Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a7

ARTICLES

The curation of To Be(Hold) in Revere: An Exhibition of Historical Photographs of People with Intellectual Disability

Rory du Plessis

School of the Arts, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. rory.duplessis@up.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8907-9891)

ABSTRACT

In this article, I discuss my curation of a photographic exhibition of people with intellectual disability (PWID) who were institutionalised at the Grahamstown Lunatic Asylum, from 1890 to 1920. The exhibition titled, To Be(Hold) in Revere, aimed to display affirmative photographs and humanising stories of PWID obtained from the Asylum's casebooks. The Sites of Conscience movement influenced the exhibition's aim. The movement seeks to recover the agency and personhood of those who lived at a site of human suffering in order to establish a collective memory of their voices and experiences. This article details my curatorial approach; it provides a telling of the life stories of seven patients and outlines how I adopted the principles of the Sites of Conscience movement in facilitating exhibition walkabouts with the public. A key facet of the walkabouts was encouraging the public to witness the personhood of the Asylum's PWID, as well as to explore the current issues faced by today's PWID and advocate for their human rights.

Keywords: Sites of Conscience, Institute for Imbecile Children, Grahamstown Lunatic Asylum, Thomas Duncan Greenlees, intellectual disability, photography.

The Institute for Imbecile Children in Grahamstown (Makhanda), South Africa was the first facility in Africa for the care of children with intellectual disability. Dr Thomas Duncan Greenlees founded the Institute in 1895 and was appointed as its visiting medical officer from its inception to 1907. In addition to this appointment, Greenlees held the post of medical superintendent of the Grahamstown Lunatic Asylum from 1890 to 1907, and he was appointed as the surgeon superintendent of the Chronic Sick Hospital from 1890 to 1903. Greenlees authored several publications where he reported on the patients with intellectual disability under his care at the aforementioned facilities (Greenlees 1894, 1897, 1899, 1903, 1905, 1907). In his publications, Greenlees was neither an advocate for their needs nor a crusader for promoting their humanness. Rather, as a zealous eugenic campaigner,1 Greenlees (1907:21) called for their extermination, sterilisation, and incarceration to prevent them from populating the 'world with monstrosities that ultimately become a burden on the State'. Moreover, Greenlees (1907) propagated a dehumanised account of people with intellectual disability (PWID) by presenting them to live an unfulfilled and hopeless existence fraught with incessant suffering and day-to-day struggles. For Dorothy Atkinson (2005:11), in such cases where PWID are dehumanised and framed as 'forgotten people, leading forgotten lives', it becomes a 'social and historical imperative' for scholars to research their life stories to reclaim their names, identities, and personhood. I heeded Atkinson's call by exploring the casebooks of the Asylum and the Institute (Du Plessis 2020b, 2021, 2023a, 2023b, 2024). Although the casebooks primarily contain a clinical narrative for each patient where their bodily and mental illnesses were monitored, they also contain vignettes of a patient's life story. In my exploration of the casebooks, I strung together these vignettes to foreground the personhood of PWID.

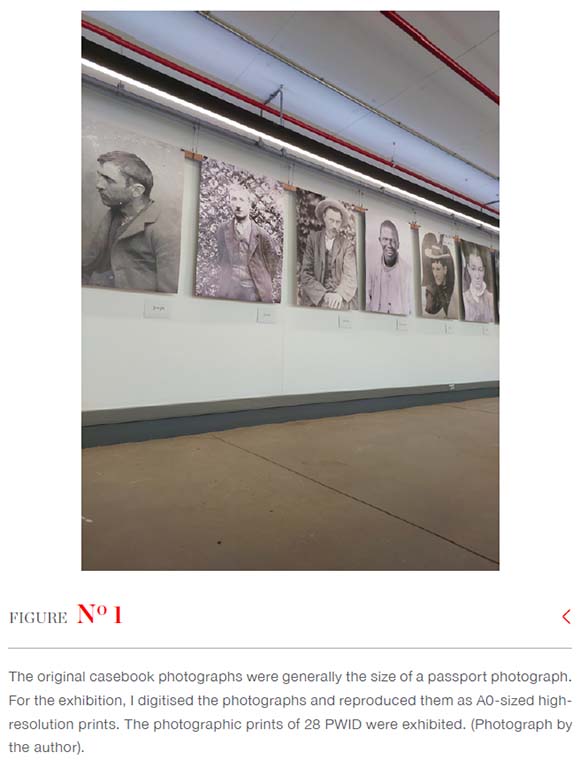

The publication of my research meant that my work was shared with academic audiences, but I also desired for it to be accessible to public audiences and for them to engage with me on the topic. I was spurred to consider a public audience by reading the work of Rob Ellis and Catharine Coleborne (2022:133), who outlined the social responsibility of academics to enter into dialogue about the complex histories of mental health to diverse audiences. I decided that a suitable public engagement for this research was to curate the country's first exhibition of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century photographs of PWID who were institutionalised at the Asylum. I titled the exhibition, To Be(Hold) in Revere, and it was held in October 2022 at the Link Gallery, University of Pretoria. The exhibition aimed to display affirmative photographs and stories of PWID obtained from the Asylum's casebooks (Figure 1).2 The Sites of Conscience movement influenced the exhibition's aim.3 In general, the movement calls for the 'reclamation of sites of human suffering to forge common ground for dignity, respect and civil participation' (Steele, Djuric, Hibberd & Yeh 2020:525).4 To do so, the movement recovers the agency and personhood of those who lived at a site (Steele et al 2020:526). Armed with these recovered narratives, the movement engages with the public to establish a collective memory of the voice and experiences of those who lived at the site (Steele et al 2020:527). Drawing inspiration from the movement, the exhibition presented affirmative photos and humanising stories of PWID to 'construct a meaningful memory' for them (Clarke 2006:485). This is crucial as, for over 130 years, Greenlees's dehumanised account of his patients remained the only narrative we had for the Asylum's PWID.

The decision to exhibit the casebook photographs took into consideration a 'careful examination of the ethical concerns that emerge when engaging more deeply with public communities' (Gagen 2021:40). In particular, how do I respect the dignity of the sitters, how do I avoid perpetuating stereotypes, and how do I promote social justice? Moreover, how do I navigate audiences who attend the exhibition out of a morbid curiosity to gawk at PWID, as well as those who seek out salacious stories of abject anguish and travails of torture (Gagen 2021; Nicholas 2014)? These ethical concerns became central to guiding my curatorial approach with regard to selecting the images and stories from the casebooks, as well as led to my adoption of the principles of the Sites of Conscience movement to provide a 'safe and responsible staging' (Gagen 2021:48) for the viewers to engage with the exhibition. In the ensuing discussion, I discuss the details of my curatorial approach and the adoption of the principles of the Sites of Conscience movement.

