Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a6

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Killmonger: scoring modes and representation in Black Panther

Ntombi Ngubane

University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. ntombingubane@gmail.com (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4872-3473)

ABSTRACT

Anticipated by many, and equally a site of contention or reverence, Black Panther and its accompanying original musical score as composed by Ludwig Gõrranson is rife for analysis and brings to fore the question: in what ways is a Hollywood practice used in a film with seemingly other aesthetic aims? A score which features few disparate and disconnected vague references to an "African sound" for the imagined country of Wakanda is undercut even more so by the insistent use of an otherwise purely western orchestral score. Firstly, through a brief overview of Goransson's production approaches to the score for Black Panther, and his collaboration with local experts, this article argues for a more nuanced understanding of authorship arising from such collaborations between these expert improvising music and film composers who tend to be the sole credited composers. Furthermore, musical representations are complicated by the recurring theme of the "other" according to Classical Hollywood tropes through the integration of occasional African instruments. In section two, brief transcriptions of the music composed for the character Killmonger are provided, in the search for representation devices - how the music works to or fails to establish the character. Also provided are the authors' personal insights as to whether or not Gõransson's intentions with the music are in fact evident in the film.

Keywords: Afrofuturism, music in film, film music, representation, African music in film, film scoring, Black Panther, film scoring practice, orchestration, leitmotif, musical representation.

Introduction

The Marvel science-fiction action film, Black Panther, released in the United States on February 16, 2018, by American writer and director Ryan Coogler, was a box office sensation. Not only was it highly anticipated by Marvel comic book fans, but also by the millions of moviegoers who had been patiently waiting for Hollywood to cast a superhero (protagonist) of colour. Not only did Hollywood not disappoint in this regard, it went above and beyond at bringing us colour and diversity - in the cast, the film's location, the dialogue, and in the music composed for the film. The film's budget was $200 million, and the box office turnover was estimated at $1.347 billion. Even if a person is not a great comic book fan, they too may have gotten caught up in the excitement of Black Panther and what having a superhero of colour means for Hollywood and for future generations. However, some may have been more critical and less celebratory of the film - particularly in the way it represented Africa and Africans.

The widely acknowledged intention of Black Panther was to foreground the idea of Afro-futurism, portraying a future in which Black people use technology to become leaders and forward thinkers of their worlds, outside a world largely controlled by white-dominated superpowers (Robinson & Neumann 2018:3). These themes are explicit in Black Panther. The rest of the world believes Wakanda to be a poor nation of farmers, when in reality it is a highly advanced nation, capable of far surpassing its economic competitors. The aesthetic representation of this idealised futuristic African world is one of the film's major achievements. According to Anthony Michael D'Agostino (2019:2), 'the online understanding of Black Panther implies a rather tightly bound conceptual circuit of inclusive production, representation, and identification'. D'Agostino (2019:2) elaborates, 'black creators create more legitimate representations of blackness (usually because of their own identification with some stable concept of blackness) that are automatically identified with by black viewers who are positively impacted by that identification'.

Since its release, discussion around the film has been generated in academic journals, roundtable discussions and online reviews, confirming the film as not just another Marvel superhero film but a film functioning as a significant cultural moment. The Journal of Pan African Studies dedicated a special issue to the film titled 'On Coogler and Cole's Black Panther Film: Global Perspectives, Reflections and Contexts for Educators', in which the authors Marsha Robinson and Caryn Neumann (2018:4) discuss Black Panther as a 'product of 1960s politics, African imagery and science fiction'. They state that the film is a 'version of Afro-futurism, a genre that draws from social movements, technology, music, religion and literature' (Robinson & Neumann 2018:4). The focus here, within the discussion of Afro-futurism, is how representation can be a hit or miss, specifically through music.

The use of newly composed music to accompany moving images has long been a tradition in classical Hollywood cinema. The earliest uses of synchronised sound in film, beginning in 1926 with the seminal film Don Juan (Crossland), included the synchronisation of recorded orchestral music as well as sound effects that would be used to accompany films. In the 1930s, classical film scoring became standard practice, and has been defined by film music scholars in various ways. Claudia Gorbman (2006:4) suggests film music to be 'scoring that casts music as an inconspicuous part of storytelling'. Ben Winters (2010) offers that we accept music in a film as operating within the fictional state of the world created on screen. Therefore, music not only aids the narrative but belongs in that world as much as any other sound coming from the film (Winters 2010:229). Another tradition, the practice of using 'compilation scores' of pre-existing music, persisted from the 1910s, 'when catalogues of popular music were published to accompany films, through the "library music" of the sound film era of the 1930s and beyond' (Rodman 2006:120). The difference between a film score and a compilation score is that the former refers to music specifically composed for the film, and typically performed by an orchestra, whereas the latter, a compilation score, refers to the use of pre-existing music or a selection of typically popular songs.

