Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Image & Text

versión On-line ISSN 2617-3255

versión impresa ISSN 1021-1497

IT no.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a20

ARTICLES

Queering the soil: Reimagining landscape and identity in queer artistic practices in Cyprus

Elena ParpaI, II

IDepartment of Design and Multimedia, University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

IIDepartment of Multimedia and Graphic Arts, Cyprus University of Technology, Limassol, Cyprus. elena.parpa@gmail.com (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2591-5405)

ABSTRACT

This article concentrates on the work of artists who identify as queer in Cyprus, a place marked by colonialism, rival nationalisms and ethno-political division. More specifically, it examines the ways their work disrupts confining perceptions of nationhood, gender and sexuality that suppress difference and delimit identity in a conflict-ridden, ethnically divided society. These ideas are discussed in relation to the examples of Krista Papista, a Greek Cypriot visual artist, musician and performer, and Hasan Aksaygin, a Turkish Cypriot artist, whose work encompasses elements of painting, performance and installation. As I argue in this article, by calling forth interpretations of "queer" that go beyond the term's common application as an adjective or a noun, these artists employ tactics of queer use. In so doing, they inscribe queer life and experiences into landscapes, traditions and symbols, as in "over" the soil, used here as a metaphor to point to those elements that are commonly invoked in delineating the physical and imaginary topos of the nation from which people identifying as queer are often excluded as non-conforming others. As such, they make space for an alternative topos to emerge, where expanded notions of gender, identity and belonging are cultivated away from established stereotypes and divisive, nationalist narratives.

Keywords: Landscape, place, identity, gender, queer, queer artistic practices.

Challenging Legacies in Post-Colonial and Post-Socialist Notions of Place over there / my body is foreign / it's in the land / flowers, soil, seed, and clay / it's in construction / in the destruction / the derelict / the abandoned / my body is there / in the primal stuff / the raw / queer in soil / in the photos / potatoes I take / of places Yorgos Petrou, I Take of Places (2019)1

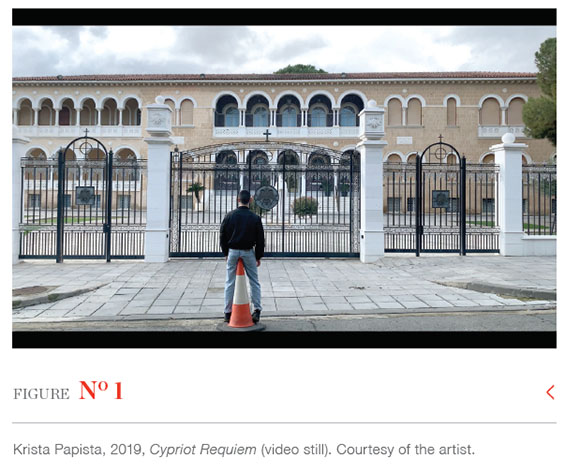

In this article I focus on artists from Cyprus, who identify as queer.2 I examine how the conscious recognition of a queer positionality informs their critical thinking and artistic output when considering what it means to be from a place marred by conflict and ethnic division. An indicative example is queer visual artist, musician and performer, Krista Papista. Consider, for instance, Cypriot Requiem, a song which she wrote and performed in 2019.3 It falls under the broad designation of "experimental electronic"4 with lyrics that are simultaneously moving and contentious. The video filmed to accompany it works on similar registers, balancing between elements of shock value and emotive sensibility.5 It positions the viewers in the old part of Nicosia, the capital of Cyprus, close to a site that has become emblematic of the country's troubled history: the "Dead Zone", also known as the "Green Line" or "no-man's land", that has divided the city and the island between the Greek Cypriot south and the Turkish Cypriot north for almost half a century now.6 There, against roadblocks and checkpoints patrolled by the military and the police, the viewers follow Krista Papista and friend, artist Theodoulos Polyviou, as they explore landscapes strewn with barbed wire, sandbags and competing symbols of national sovereignty, including flags and slogans graffitied on walls. Although the two appear to be idly drifting across places with noticeable indifference, they are acutely attuned to the historical context, the militarised culture and nationalist inheritance they engage with. They respond with gestures and elements of choreography that reverberate with homoerotic, sexual undertones and purposeful insolence. At one point, Krista Papista urinates in public and Polyviou performs an erotic dance using a road traffic cone outside the fenced-off seat of the Cyprus Orthodox Church, an institution accused of denying LGBTQ voices (Figure 1).

Within the context of this idiosyncratic protest, the landscape in and around the liminal, marginal zone of the island's divide becomes the site of queer uses of space, which make the queer body visible, where it has been historically excluded as marginal and non-conforming. Concurrently, and as the video unfolds, the camera focuses on places and aspects of everyday life that construct the visual portrait of Cyprus via the overused stereotype of the tourist island on the cultural crossover between East and West. The artists inhabit spaces where such imaginaries materialise at the same time that they orient themselves towards places of queer experience, including the Nicosia Municipal Garden, a known "cruising area" for the island's gay community. At one point Krista Papista sings: 'Κάτω απ' τη δική μας λεμονιά' (Under our own lemon tree). The verse can be understood as a poetic reference to the island itself (the lemon tree - like other types of citruses - representing the Cypriot landscape), now claimed, despite its dystopian reality and perhaps because of its perceived fluid, indeterminate cultural identity, as queer territory.

