Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a16

ARTICLES

Trauma and the Scottish Gàidhealtachd - Contemporary artistic responses to the Highland Clearances

Alexander Boyd

Northumbria University, Newcastle, United Kingdom. alexander.boyd@northumbria.ac.uk (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5688-9695)

ABSTRACT

The historical event known as "The Highland Clearances" is a term broadly used to describe the forced evictions of Scottish crofters and their families. Whether through dispossession, or through migration due to economic circumstances, the changes undergone between 1750-1860 in the Gàidhealtachd (Gaeldom) have been represented in visual culture by a number of artists, with scholarship largely focused on painters of the Victorian period such as Thomas Faed RSA and John Watson Nicol. This paper seeks to place an emphasis on the efforts made in the last few decades by those in traditional Gàidhealtachd areas to reassess this legacy. As we approach the 40th anniversary of the landmark exhibition and publication As an Fhearann (From the Land), this paper focuses in particular on the work of An Lanntair Arts Centre in Stornoway, and the practice of an artist descended from an evicted family, Will Maclean RSA. The difficult issue of victimhood and the Gàidhealtachd, its relation to post-colonial narratives, and the changing nature of discourse around the Clearances are also discussed.

Keywords: Scottish Art, Highland Clearances, Gàidhealtachd, Scottish Photography, Gaeldom, Post-colonialism.

The Highland Clearances is a term given to the forced eviction of thousands of Scots from their homes and crofts by their landlords, occurring from the mid-eighteenth to the mid-to-late nineteenth centuries. In this paper I discuss responses by contemporary artists within Scotland to the legacy of this historical trauma. In this overview, I contextualise several of these works, as well as addressing questions which have arisen from their display, and subsequent reception. I focus on visual artists primarily working in the field of painting, photography and sculpture, concentrating on artists such as Will Maclean RSA and Reinhard Behrens, whose work responded to themes established by nineteenth century artists such as Thomas Faed RSA and James Watson Nicol.

For the purposes of this paper, I have provided a brief definition of what is meant when referring to the Scottish Gàidhealtachd (Gaeldom). While a comprehensive history of the Highland Clearances and of Scottish Art over the last two centuries is outside the scope of this work, these subjects will be discussed in relation to the artworks presented. The crucial contribution of Highland art centres such as An Lanntair on the Isle of Lewis, and Timespan in Helmsdale in Sutherland to current discourse is also discussed.

The Scottish Clearances and the Gàidhealtachd

The location of the Gàidhealtachd can be roughly ascribed to the north-west of Scotland, encompassing the heartlands of the Gaelic-speaking world such as the Outer Hebrides, Skye and vast swathes of the Highlands, including Sutherland and Assynt. A description of the Gàidhealtachd as limited to Gaelic speakers in the "Highlands and Islands" is erroneous, however, as large parts of this region are populated by English and Scots speakers, most notably in the eastern Highland area. Conversely, many communities of Gaelic speakers can be found in the lowland region of Scotland, such as Glasgow or the inner Hebridean islands.1 The long history of Gaelic and the Gàidhealtachd is of course tied to the fortunes of its speakers, and no historical event has left a mark such as that of the Highland Clearances.

The events which we describe today as the Highland Clearances took place over an extended period, although are generally agreed to have occurred between the years 1750 to 1860. Throughout Europe, the widespread displacement of rural populations was a common occurrence prior to this period, however what came to be known as The Clearances was defined by behaviour described by Gaelic poet Derek Thomson as '...sweeping and brutal because the Highland landlord possessed powers more unrestricted than those of any other in Europe' (cited by Maclean 1986:5). This power was exerted during a time of great social change in Scotland, driven by the intellectual ideas produced by leading thinkers of The Scottish Enlightenment.

A phenomenon of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, The Enlightenment saw the advancement of empiricism, philosophical thought, scientific progress, and the pursuit of improvements to society as a whole through a multitude of innovations - from education to the economy, most notably in the writings of Adam Smith. This would have dire, and unforeseen consequences for those living in Scotland's rural Highland communities. Enlightenment thought was applied to the Highland agricultural areas and their often poor, overcrowded and struggling populace; it was therefore unsurprising that the term used by those who would implement these reforms was "Improvements". Vast areas of the Highlands were owned by a small number of powerful landowners, most prominent of these the Dukes of Argyll, Sutherland, Atholl and Buccleuch. These men began to see attractive economic incentives in reorganising their lands to yield higher profits.

Prior to The Enlightenment, a series of agricultural reforms had already begun to take place across Scotland, predominantly in the Lowlands from the seventeenth century onwards. Older less productive forms of farming (such as runrigs) were replaced and re-organised into land used for free pasture, with the introduction of crop rotation and new methods of sowing. This led inevitably to the displacement of people in what is now largely referred to as the "Lowland Clearances". In many cases the displaced populations relocated to urban centres, which is one reason why these events have not gained the notoriety of what would take place in the Gàidhealtachd. Tom Devine (2018:128) in his book The Scottish Clearances observes that, unlike the experience in Gaeldom, culturally there is a complete absence of material related to the Lowland Clearances '...no oral tradition, folk memory of dispossession, poetry of tragedy or words of lament surround the lowland experience of land loss'.

Several reasons have been posited for this absence, however the language and cultural similarities of Lowland Scots, who were largely anglophone speakers, were more easily assimilated than that of Gaelic speakers who were increasingly viewed as part of a 'Celtic Fringe', which often took on a racial dimension within the British Isles itself (Stroh 2007:181). The othering of Gaelic speakers was exacerbated by a series of well-known uprisings in 1719 and 1745 which, with the defeat of the Jacobite cause at the Battle of Culloden, presaged the decline of Gaelic culture in Scotland.2

Following Culloden, the subjugation, pacification and integration of the Highlands became a priority for the British state. This would be achieved through the construction of a new network of military roads across the North directed by General Wade, and a vast new fortress - Fort George near Inverness. Alongside militaristic interventions, the traditional symbols of the clans - such as pipes and the wearing of tartans - would be banned (in the Dress Act of 1746), itself part of the Act of Proscription (1746) which forbade the carrying of weapons. The final blow would be delivered by the Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act (1746) designed to crush the influence of the clan system by removing the feudal powers of clan chieftains.3With the traditional customs of Gaeldom now seemingly irreparably damaged, the old system could be swept away entirely. Clansmen and women now found themselves no longer protected by their chiefs, many of whom sold off the land they lived upon. In other cases, they instituted changes which would see the inhabitants treated as squatters in the very places their families had inhabited for generations.

The Fuadaichean nan Gàidheal (the eviction of the Gaels) now began in earnest, with eviction parties forcibly removing people from their homes. Many would end up in Scotland's industrial south or forced into small barely inhabitable coastal communities. Faced with a way of life that was unsustainable, or forced out at the behest of their landlords, many had no choice but to leave Scotland for good. While exact numbers of those forced to leave their homes is difficult to establish, they are thought to number in the many tens of thousands, or higher.

The Gàidhealtachd, The Clearances and the problems of Scottish victimhood

Are we, colonised and colonising, going to continue to look for fantasies of ourselves in other subalterns and other imperialists, or can we develop a language for a politics of our own? (Giles 2018:1).

In her question posed in the aftermath of the 2014 Scottish Independence Vote, Harry Josephine Giles draws attention to the most problematic aspect of Scottish post-colonial discourse - that Scotland cannot simply adopt narratives which apply to other nations that have undergone a process of colonisation. Debate around the Clearances, and in particular the victimhood of Gaels, is a complex and unresolved issue. Scotland is a country which can present evidence of a marginalised and abused subaltern class, while simultaneously being a willing participant and beneficiary of imperialism as part of the United Kingdom.4 There has also been a tendency in the preceding decades to present the Clearances as part of an anti-British, or at its most crude level, an anti-English narrative, one in which historic events have been described as a form of ethnic-cleansing, or in their most extreme examples, compared to that of the holocaust. As Tom Devine (2018:41) observes: 'Nationalism, clearances and victimhood soon became intimately linked by some polemicists, a tendency which has continued to the present day through the proliferation of social media'.

