Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a15

ARTICLES

Occupying Space: Land art and the Red Power Movement, c. 1965-78

Scout Hutchinson

Institute of Fine Arts, New York University (MA 2020), New York City, USA. cbh338@nyu.edu

ABSTRACT

Scholars of Land art have long acknowledged the influence of pre-Columbian Indigenous art on earthworks made in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s, identifying this appropriation as an extension of modernism's preoccupation with "primitivism". Less attention has been paid to the temporal and ideological parallels between Land art and the Red Power movement - a historic moment in Indigenous American rights activism that comprised a series of highly publicised protests and land occupations at sites like Alcatraz Island, Wounded Knee, and Mount Rushmore. As this wave of activism intensified and brought issues of land ownership and the legacy of settler colonialism to the forefront of the American public's concerns, a number of non-Native artists began working with land as their primary material. By situating a selection of works by artists Michael Heizer and Dennis Oppenheim within the historical framework of Red Power - including media representations of activists and countercultural appropriations of Indigenous American traditions - another social lens emerges through which to interpret these iconic works of Land art. The issues of displacement, territorial borders, and trespassing that emerge in Heizer's and Oppenheim's works take on new meaning when considered in relation to Red Power activists' interrogation of broken historic treaties and demands for the return of stolen lands.

Keywords: Red Power, American Indian Movement, Indigenous land rights, land occupation, Land art, earthworks, Dennis Oppenheim, Michael Heizer, site specificity, site-specific art, place-based art.

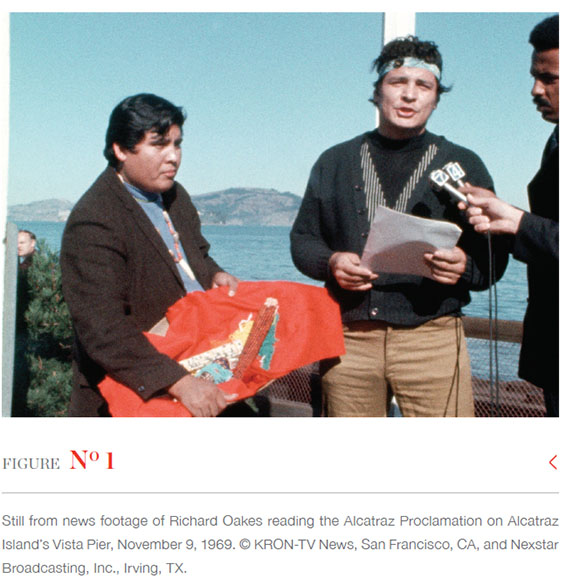

In November 1969, Native American activist Richard Oakes stood on the pier at Alcatraz Island, surrounded by members of the press.

He read from a document known as the Alcatraz Proclamation, written by a group of Indigenous activists who went by the name Indians of All Tribes. The statement began: 'We, the native Americans, reclaim the land known as Alcatraz Island in the name of all American Indians by right of discovery' (Indians of All Tribes 2017:[Sp]). The infamous Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary had been shuttered in 1963, meaning this small island off the coast of San Francisco was now designated as surplus federal land, which historical government policies had promised to Native Americans.1 For the next year and a half, Oakes and his fellow activists took control of Alcatraz in an effort to reclaim the island and direct public attention to long-ignored Indigenous rights.2

The Occupation of Alcatraz was part of a larger moment in US history known as the Red Power movement, roughly a decade of activism that took place between the mid-1960s and late-1970s. Spearheaded by various pan-Indian activist groups - one of the most prominent being the American Indian Movement (AIM) - Red Power comprised a series of highly publicised protests and land occupations. These actions called attention to the centuries of genocide and displacement suffered under historical American settler colonialism, as well as the more recent threats of termination legislation - government policy initiated in the mid-twentieth century with the goal of assimilating Native Americans into urban areas while dismantling federal recognition of tribal sovereignty and reservation land.3 Though the aims of Red Power were multifaceted and largely directed toward self-determination, one core incentive, as described by art historian Jessica L. Horton (2017:22), was to uphold 'the rights of Native peoples to live freely on their ancestral lands, confirmed by treaties that the US government signed in the wake of the Declaration of Independence but repeatedly violated'.

As this wave of Native American activism intensified and the legacy of westward expansion came freshly under interrogation in the public eye, a number of contemporary non-Native artists began working with land as their primary material. These Land artists, whose work often took the form of large-scale structures or interventions in the landscape, tended to appropriate themes from pre- and postcolonial Indigenous American cultures. As scholars of the movement have noted, many of these earthworks allude to geoglyphs, earth mounds, structures for observing celestial phenomena, and other elements of Indigenous American art and architecture. In a gesture reminiscent of the Peruvian Nazca Lines, Walter De Maria bulldozed marks into Nevada's desert floor (Las Vegas Piece 1969); James Turrell modeled his massive earthwork Roden Crater (1977-present) after ancient observatories at sites like Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon; and Michelle Stuart arranged rocks into a medicine wheel on a plateau in the Pacific Northwest (1979).

While it can, and has, been argued that the works' references to Indigenous art are simply an extension of Modernism's preoccupation with "primitivism", a lineage that scholars like Barbara Braun (1993) and Lucy R. Lippard (1983) have traced, it is difficult to ignore the temporal and ideological parallels between Land art and the Red Power movement. Each gained momentum during the late 1960s, tapering off toward the latter end of the 1970s, and both were concerned with concepts of space - Land art with the aesthetics of space, and Red Power with its cultural significance and political charge. While non-Native Land artists may not have been directly involved in Red Power-related protests, the two movements' concurrence begs the questions: what are the implications of producing a work of Land art at a time when land rights, Indigenous self-determination, and the legacy of settler colonialism were contentious issues in the public sphere?4

Despite the parallels between these two movements, the influence of Indigenous rights activism on Land art has remained largely unconsidered in scholarship.5 By situating Land art within this socio-political framework - including media representations of Indigenous activists and related countercultural appropriation - we may discover valuable social context that offers another lens through which to interpret these iconic works of postmodern art. Rather than detail the ways in which non-Native Land artists referenced pre-Columbian Indigenous art, this essay will focus on a selection of artworks by Michael Heizer and Dennis Oppenheim, whose land-based projects seem to correspond to central motivations behind the Red Power movement. The issues of displacement, territorial borders, and trespassing that emerge in their work take on new meaning when considered in relation to Red Power activists' interrogation of broken historic treaties and demands for the return of stolen lands, demonstrating how Red Power is a critical social context to consider when analysing works of art that engaged with land at this time.

