Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Image & Text

versión On-line ISSN 2617-3255

versión impresa ISSN 1021-1497

IT no.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a24

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

From the physical to the digital: Encounters in the KKNK online gallery

Dineke Orton

PhD candidate with the South African Research Chair in South African Art and Visual Culture Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture, University of Johannesburg Johannesburg, South Africa. dinekeorton@gmail.com (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3461-1358)

ABSTRACT

This study explores the processes and curatorial techniques that support corporeal engagements with online exhibitions. Exhibitions, physical and otherwise, are a complex interplay between spaces - real and imagined -audiences, and tangible or intangible objects. This is a guiding notion of this article, supported by Merleau-Ponty's perspective of the relation between internal human experiences and the external bodily encounters that shape them. I maintain that differing digital curatorial presentations can enhance or subdue the embodied interaction of visitors. By relying on my lived experience of navigating the transfer of the Klein Karoo National Arts Festival's visual arts programme of 2020 to the online sphere, I discuss various strategies deployed to encourage embodied engagement. Amongst other findings, the study underscores the need to consider audience preferences and allowing visitors a sense of agency to choose how they want to engage artwork online. Even though the arena of exchange might differ, I argue that all exhibitions, whether online or brick-and-mortar, provide audiences with the possibility of an engaging experience. In addition to the exhibition itself, viewers embody another energy - and it is the viewer's deliberate performance and choice to interact that produces the distinctive experience of an exhibition.

Keywords: Art festival, Down to Earth, curating, embodied viewing, imagination, Klein Karoo National Arts Festival, KKNK, online gallery, virtual exhibition.

From the physical to the digital: Encounters in the KKNK online gallery

In March 2020, when 90 percent of museums and galleries worldwide were forced to close their doors due to the Covid-19 crisis (O'Hagan [Sa]), trucks loaded with artwork destined for 11 art exhibitions were making their way to Oudtshoorn for the Klein Karoo National Arts Festival (KKNK). The KKNK, due to take place from 23 to 29 March 2020, has been held annually since 1995 in the Klein Karoo region of the Western Cape (Erasmus, Saayman, Saayman, Kruger, Viviers, Slabbert & Oberholzer 2010:2). Past attendances have marked it as one of the largest art festivals in South Africa (Saayman, Kruger & Erasmus 2012:2). More than 1000 artists perform and exhibit annually in genres such as music, theatre, dance and visual art (Erasmus et al. 2010:1). From a regional perspective the festival not only provides a vital source of revenue for "Oudtshoornites" but offers a tremendous economic boost to the surrounding areas.1 Nonetheless, like cultural events worldwide, the KKNK had to be cancelled - a mere ten days before its planned opening.2

As the visual arts curator for the festival, I was tasked with a decision to either postpone the visual arts programme or attempt to reconfigure the exhibitions to an online viewing platform. Certain artworks were on loan for the specific period and others were destined for upcoming exhibitions. If we were to postpone, some exhibitions would need to be reconstructed while others would be unavailable. An online presentation thus emerged as the most promising solution, although it still posed challenges. Engagements with online exhibitions, for instance, cannot assume to create the same modes of embodied viewing as physical exhibitions do. And several exhibitions in the programme comprised installation components or required bodily interaction.

For Martin Kalfatovic (2002:34) visitors to an online exhibition have less control over their environment. While his statement might hold some truth, it is important to consider how individual digital modalities allow different levels of freedom for visitors. Since the closures of exhibition spaces during the 2020 lockdown, rapid development and promotion of online content has taken place. Numerous organisations actioned surveys to determine the impact of Covid-19 on cultural sectors. Organisations such as UNESCO, ICOM (the International Council of Museums) and NEMO (the Network of European Museum Organisations) documented online activities of museums and galleries during the first months of the pandemic. The results of a study conducted by King, Smith, Wilson and Williams (2021:495), which traced the digital behaviour of museum exhibitions in the United Kingdom, point to the fact that presenting online exhibitions using a variety of methods affords visitors flexibility and freedom to explore these online presentations. King et al. (2021:493) further argue that online exhibitions afford increased access for audiences who would otherwise be unable to physically view exhibitions. The upsurge in online exhibition content additionally results in reaching wider audiences and thus being more inclusive in their audience engagement. The most prominent theme to emerge from their study, however, is the importance of embodiment and attempts to facilitate embodied viewing of online presentations (King et al. 2021:496). While their study provides valuable contributions of larger themes and various modes of online presentations, practices through which embodiment might feature or be enhanced have not been exhausted. The role of curatorial praxis similarly remains underexplored in relation to embodied engagements of online exhibitions.

It is in this unexplored area that I situate my paper to examine the considerations and curatorial strategies that might be effective in enhancing embodied engagements with online exhibitions. Taking as a starting point the assertion of Tröndle, Greenwood, Bitterli and Van den Berg (2014:1) that 'exhibitions are complex networks of actions and force fields in which a rapport between visitors, architecture and things [artworks] can be generated', I begin by fleshing out what an engagement with an exhibition might entail. I draw on the work of John Dewey (1934), and Maxine Greene (2001) regarding their understanding of the experience of art and rely on Maurice Merleau-Ponty's (2012 [1945]:246) assertion that all forms of human experience and understanding are grounded in, and shaped by, our bodily orientation in the world.

