Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a14

ARTICLES

Defining a sphere of influence: Karel Landman's centenary monument

Brenda SchmahmannI; Vineet ThakurII; Peter ValeIII

IProfessor and SARChI Chair in South African Art and Visual Culture, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. brendas@uj.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8382-2645)

IILecturer in History, Leiden University, Netherlands. v.thakur@hum.leidenuniv.nl (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9273-579X)

IIISenior Research Fellow, Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship, University of Pretoria, South Africa. petercjvale@gmail.com (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0805-9325)

ABSTRACT

Located on a cleared koppie called "Kolrand" in the Eastern Cape, the Karel Landman Monument (KLM) was designed by Gerhard Moerdijk. Its foundation was laid on 16 December 1938, and the monument itself was unveiled a year later. But rather than being a straightforward outgrowth of the celebrations that surrounded the Centenary of the Great Trek, it is revealed that the KLM was mired in controversy about Karel Landman's standing as a "Voortrekker" and the monument's legitimacy. It is argued also that, despite seeming unusual, it deploys visual tropes that can be discerned in other monuments that emanated from the Centenary Trek. Furthermore, it is proposed that its visual language is tied into Afrikaner imaginaries that held sway in the late 1930s. In its inclusion of a globe and its treatment of the trek motif within it, the KLM is underpinned by a conception of South Africa's place in the world that is at odds with a British imperialist vision of the Cape and Egypt as civilising points at either end of a dark hinterland. It would seem instead to be tied into conceptions of the heartland of Africa as an abode in which the white Afrikaner enjoys a God-given predominance and may perhaps even be linked to conceptions of Monomotapa which were an influence on Moerdijk.

Keywords: Gerhard Moerdijk, Karel Landman, monument, Voortrekker, Centenary Trek, Great Trek, Afrikaner nationalism, Volksmoeder, Monomatapa, Afrikaner imaginary

Introduction

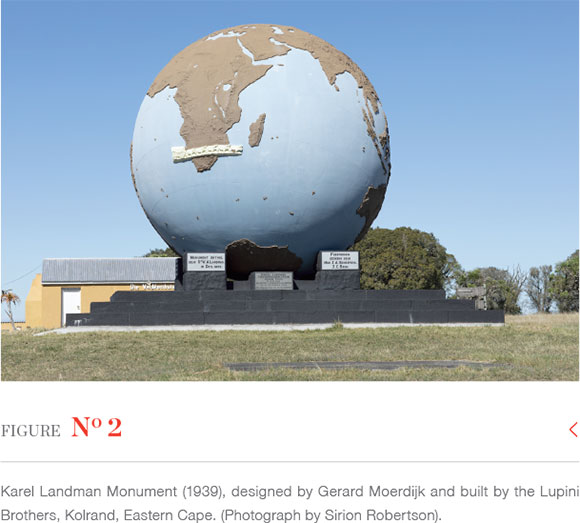

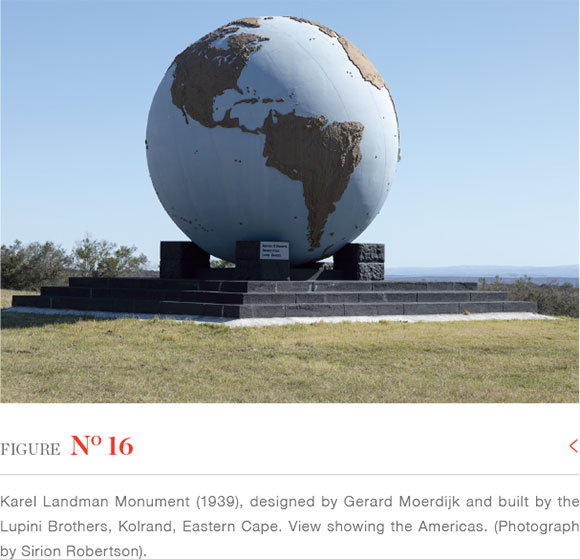

Located deep in the scrub of the Eastern Cape, a near-forgotten monument stands on a cleared koppie called "Kolrand" (Figure 1).1 A globe of the earth made from concrete and steel with a diameter of almost five metres, the monument includes across its front a relief outline of the African continent in grey (Figure 2). Across the southern end of this face - roughly where the Tropic of Capricorn might be found - is an embossed wagon drawn by five pairs of oxen (Figure 3).

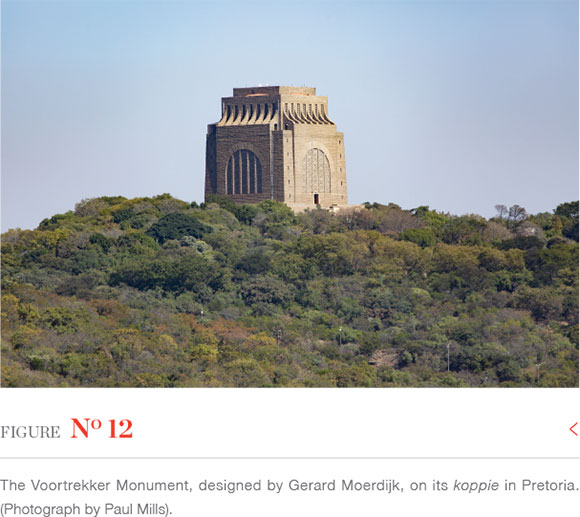

The Karel Landman Monument (KLM), built in 1939, was designed by Gerhard Moerdijk (often written as "Moerdyk"),2 the architect of the Voortrekker Monument as well as other buildings and projects associated with Afrikaner nationalism. Yet, despite the renown of its designer, the KLM is little known. While the topic of a celebratory pamphlet by Marius Swart, Otto Terblanche and Theo Rautenbach (1988) and discussed briefly in an unpublished Master's study of centenary monuments and memorials by Victoria Heunis (2008), it is listed in neither C. van Riet Lowe and B.D. Malan's (1949) The monuments of South Africa, nor J.J. Oberholster´s (1972) The historical monuments of South Africa, for example. Most surprisingly, it is not even mentioned in the key monograph on Moerdijk - Irma Vermeulen's (1999) Man en monument. Die lewe en werk van Gerard Moerdijk.

The KLM is undoubtedly a curiosity. It seems strange to have erected a monument to a Dutch-speaking farmer and Great Trek leader in a corner of the country that had declared its Englishness with imperial vigour and unapologetic confidence. Additionally, there is the matter of the monument's form. At first glance, the KLM may strike one as anomalous. A globe of the earth propped on a pedestal, it seems fantastical and delightful, and with rather more in common with the Big Pineapple on Summerhill Farm just outside of Bathurst3 than the Voortrekker Monument, the Piet Retief Monument that Moerdijk designed for Coega4 and the various other monuments and memorials he designed. Perhaps it was not only its remoteness but also the seeming inconsistency of this monument with Moerdijk's other designs that have been contributing factors in its marginalisation within the discourse. Or perhaps it is simply that its oddity has made it seem too hermetic to be interpreted. In the abundant bush that surrounds it, there are no immediate reference points - certainly none that speak to the idea of the international or provide any other clues about the choice and treatment of subject matter. The only explanation on record is a handwritten note from 1952 in which Valentyn Büchner, who was appointed secretary of the committee established to organise the monument in 1938,5 provides a very brief account of what Moerdijk had in mind:

Symbolism: The globe suggests that this part of the earth, namely South Africa, was made known to the world and made part of the civilized world through the ox-wagon. The trek is the biggest single thing that has contributed to it. This idea [and interpretation] of the monument and the symbolism is that of Mr Gerard Moerdyk.6

But what viewpoints and ideas underpinned such a conception, and how might one explain specifics of the form and iconography of the monument that are not accounted for in this brief comment? For example, why does the trek run on a horizontal axis that excludes the Cape? And how did such a structure happen to be placed where it was, in a remote part of what is now the Eastern Cape province? Our discussion in this article addresses these questions.