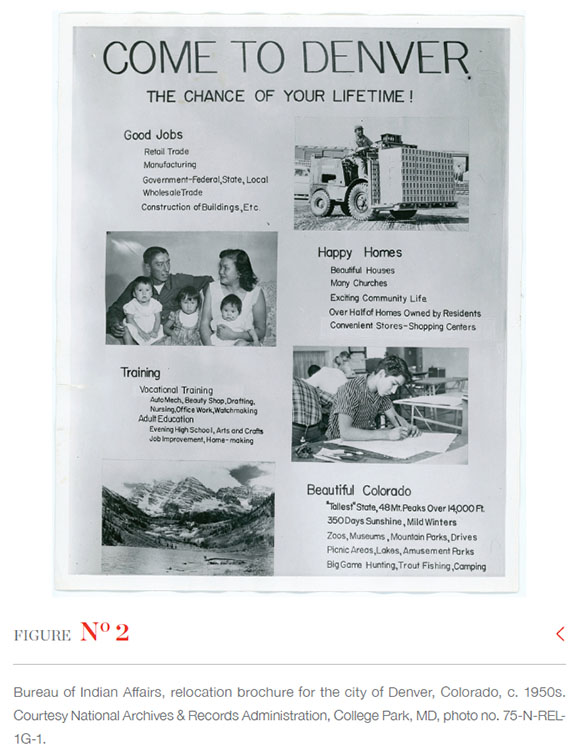

In a recent interview, Heizer (2016:[Sp]) reflected on the treatment of Native Americans in the 1960s, a time when, he claims, the country was not 'really proud of its contemporary indigenous culture. Now it's a bigger deal. There's more emphasis, more intensity, more appreciation. Back then, it wasn't so fun, was it?'. Given its neglect in most studies of American history, a brief outline of key Red Power events may help provide useful context. Though the aforementioned 1969-1971 occupation of Alcatraz was certainly a major moment in Native American activism and is widely recognised as the catalyst for the series of occupations that followed, it is helpful to understand the event's precursors. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the country's Indigenous populations were targeted by what is known as termination legislation, implemented to dissolve certain benefits Native Americans received from the federal government (Johnson, Nagel & Champagne 1997:14). The goals of termination, as described by scholars Paul Chaat Smith and Robert Allen Warrior (1996:6), were 'to move Indian people from reservations to cities, to assimilate them as quickly as possible, and to undermine reservation life'. The Indian Relocation Act of 1956, for instance, sought to entice Native Americans to move from reservations to major city centers, where they were promised professional training and other opportunities. One brochure distributed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs touts 'happy homes' and an 'exciting community life' should readers relocate to the city of Denver, Colorado.

The infrastructure to support these claims was insufficient, however, and the improved urban lifestyle this type of propaganda advertised seldom materialised.6

Termination also meant that reservation land held in trust for Native American communities would fall under the jurisdiction of the state (or states) in which it was located (Smith & Warrior 1996:7). The ramifications of this shift are best exemplified by the Pacific Northwest "fish-in" movement of the early 1960s. Where certain nineteenth-century treaties guaranteed local Native Americans the right to continue fishing both on and off reservation land, termination permitted state law to deny them access to off-reservation waters.7 The ensuing fish-in protests garnered considerable media attention and ultimately resulted in the Supreme Court case United States v. Washington, which successfully reinstated Indigenous fishing rights in the early 1970s. The fish-in movement was, according to the scholar Vine Deloria, Jr. (1997:45), the era's 'first [Native American] activism with an avowed goal', setting the stage for the occupation of Alcatraz and the series of organised protests to come while firmly establishing the Indigenous rights cause in the public eye.

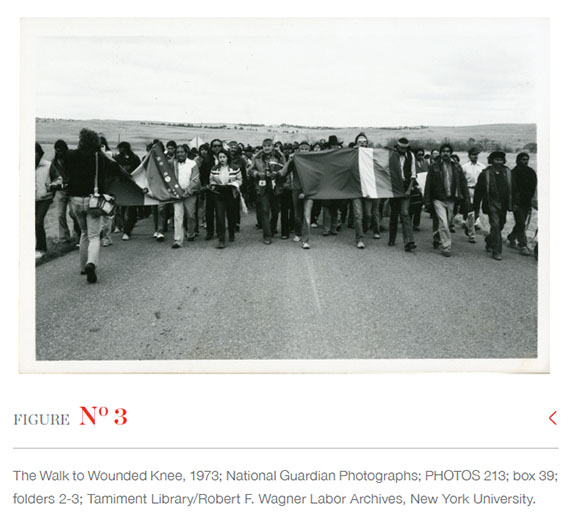

As the first major Red Power action, the occupation of Alcatraz sparked nearly a decade of protests and comprised roughly 70 "property takeovers" by Native American activists across the country (Johnson, Nagel & Champagne 1997:9,15). These included both successful and failed attempts to occupy sites such as Ellis Island, Washington State's Fort Lawton, and Plymouth Rock (all in 1970), the town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota (in 1973), and the Mount Rushmore National Monument (several times throughout the 1970s) (see Smith & Warrior 1996:88).8

The 1972 Trail of Broken Treaties and 1978 Longest Walk were coast-to-coast caravan and walking demonstrations that ended at the nation's capital. There participants protested the dysfunctional Bureau of Indian Affairs and controversial congressional bills. Not every action resulted in land being returned to Native American communities, but notable victories included the reclamation of land taken from the Menominee people of Wisconsin via termination legislation, as well as the restoration of the sacred site of Blue Lake in northern New Mexico to the Taos Pueblos in 1970.

