Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a23

ARTICLES

Embodied encounters with AntheA Delmotte's performance of Return to Chaos

John Steele

Department of Visual Art, Walter Sisulu University Mthatha, South Africa. jsteele@wsu.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4085-9608 )

ABSTRACT

The theme of embodied engagement with art is explored in relation to the work Return to Chaos, which was created by South African visual artist AntheA Delmotte in 2017. Following a brief introduction to the artist and her works, my own embodied, sensual encounters with Return to Chaos are investigated in order to establish the usefulness, or not, of this way of looking. Delmotte's oeuvre shows that she intertwines painting styles of carefully planned studio based realism with deep trance-state public performance paintings that usually result in relatively unplanned abstract artworks. The latter painting performances are often conducted to the accompaniment of live music. Sound, and the presence of co-performing musicians, play an important role for Delmotte while delving into her subconscious to find colour and imagery that best expresses her emotions at any particular moment while deep trance-state painting. This article goes on to explore the possibility that Delmotte's incremental creation of artworks such as Return to Chaos give insight into colour synaesthesia and cymatic effects in action, and that this artwork shows visible manifestation of deep trance-state feelings embodied by her in response to the music at that particular moment in time. Finally, it is suggested that enrichment offered by analysis of artworks arising from full bodied encounters be extended to include investigations into embodied acts performed by artists as they explore and express their ideas.

Keywords: AfrikaBurn, deep trance-state painting, embodied viewing of art, embodied performance painting, installation art, phenomenological encounters with art.

Introduction

South African artist AntheA Delmotte uniquely intertwines painting styles of studio based realistic portraiture and landscapes rendered with pinpoint accuracy in contrast to public performances of creating unplanned deep trance-state relatively abstract artworks. Her 'art of action' (Meyer 2008:1-5,9) leans on searches for new means of theatre and visual arts expression by the likes of Futurist (circa 1909) and Dada (circa 1916 practitioners as well as the Russian artistic avante garde led by Vsevolod Meyerhold in 1919. Such unconventional art traditions laid foundations for artists such as Jackson Pollock (who created works from his unconscious); the Japanese Gutai-group (established in 1954) whose visual arts acts involved the use of their full body for painting performances in public; and for performances such as Meat Joy by Carolee Schneemann in 1964. Rather than seeking to contextualise Return to Chaos within this trajectory of performance art, I have chosen to take a phenomenological approach to analyse the work that explores my own bodily experiences, and the ways in which I sense Delmotte herself embodies performance painting. This phenomenological approach is founded upon my predilection for autoethnographic methodology wherein 'selfhood, subjectivity, and personal experience [auto] are used to describe, interpret, and represent [graphy] beliefs, practices, and identities of a group...[ethno]' (Adams & Herrmann 2020:2).

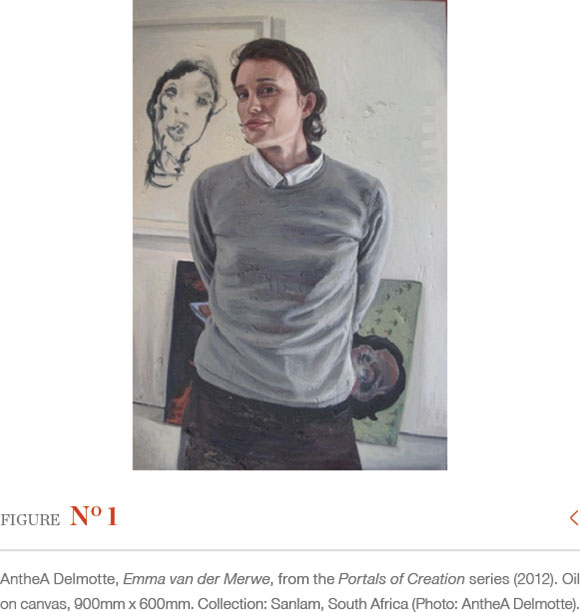

By way of embarking on this project, it is useful to briefly consider some selected studio-based works by Delmotte in order to introduce her prior to engaging directly with ideas about embodiment and exploring embodied encounters with Return to Chaos (2016), and her performances thereof. Delmotte's studio-based works are usually created in peaceful surroundings at home, often in the very early hours of the morning prior to undertaking household and subsistence farming chores, and then again during private and quiet times during the day that are conducive to intense concentration. An awareness of Delmotte's predilection for life-like accuracy first struck me when I saw the image of artist Emma van der Merwe (Figure 1) on the front cover of the March 2013 edition of The South African Art Times. Van der Merwe is interestingly posed, and Delmotte's style of fresh realism is combined with relatively muted tones and quite free brushstrokes in parts of the sweater, skirt and background. This portrait of Emma van der Merwe is part of the open-ended Portals of Creation series that depicts various South African artists in their studio settings.

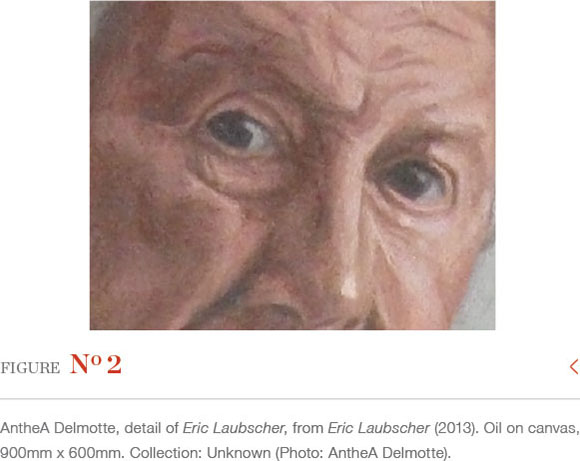

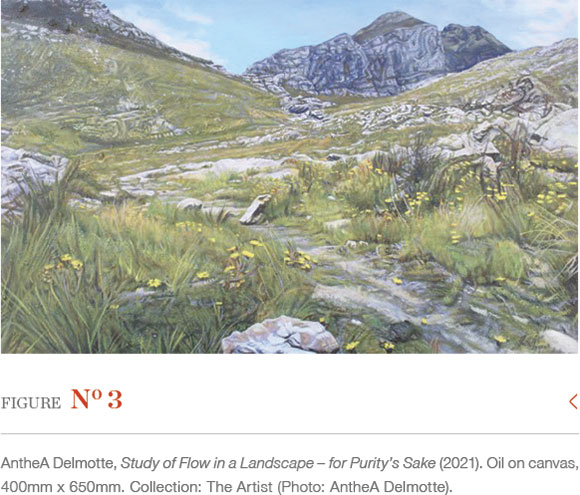

The Portals of Creation series gives insights into artist's studio workspaces rarely viewed, and Delmotte's intense, almost pointillist, approach to realism is evident, for example, in the detail of her rendering of the face of Eric Laubscher (Figure 2). In an email in 2017 she explains that her colour and brushstroke decisions are made 'relative to context...I work in layers, sometimes almost pixilated. Blobs of accurate colour are applied...if one zooms into a work, one can see myriads of colour strokes'. In contrast to minute attention to detail as seen in the Portals of Creation series, depiction of her environment in works such as Study of Flow in a Landscape - for Purity's Sake (Figure 3) can be described as much looser and combines degrees of visual accuracy with an eye for pattern and form. Here I see that her intention is not to express an exact replication of aspects of the environment. Emphasis is placed on interpretation of what is seen rather than aiming to create a painting 'that accurately mirrors...surface reality' (Johnson 2013:482).

