Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a25

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

embodied-enTAnglements/ enTAngled-embodiments performaTI Ve encounters with materials, creative process, and the artist-woman's body

Bev Butkow

Department of Fine Arts, Wits School of Arts, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. bevbutkow@gmail.com (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4787-4122)

ABSTRACT

This article explores the changing role of the audience within aesthetic encounters. It is framed within a shift in the nature of these encounters away from the primacy of vision, and towards experiential encounters within the body of the audience. I approach the article as self-reflexive autoethnography, assuming dual roles: in the first place as maker, and then describing my heightened bodily response as audience or experiencer to an immersive constellatioN of forms I made. In the next section, I unpack how experiential aesthetic encounters of this type unseTTle and disorientate traditional understandings of material forms and aesthetic relationships. Meaning is no longer situated within visual representation, but is made rather in situ and in actu within the subjective embodied experience of the experiencer who becomes part of the artwork. The final section recognises the porosity of boundaries between the subject and object, observer and observed, and artist and audience through exploration of the enTAngled relationship between the experiencer, my creative labour as the maker, and the vitalised materials that constitute my constellatioN.

I conclude by showing how creative proceSSes have unique power to mobilise experiential materiality in a way that establishes an embodied coNNection within the body of the receptive experiencer. This embodied coNNection enables a reorientation from head-based intellectual analysis, Cartesian binaries and focus on visual representation. By activating the whole-body of the experiencer and the embodied coNNection between audience-maker-artform, possibilities are generated for expanding and deepening interhuman relations, thereby signalling a return to forms of knowledge produced from and by the body.

Keywords: material, enTAngle, embodiment, creative proceSS, artist-woman body, performaTIVe encounters.

Introduction

My intention in this text

How does an artist experience her creations when viewing them removed from her all-consuming studio-based making proceSSes? This text deals with my immersion in a constellatioN of forms, titled embodied-enTAnglements/enTAngled-embodiments (eXe), that I assembled in November 2021 at the Origins Centre Museum, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Here I explore how that immersive aesthetic encounter elicited a bodily response within me and a heightened bodily awareness for myself (Bishop 2005:56), and perhaps for many others who experienced the installation. Immersive art installations are designed to intensify awareness of the arrangement of artworks in space, and the viewer's bodily responses to this arrangement (Bishop 2005:6). The viewer's first-hand experience is essential: by presenting elements to be experienced somatically, such as texture, light and space, the viewing subject is "activated", often through a multisensory experience that stimulates the senses, like sight, hearing, touch, smell, taste, and proprioception. The viewing subject is simultaneously 'decentred' as focus shifts away from the artwork's interior elements towards a more public and shared space (Bishop 2005:6).

In this text, I inhabit the roles both of artist and participant, acknowledging the enTAngled relationship between participant-artist-art form that is central to the arguments presented in this article and to the occurrences that I experienced within the exhibition space. Since my own and others' engagement with the installation - or what I refer to as a constellatioN - exceeded the visual act of looking, invoking a whole-body activation, I have replaced the commonly used appellation of a 'viewer' with the term 'experiencer' to denote the work's audience (Lacy 1995:173-175; Jones 2015:22). "Experiencer" foregrounds the fundamentally interactive and reciprocal nature of experiencing, as well as the subjective nature of the responses, intuitions and perceptions generated. When the artist takes on the role as experiencer, however, her roles, responsibilities, and relationships with and to her work's audience change, as she becomes 'a conduit for the experience of others', and must employ 'intuitive, receptive, experiential, and observational' skills on their behalf (Lacy 1995:174).

My materialist approach takes guidance from Amelia Jones (2015) and Marsha Meskimmon (2019), who recognise that 'co-constituting' possibilities (Haraway 2004:84) exist at the intersection of making, vital new materialisms, and corporeal feminisms. These theories frame this text. I rely on enTAngling of creative practices-materials-performaTIVe encounters to provoke thinking in exPAnded ways about subjects and objects.

I also bring deliberate visual activations to this text that challenge literary academic prescriptions. My creative approach here varies text alignment and justification, inserting instances of visual poetry and using overt and inconsistent case formatting and capitalisation to disrupt how one encounters the text. I gather together and entangle words that I feel resonate closely with my creative proceSS, to invoke an embodied response in the reader. Enlivening words as poetics rather than prose encourages variable interpretations. Creative and theoretical modes feed off each other, providing varying lenses through which to engage with my constellatioN and with this text.

Framing myself

Because the constellatioN is so linked to me in its making and output, I have used a self-reflexive autoethnographic approach to consider the different artist-experiencer roles I take on. A number of feminist theorists have demonstrated that self-reflexive autoethnography has relevance beyond subjective personal stories because individual women are intimately and inextricably enTANgled with the greater narrative of the collective. 'Autotheory' translates established bodies of theory and philosophy through an encounter with first-person narrative and embodied experiences (Fournier 2021). Writers like Audre Lorde (2007) and Saidiya Hartman (2008) demonstrate how subjective storytelling and experiences are able to challenge established proceSSes of knowledge production to deepen human and theoretical understandings.

Embodiment is both a social construct and a theoretical position concerning the subjective experiences of human lives through their phenomenal bodies - and the subject of intense theoretical debate. Joan Copjec (1996:25) distinguishes two ways that cultural analysts tend to frame embodiment: namely, the material corporeal self on the one hand, is distinguished from the embodiment of social identity on the other, which can be viewed as a signifier that imposes social order. As a corporeal feminist, Elizabeth Grosz (1994:210) describes an intertwined relationship between these seemingly opposing concepts, seeing the subject as 'becoming' in the fluid intercoNNected interaction between interior factors and external forces. She envisages embodiment through a Möbius strip, which rotates through its different yet interchangeable surfaces, retaining differences while producing an effect of unity in three-dimensional space (Grosz 1994:210).

Intimate acts of weaving and painting, which function as my mode of self-theorising, enable me to access my embodied experiences. My making is situated in the specificities and uniqueness of my accumulation of experiences and embodied sense of things in the world, and the social, material and political conditions within which I live (Haraway 1988:583). It is embedded within a confluence of my worldliness, personal perspectives, perceptions and memory associations - all components of what Maurice Merleau-Ponty (2012) has described as comprising the phenomenological body. Merleau-Ponty's theory of perception has a strong influence on immersive installation art (Bishop 2005:48).

I refer to myself through Griselda Pollock's (2020:xxiv) term 'artist-woman' here, both to assert my agency and to sidestep the flattening of women artists' representations based on their identity markers and 'sentimental biographic accounts' (Pollock 2020:xxv). As Pollock (2010:54) notes, the category 'artist' has historically been 'symbolically reserved for men':

once you qualify the word artist...with any adjectival noun such as woman or black, the artist in question is immediately disqualified. They become different, other, supplementary, defined by ethnicity or gender (Pollock 2020:xxv).