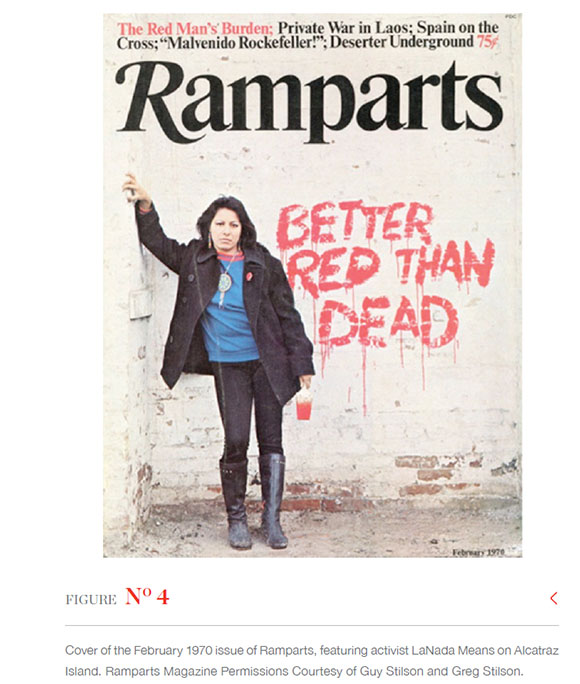

Though Red Power has since become overshadowed in the nation's historical memory by other contemporaneous socio-political events, such as the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War, a brief survey of press coverage of the movement reveals that Red Power activism received a significant amount of public attention at the time. Mainstream and underground news sources alike provided in-depth coverage of occupations at Alcatraz and Wounded Knee; developments were featured regularly on television and were well-documented by publications with a national reach, such as Time, Life, and Newsweek (see Weston 1996; Wilkins & Stark 2017:243-261).9 Overall, the tone of news reports was sympathetic to protesters, if not guilty of lapsing into tired and harmful stereotypes. As scholar Mary Ann Weston (1996:134-5) explains in her analysis of depictions of Native Americans in twentieth-century journalism, news stories tended to perpetuate a rhetoric of Red Power activists as either mystical stewards of the earth or 'ancient and exotic people' belonging to a distant past. Such romantic depictions pandered to a non-Native public whose understanding of Indigenous populations was outdated and deeply inaccurate. Despite, or perhaps because of, the stereotypes the press relied on, art historians Mindy N. Besaw, Candice Hopkins, and Manuela Well-Off-Man (2018:9) argue that media coverage 'placed Native concerns firmly in mainstream consciousness within and outside the United States'.

The breadth of the reporting attracted international attention and won Red Power activists the support of celebrity figures; Marlon Brando10 was active in various Indigenous rights protests, while Jane Fonda visited Alcatraz after seeing a photograph of activist LaNada Means featured on the cover of the February 1970 issue of the radical publication Ramparts (see Johansen 2013:17). A New York Times article from later that summer reports on a Southampton social gathering organised to raise awareness for Native American activism (Curtis 1970:35). Present were prominent Native representatives like LaDonna Harris, founder of Americans for Indian Opportunity, and Floyd Westerman, a musician who performed tracks from his 1969 folk album titled Custer Died for Your Sins. Also in attendance were New York socialites and art-world affiliates, most notably Robert and Ethel Scull. The Sculls were avid art collectors and notable patrons of earthworks by artists like Heizer and Walter De Maria.

A few years after the end of the Wounded Knee occupation, artist Andy Warhol would memorialise one of its key leaders, Russell Means, in a series of painted portraits titled The American Indian (Russell Means) (1976). These head-and- shoulders portraits show Means gazing out at the viewer, his figure obscured by thick swaths of garish-colored paint - an approach typical of Warhol's acrylic-and-silkscreen works, in which he depicted celebrities, political figures, and art world elites. Though the reasoning behind Warhol's alleged desire to paint a subject who 'personified the contemporary American Indian' is unclear, Warhol's preoccupation with events of national importance indicates the extent to which the Red Power movement had saturated the media and become a public concern.11

The appropriation of Native American traditions by non-Native counterculture is further testament to the extent to which Red Power suffused popular culture at this time, and though relevant examples are too numerous to describe here, the following example helps to encapsulate this phenomenon. Stewart Brand, founder of the influential publication Whole Earth Catalog, was one of many counter-culturalists drawn to Native American culture and activism; he worked as a photographer for Oregon's Warm Springs Reservation, participated in Native American Church meetings in Nevada, and created the multimedia installation America Needs Indians, which he presented at psychedelic music festivals during the mid-1960s (see Smith 2012:46-47). After reading Ken Kesey's 1962 novel One flew over the Cuckoo's nest, Brand determined that the leader of the Merry Pranksters had rightly identified a link between the nation's youth movement and its Indigenous peoples. Brand (cited by Smith 2012:47) claimed that the controversy between the novel's narrator, Chief Bromden - a Native American psychiatric patient - and the hospital's authoritarian head nurse was 'identical with Indians versus Dalles Dam or me versus the Army'. His mention of the Dalles Dam references a protest led by several Indigenous nations to preserve a culturally significant section of the Columbia River, which was threatened (and ultimately flooded) by the construction of a hydroelectric dam in the late 1950s.12 Like many white counter-culturalists of his time, Brand seized on an over-simplistic parallel between his own anti-establishment youth movement and Native Americans' struggles with the federal government.13

Because these struggles were often rooted in matters of land and broken treaties, Horton (2017:6,33) has described the Red Power movement as being motivated by motivated by 'indigenous spatial politics'. In less than a century, territory owned by Native Americans had decreased from about two billion acres in the 1880s to 50 million in the 1970s - roughly one 40th of the original acreage (Deloria, Jr. 1975:29).14 As the struggle to maintain ancestral land and reclaim sacred sites progressed in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Horton (2017:33) points out that a new relationship to land and site was simultaneously occurring in the art world: 'the rise of the so-called spatial turn'. In her 1979 essay 'Sculpture in the Expanded Field', art historian Rosalind Krauss (1979:41) argues that the emergence of Land art - which presented an amalgamation of sculpture, installation, landscape, and architecture - blurred formerly secure boundaries between artistic disciplines and signaled a 'rupture' between modern and postmodern sculptural practices. In the essay, Krauss (1979:41) seeks to redefine the limits of sculpture, a discipline 'historically bounded' or determined by medium. She 'map[s]' out an 'expanded but finite' methodological structure intended to account for these new postmodern practices of 'site construction' and 'marked sites' - work made in response to a specific place, and whose meaning is contingent on being experienced in that environment (Krauss 1979:41-44, emphasis in original).

