Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Image & Text

versión On-line ISSN 2617-3255

versión impresa ISSN 1021-1497

IT no.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a6

ARTICLES

Between damage and possibility: Informal Recycling Conceived as Life Raft

Jacki Mclnnes

University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa jacki.mcinnes@gmail.com (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8176-7136)

ABSTRACT

Contemporary South African society is deeply inequitable, thrusting the consumerist waste of those who have the means into the sphere of those whose most basic needs for survival are not adequately met. Much of this waste is recyclable, however, and is now recognised to have substantial monetary value. The collecting and selling of the discards of the wealthy thus offers a viable source of income for the country's poor. This essay appraises Johannesburg in terms of its complex socio-economic systems and problems, particularly as these pertain to waste and its handlers. Specifically, it examines two conceptually related art interventions involving the City's informal recyclers. The first, House 38: Hazardous Objects, commenced in 2009. Various iterations followed, culminating in the second - Sleeps with the fishes in 2016. In both, the intention was to articulate questions of value - material and, more especially, human.

House 38: Hazardous Objects comprised an installation of hand-beaten lead trash-objects and became a conceptual device to interrogate the following themes: the artwork as actant; labour, skill and materiality; and permanence versus disposability. Sleeps with the fishes re-purposed Theodore Géricault's The Raft of the Medusa (1819) by staging a group of recyclers crammed into a floundering skiff atop one of Johannesburg's infamous mine dumps. Just as Géricault had sought to illustrate the inherent danger of governing bodies putting their interests above those of their citizens, giving power to political favourites, and abandoning the poor, so too did I wish to caution that civil society as a whole cannot expect to escape unscathed when governmental and societal structures turn a blind eye to burgeoning consumption and its fallout - and to the circumstances of the poor who attend to the predicament.

But this essay also proposes that, since a physical shipwreck can be survived, it can therefore also symbolise innovation, endurance, spiritual and ethical resilience, and rebellion against authoritarian structures. And furthermore, just as the recycler's trolleys are likened to sea-going vessels and their drivers to seafarers, so too, the pallet/raft can be suggested as a potent allegory for the self-reliant mariner who must use what little is available to survive in open waters. It will be seen that this essay persistently mediates between the diametrical themes of hardship and of opportunity, thereby articulating and sustaining the titular reference to damage and possibility.

Keywords: Johannesburg, gold, garbage, Discard Theory, mine dump, inequality, recycling, waste pickers, informal economy, consumerism, capitalism, environmentalism, life raft, The Raft of the Medusa, Théodore Géricault, mixed media art.

Introduction

Johannesburg my city

Paved with Judas gold

Deceptions and lies

Dreams come here to dieLesego Rampolokeng (2004)

Middens, comprising the preserved remains of ancient human habitation and its discard, have provided a vital resource for archaeologists wishing to study past societies. Now, as then, the study of human consumption and the management of our waste confirm that garbage provides important material evidence of complex cultural, economic, political and environmental systems. Critical Discard Theory provides a framework within which one can build relevant interdisciplinary bridges linking local and global politics and economics, aiding us to interpret the multifaceted questions that have come to characterise contemporary human existence (Whiteley 2011:12). In this essay, garbage will be assessed in terms of the potent signifier that it is - able to denote abundance amongst the wealthy, while simultaneously indicating its commodity value to the poor. Johannesburg's informal recyclers, by virtue of the unique intersection they represent between humans and their discard, will play a leading role.

Garbage has become ubiquitous. It straddles geopolitical, social and economic settings with impunity and is therefore both a compelling yardstick and powerful leveller. It is a signifier of wealth and the measure of our "conspicuous consumption" as coined by Thorstein Veblen in The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899). In fact, it would not be preposterous to suggest that planned obsolescence has become a contemporaneous key to economic stability. The groaning and toppling rubbish dumps that pockmark our world can be seen as the symbols of the vast resources of the earth - and the labour of its people - wasted away in seemingly no time at all (Stallabras 2009:419).

In keeping with a leitmotif of damage and possibility, I will confine this essay to the potential offered by garbage to speak to matters of worthlessness and value. This will be considered in the literal sense as it pertains to our discard as a commodity; secondly, in terms of the value to society and environment of the work performed by Johannesburg's informal recyclers; and thirdly, with regards to "human value" - or what it might mean to be valued as a present and contributing member of our species.

By linking creative practice and environmental sustainability to Discard Studies, Stuart Walker (2014:17) argues that creative practice 'is capable of tackling complex issues in situations where the question cannot be clearly or narrowly defined, where information is incomplete, and where a variety of outcomes is possible'. Creative research has the potential to bring together a diverse range of factors, integrating them into specific outcomes or design solutions by way of processes and practices that combine intellectual knowledge with human imagination and creativity. Managing human discard in an environmentally sustainable manner, he continues, requires exactly this kind of analysis to unravel the intricacies of social, economic and environmental considerations as they intersect with 'individual purpose and profound notions of personal meaning that go to the heart of what it is to be a human being' (Walker 2014:17).

