Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a5

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Black Panther: a reception analysis

Anusharani Sewchurran

Durban University of Technology, Durban, South Africa. Anusharanis@dut.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8560-2921)

ABSTRACT

Since first screenings, Ryan Coogler's Black Panther (2018) generated a host of celebratory and circumspect literature. The author performed a scoping approach in order to delineate the thematic concentrations (forthcoming). Of significance was the lack of audience reception apart from a Brazilian study (see Burocco 2019) and reflections on watching the film (see Washington 2019). Afrofuturism was deemed a suitable lens through which to view Black Panther as a film contesting political economic bondage of neoliberal globalisation. Avery Rose Everhart (2016) proposes useful categories of displacement, interruption, and disruption as potentially generative for Afrofuturistic thinking. While Black Panther was commemorated, Jalondra Alicia Davis's (2017) caution holds well in terms of scrutinising the structures that inscribe Black success and progress. A reception analysis was therefore conducted to look at how young, Black viewers received the film. The first and third group of respondents consisted of dominantly female university students who live in the suburbs of Ethekwini in South Africa. The second group of respondents were dominantly male youth who live in an informal settlement in the Ethekwini region. The paper chronicles the respondents' reception of the film through an Afrofuturist lens.

Keywords: Black Panther, Afrofuturism, Audience reception, Women and hair, Displacement, Disruption.

Introduction

Texts on Black Panther (Coogler 2018) exploded on the Internet after the release of the film, some of which were interesting and passionate. There were, however, fewer academic interrogations of the film. Using only academic sources as a parameter, a scoping approach was done by the author (forthcoming). Here the scoping approach allowed the author to rapidly map the themes related to Black Panther. The choice of Afrofuturism as a theoretical lens helped to understand some positive narrative potentials. However, exploring the political economy of actors' salaries, grounded the film in Hollywood hegemony. One important finding was that, while themes were varied, there was a distinct lack of audience reception apart from a Brazilian study (Burocco 2019) and an individual reflection on watching the film (Washington 2019). Hence the key research question for this paper attempts to determine how young African students from varied economic levels received the film in terms of its representation of conflict, gender, ancestor worship and technology. This paper attempts to address the gap in the literature by conducting a reception analysis in the Ethekwini (Durban) region of KwaZulu-Natal. Respondents were university students, some living in suburban areas, some from rural areas, and others from an informal settlement on the outskirts of Durban.

Thematic concentrations in the literature spanned debates around decolonisation (Burger & Engels 2019, Flota 2019, Bekale 2018), neoliberalism (Bozarth 2019, Tompkins 2018, Coetzee 2019, Bhayroo 2019), Blaxploitation (Lozenski & Chinang 2019, Burocco 2019, Carrington 2019), Pan-Africanism (Bakari 2018, Nasson 2019, Karam & Kirby-Hirst 2019, Washington 2019), African American identity (Prunotto 2018, González 2019, Bowles 2018), colourism and African female identity (D'Agostino 2019, Gerard & Poepsel 2018, Oboe 2019, Sen 2018, Dralega 2018). Theorists also refer to cosmology and religion (Mosby 2019, Faithful 2018), and aesthetics (Baumann 2018). Generally, the literature follows the format of celebration, reflection and then critique. The entry point to this paper is Stuart Hall's concept of encoding and decoding (1973), after which a snapshot of the respondents is outlined. The thematic focus starts with discussions of political economy related to access, moves to fan labour, representation and hair politics, and concludes with exploring ideas of Afropolitanism.

Precoding, decoding and rearticulating

Stuart Hall's (1973) ideas around culture and the fluidity of meaning remain relevant in this context, as his four stages of communication (production, circulation, communication process and reproduction) invites reflection on wider processes around cinema. Paul Du Gay (1997) later articulated this as the circuit of culture, where a cultural text, in this case Black Panther, may be appropriately understood when one takes into account representation, productivity, consumption and regulation. However the text or sign vehicle is an important starting point, as it carries with it syntagmatic chains of discourse, which upon deeper analysis betrays ruling ideologies:

For Hall, hegemony manipulated beliefs and values to suit the ideas of the ones in power, and language was the place where the dominant ideologies took over. As a result culture was not simply to be appreciated, but it was the place where power relation was established (Gray et al. 2007:156).

In this sense, cultural texts are precoded in production using existing coded signs to activate hegemony, hence 'culture always has both sense making and power bearing functions' (Fiske 1993:13).