In this article I seek to trace the ways in which Cypriot artists who identify as queer seek to expose - as witnessed in Cypriot Requiem - the socio-political context of a divided society and the conditions of exclusion it produces and perpetuates. When considering this, I concentrate on how their approaches disrupt confining perceptions of nationhood, gender and sexuality that suppress difference and delimit identity. I discuss these ideas in relation to the intersecting divides in Cyprus, turning to the examples of Krista Papista, who is a Greek Cypriot, and Hasan Aksaygin, a Turkish Cypriot artist, whose work encompasses elements of painting, performance and installation.7 Although both artists live and work in Berlin, their artistic practices constitute situated reflections of themes drawn from their Cypriot experiences. The artists also share similarities in how their work calls forth interpretations of "queer", beyond the term's common application as an adjective or a noun, to denote a positionality that challenges social and cultural norms.8 As I put forward, this manifests in their work as tactics of queer use that inscribe queer life and experiences into landscapes, traditions and symbols, as in "over" the soil, used here as a metaphor to point to those elements that are commonly invoked in delineating the physical and imaginary topos of the nation from which people identifying as queer are often excluded as non-conforming others. I argue that through such processes an alternative, dynamic topos is produced, perforated by narratives and affective responses that inject queerness into prevalent conceptions of place, identity and belonging.

I begin to discuss these ideas by concentrating first on meanings of topos and on the interrelating notions of nation, gender and sexuality in Cyprus, before I move on to examine the ways these become the objects of queer use in the work of the artists considered. My approach to queer use is informed by relevant scholarship that explores alternative modes of togetherness and community-building that disrupt the linear temporality of heteronormativity (Halberstam 2003) and the conditions of marginalisation it prescribes by releasing the potential of things to be used otherwise (Ahmed 2018,2019).

Taming desire: Gender and sexual identity in divided Cyprus

In (now definitive) readings of the notion that defy its conceptualisation as universal and eternal, the nation has been explained as an 'imagined community' and as an essentially modern construct (Anderson 1983:6) built on specific uses of traditions and symbols (Hobsawm 1983). Commonly understood as unchanging and fixed, traditions have been reconsidered in relevant scholarship as 'invented...instituted, inserted into the historic past' to provide with the aid of emotionally charged symbols, such as national flags and emblems, a sense of continuity and social cohesion to a community, 'expressing or symbolising it as a nation' (Hobsawm 1983:1-2,9). Conversely, landscape has been theorised as a cultural construct and a potent ideological representation that encodes notions such as the nation, serving dominant socio-political agendas and naturalising power relations (Mitchell 2000,2002:1-34).

Studies on notions of nationhood and intercommunal relations in Cyprus have recognised an 'unimaginable community' (Calotychos 1998:1-32) split over competing claims to political control and narratives of history and identity.9 Uses of emblems, customs and traditions have also been identified as subjects of political debate (Kizilyürek 1993:60) and intercommunal antagonism (Azgin & Papadakis 1998). Within this context, civil politics around issues of gender and sexuality have been side-lined at best (Kamenou 2020). According to relevant scholarship, the resulting restrictive conceptualisation of the political along with the prevalence of nationalist rhetoric across the Cyprus divide has stifled discussions on the privileges and exclusions it produces and perpetuates (Kamenou 2020). In fact, political and institutional discursive regimes on the island, with the Orthodox Church of Cyprus being the most prominent, have played an instrumental role in prescribing heteronormative family ties and heterosexual conceptions of femininity and masculinity as the backbone of national coherence (Kamenou 2011:27). As such and under the rubric of heterosexuality, men are seen as the guardians of the nation's blood line and the defenders of the national collective, while women stand as the biological bearers and symbolic signifiers of the nation and its cultural values (Hadjipavlou 2010:38-40,42). In the words of social and political scientist Naya Kamenou (2011:28), whose research extends on both sides of the divide: '"real" Cypriot identity and "right" Cypriot citizenship are equated with performing a specific religious, gender and sexual identity'.

Upon reflecting on such observations, the socio-political context of Cyprus emerges as especially instructive in demonstrating that which has been historically detected: nationalist discourses control and tame sexuality (Mosse 1985:10; Kamenou 2011:26-29).10 Consequently, alternative perceptions of gender and expressions of sexuality are being condemned as unpatriotic and/or as foreign and divergent from accepted conceptions of respectability and/or of what it means to be Cypriot (Karayannis 2004; Kamenou 2011:28, 31). While feminist critique has uncovered the gender-inequalities imposed by such articulations (Hadjipavlou 2010:35-36,41-42), queer theory and thinking has been applied in reflections on identity and its embodied negotiations of power (Karayianni 2017). In the field of literary theory, for example, Stavros Stavrou Karayianni (2017:63) calls on a queer perspective and, focusing on a selection of literary and critical texts that position the reader in the Dead Zone, traces its reconceptualisation as a 'zone of passions' and 'a landscape where desire, apprehension, and memory play themselves out'. Such elaborations - that can be seen as conversant with Krista Papista's interpretations of the Dead Zone in Cypriot Requiem - are in stark contrast with standard representations of the island as always marked by trauma and conflict. In Karayianni's view (2017:66), they encourage a 'queer re-imagining' that brings to the fore 'the potential of a topos to inspire emotions, thoughts, possibilities that reach beyond the dominant narratives'.

