Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a19

ARTICLES

In search of a 'POST': The rise of Cosmism in contemporary Russian culture

Julia Tikhonova Wintner

Coordinator of Gallery and Museum Services, Eastern Connecticut State University Fine Arts Instructional Center (FAIC) 111, Willimantic, United States of America wintnerj@easternct.edu (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8172-1832)

ABSTRACT

The landscape of contemporary Russian culture is ground zero for the recent revival of Cosmism, the late nineteenth century utopian quest for immortality and space colonisation. Overwhelmed, as we are in the west, with accounts of geo-political conflicts with Russia, it is especially timely to interrogate the underlying social narratives that are inseparable from these conflicts. To do so, we must simultaneously juggle the discourse of post-colonial studies, a close look at the circulation of nationalism, the nostalgia for Soviet times, an explosion of religiosity, and the ideological and cultural work being done by the prominent cosmist devotees, Anton Vidokle and Arseny Zhilyaev.

'In search of a "POST": The rise of Cosmism in contemporary Russian culture' navigates through the specter of contemporary neo-liberal Russian culture on its way to Cosmism's other-worldly narrative of a cult of the ancestors and the immortality for all. Since the 2000s Cosmism has entered intellectual vogue. Touted as a harbinger of post-humanist ideas,1 it offered a vastly different view of the future, one that blurred the borders between the scientific, the religious and the fantastical (Smith 2016:4). Cosmism thus appears to function as a temporary refuge from the human denigration subsequent to the Fall of the Soviet Union and, more recently, the death caused by the Covid-19 Pandemic. Cosmism's focus on theorising is at the expense of formal explorations and new visual languages. They are not challenging the status quo but perpetuating centuries' old Russian traditions of millenarism2 and mystical fabulism and thereby not promoting any real advancement in constructing a new identity for a post-Soviet society.

Keywords: post-Soviet condition, Soviet Empire, postcolonial theory, Russian avant-garde, Cosmism, Nikolai Fedorov, Anton Vidokle, Madina Tlostanova.

Russia's revolutionary millenarian movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that have left their impact are well known to scholars: Narodniks,3 Decembrists,4 Theosophists,5 Bolsheviks,6 Leninists,7 and Futurists,8 all proposed a rupture with prior spiritual and political traditions. But one such movement is less well remembered: Cosmism, the late nineteenth century utopian quest for immortality and space colonisation, envisioned by philosopher and mystic Nikolai Federov.9

I am a Russian born and educated curator. Recently, I have been fascinated to discover that the world of contemporary Russian culture has experienced a new revival of Cosmism. Bombarded as we are in the west with accounts of our existential conflicts with Russia, it is especially timely to interrogate the social narratives - like Cosmism - critical to Russian identity. To do so, we must simultaneously juggle post-colonial studies, the circulation of nationalism, Soviet time nostalgia, explosion of religiosity and the important ideological and cultural work being done by the prominent artists and Cosmist devotees, Anton Vidokle and Arseny Zhilyaev.

I began this study by seeking to understand if the insights of postcolonial studies could be applied to post-soviet Russia. I discovered that it was the condition of "post-ness" itself that would prove critical to my understanding of the social dynamic of Cosmism. Kwame Anthony Appiah provides guidance with his enlightening analysis of the post- signifier, suggesting it always means a negation of the past - in other words, a rupture significant enough to leave the past behind, and begin building a new social reality. He states, 'the post- in postcolonial, like the post- in postmodern, is the post- of the space-clearing gesture' (Appiah 1991:4). In trading one autocratic state for another, the tumult of 1989 did not generate the required rupture with the past.10 In haste, Russian society moved into the twenty-first century holding fast to the same imperatives of colonialism, nationalism, and autocracy common to the Tsarist and Soviet regimes (Suny 2017:14). Alexander Etkind (2013:27) echoes Appiah in proposing that the unexamined nature of the Soviet past has left Russia a melancholic nation, unable to fabricate the rupture that would have allowed the seeds of democracy to flourish. Instead, contemporary Russia has sought inspiration for transformative social narratives in its pre-revolutionary history. In this paper I show that in the past decade this lack of a real rupture has left an opening for Cosmism's obscure nineteenth century spiritual teachings to re-emerge. I focus on the ways in which Cosmism's other-worldly narrative has achieved its current status amongst a cultural elite, while Russian society remains bereft of what Appiah (cited by Boczkowska 2016:234) defines as a 'new, legitimating narrative' - one based on a vision of 'heaven on earth' and not, as in Cosmism, in outer-space and immortality.

The collapse of socialism in Russia was followed by a dark and oppressive period of political restoration and cultural despair - titled Thermidor.11 This term refers to a collective nostalgia for socialism and an accompanying cultural amnesia, cushioned by a newfound prosperity, which haunts contemporary Russia. Russians are expected to forget their socialist past - yet the harsh memories of those years undermine the neo-liberal euphoria of the Putin era and the people do not forget. While writers and artists have identified themselves as heirs to the early twentieth century Russian avant-garde, the masses continue to identify with the Russia they knew as a Cold War superpower. Russophilia,12 millenarianism, and faux science overshadow democracy, reason, and scholarly research in the absence of a 'space-clearing gesture' (Appiah 1991:4). Cosmists have risen to prominence through their support of the orthodox church, cryonicists,13 and immortalists.14

Russian contemporary artists have responded by embracing the country's tradition of revolutionary millenarianism - in particular Cosmism, a quasi-religious, philosophical mix of utopian dreaming and planetary expansionism that emerged at the turn of the twentieth century. Its founder, philosopher Nikolai Fyodorov, imagined that humanity should put their faith in technological progress as a means of achieving universal salvation. As Richard Stites (1991:45) noted about that era, 'Russian revolutionary Utopias contained an abundance of star-gazing - sometimes in the literal sense of cosmic thinking and space fantasy, sometimes in the figurative sense of social daydreaming and scheming new social orders'. This promised colonisation of outer space inspired many early Bolsheviks along with the avantgarde writers and artists who were attracted by Cosmism's ambition to create a classless society.

