Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a11

ARTICLES

[Un]performing voice: Simnikiwe Buhlungu/Euridice Zaituna Kala

Katja Gentric

Postdoctoral Fellow, Art History and Image Studies, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. ge.katja@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Two unspectacular interventions, performed in central Johannesburg by Simnikiwe Buhlungu and Euridice Zaituna Kala, evidence the performativity of voice in public space. Addressing the unheard in contemporary society, they operate a shift in the way language is put to use (Cassin 2018). In paradoxical reciprocity, the action of [un]hearing comes to signify a fine-tuned form of informed and involved listening capable of bringing to the fore that which ordinarily goes by unheard or remains stifled. An "accented" way of speaking for example is inflected, shows situatedness, indicates individuated thought patterns (Coetzee 2013). This form of speech carries the legacy of historical exchange between languages and the power relations involved. It bears recognition of the multiple languages involved in the totality of any act of speech. Given current global concerns, it seems indispensable to caution that language identity cuts two ways: it is simultaneously a marker of belonging and a means of singling out those who do not belong. Side-stepping identity-politics, protesting discriminations based on language proficiency, the two interventions suggest self-transforming labour where the reader or listener may potentially perform an activist interruption of the [un]heard.

Keywords: Euridice Kala, Simmnikiwe Buhlungu, accentedness, speech situation, mining compounds, commuter transport in Johannesburg.

Consider two instances of [un]heardness

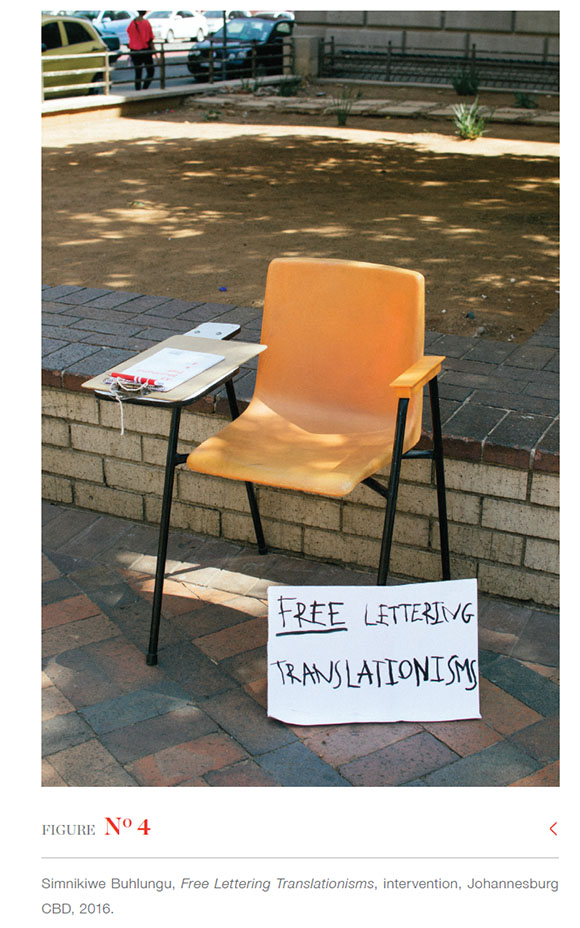

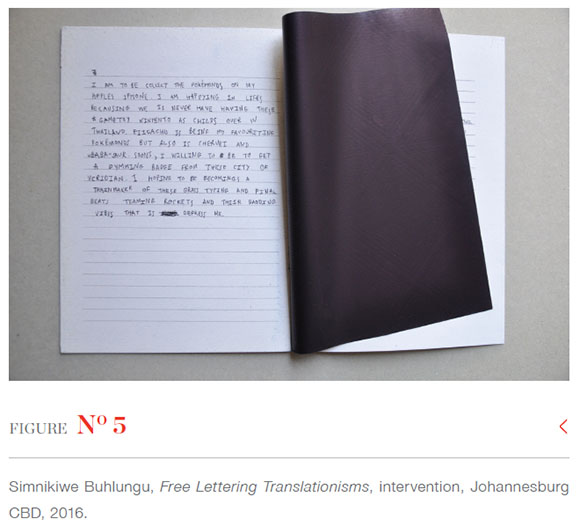

One: The title FREE LETTERING TRANSLATIONISMS (Figures 1 and 5) is handwritten in block capitals across the cover of a few pages bound by two staples. The back of the booklet reads: '©2016 Simnikiwe Buhlungu, Mark Pezinger Verlag Johannesyburg'.1 These pages are only one instant in a process, which began in Johannesburg CBD2 (Figure 4) in 2016 and which anticipates its denouement in the response it would draw forth in the reader.