How this text unfolds

The text unfolds through the armatures of three warp strands. The first warp is referred to as unseTTling space, which describes my experience of the performaTIVe constellatioN and the activations I set in place to enhance its immersive and experiential qualities. The second warp, Boundaries that become porous disorients accepted logics of aesthetic viewing to give rise to new possible formulations of enTAngled objecthood and subjecthood. Finally, Coexisting considers the entangling of materials, bodies and creative proceSSes.

1. THE CONSTELLATION AND MY EXPERIENCE OF IT

exPAnded forms take flight

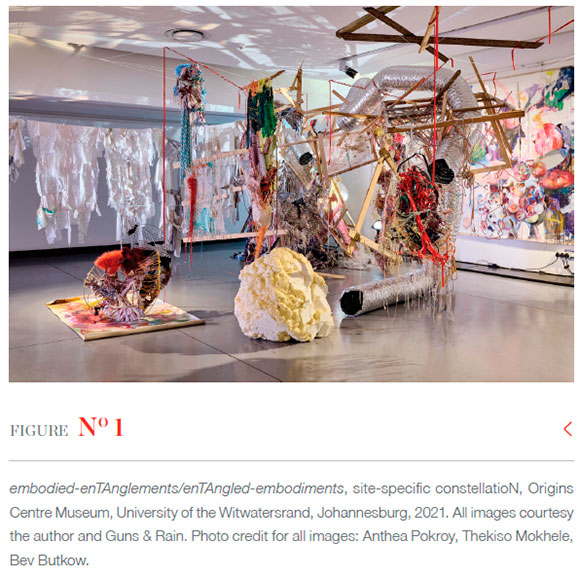

As I describe my experience of the exhibition, I recognise that my extended artistic journey with these materials and ideas may influence my responses and reactions to the experience. My installation was exhibited in a darkened room, so that a viewer would be confronted with the literal explosion of chaotic, seemingly haphazard forms that were montaged into the physical space of the Origins Centre, Johannesburg (Figure 1), metaphorically transforming it into a giant, dynamic loom. A messiness emanated from a vertiginous 'tower' (Figure 2) in the far corner of the room, which was constructed from broken wooden frames and compacted densely with weaves and dressmaking scraps. The tower appeared to explode sculptural textile forms, paintings and material out of itself, spilling bits randomly onto the floor and into space.

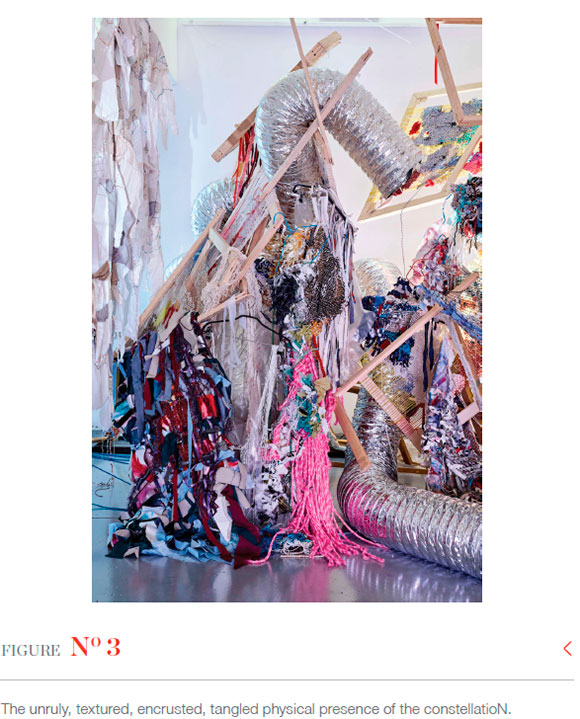

I intended for viewers to be enveloped by the unruly profusion of material presence shown in Figure 3 as they wandered through the constellatioN. Around forty woven, tumultuous, densely overworked, heavily laden, amorphous, dimensional free forms juxtaposed more threadbare ones. Threads criss-crossed haphazardly with endings left dangling. Strewn around were textile offcuts, strings of beads, tangles of plastic and unravelling coloured yarns. Forms spilled out from broken pieces of wooden frames; thick silver air-conditioning ducting wove in and out of the mass like exaggerated thread. Its material intensity felt "otherworldly", holding peculiar resonances that "spoke" to me on multiple associative levels.

The unruly, textured, encrusted, tangled physical presence of the constellatioN.

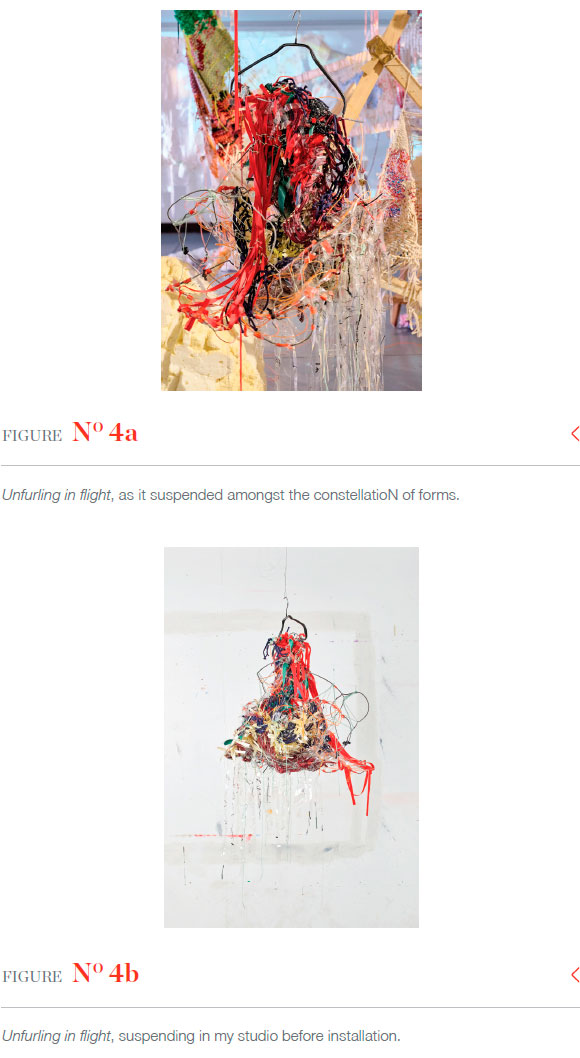

The space held a wide array of making techniques, from weaving, soft sculpture, painting and welding, to video, a sonic piece, and exaggerated light and shadows. Navigating carefully through the constellatioN, Unfurling in flight (Figure 4) came into view. It hung on a clothes hanger suspended from a thread of fishing gut as it rotated gently into a dynamic ever-changing manifestation of itself. Dishevelled and trailing threads of reflective plastic sheeting, its dimensional form bent inwards, and seemed to protect a delicate nesting of beads within its core. Its shape was formed with galvanised wire, which was knotted and woven with multicoloured threads, tatters of cloth and an accent of red ribbon.