It should be noted, with regards to the previous paragraph, that the descriptor "environmental sustainability" has become problematic of late. The Oxford English Dictionary defines sustainable as "to be capable of enduring". But, in an era in which economic growth is paramount - and frequently achieved at the expense of environmental and social best-practices - the bandying about of the term environmental sustainability runs the risk of ringing hollow, or worse. The term should therefore be approached with due circumspection (King 2013).

Taking Mary Douglas's pivotal definition of dirt as matter out of place as my departure point, I propose to extrapolate its implications for the human population. Those in society who are considered abject or disposable have come to be regarded as "people out of place", and unfortunately, the notion of disposable people has a long history in South Africa. Georg Lukács (1923:38), whose writing predates Douglas's by many decades, had already observed this phenomenon when he wrote that as the commodification, commercialisation and monetarisation of human livelihoods continued to accelerate, so too would the ontological conflation of the human and of disposable waste:

[The labourer's] specific situation is defined by the fact that his labour-power is his only possession. His fate is typical of society as a whole in that this self-objectification, this transformation of a human function into a commodity reveals in all its starkness the dehumanised and dehumanising function of the commodity relation.

Workers have increasingly been perceived as cogs in the overall process and have become estranged from the skills they bring to the workplace. Furthermore, as rising levels of automation have replaced their specialised skills, so the emphasis has switched from qualitative to quantitative, thereby decreasing their worker-status and usefulness. "Commodity" has come to be understood not only as the labourer's product, but as labour itself - and, by extension, the labourers themselves (Lukács 1923:34). So even as capitalism has generated surplus labour, so, simultaneously, has it discarded the labourer.

Achille Mbembe (2011:8) notes that although we generally define waste as that which is produced 'bodily or socially by humans', we must simultaneously acknowledge that 'workers are wasted under capitalism' in a manner akin to the exploitation of natural resources. Therefore, since the advent of democracy in South Africa in 1994, there has been an earnest quest to 're-humanise society and culture' - a task that has not been easy in view of the unique course race and capitalism has followed in this country (Mbembe 2011:8). It is particularly ironical that this logic of human waste is exacerbated in an environment characterised by an alarming scarcity of wage-labour. '[A] rising superfluous population is becoming a permanent fixture of the South African social landscape with little possibility of ever being exploited by capital' (Mbembe 2011:8). These conditions aptly describe the lived experience of Johannesburg's recyclers and Mbembe's writing therefore provides important context for interrogating the value judgements habitually applied to them.

By way of introducing my themes, I will begin by revisiting a body of work initiated in 2009 entitled House 38: Hazardous Objects. Artworks from this series, which spanned several years and manifested in various incarnations, offer a springboard from which to survey several questions: How is the ever-increasing burden of trash to be managed in the city of Johannesburg? By whom? Driven by what motives? And for whose gain? Key to my creative work has been a conscious attempt to force a confrontation with the concept of trash - but more importantly - with those who handle it. This in an effort to initiate a more meaningful contemplation of the things and people that we tend to disregard as that which we instinctively do not wish to acknowledge.

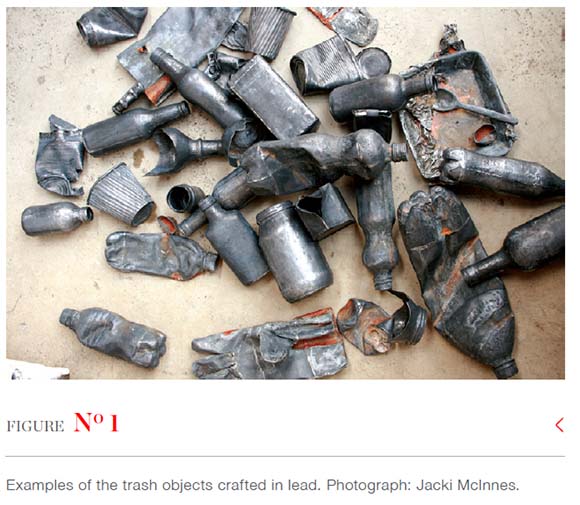

Working collaboratively with the late photographer John Hodgkiss in 2009, I began engaging with a community of informal recyclers living in an abandoned building at 38 Sivewright Street in Johannesburg's inner-city precinct of Doornfontein. Our House 38 project (2009-2010) sought to probe the experiences and rationales of the community by off-setting Hodgkiss's anecdotal photographs against my own hand-crafted miscellany of trash-objects comprising aluminium cans, polystyrene punnets and plastic soft-drink bottles (Figure 1). I duplicated these items - routinely collected by the recyclers - in near-virtual detail by beating sheet-lead directly onto the trash-objects themselves (or onto the solid plaster casts of those that were too fragile).