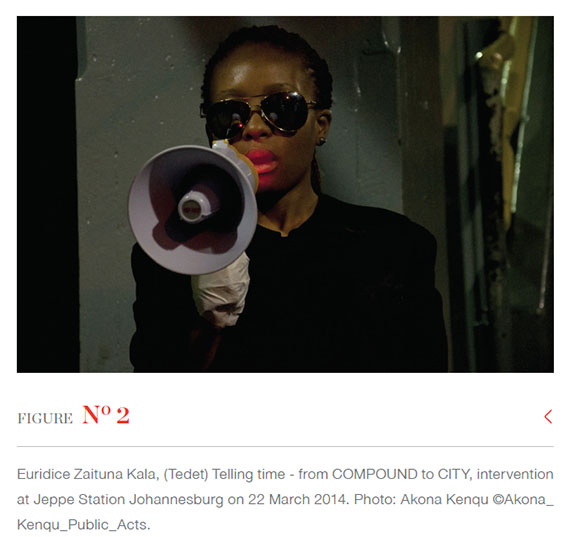

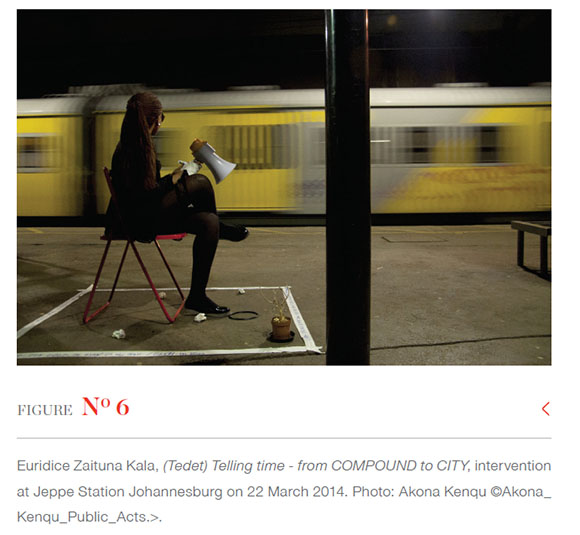

Two: At 4 a.m. on 22 March 2014 at Jeppe station, bordering central Johannesburg, Euridice Zaituna Kala speaks into a megaphone - inserting her sonic presence into the ebb and flow of a hurrying, unspeaking crowd that seems to navigate by some inaudible and unwritable code, which will crystallise only when interrupted by a foreign presence, Kala's, in this case (Figures 2 and 6).

In both these instances, an on-going flux of events is punctuated by interruption (taking the form of an artist's book by Buhlungu, or a sonic intervention by Kala). Both are based on language, more precisely translation (Ost 2009) or, rather, nonstandard ways of speaking and thinking - not foreign, but accented (Coetzee 2013). Starting from here this text will explore the performativity of voice in public space.

The first of the two interventions in public space manifests in the form of a book, apparently void of sound. It offers the possibility for the potential reader to reconstruct the words in his/her mind, thus imagining the way these words would be pronounced. Voice is present in virtual form only. The second intervention actually uses voice, the artist's own voice, amplified by a megaphone. In each instance the process stems from far-reaching historical legacy and extends well beyond the public's encounter with the intervention. Historical perspective is key to positioning these works. In order to apprehend the multiple vectors mobilised within this perspective they are positioned amongst other artistic interventions.

In the contemporary South African situation several artists work on the feeling of oppression or the memory of it. The chosen examples perform instances where voice is stifled: Churchill Madikida, Kemang Wa Lehulere and Lerato Shadi. Drawing artists from remote geographical locations into the dialogue, namely Violaine Lochu, Bouchra Khalili and Lawrence Abu Hamdan, it turns out that questioning accent cuts two ways: it is simultaneously a marker of belonging and a means of singling out those who do not belong.

Buhlungu and Kala's interventions provide an occasion for developing an ear for the multitude of accents. Hearing, or rather [un]hearing comes to signify a fine-tuned form of informed and involved listening, capable of bringing that to the fore which far too often goes by unheard or remains stifled: the unheard in contemporary society within its historical perspective. Even though the two artists use inverse strategies, they use the methods of an artist, inserting themselves, their bodily presence and their actions, within an on-going flux of events. Both operate a shift in the way language is put to use.

On the improbable possibility of [un]ravelling language, politics and history

Both abovementioned instances are strategically placed in Johannesburg and thus are inscribed within South Africa's unfolding socio-linguistic and political history under the token of the changeover from apartheid to hardcore neo-liberal democracy. Each intervention points to particular details of the interwoven and tangled vectors in this constellation, amongst others, one of the most notable changes implemented by the transitional government after the first elections by universal suffrage in 1994: the recognition of 11 official languages plus sign language. This decision was taken in reaction to language politics before and under apartheid when the majority of the languages spoken in South Africa were disenfranchised by legislation (Ndebele 1991 [1987]). It also reflects political parties' self-interest during the negotiated transition (Alexander, 2011). The cohabitation of 11 official languages implies that language skills will remain key in education in South Africa. This is even more so seeing that the memory of the 1976 student protests against language policies imposed by the Bantu Education Act and their lethal consequences, are all but forgotten (Gentric 2016). The renewed student protests surfacing since 2015 have brought these questions to the fore once again. Student activists for free quality education call, amongst other things, for an education system that recognises cultural specificity, making a decisive step towards amending discriminations based on language proficiency. South African students aim to make a significant contribution to decolonial ways of knowledge production.

Colonial conquest implemented European languages as the dominant idiom of exchange. Functioning in complete lack of reciprocity or mutuality, the translator's task was to glean information form the inhabitants, translate it for the coloniser (Coetzee 2013:79-95). This form of translation had the effect of silencing and effacing the idiom wherein the utterance had been expressed. Today South African language activists and scholars grapple with the intricacies of dealing with the conscience of this first idiom's disappearance. Nostalgia for this loss is complicated for several reasons: it seems impossible to speak about language loss without perpetuating the silencing effect by inserting your own voice in the stead of that of the first speaker (Coetzee 2013:97-109). Dealing with this disappearance is further complicated by changing ideologies underlying language policies under different dispensations.

As exchanges between coloniser and colonised evolved, the administration of artificially invented ethnicity gave rise to the fiction of clean-cut, "pure",3 supposedly "primordial" languages demarcating the South African territory. Sinfree Makoni (1998:242-87) exposes the political intentions underpinning the identification of one regional variety as a distinct language within speech forms that should rather be seen as continuous. The ambition to standardise for the purposes of demarcating linguistic boundaries often included passing judgement about the society under scrutiny. Under grand apartheid the myth that languages were mutually exclusive categories was upheld as a "natural" founding principle. Apartheid legislation motivated ruthlessly discriminatory laws, which had dire effects on the everyday lives of all South Africans. They had a stronghold on the education system, public radio, imposed living areas, and so forth. The lengths to which the South African Publications Control Board was prepared to go in order to ensure complete segregation based on language will be remembered amongst the most absurd ventures in human history (Peffer 2016). Bearing this in mind, it seems paradoxical that after 1994, when South African citizens were encouraged to rediscover themselves as a nation, the notion of multilingualism was lauded as an asset and romanticised, as it gave the opportunity to celebrate the synergy of the "rainbow nation".

