Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Image & Text

versión On-line ISSN 2617-3255

versión impresa ISSN 1021-1497

IT no.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a27

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Haecceity and haptics: A critical explication of bookness in Speaking in Tongues: Speaking Digitally /Digitally Speaking

David Paton

Department of Visual Art, Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa dpaton@uj.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1585-3076)

ABSTRACT

Given the ongoing need for a more rigorous theoretical underpinning for book arts discourse, this essay conjoins a critical explication of my artist's book Speaking in Tongues: Speaking Digitally / Digitally Speaking, and the practice of making it, with selected foundational statements on the haptic experience of artists' books by Gary Frost. These statements provide a framework across and through which I am able to weave the explication. In order to do this, however, a history of the call for a more critical underpinning of the field is first undertaken. Thereafter, selected relevant theoretical tropes that have been influential on my thinking and practice are drawn together, forming a ground upon which the explication can be undertaken, focusing particularly upon haptic theory. This explication of artist's book practice acknowledges, and is predicated upon, the well-documented lack of a conclusive definition for such objects, and thus I attempt to foreground constituent concepts of bookness as critical and appropriate lenses for characterising and theorising the book arts.

Keywords: Artists' books, heteroglossia, smooth and striated space, haptic, self-consciousness, reflexivity, bookness, haecceity.

Introduction

In his recent (re)view of the book arts in the twenty-first century, curator of modern printed books and book history at the National Library of the Netherlands, Paul van Capelleveen (2022:21) refrains 'from postulating a new definition of the artist's book'. Despite this quashing of any expectation on the part of an eager reader, van Capelleveen spends the first nine pages of his extensive essay tracing the vexed, and often acrimonious, history of attempts to define the field of artists' books. What is clear from a close reading of this text is that, notwithstanding the call for a more critical underpinning of the field having first appeared some 40 years ago, we are no closer to adequately defining the artist's book. This lack, however, has not stood in the way of young artists and book designers getting on with their craft by working at the intersection of various disciplines without concerning themselves 'with the question of under which discipline their project falls' (Schouwenberg 2017:41). Likewise, Sarah Bodman (2019:10) describes a 'fluidity of practice between artists, designers, small presses, and publishers [that] has become more apparent in recent years across many countries' and where '[t]he borders between mainstream and art publishing are dissolving at quite a pace'. The ever-growing body of innovative, fluid, transdisciplinary and hybrid new book works slips in and out of analogue and digital platforms, unencumbered by conventional classes, fields and definitions. In light of this, book arts scholarship encounters an equally ever-growing need to provide adequate and appropriate theoretical tools for framing and explicating this diverse body of artefactual material.

If one accepts the lack of a definition for artists' books as a given, other, more useful tools must be provided. Johanna Drucker (1995:161) explains how artists' books enunciate their self-conscious and reflexive qualities by calling attention to the conceits and conventions by which a book normally effaces its identity. In this essay, I refer to such enunciation in terms of a book's bookness, isolating selected critical terms that create connective tissue between how an artist's book functions (its bookness) and the positioning of these critical terms as useful and appropriate theoretical frames for the explication of such objects. In order to do this, I provide a critical explication of my artist's book Speaking in Tongues: Speaking Digitally / Digitally Speaking, showing how this work embodies the concept of bookness which, I argue, is revealed when paying attention to the book's self-conscious and reflexive features. By paying further attention to the how and what of these self-conscious and reflexive elements, I am able to isolate heteroglot, smooth and striated space and, particularly, the functioning of haptic processes in the operationalising of such bookness.

What I argue for here, is the work's haecceity, its "thisness", particular things or characteristics that make for a work of art in book form, unlike one's expectations and experiences of conventional books. Thus, I am able to demonstrate that bookness can be read as a ground against which I am able to explicate both my practice and resulting artist's book, thereby providing appropriate theoretic tools for analysing artist's books and contributing to the field's discourse. The critical explication of Speaking in Tongues is framed by isolating selected pertinent statements by Gary Frost (2005) on the haptic experience of artists' books. These statements and explications are woven into readings on the haptic, thereby facilitating an argument for my book's characterisation of affective bookness. Given the lack of an adequate definition for the field of artists' books, the selected theoretical terms - heteroglossia, smooth and striated space, and haptic criticism - assume meaningful roles in constructing a framework for the characterisation of the elements of bookness that sit at the heart of the books that constitute the field.

A brief description of Speaking in Tongues: Speaking Digitally / Digitally Speaking