Black Panther consists of both a scored soundtrack composed by Ludwig Gõransson, which is made up of orchestral music, as well as traditional African music, and newly written songs produced by Kendrick Lamar. Mark Slobin (2008:3) refers to this use of music in film as being a 'superculture', a term that refers to the 'dominant, mainstream musical content of a society, in effect, everything people take for granted as being "normal"'. Black Panther conforms to some of these dominant practices with the use of orchestral music; while at the same time challenging these practices with the use of traditional African instruments in the composed score. This article pays attention to the original Gõransson score, specifically the music composed for the character Killmonger (comprising elements of the Ancestral theme). Additionally, this paper also interrogates the practice of African representation evident in the different layers that make up Killmonger's music.

Film music composers are aware of which compositional devices to employ to trigger the "right" emotions and reactions required by the listener of the filmic world. Music accompanying a film thus provides important semiotic functions in the narrative, helping filmgoers identify and understand the characters and making sense of their actions. Indeed, as Tom Schneller (2015:49) has argued, film music's 'coordination with images, moods, characters, or actions allows semantic content to be determined with greater precision than is possible with most concert music'. Closely linked to musical semiotics and semantic content is the process of the cultural conditioning of the audio-viewer. Our knowledge of film and music creation is indebted to the Hollywood legacy of cinema due to its global reach. When we watch a film, we are seeing 'similar combinations of visual, verbal, sonic, and musical message, and are being taught to see patterns of musical behaviour through identification and reinforcement' of the Hollywood tradition (Tagg cited by Schneller 2015:50). What this means then is that there are extramusical connotations embedded in the score of a Hollywood film, like Black Panther, which help us identify with characters.

The music composed for the two main characters in Black Panther is made up of several signifying layers, each playing their own significant role. T'Challa's music is made up of four layers: the first layer being the voice of Baaba Maal, singing in the language of the Fulani tribe. The second layer is the talking drum, an instrument native to West Africa that can mimic tones of human speech. The third layer is an 808-drum pattern made on a drum machine called Roland TR-808 that was pioneered during the 1980s and was used predominantly in the hip-hop genre. The fourth layer is the brass instruments, which according to Gõransson, evoke the royal aspect of T'Challa's character. Killmonger's theme is constructed similarly to T'Challa's theme; the first layer is a piano/string melody, inspired by Bach's St Matthew Passion. The second layer is the 808-drum machine pattern. The third layer is the tambin (Fula flute) motif, processed with digital effects and lastly, the fourth layer is the same motif as the tambin, but played by strings.

Throughout the film, there is a use of leitmotifs that are always conveying some aspect of how the story is unfolding. In the case of T'Challa, the music is made to represent his status as a king, while in the case of Killmonger, the music is challenging, yet echoing his own status as a child of Wakanda as much as T'Challa. To take it one step further, musical parameters are not only being used to represent the specifics of each character; one being a king, and the other being a proletariat, but also to represent the difference between Africa and Africans, and the United States and Americans.

In an effort to "authentically" convey the film's African aesthetic in sound, the composer Ludwig Gõransson travelled to Africa to learn more about indigenous musical practices and techniques. This paper uses Göransson's "findings" on African music -instrumentation, performance practices, composition techniques - as translated in his scoring of the music for Killmonger, to explore the intention to construct an African sound world. As such, the intention is to critique the ways in which a Hollywood practice is used in a film with other aesthetic aims. The composed score includes a 92-piece orchestra and a 40-piece choir, recorded over a period of two weeks. Several other thematic devices are used throughout the film to represent the fictional country of Wakanda and its way of life. Such devices are seen and heard through instrumental and timbral choices. In scenes where we are seeing the daily lives of Wakandans, we hear the kora, kalimba, and baliphone, all these instruments are traditional instruments from various parts of the continent, as well as pan-African polyrhythmic percussion.

