Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.36 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2022/n36a3

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The Invisibilities of an Afrofuturistic utopia - the erasure of Black queer bodies in Black Panther

Melusi Mntungwa

University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. mntunml@unisa.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7924-1290)

ABSTRACT

Although Black Panther (Coogler 2018) has been revered as a cultural text that presents an Afrofuturistic way Black people could imagine and see themselves, it is not void of societal prejudices. Such prejudices include the treatment of Black queer people in the film's narrative. Much like the society in which Black queer people find themselves, the kingdom of Wakanda in Black Panther fails to acknowledge and depict their humanity and existence. As such, this article interrogates Black Panther's erasure of Black queer individuals from its plot and narrative. It explores the complicated position that Black queer individuals find themselves in, in a society where they are in constant danger of violent erasure from the public discourse. Drawing on a close reading of the Black Panther's narrative, this article argues that, as a cultural text, Black Panther fails to employ ubuntu in its treatment of all identities. At the core of my reading of Black Panther is a critique of how the Afrofuturistic kingdom of Wakanda as a symbol of affirmative Black identity mirrors the same prejudices of present society by not recognising the existence of Black queer identities, erasing them from reality. I ultimately argue that Black Panther's potential to be reflective and inclusive is not optimally reached.

Keywords: Black Panther, Black queer individuals, Ubuntu, Afrofuturism, Erasure, African society.

Introduction

Before Black Panther (Coogler 2018) was released, it was catapulted into public discourse due to inventive and well-resourced marketing machinery and its Afrofuturistic and imaginative appeal. It appeared to be the response to people of African descent around the globe for representation that would best capture their imagination around the Black experience. On the back of years of disillusionment with the positionality of subjugation and helplessness, Black Panther offered a new lens through which Black people in Africa and the diaspora could imagine the possibilities of an Afrodiasporic past and future. Black Panther managed to dismantle stereotypical representations of blackness as a superhero movie by producing a story that exhibits the superheroic capabilities that Black people possess, which allows them to resolve their problems, thus reimagining African histories that are not defined by colonial conquest. It managed to do this by employing an Afrofuturistic mode for presenting prospects for transatlantic imaginations of what it means to be Black in Africa and the diaspora. While dislocating the hegemony of whiteness in film representations by displacing white saviour narratives that are a staple of Hollywood film, the film thus made its creation and release an historic event for Black people of African descent across the globe.

Accordingly, Black Panther had a prominent effect on Black people in different localities. It quenched their desire for affirming representations of blackness and authentic and respectful portrayals of African identities and culture. It also allowed Black audiences the opportunity to be seen as only they could genuinely see each other. This reenvisioning occurred following aeons of dehumanisation and existing in what Frantz Fanon (2008:xii) describes as the 'zone of non-being' - a space in which Black people are not considered human and hence exist on the fringes of the world order while in constant opposition to the structures of that world. Therefore, the response by Black audiences to this film was not only to a visually pleasing cinematic production and enthralling narrative of a Black superhero. The Black Panther viewing experience was instead, as Renée White (2018:426) posits, 'mass psychic relief' for Black audiences. For Black audiences, being able to see and hear themselves and experience African cultures that were treated respectfully was liberatory and relieving. It was liberation from the brutalising representations of blackness that affirmed that Black people of African descent lacked humanness while also countering narratives that define how Black people have been systematically convinced to view themselves. Therefore, Black Panther was affirming dignifying and relieved audiences of the constant anxieties about their blackness and boldly positioned Black people within a position of power and capability.

Although the film was revered as a cultural artefact that presents a progressive aesthetic that invokes pan-African ideals and images of Black power, the film left audiences with many uncomfortable and open-ended questions about the position of continental Africans and Africa in the world. As asserted by Nomusa Makhubu (2019:13), Black Panther is the first of its kind from within Marvel Studios to be 'so transgressive...probing difficult questions about pan-Africanism, Black nationalism, postcolonial neoliberalism, African universalism, and the transatlantic trauma of displacement through slavery and the abiding sense of betrayal'. The Afrofuturistic tools used to remind Black people how to think about and see themselves were not void of pertinent societal prejudices. These prejudices are some of the questions raised by the film, especially concerning African identities and Africanness. Such prejudices that interest arguments in this article include the treatment of Black queer people within African society regarding their positionality, existence, and humanity. Much like the society in which Black queer people find themselves, the imagined kingdom of Wakanda in Black Panther represents a microcosm of society by failing to depict and acknowledge the existence of Black queer individuals, hence presenting questions about its discursive position concerning African sexualities and identities. It is a discourse that Michaela Meyer (2020:237) postulates is fixed within heteronormativity and homophobia, while simultaneously disrupting normative representations of racial and ethnic marginalisation.

As such, in this article, I interrogate Black Panther as a cultural text that is not representative of the multiplicity of African sexualities and identities and lacks inclusivity as it erases Black queer individuals from its plot and narrative. It explores the complicated position that Black queer individuals find themselves in, in a society where they are in constant danger of violent erasure from the public discourse. I heed the appeal of André Carrington (2018:225) that we ought to interrogate continually what textuality and visibility have meant for the way our desires are represented in the popular imagination as we institutionalise the priorities of Black and queer constituencies through academic inquiry. This paper draws from the foundation of African philosophical thought of botho/hunhu/ubuntu, a value system that governs societies across the African continent.