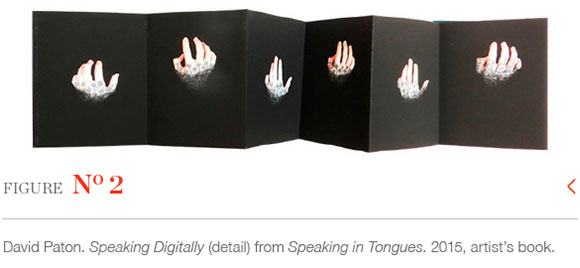

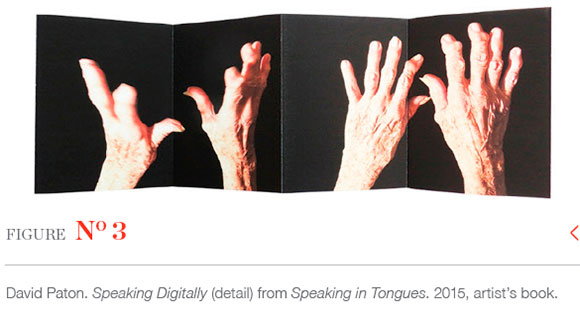

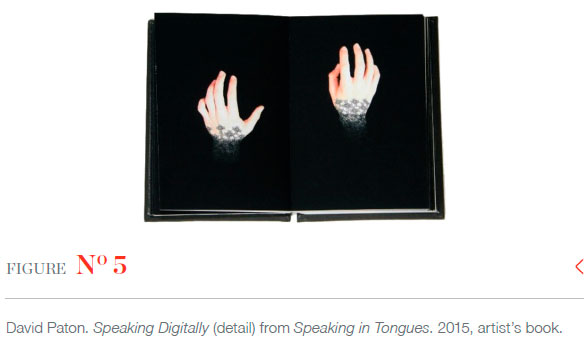

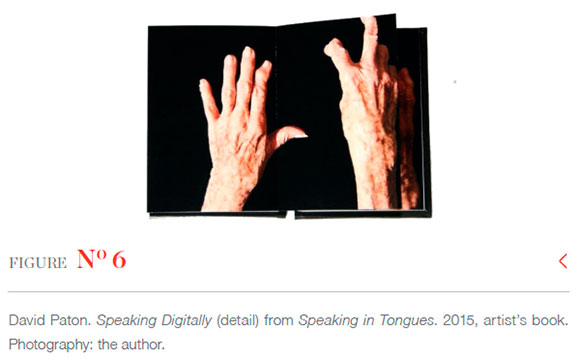

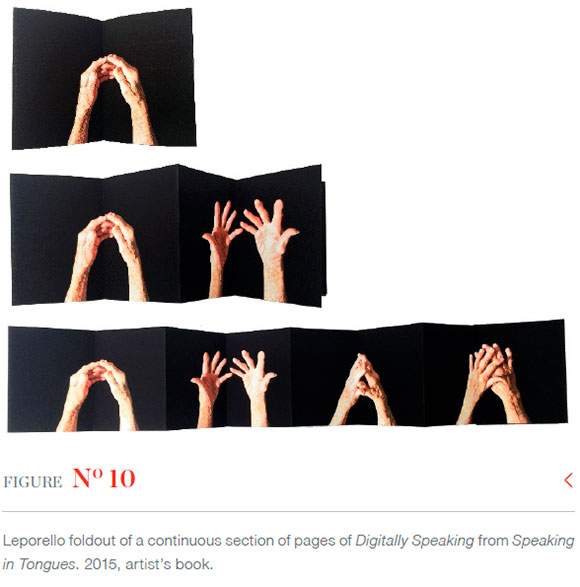

Originally conceived in 2009, the work was presented as a 185-page accordion-fold (leporello) book with independent covers allowing the book to be opened in conventional recto-verso page openings, in extended sections or, with great difficulty, in its entirety. It was small, being only 100mm in spine-height, but thick in depth. It was accompanied by a DVD containing a 15:42 minute video meant to be viewed at the same time as paging through the book. The book was printed in two sections on one side of the paper only. The first section depicted a sequence of my young son's hands subtly moving whilst playing an online game, the second depicted my aging mother's expressive hand movements that animated a set of spoken memories of her youth. The book contained no text except for the subtitles: Speaking Digitally introduced by my son's hand section and Digitally Speaking, introduced by my mother's.

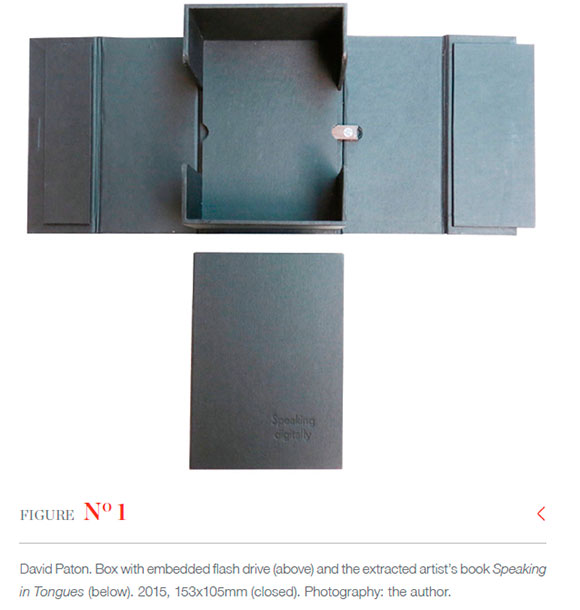

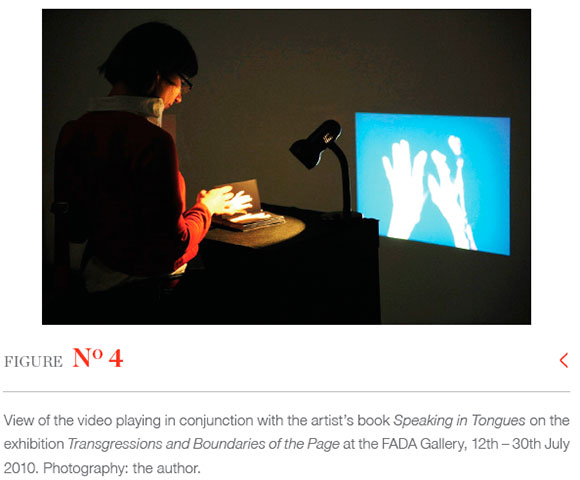

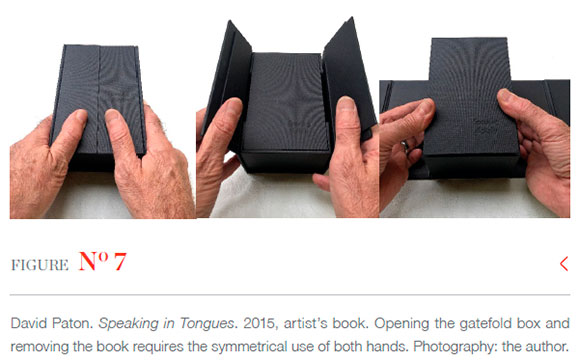

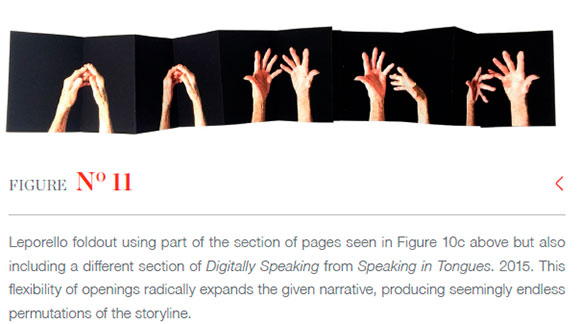

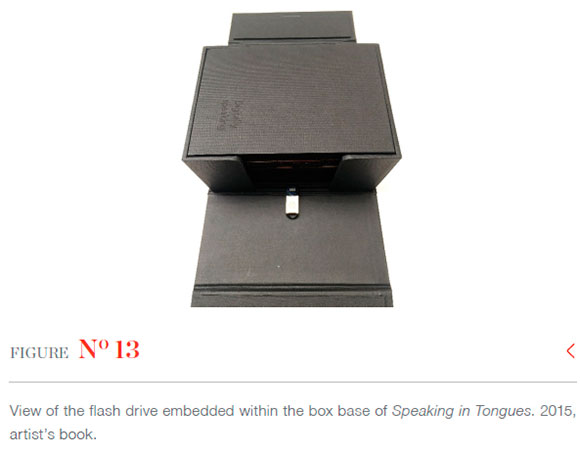

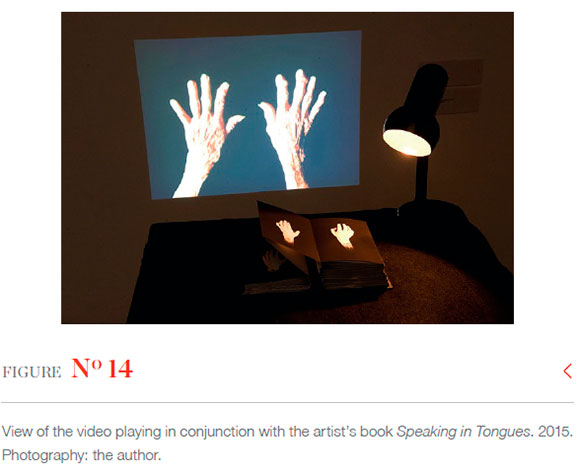

In 2015, in collaboration with the master bookbinder Heléne van Aswegen, I produced a special edition of six books and one printer's proof of Speaking in Tongues at The BookWorkshop, Stellenbosch. Here, each side of the Innova Smooth High White 220gms paper is printed with one of the sections - now considered a chapter - in EPSON UltraChrome TM inks. Each set of hands is carefully registered to synchronise with its counterpart on the other side of the long sheet of carefully scored and accordion-folded paper; an exceptionally difficult technical feat. This two-sided visual dialogue is not only a more elegant and economic way of printing the book, but helps organise the two chapters of the book as a conceptually continuous cycle without a defined front or back. This special edition now facilitates starting from either end, with all the page-turning and opening possibilities contained in the initial book. Each book in the edition is housed in a black fabric-covered gatefold box with magnetic strips for closing and the title and artist's name blind embossed onto the lower right hand cover section by hand letterpress in Gill. A re-edited 8:24 minute video is found on a tiny flash drive embedded in the base of the box. The video is meant to be projected at the same intimate dimensions of the book - 153mm (h) x 210mm (w), when opened. The reader is encouraged to view the video whilst reading the book so as to reflect upon differences in tempo and duration in each of the two narratives.2

Tracing the history of the call for a more rigorous critical and theoretical underpinning of the field of artists' books

In 2005, the eminent book artist and academic Johanna Drucker penned her now famous article 'Critical issues / exemplary works' in the first volume of the journal The Bonefolder. Drucker (2005a:3) directly challenged the broad book arts community to develop a much-needed critical language for artists' books, a more sophisticated theoretical voice, discrete from other art forms, when she wrote,

Because the field of artists' books suffers from being under-theorized, under-historicized, under-studied and under-discussed, it isn't taken very seriously ... Our critical apparatus is about as sophisticated as that which exists for needlework, decoupage, and other 'crafts'.