Hall (in Gray et al. 2007:156-157) did emphasise that sign vehicles are ideological, but they need to be structured in a relatable way in order to be effective. Industry may precode or encode texts, but this in no way ensures fixed or stable meanings. Hall (1980:130-131) argued that audiences decoded and rearticulated meaning in order for texts to make sense within their own contexts. This remaking of meaning occurs with audiences receiving ideologies as dominant, negotiated or oppositional. Here Edward Schiappa's and Emmanuelle Wessels' (2007:17) notion of polyvalence explains Hall's encoding/decoding model as agency when audiences rearticulate dominant meanings inscribed by productive forces. Hall (1973:2) qualifies these 'relatively autonomous' but 'determinate moments':

We must recognize that the discursive form of the message has a privileged position in the communicative exchange...and that the moments of 'encoding' and 'decoding,' though only 'relatively autonomous' in relation to the communicative process as a whole, are determinate moments.

Afrofuturist scholars, such as Avery Rose Everhart (2016:90-100), suggest that meaning is not fixed, therefore it is important to consider displacement, interruption and disruption as categories of Afrofuturism, as it contests encoded dominant ideologies, even if only 'relatively autonomous[ly]'.

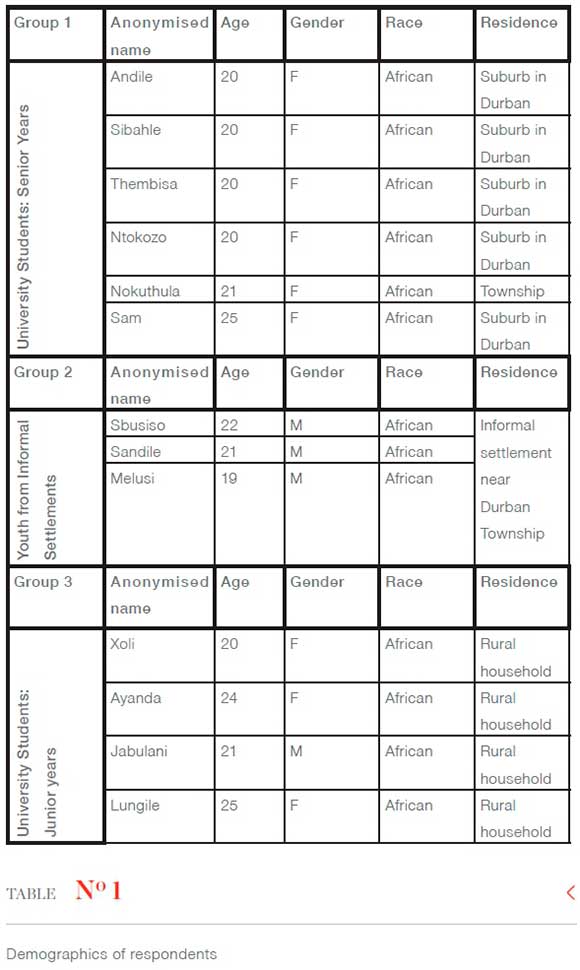

This reception analysis pays close attention to moments of displacement, interruption and disruption as respondents rearticulate Ryan Coogler's Black Panther. This was attempted through a qualitative approach using respondents from Howard College Campus (UKZN) and an informal settlement located in the Ethekwini region. The key aim was to feature how young, African viewers received the film. To this end, three focus groups were conducted of three-to-six respondents in each group. Respondents between the ages of 18 to 25, who watched the film, were invited to participate. The small groupings were deliberate so as to encourage in-depth discussion. While the format was a focus group, semi-structured interview schedules were used in order to stimulate the conversation. The schedule used Tzvetan Todorov (1975) and Vladimir Propp's (1924) narrative structure and universal characters. This was meant to serve merely as a guide to get the discussion flowing. The sessions were transcribed and respondents were anonymised, however, the generic category of gender was retained for analytical purposes. All ethical protocols were observed.

Everhart's (2016:91) categories of analysis in Afrofuturism, 'disruption' and 'interruption', were pursued by juxtaposing respondents. The reception analysis included media students from a university and youth from an informal settlement as a means of interrupting class continuity, possibly disrupting a more staid analysis of Black Panther, as it relates to Afrofuturistic theory.

Breakdown of respondents

The respondent pool consisted of 13 participants and were grouped according to level at university and place of residence. All respondents fell within the 18 to 25 year age range. Nine respondents (70 percent) were female while four (30 percent) were male. Six respondents (46 percent) live in a suburb in the Durban region. Three respondents (23 percent) reside in a rural area, three respondents (23 percent) reside in an informal settlement, and one respondent (eight percent) lives in a Township.