To avoid perpetuating stereotypes in the exhibition necessitated that I become literate in the visual tropes of intellectual disability circulating in medical texts of the first decades of the twentieth century. During this period, eugenic beliefs influenced medical texts that regarded PWID as a 'menace and a burden to society' (Elks 2018:418) and a 'distinct and inferior class of society' (Jackson 1995:337). In their representation of PWID, eugenicists focused on photographing patients with the 'stigmata of degeneration' - physical abnormalities that supposedly indicated the presence of a mental deficiency (Jackson 1995:327). Examples of the stigmata of degeneration included, amongst others: 'cranial abnormalities, such as small or asymmetrical heads, ... deformities of the ears, eyes, palate, jaws and teeth; and a selection of other minor anatomical irregularities' (Jackson 1995:327). By primarily emphasising the stigmata of degeneration, the eugenicists rendered PWID as 'scientific and dehumanized specimens of the pathologizing gaze' (Watson 2020:70). This rendering is explicitly evident in the first published clinical photograph of a South African PWID that was printed in an article co-authored by Greenlees. The article reported on the 'pathological details' (Greenlees & Purvis 1901:135) of a PWID's clinical examination, and this focus area was supported by several close-up photographs of the patient's hands, feet, spine, and arms to exhibit his physical deformities. In sum, the photographs emphasised the patient's dehumanised status as a clinical case whose significance lay in the display of the stigmata of degeneration.

The above discussion of clinical photographs presenting the 'stigmata of degeneration' has provided us with a 'fairly comprehensive catalogue of images and conventions that we need to avoid' (Elks 1992:185) to cease perpetuating dehumanising stereotypes of PWID. While we may know what images to avoid, we do not have a canon of archived affirmative images of PWID. In this sense, we only have a visual catalogue of stereotypical representations of PWID because images of them living in the community, photos of them with family, and honorific photographic portraits are either absent or missing from the archives.

The Asylum adopted a heterogeneous photographic practice in which various types of photos were taken (Du Plessis 2015). Accordingly, in the casebooks we find clinical photographs for some of the patients and identification photos for most of the patients. In terms of the latter, these images do not display the stigmata of degeneration, and some surprisingly resemble photographic portraits as there are indications that the sitters posed for the camera, as well as suggestions that the photographer may have adopted certain styles from the genre of civilian photography (see also Rawling 2011). Owing to the absence of honorific images of PWID, the casebook photographs that resemble portraits can offer affirmative representations of PWID. However, can these visual representations of PWID be used to affirm their humanity if the very purpose of the casebook photograph instated them as an inmate of the Asylum?

Barbara Brookes (2011:55) argues that while doctors 'may have photographed patients in an attempt to create typologies of mental illness', for today's audience, we should regard them as a resource to 'resurrect individuals in all their particularity'. Stated differently, Brookes (2011:50) maintains that casebook photographs can be released from their clinical context to 'show us the humanity of people who perhaps did not usually get to pose for a camera'. In this sense, casebook photographs are 'compelling' sources as they are likely the only surviving visual record of a person (Brookes 2011:53). In the interpretation of casebook photographs, we are thus implored to appreciate the 'individuality' (Brookes 2011:50) and 'humanity' (Brookes 2011:55) of the sitters rather than "see" a record of a clinical case. For Caroline Bressey (2011), in her study of the City of London Asylum, the casebooks proved to be a valuable resource for containing a visible record of individuals who are underrepresented in archive records, as well as for providing 'biographies ... that ... would otherwise be very difficult, if not impossible, to trace'. To this end, the casebooks contain fragments of an individual's life story that 'have an important role to play in developing our understandings of the lives of others in the long nineteenth century' (Bressey 2011:13). Given the findings presented by Brookes and Bressey, I endeavoured for the exhibition to explore the casebook photographs as a visual representation of the sitter's individuality, and this was complemented by an exploration of the casebook content for stories that shone a light on the biography of the sitter. In pursuing this exploration, I discarded the clinical context and content of the casebooks to discover visual examples and textual fragments that humanise the subjects.

In focusing only on humanising textual fragments contained in the casebooks, I consciously avoided narrating stories of abuse, suffering, and cruelty that enforces the stereotype of patients as mute victims (Ellis & Coleborne 2022:138). Therefore, the stories that were presented in the exhibition were neither 'damage-centered narratives of the harm done' to them (Guenther 2022:1) nor describing PWID as 'victims who suffer' (Veis 2011:81). Rather, the stories were a sensitive and reverent telling of their humanity: they presented the rich and complex lives of the PWID, their acts of agency, and bonds of friendship, and restored their voice to the history of intellectual disability in South Africa. Significantly, these stories of the PWID can serve as an aid in prompting 'ethically responsible viewing' (Gagen 2021:44) in the audience where their interpretation of the photographs is anchored to a reckoning with the agency and humanity of PWID (Nicholas 2014:153). To explicate, if narratives of suffering run the risk of promoting the position of the viewer as a voyeur to 'exploitation and sensationalism' (Veis 2011:80), then narratives of the PWID's agency and their life stories position the viewer as a witness to the personhood of each of the photographed subjects.

The Sites of Conscience movement calls for the display of affirmative photos and stories of the PWID to go hand-in-hand with developing and designing dedicated opportunities for public engagement so that dialogue can be stimulated (Sevcenko & Russell-Ciardi 2008; Sevcenko 2011; Steele et al 2020). This requires convenors to facilitate programmes that are structured to encourage the telling of stories (Sevcenko 2011:33). To this end, I facilitated daily walkabouts of the exhibition whereby I escorted the audience to each of the portraits, introduced them to the sitter by providing them with the sitter's name and age, and thereafter narrated aspects of their life story and experiences. While the Sites of Conscience movement informed the design of the walkabouts, the way in which I approached the portraits was guided by the scholarship of Elizabeth Edwards. Edwards (2009:38) explores the role of photography 'within a specific form of meaning-making, namely, the telling of histories'. In this role, photos become 'bearers of stories' (Edwards 2009:45) of the sitter, and this necessitates for the viewer to not just look upon them in 'silent contemplation' but to listen, as well as interact and engage with the telling of the sitters' stories. The aim thereof is to prevent static and repetitive tellings in favour of allowing 'histories or stories to emerge in socially interactive ways' (Edwards 2009:42). At the exhibition, the viewers' engagement with the stories 'woven around photographs' (Edwards 2009:42) included pleas for more details regarding a sitter's kin and their acts of agency, as well as requests to place an individual's story within a larger narrative of the lives of PWID at the Asylum. In the discussion below, I offer a telling of the life stories of seven patients that is informed by the questions, observations and interactions made by the viewers of the exhibition. Put differently, the telling that I present here is a product of the viewers being interlocutors with the photograph, engaging with the sitter's life story and thus raising questions and comments. Their interactions directed the features and facets of the patients' life stories that I narrate in this publication.