Musical stereotypes, according to Schneller (2015:49), cause stereotypical physiological reactions and 'composers intuitively employ certain devices which are suited to triggering specific reactions in the listener'. As is typical of Hollywood cinema, representations of socio-cultural groups or characters according to their presented identities on screen rely heavily on filmic and musical tropes that often give rise to stereotyping, essentialising or exoticising - and Black Panther is no exception to this. According to Slobin (2008:20), '"Vernacular" music is that which apparently arises from within a particular group but can be introduced either by the score or as source music'. Slobin continues (2008:20), 'this segment of the soundtrack is a key to the "authenticity" that viewers absorb, the presumed accuracy of the filmworld'. In this way, screen music acts as a tool to represent within and without the film. Social and cultural associations with the music (according to genre, style, instrumentation, and so forth) bleed in from the real world to the imagined film world, and filmic associations can attach themselves to the musical material existing beyond the screen.

This article consists of two sections. The first is an in-depth breakdown of the production process undertaken by Gõransson. Here the discussion is around certain trans-national and cross-cultural ethical issues that arose in the course of producing the film's score, such as those around the representation of place, authorship and the differences between composition and improvisation. Section two is an analysis of the music composed for the film's antagonist, Erik "Killmonger" Stevens. Here is a consideration of instrumentation and melody and their significance in the film. The focus is on only select scenes, rather than undertaking a comprehensive analysis of the score. Transcription and rich description of the music are used to identify what is happening in the music while those characters are present. The transcriptions are partial, piano reductions. Following the music analyses, the musical representations of character and character identities, and how music either helps or undermines their roles, is provided. Also provided is an analysis of how music establishes the statuses of the characters (royalty versus the proletariat).

Scoring Africa: the search for Wakanda

This section unpacks the production process of the music written for the character Killmonger. Ludwig Gõransson details his thought processes, inspiration, and methodology of writing the music for the character in an online podcast called Song Exploder, where musicians take apart their music, and piece by piece, tell the story of how it was made. Below are descriptions of the different musical layers and an explanation, according to Goransson's methods, of how the music tells the story of the character. Intriguingly, an analysis reveals that Goransson's description of the film's music does not always tally with the music in the film itself. Consider how Goransson's approach to creating the music affects the meanings audiences are likely to draw from the music, as well as the significance of the moments when Goransson's description fails to correspond with the music in the film. Consider, as well, the ethical issues involved in the composition of the film's score and critique the representations of an imagined Africa as well as questions around authorship.

Gõransson begins by giving a brief background of how he and the director of the film, Ryan Coogler, first met at the University of Southern California, through a mutual friend, and thereafter, bonded over their shared musical interests. They quickly formed a long-lasting friendship, which then propelled a comfortable working relationship. Gõransson would go on to score all of Coogler's student films as well as all his feature films after university. As soon as Coogler began working on Black Panther, it seemed natural that Gõransson would be his first-choice composer. After learning of this new collaboration, Gõransson purchased as many Black Panther comic books as possible available in stores at the time, which he states 'drew him into that world' - the world of comic books and of Black Panther (Song Exploder 2018). The pair had many conversations concerning the aesthetics of the film's fictional setting. They would ask themselves questions about what Wakanda is, where it is and what other countries it resembled. Gõransson explains that Coogler had travelled to Africa for a research trip and upon his return, gave him a collection of photos, videos, and music that he had heard, which all contributed to Coogler's own inspiration of what Wakanda should look like. In addition to this, Gõransson received an initial draft of the movie script, to which he responded with much admiration and excitement. While sitting with the resources he had been given, however, Gõransson felt a strong need to immerse himself in the environment that Coogler had earlier been in - a non-specific "Africa" - in order to best conceptualise and find inspiration for the music of the film. This is how his journey to the continent began.