Although a rhetorical term in the English language, topos is the Greek word for "place". In queer thought, it becomes relevant through its derívate word utopia, meaning "no place". Most convincingly, José Esteban Muñoz (2009:1) in his now seminal text Cruising utopia: The then and there of queer futurity has taken up the notion to discuss queerness as a not-yet completed project that exists in the future as an ideal or, as he poetically elaborates, a 'warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality'. This understanding of queerness as a placeless temporal operation can be traced in the future-oriented propensity of Karayianni's idea of a 'queer re-imagining'. He considers it as inspiring a 'potential', a future-to-be which nevertheless occurs in relation to an already existing entity - a topos (Karayianni 2017:66).

It is useful to be reminded here that topos in Greek oscillates between the actual and the imaginary. At the same time as it means a physical location, it marks a passage in a text, a 'commonplace' or a place in the mind (Leontis 1995:18-19). The interrelation between the tangible and intangible dimensions of topos has been recognised as crucial in considerations of how places become homelands. According to literary scholar Artemis Leontis (1995:2), the interconnection is necessary to processes of topography by which the graphe (writing) of a topos is achieved by accruing not only reports of a place's physical presence, but also images, symbols, narratives, customs and traditions, which point to how places are also imagined, made-up.

Interestingly, topos also links in etymological terms with topio (τοπίο), the Greek word for "landscape", pointing to the reciprocal relationship between the notions. Lived experiences of places feed into their cultural construction as landscapes and vice versa. Landscapes shape the way places are conceptualised and understood (Delue Ziady & Elkins 2009:92). Yet, what if both "place" and "landscape" form part of a topography and an imaginary that is construed out of disputed territories and contested symbols, interpretative narratives and uses of tradition which serve specific socio-political agendas and nationalist ideologies that disregard the "other"? And what if the category of the "other" concerns, in this case, not only members of the rival community but the non-heteronormative other?

In reflecting on these questions, the example of Krista Papista in Cypriot Requiem is telling. She pushes counter-essentialist narratives towards a kind of re-writing of topos that is inspired by queer experience, references and affect. In this, her orientation in the charged landscape of the Dead Zone can be understood as conversing both with Muñoz's (2009:1) 'forward-dawning futurity' of queerness as with Karayianni's (2017:66) located 'queer re-imagining'. As I argue in the next section, this is achieved by embracing techniques of queer use, which speak of the play of imagination in inscribing queerness into conceptions of place, landscape and by extent into notions of identity and belonging.

Unleashing desire: Krista Papista's orientations in the landscape

Described by the artist as a 'visual sound portrait', Cypriot Requiem belongs to a body of work that focuses on 'reimagining the power structures of Cypriot, Greek, Turkish and Middle Eastern rituals, investigating and critiquing nationalism and cultural heritage through...music, video art, images and performances' (Papista [Sa]:[Sp]). In Cypriot Requiem this is evidenced in the artist's proposed inhabiting of spaces by which the queer body orients itself in space, occupying it in a way that is disruptive. In line with queer feminist scholar Sara Ahmed's (2006) thinking, such approaches can be understood as calling for a queer phenomenology of space that tends to the spatial inclinations of desire. One may be reminded, here, of Polyviou's erotic dance, in which the queer use of an object (a road cone) and a specific location (the street overlooking the seat of the Cyprus Orthodox Church) are intended to make the queer body visible, where it has been historically excluded.

In later articulations on the disjoined experience of queerness, Ahmed (2018:[Sp], 2019:199) elaborates on queer use as referring to uses of objects 'for a purpose that is "very different" from that which was "originally intended"'. She sees such "uses" as squeezing out the queerness of things while simultaneously signalling a refusal 'to ingest what would lead to your disappearance' (Ahmed 2019:206). The uses of objects and spaces witnessed in Cypriot Requiem serve as evidence of both inclinations; they demonstrate uses that deviate from the perceived norm while hinting at a refusal to be ignored, side-lined, silenced. They also serve as indications of how queer use can potentially entail 'an act of destruction, whether intended or not; not ingesting something, spitting it out; putting it about' (Ahmed 2018:[Sp]). Queer use, according to Ahmed (2019:208), acquires in this context the dimensions of vandalism, of 'the wilful destruction of the venerable and the beautiful'.