Contemporary artistic interventions in South Africa frequently feature these contradictory relations between proclaimed intentions and tangible consequences linked to the ways in which languages were administered, manipulated or stifled according to conflicting political agendas. Churchill Madikida, for example, shows how language discrimination produces the effect of choking, which he performs by ingesting or regurgitating maize porridge. In the Interminable Limbo (2004) series, Madikida refers to reductive exoticisation of certain traditions in South Africa as well as the stifling effect these self-same traditions can have on an individual. Kemang Wa Lehulere performs several versions of a scene where he places safety pins under his tongue.4 This performance references the novel Under the tongue by the Zimbabwean writer Yvonne Vera (1996), wherein the main character, Zhizha, has lost the will to speak. While Wa Lehulere does not give precise indications as to what his gesture is meant to signify, the image of a safety pin can convey an eloquent set of vocabulary: 'Safety pins join things...They conceal. I like their materiality; they're about refusal to speak' (Wa Lehulere cited by Sassen 2011:3).

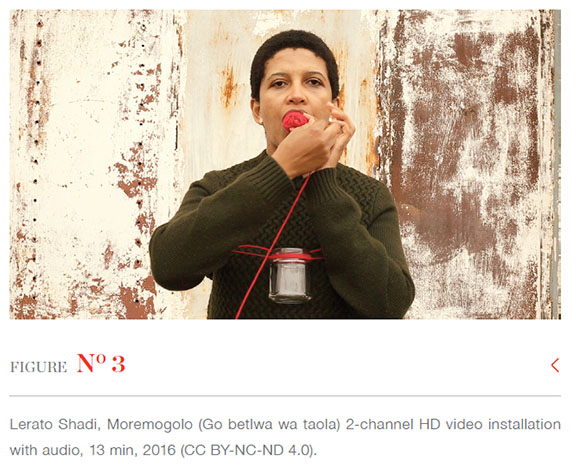

Through learning about the existence of a most cruel form of punishment, the slave mask, Lerato Shadi extends her research on language interdiction to the Caribbean. The slave mask, which makes speech impossible and breathing difficult, betrays the extremes the master was prepared to go to in order to impose his domination. As in Madikida, Shadi's performance strikingly posits the faculty of language as almost concomitant with the ultimate vital function: indispensable, life-giving breath. The video Moremogolo (Go betlwa wa taola) (2016) (Figure 3) shows Shadi winding a length of red thread around her tongue until the mouth is filled with it. Just when the onlooker fears that she will not be able to breathe, the artist spits out the formless packet. Thread has come up in many works by Shadi as a metaphor for language.

These three performances speak of language specificity and oppression in the context of the colonial project; they speak of the ongoing impression of being stifled or gagged that remains in the formerly oppressed, long after the discriminatory legislation has been amended (Fanon 2011[1952]:245-250); they speak of the endless process needed to [un]do wrongs and erasures, a process which would have to include attempts at unravelling the fraught history of exploitation - a seemingly interminable process which, notwithstanding much talk of the miraculous peacefully negotiated transition in South Africa is only just about to begin (Coetzee 2013:ix).

Given the fraught, unresolved nature of the historical relationship between languages, and more precisely the unacknowledged power inequalities between them, translation, which is first and foremost considered to be a benign act of mediation, of reciprocity and mutuality, carries a dark undertone in South Africa as it does in most post-colonial contexts. For the purposes of this text, prompted by Simnikiwe Buhlungu ([Sa]),5 I will claim the prefix [un-] as an indicator of the quest to unravel the abovementioned complexities and as an indicator of the double-edged nature of the processes involved. I will posit the neologism "[un-]hearing" or "[un-]performing" not as an adjective but as a verb,6 suggesting the possibility of [un]hearing the not-yet-heard or the un-situated. The prefix "[un-]" here introduces an active, constructive intervention easing tension, relieving constraint, amending ignorance, liberating entrapment, as one would uncork a bottle, unscrew a lid, unhinge a door, undeceive someone of a preconceived idea or attempt to undo damage. I propose to proceed to "[un]hearing" the mentioned instances as one would decipher a code or unravel a tangled piece of string. The action of [un]hearing comes to signify a fine-tuned form of informed and involved listening capable of bringing to the fore that which ordinarily goes by unheard or remains stifled.

Instead of well-meaning but ineffectual incitement to silencing translation, one task to be performed by this fine-tuned listening might be to develop an ear for the multitude of accents, which may allow the listener to appreciate the cultural situatedness of a speaker. In South Africa, most citizens speak a great variety of languages and this is audible in the way they express themselves and in the way they pronounce certain words. Many express resentment to those (most frequently English-only-speakers) who speak as though it went without saying that proficiency in English were a "universal" given,7 and that the fluid and sophisticated pronunciation of this language were proof of intellectual superiority. In South Africa this is what is meant by a "monolingual" (Coetzee 2013:13) voice - by juxtaposition, an "accented" way of speaking is inflected, shows situatedness, indicates individuated thought patterns, carries the legacy of historical exchange between languages and the power relations involved, bears recognition of the multiple languages involved in the totality of any act of speech.

[Un]hearing accents

Recognition of individuated ways in which speakers make use of language and voice (Gentric 2019), of the auditory features enabling one to place the speaker socially and regionally (Coetzee 2013:7), can be observed all over the globe. One of the platforms designed to allow a radical rethinking and enlargement of the methodologies underlying Documenta 11 curated by Okwui Enwezor in 2002 explored the notions of Créolité and creolization. In the introduction to the accompanying collection of essays the editors lay out the general principles guiding this rearticulation. They posit creolisation as '[t]he productive experience of the unknown, which we must not fear' (Enwezor 2003:15). The initial proposal developed in Documenta 11 was derived from creolisation in the Caribbean context, but it is evident that throughout contemporary society language is in continual flux and migration. Creolisation occurs wherever languages enter into contact and inevitably leave marks on each other.