With this in mind I argue that all exhibitions give rise to a specific form of experience. And it is the strategic design of the exhibition, whether online or in brick-and-mortar, that affects visitors' tendency to embrace embodied interaction. I follow King et al.'s argument that different digital curatorial presentations allow different levels of freedom, agency and embodied viewing for visitors. To unpack the possibilities of crafting an experience for online viewers, my discussion considers the practices of presenting and engaging artworks in the KKNK 2020 online gallery. I thus make use of an autoethnographic approach to draw from my lived experience of navigating the translation of the KKNK visual arts programme to an online environment to discuss the digital curatorial strategies we employed in an attempt to raise viewers' imaginative engagement with the artworks.

Down to Earth

The 11 exhibitions that made up the 2020 visual arts programme for the festival were conceptualised around a specific overarching theme, Down to Earth/Plat op die Aarde.3 This created a focus for the exhibitions to present various perspectives on the complex human interaction with, as well as the responsibility for, the natural environment. The Covid-19 pandemic intensified concerns regarding environmental sustainability and the need for collective reflection on matters of loss and survival. This worldwide shift thus enhanced the importance of this conceptual anchor for the visual arts offering - rendering it particularly timely.

The exhibition programme 'include[d] works from 45 artists and more than 200 artworks' (KKNK 2020).4 But as Kalfatovic reminds us, a collection of objects does not make an exhibition. Rather, '[i]t is only when objects are carefully chosen to illustrate a theme and tied together by a narrative or other relational thread that they become an exhibition' (Kalfatovic 2002:1). Accordingly, each exhibition was individually envisioned by the exhibiting artist, curator or gallery, and designed for a specific brick-and-mortar section of the Prince Vintcent building in Oudtshoorn. In the same way that artworks on these exhibitions were carefully selected and unified to illustrate a perspective, so too did I combine and tie together the 11 distinct exhibitions to form my overarching curatorial vision. Given the restrictions on public events during 2020, an online presentation would allow these meticulously formulated exhibitions to still meet their publics.

The art exhibition as a specific form of experience

Visiting an art exhibition is generally considered a predominantly visual experience. Visitors are often referred to as viewers, since they are assumed to rely predominantly on sight when encountering artworks. In his seminal work, Art as Experience (1934), philosopher John Dewey considers this encounter with artworks. For Dewey art presents viewers with not merely any experience but with what he calls 'an experience' (Dewey 1959 [1934]:214, emphasis in original). Viewers do not merely surrender to artistic stimuli and images do not themselves establish their meaning. Instead, Dewey explains, the art experience is about the artwork as well as the person encountering it - the interaction between the two is what generates it.

This notion of the significance of interaction and active decisions on the part of the viewer is echoed by Norman Bryson (2004:3), who states that rather than a relay conveying an intention from the artist to the viewer, the work of art is better understood as an occasion for a performance in the 'field' of its meaning. Instead of an artwork conveying a specific meaning, the process of coming to an understanding and generating meaning when encountering artworks, has become paramount. For such an encounter to take place, I would add, art needs to be made public. And it is the exhibition, whether online or physical, that most often prioritises the artwork's interaction with viewers - its being made public (Steeds 2014:13).

During the public event of an exhibition, art is positioned within an atmosphere of 'force fields' generated by other artworks as well as the spatial, architectural and curatorial settings (Tschacher & Tröndle 2011:254). To this Roger Simon (2014:198) adds that '[t]he force and meaning of any given set of images on display are never produced in isolation but are always situated in a broader discursive economy'. Elements within an exhibition thus draws on associative powers stored from previous encounters of viewers. As Alexander Dorner (1958 [1947]:120) puts it,

The exhibition itself ceases to be basically a self-contained, static condition and becomes more and more an aggressive energy seeking to transform the visitor. The visitor is another energy, a different form of life. Both energies interact.

This signals an appreciation of viewing as an active practice that can be understood as the discovery of a pre-existing reality while simultaneously contributing to that reality. Mieke Bal (2004:42) further notes that '[p]erception...is a psychosomatic process, strongly dependant, for example, on the position of the perceiving body in relation to the perceived object'. Viewers, therefore, represent specific ideas, ideologies, viewing habits, power positions, and interests. They attend to particular features of their environment, constituting a biased, selective focusing of awareness (Tullmann 2017:482).

According to his conception of relational aesthetics, Nicholas Bourriaud (2009:16) maintains that art, coming across in the form of an exhibition, produces a specific sociability. According to a visitor study by Crowley, Pierroux and Knutson (2014:463470) for instance, the majority of museum visitors are accompanied by friends or family, with different social dynamics steering each visit. The significance of social interchange and social conditions are increasingly being emphasised through visitor studies, signalling the impact of other viewers in the exhibition space (see Pierroux 2003; Falk & Dierking 1992; Knutson & Crowley 2010). Since perception, for Merleau-Ponty (2012:1255), originates with one's embodied 'being-in-the-world', viewers in physical spaces are conscious of their bodies in the space, in relation to the artworks and to other viewing bodies. There is also an awareness of how this corporeal presence affects the viewing experience. Online viewing, however, is commonly a solitary experience. This remoteness and seclusion that visitors to an online gallery might experience, is an important detail, I propose, for curators to consider. While the process of viewing art during a physical exhibition is highly performative, the online gallery affords viewers freedom from an awareness of themselves in the space. Viewers are thus unshackled from the burden of self-awareness in the online gallery.