Politically, Cosmism was desirable for its technocratic aims, which were in accord with the Soviet Union's frantic race to industrialise. At the same time, it offered a much-needed outlet for the population's nationalist, expansionist, and spiritual ambitions. Alexander Chizevsky (1936:132) claimed that the history of humankind is shaped by the 11-year cycle in the sun's activity, and is manifest in political events: revolts, wars, revolutions.15 This new discipline, called "historiometry" was intended to legitimate bolshevik Russia's imperial ambitions from a planetary and cosmic perspective.16

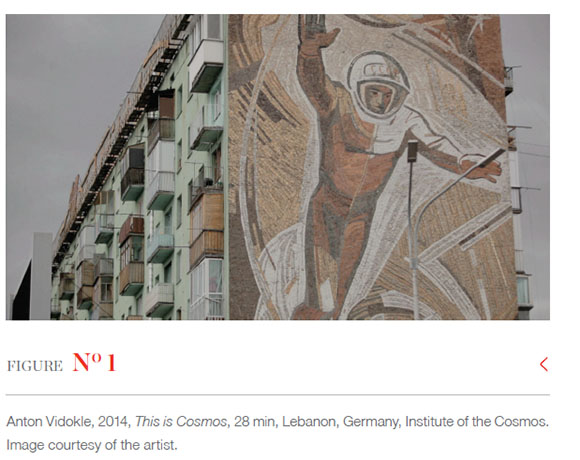

During Khrushchev's time (1954-1964), the public image of space research was promoted by the government as a form of 'celebratory theatrics' (Andrews 2010:1). Cosmonauts played a particularly iconic role as symbols of the great achievements of the Soviet socio-political system and the dawn of the space age, with its promise of the "storming of heaven".17 Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was "canonised" as a symbol of this history. Popular adulation for space heroes continued during the Khrushchev era and into Brezhnev's reign (1964-1982). The propagandistic cosmic spectacle made its way into the hearts of the "masses", swelling national pride in Soviet science as the finest in the world.

Cosmism has captured artists' imaginations in other eras. In the early 1970s, interest in Cosmism began circulating in the artistic community. Its utopian fabulism contrasted with the daunting dissonance of ideology and peoples' lives in the Soviet era. The pictorial works of Soviet dissident artists Ilya Kabakov (Groys 2019:23) and Erik Bulatov envisioned the cosmos as a site of liberation from a stultified Soviet reality. Out-of-the-window-straight-to-cosmos flying characters populated novels by Sergey Bulgakov and paintings by Kabakov. Such ability to fly - concretely into outer space, or allegorically toward a creative act or God - captured this liberatory appeal. Vitality Komar and Alexander Melamid, the celebrated Soviet artistic duo, confronted the pervasive presence of the cosmos in the government's space propaganda.18 Pavel Papershtein's poignant paintings and graphic works, too, situate cosmic yearnings at the spiritual core of Soviet Marxism (Simakova 2014:12).

The list of artists who allied themselves with cosmic visions is long. Writers, poets, and magical realists narrated their own fantastical scenarios that were in stark contrast to the earth-bound materialism of Soviet doctrine (Curtis 2013:25). The writers Sergey Bulgakov, Andrei Platonov, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Vladimir Sorokin, and others, created dystopian fictions and absurdist parables that anticipated the finale of a crumbling Soviet Empire. Many of them adopted Cosmism as their guide through the ideological paradoxes of the Soviet times.

The Covid-19 pandemic's vast death toll provided Cosmism with a seductive opening to the international arena. Anton Vidokle (2020:3) said:

A conversation about immortality acquires a lot more meaning when we are in the middle of a pandemic and so many people are sick and dying. I think this present moment is a bit similar to the original context that triggered cosmism: all the epidemics, droughts, and famines in nineteenth-century Russia.

Its promise of immortality and resurrection assuaged fears of environmental collapse. Cosmism has appealed to that portion of the Russian intelligentsia who has never lost faith for a revival of Russian leadership. Cosmism has served as a refuge from the lack of a revolutionary secular response - a rupture - it is a temporary, but inadequate placeholder.

***

The artists discussed here, Anton Vidokle and Arseny Zhilyaev, both turned to Cosmism for the same reasons. They reach back to the pre-Soviet past and the religious symbolism that was pervasive in that era. For them, Cosmism is not a call for action, it is a return to Russian millenarianism.

Vidokle has produced six films, beginning in 2014. The first three comprise the trilogy Immortality for All! (2014-2017). On average 30 minutes each, each film addresses a different aspect of Cosmism. Vidokle (2021:23) states 'In 2013, I discovered this profoundly visionary but forgotten philosophy' (Figure 2). Cosmism's humanistic, caring sentiments prompted Vidokle to pursue this creative journey. He uses Cosmism's contradictions as a malleable clay with which to create an atmosphere of estrangement and distancing. Vidokle, who is the founder of the highly regarded e-Flux web platform, emerged as an artist-curator in 2004, with his street performances in Berlin. His fascination with Cosmism led to three additional films: Citizens of Cosmos (2019), The God-Building Theory (2020) and Autotrofia (2021). All six films are available on the website of the Institute of the Cosmos - a comprehensive portal documenting symposiums, publications, and artworks that have fashioned Cosmism into a potent rhetorical movement that deserves serious attention from researchers and academics. Institute of the Cosmos' library features papers ranging from transhumanism to afro-cosmologies, and from cryonics to genomics. Vidokle has successfully leveraged his international profile to draw attention to Cosmism. It is no longer a parochial teaching but an international movement. At the same time, they have abandoned the historical role of Russian artists as having the moral force and power of a 'second government', as described by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1960:4). Cosmists are not risking their lives like Pussy Riot19 or Pyotr Pavlensky20 did (Eberstadt 2019:3). They will not be put in jail for their verbose mind-boggling concepts comprised of Cosmism's conundrums and mysticisms.