With the aim of better positioning the specificity of Buhlungu's and Kala's approaches, I have singled out three artistic projects by Violaine Lochu, Bouchra Khalili and Lawrence Abu Hamdan to serve as a foil. Briefly touched upon only in the aspects that are of interest to the current argument, they will illustrate the far-reaching ramifications and complexities linked to the processes involved, purposely selected from radically different political contexts and artistic approaches in order to fathom the extent of the phenomenon.

Violaine Lochu researches and performs the endless ways in which vocal expression morphs from one state to another, shifting over time, according to gender, in situations of migrancy, in storytelling, according to hearsay, in different states of consciousness, remembrance or affect, according to socio-economic circumstances. She explores how wording echoes landscape, conventions of female presence in language, art school parlance, the babble of the young child discovering their voice as their own, and so forth. Lochu's work is developed in dialogue with a wide diversity of language users and rendered in video pieces like Chinese Whispers (2013) and Lingua Madre (2012) or in a project in 26 performative episodes under the title Abécédaire Vocal (2016). While Lochu's tool is her own voice, she addresses vocal expression in the widest sense, mostly based on observation of its use by others.

This is also the case for Bouchra Khalili, who focuses on displacement and migrancy as it manifests through language specificity. By means of recorded interviews with expatriates, Bouchra Khalili points to the ways their serendipitous relocations filter through into the way they relate to their new daily lives. This can be picked up in aspects pertaining to accent and particular uses of language. In the series Speeches - Chapter 1-3 (2012-13) she may invite her interlocutors to first select, then translate, memorise and ultimately speak fragments of major texts in their own creolised first language,8 thus reactivating them into their former "home" context. She may also invite her collaborators to write a manifesto, which is then spoken in the language of the host country.9 These works pose the hypothesis of the task of the "civil poet" (Jeu de Paume 2018), from whose subjective experience a collective voice might emerge.

Likewise, Lawrence Abu Hamdan is finely attuned to voice and sound as a political entity. In one striking example encountered in Holland referenced by his project Conflicted Phonemes (2012), international policing took an interest in supposed "regional" accents, deeming this method to be a valid way of drawing conclusions about the precise origins of migrants and proceeding to their expulsion in accordance with the presumed "findings". Each of the three examples is interested in instances where accents serve to put the finger on difference or variation;10 one might say that the artists work in an anthropological attitude, meaning that - notwithstanding their sensitivity and sincere involvement with the cases studied - they adopt the onlooker's point of view, following up on cultural specificity in an alienated context.

In comparison, the South African situation - where multiplicity of accent denotes "home" - requires the hands-on approach found in Carli Coetzee's book with the fitting title, Accented futures, language activism and the ending of apartheid (2013). Coetzee's argument is centred on teaching situations that point to the dire urgency with which a new approach to the language question in South Africa has proven to be an imperative, seeing that - even though the laws have been amended and the advent of the "new" South Africa has been celebrated as a miracle of peaceful transition - in reality, the unequal power relations between languages persist in everyday life. Coetzee's language activism consists in not avoiding misunderstanding and disagreement, claiming them as 'productive of, rather than the opposite of transformation' a locus where the situation one's interlocutor speaks from can be apprehended (Coetzee 2013:xiii,12,45-60; Ost 2009:420). Coetzee posits the study of inflexion not as an anthropological observation of difference but as a self-transforming labour, where the teacher or reader performs an act of activism, which contributes to bringing about the ending of segregation. Accented thinking is the act of developing 'a point of view that is at home in a non-monolingual voice' and 'shows an awareness of multiple scenes of reception' (Coetzee 2013:15).

The situations described above showcase multiple attitudes towards accent. When considered an indicator of provenance, personal accent cuts two ways as it can signify the epitome of belonging or of not belonging. As an affirmative attitude embracing cultural difference, creolisation and language specificity, it is celebrated. Amongst other things, it proclaims resistance to the hegemonies erecting unaccented ways of expressing oneself as 'purity, monolingualism, false universality' (Enwezor 2003:15). Contrarily, when misused as a tool to classify others it becomes part of a politics of inclusion or exclusion as in the example showcased by Abu Hamdan in Holland. On an even darker note, this multifaceted issue results in extreme violence to the one singled out as a foreigner11 by his or her inflected way of expression.

The divergent scenarios described above point to the vast number of vectors that remain '[un]written, [un]spoken, [un]performed' in this constellation, as has been announced in the title to this essay which hints at the creation of the word '[un] performed', borrowed from an artist's statement by Simnikiwe Buhlungu ([Sa]:[Sp]):

Through print and text based mediums and often taking form of sensory, video and installation based forms, my interest in navigating through the personal, experience, transgenerational and socio-historical narratives presents itself as a complex web of [re]imagined engagements surrounding, but not exclusive to, issues surrounding the positionality of the aforementioned lived experiences in relation to language and knowledge production(s) - which are [un]written, [un]spoken, [un] performed, made [in]visible.

[Un]performing

Simnikiwe Buhlungu's Free Lettering Translationisms (2016) begin with an action in the streets of Johannesburg CBD (Figure 4). The artist brings a plastic chair with her. She also introduces a piece of cardboard inscribed street-vendor-style in black liner marker: 'FREELETTERING TRANSLATIONISMS'. For a period of three months, the artist joins the vendors and offers a service translating her clients' messages into 'broken InglishI', a paradoxical action: breaking English as a 'decolonial option of debunking notions of intellect and knowledge as we know it' (Mark Pezinger Books [Sa]:[Sp]).