Merleau-Ponty proposed the body be considered as 'anchorage' that allows each individual a point of view in the world. He states that 'all forms of human experience and understanding are grounded in and shaped by our...bodily orientation in the world' (Merleau-Ponty 2012 [1945]:145). Information is accumulated through the senses as physical bodies interact with the environment. Be it in a visual arts programme displayed at an arts festival or elsewhere, the audience is using and moving their bodies continuously. Visitors may be unaware of this, yet they respond to the contents on display with and through their bodies. During online viewings, viewers still respond with their bodies through facial expression, body postures and gestures (such as pointing, clicking, moving closer to the image on the screen, smiling or frowning).

The surrounding environment for online viewers comprises both the physical space in which they view the exhibition on a screen as well as the virtual rooms through which they 'walk'. I postulate that when viewers somatically utilise their environment, let's say a computer and mouse, to socially connect or interact -leaving a comment, listening to audio walkabouts - with and through an online viewing space, they can be considered as undertaking embodied interaction. This, I believe, is especially true when traces of their visit and interchange are visible for others to find and interpret.

When viewing is understood in this way as subjective and thus relative to the individual body engaging the artwork, it follows that encounters with artworks -whether in brick-and-mortar or through an online platform - are fundamentally embodied experiences.

The power and usefulness of imagination

According to Greene (2001:32) it is imagination that provides the only gateway through which meaning can enter any experience. Similarly, Lessing (1984:19) emphasised the mutually dependant relation between seeing as a physiological act and imagination as a mental process. A useful definition is crafted by Kieran Egan and his Imaginative Education Research Group (2018:[Sp]). It reads:

[Imagination] is the ability to think of the possible, not just the actual; it is the source of invention, novelty, and flexibility in human thinking; it is not distinct from rationality but is rather a capacity that greatly enriches rational thinking; it is tied to our ability to form images in the mind, and image-forming commonly involves emotions.

Imagination is thus the ability to think, and to think of the possible requires intentionality and practice. Viewing artworks and employing one's imagination are 'grounded in the bodies of the participants, including their brains' (Hydén 2013:228). Far from being a passive pastime, viewing, thus, implies an active intake of sensory information while simultaneously making sense of that information (Jackson 1998:57; Tullmann 2017:482). Imagination then, becomes an important key through which viewers of online presentations can access prior experiences to co-produce an experience with art.

Exhibitions at an art festival

When considering the exhibition event at an art festival, an additional social contextual layer is evident. A study conducted by Saayman, Marais and Krugell (2010:95) suggests that visitors to arts festivals are in search of a total experience - consisting of various features such as the attractions, the shows, the variety of entertainment, restaurants as well as an opportunity to meet new people. Venturing to meet the needs of visitors, organisers often strategically amalgamate several elements to produce a distinctive, unforgettable festival experience. Arts critic Chris Thurman (2012:46), writing about the Grahamstown National Arts Festival, provides a glimpse of what a festival experience might entail when he states that,

whether you are a hardened Jo'burger, a Capetonian sophistiqué or an inhabitant of any big metropole, you're guaranteed to become disoriented at some point. If the throngs of colourful festival-goers, the thousands of posters competing for your attention, the street vendors and the temptations of numerous restaurants and pubs don't confuse you, the plethora of performance and exhibition venues will.

The same can most probably be said of any of the major art festivals in the country. It is often an overwhelming visual and colourful escapade. Each year the KKNK ushers thousands of culture vultures or festinos to Oudtshoorn in search of art experiences, captivating productions and general light-hearted entertainment. Had the KKNK proceeded as planned and all artworks installed in the Prince Vintcent building, encounters with artworks would have been submerged in an atmosphere of festivity and general invigoration. Moments preceding encounters with artworks might have been related to engaging other forms of art such as plays, music performances and book readings. Festivalgoers would be having what Dewey calls an experience. Merleau-Ponty (2012 [1945]:10) calls this experience a world as a whole wherein the perception is very much a bodily one and visitors are fully engaged in a momentary, consuming experience.

While an online exhibition can also be understood as an occasion that creates and curates a moment for artworks to meet its publics, the interaction, experience and arena of exchange will necessarily differ. It is fairly evident that an online exhibition does not provide the same world as a whole or total festival experience. There is no travel through the wide-open spaces of the Klein Karoo to get there, no welcome from a member of staff, no opportunities to bump into artists and curators at the nearby coffeeshop for impromptu discussions. The lack of this socially-embodied interaction is evident. However, if every occasion of viewing comes from the body's relations to it, it follows that the experience of online exhibitions would similarly be an embodied interaction.

Online exhibitions as an experience

Online exhibitions are not conceived in a literal three-dimensional space. Still, this does not mean that an online display needs to be a dull, static collection of images presented in a strict, linear fashion. On the contrary, Palmyre Pierroux (2009:293) argues that,

the design of interfaces should be considered an art form, similar to a performance, where shifts of attention are orchestrated throughout the text - which has the commanding role - and the other elements of the play.