The first film in the trilogy is Immortality for All!. It is a foray into Soviet era nostalgia comprising several non-linear narratives. Blocks of flats and factories share the screen with bucolic family swimming weekends. Drone-like music accompanies this found footage of typically Soviet, sentimental images of the Moscow, Arkhangelsk, Altai, Kazakhstan and Crimea, which have all played an important role in the history of the movement. A voice-over recites Fedorov's nineteenth-century prose: 'Because the energy of the cosmos is indestructible; because true religion is a cult of the ancestors; because true social equality means immortality for all; we must resurrect our ancestors from cosmic particles'. Parts of the film are devoted to images of Cosmist devotees among the early avant-garde such as Malevich and Rodchenko. English subtitles have allowed Vidokle's concepts to be shared with an international audience. He highlights the foundation of Cosmist egalitarianism - the desire for connectedness between people and generations. Vidokle (2018:45) says about the film: 'Essentially, it is light, color, and sound, and all of these means can produce a therapeutic effect on the human organism'. To illustrate Cosmism's therapeutic theory, Vidokle introduces red flashing screens throughout the film, inspired by NASA's red-light treatment used to heal skin wounds.

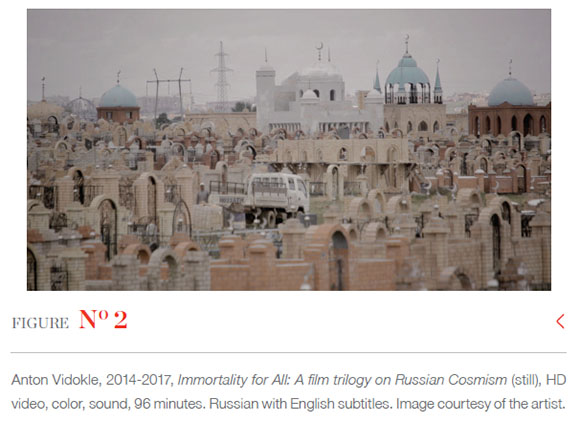

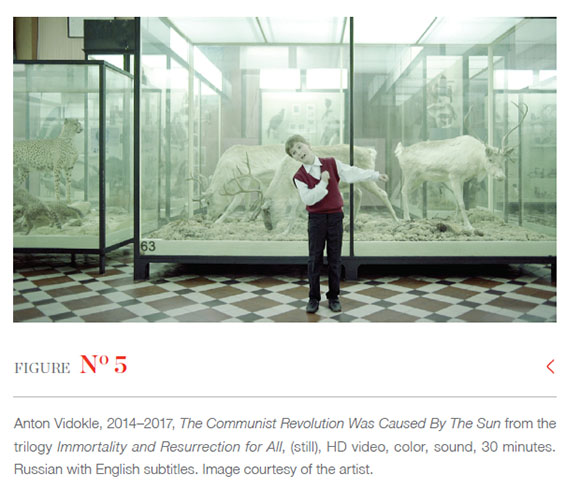

Vidokle's second film, The Communist Revolution was Caused by the Sun, pans across the time and space of ex-Soviet Kazakhstan. During Stalin's epoch, this republic was effectively a colony, used as a mass-labour camp housing up to one million prisoners (Ventsel 2021:3). It also served as a trampoline for the Soviet space program - Russia's equivalent to NASA's Houston Space Center. Currently, Kazakhstan's economic and cultural landscape exemplifies their postcolonial condition. Soviet governments believed that the "stans" would skip the historical stages of feudalism and capitalism, and leap straight into a socialist, and eventually, communist future. This leap, along with many other Russian god-building utopias, was never attained. Ultimately, these countries were left in disarray (Tlostanova 2015:56). Their futility and otherness is highlighted by hypnotic script narrated by a voice-over that opens and concludes the film. Vidokle incorporates elements of clinical hypnosis that are commonly employed to break addictions. In this case, according to Vidokle (2019:62), he targes 'the addiction to mortality - the death drive' which causes the stagnation of the "stans".

A surreal element is the unseen protagonist of this film, the notable Russian scientist Alexander Chizhevsky, who is represented by a chandelier being constructed under a blazing sun. Vidokle references Chizhevsky's focus on the meta-historical and poetic dimension of solar cosmology. A woman wearing a white lab overall quotes Chizhevsky:

Sun exerts an influence on the biologic, psychological and social spheres of human activity. Therefore, the Sun influences the rhythm of all historical processes. Every eleven years a new historiometric cycle begins. At the end of each cycle the unity of the people disintegrates. Mystical, occult teachings, and maniacal ideas gain in circulation. Mass physiological delusions are common and psychotic epidemic prevail (Vidokle 2019:89).

Towards the end of the film, the voice-over describes Chizhevsky's fate:

Following the publication of his study, the scientist was invited to lecture at Columbia University in New York and was nominated for a Nobel Prize in science. On his return to Russia, he was arrested and sent to a labor camp because one possible interpretation of his work could lead to the conclusion that 'the Communist Revolution was caused by the sun' (Vidokle 2017:100).

These incantations are performed in a soothing voice, as if delivering psychedelic instructions. The narrative oscillates between real and staged footage.

Chizhevsky's imagery is followed by a Muslim cemetery populated by mausoleums in traditional Islamic styles. Two Kazak men are digging a grave; later, we enter a slaughterhouse filled with bovine carcasses. Through these references to mortality, Vidokle conveys a sense of fossilisation and left-behindness. A sense of the impossibility of reversing the devastation caused by the Soviets hovers above the steppes that Vidokle is filming. The wide camera view highlights the vastness of the landscape, suggesting "the master view" and the eye of the coloniser. Vidokle suggests that Soviet socialist modernity has destroyed Kazakstan's indigenous culture. This ex-colonial state is a progeny of the Soviet empire (Figure 5). It is forever colonised , not only by Russians, but also by its own addiction to mortality (Vidokle 2019:156).