Coogler's and Goransson's framing of the continent, as a generalised, homogenous "Africa", requires some consideration, and may be revealing of a broader musical strategy at play in the film. James Michira (2002:2), in his article titled, 'Images of Africa in the Western Media' writes that in the west, especially in America, Africa -with its 54 countries - is often conceptualised as one large country, ignoring the fact that the continent is made up of independent countries, inhabited by peoples of 'diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds'. A consideration of the ways in which the continent is represented musically on screen and the kind of approach detailed by Gõransson in the podcast aligns with one aspect of what Slobin regards as supercultural film music practice. Slobin (2008:20-23) argues the Max Steiner superculture - his term for mainstream film music practice as formulated in the classical Hollywood period - had no particular concern with ethnomusicological accuracy and both the apparently vernacular and the assumed vernacular music in a film with an "exotic" location could bear little or no relation to any actual music in the represented cultures. In grounding the film narrative, avoiding indeterminacy, and making the filmed communities coherent - and instantly communicable - Slobin (2008:60) argues that the superculture 'relies on music to homogenize and often stereotype ethnographically. Soundtracks also replace, displace, erase, reject, and ventriloquize the ethnomusicology of the individuals and groups they depict'.

Goransson's first stop on his research trip was Senegal. He contacted a friend who had worked with Senegalese artist Baaba Maal, whom he quoted as being 'one of Africa's biggest artists' (Song Exploder 2018), whom, after having a brief conversation with Gõransson, was pleased to invite him, not only to discuss the possibility of recording together, but to join him on his tour, scheduled to commence shortly after Goransson's arrival. Baaba Maal, born into a large family of fishermen in the Fouta town of Podor in 1953, after studying music in Dakar, Senegal and Paris, embarked on a two-year musical pilgrimage around West Africa before recording his first album. This explains Maal's musical style - a modern twist on the West African tradition of the griot: 'the storytelling troubadour' (Maal 2017:[Sa]). Maal has also collaborated with many leading musicians and composers from all over the globe, including Hans Zimmer - for the soundtrack of the 2001 action/drama Black Hawk Down - Brian Eno, Peter Gabriel, Tony Allen and U2. Despite his international acclaim, he has always 'acknowledged his roots' by singing in Pulaar, a Fulani dialect of the Senegal river valley (Maal 2017:[Sa]).

One week after his tour, Maal gave Gõransson permission to use his studio where he would begin plotting some musical ideas with the help of various instrumentalists - griots - that he had met during his visit. Gõransson invited these musicians into the studio to record with him. It was not long before Gõransson learned of the Fula flute - a diatonic flute without a bell, made from a conical vine with three finger-holes, native to the West African Fulani tribe. They discovered that there was a Fula player nearby, named Amadou Ba, who they invited to record in Maal's studio. It did not take long after hearing the Fula for Gõransson to know that he had found Killmonger's sound. In the interview, he says that 'having read the script, it just connected with this character' (Song Exploder 2018). Gõransson then pulled Amadou aside and began describing Killmonger to him. First, he gave a background of the film, explaining that Killmonger is the antagonist with good intentions who wants to make the world a better place, but in his own way. He continues, 'he is very smart, but impulsive. He is from Africa, but he grew up in Oakland, in America, and he's coming to Africa to take the throne' (Song Exploder 2018). After the brief synopsis, and after being given a note from which to begin, Amadou began improvising some melodic lines as well as spoken words using the name Killmonger to embody the character musically - to the best of his knowledge.

The scoring practice of recording improvised music performed, in this case, by local Fula flute expert Amadou Ba, which then becomes an integral part of the composed thematic material, is one that is critiqued by Miguel Mera in his analysis of Mychael Danna's score for the film The Ice Storm (1997). Mera observed Danna's use of a Native American flute in the score, performed by flautist Dan Cecil Hill. Hill improvised the "nature" theme in the film. While Danna came up with the initial idea of using the instrument, arranged and edited Hill's improvisations, the actual melodic content of the music is not physically created by Danna, who is the sole composer credited in the film. While Mera argues Danna's work in conceptualising, selecting, and organising the improvised material justifies the different roles, one could argue for a more nuanced understanding of authorship arising from such collaborations between local experts improvising music and film composers who tend to be the sole credited composers. One should stand by Mera's argument that both Danna and Hill contributed to the final score of The Ice Storm. What is noteworthy in Goransson's case is that nowhere in the credits is Amadou Ba mentioned for the contribution he made to the score for Killmonger, which begs the question of the relevance of the instrument.