We commence with an engagement with the circumstances that led to its commissioning. We reveal that, rather than being an uncomplicated celebration of a trekker hero and a straightforward outgrowth of the celebrations that surrounded the Centenary of the Great trek, the KLM was in fact mired in controversy - both about Karel Landman as an individual and about the legitimacy of a monument to him.7 We then turn our attention to explaining its form and imagery, arguing that, despite it seeming anomalous and strange (and despite contention around Landman's standing as a "Voortrekker"), its visual language was in fact tied into Afrikaner imaginaries that held sway in the late 1930s. In a paper from 1992, Elizabeth Delmont (1992:1) explores how 'the architectural and sculptural vocabulary of the Voortrekker Monument was used to perpetuate and entrench certain central myths about Afrikaner history in order to convey the ideological interests of the group which the monument was intended to serve', and myth-making of this kind is at play in the KLM too. Inserting Landman into the narrative of the Great Trek mythology from which he had been excluded, the KLM simultaneously articulates what Delmont (1992:1-2) identifies as an intrinsic connection made between trekker and land as well as a construct that the various endeavours of the trekkers were divinely sanctioned. But the imagery in the KLM also has further implications, we suggest. In its inclusion of a globe and in the treatment of the trek motif within it, the KLM offers a conception of South Africa's place in the world that is at odds with a British imperialist vision of the Cape and Egypt as civilising points at either end of a dark hinterland. Tied into conceptions of the heartland of Africa as an abode in which the white Afrikaner enjoys a God-given predominance, and to which he or she feels an intrinsic affinity, it may also perhaps be linked to conceptions of Monomotapa, a mysterious kingdom deep in Greater Zimbabwe.

The commissioning and building of the KLM

The cornerstone of the KLM was laid on 16 December 1938, the day Afrikaner nationalists commemorated the Centenary of the so-called "Battle of Blood River" (Figure 4). The original suggestion that some form of local event - and possibly a monument - should be organised to mark the day came from the embryonic National Party at a district meeting of its branch on 2 September 1938. But the initiative to erect a monument was taken by the two nearby Dutch Reformed Church parishes of Alexandria and Paterson. The pathway to the laying of the cornerstone, however, was marked by tension between all concerned, including the two parishes and the National Party.8 It simmered throughout the build-up to the unveiling of the monument, with contention arising about who, firstly, was entitled to pronounce on the shape of the festivities, and then, secondly, on the form of the monument itself.

This friction was set against the immediate backdrop of the national excitement for the Centenary Trek. Nine symbolic commemorative caravans were to converge eventually at the site of a grand monument near Pretoria in the second half of 1938 where a "Voortrekker Monument" was to be erected. The enthusiasm was palpable: the country's Post Office even issued a stamp-series on the Voortrekkers. However, by September it was also plain that none of these caravans would pass through Paterson or Alexandria despite their visiting some 500 centres. The closest any would reach was some 90 kilometres north-west of Paterson. This leg of the journey comprised, inter alia, wagons which carried the names of three leaders - Piet Retief, Louis Trichardt and Hendrik Potgieter. But no wagon carried the name of Karel Landman.

Given the growing sense of national urgency, it is possible that there was a little embarrassment on the part of the burghers of Olifantshoek that they had responded poorly to the initial Afrikaner call to mobilise. But it is also equally probable that they felt anger and resentment that Karel Landman's leadership role had not been recognised and respected by the organisers of the 1938 Centenary Trek. Whatever the case, they drew together with both direction and dispatch to participate in their own way in the Centenary events. At a meeting on 7 September 1938, held at a place midway between Alexandria and Paterson, it was unanimously agreed to continue with the project and to establish the "Olifantshoek Eeufeeskommissie".9But while there was consensus to proceed, the execution of a plan was strewn with local differences.

Despite the fact that the initiative came from the National Party, there was disagreement as to whether or not the festivities - or, indeed, the subsequent erection of a monument - should be directly linked to party politics. Indeed, at one point on 20 September a local branch of the National Party walked away from the Olifantshoek initiative, taking the designated Treasurer with it. At the same time, the council of the Alexandria parish committed itself to support a separate initiative to celebrate and erect a monument to Piet Retief, who had led a separate migration from the eastern parts of the Cape. This parallel initiative to erect a Moerdijk-designed monument at Coega - as the crown flies 70 kilometres west of Kolrand - continued to visit the deliberations.10 The upshot of these events was that the composition of the Commission and its various sub-committees continuously changed as it sought to accommodate, firstly, the competing claims of church and party, and, secondly, contending allegiances and commitments to two commemorative initiatives.

On 26 September, the Commission, having considered various possible locations, visited the 2.5-hectare koppie, which had been offered gratis as a site for the monument. It was well-sited, being accessible as well as, geographically speaking, a central point in the district. Early sketches on the monument were unsatisfactory for they apparently looked like gravestones. Valentyn Büchner then suggested that the monument might comprise a single granite stone onto which a suitable symbolic image might be carved. He offered - to a positive nod from the commission - to discuss the project with Moerdijk, who was his acquaintance through the Witwatersrand Afrikaner circles. Moerdijk initially approved of Büchner's scheme.

Consequently, on 23 November 1938, the Commission agreed to proceed with the erection of a concrete foundation upon which would be placed the giant granite stone, to be quarried in the Boland or Transvaal. Moerdijk too arrived at the Kolrand in late December for an inspection. The visit in high summer was celebratory: some fifty locals were on hand to greet the architect, and the sale of refreshments aimed to boost the monument funds. But the architect delivered disappointing news: it was not practical to transport a giant stone over a great distance, nor to install it, and the monument would have to take another form. Moerdijk then suggested that a globe of the world might be constructed and that an ox-wagon be placed across the face of South Africa. On his recommendation, the Lupini Brothers of Johannesburg were appointed to do the construction.

Of names, and naming

Because names both matter and change with time, it is necessary to point out that in the programme for the laying of the cornerstone on 16 December 1938 the monument-in-the-making was described as the "Karel Landman-Trekkersgedenksteen" (Figure 4).11 Notably, the term "Voortrekker", which was increasingly carrying such great symbolic value in mobilising Afrikaner Nationalism, was not used. Indeed, when the monument itself was unveiled a year later, the terminology was in the same mode. On this occasion, the relevant wording reads, 'Onthulling Karel Landman-Trekkers-Monument'.12

Most South Africans recognise that the telling and re-telling of the story of "the Great Trek" - that is, the 'organised migration of...[white]...farmers from the Cape into the interior of South Africa in the late 1830s' (Saunders & Southey 1998:80) -has involved shameless myth-making. So too has the deployment of the term "Voortrekker". As Marianne Kriel (2021:4) points out, the use of Voortrekker 'was a product of the tentative first mythologisation of the Great Trek by Boer nationalism'. This took place during the 1870s in the South African Republic and the Orange Free State who afforded the emigré farmers the honorific of "Voortrekker" as recognition for both their pioneering spirit and republicanism.