Accusations of a British, or more specifically English "cultural colonisation", perhaps best known from an expletive laden diatribe in the 1996 film Trainspotting, are also a feature of public discourse. In 2017, protests took place outside of the National Museum of Scotland (NMS) by the Gaelic advocacy group Misneachd (Scotsman 2017:1). Misneachd accused NMS of failing to use Gaelic in their presentation of historical events related to the history of the Gàidhealtachd. In a statement, they accused NMS of a '...cultural appropriation and English language colonisation of our history...Gaelic, and the Gaelic peoples of the Highlands as a minority population' (Scotsman 2017:1). The National Museum responded that such criticisms were unfounded.

The Scottish National Portrait Gallery (SNPG) also received negative publicity in 2019 when their exhibition The Remaking Of Scotland - Nation, Migration, Globalisation 1760-1860 appeared to minimise Clearance related narratives (Hannan 2019:1). This important exhibition would, however, address the darker side of Scotland's contribution on the global stage, in particular its role in profiting from the international slave trade. This included a series of contemporary images of locations in Jamaica, where Scots exploited the local population, made by photographer Stephen McLaren, in the series A Sweet Forgetting: Slavery, Sugar and Scotland. These Scots were thriving in Jamaican towns with Highland names such as Inverness and Culloden (Shakur 2015:1), making explicit the links between the Gàidhealtachd and the slave trade.

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, Scotland is undergoing a gradual reckoning with its past. Scottish Government minister Patrick Harvie recently raised a Parliamentary Motion to suggest opening a new museum dedicated to Scotland's role as part of the British empire (Styles 2020:1). This proposed new museum would aim to confront the difficult legacy of Scotland's role as part of a colonial power. The proposal raised questions, however, as to why it was felt that the National Museum of Scotland had not adequately addressed the issue. In Edinburgh, a prominent statue of Henry Dundas, Lord Melville (1742-1811), who was accused of delaying the abolition of the slave trade, is currently the subject of intense debate. A new plaque was installed by the city council in March 2021 'dedicated to the memory of the more than half a million Africans whose enslavement was a consequence of Henry Dundas's actions' (Forbes 2021:1).

In the Scottish Highlands the iconic Glenfinnan Monument, built to commemorate the place where Bonnie Prince Charlie would raise his standard, has also come under scrutiny, alongside many other National Trust for Scotland properties. Marking an event which would lead to the disaster at Culloden, the monument is regarded as an important emblem of Gàidhealtachd resistance to the British State. In 2021 Canadian researcher Karly Kehoe uncovered the links between the monument's financier Alexander Macdonald, The Laird of Glenaladale, and the sale of the Jamaican coffee plantations which accounted for much of his wealth (Campsie 2021a). So too were links found between one of the earliest Gaelic dictionaries printed by the Highland Society of Scotland in 1828, with much of the money raised through slavery (Campsie 2021b). A recent publication by David Alston, Slaves and Highlanders: Silenced histories of Scotland and the Caribbean (2021) traces the many links between the Highlands and colonial exploitation.

In the museum and gallery sector, the debate is furthered in the Scottish Highlands by organisations such as Timespan in Helmsdale, site of one of the most notorious acts of Clearance. With their exhibition: No Colour Bar: Highland Remix: Clearances to Colonialism in 2019, they directly addressed the perceived whitewashing of Scottish involvement in the running of the Empire. Like the SNPG exhibition which preceded it, the much-needed voice of other victims of clearance, those directly oppressed by Scots, could finally be heard in the Highlands themselves. In a press release for the exhibition, Timespan noted:

Scotland suffers from colonial amnesia, which has allowed its popular history to be mythologised as one of subjugation to England. This whitewashing of its imperialist past deliberately neglects Scotland's heavy involvement in the Caribbean and its role in managing and running the Empire (Hassan 2019:1).

Timespan's statement echoes Harry Josephine Giles' observations on Scotland's troubling relationship with its past, and provides new perspectives on art which are currently being made about the Clearances in Scotland. The work of two contemporary photographers working in Scotland, Frank McElhinney and Tajik Iman, can be viewed in this wider context.

Frank McElhinney and Adrift (2016)

The photographer Frank McElhinney, whose work often explores Scottish historical subjects addressed The Clearances in his 2016 series Adrift. Exhibited at Streetlevel Gallery in Glasgow and comprised of some 30 aerial shorts of the ruins of Clearance sites across Scotland, the work was a direct reaction to the ongoing crisis of deaths of migrants crossing The Mediterranean. Scottish Independence is a pre-occupation of the photographer, whose other works include a series on the Battle of Bannockburn, and two solargraph projects directly relating to the subject 45 Sun Pictures in Scotland and Only for Freedom, described by the artist as 'a declaration of independence written by light' (McElhinney [Sa]:1). Another series focuses on the legacy of Ravenscraig Steelworks, whose closure by the British government devastated his native Lanarkshire.

Adrift however widens the narrative from Scotland to further afield, drawing attention to the ongoing humanitarian disaster in the Mediterranean. This is achieved through juxtaposing images of clearance sites with the addition of a work on paper titled Mediterranean Incident Co-ordinates, comprised of hundreds of hand-drawn latitude and longitude positions. John Farrell (2016:1), in a review of the show for the Scottish Society for the History of Photography, writes that 'McElhinney deftly draws parallels between the on-going situation and Scotland's own forced migratory history'. In his appraisal of the exhibition, however, Farrell fails to acknowledge that in making this juxtaposition, McElhinney fails to address several uncomfortable issues.

While it is hard to ascertain exact statistics for those lost in the Mediterranean, numbers recorded in 2016 by the United Nation's International Organisation for Migration, revealed that of those migrants crossing the sea to Greece, the majority came from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, all countries who have recently seen military intervention from British ground and air forces (UN IOM:1). Recent wars in Libya, and the long legacy of European colonisation of the African Continent, which Scotland had been involved in since the Act of Union in 1707, have also directly or indirectly led to many of the migrations occurring today. Instead of addressing this, Adrift inconveniently side-steps the role of Scots within these destabilising events, and in so doing downplays the wider imbalances of national power dynamics, Scots role in sowing the seeds of racial ethnic tensions, and the historical abuses committed by those cleared to the colonies. It creates a problematic false equivalence that undermines the well-meaning intention of the work.

Interviewed about the series on the Document Scotland website, McElhinney commented that he 'was inspired by the early work of Tom Devine who described how the Highland Clearances were underpinned by ethnic inferiorisation (sic) of the Gaels and resulted in an almost complete cultural erasure' (Document Scotland 2016:1). While presumably drawing comparison with the well-documented demon-isation of migrants by the British media, in making this comparison between contemporary events and the Clearances, McElhinney exemplifies Devine's criticism of those who conflate the issues of nationalism, clearance and victimhood.

Iman Tajik and The Dreamers (2019)

In the Arts Magazine Art North, writer Ian McKay reviewed the series The Dreamers by Iranian artist and activist Iman Tajik, based in Glasgow. Exhibited as part of 'Projects 20' at Stills Gallery, The Dreamers featured a series of images of the artist, himself a former refugee, standing in the Aberdeenshire landscape, wrapped in an emergency safety blanket similar to those issued to migrants.