Through this article, I interrogate erasure as an intentional act that is performed against others to reveal how Black Panther, as a cultural artefact that draws on African ethos, presents gaps for developing an inclusive depiction of African sexualities and identities. Aware of the potential pitfalls of whitewashing African philosophical thought in the pursuit of inclusivity as has previously been done relating to the use of ubuntu, I am cautious about imbuing ubuntu with mystical powers that allow it to solve all of Africa's problems or to assume that it was developed with sexual inclusivity in mind. Instead, I draw on its broad definition of 'humanity' and therefore suggest that it would be worth employing to explore and raise questions on what constitutes humanity, inclusivity, and consideration in the representation of African and Afrodiasporic people (Bongmba 2019:26-27). Ubuntu is used in this case to exhibit how the lack of consideration of representations of blackness and African cultures that are not grounded in philosophical thought poses a problem for authentic representations.

In this article I argue contrary to widely held views about the careful, meticulous and thorough approach taken to present inclusive and respectful storytelling that places first the multiplicity of African identities and cultures (Guthrie 2019:21). To assert a position of how more inclusive storytelling could have been achieved, at its core, my reading of Black Panther centers on how the Afrofuturistic kingdom of Wakanda, as a symbol of affirmative Black identity, mirrors the same prejudices of current society by not acknowledging the existence of Black queer identities, effectively erasing them from existence. I put forward that Black Panther's potential to be reflective and inclusive was not optimally reached, while exhibiting how using ubuntu as the guiding ethos would have led to a more representative narrative. At the same time, I advocate for a more nuanced creation of texts that will encourage positive ways of seeing and thinking about the Black experience which will address the spectrum of Black identities more organically and with authenticity.

Situating Black queerness within the Black imaginary - questions on ubuntu

Being Black and queer continues to be a contested site of identity, especially for individuals of African descent, since individuals who identify in this manner are viewed as transgressive and find themselves at the intersection of the two important sites of relegation. I situate its conversation within African discourse and in response to the arguments of scholars of African sexualities, such as Thabo Msibi (2013), Zethu Matebeni and Thabo Msibi (2015), and Ezra Chitando and Pauline Mateveke (2017), around the concern for more vernacular expressions of non-normative sexual and gendered identities. Therefore, the concept of Black queerness is preferred for its fluid expression that considers difference and Black struggles. As Bryant Keith Alexander (2007:1287) asserts,

'Black Queer' captures and, in effect, names the specificity of the historical and cultural differences that shape the experiences and expression of queerness. Moreover, it is in this sense that our intervention, as it were, manifests its radicalism. Further, we believe that there are compelling social and political reasons to make claim to the modifier Black-in Black Queer-both terms, of course, are signifiers or markers of difference; just as queer challenges notions of heteronormativity, heterosexism and homophobia, Black resists notions of assimilation and absorption.

The relegation experienced by Black queer individuals is further compounded when they add African descent or locality to their lexicon of identity, as non-normative identifying individuals are constantly reminded of the proliferated idea that queerness and mainly 'homosexuality is unAfrican' (Dlamini 2006:129). I approach this perception with caution, acknowledging that historically, the idea of Africanness as a singular and monolithic form of expression cannot be divorced from discourses of race-based oppression (Chitando & Mateveke 2017). Africanness draws on the multiplicity of cultures' identities and expressions, which affirm and empower African people and those in the diaspora's experiences, positionality and knowledge.

Several arguments have been presented by politicians, cultural leaders and members of communities to support the idea of homosexuality being unAfrican. These include the most popular, that homosexuality and queer identity are a colonial import imposed on African people. It also includes others, such as the notion that homosexuality is against African tradition and, the most dangerous and prolific, that it is a war against the morality of the Black family. It is a weapon used to disintegrate the Black family and consequently diminishes the Black race altogether (Dlamini 2006; News24 2015; Chitando & Mateveke 2017). Therefore, the amount of marginalisation that Black queer individuals may experience is comprehensible, especially within Black communities. The weaponisation of their sexual identity against these individuals is not exclusive to specific communities, but is instead a struggle experienced across communities.

There are then several questions around the position of Black queerness within blackness struggles which are pertinent to the argument of erasure as evidence in Black Panther. One of the arguments around the positionality of Black queerness in post-1994 South Africa presented by Xavier Livermon (2012) is that, following years of subjugation and dehumanisation due to apartheid, Black queerness does not take a prominent stage in Black struggles. The reality is that in social justice movements within the Black community, the collective struggles of Black people remain innately black, cisgender and heteronormative. These take precedence above the issues of non-normative sexual and gendered individuals. This relegation is especially the case for Black queer individuals who need to fight even harder to have their concerns heard and acknowledged. This struggle is not unique to the South African context, but rather rampant in the rest of Africa and the diaspora. As Nikki Lane (2019) argues in the context of African American studies, heterosexuality largely remains the unquestioned vantage point through which Black gender and sexuality are engaged or scrutinised. They exhibit how the Black community has shown disinterest in issues that are not of a cis-heterosexual orientation.

It is evident from the above that even in times of evolving notions of blackness and community and the use of new tools of affirmation, recognition issues are present. As Black people carve out from their vision of what it means to be Black, this imaginary remains elusive for individuals who do not fit the cis-heterosexual mould. In a space where the humanity of Black people has never been acknowledged, the internal hierarchies of inclusion are perpetuated by failure to use context-specific philosophies and value systems, such as ubuntu, to encourage more inclusive and dignity driven practices. Failure to do so allows for the perpetuation of divisions amongst communities of Black people, who are already relegated by whiteness. This poses concerns regarding the position of Black queerness within the Black imaginary. As is argued by Lethabo Mailula (2018:94), the result of the failure of the collective imaginary to incorporate queer individuals is symbolic violent erasure. Black queer individuals' identity is invalidated because they fail to be imagined as part of the community, hence their erasure.

