrowed from Hans-Jörg Rheinberger (2005).

References

Aggiss, L. 2008. Take 7 Study Pack. Brighton: South East Dance. [ Links ]

Aldridge, M. 2013. Bringing screendance to South Africa. Screen Africa Magazine 25:17. [ Links ]

Barad, K. 2003. Posthumanist performativity: toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28(3):801 -831. [ Links ]

Barad, K. 2011. Nature's queer performativity. Qui Parle: Critical Humanities and Social Sciences 19(2):121-158. [ Links ]

Barad, K. 2012. What is the measure of nothingness? Infinity, virtuality, justice. dOCUMENTA (13) Catalog 1/3: The Book of Books. Ostfildern: Hatjie Catz Verlag:646-649. [ Links ]

Berger, J. 1972. Ways of seeing. London: British Broadcasting Corporation & Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Blakeslee, S & Blakeslee, M. 2008. The body has a mind of its own: how body maps in your brain help you do (almost) everything better. New York, NY: Random House. [ Links ]

Boulègue, F & Hayes, MC (eds). 2015. Art in motion: current research in screendance. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. [ Links ]

Csordas, TJ. 1990. Embodiment as a paradigm for anthropology. Ethos 18(1):5-47. [ Links ]

e-flux Education. 2021. Conference: Art, Access, and Agency - Art Sites of Enabling. Available: https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/421662/conference-art-access-and-agency-art-sites-of-enabling/ Accessed 26 June 2023. [ Links ]

Gibson, JJ. 1979. An ecological approach to visual perception. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

Grosfoguel, R. 2011. Decolonizing post-colonial studies and paradigms of political- economy: transmodernity, decolonial thinking, and global coloniality. TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World. 1(1). [ Links ]

Ekdahl, D. 2021. Our body does not have to end where digital screens begin. Academia Letters. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL1487 [ Links ]

Hagan, C. 2022. Screendance from film to festival: celebration and curatorial Practice. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. [ Links ]

Halprin, L. 1969. The RSVP Cycles: creative processes in the human environment. New York, NY: George Braziller. [ Links ]

Hirsch, AB. 2011. Scoring the participatory city: Lawrence (& Anna) Halprin's Take Part Process. Journal of Architectural Education 64(2):127-140. [ Links ]

Hockings, P. 1995. Principles of visual anthropology. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. [ Links ]

Kappenberg, C. 2015. The politics of discourse in hybrid art forms, in Art in motion: current research in screendance, edited by F Boulègue and MC Hayes. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars:21-29. [ Links ]

Le Grange, L. 2016. Decolonising the university curriculum. South African Journal of Higher Education 30(2):1-12. [ Links ]

Le Grange, L. 2021. (Individual) responsibility in decolonising the university curriculum. South African Journal of Higher Education 35(1):4-20. [ Links ]

Logan, K. 2021. Considering the power of the camera in a post-pandemic era of screendance. The International Journal of Screendance 12. https://doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v12i0.8303 [ Links ]

Loussouarn, C. 2021. Moving with the screen on Zoom: reconnecting with bodily and environmental awareness. The International Journal of Screendance 12. https://doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v12i0.7827 [ Links ]

Manning, E. 2007. Politics of touch: sense, movement, sovereignty. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Manning, E. 2016. The minor gesture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. 2017. Critique of black reason. Translated by L. Dubois. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

McPherson, K. 2006. Making video dance. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mitoma, J (ed). 2002. Envisioning dance on film and video. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Otake, E. 2002. A dancer behind the lens, in Envisioning dance on film and video, edited by J Mitoma. New York, NY: Routledge:82-88. [ Links ]

Pendlebury, K. 2014. Cutting across the century: an investigation of the close-up and the long-shot in "cine-choreography" since the invention of the camera. The International Journal of Screendance 4(4):13-28. [ Links ]

Rheinberger, HJ. 2005. Gaston Bachelard and the notion of "phenomenotechnique". Perspectives on Science 13(3):313-328. [ Links ]

Rosenberg, D. 2012. Screendance: inscribing the ephemeral image. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Rouch, J. 1995. The camera and man, in Principles of visual anthropology, edited by P. Hockings. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton:79-98. [ Links ]

Santos, B. de S. 2014. Epistemologies of the South: justice against epistemicide. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Spatz, B. 2015. What a body can do: technique as knowledge, practice as research. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Spatz, B. 2020. Blue sky body: thresholds for embodied research. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Tikka, H. 2018. Enacting agential cuts: notes of the "Untitled 1-3" (2014). Ruukku Studies in Artistic Research 9. Available: https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/371984/386688. Accessed 23 August 2021. [ Links ]

Williams, CA. 2021. Mapping participation: Lawrence Halprin's RSVP Cycles meets Richard Barrett's fOKT. Contemporary Music Review. 40(4):366-385. [ Links ]