In an online exhibition, as in a brick-and-mortar show, it is the presentation that brings to life the intellectual content and unleashes the potential dynamism of the objects (Kalfatovic 2002:35). Thus, one needs to ask how an online exhibition should be conceived to maximise the possibilities of online design and minimise the disadvantages of the online environment.

Fortunately, online art spaces have been growing in the years leading up to the pandemic. An increase in online offerings and digitisation of exhibitions and collections has been traced over the last few decades (see for example, Parry 2010; Wellington & Oliver 2015; Williams 1987). In a 2015 interview5 economist Clare McAndrew explained the development of the online art space as greatly themed towards the democratisation of art, bridging the gap between the elite world of top collectors and the general public, and making art more accessible (DeWitt 2015:[Sp]). Edward Winkleman (2017:167) adds that the value of online art sales channels has been described or justified according to two basic categories. The first emphasises the viewers' convenience of being able to search and find artwork more easily while the second argues that the viewer enjoys an enhanced sense of comfort and access to view works. The KKNK web analytics adds weight to this reasoning. It illustrates how viewers visited the online gallery over weekends and at times when most galleries in South Africa would be closed to the public - thus bypassing the customary and restricting nine to five viewing. The comfort/access-argument is further supported by the notion that visitors often feel intimidated by 'the legendary icy reception...they have experienced or heard are common in physical galleries' (Winkleman 2017:167).

While conceptualising the virtual gallery, an important consideration centred on viewers' preferences and understanding how audiences would feel comfortable engaging artworks online. With some knowledge of devoted KKNK visual art audiences and an understanding that online presentations would make the exhibitions accessible to wider audiences in South Africa and abroad, I anticipated that some visitors might be intimidated by virtual reality presentations while others could find easier linear presentations monotonous and uneventful. Given the heterogeneity and intergenerational character of exhibition audiences, visitors would inevitably have differing preferences, expectations and prior experiences - of both digital platforms and exhibition viewing.

A question of viewer agency

Similar to King et al.'s (2021:495) suggestion of utilising a variety of methods, I preempted that showcasing works in more than one way in the online gallery might be particularly helpful. Instead of visitors entering one building where exhibitions would naturally flow from one to another, the exhibitions in the KKNK digital gallery space are each displayed on a separate page within the KKNK website.6 From the gallery's landing page (or hub), visitors can easily select an exhibition to explore the different 'rooms' of the gallery. This 'hub and spoke' model is considered a more free-flowing approach (as opposed to one-page, linear layouts), since visitors can access content by moving back and forth from the main page (King et al. 2021:495). Similar to audiences choosing to enter physical exhibition rooms, so the online visitor too can deliberately decide to enter a specific gallery room. However, the added benefit now is that visitors get to choose which room to enter first and in what order to view the exhibitions.

In a visitor study of physical exhibitions conducted by De Backer et al. (2015), some audience members indicated that they did not start watching videos or listen to audio-interviews because of a lack of control. Since videos are often on loop to play repeatedly in brick-and-mortar spaces, a visitor might arrive in the middle of the digital offering without having control to rewind it or knowledge of the length or starting time. Other visitors indicated that they would prefer to watch videos at home on the internet (De Backer et al. 2015:159). To my mind these findings indicate a lack of agency of viewers, resulting in frustration and lower levels of engagement. In the KKNK online gallery, exhibitions like Kicking Up Dust for instance include videos of the curator and the three artists.7 On such exhibition pages, audiences can choose when the video should start, stop or rewind. Online visitors are thus provided with enhanced agency when it comes to watching videos. The impact of this is echoed by the KKNK web analytics which indicate that visitors spend more time on exhibition pages where videos are included - signalling users' active engagement with these exhibition tools.

Creating a sense of movement

While drafting the online gallery, I tried to keep in mind how visitors might 'move' in the space to pre-empt any discomfort and devise enjoyable viewer experiences. In their study King et al. (2021:496) noted how significant attempts were made to transform the online exhibition experience from 'just browsing a website' to giving visitors a sense of movement and an active journey. To this end, language was used such as 'visit' the exhibition and giving audiences various options to 'explore'. In the KKNK online gallery, visitors are similarly tasked to 'enter' the virtual room, to 'walk' through it, and to 'visit' the online gallery.

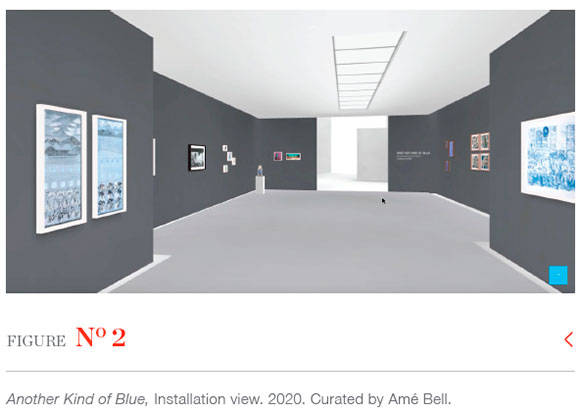

Landing on an exhibition page, visitors are greeted by an option to 'enter' the virtual reality room through which they can 'move' in an artificial 360-degree environment. Each virtual exhibition space is selected and curated by the relevant artist or curator - affording them agency in how artworks are displayed. The KKNK 2020 Festival Artist, Barbara Wildenboer, for instance, assembled work for a retrospective, comprising a thematic and formal overview of her previous ten solo exhibitions (Figure 1). Throughout her oeuvre, her main focus on environmental aesthetics, understood as something that encompasses natural territories but also extends to the human interaction with the natural realm, form a clear link between the works selected for the show. Similarly, the group exhibition, Another Kind of Blue, is a thoughtfully composed collection of work (Figure 2). Through the curatorial vision of Amé Bell, artists explore the colour blue and its kaleidoscope of shades and meanings - in a variety of mediums - with a focus on art and the artist's connection with the earth and its elements.

