Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a22

ARTICLES

Light on loss in new works by Paul Emmanuel

Irene Bronner

Office of the SARChI (South African Research Chair in South African Art and Visual Culture) Chair in Art and Visual Culture, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa ireneb@uj.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1199-9636)

ABSTRACT

Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017, two new works from South African artist Paul Emmanuel's most recent exhibition Substance of Shadows (2021), are examined as depicting rites of passage of memory and mourning, following the recent loss of both Emmanuel's parents. They are discussed in dialogue with the five untitled incised drawings from Emmanuel's 2008 Transitions exhibition, which addressed significant male rites of passage that were also liminal moments in male lives. In rites of passage, the citations, quotations and traces that form a subject's socially constituted body are undone and rearranged. Transitions (5), however, represents the quotidian liminality of commuting and while it is fruitfully interpreted as a metaphor for death, a deeper exploration of this particular rite of passage is held over, this article argues, until Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017. These two works are therefore examined as a continuation of the works of Transitions. Crucially, however, it is proposed that Emmanuel's principal memory engagement in these two works is enacted materially, through his medium of obsolete carbon paper, rather than the exposed photographic paper of Transitions. The ways in which Emmanuel works with carbon paper allows a sensitive embodied exploration of aging and frailty to emerge.

Keywords: Paul Emmanuel, rite of passage, memory, loss, mourning, gender identities, carbon paper.

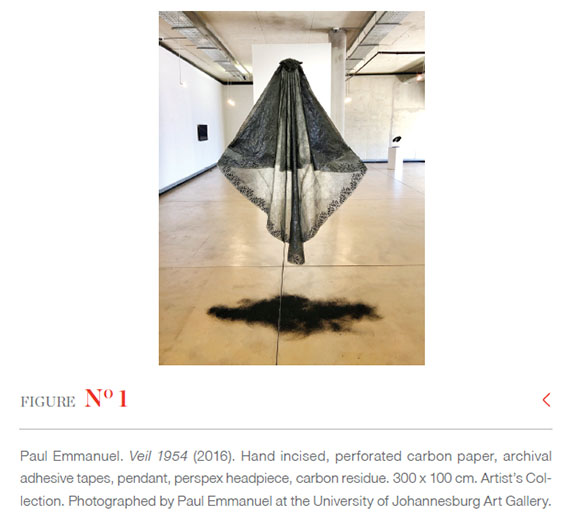

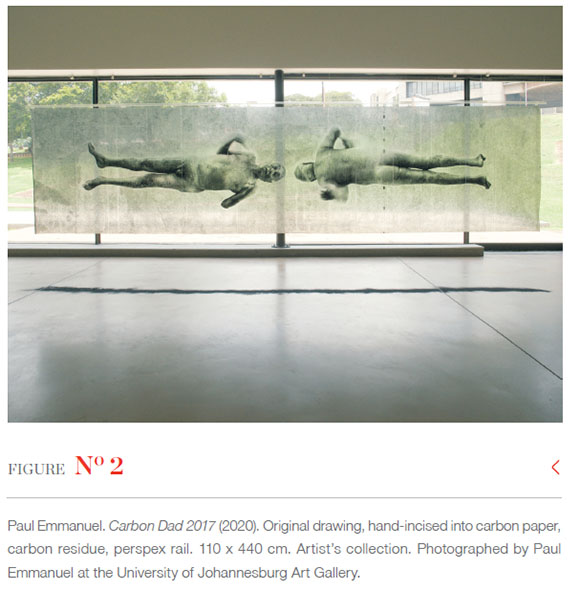

Veil 1954 (2016; Figure 1) and Carbon Dad 2017 (2020; Figure 2) are two key works in Paul Emmanuel's body of work, Substance of Shadows, exhibited at the University of Johannesburg Art Gallery, from 11 September to 2 October 2021.1 The exhibition introduces Emmanuel's use of obsolete carbon paper as a medium, into which he scratches in a manière noire technique.2 Many works are rendered in three-dimensional shapes and suspended as presences - or absences - in the gallery space; all are semi-transparent and skin-like. Substance of Shadows explores, as Emmanuel (2021) writes, 'the tenuous nature of memory' particularly, and personally, in relation to the passing of both the artist's parents in recent years.3 Offering an opportunity therefore for reflection on mourning and grieving, the exhibition also examines male subjectivity formation and militarism, through self-representation and through the sensitive and vulnerable touch for which Emmanuel has come now to be known. His work consistently engages in Annette Kuhn's (2010:6) definition of 'memory work', that is

an active practice of remembering that takes an inquiring attitude towards the past and the activity of its (re)construction through memory. Memory work undercuts assumptions about the transparency or the authenticity of what is remembered, taking it not as 'truth' but as evidence of a particular sort: material for interpretation, to be interrogated, mined, for its meanings and its possibilities.