Drucker (2005a:3) continues,

I'd even go so far as to say that the conceptual foundation for such operations doesn't yet exist, not really. We don't have a canon of artists, we don't have a critical terminology for book arts aesthetics with a historical perspective, and we don't have a good, specific, descriptive vocabulary on which to form our assessment of book works.

Drucker's challenge took cognisance of a much earlier call for such work to be done. As far back as 1985, Dick Higgins (cited by Lyons 1985:12) asked pertinent questions regarding the field's theoretical discourse when he stated,

Most of our criticism in art is based on the concept of a work with separable meanings, content, and style ... But the language of normative criticism is not geared towards the discussion of an experience, which is the main focus of most artists' books. Perhaps this is why there is so little good criticism of the genre ... 'What am I experiencing when I turn these pages?' That is what the critic of the artist's book must ask, and for most critics it is an uncomfortable question. This is a problem that must be addressed.

In response to Drucker's challenge, Johnny Carrera (2005:7-9) wrote Diagramming the book arts while Gary Frost (2005:3-6) published Reading by hand: The haptic evaluation of artists' books. Neither were particularly well received by Drucker (2005b:10-11), whose withering response in Beyond velveeta states,

Asking for critical study in the field of artists' books is akin to calling for a capacity to distinguish between Velveeta and real cheese. If you can't tell the difference ... then you can likely be happy in the amateurish mind set of everybody-loves-everything that eschews 'critical' thought.

Drucker (2005b:11) ends by stating that '[a] community of artists that wants their work taken seriously must begin by setting serious terms for understanding their own work'. In this edition of The Bonefolder (Volume 2, Number 1, Fall 2005) an editorial postscript appeared directly after Drucker's article stating, 'Ms. Drucker's original article ... touched a nerve, especially regarding the issue of criticism and distinctions among the types of works and groups producing those works, but also about the need to be able to describe and explain one's work'.

Nearly a decade after this tense exchange in the book arts community, Thomas Hvid Kromann (2014:15) took stock of the progress that he felt had been made in developing a critical discourse of the field. He started by quoting Drucker's continuing lament, in the preface to the 2004 edition of her book The century of artists' books, (originally published in 1995): 'Where are the critics? The serious historians? The zones of discourse in which the field can reflect upon its own conceptual values? Ten years after the initial publication [of The century of artists' books], we are still struggling to get such activity to emerge'.

Kromann (2014:15) observed that,

Another ten years have passed since then. Have things changed? Yes and no ... There is still no counterpart to the critical response that exists within the literary field ... On the other hand ... since Drucker raised this critique ... the artist's book now has a history, canonical works, canonized artists, collections, fairs, experts, various subsidies, research programmes and so on - as well as an increasing amount of well-informed secondary literature.3

Also in 2014, and with particular reference to my explication in the final section of the essay, the Australian book artist and academic Tim Mosely (2014:45) resuscitated Frost's article 'Reading by hand' (2005:3-6) stating that,

Responses to Frost's article are few. Drucker responds very directly in the same Bonefolder issue, writing that '... The haptic could tend towards a literalist conflation of the object and the experience [of the book]' ... The apparent disregard in the literature over Frost's haptic features of the book may be a result of the immediate and dismissive response made by Drucker, the scholar who Frost was responding to. That no debate has appeared in the literature over Drucker's position on Frost's article again only exemplifies that lack of critical engagement in artists [sic] book discourse that Drucker identifies.

I find Mosely's resuscitation of Frost's focus upon the haptic qualities of artists' books most pertinent. Mosely (2014:120) argues that in '[r]aising questions over haptic qualities of the book, Gary Frost identified a significant resource for the emerging critical field of artists [sic] books'. Mosely (2014:89) points to Frost's identification of 'a new aspect to the discourse' through 'the aesthetic consequences of a work of book art in the hands of the reader where tactile qualities and features of mobility are appreciated'.

Mosely (2014:47-8) concludes that,

Drucker's concerns are clear and warranted if Frost's 'haptic' is limited to an adjective. Drucker, however, finds in Frost's ideas a trace of relevance beyond the literal (adjective) ... Drucker equates, or at least relates, the tactile to the haptic and in doing so draws into Frost's question a relationship between the haptic and the optic.

Drucker's (2005b:10) critique of Frost is, however, nuanced and not utterly dismissive, expressing an 'enthusiasm for Frost's emphasis on mobility and dynamism'. Nevertheless, she (2005b:10) does note that '[t]he devil is always in the application. His principles beg to be demonstrated in a case study'. In her earlier article, Drucker (2005a:4) had set out the terms by which she assesses quality and relevance in artists' books, by asking three basic questions of any work:

- what was the project set by [the] artist?

- how did this work transform, develop, or present that project?

- how does this project work as a book?

Drucker (2005a:4) states that 'answering these leads immediately back to the need for a critical terminology and descriptive vocabulary'.

Bookness, haecceity and their actionable characteristics: heteroglossia, and smooth and striated haptic space

Given the lack of an adequate definition for the field of artists' books, if I am to successfully explicate how Speaking in Tongues: Speaking Digitally / Digitally Speaking (2015) embodies the qualities of bookness, it is necessary to unpack selected theoretical concepts and explore their roles in contributing to a framework for characterising and embodying such bookness. The theoretical concepts of heteroglossia and the smooth and striated haptic space are first explored in order to set a ground upon which I can deploy Frost's Reading by hand (2005) as a framework across and through which I am able to weave both an explication of my book and my practice. In doing this I am also able to respond to Drucker's call for a case study in which the question, how does my project work as a book? is answered. At the same time, I am able to provide impetus for a critical terminology and descriptive vocabulary that productively contributes to the broad field of book arts theorisation and its discourse.

It seems a truism that writing about one's creative production is always far more difficult than producing the work. This is often put down to the fact that an artist's tacit knowledge about what they produce and how they bring an artwork into the world defies intellectual certainty before the processes begins. This notion might support Roland Barthes's (1977:147) argument that 'to give a text an Author is to impose a limit on that text, to furnish it with a final signified, to close the writing'. Meaning-making and artistic intent become attenuated and, as Barthes (1977:146) argues, 'the writer can only imitate a gesture that is always anterior, never original. His only power is to mix writings ... in such a way as never to rest on any one of them'. Barthes's ideas seem shot through with Bakhtinian dialogical heteroglossia which argues that 'all language, indeed every thought, appears dialogically responsive to things that have been said before and in anticipation of things that will be said in response to these statements' (Paton 2012:25). Bakhtin's ideas on dialogism and heteroglossia (first translated into English only in 1975) would soon find new expression in Julia Kristeva's (1980) writings on language, art and intertextuality, and be summarised by Tina Besley and Michael Peters (2011:95) as: 'All language and the ideas which language contains and communicates, is dynamic, relational and is engaged in a process of endless redescriptions of the world'.