Using the lens of ubuntu in this context to interrogate the dislocation of Black queerness within Black struggles calls for this article to understand ubuntu as a value system used by communities to measure their 'humanness' (Kamwangamalu 1999:27). Therefore, expressions of an individual's humanness and acknowledgement of the humanity of others is the expression of ubuntu. To illuminate this, Mogobe Ramose (1999:37) emphasises that:

Without the centering the speech of umuntu, ubu is condemned to unbroken silence. Therefore, the speech of umuntu is oriented towards ubu, explicating the essence of the human and their humanness. Not all people are expressed and ascribed to be umuntu. Therefore, humanness is the cornerstone of humanity that qualifies the individual as having ubuntu. Hence, it is the goal to prove oneself to be the embodiment of ubuntu (botho) because the fundamental ethical, social and legal judgement of human worth and human conduct is based on ubu-ntu.

This article attempts to present the notion of humanity as the cornerstone of human activity and how there is a reciprocal relationship between this, and affirming other people's ubuntu. This position is expressed by the isiZulu proverb that also exists in other indigenous languages, 'umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu', which means that to be human is to affirm one's humanity by recognising the humanity of others and, on that basis, establishing human relations with them (Ramose 1999:106).

It is therefore evident that ubuntu represents the core values of African ontologies: respect for any human being, for human dignity and human life, collective sharedness, humility, solidarity, caring, hospitality, interdependence, and communalism (Kamwangamalu 1999:25). This article interrogates how Black queer individuals find themselves on the outlines, even concerning matters of blackness. If the value system of ubuntu is applied, as Bongmba (2016) suggests, to disengage western logic that hyper-visualises difference and uniqueness, it will allow for the acknowledgment of the humanity of others without interrogating their difference and uniqueness, especially concerning their non-normative sexual desire. This article draws on how Black Panther, as a cultural text that reimagines African and transatlantic identities, is unsuccessful in centring African ethos as foregrounding principles. Arguing to recognise Black queer individuals in their multiplicity of difference and uniqueness should not require the employment of cis-heterosexual tropes and tools to appeal to the Black community's sensibilities. Also, one must acknowledge that the preoccupation with cis-heterosexual identity as the singular form of humanity should be expanded to include all individuals who are abantu if the system of ubuntu effectively is applied. The intention is not to desperately plead for Black queer representation, but to acknowledge that non-normativity becomes cumbersome. This is especially true for Black participation and incorporation into capitalism and its normative tenets and formations, such as the nuclear family, domesticity, the nation-state, and patriarchy. Therefore, Black queer erasure becomes essential as Black queers become hindrances to participate in capitalist cis-heteropatriarchy and are thus erased.

In this context, Black Panther, as a cultural artefact that captures the reimagined Black imaginary, presents insights into the imagined ideals of African and diasporic identities relating to the politics of incorporation and erasure in representation. The non-engagement of Black queer representations offers much to ponder regarding the ideal of the Black imaginary and how Black queer identities remain invisible within this invigorated Black imaginary. Suppose cultural texts such as Black Panther are explored using ubuntu (especially within the broad ethics of humanness and difference). Wouldn't these identities be recognised as not deserving of violence, even if there was contention regarding their non-normative sexuality and identity? Would their humanity not be acknowledged, and their existence not erased (Bongmba 2016:31)? Black Panther, as a celebrated text on blackness and the collective Black imaginary, falls short by omitting these intricacies of ubuntu and by failing to employ it as a lens that guides the project. Current imbalances pertaining to Black queerness are

entangled with the internal dynamics of Black cultural politics, leading to the belief that Black queerness should continue to comply in order to be known, but never heard and seen. In this regard, Black queerness should continue to exist in the dark spaces and not threaten cis-heteronormative notions of typical blackness. This kind of non-inclusion closely relates to previously presented arguments, especially in Africa, where there are contentions on the authenticity of Black queerness and its positionality within an African understanding of gender and sexuality. This silencing and eradicating of not only Black but African non-normative identities from existence is perpetuated by Black Panther's peripheralisation of Black queer identities. This idea is further expanded on in later sections of this article, especially when parallels between current African society and the imagined kingdom of Wakanda are explored.

Black Panther and the Afrofuturistic Black imaginary

The recurring foremost positive commentary about Black Panther was how it presented empowering depictions of Black characters while considering and referring to the array of African cultural forms. Black Panther managed to achieve this by pushing the boundaries of the Afrofuturistic aesthetic. The film employs the Afrofuturistic aesthetic, as coined by Mark Dery in 1993, and described by Beschara Karam and Mark Kirby-Hirst (2019:4) as a 'cultural aesthetic that looks at literature, arts, music, music videos, fashion design, films and television programmes through a Black lens. It aesthetically documents Black struggles; Black identity; and Black hopes, as well as acknowledging, or referencing Black historical trauma (collective and individual)'. The creators of Black Panther managed to exhibit the capabilities of Black writers and artists to reform archetypes of blackness that have always been circumscribed by misery and pain attributed only to have existed at the encounter with the colonial powers and slavery. As an emancipatory Afrofuturistic project, Black Panther presents a divergent approach to storytelling that extends beyond the dialect of suffering. Furthermore, it rejects the idea that Black people in the diaspora were without a past or home before colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade (White 2018:424).