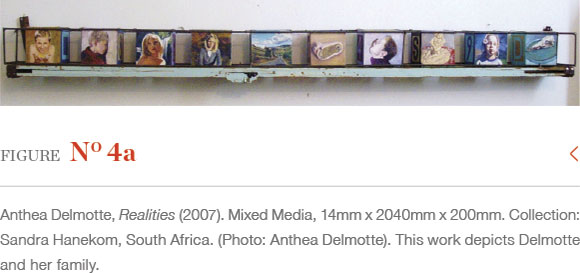

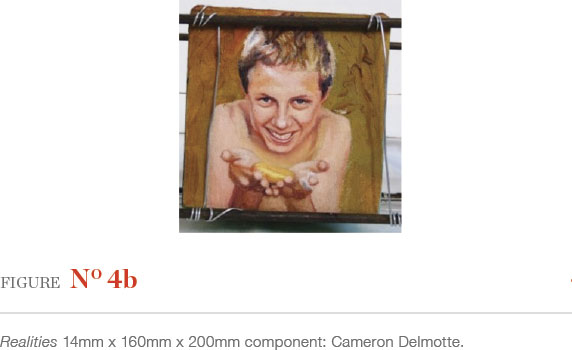

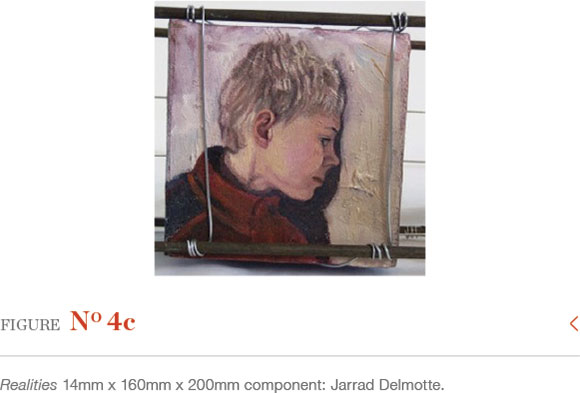

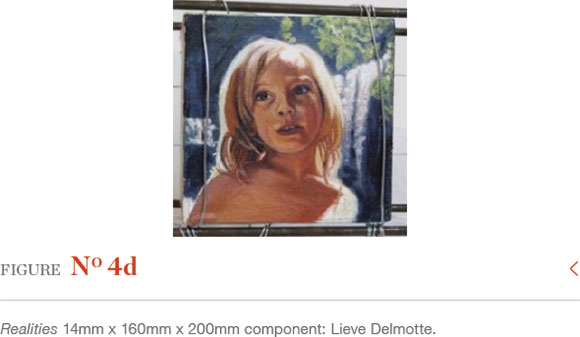

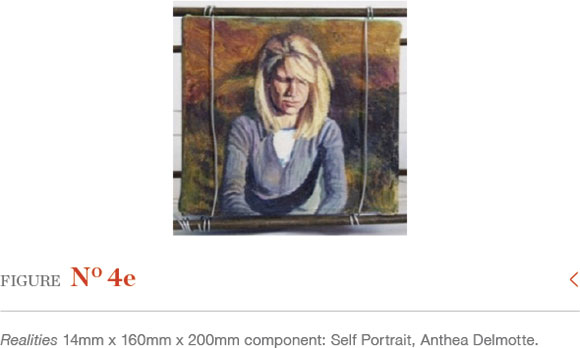

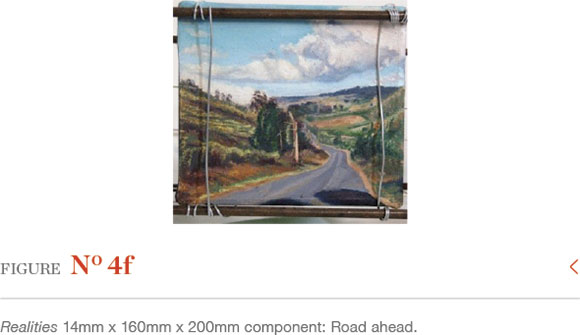

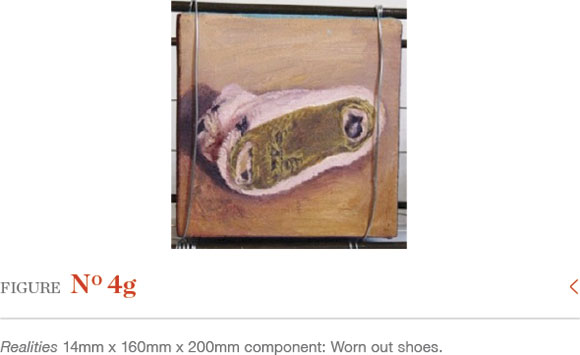

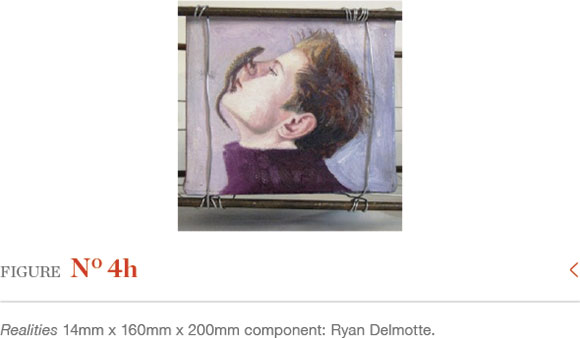

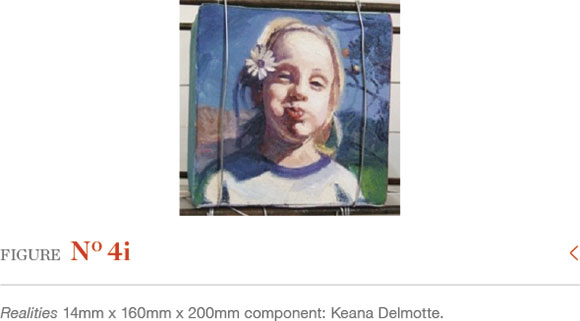

Delmotte's search for avenues for creative expression is evident in both her two and three-dimensional artworks. The three-dimensional work Realities (Figure 4), for example, was created in 2007 during the time of divorce from a marriage characterised by misogynistic cruelty and abuse on the part of her then husband. This work is made up of ten collectively mounted individually painted 160mm x 200mm blocks of wood, much like some educational alphabet blocks played with by children. These blocks show accurately depicted and finely detailed portraits of herself and each of her five children, as well as some other items of symbolic importance. The overall feeling is rather introspective and melancholic, even though two of her children are shown as being encouragingly cheerful and playful despite the circumstances. The centrally placed landscape section, which features swathes of fertile green, perhaps hopefully, suggests a way to live in harmony with people and nature, rather than in conflict with oppressive patriarchy. This sense of muted optimism is emphasised by Delmotte in the way that she has chosen to depict the sky using relatively large sections of harmonious turquoise, despite it being a cloudy day. It is also noticeable that colours and tones, realistically rendered, are nevertheless quite subdued throughout, as befits times of self-examination and transition.

In contrast, Delmotte's works that have emerged during self-induced deep trance-state are relatively abstract and iconographically unpredictable. For the purposes of this article, deep trance-state is differentiated from states of light trance, which can be thought of as 'a state of flow involving total absorption in process' (Beard 2015:353). In discussion during an interview in 2016 it emerged that Delmotte's ritual preparations prior to painting performances are geared towards finding moments of inner quiet and calm that in turn encourage openness to unfettered expression of subconscious urges. She seems to experience deep trance-state painting events in ways that combine flow with experiences of deeper immersion into her psyche, and the act of performance painting itself becomes a form of ritual emotional and psychological unbundling. Viewed clinically, Delmotte's entering into trance as an altered state of consciousness is likely to 'involve a [voluntary] shift from the normally dominant left analytical to the right experiential mode of self-experience, and from the normally dominant anterior prefrontal to the posterior somatosensory mode' in her brain (Flor-Henry, Shapiro & Sombrun 2017:2). These authors also note that such intentional entering into altered states of consciousness are often 'characterised by lucid but narrowed awareness of physical surroundings, expanded inner imagery, modified somatosensory processing, altered sense of self [and can include] an experience of spiritual travel' (Flor-Henry et al. 2017:5).