Gõransson spent a month in Senegal, immersing himself in traditional instruments and recording in Maal's studio. The next stop on his research trip was South Africa. He spent a week in Grahamstown, at the International Library of African Music (ILAM) - the largest repository of indigenous African music, founded by ethnomusicologist, Hugh Tracy in 1954, and dedicated to the preservation and study of African music. In an interview with the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), Gõransson describes his experience of being at ILAM, stating, 'They have recordings from the 1920s through to the 60s. A British researcher travelled around to different tribes and recorded all their music and bought their instruments, wrote down what their songs meant, and collected all of this music. So I spent a lot of time learning about that music and I had to rethink how I made music, and rethink the way that I used the orchestra' (Steenberg 2018).

He spent that week studying the vast archive of African music and instruments. It is uncertain how Gõransson might have taken what he learned at ILAM and translated it into the Black Panther score. In the Song Exploder podcast, Gõransson states, 'the only way for me to be able to do this was for me to do the same kind of research', referring to the research undertaken by the film's director, Ryan Coogler, during his trip to Africa (Song Exploder 2018). After completing his research at ILAM, Goransson's final stop was London, where he recorded a 92- piece orchestra and a 40-piece choir singing in isiXhosa (Steenberg 2018). The assumption here is that the members of that choir are unlikely to be native Xhosa speakers and that they were most likely reading lyrics provided to them by Gõransson, which he compiled while in Senegal and South Africa. As isiXhosa was the official language chosen as the language of Wakanda, the lyrics of the music should have a very prominent feature as they appear in the music. Quite the opposite is found to be the case. At 01:42:27 in the film, somewhat buried amidst the strings and sound effects, there is a brief burst of a choir singing a tribute to T'Challa, as he emerges after being defeated by Killmonger. We hear male voices at first followed by sopranos. The male voices do seem to be singing with lyrics, but these are so indistinct in the mix they would not be identifiable as isiXhosa to even the sharpest-eared audience member. The soprano melody is set to an "oo" syllable. Goransson's attempt to get an actual African language into his score for an imaginary setting - an attempt at providing some ethnomusicological authenticity - contrasts with the approach of the Steiner superculture that, as Slobin (2008:20-23) argues, lacks concern for ethnomusicological accuracy. Just as in the case of the choir, the erasure of the "authentic" African sound of the isiXhosa language in the film is also evident in Killmonger's Fula flute theme.

Bruno Nettl (2015:211) addresses the idea of globalising the music that comes from a foreign culture and fusing it with music that comes from the West, when he writes that since around the year 2000, the issue of doing so (using music/s from foreign cultures) is 'less critical'. The reason it is less critical for ethnomusicologists, he states, is 'because the world's musicians have come to take the situation for granted, maybe because everyone seems to be accepting globalisation and fusion' (Nettl 2015:211). While distortions and misinterpretations may exist at the level of harmony, melody, and rhythmic choices in such cross-cultural musical borrowings, they also exist at the level of language. Nevertheless, the question remains, at least to some, of who owns the music and what may someone who does not own it do with it? (Nettl 2015:212). Gõransson using English musicians to perform in isiXhosa ties in with what Slobin (2008:6-7) calls 'assumed' vernacular. He makes a distinction between music that is 'understood to be vernacular, belonging to a group we get to know, and music that represents an assumed vernacular approach' (Slobin 2008:6-7). Assumed, here, meaning music composed in imitation of the music of the represented community: the 'assumed' Slobin (2008:6-7) argues meaning both '"taken for granted" and "pretending to be something", as in "assumed identity"'. This production process is not uncommon for film composers. British composer Rob Lane, when composing the music for the 2004 political drama, Red Dust, set in South Africa, intended on recording a South African choir, going as far as collaborating with a South African expatriate living in London, Julia Mathunjwa, to assist him in writing the lyrics in isiXhosa (Letcher 2017:81). Unfortunately, however, logistical, and other problems in the recording of South African singers, meant Lane, not an isiXhosa speaker himself, had to attempt to teach the lyrics to a British choir and soloist in London, resulting in somewhat garbled pronunciation (Letcher 2017:83). Gõransson, just as Lane did to a certain extent, engaged in a superculture practice by trying to produce an authentic score, but only going so far in achieving this.