Black Panther's employment of Afrofuturism involves rejecting the view that the past is stationary, authentic and could only be understood through a singularity. It conversely opts for a view of the past as a regenerative tool that could be utilised to reframe narratives about being Black within the positionality of dehumanisation. This approach involves using the past: and drawing from it those fragments that allowed for the development of an alternate present and future. Afrofuturism allows for the creation of science fiction that disrupts our understanding of blackness by rethinking the past, present, and futures of the African diaspora; they merge culture, tradition, time, space, and technology to present alternative interpretations of blackness (White 2018:422). The result is a utopic ideal of African and diasporic identity that reimagines Black and African histories across various temporalities and draws on the use of technology to drive this ideal. This approach imagines a fully liberated African nation that is self-reliant, technologically advanced, and is flourishing economically, hence challenging oppressive western stereotypes that portray Africa as backward, underdeveloped, starving and plagued by human rights violations (Elia 2014:85; Karam & Kirby Hirst 2019:5).

Wakanda an Afrofuturistic site for Afrocen-tric-hetero pride and love

Wakanda is presented in Black Panther as the Afrofuturistic imaginative kingdom where African tradition and technological advances intersect to imagine an archetype of African society. In its utopic depictions, Wakanda is presented as a country free from the shackles of western parentialism. As a result, it governs itself, is economically autonomous, and it educates and cares for its people (Robinson & Neumann 2018). Wakanda openly addresses the effects of colonialism by presenting a counternarrative of an Africa never affected by colonialism nor one that exists with the remnants of coloniality (Carrington 2018). In this article, I posit that the Afrofuturistic imaginary of Wakanda, though imagining an Africa not tainted by colonial inheritances, misses the opportunity to engage more deeply in matters of sexual and gendered identities. As such, it effectively removes the multiplicity of African identities and sexualities from its narrative in response to a focus on heterosexuality. Wakanda, as a society, mimics African society even in its imagined state and fails to interrogate, through historicising and futuristic goals, forms of African gendered identities and sexualities. As a result, it misses the opportunity to utilise African value systems to acknowledge this plethora of identities.

In mapping the genealogy of the development of gendered roles in the Igbo and Nobi people, Ifi Amadiume (2015:27-49) draws on mythology to exhibit how African constructions of gender, land and wealth were not developed using the western prism of gender binaries. Women had titles, which could currently be inferred as male titles, including the occupation of "male daughter" roles. This naming and ascribing process exhibits the fluidity of social structures that were not defined by binaries and expectations, particularly in light of gender roles. In their historical works, scholars such as Marc Epprecht (2004) and K'eguro Macharia (2009) exhibit the existence of non-normative sexual desire and activities in Africa since pre-colonial times. Sometimes this kind of sexuality and identity were valued by specific communities across the continent. This highlights a non-western perspective of sexual and gendered identities that counter the narratives of homosexuality being unAfrican. This perspective is of particular interest for Black Panther and Wakanda, which are through their construction a counternarrative to widely held Black representations, yet fail to acknowledge counternarratives about non-normative sexual and gendered identities.

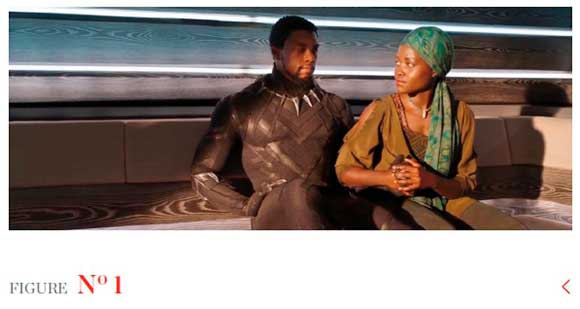

Contrary to the abovementioned possibilities, Black Panther, as a cultural artefact, normalises the relationship between heteronormativity and blackness in African society. It does this by weaponising erasure to altogether remove queer identities so that life in Wakanda affirms heterosexuality and heterosexual identities as the only identities that are believed to be African. Firstly, the covert references to a relationship between Nakia (Lupita Nyong'o) and T'Challa (Chadwick Boseman) form a substantial part of the narrative of Black Panther that is used to reinforce heterosexuality. What results from this is heterosexuality virtually being the only form of sexual identity that exists in Wakanda. This is further embodied in the superhero being the kingdom's monarch which exhibits the popular cinematic convention of overrepresenting heterosexuality as compulsory and the only accepted form of sexual identity. The cis-hetero overarching narrative is supported by a range of sonic and visual cues used in the film to affirm this kind of sexual identity. It is worth noting that there are no explicit depictions of sexuality, but rather the relationship is opaquely referred to through visual references of affection, such as the holding of hands, gazing into each other's eyes and the perceived chemistry between Nakia and T'Challa. The depiction in Figure 1 occurs early in the film after the rescue of Nakia from an undercover mission, therefore, cementing the relationship that T'Challa and Nakia have early in the narrative.

Further references to a relationship and its prospects emerge when T'Challa states, 'If you were not so stubborn you would make a great queen' to which Nakia rebuts, 'I would make a great queen because I am so stubborn...if that is what I wanted'. This love tension between T'Challa and Nakia drives the narrative through the film, while simultaneously affirming this form of identity as what it means to be Wakandan. This employment of visual and verbal cues of heterosexuality gives prominence to heteronormativity as the singular social structure in Wakanda. Conversely, there are no explicit references to non-normative sexual or gendered identities that emerge in the community of Wakanda. The main argument of this article is that failing to use ubuntu as the guiding value system of Wakanda has detrimental effects for the treatment of non-normative sexual identities. The absence of guiding principles relating to the treatment of others ultimately allows for the erasure of queer identities. This enactment is a form of cultural violence that renders Black queer African individuals non-existent.