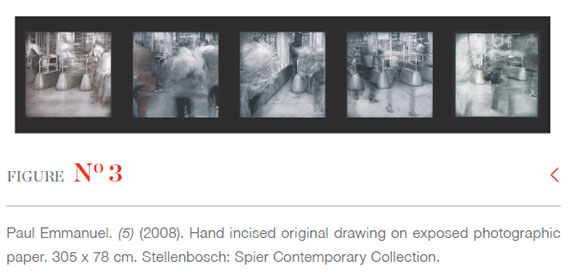

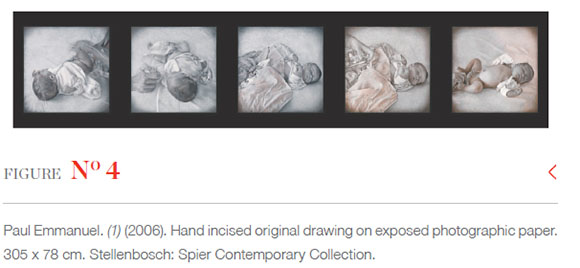

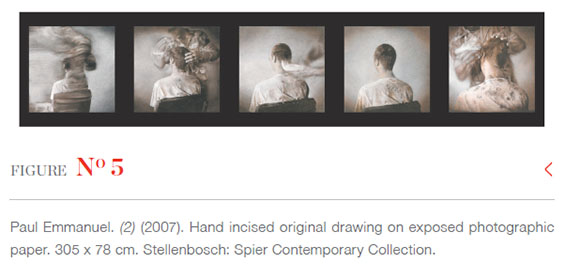

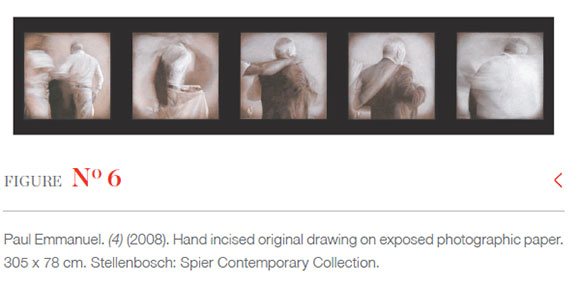

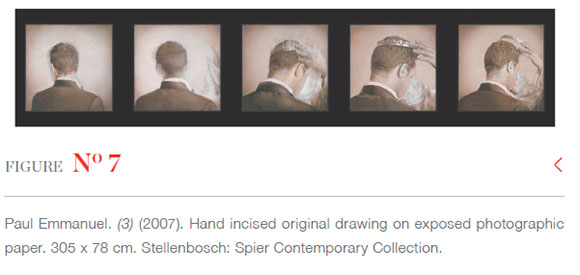

I argue that Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017 appear to dialogue specifically with Emmanuel's body of work Transitions (2008) generally and with Transitions (5) (Figure 3) in particular. The Transitions body of work, which I begin by introducing, consists of five large drawings, scratched into developed or exposed photographic paper, representing three identifiable rites of passage (a circumcision, an army recruit's head shaving, a marriage ceremony) and one sequence that is more ambiguous but nonetheless an assumption of an authoritative role (a middle-aged, heavy-set man being helped on with a jacket as he rises from a dining table). Firstly, I discuss how the artist can be interpreted as interrogating male rites of passage to expose gendered identity as what Judith Butler (2006a:191) names a 'constituted social temporality'. Emmanuel describes himself as challenging conventional expectations about men, by focusing on 'the mundane and ritualized form of their legitimation' (Butler 2006a:191). The fifth and final work - Transitions (5) - is unlike the other four works of the series. While Transitions (1) - (4) depict rites of passage in male identity and represent identifiably male subjects, although anonymous, the fifth work represents the vague presences of people passing through turnstiles at a train station. As a rite of passage, this work may depict the quotidian liminality of commuting and travelling. In the context of the series, however, this interpretation appears rather too superficial and is far more satisfactory, in my view, when read as a metaphor for the final transition or rite of passage that is death and the human life cycle. This is also an interpretation taken by others (Auslander 2020a:[Sp], for instance), although not overtly by the artist himself (Emmanuel 2019:[Sp]). Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017 appear therefore to dialogue with Transitions (5) to the extent that they offer a deeper exploration of the transitions in roles that Emmanuel, and so many others, have undergone as rites of passage with parental loss. I am guided in this by Victor Turner's framework of liminal rites of passage.

Secondly, I discuss in more depth the conceptual ramifications of Emmanuel's maniere noire technique, specifically in relation to loss and memory. I continue thereafter to compare and contrast Emmanuel's use of exposed photographic paper and carbon paper as mediums. I detail how Emmanuel's technique and concept extend into a more bodily register with his use of carbon paper as opposed to exposed photographic paper. I examine Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017 together with Transitions (5) and contend that it is the materiality and medium of the two new works that comes to the fore and that, furthermore, offer material insights into how to find passage through these transitions. Finally, I argue that the consequences of this material embodiment, in line with the artist's own interpretation, are that this material allows the consideration of the psycho-somatic vulnerabilities of human existence, in particular its frailties and aging processes. The possibilities of shrouding and veiling offered by carbon paper as a medium, and Emmanuel's intentional subversion of the iconic Turin Shroud, further engages with the intangible and still mysterious connections between one's sense of self and one's bodily existence. Emmanuel courageously explores his experience of witnessing these connections slowly unravel, with the progress of age and disease. Vulnerability is positioned here as, in Danielle Petherbridge's words, 'a central category through which feminist philosophers [and art- and meaning-makers] have sought to examine the complexity of embodied interdependence' (Petherbridge 2018:56).

Approaching death: Transitions and rites of passage

Five drawings, titled (1), (2), (3), (4) and (5), form part of Emmanuel's exhibition Transitions5 and represent what Emmanuel sees as moments, to degrees more or less formalised, of transitions or rites of passage in male identity. In (1), an infant boy is circumcised by a surgeon (Figure 4); in (2), an army recruit's head is shaved by a barber (Figure 5); in (3), a Maronite Catholic bridegroom is crowned by his priest as part of the marriage ceremony (Figure 7); in (4), a middle-aged man, rising to make a speech, is helped on with his dinner jacket by indistinguishable hands (Figure 6); in (5), people dissolve as they pass through a train station's turnstiles (Figure 3). If the five drawings are read as representing consecutive liminal stages of a man's identity, then the final one, (5), can be seen metaphorically as representing the passage over the threshold into death, the journey "over the river". Emmanuel (cited by Croucamp 2008), however, believes (5) depicts 'dissolution rather than death'. This is appropriate enough, considering that in a rite of passage a subject is conceived as 'neither living nor dead [and also] both living and dead' (Turner 1967:96). Arguably, in this drawing, dissolution is transformation; in all the drawings, the "achievement" of a liminal state is both the process and the intended result, as it is on the suspended transition that the artist invites the viewer to concentrate. In Veil 1954, however, the suspension between life and death, between body and mind or self-awareness, took on another and painful set of meanings for Emmanuel, as he watched his mother succumb to the ravages of Alzheimer's Disease.

Conceptually and technically, Emmanuel has long been concerned with the gender roles which men accept, whether willingly, whether consciously or not, with what happens to a man as he undergoes a transition from one role or state to another, and in how to represent that transition to the viewer. He identifies rites of passage in a range of events, choosing those that, to him, compellingly and visually 'explore how the construction of male identity happens and how it is perpetuated by generations' (Emmanuel 2008:[Sp]). For Emmanuel, all these rites of passage speak to the possibilities and impossibilities of his own life (as a white, queer, gender non-conforming, South African individual, as some of many factors), marking life-changing events that he himself has or could have experienced, might or never will experience (Emmanuel 2009:[Sp]). He re-interprets traditions of and assumptions about gender by, arguably, "staging" the "performativity" of gender. He also examines the racial construct of whiteness as it intersects with masculinities in a South African context, both historically and contemporarily (see Allara 2011). The intersections between whiteness, hetero-normative masculinities, militarism and public memorialisation are engaged with particularly in the Lost Men (ongoing since 2004, see Von Veh 2020).