How can this remark be decoded? Providing a public service of letter writing can be read as a reference to the fraught history of housing policies dating back to the discovery of gold and the regulation of "influx control" in the cities. On the one hand, a vast work force was needed for the mines, but on the other hand the privileges provided by city life were meant to be restricted to Europeans (SA History Online 2019). The mineworker's stay in the city was considered a provisional arrangement. The workers were accommodated in single-sex hostels, referred to as "closable" or "enclosed" compounds, housing between eight and 16 men per dormitory in highly controlled, near-carceral, conditions (Bezuidenhout & Buhlungu 2011; Josephy 2015:466). Their families remained in the designated rural areas (referred to as "homelands" under apartheid policy of "separate development") or in the neighbouring countries whence the miners had been recruited by the mining industry. Seeing that few of the involuntary migrants were literate, many separated families relied on a third party to write, and then, at destination, to read the letters that allowed them to remain in contact.

These living conditions, abusive and unenviable as they were, brought with them their own set of aesthetic solutions and subjective imaginaries. Titu Zungu for example made a living (and incidentally a unique contribution to contemporary art in South Africa) by decorating envelopes for these messages in transit (Williamson 2009:74). The artistic career of Stephen Kappata, who was recruited from Barotseland in Zambia, commenced during his period in the Johannesburg mines. Kappata's first drawings were commissioned by his fellow compound inhabitants (McMillan 1997:22). Throughout the convoluted history of mining in South Africa photographers have accompanied and documented life in the compounds (Josephy 2015), these images are sensitive to how changes in mining policies reflect in the private lives of the miners. They observe minute details, individual ways of making-do to allow oneself the tiniest space of intimacy in the over-crowded compound dormitories, solutions invented to cope with the harshness and dehumanising conditions.

Buhlungu's (2019a) service acknowledges the full complexity of this legacy by deviating from classic public letter writing in one significant detail: instead of upgrading inept language skills into fluid, standard, flawless English, she produces vernacular. She actively "breaks" the world-class language.12 Her services joyously translate love letters, birthday greetings, congratulations, task-lists, CVs, poems or insults. Perfectly aware of the shift that occurred since the first context wherein public letter writing was adopted as a survival technique, Buhlungu nevertheless writes on paper, overriding electronic communication, even resorting to the old-fashioned carbon copy (Figure 5). These copies are later assembled into an artist's book and published in the form of the slim fourteen-page volume described in the opening lines of this text. The simplicity and furtiveness of the set-up is striking: a plastic chair, a cardboard sign, sheets of carbon copy paper, a ballpoint pen. Buhlungu's Translationisms are strictly free of charge. This is motivated by the fact that flawless English spoken with a sophisticated accent is currency (Ndebele 1991 [1987]:117) - a certain market value is attached to it. Instead of normalising after the end of apartheid legislation, the discrimination has instead worsened under the neo-liberal politics of the ANC government. A sophisticated English accent can obtain the speaker a good job, it augments social status (Seabe 2012). The Free Lettering Translationisms protest this status quo: 'The presence of Broken Inglish further challenges the notions that one's [in]ability to comprehend, read, write is a reflection of one's intellectual capacity' (Mark Pezinger Books [Sa]:[Sp]). They protest the idea of business-like performance as excellence,13 they consciously [un]perform - they are engaged in 'breaking Inglish' (Mark Pezinger Books [Sa]:[Sp]).14

The subtlety of Buhlungu's project lies in the fact that - beyond being about sound, voice or the English language under post-colonial critique - it is about the way that Buhlungu (and also her reader, if he/she will agree to follow her reasoning) might imagine what the translationisms would sound like if read out loud. Seeing that obviously there is no "correct" way of pronouncing these broken words, the way the reader tries to unravel the writing makes up his/her personal accented attempt to articulate the silent letters. The project takes effect only on a virtual level -Buhlungu does not produce sound recordings of any kind: 'The auditory element to the project was totally in the reader's way of articulating' (Buhlungu 2019b:[Sp]).

The user of this project will have to "[un]hear" this little booklet, as one would uncork a bottle or unscrew a lid. If he/she accepts to participate in the venture, this will be an activist task in the sense described by Carli Coetzee (2013).

This wrestling, this process of activist [un]hearing is in close correlation with what Barbara Cassin (2018:11,19) refers to as the 'généalogie du performatif (genealogy of the performative) or 'la performance-performativité de la parole' (the performance-performativity of speech). Incidentally, Cassin (2018:150) identifies the multivocity of the political intentions behind the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa (1994-2001) - memory, justice and speech - as a striking example in her diachronic (genealogical) analysis of the interrelations between rhetoric and performative usefulness of language. Herein Cassin (2018:138,185-186) identifies a case of 'un logos qui "construit la réalité"' ('logos "constructing reality"'). In her approach as a language philosopher, Cassin's task is to comment on the speech forms she encounters and the shifts operated within uses of language - the ways in which words hold true as deeds. The artist, Buhlungu, has other efficient means at her disposal. By writing 'breaking Inglish', enacting the role of the medium itself, the public writer, Buhlungu will have profoundly disrupted something in the uses made of language: she will have unanchored language from colonial and apartheid legacy, setting it afloat once more. She will have [un]performed - and in the same gesture incited her spectator to [un]perform - not a translation but a 'translationism'. It turns out that this [un]performing gesture is urgently needed in the fraught South African post-post-apartheid context, and no less urgently for our planet - this service is provided entirely free of charge.

[Un]written, [un]spoken

Euridice Zaituna Kala titles her intervention (Tedet) Telling time - from COMPOUND to CITY [Conditioned Entry]. For this intervention in public space Euridice Kala chose a train station on the line run by the company Metrorail. Connecting the compounds bordering central Johannesburg, it is the point of entry into the city. Kala, as a Mozambican expatriate living in South Africa, was struck by the oppressed silence as the crowds of commuters hurried through the station. The uninformed onlooker might attribute the isolation between the individual commuters to high crime rates in South Africa, but the situation has many other facets.