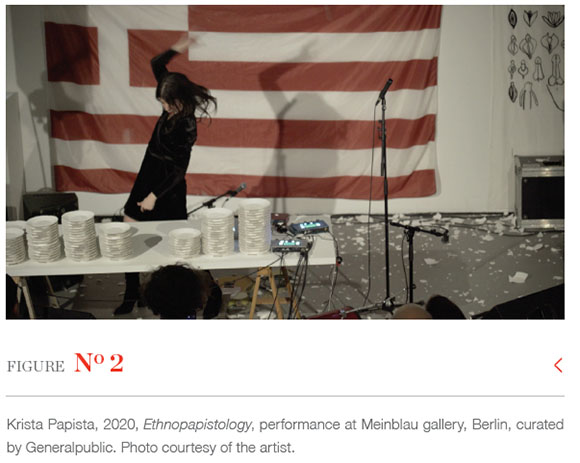

These ideas can be understood in relation to Ethnopapistology (2020), Krista Papista's performance in which acts of queer use are directed at the Greek custom of smashing heaps of cheap china plates on the floor at celebratory occasions, such as weddings (Figure 2). Popularised in film as synonymous with kefi (a Greek sense of fun), the custom was banned in the 1960s by the Greek military dictatorship as demeaning of their conception of Greekness. It persisted, regardless, and has been interpreted by anthropologists as a demonstration of 'unconstrained independence' and a 'creative presentation of the individual self' vis-à-vis the formal image of a national collective self (Herzfeld 1997:x).

In her performance, Krista Papista smashes plates on a wall, where a Greek flag with red instead of blue stripes is hanging and a video is projected with Cypriot folk dances performed by an archetype of Cypriot masculinity, the vrakas, here demonstrating male dexterity and accomplishment by towering drinking glasses over one's head. To unpick the symbolic statement of the gesture, and its vandalism, one needs to consider Cyprus as a place where the rivalry over territorial control translates into competition between Greek and Turkish nationalisms and over the prevalence of symbols, such as that of the Greek and Turkish flag. By merging their design and colour, Krista Papista meddles with their iconic status to create her own emblem with allusions to menstrual blood, sacrifice, love, sexuality and passion. In this case, however, she is not just appropriating a symbol. She is recasting a custom. She smashes plates not on the floor as it is usually the case, but on the wall as an expression of anger and power (rather than of fun), as if in protest against those enduring icons of patriarchy, including the dexterous, athletic, strong and therefore hypermasculine folk dancer. Queer use, in this case, becomes protest.

Interestingly, in Caravaggio (2019), another sound-portrait in which she considers similar ideas in relation to the visuality of the Cypriot landscape, Krista Papista pits against this expression of masculine superiority, a reconsidered version of the Cypriot peasant-woman. Wearing a costume11 that resembles the traditional attire of women in villages (Figure 3), she roams the Cypriot countryside half-naked, disrupting the long thread of visual negotiations of the peasant-woman in Cyprus as a figure of asexual motherhood depicted against unspoilt or conflict-ridden landscapes. Such representations speak of her purity or of her pain and sacrifice but most certainly of the kind of visions of womanhood required - chaste, unsophisticated, removed from the charged context of history and sex - in constructions of nationhood (Yuval-Davis 1997:5-6,26-37; Hadjipavlou 2010:40).

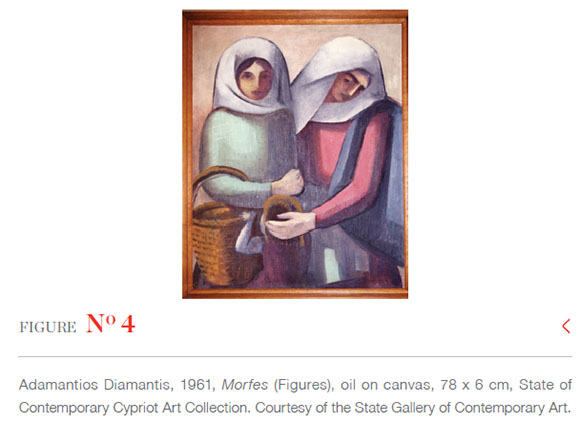

Take for example, the work of painter Adamantios Diamantis (1900-1994), considered a key representative of the first generation of Cypriot artists. Although in his early works dating from the 1930s, women are shown in rural landscapes engaged in various activities (working the land, carrying water, gossiping, tending to children and animals), in his later works they ossify into idealised representations of peasant-women (Figure 4). Invested with tropes of motherhood and allusions to the Christian Virgin Mary, these women are depicted as immobile, monument-like, resembling the freestanding Ancient Greek statues of kore, against landscapes that appear unspecified, timeless, and archetypal like the symbol of femininity they serve to maintain.

Readings of his work point to how the peasant-woman as visual archetype functioned to inflect his modernism with ideological references to the Hellenic heritage and national identity of the island during colonial times (Danos 2014). They also suggest the transformation of the peasant-woman into a symbol of Cyprus, during the inter-communal clashes in the post-independence period (Danos 2014). When examining, however, the longer history of the visual encoding of Cypriot women as peasants to symbolise the island's cultural identity, what becomes apparent is the correspondence of such imaginings with the colonial gaze and its gendered stereotypes.12 For instance, the Cypriot peasant-woman was one of the most prominent types of Cypriots to emerge from the series of photographic portraits taken by Scottish photographer John Thomson upon the arrival of the British in 1878. Interested in typicality rather than individuality (Philippou 2010:40), and in elements that pointed to the island's cultural lineage with Greece and Europe, Thomson depicts an idealised "Cypriot maiden" against unspecified exteriors - just as Diamantis in his paintings decades later. In effect, all emphasis is placed on the figure's grace, prosaicness and non-sophistication, attributes aimed to parallel at once the new protectorate's noble heritage and its backwardness, thus offering justification to the coloniser's arrival.