The political economy of access

Black Panther was one of the highest grossing films in South Africa in 2018 (ENCA 2018). The film earned R107 million, proving that so many South Africans watched the film at the cinema. Cinemas in South Africa are generally located in shopping malls and in some city centres, there are small boutique theatres showing art house and fringe genres. In terms of commercial cinema, Ster Kinekor and Nu Metro are the two companies that screen mainstream film in South Africa. Although there are two theatres in the Ethekwini region (in the Musgrave and Pavilion malls), these are still a 25-minute drive away for many of the respondents. The cost of transport often prohibits going to the cinema.

Much of the publicity around the film began in social media spaces. Many of the respondents indicated that this was where their attention was drawn to the film. Interestingly, only two of the 13 respondents viewed the film at a traditional movie theatre, however, they did so only because tickets and transport were provided for them. 11 of the respondents watched it on their computers at home. Thembisa raised the issue of access and prohibitive pricing of films:

Movies are expensive. Black people were not able to watch it. We don't have movies [cinemas] in township areas. If you consider that the tickets are around R80 and you have to commute from the township to the movie theatre and back, it can cost R150 - R200 in total. That's why most of us watched it on our laptops.

Sbusiso and Melusi watched the film at a traditional movie theatre. Sbusiso comments:

I think I heard about the movie before it premiered. It trended on social media. I couldn't watch it the day it premiered. I wanted to but I couldn't go because I could not afford it. I watched it later at the cinema because tickets were sponsored. We had an amazing time.

Sbusiso and Melusi wanted to share their experience with their community.1 Given the popularity of the film with these respondents, a projector was hired for a weekend screening at the informal settlement. The screening of an Afrofuturistic themed film was of some potency in such a space, as it had potentials of unearthing the tensions of futuristic imaginings against a starkly present and troublesome material reality. The film was screened in what is essentially a shipping container which had been rudimentarily converted into a civic space for the youth of this community. Both Sbusiso and Melusi note that this screening was even better than the sponsored cinema viewing because it was experienced communally.

Due diligence and freedom from fan labour

Although Christopher González (2019:14) is critical of the portrayal of the character, Killmonger, he does argue that the film achieves 'due diligence' in terms of Black representation. Andile encapsulates the respondent' uniform reaction to the film:

I thought that people were hyping, you know how people just hype things up, you go in there not expecting as much as...you know you going to tell them you guys are always over reacting and then you are scared to see it but.this was amazing.

In all three focus groups, much time was spent reliving the pleasure of watching a Black film. For non-White audiences, Hollywood forces narrative extraction where one has to search for any points of interpellation which are often negated through marginal roles or invisibility (Merrill 2019:15-16). All respondents spoke about how novel it was to be free from fan labour. Thembisa explains:

It represented...well, Africans and Black people in such a positive light and it made us like Kings and Queens and we weren't seen as, you know, the help or we weren't seen as the friend or the villain. Although the villain was also Black, the hero was also Black and all the supporting characters were Black and positive. We saw our culture represented on the big screen.

The film went further than token presence and structured absence of Black characters. It may be argued that apart from Killmonger, there was no real evidence of caricature of Black characters. Using Todorov (1975) and Propp's (1924) archetypes, Sam articulated the idea of token presence and structured absence, where 'Whiteness is not the centre of non-White people's existence' (Mosby 2019:267):

That's what they always do with Black people. They always make them like the funny guy. The guy that will die first! (Laughter and murmurs of agreement from the group). Like in romantic comedies for example, the Black person is the friend of the hero who is going through the issues with the girl and he gives him tips on how to act. We are never the centre. We are never the educated ones. This was different.

Apart from the "due diligence" in terms of Black representation, one inclusion made the film very relatable. Hall (1980:132-133) indicated that ideological sign vehicles needed to be structured in a relatable way in order to be effective. The inclusion of ancestor worship in the film was raised in each of the three focus groups.

It was interesting to note that youth in all three groups appreciated the inclusion of ancestor worship in the film, although all did not react in the same way. Mbali and Noma appreciated the inclusion of the ritual preceding the spiritual world, while some laughter ensued in Sam's group when she pronounced categorically that the ritual 'does not happen like that'. Ayanda, Sbusiso and Melusi were far more passionate about this aspect. Sbusiso and Melusi indicated that they were really, 'happy they embraced the fact Black people have ancestors who must be acknowledged and praised'. Ayanda gesticulated passionately as she explained:

Movies that involve other worlds, the living and the dead makes more sense than the ones which don't. Because it's culture. When you compare to Captain America.. .is like too western, if you want something to do with machines nje, that's the one. Unlike Black Panther, it reminds us that wherever you go, you just have to know that there is always people older than you and you have your ancestors, you have your roots. You may go to another place but where you come from nje, it will always catch up with you. We need more of African movies that show another side of us, the relationship we have with the ancestors and the power they have upon our lives.