The Fula flute melody above first comes in a few notes behind the piano/harp/strings melody. In fact, this appears only in the soundtrack version of the theme, not the film version. A close analysis of the theme in the film indicates that the flute is removed from the scene. The moment the melody begins, it is heard alongside the piano and harp playing in unison, only joined by the strings a few seconds later. Here, as in the first excerpt, the key is D minor. A harmonic analysis informs us that the flute remains in the key of D minor throughout. The flute melody also enters very quietly alongside the other instruments. It does not, at least to a critical listener, stand out as an African instrument or sound particularly African - it could very well be from the Middle East or South America. In fact, the manner in which it blends with the other instruments could so easily let it be mistaken for just another orchestral instrument. This begs the relevance of using it at all. One must stand by Mera's argument that both Mychael Danna and Dan Cecil Hill contributed to the final score of The Ice Storm (2007) because Hill's improvisations are audible and stand out as traditional instruments even after being arranged and edited by Danna. What is different and noteworthy in Goransson's case is that he credits Amadou Ba for the improvised Fula flute melody in The Song Exploder podcast but nowhere in the credits is Amadou Ba mentioned for his contribution to the track, Killmonger, and the sound of the flute is diminished in the film to sound like any other orchestral instrument. It is confusing then, how this layer of Killmonger's theme represents his African heritage. Göransson mentions shifting the pitch of the flute and adding some effects to it, making it blend with the rest of the music. One can only imagine he could have done the same to any other flute.

Changing the aesthetic quality of the flute degrades its value and authenticity - it is no longer the instrument he had heard in Senegal, it is a sort of improvement from the original. Essentially, it is a Fula flute with a western twist. Goransson's attempt is however thwarted in the end product; the score for this particular section sounds generically like a superhero-type film score in the John Williams tradition and does not carry any identifiably "African" traces.

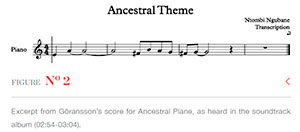

In the film, it is revealed that Killmonger and T'Challa are cousins. Göransson then combines their themes by taking a piece of Killmoger's flute melody and adding it to the brass section of T'Challa's theme (Song Exploder 2018). Figure 2 below is the melody, titled Ancestral Theme, played by sweeping strings. Göransson explains that he used the same motif as part of T'Challa's theme, titled Wakanda as well as for the track titled Ancestral Plane on the soundtrack album. His reason for using the same motif is because of the blood the two characters share as cousins. It is the musical link that bonds the two characters. In Killmonger's theme, the brass plays alongside the same string pattern, seen in Figure 2.

The above excerpt is a slight variation of the Fula flute melody from Figure 1. In the film, it is first heard when T'Challa visits the ancestral plane and sees his late father. The music begins following King T'Chaka's doting words to his son, 'Stand up, you are a king' (01:31:27). As this motif, according to Göransson, was taken from the Fula flute melody of Killmonger's theme, it seems strange that when Killmonger's theme was introduced, it was completely absent from the sequence. A melodic analysis here would indicate the music to be in the key of E minor throughout. The appearance of the F sharp in bars two and three further solidifies the home key. This melodic structure is vastly different to the first time we see this theme in Killmonger's flute. This again would suggest that it bears no link to Killmonger's character; similar to the British museum sequence, the flute is extremely inaudible. It is interesting that what comprises the Ancestral Theme is a piece of improvised music, performed by Amadou Ba in Senegal, taken by Göransson. Whether his actions were intentional or not, he completely Westernised the recording by giving it to a string section to make it feel 'royal and confident' (14:56). In a way, doing so takes away any African-ness from the music and situates it alongside the typical superhero, action style films with big, confident brass sounds, like Superman and Star Wars. Although the emotive quality of the music remains, the African aesthetic is now lost.

The way that music is structured for Killmonger is not so much in layers as it is in motifs. The music, as Göransson describes writing for Killmonger, is never heard in its entirety in the film. What we do hear, however, either while Killmonger is in frame or just before he appears on screen, is one or two of the "layers" that make up his music. It is common to employ musical cues that work as leitmotifs to introduce a character or to let his presence known.

Conclusion

After watching the film, one might find oneself questioning quite a lot about the film, including, but not limited to the music. One must applaud Ludwig Göransson for the beautiful music he composed for the film, he would not have won an Academy Award for his composition if he were not deserving. His intentions were in the right place to travel to Africa and learn about indigenous African musics and instruments. However, his compositions resulted in a sort of carbon copy of blockbuster films depicting Africa, or an imagined Africa, according to western ideologies about the continent. One always needs to move with caution when taking traditional materials and practices and putting them into a new context or media - questions around representation and ethics always follow.

