Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a10

ARTICLES

The importance of context-relative knowledge for illustrating wordless picture books

Maria Magdalena EllmannI; Elmarie CostandiusII; Neeske AlexanderIII; Gera de VilliersIV; Adrie HaeseV

IStellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa. miaellmann@gmail.com

IIStellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa. elmarie@sun.ac.za ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3561-7652

IIIStellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa. neeske@sun.ac.za

IVStellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa. gera@sun.ac.za ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3774-2863)

VUniversity of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. ahaese@uj.ac.za ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8222-3010

ABSTRACT

This study investigated the role of signs in wordless picture books and their influence on meaning making. The article's main aim is to highlight the importance of using culturally appropriate signs to foster narrative comprehension in wordless picture books. This genre of books can be a useful method and tool for translating cultural knowledge into images, but their production can be a difficult process because skilful execution is required for successful communication. Wordless picture books can serve as a medium that encourages storytelling and fosters a love of reading. This research involved the creation and semiotic analysis - through participant reactions - of three wordless picture books whose stories are situated within the Xhosa culture. Theoretical perspectives of social semiotics and narratology were used as lenses through which to inform the research. The findings include evidence of the importance of understanding context-relative knowledge and of using appropriate signs, symbols, and signifiers when translating and portraying narratives in wordless picture books.

Keywords: Wordless picture books, storytelling, semiotics, narratology, context-relative knowledge, South Africa.

Introduction

This study investigated the role of signs in wordless picture books and their influence on meaning making. This article's main aim is to highlight the importance of using culturally appropriate signs to foster narrative comprehension in wordless picture books. This genre of books can be a useful method and tool for translating cultural knowledge into images, but their production can be a difficult process because skilful execution is required for successful communication. The use of context-relative and culturally relevant images is integral in this communication. It is, therefore, crucial for those working in the book production field, such as storytellers and illustrators, to recognise the diversity of signs and signifiers that exist within the culture of their target audience. This is especially important in a multicultural, -racial, and -lingual society such as South Africa, where the focus of this study lies. This research involved the creation and semiotic analysis - through participant reactions - of three wordless picture books whose stories are situated within the Xhosa culture. During the analysis, interesting and surprising points regarding the representation of signs and symbols were exposed.

Context

Wordless picture books

Frank Serafini (2014:24) describes wordless picture books as a 'visually rendered narrative'; they consist of a series of pictorial images that reveal a visual text. The attributes of signs, symbols, and signifiers in wordless picture books allow for an open-ended reading; a process in which readers use their contextual backgrounds and experiences to make sense of the visual images they encounter within the book. Patricia Crawford and Daniel Hade (2002:68) comment that 'unlike words, even those fixed in a written text, visual images have almost infinite capacity for verbal extension, because viewers must become their own narrators, changing the images into some form of internalised verbal expression'. Wordless picture books can give expository information that might be difficult to explain in words and can act as a more complete form of communication (Dowhower 1997:60).

Images are often considered a universal language that can transcend linguistic and cultural borders. Joannis Flatley and Adele Rutland (1986:281) emphasise the value of wordless picture books in educational environments, noting that learners are 'exposed to ideas from other cultures in a pleasant, nonthreatening, and fun manner' and that 'ideas can be exchanged and knowledge can be obtained without being confined by print'. However, Ellen Spitz (1999:21) argues that they can also 'carry and challenge prevailing cultural ideologies and stereotypes' that could be misinterpreted by another culture. When books are translated from one language and culture into another, the different modes of verbal, visual, and aural need to be considered (Oittinen, Ketola & Garavini 2018:203). Riitta Oittinen, Anne Ketola, and Melissa Garavini (2018:203, emphasis in original) suggest that '[t]aking a picture book from one language and culture to another means revoicing each of these modes'. Images in picture books are, therefore, never "neutral", but always carry the signs and symbols of a cultural context; they are semiotically charged.

This is especially important to acknowledge for a multicultural South African context, where each different culture has its own signs and symbols. This can lead to meanings being misunderstood, hidden, disrespectful, or offensive. In a postcolonial and post-apartheid context with a history of ignoring and devaluing some cultures, it is important to create just representation of cultures and peoples and to work against white hegemony. In the teaching and learning environment, it is important to use context-relative and culturally relevant signs that learners can understand to create a safe space where signs and symbols from different cultures can be discussed.

The South African Context

Wordless picture books encourage readers to use illustrations to create a story in a language of their choice, a particular benefit in South Africa where there are 11 official languages. Their usefulness is further highlighted in respect to the country's literacy rate. Currently, South Africa has a youth literacy rate of 93,9% and an adult literacy rate of 79,3% (Statistics South Africa 2021) and picture books remain an expensive luxury. Many adults living in low-income areas are not able to read to their children because of their own low literacy skills, lack of books, and lack of time due to work commitments. These children enter formal education with a significant literacy gap. Culturally relevant wordless picture books could, therefore, foster a love of books, reading, and storytelling regardless of literacy levels, language preference, and age.