Interestingly, the earliest of these emigrant farmers were from the Cape's eastern frontier. Amongst them was Karel Landman, who was born in Olifantshoek in March 1796. In October 1837, after a successful career as a farmer and at the age of 41, Landman - together with 39 families - left the area. Their caravan (called by the Afrikaans word, trek) of wagons initially moved north, passing through what is today the Free State, arcing eastward across the Drakensberg and ending up in Port Natal. Here, Landman was to become active in the public life of the republic called Natalia, which was created in the name of the émigrés. Its independence was to last only for a short period, 1838 to 1843, before Britain proclaimed it a colony.

Landman's excision from the top rank of emigré leaders in Afrikaner "Voortrekker" mythology in 1938 may seem surprising, given that he was the second-in-command at the clash at Ncome. In this self-styled Battle of Blood River, the emigrant farmers in Natalia battled the AmaZulu in retaliation for the death of another of their leaders. This once fêted victory on 16 December 1838 was said to have been the result of divine intervention, and Landman was amongst the leaders who took the famous Vow to keep the day Holy if they defeated the AmaZulu. Additionally, Landman was regarded as an organiser, and a skilled politician who became the Chairperson of the Volksraad of Natalia. So, what explains the hesitancy to place him in the first rank?

In 1842, as John Laband (2009:139) reveals, Landman had refused to take up arms against the British, when the latter forcefully occupied Natal. He instead retired to a farm in the Midlands. Hence, for the myth makers of the Great Trek, Landman had not completed the journey "to the republican ideal". Their disapproval was palpably evident in the commemorations: all of the front-line trek leaders, barring Landman, were honoured with wagons with their names which crossed the country to commemorate the Centenary. Accordingly, Landman was also not considered to be a fully-fledged "Voortrekker". It was in the context of this displeasure that Olifantshoek too may have been excluded from the 500-odd centres that were visited by the nine ox-wagons - each named for a Voortrekker leader - during the Centenary celebrations.

Monuments emanating from the Centenary Trek

Heunis (2008:37-75) identifies different kinds of monuments that arose in the wake of the 1938 centenary. Apart from some monuments to the South African War, there were in essence two kinds of structures that might be distinguished from each other. On the one hand there were those built to commemorate the Great Trek (that is, key events within it or which celebrate its leaders) while, on the other, there were those more focused on commemorating the "Centenary Trek" - that is, the symbolic trek across South Africa in 1938 rather than the Great Trek itself. Whereas the former were commissioned from architects or designers and built from durable materials, the latter tended to be smaller in scale and rarely involved the work of professionals or even preparatory drawings. In the case of the former, the laying of a commemorative slab formed part of the Centenary celebrations, albeit that they were completed only a year or more later, whereas the latter were often developed from mementoes and traces of the Centenary, such as piles of stones that communities had gathered or preserved traces of imprints of an ox wagon.