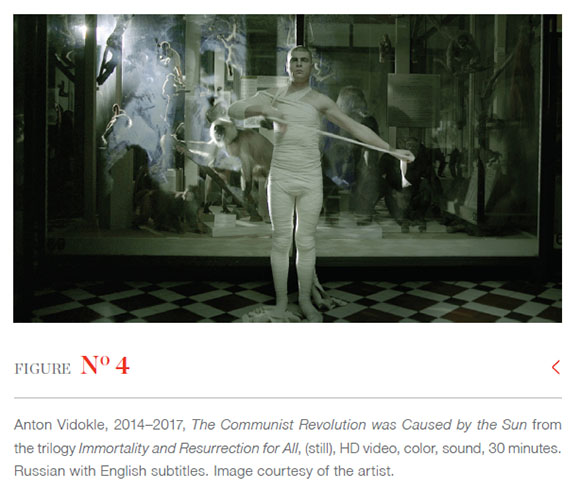

Vidokle's third film, Immortality and Resurrection for All, is filmed at the State Tretyakov Gallery, Lenin Library, and the Museum of Revolution, peopled by a cast of present-day followers of Fedorov. Vidokle illustrates Fedorov's designation of the museum as a site for the restoration of human life. Fedorov claimed that museums needed to be radicalised: that they would not merely collect and preserve artifacts, but also recover life itself. Museums should become factories of resurrection (Fedorov 1906:393). Vidokle zooms into Kazimir Malevich's Black Square21 and Alexander Rodchenko's spatial constructions:22 artists who he and his contemporaries claim as predecessors. Taxidermized foxes bare their sharp teeth, and plastered human mannequins are filmed unraveling strips of plaster (Figure 4). Vidokle leads us through a labyrinth of cases, vitrines, and metal files. He drifts from gallery to gallery, accompanied by the narrator's soothing voice:

One cannot annihilate the museum; like a shadow, it accompanies life, like a grave, it is behind all the living. Each man bears a museum within himself. .as a dead appendage, as a corpse. For the museum, death itself is not the end but only the beginning; an underground kingdom that was considered hell is even a special department within the museum. It is necessary that all the living unite as brothers in the temple of ancestors, or the museum where all worlds would be united in resurrected generations (Fedorov 1906:385).

The taxidermies defy all manner of common-sense expectation and inspire in us the uncanny feeling of being watched. Vidokle employs bleaching light filters to create effects of emotional coldness - dispassionate separation between the museum display and his audience. The film embodies the type of museum that has been widely criticised as a site of dispossession - a cemetery of objects removed from their context of daily use. Instead of providing a path for resurrection, we feel as if we have been thrown into a cryonics chamber.

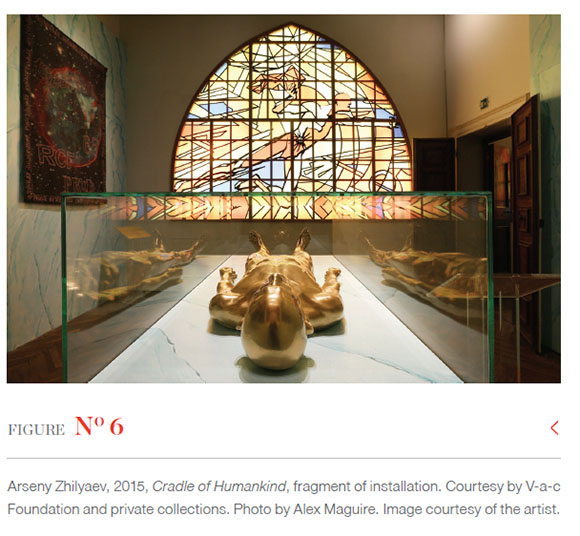

A parallel fascination with museums is the focus of Arseny Zhilyaev's last decade of installations, research, and publications. Zhilyaev draws his inspiration from the avant-garde museologies of the early twentieth century that advocated the didactic power of exhibitions in the process of forging the new type of socialist worker. As per his professional website biography, Zhilyaev proudly declares himself a historical, museological, and artistic revisionist and futurologist. He writes of himself: 'Zhilyaev explores a productive space between fiction and non-fiction utilizing artistic, political, and scientific narratives. He casts a revisionist lens on the heritage of Soviet museology'.23 Specifically, the artist echoes Rodchenko's model of the multi-purpose Workers' Club designed to disseminate Bolshevik propaganda.24 However, he removes the club's original, exuberant dedication to the revolutionary project. For Zhilyaev, the museum exhibition is the medium through which the viewer can study, comprehend, and even let themselves be converted - to Cosmism. His installations are formal, dispassionate, and apolitical.

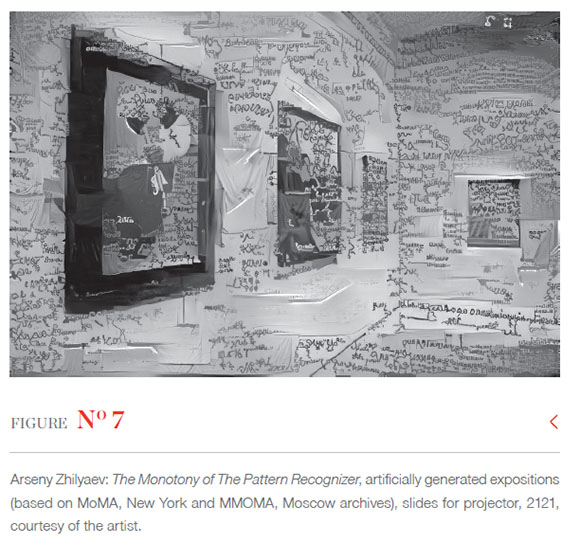

Zhilyaev's most recent exhibition in September 2021, TENET. The Monotony of The Pattern Recognizer, at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, presents over a hundred works, including canvases painted in white acrylic with embroidered ASCII text describing the artist's own fictional story about a freight spaceship lost in some faraway quadrant of the universe, TENET. The name is unrelated to the recent sci-fi film Tenet by Christopher Nolan, that was a blockbuster in Russia.25 Zhilyaev's TENET is also an AI brain that reconstructs the whole history of European art, from the Roman empire to modernity, depicted in white canvases. The exhibition was reviewed as neither arresting nor bland to look at, boring enough to prompt longing for artistic mavericks who are ready to foray beyond these mind-boggling stories and address real politics (Diaconov 2021:1). Curator Maria Lind commented that TENET suffers from over-intellectualisation. This is a trend that she notes among Russian artists working in either Moscow or St. Petersburg. She states:

I am noticing that [the artist] likes to speak about 'his theory' of this or that, even 'his philosophy' of something or other. Such theoretical and philosophical constructions tend to appear more voluminous than the actual artistic production, almost like communicating vessels: the thicker the theoretical and philosophical construct, the thinner is the art itself (Lind 2021:1) (Figure 6).

TENET echoes the artist-serving, arcane intellectualisation, observed by Lind. Its lackluster aesthetic is matched by its cryptic concept.

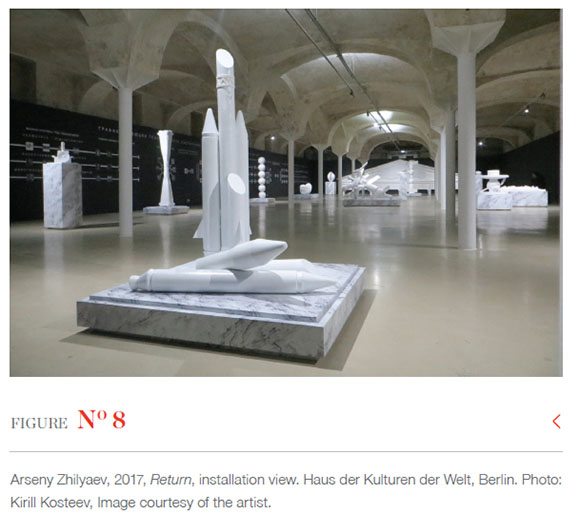

Zhilyaev's Tsiolkovsky. Second Advent (2017) is, like TENET, a combination of loosely connected sculptural objects. It celebrates the renown Russian space scientist and rocket designer, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. Zhilyaev's painting of the Trinity replaces Christ with a spaceship, and all of the apostles with the image of Tsiolkovsky, marking the glorious return of the scientist. A life-size, gilded figure of Yuri Gagarin rests horizontally on the raised wood surface covered by a plexiglass box, similar to Lenin's embalmed body in its now defunct mausoleum. Twenty gilded Maneki Neko fortune cats rest on a low horizontal pedestal as they wave their paws in salute to Tsiolkovsky (Tsiolkovsky 1924:4). This ceremonial display is a reference to the Immortality Museum, a concept invented by Boris Groys in homage to Fedorov. Boris Groys (2016:25) explains his premise:

The Christian concept of the immortal soul with its promise of paradise was replaced in Cosmism with the idea of a global museum, understood as a vault for immortal human bodies. Cosmists imagined an ideal order in time and society, treated as art projects that were to be immortalized by the museum-state (Figures 7 and 8).

Zhilyaev combines religious, political, and scientific narratives to produce a conceptual umbrella for the individual sculptures that are artistically interesting but fail to bond to each other and support his intent.

The installation, Intergalactic Mobile Fedorov Museum-Library (2017) in Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, features the figure of Christ, preaching, in the centre of an extended library desk shaped as a five-pointed star. Christ's image is inlayed, surrounded by elaborate portraits of Fedorov, Tsiolkovsky and other founding fathers of Cosmism. The axioms of Cosmism are painted in old Slavic fonts and frame the portraits. A multi-lingual collection of books on Russian Cosmism is available for loan. Molly Nesbit (2021:2) writes:

If only he could wake up, Nikolai Fedorov would be very surprised. He has gone from being merely an unknown writer, who wanted, all at once, to rewrite the New Testament's Book of Revelation, and to solve mankind's greatest existential problems. Currently Fedorov is being celebrated as the father of Cosmism.

Zhilyaev continues to chronicle Cosmism's narratives in Laborer of the Sun (2016) which is a museological altar of sorts, used by a future space sect. Zhilyaev arranges black solar panels on the wall, a sly tribute to Malevich's Black Square. His wall text imagines a civilisation of sun worshippers who have spread into outer space, abandoning earth. However, they occasionally return to visit museums, where the historical archives of humanity's past are preserved. Zhilyaev parodies the Immortality Museum which, according to Fedorov (1906:400), 'will transform the blind force of nature into one that is directed by reason'.

I suggest that Zhilyaev's immersive installations model Soviet public and private spaces formally and conceptually. The artist sets rules for engaging with his works using detailed wall texts and specified pathways. Zhilyaev's installations illustrate his concept of the museum as 'an institution of superior authority. The Museum has a transformative power over the individual, artist, and artwork. It is its job to unveil authoritatively the true nature of reality' (Franceschini 2017). Heavy-handed exposition, agenda-driven facts, and hidden assumptions about the viewer are common traits of Zhilyaev's "total installations", mimicking a genre originated by Kabakov, who, in the 1980 and 90s, expanded his installations through an "all-over" approach. He furnished exhibition spaces with images, texts, objects, and sounds to dissolve the borders between the art experience and its environment. The atmosphere of arrested time and entrapments pervade Kabakov's total installation.26While Kabakov referenced the miserable lifestyle of overcrowded Soviet urban housing, Zhilyaev creates fantastic spaces where Russian Orthodox apostles appear side by side with cosmonauts and Cosmist immortalists. His vision of the future is un-welcoming: populated by ghosts and the dead.