The research for this project was undertaken in Kayamandi, a township on the outskirts of Stellenbosch in the Western Cape province of South Africa. It was founded in the early 1950s and initially housed black migrant labourers employed on farms in the Stellenbosch area. Kayamandi was established as an area for black people according to the Group Areas Act of 1963 and many black people were relocated there from their homes in neighbouring communities. The main language spoken in the township is isiXhosa, although there is widespread knowledge of both English and Afrikaans. Education for children in Kayamandi is hindered by many factors such as overcrowded classrooms, educator absences, lack of infrastructure and facilities, and the presence of violence. These problems are echoes of apartheid policies and are experienced in many schools in South Africa (Abdi 2002). As a result, many residents in Kayamandi have not completed primary schooling and consequently have difficulty reading.

There are some local organisations that seek to address these problems. Bookdash is an organisation creating and distributing online storybooks based on the South African context to children via their free online application. They also seek to distribute printed books to children in South Africa - aiming for each child to own 100 books by the age of five. The Mikhulu Trust similarly creates wordless picture books and focuses on educating parents in rural communities about the importance of shared reading with their children. Collaborate Community Projects - a research partner for this article - seeks to create, print, and distribute wordless picture books throughout South Africa to foster literacy among preschool aged children. A key component of Collaborate Community Project's program, Dithakga tsa Gobala, is to use story ideas from children and adults in a specific community to create wordless picture books for that community. By sourcing stories from local communities, the project hopes to give parents and children a sense of ownership over the stories and books and to create context-relevant stories for these communities.

While the above are examples of practical interventions of wordless picture books in a local context, there is a paucity of corresponding scholarly research with specific regards to South Africa. This is a gap that Adrie Haese (née le Roux) and Elmarie Costandius are working to fill with their studies using wordless picture books to foster a culture of reading in low-literacy areas.1 Other notable contributors are Angela Schaffer and Kathy Watters (2003) who included a wordless picture book in their 'Formative evaluation of the first phase of first words in print' baseline study and Katherine Arbuckle's (2008) research on visual literacy as a tool in Adult Education programmes. This article aims to contribute to this conversation by emphasising the importance of creating context-relative and culturally relevant signs and symbols to promote successful narrative understanding in wordless picture books.

Theoretical perspectives: Social semiotics and narratology

This study utilised the theories of social semiotics and narratology. While they overlap to some extent, these theories complement each other in their nuanced differences and are, therefore, both important lenses through which to investigate the data. This section provides an overview of the theories and their relevance to this research.

Social semiotics is an expansion of semiotics; the theory developed separately -but at relatively the same time - by Ferdinand de Saussure and Charles Peirce. Semiotics is the study of signs and the part that they play in everyday life (Curtin 2009:52). The sign is at the centre of this theory as it is the 'fusion of form and meaning' (Kress 2010:54). Umberto Eco (1976:162) explains that a sign is 'used in order to name objects and to describe states of the world, to point toward actual things, to assert that there is something and that this something is so and so'. Semiotics - and its offshoot theories - revolves around the sign and the meaning making that develops from the study of the sign; that which is signified.

Social semiotics - as introduced by Michael Halliday (1978) and furthered by Robert Hodge and Gunther Kress (1988) - posits that one's understanding of the sign is assisted through the multimodal use of the codes and modes - semiotic resources2- unique to everyone. This multimodal approach to social semiotics 'emphasizes the social and cultural aspects of all communication, and pays special attention to the interplay between different modes of communication (i.e. speech, writing, images, gestures etc.)' (Insulander & Lindstrand 2008:85). These signs and codes are relative to the sociocultural contexts within which they are produced and interpreted, and can, therefore, be understood differently by separate cultural groups (Chandler 2002:156). Cultural groups, as defined by Kress (2010:72-73), are 'communities of people who by virtue of factors such as age, region, education, class, gender, profession, lifestyle, have their specific and distinct semiotic resources, differently arranged and valued'. This underscores the sensitivity of design in wordless picture books: that the imagery utilised is readable to the cultural group(s) for which the stories are intended. The correct signs must be encoded so that the recipient, through the use of their culturally specific semiotic resources, can best decode and understand the narrative.

Narratology, then, is the study of how narrative works. The term "narrative" can refer to narrative as a story, narrative as a way of writing, and narrative as a sequence of happenings. Luc Herman and Bart Vavaek (2005:13) define narrative as 'the semiotic representation of a series of events meaningfully connected in a causal or temporal way'. Narrative is a way of understanding and assigning meaning to text. The tools of narratology can therefore be used to analyse wordless picture books and explore oral storytelling.

Narratives from cultural groups (stories, myths, fairy tales, legends) have the power to communicate meaning that carries the history and knowledge of different cultures and traditions. According to Harold Rosen (1985:19), stories are predisposed products of the experiences of the human mind - narrative experiences are transformed into findings that we can share and compare with the narratives of others. The impulse that humans have to tell and share stories, and how experiences are shaped into narratives, point to the value of the narrative in the creation of meaning (Lyle 2000:54). Narrative understanding is an important cognitive tool through which all people in all cultures make sense of the world (Lyle 2000:53).