Delmotte uses her combination of art, ritual and trance to enter what Barbara Bickel (2020:xv) calls 'spaces of the in-between...liminal realms...a non-place [that] holds the mysteries that oblige our human curiosity to inquire, learn and unlearn while simultaneously frightening us'. When viewed through this lens, Delmotte's performances move out of the ordinary into subconscious extraordinary exploration of previously unknown somatosensorially driven visual arts expression. Bickel (2020:50,51), herself a practitioner of trance based visual arts exploration, points out that trance has a profound and extensive 'presence in the arts, in particular in Surrealist, avante garde art, and contemporary experimental film, sound, electronic and performance art'. This researcher cites Katherine Dunham, Maya Deren, Hélène Cixous, Shirin Neshat, Karen Finley and Marina Abramovic as also being amongst women artists who draw on trance as part of their creative practices. Trance artist Karen Finley's, for example, performance paints 'psychic portraits of people...and describes her embodied performances on stage as very exhausting and draining as she is called into a...trance state' (Bickel 2020:84).

Maria Almena (2018:198,199) suggests that some trance based visual artists 'use creative processes to engage the unconscious, archetypes, divinity, collective unconscious, paranormal realms and entities, the inner world and experiences of the sacred'. Interestingly, Dana Calanan (2021:9,10) relates that it can take 'only nine seconds' for her to enter into self-induced trance prior to immersion in creative practice. She relates further that entry into such altered states of consciousness, in her own practice, is achieved in the context of 'drumming rituals.. .the purpose of which is to enable the practitioner to vibrate to a higher [different] state of consciousness'.

David Whish-Wilson (2009:85) characterises the creative trance state as one of 'narrowing of focus with a lessening of external distraction, and subsequent heightening of concentration and imagination...[wherein we become] deterritorialised, and reterritorialised by an openness to experience, knowledge, and information'. The depth and extent of trance experienced by Delmotte varies. She indicated in the 2016 interview that she feels that her deep trance-states extend to including a degree of automatism, as is thought to have been 'experienced by some Surrealists and Expressionists' (Forcen 2013:9). She does not, however, experience full automatism of the type described, for example, by Gertrude Stein1 who had little control of her trance-state writings (Powers 2014:23).

In the interview of 2016 Delmotte also explained that she first thought of deep trance-state performance painting to live music while experiencing whole body immersion in music and musician energies while moving about in the midst of the Cape Town City Orchestra while taking photographs for a forthcoming series of artworks featuring musicians. Sensations throughout her body were immense and intense, and she realised that these energies could be channelled as catalysts into her own visual arts explorations.

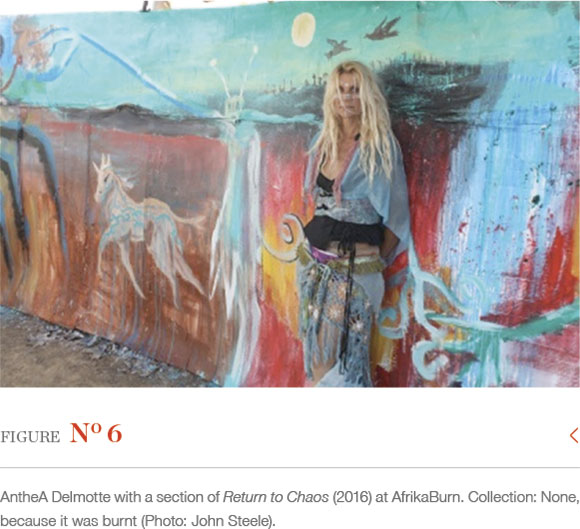

The mural I am (Figure 5), created in 2011, is Delmotte's first deep trance-state painting created to live music performed by alternative music band Croak, featuring vocals by Martinique Matinino du Toit. It provided a sufficiently fruitful experience for Delmotte to want to pursue this avenue of expression further, resulting in collaborations such as I am the Creature (2013), My Bruttar (2014), Organism (2015), Return to Chaos (2016) (Figure 6), Transformation of Things2 (2017), Alter (2017), and others. This article focuses on my embodied experiencing of Return to Chaos (2016) because that is the performance artwork which I have experienced most profoundly.