Sbusiso and Melusi however, were critical. Melusi states:

I am unhappy about the language. The King was approaching the ancestors. The King was like throwing words with the ancestors. Because we are Black we are too respectful of our ancestors. The way the King was approaching the ancestors...ey shh...it was very disrespectful. So that I didn't like about the movie.

Sbusiso expands on the problematic use of language:

I hate the fact that they speak in English because you can't speak in English where he [T'Challa] speaks with his father, he speaks with his ancestors in English. No way. When I speak with my father I speak in our home language. If our home language is Xhosa, we speak Xhosa to the elders and at home. I didn't like the fact that the King and the Prince spoke in English in most parts. That was not an appropriate representation of what they were trying to portray yaboh.

It is interesting that the dominant reaction to the ideological interpellations embedded in the 'ancestor scenes', where those who resided in a rural area or the informal settlement. In contrast, students from the suburbs tended show a passing rather than a passionate appreciation of the inclusion. Sbusiso was the most critical:

After we watched that movie, we said that movie reflects Africanity... based on what? It's because of ancestor worship. How do you explain? I think it brings good debate. I'm not against Christianity and any religion but I think it's something we need to discuss because if I am born in a family that is Christian they will shy away from that conversation and I think I am entitled as a child to choose for myself which part I wish to choose. So they need to discuss Christianity, religion, culture and all of that we used to do as Africans, or doing as Africans, rather than disregarding the ancestry.

Representation

Scholars received Ruth E. Carter's costume design in different ways. Karl Baumann (2018:314) saw the costume design as stimulating civic imagination and fan service for Black cosplayers. Bibi Burger and Laura Engels (2019:2) saw the 'references to historical African art and visual culture' as 'Afrofuturist and Decolonial'. Paul Tiyambe Zeleza (cited in Karam & Kirby-Hirst 2019:3) states,

The film, through various portrayals and aesthetics, produces a dangerous homogenisation and a very simplistic view of the African continent; for instance, he observes the 'National Geographic' imagery from tribal markings to 'elongated mouth disk'. In other words, any and all 'tribal' bodily adornments/markings are decontextualised and thrown into the fray, whether they be from Indonesia or Africa, as though anything 'exotic' will do.

Contrastingly, respondents reacted more positively to the costume design, recognising Ndebele neck rings worn by the generals (Thembisa), Basuto blankets (Andile), Istholo (Zulu hat) (Nokuthula), as well as representations of the Maasai (Xoli). With some pride, Thembisa spoke of how she interpreted the use of Gqom music in Shuri's laboratory: 'Gqom started in Durban and represents our rebellious youth culture. Shuri used it in her space to express her refusal to conform'.

Lungile expressed mixed feelings:

I feel like, the day the movie was out when people were going to watch the film, they were wearing African attire. But why don't you just wear it when you feel like it? Why all of a sudden when Americans are representing it then, I don't know, we are more interested in our culture. If it was just another day and someone wore African attire to the movies that would be embracing our culture. But shame the Black Americans tried. They were like so cute. On social media at the movie theatre, different cities and states different people were wearing African attire, I don't know where they got them from.

Audiences found many reasons to celebrate Black Panther, of these the representation of Black woman was paramount. The standard Hollywood tropes around Black women were inverted: 'the mammy' who happily cares for all but herself (Faithful 2018:4); the hyper sexualised 'jezebel', and the tragic mullato and welfare mom (Dralega 2018:464). Carol Azungi Dralega (2018:464) states that:

In Black Panther, the women we encounter have beauty, intellect and strength. Doubling with the Afrocentrism of the movie, authenticity and realism is attained through their attire, language and distinct African hairstyles (the Dora are bald). Because the women 'have it all', we see fewer instances of toxic masculinity and fewer stereotypically masculine traits - even with the King T'Challa, who frequently seeks Nakia's, Shuri's and Okoye's counsel and protection.

Okorafor in her Afrofuturist fiction stressed 'the alienating effects of wigs and weaves, as the painful inscription to colonial norms of beauty' (Marotta cited by Sewchurran (forthcoming)).