John

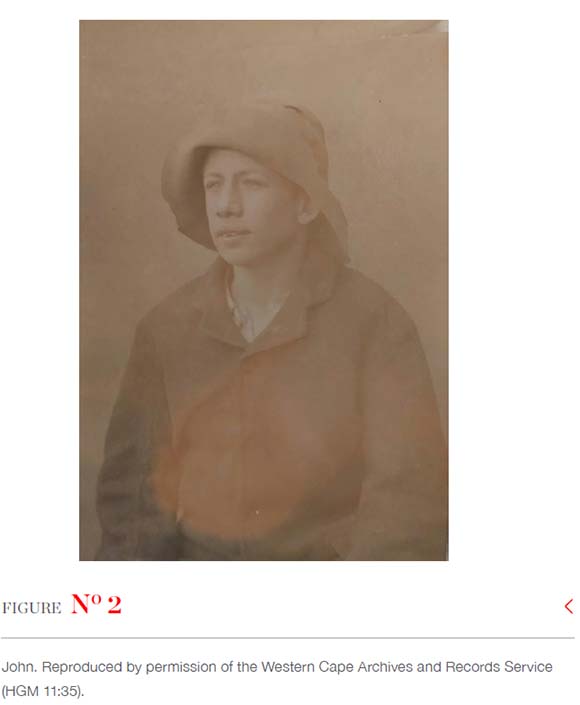

In 1904, at 10 years of age, John was admitted to the Institute for Imbecile Children (HGM 24:62). The Institute aimed to offer education to children with intellectual disability, as well as 'train them to useful occupations' (G27-1895:63). Accordingly, it sought to admit children who were able-bodied. Children who were multiply disabled and those who could not be educated or taught a skill were an undesired patient grouping at the Institute. John was a member of such a patient grouping. He suffered from epileptic seizures and was unable to speak. Greenlees remarked that John's 'intellect [is] a blank' and that he is an 'utterly helpless case'. Greenlees earmarked 'helpless' cases for transfer from the Institute, and when this was not an option, he offered them a limited therapeutic regimen that was 'chiefly confined to keeping them clean, and by careful feeding maintaining their bodily health' (G28-1898:21). On the one hand, this meant that John was precluded from educational treatment - activities directed 'towards the awakening and exercising of those intellectual functions that are underdeveloped or dormant' - and moral treatment consisting of 'efforts towards improving the mental tone ... and developing character' (Greenlees 1907:20). The consequence of offering John a limited therapeutic regimen was that there was very little opportunity for the doctors to observe his capabilities, character, and aptitude. The casebooks thus contain entries whereby the doctors regard John to have 'absolutely no intelligence'. On the other hand, while John was excluded from educational and moral treatment, the staff continued to monitor and maintain his bodily health. The staff thus duly prevented him from wandering away and protected him from sustaining bodily harm and injury. Nevertheless, by early 1910, the staff took less of an active interest in their duties as they resorted to dispensing John with sedatives to keep him from wandering away and being in harm's way.

As the Institute was earmarked to care for children, when John turned 16, he was transferred to the Asylum (HGM 11:35). On admission, the doctor remarked that he suffers from severe epileptic seizures, is unable to speak, and apart from being able to feed himself is 'almost helpless'. Thus, John required 'constant attention' to ensure his health and wellbeing. Such a level of attention by the staff was improbable, as their priority was to attend to patients suffering from curable mental illnesses (Du Plessis 2020a). Despite the staff's limited attention, John thrived at the Asylum, as he was 'well looked after by a patient ... who has taken an interest in him'. The care offered by the fellow patient contributed to John's propitious wellbeing at the Asylum but is also significant for presenting us with a perspective to appreciate John's humanness. To substantiate, while the casebooks are missing details on John's character and identity, the bond of care offered by the fellow patient allows us to appreciate John as a 'valued and loved' human being (Bogdan & Taylor 1989:135). The staff may have regarded John as less deserving of attention and unsuitable for educational and moral treatment, but the fellow patient recognised John's humanness and entered into a relationship with him to care for his wellbeing.

In her reading of the casebook photographs of the Caterham Asylum in Surrey, Stef Eastoe (2020) proposes that the photographs provide a glimpse of the 'care practices and intimacy' offered by an asylum to its patient body. Following this line of argument, John's casebook photograph from his institutionalisation at the Asylum (Figure 2), where he is healthy-looking and well-nourished, can be regarded as a product of his fellow patient's interest in his care, attention, and wellbeing. To behold John's photograph is thus to witness how he was 'brought into or held in personhood' (Nelson 2002:30) by the care he received from a fellow patient.

Not only are the casebooks missing details on John's character and identity, but they are also missing details on his responsiveness to his environment and relations with people. In such instances, by expanding the exploration to the casebook entries for other patients, we can appreciate the responsiveness of patients who were multiply disabled or suffered from severe to profound intellectual disability.5Thus, by the 'layering of voices' (Rawling 2021a:258) from the casebooks of several patients, we gain an awareness of how - even though they received limited attention and care at the Asylum - they were capable of expressing happiness, and how they were responsive to 'their environment and to other people' (Kittay 2005a:126).

For the patients who were severely to profoundly intellectually disabled, meal service was a key source of sensory stimulation. By way of example, Johan was 'unable to articulate' and was derided to be 'absolutely without intelligence' (HGM 9:133), but when he saw food, his eyes would 'glisten with delight'. Johan may have been unable to articulate via speech and language, but he was able to communicate the pleasure he derived from food. Indeed, the act of Johan's eyes glistening is significant, for it establishes his personhood:

In one who can scarcely move a muscle, a glint in the eye at a strain of familiar music establishes personhood. A slight upturn of the lip in a profoundly and multiply disabled individual when a favorite caregiver comes along, or a look of joy in response to the scent of a perfume- all these establish personhood. We know that there is a person before us when we see ... that there is "someone home"; that the seemingly vacuous look is not vacant at all; that an individual's inability to articulate a "language" as publicly defined does not indicate a lack of anything to say. To fail to recognize that capacity is to deny an individual's personhood (Kittay 2001:568).

The casebooks contain evidence on how severely to profoundly intellectually disabled patients were responsive to other people, as well as can be described to reciprocate in their relationships with others. One case in point is Patrick. Upon admission to the Asylum in February 1910, Patrick was belittled for showing no sign 'that he is able to comprehend anything that goes on around him' (HGM 11:21). Five months later, he began to 'smile when spoken to'. Johannes was slated for making 'no intellectual improvement', but this is juxtaposed with entries that note how, over the years, he began to smile and 'laughs when spoken to', as well as how he was 'anxious to give as little trouble as possible' (HGM 9:137). In the smiles of Patrick and Johannes, we thus witness them to be sensitive and responsive to others. Diederick smiled when spoken to but was also acknowledged to express contentment when sitting on the porch (HGM 12:106). In this way, we are implored to recognise how Diederick, despite his severe and multiple disabilities, was 'capable of having a very good life' (Kittay 2005b:110) - a life in which he reciprocated in smiles when he was communicated with, and expressed contentment and happiness to sit on the Asylum's porch, where he may have savoured the afternoon sun on winter days and delighted in watching swallows performing pirouettes in the sky.