Embodiment as a way of looking

I have previously tended to describe my autoethnographical and directly personal way of approaching and reporting on research as being based on the position that 'there is no real neutrality in...historical research' (Mifflin 2009:381). I prefer friendly and participatory engagement with artists and their works as a mode of research and have, for example, followed the lead of sociologist Karen Halnon (2006:33) who talks of having absorbed herself in the 'hedonistic ecstasy' of heavy metal music, thereby 'increasing [the] validity of [her] report'. Now, Jenni Lauwrens (2014:xiv) has usefully elucidated a position that acknowledges 'a person's embodied and engaged experience.does not simply contribute to, but rather has primacy and authority in encounters with art' as a point of departure.

A challenge for me has always been to find academically sensible methods with which to explore my immersion in subject matter and to articulate findings in ways that advance art historiography. It is thus with great interest that I am embarking on this adventure of taking an embodied and engaged look at the artwork Return to Chaos and performance thereof by Delmotte. In implementing this embodied analysis, I explore the viability of this approach for future engagements with artists and artworks. It must be noted that Lauwrens (2014:xiii) has extensively discussed the 'limitations of traditional notions regarding aesthetic spectatorship' and scholarship. She has argued in favour of 'embodied and sensual engagement' that approaches art 'through the lenses of the sensory turn, the pictorial turn, the corporeal turn, empathy theory, affect theory, phenomenology and aesthetic embodiment' (Lauwrens 2014:xiii). I accept this position as valid for immediate purposes. Thus, rather than engaging with the finer nuances of how she arrived at this standpoint, I now proceed to explore embodiment as a concept, and how this can be applied.

Lauwrens (2014:152) suggests that 'embodiment refers to the human person as a unified body/mind entity whose various modes of being cannot be localised' and enables 'conversation around embodied interaction with art'. Significantly, such interaction 'explores realms of human being or wholeness beyond the five senses and approaches art as a "performance...communion" (Dufrenne 1973 [1953):15,228), "transaction" (Berleant 1970:88) and "event" (Massumi 1995) that unfolds between the body of the spectator and art' (Lauwrens 2014:378). This fully participatory position enables the broadening of horizons for the investigation and recounting of findings within the context of art historical research.

Just to what extent this potential can be realised by me is the subject of the forthcoming sections. To this end, rather than attempting disinterested distance from my subject matter by disavowing feelings and sensations, I fully embrace the opportunity to recount and reflect upon visual and other experiences of reciprocity between my whole being and the artwork, thereby assessing and expressing more than what just my eyes can see. Thus, Return to Chaos is explored primarily as an experience, thereby establishing that an embodied viewer feels a variety of sensations that arise from engagement with both the material and associative aspects of the artwork.

Then, looking at aspects of performance painting the main "canvas" - more of which later - surface of this installation during the course of a week, I investigate aspects of potential significances that emerge when my encounters are reflected upon. Finally, it is shown that first-hand involvement by all senses with an artwork, or visual arts event, gives authenticity and scholarly substance to recounting of such an embodied viewing.

Embodiment and Return to Chaos

The participatory installation Return to Chaos was created by Delmotte for AfrikaBurn 2016. This annual event takes place for a week in Autumn and is located in desertlike conditions in the Tankwa Karoo, overlooked by the Cederberg mountains in the west. AfrikaBurn has been conceptualised 'as a large site-specific interactive. land art event geared towards experientially celebrating community and ephemerality, while also providing a setting for individuals and groups to articulate creative ideas within an organisationally enabling environment' (Steele 2019:63). In 2019, for example, AfrikaBurn hosted and curated 72 registered installation and other artworks created by artists from all over the world, which were enjoyed by approximately 11,700 participants (Steele 2019:72,73).

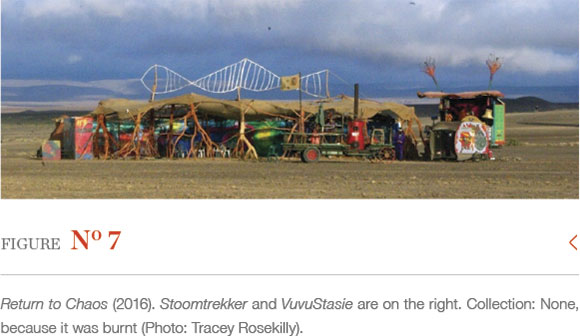

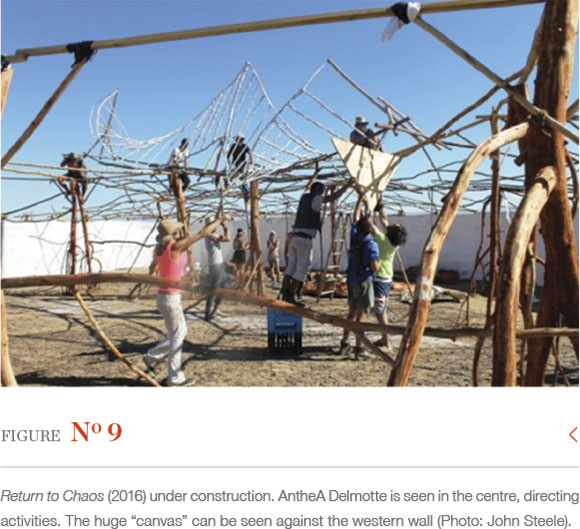

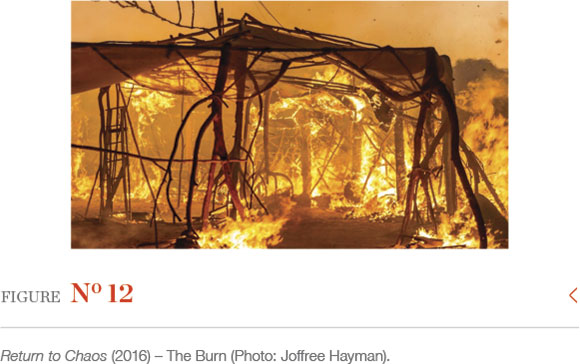

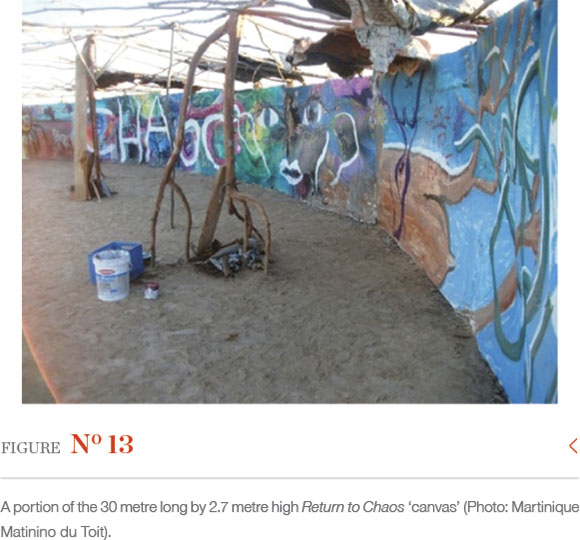

On-site construction of the installation Return to Chaos began on 11 April, then the "canvas" was a deep trance-state performance painted for a week - each evening for about an hour just before sunset - before sacrificial torching and burning to the ground at sunset on Saturday 30 April. This approximately 120 square metre installation was mainly made up of quite widely placed uprights joined by crossmembers at asymmetrical intervals (Figure 7). The structure was almost entirely open to the elements except for the semi-circular western side which was occupied by the approximately 30 metre long by 2.7 metre high giant "canvas".