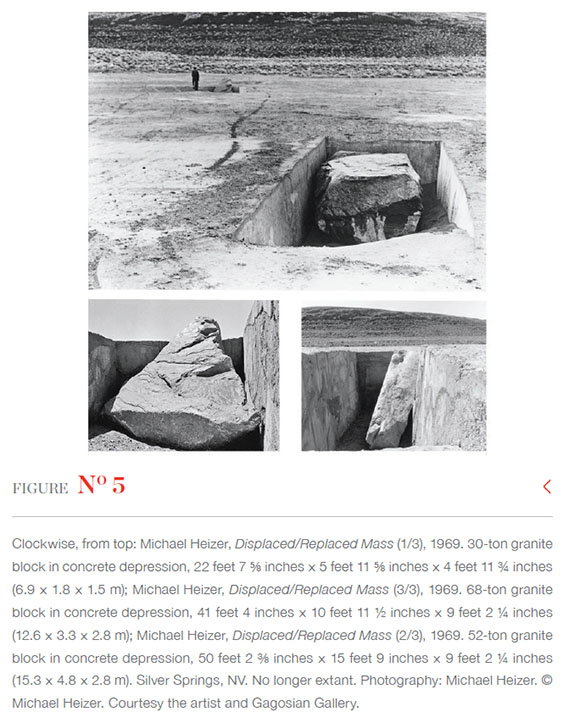

Site specificity was certainly a fundamental condition of Land art, but other considerations of place and location also surface in the work. In light of Red Power's emphasis on the effects of forced relocation and efforts to reclaim land, it is interesting to note moments in which displacement appears as a driving concept. Several earthworks by Heizer perform a rupture in geographic place by extracting materials like earth and stone from their original site and placing them in a foreign location; other projects, however, seek to repair this displacement. Heizer's 1969 Displaced/Replaced Mass consisted of a trio of granite boulders removed from the mountains in High Sierra, California, and transported to grave-like depressions carved into the desert floor near Silver Springs, Nevada (see Beardsley 2006:16).15

Displaced/Replaced Mass embodied an intentional process of returning material to its original source; in a 1969 letter to his aforementioned patron Robert Scull, Heizer (Archives of American Art 1969) describes how the boulder had once been 'buried beneath a huge range of metamorphic rock, and was exposed during the uplift that formed the mountains. I will return a token amount to its previous elevation on the desert floor'.

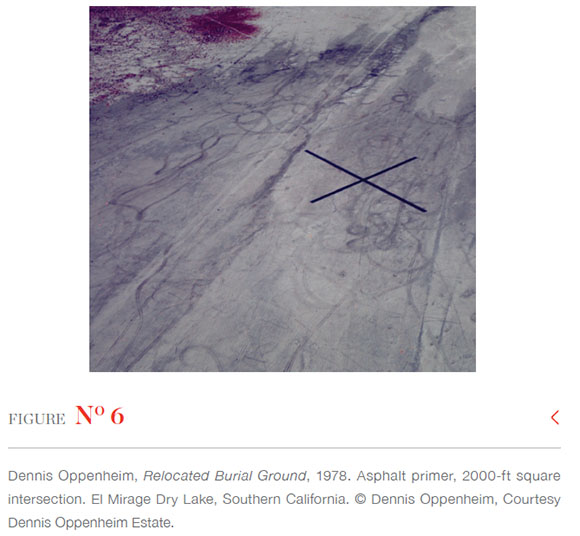

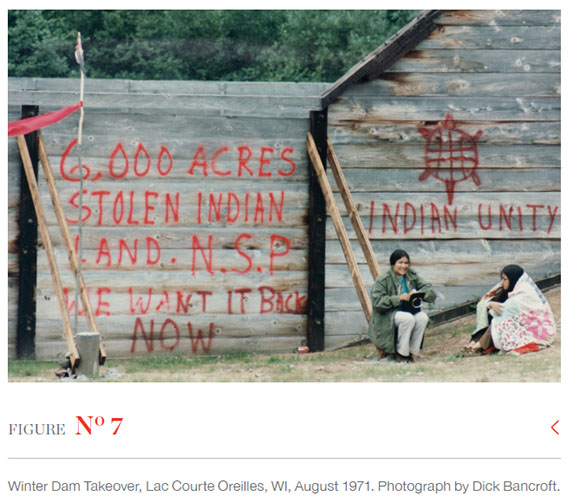

Dennis Oppenheim's "transplants" similarly involved moving material from one location to another.16 One of his last Land art pieces, Relocated Burial Ground (1978), is not an actual transplant as such; its title merely suggests that something has been newly buried beneath a 2,000-square-foot "X" made of asphalt primer applied to the desert floor of El Mirage Dry Lake in Southern California.17 The "X", perhaps indicating a site of interest on a map, begs the question: can something as site specific as a burial ground be transferred to a different geographic location and still maintain its sacred identity?18 The work's title and ephemeral nature (the work is no longer extant), in fact, point beyond site specificity to what scholar Yates McKee (2010:53) calls 'site insecurity'. This condition suggests both the sacrality of a specific site and the possibility of 'its profane dislocation, uprooting, or disinterring' (McKee 2010:53), which was a significant concern for many Native American communities and Red Power activists. A 1971 AIM-led takeover at Lake Chippewa in Wisconsin, for instance, protested the renewal of electric company Northern States Power's (NSP) license of a dam which had flooded local burial grounds in the 1920s (see Brown 1996:255-6).

Although NSP had promised to relocate the graves, the company never followed through. In this context, Oppenheim's Relocated Burial Ground represents the very opposite of a secure, permanent monument; instead, it emphasises the precarity of culturally significant Indigenous sites in the face of American industry and development projects.