Evidently, Zhilyaev is more concerned with the discursive aspect of Cosmism than in rethinking the aesthetics of the museum experience. Both he and Vidokle reproduce the old-fashioned museum with didactic moralising and pompous displays. I am not alone in this interpretation. Overall, Cosmists have been criticised for their detached, potentially escapist, futurist focus, and their lack of any engagement with the political realities of contemporary Russia. Curator Olga Kopenkina (2015:4) writes: 'Today, Russian contemporary artists seem to be making a deliberate choice to disengage with public debate and struggle. They, unlike artists before them, have resources and funding, but don't use them as an opportunity to voice out criticism'. Cosmism is a refuge from the void produced by the cult of neo-liberalism. Its oppositional forces mirror the intellectual confusion of the post-Soviet generation. Molly Nesbit (2021b) calls it 'a garden of forking but broken paths'.

••· Coda

In my opinion, Cosmism will never lead to the rupture that would create a true postSoviet society. The artists aim to resolve their contemporary Russian lives with tools rooted in nineteenth century mythology. They are transforming Cosmism from a forgotten historical episode into a widely held belief of the cultural elite. Their focus on Cosmist theorising is at the expense of formal explorations and new visual languages. They are not challenging the status quo, but perpetuating naíveté, mysticism, and reckless nationalism.

What does the future hold for Russians now living in the third decade of the new millennium? This brief investigation into the occult world of Cosmism instructs us in the day-to-day reality of a culture that cannot yet be characterised by any "posts". Russian culture cries out for Appiah's bold space clearing gesture. Cosmists are my contemporaries. We lived through the same Soviet-era experiences. I respect their creative ambitions, but their cosmic utopias must be understood as a placeholder for a truly secular program of "heaven on earth", and not one set in a distant galaxy peopled by our resurrected ancestors.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor von Veh and Dr Raubenheimer for this opportunity to share my recent explorations in postcolonial and post-socialist concerns within the context of Russia. My deepest thanks to the artists and the editors.

Notes

1 . Posthumanism is a philosophical perspective of how change is enacted in the world. Humanist assumptions concerning the human are infused throughout Western philosophy and reinforce a nature/culture dualism where human culture is distinct from nature.

2 . According to David Rowley (1999:67) 'Millenarianism is a cross-cultural concept grounded in the expectation of a time of supernatural peace and abundance on earth'.

3 . The Narodniks were a politically conscious movement of the Russian intelligentsia in the 1860s and 1870s, some of whom became involved in revolutionary agitation against tsarism.

4 . Decembrists led an unsuccessful uprising on December 14 (December 26, New Style), 1825, and through their martyrdom provided a source of inspiration to succeeding generations of Russian dissidents.

5 . Theosophists followed the religious writing by the Russian immigrant Helena Blavatsky established in the United States during the late nineteenth century. Categorised by scholars of religion as both a new religious movement and as part of the occultist stream of Western esotericism, it draws upon both older European philosophies such as Neoplatonism and Asian religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism.

6 . Bolsheviks are the member of the majority faction of the Russian Social Democratic Party, which was renamed the Communist Party after seizing power in the October Revolution of 1917.

7 . Leninists followed the Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, who proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party, as the political prelude to the establishment of communism.

8 . Futurists attempt to systematically explore predictions and possibilities about the future and how they can emerge from the present, whether that of human society in particular or of life on Earth in general.

9 . Nikolay Fedorov (1829-1903) was a Russian Orthodox Christian philosopher, who was part of the Russian Cosmism movement and a precursor of transhumanism. Fedorov advocated radical life extension, physical immortality and even resurrection of the dead, using scientific methods.

10 . Bruce Mazlish (2011:2), in his 'Ruptures in History', suggests that 'we think of it as a major cut in the continuity of the past. Against the view of the human past as marked by continuity, ruptures mark abrupt change'. The fall of socialism did not result in the opposite regime of democracy. Putin's government continues the rule of the old-past totalitarian government.

11 . Thermidor is the period that follows an extremist stage of a revolution and characterised as a dictatorship by an emphasis on the restoration of order, and some return to patterns of life held to be normal. In his book The revolution betrayed (1935) Leon Trotsky referred to the rise of Stalin and his post-revolutionary repressions as the 'Soviet Thermidor'. The second Thermidor took place in 1989, when according to Alec Rasizade (2008:3), 'Robespierre and Yeltsin were no longer needed. As in post-revolutionary France when General Bonaparte introduced a dictatorial regime of 18th Brumaire (9 November 1799) Vadimir Putin will reinstate "Eighteenth Brumaire" of Vladimir Putin'.

12 . Russophilia is admiration and fondness of Russia (including the era of the Soviet Union and/or the Russian Empire), Russian history and Russian culture.

13 . Cryonics is the low-temperature freezing and storage of human remains, with the speculative hope that resurrection may be possible in the future. KrioRus is the first cryonics company in Russia. It was founded in 2005 by the Russian Transhumanist Movement NGO. KrioRus says hundreds of potential clients from nearly 20 countries have signed up for its after-death service. KrioRus is the world's third-largest cryonics company and the only one outside the United States. The early Russian scientists researched suspension by freezing, exemplified by the epic preservation of Lenin's corpse, the idea of freezing the dead in the hope of reanimating them has been very popular the Soviet Union and Russia. Cryonics is the cornerstone of the immortalists' movement (Cohen 2021:87).

14 . An immortalist is a person who supports the idea that, with the help of science, people need never die. Older immortalists see cryonics as their last chance.

15 . A. L. Chizhevsky, Zemlya v ob'yat'yakh solntsa, "The Earth in the Embrace of the Sun" in Chizhevsky, Kosmicheskiy pul's zhizni (Moskva, 1995)

16 . Alexander Chizhevsky (1897-1964) was a Soviet-era interdisciplinary scientist, a biophysicist who founded "heliobiology" (the study of the sun's effect on biology) and "aero-ionization" (the study of effect of ionization of air on biological entities).