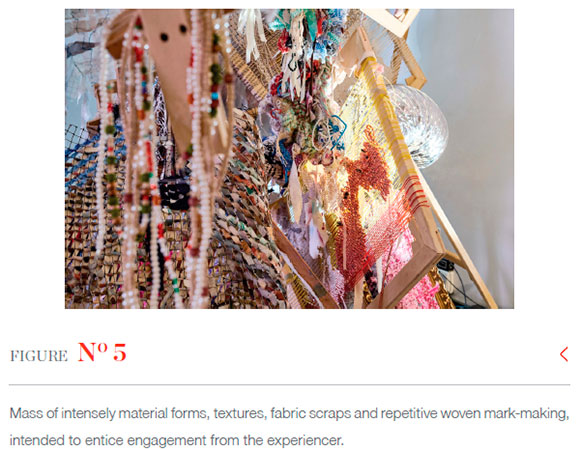

I had intended for the viewer to be immersed in an Excessive Obsessive Accumulation of Consumption (Figure 5). Tiny beads built up into this monumental corpus. The sheer number of beads! The mass of materials was juxtaposed with the regularity of woven marks that pervaded the space with a sense of ritualistic repetition and patterning. Weaving is a repetitive re-enactment of labour: beyond technique, beyond materials, weaving consumes labour. This constellatioN grew out of and through these creative acts and my nurturing. The labour and time I invested in its making transformed it into a complicated sculptural mass that exPAnded dimensionally into space.

Forms resisted being tied down, appearing to defy gravity as they hovered, suspended unstably from a lattice of flimsy, sParKly fishing gut, catching the light as they twirled, seeming to take over space; invade it. Claiming space.

Liberated and unbounded, they appeared to manifest an aliveness.

Moving through the forms and the space - as an active participant rather than a passive viewer - the complex montage of forms in space provided multiple viewing perspectives and perceptions. As I meandered through an interplay between surface and depth, forms oscillated between two and three dimensions, never completely solidifying or resolving their full nature.

The constellatioN pulled in fragile equilibrium between holding together and unravelling. It exploded in disorder and simultaneously constellated to find order.

An 'anxiety' (Jones 2015:25) of tensions pervaded it - chaos/order, ephemeral fragility/solid material, harmonious paTTerning/disruption. These energetic contradictions unseTTled and animated the constellatioN, making the assembled forms dynamic in space.

Multifaceted; multidimensional.

An experiential immersion: An invitation to touch

Through permission conveyed via a wall text, experiencers were invited to touch, engage with, and tangibly experience the constellatioN:

I invite you to experience this space with a childlike curiosity.

Immerse yourself in the tactile sensory dimensions of my uprising of textures, colours and materials.

Perceive a bodily coNNection that occurs beneath the radar of language and rational thought.

I enTAngle material, personal and social metaphors. In this place of alchemy, things and ideas are a performance that brings to life my creative labours. My nurturing of enTAngled forms manifests an aliveness that exPAnds into the world-flows. Space is unseTTled as constellatioNs dissolve and then solidify again.

I want to challenge the logic of how we make sense of the world. I elevate the intuitive perceptive body as the primary source of human intelligence. Human coNNection, full of raw emotion and dazzling compleXity, becomes possible. Creative proceSS is mobilised to un-discipline, de-discipline and destabilise.

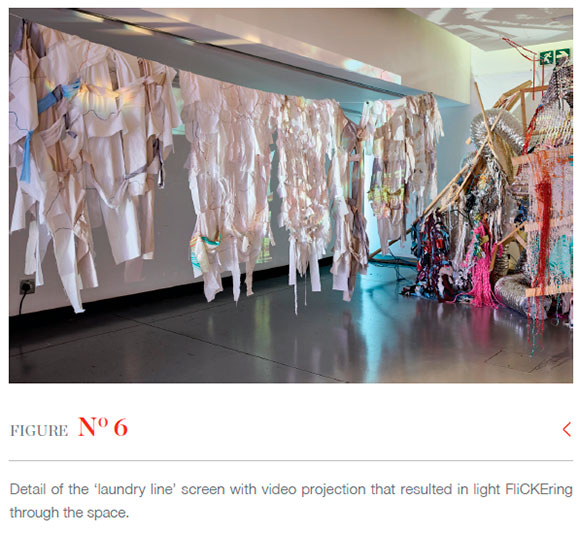

I employed deliberate strategies to activate the exhibition space with the movement of people, sound and light through the constellatioN's multisensory and experiential qualities. Darkness gave a sensory immediacy, heightening the senses other than vision. The air was filled with aromatic fragrances. Cushions placed within the constellatioN encouraged audiences to move freely through its forms and sit among them. Once physically immersed within, the sense of proximity to the variety of textures encouraged touching. Experiencers even moved threads and forms around, so that the constellatioN shifted and took new forms throughout the exhibition period, accentuating its impermanence. The tiniest actions animated the mass of forms to shift in response, emphasising its dynamic nature. gliMMerIng light and daPPled shadows brought further movement and liveliness into the space. Video projection fliCKEred light through a "laundry line" of loosely-woven and porous white weaves (Figure 6), while an accompanying sonic piece reverberated deep sound. A play of light captured elongated shadows that merged with the forms, accentuating textures and dimensionality. shiMMering, sPEckLed light caught the surfaces and pixellation of beads, glitter, plastic, sequins and other reflective materials, which gLinTed bodily - like visceral flesh - as they

caught the light, held the light, moved into the limelight

held the light, caught the light, moved into the limelight

The exhibition space deliberately acted as a critique of the white cube space, functioning beyond its conventional state of quietude in which viewing occurs at a distance with viewers discouraged from touching or engaging directly with the artforms.1 Multiple stimuli were used in such a way that they might engulf the whole body of the experiencer in an immersive multisensory experience, activating sight, hearing, touch, smell and proprioception, to render the experience personal and unique.