Politics of hair

Thembisa was first to comment, saying 'I liked her and the standard of beauty doesn't rely on hair. I really liked that'. Without exception, all the young women in the groups responded to the representation of Black women in the film. Lungile critiqued the Marvel brand:

In Marvel there's always a pretty girl in the movie and she is always a white girl with long hair. And here you have an African with short hair. Even those African Americans, they could pass as Africans. The sister, Shuri, you could see her walking by not looking out of place here.

Thembisa comments on the actress's skin tone and natural hair:

Lupita Nyong'o was amazing. Her acting was on point. She was on point. The representation was on point, she was dark skinned, she had the kinks, the coils in her hair. Her hair was nappy, it wasn't wavy or coloured, it was super tight, you know like a loose curl pattern, it was African, it was natural. And she had Bantu knots as well, it's an African hairstyle where you twist your hair and wrap it around itself.

Andile adds:

I like the fact that they use dark skinned Black people and not light skinned ones with curly and nice hair because we are not all like that. They had curly and dark hair. Like Lupita Nyong'o, she's just dark and she has short hair, she has dark and curly hair. ..it looked gorgeous. Also there's a scene in the movie where there's this woman, I think the general, they were wearing this ama-wigs and at some point she just takes it off and throws it away (laughter from everyone). That was the General Okoye and that was so cool.

Even one of the male respondents commented passionately on the representation of Black women. As Sbusiso expands on Andile's description, one gets a wonderful sense that even young men are aware of the inordinate pressure on Black women when it comes to dominant beauty norms:

Another part, a small scene about her (General Okoye), there's a part where they are in South Korea, she had to wear a wig, (laughter) and she hated every minute of wearing that wig. I don't know, I wish every African woman will actually take note of that and hate wigs like she does. She hates wigs, she hates wigs yaboh. She hated every minute of it thinking, when will I be able to remove this thing? The first moment she got, she removed it. I loved the fact that she loved her bald hair. Even other characters like Lupita, she doesn't have a wig nje. Everyone is using their natural hair. I loved the fact that women are like that but especially that part where she showed that a wig does not have to define a Black woman.

In this sense, the representation of Black women's hair was a celebrated rearticulating of dominant meanings inscribed in the film. The young women's and (young man's) reactions shows the tremendous pressure Black women experience in terms of beauty norms dominant in the media. The conversation around hair led to comments about cultural appropriation and the complexity of representation.

When I am about to sleep I'll make cornrows and I'll never go out with them...ever. Never ever, ever. It was like a bedtime type of hairstyle. And then non-Black celebrities started having cornrows (Andile).

They create the culture and the culture is adopted by other people, and all of a sudden what a Black American is doing is no longer. ...I mean if a Black American is doing a Black American thing, it's ratchet, but if a Latino or White person does it, it's trendy, it's cool (Thembisa).

Cornrows! Kim Kardashian! (Laughter). And now everyone wants cornrows. And the Kardashians changed the name of it. It's because we are so used to seeing this through the media platforms, white models etc. we think we are not good enough (Sam).

Thembisa expands on how stereotypes and particular types of representations endure in the media:

Also how Black and White things are shown, like suicide or depression. When it's a White person, the media will show them to be from a troubled home with no friends. With Whitney Houston it was like she's a crack head. But with Demi Moore, substance abuse is deep depression and mental illness.

Sam then recalled a parallel moment with Black, female athletes:

What about Caster Semenya? I saw this comparison where they put comments about Michael Phelps and Caster Semenya's natural advantages. (Sam pulls up the post from her phone and reads). 'A court just ruled that South African Olympic runner Caster Semenya must take medication to reduce the testosterone that her body naturally produces if she wants to compete. Meanwhile, when medical tests proved that Michael Phelps' body produces less than half the lactic acid that his competitors produce, the Olympic committee praised how lucky he was to have such an insane genetic advantage' (LaRoche [Sa]).

Rearticulating dominant meanings inscribed about women, Kate Erbland (2017) describes the Bechdel Test, which lists three requirements for testing how women are encoded in film. In order to test how active and present women are, the film must include 'at least women in speaking roles, who have names, and who talk to each other about something - anything - other than a man' (Erbland 2017:[Sa]). Lungile inadvertently extended the Bechdel Test to diversity and women as she commented that Black Panther was one of the few films were women occupied non-traditional and powerful roles: 'You know how they always associate Black women with witchcraft, here there is a female leader but no witchcraft'.