Considering Krista Papista's sound portrait within the context of such historical visual representations of Cypriot women as peasants encourages reflections over the versions of femininity revered in a place marked by colonialism, ethnic division and conflict. It also points to how artists such as Krista Papista, with her chest bare and nipples exposed, seek to widen the conception of femininity by making queer use and disrupting - much in the same way as her reclamations of the Greek flag or of Nicosia's conflict-ridden spaces - the iconic status of a gendered stereotype (Figure 5). It is important to consider that this occurs while trying to dwell, occupy and orient herself in the Cypriot landscape.

To orient oneself, Ahmed (2006:208) reminds us, is about finding one's way. Hence, in her phenomenological reading of sexual orientation, she encourages the consideration of the spatiality of sexuality and gender by reflecting on what happens when bodies abandon the grid of compulsory heterosexual direction to form their own set of bodily relations to their surroundings. An important question to consider in parallel to these ideas concerns the kind of liaisons effected between bodies -that do not fall into easy categorisations - and places that are, correspondingly, in a state of indeterminacy. Geographically located between East and West, Cyprus has been interpreted to exist on the crossover of two cultural poles with colonial underpinnings: the Orient and the Occident. Indeed, while its landscape during British colonial rule has been visually romanticised as half-oriental, half-occidental (Philippou 2014), in the years post-independence it was re-envisioned to adjust to the postcolonial dream of a new republic and a tourist haven with a modern profile (Daskalaki 2017). Having said this, it cannot be neglected how such visions were intercepted, in the years following the intercommunal conflict, by the plethora of visual depictions, in which the Cypriot landscape is represented as laden with incidents of invasion, division, displacement and dispossession. The question of orientation, here, relates to finding one's direction and position not only in the landscape but also in the visual culture defining it, tainted by colonial and masculinist fields of vision that produce specific ideas about femininity, cultural identity and history.

In Caravaggio, Krista Papista's orientation in the landscape entails the energetic movements of the female body in nature, which, although tapping into the stereotype of encoding woman as nature and nature as woman, invite the consideration of ways to journey, experience and gaze upon the landscape - and by extent the body in it - that do not rely on essentialist interpretations. They are also about allowing microhistories that deviate from grand narratives to come to the fore. This is particularly evidenced in the quasi-ritualistic, paganistic performances that occur in the video, which include lighting candles and dancing next to a wooden structure on the shores of a dam. In post-Independence Cyprus, dams (as well as highways, ports and hotels) came to symbolise the island's modern identity contra its colonial past (Daskalaki 2017:2). In recent years, however, they made headlines as the sites where a serial killer, an officer in the National Guard, was burying his women victims. With elements of spirituality of her own invention that entwine with poses of an energetic sexuality, the rituals enacted by Krista Papista in the video - or so the viewers are invited to assume - are about casting out the evil and reclaiming the landscape as well as the feminine, from the spectre of hegemonic masculinity and the violence it produces. Whether positioning herself, then, against local customs and traditions, gendered stereotypes or specific landscapes, Krista Papista embraces an uncompromising position of criticality and infuses the topos of belonging and identity with experiences, narratives, uses of objects and emblems that point to orientations which deviate from official routes.

Resisting categorisation: Cypriot identity in Hasan Aksaygin's Little Phanourios (2020)

Writing on artists from Cyprus often necessitates the negotiation of a balancing viewpoint, prescribed by rules of equal representation. The consideration, however, of the work of Hasan Aksaygin in this section concerns less the demands of political correctness and more the reflection of the way queerness may allow for spaces of affinity and communal connection to emerge beyond essentialising narratives. Aksaygin's practice involves painting and elements of performance, sometimes developed on the basis of a collaboration between Hasan, as in the artist himself, who responds to the pronouns he and him, and Hank Yan Agassi, a post-human mutation with an AI-generated anagram of Hasan's name, responding to the pronoun it. The split can be interpreted as speaking to the island's division but also to how the artist's identity - ethnic, gender, sexual, cultural - is negotiated between supposedly opposing polarities: that of the Turk and the Greek, the feminine and the masculine, the oriental and occidental.