A legacy of apartheid pass-regulated influx control, the buildings that used to house the compounds remain. These structures are today administered by several different semi-private or private housing schemes and continue to function in altered form (Josephy 2015:468). Those who live in them do not have the means to find accommodation in the inner city, but they are part of the labour force that allows the city to function.15 Users of the yellow Metrorail trains, they commute on a daily basis, hurrying through Jeppe station in the early hours of the morning. Titling her intervention From Compound to City [Conditioned Entry], Kala refers to this complex constellation.

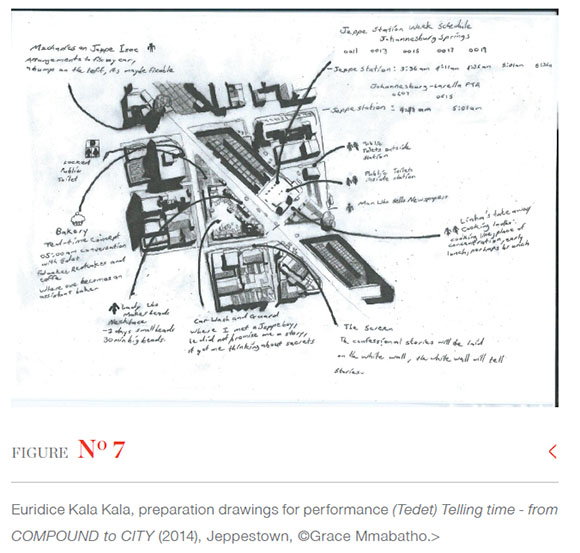

Remembering her first encounter with Jeppe Metrorail station, Kala remarks that what was even more striking than the unspeaking crowd was the fact that almost no indication was given as to which train would leave from which platform and at what time. No overhead announcements, no electronic display panel, no screens on the platforms: trains came into the station, emptied themselves of their commuters and then refilled and departed, in industrialised fashion. Somehow, notwithstanding the complete absence of public signage, the users seemed to know which train was going where. The elusive unspoken common knowledge orchestrating this complex choreography struck the newcomer as nothing short of spellbinding: 'No one was speaking, just going into the trains' (Kala 2019a:[Sp]). To Kala it seemed that the only way to get an inkling of its functioning would be to interrupt - "disturb" - the silenced flow of [un]information. As a non-South African, Kala had developed a strategy she refers to as 'insert where possible' (Kala 2019a:[Sp]). She spent two weeks observing the ebb and flow of this unspeaking crowd, gleaning bits and pieces of information about the train schedules and the directions the trains would take, not forgetting the vendors making a living as part of the informal economy on fringes of the transport system.16 Kala likens the activity of cultivating and tending this aptitude to glean knowledge to the watering of a plant. Incidentally she did tend a small tree in a pot as part of the preparation. Kala contributes a drawing (Figure 7) showing the details of this ecosystem and the pattern of her movements in it in the form of conversations shared, lunches partaken, goods exchanged, basic necessities catered for.

On 22 March 2014 in the early hours of the morning (before 4 a.m.), she installs her folding chair in a square space, which she demarcated by white tape on the concrete flooring of the train station, sharing this space with the small tree17 she tended over the past two weeks (Figure 6). Equipped with a time-keeping device (her mobile phone) and a megaphone, she takes up her position and starts announcing her self-devised train timetables based on knowledge she had managed to gather in the previous days: 'The 4:11 to Springs on platform 2', 'The 4:43 to Leralla PTA on platform 1'. As the action unfolds, two incidents start occurring: the commuters start coming towards Kala, asking her for information - something in the fear-filled pattern seems to have shifted; and then, as she is about to leave, a security man employed by Metrorail appears from out of nowhere and tells the artist to leave because these are the company's premises.

In retrospect, Kala draws attention to the observation that the crowd seems to behave according to a pattern, as though the individuals came in volumes, remarking on the beauty of the movement. Likewise, she sees the verbal exchanges as "pockets" of information and language within a sea of non-communication. Kala speaks English in this space, while inside Jeppe station the commuting locals speak their respective languages. Kala wonders whether she was in the wrong space - or has her foreign presence here met a serious need for something? People seemed to have given up trying (Kala 2019a) - the irregular presence of the immigrant (Kala) seems to have called forth a sense of orientation. The artist within her demarcated space becomes a point of intersection, a coordinate in the never-ending flux of [dis]oriented commuters functioning to [in]tangible clockwork.

These observations become even more poignant in relationship to the complex interplay of opposing interests linked to claiming a sense of belonging to South Africa where public space is always contested. A crowd can be regulated by a common unspoken surge that allows train stations accommodating two million commuters per day (Metrorail website [Sa]) to function without written indications. As a matter of a split-second this self-same crowd can erupt into what is referred to as xenophobic violence. Having developed an inflated sense of nationalism, locals have been known to burst into acts of unfathomable violence against those they have identified as non-South African. Kala refers to these sporadic incidents as 'a collective lack of knowledge' or 'collective amnesia' (Kala 2019b:[Sp]).

This amnesia goes much deeper than mere forgetfulness, ignoring for example the solidarity shown amongst Southern African liberation movements during the fight against apartheid. This amnesia amounts to a blank - a paralysis of both thought and memory, exceeding the reasonable - [un]fathomable. South African post-apartheid society paid close attention to identity politics and accordingly language specificity came to be vested with a new form of nationalism. In an exaggeration of that which at the outset was the need for restored consciousness,18the multilingual "South African accent" came to be vested with a new form of hegemonic monolingualism, which would indeed be the opposite of what Carli Coetzee would like to be understood as "accentedness". As a consequence, those who did not have the local accent (inflected speaking resonating the local languages) - guest workers and commercial partners from neighbouring Southern African countries - were identified as a threat to the new-found national dispensation. Derogatorily referred to as "amakwerekwere" individuals thus singled out by their way of speaking became the victims of sporadic xenophobic attacks. Kala, making herself conspicuous as a foreigner, posits herself not only a coordinate but as the potential target for collective amnesia to erupt into blank, unthinking violence.