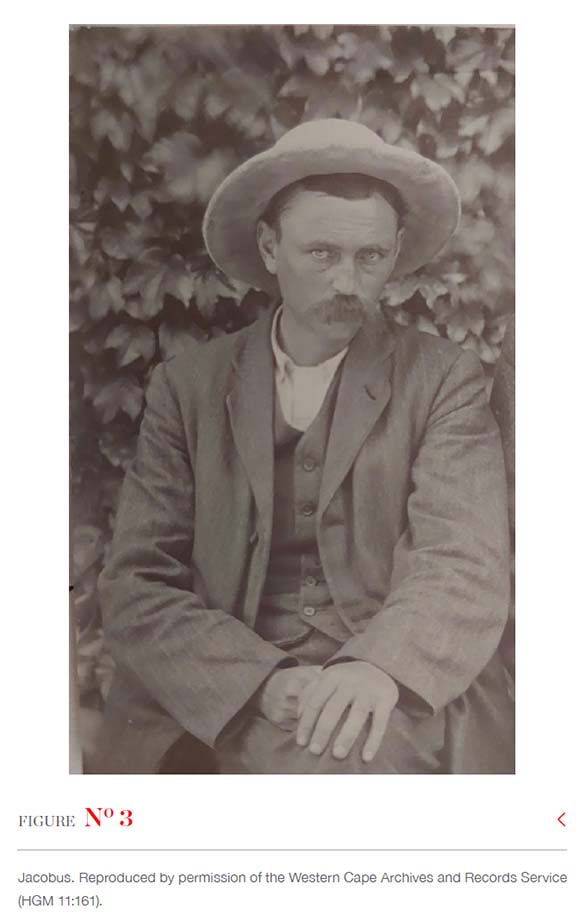

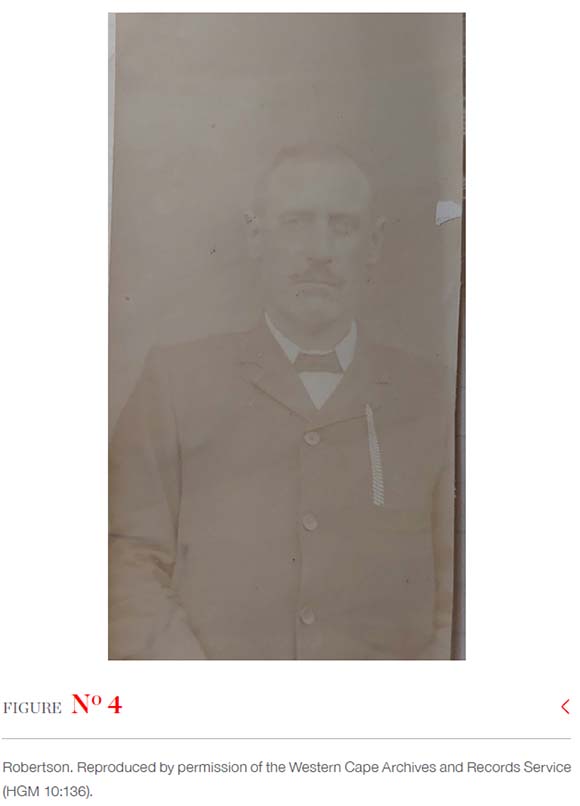

Jacobus and Robertson

The life stories of Jacobus (Figure 3) and Robertson (Figure 4) share several narrative tropes. Both men were admitted to the Asylum in their late thirties, and this was their first time to be institutionalised. This fact points to the men having been under the care of their relatives for a considerable portion of their lives. The lengthy provision of home-based-care for the men is of significance as it allows us to refute Greenlees's (1907:21) declaration that PWID were framed by their families as a burden and were despised by them as a nuisance or a source of vexation within the folds of the family. Overwhelmingly, the casebooks are teeming with cases where families were dedicated to the welfare of their kin with intellectual disability and were 'willing to go to great lengths and expense to ensure [their] well-being' (Clarke 2004/5:65). In general, families only resorted to institutional care for members with intellectual disability once there were adverse changes to their domestic context (for example, the death of a breadwinner), or caregivers becoming too old, weak and infirm to provide care. For Jacobus and Robertson, it was a spate of temper outbursts and fits of violence that led their families to commit them to the Asylum.

Although the institutionalisation of Jacobus and Robertson was initiated and necessitated owing to their outbursts of temper and violence, this behaviour must be comprehended as an isolated moment in their lives and not indicative of their character or temperament. To explore glimpses of their personality and daily conduct an investigation of the casebooks proves to be immensely valuable. On admission to the Asylum, both men were calm and collected. During his medical examination in February 1913, Jacobus (HGM 11:161) confirmed to the doctor that 'he is better', and the doctor remarked that he appeared to be quite 'contented'. Several days after Robertson's (HGM 10:136) admission in July 1909, the doctor remarked that he had not witnessed any fits of rage. Throughout their institutionalisation, they were described as being irritable from time to time, but for the most part, they were upstanding individuals. Jacobus was praised for having 'better manners than a good many people of more intelligence', and complimented for being 'clean and tidy'. Moreover, the doctors often remarked how they observed him expressing contentment from his gardening and interpersonal interactions with staff and patients. Robertson would greet the doctors with a military salute and was 'always particular as to his personal cleanliness and neatness'. Significantly, Robertson's scrupulous efforts to maintain his impeccable dress and gentlemanly appearance were also directed at monitoring the service delivery he received from the Asylum: he would often complain if the food was not up to his standards of serving, presentation, and taste.

When interpreting patient photography, Katherine Rawling (2021b:258) encourages us to consider how a photograph is 'not merely taken of the patient but co-created by them'. In this sense, asylum photography should be regarded as a 'two-way process, a type of dialogue, in which both the photographer and subject play a part' (Rawling 2021b:283). In this dialogue, the photographer certainly instructed the sitter and may have dictated the composition, but the sitter was an active role-player who may have presented themselves before the camera in a way to 'retain or remodel their sense of self' (Rawling 2021b:283). Nevertheless, interpreting a patient's agency and autonomy in a photograph is 'far from straightforward ... since it is difficult to reconstruct the levels and types of coercion involved' (Jordanova 2013:1). In this regard, to forward a meticulous interpretation of asylum photography necessitates turning to 'as much ancillary material as possible, such as case notes' (Jordanova 2013:1). To this end, aided with the stories from the casebooks, we are provided with an expansive context for the interpretation of photographs (Jordanova 2013; Rawling 2021a, 2021b). By scrutinising the casebooks for Jacobus and Robertson, we can appreciate that their well-groomed appearance was not a 'crafted fiction' whereby the men posed before the camera to 'project a normative, indeed an extraordinary, self' (Sidlauskas 2013:36). Rather, their posing for the camera's lens was synonymous with their gentlemanly conduct and civil behaviour at the Asylum. Hence, Robertson's stately appearance - his dignified posture with hands held together, his formal dress with bowtie and what appears to be the chain of a pocket watch, as well as his stern but mannerly facial expression - was matched by his dapper appearance on the wards of the Asylum and in his courteous salutes and salutations to the staff.