This points to a deeper notion of the representation of Black women in film, in other words, that in order to wield power, there must be some devious or unfair means through which the character obtains it, or the powerful female protagonist is trivialised as in some Tyler Perry films. As an important counterpoint, respondents celebrated the representations of women in relation to nature. This is an interesting observation, as often women's knowledge is what results in their persecution. Ramon Grosfoguel (2013:73-74) refers to four 'epistemicides of the 16th century' as 'the extermination of knowledge and ways of knowing', one of which was the killing of women in Europe accused of being witches. Sibahle states: 'The scene when the rhino is charging and General Okoye gets in front of it and it screeches to a halt to express affection. That showed her feminine power over nature and natural things'. Sbusiso was very captivated by General Okoye. He adds:

You know if she was like that in real life I would marry her (laughter by all). I would marry her because I know I would not have to worry about anything because she is super amazing like Melusi is saying, she is brave. But what is more amazing about her is that she is principled.

She knows that she doesn't protect T'Challa or anyone, she protects the throne. So whoever sits in the throne, she is protecting that person. Doesn't matter who the person is, if the person got the seat correctly she will protect you. I loved that character Okoye, I loved that very much. Can I mention what else I liked? I like that the super genius was a young Black woman, Shuri. I think as Africans we need a lot of that from our young women to have people that they look up to, that can give them confidence to do what they want to do. That is what I liked.

The only point of critique was from Thembisa, who said that from a feminist standpoint, 'the general's role was not taken that far, ultimately she was still submissive to the King'.

Afropolitanism

The oppositional reading in the strongest terms emerged interestingly from the young men residing in the informal settlement, and their focus was on the death of Killmonger. Sbusiso comments:

Killmonger, I loved that guy, man! I loved that guy. He was killed by the King at the end of the movie. I understand his anger, man! He was supposed to try and get his revenge. But it was not supposed to.I understand the script writer. I mean the King had to kill him because the script was there. But I think he was not supposed to get killed, because... I would have loved to actually have them together in the same understanding going forward so that they will try to actually share that idea. Because you remember that Killmonger had the idea of liberating every Black person around the world. Yes he was about that even though T'Challa was about making sure that he's protecting Wakanda while Killmonger wanted to liberate every African person that is under oppression around the world. But at the end of the movie we see T'Challa now expanding aid and all of that. Now he is taking the idea that was Killmonger's. So I don't think he will be able to do it the way Killmonger will do it because he understands the entire world much more so if Killmonger didn't die, they were going to be able to actually conquer the world and make the Black nation more powerful because that was the idea of Killmonger. I didn't like the fact that Killmonger died. That is what I'm trying to say, I understand his anger, I understand why he had to fight, because he didn't understand why he was left alone. He didn't have a mum, he didn't have anything there. He was left alone (emphatically stated). And they (emphasised) left him alone. They knew he had a son. It is understandable, all he did. But he didn't have to die man!

The analysis penetrates the simplistic inversion of centre/periphery narratives represented in the film, critiquing in particular the championing of isolationist approaches (Bozarth 2019:21). Sbusiso goes on to interrogate xenophobic tendencies within South Africa, drawing a parallel with the kind of ideological and technological barriers around Wakanda. He states:

You speak of unity, regarding unity they failed very much. The way they've built Wakanda is that it's for Wakandans. It's the idea I hate about South Africans too, they believe South Africa is for South Africans. And other African brothers we need to beat them up and chase them away. I want Africans to be united. Unity first. We see Africa as a continent. I did hear about the movie before it premiered. I expected this technology and saw mountains etc. before the ship went inside. For me they left the surroundings to suffer, to be on their own. Outside the border if you are suffering, you are suffering because there is no unity. That's the issue. South Africa in particular, we have this stigma against African people and I don't know why. And I don't know where it comes from. Whether it's because we are so diverse. I don't get it, why we have been conditioned or socialised to be this way. Honestly, it's a form of apartheid, it works the same way convincing us that we are different to them. And we aren't.

It is interesting to note that while both male and female respondents enjoyed the film, they were able to analyse how power relations were established through the narrative. In this sense, the groups accepted some dominant meanings inscribed in the film. However, there were also significant points of oppositional readings related to particular nodes of oppression. The young women related to the constructions of beauty in the film, however, they remained critical of mainstream and social media's beauty norms. The radical critique on the death of Killmonger significantly emerged from a young man residing in an informal settlement rather than suburbia. This is perhaps as a result of the respondent's tough economic and material circumstances that lends the incisive critique. This contrast with perspectives of respondents emerging from suburban spaces could be as a result of tendency class continuity in higher education (Spivak 2017).