Language identity cuts two ways: it is simultaneously a marker of belonging and a means of singling out those who do not belong. The common denominator between these two extreme cases is the sense of anatopism, the 'sense of being out of place' (Makhubu 2019:20). This is expressed by furtiveness of action, a quality referred to by Nomusa Makhubu, who further suggests the possibility of 'live art as a question of citizenship or as a mode of understanding belonging to governance' (Makhubu, 2019:20,21). The [un]spoken and [un]heard (inaudible) and furtive flow of clairvoyant and violent information crystallises when it is interrupted by Kala's anatopistic artistic gesture. Recalling the title - Telling time - the interruption is in the telling, in speaking out loud and putting shared wisdom into words. Telling, using embodied voice (Gentric 2019), the interruption is performed by inserting the physical presence of the artist's body into this space. 'Inserting yourself is always a failure', Kala (2019a:[Sp]) remarks. And elsewhere: 'Therefore around failure, we could find a sense of commonality' (Kala 2014:46-49).

[Un]hearing - once more

The two instances described at the outset of this paper each devise a ploy to outwit the [un]spoken, operating a shift in the way language is put to use. By the same gesture they evidence the performativity of language. In both cases this performativity arises due to the diachronically complex relationships between languages and as a result of thinking language in the way it functions in space and time. Kala intervenes in a train station on a line connecting historically charged sites within a changing social fabric. Buhlungu inserts herself amongst the street vendors, selling a service, which draws its significance from solutions contrived to overcome the constraints arising within a segregated community. The strategies adopted by both artists can be said to devise material situations echoing Heinz Wismann's (2012:62) central thesis: that some things cannot be achieved within one single language. They however become possible by navigating between languages. When navigating this space between languages, voice becomes furtive, impossible to pin down; it is inaudible to listening as we know it. This form of furtive voice needs the capacity to actively [un]hear the inaudible, as one would decipher a code. As Buhlungu puts it: 'The performative act of translation becomes a way of engaging and exchanging with language as something that is fluid, where some things are lost while others are gained' (Mark Pezinger Books [Sa]:[Sp]). The performative act referred to by Buhlungu is the same as analysed by Barbara Cassin (2018:108), following John L. Austin, who concludes on the inability to categorise the performative force of words, deferring to the 'the total speech act in the total speech situation' - a quest I have performed here by describing and contextualising Buhlungu and Kala's anatopistic gestures, seconded by Madikida, Wa Lehulere, Shadi, Lochu, Khalili and Abu Hamdan. In agreement with Cassin (2018:246), who concludes that there is neither a definition nor a solution that holds true in all cases, Buhlungu and Kala create situations where language is outwitted, and where each one individually [un]performs the act of telling (and thereby disturbing) time or the act of breaking language.

The two artists seem to enter the diachronic perspective of this nexus from two opposing but analogue vantage points. In Buhlungu's work the spoken is translated into the written for the unheard (ady.) to be "[un]heard" (v.) in the virtual space of the imagination of the reader, who will complete the process of activist unhearing (n. or v.) as described by Carli Coetzee (2013). In Kala's intervention, the unspeaking crowd, hurrying though public space, is interrupted by sonic intervention. By shifting the frame of reference, the silent, almost clairvoyant wisdom underlying the movements of the crowd is revealed. Voice weaves its way in and out of these constellations. A silent booklet, breaking language, and an expatriate artist with a megaphone, telling and disturbing time, speaking of failure as a method of 'getting information out of the unknown' (Kala 2019c:[Sp]) - when met by the reader's or commuter's active, [un]hearing, complicity, these are instances of [un]performing voice.

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks to the artists and to the members of the working-group Sound Unheard for the generosity with which they have engaged in conversation. The research for this text was made possible by a postdoctoral scholarship from the University of the Free State of South Africa and the research programme Sound Unheard [Pratiques et theories de l'art contemporain (PTAC EA 7472), Rennes, Musée des beaux-arts de Rennes and Universitàt der Künste - Master Sound Studies and Sonic Arts, Berlin].

Notes

1 . Intentionally spelled with a "y".

2 . Central Business District. See South African History Online (2019).

3 . Francois Ost (2009:68-102).

4 . See Kemang Wa Lehulere, A Native of Nowhere (A Sketch), 2014.

5 . She uses the prefix [un-] in this way in her artist's statement published on the website of the blackmarkcollective. I quote the excerpt at length as an introduction to my paragraph on [Un] performing.

6 . Kemang Wa Lehulere frequently makes use of this method, see for example Remembering the future of the hole as a verb (2010).

7 . Let us bear in mind that the same question provokes heated debates in the European Union (Ost 2009:362-364.

8 . Speeches - Chapter 1: Mother Tongue (2012).

9 . Speeches - Chapter 3: Living Labour (2013).

10 . 'The literature on accent is intent on differentiation and stratification, both of phonemes and of the ways in which we are placed and grouped in the world' (Coetzee, 2013:7).

11 . In South Africa, this phenomenon has gone to extremes in what is referred to as "xenophobic violence", which will be referred to later on in this text.

12 . Francois Ost considers several language situations concerning the occidental dream of a "perfect" language which might once and for all do away with misunderstanding (as reserved to one particular point of view, as it turns out). In some of these totalitarian projects one language is artificially imposed as the dominant idiom. Ost (2009:68,97,100,102) makes a case against all forms of language projects aimed at 'uniformisation-universalisation', bringing him to the argument, that what might be of universal value in language is each language's imperfection, it's deficiencies, that which it lacks in order to seamlessly transpose experience and ideas and the notion of "perfect understanding". It is this imperfection which constitutes a language's infinite capacity to adapt and therefore to signify (Ost 2009:103).