With an abandoned nineteenth century farmstead behind him, these works are intended to draw obvious parallels between past and present, as had McElhinney with his series Adrift. While McElhinney had presented actual sites of clearance, Tajik instead chose a site, the Cabrach, with no relationship to this difficult past, whose own history of depopulation was largely economic in nature, with a significant migration to the British colony of Jamaica. A place where the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge observed that 'Of the overseers of the slave plantations in the West Indies, three out of four are Scotsmen and the fourth is generally observed to have very suspicious cheekbones' (Kay 2011:207). The artist instead uses the Cabrach as a 'stand in location' for events which have occurred elsewhere, telling McKay (2021:8) that the location was chosen for its potential 'to look like the Highlands'. This negates the lived experiences of the people of this area, one in which the North-East of Scotland is reframed as a victim of clearance. Ian McKay (2021:9) concludes that

Under (the) cover of contemporary arts practice, this history is lost according to Tajik's political agenda...Tajik may have insights into the refuge crisis, but his misuse of Scottish history.. .is, to me, reprehensible.

While both photographers attempted to ground contemporary migratory events through juxtaposing them against Clearance narratives, they unintentionally undermine the activism which drives their work, as well as furthering misconceptions about Scottish history. The question then remains - how should artists respond to the Clearances? Can it be done in such a way that it acknowledges the complexity of the events without furthering political and nationalistic agendas? Perhaps this is best answered by those most directly affected, the descendants of those who were cleared.

The Scottish Gàidhealtachd and visual art

In Gaelic culture, the concept of 'writing back' to Empire, a way of challenging established colonial narratives, is prominent in literature as well as in music (Stroh 2007:188). In the post-Clearance era, as Scotland grapples with its past, Gaelic speakers have attempted to re-appropriate the discourse in what Donnie Munro describes as the move towards the 'revitalisation and regeneration of the Gaelic language and culture' (Macdonald 2013:6).

The Scottish Gaelic Renaissance (Ath-Bheòthachadh na Gaidhlig) rose to prominence in the mid twentieth century. The Renaissance has been driven by the writings of islanders such as Sorley Maclean, Iain Crichton Smith and Derick Thomson as well as George Campbell Hay (who was raised in Argyll and wrote under the patronymic Deòrsa Mac Iain Dheòrsa) (Macdonald 2011:1). Contemporary writers continue to further the aims of the Renaissance through the promotion of Gaelic, especially through centres such as Sabhal Mor Ostaig, part of the University of the Highlands and Islands on the Isle of Skye.

The work of local history societies such as the Comunn Eachdraidh, museums, and other research groups across the Highlands have long been instrumental in telling the stories of the Clearances and land struggles, often working together with art galleries. Nowhere is this more notable than the work carried out by An Lanntair (The Lantern) Arts Centre in Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis. Opened by poet and writer Iain Crichton Smith in 1985, An Lanntair's contribution to contemporary discourse about the Clearances through the exhibition As an Fhearann (From the Land), and its subsequent publication of the same name, is a significant one. Commemorating the centenary of the Crofting Act 1886, which effectively halted the Clearances, their overview of the visual response and its subsequent legacy, brought much of this work together for the first time in an exhibition which toured across Scotland throughout 1986 and 1987. As an Fhearann featured the work of painters, photographers and sculptors, and attempted to fill the visual vacuum left by Scottish artists who had in the preceding decades largely ignored the Clearances.

In the visual arts the Clearances are best known to wider audience through two celebrated artworks by nineteenth century artists, the Last of the Clan by Thomas Faed in 1865, and Lochaber no More by John Martin Nicol in 1883. Both paintings depict scenes of departure from the Scottish coast and were painted with the consumption of London audiences in mind. The works of both Faed and Nicol, both lowland Scots, are those of outside observers of life in the Gàidhealtachd and are heavily romanticised in nature.5 An artist more intimately acquainted with the great changes in Gaeldom is William McTaggart (1835-1910), a West Highlander who stands today as one of the most celebrated of Scottish landscape painters.

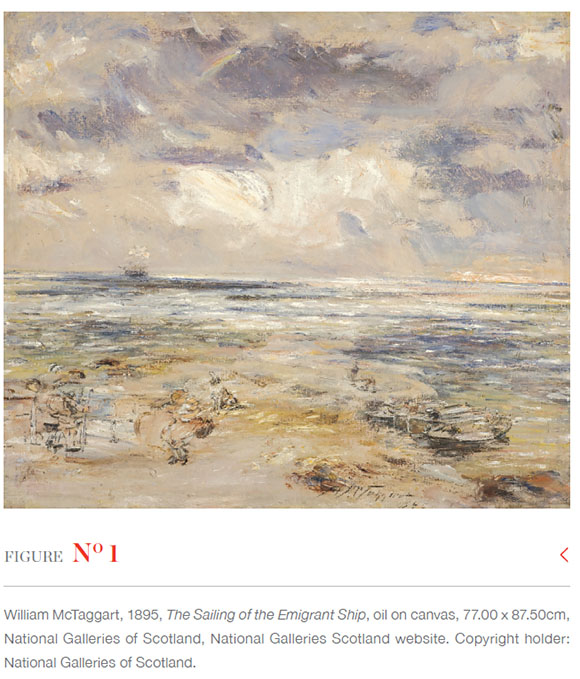

McTaggart's works of the 1880s are a departure from the meticulous academic style of Faed and Nicol, and reflect the influence of Impressionism, contrasting with the Pre-Raphaelite approach of his earlier works, many of which depicted children. Painted en plein air, the works of the 1880s capture the light and mood of the scenes before him, and are easily recognisable due to their painterliness and move away from fine detail. It is his 1883-1889 work Emigrants Leaving the Hebrides, and the series of contemporaneous related paintings including The Sailing of the Emigrant Ship (1895) (Figure 1), which were his most powerful evocation of the plights of those leaving home, presumably for better lives. These are works stripped of sentimentality, in which small figures are lost against endless landscapes, their predicament measured against the vastness of the sea, the open elements, and the journey ahead.

McTaggart, described as 'the "father" of the modern Scottish movement' (Macdonald 2013:6), was himself the son of a Gaelic-speaking crofter in the Kintyre peninsula, and was raised on the western Atlantic seaboard of Scotland (National Galleries of Scotland 2021:2). He would experience the effects of emigration on his family firsthand, with his sister Barbara and her husband leaving for Canada, presumably alongside many others he had known from his youth. In his series of works made in response to the Clearances, it is likely he was, like Faed and Nicols, inspired by the establishment of the Napier Commission and the publication of History of the Highland Clearances by Alexander Mackenzie in 1883.

In his "Emigrant" series of works from this decade, McTaggart presents the viewer with large, open seascapes, each with a ship bound for the Americas out at sea. Our attention is drawn to the shoreline in both images. In The Emigrants we observe women and children embarking small boats which are presumably preparing to ferry them to the vessels beyond. Boxes and possessions are loaded on board in an image vibrant and full of life. Beyond a distant rain cloud skirts the horizon, the eventual fate of the emigres remaining unclear. In The Sailing of the Emigrant Ship of 1895, however, we are likely observing the aftermath of departure. Few figures remain, and the launches which had been made ready now lie tied up and empty. This later work is much looser than the first, and more sombre in its palette. There is a palpable sense of loss, as well as a sense of ambiguity as the emigrant ship heads into a storm. Part of a rainbow, however, can be seen in the heavens above the vessel. One critic writing on the work in 1899 observed: 'It is the epic of depopulation, emigration and of quests in foreign lands. It tells of laments abroad for "my ain countrie", and of breaking hearts at home' (Worthing 2006:202). McTaggart's treatment of Clearance subjects is powerful due to its quiet and presumably faithful depiction of what would have been a familiar scene. It does not explicitly play on the emotions of the viewer like that of his contemporaries. His is a more considered approach which resonates due to eschewing the visual language of Victorian genre-painting and its inherent sentimentality.