Activations

I amplified the interactive and collaborative space through a series of activations by like-minded fellow creatives whom I invited to circulate ideas, experiences and relationships in the space. Oupa Sibeko enTAngled himself into and among the constellatioN, foregrounding the movements of his physical body through the brutal honesty and authenticity of his durational performance. Wendy Leppard's 'Crystal Alchemy Singing Bowls' filled the space - and potentially the depths of an experiencer's body - with reverberating sound sensations that they might experience as a mode of healing, liberation and renewal. Niki Seberini's 'mind-decluttering' talk encouraged those present to consider how we knot and enTAngle ourselves into stories that can grow to take on lives of their own, and thereby shape our own lives. She offered how we can weave new realities by untangling our stories. Finally, Shanti Govender's breathwork meditation heightened each of my own senses, and potentially other participants' too, through a full body experience.

2. UNSETTLING SPACE

something unexpected

happened in the exhibition space...

yet,

it felt totally intuitive

Sitting in a gap

in the middle of my constellatioN, immersing and submerging

myself within forms, spiralling weaves and swirling beads in countless shapes,

colours, textures, reflections and particles, a calmness took hold of me.

Engrossed in the sedimented forms I had conjured, gazing up, watching the lights gLinT on the wooden frames,

particles WinKing gliMMerIng glIsteNIng sParKLIng fliCKEriNG shiMMering

moVing

reverberating sound

the gentle undulations of movement transported me into another world.

There was a moment

when time collapsed in on itself

waves of powerful multidimensional exPAnsive informational fields I was in all time, past, present and future

space, time and place experienced simultaneously

like I was in some kind of Energy Chamber

My space was a Sanctuary. A place to recoNNect with deep layers of myself.

To release.

Others called it 'a Womb'.

Meditating within the Womb, I was overcome with tears, feeling a coNNection to the soul of a baby who had recently miscarried. At that precise moment, a friend nestled alongside me and told me of her two miscarried babies, whom she had never discussed before, releasing a 28-year-old wounding. A videographer I had hired similarly used my 'healing space' as catharsis, speaking publicly for the first time, she said, of her experiences with depression and multiple suicide attempts.

Things happened within the 'other-worldliness' of my exhibition space that I cannot explain. I experienced it as being immersed in auras, intensities and energies at play.

For inexplicable reasons, I felt that the space of my exhibition held a coNNection to something ethereal. There was a presence in the in-between spaces.

Something healing

that held onto past labours and memories

and that transcended anything that I was capable of creating.

A space of magic?

PerformaTIVe art forms

The experiential, phenomenological encounter exceeded the form and ontology of its making. The constellatioN rather revealed some kind of innate 'vitality' or liveliness (Bennett 2010:117), which exhibited an independent ability to influence my actions (Jones 2015:28). It was this performaTIVe power that enticed my hands to touch the surfaces, to feel and experience their textures and encrusted forms. Dorothea von Hantelmann (2014:[Sp]) explains that performaTIVe art forms of this nature move beyond representation of images to the effects and experiences that they produce: from what they 'depict' or 'say', to what they 'do'. They 'shape experiences', which then become integral to the art form, functioning to establish 'experimental relationships' that are located in a 'given spatial and discursive context' (von Hantelmann 2014:[Sp]). Locating the prevalence of performaTIVe art forms in the contemporary environment, von Hantelmann (2014:[Sp]) traces 'art's transition from an aesthetic of the object to an aesthetic of experience', to its context within affluent post-industrial Western societies whose social order has shifted 'from supply-driven to demand-driven markets' and 'from producing things to selecting them' (von Hantelmann 2014:[Sp]). The individual subject, she argues, becomes foregrounded through these shifts, which coNNect the production of meaning to their 'situated and embodied experience' (von Hantelmann 2014:[Sp]).

3. BOUNDARIES BECOME POROUS

While I cannot explain the energetic or spiritual elements that I felt to be at play within my exhibition space, I believe that creative activities can enliven and 'activate' aesthetic objects to engage experientially with the bodily situatedness of the viewer. When Meskimmon (2019:358) says that 'aesthetics and art-making are especially significant...because they mobilise materiality, the senses and response-ability', she recognises how activities and proceSSes of art making enTAngle and mobilise the materialities of things (materials and artworks) as well as embodied, situated humans thereby activating them both. This responsiveness encompasses both an ability to respond, and an ethical responsibility, and is critical to formulating new ways of engaging subjecthood and objecthood. Creative practices are able to mobilise and ignite responsiveness through 'experimental, exploratory', embodied and sensorial registers (Nuttall 2009:152), which intersect to shape aesthetic experiences with the intention of 'producing new spaces of meaning' (Jones 2015:21).

Embodied encounters (and experiences that go beyond the visual) disorientate the accepted logic of aesthetic viewing and cannot be explained by traditional art-historical analysis, which is based on representation that primarily attempts to replicate or translate what a viewer sees. Linear perspectives have long resulted in flattened binary representations of the body, while subject-object hierarchies assert (specifically) man's mastery over the world, and 'deaden' materials. Drawing on Martin Heidegger (1977:144), Barbara Bolt (2004:19) argues that Cartesian representation through mimetic forms, such as painting, provides an organisational system of fixed thought patterns that reduces the world to a projection, modelling or framing. In 're-presenting' the world, "man" is placed at the centre of all relations, asserting his dominance as he conquers the world as picture (Bolt 2004:20,25). He thereby creates both 'fixity...and...mastery over the world' (Bolt 2004:9). Linear representation risks a one-dimensional flattening or fixing in space and time of its subject, that overlooks the partial perspectives through which we actually come to frame our views of the world.2

The performaTIVe power of art is enabled through a provocative realignment of historical logics like Cartesian dualism, binaries and fixities upon which we have traditionally framed our sense of the world. Theoretical developments in feminism, (neo)materialisms, (post)phenomenology, creative research and decolonial studies, inter alia, disrupt such binaries and fixities. Considered from these alternative perspectives, matter may be understood instead as being 'vibrant', 'alive' and 'vital' (Bennett 2010:117; Ingold 2007,2010). The human body might thus be reconceived as enTANgled matter, open to being impacted by all aspects of the world it overlaps with, such that relationships between humans and non-humans become reciprocal and non-hierarchical. Beyond representation and fixity, understanding may move towards more complex, mutable and enTANgled depths.

A new mode of analysis for performaTIVe aesthetic encounters

Amelia Jones (2015) proposes varied 'levels of interpretive engagement' (Jones 2015:22) that may be drawn upon in a hybrid approach to understand 'new complex art experiences that are performaTIVe yet exist in various material forms (including, arguably, that of the artist's labouring body)' (Jones 2015:20). Her hybrid approach incorporates a combination of:

art history (attention to form and materiality)

performance theory's focus on ephemeral processes and the

'authenticity' of the performing body

the liveliness and material agency offered by new materialisms

aspects of Marxist labour theories.