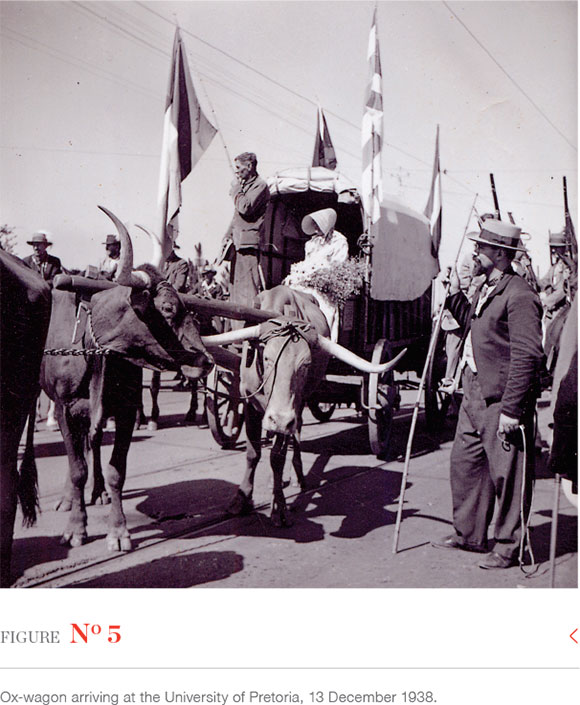

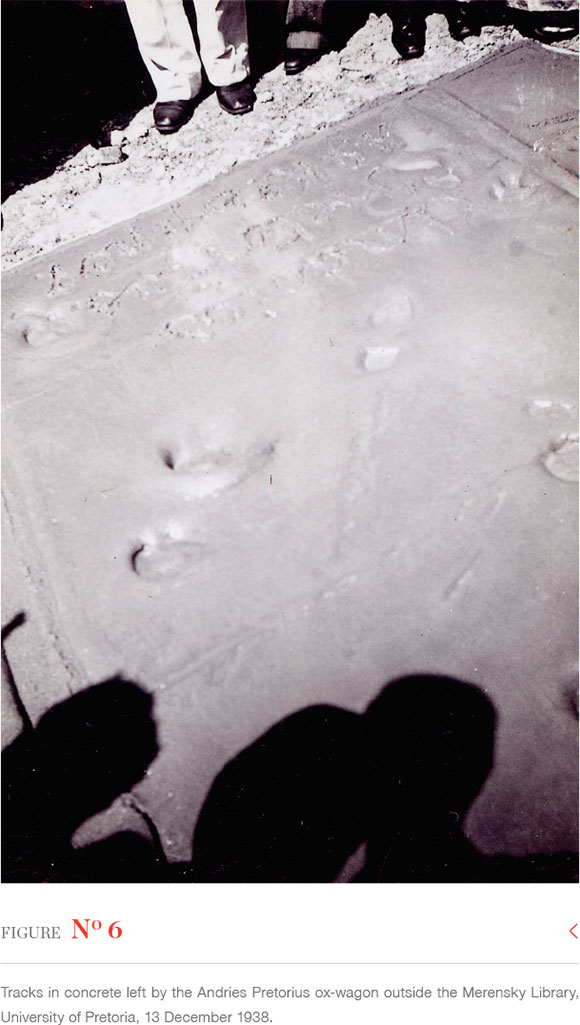

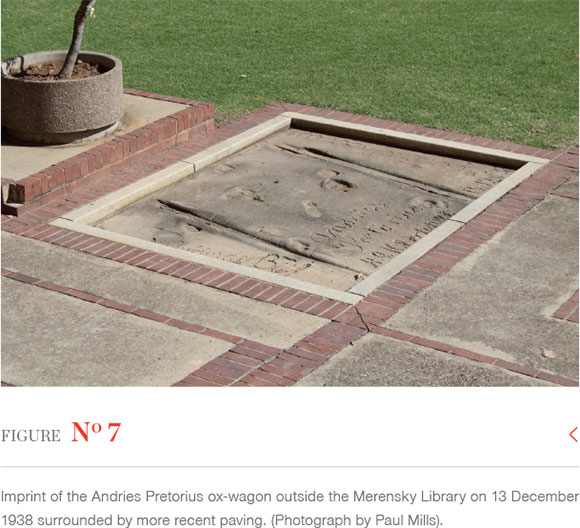

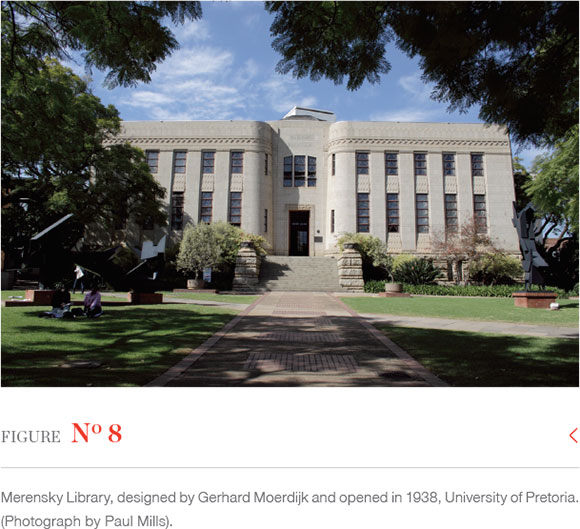

The KLM falls into the first category, as do two other monuments designed by Moerdijk - the Voortrekker Monument and the Piet Retief Monument, which was originally positioned in Coega. Among the numerous examples in the latter category, one might perhaps consider an example that also involved Moerdijk. On 13 December 1938, three days prior to the laying of the foundation stone at the Voortrekker Monument, the Afrikaanse Nasionale Studentebond organised a celebration on the sports field in front of the Old Arts Building at the University of Pretoria. Ox wagons that had begun arriving in Pretoria for the Centenary celebrations were formally welcomed at the university (Figure 5), where Moerdijk was Chair of Council,14 and the Andries Pretorius wagon was invited to imprint its tracks in concrete (Figures 6 and 7). Placed in front of Merensky Library (Figure 8), which Moerdijk had recently completed,15 this concrete slab also included Moerdijk's signature.

A comparison of the KLM with this imprint in front of the Merensky Library underscores the point that monuments to the Great Trek tend to be considerably larger than those commemorating the Centenary. But it also makes clear a further distinction. The visual communication of Great Trek monuments is primarily through what Charles Peirce (1940) would term iconic signs and symbolic signs. The former group tends to include imagery or motifs that work on the basis of resemblance between the motif and that which it represents. The latter stand for concepts or ideas that are being invoked. In contrast, monuments commemorating the Centenary rely predominantly on what Peirce would define as indexical signs for emotive resonance. In other words, in the manner of a footprint or handprint, they operate primarily as physical traces of that which they signify.16 Thus, depending primarily on iconic or symbolic associations, the KLM's incorporation of a representation of an ox wagon traversing South Africa operates differently to the mark or trace of the Andries Pretorius wagon at the University of Pretoria. Whereas the Landman Monument encourages contemplative thought about what an ox wagon traversing a globe of the world might mean, the actual physical trace of an ox wagon makes the 1938 event palpable within the present and - at least for those sympathetic to Afrikaner nationalism - even a wondrous relic of something momentous.17

And yet there is also some commonality between ideas conveyed by the KLM and those indexical traces of the 1938 commemorations. Jennifer Beningfield (2008) has written about how the 1938 celebrations collapsed distinctions between different historical moments. In a context in which the exact routes followed by the original parties of trekkers were only imperfectly recorded and were thus a matter of conjecture, traces from 1938 served in a way as the evidence of events from a century earlier. This curious conflation of past and present, and deployment of evidence of the present to provide proof of the past, was furthered through another evidentiary device deployed extensively during the centenary - that of mapping.

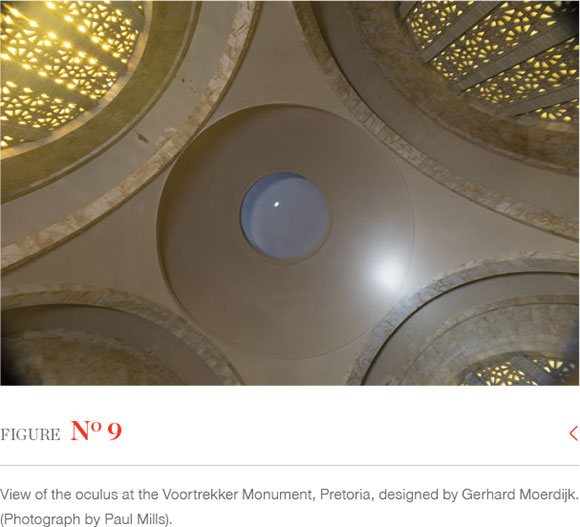

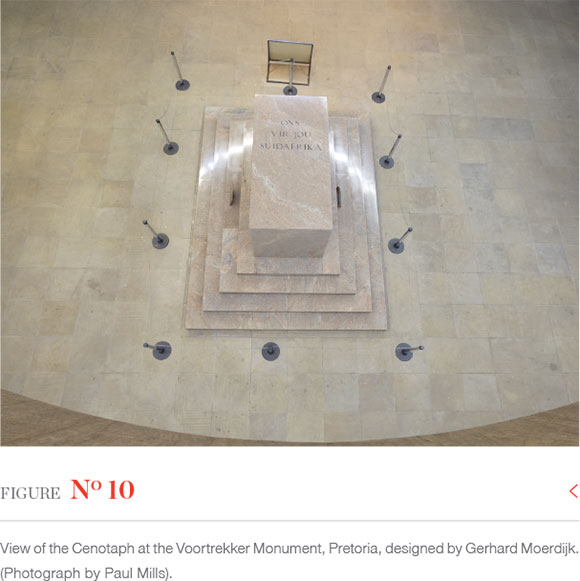

Since the Voortrekkers had themselves left no written or physical footprints of their routes, Beningfield (2008:46) points out that 'a series of maps...that offered clear, "rational" and "scientific" evidence of the invisible paths in the landscape' were produced during the Centenary. This mapping consciousness also informed Moerdijk's architectural sensibility. His initial design of the dome of the Voortrekker Monument (Figure 9) included a relief map (Moerdijk [Sa]:36). He wrote:

The representation is that of the globe, with South Africa at the summit. The idea is one will later represent the map of South Africa against the dome in bas-relief. On such a map, the path along which the Great Trek went will be indicated by a silver thread. This thread would terminate at a small oculus in the dome (Moerdijk [Sa]:36).18

An early drawing reveals that he envisaged extending embellishment to the pendentives, one of which would represent a caravan of ox wagons.19

As is well-known, the oculus was devised in such a way that it would enable the sun to shine directly on the cenotaph (Figure 10), highlighting the words 'Ons vir jou Suid Afrika' at exactly midday on 16 December each year. While neither the decoration of the pendentives nor the map in relief ever materialised, Moerdijk's idea found form in the KLM where an ox wagon and a globe of the world is rendered in relief (Beningfield 2008:64).