Emmanuel finds the liminality of subjects during rites of passage to be visual and "visible" representations of temporal and spatial intervals within social rituals that reveal the construction of male identity to be a process. This process is on-going in a manner that may be discussed as 'performative' by referring to philosopher Judith Butler's (1993,2006a) concept of gender identity as the accretive and repeated internalisation of the regulated and regulating norms that produce and govern gendered behaviour. Victor Turner's anthropological research into the liminality that defines subjects during rites of passage is also, I argue, central to understanding the works of Transitions. Emmanuel feels that he works emotionally, conceptually and technically from a point of loss in his attempt to represent contemporary masculine identities in moments of transition and contingency. These moments, for the artist, are characterised by an ambivalent psycho-somatic vulnerability. The works of Transitions provide, I propose, an existing framework within Emmanuel's oeuvre with which to shape an initial and exploratory examination of the two new works, Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017, that speak so powerfully of the final transition in a human life cycle, regardless of gender identification, that of death.

It is worth beginning with a brief review of the concept of liminality in the context of rites of passage by referring to the anthropological research of Victor Turner.5Based upon his observations of the Ndembu of Zambia,6 Turner (1967:94) examines society as a model in which people co-exist in a 'structure of positions' according to (but not exclusively limited to) 'place, state, social position and age'. The periodic changes of state Turner (1967:95) identifies as the 'rite of transition' or 'rite of passage' as indicating and constituting these changes in state or status as well as the entry into a 'new, achieved state'.7 The changes marked include culturally defined life-crises such as birth, puberty, marriage and death, but may accompany any change from one state to another (Turner 1967:94-95). The rite of transition gives 'outward and visible form to an inward and conceptual process' (Turner 1967:96). The rite lays the emphasis on the transition itself, rather than on the states between which it takes place and contains 'few or none of the attributes of the past or coming state' (Turner 1967:96). Turner draws on Arnold van Gennep's identification of three phases in rites of transition: separation (or detachment), margin (or limen) and aggregation (or consummation and reintegration). The separation and aggregation phases are concerned with subjects' detachment from and reintegration into the social structure, in other words, their relationship to the social structure. In the liminal phase, however, subjects are 'unstructured', where '[t]heir condition is one of ambiguity and paradox, a confusion of all the customary categories' (Turner 1967:96). Subjects are 'no longer classified and not yet classified' and 'neither living nor dead [and also] both living and dead' (Turner 1967:96).

It is these transitory ritualised spaces of non-affiliation and liminality that fascinate Emmanuel, he describes them as 'spaces in which a man is in the process of changing his status, with one foot in one world and the other in another' (Emmanuel 2008:[Sp]). In order to consider how Emmanuel expresses these liminal spaces and the characteristics to which he is drawn during these liminal phases, I begin with his comment: 'In all of the drawings, the person undergoing the ritual is anonymous, yet I show the intimate spaces of their bodies, areas reserved for lovers. The drawings are a little voyeuristic; intimate but not intimate' (Emmanuel cited by Bosman 2008:[Sp]). The anonymity of the subjects, or the lack of distinguishing facial features and identity props, can be said to portray Turner's (1967:97) observation that in a liminal rite of passage, the subject has physical but not social existence and cannot, therefore, be recognised by others. There is little or nothing to contextualise these subjects before or after the moment in which they are represented;8 it is this suspended space of transition on which Emmanuel focuses, as does the rite of passage described by Turner (1967:96).

It is not only the subjects who are themselves anonymous in their transitions; it is the moments of transition themselves. Emmanuel's choice of rites of passage in Transitions suggests that he, as Turner (1967:94-95) does as well, considers that these liminal moments are not necessarily clearly socially sign-posted. Transitions can be hidden in plain sight, so accepted that they are disregarded, such as in Transitions (4), where a man, putting on his jacket to address guests at a dinner party, assumes a mantle of authority, donning the vestments appropriate to the occasion and his office. It is not co-incidental that casual viewers have interpreted this figure to be a priest officiating at a ceremony (Emmanuel 2009:[Sp]). In Transitions (5), the work that I return to in this article, the space of the turnstiles at Park Station in Johannesburg is in itself liminal; when getting permission to take photographs at the station, Emmanuel learnt that one platform is administered by Metro Rail, the other by a private rail company. But neither organisation claims responsibility for the area between the two platforms (Emmanuel 2009:[Sp]). This physical space has the 'peculiar unity' of the liminal, being literally 'that which is neither this nor that' (Turner 1967:99). It is a liminal space hidden in plain sight, compelling in its banality, disconcerting in the realisation that one crosses thresholds, material or figural, of which one is possibly, at the time, imperfectly aware. Emmanuel suggests that transitions in male lives may be similarly unseen and thus unacknowledged.

Some rites of passage, however, are more formalised. For Turner, the function of a rite of passage is to draw a line in the sand, to mark or alter the body and to prise open a space for the enactment and acknowledgement of the subject's change in social status by the subject and his audience and society. The rite of passage confirms as well as facilitates the transition. Such a rite of passage might be seen in the recruit's head shaving - Transitions (2) - and the "crowning" of the bridegroom during a Lebanese Catholic wedding ceremony - Transitions (3). Death then, as the final transition or rite of passage, may have elements of both and is almost always context dependent. It is a rite of passage that is likely to have a deep effect on those within the social circle of the deceased; it is from this position that Emmanuel considers his experience of the death of each of his parents in Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017.