Since it provides visitors with the most freedom and ability to click on both artworks and text panels to gain more information, virtual reality 360-degree tours are considered an ideal solution for optimal visitor control. But not everyone feels comfortable entering virtual reality rooms. For this reason, I also included other ways for visitors to access the exhibition images and information. Scrolling down from the virtual room one can find an audio walkabout - with the particular curator or artist imaginatively 'walking' the visitor through the exhibition. This is an attempt to add voices to the empty spaces, to give visitors accessible information, and to add personality to each distinctive space.

Images of each artwork forming part of the exhibition are shown further down, accompanied by artwork 'labels' and artist statements on the pieces. An 'enquire now' button gives visitors an opportunity to send an email directly to the KKNK gallery staff, who would provide assistance to anyone wanting supplementary information. At the bottom of each page additional contact details are provided, as well as a visual overview of the collection of artworks. All information available on the artists, artworks, curators and galleries is made available on these exhibition pages, making it a one-stop for all information on the exhibition. Importantly, the exhibition page concludes with a visitors' book that can be signed and used to leave comments, 'in an attempt to help put "faces" (or rather names) to the visitors' (De Beer 2020). This tool also allows exhibitors a form of interaction with their audiences.

Reconfiguring installation-based works

Since audience engagement had been a primary objective of mine, a number of displays for the physical exhibitions had been designed to include immersive installation elements. It became vital to find a way to present these immersive qualities in the virtual gallery space too because I found such features crucial. At the same time, it was important not to exclude artwork based on medium or a format which might be challenging to translate digitally. Although I had no experience in converting such works online, I found it important to endeavour to do so.

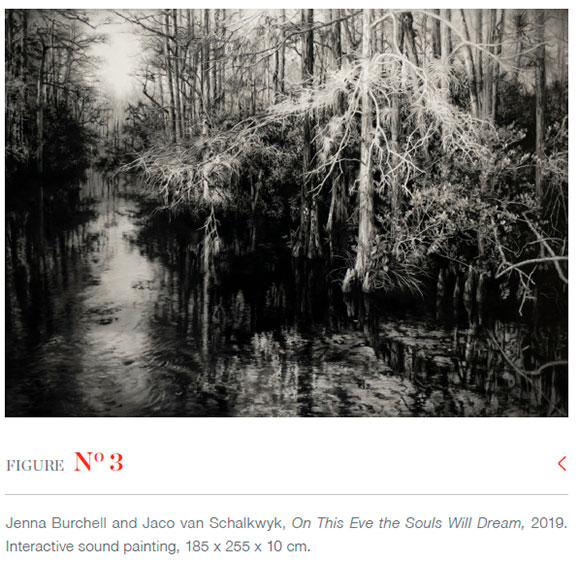

Through trial and error, we - the curators, artists, the web designer and I - found some solutions. Two artists forming part of the exhibition A Land I Name Yesterday, Jenna Burchell and Jaco van Schalkwyk, collaborated on what they refer to as an interactive sound painting9 This work, titled On This Eve the Souls Will Dream (2019) (Figure 3), is impressive both in size (185 x 255 x 10 cm) and owing to Van Schalkwyk's remarkably realistic painting technique. The resulting scale of the artwork and its captivating presence can be described as enticing viewers to gaze at it with absorbed attention, often while moving closer. This is a useful strategy of the artists since it is only when visitors approach the artwork that an additional feature is revealed. When exhibited in a physical space, the bodily presence of a viewer activates a complex system of sound developed by Burchell, which can be manipulated by individual hand movements close to the surface of the painting. While Van Schalkwyk was painting this work, Burchell recorded his brain waves with an Electroencephalography (EEG) device.10 The resulting composition is woven into the canvas as a proximity responsive soundscape of the painter's mind and memory. The visitor's bodily viewing of the painting thus results in them being able to collaboratively produce and compose music. And the singularity of the music being composed is directly related to the physical movements of each particular viewer. It was thus designed to be seen by bodies in spaces.

Jenna Burchell and Jaco van Schalkwyk, On This Eve the Souls Will Dream, 2019. Interactive sound painting, 185 x 255 x 10 cm.