Concluding remarks

Though problematic, Black Panther created a metaphorical space for relatively unfettered imaginings in young Black audiences, the kind of spaces Afrofuturist scholars (like Okorafor) construct through their works of fiction. Xoli states: 'I like it because it promotes possibility. Its fiction is we can reach. We can think of Africa in that sense. We can think of how Africa apart from colonialism could have developed itself'. It was rather significant that a male respondent, Jabulani, saw the possibility of a female Black Panther, hoping for this to be the case for Black Panther II: 'We need to see a female leader. The sister can take the lead, to step up in the waterfall challenge. The next Black Panther can be a women'.

Thembisa highlighted her view of politics:

I like how the Africans were in control of their politics, even if the CIA dude was there, he didn't play such a huge role in being the one to influence or lead the conversation. It was always the African deciding. In the other movies, you always have some sort of foreign intelligence person who is influencing the plot. Here he does not have a controlling role. He just had a helping role.

Finally Sbusiso's perspective is useful as concluding direction:

We excel in sport, we amaze people. But we do need to invest in education and then Africa can amaze the world. I think Africa can develop the world, but it depends on education. Education that we are receiving right now is taking us nowhere. A few individuals are doing amazing things. I am proud but if everyone has some equal opportunities, we can amaze the world.

Notes

1 Sbu and Melusi are part of a youth development group located in the informal settlement in which they live. This group hosts movie days for the youth once a month. They raise money for a projector and screen a morning show for children under 12 and a midday film for teenagers. The films are screened in an old container within the area. This activity has stopped from the start of Covid-19 and the rolling lockdowns.

REFERENCES

Bakari, I. 2018. African film in the 21st century: some notes to a provocation. Communication Cultures 1(1). DOI:10.21039/cca.8 [ Links ]

Baumann, K. 2018. Infrastructures of the imagination: building new worlds in media, art, and design. PhD thesis. University of Southern California, Los Angeles. [ Links ]

Bekale, MM. 2018. Memories and mechanisms of resistance to the Atlantic slave trade: the Ekang Saga in West Central Africa's epic tale. Journal of African Cultural Studies 32(1):99-113. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2018.1532283 [ Links ]

Bhayroo, S. 2019. Wakanda rising: Black Panther and commodity production in the Disney universe. Image and Text 33. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a3 [ Links ]

Bowles, TP. 2018. Diasporadical: in Ryan Coogler's 'Black Panther,' family secrets, cultural alienation and black love. Markets, Globalization & Development Review 3(2):1-9. [ Links ]

Bozarth, H. 2019. Racism and resistance: contextualizing sorry to bother you in the neoliberal moment. PhD thesis. University of Oklahoma, USA. [ Links ]

Burger, B & Engels, L. 2019. A nation under our feet: Black Panther, Afrofuturism and the potential of thinking through political structures. Image & Text 33:1-30. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a2 [ Links ]

Burocco, L. 2019. Do not make Africa an object of exploitation again. Image and Text 33. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a5 [ Links ]

Carrington, A. 2019. From blaxploitation to fan service: watching Wakanda. Safundi 20(1):5-8. [ Links ]

Coetzee, C. 2019. Between the world and Wakanda. Safundi 20(1):22-25. [ Links ]

Coogler, R (dir). 2018. Black Panther. [Film]. Marvel Studios. [ Links ]

D'Agostino, AM. 2019. 'Who are you?': representation, identification, and self-definition in Black Panther. Safundi 20(1):1-4. [ Links ]

Davis, JA. 2017. On queens and monsters: science fiction and the black political imagination. University of California: Riverside. [ Links ]

Dralega, CA. 2018. The symbolic annihilation of hegemonic femininity in Black Panther. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology 10(3):462-465. [ Links ]

Du Gay, P (ed). 1997. Production of culture/cultures of production. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Erbland, K. 2017. Bechdel test 2017 breakdown: which blockbusters passed, failed and what needs to happen next. [O]. Available: https://www.indiewire.com/2017/12/bechdel-test-2017-blockbusters-passed-failed-1201911052/ Accessed 27 May 2020. [ Links ]

Everhart, AR. 2016. Crises of in/humanity: posthumanism, Afrofuturism, and science as/ and fiction. [O]. Available: https://oatd.org/oatd/record?record=handle\:1974\%2F15146 Accessed 27 May 2020. [ Links ]