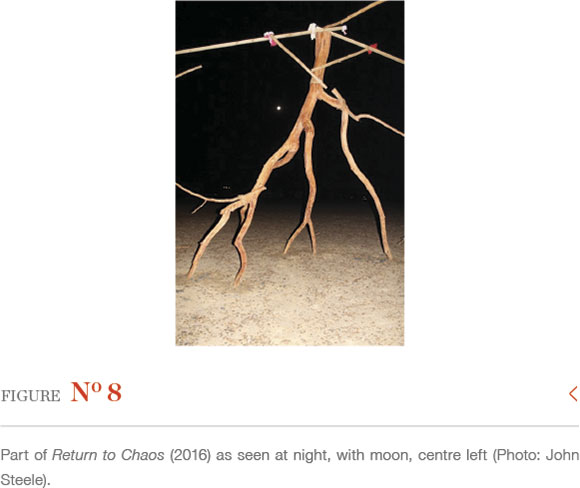

I arrived at AfrikaBurn on Saturday 23 April. That evening, after setting up camp, I walked out into the vast dusty nearly 1.5 square kilometre Binnekring (see Steele 2019 for "town planning" details and layout) and began to take a look at some of the dozens of installations set against the stark beauty of a crisp semi-desert sunset. As dusk turned to darkness I eventually found Return to Chaos. I felt as if I was entering into a wintry forest of trees without leaves, and it was only after a while that I realised that the trees - not indigenous to South Africa - were erected upside down (Figure 8). Even though I reached out and touched many of the dusty trees as I made my way between them, it felt eerie by torchlight, almost as if the trees were marching across the semi-desert floor. It is only in retrospect that I realise I was using my whole body and a range of senses as a means of research, thereby experiencing the 'contingent nature of [embodied] situated experience' (Joy & Sherry 2003:261). I could not only smell and taste the ubiquitous Karoo dust but could also smell a vague damp glue type odour and it was only as I went deeper into this mysterious structure that I realised that the entire western wall had been closed off with strong cardboard and made into the huge blank "canvas" surface that would be used for performance painting in due course. I sat down next to this wall that was still rather damp - taking shelter from the cool night breeze - and with only a nearly full moon for light, I experienced an entire body shiver then felt an upwelling of delight at having come across such an "out of this world" and impossible to fathom space. I was on my own and knew I would have to wait until morning to meet Delmotte while she worked at putting the finishing touches to this installation (Figure 9) to find out more.

Lauwrens (2014:255) suggests that the phenomenological approach to art historical analysis such as my recounting above engages with Return to Chaos 'as a material encounter that demanded affective and, by extension, emotional responses'. Acknowledging both my body and being able to move within and touch some of the "body" components of this installation speaks of the aspect of embodiment that embraces 'our sense of being in a body and [being] oriented in space' (Csordas 1994:5). In this regard Lauwrens (2014:259) observes that 'a person's mobile interaction with the unfolding environment or expanding field through muscular effort and movement (kinaesthesia) is a meaningful part of our experience of land art'. This observation can be extended to include Return to Chaos which requires seeing, entering, exploring, smelling, touching, hearing the breeze scythe through the upside-down trees, and even tasting some of the ubiquitous dust that is always in the air at AfrikaBurn. Embodiment thus pertains to acknowledging the researcher as a whole body-mind being whose encounter with an artwork becomes a recounting and assessment of all inputs received by all senses.

Up to this point my sensual experience of Return to Chaos has been described as a way of expressing some embodied significances that are associated with this work. Next, I explore some of these matters further by engaging with an analysis of my experience of this installation and its usage by daylight, including those of live music and performance painting events. In the guidebook handed out at the AfrikaBurn entrance gate it is explained that Return to Chaos references ideas about mutating genetic order within universal chaos and randomness, and was conceived as an installation that 'is your original cave where you explore your core of flow through music, dance, visuals, and the mind' (AfrikaBurn WTF Guide 2016:27). The search for significance is further enhanced by taking into account the 'empathetic relationship occurring between.[what is seen] and an embodied viewer' as well as 'that a person's sensuous and affective experiences of art must be taken seriously as a meaningful dimension of the critical potential of art' (Lauwrens 2014:265,269-270).

Empathetic responsiveness and projection between individuals, others, and the material environment allows for close connection between all participants. This potentially interoceptive empathic connection can arouse in individuals a sense of a changing 'inner bodily state' (Esrock 2010:228). Such own inner body changes can be extensive and may include, for example, 'feelings of pain, temperature, itch, sensual touch, muscular and visceral sensations, vasomotor activity, hunger [and] thirst' (Craig 2003:500). Freedberg and Gallese (2007:199) have found that the 'empathetic power of images [artworks and performance thereof]...has a precise and definable material basis in the brain'. When one views and experiences an activity with others empathetically it may happen that 'the same neural circuitry is stimulated in the viewer's brain as in the one performing the action' and that 'when looking at art one engages somatically with the character of the image - the visible traces of an artist's gestures' (Lauwrens 2018:89).

At AfrikaBurn in 2016 (Steele 2016:144-146) I empathetically experienced Delmotte's deep trance-state painting performances with her each evening, also recording some of my impressions and experiences in a notebook and by means of photographs. These performances usually lasted between 40 and 80 minutes, and by the end of this week the entire 30 metre long by 2.7 metre high "canvas" was packed with imagery and interpenetrating colour zones. Music of various genres was crucial to each performance and usually commenced less than an hour before she began painting. On the first three evenings Attie Jantjie Basson was the DJ who played heavy metal and sludgy grunge music by the likes of Tool, Lacuna Coil, Rammstein, System of a Down, as well as songs such as Black Hole Sun by Soundgarden. Regarding his choice of music, Basson in a 2016 interview commented that 'the deep darkness of some of this music also carries essences of incomprehensible beauty and life, thereby exploring many of the emotions being experienced while [Delmotte] is painting'. During the following three performances on consecutive evenings Delmotte trance-state painted to live classical rock played by violinist Luca Hart, as well as to alternative dark pop/art rock sounds of Martinique Matinino du Toit, and to instrumental ghost rock played by OhGod.