In the interaction between words and pictures, pictures boost the full meaning of words and vice versa; words elaborate on the image so that a variety of knowledge can be communicated in the two modes, thereby creating a dynamic narrative (Nikolajeva & Scott 2000:225). Crawford and Hade (2000:68) comment that 'unlike words, even those fixed in a written text, visual images have almost infinite capacity for verbal extension, because viewers must become their own narrators, changing the images into some form of internalized verbal expressions'. This, again, advocates for care in the use of imagery in wordless picture books; it is usually the sole method through which the narrative is told.

Kathleen Gilbert (2002:224) suggests that diverse elements of experience, thoughts, and feelings are brought together by narrative, which unifies and connects these elements to a central theme or goal. A social semiotic analysis explores the verbal and visual signs of a story and then interprets the symbolic meaning for narrative creation. Wordless picture books follow visual narratives and clues in order to make the story coherent. Therefore, the understanding of a wordless picture book is gained through a close combination of narratology and social semiotics.

Methodology

This empirical study employed qualitative methods to collect data. We used an interpretative lens (Klein & Meyers 1999; Yin 2003), which requires reflection on how data are socially constructed, to examine how stories that were translated into wordless picture books were received by teachers in the community. A case study research design was used and data included written notes, voice recordings, written stories, illustrations and illustrated books (Creswell 2003). Confidentiality and data protection were important considerations in this study and some participants were coded. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee: Human Research (Humanoria) of Stellenbosch University and this study took place during 2019.

This project was undertaken to investigate how the community would receive books containing stories about the community, written by community members, and illustrated by those outside the community. This entailed engagement in the social world of the study (Seale 2012) while taking into consideration that research is a multicultural process, as race, gender, ethnicity, and class shape the inquiry process (Denzin & Lincoln 2000). The study consisted of two phases: the first phase was the story creation project and the second phase, the semiotic analysis of the books. The wordless picture books were donated to the Grade R class of the school once the research project was completed.

In phase one, letters inviting participants to join the research project were sent to the youth division3 of Vision AfriKa.4 The supervisor of the youth division identified three Grade 9 learners who were interested in taking part in the story-writing phase of the project. Informed assent forms were obtained from the learners and their parents signed informed consent forms before the research started. The three volunteers were invited to meet for an introduction session, which was held at Vision AfriKa Primary School. We encouraged them to speak in whichever language they preferred (English, Afrikaans, or Xhosa) and there was a Xhosa interpreter present. The sample size of the participants was based on availability. The wordless picture books project, facilitated by the researchers and the principal of the school, ran every Tuesday and Thursday for four weeks in the after-school care setting. The three learners took part in drawing, painting, and storytelling during four art and story-writing classes (one hour each). The Grade 9 learners told, wrote, and painted their stories, which were based in Kayamandi or villages in the Eastern Cape where they had family. Following this, student illustrators5 (who were incidentally from different cultural backgrounds than the learners) designed these stories as wordless picture books and they were then printed.

Once the books were printed, semi-structured interviews (1.5 hours each) were held with four available teachers from the Vision AfriKa Primary School. The participants for this research project were: three Grade 9 learners (Xhosa culture), one principal (Xhosa culture), one research facilitator (Afrikaans culture), three illustrators (Afrikaans and English cultures), and four teachers (Xhosa culture). The cultural differences between participants are important to note as they impacted the way that the stories were translated into pictures and how these pictures were received. The qualitative data were analysed to discover 'underlying meaning and patterns in relationships' (Babbie 2010 cited by Schurink, Fouche & De Vos 2011:39). Using inductive content analysis, categories and themes were deduced from the data.

The wordless picture books

As this study revolves around the production and understanding of three wordless picture books, it is necessary to provide a brief explanation of each. As mentioned, to create the product, student-illustrators drew what they understood from the written stories based on their knowledge, research, and interactions with the story creators - Grade 9 learners in Kayamandi - and these books were analysed by teachers in Kayamandi for their accuracy and effectiveness. These illustrations are the outcome of a complex interrelationship between individuals and the signs and symbols intrinsic to different cultures (Curtin 2009:52). The three stories are: Stella's Story, The Responsible Mother, and The Monster and the Granddaughter.

Stella's Story

Stella’s Story is about a girl who lives with her grandmother in a township. She does well at school, but her performance drops after her grandmother falls sick and passes away. She becomes distraught and lonely and a teacher at her school invites Stella to stay with her. The story ends with Stella receiving a degree from university and smiling with the teacher at her side. The story’s message suggests that there is light at the end of the tunnel.