The KLM in the context of Moerdijk's oeuvre

In order to analyse the KLM further, especially its nationalist and internationalist imaginaries, brief discussion about its designer is necessary. In the 1910s, when Gerard Moerdijk trained to be an architect, the local profession was under the influence of Cecil Rhodes' close associate, Herbert Baker. This was an historical era in which the Empire was moulding South Africa in its own shape. Just as in the political sphere, where "Milner's Kindergarten" played a pivotal role, "Baker's Boys" were redefining the South African approach to architecture. But while inspired by Baker, Moerdijk felt an outsider to the English-dominated profession. This sense of alienation from a British imperialist architecture was compounded by his personal history. His family had been in a concentration camp during the South African War. In 1917, he married Sylvia Heneriette Pirow, a National Party member and the sister of Oswald Pirow, who would become a prominent figure in Nationalist circles and, in 1940, founder of the far-right "New Order for South Africa". In 1920 Moerdijk joined the Afrikaner Broederbond and became a strong advocate for the development of a distinct Afrikaner sensibility in the form of "volkseie argitektuur".

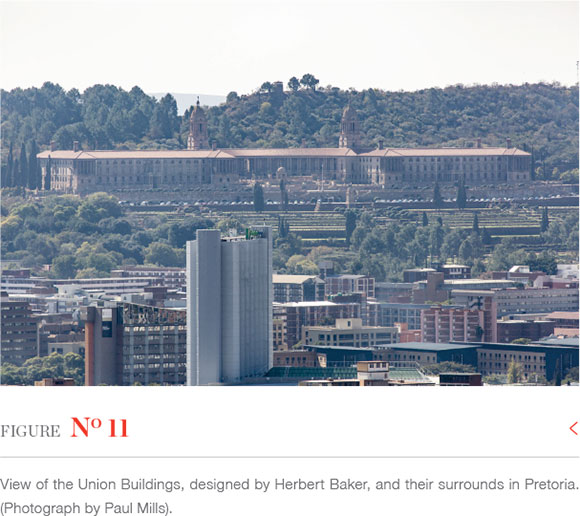

Drawing a comparison between Baker's Union Buildings (Figure 11) and Moerdijk's Voortrekker Monument (Figure 12) which face each other on two koppies in Pretoria, Jooste observes that the former is 'soft centred' and horizontal, elegant and reticent. Symbolising 'a quietly confident system of government', it displays genteel civilisational progress (Glancey 1998:30 cited by Jooste 2001:77). The Voortrekker Monument, in contrast, stands stoutly like a block, expressing 'force, anger, struggle, dominance, subjugation and kragdadigheid' (Jooste 2001:77). Moerdijk repudiates classicism associated with Baker's architecture and British imperialist understandings that underpinned it. Drawing on Modernism and Art Deco in the 1930s, Moerdijk's architecture looked to more 'authentic sources' - those from Great Zimbabwe, for instance - to make claims for an Afrikaner nationalist architecture (Freschi 2015:[Sp]). Jooste (2001:82) suggests that Moerdijk'a monuments, which reflect the toil and the struggle of the Afrikaners, tend to be 'dark, depressing places devoid of humour and life'.

When one considers general features of Moerdijk's architecture, the KLM may at first seem strikingly odd. We have shown how the design was partly a result of logistical concerns; however, replacing a grey and broody granite block with a globe alters its colour palette drastically. Moerdijk's monuments are usually staged as a type of stalwart (and perhaps even dystopian) resilience. However, a mix of blue, brown and, when the sun is shining, even golden luminosity, in addition to the "globe" symbolism, unmoor the KLM from the intensity of its Afrikaner context. Rather than the hard, gritty sense of resistance that is Moerdijk's architectural staple, it conveys a hopeful spirit of freedom and exploration.

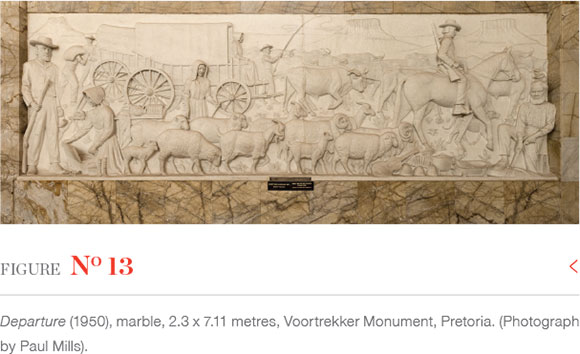

The notion of Afrikaners as pioneers is clearly visible in the ox-wagon that traverses from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, and their fierce independence appears in the figure of the ox-wagon driver, who is evidently a woman (Figure 3). In some sense this figure has commonality with the woman seated on an ox-wagon in the scene representing "Departure" in the frieze at the Voortrekker Monument (Figure 13). But at the same time, however, this image is divested of all anecdotal detail so that the scene does not represent any particular moment in the Great Trek narrative but rather functions as a symbol for all the Great Trek departures - that of Karel Landman and others. The woman is in fact a generic image of Voortrekker womanhood - indeed, a so-called Volksmoeder who had emerged as a key ideal within Afrikaner nationalist discourse. While its changing iterations and contradictions are too complex to unpack in any depth here, one broad point might be noted. Deborah Gaitskell and Elaine Unterhalter (1989:62) identify a change from a conception of the Volksmoeder as simply saintly and stoical in suffering in the years immediately following the South African War to a conception of motherhood as 'far more active and mobilising' - albeit in terms of her capacity to develop Afrikaner nationalist values in the home rather than in a public arena. Driving the ox-wagon, the home, across the wilderness in the KLM, the figure thus encompasses the idea of Afrikaner womanhood as a powerful domestic force.

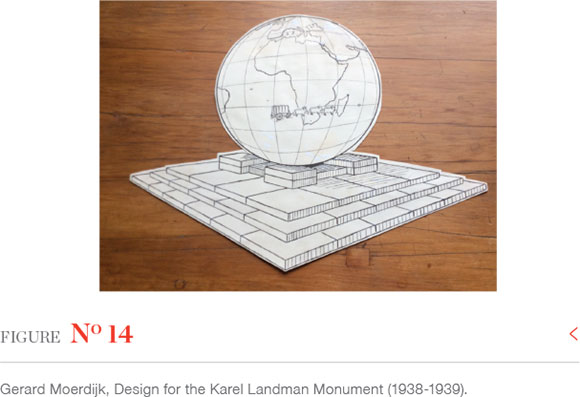

The only existent sketch of the monument by Moerdijk (Figure 14) includes the outline of a wagon and three pairs of oxen, but no figure. It is thus possible that the particularities of the rendition was without his immediate input. Nonetheless, Moerdijk would likely have been in favour of a woman featuring here. Writing about the design and symbolism of the Voortrekker Monument, he emphasises the centrality of women to the trek, thus:

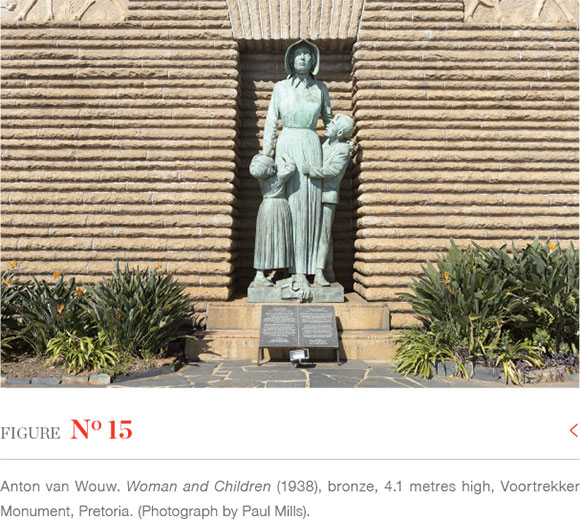

The Voortrekker woman broke all ties down there in the Cape; she pushed aside all comfort and prosperity, she moved, ready to suffer and endure conflict, to nurse the sick, to weep for the dead, to give life to future generations and to raise her sons and daughters in the true tradition of their ancestors on the Trek. It was the Voortrekker woman and the Voortrekker family who made the Great Trek possible. Without them, the Trek would have culminated in an explorative expedition and the possible establishment of an outpost or hunting camp, nothing more (Moerdijk [Sa]:33).