That said, it is very interesting how music carries a myriad of signifiers and whether they are aware of it or not, audience members make associations with characters and situations in a narrative because music has the ability to cue those associations. Furthermore, the emotive quality screen music lends to a filmic world cannot be ignored: if an audience member relates to a character's journey and traumatic experiences, the music lends an air of believability to the narrative experiences portrayed in the film that stitch the evident gap between the audience's reality, and the filmed one. Black Panther in this regard, does well to subdue the audience and bridge the gap between an imagined Wakanda and a real-world cinema. However, the essentialism of this fictional African landscape through an essentialised soundscape is an oversight which cannot be ignored: the use of Baaba Maal as a tool to give a typically "African voice" to an otherwise fictional world; Fula flute or talking drums to aurally signify Africa, somewhat anticlimactically/disjointedly underscored by a western orchestra or choir singing in isiXhosa. Screened media does not exist in a vacuum - it is meant to be consumed, often en-masse. Bearing this in mind, to allow films and film scores to exist unquestioned is negligent of the very idea of consumption culture. The film Black Panther garnered much success and popularity, for reasons that many had personally chosen to engage with the film. However, it is imperative to situate this film in the culture in which it is consumed and according to the culture that it allegedly portrays. Whilst musically adept and through-composed, the score for Black Panther hinges on the very essentialisms of an "African Other" that a film portraying a black African protagonist was intended to disrupt.

References

Baaba Maal. Official Website. "Biography". [O]. Available: http://baabamaal.com/biography/ Accessed 09 November 2019. [ Links ]

Coogler, R. 2018. Black Panther. [Film]. Marvel Studios. [ Links ]

D'Agostino, AM. 2019. "Who are you?": representation, identification, and self-definition in Black Panther. Safundi 20(1):1-4. [ Links ]

Felts, R. 2002. Reharmonization techniques. Boston, MA: Berklee Press. [ Links ]

Genius. 2019. The making of "Wakanda" with Ludwig Göransson. Interview presented by Marvel Studio's Black Panther. [ Links ]

Gorbman, C. 2006. Ears wide open: Kubrick's music, in Changing tunes: the use of pre-existing music in film, edited by P Powie and R Stilwell. Aldershot: Ashgate:1-16. [ Links ]

Letcher, C. 2017. Smooth-throated nation: hearing voices in Red Dust, in African film cultures, edited by W Mano, B Knorpp and A Agina. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Press:74-93. [ Links ]

Michira, J. 2002. Images of Africa in the Western Media. [O]. Available: http://web.mnstate.edu/robertsb/313/images_of_africa_michira.pdf Accessed 9 May 2022. [ Links ]

Nettl, B. 2015. The study of ethnomusicology: thirty-three discussions. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [ Links ]

Neumann, C & Robinson, MR. 2018. On Coogler and Cole's Black Panther film: global perspectives, reflections and contexts for educators. Journal of Pan African Studies 11(9):1-12. [ Links ]

Rodman, R. 2006. The popular song as leitmotif in 1990s film, in Changing tunes: the use of pre-existing music in film, edited by P Powie and R Stilwell. Aldershot: Ashgate:119-136. [ Links ]

Schneller, T. 2015. Modal interchange and semantic resonance in themes by Johan Williams. Ithaca College, NY, USA. [ Links ]

Scott, R. 2001. Black Hawk Down. [Film]. Columbia Pictures. [ Links ]

Slobin, M. 2008. Global soundtracks: worlds of film music. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. [ Links ]

Song Exploder. 2018. Episode 131: Black Panther. Ludwig Göransson - Killmonger. [O]. Available: http://songexploder.net/black-panther Accessed 23 August 2019. [ Links ]

Steenberg, A. 2018. Wakanda (and Sweden) forever: Black Panther's Ludwig Gorasson. [O]. Available: https://www.tiff.net/the-review/wakanda-and-sweden-forever-black-panther-s-ludwig-goeransson/ Accessed March 2018. [ Links ]

Tagg, P. 2012. Music's meanings: a modern musicology for mon-musos. New York & Huddersfield: The Mass Media Music Scholars' Press. [ Links ]

Winters, B. 2010. The non-diegetic fallacy: film, music and narrative space. Music & Letter 91(2):224-24. [ Links ]