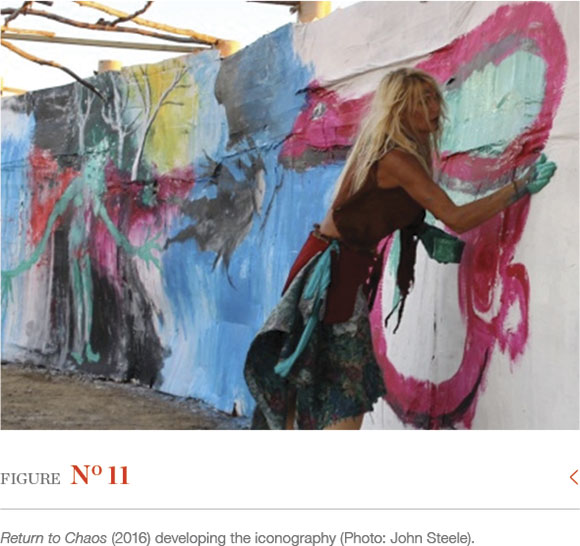

Prior to commencement, each evening Delmotte placed brushes, sponges and any other tools close to each other, within easy reach, alongside open cans of acrylic paint and containers of water. Once started and moving to the rhythm of the music, she would usually energetically block out gesturalist colour zones that served as holding spaces for shapes that emerged as aroused by the music and her subconsciousness. Times of musical crescendos seemed to encourage dervishlike dancing and passages of frenzied paint application, by means of throwing, or with sponge and brush, or directly by fingers and hands (Figure 10). These were contrasted with sustained sensually rhythmic movements and painting surges, which in turn were occasionally interspersed by contemplative and seemingly serene interludes when particular areas of the emerging artwork were being considered or, for example, when just the application of colour for the sheer joy and tactile intensity of that moment was being dwelt in and savoured. Sometimes rapidly performed short and intense brush or hand-strokes quickly filled spaces with colour, and on other occasions, long swooping actions expressed new emotions, occasionally also linking images to each other (Figure 11).

Music during these performances energised Delmotte and served to bring together performer/s and audience/participants into a collective consciousness. Selim Bulut (2013:2) has explained this sense of collectivity as arising with music when 'everybody in a.[space] is focussed on one audio source, then brainwaves are synchronising, putting everybody in a similar state of mind'. This collective consciousness encourages empathy between Delmotte, the musicians, and between all participants. I also felt an uncanny, almost uncomfortable sensation of being drawn into a trance-state of mesmerised participatory proximity with Delmotte. I experienced, for example, moments of her frenzied activity raising my own body temperature and heartbeat. Furthermore, her full-bodied physical throwing of herself into the creative process variously created sensations of magnetic enchantment as well as intense feelings of discomfort and uneasiness, the latter perhaps fuelled by my dread of the unknown. Extreme apprehension and tension could, without warning, be followed by serene moments of calm and sensual instants of revelling in the joy of, for example, pure juicy colour squelching from open hand onto the "canvas".

Lauwrens (2014:274) confirms that 'viewers...[of art] may empathetically or imaginatively.experience [delightful or] unpleasant, even painful sensation somatically, deep within our bodies, for we have merged with that which we see'. This notion of an embodied viewer empathetically merging with an artwork or performance thereof foregrounds vision, touch, hearing, smell and possibly even taste on occasions, as being potentially of equal significance. Such embodied perception enables actual experiencing by all senses of what is occurring in the creative performance process as well as in the actual artwork itself, enabling full participation rather than distanced observing. Viewed in this light, my embodied, experiential encounters with Delmotte's painting performance of returning to chaos within the Return to Chaos installation can arouse seemingly infinite possibilities for reflection and assessment.

The question then arises about how to approach considering these embodied experiences so as to enable further critical reflection thereon? Lauwrens (2014:320321) usefully calls on the notion of a 'phenomenology of aesthetic experience' that draws attention to the 'reciprocal relationship between subject [me, the actively engaged participant] and object [Delmotte and the installation]' as being 'helpful in advancing a critical reflection on their dialogical arrangement'. In order to achieve this, my own embodied participation in the events as they unfolded in Return to Chaos - not only my intellectual experience thereof - require further investigation. Thus, significances arise from intimate interpersonal and inter-object reciprocation and intermingled influences combined with perceptions aroused by imagery, content, and perceived artistic intent. All of these are influenced by individual psychological states, imagination, and site specific environmental factors as well as personal and collective cultural context.

These factors include recognising that the surroundings in which I met up with Return to Chaos 'contribute to the "complex patterns of reciprocity" or the "experiential continuity" that emerges' (Lauwrens 2014:350). Thus the intensely creative and supportive environment of AfrikaBurn as a site specific land art event is a very significant backdrop for further establishing meaningful embodied engagement with Return to Chaos. Within this installation itself the spatial arrangement of components such as, for example, the upside down trees and the "canvas" western wall also serve to provide focus and direct how I move within the installation, thereby activating specific ways of encountering and experiencing this work. Another way in which Return to Chaos mediates how I perceive myself within and reacting to the installation is that there is an easy flow between all physical components and so I feel intimately connected to Delmotte's painting performance, the musicians, and all the other people within this space. This awareness of being conjoined with others is a very significant component, and grows steadily each evening as the music tempo and deep trance-state performance intensifies. Moving about and engaging joyfully with various dancers and curious onlookers became almost as significant an activity as being fully immersed in Delmotte's performance painting within this installation.

Return to Chaos is in turn located within the wider context of more than 70 other installations strategically placed in the vast expanse of the AfrikaBurn Binnekring. A significant factor here is that meaning making is heightened by the presence of others - and other installation artworks - because I am not an insulated person on my own, but am rather conjoined with others in our collectively embodied experiencing of the spaces, people and events. We are inescapably entangled, and bodily absorbed by Return to Chaos and the Binnekring environment. From my autoethnographic point of view, I experience that it is the AfrikaBurn safe-space culture, situated as it is within its particular social, historical, economic and political context, which is both enabling and nurturing of sublime like-mindedness within the infinite diversity of our various participations. Thus, it is the expanded and sensorially aware embodied conception of this installation as a place of liberating individual and collective creative performance that helps me fleetingly engage meaningfully with the existence of Return to Chaos, prior to the entire work in all its multitude of facets being sacrificially burned to ash in the Binnekring (Figure 12).