The choice to not explicitly label queer identities is not unique to Black Panther, but instead forms the utopic lexicon utilised by writers of Afrofuturistic and sci-fi programs in their endeavour to create worlds that do not see or acknowledge sexual identity. Creators attempt to produce according to an egalitarian premise where sexuality is not the defining quality or character. This endeavour leads to the act of not naming the sexual identity of a character, which is perceived to eliminate the risk of marginalisation based on sexuality. A view that is argued against by Mailula (2018:92) who acknowledges that different components intersect to marginalise people and that the utopian ideal of not naming sexuality does not save Black queer African individuals from marginalisation. Utopian Afrofuturistic authors preferring not to name identities is problematic because not naming revisits notions of inhumanness that have been meted against Black people for centuries. The act of not naming and opting for more utopian ideals does not integrate those identities into the greater community. Instead, it merely whitewashes their difference by placating it into the sameness of the dominant, which in Black Panther is heterosexuality. The deed is synonymous with trying to clothe non-normative sexualities, which are viewed as subversive, with dignity.

As a metaphor for an imagined African society, Wakanda raises questions about citizenship for Black queer individuals. When considering the notion of this metaphor, the act of erasing Black queer individuals from Wakanda equates to denying these individuals citizenship. Therefore, if the producers used an ubuntu centred approach, and primarily focused on its core value of communalism, it would have allowed for authentic and respectful inclusion of all forms of identities. Communalism believes that the good of the group determines the good of each individual or, put differently, the welfare of each is dependent on the welfare of all (Kamwangamalu 1999:27-29). So, erasure and the subsequent denial of citizenship posits that some are more valuable than others and that the said society does not believe an individual's success is achieved through the community's success. As a result, sexually and gender-queer citizens of Wakanda and African societies as a result of erasure face what Mailula (2018:94) refers to as 'the violence of non-belonging which nullifies their legitimate existence in society'.

Black Panther as a microcosm of African society - Black queer erasure as weapon

In reflecting the ethos of an Afrofuturistic imaginary, the kingdom of Wakanda in Black Panther draws on several tropes to exhibit a centring of Africa and blackness in its narrative. Wakanda's situation within the African cosmology is introduced when T'Challa has an opportunity to visit the ancestral realm to communicate and receive guidance from his father, T'Chaka (John Kani). This visually represents Black Panther's attention to African cosmology, particularly notions of connectedness with the ancestral realm. African cosmology is the way Africans observe, comprehend and contemplate their universe. It is the lens through which they see reality concerning their systems of values and principles that guide life for African people (Kanu 2013). The reverence of spirituality, particularly the ancestors and divinities, is how Africans maintain harmony in their lived experience. Ritual emerges in Black Panther as essential for harmony to occur and for the connection to the multi force of human existence. The abovementioned scene reveals a healthy relationship between T'Challa as the leader of Wakanda and his forebearers in the spiritual realm.

Communal leadership is another avenue through which Wakanda reflects African principles. T'Challa does not govern Wakanda alone, but his leadership is guided by the decisions of a council comprising the leaders of the different tribes. At crucial points when decisions need to be made, the council needs to communally reach an agreement based on the views of all present. The traditional council meeting portrayed in Black Panther is reflective of the Imbadu/Imbizo/Lekgothla in the South African context. Vuyolwethu Seti (2019:20) describes Imbadu as 'a traditional meeting of amaXhosa where men gather at the family or chief's kraal to raise, discuss and solve issues that affect the village, clan or family'. This is a respectful and reciprocal process involving intense debate/discussion of issues that are crucial to the well-being of the village, clan or family. This kind of communal engagement reflects Afrofuturistic ideas that Wakanda and Black Panther attempt to reignite, primarily when imagined during a time where Africa was not influenced by colonial rule but relied on its ways of governance and peacekeeping (Amadiume 2015). Through communal leadership, Wakanda reflects an African society in its most organic state, not infiltrated by colonialists and their governance practices and principles.

The connection to spirituality and nature is exhibited several times in Black Panther, referencing the connection African people have with nature due to its connections to creation and the divinities. Therefore, the different elements are critical to Black Panther's narrative from new beginnings, enacted on the water, and the connection to the ancestral realm, portrayed by soil and vegetation. As such, the waterfall is where the battle day takes place, and the winner emerges from the water, the new leader of Wakanda. This is associated with the powers of living water that present the opportunity to deal with change (Lawuyi 1998:186). Not only is water crucial to the Wakandans, but so is soil and vegetation and its connection to the land of the ancestors. During the ritual, T'Challa is given amakhambi (herbal medicines) to connect to the ancestral realm and then is covered in the soil to complete the ritual. The herbal medicines refer to the healing capability of vegetation, and the use of soil references to connecting with abadala, an isiZulu expression for (the elders) those who have transitioned from the physical realm and exist now in the spiritual realm. These various references mentioned above draw attention to Wakanda being deeply rooted in the African cosmology and hence is reflective of African society.

From the above sections, it is reasonable to contemplate that Black Panther and Wakanda reflect African society's inclusive nature, that Wakanda is not influenced by coloniality but is rooted within African cosmology and foregrounds African philosophies. Conversely, the erasure of Black queer people offers many questions about the ideal of the imagined authentic African society, which is true to its African heritage while being technologically advanced. The utopian ideal of African society represented by Wakanda in this article contends that the erasure of Black queer identities is paradoxical. Presenting a utopian ideal of the African society before the arrival of colonialism while inaptly excluding queer identities equates to using colonial tropes while affirming to diverge from them, which is effectively paradoxical. The use of heterosexism in Black Panther as the singular form of sexual identity continues to enforce western forms of reasoning, even in the backdrop of a utopian representation of Africa.