Faithful, G. 2018. Dark of the world, shine on us: the redemption of blackness in Ryan Coogler's Black Panther. Religions 9(10):304. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100304 [ Links ]

Fiske, J. 1993. Power plays, power works. Verso: New York. [ Links ]

Flota, B. 2019. Challenging 'stereotypes and fixity': African American comic books in the academic archive, in Comics and critical librarianship. Reframing the narrative in academic libraries, edited by O Piepmeier and S Grimm. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press:95-118. [ Links ]

Gerard, M & Poepsel, M. 2018. Female representation in the Marvel cinematic universe. Polymath: An Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Journal 8(2):27-53. [ Links ]

González, C. 2019. A metonym for the marginalized. Safundi 20(1):14-17. [ Links ]

Grosfoguel, R. 2013. The structure of knowledge in westernised universities: Epistemic racism/sexism and the four genocides/epistemicides. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 1(1):73-90. [ Links ]

Gray, SE. 2007. Dean MacCannell and Juliet Flower MacCannelI: the time of the sign: a semiotic interpretation of modern culture. The American Journal of Semiotics 2(3):154-157. [ Links ]

Hall, S. 1973. Encoding and decoding in the television discourse. Discussion Paper. Centre for Cultural Studies, University of Birmingham. [ Links ]

Hall, S. 1980. 'Encoding/decoding', in Culture, media, language, edited by S Hall, D Hobson, A Lowe, and P Willis. London: Hutchinson:128-138. [ Links ]

Haspelmath, M & Sims, AD. 2013. Understanding morphology. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Karam, B & Kirby-Hirst, M. 2019. Guest editor, themed section: Black Panther and Afrofuturism. Image and Text 33. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a1 [ Links ]

LaRoche, L. [Sa]. You cannot take drugs to enhance performance. Why should you have to take drugs to restrict performance? What a contradiction. [O]. Available: https://za.pinterest.com/pin/370069294380592988/ Accessed 12 November 2019. [ Links ]

Lozenski, B & Chinang, G. 2019. Commodifying people, commodifying narratives: toward a critical race media literacy. The International Journal of Critical Media Literacy 1(1):79-92. [ Links ]

Merrill, JP. 2019. The fresh prince of Wakanda - a Zizekian analysis of Black America and identity politics. International Journal of Zizek Studies 13(2):1 -26. [ Links ]

Mosby, KE. 2019. A visit to 'The Clearing' and 'Warrior Falls': in search of brave and beyond spaces for religious education. Religious Education 114(3):262-273. [ Links ]

Nasson, B. 2019. Black Panther on its continent: prowling, pouncing, and parading. Safundi 20(1):26-29. [ Links ]

ENCA. 2018. Black Panther breaks SA box-office records with R100-million gross. [O]. Available: https://www.enca.com/life/black-panther-breaks-sa-box-office-records-with-r100-million-gross Accessed 10 April 2021. [ Links ]

Oboe, A. 2019. Sculptural eyewear and cyberfemmes: Afrofuturist arts. From the European South 4:31-44. [ Links ]

Propp, V. 1924. Morphology of the folk tale. Translated by LScott. Austin: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Prunotto, A. 2018. 'Who are you?': Erik Stevens and the identity question. The anthropology of Black Panther. [O]. Available: https://anthropologyofblackpanther.wordpress.com/2018/06/28/who-are-you-erik-stevens-and-the-solidarity-question/ Accessed 11 April 2020. [ Links ]

Sen, S. 2018. The Black Panther and the monkey chant. African Identities 16(3):231-233. [ Links ]

Schiappa, E & Wessels, E. 2007. Listening to audiences: a brief rationale and history of audience research in popular media studies. The International Journal of Listening 21(1):14-23. [ Links ]

Sewchurran, A. (Forthcoming). A cautious celebration: interrogating Ryan Coogler's Black Panther as a work of Afrofuturism and Capital. Special Edition - Alternations. [ Links ]

Spivak, G. 2017. Book launch: curriculum transformation in Higher Education in Asia and Africa: a reality check. University of KwaZulu-Natal, August 2017. [ Links ]

Todorov, T & Todorov, T. 1975. The fantastic: a structural approach to a literary genre. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Tompkins, J. 2018. Woke Hollywood, all hype the Black Panther. Film Criticism 42(4). [ Links ]

Washington, S. 2019. You act like a th'owed away child: Black Panther, Killmonger, and Pan-Africanist African-American identity. Image and Text 33. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a6 [ Links ]