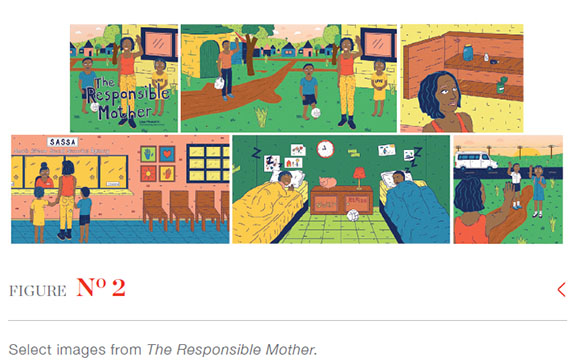

The Responsible Mother

The Responsible Mother tells the story of a mother and her twin children who live in a small village. The mother realises that they do not have food and she hides this from the children, as she does not want them to be unhappy or worried. The mother decides to go to the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA) to ask for help and returns home with groceries and food for the children. She cooks a meal for them, and the children sleep soundly through the night. The story ends with the mother dressing the children for school and waving goodbye to them as a taxi waits. The author explained that the story’s overall message was to depict a responsible mother who asks for help for her family; that there can be a positive outcome in hardship.

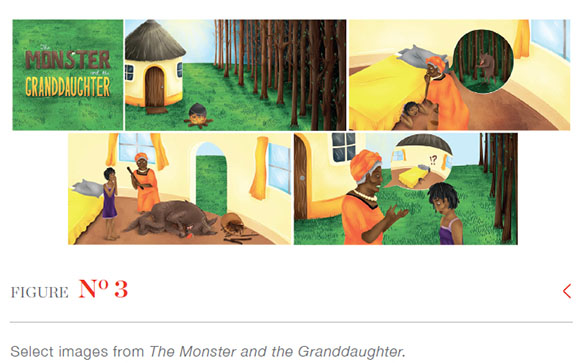

In The Monster and the Granddaughter, a grandmother and her granddaughter, Annabelle, live in a hut by the forest. One day the grandmother goes into the forest to collect sticks and instructs Annabelle to hide under the bed to keep safe from the wolf who lives in the area. Yet, Annabelle disobeys her and gets up to watch her grandmother leave. She stands at the door for too long and the wolf appears. As it is about to hurt her, the grandmother hits the wolf and they tie it up in the forest. Afterwards, the grandmother scolds Annabelle for not listening to her and then comforts the girl after she expresses remorse and promises to always obey her. The message of the story is twofold: first, that it is important to be obedient in order to be safe and second, that the caregiver is there to protect the child.

The Monster and the Granddaughter

Findings and discussion

The three stories contained in the wordless picture books were analysed through the theoretical lenses of social semiotics and narratology and resulted in the discussion of specific cultural signs and symbols. Participants brought their contextual understandings to the stories, which resulted in some stories being relatable and understood and other stories being misunderstood. The participants had positive and negative reactions to certain signs and symbols in the books namely: animals, grandmothers and family, clothing, and symbols of poverty. The following is a presentation of these reactions and a discussion surrounding the necessity of proper context-relative and culturally relevant imagery in wordless picture books.

Presentation of findings

Animals: Cows and owls

The first double-page spread of Stella's Story (SS) features a view of a township with various people, buildings, and a pair of cows. The story's last double-page spread also includes a cow in the left-hand corner. Participant 2 (P2), recognised the cows as a symbol linked to Xhosa culture:

The cows, yes you can do so many things.. .you can use it as a source of meat. .And also use it like when we want to plough in the fields. And then obviously we get milk, because it is really some kind of blessing. If you have too many cows or livestock then you are referred to as someone who is rich.because you can sell the cows. Some of the people don't work, they depend on the cows or sheep or goats...

In P2's response, the cow is identified as a symbol of wealth because of its practical uses. Likewise, P3 commented that the inclusion of the cow in the last double-page spread could mean that the teacher is wealthy. The significance of the cow was also recognised beyond its practical aspects by P2 and P3:

Also, the cows, there are certain cows that you slaughter.for certain things. Like, if maybe you are a person who believes in ancestors, for a man - if the man died you have to make a ritual...to say farewell and then you must look after your family. And if you have...some other problems, female problems, you have your periods, if it's not normal, so there is that certain cow they use for the family. You see they usually use the tail of the cow, they will make something like a thread so that they can put it on...They believe that you will be healed (P2).

...because the cows we use most of the time when we do the cleansing ritual and even if we do the funerals and we don't buy meat, we slaughter the cows and the sheep if your father [has] passed away. We use it as a symbol for our culture. There is something that happens, we connect to the ancestor by slaughtering this cow (P3).

While the respondents were happy with the inclusion of the cow, some felt that other animals could have also been included to enhance the symbolic meaning of the story and make it more context-relevant. For instance, P2 suggested that an owl could have played a foreshadowing role in the narrative: the death of the grandmother. She said:

The owL.people they always cannot see it during the day, you always see it at night, so they relate it with witchcraft, which is like a superstition. Which means it is bad luck. Even if you hear the owl hooting, then it is bad luck. So, it's, for me, it's so obvious.

Additionally, P3 noted that the illustrations in the books could have predicted that something bad was about to happen by the insertion of dark clouds. Similarly, a rainstorm could indicate a new beginning, a positive outcome in the end.