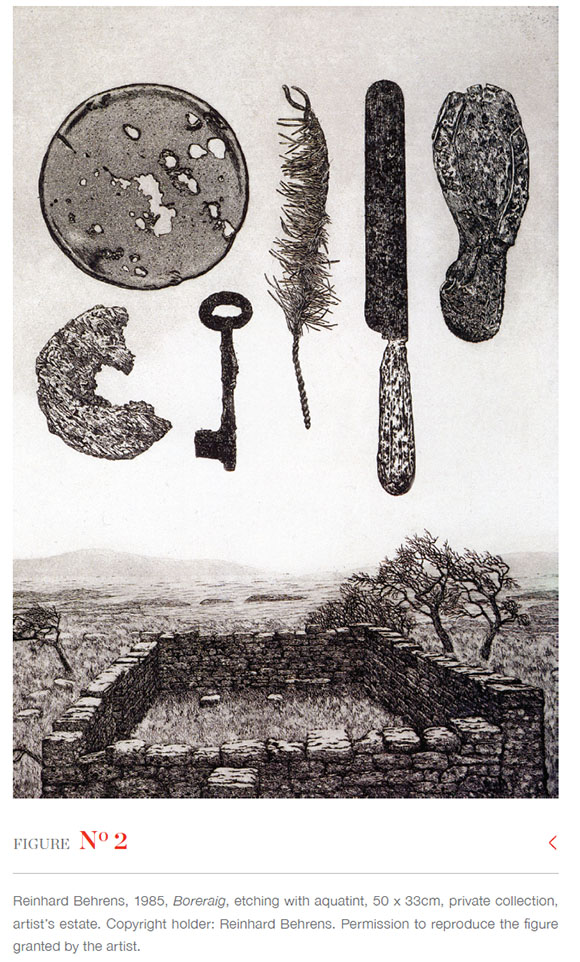

While the As an Fhearann 1986/1987 exhibition included reproductions of nineteenth century artists' work such as that of McTaggart, it mainly focused on the practice of contemporary artists. Many of these artists attempted to create artworks which, like McTaggart before them, confronted viewers with the realities of the Clearances. The clearance of the Skye village of Boreraig forms the basis of an etching and aquatint by German artist Reinhard Behrens, who has spent the majority of his life working in Scotland. Titled Boreraig (Figure 2), the work was produced for the touring exhibition, and depicts an abandoned dwelling from the village. Hovering in the air above the ruins is the rusted evidence of those who once inhabited this home; a key, the remains of utensils, the sole of a shoe. Their depiction is similar to that found in archaeological catalogues, perhaps unsurprising given that Behrens was a draughtsman on excavations in Turkey in the mid 1970s. Echoing eighteenth and nineteenth century etchings of Scotland, the image observes the scene while asking us to review its evidence of past lives. Its visual language is deliberately in-keeping with the Antiquarian journals and publications which would have so interested those who drove the Clearances, men of culture and high societal standing. It could therefore be read as a work which aims to subvert the familiar imagery of ruined and abandoned crofts through the incorporation of printmaking techniques of the period, a theme which we will explore in more detail in the work of Will Maclean.

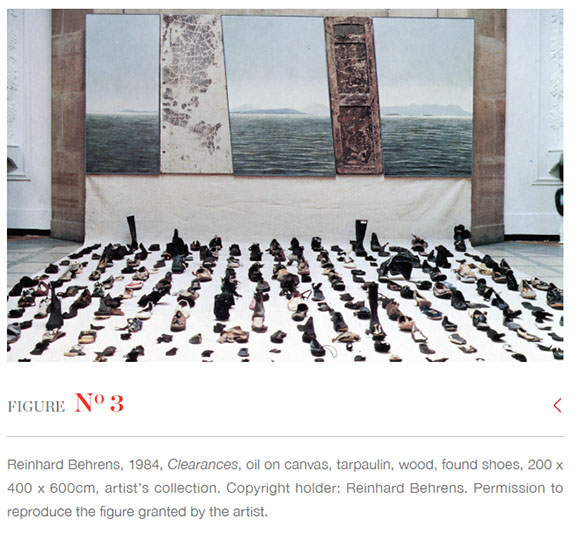

A second large scale piece, titled Clearances (Figure 3) was also presented as part of the touring exhibition. A mixed media work painted in 1984, Clearances consists of a triptych of the Scottish coastline, presumably seen from a ship departing the mainland for destinations unknown. The landscape is, however, placed beyond the reach of the viewer, visible behind a sea of shoes and boots collected from locations across Scotland. Laid out in rows, the footwear, much like the objects of Boreraig, brings to mind archaeological remains, the evidence of lives interrupted.

In an interview in 2021 about this work and its intentions, Behrens remarked that his knowledge of historical events was derived from spending time in the home of Ishbel Maclean. The daughter of poet Sorley Maclean, Ishbel had told Behrens about the clearance of Raasay, her father's native home, immortalised today in his iconic poem Hallaig. Clearances does not however derive its objects from the sites of eviction, with the majority of shoes in the work found on the coastline near the artist's Edinburgh home. He commented:

The fact that those shoes were not found in the genuine location, not being scientific, archaeological finds, to my mind gives them more poetical and general impact.6

The ambiguous origin of the objects in Clearances would have been apparent to viewers on closer inspection. The assemblage included many objects which would be completely unknown to past inhabitants in the Gàidhealtachd - such as flipflops, trainers, and a ski boot. The overall effect of the work, however, is somewhat unsettling, and brings to mind other associations, such as the belongings of victims of genocide. This view was shared by curator Roddy Murray, who helped organise the exhibition at An Lanntair, remarking that Clearances was;

...devoid of whimsy. Comprised of ordered lines of shoes gleaned from the beaches, it had evocations of a quiet holocaust. An archive of lost lives set against the West Highland coastline (Behrens 2000:18).

An Lanntair would follow the success of As an Fhearann with subsequent important exhibitions on art and the Gàidhealtachd, such as Togail Tir / Marking Time: The Map of the Western Isles (1989), and Calanais in 1995, which drew an international response to what is arguably the Gàidhealtachd's most well-known archaeological site. In 1998 the gallery was also responsible for drawing attention to the most visible artwork related to the Clearances, that of the statue of the Duke of Sutherland.

The Duke of Sutherland

Standing on the summit of Ben Bhraggie, the monument to George Leveson Gower, Duke of Sutherland, is known by locals as "The Mannie". The epithet, which may sound like a term of endearment, does not reflect the problematic position which the statue has come to inhabit both physically, and within the Scottish national psyche. It was erected in 1838 and, like the statue of Henry Dundas in Edinburgh, it was designed by Sir Francis Chantry RA. The summer of 1819 is regarded as one of the most infamous in the history of the Clearances, and is known as 'bliadhna na losgaidh (the year of the burnings) or alternatively 'The Devastation of Sutherland' (Hunter 2015:128). Prosecuted by men working on behalf of the Duke of Sutherland, it is estimated some 429 families were evicted from their homes, many having their roof timbers set alight to prevent re-occupation of the properties.

In an appendix titled 'The Highland Clearances as holocaust: Excerpts from popular histories, 1974-2000' Tom Devine (2018:766) highlights several well-known texts which have drawn comparisons between the actions of those who cleared the Highlands, and the genocidal actions of the Third Reich during the Holocaust. Comments made by Winnie Ewing, a long serving and prominent Scottish Nationalist (SNP) politician in 1995 reflect Devine's concerns. Attending a debate in Golspie, a village which sits directly beneath the statue of The Duke of Sutherland, Ewing compared it to 'having a statue of Hitler outside Auschwitz' (Clark 2020:1). Reflecting much contemporary sentiment around the statue of the Duke, journalist Neil Ascherson commented:

I would blow him up, not just as a statement about the Clearances but as a gesture about 'Heritage', for the Duke's removal is a reminder that Heritage, after all, is not just a dry schedule of monuments. It is a ceaseless rolling judgement by a people on its past (Ascheron 1994:1).