The functioning of this erasure works to affirm the fallacy that homosexuality and gender-queer identities are unAfrican. This has been proven by scholars like Busangokwakhe Dlamini (2006:133), who argues that there is historical evidence of African homosexuality that was compatible with African culture cosmology and spirituality. Dlamini's (2006) argument supports the position of earlier scholars such as Stephen Murray and Will Roscoe (1998), who present counter-arguments to the notion of homosexuality being a colonial import and postulate that Europeans did not introduce homosexuality in Africa. Instead, they introduced intolerance of homosexuality and systems of surveillance and regulation for suppressing it. Only when native people began to forget that same-sex patterns were ever a part of their culture, did homosexuality become truly stigmatised (Murray & Roscoe 1998:xvi).

What Murray and Roscoe (1998) indicate is the western and colonial influence on the discourse of homosexuality in Africa and, consequently, dislocate the fallacy that African people are homophobic to protect their cultures and their family moral values. This argument practically exhibits what White (2019:424) argues as the culture being used to offer colonialism rationality, exhibiting how the colonial project intended to eradicate all aspects of the colonised's past that did not fit with the coloniality project. The actual effect that colonialism had on African views through acknowledgement is dislocated to reveal the alternative narrative. Subsequently, it illuminates the paradoxical position that Black Panther occupies through the erasure of Black queer identities from Wakanda and its plot.

The erasure of Black queer individuals from Wakanda and Black Panther is the performance of epistemic, cultural, and psychological violence (Meyer 2020:240). Firstly, it strips Africa of its historical accounts of same-sex desire and non-normative gendered identity through utopian ideals of Africa. This is also an example of the epistemic violence of colonialism, where white hegemonies of knowledge effectively erode all types of local knowledge (Dotson 2011:236). The histories of Black queer individuals are effectively silenced at the expense of presenting an African history from a western perspective. It delegitimises authentic African history and perpetuates western hegemonic control of knowledge. Black Panther, by giving prominence to a western epistemic position, misses the opportunity to glean in more nuanced ways the richness that the knowledge of marginalised groups can offer for better situating them in the world (Carrington 2018:224). In this instance, the value system of ubuntu would have considered the authority of these pieces of knowledge and the erased identities. By employing Afrofuturism's ability to evaporate time to develop a utopian representation of African society, Black Panther effectively opts to yield western views of queerness on African society and, as such, displaces the spectrum of sexual and gendered identities from African history and knowledge.

Secondly, if Wakanda is utopian and presents an Africa never ravaged by colonialism, erasure infiltrates invisibilities that equate to cultural erasure. The producers' efforts to reinforce this ideal through their efforts to affirm African practices and ritual that shows an authentic Africa are disingenuous. It maintains through the removal of a multiplicity of identities and cultures that Africa's history can only be told from a western perspective. It argues that there was no spectrum of sexual identity or gendered identity in Africa that existed outside of heterosexuality and cis-gendered identities. This effectively polices the multiplicity of African identities by forcefully reinforcing the relationship between heterosexuality and African identity to affirm only one type of identity. It fails to simultaneously reclaim Africa in its bold diversities and reinsert queerness in what Stella Nyanzi (2014:65) suggests as the cornerstone of the queering Africa project. Black Panther, as a cultural artefact, is not successful at doing this.

The exclusion is a practical example of how issues relating to non-normativity within social movements and Black issues always get relegated to the periphery. The kingdom of Wakanda as the utopic ideal within the Black imaginary mirrors Black society when it sacrifices issues of Black queer individuals for the greater good of the "Black community". Despite its positive imagining of blackness within an Afrocentric, futuristic vision, it suggests that queerness is not only unwelcome as part of this collective future, but also non-existent. Thus, the film ultimately mimics exclusionary cultural practices that marginalise queer identities, echoing the violation of human rights and lived experiences of Black LGBTQ populations (Meyers 2020:237), revealing how violence sustains itself through cultural practices that erase bodies deemed insignificant (Khunou 2018). The trope of Africa being a hotbed for ignorance, backwardness, and gross human rights violations are opaquely reinforced through the act of erasing Black queer individuals in Black Panther.

Finally, erasure cannot be considered as neutral and harmless; the apparent exclusion of particular identities from the collective history or narrative is an act of violence that has a plethora of psychological ramifications. It is a weapon that inflicts harm on those at the receiving end of that erasure. It is used to silence those subjugated from the film's narrative, but it also functions to diminish their existence in their community. Since belonging is used as a tool to measure inclusion, one cannot reconcile one's identity with a society that does not recognise one's complete identity (Mailula 2018:94). Erasure, therefore, is weaponised to keep Black queer African individuals living in the peripheries of a society that does not accept them. This especially at a time when authentic Black representation is so critical to the Black imaginary, Black queer Africans continue to be considered invisible. The effects of this include Black queer individuals experiencing a perpetual level of Du Boisian double consciousness through cinematic representations and in society at large (Du Bois 1994 [1903]), rendering current Black queer individuals removed from the popular archives at historical moments, such as the release of Black Panther, which was a watershed moment in popular culture and within the Black imaginary. Therefore, this watershed moment is nullified for Black queer individuals, as they cannot identify themselves even in a utopic representation of Africa, but rather see themselves as invisible in the eyes of society. This is an example of how erasure denies the oppressed agency and leaves them in spaces of perpetual relegation.