Markings of loss and memory

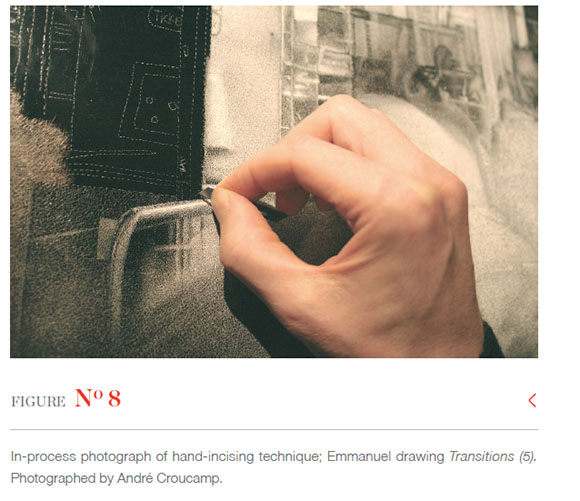

Emmanuel has said several times in different interviews that he starts from a point of loss, failure and inadequacy, describing Transitions, for example, as 'an attempt to hold onto a moment that has already shifted into something else' (Emmanuel cited by Croucamp 2008:[Sp]); he indicates that his intention was 'to capture that liminal moment when something is changing from one thing to another...a man changing from one thing to another...something impossible to capture' (Emmanuel cited by Croucamp 2008:[Sp]). This intention is enacted in the process of scratching in the drawings. The five drawings have appeared to viewers at first glance to be photographs or that the images were somehow projected onto the paper, but in reality have been scratched, laboriously and obsessively, onto already exposed photographic paper with small razor blades (Emmanuel 2010:[Sp]). In their execution, they express the paradox and impossibility of capturing such fleeting and indeterminate moments. Photography as a medium emphasises the relationship between absence and presence in that every photograph documents a lost present, captured with light as photographic paper is exposed. In these works, however, if the drawings are assumed to be photographs, what is "lost" or "unseen" in a cursory looking at the images is the time taken by the artist's scratching-drawing process.

Norman Bryson (1983:131) asserted that one should concentrate on the process of painting, on the individual brushstrokes, which would break down the illusion of mimetic wholeness by revealing the building-up or creation of the work. Similarly, literally, with Emmanuel's work, focusing on the scratching process reveals the images both technically and conceptually.

Scratching into exposed photographic paper, Emmanuel works in a subtractive manner (Figure 8). Although his medium here is paper and his production on a large scale, one can see his training as a printmaker and his long-standing preference for manière noire techniques. He creates tones by scratching away the black emulsion and the infinitesimally thin rust-coloured middle layer to the "base colour" bare white paper beneath. He works down to light, learning, as he says, 'to control the process of drawing with light' (Emmanuel cited by Croucamp 2008:[Sp]). The technical process becomes conceptual, a working backwards in time; as Emmanuel says: '[I]t is as if you are reversing the photographic process...projecting the light from your own memory onto the paper' (Emmanuel cited by Croucamp 2008:[Sp]). The yearning, loss and failure inherent to the melancholic fallibility of memory, its representation and its mediation of experience motivates Emmanuel's process (Emmanuel cited by Croucamp 2008:[Sp]). I term these, following Kuhn, Emmanuel's acts of memory, or memory work.

When describing his technique, Emmanuel speaks of 'scratching' rather than "incising", although 'hand-incised' is the description given to the captions of his works (Emmanuel 2009:[Sp],2022:[Sp]). An "incision" suggests a deep, decisive, singular cut, while "scratch", "scratches" and "scratching" suggests repeated, accumulative markings - the desire to be let in or let out - the marking of the surface to shape it, but not to destroy it. Scratching draws attention to the surface of a work as surface, as Butler (2006a:189) describes the body, which is as a variable boundary whose permeability is politically regulated. The drawings exist very much on and through their surfaces; as Emmanuel says, 'I am trying to seduce the viewer into my experience of the surface' (Emmanuel cited by Croucamp 2008:[Sp]). His technique creates a forgiving surface that - like memory (controversially) and unlike experience - may be fashioned and refashioned; as Emmanuel explains, although the technique might not allow for mistakes in that an area or detail deemed to be too dark or light cannot be undone or erased, he can shade around and so reintegrate the error (Emmanuel 2009:[Sp]). Photography uses light to capture a moment; its apparent preservation of the vanished moment is rendered both precious and obscene. Roland Barthes (1980:76) understands the photograph as 'literally an emanation of the referent' and thereby 'a skin I share with anyone who has been photographed'. By drawing into photographic paper that has been already exposed, Emmanuel holds on to a moment of loss and holds open a moment of fracture, obsessively recreating it over and over again. As he reflects: 'A photograph is such an instant thing, and I liked the idea of obsessing over something for so long that can take so quick to capture' (Emmanuel cited by Bosman 2009:[Sp]). The hyperbole of the scratching technique that created the drawings of Transitions, combined with their impression of photo-realism, gives them a subversive, mimetic quality.

The degree of control that the artist has over the process and the final product -including the ability to hold open the moment that the photograph captures in a burst of light - is very different when Emmanuel works with carbon paper. Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017 also depict rites of passage - as the artist says, 'the final transition', that of death (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]). The qualities of carbon paper as a medium, however, which I discuss now, challenge Emmanuel both personally and professionally and open new opportunities for meaning- and memory-making through a material process, in his practice.

Skin memory: Veil1954 and Carbon Dad 2017

Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017 also extend meditative temporal duration for Emmanuel in the time of their execution: Veil 1954 took 11 months and Carbon Dad 2017 took a year of full-time work to complete. Both were for Emmanuel (2021:[Sp]) 'a ritual of remembering' as he grieved and reflected on the passing of his mother (to whom Veil 1954 is an homage) and his father (represented in Carbon Dad 2017, scratched from photographs taken a few months before his death). The exhibition of which these two works form a part, Substance of Shadows, was for Emmanuel (2021:[Sp]) a reflection on 'the tenuous nature of memory'. He continues:

The only certainty is change. We try to hold onto memories in the hope of maintaining some coherence and continuity, but our memories are largely inventions and they too change over time. We commemorate our invented pasts in an attempt to fix them in the present. We even impose them on the generations that come after us, linking them to the past through anniversaries, memorials, pilgrimages and rites of passage, in an attempt to bind their lives to ours (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]).

Unlike Barthes' attention to the material and mechanical processes of photography, that led him to assert the "truth telling" quality of the photograph, Kuhn's (2000:186) emphasis is far more on the object relation between the photograph or memory object and the viewer's memory processes; her position is thus that the photograph does not so much replicate as (re-)produce memory. The acts of memory as prompted by objects may be understood, according to Kuhn (2010:2) 'as embodiments, as sites of construction and negotiation, of memory'.

Emmanuel's own exploration of the intransigence and multiplicities of memory from a scholarly (rather than personal) perspective is in line with, although not directly influenced, by Kuhn. Contemporary memory studies (that weave folk, popular, public and oral history and mythology) examine the power of memory, in its formation, retention and sharing, in individuals and communities, and how it shapes individual and public interpretation and knowledge about the past. The fallibility, truths and multiplicity of memories, Kerwin Lee Klein (2000:135) points out, assert tropes of identity, core, self and subjectivity in historical discourse, and this is what appears to be meaningful for Emmanuel.9 Engagements with memory may even have the possibility to offer, as Marianne Hirsch (2012:16) describes, 'a means to account for the power structures animating forgetting, oblivion, and erasure and thus to engage in acts of repair and redress'.