Grandmothers and family

The significant role of the grandmother in Xhosa culture was made evident during participants' reactions to the wordless picture books. Regarding SS, P3 commented on the living arrangement between granddaughter and grandmother:

The grandmother is looking after the girl; it is obvious that the parents aren't looking after the child anymore. As you see that there is a mother and a father in the picture frame on the wall, which means that they passed away.

Even though the portrait of a man and woman on the wall is a very small symbol, P3 interpreted it as a clue as to why the girl was alone and living with her grandmother: her parents had passed away. Further, P3 understood the presence of a grandmother as a blessing: 'Yes, because we can believe what we hear from our grandmother. Yes, even the way [grandmothers] talk to us we get healed'. The inclusion of the grandmother as Stella's guardian emphasises the high regard to which grandmothers are held within the culture. In SS, the grandmother is a sign that signifies that the child is blessed and taken care of; this is a situation that is complicated by the subsequent passing of the grandmother and the lack of a carer in her life. In The Monster and the Granddaughter (TMATG), the grandmother also symbolises a blessing as she rescues her granddaughter from the wolf.

When Stella's grandmother passes away in SS, P3 had difficulty understanding why Stella was alone in the house without anyone there to support her. This is an example of a visual representation that is not context-relative. P3 commented:

Now she is supposed to have neighbours because as soon as they hear that so-and-so has passed away, they come very fast and everyone is in the home so that you don't have time to be alone. There will be people here cleaning, others are making tea and coffee, others are comforting you; you can never be alone like this. So, we need a lot of people [in this picture], a lot of busy people...and she will not sit alone like this, there should be people here who are comforting her, talking to her that everything will be alright.

This scene from SS is, therefore, experienced as incorrect and unlikely. Similarly, the scene where Stella moves in with the teacher is considered unrealistic by P3:

There are no family members again. At least have an aunt or sister with you, but you can't be alone with a teacher. Most of the time even those who don't support you, they sit, and they are there.

The relationship between the teacher and learner is confusing because, according to P3, a family member should be present. The importance of distant relatives and friends of the family has not been portrayed in the illustrations because the illustrator assumed that the grandmother cared for Stella because there was no other family.

Additionally, P4 was concerned with the illustration of the mother in The Responsible Mother {TRM) tying her child's shoes:

I don't understand why the mother is tying his shoes, he is old enough to do it himself, so I am just confused, the mother, I don't like the way that she is doing things now. She is helping the child over and over again. I don't know why.

It appears that this habit is frowned upon within the Xhosa culture, as it does not foster the child's independence. It could be that the illustrator saw this action as a symbol of the mother taking care of the child, but it was not interpreted as such by P4. Clothing

P2 perceived the setting of TRM as similar to a township in the Eastern Cape and read the story in this context. The second double page spread of TRM depicts the mother and her two children on the right-hand page, with the mother waving to a man on the left-hand page. P2 interpreted them as husband and wife and, therefore, concluded that the woman should be wearing a skirt in accordance with clothing customs in the Eastern Cape:

In Eastern Cape when you are married you can't wear pants. Unless she is a single parent, but if we say that the man in the picture is the husband, then that means that she would have to [wear] a skirt.

According to P2, the Xhosa culture is stricter there than in the Western Cape:

Even if you put on pants here or in Cape Town, it's fine. But if you go there [Eastern Cape] you are obliged to wear skirts...it is very strict there. It has something to do with the ancestors. Because now it is your way of showing respect to the older people or the in-laws. And also, it is the way of showing respect to the ancestors because they believe that the ancestors are always watching you.

Additionally, P4 noticed in TRM that the colour of the mother's clothing is inappropriate: 'She has money. Look: red, yellow and white, and she has money for lipstick [laughs]'. The participant continued that the character should have worn a dress with holes in to symbolise that the family is suffering.

Regarding the grandmother's clothes in TMATG, P3 remarked: 'Grandmothers in rural areas don't wear bright colours. You see this is a pearl necklace. You can wear the bead one, then I can understand, but this one must be removed'. The participants also commented on the disconnect between real context and the portrayal of fetching wood in the rural areas. P1 commented, 'No, they don't fetch wood in those baskets. They use their arms or use rope to put them together. The basket is too fancy. She goes to the woods as if she is going to town to buy something'.

According to the participants, the characters in SS wore appropriate attire in terms of colour, fashion, and style. Conversely, in TRM and TMATG they felt that the main characters wore unrealistically colourful attire in regards to the setting and narratives of their respective stories. Additionally, in TMATG, the method of collecting wood was perceived as incorrect. These inaccuracies caused the participants to feel that the stories were somewhat inauthentic.

Symbols of poverty

P3 was unhappy with the sparseness of the interior of the house in SS and felt it was not an accurate representation of what homes in Kayamandi are like. She said: 'Maybe they can have couches, where they can sit. Even though we can see they are happy. We can see the grandmother isn't happy on the chair that she is sitting on'. She argued that if the girl could afford to go to school, they could surely afford to have at least one soft couch.