Conclusion

It is undeniable that Black Panther was a watershed moment for Hollywood film; never has a film been as financially successful and captured the imaginations of audiences across the globe as Black Panther did. From a social perspective, it was the first film to be transgressive in the nature that it changed the superhero film genre by foregrounding blackness and ultimately disrupted white hegemonies of the genre. This was done by eliminating white saviour narratives that are so popular in Hollywood in contrast to revealing the superheroic powers that Black people possess and their agency. Black Panther recognises that representation is paramount, especially concerning blackness, following years of dehumanisation and the perpetuation of skewed and hyperbolic representations affirming racist views about Black people and Africa. Black Panther attempts to address issues of dissatisfaction with Black representations by positioning blackness at the centre of the film's narrative structure, hence doing the liberatory work of breaking stereotypical representations and using Afrofuturism to break the bounds of temporality to imagine an African society and blackness that captured how Black people see themselves and their histories.

As celebrated of a cultural text as Black Panther is, it fails to disassociate itself with certain colonial tropes, especially concerning non-normative sexualities and gendered identities. This results in the erasure of Black queer identities from the narrative structure. The utopia of Wakanda presents several invisibilities, firstly, the invisibility of Black queer individuals in Wakandan society. More epistemically, this is an erasure of African queer histories and identities. Its production reinforces western perspectives on African sexualities and effectively erases African knowledge about the multiplicity of African identities. The development of utopian ideals of not naming identities and sexualities effectively allows for the tools of colonial oppression to erase Black queer identities and African expression of sexuality from African society. Doing this misses an opportunity to use African philosophical foundations and value systems to consult the histories of subversive and subjugated individuals to create more nuanced and authentic representations. As a value system, ubuntu welcomes others and resists violence, making it a practical tool that could be used to engage against violence enacted by erasure.

Therefore, this systemic exclusion and resultant erasure of Black queer identities is weaponised to adhere to singular universals around knowledge of non-normative sexual identities on the African continent. As a result, Black Panther occupies a paradoxical place that perpetuates a myriad of violent acts on African history, and especially Black African queer individuals, while advocating for a pro-Black narrative. This weaponising of erasure in the film results in manifestations of violence, epistemically concerning indigenous knowledge and histories. Cultural violence concerns cultural practices of African localities and, finally, psychological violence, which is perpetrated by the constant disillusionment enacted by non-belonging through representation and in society. This article asserts that though Black Panther changes genres through representative apparatus and narratives of blackness, more could have been done for more inclusive representations. Through this erasure, it paradoxically subdues the masses of Black people by presenting utopic ideals of an African society while missing the mark on using African informed tools that could have allowed it to be more inclusive of the multiplicity of African identities, especially those of Black queer individuals on the African continent and in the diaspora.

REFERENCES

Allen, JS. 2012. Black/queer/diaspora at the current conjuncture. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 18(2-3):211-248. [ Links ]

Alexander, BK. 2000. Reflections, riffs and remembrances: the black queer studies in the millennium conference. Callaloo 23(4):1285-1305. DOI:10.1353/cal.2000.0178 [ Links ]

Amadiume, I. 2015. Male daughters, female husbands: gender and sex in an African society. London: Zed Books Ltd. [ Links ]

Anderson, R. 2016. Afrofuturism 2.0 & the black speculative arts movement: notes on a manifesto. Obsidian 42(1/2):228-236. [ Links ]

Asante, GA & Nziba Pindi, G. 2020. (Re)imaging African futures: Wakanda and the politics of transnational blackness. Review of Communication 20(3):220-228. DOI: 10.1080/15358593.2020.1778072 [ Links ]

Becker, D. 2019. Afrofuturism and decolonisation: using Black Panther as methodology. Image & Text (33):1-21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a7 [ Links ]

Bongmba, EK. 2016. Homosexuality, ubuntu, and otherness in the African church. Journal of Religion and Violence 4(1):15-37. DOI: 10.5840/jrv201642622 [ Links ]

Carrington, A. 2018. Desiring blackness: a queer orientation to Marvel's Black Panther, 1998-2016. American Literature 90(2):221-250. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/00029831-4564286 [ Links ]

Chitando, E & Mateveke, P. 2017. Africanizing the discourse on homosexuality: challenges and prospects. Critical African Studies 9(1):124-140. DOI: 10.1080/21681392.2017.1285243 [ Links ]

Coogler, R (dir). 2018. Black Panther. [Film]. Marvel Studios. [ Links ]

Dery, M. 1994. Black to the future: interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose, in Flame wars: the discourse of cyberculture, edited by M Dery. Durham: Duke University Press:179-222. [ Links ]

Dlamini, B. 2006. Homosexuality in the African context. Agenda 20(67):128-136. DOI: 10.1080/10130950.2006.9674706 [ Links ]

Dotson, K. 2011. Tracking epistemic violence, tracking practices of silencing. Hypatia 26(2):236-257. [ Links ]

Du Bois, WEB. 1994 [1903]. The souls of black folk. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Elia, A. 2014. The languages of Afrofuturism. Lingue e Linguaggi 12:83-96. DOI: 10.1285/i22390359v12p83 [ Links ]

Elia, A. 2016. WEB Du Bois's proto-Afrofuturist short fiction: «The Comet». Il Tolomeo Rivista di studi postcoloniali// A Postcolonial Studies Journal/ Journal d'études postcoloniales 18:173-186. DOI: 10.14277/2499-5975/Tol-18-16-12 [ Links ]

Ekine, S. 2013. Contesting narratives of queer Africa, in Queer African reader, edited by S Ekine and H Abbas. Nairobi: Pambazuka Press:78-91. [ Links ]

Epprecht, M. 2004. Hungochani: the history of a dissident sexuality in Southern Africa. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. [ Links ]

Fanon, F. 2008. Black skin, white masks. New York: Grove Press. [ Links ]

Guthrie, R. 2019. Redefining the colonial: an Afrofuturist analysis of Wakanda and speculative fiction. Journal of Futures Studies 24(2):15-28. DOI: 10.6531/JFS.201912_24(2).0003 [ Links ]