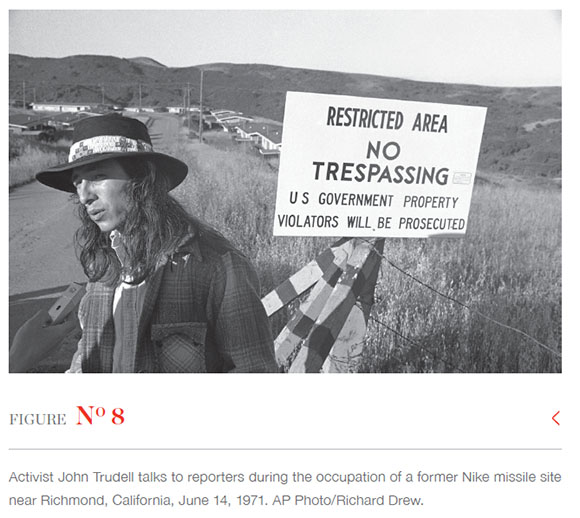

In a 1971 article for Art in America, critic Dave Hickey observed Land art's preoccupation with dislocation, noting that these earthworks also seemed to 'deriv[e] energy from sophisticated forms of trespassing' (1971:48, emphasis added). Indeed, certain Land artists did address the politics of territory and borders, both conceptually and as part of the work's production. While they sometimes leased or purchased property, or sought permission from local landowners, at other times they realised their earthworks illegally on federal land, as in the case of some of Heizer's early works, including the Nine Nevada Depressions of 1968. As he explains: 'We had no permission from the federal government to do this on public lands. These were playas, dry lakes. But we just did it. We just got them built' (Heizer 2016:[Sp]). His defiant disregard of land ownership evokes Red Power activists' own engagement with the strategy of trespassing: by "illegally" occupying federal property to reclaim it, they pointed to the trespasses inherent in American settler colonialism.

The stakes, of course, were drastically different. Where Heizer's anti-authoritarian trespasses were made in order to realise temporary aesthetic interventions in the landscape, Red Power activists were seeking the permanent return of their own stolen land. When asked whether the 1971 occupation of a Nike missile site near San Pablo, California, was an act of government defiance or an attempt to establish a community, activist John Trudell (cited by KQED News 1971) responded: 'I think they're both the same...it seems like when you get Indian people together now, and we just want to live, that's defying to the government already'.

A number of Oppenheim's early Land art pieces also comment on the nature of borders and private property. Works like Boundary Split and Time Line (both 1968), take the form of cuts made into the frozen St. John River that divides Maine and New Brunswick and allude to the boundaries that demarcate different nations and time zones.19 A year later, Oppenheim burned a 35-foot-wide cattle brand mark into a hillside just northeast of San Francisco.20 Normally applied to livestock to designate it as a rancher's property, the circumscribed "X" seared into the earth instead raises questions of land ownership. The Bay Area, of course, was one of the major urban relocation sites for Native Americans impacted by termination legislation in the 1950s, and San Francisco would eventually become a locus of Red Power activism, not the least of which was the Alcatraz occupation, which began the same year that Oppenheim created Branded Mountain.21

Reflecting on this period of his career, Oppenheim (cited by Boettger 2002:187) has remarked: 'I had this feeling that my activity on land had to carry with it some form of violence - something akin to the real world'. Yet mimicking the violence wrought by colonialism and industry as a form of social critique necessarily involved the use of what Horton (2017:33) calls the 'tools of modularization...by which colonization is secured'. Though the earthworks presented here may have pointed to the violence and greed inherent in colonialism, many other iconic examples of Land art also often adopted colonialism's very same methods of surveying, documenting, and reshaping the land, using engineering, cartography, photography, and in the case of Heizer, a hired assistant who searched out new sites on his behalf (see Kett 2015:150n60).

These more aggressive approaches to Land art may have induced a certain degree of skepticism in Native artists at the time, perhaps providing some explanation as to why there appear to be few who employed the same monumental, environmental, and site-specific modes practiced by their white contemporaries.22 The commercial market for Native American art could also have been a contributing factor; though it was beginning to evolve by the 1960s, the market was still largely driven by non-Native collectors' tastes for what they considered to be "traditional" Indigenous painting, jewelry, and pottery (Bernstein 1999:66-68; Besaw, Hopkins & Well-Off-Man 2018:8-9), which could have discouraged forays into land-based installation.23 Furthermore, though the Land art movement may have seemed novel within the postwar Euro-American art world, art historian Alicia Harris (2020:7) reminds us that these earthworks represent only 'a small portion of a millennia long [sic] tradition of creating place-based structures and site-specific interventions... Indigenous peoples have made visually innovative in-situ constructions on the land from time immemorial'. The fact that so much of Land art is indebted to centuries-old Indigenous traditions - including adobe structures, irrigation systems, burial mounds, and geoglyphs - may reasonably have diminished the movement's radicality in the eyes of Native artists.

In his contribution to a 1972 issue of Art in America devoted to the topic of "The American Indian", artist Lloyd Oxendine compiled a selection of work by 23 contemporary Native artists (1972:62-3).24 Those selected are represented primarily by painting and sculpture, with only two artists whose work engages with environmental site specificity, albeit to a minimal degree.25 Oxendine's introduction to the article may provide further insight into the rarity of postwar Indigenous artists working with and in the landscape; he explains that many of these artists were attempting to dismantle prevailing stereotypical representations of Indigeneity, one of which was the romantic concept of Indigenous culture as a model of environmental harmony. He goes on to explain that though many of these artists were concerned with ecological issues, they 'nonetheless shunned the pastoral ideal in their work. Perhaps because many have personally experienced the limitations and restrictions of rural life, they have rejected the simplicity of such an answer' (Oxendine 1972:59). To Native artists of the time, many of the iconic earthworks by white artists, with their references to an idealised precolonial past, may have presented an art form that served only to perpetuate the stereotypes they, like Red Power activists, sought to challenge.