My constellatioN was a complex hybrid intersection of varied threads. The experiential encounter in relation to the constellatioN arose, I believe, out of a confluence of elements - including my created forms accompanied by the fliCKEriNG lights and sonic piece; the activations that were part of the exhibition; my complex personhood and life experiences, embedded as traces within my artmaking; and the energy of the Origins Centre Museum itself, with its sedimented history and the spirits of its resident ancestors that permeate its archival drawers of historical bones and rock engravings.

Likewise, the forms that emerge from my making proceSSes, which I call embodied-enTAnglements/enTAngled-embodiments (eXe), are best understood as enTAnglings that hold ephemeral traces of:

Lingering residues of

my intense performance of making.

My philosophy of thinking, making and knowing.

My studio at the Bag Factory Artist Studios in Newtown,

Johannesburg with its immersive sounds, smells and textures ofcreativity.

My context as a mature student at Wits University within creative

practice in South Africa in 2022.

A combination of weaving, painting, sculpture and installation.

My subjective life experiences, and those of the people who

weave with me.

My journey to recover the vitality of mundane everyday

consumer materials; along with the histories and

memory associations they evoke.

Activated bodies of the experiencers, and the

gestures of my artist-woman body.

Possibilities arise for "other" worlds of knowing when boundaries between humans and non-humans become porous.

There is more to it.

4. COEXISTING

I argue that emotive or auratic visceral aesthetic encounters of this nature have value in how they unseTTle and disorientate traditional understandings of material forms and aesthetic relationships. My presence in the exhibition space activated and animated the constellatioN: I became an enTAngled part as my involvement 'completed' it (Bishop 2005:11). As a result of the 'performative turn' (Fischer-Lichte 2008:8), the engagement with art forms has been transformed into an experiential event (rather than a viewing) in which the audience becomes part of the art form, with no distinction remaining between 'subject and object, observer and observed and artist and audience' (Fischer-Lichte 2008:23).

I now contemplate these enTAngled relationships: namely, that of the subjective position of the experiencer, the enlivened materials that constitute my constellatioN, and my creative labour as the maker.

The subjective position of the experiencer

As I inhabited the 'otherness' of the constellatioN, a sensory overload was ignited in my experiencer-body: that 'sensory immediacy' activated an affective bodily response (Jones 2015:20). These profound haptic experiences were reliant on multiple bodily intelligences, through my senses of sight, hearing, smell, movement and proprioception (Bishop 2005:11). This generated what I encountered as a whole-body experience, akin to the immersive multidimensional and multisensory experience of theatre or performance: I 'experienced' the vibrational liveliness of activated colour, movement, rhythm, texture, space and light, rather than saw them 'represented' (Jones 2015:20).

The constellatioN was alive with possibilities for me as a receptive experiencer, depending on the level of engagement and state of mind I brought to it. It required me to slow down so that the more time I spent with it, the closer I looked, and the more it revealed. The constellatioN drew me in at an intuitive, perceptive level through the phenomenological effects it elicited within my body (Jones 2015:33). I was invited into intimate, personal and bodily experiential moments, and felt able to interpret them based on my perceptions. My embodied engagement was both subjective and partial. I engaged from my own perspectives and life experiences, making meaning of the encounter through my 'situated and embodied experience' (von Hantelmann 2014:[Sa]), and I came to make sense of the encounter through my subjective experience of it. My embodied subjecthood was activated so that my perceptions and perspectives become enTAngled within my experience of the constellatioN. Because perception involves the whole body rather than merely the eyes (Bishop 2005:50), the embodied experience opened up my body to absorbing new experiences and ways of being and thinking in the world.

Beyond being seen, eXe, critically, is felt.

The 'experiential dimension of image encounters' overturns the more conventional visual experience of contemplating a single art form via the eyes alone (Lauwrens 2019:300). This shift from viewing to experiencing upends the primacy of vision to open possibilities for alternate approaches around the production and reception of art forms. Experiential aesthetic encounters envisage a shift of knowledge from being situated within the experiencer's position, conditions and experiences (Haraway 1988) to the encounter of knowledge as experiential, embodied, and made in situ (on site, or in position) and in actu (in the very act) (Vesters 2016:1).

Liberating the intensity of immaterial materials

Materials are able to elicit an embodied response that is experienced rather than seen through the revitalised 'vibrancy' of matter (Bennet 2010). Vibrant objecthood reformulates the notion of 'objectness' beyond the physical form of passive fixed objects, to understand them instead as enTAngled, ethereal and amorphous vital matter, comprising the power of forces, intensities, energies, powers and auras at play. As such, my constellatioN as a whole became an embodied form that functioned as an active participant in the encounter. As von Hantelmann (2014:[Sp]) explains, 'The object, traditionally the protagonist of meaning production, becomes a device for engaging in an experimental relation with oneself and others', and plays a crucial role in the enTAngled relationship with both the experiencer and maker.

A historical legacy frames our thinking around objects and materials. Tim Ingold (2010:93) explains that the "aliveness" of objects/things was deadened in Western making practices during the fifteenth century, when the "genius" artist (read white, Western male) is recognised for his ability to impose 'preconceived form' and exert 'rational and rule-governed' control over materials. In a world that could then be 'engineered in the light of reason' (Ingold 2010:93), the reciprocal relationship between artist and 'active' materials (Ingold 2010:117) became estranged. Materials became "other" - subsumed as 'inert substance' available for man's use and intellectual prowess (Ingold 2010:117). They became mere Objects to men, who took the foreground as Subjects (Ingold 2010:117).

It is only under theoretical reorientations that deprivilege human exceptionalism and agency 'as the source of all meaningful expression or action in the world' (Jones 2015:25) that matter can be repositioned from passive, homogenous substance, available for humans to impose actions, thoughts and interpretations upon (Barad 2003:821). For this to happen, as humans, we need to shift our sense of hierarchical superiority to recognise that we inhabit the planet on the same hierarchical level as all things and life.

The agency or liveliness of material forms can be contentious, however: to pass my 17-year-old son's "rationality" test and avoid dinnertime arguments, I do not attribute "life" to my constellatioN; it is inanimate. Nor do I want to imply humanlike agency, or impose human emotions or qualities onto it. For Ingold (2010:94), things are caught up in the constant state of motion around the lines of coNNection, flows and activities of the world. Objects, he argues, 'are active not because they are imbued with agency but because of ways in which they are caught up in these currents of the lifeworld' (Ingold 2007:15).