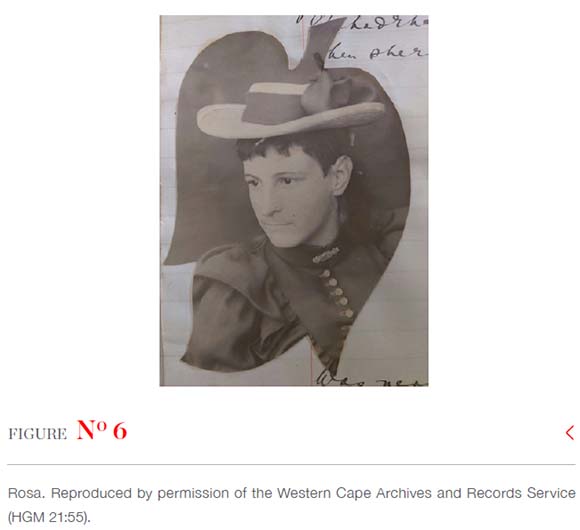

Emily and Rosa

The casebooks for Emily (Figure 5) and Rosa (Figure 6) are significant for exploring how patients sought to gain some form of 'influence over the nature' of their own lives while institutionalised (Clarke 2006:475). Emily (HGM 21:55) would often complain to the doctors of suffering from various pains, including headaches and earaches, and would regularly suffer from epileptic seizures. The doctors soon came to recognise that she was labouring under 'imaginary ills and ails' and established that a number of her epileptic seizures were feigned. Nevertheless, through her acts, Emily achieved a bearing of influence in her daily life at the Asylum by courting and receiving the attention of the doctors. The doctors would often have to humour her complaints, submit her to fictitious medical examinations, and dispense her with placebo medication in the form of saccharine that offered her an immediate "cure".

In detailing the grounds for her committal to the Asylum, Rosa's (HGM 17:97) medical certificates focused excessively on her unkempt appearance, untidy hair, and puerile mannerisms. After only several days at the Asylum, Rosa presented a change in conduct by being on her 'best behaviour' and being 'good natured'. She was rewarded for her upright behaviour by being permitted to leave the Asylum for a week to visit her parents. Shortly thereafter, Greenlees declared that as she was now 'more womanly and can exercise better control over herself', she was to be discharged to the care of her parents. It is possible to suggest that Rosa may have adopted 'womanly' behaviour and a feminine appearance as a surreptitious strategy to receive a discharge from the Asylum. To support this claim, I draw upon Elaine Showalter (1985:84), who reasons that in an asylum in which women's 'sanity was often judged according to their compliance with middle-class standards of fashion', patients 'who wished to impress the staff with their improvement could do so by conforming to the notion of appropriate feminine grooming'. Therefore, it is reasonable to conceive that Rosa consciously performed 'womanly' behaviour to receive privileges at the Asylum, and bring about her discharge. In her casebook photograph, if we concede that Rosa may have crafted her own self-representation by presenting herself as a refined lady, we must also concede that the photographer endorsed Rosa's self-representation by choosing to photograph it (Rawling 2021b:268). Moreover, we should also infer that the Asylum staff ratified her self-representation by cropping the photograph into a leaf shape. To substantiate, the Asylum used pattern-cutting for casebook photographs as an aesthetic device to frame the sitters as 'genteel and feminine' (Du Plessis 2015:92).

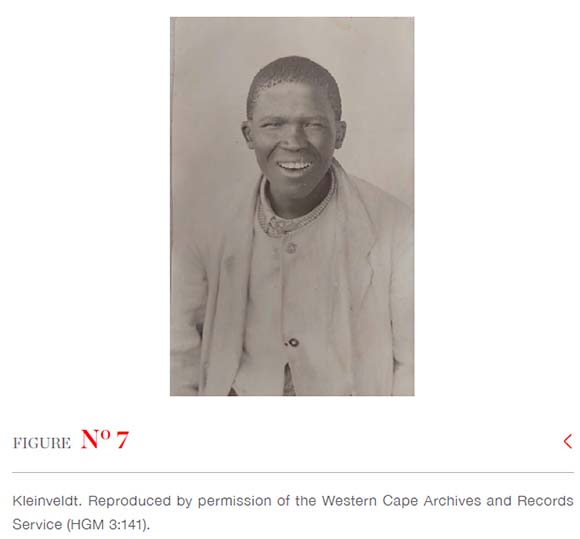

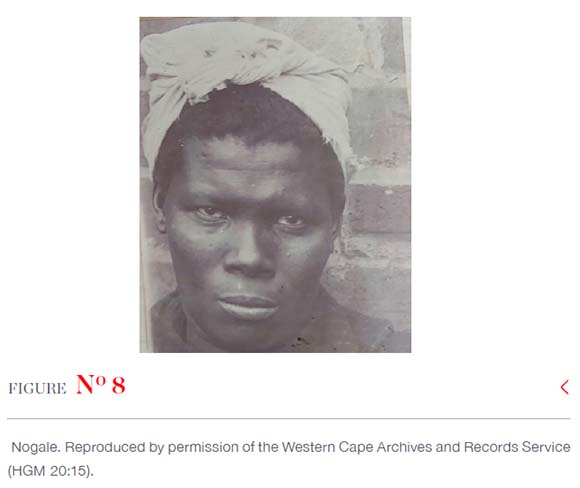

Kleinveldt and Nogale

The Asylum racially segregated its patient population and provided each race grouping with a distinctive therapeutic regimen (Du Plessis 2020a). The doctors prioritised the health, wellbeing, and recovery of white patients. Owing to the preferential care and therapy that the white patients received, their casebooks contain regular entries penned by the doctors who reported on changes to a patient's mental health. The doctors also remarked on observing patients in diverse settings (at entertainment evenings, the dining hall, at excursions), as well as gave an account of the interviews they conducted with them. In sum, the casebooks for white patients contain considerable information that lends itself to narrating aspects of a patient's character, experiences, and life story. The black patients received a limited therapeutic regimen, and the focus of the casebook entries was reporting on their ability to be an industrious and unpaid workforce at the Asylum. Nevertheless, the casebooks contain a few details that present us with a partial glimpse of the personhood of black patients.