The concept bookness underpins all aspects of my thinking, discussed here, and thus it seems important to unpack this concept a little so as to provide a compelling analysis of how bookness operates in Speaking in Tongues. There is, however, a caveat to this statement. My making relies, to a large extent, on tacit knowledge, unconscious prompts and many conflated conceptual, embodied and aesthetic ideas which, often, refuse to be untangled and conform to academic clarity and rigour. It seems critical to acknowledge that the excitement that a body of ideas provokes when they resonate or give rise to others is generative and at no point in the conceptualisation or making process do I interrogate them to see if they fit together academically or even logically. My artmaking is free of the burden that underpins my writing. What I am stating here is that bookness, when explored as an artwork, is an intuitive, haptic process that must make sense to me as a set of embodied relationships, not whether it stands up to reason or intellectual rigour. What follows, however, traces some of the theoretic complexity that acts as a ground upon which both my thinking and making has developed.

Notwithstanding the fact that the term bookness has been loosely applied within the field for many decades, it is often considered a self-evident concept that enjoys little critical examination. Philip Smith (1996) wrote 'The whatness of bookness, or what is a book in response to a letter the editor of the online Book Arts Listserv Philobiblon, Peter Verheyen, wrote to the editor of the Designer Bookbinders Newsletter concerning the term bookness. Smith (1996) claims to have

coined the term 'bookness' in the 1970s (after reading in James Joyce's Ulysses of the 'horseness of horses' - the whatness of horses - this led me to coin it as 'the whatness of the book' or 'bookness'), and I have written and spoken about it elsewhere, with various updates of understanding of the issue.

The concept of bookness has been deployed by others in the field (Drucker 1995, Pórtela 2011, Cooper 2014) yet, from outside the field, appropriately eloquent synonyms might be found in the philosophical concept of quiddity. This term, derived from the Latin quidditas, means whatness or 'what it is', defining the literal essence of an object. A second term is hypokeimenon (Greek: únoKeíuevov) or 'underlying thing', defining that substance which persists in a thing - its basic essence. A third term, however, seems closer to both my idea of bookness as well as the way in which one might ponder on how the body experiences and makes phenomenological sense of something; in this case, my book. This is the concept haecceity. Derived from the Latin haecceitas, it is defined as the discrete qualities, properties or characteristics of a thing that makes it particular: an object's thisness. In 1967, ethnomethodologist Harold Garfinkel used the term haecceity to enhance the inevitably indexical character of any utterance, occurrence or condition. Drawing on phenomenology and the inductive and aesthetic theories of Nelson Goodman, Garfinkel (1967) used the term haecceities to indicate the importance of the infinite contingencies in all utterances, occurrences or conditions. It seems inevitable then, that Gilles Deleuze (2005:266) uses the term to denote entities that exist on what he calls the plane of immanence stating,

There are only relations of movement and rest, speed and slowness between unformed elements, or at least between elements that are relatively unformed, molecules, and particles of all kinds. There are only haecceities, affects, subjectless individuations that constitute collective assemblages ... We call this plane, which knows only longitudes and latitudes, speeds and haecceities, the plane of consistency or composition.

In trying to pinpoint the centripetal haecceity of a book, its discrete qualities that make it particular, it seems, somewhat counter-intuitively, that one must first accept the centrifugal implication that, in Bakhtin's heteroglot terms, a concept - even a book - must appear responsive to all things that have been stated before whilst anticipating all things that will be said in response in endless redescriptions of the world. I have discussed the heteroglot nature of artists' books historical and formal relations elsewhere (see Paton 2012), but is seems necessary to first restate Bakhtin theorist Michael Holquist's (2002:70) observation that,

All utterances are heteroglot in that they are shaped by forces whose particularity and variety are practically beyond systematization. The idea of heteroglossia comes as close as possible to conceptualizing a locus where the great centripetal and centrifugal forces that shape discourse can meaningfully come together.

Bakhtin's 1975 Discourse in the novel (cited by Holquist 1981:291) points out that heteroglossia

represents the co-existence of socio-ideological contradictions between the present and the past, between differing epochs of the past, between different socio-ideological groups in the present, between tendencies, schools, circles, and so forth, all given a bodily form.

A heteroglot lens reveals the artist's book to possess a protean bodily form with a diverse, contradictory yet extremely rich historical and formal canon. In support of Bakhtin, Deleuze and Guattari's (2005:7) pure notion of a book is equally centrifugal, noting that its haecceity is located in its unattributable multiplicity as a complex assemblage. In their Introduction: Rhizome, Deleuze and Guattari (2005:3-4) expand on the infinite contingencies in all utterances in their description of what a book is.

A book has neither object nor subject; it is made of variously formed matters, and very different dates and speeds. To attribute the book to a subject is to overlook this working of matters, and the exteriority of their relations ... In a book, as in all things, there are lines of articulation or segmentarity, strata and territories; but also lines of flight, movements of deterritorialization and destratification. Comparative rates of flow on these lines produce phenomena of relative slowness and viscosity, or, on the contrary, of acceleration and rupture. All this, lines and measurable speeds, constitutes an assemblage. A book is an assemblage of this kind, and as such is unattributable. It is a multiplicity.

Pete Wolfendale (2009:[Sp], emphasis in original) states that, for Deleuze, these haecceities and the indexical nature of the book's assemblage, are 'entities [that] are constituted out of other entities. However, the important point is that they are constituted out of the interactions of these entities. These interactions are properly causal interactions' and, in their indexicality, are usefully heteroglot characteristic of bookness, exposing both self-consciousness and reflexivity. When Bakhtin's (cited by Holquist 1981:291) heteroglossia represents the co-existence of socio-ideological contradictions between the present and the past, what I find particularly apt is how it anticipates Deleuze's centripetal haecceity of a book as a conceptual space that can accommodate an object such as an artist's book. Within this plane or ground, my artist's book is able to respond, dialogically, to the entire history of the genre and its possible futures while, in heteroglot terms, also able to accommodate structural relationships that are multivocal, self-conscious and reflexive in very particular ways. I unpack these in the final section through the examination of the haptic.

I made Speaking in Tongues as an object that explores haecceity without any need for transcendent interpretations outside of itself. Fredrika Spindler (2010:154) explains haecceity - an entity within Deleuze's plane of immanence - as an act of willpower: 'it is the question of the effort of subtracting from chaos specific, high-intensive composites on the horizon that has no other guarantee but its own strength of resistance against the chaos of infinite speed'; a powerful metaphor for the creative act. Speaking in Tongues is that object which exists within both a history of such objects, from the most generalised concept of the book arts (along a time-sensitive axis) to the most particular conceptual and material characteristics of one-of-a-kind exemplars (along a structure-sensitive axis). In this manner, the book can depict the "thisness" of its own haecceity as a set of heteroglot voices that speak both multi-dimensionally and multimodally.