Jane Bennett's Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things concerns itself with the "thingness of things"- their shape, colour, texture, possible use and form - and how these attributes can cause an inanimate object to influence humans; to have "affect". Bennett's concept of vital materialism offers an alternative assessment of the inanimate, suggesting that the undeniable power of objects lies in their ability to enhance our understanding of the human subject by inviting us to ponder our own materiality. She is opposed to anthropocentricism, believing that when we ask of an object; how can I use this thing? we foreground a conventional (Western) perception of the passivity of things. If instead we were to ask; what can it do? (or, in Heidegger's terms; for what is this object ready-to-hand?) we could learn to better understand our political, social and economic drives and decisions. As long as we are unable, or we refuse, to dislodge our preconceived notion of matter as thoroughly inert and non-affective, (or, in Heidegger's terms, merely presentat-hand) we 'feed [our] human hubris and our earth-destroying fantasies of conquest and consumption' (Bennett 2010). Bennet refers to Bruno Latour's idea of an "actant" - a source of action, whether human or non-human - that has efficacy in that it can make a difference, produce an effect, and change or alter the course of events. If we were more inclined to accept the affect of objects, we might embrace ecologically superior and more materially sustainable modes of production and consumption, allowing a more eco-ethical culture to emerge (Bennett 2010).

Beating sheet-lead into the shape of the various trash-objects was a technically intricate process and this, together with lead's seductive, velveteen appearance, lent the objects a certain aura of monetary worth, despite them being representative of trash with all its negative connotations of unchecked excess, filth and ecological degradation. Initially I conceived of my lead pieces as "tokens" with the potential of symbolically expressing my appreciation for the tenacity and resourcefulness of the recyclers, but as this body of work developed, it became obvious that creating lead replicas of items of trash could signify on many more levels.

What might my artist intentions have been, therefore? After all, I could simply have exhibited the trash itself as found objects, arguing, as Bennett does, that all inert matter has the potential to affect. New York-based artist, Justin Gignac, developed a successful online practice packaging and selling items of trash, collected from the streets of New York, enclosed in slick Perspex boxes. Gignac's practice exemplifies the objet trouvé: found objects exhibited as art with no, or minimal, alteration by the hand of the artist. His boxes are visually appealing and 'in a Baudelairean sense, convey the beauty of the ruin and have intimations of mortality; they are "exotic" souvenirs which reference collective memory and a vicarious glimpse of "other" lives' (Whiteley 2011:6). But, as Whiteley (2011:18) cautions, ever since recycling has re-entered our consciousness as a 'fashionable rhetoric of sustainability', the contemporising of Baudelaire's original "rag-pickers" has increasingly become a global trope for redemptive purposes, while also articulating the disquiet of the wealthy West. 'The cultural re-appropriation of rag-pickers and their rubbish persists' (Whiteley 2011:18).

Whiteley's warning is pertinent for my lead objects and yet I believe that my artistic intentions pertaining to Hazardous Objects had little to do with Gignac's approach to trash as subject matter. Instead, my aim was towards a metaphorical analysis of the labour, skill and materiality involved in replicating these waste objects in the allegory-rich material of lead. I believe that if I had exhibited the items of trash themselves, I would simply have exposed trash for what it is - noxious, repugnant, disposable. But in re-presenting the trash objects as hand-crafted lead replicas, perhaps I could emphasise, or even exaggerate, Bennett's musings on the affective power of objects. By capitalising on the notion of the cultural/commercial value inherent in the "unique art piece" and using this together with the intrinsic indestructibility of lead, I sought to confer human value on the recyclers themselves, societal value on the work they perform and commercial value on the discarded items they collect.

My lead replicas, approximately fifty pieces in all, were created between 2008 and 2010. Apart from 12 of them - reworked into a visually beguiling series of works titled "Neontological Speciation" (2012), of which nine sold - no commercial interest has been shown, despite various gallery outings. This does rather undermine the notion of the value of an artwork, however, in mitigation, Julian Stallabras (2009) is of the opinion that art that finds itself to be non-commercial can stand in effective opposition to commodification. Quoting Lukács, he further argues that art offers qualities such as 'a form irreducible from content, an enriching objectification of the subjective, and a deconstruction of the opposition between freedom and necessity, since each element of the work of art seems both autonomous and subordinated to the whole' (Stallabras 2009:420).

In its physical properties and history, lead has ambivalent and contradictory potentialities, hence offering metaphors for both destructive and redemptive purposes. In its ability to transform under tensile stress or heat, the metal tends towards a state of flux, while still retaining the traces of its transformation. Its sombre, entirely unreflective surface is grey, never black or white. It is toxic but also has protective properties. And it is virtually indestructible. Physically and philosophically, lead was central to the various alchemical traditions practiced throughout Europe, Egypt and Asia. Alchemy can be separated into its exoteric (practical, proto-scientific) applications and its esoteric (philosophical, spiritual) aspects. It aimed to purify, mature and perfect certain objects, especially with regards to the transmutation of "base metals" such as lead into "noble metals", especially gold. Alchemy also concerned itself with the creation of an elixir of immortality, the production of panaceas able to cure any disease, and the development of an alkahest or universal solvent. Later, Hermetic practitioners viewed alchemy as fundamentally spiritual and the physical transmutation of lead to gold lost precedence to their aspirations for personal transformation, purification and perfection, ultimately with the hope of achieving immortality.