There are few monuments in the United Kingdom which have sustained as much systematic abuse as that of the Duke of Sutherland's monument, which has endured multiple attempts to destroy it, something which has noticeably increased with the widening public awareness of the Highland Clearances since the 1960s. This has included the removal of elements of the base to aid in the deterioration and eventual collapse of the work, cutting the lightning rod, and covering the base with graffiti. The public debate which has taken place in numerous national newspaper articles around the statue has put forward two suggested solutions. The first is the destruction and removal of the monument entirely, the second, which has been inadvertently achieved through the relative status quo, is to keep the monument as a memorial to the victims of Clearance, rather than as a memorial to Sutherland himself.7

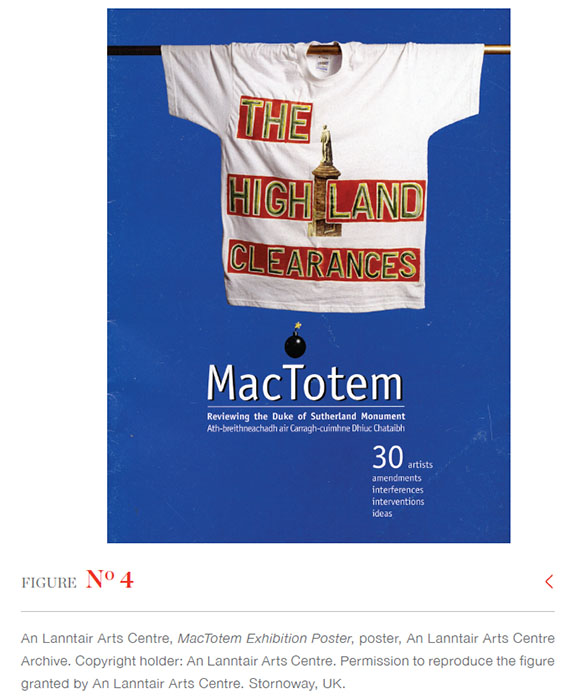

Addressing the concerns of the public, the exhibition MacTotem - Reviewing the Duke of Sutherland Monument (Ath-breithneachadh air Carragh-cuimhne Dhiuc Chataibh) brought together some 30 artists, inviting them, in the exhibition call out, to make 'amendments, interferences and interventions' and to present new ideas related to the controversial statue (Maclean & Murray 1998:5). Displayed at An Lanntair Arts Centre in Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis and supported by Proiseact nan Ealan (PNE - The Gaelic Arts Agency), the 1998 exhibition provided a number of imaginative responses to the monument. Its memorable poster featured the work of Ross Sinclair alongside that of a bomb (Figure 4).

Sculptor Steve Dilworth proposed relocating the statue to Australia, a journey many cleared Scots would have had to make, an approach similarly adopted by artist Angus MacDonald who wished to abandon the statue on a lonely Canadian shore. Photographer Wendy McMurdo suggested the monument be left to fall into disrepair, while Neil Macpherson suggested building a cage around the Duke as a punishment. Sculptor George Wylie suggested one minor alteration to the work, the addition of a small packed suitcase in his left hand - signalling that it was clearly time for the Duke to leave (Maclean & Murray 1998:16).

In a 2021 interview, An Lanntair curator Roddy Murray reflected on the exhibition, noting that, in the wake of the Black Lives matter movement, which had recently brought down the statues of slavers such as Edward Colston in Bristol, the monument to 'one of the chief architects and prosecutors of the Clearances' (Murray 2021:1) still remained above Ben Bhraigge, paid for by 'enforced subscription by the tenants who remained' (Murray 2021:1).

Murray revealed that the inspiration for the exhibition came from observing the work of the artistic team of Christo and Jeanne-Claude who in 1995 had wrapped the Reichstag in Berlin. In a symbolic act of rebirth of a building with a difficult past, the duo created considerable discussion and spectacle around the structure, something which An Lanntair wished to replicate with the Duke. Unfortunately given the polarising nature of the debate around the statue, to date none of the suggestions made by the MacTotem artists have been realised. Its answer can perhaps be found in nearby Helmsdale, with Emigrants, a statue by Gerald Laing unveiled in 2007. A bronze of a mother, father and their two children, the group are depicted as leaving Sutherland behind for the last time, with an uncertain future ahead. Unveiled by the First Minister, it marked an acknowledgment of the Clearances at the highest levels of Government, and an attempt to confront the difficult legacy of the area.

Scottish artist Anthony Schrag, like the artists who preceded him in the MacTotem exhibition, similarly took aim at the statue of the Duke of Sutherland in 2014 as part of his video work Wrestling with History (Schrag 2021:1). In this humorous approach to a difficult subject matter, Schrag's title provides an accurate description of the piece itself. Over the course of two minutes the camera observes the statue from a distance, interrupted only by the presence of the artist, who then proceeds to physically assault the sandstone base of the statue to no avail. The camera cuts to a close up of the impassive face of the Duke, and then back to the dejected and exhausted assailant who then disappears off screen, seemingly defeated by the immutable statue. In his description of the work, Schrag remarks that in the case of the Duke of Sutherland, 'History won' (Schrag 2021:1). The artist continued in a similar vein in a follow up work in which he humorously gave a lecture to a field of sheep in Sutherland, explaining their ancestor's role in the Highland Clearances (Schrag 2021:2).

Malcolm Maclean, the Lewis-based curator and organiser of As an Fhearann was also responsible for the management of a second, and perhaps more far-reaching project with PNE. In 2002, the landmark project An Leabhar Mòr (The Great Book of Gaelic) brought together the work of 100 leading Irish and Scottish contemporary artists alongside that of Gaelic poets. This formed the basis of a book publication and a successful international exhibition which toured for a decade. The Clearances feature in the work of a number of artists, such as Donald Urquhart who, like Behrens before him, responded to Sorley Maclean's poem Hallaig, or in the work of Norman Shaw who responded to the emigration poetry of John Maclean (17871848), or Noel Sheridan whose work illustrates Donald Smith's (1786-1862) lament Sixty Three Years. The publication, like the MacTotem exhibition before it, also featured the work of Will Maclean, who is perhaps the most important living artist making work responding to the Clearances.

The Clearance work of Will Maclean, RSA

Born in Inverness in the Highlands in 1941, Maclean, like McTaggart before him, has a direct connection to the Clearances, with his paternal family having been cleared from Coigach in Wester Ross. Having attended Gray's School of Art in Aberdeen, Maclean has built a career from a practice utilising painting, drawing, printmaking, assemblage and sculpture to investigate the many complex aspects and legacies of the Scottish experience. In his mid-twenties Maclean had begun to explore the Clearances as a subject for his paintings, and while these works no longer survive, the preparatory drawings and studies from 1964 are still extant (Macmillan 2002:10). In 1973, in the work Beach Allegory he created a painting which marked the emptying of the village of Boreraig on the Isle of Skye, a lone fire burning before the ruins of the village beyond. It was followed in 1974 with the stark assemblage Memorial for a Clearance Village.