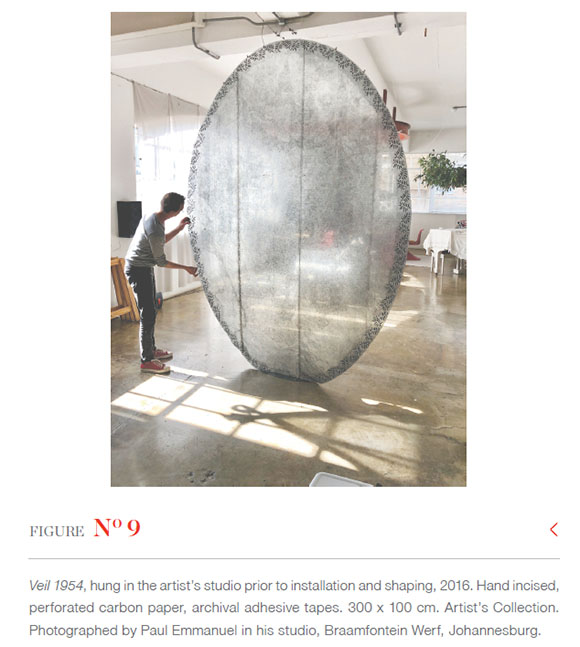

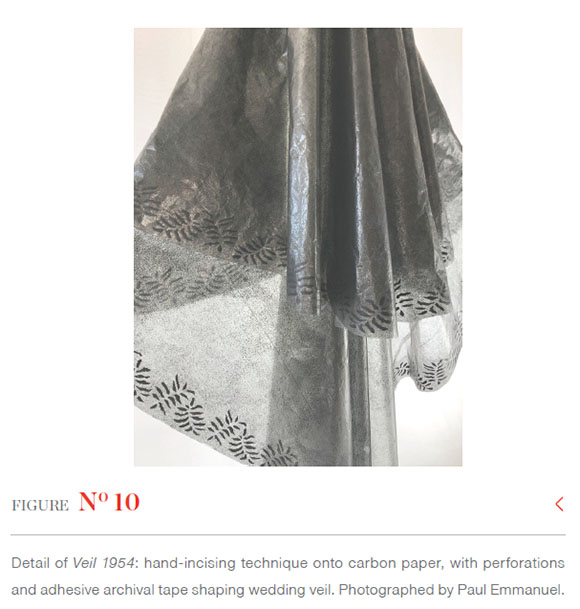

In Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017, Emmanuel scratches onto carbon paper rather than exposed photographic paper, which presented him with a very different material experience to the production of Transitions. Carbon paper is an antiquated material in the digital age; its ability to transfer, to produce a shadow copy, now used almost exclusively (and via a different chemical process) in manual receipt books and till receipts. Pressure applied transfers carbon coating to a sheet of paper below, making the copy. Sourcing the last known commercially produced roll of carbon paper in South Africa from a factory on the East Rand of Johannesburg, Emmanuel continued to work down from dark to light, scratching down into the darkness of the carbon film coating the "paper" or rather a thin poly-plastic blend. When the carbonite is removed, the substance remaining is a fragile, semi-transparent material that resembles a stiffened organza-like fabric, with resemblances to human skin, and makes a sound like leaves rustling. Emmanuel was clear that the resulting works should be displayed in-the-round, hanging freely in the gallery space or manipulated, sewn, or "fleshed out" such that they had a three-dimensional quality. A work such as Carbon Dad 2017 therefore had a corporeal material presence, although two-dimensional, as it gently tremored and undulated in the gallery space, responding to air currents, ambient light permeating both sides, allowing forms and landscapes visible through the long window of the UJ Art Gallery in front of which the work was hung to be seen through and with the image of the artist's father. Veil 1954 was affixed together from pieces of carbon paper off the roll using archival adhesive tape to create the perfect oval (Figures 9 and 10) that replicated the veil that the artist's mother wore on her wedding day. The oval veil was then pinned and hung in the gallery space to replicate the folds of silk flowing from the headpiece as the bride wore it in 1954, creating a ghostly absence that presided over the exhibition space.

The carbon residue from the scratching process when the works were in progress was collected every day by the artist, and then poured on the floor beneath every work on the exhibition. Intended to represent '"discarded information" or "lost memory"', the carbon residue resembles ash; Emmanuel (2021:[Sp]) reflects of it, 'We cannot hold onto the past'. For the artist, Carbon Dad 2017 depicts his father's "presence" at the time of his death, despite his enfeebled body, while Veil 1954 describes his mother's "absence" before hers, as most of her identity had been inexorably claimed by Alzheimer's Disease (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]). For Emmanuel, this fragile translucent skin-like substance that arose out of the carbon residue, and its relationship to the skin of the elderly, held metaphors for the 'carbon cycle of life' (Emmanuel 2021). As he says, 'I was strongly influenced by my parents' frailty which forced me to confront my own mortality' (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]).10

Titling his work not 'Dad' but Carbon Dad 2017 indicates Emmanuel's grappling with the futility of representation in the face of loss, the impossibility of fixing or recreating a memory of his father; as he says, the work 'is a meditation on copies, imperfect copies vainly defying the inevitable impermanence of it all - a failed attempt to recapture a moment' (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]). Scratching marks or drawing in this subtractive process meant materially that in order to create an image with definition, Emmanuel had to remove the very carbon film that was capable of making copies, mirroring a process of memories receding and the unconscious processes by which some memories are amplified and fixed, and how they become so. He likens this process to 'the way the surface of a relic is abraded with the constant rubbing of devout pilgrim hands' (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]). Hirsch (2012:34) describes 'acts of transfer' by which memory can be transmitted or passed on through an object's indexicality. Emmanuel materialises - or embodies - the slippages and the degradations that occur in the memory process - hyperbolised to a tragic degree by the progress of diseases such as Alzheimer's - through his repurposing of carbon paper as the medium. Representing the 'sense memory of trauma' on the skin and through the marked skin - here arguably the semi-translucent skinlike medium - is characteristic of feminist preoccupations with the subjective, the private and the daily as points of memories (Hirsch 2012:23). Finally, the carbon transfer process references genetic inheritance, and particularly, male subjectivity formation and acculturation, as represented by the father. As Emmanuel worked, he mused of his father: 'A body that had such power over me all my life. A body that copied part of his biology into me. A person that attempted to copy his culture, modelling what it meant to be a man in ways with which I did not resonate' (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]).