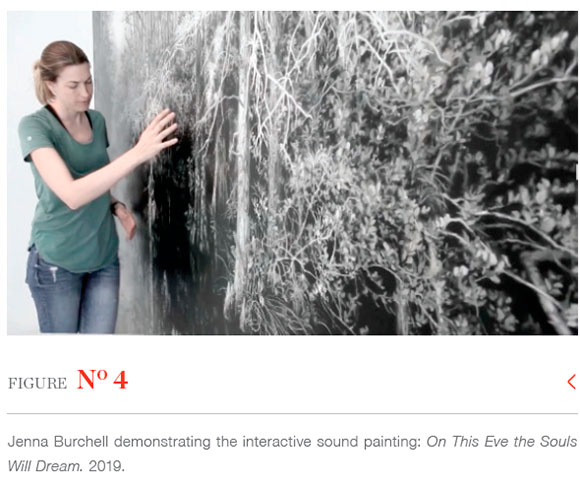

Reconfiguring this complex work for the digital space, a recording of the sound the painting might put forward will start playing when the visitor to the virtual space passes the painting. The painting is further accompanied by an explanation of how it operates and a smaller digital 'screen', installed next to the painting, displaying a video of Burchell demonstrating the physical interaction with the artwork (Figure 4). While not providing the same experience, the online presentation allows viewers to have an experience with the work. This is especially the case since directly after the exhibition, the artwork was shipped to its new owners - thus removing it from public view.

In Kicking Up Dust three young artists from Oudtshoorn worked towards their collaborative exhibition during a year-long mentorship by Absa Gallery. Saaiman, an installation artist, conceptualised an intricate configuration of various elements to bring an immersive environment to life within which visitors could come to a deeper understanding of the devastating effects of the ongoing drought that enveloped the Klein Karoo at that time. In the Kicking Up Dust virtual room, two videos are showcased in close proximity to some of Saaiman's installation elements, while the sound of water dripping rings in the background. Instead of showing the artwork in its totality, the videos represent the feeling the artist wanted the work to elicit by using detailed imagery of the movement and shadows brought forth by the installations. I asked Saaiman to include descriptions of the pieces as a way of capturing her meaning and intention. This afforded her a way to directly communicate with her audience, in a manner that she feels a regular artist's statement cannot. Saaiman mentioned to me that through her poetic descriptions she feels she can create the installation space in the mind of the viewer, even if it does not exist physically (Saaiman 2022). Her virtual installations were consequently predominantly artistically and discursively filtered.

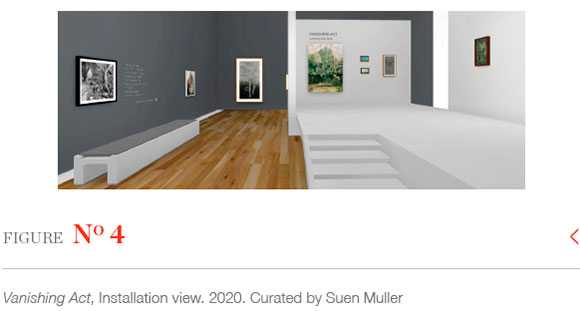

Drawing on prior knowledge

The curator for Vanishing Act (Figure 5), Suen Muller, planned an installation of living plants to accompany and compliment the artworks she selected. The exhibition aimed to visually capture the fragile beauty of various types of plant life whilst bringing to light the effect climate change has already had and will have on earth's biodiversity. Bringing 'life' into the exhibition and presenting plants as sculptural pieces in relation to intricate representations of plant life, had the purpose of enhancing her message. Creatively reconfiguring her exhibition, Muller made use of an alternative curatorial device. Instead of plants, Muller included a quote from singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell as virtual wall vinyl stating: 'you don't know what you've got till it's gone' - a powerful refrain in the context of climate change. According to Thurman (2020:[Sp]), these words presiding over the exhibition 'also capture the feeling of loss that has become so common since the advent of Covid-19'. As such, her tactic draws on the previous knowledge the viewer might have of Mitchell's song, Big Yellow Taxi (1970), and of the pandemic. An experience draws on what came before and leads to what comes after, or, as Dewey(1959 [1934]:18) puts it, '[a]rt celebrates with peculiar intensity the moments in which the past reenforces the present and in which the future is a quickening of what now is'. Our later ability to make meaning derives from - and often continues to depend on -our prior experiences (Jackson 1998:62). Merleau-Ponty (2012:492) calls this the 'sedimentation of our life', indicating how experiences or attitudes from our past sediment into our present experience. Experience, and therefore our expectations and beliefs, shape what we see, hear, feel, and think.

Concluding thoughts

The ways in which an artwork has been made public contributes to the viewer's possible embodied engagement with it. There are various ways of enhancing a sense of embodied interaction. However, considering one's audiences and their preferences is vital. The aesthetic design and technical interfaces need to be user friendly and enticing to lure visitors to continue using their bodies to interact. That is, to continue clicking on links, scrolling to find more information, to read texts and explore artworks through different formats.

When designing an online show, the artworks should, as always, be tied together with relational threads to create a specific arena of exchange with deliberate force fields. Online curators can curate and affect force fields through the assembly of artwork, by ordering, as well as through their spatial and curatorial settings. While not all artwork translates equally in digital formats, videos and discursive framing can assist such shortcomings.

I propose that curators anticipate viewers' needs and provide them with options and hence a sense of agency or freedom in choosing how they want to interact with artworks. Through the web layout and the use of specific wording - to suggest an active journey - curators can create a sense of movement and exploration. This discursive setting acts as a way to activate imaginative engagement of viewers. I also believe it useful to add voices to these empty spaces and provide additional information for viewers who enjoy more in-depth intellectual engagement. Furthermore, viewers need a way to respond to and leave traces of their visit. Therefore, a feedback section of some sort is valuable and can provide powerful correspondence between artists and their viewers.