Kleinveldt (HGM 3:141) was admitted to the Asylum in June 1894. In his first few months at the Asylum, Kleinveldt struggled to speak coherently, but by February 1895, he was much-admired for talking 'rationally in Dutch', and for starting to learn to speak English. Several weeks later, he was regarded as 'fit for discharge', and Greenlees concluded that he is 'cheerful, works well and intelligent in conversation'. Kleinveldt was discharged at the end of April and returned to his father's town. It is plausible to suggest that Greenlees's decision to discharge Kleinveldt was motivated by him being healthy and able-bodied, capable of work, coherent and comprehensible in speech, as well as having a family member who could care for his wellbeing.

Nogale (HGM 20:15) suffered from severe epileptic seizures. Her body bore numerous scars from burns sustained during severe seizures where she would fall into fires or drop boiling water over her body. At the Asylum, Nogale was described to be 'quiet and well behaved as a rule', as well as 'cheerful and industrious', but when she was suffering from an epileptic seizure, she would become violent. Nogale's severe epilepsy and the absence of a family member to provide her with home-based care were factors that precluded her from discharge, and thus, she was transferred to the Fort Beaufort Asylum in October 1904.

The casebooks for Kleinveldt and Nogale contain only sparse entries for the telling of their personhood, but the way in which they posed for their photographs may point to 'some form of subjectivity' (Rawling 2021a:251) on their part to assert their sense of self (Rawling 2017). Unlike the standard blank stare that most casebook photographs present, Kleinveldt (Figure 7) smiles broadly in his photograph. He was not directed to smile, but he smiled at his own choosing. His decision to smile may have been motivated by him choosing to present his cheerful character to the Asylum's staff and affirm his self-identity. Nogale (Figure 8) is depicted wearing the Asylum's standard-issue dress for non-paying patients. While the dress marks her as a patient of the Asylum, by wearing a kopdoek (headscarf), she demonstrates her agency by personalising her presentation before the camera (Hamlet & Hoskins 2013).6 Stated differently, by wearing a kopdoek, Nogale is transformed from a 'passive object' with the label of a patient to an 'active subject' (Rawling 2021b:269). Her act of self-fashioning thus allows us to appreciate her individuality rather than looking upon her as a depersonalised clinical case or as an anonymised member of the patient body.

In presenting the exhibition's walkabouts, once I concluded the storytelling of the photographed sitters, I facilitated a discussion on how the stories of the PWID who lived in the past can prompt us to explore the current issues faced by today's PWID. In offering such a discussion, I was guided by the principles of Sites of Conscience that seek to invite visitors to understand how the stories of the past offer 'a wealth of lessons' (Sevcenko 2011:17) to address current social issues and challenges (Punzi 2022). To this end, Sites of Conscience promote visitors to 'not remember the past simply to understand how things were, but instead use memory to make connections between the past and social justice and human rights issues in the present, to inform how things can and should be now and into the future' (emphasis in original) (Steele et al 2020:526).

A central point in the facilitated discussions was the Gauteng Mental Marathon Project (GMMP), which took place in the province of Gauteng from 2015 to 2016, and entailed transferring 2,000 mental health care users from a long-term care facility to non-governmental organisations (NGOs). The NGOs were ill-equipped and poorly funded and thus provided the patients with a 'sub-standard caring environment' (Makgoba 2017:1). The conditions at the NGOs were described as 'treacherous' (Moseneke 2018:31), and they operated like 'concentration camps' (Makgoba 2017:6) where the patients were starved, dehydrated and abused. Ultimately, the NGOs were 'sites of death and torture' (Moseneke 2018:24) in which 144 patients died, and a further 1,418 patients were 'exposed to trauma and morbidity' (Moseneke 2018:2). For Charlotte Capri and her co-authors (2018:153) the GMMP must be regarded as the country's 'high-water mark of an ongoing silent catastrophe' in which PWID - as our society's 'single most disenfranchised and oppressed groups' - suffer violations on a 'daily basis in pervasive ways'.

The exhibition's viewers drew upon the stories of the patients of the Asylum to help them engage with current issues pertaining to the low standards of care offered to PWID. The viewers were shocked by the perpetuation of the dehumanisation of PWID that has endured from Greenlees's writings in the early 1890s to the GMMP of 2015-2016. The persistence of harm, abuses, and injustices inflicted upon PWID was appalling for the viewers, but they were equally dismayed that society has not yet moved sufficiently forward to promote their rights to dignity, care, and respect. The discussions inspired some of the viewers to become 'active and engaged citizenry' (Sevcenko 2011:17) who used social media to commemorate the lives of the PWID that were represented in the exhibition,7 as well as to advocate for the human rights of PWID to live 'enriching, meaningful and torture-free lives' (Capri et al 2018:154).

I closed the walkabouts with a plea for the viewers to enter into the company of PWID, to learn from them, encounter them as individuals, and listen to their life stories. Eva Feder Kittay (2019) venerates such an encounter with PWID as presenting an opportunity for 'learning to become a humbler philosopher' and being taught about 'what matters in life'. The reigning paradigm for personhood is 'fixated on intellect, independence, and productivity' (Kittay 2001:560), thereby leading to PWID's exclusion. Kittay (2001:568) proposes a revised and expansive definition of personhood, which focuses primarily on an individual 'having the capacity to be in certain relationships with other persons, to sustain contact with other persons, to shape one's own world and the world of others'. With this definition in mind, to invite the viewers to witness a PWID's personhood is thus to behold the joy they bring about in their relationships with others, as well as how they contribute to the 'creation of good in this world' by their interactions with others (Kittay 2005a:129).

Conclusion

In his publications, Greenlees stripped the PWID of their humanity. In this regard, the exhibition's display of affirmative photographs and stories of the PWID provided a counter-narrative to Greenlees's dehumanised accounts of them. The exhibition thus restored the humanity of the Asylum's PWID and called upon the viewers to become interlocutors with the portraits of the PWID and interact with the telling of their stories. The value of the viewers' engagement lay in the 'goodness of acknowledging' (Nelson 2002:32) the personhood of the PWID. In today's media, the lives of PWID usually come to the public's attention in 'sensational stories that expose appalling forms of abuse' (Kittay 2001:558). In these stories, the PWID are understood to be victims of abuse, as tortured and wounded sufferers, as well as targets for mistreatment, cruelty, and neglect. This is discernible in the abominable GMMP, which was labelled to be a 'harrowing account of the death, torture and disappearance of utterly vulnerable mental health care users' (Moseneke 2018:2). What has escaped the public's attention is seeing PWID 'as subjects, as citizens' (Kittay 2001:558). It is my hope that the exhibition mobilised the viewers to explore possibilities to engage with PWID. This may take the form of a commitment to seek out opportunities to become involved in the advocacy of PWID, to learn about the everyday realities of their lives, and for those who develop relationships with PWID, that they will appreciate their 'irreplaceable and distinctive worth' (Kittay 2005b:113).

Notes

1 . For further discussion of the eugenic discourses that were circulating in South Africa's medical literature, from 1890 to 1920, see Hodes (2015) and Klausen (1997).