The alchemical symbolism behind the transformation of base-metal lead (the materialistic) to noble-metal gold (the spiritual) is not difficult to comprehend. Lead was abundant, it was easy to extract, and its matt-grey appearance rendered it unattractively dull. Although useful, it was considered commonplace and, consequently, was cheap. Gold was rare and difficult to extract and with its soft, otherworldly gleam was highly desirable, esteemed and expensive. Lead was a rudimentary and utilitarian metal, its function tangible. Gold had no real practical use at all but emblematically conferred wealth and worth on the possessor.

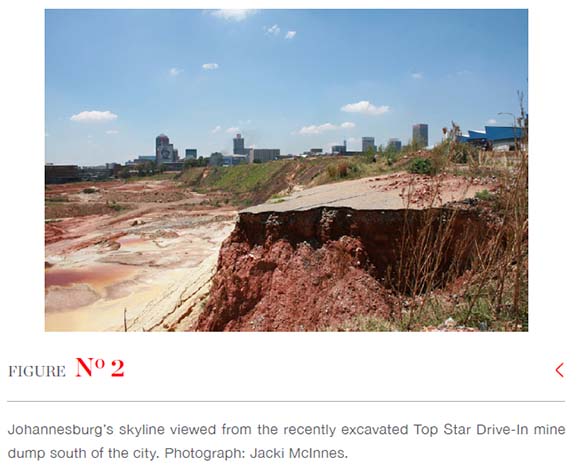

These metaphorical and alchemical references feed into my research on the recyclers and their position and role within the shifting fortunes of Johannesburg. The city was literally built on gold and on the backs of those who mined it. From its earliest gold-rush, shantytown beginnings to its glory days at the height of apartheid, to its fall from grace in the 1980s, to its current-day wobbly rejuvenation, Johannesburg's underlying infrastructure, both physical and societal, has always been exploitative and deeply inequitable. And yet, Johannesburg offers opportunities to every stratum of society and consequently enjoys a mythical "El Dorado" status for many, whether they be from poorly resourced rural communities, are economic refugees from other African countries, or belong to the increasing number of neo-fortune-seeking property developers looking to buy up their piece of the action.

Many creative practices require a specific mode of thinking - "thinking in images" - in order to access the creator's intended meaning. This, since imagery has the power to link heterogeneous objects or actions so that the unknown may be deciphered via the known. But at the same time, humans are inclined to overlook that which is commonplace, we do not really see the thing, we merely recognise it by its general impression. As the Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky (1917:162) observes:

A thing passes us as if packaged; we know of its existence by the space it takes up, but we only see its surface. Perceived in this way, the thing dries up, first in experience, and then its very making suffers ... This is how life becomes nothing and disappears. Automatization eats things, clothes, furniture, your wife, and the fear of war.

Shklovsky believed that art had the capacity to counter this automatization by prompting a more complete way of seeing things, rather than just recognising them. The unique device of the artwork in this task was its ability to increase 'the duration and complexity of perception' by the complication of the artwork's form, which de-familiarises or "enstranges" it from everyday objects (Shklovsky 1917:162). Ostranenie, as Shklovsky (1917:152) referred to this concept, was to interfere with an object's automatised (preconceived or presumed) meaning by taking it out of its usual context and making it seem foreign or surprising. A deeper analysis of the object is thus forced on the viewer, thereby encouraging a new encounter with reality. I would argue that my waste-objects could be understood in terms of Shklovsky's ostranenie. Refuse in the City of Johannesburg is ubiquitous and rank but by recreating rubbish in lead, that which is quickly discarded without consideration, now demands to be re-examined and re-evaluated.

In a similar vein, Maarit Mäkelä (2007:159-160) links artmaking and the production of knowledge, believing art to be a dialogue concerning the ideas, histories and ethical philosophies that the artist (and viewer) has a stake in and an opinion about. The art-object should not be the aim of the project but should function as the conduit to that which is intangible - that which can only be conceived, perceived, recognised or understood to offer the answer to the question posed. While for his part, Michael Titlestad (2012:51), referring to the House 38 series, suggests that my beaten-lead trash objects could be cyphers serving to warn that in the current late-capitalist era, unchecked consumerism and waste could likely overwhelm us. However, he also speaks of my transformation and translation of that which is residual or of little consequence, writing that I seek to reinterpret society's cast-offs in terms of the narrative of the intertwined nature of commodification, value and man (Titlestad 2012:51).