Unlike the sharp definition of the Transitions works that were scratched into exposed photographic paper, Emmanuel found the mark-making or scratching process on carbon paper 'unpredictable and difficult to control' (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]). The carbon might flake off in unexpected and undesired ways, or the blade might perforate the fragile backing material, resulting in delicate tears and rips. If this happened, Emmanuel could not but leave the "imperfection" to remain as part of the fabric. He reflects that the most difficult thing for him in these years of caring for his parents, was loss of control, where he could not predict or guarantee outcomes, could not account for all eventualities, and could not abate their pain, suffering, indignities and confusion (Emmanuel 2022:[Sp]). The delicacy, translucency, perforations and tears in the material therefore stand in for the skin of the elderly, and both literally and symbolically, for their vulnerabilities (Figure 10).

For Butler (2006b:26), one's body is and is not one's own in the struggle to reconcile the degree of autonomy that one might have over one's body, where vulnerability and agency appear to be conflicting elements. Butler (2006b:20) finds that '[l]oss and vulnerability seem to follow from our being socially constituted bodies, attached to others, at risk of losing those attachments, exposed to others, at risk of violence by virtue of that exposure'. Emmanuel recounts how, when his father posed for the photographs that became the reference for Carbon Dad 2017, he got a small bruising and abrasion on the skin of his shoulder, as he turned over to lie on his stomach to be photographed from behind (UJ Art Gallery 2021). The psycho-somatic dependencies and frailties of elderly bodies are poignantly explored in Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017.

Shrouding and veiling: Presence and absence

Emmanuel is deeply drawn to the shadows of objects and people that were imprinted onto the ruined concrete walls and steps of Hiroshima and Nagasaki after exposure to the heat and light of the atomic blasts "bleached" the surrounding areas, leaving "shadows" of the concrete's original tone. He finds an analogy with these tragic imprints and the story of the Turin Shroud that he was told as a child at a Catholic school - that the linen cloth was Christ's burial shroud and that the imprints, which resemble a man's face and form, were 'miraculously burned onto the fabric by an unknown mysterious flash of Divine Light and energy' (Emmanuel 2022:[Sp]). Following a site visit to the Pelindaba Atomic Research Facility north of Johannesburg, Emmanuel had a dream in which, as he recounts, 'I saw myself peeled from my own skin, as if I was discarding a burnt, blackened outer covering' (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]). With these influences, Emmanuel took the decision to create an artwork as a shroud for his father that both evoked and subverted the holy relic (Emmanuel 2022:[Sp]). Carbon Dad 2017 is made to the dimensions of the Turin Shroud (which is approximately 440 mm x 110 m) and follows the same horizontal views of the front and back of the body, as if the image were made through it being shrouded in fabric. As Emmanuel points out, unlike the purported shroud of Christ, the man represented in his work is an ordinary, secular and aging figure, not a divine one (2021 UJ Art Gallery). Émile Emmanuel was a life-long devoted Lebanese Maronite Catholic. Lebanese Catholicism prizes holy relics, as Emmanuel explains, and while he sees himself as subverting this belief system, he also sought to honour his relationship with his father, in all its complexities (UJ Art Gallery 2021); as he says, 'simultaneously interrogating my memories of him silencing me throughout much of my life and honouring him for allowing me to grow close to him at the end of his' (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]). That his father allowed him to photograph him naked was, as Emmanuel points out, an extraordinary gift to his son, given Émile Emmanuel's own conservative background, despite his respect for his son as a professional artist (UJ Art Gallery 2021). Emmanuel ponders though the meanings of this gift:

Posing for the camera was an act of sacrificing himself and his dignity to his shrill-voiced, limp-wristed, artist-of-a-son. That sacrifice left me with the burden of responding through the creation of a sacred shroud. Did he agree because he knew it would bind me to a ritual of remembering? I wonder (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]).

The shroud Emmanuel created is also a rehearsal for his own. Emmanuel has represented men in transition before in Transitions, but the specificity of their subjectivities is deliberately anonymised. Emmanuel does not feel he has the authority to represent anyone except himself (UJ Art Gallery 2021). His father's body though, as he says, copied part of itself into him. He did not, for instance, feel comfortable representing his mother in any figurative way, not only because he sought to engage with the painful disconnect between her physical body and sense of self caused by the Alzheimer's Disease from which she suffered, but also because Emmanuel has not had the experience of living in a biologically female body (Emmanuel 2022:[Sp]). Of Transitions, Emmanuel says that it is the transitory ritualised spaces of non-affiliation and liminality that fascinate him; he describes them as 'spaces in which a man is in the process of changing his status, with one foot in one world and the other in another'. In Carbon Dad 2017, the making of work was his given space to contemplate his own embodied mortality.

The shroud that he created for his mother also sought to explicate her particular rite of passage, which presented itself as a disconnection between her body and her mind, in a cruel enactment of a kind of Cartesian dualism (where her sense of self left or transitioned before her body). As he says,

Creating Veil 1954 felt like an attempt to capture both the presence and absence of a personality leaving one realm for another. It is conceived to be suspended both literally and metaphorically "between worlds"... an adornment of concealment and revelation accompanying her through her final transition (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]).

For Emmanuel, his mother's veil carries her strong connection to Catholicism, through the veiling and revelation of the bride in the Catholic wedding ceremony, recalling the crowning of the Lebanese Maronite Catholic bridegroom in Transitions (3), which would have been his father's experience. When his mother's personality was eventually almost completely erased, Emmanuel found that her connection to the structures and institution of Catholicism somehow remained, especially expressed in how she understood and related to his father (Emmanuel 2022:[Sp]). As he explains, the veil 'outlines all that was left of my mother's connection to the institution that defined their relationship and is a representation of all that remained of her former self' (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]). Working on the veil, removing scratch by scratch the solid black carbon layer, revealing the semi-translucent skin-like material below, Emmanuel felt as though he was 'scraping away the veil's "heaviness" and allowing the light through' (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]), as if he were concomitantly removing the weight of his mother's illness, and the weight of her life experiences as well (Emmanuel 2022:[Sp]). He describes Veil 1954 as 'membrane-like' (Emmanuel 2021:[Sp]).