Site-specific land-based works by contemporary Indigenous artists began to appear with increasing frequency about a decade after the tail end of the Land art movement - perhaps notable for the temporal proximity to the controversial 1992 Columbus Quincentenary, which marked five centuries of genocide and displacement of Indigenous North Americans. In 1991, artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith organised a symposium on site-specific Land art, which she held on the Flathead Reservation in western Montana. As she reflected on the canonical Land art movement - including Michelle Stuart's Stone Alignments/Solstice Cairns and earthworks by 'other white artists who dug big holes in the desert or rearranged boulders' - Smith (cited by Abbott 1994:224) suspected Native artists would approach the tradition quite differently. She invited a group of artists and writers to Salish Kootenai College, where they worked independently and collectively on projects across the campus. James Luna collaborated with a videographer to create a film that bore Luna's singular wry humor, while another artist (who goes unnamed in Smith's account) arranged painted blocks of ice into a medicine wheel form, which left traces of pigment on the ground after the ice melted. As Smith (cited by Abbott 1994:224) recalls: 'It was totally experimental'.

Since the late 1980s, Native American and First Nations artists like Rebecca Belmore, Nicholas Galanin, Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds, Edward Poitras, the collective Postcommodity, and Christine Howard Sandoval have revisited and critiqued postwar Land art while developing their own approaches to a land-based art practice.26Stressing non-invasive actions and often involving community engagement, their work tends to honour the specific cultural history of a given site while also calling attention to the centuries-long politics of land on this continent. While these projects stem from a long tradition of environmental, site-specific sculpture, they extend out into performance, sound, film, video, and the digital sphere.27

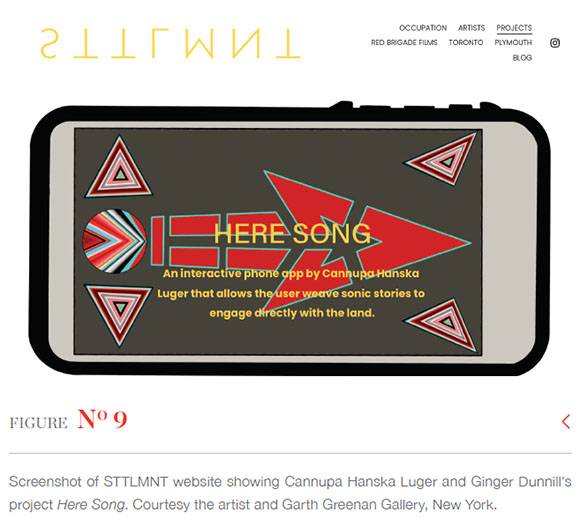

Such is the case in Cannupa Hanska Luger's collaborative web-based project STTLMNT (2020-2021). STTLMNT was originally conceptualised as a series of site-specific artworks that would occupy Plymouth's Central Park during the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower's voyage across the Atlantic. In the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, however, the project evolved into what Luger describes as an 'Indigenous digital world wide [sic] occupation' (STTLMNT 2020-2021 :[Sp]). He invited over thirty Indigenous artists from North America and the Pacific to contribute works that span media and engage themes of land, language, cultural tradition, community, and survivance in the face of colonisation. The resulting works, many of which were created within or in response to a specific place, were then exhibited virtually on the STTLMNT website. Ian Kuali'I shared photographs of Mõhai Kala Hewa / OFFERING FOR FORGIVENESS OF WRONG, a series of ground-based works made in the deserts of New Mexico. After carefully clearing the area of human-made debris, Kuali'I then arranged low piles of stone and dry grasses into striking geometric patterns. The work's intention was, according to the artist, to 'root one in the Kanaka Maoli/Native Hawaiian practice of forgiveness and resolution (Ho'oponopono)' (STTLMNT 2020-2021:[Sp]). Responding to efforts of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation to assert its water rights, Tania Willard created synthetic neon windsocks, each customised with words like 'THRASH,' 'WATER,' and 'CLAIM', and filmed and photographed them positioned in various landscapes. Luger's own participatory contribution, Here Song, takes the form of a free mobile app. Users can scan their immediate horizon line with their phone, from which the app generates a sound piece unique to their surrounding landscape.

According to Luger, the app's concept is derives from Northern Plains tribes' tradition of creating music based on contemplation of the horizon. With its emphasis on listening, situating the viewer both visually and aurally in a specific place, Here Song calls for a relationship to land that is contemplative rather than extractive, 'reinforc[ing] our belonging to place' (STTLMNT 2020-2021 :[Sp]).

Gathered together online rather than in Plymouth, the individual artworks included in STTLMNT employ what Luger describes as the 'strategy of occupation...by reclaiming (digital) space' (STTLMNT 2020-2021:[Sp]). In doing so, the project harnesses a key tactic of protest while expanding postwar Euro-American concepts of space beyond the purely physical realm. Where works by Heizer and Oppenheim may, intentionally or not, direct our attention to themes central to the Red Power movement, such as land theft, displacement, and the value of sacred places, STTLMNT firmly centers these issues, in both its content and its presentation.

Looking back at postwar Land art from the vantage point of Luger's collaborative project, we can see how critical Indigenous land rights are to the understanding of both. It would be difficult to overlook recent and ongoing efforts to protect land - Standing Rock, Oak Flat, Bears Ears-when engaging with STTLMNT. Yet surprisingly, the same contextual approach is rarely applied to non-Native Land art and the events of Red Power. Interpreting the works of Heizer and Oppenheim through this lens is, to some degree, an attempt to broaden our understanding of canonical works of Land art; the primary objective, however, is to position Red Power as an essential historical context to consider when analysing any artwork from the time that engaged with Indigenous land as material and subject.

Notes

1 . The treaty most often cited was the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie which, according to Luis S. Kemnitzer (1997:118n1), stated that 'any male Sioux over the age of eighteen not living on a reservation can claim federal land "not used for special purposes". This right was also granted to other Indians in the 1887 Indian Allotment act'. The use of the Treaty of Fort Laramie as justification for the occupation at Alcatraz was controversial for some peoples indigenous to California, such as Edward D. Castillo (cited by Johnson, Nagel & Champagne 1997:122), who explained that Red Power 'leaders would be claiming California Indian land based on a treaty the government had made with the Lakota Indians'.

2 . The 1969-71 occupation of Alcatraz was in fact the second takeover of the island by Native American activists. The first took place in 1964 and was a much shorter-term protest, conceived primarily as a way to garner publicity and raise awareness of Indigenous rights (see Smith & Warrior 1996:10-11).