In TRM, the third double-page spread depicted bare kitchen cupboards as a symbol that the mother is struggling and there is no food in the house. However, according to P3, this should have been symbolised by a cat lying in the fireplace:

We have a hut with a circle at the centre and in the centre there is a cement construction for the fireplace - where we put the pot and the wood when we cook something...If you have nothing to cook, the cat goes and lays (sic) there.

P2 shared the perspective that the proper symbol should have been a cat sleeping in the fireplace:

In Eastern Cape the cupboards can be empty, the fridge can be empty, but we have a fireplace, because mostly we cook in the rondavels6 if it's winter ..so in the middle of the rondavel there is this fireplace where we put a tripod. So, if you cook now and then, the cat can't sleep there because it's hot. But if the cat sleeps there it is cold, which means that you don't have anything to cook; you don't have food.

Both of the above statements also suggest that the illustrator could have designed the house in a more traditional style for a rural village: a rondavel. Even though P2 and P3 had different experiences growing up, their contextual cultural knowledge regarding this matter was the same. P4 added to symbols for 'no food' according to her experience:

If there is no food, what my grandmother used to do (because I grew up also raised by my grandmother) then we will go to so-and-so and ask for [maize], go to so-and-so and ask for cabbage and go to so-and-so and ask for oil. At home we used to have plants like spinach and vegetables and then we just take it up from the garden, but for other things we go and ask. Even if it is sugar, we wake up early in the morning, your grandmother will wake you up and ask you to go ask for sugar.

P4 further commented on the housing situation of TRM:

They have a nice place; you can't say that they are suffering. They have two beds; they have such a big kitchen. You can't say that they are suffering. When you look now at the rooms, because what I know - we share the room with our children...we share the same bed with the daughter and maybe the boy would need to sleep on the floor if you have one room.

At the end of TRM, the children go to school in a taxi. P4 mentioned that this is a symbol of wealth and confuses the story's narrative of poverty:

...it looks like they are taking a taxi to school, which means that the mother has the money to pay for the taxi. When my children were in school there were taxis there to take them, but they used a train because we couldn't afford the taxi, so we took a train.

Also, the portrayal of the SASSA offices in TRM on the fourth double-page spread is especially unrealistic for P4:

No but where are the people? SASSA is never this quiet. Never, never ever... I think this side is closed. There should be people who are sitting and who are in the line. And [the mother] has nothing, you can't go to SASSA if you don't have a birth certificate and a clinic card.

Discussion

The symbols presented above are evidence of the positive and negative reactions respondents had to the symbols included in each of the picture books. They demonstrate the difficulty that is faced when a person outside of the storyteller's culture is tasked with illustrating the story. It underscores the need for deliberate and careful interaction between those involved in each of these processes to create a visual narrative that is culturally and contextually correct and relevant.

Respondents were positive about a number of things in each of these books. They understood the message of each of the stories and, through the use of context clues, could correctly situate them in the locations the storytellers intended. They felt that the animal imagery included in SS - the cow - was correctly utilised and the message that it signified was appropriate. They were also happy with the inclusion of the grandmother in SS and TMATG and shared that grandmothers play a very important role in Xhosa culture - as nurturers, carers, and protectors.

Respondents voiced concerns over a number of issues in each of the books. They reacted negatively to the culturally incorrect depiction of Stella in SS alone after her grandmother died. The lack of family and community support for her seemed especially troubling, as did the role of the teacher. It was emphasised that it should have been family who looked after Stella following this incident and not the teacher

- an outsider. They also found inaccuracies in clothing, as both the style and colour of the clothes for the mother in TRM and the grandmother in TMATG were incorrect. The mother's use of lipstick in TRM was especially laughable to one of the respondents, as she understood it as a luxury item. The depictions of poverty in the stories were also felt to be wrong. In SS the house was not furnished correctly

- it was too sparse - and in TRM it was furnished too nicely for their struggle to be believable. In TRM bare cupboards were deemed to be an incorrect symbol of poverty and the children taking a taxi to school was actually an extravagance that indicated wealth. There was also fault in the depiction of the SASSA offices - it was uncharacteristically quiet. These misrepresentations stemmed from cultural differences but could also have been influenced by class differences between the authors and illustrators (Oittinen, Ketola & Garavini 2018).

Respondents also had ideas for what else should be included such as owls or dark clouds to foreshadow a troubling time ahead and rainclouds to signify the washing away of the old and an ushering in of a new beginning. They also suggested that a cat asleep in the fireplace would be a better depiction of poverty than bare cupboards. While they did not find fault in the architectural depictions of any of the houses, it was also evident that a more traditional style (rondavel) could have been used such as in TMATG.