Mosely (2014:24) calls Deleuze and Guattari's description of a book consummately haptic, stating that, '[r]ather than a crisp concise description of the book, their writing presents surfaces that the reader must move over, across and around ... This movement requires more of a reader's time than is commonly expected of reading'. Thus, the second theoretic trope that requires some attention in unpacking a book's haecceity, are Deleuze and Guattari's (2005) ideas on haptic smooth space within creative and artistic practices. For them (2005:493), smooth space 'is both the object of a close vision par excellence and the element of a haptic space (which may be as much visual or auditory as tactile'. Like their image of the rhizome, Deleuze and Guattari (2005:493) define smooth space as nomadic, as traversing through an environment relying on an immersive perception of it, informed by the intimacy of the space, where one can 'lose oneself without landmarks'. Smooth spaces are linked, in their aesthetic model4 to concepts of the haptic, closeness,5immediacy and the abstract (Mosely 2012:37). This is in contrast to striated space, which is linked to concepts of the optical, distance and the concrete, such as mapping a space between two points. When Mosely (2014:24) calls Deleuze and Guattari's description of a book consummately haptic, what he infers is that smooth and striated space must be defined by the nature of a body's engagement with a book as 'a place' (Mosely 2012:39, 2014:26). The more reliant a person is on their haptic perception of a place, the smoother is their experience of that place. Conversely the more reliant a person is on their optical perception, the more striated their experience becomes. Mosely (2012:39) asks if Deleuze and Guattari's abstraction of the haptic might offer 'a means to advance the emerging critical discourse on artists' books?' also stating that Deleuze and Guattari 'identify our relationships with artifacts (artists [sic] books) - that is, our reception and evaluation of them - as movements between haptic smooth space and optic striated space' (Mosely 2016:37).6 I conceived of Speaking in Tongues as striated space upon its making - beginning with one cover and proceeding through its narrative until another cover announces both a terminus to this narrative and the start of another. It must, however, also be perceived of as smooth space by a viewer's body upon its reception; a dialogical reading that slips between the book's haptic materiality and the video's silent temporality, where one can 'lose oneself without landmarks'.

The book artist and academic Robbin Amy Silverberg (2017:20) states, 'Returning to the artist [sic] book, understanding its haecceity could clarify why we make them. Or, I shall take another tack and pose that the very act of making an artist book or being an actor in making them, can perhaps clarify its essence'. I argue that the qualities of bookness, as they present themselves in Speaking in Tongues, may be received in its multi-dimensional and multimodal heteroglossia, its combination of smooth and striated space, and via complex readings through haptic processes. Together, these theoretic tropes embody and visually constitute the book's haecceity and "thisness". In the next section, it seems important to spend some time with the concept of the haptic, while, in the final section of the essay, I weave pertinent statements put forward by Gary Frost (2005:3-6) in his article 'Reading by hand: The haptic evaluation of artists' books' through an analysis of Speaking in Tongues that helps to unpack the work's bookness, its haptic self-consciousness and its haecceity. At the same time, I am able to respond to Drucker's earlier concerns with the haptics' applicability to the theoretical discourse of the artist's book, and answer the question 'how does the project work as a book?'

The haptic: Touching as seeing.

In attempting to answer Drucker's three questions - as stated above - I offer a truce of sorts in which Drucker's (2005b:10) concern that '[t]he haptic could tend towards a literalist conflation of the object and the experience' is kept at bay. In response to Drucker's lament at the under-theorisation of the field of artists' books, Frost (2005:3) asks: 'Are there any additional approaches that will assist evaluation of artistic works in a book format? I suggest that there is an additional topic that could propagate additional tools ... This is a haptic [pertaining to the technology of touch] domain where the study of touch as a mode of communication is at work'.

Studies into the nature, importance and affective qualities of the haptic have occupied some of the world's greatest minds since Descartes' philosophical treatise on optics Dioptrique was published in 1637 and in which he hypothesised that the blind 'see with their hands'. Mark Patterson (2007) delves into this history to question if

the assumption of an equivalence of the senses, substituting hands for eyes, touch for sight, is fundamentally to ask whether sensory perception is straightforwardly cross-modal (or inter-modal, sensory information being transferable from touch to vision) or actually amodal (sensory information being prior to its processing as specifically audile, visual, tactile, etc.).

Paterson (2007:40-41) writes that,

In 1709 Bishop Berkeley provided a new twist to the debate, arguing for the specificity of the modalities of touch and sight and denoting a stark separation between the senses. In asserting that there are no 'general ideas' that stand outside immediate experience he agrees with [John] Locke, but goes so far as to deny that space is visual at all ... One of the fundamental premises of Berkeley's empiricism, space is therefore not visual but haptic.

Jenni Lauwrens (2019:18), in her exploration of the reciprocal relationship between images and viewers through the relationship between sight and touch, reminds us that '[i]n the late nineteenth century, Alois Riegl described two ways in which art can be looked at: optic and haptic. Optical looking amounts to scanning the outline of objects. Haptic looking focuses on surfaces'. Patterson (2007:41) provides a restructured view of Berkeley's position stating that 'instead of the empirical view of Berkeley that "touch teaches vision", [David] Warren and [Matt] Rossano update this in terms of developmental psychology to say that "tactile/motor experience 'calibrates' visual experience"'. He (2007:51) describes such calibration in terms of touch becoming 'the tutor of the other senses, training sight to provide depth to the visual field ... what Merleau-Ponty calls the "thickness of the world"'.

Such thickness is interpreted by Laura Marks (2002) through what she terms Haptic Criticism. In response to Deleuze and Guattari, she (2002:xiii, xv) states,

The haptic critic, rather than place herself within the 'striated space' of predetermined critical frameworks, navigates a smooth space by engaging immediately with objects and ideas and teasing out the connections immanent to them ... Haptic criticism cannot achieve the distance from its object required for disinterested, cool-headed assessment, nor does it want to.

Marks (2002:xvi) states that her haptic criticism of art is located 'in, and not despite, the material and sensuous world'7 and that '[t]he best criticism keeps its surface rich and textured, so it can interact with things in unexpected ways. It has to give up ideas when they stop touching the other's surface' (Marks 2002:xv). To this, Mosely (2016:36) responds by stating that the haptic

dynamically informs the perceptual relationship between a person and an object/subject ... by the constant movement of the perceiver's senses over, around, and across the surface. If this movement ceases, the nature of the perceiver's relationship with the object/subject moves away from the haptic towards 'the optic'.8

Jacques Derrida (2001:20) states that

from Plato to Descartes to Berkeley to Bergson and Husserl - the fullness of intuition, of the knowing intuition, implies literally or figuratively, an experience of touching ... In the case of Hysserl ... he insists ... on the absolute privilege of touching, and especially on touching oneself touching, of the touched - touching body as the only possible experience of the body ... This is a possibility he firmly denied to seeing: you cannot see yourself seeing, he claimed, in the way you can touch yourself touching.

Mosely cites Claire Colebrook's (2009:33), identification of a crucial aspect of this discourse: 'The haptic is not the tactile, [it is] not a touch taken by the commanding hand for the sake of the viewing eye and the speaking mouth'. Understanding this facet of the haptic, states Mosely (2014:47), 'in which touch is taken beyond its conventional context of the tactile and into the very edges of making sense, is essential to appreciate Derrida's observation and what Deleuze intuits within the haptic'.

Reading by hand: An explication of Speaking in Tongues as a haptic generator of meaning

With this positioning of the haptic in place, I have selected specific statements from Frost's Reading by hand (2005) against which an analysis of the ways in which haptic processes characterise reflexive aspects of Speaking in Tongues' bookness helps provide fruitful connective tissue within the perceived gaps in the discourse. I now fold Frost's pertinent statements on the haptic into and across the surfaces of my book in the form of reflective responses.