3 . Once vacated, the reservation land would 'fall under the jurisdiction of whatever states and counties they were in' (Smith & Warrior 1996:7). Termination and related policies relocated over 12,500 Native Americans and impacted roughly 1.3 million acres of tribal land, much of which was 'concentrated into private ownership and, in most cases, sold' (Wilkins & Stark 2017:158).

4 . In an effort to respectfully acknowledge the Indigenous inhabitants of the land on which the earthworks discussed in this essay were realised, I have referred to a map created and maintained by the project Native Land Digital, which maps Indigenous territories, languages, and related treaties worldwide (Native Land Digital).

5 . In her text that situates the practices of artists like Jimmie Durham and James Luna within the context of the Red Power movement, Horton (2017:11) writes, 'Despite growing scholarly interest in contemporary Native American art, no study to date has traced the profound impact of AIM on subsequent aesthetic practices'. Considering the Mount Rushmore National Memorial in South Dakota within the context of the Land art movement, art historian Joshua Fisher (2011:130) also mentions the 1970 Indigenous-led occupation of the national landmark.

6 . For more on the failures of relocation and its attempt at cultural assimilation, see Momaday (1964:38).

7 . According to Troy Johnson, Joane Nagel and Duane Champagne (1997:15), these included the Medicine Creek treaty (1854) and the Point Elliot treaty (1855); protests centered around Frank's Landing on the Nisqually River, located southeast of Seattle, Washington. For more on the fish-in movement in the Pacific Northwest, see Smith (2012:18-42).

8 . The decision to occupy Wounded Knee was significant as it was the historic site of the infamous 1890 massacre of hundreds of Lakota people by the US Army. For additional discussion of actions and legislation of the period, see Deloria, Jr. (1975:30).

9 . In addition to news coverage, the social significance of certain texts published during this time period cannot be understated, including Frank Waters' Book of the Hopi (1963), Thomas Berger's Little big man (1964), Deloria, Jr.'s Custer died for your sins. An Indian manifesto (1969), and Dee Brown's Bury my heart at Wounded Knee (1970).

10 . Perhaps the best-remembered moment in Brando's involvement in Indigenous rights activism was when he refused his 1973 Academy Award, sending Apache actor Sacheen Littlefeather (also known as Marie Louise Cruz) in his stead, who delivered a speech addressing the perpetuation of racist stereotypes in Hollywood films.

11 . In order to secure Means' participation in the series, Warhol and his gallerist Douglas Chrismas contributed $5,000 to AIM's cause (Contemporary Art Day Auction 2016:[Sp]).

12 . For more on the controversial construction of the Dalles Dam, see Barber (2005).

13 . White counterculturalists often likened their "plight" to that of various oppressed communities; for more, see Deloria (1999:169).

14 . For figures on the decrease of acreage owned by Native Americans, see Wilkins and Stark (2017:167). For an explanation of the 1887 General Allotment Act (or Dawes Act) and its effect on land ownership, see Momaday (1964:37).

15 . This area of Nevada is traditional land of the Northern Paiute and the Wasiw (or Washoe) peoples.

16 . One example of Oppenheim's "transplants" is Mt. Cotopaxi Transplant (1968), for which the artist proposed transferring the topographic contours of the Ecuadorian volcano Cotopaxi onto a flat wheat field in Smith Center, Kansas, a location Oppenheim determined to be the center of the United States. Mt. Cotopaxi Transplant was only ever realised as a model, but a similar concept was carried out in Contour Lines Scribed in Swamp Grass (1968) in New Haven, Connecticut (see Boettger 2002:141).

17 . This area of Southern California is traditional land of the Yuhaaviatam and Maarenga'yam (Serrano) peoples.

18 . This may be related to the target symbol that Oppenheim used in other installations and superimposed on many of his photographs. See Blakinger (2017:[Sp]).

19 . This area is traditional land of members of the Wabanaki Confederacy, including the Abenaki, the Penobscot, the Maliseet, the Passamaquoddy, and the Mi'kmaq peoples.

20 . The area around San Pablo is traditional land of the Ohlone (Costanoan) people.

21 . The Bay Area was 'one of the largest of more than a dozen relocation sites' where Native Americans would establish 'a variety of intertribal organizations' (Johnson, Nagel & Champagne 1997:22).

22 . In my research, I have not encountered many Native American artists working in Land art during the 1960s and 1970s, though a more thorough survey of the field at this time is certainly necessary.

23 . I am grateful to Ryan Flahive, Archivist at the Library of the Institute of American Indian Arts, for bringing this point to my attention.

24 . Despite the issue's focus on Native American art, history, and politics, Vine Deloria, Jr.'s article 'The Bureau of Indian Affairs: My Brother's Keeper' is one of the only contributions written by an Indigenous author. Furthermore, the issue features a poem titled "Hi, Paleface!" written by "John Lefeather", a nom de plume of the publication's white editor Brian O'Doherty. The issue has since received criticism for such oversights, which Art in America's October 2017 issue sought to address (see Ash-Milby 2017:[Sp]).

25 . Michael G. McCleve's welded steel and iron sculpture is photographed outdoors against the backdrop of the sky while Larry Golsh's minimalist polyester and acrylic sculpture is laid out directly on the earth.

26 . A more comprehensive study of contemporary Indigenous place-based art and responses to the Land art movement of the 1960s and 1970s can be found in Harris (2020). The following sources also serve as an introduction to the topic and touch on related issues of land use and ownership (see Baum 2010; Boetzkes 2010:40-55; Gilbert 2009; Lippard 2014; Morris 2019; Nemiroff, Houle & Townsend-Gault 1992; Scott & Swenson 2015; Taylor & Gilbert 2009).

27 . In a recent essay, artist and art historian Nathan Young (2021:38) discusses artist seth cardinal dodginghorse's engagement with protest, land rights, and the 'aesthetics and politics of sound'.