Once activated, the intense, tactile and immersive physicality of materials can evoke haptic bodily experiences within the experiencer's body, as Deleuze (1981:34-43) shows through Francis Bacon's paintings. He describes how the physical material of oil paint can convey sensation and affect, evoking haptic vision in a way that detaches from the represented image. Laura Marks (2000:163) similarly describes how eye movement slows as it moves over the surface to discern texture, so that viewing becomes 'more inclined to graze than to gaze', and thereby develops a sensory perceptive relationship with the art form. Haptic vision of this nature is associated with embodiment and experiential materiality, in contrast to the optic, which concerns figurative representation, linear perspectives and disembodied vision (Richards 2005:15). 'Haptic visuality muddies intersubjective boundaries' (Marks 2000:163), enabling an entangling of the experiencer and the art form.

Meskimmon (2019:361) highlights the importance of art making to mobilise experiential materiality. Things come into being by intervening in the currents and force fields of materials themselves, which are in a state of constant flow - 'in movement, in flux, in variation' (Deleuze & Guattari 2004:451). Rather than creating forms, the artist merely intervenes in the force fields to redirect their flows in 'anticipation of what might emerge' (Ingold 2010:94). Artist and weaver, Anni Albers (1982:[Sp]), speaks of a suggestiveness with which her materials lead her making proceSS. She describes her open receptivity and reciprocal relationship with materials, proposing that 'the more subtly we are tuned to our medium, the more inventive our actions will become' (Albers 1982:[Sp]). This is because 'material is a means of communication...The finer tuned we are to it, the closer we come to art' (Albers 1982:11).

I immerse deeply in the intensities and specifics of my materials because, as Ingold (2007:1) suggests, describing 'the physical properties of materials means telling their stories'. I work with my materials by hand in a proceSS of individuation, sensitively exploring them through focused one-on-one attention and "listening" deeply to find their singularity. I resist the desire to impose dominance over them, instead working with them as an enTANgling of equals. My everyday materials function within my proceSS as co-creators: as active, rather than passive, participants. Their intrinsic material properties guide the creative proceSS in an openly receptive and symbiotic relationship.

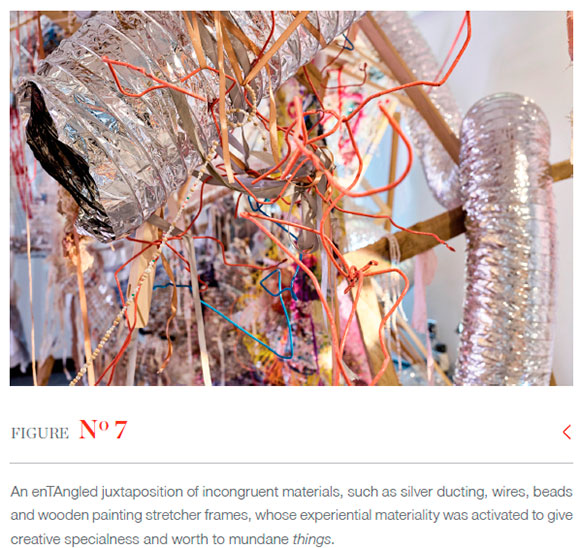

Immersing in materials in this way allows me to be open to consider the enTAnglement of people and material culture. As Petra Lange-Berndt (2015:15,16) reminds us, 'to act with material and to be complicit means to investigate societal power relations'. Objects lend their multiple uses, associative readings, histories and interpretations to my surfaces; and through them, the experiencer registers memories which act as 'spur[s] to "perceptions, feelings and thoughts" as well as connections with existing cultural meanings' (Pollock 2011:[Sp]). My constellatioN celebrates the small, ordinary, and habitual: I unseTTle the manufactured materials that give shape to our human lives and without which we would be massively inconvenienced. My use of the everyday is consciously defiant. I nurture these materials in wandering (and wondering), questioning, embattling, loving and motherly acts to activate and liberate their innate potential into the world-flows. Figure 7 shows how this brings the specialness of art to ordinary objects: the extraordinary is woven from the mundane, commonplace and unnoticed.

The constellatioN exceeded the form and ontology of its making. Once liberated into the world-flows, its experiential materials became active participants in the enTAngled relationship between experiencer-maker, redirecting the world-flows to reorient perspectives around how we understand notions of self and other. They enabled new formulations of subjecthood and objecthood that moved beyond representation, as enTAngled 'human-nonhuman' assemblages (Bennett 2010:xvii). An enTAngled juxtaposition of incongruent materials, such as silver ducting, wires, beads and wooden painting stretcher frames, whose experiential materiality was activated to give creative specialness and worth to mundane things.

Imprints of intense immersion in creative proceSS

The link to the artist and her creative activities is crucial for activating materials and enTAngled relationships. Walter Benjamin (1969:4) identified that the authenticity and uniqueness of viewing original art objects gives art forms a transcendental 'aura'. This aura is charged with impact and subjectivity through the art form's material facture and existence in time and space. For Isabelle Graw, the activity of painting leaves a 'non-specific index' that evokes a physical coNNection to an imaginary 'ghost-like' presence of its maker (Graw & Lajer-Burcharth 2016:91). Painted brushstrokes can be read as tracing both the labour of making and 'the painter's life experiences' (Graw & Lajer-Burcharth 2016:100), saturating painting with the life of the artist. The act of marking a surface, together with forces of creative construction, hold the 'relation between gesture and outcome' as 'records of movement that testify to those creative movements' (Crowther 2017:3). A painting's meaning derives from the link between its intrinsic material features and the bodily experiences of the artist: from how the artist's relation to her world and space becomes embodied within the painting's signs of mark-making (Crowther 2017:4).

My immersion in painting and the

in-out-in-out-in-out-in-out-

out-in-out-in-out-in-out-in-

in-out-in-out-in-out-in-out-

meditation of weaving gives access to experiences and knowledges that are deposited within my artist-woman body. My creative proceSS unfolds through my body, which serves multiple functions, acting as the protagonist, activator, repository and receptor, in tune with the external environment. I carve out a space of personal significance that is unique to my life as my artist-woman body 'imprints' its mark on woven and painted surfaces (Graw & Lajer-Burcharth 2016:96). I 'bind' my 'pathways or lines of becoming into the texture of material flows comprising the lifeworld' (Ingold 2010:96), which become embodied in the material forms I make. My artist-woman body is literally enTAngled into every thread.