13 . After following up on the different meanings inherent in the etymology of the word "performance" Cassin (2018:14,15-17), like Buhlungu, points to performance understood as the tyranny of delivering corporate style "excellence" known as "performance-evaluation" or "ranking" in global English.

14 . Like Ost, Enwezor et al. (2003:16) plead for the importance of 'Converting] the logic of the hegemonic sphere into the symbolic capital of cultural difference', bringing them to the question, 'What constitutes a créolized "translation"?'

15 . Nomusa Makhubu (2019:19-40) addresses this set of questions in the context of Cape Town, which has a different history from Johannesburg, but where the same sense of anatopism can arise out of the continual unsettledness of the life of a daily commuter.

16 . As part of the PublicActs project, curated by Katharina Rohde and Thiresh Govender, Kala had devised three performances to take place the same day, of which (Tedet) Telling time [4:00 - 5:00] is the first, followed by Troca (No Story/No Cup) [13:00 - 14:00] and finally Exit Time programmed from 22:00 to 00:00.

17 . When questioned about this tree Kala replied that it was meant 'as a means to introduce biophilie into a necrophilic environment' (Kala 2019b:[Sp]).

18 . The way Steven Biko would have argued for a need of 'consciousness of the self' or what Franz Fanon (2011[1952]:242) referred to as 'conscience en-soi-pour-soi'.

REFERENCES

Alexander, N. 2011. After apartheid: The language question, in After apartheid: Reinventing South Africa?, edited by I Shapiro and K Tebeau. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press:311-331. [ Links ]

Bezuidenhout, A & Buhlungu, S. 2011. From compounded to fragmented labour: Mineworkers and the demise of compounds in South Africa. Antipode 43(2):237-263. [ Links ]

Buhlungu, S. [Sa]. Artist statement. [O]. Available: https://blackmarkcollective.wordpress.com/simnikiwe-buhlungu/ Accessed 27 July 2020. [ Links ]

Buhlungu, S. artist, 2019a. Telephone interview conducted on 18 March 2019. [ Links ]

Buhlungu, S. 2019b. E-mail to Katja Gentric, 27 March 2019.

Cassin, B. 2018. Quand dire, c'est vraiment faire, Homère Gorgias et le peuple arc-en-ciel. Paris: Fayard. [ Links ]

Coetzee, C. 2013. Accented futures: Language activism and the ending of apartheid. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Enwezor, O. (ed). 2003. Créolité and creolization: Documenta 11, Platform 3. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz. [ Links ]

Fanon, F. 2011 [1952]. Peau Noire, Masques Blancs, in Frantz Fanon CEuvres. Paris: Éd. la découverte:63-257. [ Links ]

Gentric, K. 2019. Sonic fingerprints: On the situated use of voice in performative interventions by Donna Kukama, Lerato Shadi and Mbali Khoza. Image & Text 33:1-25. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a10 [ Links ]

Gentric, K. 2016. Traduire comme pratique artistique, cinq propositions-interfaces en Afrique du Sud. Marges, Revue d'art Contemporain 23:74-85. [ Links ]

Jeu de Paume. 2018. Text for Bouchra Khalili's exhibition Blackboard at the Jeu de Paume, Paris, 5 June-23 September 2018. [ Links ]

Josephy, S. 2015. Fractured compounds: Photographing post-apartheid compounds and hostels. Social Dynamics 40(3):444-470. [ Links ]

Kala, E & Moiloa, M. 2014. Four thoughts on failure: Call and response, in Boda Boda Lounge Project, From Space (Scope) to Place (Position):46-49. [ Links ]

Kala, E. 2019a. Telephone interview with Katja Gentric, 8 May 2019.

Kala, E. 2019b. E-mail to Katja Gentric, 26 June 2019.

Kala, E. 2019c, artist. Interview by Katja Gentric, 27 June 2019. Paris.

Mark Pezinger Books. [Sa]. Book Blurb. [O]. Available: http://www.markpezinger.de/simnikiwe.html Accessed 27 July 2020. [ Links ]

Makhubu, N. 2019. Artistic citizenship, Anatopism and the elusive public: Live art in the City of Cape Town, in Acts of transgression: Contemporary live art in South Africa, edited by J Pather and C Boulle. Johannesburg: Wits University Press:19-40. [ Links ]

Makoni, S. 1998. African languages as European scripts: The shaping of a communal memory, in Negotiating the past, the making of memory in South Africa, edited by S Nuttall and C Coetzee. Cape Town: Oxford University Press:242-87. [ Links ]

Metrorail website. [Sa]. Homepage. [O]. Available: http://www.metrorail.co.za Accessed 27 July 2020. [ Links ]

McMillan, H. 1997. The life and art of Stephen Kappata. African Arts 30(1):20-31,93-94. [ Links ]

Ndebele, NS. 1991 [1987]. The English language and social change in South Africa, keynote adress delivered at the Jubilee Conference of the English Academy of South Africa; Johannesburg September 1986. English Academy Review 4(1):1-16. [ Links ]

Ost, F. 2009. Traduire: Défense et illustration du multilinguisme. Paris: Fayard. [ Links ]

Peffer, J. 2016. Notes on cuts on censored records. Afrikadaa 10:64-65. [ Links ]

Sassen, R. 2011. "He Leaves No Trace", Sunday Times Review 2, 4 December:3. [ Links ]

Seabe, LV. 2012. Performing the (un)inherited: Language, identity, performance. MA dissertation, University of Cape Town, Cape Town. [ Links ]

South African History Online. 2019. Johannesburg, the Segregated City. [O]. Available: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/johannesburg-segregated-city. Accessed 27 July 2020. [ Links ]

Vera, Y. 1996. Under the tongue. Harare: Baobab Books. [ Links ] Williamson, S. 2009. South African art now, New York: Harper Collins. [ Links ]

Wismann, H. 2012. Penser entre les langues. Paris: Albin Michel. [ Links ]