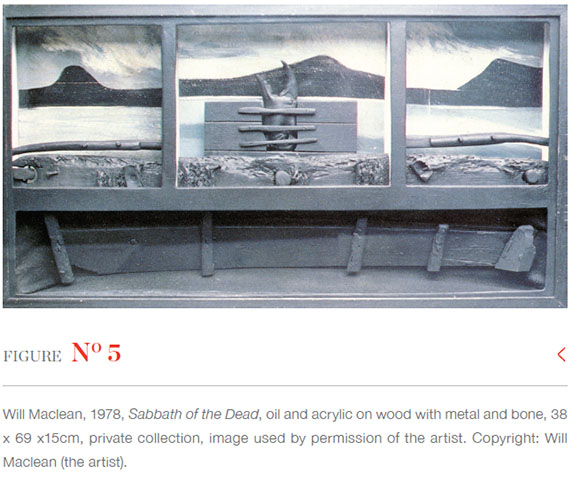

The act of memorialisation is a theme which continues in Maclean's work in the following decades, with the mixed media piece Sabbath of the Dead of 1978 (Figure 5), a direct response to Sorley Maclean's Hallaig. This assemblage combines a triptych painting of the silhouette of the island of Raasay, alongside a fragment of a boat's plank, and a crab's claw which grasps skyward. It is an act which critic Duncan Macmillan has described as 'suggesting a powerful presence in the landscape...expressing both anguish and anger' (Macmillan 2002:41). In its depiction of a landscape submerged in darkness, and its incorporation of both worked and natural objects, Sabbath of the Dead closely mirrors the concerns of the poem. Sorley Maclean invokes the memory of the cleared village by describing its inhabitants as present in today's landscape 'The Dead have been seen alive' (Macmillan 2002:39). The poet achieves this through using arboreal imagery to compare those lost to the rowans, birches and hazels which can be found in Hallaig's ruins today.

Correspondingly Will Maclean utilises wooden objects to confront the viewer with the lives of the villagers. Sorley Maclean mentions 'a board nailed across the window / I looked through to see the west' which finds its physical manifestation in the centre of the assemblage, to which the crab's claw is pinned (Macmillan 2002:39). In this dialogue with the poem, Will Maclean utilises a natural object to create an uncomfortable and ambiguous tension in the centre of the piece, one which could be read as a gesture of both struggle and of defiance. The incorporation of the claw could also be viewed as the outstretched hand of a drowning man, disappearing beneath the waves as the sun sets behind the peak of Dùn Caan. The incorporation of the boat's plank, which spans the work, fulfils a similar purpose to that of the boarded window. A remnant of lives which would have been deeply connected with the sea, the plank becomes a symbolic artefact, similar to the illustrations of archaeological remains in Behren's work Boreraig.

Maclean's works in the 1980s explored the British military presence in the Gàidhealtachd, some explicitly referencing the waters of Raasay, now the training grounds of nuclear submarines. This is most overtly referenced in works such as Death Fish of 1983 with its dark outlines of undersea warships, or Hebridean Cruise of 1985, which incorporates spent munitions into the work. In 1991, the Clearances and their aftermath would feature in the work A Night of Islands, a series of ten etchings showing abstracted scenes from Highland life with evocative names such as The Loss of Gaelic, and Strathnaver, referring to the Duke of Sutherland's infamous eviction of that area.

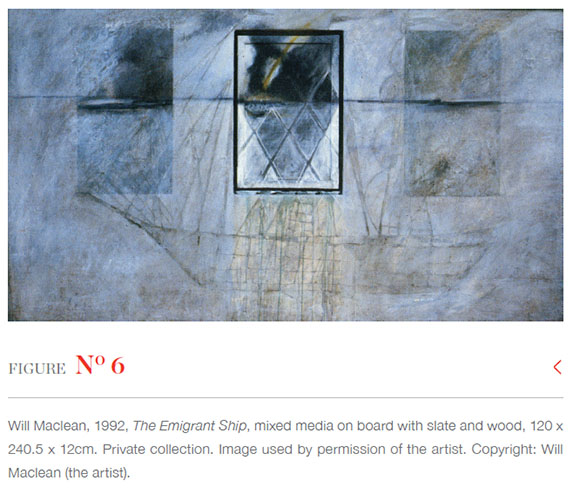

The work of McTaggart, and in particular his Emigrant series of paintings, is explicitly referenced in Maclean's 1992 work The Emigrant Ship (Figure 6), a work which gives voice to the long dead witnesses and participants of events. The familiar form of a fully rigged sailing vessel fills most of the work, a reproduction of a children's drawing from the walls of a long-abandoned school on the Isle of Mull, contemporaneous with the period of clearance. In the centre of the work is the similarly spectral outlines of the church windows at Glencalvie, whose glass still bear the scrawled marks of those forcibly removed from their homes. It is a work of great pathos, and one of several in which Maclean brings together and explores the established iconography of the Clearances. Like Sabbath of the Dead before it, this work incorporates objects, such as schoolroom slates, to memorialise the departed by providing symbolic evidence of their lives. It is a work which also plays with the recognisable imagery of The Clearances, a theme which Maclean would often return to.

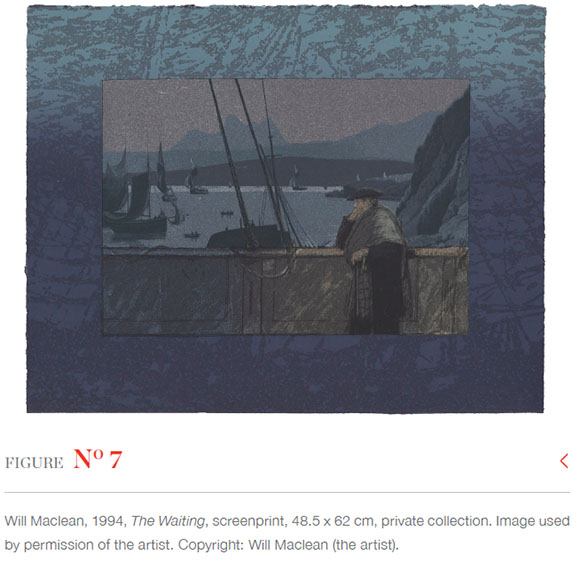

In 1994, Maclean took part in the 'Voyage Round the Coast of Scotland' project, commemorating the work of William Daniell, who depicted the coastlines of the United Kingdom in a hugely successful aquatint series in the early 1810s. A selection of Daniell's works, which gave a romanticised depiction of Highland harbours and landscapes, would, thanks to Maclean's intervention, assume new meanings with the incorporation of elements from another iconic Victorian painting produced outside the Gàidhealtachd. Through the addition of the pensive Highlander from John Watson's Nicol's Lochaber No More into the collage work The Waiting (Figure 7), and by adding his wife into the The Departure, Maclean creates a powerful reinterpretation of Daniell's sedate aquatints, reminding us that, while these touristic Georgian era works were being created, people were being actively removed from the locations they depict.

These works subtly undermine Daniell's imperial-vistas by placing working-class people at the very heart of his compositions, instead of relegated to the role of staffage. A similar reinterpretation of Nicol's work preceded Maclean by seven years on the cover of 'Letter from America', a song released by Scottish band The Proclaimers which became a top-ten success in 1986. In the artwork for the single, the couple are juxtaposed against the backdrop of a contemporary image, that of Gartcosh Steel Works which had been closed by the British Government in 1986. Allusions to economic migration both contemporary and historical are also furthered in the lyrics to the song, which had a resurgence of interest during the Scottish Independence vote in 2014 (Leadbetter 2019:1). Maclean's work avoids such heavy-handed comparisons. Instead, the artist deftly re-reappropriates Daniell's work, itself made during the height of the Clearances, to further emphasise how indifferently the people of the Gàidhealtachd were viewed outside their traditional heartlands.