A number of prominent mid-twentieth century artists such as Richard Serra and Cornelia Parker have exploited the previously mentioned allegorical possibilities inherent in lead, using this conceptually in their work. However, it is Anselm Kiefer who, arguably, has taken lead to its greatest symbolic heights in the visual arts. Kiefer was born on the 8th March in 1945, exactly two months before the victory of the Allied forces in Europe on the 8th of May that year. Consequently, his meditations as poet-philosopher-artist are deeply informed by the catastrophic aftermath of the Second World War. His formative years revealed a shattered people unable or unwilling to speak of their past, since it held too many shameful secrets. He found in lead's "memory" (the fold marks, warps and natural oxidisation) the possibility of exposing and confronting these histories, believing that only in the recognition of Nazism's heinous acts would it be possible for Germans to reclaim the past and start the process of rebuilding their country and collective psyche.

Kiefer's paintings frequently contain materials and processes prone to mutation. Plant matter such as straw and sunflowers are intended to decay over time and his various oxidised and patinaed surfaces are highly unstable. Fire, too, is used in both destructive and transformative ways and it comes as no surprise that his work borrows heavily from alchemical traditions, both in exoteric application and esoteric consequence. In an interview with art critic Martin Gayford (2014), Kiefer proposed that all art can be considered in terms of alchemy in that a base material, whether paint, found object or bronze, is transformed into an artwork with real and conceptual presence. But Kiefer's key interest in alchemy lies in its analogous implications for personal transfiguration, purification and perfection. He adheres to the alchemical principle of "macrocosm-microcosm": the idea that processes that affect minerals can potentially also affect the human body. Therefore, if one were to find the physical secret of purifying gold from base-metal lead, one might conceivably find an associated philosophy to purify the human soul. Ultimately, Kiefer states that he is drawn to the enormous weight of lead, believing it to be the 'only material heavy enough to carry the weight of human history' (Gayford 2014).

At face value, House 38 was a gut-wrenching example of the toxic fallout of failed inner-city policies. However, assessed from the perspective of the recyclers, there were other nuanced and more complex stories to tell. Although in a perilous state, the building was their safe haven, essentially their "life raft". And in a city that cuts certain individuals loose, or leaves them to slip through the cracks, the image of the life raft is a potent signifier. In the face of desperation, these castaways were forced to find alternative strategies for survival. By recycling, they commodified items of trash and created new semblances of economic order out of the wreckage of society.

The vagaries of the city and of existence within it came into play early in the project: the community at House 38 was evicted by the "Red Ants" on 16 October 2009. Two days later a private developer bricked up the entrance and first-floor windows and the building was eventually renovated to provide low-cost student accommodation. My collaborator in the House 38 project, John Hodgkiss died unexpectedly on 15 March 2012.

In the years following the House 38 series, I continued to work around the themes of ecology, sustainability and inequality culminating, in 2016, with a project intended to explore the possibilities of re-contextualising or "re-purposing" Theodore Géricault's painting The Raft of the Medusa (1818-1819).

Géricault sought to use shipwreck imagery to illustrate the danger to which the French populace was exposed by a regime that put dynastic over national interests, gave the command of ships to political favourites, and allowed aristocratic officers to abandon their men in times of crisis. In response to his work, I proposed to stage a group of "shipwrecked" recyclers atop a Johannesburg mine dump. I, too, wished to caution that, as it was for Géricault's cast-aways, so it would be for contemporary South African society. We should not expect to escape unscathed when governmental and societal structures ignore the dire ramifications of our profligacy - and, worse, abandon the poor whose recycling work might offer a remedy. But simultaneously, I proposed that the recyclers' trolleys could be considered in terms of sea-going vessels and their drivers as seafarers. As the city's waste is piled into bulk bags and hauled to the numerous cash-for-scrap depots, so the pallet/raft is offered as a potent allegory for the self-reliant mariner using what little is available to survive.

Key to the shock French society expressed at Géricault's painting at the time - and especially to its harrowing back-story - was the sheer scale of the class disparity it exposed. In June 1816, the French naval frigate, the Méduse, set sail to repossess a colony in Senegal from the British. She did not reach her destination. Instead, her captain, appointed for reasons of political expediency rather than competence, and who had not put to sea in more than 25 years, ploughed the ship into the treacherous Arguin Bank off the coast of modern-day Mauritania. In the ensuing melee, the captain, his higher-ranking officers and the better-off passengers commandeered the lifeboats while the rest - 146 men and one woman - were herded aboard a makeshift raft hastily constructed from the timbers of the sinking ship. The raft was towed behind the lifeboats for a time but, with the better part of her floorboards submerged, she was exerting a tremendous drag. Barely hours later the towrope was slashed, casting her adrift. With scant water and supplies, no compass and subject to the alternating violent storms and sweltering heat off the West-African coast, the ragged group soon fell upon one another in acts of fear and desperation. All but 15 died in the 13 days before their rescue (Savigny & Corréard 1818:xiv).