17 . Chizhevsky used historical research (historiometry) techniques to link the 11-year solar cycle, Earth's climate, and the mass activity of peoples.

18 . Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid are Moscow-born artists who emigrated to Israel in 1977 and then to New York in 1978. They collaborated between 1967 and the early 2000s and are founders of Sots Art (socialist art), based on the appropriation and subversion of socialist realist iconography and street propaganda. Their very first Sots Art painting Laika (1972) depicts the famous space dog and employs a modern icon used on the packaging of a popular cigarette brand, turning the latter into a critique of the Soviet Space propaganda, which communicated exaggerated achievements in space science during the Cold War.

19 . Pussy Riot is a Russian feminist protest punk rock group based in Moscow. Founded in August 2011, the group staged unauthorised provocative guerrilla gigs in public places. The group's lyrical themes included feminism, LGBT rights, and opposition to Russian President Vladimir Putin and his policies.

20 . Pyotr Pavlensky is a Russian contemporary artist, known for his controversial political art performances, which he calls 'events of political art' (Eberstadt 2019). His work often involves nudity and self-mutilation. Pavlensky makes the 'mechanics of power' visible, forcing authorities to take part in his events by staging them in areas with heavy police surveillance (Eberstadt 2019).

21 . Black Square is an iconic painting by Kazimir Malevich. The first version was done in 1915. The work is frequently invoked by critics, historians, curators, and artists as the 'zero point of painting', referring to the painting's historical significance and paraphrasing Malevich.

22 . Aleksander Rodchenko was a Russian and Soviet artist, sculptor, photographer, and graphic designer. He was one of the founders of constructivism and Russian design; he was married to the artist Varvara Stepanova.

23 . See his artist statement at https://www.headlands.org/artist/arseny-zhilyaev/

24 . Workers' Club is a work by the Soviet artist, sculptor, and designer Alexander Rodchenko, a founder of constructivism. The artist aimed to create an optimal model space for self-education and cultural leisure activities, including playing chess.

25 . Tenet is a 2020 science fiction action thriller film written and directed by Christopher Nolan. The film follows a secret agent who learns to manipulate the flow of time to prevent an attack from the future that threatens to annihilate the present world.

26 . The total installation genre, created by Ilya Kabakov, allows the viewer to dive into a special atmosphere created by the interaction of images, texts, objects and sounds. Kabakov likens the viewer of a total installation to Dante in his Divine Comedy, while the artist plays the role of Dante's companion, Virgil. Completely caught up in the installation, the viewer inescapably finds himself or herself in another environment in which time seems to stand still.

References

Alexander Chizhevsky: Physical factors of the historical process. 2022. [O]. Available http://theperihelioneffect.com/alexander-chizhevsky-physical-factors-of-the-historical-process/ Accessed 18 February 2022. [ Links ]

Boczkowska, K. 2016. The impact of American and Russian Cosmism on the representation of space exploration in 20th century American and Soviet space art. PhD thesis, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan. [ Links ]

Bolsheviks, Encyclopedia of Marxism. 2019. [O]. Available: https://www.marxists.org/subject/bolsheviks/index.htm Accessed 18 February 2022. [ Links ]

Bradley, J. 2017. Welcome to the club: How Soviet avant-garde architects reimagined labour and leisure [O]. Available: https://www.calvertjournal.com/articles/show/8735/welcome-to-the-club-soviet-avant-garde-architects-labour-leisure-workers Accessed 18 February 2022. [ Links ]

Chioni Moore, D. 2001. Is the post- in postcolonial the post- in post-Soviet? Toward a global postcolonial critique. Globalizing Literary Studies. PMLA 116(1):111-128. [ Links ]

Cohen J. 2021. There is mind all over the body: Immortalist and transhumanist futures. PhD thesis, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario. [ Links ]

Cruz-Uribe, T. 2017. Following the black square: The cosmic, the nostalgic and the transformative in Russian avant-garde museology. MA dissertation, University of Washington, Washington. [ Links ]

Curtis, JAE. 2013. The Englishman from Lebedian: A life of Evgeny Zamiatin. Brighton MA: Academic Studies Press. [ Links ]

Decembrists, Russia Beyond. 2020. [O]. Available: https://www.rbth.com/history/331989-all-about-russian-decemberists-revolt Accessed 18 February 2022 [ Links ]

Etkind, A. 2011. Internal colonization: Russia's imperial experience. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Eberstadt, F. 2019. The Dangerous Art of Pyotr Pavlensky. [O]. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/11/magazine/pyotr-pavlensky-art.html Accessed 28 January 2022. [ Links ]

Fedorov, N. 2015 1906. The Museum, its meaning and mission. Translated by Stephen P. Van Trees. [O]. Available: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/65/336461/the-museum-its-meaning-and-mission/ Accessed 9 March 2021. [ Links ]

Franceschini, S. 2012. Artists at work: Arseniy Zhilyaev [interview]. [O]. Available: https://www.afterall.org/article/artists-at-work-arseny-zhilyaev Accessed 9 March 2021. [ Links ]

Franetovich, A. 2019. Cosmic thoughts: The paradigm of space in Moscow conceptualism.[O]. Available: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/99/263593/cosmic-thoughts-the-paradigm-of-space-in-moscow-conceptualism/ Accessed 13 July 2021. [ Links ]

Gulevich V. 2021. Ukraine: Russophobia plus Russuphilia. [O]. Available: https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2021/05/24/ukraine-russophobia-plus-russophilia/ Accessed 9 March 2022. [ Links ]

Groys, B. 2014. A museum of immortality. [O]. Available: https://www.e-flux.com/program/64925/a-museum-of-immortality/#:~:text=The%20premise%20of%20%E2%80%9CA%20Museum,Fedorov%20(1828%2D1903) Accessed 8 August 2021. [ Links ]