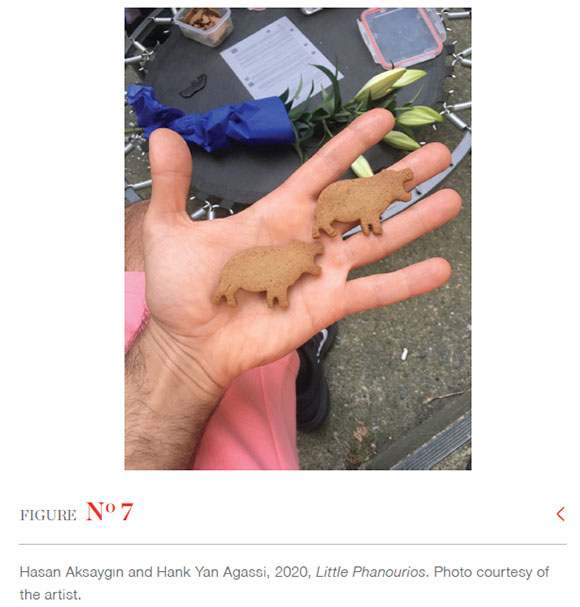

Little Phanourios (2020) is a work that springs from such debated binaries as a collaboration between Hasan and Hank who are seen standing on a trampoline reading a story that blends fact with fiction (Figure 6).13 The fact concerns a species of pygmy hippopotamus, which inhabited Cyprus until the early Holocene, but was hunted to extinction by humans, who would later revere the animal's bones as the petrified remains of Saint Phanourios, the saint of lost things in Greek Orthodox tradition. To account for this custom, scholars named the Cypriot pygmy hippopotamus, Phanourios Minutus, as in "Little Phanourios". In Hasan and Hank's story, Cypriots resurrect the animal with the aid of biotechnology. Yet, genetic malfunctions due to inbreeding lead to the experiment's failure, shattering the Cypriots' dream of using ecology-related projects to derail attention from the island's ethnopolitical quandary. Only a single dwarf hippo survived, named after the Christian saint as a pledge to help recover the lost species, which in Hasan and Hank's story comes to symbolise the island's queer population also threatened with extinction due to its marginalisation. The reading of the story is completed with the offering of phanouropitta in the shape of hippo biscuits - phanouropitta is the pie that must be baked, according to Greek Orthodox custom, when a pledge is made to the saint for finding lost things and people (Figure 7).

Critical examinations of Cypriot folklore have brought to attention the way cultural attributes, perceived in individualistic and adversarial terms, are seen as preserving the authentic national culture that each community considers its own (Azgin & Papadakis 1998). In this sense, Aksaygin's queer use of Saint Phanourios's story and relating customs can be read as a form of attack on the customs and traditions of the rival ethnic other. A more nuanced interpretation, however, would permit the acknowledgement of the way the artist is engaged in acts of appropriation aimed at unlocking new meanings, just like Krista Papista in Ethnopapistology. Yet, while the latter's turn to queer use is meant as a disruption, Aksaygin's seems directed at bringing incompatible things together. It activates spaces for envisioning the island's bicommunality by encouraging an alternative conception of Cypriot identity built not on dominant narratives, which demand adherence to the nuclear family, to reproduction, to binary conceptions of gender and cultural heritage and traditions, but playfully and queerly on the crossover of a dwarf hippo with a Christian saint. In this, the artist's approach resonates with Ahmed's (2019:198,199-200) additional understanding of queer use as making connections between things that might otherwise be assumed to be apart, opening up the possibility for those regarded as "others" to inhabit spaces previously inaccessible. After all, the artist makes visible the queer body of a Turkish Cypriot where it is usually believed to have no place - the corpus of the Greek Orthodox tradition. Here Aksaygin converses with Krista Papista in her resolve to take the claim of visibility for the female queer body to the Cypriot countryside, the bedrock of tradition and heterosexuality on the island, where women's roles were prescribed in delimiting terms. In both cases, an alternative topos is produced. Not in an unexplored place on the horizon, but in the here and now, through queer uses of elements of culture and heritage, and in the interstices of fact, fiction storytelling, audience participation, performance, music, non-conforming sexualities and genders.

It is interesting to observe that such approaches in the visual arts in Cyprus relate to recent initiatives undertaken by members of the queer community south of the divide. Consider the example of The Gathering organised yearly in the village of Kampia by record label Honest Electronics. Although the event began as a festival in 2016 seeking to promote local underground talent working with music and sound, in its later iterations it developed into a platform of expression for queer artists. Through their activities, the village in the countryside, a resonant symbol of stability in idealised representations of rural life in Cyprus, became an object of queer use. It was reconceptualised as a transgressive space, where people of different social norms, gender and sexual roles were invited to exist in nature and in conditions that resisted categorisation and control.

In this respect, events such as The Gathering can be seen as conversant with deviant community-building practices, in which queer use associates with the creation of alternative modes of togetherness. For example, in his examination of the formation of queer urban subcultures in the US in the 1990s, Jack Halberstam (2003) has explained queer use as developed in opposition to the institutions of the family, heterosexuality and reproduction - the triad, one should be reminded, on which the survival of the nation depends - to produce alternative temporalities, senses of community and habitations of space. Although springing from a significantly different socio-political context, The Gathering can be recognised to delineate a topos for queer belonging through shared reactions to art, dancing and performance, which inspire feelings of community and non-conforming kinship that permit the emergence of queer subjectivities with unapologetic determination.