Participants' readings of these wordless picture books show the importance of using the correct signs - that relate to the correct semiotic resources - for the intended narratological reading of the stories because 'each producer of a message relies on its recipients for it to function as intended' (Hodge & Kress 1988:4). For example, the suggested inclusion of an owl is a symbol that could have a number of different interpretations depending on who is reading the symbol. For the participant and their community, the owl is an omen bringer but in other cultures and contexts the owl has less superstitious connotations (such as wisdom). In every society, there is a unique symbol system that has been formed by and evolved in the society and this allows the same sign to signify something else (Barthes 1999). When examined, individual symbol systems reflect cultural logic, as the symbols' main function is to communicate information between members of a culture (Chandler 2002; Lyle 2000).

The merit of stories produced in the community is evident in the pride the Grade 9 learners displayed in having their stories printed, as well as the enjoyment of Grade R learners to reading stories that they could relate to and understand; they identified with the characters, stories, and contexts. The Grade 9 learners discovered through the writing process that they are narrators with important stories to tell. Natalie Heinsbergen (2013:17) suggests that libraries and classrooms should have picture books available in their facilities that depict signs and signifiers of the learners' own culture to enable them to relate to the stories. If a wordless picture book is created in and for a specific culture group, most people in that culture would be able to understand the book. As Le Roux (2017:82) states, books 'cannot become a cultural good until its contents are relevant and suitable to the culture in which it needs to establish importance'.

However, there are also differences within cultures and culture is not static. It could possibly help if a section in front of the book explains the significance or deeper meaning of the various signs found in the book. This index could help those from different cultures to understand the context of the story. The signs and symbols in the wordless picture books that were received as inauthentic can be used as a catalyst to discussions about culture and difference. A safe space is required, as topics around cultural differences might often be emotionally loaded.

An exploration of the connotations between symbols and the culture depicted was required to determine whether the signs and signifiers were used in a relevant and appropriate way according to the cultural context. There was both positive and negative feedback regarding the contextual portrayal of the signs and signifiers in the wordless picture books. Although the semiotic analysis of these books required the participants to be critical, they still enjoyed the books because authentic stories were used from their own culture and everyday experiences. The reactions of the participants to the signs and the narratives that they signify underscore the importance of the use of context-relative and culturally relevant imagery within wordless picture books. As Daniel Chandler (2002:156) asserts, 'we learn to read the world in terms of the codes and conventions which are dominant within the specific sociocultural contexts and roles within which we are socialized'. Therefore, the correct codes need to be included in imagery of a wordless picture book for the receiver to successfully decode the narrative.

Conclusion

The study demonstrated the necessity of having regular communication between illustrators and authors when creating wordless picture books. This is especially important when the illustrators and authors come from different racial, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds. The illustration process should be led by regular "cultural checks" to ensure that signs and symbols are not confusing or inappropriate. Art students at higher education institutions should be exposed to the importance of context-relative signs and symbols in illustration. Even though the illustration drafts were shown to the authors before the illustrators proceeded to the final drawings, no changes were requested by the authors. This could be due to the power imbalance between Grade 9 authors and researchers (adults), the limitation of their young age (where they are uninformed or unaware of the importance of culturally accurate imagery), or because the authors were simply happy and excited about having their stories illustrated and published. The teachers, however, were quick to point out discrepancies between the illustrated culture and the real culture.

While the authors believe that wordless picture books have the potential to help address the literacy epidemic in South Africa, it is beyond the scope of this article to comment on this specific correlation. This article rather seeks to emphasise the need for careful attention to detail for the production of wordless picture books. This is particularly vital in a cross-cultural collaboration such as this study, where the stories are developed by Xhosa learners, designed by non-Xhosa illustrators, and analysed by Xhosa teachers. Francis Adyanga Akena (2012:606) states that 'when knowledge is produced by an external actor and imposed on an educational system or society, it becomes biased and negatively influences the indigenous knowledge of a people'. This is why it is especially important to create culture and community specific content; to make sure that the right signs are included in wordless picture books to signify the intended, culturally correct narrative. The promotion of this type of knowledge - created by and for the community - could be integral in fostering a love of reading and literacy in these previously marginalised communities (Haese, Costandius & Oostendorp 2018).

Notes

1 . For more on their work refer to Le Roux (2012), Le Roux and Costandius (2013), Le Roux (2017), Haese, Costandius & Oostendorp (2018) and Haese & Costandius (2021).

2 . According to Theo Van Leeuwen (2004:285), 'semiotic resources are the actions, materials and artifacts we use for communicative purposes...[they] have a meaning potential, based on their past uses, and a set of affordances based on their possible uses, and these will be actualized in concrete social contexts where their use is subject to some form of semiotic regime'. They are the multiple codes and modes utilised in the reading of a sign.

3 . An after-school program for high-school learners.

4 . A non-governmental organisation in Kayamandi, Stellenbosch.

5 . The three illustrators from higher educational institutions were selected based on availability. Due to the limited timeframe of the study, illustrators who were able to complete the illustrations within six weeks were selected.

6 . A circular hut with a conical thatched roof found in rural areas in Africa.