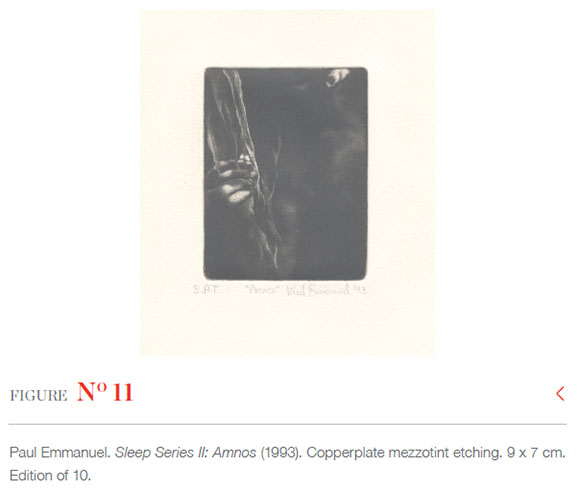

Imagery of shrouded and shrouding forms held in putative amniotic sacks reoccurs in Emmanuel's work. In Sleep Series II Amnos (Figure 11), one of Emmanuel's earliest (1993) and smallest (7 x 9 cm) professional works, emergent forms arise from or release into the soft dark inked tones of the copperplate mezzotint etching. Intimating passage and care, the 'membrane-like' veil performs a holding function, one that is also evident in Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017. The medium however also allows more overtly for the slippages and degradations that occur in memory over time and lifetimes. What is to come, may have been, in the artist's oeuvre and in human cycles.

Conclusion

Emmanuel's focus on rites of passage, like Butler's conception of gender, exposes 'the illusion of an abiding gendered self', proposing instead the self as 'a constituted social temporality' (Butler 2006a:191; emphasis in original) or 'a process of materialization' (Butler 1993:9; emphasis in original). Liminal rites of passage confirm, affirm and produce an individual's change in state, status or role. They are potentially disruptive to the social order because they acknowledge that the construction of subjectivity is an ongoing and ever-tended process, one of materialisation. Rites of passage however cannot but be potentially disruptive because their designated social function is to incorporate, even obscure, these transitions, to naturalise them and make them seem even inevitable. With Transitions, Emmanuel engages with this disruptive potential through his protracted "holding open" and incisive interrogation of a moment of transition, loss and becoming. With Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017, however, it is the "undoing" of subjectivity and physical bodies that is held in mind, and held through the fragile, difficult and embodied nature of working into the medium of carbon paper. These two works function, I propose, as a deepening through personal experience of the unformed metaphors latent in Transitions (5). The time held in Veil 1954 and Carbon Dad 2017 marks movement between presence and absence and thereby allows for meditations on loss, life and memory. Emmanuel's memory work, ultimately, draws us all into 'a more profound lived understanding of the activity of remembering and of how remembering binds us as individuals into shared subjectivities and collectivities' (Kuhn 2002:156).

Acknowledgements

Paul Emmanuel has consented willingly and generously to my requests for interviews, images and all manner of engagement with his work, not only for this article, but over the last ten years; for all of which, I am most grateful. I also acknowledge the SARChI Chair (South African Research Chair in South African Art and Visual Culture) in SA Art and Visual Culture.

Notes

1 . Substance of Shadows was exhibited at the University of Johannesburg Art Gallery (11 September-2 October 2021) as a planned component of Emmanuel's University of Johannesburg/ Johannesburg Institute of Advanced Study fellowship in 2021. The works consisted of nine pieces hand-incised into perforated carbon paper and one HD video work Rising-falling (3 mins, 45 sec, looped). Veil 1954, Rough Collar, Scholars and Executives and Collars in Formation were three-dimensional works of perforated carbon paper stitched according to tailoring or other patterns, present despite the 'absence' of their ghostly human wearers. Branded, Ex Unitate Vires, and Carbon Dad 2017 were two-dimensional works suspended to be visible on all sides. For a detailed artist's statement, see Emmanuel (2021). The exhibition or the individual works within the body of work have not as yet received scholarly attention; for blog posts discussing individual works, see Allara and Auslander (2020) and Auslander (2020).

2 . Mezzotint, or manière noire technique, is an intaglio printing process that works reductively, from dark to light, and can produce particularly subtle and varied monochrome 'half tones' (hence the name, mezzotint). From the eighteenth century, it was used progressively less given that other techniques such as lithography may more easily yield comparable results; from the mid-twentieth century, its use was revived by artist-printmakers.

3 . Emmanuel's mother, Joy Erasmus Mendoza, was belatedly diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease from which she died in 2017 at the age of 86. Emmanuel was the caregiver to his mother from 2014 to 2017. He also cared for his father, Émile Joseph Emmanuel, who passed away a few months after his wife in February 2018 at the age of 93. Emmanuel (2021:[Sp]) reflects: 'Walking this path with her and my father during her years of declining cognition and witnessing the slow disappearance of her personality was an experience impossible to convey in words'.

4 . Transitions was a four-year project of two parts, completed in February 2011. Part One, Paul Emmanuel: Transitions was a touring, solo museum exhibition comprised of a body of work of five drawings of rites of passage and 3SAI: A Rite of Passage, a short, non-verbal, artist's film documenting the head-shaving of new recruits at a South African military base. It was exhibited locally and internationally from 2008-2012, including at the Smithsonian Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C. in 2010. Each drawing comprises five panels, is three metres in width, and took six months to complete. Five panels make up one drawing, but the panel borders are not a product of a framing process, rather the exposed photographic paper with which Emmanuel begins. Working from photographs he took at each event, he is both involved and excluded. To make these images, he scratched with a small razor blade into exposed photographic paper. The drawings were bought together by the Spier Contemporary Collection from plan in 2007. When exhibited, the box-framed drawings are installed in a specific sequence, suspended from the ceiling back-to-back, to be viewed one at a time by the viewer who must move around them. Part Two, Transitions - Prints & Multiples, is a limited-edition series of hand-drawn, -coloured and -printed maniere noire lithographic triptychs based on the Transitions images and concepts.

5 . While acknowledging the significance of Turner's research, I nevertheless distance myself from the primitivising tendencies that underpin some arguments and expressions.

6 . Unrelatedly, Emmanuel was born in Kabwe (then Broken Hill), in Zambia in 1969, and moved with his parents and brother to South Africa when he was four years old.