Conclusion

In relevant literature, the development of the visual arts in Cyprus has been recognised as marked by tensions between centre and 'periphery', identity politics, ethnic conflict and borderlands, which are negotiated across the global/local nexus (Stylianou, Tselika & Koureas 2021:1,3). These debates can be inferred too in the work of artists, whose identification as queer invites further consideration of the ways the global interconnects with the local in Cyprus. Having emerged out of specific historical circumstances in Europe and North America, the term 'queer' resonates globally within an increasingly connected world. Its uncritical adoption, however, in various political, religious and national contexts has been seen to carry the danger of its transformation into a 'blanket term' that acknowledges the west as its sole proprietor (Ula 2019:516), erasing the complex ways in which queerness is articulated aesthetically and politically across the world.14 This concern has led to calls for the development of local queer aesthetics and theory that take into consideration political, social and cultural particularities (Ula 2019). Although such debates lie outside the remit of this article, they encourage the acknowledgment that the conscious adoption of a queer identity by Krista Papista and Hasan Aksaygin permits a culturally specific interpretation of queerness to emerge that is inseparable from issues relating to their locality. It is also inextricable from the critical positionality they adopt, which manifests, as I have tried to argue, in techniques of queer use that work to disrupt and challenge existing power relations, nationalist ideologies, practices of marginalisation, and delimiting social and cultural norms. This becomes particularly evident in works that artistically negotiate and queer those elements (traditions, customs, symbols, landscapes and gender stereotypes) that in a divided society conjure a sense of national cohesion or discord. Through such processes, these artists allow the envisioning of a topos that is 'queer in soil', to borrow a verse from the poem in the epigraph of this article, where queer senses of belonging and queer experiences and perspective are at the root of identity.

Notes

1 . Reprinted with the permission of the author. See Petrou (2019).

2 . Despite relevant additions in recent literature on art from Cyprus (Zackheos & Philippou 2021), the practice of Cypriot queer artists remains largely unexplored. In the present article, I seek to contribute to this nascent field of research. The ideas I outline have sprung and continue to grow in parallel to the on-going independent research project, Bending Ground, which I develop in collaboration with artist Leontios Toumpouris and artist, curator and poet Christos Kyriakides. Concentrating on practices of queer sensibilities, the project researches past and current queer artistic practices in seeking to understand how the term "queer" acquires its local specificity in Cyprus vis-à-vis and in relation to its articulation in English-speaking, academic and artistic centres.

3 . Krista Papista is an artistic pseudonym.

4 . The artist prefers the self-invented term of 'sordid pop' (East End Review 2014).

5 . Cypriot Requiem (2019) is available for viewing at the following link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1It75ICLpF4.

6 . A former British colony, Cyprus gained its independence in 1960. In 1963-1964, against the backdrop of resurgent nationalist sentiments fuelled by the rhetoric of Greek and Turkish nationalisms, interethnic enmity escalated into violence between the island's main ethnic communities - the Greek and Turkish Cypriots. In 1974, following a Greek Cypriot coup supported by the Greek junta, Turkey invaded the island, taking control of the northern part and imposing a de facto partition. In 2003, the Turkish Cypriot leadership partly opened checkpoints along the ceasefire line. Commonly referred to as the 'Green Line', it continues to this day to separate the island between the Greek Cypriot controlled, internationally recognised state of the Republic of Cyprus in the south, which is a member of the European Union since 2004; and the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus in the north, which is recognised only by Turkey.

7 . The perspective of this article is unavoidably affected by my own specific positioning as a Greek Cypriot writing and researching along the lines of art history south of the Cyprus divide.

8 . For more on queer as a positionality indicatively see Halperin (1995:62) and Sullivan (2003:3756).

9 . There is now a rich body of literature on the matter which extends across fields including history, political science and anthropology. Indicatively see Attalides (1979), Kizilyürek (1993), Calotychos (1998), Bryant (2004), and Papadakis, Peristianis and Welz (2006).

10 . It should be noted that the island's EU admission and the processes of Europeanisation that this entailed did enable the creation of civil society organisations, such as ACCEPT LGBTI Cyprus in the south and Queer Cyprus Association in the north, which have pushed for changes and reforms. In the view of Kamenou (2020), this was possible due to the organisations' intersectional political action which has afforded opportunities for political mobilisation around issues which, due to the predominance of nationalist ideologies, were previously considered to lie outside the remits of the political.

11 . The costume was designed by queer artist and poet Christos Kyriakides. Such collaborations between queer artists in Cyprus point to how their artistic practices are developed on the basis of teamwork and alliance.

12 . For a discussion of the paradox of colonialism and nationalism's synergetic co-existence in Cypriot art see Stylianou and Philippou (2018).

13 . Little Phanourios was first performed at HOPSCOTCH READING ROOM in Berlin in 2020. The full text of the reading can be viewed here: https://www.hasanaksaygin.com/collaborations/.

14 . For a thought-provoking discussion on these matters see the Winter 2020 issue of the Journal of Body and Gender Research Kohl, entitled 'Queer Feminisms'.

References

Adams, S & Gruetzner Robins, A. 2000. Introduction, in Gendering landscape art, edited by S Adams and A Gruetzner Robins. Manchester: Manchester University Press:1-12. [ Links ]

Ahmed, S. 2006. Queer phenomenology: Orientations, objects, others. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Ahmed, S. 2018. Queer Use. [O]. Available: https://feministkilljoys.com/2018/11/08/queer-use/ Accessed 28 October 2021. [ Links ]

Ahmed, S. 2019. What's the use? Durham and London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Anderson, B. 1983. Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Attalides, M. 1979. Cyprus: Nationalism and international politics. New York: St. Martin's Press. [ Links ]

Azgin, B & Papadakis, Y. 1998. Folklore, in Zypern, edited by KD Grothusen, S Winfried and P Zervakis. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht:703-720. [ Links ]