These strategies are positioned at the curatorial side of the engagement, while individual viewers - as the other energy - have their own particularities. Each viewer has a unique experience of an art exhibition; they choose what to look at, for how long, and what to ignore. This meaning-making performance draws on memories of past encounters while viewers simultaneously juggle a unique psychosomatic position towards what is seen. Whether in a physical space or online, viewing art is a deliberate performance in which viewers decide to interact. Thus, while curators can orchestrate visitors' bodily modes of engagement to an extent, the willing viewer needs to be open to what is offered.

Acknowledgements:

I receive PhD funding from the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa. Please note, however, that any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed here are my own, and the NRF accepts no liability in this regard.

Notes

1 It has been shown that the KKNK provides a necessary economic boost to the town of Oudtshoorn (Herman Eloff 2020).

2 The decision to cancel the festival was communicated to the public on 14 March, one day before Cyril Ramaphosa, president of South Africa, first addressed the nation on measures to combat the COVID-19 epidemic.

3 The curatorial programme Down to Earth/Plat op die Aarde won Best Achievement in Visual Arts at the annual kykNET Fiësta awards in 2021 and received a nomination for the Best Online Festival Project.

4 The programme consists of the following exhibitions: Barbara Wildenboer - a Retrospective (festival artist), Nesting by Usha Seejarim, Needle and Thread by Strijdom van der Merwe, Go sepela nageng ya ditoro (The Possibility of a Journey) by Manyaku Mashilo - curated by Tammy Langtry, Vanishing Act - curated by Suen Muller, A Land I Name Yesterday - featuring Jaco van Schalkwyk, Jenna Burchell and Wayne Matthews (presented by Barnard Gallery), Kicking Up Dust featuring Colin Meyer, Zietske Saaiman and Earlyn Cloud, curated by Tlotlo Lobelo and Dr Paul Bayliss (Absa Gallery), Another Kind of Blue curated by Amé Bell (David Krut Projects), Karoo Stories - featuring Maryna Cotton and Sarel van Staden, #CreativeChange curated by Madeleine Beyers (Make a Difference Leadership Foundation) and Birds of a Feather by Lisl Barry.

5 McAndrew was interviewed about her 2015 edition of the TEFAF Art Market Report, available at: https://tbamf.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/TEFAF2015.pdf

6 The KKNK 2020 virtual gallery can be viewed at https://virtualgallery.kknk.co.za/7_gl=1%2A1kw9yh%2A_ga%2AMTc5ODUzNzI5NC4xNjU3MTA0MDI3%2A_ga_7KGTSTNS6Q%2AMTY1NzEwNDAyNy4xLjEuMTY1NzEwNDA2NC4w&_ga=2.197307814.860789728.1657104027-1798537294.1657104027

7 The videos can be viewed here: https://virtualgallery.kknk.co.za/kicking-up-dust/

8 Every year the KKNK has appointed a well-known painter, sculptor or photographer as festival artist. Festival Visual Artists have included Willie Bester (1999), Claudette Schreuders (2002), Wim Botha (2003), Minette Vári (2005), Lawrence Lemoana (2008), Willem Boshoff (2014), Berni Searle (2015), and Kagiso Pat Mautloa (2016).

9 A video demonstration can be viewed here: https://virtualgallery.kknk.co.za/a-land/

10 Electroencephalography (EEG) is an electrophysiological monitoring method to detect and record electrical activity in the brain using small, metal discs (electrodes) attached to the scalp. Brain cells communicate via electrical impulses and are active all the time. Clinically, EEG refers to the recording of the brain's spontaneous electrical activity over a period of time (Burchell 2019).

References

Bal, M. 2004. Looking in: The art of viewing. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bourriaud, N. 2009. Relational aesthetics. Paris: Les Presses du Réel. [ Links ]

Bryson, N. 2004. Introduction: Art and intersubjectivity, in Looking in: The art of viewing, edited by M Bal. London: Routledge:1-39. [ Links ]

Burchell, J. 2019. Artist Statement. Unpublished. [ Links ]

Crowley, K, Pierroux, P & Knutson, K. 2014. Informal learning in museums, in Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences, edited by K Sawyer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press:461-478. [ Links ]

De Backer, F, Peeters, J, Kindekens, A, Brosens, D, Elias, W & Lombaerts, K. 2015. Adult visitors in museum learning environments. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 191:106. [ Links ]

De Beer, D. 2020. The first Klein Karoo National Arts Festival virtual gallery is visual feast. [O]. Available: https://debeernecessities.com/2020/07/08/the-first-klein-karoo-national-arts-festival-virtual-gallery-is-visual-feast/ Accessed 12 July 2020. [ Links ]

DeWitt, C. 2015. Clare McAndrew explains how she prepared the TEFAF art market report. [O]. Available: http://news.artnet.com/market/clare-mcandrew-on-the-tefaf-report-274279 Accessed 10 November 2021. [ Links ]

Dewey, J. 1959 [1934]. Art as experience. New York: Capricorn Books. [ Links ]

Dorner, A. 1947 [1958]. The way beyond 'Art'. New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Egan, K. 2018. A brief guide to imaginative education. [O]. Available: https://ierg.ca/about-us/a-brief-guide-to-imaginative-education/ Accessed 15 March 2022. [ Links ]