Meaningfulness arising from Delmotte's performance painting and my embodied recounting thereof includes that I have come to realise that being part of and thus possibly even co-creating Return to Chaos appeals to the core of my being. I have also come to cherish and deeply value the sharing of experience with her, arising from our empathetic relationship over the duration of this event. This sense of intense interconnectivity is enhanced by music and the actively creative participatory presence of thousands of other AfrikaBurners, all within a carefully curated setting of Karoo semi-desert vastness.

It has been learnt in the processes of co-creating - by virtue of my presence -Return to Chaos and by writing about it that engaging with a phenomenological approach that somatically emphasises my bodily experiences of this artwork enables heartfelt analysis. Furthermore, while communicating by email and as I write this article, I even begin to humbly wonder whether Delmotte and I continue as co-creators of sorts, with my interest in this work contributing to sustaining its presence, albeit in altered form?

My intensely personal embodied analysis of Delmotte's performance painting of Return to Chaos makes no claim to universality, or even to articulating experiences that may have been encountered by others, including of those who participated. My investigation also does not engage with a formal analysis of artwork iconography (Figure 13), nor does it engage with accurate and full social and cultural historiography of neither Delmotte nor AfrikaBurn. I do nonetheless acknowledge that these factors have relevance and are variously important, but given my current focus on an embodied encounter with Return to Chaos I accept that at this stage these would need to be assessed as potentially worthwhile topics for a different paper, and engaged with accordingly.

Delmotte: Embodiment in action

It has been useful and instructive for me to consider Return to Chaos from an embodied point of view, but I think even further value can be found by considering some of the extent of embodiment Delmotte herself expresses as she explores and articulates her ideas. It is useful to note at the outset of this section that most artists embody some or other idea in order to create a work, which then is an embodiment of those ideas. Artworks can thus be described as 'embodied imagination' (Joy & Sherry 2003:259). I am of the opinion that Delmotte, however, takes embodiment a few steps further by actively engaging with self-induced states of deep trance while public performance painting to music. She relinquishes intentionality with regard to colour and imagery in favour of visually expressing unbidden subconscious intensely felt bodily urges. Creating deep trance-state works provides a vehicle for her to expand possibilities for visual arts expression. Performing such works enables her to let go and to both emotionally and physically experience and feel with intense passion. In such situations deep trance facilitates whole-body awareness, cuts out extraneous stimuli and facilitates focus for Delmotte and for the participating "audience", to varying degrees.

Giving a brief overview of Delmotte's "conventional" artistic practices at the outset of this article enabled establishing her home studio as a quiet space for uninterrupted painting praxis, and well as her predilection for mimetic accuracy, if so desired. Yet, even under normal circumstances, in her studio she is inclined to dramatic experiential responses to such ordinary events such as, for example, opening a new tube of paint. In an email in 2016 she relates that 'from as early as I can remember, colour has always evoked passion in me.it makes me vibrate.it is impossible to explain my excitement sometimes when I've just pressed out colourful blobs from the tubes'. Her whole body and being becomes even more alive to potential visual and experiential possibilities when deep trance-state performance painting. In an email in 2016 she has explained that part of what happens is that she 'regularly experience^] colour synaesthesia...which heightens emotional intensity while painting'. Generally speaking, synaesthesia happens when, for instance, 'a particular stimulation in a given sensory modality (e.g., touch, music) or cognitive process (e.g., computing) automatically triggers additional experiences in one or several other unstimulated domains (e.g., vision, emotion)' (Safran & Sanda 2015:36).

Delmotte relates that in such circumstances, sounds and music are intensely experienced by her as colours, which influences her colour choices. Music also adds greater force and presence to colours that are already in use. Delmotte in the email in 2016 also relates that, for example, higher pitches tend to 'influence colour choices towards lighter or brighter tones [being used] and low-pitched sounds towards darker tones.there is definitely an instinctive intermixing and linking between colour, feeling, sound and movement'. Thus, specific sounds and situations encourage particular colour and tonal choices in certain circumstances because those colours are what is being experienced. All colours affect her equally powerfully in different ways in different circumstances, but turquoise has been singled out by her for special mention. In the email in 2016 she also relates that 'turquoise resonates with me, almost as if I vibrate on the same frequency.all colours evoke feelings of ups and downs, like on a graph, but, somehow, turquoise is a straightish line on that graph.harmony.inner and outer peace'. Delmotte has also reported in the email in 2016 that 'intensity of posture and rapidity of hand movements' also get influenced by times of deep synaesthesia.

By deliberately engaging with deep trance-state painting performances, she actively seeks even greater intensity of creative experience, and relates that with an appreciative audience and, ideally, a live band of co-performers, she gets immersed 'in colour, body and sound, and becomes exhilarated, feeling like there is something explosive inside, like inner boiling bubbles, going ever faster. Yet sometimes everything also dramatically slows down' (Steele 2016:147). Interestingly, cymatic researchers that explore intrinsic relationships between sound and matter seem to give further insight into Delmotte's desire for experimentation with, and hunger for, deep trance-state painting experiences. Such studies show that there are effects of sound vibrations and frequencies on all matter, including on humans (Gingrich et al. 2013:332). Cymatics is a method of making sound visible by propagating it, for example, from any source through a medium such as water in a vessel or sand on a plate. The medium can be seen to vibrate in places and be still in others, forming ever-changing symmetrical nodal points and lines, thereby enabling sound to be experienced visually (Lewis 2010:5,8,12). Thus, because sound can be experienced as vibrations as well as aurally, it becomes possible to pinpoint part of what Delmotte seeks to experience and then express visually when she talks of feeling vibrations and bubbling excitement. The cymatic impact of live music on Delmotte is at least partly enabled by the 'high percentage of water content of humans' (Watson et al. 1980:27). Cymatic impressions of energies on band members as well as the audience and artist can thus bring about powerful synergies of creative joint purpose, embodied visually by Delmotte.

Tentative conclusions

Exploring the theme of embodied engagement with art in relation to the installation Return to Chaos has shown that there are useful ways of looking at art that engage with whole body feeling, thereby enhancing art historiography. This method departs from ocularcentric ways of writing about art without denying the value of vision. As a result of this way of looking and experiencing, so-called academic distance is denied in favour of recounting moments of full bodied, multi-sensorial participatory immersion in the fullness of this particular installation, and artworks in general. All my senses become engaged as I intimately consider Return to Chaos, thereby becoming an active experiencer rather than being a distanced spectator with pen, paper and camera, attempting to dispassionately record proceedings and eventually make omniscient aesthetic pronouncements.

As suggested by Lauwrens (2014:374), possibilities are now opened up for texturally enriched viewpoints enabled by acknowledging my 'affective multisensorial body... in relation to what...[I] see'. This rethinking of how to approach aesthetic experience embraces my embodiment and sense of self as a self-reflexive 'unified body-mind entity' who actively enjoys 'the intersubjective intertwining of a subject and an object, things and persons, mind and body, places and being in the world' (Lauwrens 2014:376). This viewpoint also opens up a reality that Return to Chaos, and artworks in general, can be regarded as performing themselves, rather than as inert matter.