This topic is the aesthetic consequence of a work of book art in the hands of the reader where tactile qualities and features of mobility are appreciated . Such evaluations call up deeply embedded perceptions and sensory skills where the hands prompt the mind and where the reader's understanding can be far removed from the intentions of the artist (Frost 2005:3).

In a conversation with Mark Dimunation, Chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division of the Library of Congress, Washington DC, in February 2019, I was intrigued with his response to my description of one particular aspect of Speaking in Tongues. He replied: 'Well that's not what I was experiencing when I looked through your book!' This came as no surprise as I had only related to him one highly personal reading of a section of one of the book's two sides: where the image of my young son's hands disappears from view under a matrix of patterned black ink. Notwithstanding our divergent readings of the narrative - anything other would impose a limit on that text, furnish it with a final signified and close the writing/meaning as Barthes (1977:147) describes - I was interested in his use of the term 'experiencing'. It mattered not that two people had completely different experiences of the meaning of the book, what was important was that both of us experienced the book as a generator of meaning, and this mode of generation was haptic, where technologies of touch are at work as a mode of communication. The subject matter of the work (two sets of animated hands, one old and one young, printed, respectively, on each side of an extended length of folded paper) as well as the intimate scale of the book (153x105mm when closed), invites haptic investigation. It seemed appropriate to me that a reader's hands would manipulate and control the stories told by the depicted sets of hands across generations of experience. Clearly, the hands are narrating something about time through the indexicality of their respective ages and through the viewer's experience of duration and difference in the two narratives.

What instigates the reader's ergonomie of comprehension and how are haptic features consequential to the evaluation of book art? ... This primary corporeal nature, both as an analogy to human anatomy and as a hand-held object, provides a primary descriptor of the physical book... To profile the haptic nature of artists' books perhaps we should first focus on a fundamental shared orientation of the body and book. This first feature is a curious simultaneous bilateral symmetry and asymmetry; a fantastic attribute that is deeply embedded in both book and body (Frost 2005:3-4).

The book is housed in a box with a magnetised gatefold opening with the title and artist's name blind letterpress printed into the right hand bottom quadrant. The title alerts the reader that the content of the book concerns some form of communication and, beyond the possible spiritual allusions, concerns the body's communicative faculties as subject. This decision to incorporate the gatefold opening is not incidental as, in order to open the box and extract the book, a reader must employ both hands. David Prytherch's (2002:6) research into the implications of the haptic for artists' making processes concludes that 'the use of two hands working cooperatively elicited the most information in the shortest time'.

David Paton. Speaking in Tongues. 2015, artist's book. Opening the gatefold box and removing the book requires the symmetrical use of both hands. Photography: the author.

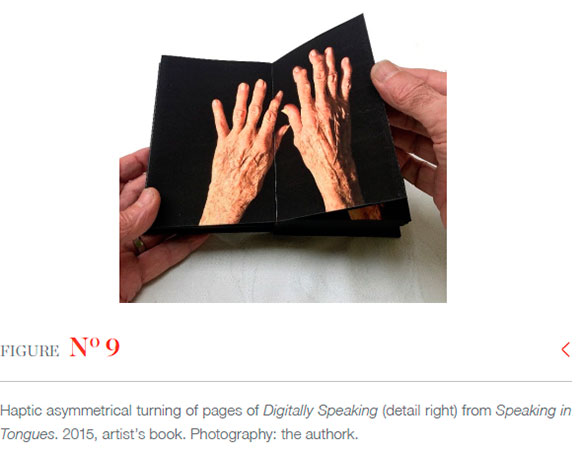

Our unique right or left handedness is the progenitor [of] our crucial neural asymmetry of the brain. The asymmetry of the symmetrical codex is just as fundamental, but with a special twist. As the leaves change places with each other the right page becomes the left page as the clock of content goes forward. Two hands, each acting alone, hold the book and turn the page. This initially simple circumstance of symmetry/asymmetry of the body and book is opened to endless permutations of artists' books (Frost 2005:4).

This initial mental image of the reader's hands opening the box and carefully extricating the book becomes important when, again, both hands are required to open the book. These hands then reveal the image of two hands - on slightly smaller scale, printed in recto/verso on the double page openings - slipping across the page gutter. The self-consciousness at play here binds the hands of the reader with the hands of the subject in a reflexive loop of indexical, causal meaning. For the book's subject (two silent stories narrated by two sets of hands) to be activated and communicated, the reader's hands, both left and right, must assume agentic power, making 'the right page become the left page as the clock of content goes forward'.

But how can we provide effective description for a more critical experience of the corporeal book? We can lift it, open it and turn a page. Is it docile or springy on opening, solid or tentative on closing? Is there a live transmission of forces through the structure or is it crippled? (Frost 2005:3).

The structure of the book - double sided, open-spine, accordion-fold binding -facilitates multiple and complex combinations of openings which the reader is invited to explore. Readers are immediately made aware that the structure of the book undermines the conventions of the codex, loosens the book's fixity and allows for the book to seemingly come apart. In reading the book, one does not so much turn the page - although this is entirely possible - as work out just how far the open-ended structure of the book is allowed for by the limits of the reader's body. It is possible to open a single recto/verso spread, open multiple sections of the visual narrative, or place the book on its base, open it in its entirety, and walk around it to view the dual narratives printed on each side, as if it were a sculpture. Deleuze and Guattari (2005:9) state that '[t]he ideal for a book would be to lay everything out on a plane of exteriority of this kind, on a single page, the same sheet: lived events, historical determinations, concepts, individuals, groups, social formations'. Given its length, and without due care, however, the book will collapse into a mass of confused openings.

It follows that haptic features are consequential for considering the often unconventional and experimental formats of artists' books. The haptic concern also follows from the peculiar essence of the book as hand held art... The whole environment of this experience is tactile, manipulative, confined, tricky and surprising ... Many artists' books have a rag doll mobility that does nothing to inform the curiosity of the hands and most artists' books lack the engineering that provides direct response to the leverages of handling (Frost 2005:3-4).

The intimate size of the book belies its leporello flexibility. A single recto/verso double-page spread measures a mere 210mm in width, but it is possible to unfold and reveal the book's 81 pages in their entirety, which would measure 16,2m! This is indeed a peculiar essence, as one's conventional reading experience does not accommodate such haecceity. In a most self-conscious manner, the book invites its reader to engage with its physical and structural qualities as an act of both bodily exploration and haptic meaning-making. Paterson (2007:46) examines the spatial aspects associated with the haptic touch:

Noting the use of 'foveation' as a term of equivalence between sight and touch, we find that in addition our attention is drawn to the distinction between the haptic (or prehensile) and locomotor explorations of space ... The reach-space of the hand and fingers is said to be 'prehensile space', hence the foveation analogy, while 'locomotor space' implies the movement of the entire body. Whether in immediate prehensile space or in the locomotor space afforded by movement, the notion of externality and the cognition of space ... is often performed and mediated through the hand.