References

Abbott, L (ed). 1994. I stand at the center of the good. Interviews with contemporary Native American artists. Lincoln & London: University of Nebraska Press. [ Links ]

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Robert Scull papers, 1955-circa 1984, bulk dates 1965-1970. Series 2: Correspondence, 1965-circa 1984. Box 3, folder 7: Heizer, Michael, circa 1968-circa 1971. [O]. Available: https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/robert-scull-papers-6406/series-2/box-3-folder-7 Accessed 29 September 2020. [ Links ]

Ash-Milby, K. 2017. Art Warriors and Wooden Indians. [O]. Available: https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/art-warriors-and-wooden-indians-63296/ Accessed 29 January 2020. [ Links ]

Barber, K. 2005. Death of Celilo Falls. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [ Links ]

Baum, K. 2010. Nobody's property. Art, land, space, 2000-2010. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Art Museum. [ Links ]

Beardsley, J. 2006. Earthworks and beyond. Contemporary art in the landscape. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B. 1999. Contexts for the growth and development of the Indian art world in the 1960s and 1970s, in Native American art in the twentieth century, edited by WJ Rushing III. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Besaw, MN, Hopkins, C & Well-Off-Man, M. 2018. Art for a new understanding. Native voices, 1950s to now. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. [ Links ]

Blakinger, JR. 2017. Ritual aesthetics. Salt Flat and systems, in In focus. Salt Flat 1968 by Dennis Oppenheim, edited by JR Blakinger. London: Tate Research Publication. [ Links ]

Boettger, S. 2002. Earthworks. Art and the landscape of the sixties. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Boetzkes, A. 2010. The ethics of earth art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Braun, B. 1993. Pre-Columbian art and the post-Columbian world. Ancient American sources of modern art. New York: Harry N. Abrams. [ Links ]

Brown, R. 1996. Indian resurgence. From termination to self-determination, 1961-91, in Classroom activities on Wisconsin Indian treaties and tribal sovereignty. Madison: Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction:254-258. [ Links ]

Contemporary Art Day Auction, Lot No. 139: Andy Warhol, The American Indian (Russell Means). 2016. [O]. Available: https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2016/contemporary-art-day-auction-n09573/lot.139.html# Accessed 12 February 2020. [ Links ]

Curtis, C. 1970. Andrew Stein gives a lavish party on L.I. with Indians as honor guests. The New York Times 13 July:35. [ Links ]

Deloria, PJ. 1999. Playing Indian. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Deloria, Jr., V. 1975. The Indian movement. Out of a wounded past. Ramparts Magazine March:28-32. [ Links ]

Deloria, Jr., V. 1997. Alcatraz, activism, and accommodation, in American Indian activism, Alcatraz to the Longest Walk, edited by T Johnson, J Nagel & D Champagne. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press:45-51. [ Links ]

Fisher, J. 2011. Empire makers. Earth art and the struggle for a continent. Public Art Dialogue 1(1):119-136. [ Links ]

Gilbert, B (ed). 2009. LAND/ART New Mexico. Santa Fe, NM: Radius Books. [ Links ]

Harris, A. 2020. Homescapes. Indigenous Land art and public memory. PhD thesis, University of Oklahoma, Norman. [ Links ]

Heizer, M. 2016. Michael Heizer. Interview by Heiner Friedrich. [O]. Available: https://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/michael-heizer#slideshow_48446 Accessed 3 January 2020. [ Links ]

Hickey, D. 1971. Earthscapes, landworks, and Oz. Art in America 59:40-49. [ Links ]

Horton, JL. 2017. Art for an undivided earth. The American Indian Movement generation. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Indians of All Tribes. 2017. The Alcatraz Proclamation. Annotated. [O]. Available: https://thenewinquiry.com/the-alcatraz-proclamation-annotated/ Accessed 28 August 2021. [ Links ]

Johansen, BE. 2013. Encyclopedia of the American Indian Movement. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC. [ Links ]

Johnson, T, Nagel, J & Champagne, D (eds). 1997. American Indian activism, Alcatraz to the Longest Walk. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [ Links ]

Kemnitzer, LS. 1997. Personal memories of Alcatraz, 1969, in American Indian activism, Alcatraz to the Longest Walk, edited by T Johnson, J Nagel & D Champagne. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press:113-118. [ Links ]

Kett, RJ. 2015. Monumentality as method. Archaeology and Land art in the Cold War. Representations 130(Spring):119-151. [ Links ]

Krauss, R. 1979. Sculpture in the expanded field. October 8(Spring):30-44. [ Links ]

KQED News. 1971. American Indians occupy Nike Missile site in San Pablo, Part I. [Archival news film]. [O]. Available: https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/187788 Accessed 1 February 2022. [ Links ]

Lippard, LR. 1983. Overlay. Contemporary art and the art of prehistory. New York: Pantheon Books. [ Links ]

Lippard. LR. 2014. Undermining. A wild ride through land use, politics, and art in the changing west. New York: The New Press. [ Links ]

McKee, Y. 2010. Land art in parallax. Media, violence, political ecology, in Nobody's property. Art, land, space, 2000-2010, edited by Kelly Baum. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Art Museum. [ Links ]

Momaday, NS. 1964. The morality of Indian hating. Ramparts Magazine Summer:29-40. [ Links ]

Morris, K. 2019. Shifting grounds. Landscape in contemporary Native American art. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [ Links ]

Native Land Digital. [O]. Available: https://native-land.ca/ Accessed 4 May 2020. [ Links ]

Nemiroff, D, Houle, R & Townsend-Gault, C. 1992. Land, spirit, power. First Nations at the National Gallery of Canada. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada. [ Links ]

Oxendine, LE. 1972. 23 Contemporary Indian artists. Art in America 60(4):58-69. [ Links ]

Scott, EE & Kirsten, S (eds). 2015. Critical landscapes. Art, space, politics. Oakland: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Smith, PC & Warrior, RA. 1996. Like a hurricane. The Indian movement from Alcatraz to Wounded Knee. New York: The New Press. [ Links ]

Smith, SL. 2012. Hippies, Indians, and the fight for Red Power. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

STTLMNT. [O]. Available: https://www.sttlmnt.org/ Accessed 12 October 2020. [ Links ]

Weston, MA. 1996. Native Americans in the news. Images of Indians in the twentieth century press. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. [ Links ]

Wilkins, DE & Stark, HK. 2017. American Indian politics and the American political system.Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [ Links ]

Young, N. 2021. Sonic agency. Canadian art (Spring):38-41. [ Links ]