Indeed, for him, women are the force that maintains tradition, upholds the sanctity of the volk and defends it against miscegenation. Commenting on the keynote sculpture by Anton van Wouw of a mother and two children at the Voortrekker Monument (Figure 15), he remarked: 'The Voortrekker woman had to endure many hardships. She had to care for and raise the future generation. Indeed, she did this, and established and maintained the white race here. The Voortrekker mother at the Monument Immediately raises confidence that she can do it' (Moerdijk [Sa]:55). Given these sentiments, it is unsurprising that his own architecture career is bookended by two key women's monuments - the Women's Monument in Klerksdorp (1921) and the Memorial to Anjie Scheepers in Ladybrand (completed posthumously in 1963).

The KLM in the context of Afrikaner nationalist imaginaries

A more speculative reading of the KLM will find something else decidedly unusual. The ox-wagon cuts across southern Africa, from the south Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, instead of starting out in the Cape (Figure 3). In fact, it excludes the Cape entirely in its visual depiction of the trek. Why so?

To understand this, one might turn to what Peter Merrington (2004) terms the 'staggered orientalism' of the 'Cape-to-Cairo' imagination of South Africa. Cape-to-Cairo refers literally to a telegraph and railway lines that Rhodes wanted to build. But metaphorically it refers to the imperialist ambition to unite the African continent under British control. Given how much Rhodes was personally invested in it, Cape-to-Cairo is often depicted in the image of the Rhodes Colossus. But Merrington (2004) suggests another reading: Cape-to-Cairo was the key imaginative template of what South Africa would eventually become. He finds a profusion of images -both sublime and ridiculous - whose cumulative effect turns the Cape-to-Cairo idea into South Africa's dominant public imaginary of itself. In this, the Cape and Cairo are not only opposite tips on the continent but also become two end points of civilisation. Furthermore, the Cape is not just another place in Africa but rather outside of it, in the European Mediterranean. Often advertised as the "Venice of the South Atlantic" and the "Naples of the South", the Cape is reimagined as a Mediterranean paradise. Indeed, an archetypical proponent of this view, as Merrington (2004:70) argues, was Rhodes' protégé and architect, Herbert Baker.

The prolific use of the Mediterranean frame of reference for the Cape serves one key function: it places the Cape, both metaphorically as well as imaginatively, within Europe. It is connected to Cairo or Egypt at the other end of the Mediterranean. But Africa - a continent without any historical presence in Hegelian tropology - is written out entirely. Hegel allows for Egypt to be included in world history as an exception, for Egypt lay at the origins of civilisation (Merrington 2004). Thus Cape-to-Cairo, with the Rhodes colossus straddling across it, involved a happy jump from the origins of civilisation to its end, in other words, Europe. This 'staggered orientalism', in which Africa is present only as a dark absence (or as the middle passage), and with Egypt at one end of the civilisation and the Cape-as-Mediterranean at the other, constituted the chief self-imaginary of South Africa (Merrington 2004). Merrington (2004) argued that this was forged as an identity claim around the birth of the Union of South Africa, with an eye towards South Africa's own outward imperial imagination.

Seen in this context, we contend below, the KLM gestures towards an alternative register of a South African imaginary. Temporally, it fructifies in the late-1920s and early-1930s as Afrikaners develop not only a strong sense of national identity with the National Party in power, but also sharpen their own version of an imperial ideology that is distinct from the English-imperial Cape-to-Cairo vision.

Even though Afrikaners were defeated in the Boer War, they remained opposed to South Africa being part of the British imperial system. While Smuts (who became more English than the English in the view of his Afrikaner opponents) advocated stronger ties with Britain, Afrikaner nationalists worked towards greater autonomy, if not full independence. In his first Imperial Conference, J.B.M. Hertzog, prime minister, played a crucial role in the Balfour Declaration of 1926, which declared that the Dominions including South Africa were 'equal in status' to Britain, and the Westminster Statute of 1931 confirmed it through legislative approval. Although initially in a muted form, this particular development drew the South African government into the arena of making foreign policy - the urgency of which was increased by the gathering of war clouds in Europe in the mid- and late-1930s (Scholtz 1953:291). It brought to the fore - both philosophically and in policy terms - the imaginings of what the international could mean for an increasingly restless Afrikaner community. Here, Afrikaner visions of the international differed significantly from the British-inclined South Africans. The Afrikaners did not concern themselves with the imperial burdens of the British Empire. While Smuts retained great interest in British colonies, the National Party leaders did not (van Wyk 2004). Within the African continent, Afrikaner imperial aims were considerably different from the English. Although agreeing with Smuts' invocations of Greater South Africa (Hyam & Henshaw 2003), Pirow, then the Minister of Defence and Moerdijk's brother-in-law, wrote that the Union was interested in Africa south of the equator, excluding French possessions, with only one purpose in mind: unifying whites. The latter, Pirow argued, was essential to save African whites south of the equator (Pirow 1937). It is a distinct vision - one that does not identify with the Cape-to-Cairo imperial project but instead advances its own limited but nonetheless imperialist vision of Africa's white heartland.20 The Afrikaner imperial gaze centres Africa's white heartland instead of elevating Africa's marginal frontiers as civilisational nodes. The English vision is one of escaping Africa altogether - or ruling it from afar (in metaphorical and literal sense) - while the Afrikaner vision elevates mainland Africa as its primary and primal field of imperial play.

The KLM plays on this theme of the Afrikaner imperial project. The globe may be the object, but the tilt of its placing, for any visitor, makes it very clear what lies at the centre of this global vision: Africa south of the equator. Egypt is scripted out of focus, and the Cape is erased in the most central motif on the globe - the trek. Africa is flattened of its people, save the lone Afrikaner woman driving the ox-wagon - thus a wide land open for pioneering efforts. The idea is to not only declare Afrikaners authoritatively as African, unlike the English who are always trying to escape it in Cape-to-Cairo fashion, but also as the only Africans worthy of civilised status. African heartland is the wide territorial space on which Afrikaners chart their destiny.