The eradication of all forms of inequality was, arguably, the greatest aspiration of the majority of pre-democratic South Africans. But, contrary to expectations, inequality has not reduced and has in fact worsened in the past 28 years (Harmse 2013:3). Harmse (2013:3) adds that South Africa is currently reputed to have the highest Gini coefficient in the world and that this is, for the most part, in evidence in the country's major metropoles. First-world opulence is fiercely guarded within the impossibly high walls of security complexes and locked down behind the shatterproof windows of sleek sedans. Confronted by this evidence of inequality, the poor must become increasingly resourceful in the business of everyday survival. Moreover, inequality in South Africa is deeply racialised and, as such, our complex structure of inequality is even more prone to instability - quite simply, we are not all in the same boat.

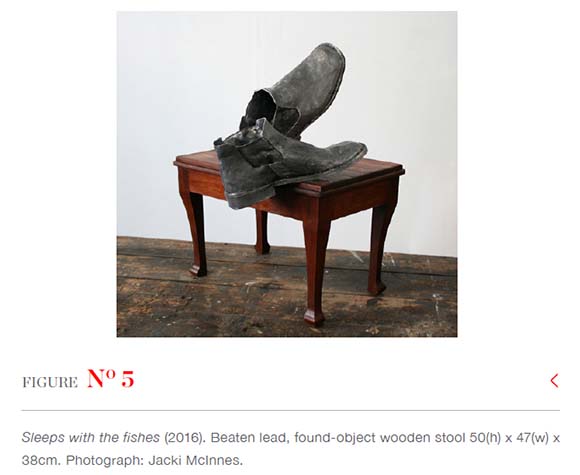

In preparation for my re-contextualisation exercise, I set about finding an appropriate setting, props and protagonists. By a series of lucky coincidences, I happened to meet a scrap steel collector (serendipitously named Buccaneer) while visiting possible sites for the photograph. He sourced a band of fellow recyclers and I arranged to work with photographer Leon Krige in January 2016. Ultimately, the photograph comprised 15 scrap-steel recyclers crammed into a tiny dinghy, placed atop a mine dump off Wemmer Pan Road, south of the City of Johannesburg. The resultant, large-scale photographic print formed a component part of an installation entitled Sleeps with the Fishes (2016)(Figure 4 & 5).

The installation presented a mine dump tableau in a cinematic format for the contemplation of an absent man - implied by a sculpture depicting a pair of men's shoes, fashioned from beaten lead, resting on a wooden foot-stool. The title of the installation obviously references the euphemism for death made popular in the 1972 film The Godfather: The Game in which Mafia boss Vito Corleone is told 'Luca Brasi sleeps with the fishes. We just fitted him for concrete shoes'. This method of disposal, allegedly developed by the Sicilian Mafia in America, involved encasing the victim's feet in poured concrete and dumping him, dead or alive, into deep water.

It was my intention to suggest that in an instance of socio-economic and racial disparity as extreme as that in South Africa, all members of the formal establishment are complicit to a greater or lesser degree. And, without doubt, all will be vulnerable. The empty shoes implied an absent viewer: mute, apathetic, and seemingly absurdly attached to the false notion that the crisis was neither of his making, nor that it would, inevitably, have the power to sink him too. I imagined the recyclers as the allegorical protagonists within three symbolic stages of ocean journey: initial progress, scuppered by shipwreck, but ultimately redeemed through the metaphoricity of the life raft. Their ocean journey was mediated in terms of a paradox of privation and survival and, keeping in mind the incongruity that Johannesburg is one of the biggest cities in the world developed in a place with no major body of water, I symbolically displaced the ocean with the dusty mine dumps that form the backdrop to the city.

Sleeps with the fishes staged Johannesburg's informal recyclers as shipwrecked castaways, marooned by the disintegration of their previous communal and economic structures. But shipwreck as a trope also offers the opportunity to explore existential themes such as innovation, endurance, spiritual and ethical resilience, and rebellion against authoritarian structures. Akira Yoshimura's novel Shipwrecks (1982) confirms this notion. Essentially, it is a parable that places human need in opposition to authority and the law and suggests that, in circumstances of extreme deprivation, it is to be expected that morality will be redefined and that this redefinition can gain legitimacy within the affected community in the form of a "purifying ritual".

Regarding Johannesburg's recyclers, I contend that codifying practices such as their attire, their patterns and modes of movement, and especially the trolleys on which they transport their recyclable materials comprise a self-authored purifying ritual. Their attire is robust (albeit scruffy), good walking shoes (often gumboots) are worn and, more often than not, a woollen balaclava is pulled over nose and mouth regardless of the season. The construction of their trolleys is not random, nor is it dependent on opportunistically sourced materials. Instead, it follows a distinctive design comprising a plastic, wheeled pallet sourced from supermarkets where they are used to move boxes of foodstuffs. There is a jarring irony in this, in that the abundance of food in the supermarket is profoundly at odds with the scarcity of the same for the recycler. In addition, the pallet which was originally used to proffer goods to the consumer is, in its new incarnation, used to hasten the cast-off garbage out of sight. A one-tonne, plastic-weave bulk-bag rests on top of the pallet and the trolley is directed by means of the collapsible folded legs of an ironing board used as both handle and steering device.