Recounting my embodied interactions with Return to Chaos has in turn given access to recognition of Delmotte as both a primary creator of the installation and deep trance-state performance painting sessions, as well as that she is co-creator of these events with musicians and audiences. By engaging so intensely with co-creativity, in deep state of trance mode, she thus actively undermines the sole-authorship, iconographic and aesthetic omniscience usually accorded to artists.

Notes

1 . Gertrude Stein wrote Tender Buttons in 1914 under circumstances that included automatism. It is read here by Cori Samuels: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7k9yK7DjUMw. She also wrote Look and Long in 1944 under circumstances that included automatism. The movie was produced for TV in 1989 by Jaap Drupstein: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QtD88gZHBVA.

2 . This video of Transformation of things being performed in 2017, with music by Martinique Matinino du Toit, is a good example of a Delmotte trance-state painting performance: https://www.facebook.com/delmotte.anthea/videos/the-transformation-of-things/454590168454030/.

3 . See cymatics in action at, for example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GtiSCBXbHAg&feature=youtu.be and https://youtu.be/Q3oItpVa9fs

References

AfrikaBurn. 2016. WTF? Guide. Booklet handed out at the entry gate. [ Links ]

Adams, TE & Herrmann, AF. 2020. Expanding our autoethnographic future. Journal of Autoethnography 1(1):1-8. [ Links ]

Almena, M. 2018. Transcendence: Can live performance art in combination with interactive technology induce altered states of consciousness? [O]. Available: https://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/EVA2018.38 Accessed 10 September 2022. [ Links ]

Basson, AJ, musician and DJ. Cape Town. 2016. Interview by author. [Transcript]. 27 April. AfrikaBurn, Tankwa Karoo. [ Links ]

Beard, K. 2015. Theoretically speaking: An interview with Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi on flow theory. Educational Psychology Review 15(1):353-364. [ Links ]

Berleant, A. 1970. The aesthetic field: A phenomenology of aesthetic experience. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas. [ Links ]

Bickel, AB. 2020. Art, ritual, and trance inquiry: Arational learning in an irrational world. Switzerland: Springer Nature. [ Links ]

Bulut, S. 2013. Dancing myself into a trance. [O]. Available http://www.dummymag.com/Features/comment-dancing-myself-into-a-trance Accessed 15 April 2022. [ Links ]

Calanan, DM. 2012. Altered states of consciousness & the creative individual: Breaking the affective thinking skills paradigm. [O]. Available https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1174&context=creativeprojects Accessed 11 August 2022. [ Links ]

Csordas, TJ. 1994. Embodiment and experience: The existential ground of culture and self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Craig, AD. 2003. Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Current Opinion in Neurology 13 (4):500-505. [ Links ]

Delmotte, A, artist. Bo-Piketberg, Western Cape. 2016. Interview by author. [Transcript]. 27 April. AfrikaBurn, Tankwa Karoo. [ Links ]

Delmotte, A. (anthea.art1@gmail.com). 2016/11/29; 2016/12/21 & 2017/01/01. Connecting. Email to J Steele (jsteele@wsu.ac.za). [ Links ]

Dufrenne, M. 1973 [1953]. The phenomenology of aesthetic experience. Translated by ES. Casey. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [ Links ]

Esrock, EJ. Embodying art: The spectator and the living body. Poetics Today 31(2):217-250. [ Links ]

Flor-Henry, P, Shapiro, Y & Sombrun, C. 2017. Brain changes during a shamanic trance: Altered modes of consciousness, hemispheric laterality, and systemic psychobiology. Cogent Psychology 4(1):1-25. [ Links ]

Forcen, C. 2013. Trance and mental pathologies in 20th Century Art. Journal of Humanistic Psychiatry 1(4):7-11. [ Links ]

Freedberg, D & Gallese, V. 2007. Motion, emotion and empathy in aesthetic experience. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11(5):197-203. [ Links ]

Gingrich, O, Renaud, A & Emets, E. 2013. KIMA - A holographic telepresence environment based on cymatic principles. Leonardo 46(4):332-343. [ Links ]

Halnon, KB. 2006. Heavy metal carnival and dis-alienation: The politics of grotesque realism. Symbolic Interaction 29(1):33-48. [ Links ]

Johnson, G. 2013. On the origin(s) of truth in art: Merleau-Ponty, Klee, and Cézanne. Research in Phenomenology 43 (1):475-515. [ Links ]

Joy, A & Sherry, JF. 2003. Speaking of art as embodied imagination: A multisensory approach to understanding aesthetic experience. Journal of Consumer Research 30:259-282. [ Links ]

Lauwrens, J. 2014. Beyond spectatorship: An exploration of embodied engagement with art. PhD Thesis, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. [ Links ]

Lewis, S. 2010. Seeing Sound: Hans Jenny and the Cymatic Atlas. Bachelor of Philosophy Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, USA. [ Links ]

Massumi, B. 1995. The autonomy of affect. Cultural Critique 31(2):83-109. [ Links ]

Meyer, H. 2008. Performance art and its art-historic origins. Extract from the dissertation paper Schmerz als Bild - Leiden und Selbstverletzung in der Performance Art. [O]. Available: http://www.performance-art-research.de/texts/performance-and-its-origins_helge-meyer.pdf Accessed 17th June 2022. [ Links ]

Mifflin, J. 2009. 'Closing the circle': Native American writings in colonial New England, a documentary nexus between acculturation and cultural preservation. American Archivist 72(2):344-82. [ Links ]

Powers, E. 2014. Attention must be paid: Andy Warhol, John Cage and Gertrude Stein. European Journal of American Culture 33(1):5-13. [ Links ]

Safran, A & Sanda, N. 2015. Colour synaesthesia: Insight into perception, emotion, and consciousness. Current Opinion in Neurology 28(1):36-44. [ Links ]

Steele, J. 2016. AntheA Delmotte: Performing temporality and returning to chaos at AfrikaBurn 2016. South African Journal of Art History 31(2):131-153. [ Links ]

Steele, J. 2019. Ephemeropolis: Urban design and performing land art at AfrikaBurn 2019. South African Journal of Art History 34(2):62-83. [ Links ]

Watson, PE, Watson, ID & Batt, RD. 1980. Total body water volumes for adult males and females estimated from simple anthropometric measurements. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 33(1):27-39. [ Links ]

Whish-Wilson, D. 2009. Trance, text and the creative state. Creative Writing: Teaching Theory & Practice 1(1):2040-3356. [ Links ]