Much of the force of the Great Trek mythology depended on the idea that the trekkers were entering virgin terrain. Rather than recognising the land as in fact already occupied, the terra nullius concept pervades Great Trek discourse (see Moerdijk [Sa]:33). Conceptualised as a blank canvas, land is depicted as a purely natural wilderness awaiting the civilising force of the trekkers. Likewise, the KLM represents the world only through natural terrain - mountains, valleys and rivers. In fact, the emphasis only on nature extends to the entire world rather than just Africa (Figure 16). It is as if the lone ox-wagon depicted traversing this natural terrain was a formative force within a yet-to-be occupied world, from the beginnings of time - almost as if it was set into motion by God as part of the creation of the world.

Some of this may be to do with the effects of concrete. Delmont (1992) observes that the foundational myth in Afrikaner nationalism of the Voortrekkers as having an intrinsic connection to the soil found expression in the Voortrekker Monument. This idea is also at play in the KLM through the deployment of concrete in such a way that it conveys the substance and tactility of mountains and valleys. But concrete - the substrate featuring in mementoes of the Centenary such as the Andries Pretorius wagon imprint discussed above - is also a strangely paradoxical medium. While concrete is associated with technology and thus modernity and contemporary civilisation, imprints of an ox-wagon in the medium invoke a sense of fossilised remains of a distant past (Figures 6-7). As Beningfield (2008:50) observes: 'The edges of the panels were set flush with the earth so that the surfaces of ground and inscribed concrete are contiguous. This proximity gives the panels the status of primitive artefacts, or fossilised remains of modernity which are presented as natural objects'. Similarly, the markings of land on the globe in the KLM (see Figure 3) have the quality of petroglyphs. Carrying marks that are associated with an archaeological discovery from the distant past, the substrate here assumes the status of evidence.

The ox-wagon starts in the South Atlantic, somewhere in the hard landscape of today's Namibia, and traverses southern Africa. In this Atlantic-to-Indian Oceanic imagery of the monument, might one find another destination? A key aspect of Dutch/Afrikaner historical imagination on the continent has always been about Monomotapa, a kingdom somewhere deep in Greater Zimbabwe, first revealed to the Dutch by a Portuguese official working in Goa. It was said to hold immense riches, the source of King Solomon's Mines (fictionalised by the Victorian novelist, Ryder Haggard), and remained a place of deep fascination for the Dutch colonisers from the seventeenth century onwards. Under the belief that this Kingdom's gold and riches would make the colony not only self-sustaining but also prosperous, the first Dutch treks into the African mainland were indeed to find Monomotapa. Some even reached the Indian Ocean in their futile search for this utopia (Crompton 2015). In fact, it was something that also fascinated Moerdijk. In 1929, Moerdijk had travelled with the Afrikaner cultural figure, Gustav Preller, to Greater Zimbabwe in search of Monomotapa and reported on his findings after his return. It was following this visit that Moerdijk's interest in Africa had deepened and that he had started using motifs and symbols with African associations. The ox-wagon, and its journey into southwest Africa, allows us to speculate another end point of this trek - to reach Monomotapa, an African utopia. This utopian vision at the heart of the KLM is what also makes it stand out visually and symbolically in Moerdijk's oeuvre.

Conclusion

Alexandria and Paterson, and in particular their Dutch Reformed Church parishes, were custodians of the site of the KLM until 2012, when ownership passed to Die Erfenisstigting, a private-sector organisation devoted to the recovery and maintenance of Afrikaner heritage. The early business of developing the site and managing the KLM was initially conducted without a legal framework, but in the mid-1960s a memorandum of formal understanding was reached. In these years, too, funds were raised to build a hall on the site. The record of these early years shows a scrupulous determination to keep alive the memory of Karel Landman and build unity within - and between - the two communities.21 These goals were reinforced by the support of cultural institutions which prospered after the Centenary Trek. For example, the Voortrekker Youth Movement, which was founded in 1913, was - and remains - closely tied to activities at Kolrand. In addition, there was support - often in kind - from the local boerevereningings. 22 The linkage between cultural memory and the place was always marked on 16 December - the traditional Day of the Vow.

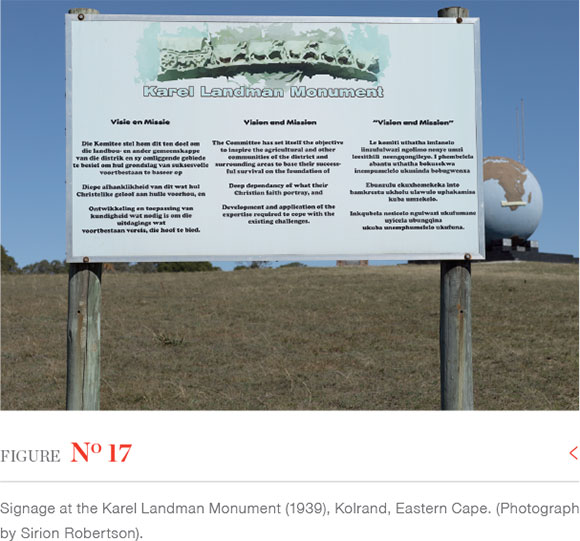

Unsurprisingly, however, interest in volksfees23 occasions slowly tapered off over the decades. While the gathering on 16 December 2019 (just prior to the Covid pandemic) drew some 350 people to the site to listen to a range of speakers, this may have had much to do with a refurbishment and reconstruction of the globe, sponsored by the Rupert Foundation, that had taken place that year.24 As with the Voortrekker Monument and the Taal Monument outside of Paarl, there have been efforts to configure the site of the KLM in such a way that it is accessible to a wider group of people than its original stakeholders. For example, it includes signage in not only Afrikaans but also English and isiXhosa (Figure 17). But as with those larger and better-known Afrikaner nationalist monuments, it sits somewhat uneasily in a contemporary South Africa where the values and beliefs which shaped it are at odds with an official rhetoric of emancipation (and nationalism) which are told through monuments built subsequent to 1994.

As mythologies surrounding the trek of Boers to the hinterland enjoy less and less purchase, the KLM's capacity to inspire devotion to a common cause is in inevitable decline. But the KLM is not a purposeless monument in our present context. It is didactically rich. As a work informed by a 1930s Afrikaner imaginary as well as the politics of its time, it has significant potential to enlighten visitors about the process of myth-making through monuments. Invoking a variety of associative ideas that enjoyed currency when it was made, the KLM attests also to the ways in which histories are shaped not simply by what is purported to have happened but also what - and who - communities seek to remember or forget.

Acknowledgements

Brenda Schmahmann's contribution to this article was made possible through generous financial support from the National Research Foundation (NRF). Please note, however, that any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed here are those of the authors, and the NRF accepts no liability in this regard. Peter Vale is grateful to Amédée Büchner for access to his archive and for many long and interesting conversations on the Karel Landman Monument. Marie Greyvenstein was a great help, as were Riana and Gerhard Heyneke.

Notes

1 . This name is sometime written as "Kol Rand" or "Kol-rand".

2 . The Afrikaans version of his name - Moerdyk - is often used in discourse about his work. We have elected to use the original Dutch spelling that he himself always used.

3 . Built in 1971, this structure in the form of a pineapple and made from metal and fibreglass. It is over 16 metres in height and is comprised of three storeys.

4 . Completed in 1939, at the same time as the KLM, the monument was moved to Gqeberha (then Port Elizabeth) in 1975 (see Heunis 2008:59-60).