Hoad, N. 2007. African intimacies: race, homosexuality and globalisation. Minneapolis, Minn. University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Johnson, EP & Henderson, MG. 2005. Introduction: queering black studies/"quaring" queer studies, in Black queer studies: a critical anthology, edited by EP Johnson and MG Henderson. Durham, NC. Duke University Press:1-17. [ Links ]

Lane, N. 2019. The black queer work of Ratchet: race, gender, sexuality, and the (anti) politics of respectability. Washington, DC: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Kanu, IA. 2013. The dimensions of African cosmology. Filosofía Theoretica: Journal of African Philosophy, Culture and Religions 2(2):533-555. [ Links ]

Karam, B & Kirby-Hirst, M. 2019. Guest editorial for themed section Black Panther and Afrofuturism: theoretical discourse and review. Image & Text 33:1-15. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a1 [ Links ]

Kamwangamalu, NM. 1999. Ubuntu in South Africa: a sociolinguistic perspective to a pan-African concept. Critical Arts 13(2):24-41. DOI: 10.1080/02560049985310111 [ Links ]

Khuno, G. 2018. The violence of erasure and the significance of excavating the histories of the oppressed. Paper presented at the XIX ISA World Congress of Sociology, 15-21 July 2018, Toronto, Canada. [ Links ]

Khuzwayo, Z & Morison, T. 2017. Resisting erasure: bisexual female identity in South Africa. South African Review of Sociology 48(4):19-37. DOI: 10.1080/21528586.2017.1413997 [ Links ]

Livermon, X. 2012. Queer(y)ing freedom: black queer visibilities in post-apartheid South Africa. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 18(2-3):297-323. [ Links ]

Lawuyi, OB. 1998. Water, healing, gender and space in African cosmology. South African Journal of Ethnology 21(4):185-190. [ Links ]

Macharia, K. 2009. Queering African studies. Criticism 51 (1):157-164. [ Links ]

Makhubu, N. 2019. On the borders of Wakanda. Safundi 20(1):9-13. DOI: 10.1080/17533171.2019.1551737 [ Links ]

Mailula, L. 2018. Violent anxiety: the erasure of queer blackwomxn in post-apartheid South Africa. MA dissertation, University of Pretoria, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Matebeni, Z & Msibi, T. 2015. Vocabularies of the non-normative. Agenda 29(1):3-9. DOI: 10.1080/10130950.2015.1025500 [ Links ]

Meyer, MD. 2020. Black Panther, queer erasure, and intersectional representation in popular culture. Review of Communication 20(3):236-243. [ Links ]

Msibi, T. 2011. The lies we have been told: on (homo)sexuality in Africa. Africa Today 58(1):54-77. [ Links ]

Msibi, T. 2013. Denied love: same-sex desire, agency and social oppression among African men who engage in same-sex relations. Agenda 27(2):105-116. DOI: 10.1080/10130950.2013.811014 [ Links ]

Murray, SO & Roscoe, W (eds). 1998. Boy wives and female husbands: studies in African homosexualities. New York, NY: St Martin's Press. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, SJ. 2015. Decoloniality as the future of Africa. History Compass 13(10):485-496. [ Links ]

News24. 2015. Homosexuality contrary to our values, Mugabe tells U.N. [O]. Available: https://www.news24.com/Africa/Zimbabwe/Horriosexuality-contrary-to-our-values-Mugabe-tells-UN-20150929 Accessed 23 September 2017. [ Links ]

Ngubane, H. 1977. Body and mind in Zulu medicine. An ethnography of health and disease in Nyuswa-Zulu thought and practice. London: Academic Press Inc. [ Links ]

Nyang, S. 1980. Essay reflections on traditional African cosmology. New Directions 8(1):28-32. [ Links ]

Nyanzi, S. 2014. Queering queer Africa, in Reclaiming Afrikan: queer perspectives on sexual and gender identities, curated by Z Matebeni. Athlone: Modjaji Books:65-68. [ Links ]

Ramose, MB. 1999. African philosophy through ubuntu. Harare: Mond Book Publishers. [ Links ]

Ratele, K. 2014. Currents against gender transformation of South African men: relocating marginality to the centre of research and theory of masculinities. NORMA 9(1):30-44. DOI: 10.1080/18902138.2014.892285 [ Links ]

Robinson, MR & Neumann, C. 2018. Introduction: on Coogler and Cole's Black Panther film (2018): global perspectives, reflections and contexts for educators. Journal of Pan African Studies 11(9):1-13. [ Links ]

Serafini, V. 2017. Bisexual erasure in queer sci-fi "utopias". Transformative Works and Cultures 24. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3983/twc.2017.1001. [ Links ]

Seti, V. 2019. On blackness: the role and positionality of black public intellectuals in post-94 South Africa. PhD thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Tamale, S. 2011. Researching and theorising sexualities in Africa, in African sexualities: a reader, edited by S Tamale. Cape Town: Pambazuka Press:11-36. [ Links ]

White, RT. 2018. I dream a world: Black Panther and the re-making of blackness. New Political Science 40(2):421 -427. DOI: 10.1080/07393148.2018.1449286 [ Links ]

Zeleza, PT. 2018. Black Panther and the persistence of the colonial gaze. [O]. Available: https://medium.com/@USIUAfrica/black-panther-and-the-persistence-of-the-colonial-gaze-6c093fa4156d#:~:text=For%20the%20literati%20among%20the,of%20Afrodiasporic%20pasts%20and%20futures. Accessed 5 August 2020. [ Links ]