In my experience, the recyclers' homogeneity, as described above, is unique to Johannesburg. Although informal recycling is widespread in South Africa, as it is in many other developing cities the world over, I have not observed the same degree of unifying detail in any other metropole. In conversations I had with recyclers it was speculated that informal recycling originated within Johannesburg's community of illegal Basotho immigrants about 15 to 20 years ago, so this may provide a clue. But since then, the ethnicities of the recyclers have become widely integrated. I consider it significant that their attire and work methodology suggests a desire for self-identification. They seem intent on harnessing the power of a set of signifiers in order to clearly distinguish themselves from the rest of the population, as occurs in the formation of sub-cultures. Perhaps they do this - consciously or unconsciously - to lend credence to their work, which is generally maligned, or to their personhood, which is frequently disregarded.

In Shipwreck with Spectator (1996) Hans Blumenberg symbolically equates human existence with seafaring and writes that, since the time of early Greek philosophy, or even before, the sea was conceptualised as a natural boundary - earth understood to be under the dominion of Zeus, while 'out on the high seas, earthshaker Poseidon acts in accord with his own decisions' (1996:9). Blumenberg deems, with good and rational reason, that it is unwise to venture forth with impunity and yet he also acknowledges that humans always have, and always will, set out on sea voyages - or a contemporaneous equivalent. It is for this reason that humans place an inordinate importance on the perilous sea voyage for our metaphors of existence. Furthermore, he speculates that the allure and status of seafaring is contingent on its promise of adventure and riches and that it is not surprising, therefore, that in the ocean and in seafaring we 'encounter the culture-critical connection between two elements characterised by liquidity: water and money' (1996:9).

But seafaring must necessarily be associated with shipwreck, a catastrophic event which Blumenberg symbolically equates with the disastrous consequences visited upon those who over-reach their day-to-day needs, whether this be simply for survival, or in pursuit of prosperity, hubris or greed. However, he is also quick to concede that 'pure reason', would likely result in risk aversion, causing human progress to stall. Consequently, the ever-present hazard of shipwreck is the price to be paid in exchange for advancement and the discovery of both real and metaphorical new worlds (Blumenberg 1996:29).

Gisle Selnes adds that shipwreck and exile have inexorably been linked in human culture and writing, at least since Homer's Ulysses. 'However, exile is only one among a large number of possible metaphorical avatars of shipwreck. Shipwreck, ... as soon as it becomes the subject of linguistic or figurative representation, appears as so profoundly metaphorical that it might be taken as the vehicle of virtually any human experience which involves radical change or loss' (Selnes 2003).

It was always with a feeling of awkwardness and trepidation that I approached my photographic and interview sessions with the recyclers. Driving to their building and photographing them at work with a top-of-the-range professional camera posed a circumstance of gross imbalance from the outset. And yet, being one of the few members of the formal economy to actively engage them evoked, I would argue, a palpable sense of validation and pride, thereby setting up the possibility for a more equitable cooperation. I was struck, while conducting the interviews, by the absurdity of my questions regarding matters as intimate as their sleeping quarters and how much they earned each day. South African artist and academic, Raimi Gbadamosi (2017:[Sp]), articulates some of the pitfalls of polarised communications such as these:

[T]he negotiating parties have to accept the possibility of not getting what they want when they proceed with talks, and not knowing what the other party wants. It is this lack of awareness of what the other party truly wants or needs out of the negotiation, apart from what they state openly, which brings about contention inherent in negotiations. The powerful prefer negotiations. They have time on their hands, have more to give, less to lose, and what they do give, will come from an excess of whatever capital is being discussed. Dispassion born of plenty is a benefit when negotiating.

I would like to suggest, however, that when the empowered enter into conversations and/or negotiations with the disempowered, much can in fact be achieved. Despite the best efforts of both parties, lines of communication are dictated (frustratingly but usually innocuously) by a basic inability to understand one another's culture, experiences or language. And yet, as was the case with both the residents of House 38 and the protagonists of Sleeps with the fishes, when the subjects of the enquiry have grown so used to being stigmatised - and consequently disregarded, the mere fact that an enquirer takes the time to listen to their stories engenders a positive space for collaborative interaction. Simultaneously, by inserting myself into the uncomfortable and, arguably, dangerous world of the recyclers, I better positioned myself to tackle questions pertaining to the value chain that lies at the heart of my research.

German-American philosopher, Herbert Marcuse (cited by Felshin 2016) wrote that '[t]he truth of art lies in its power to break the monopoly of established reality to define what is real'. And perhaps this is what I hoped to achieve. I believe that my initial engagement with the recyclers themselves, subsequently mediated within my written and creative research, could go some way towards an understanding of their lived experience and, importantly, of the new ontological meanings and value they have conferred on themselves and on trash by means of their recycling work. Ultimately, I intended that the creative interventions deployed throughout these two projects would suggest an endless drift of time, people and circumstances, where matters of labour, profit and loss could be equated to the constant ebb and flow of the sea. Essentially, this creative body of work sought to trace a mediation between damage and possibility.