Groys, B. 2015. Russian Cosmism. Moscow: Garage publishing program in collaboration with Ad Marginem Press. [ Links ]

Holbraad, M, Kapferer, B & Sauma J. 2019. Ruptures: Anthropologies of discontinuity in times of turmoil. London: UCL Press. DOI 10.14324/111.9781787356184 [ Links ]

Kabakov, I. 2007. The man who flew into space from his apartment. The Slavic and East European Journal 51(3):634. [ Links ]

Khodarkovsky, M. 2014. Empire of the steppe: Russia's colonial experience on the Eurasian frontier. [O]. Available: https://www.international.ucla.edu/euro/article/139315 Accessed 13 August 2021. [ Links ]

Kishkovsky, S. 2021. Pussy Riot members leave Russia after facing multiple arrests amid crackdown. [O]. Available: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/08/04/pussy-riot-members-leave-russia-after-facing-multiple-arrests-amid-crackdown Accessed 13 August 2022. [ Links ]

Kopenkina, O. 2015. The political poseurs of contemporary Russian art. [O]. Available: https://hyperallergic.com/185275/the-political-poseurs-of-contemporary-russian-art/ Accessed 23 May 2021. [ Links ]

Levchenko, L. 2021. In the studio of Arseny Zhilyaev, interview. [O]. Available: https://theblueprint.ru/culture/art/hudoznik-arsenij-zilaev Accessed 3 September 2021. [ Links ]

Lind, M. 2021. Three observations. [O]. Available: https://sreda.v-a-c.org/en/read-22 Accessed 4 September 2021. [ Links ]

Manaev, G. 2021. How are religion and Russian space science connected? [O]. Available: https://www.rbth.com/history/333830-russian-space-and-religion Accessed 3 September 2021. [ Links ]

Malevich Black Square. 2021. [O]. Available: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/kazimir-malevich-1561/five-ways-look-malevichs-black-square Accessed 3 September 2022. [ Links ]

Mazlish, B. 2011. Ruptures in history. Historically Speaking 12(3):32-33. DOI: 10.1353/hsp.2011.0044 [ Links ]

Narodniks. Encyclopedia of Marxism. 2019. [O]. Available: https://www.marxists.org/glossary/orgs/n/a.htm Accessed 18 February 2022. [ Links ]

Nesbit, M. 2018. Cosmist rays: The rise of Cosmism. [O]. Available: https://www.artforum.com/print/201802/molly-nesbit-on-the-rise-of-Cosmism-73668 Accessed 8 August 2021. [ Links ]

Novikova, V. 2018. Ilya Kabakov/Total Installation. [O]. Available: https://www.xibtmagazine.com/en/2018/01/ilya-kabakov-total-installations/ Accessed 25 March 2021. [ Links ]

Rasizade, A. 2018. Putin's mission in the Russian Thermidor. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 41(1):1-25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2008.01.001 [ Links ]

Plochy, S. 2021 The return of history: The post-Soviet space thirty years after the fall of the USSR. [O]. Available: https://huri.harvard.edu/news/return-history-post-soviet-space-thirty-years-after-fall-ussr, Accessed 2 June 2022. [ Links ]

Rodchenko, AM. 2020. Monoskop. [O]. Available: https://monoskop.org/Alexander_Rodchenko. Accessed 18 February 2022. [ Links ]

Rowley, DG. 1999. Redeemer empire: Russian millenarianism. The American Historical Review 104(5):1582-1602. [ Links ]

Serkova, N. 2018. Learning from machines, seeing with a thousand eyes: On the relevance of Russian Cosmism. [O]. Available: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/89/179971/learning-from-machines-seeing-with-a-thousand-eyes-on-the-relevance-of-russian-Cosmism/ Accessed 23 August 2021. [ Links ]

Simakova, M. 2016. No man's space: On Russian Cosmism. [O]. Available: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/74/59823/no-man-s-space-on-russian-cosmism/ Accessed 14 August 2021. [ Links ]

Smith, E. 2018. Why Cosmism? Why now? Tank Magazine 74:82-90. [ Links ]

Solzhenitsyn, A. 2009. The Solzhenitsyn reader: New and essential writings, 1947-2005. Wilmington: Intercollegiate Studies Institute. [ Links ]

Stites, R. 1991. Revolutionary dreams: Utopian vision and experimental life in the Russian revolution. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Suny, RG. 1997. The empire strikes out: Imperial Russia, "national" identity, and theories of empire, in A state of nations: Empire and nation-making in the age of Lenin and Stalin, edited by G Suny and T Martin. New York: Oxford University Press:23-66. [ Links ]

Tlostanova, M. 2011. The South of the poor North: Caucasus subjectivity and the complex of secondary "Australism". The Global South 5(1):66-84. [ Links ]

Tlostanova, M. 2017. Postcolonialism and postsocialism in fiction and art. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Ventsel, A. 2020. How Kazakstan remembers Gulag. [O]. Available: https://icds.ee/en/how-kazakhstan-remembers-the-gulag/ Accessed 14 August 2021. [ Links ]

Vidokle A & Emmelhainz I. [Sa]. God-building as a work of art: Cosmist aesthetics. [O]. Available: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/110/335963/god-building-as-a-work-of-art-cosmist-aesthetics/ Accessed 6 February 2021. [ Links ]

Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid. 2020. [O]. Available: https://www.theartstory.org/artist/komar-and-melamid/ Accessed 18 February 2022. [ Links ]

Zhilyaev, A. 2016. Factories of resurrection: Interview with Anton Vidokle. [O]. Available: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/71/60539/factories-of-resurrection-interview-with-anton-vidokle/ Accessed 13 June 2021. [ Links ]

Zaytseva, E & Anikina, A (eds). 2017. Cosmic shift: Russian contemporary art writing. London: Zed Books Ltd. [ Links ].