Bryant, R. 2004. Imagining the modern: The cultures of nationalism in Cyprus. London: I.B. Tauris. [ Links ]

Calotychos, V (ed). 1998. Cyprus and its people: Nation, identity, and experience in an unimaginable community (1955-1997). Boulder: Westview Press. [ Links ]

Delue Ziady, R & Elkins, J. 2008. Art Seminar, in Landscape theory, edited by R Delue Ziady and J Elkins. New York and London: Routledge:87-156. [ Links ]

Danos, A. 2014. Twentieth-century Greek Cypriot art: An "other" modernism on the periphery. Journal of Modern Greek Studies 32(2):217-252. [ Links ]

Daskalaki, G. 2017. Aphrodite's realm: Representations of tourist landscapes in postcolonial Cyprus as symbols of modernization. Architectural Histories 5(1):1-16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ah.198 [ Links ]

Hadjipavlou, M. 2010. Women and change in Cyprus: Feminisms and gender in conflict. London: I.B. Tauris. [ Links ]

Halberstam, J. 2003. What's that smell? Queer temporalities and subcultural lives. International Journal of Cultural Studies 6(3):313-333. [ Links ]

Halperin, DM. 1995. Saint Foucault: Towards a gay hagiography. New York and London: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Herzfeld, M. 1997. Cultural intimacy: Social poetics in the nation-state. New York and London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hobsbawm, E. 1983. Introduction: Inventing traditions, in The invention of tradition, edited by E Hobsbawm and T Ranger. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press:1-14. [ Links ]

Kamenou, N. 2020. Difficult intersections: Nation(alism) and the LGBTIQ movement in Cyprus, in Intersectionality in feminist and queer movements. Confronting privileges, edited by E Evans and E Lépinard. New York and London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kamenou, N. 2011. Queer in Cyprus: National identity and the construction of gender and sexuality, in Queer in Europe, edited by L Downing and R Gillet. Surrey and Burlington, VT: Ashgate:25-40. [ Links ]

Karayanni, SS. 2004. Dancing fear and desire: Race, sexuality, and imperial politics in Middle Eastern dance. Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. [ Links ]

Karayanni, SS. 2017. Zone of passions: A queer re-imagining of Cyprus's "no man's land". Synthesis: An Anglophone Journal of Comparative Literary Studies 0(10):63-81. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12681/syn.16244 [ Links ]

Krista Papista. [Sa]. About. [O]. Available: https://krista-papista.com/about Accessed 1 November 2021. [ Links ]

Kizilyürek, N. 1993. From traditionalism to nationalism and beyond. Cyprus Review 5(2):58-67. [ Links ]

Leontis, A. 1995. Topographies of Hellenism: Mapping the homeland. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Mitchell, WJT. 2000. Holy landscape: Israel, Palestine, and the American wilderness. Critical Inquiry 26(2):193-223. [ Links ]

Mitchell, WJT. 2002. Imperial landscape, in Landscape and power, edited by WJT Mitchell. Chicago: Chicago University Press:5-34. [ Links ]

Mosse, GL. 1985. Nationalism and sexuality: Middle-class morality and sexual norms in modern Europe. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [ Links ]

Muñoz, JE. 2009. Cruising utopia: The then and there of queer futurity. New York and London: NYU Press. [ Links ]

Papadakis, Y, Peristianis, N & Welz, G (eds). 2006. Divided Cyprus: Modernity, history, and an island in conflict. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Petrou, Y. 2019. I take of places, in Modern queer poets, edited by R Porter. London: Pilot Press. [ Links ]

Philippou, N. 2010. Cypriot vernacular photography: Representing the self, in Re- Envisioning Cyprus, edited by P Loizos, N Philippou and T Stylianou-Lambert. Nicosia: University of Nicosia Press:39-51. [ Links ]

Philippou, N. 2014. The National Geographic and half oriental Cyprus, in Photography and Cyprus: Time, place and identity, edited by L Wells, T Stylianou-Lambert & N Philippou. London: I.B. Tauris:28-52. [ Links ]

Sullivan, N. 2003. Introduction to queer theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [ Links ]

Ula, D. 2019. Toward a local queer aesthetic: Nilbar Güreş's photography and female homoerotic intimacy. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 25(4):513-543. DOI: 10.1215/10642684-7767752 [ Links ]

Sayegh, G & Allouche, S (eds). 2020. Queer feminisms. Kohl 6(3). [ Links ]

Stylianou, E, Tselika, E and Koureas, G (eds). 2021. Contemporary art from Cyprus: Politics, identities and cultures across borders. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Stylianou, E & Philippou, N. 2018. Greek-Cypriot Locality: (Re) Defining our Understanding of European Modernity, in A Companion to Modern Art, edited by Pam Meecham. London: John Wiley:340-358. [ Links ]

Whiston-Spirn, A. 2009. The language of landscape. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Yuval-Davis, N. 1997. Gender and nation. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Zackheos, M & Philippou, N. 2021. Nicosia's queer art subculture: Outside and inside formal institutions, in Contemporary art from Cyprus: Politics, identities and cultures across borders, edited by E Stylianou, E Tselika and G Koureas. London: Bloomsbury:119-136. [ Links ]