References

Barnes, J. 2015. Keeping an eye open: essays on art. London: Jonathan Cape. [ Links ]

Bauman, Z. 2004. Wasted lives: modernity and its outcasts. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant matter: a political ecology of things. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Blumenberg, H. 1996. Shipwreck with spectator: paradigm of a metaphor for existence. Massachusetts: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Bunn, D. 2008. Art Johannesburg and its objects, in Johannesburg: the elusive metropolis, edited by S Nuttall and A Mbembe. Johannesburg: Wits University Press:137-169. [ Links ]

Canby, V. 1972. Movie review: The Godfather. [O]. Available: https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/packages/html/movies/bestpictures/godfather-re.html Accessed 23 May 2016. [ Links ]

Cotter, H. 2009. Live hard, create compulsively, die young. [O]. Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/27/arts/design/27kipp.html Accessed 02 August 2017. [ Links ]

Diouf, M & Fredericks, R (eds). 2014. The arts of citizenship in African cities: infrastructures and spaces of belonging. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Douglas, M. 1966. Purity and danger: an analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Felshin, N. 2016. A photo exhibition about Israel and the West Bank that chooses sides. [O]. Available: http://hyperallergic.com/298529/a-photo-exhibition-about-israel-and-the-west-bank-that-chooses-sides/?ref=featured Accessed 04 September 2017. [ Links ]

Gbadamosi, R. 2017. A negotiation. [O]. Available: http://raimigbadamosi.net/RGb_Website.html Accessed 31 August 2017. [ Links ]

Gayford, M. 2014. Anselm's alchemy. [O]. Available: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/anselms-alchemy Accessed 17 June 2017. [ Links ]

Gevisser, M. 2014. Lost and found in Johannesburg. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [ Links ]

Harmse, L. 2013. South Africa's Gini coefficient: causes, consequences and possible responses. MBA dissertation, GIBS, University of Pretoria, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Hirsch-Allen, J. 2004. The Raft of the Medusa: an analysis of Géricault's portrayal of race, politics and class. [O]. Available: http://individual.utoronto.ca/jake/docs/classes/RaftofMedusa.pdf Accessed 14 April 2016. [ Links ]

Jones, M. 2011. Cars, capital and disorder in Ivan Vladislavić's The Exploded View and Portrait with Keys. Social Dynamics: A Journal of African Studies 37(3):379-393. DOI:10.1080/02533952.2011.657466 [ Links ]

Loschiavo Dos Santos, M. 2014. Design waste & dignity. Sao Paulo: Editora Olhares. [ Links ]

Lukács, G. 1923. The phenomenon of reification, in The object reader, edited by F Candlin and R Guins. Abingdon: Routledge:32-38. [ Links ]

Mäkelä, M. 2007. Knowledge through making: the role of the artifact in practice-led research. Knowledge, Technology & Policy. 20 (3):157-163. DOI 10.1007/s12130-007-9028-2 [ Links ]

Malcomess, B & Kreutzfeldt, D. 2013. Not no place: Johannesburg. Spaces and fragments of time. Johannesburg: Jacana Media. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. 2011. Democracy as a community of life. The Johannesburg Salon 4:1-6. [ Links ]

Mendelsohn, M. 2015. Why Géricault's Raft of the Medusa captured the minds of Frank Stella, Jeff Koons, Max Ernst, and so many more. [O]. Available: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-why-has-this-painting-inspired-so-many-contemporary-artists Accessed 2 August 2017. [ Links ]

Nuttall, S & Mbembe, A (eds). Johannesburg: the elusive metropolis. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Savigny, JBH & Corréard, A. 1818. Narrative of a voyage to Senegal in 1816. London: Conduit Street. [ Links ]

Selnes, G. 2003. The Metaphoricity of Shipwrecks; or Exile (not) considered as one of the Fine Arts. [O]. Available: http://www.lehman.cuny.edu/ciberletras/v10/selnes.htm Retrieved 23 October 2017. [ Links ]

Shklovsky, V. [1917] 2015. Art, as device, translated by A Berlina. Poetics Today 36(3):151-174. DOI: 10.1215/03335372-3160709 [ Links ]

Stallabrass, J. 2009. Trash, in The object reader, edited by F Candlin and R Guins. Abingdon: Routledge:406-424. [ Links ]

Strasser, S. 1999. Waste and want: a social history of trash. New York: Metropolitan Books. [ Links ]

Titlestad, M. 2012. Recycling the apocalypse. Art South Africa. 10(4):50-53. [ Links ]

Walker, S. 2014. Waste land: sustainability and designing with dignity, in Design waste & dignity, edited by M Loschiavo Dos Santos. Sao Paulo: Editora Olhares:17-28. [ Links ]

Whiteley. G. 2011. Art and the politics of trash. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd. [ Links ]

Yoshimura, A. 2001. Shipwrecks, translated by M Ealey. Edinburgh: Canongate. [ Links ]