Frost's (2005:3) description of this experience as 'tactile, manipulative, confined, tricky and surprising' is apt, especially as the book contains two separate narratives, one on each side of the page, a strategy only made possible by the structure of the binding and only found in such smooth spatial and temporal proximity in the form of the book. But Speaking in Tongues invites even more. By standing up, moving about and stretching and shaping the accordion-fold structure to its fullest length, a kinaesthetic awareness comes into play. Citing the work of Révész (1937), Paterson (2007:53, emphasis in original) states that '[e]ven the visual perception of the world, he argues, has a tactile and kinaesthetic component, and therefore there is no separate visuo-spatial image that is distinct and identifiable without the "tactual-kinaesthetic functions"'. Awareness of these aspects of bookness makes the haptic experience of viewing Speaking in Tongues a particularly self-conscious, reflexive and embodied one, recalling Marks' (2002:xv) observation that '[t]he best criticism keeps its surface rich and textured, so it can interact with things in unexpected ways'. Such conjoining of rich haptic criticism of the surprising surfaces of equally rich art objects provides a strong theoretical lens with which to examine the artist's book, thereby enriching the field's discourse.

Each reader wishes the book to act out a bit of personal theater and I suggest that book art is special in this regard (Frost 2005:3).

The intimate size of the book and its filmic sequentiality also suggest that the pages could be flipped. Forcing Speaking in Tongues to operate as a flipbook, however, proves impossible with the structure collapsing into a heap of unruly pages. The book seems as if it has a mind of its own and refuses any haptic manipulation which is not caressed by the hand with due care. The filmic sequentiality is, however, a critical part of the book's initial concept, its interior dialogues and structure. Initially, I videoed both my son and mother's hands as I conversed with them on various personal topics. From the thousands of frames, I selected short sequences that I transformed into the printed images of the book. For the special edition, the separate video narratives were edited into a single-channel, 8:24 minute sequence in which both narratives are intertwined and where moments of visual similarity and congruence are acknowledged. The video is silent and meant to be projected ahead of the book in equally intimate scale. In this way, the reader is encouraged to view the video whilst reading the book so as to reflect upon differences in tempo and duration in each of the two narratives. Naturally, the video runs at its own tempo and sequence, outside of the directives of the reader who, nonetheless, has complete control over their haptic experience of reading the book. The reader controls the sequence and pace at which the book is read, whether to remove the book from the environs of the video or when and whether to close the book and end the narrative.9 Together, these two elements constitute the project Speaking in Tongues.

Conclusion

If critically pursued, the consciously hand investigated book could induce a greater appreciation of artists' books (Frost 2005:3).

In Speaking in Tongues, I have attempted to convey what Drucker (1995:161) terms enunciation10 - by calling attention to the conceits and conventions by which a book normally effaces its identity. I have achieved this by paying particular attention to the book's self-conscious and reflexive qualities. In doing this I have confronted Drucker's three questions when considering the quality and relevance in artists' books: what was the project set by the artist? How did this work transform, develop, or present that project? And particularly, how does this project work as a book?

How an idea works in book form seems to demand, in Frost's (2005:3) view, an experience that is tactile, manipulative, confined, tricky and surprising. If one pays close attention to the self-conscious and reflexive features of an artist's book, one is able to appreciate the work as exhibiting qualities of bookness. Here, by paying attention to the how and what of such self-conscious and reflexive elements, I am able to isolate heteroglot, smooth and striated space and, particularly, the functioning of haptic processes as the nuanced operationalisation of my book's bookness. What I have argued for here, is the work's haecceity, its "thisness", the particular characteristics that make for a work of art in book form, unlike and beyond our expectations and experiences of conventional books and without having to explain the tedium of "what the book is about".

Book artist and scholar Tim Mosely (2014:120), who has devoted much time to the importance of the haptic to the discourse on artists' books, identifies Gary Frost's text as 'a significant resource for the emerging critical field of artists books'. Through his research, Mosely attempts to verify 'that it is imperative that the haptic be embraced by artists who make books and by those who engage in artists book discourse'. He (2014:120) concludes that '[c]ontemporary discourse on haptic aesthetics has identified a clear difference between the optic tactile touch and the haptic touch. While the tactile touch serves the visual and aural, the haptic touch enters the edges of making sense'. I have shown how, through the operationalisation of the qualities of bookness: heteroglot utterances across time and within material and conceptual axes, the experiences of the making and reception of the book as both striated and smooth space, and the manner in which haptic criticism enriches these experiences, the artist's book Speaking in Tongues is able to demonstrate its haecceity - the discrete qualities, properties or characteristics of its "thisness". As Deleuze and Guattari (2005:4) state: 'We will never ask what a book means, as signified or signifier; we will not look for anything to understand in it. We will ask what it functions with'. A fruitful answer to this question might point to books that are 'endlessly complex and nuanced; their surfaces ... textured and porous' in surprising, unexpected and embodied modes of searching (Marks 2002:xv).

Acknowledgements:

This essay has been developed from the final section of my Ph.D Thesis 'Booknesses: Framing Book Arts Theorisation, Curation, Documentation and Practice within a South African Context', submitted to the University of Sunderland, UK, 2019.

Notes

1 The special edition reduces the original, unwieldy 185 single pages to 81 double-sided pages.

2 The book has been taken into the collections of The Jack Ginsberg Centre for Book Arts, Wits Art Museum, Johannesburg; the Templeman Library, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK; the Mary Austin Collection, San Francisco Centre for the Book, San Francisco, CA, USA, and the Van Abbe Museum, Eindhoven, the Netherlands.

3 This secondary literature is not without its South African contributors: amongst others are Robyn Sassen (2004, 2008, 2017), Estelle Liebenberg-Barkhuizen (2009), Pippa Skotnes (2009, 2017), Keith Dietrich (2011, 2017), Phillipa Haskins (2013) and my own contributions since 1996.

4 In Deleuze and Guattari's A thousand plateaus (2005) the aesthetic model (nomad art) is the final part of their final chapter 14, '1440: The smooth and the striated'.

5 Their ideas of closeness and smooth space are derived from art historian Alois Riegl's term 'close vision-haptic space' in Die spdtromische kunstindustrie (1927). They are also indebted to Wilhelm Worringer's Abstraction and empathy: A contribution to the psychology of style (1963) and Henri Maldiney's Regard, Parole, Espace (1973) especially 'L'art et le pouvoir du fond,' and his discussion of Cezanne (in note#26 p573 of A thousand plateaus, 2005).

6 Mosely's doctoral study (2014) is devoted to artists' books and the haptic. See page 26 and particularly pages 76-77 where an 'insoluble tension within the idea of smooth space' is discussed.

7 In The look of love (2001) Kelly Oliver develops Luce Irigaray's ideas on light and air to suggest an alternative notion of space. Oliver (2001:66) argues that '[r]ather than reduce vision to touch ... Irigaray emphasizes the touch of light on the eye. For Irigaray, it is not, then, that vision and touch are not separate senses; but rather that vision is dependent upon the sense of touch'. Oliver (2001:70) continues: 'In suggesting that sight is a sensuous caress, Irigaray follows Merleau-Ponty and Levinas. From Merleau-Ponty, Irigaray develops her notion of a tactile look and the connection between vision and touch. From Levinas, Irigaray develops her notion of the look as a caress'.

8 This idea is reminiscent of Willem Boshoff's Blind Alphabet Series in which only the blind are given privileged access to the hidden sculptural works, their brail explications, and the series' meanings. Elsewhere (Paton 1996:14), I have stated about this series that '[w]e may, however, see with our fingers and begin to perceive with our skin and thus gain access as touch-enriched and haptic individuals'.

9 This tension between viewing a video and the haptic manipulation of a book along with questions of disembodiment and proximity in these experiences was the subject of my published article titled 'Body, Light, Interaction, Sound: A critical reading of a recent installation of Willem Boshoff's Kykafrikaans' (2008).