In contrast to The Duke of Sutherland statue's unwelcome presence, Maclean was invited by An Lanntair Arts Centre in 1992 to create a series of new, large scale sculptural works to be situated in the landscapes of Lewis, each commemorating the communities who had chosen to fight back against landowner Lord Leverhulme in what became known as the Land Raids. These large architectural forms each responded to the landscape and history of their respective locations in a way which appropriately, and sympathetically, memorialised the crofters' hard-fought legacy. With an emphasis on locally sourced materials, and a lack of ornamentation,8 each was built by local craftsmen so that they blended in with the surrounding landscape, recalling the forms of ancient standing stones and burial mounds.

Several, such as the example at Balallan, were designed so that they provided elevated viewpoints across the landscape for locals and tourists alike. Each monument was the result of engagement with the local community, many the descendants of the land raiders themselves. Like much of Maclean's work, they are the result of a sympathetic approach to the subject matter, underpinned by a lifelong commitment to engaging with the community, culture, language and traumas of the Gàidhealtachd.

In 2015, Veering Westerly a retrospective exhibition of the work of Maclean, the Highland Laureate, was staged at An Lanntair. It would take another seven years for a gallery in the central belt to mount a similar show, with The City Arts Centre in Edinburgh's planned Points of Departure scheduled for Summer 2022.

Conclusion

In his introductory essay for the book The significance of Highland Art, art historian Murdo Macdonald (2013:1) asks: 'How are memory and history represented visually? How does visual culture develop through periods of demographic change?'. In the work of artists responding to the Highland Clearances in the preceding decades we can find a number of differing approaches to this question, each informed by the prevailing attitudes towards historical events.

While the problematic victimhood and false-equivalence of clearance, genocide and ethnic cleansing are largely being consigned to the past, a more nuanced view of Gaels as both victim and perpetrator is being established through academics such as James MacPherson who focus on the extent of Scottish involvement in Empire.9 The similarly difficult comparison of displaced Gaels with that of modern refugees and economic migrants continues unabated however, with Scottish institutions such as The Fleming-Wyfold Collection and the Fine Art Gallery in Edinburgh continuing to hang iconic clearance works such as Faed's Lochaber No More and Nicol's Last of the Clan alongside the recent migration work of Turner Prize Winer Oscar Murillo and Iman Tajik in 2019 and 2020 respectively. Murillo commented that, in his incorporation of clearance work, he wanted to 'hold a mirror and show that notions of social movement are not other or exotic, but instead have roots in this country due to socio-economic change' (Knox 2019:1). This is an approach presumably shared by other artists including Tajik and McElhinney. It remains to be seen if the fate of the Gaels will prove apposite given their ambiguous role within the British State at home, and then abroad.

The words of poet and academic Alan Riach, speaking with artists Will Maclean and Sandy Moffat in 2018, are perhaps the most appropriate way in which to frame our discussions about art and the Highland Clearances. Only through acknowledging the divide between mythology and fact can artists begin to address realities and recognise the many victims of events like those which occurred in the Gàidhealtachd - and beyond.

Myth has a greater power than history. There's a history of the Highland Clearances and there's a mythology of the Highland Clearances. The mythology carries the heart of the event while the history holds the facts. The myth of the Clearances had a powerful impact especially for artists, poets and writers of all kinds, and that impact continued to have its effect for generations, into the present day (Riach 2018:1).

Notes

1 . According to the most recent census data, there are some 60,000 speakers of Scottish Gaelic, with the highest percentage of speakers by population living on the west coast of Lewis (Scottish Government 2016:1). They account for just over 1% of the Scottish population.

2 . The Jacobite uprising of 1745 was an attempt by Catholic Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne on behalf of his father, James Francis Edward, the son of King James II and VII of England, Scotland and Ireland. British forces, led by the Duke of Cumberland on behalf of his brother the Hanoverian King George II, defeated the Jacobite rebellion in 1746. Charles Edward Stuart fled to France, never returning to Scotland.

3 . A longer discussion of these events is available in Christopher Fleet (2018).

4 . This issue is explored in MacKinnon (2017).

5 . It must be noted from the book The Faeds: A biography by Mary McKerrow (published in 1982) that Faed himself had close family members who emigrated to America.

6 . The author in conversation with the artist, September 2021.

7 . Rob Gibson discusses the long history of activism and The Duke of Sutherland monument here: https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2020/06/13/toppling-statues/

8 . Lewis and Harris are heartlands of Presbyterianism, in particular the Wee Free Church. Known for eschewing decoration in church buildings, they are also the home of Gaelic Psalm singing, unaccompanied by instruments. The architecture of the islands is similarly opposed to unnecessary adornments, and is more utilitarian in nature.

9 . James MacPherson writes in more detail about The Highlands and post-colonial processes in Macpherson (2020).

References

Aitchison, P & Cassell, A. 2013. The Lowland Clearances: Scotland's silent revolution, 1760-1830. Edinburgh: Tuckwell Press Ltd. [ Links ]

Alston, Al. 2021. Slaves and Highlanders: Silenced histories of Scotland and the Caribbean. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [ Links ]

Art UK website. [O]. Available: https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/oh-why-i-left-my-hame-35351 Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Ascheron, N. 1994. Blow up the Duke of Sutherland, but leave his limbs among the heather. [O]. Available: https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/blow-up-the-duke-of-sutherland-but-leave-his-limbs-among-the-heather-1441798.html Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Ashcroft, B & Griffiths, G, Ashcroft, F & Tiffin, H. 2002. The Empire writes back: Theory and practice in post-colonial literatures. Stanford: Stanford. [ Links ]

Behrens, R. 2000. Twenty-five years of expeditions into Naboland. Glasgow: Roger Billcliffe Gallery. [ Links ]

Campsie, A. 2021a. The Gaelic Dictionary funded by Slave Owners. [O]. Available: https://www.scotsman.com/heritage-and-retro/heritage/the-gaelic-dictionary-from-the-highlands-funded-by-slave-owners-3407047 Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Campsie, A. 2021b. History of Glenfinnan Monument rewritten as slavery connection emerges. [O]. Available: https://www.scotsman.com/heritage-and-retro/heritage/history-glenfinnan-monument-rewritten-slavery-connection-emerges-3091400 Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Community Land Scotland. CLS website. [O]. Available: https://www.communitylandscotland.org.uk/2020/11/new-research-reveals-extent-of-historical-links-between-plantation-slavery-and-landownership-in-the-west-highlands-and-islands/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Clark, B. 2020. Why is no-one talking about the Duke of Sutherland statue? [O]. Available: https://www.thenational.scot/news/18531378.no-one-talking-duke-sutherlands-statue/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Collier, G, Maes-Jelinek, H & Davis, G. 2007. ASNEL papers 10. Global fragments (dis)orientation in the New World Order. New York: Rodopi. [ Links ]

Devine, TM. 2018. The Scottish Clearances: A history of the dispossessed 1600-1900. London: Allen Lane. [ Links ]

Devine, TM. 2013 [1994]. Clanship to crofters' war: The social transformation of the Scottish Highlands. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Devine, TM. 2004 [1988]. The great Highland famine: Hunger, emigration and the Scottish Highlands in the nineteenth century. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers. [ Links ]

Farrell, J. 2015. Mediating History. [O]. Available: https://www.john-farrell.co.uk/writing/8vknab9up4u6gom0lx1q8vlo4z4bsp Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Fleet, C. 2018. Scotland: Defending the nation: Mapping the military landscape. Edinburgh: Birlinn. [ Links ]

Forbes, E. 2021. Henry Dundas to get new plaque telling role in slavery. [O]. Available: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/henry-dundas-to-get-plaque-telling-role-in-slavery-vmdqvwk6v Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Fry, M. 2005. Wild Scots: Four hundred years of Highland history. Edinburgh: John Murray. [ Links ]