REFERENCES

Abdi, AA. 2002. Culture, education and development in South Africa: historical and contemporary perspectives. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey. [ Links ]

Akena, FA. 2012. Critical analysis of the production of western knowledge and its implications for indigenous knowledge and decolonization. Journal of Black Studies 43(6):599-619. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0021934712440448 [ Links ]

Arbuckle K. 2004. The language of pictures: visual literacy and print materials for adult basic education and training (ABET). Language Matters 35(2):445-58. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10228190408566228 [ Links ]

Barthes, R. 1999. Elements of semiology. New York: New York Press. [ Links ]

Chandler, D. 2002. Semiotics: the basics. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Crawford, PA & Hade, DD. 2000. Inside the picture, outside the frame: semiotics and the reading of wordless picture books. Journal of Research in Childhood Education 15(1):66-80. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02568540009594776 [ Links ]

Creswell, JW. 2003. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Lincoln: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Curtin, B. 2009. Semiotics and visual representation. International Program in Design, Architecture and Semiotics:51-62. [ Links ]

Dowhower, S. 1997. Wordless books: promise and possibilities, a genre come of age, in Yearbook of the American Reading Forum XVII, edited by K Camperell, BL Hayes, & R Telfer. Logan, UT: American Reading Forum:57-79. [ Links ]

Denzin, NK & Lincoln, YS. 2000. Handbook of qualitative research. London and New Delhi: Sage Publications Inc. [ Links ]

Eco, U. 1976. A theory of semiotics. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Flatley, JK & Rutland, AD. 1986. Using wordless picture books to teach linguistically/ culturally different students. The Reading Teacher 40:276-281. [ Links ]

Gilbert, KR. 2002. Taking a narrative approach to grief research: finding meaning in stories. Death Studies 26(3):223-239. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180211274 [ Links ]

Haese, A & Costandius, E. 2021. Dithakga Tsa Gobala: a collaborative book creation project. Educational Research for Social Change 10(1):52-69. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2021/v10i1a4 [ Links ]

Haese, A, Costandius, E & Oostendorp, M. 2018. Fostering a culture of reading with wordless picturebooks in a South African context. International Journal of Art and Design Education 37(4):587-598. DOI: https://doi:10.1111/jade.12202 [ Links ]

Halliday, MAK. 1978. Language as social semiotic: the social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold. [ Links ]

Heinsbergen, NA. 2013. The positive effects of picture books providing acceptance of diversity in social studies and increased literacy in early childhood education. MA dissertation, Shahrekord University, Shahr-e Kord. [ Links ]

Herman, L & Vavaeck, B. 2005. Handbook of narrative analysis. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. [ Links ]

Hodge, R & Kress, G. 1988. Social semiotics. Cambridge: Polity. [ Links ]

Insulander, E & Lindstrand, F. 2008. Past and present - multimodal constructions of identity in two exhibitions. Paper presented at the Comparing: National Museums, Territories, Nation-Building and Change conference, 18-20 February, Linköping University. [ Links ]

Klein, KK & Myers, MD. 1999. Evaluating interpretive field studies. MIS Quarterly 23(1):67-94. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/249410 [ Links ]

Kress, G. 2010. Multimodality: a social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Le Roux, A. 2012. The production and use of wordless picturebooks in parent-child reading: An exploratory study within a South African context. MA dissertation, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Le Roux, A. 2017. An exploration of the potential of wordless picturebooks to encourage parent-child reading in the South African context. PhD thesis, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Le Roux, A & Costandius, E. 2013. Wordless picture books in parent-child reading in a South African context. Acta Academia 45(2):27-58. DOI: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC138904 [ Links ]

Lyle, S. 2000. Narrative understanding: developing a theoretical context for understanding how children make meaning in the classroom settings. Journal of Curriculum Studies 32(1):45-63. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/002202700182844 [ Links ]

Nikolajeva, M & Scott, C. 2000. The dynamics of picture book communication. Children's Literature in Education 31(4):225-239. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026426902123 [ Links ]

Oittinen, R, Ketola, A & Garavini, M. 2018. Translating picturebooks: revoicing the verbal, the visual, and the aural for a child audience. New York & London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Rosen, H. 1985. Stories and meanings. Sheffield, UK: National Association of Teachers of English. [ Links ]

Schaffer, A & Watters, K. 2003. Formative evaluation of the first phase of first words in print. Unpublished summary report. [ Links ]

Schurink, W, Fouché, CB & De Vos, AS. 2011. Qualitative data analysis and interpretation, in Research at grass roots, edited by AS De Vos, H Strydom, CB Fouche and CLS Delport. Pretoria: Van Schaik:397-423. [ Links ]

Seale, C. 2012. Researching society and culture. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Sebeok, TA. 2001. Signs: an introduction to semiotics. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

Serafini, F. 2014. Exploring wordless picture books. The Reading Teacher 68(1):24-26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1294 [ Links ]

Spitz, E. 1999. Inside picture books. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa. 2021. Education. [O]. Available: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=737&id=4=4 Accessed 15 July 2021. [ Links ]

Van Leeuwen, T. 2004. Introducing social semiotics: an introductory textbook. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Yin, RK. 2003. Case study research: design in methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [ Links ]