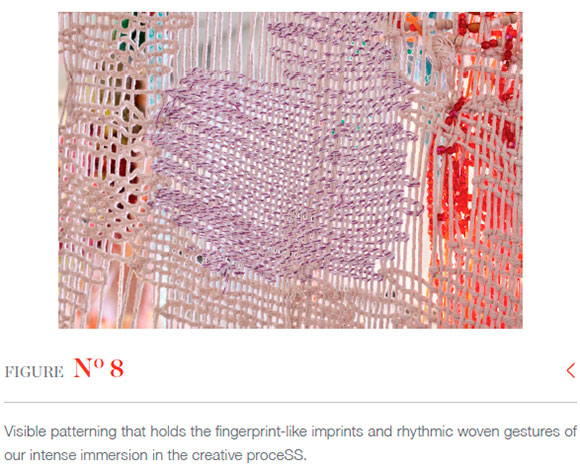

The ritualistic and rhythmic gestures of iterative creative weaving proceSSes impart an indelible and visible sense of pattern, repetition and human touch as they build up surfaces (Figure 8). My rhythms and woven gestures, and those of other makers with whom I collaborate, are imprinted as autographic traces within the surfaces. Our collective movements and creative decisions, along with the enTAngled intimacy and reciprocity of our relationships, get imprinted as fingerprint-like contributions. Woven surfaces enmesh our bodies and lives, materialising the intensity of our embodied gestures and mapping layered traces of making.

We leave our mark.

A performance of labour

Lingering remnants of my creative activities, and those of my collaborators, were held in the constellatioN and brought to life within the exhibition space (Jones 2015:20). The experiencer's presence in the exhibition space activated 'vital' materials, which were liberated into the world-flows, animating our subjective labour. As an experiencer, I felt physically infused in a performance of the creative labour (Jones 2015:20), identifying with the intense artistic labour and exertion, through a rhythmic in-out pixellated quality and sheer volume of displayed work. Yet, the performance included more than just the traces of our combined creative labours. The constellatioN performed and animated, over time, also what is embedded in my artist-woman body, as well as in the bodies of the people with whom I weave. Within the "alchemy" of my exhibition, the performance element brought "to life" the intensity of our gendered labour and enforced social and cultural constraints as women, along with our accumulated life experiences.

Recognising the gendered nature of this visceral and intense experience of labour, and understanding my hybrid proceSS as powered by the intensity of these gendered experiences, is critical to the experience of my constellatioN. The force of our labour - the honesty, authenticity, humility and vulnerability with which we engage in the making proceSS - are essential residual elements in this aesthetic encounter and to the embodied coNNection that the constellatioN creates. Labour holds significance beyond the moment of action (Jones 2015:23). The constellatioN visibly preserved that creative labour as an evocative 'record of the past action' (Jones 2015:20). This diverges from Marx's theory of labour, in which labour is purposively erased and made invisible in most mass-produced consumer products (Jones 2015:20,22). While the constellatioN was temporal and could only be experienced by those present for the short time of its installation, it also appeared to flatten time as those residual traces of past labours and life experiences were brought into the present, becoming activated and viscerally felt, within my constructed forms (Jones 2015:28). 'Experienced time and historical time' were united as they become 'mediated in the viewer's bodily and aesthetic experience' (von Hantelmann 2014:[Sp]).

A transsubjective meeting point - the embodied impact on the experiencer

Drawing on Bracha Ettinger (2004), Griselda Pollock (2011:[Sp]) frames the relationship between the experiencer and artist in the aesthetic encounter as an 'event-encounter', in which the artist gives a 'gift' to the experiencer. This gift package or 'matrixial object' positions the bodies of maker and experiencer in relation to each other, aiming to forge a bodily or phenomenological coNNection and longing 'for a moment of transsubjective coNNection and sharing' (Pollock 2009:484). Each body brings her own unique fleshy materialities, partial perspectives and histories into this moment of encounter:

the artist carries her own traces of histories through family and culture, channelling consciously as well as unconsciously many remnants and shared histories. The same is true for the viewer. Many strings are woven across time and space in the event-encounter with which all parties are resonating as well as working to bend affective vibration towards communicable understanding (Pollock 2009:484).

Submerging within and becoming part of the constellatioN, posited the body of the experiencer in relation to my artist-woman-body. This meeting point, or gift package, brought multiple possibilities to establish human-to-human coNNection and sharing. The embodied moment of coNNection and conversation happened below the radar of "rational" thought, within the subconscious mind and receptive body of the experiencer. It held potential to generate meaningful transsubjective coNNection, full of raw emotion and dazzling complexity, as it relished (and thrived on) the uniqueness of each party's embodied experiences in the world. The 'event-encounter' enabled a genuine recognition of differences able to 'tolerate...a sense of separateness and difference' (Pollock 2009:484). A space of mutual respect and ethical conduct ensued.

5. CONCLUSION

EnTAngling lingering traces of creative activities with vitalistic objects, the embodied form of the constellatioN stood outside of representation. It signalled a return to forms of knowledge produced from and by the body. As an experiencer, I engaged with and decoded the constellatioN through my body in non-verbal ways -foregrounding sensation, deep listening and receptivity - and putting perception and intuition ahead of intellect (Jones 2015:29). Positioning the multi-intelligent body as a primary source of human intelligences and knowledges opens up possibilities for other ways of knowing. Established concepts of objecthood can similarly be reformulated to rethink agency beyond human-centrism.

The constellatioN held the stimulus for continual destabilisation, juxtaposing contradictory elements that were forced to coexist: the tiny and insignificant were monumentalised; chaos opposed structure. Not a conventionally "finished" art form, it rather retained an unresolvedness that suggested a continuous proceSS of working things out. Perspectives within my constellatioN changed constantly, enabling a "montage" of multifaceted imagery, relationships and meanings to emerge. There was no clarity on whether the constellatioN, the activated body of the experiencer, or the relationship of experiencer to artist-woman, comprised the artwork under review. Through my creative proceSS, eXe "unseTTled", "destabilised" and "disowned" as a way to question the logic/illogic of accepted knowledges.

The constellatioN embodied that moment of coNNection when we think we've grasped something, yet it slips away. Ambiguous and mutable, attempts to understand definitively were elusive. In the searching-almost-grasping-but-not engagement that the constellatioN offered, meaning could not be fixed, reduced to words or located. Clarity evaded us. Meaning was Fugitive.3

Notes

1 My activation of the exhibition space contrasts sharply with the 'white cube' gallery space which Brian O'Doherty (1976) exposed to encourage passive reaction to artworks to distance viewers. This shapes the gallery as the arbiter of taste and investment value, the space for discourse, and 'reinforces hierarchies of elite culture' (Bishop 2005:10). Architectural features purposefully resemble religious settings, with the space emptied of economic and social context to imply artistic posterity (and thus a good investment). Through these designed measures, the spectator is cut off from their body and its functions - distanced and disembodied - as they engage with artworks purely through vision.