5 . The handwritten minutes of the first meeting indicate that he was secretary for a local branch of the National Party.

6 . Our translation from the original Afrikaans.

7 . Our account of the commissioning of the monument is indebted to typed and undated notes by Valentyn Büchner in the Karel Landman archive.

8 . We know this from the several pages of notes compiled by Swiss-born Yvonne Büchner, who was married to Valentyn Büchner.

9 . Oliefantshoek Centenary Committee.

10 . For background on the Coega initiative, see Heunis (2008:59-60).

11 . The literal English translation is "Karel Landman Trekkers Memorial Stone".

12 . "Unveiling...[of]...Karel Landman Trekkers Monument" in English.

13 . E-mail communication from Socio-linguist, Mariana Kriel, to Peter Vale, 16 September 2021.

14 . He served in this role from October 1935 until June 1942.

15 . See Fisher (1998) for a discussion of the Merensky Library.

16 . See Peirce (1940), where 'Logic as Semiotic' is included in a compilation. The essay was authored about two decades earlier.

17 . Notably, during the 150th anniversary celebrations of the Great Trek in 1988, the festivities at Kolhoek included the symbolic driving of a wagon drawn by oxen across a cement base which is positioned in front of the globe.

18 . This translation is from the original Afrikaans, as are other comments by Moerdijk quoted in this article.

19 . We thank Elizabeth Rankin for showing us a photograph of this drawing that she had found in the Moerdijk archive at the University of Pretoria when doing research towards the two volumes on the Voortrekker Monument frieze she co-authored with Rolf Schneider (see Rankin & Schneider 2020).

20 . Vermeulen (1999:126) indicates that Sylva Moerdijk broke all ties with her brother when, in 1940, he broke away from the newly constituted Herenigde Nasionale Party to form his self-styled "New Order for South Africa" sympathetic to fascism. Gerard Moerdijk, however continued to maintain a friendship with his brother-in-law behind her back.

21 . For an account of these developments, see Swart, Terblanche and Rautenbach (1988).

22 . Farmer's associations.

23 . Greater attention should be given to the significance of the 'volksfees' to the development of Afrikaner Nationalism. A helpful place to begin with this would be with Grobbelaar and Kapp (1977).

24 . The R80 000 spent on this refurbishment was the single largest sum spent on the KLM (confirmed in a telephone call with board member of the Die Erfenisstigting, Pieter Duvenhage, 23 October 2021).

References

Beningfield, J. 2008. The frightened land: Land, landscape and politics in South Africa in the twentieth century. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Crompton, H. 2015. The side of the sun at noon. Johannesburg: Jacana. [ Links ]

Delmont, E. 1992. The Voortrekker Monument: monolith to myth. Paper presented at the History Workshop on Myths - Monuments - Museums: New Premises? 16-18 July, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Fisher, R. 1998. The Native Heart: The Architecture of the University of Pretoria Campus, in Blank: architecture, apartheid and after, edited by H Judin and I Vladislavic. Rotterdam: NAI Publishers:221-236. [ Links ]

Freschi, F. 2015. The Imaginary of 'Africanness' in South African Architecture. [O]. Available: https://www.architectural-review.com/today/the-imaginary-of-africanness-in-south-african-architecture Accessed 12 July 2022. [ Links ]

Gaitsekell, E & Unterhalter, E. 1989. Mothers of the nation: A comparative analysis of nation, race and motherhood in Afrikaner nationalism and the African National Congress, in Woman - Nation - State, edited by N Yuval-Davis and F Anthais. New York: St. Martin's Press:58-78. [ Links ]

Glancey, J. 1998. Twentieth century architecture - the structures that shaped the century. London: Carlton Books. [ Links ]

Grobbelaar, PW & Kapp, PH. 1975. Die Afrikaner en sy kultuur. Deel III. Ons volksfeeste. Kaapstad: Tafelberg-Uitgewers. [ Links ]

Grundlingh. A & Sapire, H. 1989. From feverish festival to repetitive ritual: The changing firtunes of Great Trek mythology in an industrializing South Africa, 1938-1988. South African Historical Journal 21(1):19-38. DOI: 10.1080/02582478908671645 [ Links ]

Heunis, V. 2008. Monuments en gedenktekens opgerig tydens die dimboliese ossewatrek en voortrekkereeufees, 1939. MA dissertation, University of Pretoria, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Hyam, R & Henshaw, P. 2003. The lion and the springbok. Cambridge: CUP. [ Links ]

Jooste, JK. 2001. An appraisal of selected examples of Gerhard Moerdijk's work (1890 1958). South African Journal of Art History 15(1):68-84. [ Links ]

Kriel, M. 2021. Boere into Boere (farmers into Boers): The so-called great trek and the rise of Boer nationalism. Nations and Nationalism 27(4): 1198-1212. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12760 [ Links ]

Laband, J. 2009. Historical dictionary of the Zulu Wars. Lanham, Maryland, Toronto & Oxford: The Scarecrow Press. [ Links ]

Merrington, P. 2004. A staggered Orientalism: The Cape-to-Cairo imaginary, in South Africa in the Global Imaginary, edited by L de Kock, L Bethlehem and S Laden. Pretoria: University of South Africa Press:57-93. [ Links ]

Moerdijk, G. [Sa]. Ontwerp en simboliek van die Voortrekkermonument, in Die Voortrekkermonument: Amptelike gids. Pretoria: Voortrekker Monument:31-39. [ Links ]

Moerdijk, G. [Sa]. Beeldhou- en bouwerk, in Die Voortrekkermonument: Amptelike gids. Pretoria: Voortrekker Monument:54-60. [ Links ]

Oberholster, JJ. 1972. The historical monuments of South Africa. Stellenbosch: Rembrandt van Rijn Foundation for Culture. [ Links ]

Olivier, PL. 1952. Ons gemeentelike feesalbum. Kaapstad en Pretoria: N.G. Kerk-Uitgewers van S.A. [ Links ]

Peirce, C. 1940. Logic as semiotic: The theory of signs, in Philosophical writings of Peirce, edited and introduced by J Buchler. New York: Dover Publications:98-119. [ Links ]

Pirow, O. 1937. How far is the Union interested in the continent of Africa? Journal of the Royal African Society 36(144):317-320. [ Links ]

Rankin, E. & Schneider, R. 2020. From memory to marble: The historical frieze of the Voortrekker Monument. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Saunders, C & Southey, N. 1991. A dictionary of South African history. Cape Town: David Philip. [ Links ]

Scholtz, GD. 1954. Suid-Afrika en die Wêreldpolitiek 1652-1952. Johannesburg: Voortrekkerpers. [ Links ]

Swart, M, Terblanche, O & Rautenbach, T. 1988. Die Karel Landman Voortrekkermonument 1938-1988. Pamphlet. [ Links ]

Van Riet Lowe, C & Malan, BD. 1948. The monuments of South Africa. Johannesburg: The Government Printer. [ Links ]

Van Wyk, AJ. 2004. Eric Louw: Pioneer diplomat 1925-1937, in History of the South African Department of Foreign Affairs, edited by T Wheeler. Johannesburg: SAIIA:15-33. [ Links ]

Vermeulen, I. 1999. Man en monument. Die lewe en werk van Gerard Moedijk. Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik. [ Links ]