Eloff, H. 2020. The 2021 Klein Karoo National Arts Festival postponed due to Covid-19. [O]. Available: https://www.news24.com/channel/arts/the-2021-klein-karoo-national-arts-festival-postponed-due-to-covid-19-20201218 Accessed 15 March 2022. [ Links ]

Erasmus, LJJ, Saayman, M, Saayman, A, Kruger, M, Viviers, P, Slabbert, E & Oberholzer, S. 2010. The socio-economic impact of visitors to the ABSA KKNK in Oudtshoorn 2010. Potchefstroom. Unpublished Institute for Tourism and Leisure Studies Report. [ Links ]

Falk JH, & Dierking, LD. 1992. The museum experience. Washington D.C.: Whalesback Books. [ Links ]

Greene, M. 2001. Variations on a Blue Guitar: The Lincoln Center Institute lectures on aesthetic education. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Hydén, LC. 2013. Towards an embodied theory of narrative and storytelling, in The travelling concepts of narrative, edited by M Hyvãrinen, M Hatavara and LC Hydén. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company:227-244. [ Links ]

Jackson, PW. 1998. John Dewey and the lessons of art. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Kalfatovic, MR. 2002. Creating a winning online exhibition: A guide for libraries, archives, and museums. London: American Library Association. [ Links ]

King, E, Smith, MP, Wilson, PF & Williams, MA. 2021. Digital responses of UK museum exhibitions to the COVID-19 crisis, March - June 2020. The Museum Journal 64(3):487-504. [ Links ]

KKNK. 2020. First KKNK virtual art gallery opening soon. 16 June. Press Release. [ Links ]

Knutson, K & Crowley, K. 2010. Connecting with art: How families talk about art in a museum setting, in Instructional explanations in the disciplines, edited by MK Stein and L Kucan. New York: Springer:189-206. [ Links ]

Lessing, GE. 1984. Laocoön. An essay on the limits of painting and poetry, translated by E Baltimore. London: John Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Locher, PJ. 2012. Empirical investigation of an aesthetic experience with art, in Aesthetic science: Connecting minds, brains, and experience, edited by AP Shima-mura and SE Palmer. Oxford: Oxford University Press:163-188. [ Links ]

Merleau-Ponty, M. 2012 [1945]. Phenomenology of perception, translated by DA Landes. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

O'Hagan, C. 2020. COVID-19: UNESCO and ICOM concerned about the situation faced by the world's museums. [O]. Available: https://en.unesco.org/news/covid-19-unesco-and-icom-concerned-about-situation-faced-worlds-museums Accessed 15 October 2021. [ Links ]

Parry, R. 2010. The practice of digital heritage and heritage of digital practice, in Museums in a digital age, edited by R Parry. London: Routledge:2-7. [ Links ]

Pierroux, P. 2003. Communicating art in museums. Journal of Museum Education 28(1):3-7. [ Links ]

Pierroux, P. 2009. Newbies and design research: Approaches to designing a learning environment using mobile and social technologies, in Researching mobile learning: Frameworks, methods, and research design, edited by G Vavoula, A Kukulsk-Hulme and N Pachler. Bern: Peter Lang:289-316. [ Links ]

Saaiman, Z, artist, 2022. Interview by author. [Transcript]. 26 February. Oudtshoorn. [ Links ]

Saayman, M, Kruger, M & Erasmus, J. 2012. Lessons in managing the visitor experience at the Klein Karoo National Arts Festival. Journal of Applied Business Research 28(1):81-92. [ Links ]

Saayman, M, Marais, M & Krugell, W. 2010. Measuring success of a wine festival: Is it really that simple? South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation 32(2):95-107. [ Links ]

Simon, RL. 2014. Pedagogy of witnessing: Curatorial practice and the pursuit of social justice. New York: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Steeds, L. 2014. Exhibition. London: MIT Press & Whitechapel Gallery. [ Links ]

Thurman, C. 2012. At large. Reviewing the arts in South Africa. Champaign: Common Ground Publishing LLC. [ Links ]

Thurman, C. 2020. Beauty in the wreckage of the past, present and future. [O]. Available: https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/life/arts-and-entertainment/2020-07-30-chris-thurman-beauty-in-the-wreckage-of-the-past-present-and-future/ Accessed 15 August 2020. [ Links ]

Tröndle, M. Greenwood, S, Bitterli, K & Van den Berg, K. 2014. The effects of curatorial arrangements. Museum Management and Curatorship 29(2):140-173. [ Links ]

Tschacher, W & Tröndle, M. 2011. Embodiment and the arts, in The implications of embodiment: Cognition and communication, edited by W Tschacher and C Bergomi. Exeter: Imprint Academic:253-263 [ Links ]

Tullmann, K. 2017. Experiencing gendered seeing. Southern Journal of Philosophy 55(4):475-499. [ Links ]

Wellington, S & Oliver, G. 2015. Reviewing the digital heritage landscape: The intersection of digital media and museum practice, in The international handbooks of museum studies: Museum practice, edited by C McCarthy. New York: John Wiley & Sons:577-598. [ Links ]

Williams, P. 1987. A brief history of museum computerization. Museum Studies Journal 3(1):58-65. [ Links ]

Winkleman, E. 2017. Selling contemporary art. How to navigate the evolving market. New York: Allworth Press. [ Links ]