10 Deleuze and Guattari (2005:7) refer to books as 'collective assemblages of enunciation'.

References

Bakhtin, M. 1982 [1975]. Discourse in the novel, in The dialogic imagination: Four essays by M. M. Bakhtin, edited by M Holquist, translated by C Emerson and M Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press:259-422. [ Links ]

Barthes. R. 1977. Image-music-text, translated by S Heath. London: Fontana. [ Links ]

Besley, T & Peters, M. 2011. Intercultural understanding, ethnocentrism and western forms of dialogue. Analysis and Metaphysics 10:81-100. [ Links ]

Bodman, S. 2019. 'What if?' books, in Correlations between independent publishing & artists book practice. Southbank: Queensland College of Art, Griffith University:2-10. [ Links ]

Carrera, J. 2005. Diagramming the book arts. The Bonefolder 2(1):7-9. [ Links ]

Colebrook, C. 2009. Derrida, Deleuze and haptic aesthetics. Derrida Today 2:22-43. [ Links ]

Cooper, A. 2014. The E-dge of the book. The Blue Notebook Journal for Artists' Books 9(2):47-53. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G & Guattari, F. 2005. A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Derrida, J. 2001. Jacques Derrida deconstruction engaged. The Sydney seminars. Sydney: Power Publications. [ Links ]

Dietrich, K. 2011. Intersections, boundaries and passages: Transgressing the codex. Professorial Inaugural Address. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. [O]. Available: http://www.theartistsbook.org.za/view.asp?ItemID=10&tname=tblComponent2&oname=&pg=research&app=&flt=other Accessed October 2011. [ Links ]

Dietrich, K. 2017. Between the folds: The struggle between images and texts with reference to selected artists' books, in Booknesses: Artists' books from the Jack Ginsberg Collection, edited by R Sassen. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg:62-75. [ Links ]

Drucker. J. 1995. The century of artists' books. New York: Granary Books. [ Links ]

Drucker, J. 2005a. Critical issues / exemplary works. The Bonefolder 1(2):3-15. [ Links ]

Drucker, J. 2005b. Beyond velveeta. The Bonefolder 2(1):10-11. [ Links ]

Frost, G. 2005. Reading by hand: The haptic evaluation of artists' books. The Bonefolder 2(1):3-6. [ Links ]

Garfinkel, H. 1967. Studies in ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Haskins, P. 2013. Experiencing artists' books: Haptics and intimate discovery in the work of Estelle Liebenberg-Barkhuizen and Cheryl Penn. MA dissertation, University of Kwazulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Holquist, M (ed). 1981. The dialogic imagination: Four essays by M.M. Bakhtin, translated by C Emerson and M Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Holquist, M. 2002. Dialogism. Bakhtin and his world. Routledge: London. [ Links ]

Kristeva, J. 1980. Desire in language: A semiotic approach to literature and art, edited by L Roudiez, translated by T Gora and A Jardine. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Kromann, TH. 2014. Booktrekking through the golden age of artists' books - and beyond. Journal of Artists' Books 35:15-18. [ Links ]

Lauwrens, J. 2019. Seeing touch and touching sight: A reflection on the tactility of vision. The Senses and Society 14(3):297-312. [ Links ]

Liebenberg-Barkhuizen, E. 2009. Artists' books: A postmodern perspective. South African Journal of Art History 24(2):65-73. [ Links ]

Lyons, J. (ed). 1985. Artists' books: A critical anthology and sourcebook. Rochester: Visual Studies Workshop. [ Links ]

Marks, L. 2002. Touch. Sensuous theory and multisensory media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Mosely, T. 2012. The book of laughing and crying. The Blue Notebook Journal for Artists' Books 6(2):37-42. [ Links ]

Mosely, T. 2014. The haptic touch of books by artists. Doctoral thesis. Queensland College of Art, Griffith University, Brisbane. [ Links ]

Mosely, T. 2016. The haptic and the emerging critical discourse on artists books. Journal of Artists' Books 39:36-39. [ Links ]

Oliver, K. 2001. The look of love. Hypatia 16(3):56-78. [ Links ]

Paterson, M. 2007. The senses of touch: Haptics, affects and technologies. London and New York: Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

Paton, D. 1996. Transpositionalism in selected works of Willem Boshoff, in Willem Boshoff Blind Alphabet C Cocculiferous to Cymbiform. 23rd Sao Paolo Biennial. Johannesburg: Africus Institute of Contemporary Art:10-15. [ Links ]

Paton, D. 2008. Body, Light, interaction, sound: A critical reading of a recent installation of Willem Boshoff's Kykafrikaans. Image & Text 14:114-131. [ Links ]

Paton, D. 2012. Towards a theoretical underpinning of the book arts: Applying Bakhtin's dialogism and heteroglossia to selected examples of the artist's book. Literator 33(1):24-34. [ Links ]

Patton, P & Smith, T (eds). 2001. Jacques Derrida deconstruction engaged. The Sydney seminars. Sydney: Power Publications. [ Links ]

Pórtela, M. 2011. Embodying bookness: Reading as material act. Journal of Artists' Books 30:7-13. [ Links ]

Prytherch, D. 2002. Weber, Katz and beyond: An introduction to psychological studies of touch and the implications for an understanding of artists' making and thinking processes. Research Issues in Art Design and Media 2:1-9. [ Links ]

Sassen, R. 2004. A ball of light in the hand. Art southafrica 3(1):44-49. [ Links ]

Sassen, R. 2008. Under covers: South Africa's apartheid army - An incubator for artists' books. The Blue Notebook Journal for Artists' Books 3(1):6-16. [ Links ]

Sassen, R (ed). 2017. Booknesses: Artists' books from the Jack Ginsberg Collection. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Schouwenberg, L. 2017. Innovation as premise of art and design education, in Material Utopias. Amsterdam: Sandberg Institute:17-46. [ Links ]

Silverberg, R. 2017. The Aegean Sea: The compulsion to make artist books. Proceedings of Booknesses: Taking stock of the book arts in South Africa. A Colloquium organised by the Department of Visual Art, University of Johannesburg, South Africa:18-36. [O]. Available: http://www.theartistsbook.org.za/booknesses/downloads/booknesses_colloquium_prodeedings.pdf Accessed 20 April 2022. [ Links ]

Skotnes, P. 2009. A columbarium of words and a mode of locution, in On making: Integrating approaches to practice-led research in art and design. Johannesburg: Research Centre, Visual Identities in Art and Design, University of Johannesburg:247-262. [ Links ]

Skotnes, P. 2017. Axage Private Press and the book in the cave, in Booknesses: Artists' books from the Jack Ginsberg Collection, edited by R Sassen. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg:76-87. [ Links ]

Smith, P. 1996. The whatness of bookness, or what is a book. [O]. Available: http://www.philobiblon.com/whatisabook.shtml Accessed January 2008. [ Links ]

Spindler, F. 2010. Gilles Deleuze: A philosophy of immanence. [O]. Available: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:406664/FULLTEXT01.pdf Accessed 20 March 2019. [ Links ]

Van Capelleveen, P. 2022. Book arts in the twenty-first century. A (re)view, in Materialia lumina. Contemporary artists' books from the Codex International Book Fair. Stanford: Stanford Libraries and the Codex Foundation:21-62. [ Links ]

Wolfendale, P. 2009. The plane of immanence in deontologistics. [O]. Available: https://deontologistics.wordpress.com/2009/10/02/the-plane-of-immanence/ Accessed 20 March 2019. [ Links ]