2 . The exhibition's aim was underpinned in the title of the exhibition, To Be(Hold) in Revere. The title included a wordplay in 'Be(Hold)' that encourages viewers to consider what it would mean to: (1) BE in awe of another human, (2) HOLD someone in respect and tenderness of feeling, or (3) to BEHOLD a person as hallowed.

3 . For studies investigating the various approaches taken in the collection, curation and display of mental health histories, see: Coleborne (2003); Ellis (2015); Ellis and Coleborne (2022). For an in-depth investigation of Sites of Conscience in the analysis of psychiatric museums, see Punzi (2022). A flagship Site of Conscience for mental health histories is the Pennhurst Memorial and Preservation Alliance. The Alliance focuses on remembrance of persons with disabilities, who were confined to Pennhurst State School and Hospital, Pennsylvania, United States of America (Punzi 2022).

4 . The Sites of Conscience movement gained global momentum in 1999 with the founding of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience. The coalition represents a worldwide 'network of historic sites, museums and memory initiatives that connects past struggles to today's movements for human rights' (Sites of Conscience [sa]).

5 . People with severe intellectual disability 'often have the ability to understand speech but otherwise have limited communication skills' and can 'learn simple daily routines and to engage in simple self-care', while people with profound intellectual disability 'cannot live independently, and they require close supervision and help with self-care activities. They have very limited ability to communicate and often have physical limitations' (Clinical Characteristics of Intellectual Disabilities [sa]).

6 6.Kopdoeks were not part of the Asylum's standard issue-dress for black female patients. The casebook photographs display the wide variety of styles in which the black women tied / fashioned their kopdoeks.

7 . For example, see the following posts on social media: @michelefromearth (2022); @marinastrydom (2022).

References

@marinastrydom. 2022. [Facebook]. 23 October. [O]. Available https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=10159394735033759&id=648453758&mibextid=Nif5oz Accessed 10 February 2023. [ Links ]

@michelefromearth. 2022. [Instagram]. 30 October. [O]. Available: https://www.instagram.com/p/CkWZcHDqK6b/?igshid=MzRlODBiNWFlZA Accessed 10 February 2023. [ Links ]

Atkinson, D. 2005. Narratives and people with learning disabilities, in Learning disability: A life cycle approach to valuing people, edited by G Grant, P Goward, M Richardson & P Ramcharan. Maidenhead: Open University Press:7-27. [ Links ]

Bogdan, R & Taylor, SJ. 1989. Relationships with severely disabled people: The social construction of humanness. Social Problems 36(2):135-148. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1525/sp.1989.36.2.03a00030 [ Links ]

Bressey, C. 2011. The City of Others: Photographs from the City of London Asylum Archive. Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century 19(13):1-15. https://doi.org/10.16995/ntn.625 [ Links ]

Brookes, B. 2011. Pictures of people, pictures of places: Photography and the asylum, in Exhibiting madness in museums: Remembering Psychiatry through collections and display, edited by C Coleborne & D MacKinnon. London: Routledge:30-47. [ Links ]

Capri, C, Watermeyer, B, Mckenzie, J & Coetzee, O. 2018. Intellectual disability in the Esidimeni tragedy: Silent deaths. South African Medical Journal 108(3):153-154. https://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2018.v108i3.13029 [ Links ]

Clarke, N. 2004/2005. Sacred Daemons: Exploring British Columbian Society's Perceptions of 'Mentally Deficient' Children, 1870-1930. BC Studies 144:61-89. https://doi.org/10.14288/bcs.v0i144.1743 [ Links ]

Clarke, N. 2006. Opening closed doors and breaching high walls: Some approaches for studying intellectual disability in Canadian history. Histoire sociale/Social History 39(78):467-485. [ Links ]

Clinical characteristics of intellectual disabilities. [sa]. National Academies Press. [O]. Available https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK332877/ Accessed 12 October 2022. [ Links ]

Coleborne, C. 2003. Remembering psychiatry's past: The psychiatric collection and its display at Porirua Hospital Museum, New Zealand. Journal of Material Culture 8(1):97-118. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591835030080017 [ Links ]

Du Plessis, R. 2015. Beyond a clinical narrative: casebook photographs from the Grahamstown Lunatic Asylum, c. 1890s. Critical Arts 29(sup1):88-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2015.1102258 [ Links ]

Du Plessis, R. 2020a. Pathways of patients at the Grahamstown Lunatic Asylum, 1890 to 1907. Pretoria: Pretoria University Law Press. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, R. 2020b. The life stories and experiences of the children admitted to the Institute for Imbecile Children from 1895 to 1913. African Journal of Disability 9(0). https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v9i0.669 [ Links ]

Du Plessis, R. 2021. The Janus-faced public intellectual: Dr Thomas Duncan Greenlees at the Institute for Imbecile Children, 1895-1907, in Public Intellectuals in South Africa: Critical Voices from the past, edited by C Broodryk. Johannesburg: Wits University Press:200-221. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, R. 2023a. People with intellectual disability at the Grahamstown Lunatic Asylum: humanizing photographs, stories and narratives from the casebooks, 1890 to 1920. Safundi https://doi.org/10.1080/17533171.2023.2227462 [ Links ]

Du Plessis, R. 2023b. The Institute for Imbecile Children: remembering the lives and experiences of the patients, in Memory, anniversaries and mental health in international historical perspective: Faith in reform, edited by R Wynter, J Wallis & R Ellis. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan:183-207. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, R. 2024. Intellectual disability in South Africa: Affirmative stories and photographs from the Grahamstown Lunatic Asylum, 1890-1920, in Sites of conscience and the unfinished project of deinstitutionalization: Place, memory, and social justice, edited by E Punzi & L Steele. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. [ Links ]

Eastoe, S. 2020. Idiocy, imbecility and insanity in Victorian society: Caterham Asylum, 1867-1911. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Edwards, E. 2009. Thinking photography beyond the visual, in Photography: Theoretical snapshots, edited by JJ Long, A Noble & E Welch. London: Routledge:31-48. [ Links ]

Elks, M. 1992. Visual rhetoric: Photographs of the feeble-minded during the eugenics era. PhD dissertation. Syracuse University, United States of America. [ Links ]

Elks, M. 2018. Three illusions in clinical photographs of the feeble-minded during the eugenics era, in The Routledge History of Disability, edited by R Hanes, I Brown & NE Hansen. New York, NY: Routledge:394-420. [ Links ]

Ellis, R. 2015. 'Without decontextualisation': the Stanley Royd Museum and the progressive history of mental health care. History of Psychiatry 26(3):332-347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957154X14562747 [ Links ]

Ellis, R & Coleborne, C. 2022. Co-producing madness: international perspectives on the public histories of mental illness. History Australia 19(1):133-150. https://doi.org/10.1080/14490854.2022.2028558 [ Links ]