Gibson, R. 2020. Bella Caledonia. [O]. Available: https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2020/06/13/toppling-statues/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Giles, HJ. 2007. The Bottle Imp. [O]. Available: https://www.thebottleimp.org.uk/2018/07/scotlands-fantasies-of-postcolonialism/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Gouriévedis, L. 2016. The dynamics of heritage: History, memory and the Highland Clearances. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hannan, M. 2019. National Galleries' exhibition on Scots migration omits Clearances. [O]. Available:chttps://www.thenational.scot/news/17810855.national-galleries-exhibition-scots-migration-omits-clearances/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Hassan, N. 2019. No colour bar: Highland remix: Clearances to colonialism. [O]. Available: https://timespan.org.uk/programme/exhibitions/no-colour-bar-highland-remix/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

HES - Historic Environment Scotland. [Sa]. CANMORE record for Suisnish. [O]. Available: https://canmore.org.uk/site/11423/skye-suisnish Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Hunter, J. 2000. The making of the crofting community. Edinburgh: John Donald Publisher. [ Links ]

Hunter, J. 2015. Set adrift upon the world: The Sutherland Clearances. Edinburgh: Birlinn. [ Links ]

Kay, B. 2011. The Scottish world: A journey into the Scottish diaspora. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. [ Links ]

Knox, J. 2019. Fleming Collection's historic painting causes a stir at the Turner Prize. [O]. Available: https://www.flemingcollection.com/scottish_art_news/news-press/fleming-collections-historic-painting-causes-a-stir-at-the-turner-prize Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Leadbetter, R. 2019. Letter from America: A lament for Thatcherism and the Highland Clearances. [O]. Available: https://www.heraldscotland.com/life_style/arts_ents/17686358.letter-america-lament-thatcherism-highland-clearances/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Maclean, M & Carrell, C (eds). 1986. As an Fhearann/From the Land: Clearance, conflict and crofting. Edinburgh, Stornoway & Glasgow: Mainstream, An Lanntair, and Third Eye Centre. [ Links ]

Maclean, M & Murray, R (eds). 1998. MacTotem - Reviewing the Duke of Sutherland monument. Stornoway: An Lanntair & Prioseact nan Ealan. [ Links ]

Maclean, M & Dorgan, T (eds). 2002. An Leabhar Mòr: The great book of Gaelic. Edinburgh: Canongate. [ Links ]

Macdonald, M. 2013. Rethinking Highland art: The visual significance of Gaelic culture/ Sealladh as Ur air Ealain na Gàidhealtachd: Brigh Lèirsinn ann an Dualchas nan Gàidheal. Edinburgh: Royal Scottish Academy. [ Links ]

Macdonald, S. 1997. Reimagining culture: Histories, identities and the Gaelic Renaissance. Oxford: Berg. [ Links ]

Macmillan, D. 2002. The art of Will Maclean: Symbols of survival. Edinburgh: Mainstream. [ Links ]

Macmillan, D, 1990. Scottish art, 1460-1990. Edinburgh: Mainstream. [ Links ]

Macpherson, J. 2020. History writing and agency in the Scottish Highlands: Postcolonial thought, the work of James Macpherson (1736-1796). Northern Scotland Journal 11(2):123-138. [ Links ]

McElhinney, F. [Sa.] Interview on Document Scotland. [O]. Available: https://www.documentscotland.com/frank-mcelhinney/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

McElhinney, F. [Sa.] Introduction to the series 'Adrift'. [O]. Available: https://frankmcelhinney.blogspot.com/2019/08/adrift-2016.html Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

MacKinnon, I. 2017. Colonialism and the Highland Clearances. Northern Scotland Journal 8:22-48. [ Links ]

McKay, I. 2021. The Map is not the Territory. Art North Magazine. Tongue: AN Publishing. [ Links ]

McKerrow, M, 1982. The Faeds - A biography. Edinburgh: Canongate. [ Links ]

Miller, P. 2009. Ossian and Scotland: 'Part of our own history, which at long last, we can stop being embarrassed about'. [O]. Available: https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/17724291.ossian-scotland-part-history-long-ast-can-stop-embarrassed-about/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Misneachd. 2017. About us. [O]. Available: https://www.misneachd.scot/mardeidhinn Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Morrison, J. 2003. Painting the nation: Identity and nationalism in Scottish painting, 1800-1920. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press [ Links ]

Murray, R. 2021. An Lanntair Gallery. [O]. Available: https://lanntair.com/virtual_exhibitions/mactotem-reviewing-the-duke-of-sutherland-monument-exhibition/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

National Galleries of Scotland. [Sa]. William McTaggart - artist page. [O]. Available: https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/features/william-mctaggart Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Peacock Visual Arts - The Waiting. [Sa]. [O]. Available: https://peacock.studio/shopping/products/the-waiting-will-maclean Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Peacock Visual Arts - The Departure. [Sa]. [O]. Available: https://peacock.studio/shopping/products/the-departure-will-maclean Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Reid, C & Reid, C. 1987. Letter from America. Chrysalis Records Ltd. London. [ Links ]

Richards, E. 2008. The Highland Clearances: People, landlords and rural turmoil. Edinburgh: Birlinn. [ Links ]

Riach, A. 2018. The arts of the Highlands and Islands: Part One. [O]. Available: https://www.thenational.scot/news/16176331.arts-highlands-islands-part-one/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Richards, E. 2007. Debating the Highland Clearances. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [ Links ]

Scotsman Newsroom. 2017. National Museum facing protests over lack of Gaelic in Jacobites exhibition. [O]. Available: https://www.scotsman.com/whats-on/arts-and-entertainment/national-museum-facing-protests-over-lack-gaelic-jacobites-exhibition-847840 Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Stroh, S. 2007. Scotland as a multifractured postcolonial go-between? Ambiguous interfaces between (post-)Celticism, Gaelicness, Scottishness and postcolonialism, in Global fragments (dis)orientation in the New World Order, edited by G Collier, H Maes-Jelinek and G Davis. New York: Rodopi:181-199. [ Links ]

Scottish Government. 2016. The Gaelic Language Plan (2016-2021). [O]. Available: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-gaelic-language-plan-2016-2021/pages/4/#:~:text=National%20Demographics%20%2D%20Number%20of%20Gaelic% 20Speakers&text=The%20total%20number%20 of%20people,were%20able%20to%20speak%20Gaelic Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Schrag, A. [Sa.] Official website. [O]. Available: http://www.anthonyschrag.com/pages/Physical-wrestlinghistory.html Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Schrag, A. 2013. BBC News. Artist 'lectured' sheep on Highland Clearances. [O]. Available: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-21790062 Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Shakur, F. 2015. A sweet forgetting: Slavery, sugar and Scotland. [O]. Available: https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/10/07/stephen-mclaren-jamaica-sugar-scotland-caribbean/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Styles, D. 2020. How Scotland is taking a different path when it comes to facing the past. [O]. Available: https://www.thenational.scot/news/18712744.scotland-taking-different-path-comes-facing-past/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Thomson, DS (ed). 1983. The companion to Gaelic Scotland. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

UN IOM - United Nations International Organization for Migration. 2016. - UN IOM - Mediterranean Migrant Arrivals in 2016: 204,311; Deaths 2,443. [O]. Available: https://www.iom.int/news/mediterranean-migrant-arrivals-2016-204311-deaths-2443 Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Victoria & Albert Museum collections. [Sa]. The last of the clan. [O]. Available: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O687821/the-last-of-the-clan-print-simmons-william-henry/ Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Wilson, B. 2001. Appreciation: John Prebble. [O]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2001/feb/09/guardianobituaries Accessed 26 October 2021. [ Links ]

Worthing, KG. 2006. The landscape of clearance: Changing rural life in nineteenth-century Scottish painting. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow. [ Links ]