2 The fixity of linear perspective is traced to the 'geometrisation of vision', which developed in the Renaissance (Copjec 1996:24), yet still has a firmly entrenched 'vice-like grip' on contemporary thought (Bolt 2004:13).

3 Penny Siopis (1997:55) foregrounds 'the idea of the fugitive' as 'that which cannot be fixed, which cannot be located'.

References

Albers, A. 1982. Material as metaphor. [O]. Available: https://albersfoundation.org/artists/selected-writings/anni-albers/#tab4 Accessed 26 July 2018. [ Links ]

Arendt, H (ed). 1969. Illuminations. New York: Schocken Books. [ Links ]

Barad, K. 2003. Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28(3):801-831. DOI 10.1086/345321 [ Links ]

Benjamin, W. 1969 [1935]. The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction, in Illuminations, edited by H Arendt. New York: Schocken Books:217-252. [ Links ]

Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant matter. A political ecology of things. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Bishop, C. 2005. Installation art: A critical history. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bolt, B. 2008. A performative paradigm for the creative arts? Working papers in art and design. University of Melbourne. [O]. Available: https://www.herts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/12417/WPIAAD_vol5_bolt.pdf Accessed 18 January 2021. [ Links ]

Bolt, B. 2004. Art beyond representation: The performative power of the image. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. [ Links ]

Braidotti, R. 2006. Posthuman, all too human: Towards a new process ontology. Theory, Culture & Society 23(7-8):197-208. DOI: 10.1177/0263276406069232 [ Links ]

Copjec, J. 1996. The strut of vision: Seeing's somatic support. Qui Parle 9(2):1-30. [ Links ]

Crowther, P. 2017. What drawing and painting really mean: The phenomenology of image and gesture. New York: Routledge:1-15. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G. 1981. Francis Bacon: The logic of sensation, translated by D Smith. London: Continuum:34-43. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G & Guattari, F. 2004 [1980]. A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia, translated by B Massumi. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Ettinger, B. 2004. Weaving a Woman Artist with-in the Matrixial Encounter-Event. Theory, Culture & Society 21(1):69-94. [ Links ]

Fischer-Lichte, E. 2008. The transformative power of performance, translated by S Iris Jain. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Fournier, L. 2021. Autotheory as feminist practice in art, writing, and criticism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Graw, I, Birnbaum, D & Hirsch, N. 2012. Thinking through painting. Reflexivity and agency beyond the canvas. Frankfurt: Sternberg Press. [ Links ]

Graw, I & Birnbaum, D. 2016. Painting beyond itself: The medium in the post-medium condition. Frankfurt: Sternberg Press. [ Links ]

Graw, I & Lajer-Burchart, W. 2016. The value of liveliness: Painting as an index of agency in the New Economy, in Painting beyond itself: The medium in the post-medium condition, edited by I Graw and D Birnbaum. Frankfurt: Sternberg Press:79-101. [ Links ]

Grosz, E. 1994. Volatile bodies: Toward a corporeal feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Haraway, D. 1988. Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies 14(3):575-599. DOI: 10.2307/3178066 [ Links ]

Heidegger, M. 1977. The question concerning technology and other essays, translated by W Lovitt. New York: Garland. [ Links ]

Ingold, T. 2010. The textility of making. Cambridge Journal of Economics 34:91-102. DOI: 10.1093/cje/bep042 [ Links ]

Ingold, T. 2007. Materials against materiality: Discussion article. Archaeological Dialogues 14(1):1-16. DOI: 10.1017/S1380203807002127 [ Links ]

Jones, A. 2015. Material traces: Performativity, artistic "work," and new concepts of agency. The Drama Review 59(4):18-35. DOI: 10.1162/DRAM_a_00494 [ Links ]

Lacey, S (ed). 1995. Mapping the terrain: New genre public art. Seattle & Washington: Bay Press. [ Links ]

Lange-Berndt, P. 2015. Introduction//how to be complicit with materials, in Materiality, edited by P Lange-Berndt. London and Cambridge: Whitechapel Gallery and The MIT Press:12-23. [ Links ]

Lauwrens, J. 2019. Seeing touch and touching sight: A reflection on the tactility of vision. The Senses and Society 14(3):297-312. DOI: 10.1080/17458927.2019.1663660 [ Links ]

Marks, L. 2000. The skin of the film: Intercultural cinema, embodiment, and the senses. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

McElvey, T. 1986. Introduction, in Inside the white cube. The ideology of the gallery space, written by B O'Doherty. Santa Monica & San Francisco: The Lapis Press:7-12. [ Links ]

Merleau-Ponty, M. 2012 [1945]. Phenomenology of perception, translated by C Smith. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

Meskimmon, M. 2019. Art matters: Feminist corporeal-materialist aesthetics, in A companion to feminist art, edited by H Robinson and M Buszek. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.:353-367. DOI: 10.1002/9781118929179.ch20 [ Links ]

Nuttall, S. 2009. EnTAnglement: Literary and cultural reflections on post-apartheid. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

O'Doherty, B. 1976. Inside the white cube. The ideology of the gallery space. The Lapis Press. Santa Monica & San Francisco. [ Links ]

Pollock, G. 2020 [1981]. Preface to the Bloomsbury Revelations Edition, in Old mistresses: Women, art and ideology, edited by R Parker and G Pollock. London and New York: Bloomsbury:xx-xxvi. [ Links ]

Pollock, G. 2011. What if art desires to be interpreted? Remodelling interpretation after the 'encounter-event'. [O]. Available: https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/15/what-if-art-desires-to-be-interpreted-remodelling-interpretation-after-the-encounter-event Accessed 11 May 2021. [ Links ]

Pollock, G. 2010. The missing future: MOMA and modern women. [O]. Available: https://www.moma.org/d/pdfs/W1siZiIsIjIwMTgvMDYvMTMvMWY3cHV2bnFqcl9Nb2Rlcm5Xb21lbl9Qb2xsb2NrLnBkZiJdXQ/ModernWomen_Pollock.pdf?sha=32abcae0d6c8c3c2 Accessed 19 January 2022. [ Links ]

Richards, C. 2005. Prima facie: Surface as depth in the work of Penny Siopis, in Penny Siopis, edited by C Smith. Johannesburg: Goodman Gallery Editions:6-46. [ Links ]

Siopis, P. 1997. Domestic affairs. De Arte 55:55-69. [ Links ]

Vesters, C. 2016. A Thought Never Unfolds in One Straight Line. On the exhibition as thinking space and its sociopolitical agency. Stedelijk Studies 4. [ Links ]

von Hantelmann, D. 2014. The Experiential Turn, in On Performativity, edited by E Carpenter, Living Collections Catalogue 1. Minneapolis, MN: Walker Art Center. [ Links ]