Gagen, E. 2021. Facing madness: The ethics of exhibiting sensitive historical photographs. Journal of Historical Geography 71:39-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2020.12.001 [ Links ]

Greenlees, TD & Carrington, GP. 1901. Friedreich's Paralysis. Brain 24(1):135-148. [ Links ]

Greenlees, TD. 1894. A contribution to the statistics of insanity in Cape Colony. The American Journal of Psychiatry 50(4):519-529. [ Links ]

Greenlees, TD. 1897. Remarks on lunacy legislation in the Cape Colony. The Cape Law Journal 14. [ Links ]

Greenlees, TD. 1899. On the threshold: Studies in psychology. A lecture delivered to the Eastern Province Literary and Scientific Society. Grahamstown: Grahamstown Asylum Press. [ Links ]

Greenlees, TD. 1903. Insanity - Past, present, and future. Grahamstown Asylum Press: Grahamstown. [ Links ]

Greenlees, TD. 1905. Statistics of insanity in Grahamstown Asylum. South African Medical Record 3(11):217-224. [ Links ]

Greenlees, TD. 1907. The etiology, symptoms and treatment of idiocy and imbecility. South African Medical Record 5(2):17-21. [ Links ]

Guenther, L. 2022. Memory, imagination, and resistance in Canada's Prison for Women. Space and Culture 25(2):255-265. https://doi.org/10.1177/12063312211066549 [ Links ]

Hamlett, J & Hoskins, L. 2013. Comfort in small things? Clothing, control and agency in County Lunatic Asylums in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century England. Journal of Victorian Culture 18(1):93-114 https://doi.org/10.1080/13555502.2012.744241 [ Links ]

HGM [Hospital Grahamstown Mental]. Grahamstown Lunatic Asylum Casebooks. Western Cape Archives and Records Service. [ Links ]

Hodes, R. 2015. Kink and the colony: Sexual deviance in the medical history of South Africa, c. 1893-1939. Journal of Southern African Studies 41(4):715-733. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2015.1049486 [ Links ]

Jackson, M. 1995. Images of deviance: Visual representations of mental defectives in early twentieth-century medical texts. The British Journal for the History of Science 28(3):319-337. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007087400033185 [ Links ]

Jordanova, L. 2013. Portraits, patients and practitioners. Medical Humanities 39(1):2-3. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2013-010367 [ Links ]

Kittay, EF. 2001. When caring is just and justice is caring: Justice and Mental Retardation. Public Culture 13(3):557-579. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-13-3-557 [ Links ]

Kittay, EF. 2005a. At the margins of moral personhood. Ethics 116(1):100-131. https://doi.org/10.1086/454366 [ Links ]

Kittay, EF. 2005b. Equality, dignity and disability, in Perspectives on equality: The secondSeamus Heaney Lectures, edited by MA Lyons & F Waldron. Dublin: Liffey Press:93-119. [ Links ]

Kittay, EF. 2019. Learning from my daughter: The value and care of disabled minds. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Klausen, S. 1997. 'For the sake of the race': Eugenic discourses of feeblemindedness and motherhood in the South African medical record, 1903-1926. Journal of Southern African Studies 23(1):27-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057079708708521 [ Links ]

Makgoba, MW. 2017. The report into the 'circumstances surrounding the deaths of mentally ill patients: Gauteng Province'. No guns: 94+ silent deaths and still counting. Office of the Health Ombud. Republic of South Africa. [ Links ]

Moseneke, D. 2018. Final Ruling in the Arbitration between: Families of Mental Health Care Users Affected by the Gauteng Mental Marathon Project and the National Minister of Health of the Republic of South Africa, the Government of the Province of Gauteng, the Premier of the Province of Gauteng and the Member of the Executive Council of Health: Province of Gauteng. [ Links ]

Nelson, HL. 2002. What child is this? The Hastings Center Report 32(6):29-38. https://doi.org/10.2307/3528131 [ Links ]

Nicholas, J. 2014. A debt to the dead? Ethics, photography, history, and the study of freakery. Histoire sociale / Social History 47(93):139-155. https://doi.org/10.1353/his.2014.0006 [ Links ]

Punzi, E. 2022. Långbro Hospital, Sweden-from psychiatric institution to digital museum: A critical discourse analysis. Space and Culture 25(2):282-294. https://doi.org/10.1177/12063312211066543 [ Links ]

Rawling, KDB. 2011. Visualising mental illness: Gender, medicine and visual media, c 1850-1910. PhD thesis, Royal Holloway, University of London, United Kingdom. [ Links ]

Rawling, KDB. 2017. 'She sits all day in the attitude depicted in the photo': Photography and the Psychiatric Patient in the late Nineteenth Century. Medical Humanities 43(2):99-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2016-011092 [ Links ]

Rawling, KDB. 2021a. Patient Photographs, Patient Voices: Recovering Patient Experience in the Nineteenth-Century Asylum, in Voices in the History of Madness: Personal and Professional Perspectives on Mental Health and Illness, edited by R Ellis, S Kendal & SJ Taylor. London: Palgrave Macmillan:237-262. [ Links ]

Rawling, KDB. 2021b. 'The annexed photos were taken today': Photographing patients in the late-nineteenth-century asylum. Social History of Medicine 34(1):256-284. https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/hkz060 [ Links ]

Reports on the Government and Public Hospitals and Asylums, and Report on the Inspector of Asylums. Cape of Good Hope Official Publications. Western Cape Archives and Records Service: G27-1895; G28-1898. [ Links ]

Sevcenko, L. 2011. Sites of Conscience: Reimagining reparations. Change Over Time 1(1):6-33. https://doi.org/10.1353/cot.2011.a430735 [ Links ]

Sevcenko, L & Russell-Ciardi, M. 2008. Foreword. The Public Historian 30(1):9-15. https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2008.30.L9 [ Links ]

Showalter, E. 1985. The female malady: madness and English culture, 1830-1980. New York, NY: Pantheon. [ Links ]

Sidlauskas, S. 2013. Inventing the medical portrait: Photography at the 'Benevolent Asylum' of Holloway, c. 1885-1889. Medical Humanities 39(1):29-37. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2012-010280 [ Links ]

Sites of Conscience. [sa]. [O]. Available: https://www.sitesofconscience.org/about-us/about-us-2/ Accessed 19 February 2023. [ Links ]

Steele, L, Djuric, B, Hibberd, L & Yeh, F. 2020. Parramatta Female Factory Precinct as a site of conscience: Using institutional pasts to shape just legal futures. The University of New South Wales Law Journal 43(2):521 -551. [ Links ]

Veis, N. 2011. The ethics of exhibiting psychiatric materials, in Exhibiting madness in museums: Remembering psychiatry through collections and display, edited by C Coleborne & D MacKinnon. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Watson, K. 2020. Precarious memory: Eudora Welty and the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum. Eudora Welty Review 12:69-86. https://doi.org/10.1353/ewr.2020.0008 [ Links ]