7 . The words "ritual", "ceremony" and "rite of transition/passage" may in common parlance be used interchangeably but for Turner, a "ritual" is transformative and refers to forms of religious behaviour associated with social transitions (such as birth, puberty and death), while a "ceremony" is confirmatory, referring to religious behaviour associated with social states (such as those of political and legal institutions). A "rite of passage" indicates and constitutes these transitions between states. Butler (see 2006a:189-193), uses the terms "ritual" and "ritualised" in a demotic way to describe repeated or habituated actions, in contexts not necessarily religious (as in "social rituals"). I take my cue from Emmanuel's own usage of "ritual" and "ritualised" which is closer to Butler's usage than Turner's. By "ritual" Emmanuel (2009b:[Sp]) means iterable actions, everyday or formalised, invested, consciously or unconsciously, with significance, which may include, but are not limited to, religious activity.

8 . The infant of Transitions (1) is the exception, but as Emmanuel reasons, by the time he had completed the drawing, months after the photographs were taken, the baby's malleable face and self had developed; the portrayed face no longer existed (Emmanuel 2009:[Sp]). When Emmanuel represents his father in Carbon Dad 2017, the figure is not at all anonymous, but intimately particularised; I examine the significances of this as the article unfolds.

9 . Emmanuel's Lost Men is an ongoing body of work in multiple iterations that most overtly engages with issues of personal and public memory and memorialisation. In this, Emmanuel draws on James Young's (1993) influential concept of "counter-memorials": the "counter-histories" that such memorials give presence to are histories not recognised by dominant national and official narratives, histories that seek social recognition of what is avoided, and address issues of trauma, failure and loss in the past. See Bronner (2011) and Von Veh (2020,2020a) for more on the Lost Men.

10 . Pamela Allara (2012) has compared Paul Emmanuel's Lost Men with Diane Victor's life-size drawings of elderly residents of nursing homes, using ash and charcoal as a medium, in her Transcend and Lost Words series (2009-2010). Allara's focus is on both artists' interrogation of white South African masculinities, post-apartheid. Allara (2012:34) finds that 'Victor's depiction of the decline of white male privilege led logically to the subject of the physical decline of aging'. She discusses the cultural aversion, even within feminist visual discourse, of representing the aging body, as well as the construction of women as "angels of the home" and "keepers of male virtue". In 2012, Emmanuel had not made his own life-size depictions of his aging father, or his mother's wedding veil that lends itself to comparisons with a "dark angel" or Madonna figure. Similar to Victor, he used his own conceptually laden medium (carbon paper, while Victor uses ash and charcoal). Further comparison now between these artists would yield insights beyond the personal contexts of loss and memory, which remain my focus in this article.

References

Aliara, P. 2011. Paul Emmanuel's Transitions: The white South African male in process. Nka 28:58-66. [ Links ]

Allara, P. 2012. Diane Victor and Paul Emmanuel: Lost men / lost wor(l)ds. African Arts 45(4):34-45. [ Links ]

Allara, P & Auslander, M. 2020. Ex Unitate Vires: Paul Emmanuel. [O]. Available: https://artbeyondquarantine.blogspot.com/2020/07/ex-unitate-vires-paul-emmanuel.html Accessed 4 April 2022. [ Links ]

Auslander, M. 2020. Veil 1954: Paul Emmanuel. [O]. Available: https://artbeyondquarantine.blogspot.com/2020/04/veil-1954-paul-emmanuel.html Accessed 4 April 2022. [ Links ]

Barthes, R. 1980. Camera lucida: Reflections on photography. London: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Bosman, N. 2008. Intricate obsession. [O]. Available: http://www.citizen.co.za/index/article.aspx?pDesc=79512,1,22 Accessed 26 March 2009. [ Links ]

Bronner, IE. 2011. Intimate masculinities in the work of Paul Emmanuel. MA dissertation, Rhodes University, Grahamstown. [ Links ]

Bryson, N. 1983. Vision and painting: The logic of the gaze. New Haven: Yale University. [ Links ]

Butler, J. 1993. Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of 'sex'. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Butler, J. 2006a [1990]. Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Butler, J. 2006b. Precarious life: The powers of mourning and violence. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Croucamp, A. 2008. Conversations on the transience of light between André Croucamp and Paul Emmanuel, in Transitions, edited by P Emmanuel. Johannesburg: Art Source South Africa:unpaginated. [ Links ]

Emmanuel, P. [Sa]. Transitions concept document and media kit. [O]. Available: https://www.paulemmanuel.net/webprices/big%20images/conc&media.pdf Accessed 30 April 2022. [ Links ]

Emmanuel, P. 2009. Interview between Paul Emmanuel and the author on 19 July 2009, Makhanda. [ Links ]

Emmanuel, P. 2009b. Email correspondence between Paul Emmanuel and the author on 24 October 2009. [ Links ]

Emmanuel, P. 2010. Email correspondence between Paul Emmanuel and the author on 8 September 2010. [ Links ]

Emmanuel, P. 2021. Substance of Shadows concept document and media kit. [O]. Available: https://www.paulemmanuel.net/exhibitions/pastexhibitions/pastexhibits1/Substance%20of%20shadows/SOS%20MUSEUM.pdf Accessed 1 September 2021. [ Links ]

Emmanuel, P. 2022. Interview between Paul Emmanuel and the author on 8 April 2022, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Klein, K. 2000. On the emergence of memory in historical discourse. Representations 69:127-150. [ Links ]

Kuhn, A. 2000. A journey through memory, in Memory and methodology, edited by S Radstone. Oxford and New York: Berg:179-196. [ Links ]

Kuhn, A. 2002. Family secrets: Acts of memory and imagination. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Hirsch, M. 2012. The generation of postmemory: Writing and visual culture after the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Petherbridge, D. 2018. How do we respond? Embodied vulnerability and forms of responsiveness, in New feminist perspectives on embodiment, edited by C Fischer and L Dolezal. London: Palgrave:57-79. [ Links ]

Turner, V. 1967. The forest of symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

UJ Art Gallery. 2021. Extended walkabout: Paul Emmanuel and Michelle Constant. [O]. Available: https://movingcube.uj.ac.za/watch/paul-emmanuel-substance-of-shadows/extended-walkabout-paul-emmanuel-and-michelle-constant/ Accessed 28 April 2022. [ Links ]

Van Gennep, A. 1960. The rites of passage. Translated by MB Vizedom and GL Caffee. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Von Veh, K (ed). 2020. Paul Emmanuel. Johannesburg: Wits Art Museum. [ Links ]

Von Veh, K. 2020a. The material of mourning: Paul Emmanuel's Lost Men as counter- memorials. Image & Text 34:1-21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2020/n34a15 [ Links ]

Young, J. 1993. The texture of memory: Holocaust memorials and meaning. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. [ Links ]